1. Introduction

Cancer is one of the main causes of mortality worldwide, with millions of cases diagnosed each year and treatments that, although effective in certain contexts, have significant limitations [

1]. Conventional therapies, such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, have been proven to be effective but are often associated with significant adverse effects and high toxicity, which compromises the quality of life of patients and can limit the effectiveness of long-term treatment [

2]. This situation has encouraged the search for new therapeutic alternatives, among which immunotherapy has gained relevance due to its ability to activate the patient’s own immune system and attack malignant cells more precisely.

Among the different immunotherapy modalities, the one based on dendritic cells (DCs) has proven to be one of the most advanced and promising in the treatment of cancer [

3,

4]. DCs play a key role in the activation of the immune system because they are responsible for processing and presenting tumor antigens to T lymphocytes, generating a specific response against malignant cells. The ability to “pulse” DCs with specific antigens allows treatment to be personalized according to the unique molecular characteristics of each tumor and patient [

5,

6]. This not only improves the specificity of the immune response, but also reduces the risk of damage to healthy tissues.

Recently, attention has turned towards the use of dendritic cell-derived exosomes (DEXs) as a therapeutic adjunct [

7]. Exosomes are extracellular vesicles containing proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, which amplify immunological signals by effectively delivering them throughout the body. Furthermore, exosomes possess structural stability that allows them to penetrate difficult-to-access tumor tissues, increasing their therapeutic potential [

8]. This duality between treatment personalization through pulsed DCs and the use of exosomes as therapeutic vehicles has opened up new opportunities to optimize immunological therapies in oncology.

Despite these advances, maximizing the effectiveness of immunotherapy with DCs and exosomes requires the development of comprehensive monitoring protocols that combine clinical assessment with detailed molecular analysis. Traditional clinical scales, such as RECIST and iRECIST, are useful for assessing tumor response but lack the ability to accurately measure immune activity or apoptosis induction in cancer cells [

9,

10]. For this reason, this study proposes a comprehensive protocol starting from progenitor cell isolation and moving to the laboratory-based assessment of the immune response, using advanced techniques such as flow cytometry, ELISA, and Western blotting, to ensure the continuous and effective personalization of treatment.

In this context, the main objective of this study was to develop a monitoring protocol that integrates clinical and molecular information to maximize accuracy in the evaluation of the efficacy of immunotherapy, allowing real-time adjustments based on the patient’s response.

2. Bases of Monitoring in DC Immunotherapy

Monitoring in DC immunotherapy is crucial to ensure the efficacy of treatment in cancer patients. The first key step in this type of DC immunotherapy is the isolation of progenitor cells, specifically peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Separation is carried out using density gradients, which allows an enriched fraction of monocytes, lymphocytes, and other hematopoietic cells to be obtained, which are essential for subsequent differentiation into DCs [

11] (

Figure 1). The viability of the progenitor cells is crucial because any contamination would compromise the quality of the resulting DCs.

Following the isolation of PBMCs, they are differentiated and matured. The differentiation of monocytes into DCs is induced using specific cytokines such as GM-CSF and IL-4, and this process is continuously monitored to ensure that the cells reach the appropriate immature state. Maturation is achieved by the addition of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β, allowing DCs to efficiently present tumor antigens [

6,

12] (Figure 2). Monitoring is essential to ensure that the DCs can fulfill their key immunological function and trigger a specific antitumor response.

One of the most critical parameters to control in this process is cell viability. Viability must be maintained above 90% to ensure that the DCs can fulfill their function of activating T lymphocytes and orchestrating a specific immune response against cancer. For this purpose, techniques such as flow cytometry and cell exclusion assays, such as the Trypan blue exclusion test, are used, which allow the proportion of viable cells to be measured to ensure that the culture maintains its integrity throughout the process [

13,

14]. The parameters that are evaluated and their expected values are presented in

Table 1.

Furthermore, at this initial stage, the quality control of the exosomes is essential because these extracellular vesicles play a crucial role in the amplification of the immune response. The exosomes’ size and concentration are measured to ensure that they meet the parameters required to function as carriers of tumor antigens. Analytical techniques such as Nanosight have proven effective for this evaluation [

15].

3. Optimization and Characterization in the Molecular Laboratory

The monitoring and optimization of DC immunotherapy require a combination of clinical and molecular assessment. While basic monitoring focuses on the biological quality of the DCs and exosomes, optimization in the molecular laboratory focuses on perfecting the technical aspects to ensure the consistency and effectiveness of the treatment in cancer patients.

3.1. Optimizing Progenitor Cell Isolation and DC Differentiation

Progenitor cell isolation is a critical phase that directly influences the differentiation and maturation capacity of the DCs. To obtain highly viable progenitor cells, advanced cell separation methods and specific centrifugation conditions have been developed. These refinements increase the viability and yield of PBMCs, thus improving the efficiency of the subsequent differentiation [

16,

17].

During the DC differentiation and maturation process, specific markers such as CD80, CD83, and HLA-DR are evaluated using flow cytometry, because their correct expression indicates that the DCs have reached an optimal state of maturation. The identification and constant monitoring of these markers allows early adjustments to be made to the culture conditions and ensures the functionality of the mature DCs [

18].

3.2. Structural and Functional Characterization of Exosomes

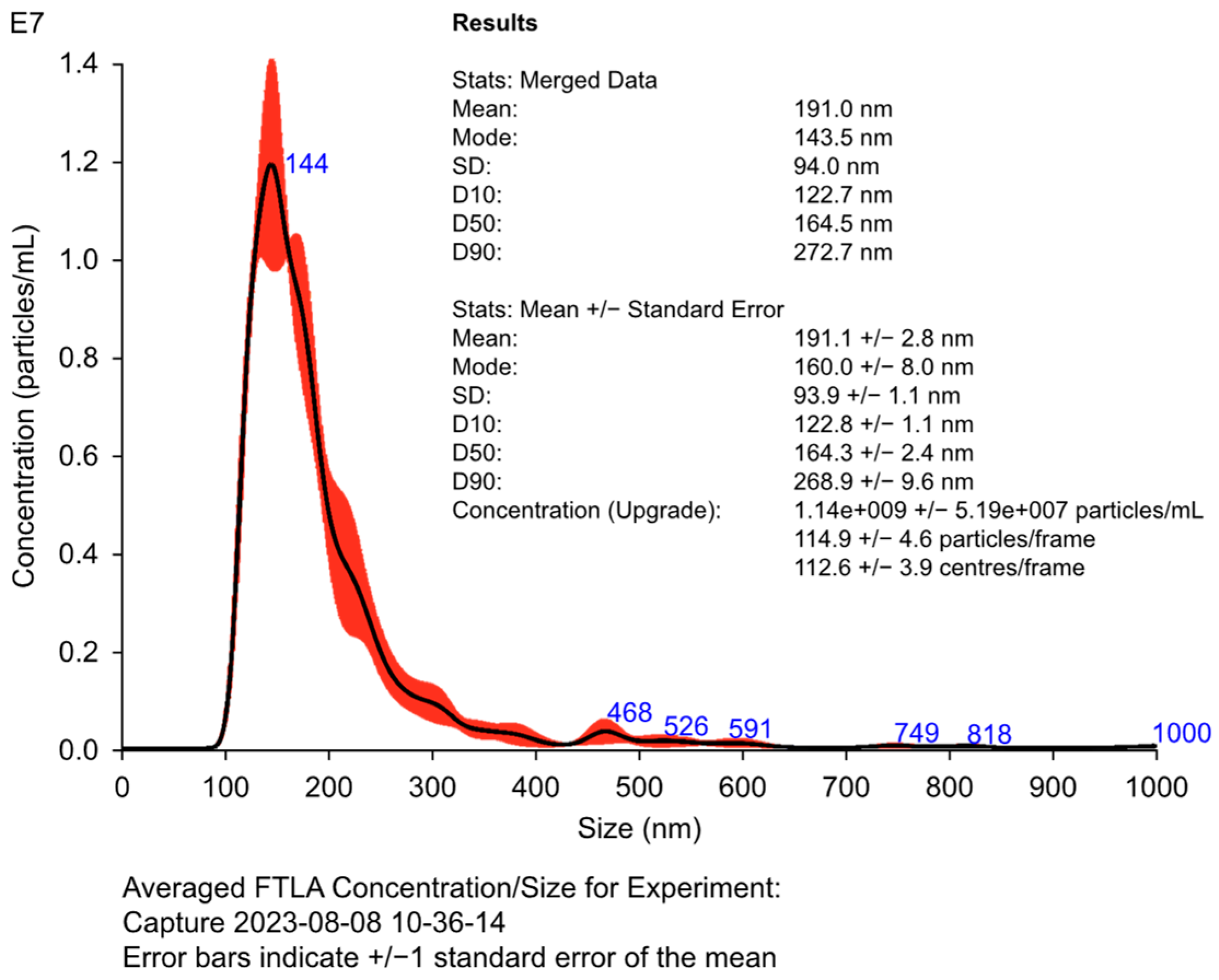

The characterization of DEXs is a fundamental step in evaluating their quality and functionality. Techniques such as Nanosight and Western blotting are used to measure the size, concentration, and presence of specific exosomal markers such as CD63, CD81, and Alix (Figure 3), which are essential to confirm the ability of the exosomes to effectively transport tumor antigens [

19,

20]. The correct concentration and size ensure that the exosomes operate effectively as immunological vehicles. The size, concentration, and specific exosomal markers are evaluated to ensure the stability and functionality of DEXs (see

Table 2).

Figure 3.

An analysis of the secretome of mature DCs, assessed using Nanosight, is presented. The histogram shows the size and concentration of the different microvesicles present in the secretomes of DCs. The internal table demonstrates the main parameters in a sample containing microvesicles and exosomes obtained through analysis using the Nanosight technique, including the mean, mode, and concentration values, indicating the effectiveness of the purification process.

Figure 3.

An analysis of the secretome of mature DCs, assessed using Nanosight, is presented. The histogram shows the size and concentration of the different microvesicles present in the secretomes of DCs. The internal table demonstrates the main parameters in a sample containing microvesicles and exosomes obtained through analysis using the Nanosight technique, including the mean, mode, and concentration values, indicating the effectiveness of the purification process.

3.3. Advanced Quality and Functionality Assessment

In addition to structural properties, it is crucial to assess the functional capacity of exosomes. This includes the induction of T-cell activation and the production of key cytokines such as IFN-γ, which is measured using ELISA [

21]. This functional assessment ensures that exosomes fulfill their role as amplifiers of the antitumor immune response.

To obtain high-purity progenitor cells, we specifically adjusted the cell separation protocol by fine-tuning parameters such as centrifugation speed, separation medium density, and incubation temperature. These adjustments were tailored and validated during the course of our study to address specific challenges observed in our experimental setup, significantly increasing the viability of the isolated PBMCs and enhancing the efficiency of subsequent differentiation. While these modifications build upon established protocols, their integration into a cohesive workflow is a contribution unique to this work, ensuring reproducibility and adaptability for similar laboratory applications.

4. Immune Monitoring Protocol

Immune monitoring in pulsed DC and exosome immunotherapy is crucial to fine-tune and optimize the immune system’s response to treatment. This approach focuses on accurately measuring T-cell activation; characterizing the Th1, Th2, and Th17 immune profiles; and assessing apoptosis in tumor cells [

22]. T-cell activation, specifically of the CD4+ and CD8+ subtypes, is considered a critical indicator, as these cells are responsible for orchestrating the antitumor response by destroying malignant cells.

Flow cytometry is a key tool used to assess the expression of activation markers such as CD69 and CD25. These markers provide a direct measure of the level of cellular activation among T cells [

23]. ELISA enables the analysis of the production of key cytokines, such as IFN-γ and IL-12, which are essential for an effective immune response. The robustness of T-cell activation is measured by the proportion of activated CD4+ and CD8+ cells, which is expected to be higher than 70% after co-culture with pulsed DCs [

24].

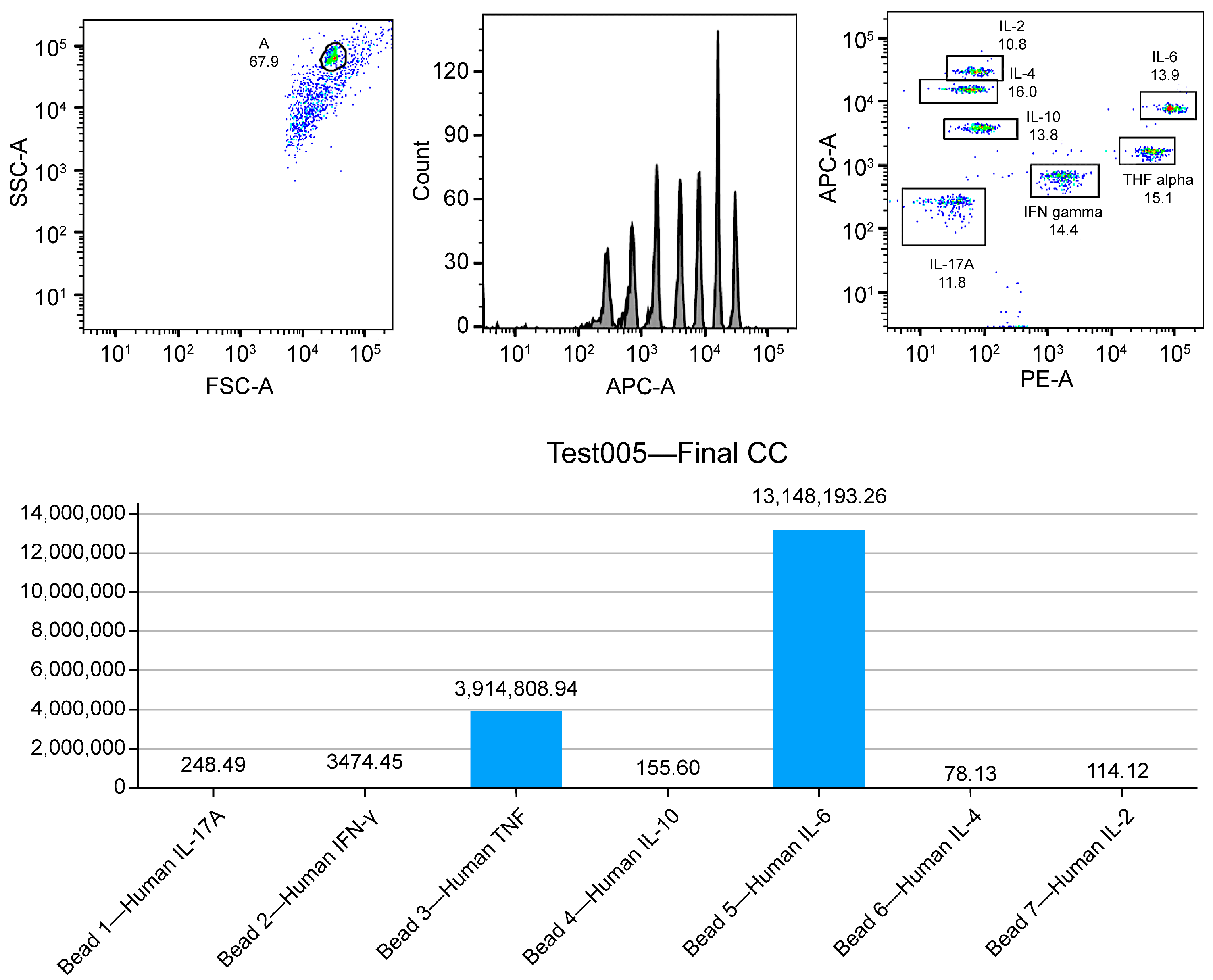

Furthermore, the analysis of Th1, Th2, and Th17 immune profiles is crucial to characterize the polarization of the immune response. A Th1 profile is ideal for a cytotoxic response against tumor cells, mediated by cytokines such as IFN-γ and IL-12. In contrast, an elevated Th2 profile, associated with cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10, may have an immunosuppressive effect, which would compromise the effectiveness of the treatment [

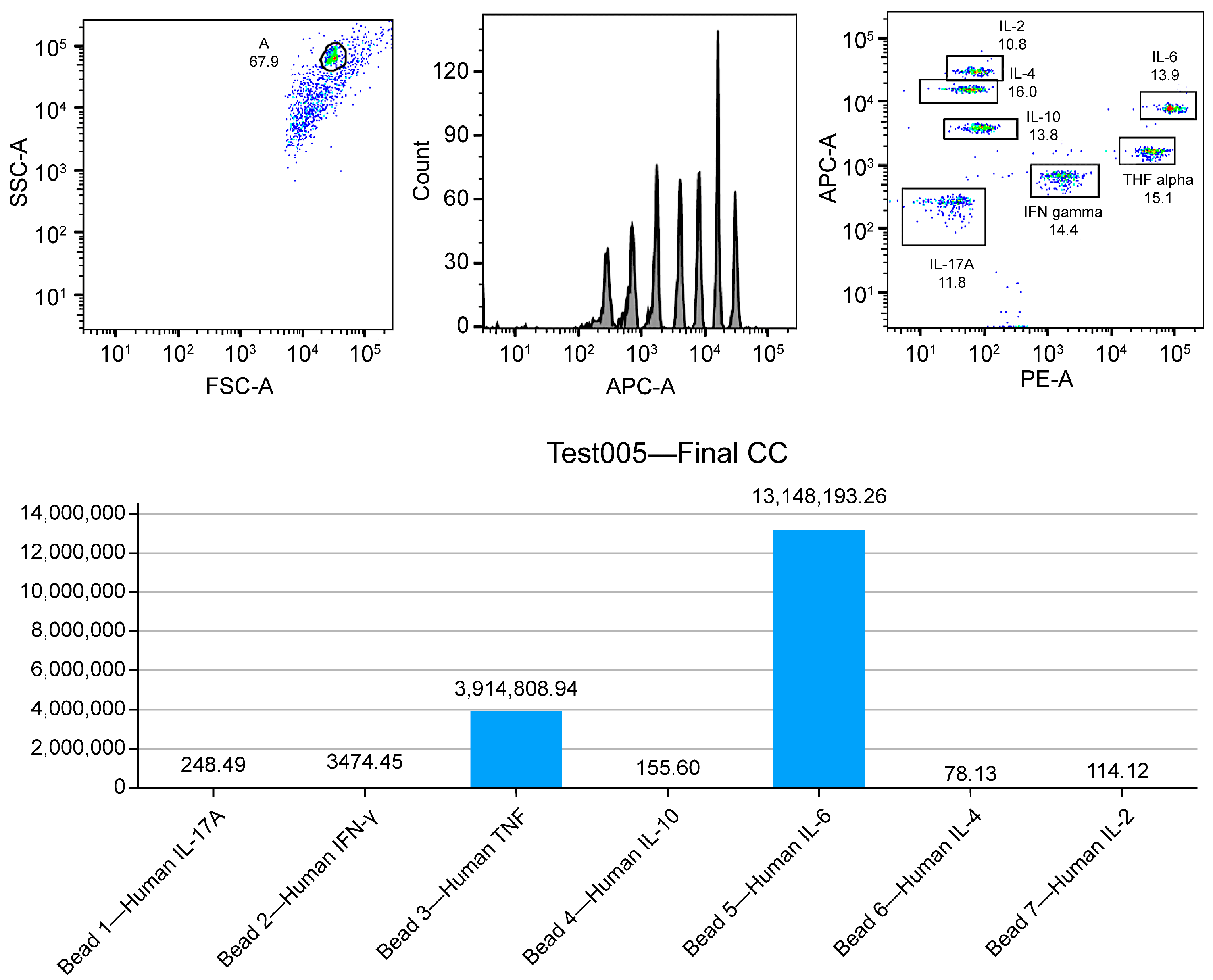

25]. On the other hand, a Th17 profile, related to cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-17A, must be carefully monitored to avoid excessive inflammation and potential adverse side effects (

Figure 4). Flow cytometry and ELISA are fundamental tools for this type of analysis, and, if deviations towards undesired profiles are observed, specific therapeutic adjustments can be implemented [

26].

Measuring apoptosis in tumor cells is a crucial component of immune monitoring, to ensure that activated T cells are effectively eliminating cancer cells. For this purpose, LDH release assays and annexin V and caspase activation are used, which are specific markers of this process. An increase in LDH levels and caspase activation confirm that the treatment is effective [

27]. In cases of suboptimal results, adjustments in the dosage of DCs or exosomes are recommended to improve the efficacy of the therapy [

28].

5. Complementary Clinical Follow-Up

It is crucial to monitor exosome immunotherapy to assess treatment effectiveness and make adjustments based on the patient response. Such monitoring is mainly based on well-established clinical criteria, such as RECIST and iRECIST, which allow objective changes in tumor lesions to be measured [

29]. While RECIST has been widely used to assess the response to conventional therapies, iRECIST has been specifically designed for immunotherapies, addressing unique phenomena such as pseudoprogression, where tumor lesions may temporarily enlarge before showing a reduction due to immune activation [

30].

This type of clinical monitoring is complemented by advanced imaging techniques, such as PET-CT with 18F-FDG, which provides a detailed analysis of the metabolic activity of the tumor. The uptake of this radiopharmaceutical by the tumor tissue is directly related to the aggressiveness and cellular metabolism of the cancer [

31]. This technique is especially useful in the context of immunotherapy, as it can detect early changes in tumor activity, even before a significant reduction in the size of the lesion occurs, allowing a more accurate assessment of the treatment’s efficacy.

Furthermore, the use of tumor biomarkers offers a molecular window into the patient’s response to treatment. Biomarkers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CA-125, and PSA allow indirect measurements of tumor burden and the assessment of disease progression or regression. However, in the context of immunotherapy, these biomarkers may also reflect immune activation. For example, a decrease in PSA levels in prostate cancer patients treated with immunotherapy could indicate a favorable response, while their increase could suggest resistance [

32].

Together, clinical criteria, advanced imaging techniques, and tumor biomarkers provide a comprehensive framework that not only assesses treatment response, but also allows for anticipating relapses, adjusting dosages and administration schedules, and identifying patients who would benefit from a change in therapeutic approach [

33]. The integration of these elements allows for a dynamic and adaptive approach, maximizing the personalization and effectiveness of treatment in cancer patients.

6. Impact of Laboratory Results on Treatment Personalization

Laboratory results obtained through molecular monitoring in immunotherapy with DCs and exosomes play a crucial role in the personalization of oncological treatment. The integration of data derived from T lymphocyte activation, cytokine production, and the evaluation of immunological profiles allows the treatment to be adjusted in real time, maximizing its effectiveness and minimizing the incidence of adverse effects. This personalized approach is especially relevant in the context of immunotherapy, where the response of each patient can differ considerably depending on their baseline immune status, tumor burden, and other individual factors [

34].

6.1. T-Cell Activation and Treatment Adjustments

T-cell activation is a key marker for assessing the efficacy of immunotherapy, measured through the expression of CD69 and CD25, together with the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ and IL-2 [

35]. These markers provide information on the magnitude of the adaptive immune response, which is essential for combating tumor cells. If T-cell activation levels are suboptimal, adjustments to the therapeutic protocol should be made, such as increasing the dose of pulsed DCs, modifying the antigenic load, or selecting more effective immunological adjuvants [

36].

6.2. Th1, Th2, and Th17 Immune Profiles: Influence on Response

Th1, Th2, and Th17 immune profiles directly influence the effectiveness of the immune response [

37]. A predominant Th1 profile, mediated by cytokines such as IFN-γ and IL-12, is ideal for a cytotoxic response directed against cancer. In cases where a predominance of Th2 or Th17 profiles is detected, which could be related to immunosuppressive or proinflammatory responses, respectively, physicians can adjust the treatment by administering Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands or interleukin 12 (IL-12), favoring a Th1 response [

38,

39].

6.3. Evaluation of the Quality and Functionality of Exosomes

Exosomes are essential to amplify the immune response. The evaluation of parameters such as the concentration, size, and protein load of exosomes using techniques such as nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) and Western blotting ensures their functionality [

40,

41]. The presence of key exosomal markers, such as CD63 and CD81, is indicative of the quality of these extracellular vesicles [

42]. The detection of low efficiency in the activation of T lymphocytes or in the production of cytokines can indicate deficiencies in the quality of exosomes, which would necessitate adjustments in their concentration or improvements in their purification [

43].

6.4. Adjustments in Immunotherapy Administration

Depending on the molecular results and the patient’s response, the frequency and dose of the immunotherapy can be adjusted. If T-cell activation levels are high, the frequency of administration could be reduced to avoid overstimulation of the immune system and associated adverse effects [

44]. Conversely, if the response is insufficient, the frequency or dose of pulsed DCs or exosomes could be increased to enhance immune activation [

45].

This dynamic and personalized approach ensures the constant optimization of immunotherapy, adapting to the patient’s progress. The ability to modify the frequency and dose based on patient-specific data differentiates this approach from conventional treatments, offering a considerable advantage in oncological treatment, especially in patients who have not responded to chemotherapy or who are resistant to therapy [

44,

45].

7. Cost Analysis and Protocol Scalability

Pulsed DEXs represent a groundbreaking approach in cancer immunotherapy, offering significant therapeutic potential. However, their implementation faces critical challenges regarding economic viability and scalability, both of which are essential to ensure widespread accessibility for patients. A major factor in this context is the reliance on advanced molecular monitoring technologies, such as flow cytometry and PET-CT imaging, which are indispensable for evaluating immune responses and tumor progression [

46,

47].

Flow cytometry enables the precise quantification of markers that reflect T-cell activation and cytokine production, while PET-CT imaging, particularly with 18F-FDG tracers, provides detailed insights into tumor metabolism and early treatment responses [

48]. Despite their critical role, these techniques require substantial investments in specialized equipment, rigorous maintenance, and highly skilled personnel, presenting considerable economic barriers to their broader adoption [

49].

The integration of such technologies into routine clinical practice further necessitates robust infrastructure and seamless collaboration between research centers and healthcare facilities [

50]. Collaborative efforts, including shared monitoring networks and the use of artificial intelligence for data analysis, hold promise for reducing operational costs while enhancing scalability. Nevertheless, achieving widespread implementation of DEX-based immunotherapies will depend on innovative approaches that balance affordability with the precision required for effective treatment monitoring [

51].

7.1. Cost Analysis

The costs associated with implementing this protocol include the acquisition of specialized equipment such as flow cytometers, automated ELISA systems, and NTA devices [

52]. These items are crucial to ensure quality and accuracy in sample analysis. In addition, operational expenses related to sample collection, data analysis, and the clinical interpretation of results can be high, especially in settings where resources are limited [

53].

However, it is important to note that the initial costs are offset by the clinical benefits that come from personalizing and optimizing treatment. The ability to adjust treatment based on molecular results in real time makes it possible to avoid the administration of unnecessary therapies, thereby reducing the risk of serious adverse effects and the need for prolonged hospitalizations. This, in turn, decreases the overall costs of cancer treatment and improves the quality of life of patients, representing significant economic savings in the long term [

54].

A comparative analysis that weighs upfront costs against long-term savings can be useful to demonstrate the cost-effectiveness of the protocol. This approach provides clear evidence that investment in advanced technologies can result in better management of health resources and more effective treatment [

55,

56].

The comparison of the costs and benefits of the main monitoring techniques used in the protocol is summarized in

Table 3.

7.2. Scalability

Protocol scalability is another critical factor to consider. It largely depends on the automation of processes and the implementation of more accessible technologies that allow its adoption in different clinical contexts. These technologies not only simplify workflows but also ensure the consistency and reproducibility of monitoring results across diverse settings. The integration of artificial intelligence tools for data analysis, such as machine learning algorithms and predictive analytics, can further enhance scalability by streamlining data interpretation and enabling real-time adjustments to treatment protocols. This facilitates the adoption of these protocols in hospitals and clinics worldwide, optimizing resources and improving monitoring efficiency [

57,

58].

Furthermore, the ongoing training of physicians and laboratory technicians in the use of these advanced technologies is crucial to ensure accurate and efficient monitoring, regardless of patient volume. Such training should prioritize hands-on experience and simulations to familiarize staff with both hardware and software components. Developing standardized training programs that include periodic evaluations can help maintain high competency levels, particularly as new technologies emerge [

59].

Another strategy to improve scalability is to foster collaboration between research institutions, treatment centers, and biotechnology companies. This collaboration could involve the creation of shared monitoring networks that pool resources and expertise, reducing the duplication of efforts and associated costs. Additionally, implementing standardized protocols across institutions would simplify regulatory compliance and facilitate data sharing for research purposes, accelerating advancements in personalized immunotherapy [

60,

61].

A detailed analysis comparing the estimated costs associated with automation and institutional collaboration can allow the cost–benefit ratios to be calculated as these protocols are expanded. For example, institutions that invest in shared infrastructure may experience significant reductions in operational expenses over time, enabling them to allocate resources to patient care and further research [

62].

Finally, the costs associated with the implementation of this comprehensive monitoring protocol are more than offset by the reduction in hospitalizations and decrease in serious adverse effects that it achieves. Personalized immunotherapy, when combined with efficient monitoring, minimizes treatment-related complications and optimizes outcomes, ultimately providing substantial savings for both health systems and cancer patients [

63].

8. Conclusions

Exosome-based immunotherapy represents one of the most advanced tools for personalizing and optimizing cancer treatment. Through the integration of clinical and molecular data, treatment can be adjusted in real time, thus improving clinical outcomes and minimizing side effects. This approach is crucial in immunotherapy, where patient responses can be highly variable and largely depend on the appropriate activation of the immune system.

Exosome-based immunotherapy constitutes an advanced tool for personalized cancer treatment. This approach capitalizes on the integration of clinical scales (RECIST, iRECIST) and molecular tools (e.g., flow cytometry, ELISA) to enable real-time adjustments to therapeutic strategies. Such integration not only enhances clinical outcomes but also minimizes adverse effects, reinforcing its applicability in highly variable patient populations. By offering a multidimensional evaluation framework, this method fosters precision and adaptability, ensuring that each treatment protocol aligns with the patient's unique immune and tumor microenvironment characteristics. This level of personalization is particularly critical in immunotherapy, as patient responses can vary significantly depending on the immune system's baseline status and the specific characteristics of their tumor microenvironment [

64,

65].

The implementation of a comprehensive monitoring protocol that incorporates both traditional clinical parameters (such as RECIST and iRECIST) and detailed molecular analyses (e.g., flow cytometry, ELISA, and PET-CT) is essential for ensuring the efficacy and safety of these treatments. Clinical scales like RECIST evaluate the tumor response through imaging, while molecular tools provide deeper insights into immune activity and treatment-induced apoptosis. Together, these methodologies offer a multidimensional evaluation framework, allowing for the precise tailoring of therapies to individual patient profiles [

66].

A key feature of this protocol is the ability to adjust treatment strategies based on critical immune parameters, including T-cell activation levels, immune polarization profiles (Th1, Th2, and Th17), and tumor apoptosis markers. For instance, a Th1-dominant profile, characterized by cytokines such as IFN-γ and IL-12, is ideal for promoting a robust cytotoxic response. Conversely, the presence of a Th2 or Th17 profile may require therapeutic adjustments to mitigate immunosuppression or excessive inflammation [

67,

68]. These adjustments ensure that each patient receives a treatment regimen optimized for their specific immune and tumor characteristics.

The integration of these tools and techniques represents a significant advancement in the field of oncology, combining precision medicine with a deep understanding of immunological dynamics. Future research should focus on refining these protocols and expanding their accessibility to a broader range of patients, ultimately enhancing the therapeutic potential of exosome-based immunotherapy. The summarized immune profiles (Th1, Th2, Th17) and their associated cytokines, along with their effects on immunotherapy, are detailed in

Table 4 [

69].

In addition to the clinical benefits, comprehensive monitoring programs exert a profound economic impact. While the initial costs of implementing such programs may be high, the long-term savings derived from treatment optimization, reduced hospitalizations, and the minimization of adverse effects significantly outweigh the upfront investment. This cost-effectiveness is further amplified by advances in technology, such as artificial intelligence and automated data analysis, which are expected to drive down implementation costs over time, thereby broadening access to these protocols for a larger patient population [

70,

71].

The future success of immunotherapy with DCs and exosomes hinges on the scalability of these monitoring systems. Key to achieving this scalability will be the automation of laboratory processes and the adoption of high-throughput data analysis platforms, which are critical for maintaining the sustainability of these treatments at a population level. Furthermore, fostering collaboration among research institutions, hospitals, and treatment centers will play a pivotal role in ensuring equitable resource distribution and facilitating the widespread adoption of these innovative therapies [

72].

Moreover, these protocols enable the precise evaluation of crucial therapeutic parameters, including cell viability, T-cell activation, and the production of key cytokines, such as IFN-γ and IL-12. Such detailed assessments are indispensable for confirming the efficacy of the therapy and tailoring it to the specific needs of individual patients, as demonstrated in

Table 5 [

73,

74].

In conclusion, thorough monitoring is not only key to optimizing DC and exosome immunotherapy, but is also essential to ensure that each patient receives safe, effective, and personalized treatment. With the advancement of technologies and the continued development of new therapeutic strategies, these personalized approaches are likely to become the standard of care for cancer treatment in the future.

9. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite significant advances in immunotherapy with DCs and exosomes, there are several limitations inherent to this therapeutic approach. These limitations are the result of the biological complexity of tumors and the variability in patient responses. Factors such as the total tumor burden, the patient’s baseline immune status, the presence of comorbidities, and the specific genetic profile can significantly influence the effectiveness of the treatment [

75].

9.1. Limitations in the Immune Response

Variability in the immune response is one of the main barriers to the overall success of immunotherapy. Not all patients respond in the same way to therapy, which may be related to differences in the composition of the tumor microenvironment, the presence of immunosuppressive cells, and the intrinsic capacity of each individual’s immune system [

76]. Furthermore, tumor cell heterogeneity can lead to immune system evasion, hindering the effectiveness of exosomes and DCs [

77].

9.2. Future Directions in Research

Addressing these limitations requires deeper exploration of the mechanisms governing immune responses in cancer patients, particularly those involving tumor microenvironment heterogeneity and immune evasion. Preclinical models and multi-phase clinical trials are essential to identify strategies that optimize T-cell activation and improve the efficacy of DC- and exosome-based therapies. Moreover, the integration of emerging technologies, such as single-cell sequencing and artificial intelligence-driven data analysis, holds significant promise for real-time therapeutic adjustments. Collaborative efforts among research institutions and healthcare providers will be critical in accelerating the implementation of these personalized approaches. [

78]. The personalization of immunotherapy, considering genetic and molecular factors, will be crucial to improve effectiveness and reduce side effects [

79].

Furthermore, the development of emerging technologies, such as gene editing and artificial intelligence, could offer new opportunities to optimize therapies and predict responses in real time. The implementation of advanced monitoring platforms will allow for the continuous adaptation of therapeutic strategies based on individual patient responses [

80].

9.3. Interdisciplinary Collaborations

Fostering collaboration across disciplines, including molecular biology, oncology, and bioinformatics, will be essential to create a comprehensive approach to addressing the complexities of cancer treatment. Research networks and consortia can facilitate the sharing of data and resources, accelerating the development of new therapies and monitoring strategies [

81].

In conclusion, immunotherapy with DCs and exosomes has shown significant potential in the treatment of cancer and will undoubtedly be of great benefit to continued research and in addressing current limitations. A multidisciplinary approach and the integration of new technologies may open up new avenues to increase the effectiveness of these treatments in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G.-S. and F.G.C.; methodology, F.G.C and A.S.; software, A.T.; validation, F.G.C., N.M.G., I.R., J.I., F.K., A.S., and I.M.; laboratory and investigation, L.A., A.L., J.I., F.K., W.D., D.M., A.S., and R.A.; resources, F.G.C. and R.A.; data curation, N.M.G., I.R., and A.T.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G.-S. and F.G.C.; writing—review and editing, R.G.-S. and F.G.C; visualization, A.T.; supervision, R.G.-S., F.K., and J.I.; project administration, R.G.-S.; funding acquisition, R.G.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the clinical, administrative, and technical staff of the biotechnological research centers and international laboratories mentioned at the beginning of this article. Their dedicated work and professional expertise make the daily advancement of scientific research and the collection of valuable data possible, contributing significantly to the development of this article’s content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| DC |

Dendritic Cell |

| DEX |

Dendritic Cell-Derived Exosome |

| PBMC |

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell |

| GM-CSF |

Granulocyte–Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor |

| TNF-α |

Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| IL-4 |

Interleukin 4 |

| IL-1β |

Interleukin 1 Beta |

| RECIST |

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors |

| iRECIST |

Immune Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| PET-CT |

Positron Emission Tomography–Computed Tomography |

| CEA |

Carcinoembryonic Antigen |

| CA-125 |

Cancer Antigen 125 |

| PSA |

Prostate-Specific Antigen |

| CD |

Cluster of Differentiation |

| Th1, Th2, Th17 |

T Helper Cell Subtypes |

| IFN-γ |

Interferon Gamma |

| LDH |

Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| NTA |

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis |

| HLA-DR |

Human Leukocyte Antigen–DR Isotype |

| CD80, CD83, CD63, CD81 |

Cell Differentiation Markers |

| TLR |

Toll-Like Receptor |

| FSC-A |

Forward Scatter Area |

| SSC-A |

Side Scatter Area |

| APC-A |

Allophycocyanin Area |

| PE |

Phycoerythrin |

| CBA |

Cytometric Bead Array |

| pg/mL |

Picograms per milliliter |

References

- Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Sun, M.; Cui, Y.; Xing, J.; Teng, L.; Xi, Z.; Yang, Z. Exosomes as smart drug delivery vehicles for cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 13, 1093607. [CrossRef]

- Lee KW; Yam JWP; Mao X. Dendritic cell vaccines: A shift from conventional approach to new generations. Cells 2023, 12, 2147. [CrossRef]

- Tojjari A; Saeed A; Singh M; Cavalcante L; Sahin IH; Saeed A. A comprehensive review on cancer vaccines and vaccine strategies in hepatocellular carcinoma. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1357. [CrossRef]

- Gardner A; de Mingo Pulido Á; Ruffell B. Dendritic cells and their role in immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 924. [CrossRef]

- Cai Y; Prochazkova M; Kim YS; Jiang C; Ma J; Moses L; et al. Assessment and comparison of viability assays for cellular products. Cytotherapy 2024, 26, 201–209. [CrossRef]

- Seymour L; Bogaerts J; Perrone A; Ford R; Schwartz LH; Mandrekar S; Lin NU; Litière S; Dancey J; Chen A; Hodi FS; Therasse P; Hoekstra OS; Shankar LK; Wolchok JD; Ballinger M; Caramella C; de Vries EGE; RECIST working group. iRECIST: guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, e143-e152.

- Vladimirov N; Perlman O. Molecular MRI-based monitoring of cancer immunotherapy treatment response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3151. [CrossRef]

- Gu YZ; Zhao X; Song XR. Ex vivo pulsed dendritic cell vaccination against cancer. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 959-969. [CrossRef]

- Liu C; Yang M; Zhang D; Chen M; Zhu D. Clinical cancer immunotherapy: Current progress and prospects. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 961805. [CrossRef]

- Connor L; Dean J; McNett M; Tydings DM; Shrout A; Gorsuch PF; Hole A; Moore L; Brown R; Melnyk BM; Gallagher-Ford L. Evidence-based practice improves patient outcomes and healthcare system return on investment: Findings from a scoping review. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2023, 20, 6-15. [CrossRef]

- Couchoud C; Fagnoni P; Aubin F; Westeel V; Maurina T; Thiery-Vuillemin A; Gerard C; Kroemer M; Borg C; Limat S; Nerich V. Economic evaluations of cancer immunotherapy: a systematic review and quality evaluation. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2020, 69, 1947-1958.

- Singh S; Paul D; Nath V. Exosomes: Current knowledge and future perspectives. Tissue Barriers 2024, 12, 2232248. [CrossRef]

- Marques HS; de Brito BB; da Silva FAF; Santos MLC; de Souza JCB; Correia TML; Lopes LW; Neres NSM; Dórea RSDM; Dantas ACS; Morbeck LLB; Lima IS; de Almeida AA; Dias MRJ; de Melo FF. Relationship between Th17 immune response and cancer. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 12, 845-867.

- Masucci M; Karlsson C; Blomqvist L; Ernberg I. Bridging the divide: A review on the implementation of personalized cancer medicine. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 561. [CrossRef]

- Jin P; Han TH; Ren J; et al. Molecular signatures of maturing dendritic cells: implications for testing the quality of dendritic cell therapies. J. Transl. Med. 2010, 8, 4. [CrossRef]

- Leng SX; McElhaney JE; Walston JD; Xie D; Fedarko NS; Kuchel GA. ELISA and multiplex technologies for cytokine measurement in inflammation and aging research. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2008, 63, 879-884. [CrossRef]

- Mucherino S; Lorenzoni V; Orlando V; Triulzi I; Del Re M; Capuano A; Danesi R; Turchetti G; Menditto E. Cost-effectiveness of treatment optimisation with biomarkers for immunotherapy in solid tumours: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e048141. [CrossRef]

- Liu R; Zhao Y; Shi F; Zhu J; Wu J; Huang M; Qiu K. Cost-effectiveness analysis of immune checkpoint inhibitors as first-line therapy in advanced biliary tract cancer. Immunotherapy 2024, 16, 669-678. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Sandoval R; Gutierrez-Castro F; Rivadeneira I; Krakowiak F; Iturra J. Advances in the translational application of immunotherapy with pulsed dendritic cell-derived exosomes. J. Clin. Biomed. Res. 2024, 6, 1-8.

- Araujo-Abad S; Berna JM; Lloret-Lopez E; López-Cortés A; Saceda M; de Juan Romero C. Exosomes: from basic research to clinical diagnostic and therapeutic applications in cancer. Cell Oncol. 2024, 47, -. [CrossRef]

- Tian H; Li W. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes for cancer immunotherapy: hope and challenges. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5, 221. [CrossRef]

- Fu P; Yin S; Cheng H; Xu W; Jiang J. Engineered exosomes for drug delivery in cancer therapy: A promising approach and application. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2024, 21, 817-827. [CrossRef]

- Marciscano AE; Anandasabapathy N. The role of dendritic cells in cancer and anti-tumor immunity. Semin. Immunol. 2021, 52, 101481. [CrossRef]

- Ganjalikhani Hakemi M; Yanikkaya Demirel G; Li Y; Jayakumar N. The immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and strategies to revert its immune regulatory milieu for cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1238698.

- Huangfu S; Pan J. Novel biomarkers for predicting response to cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1179913. [CrossRef]

- Karlsen W; Akily L; Mierzejewska M; Teodorczyk J; Bandura A; Zaucha R; Cytawa W. Is 18F-FDG-PET/CT an optimal imaging modality for detecting immune-related adverse events after immune-checkpoint inhibitor therapy? Pros and cons. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16, 1990. [CrossRef]

- Bi WL; Hosny A; Schabath MB; Giger ML; Birkbak NJ; Mehrtash A; Allison T; Arnaout O; Abbosh C; Dunn IF; Mak RH; Tamimi RM; Tempany CM; Swanton C; Hoffmann U; Schwartz LH; Gillies RJ; Huang RY; Aerts HJWL. Artificial intelligence in cancer imaging: Clinical challenges and applications. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 127-157.

- Sidiropoulos DN; Stein-O'Brien GL; Danilova L; Gross NE; Charmsaz S; Xavier S; Leatherman J; Wang H; Yarchoan M; Jaffee EM; Fertig EJ; Ho WJ. Integrated T cell cytometry metrics for immune-monitoring applications in immunotherapy clinical trials. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e160398.

- Schmitt A; Hus I; Schmitt M. Dendritic cell vaccines for leukemia patients. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2007, 7, 275-283. [CrossRef]

- Safaei S; Fadaee M; Farzam OR; Yari A; Poursaei E; Aslan C; Samemaleki S; Shanehbandi D; Baradaran B; Kazemi T. Exploring the dynamic interplay between exosomes and the immune tumor microenvironment: implications for breast cancer progression and therapeutic strategies. Breast Cancer Res. 2024, 26, 57. [CrossRef]

- Louie AD; Huntington K; Carlsen L; Zhou L; El-Deiry WS. Integrating molecular biomarker inputs into development and use of clinical cancer therapeutics. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 747194. [CrossRef]

- Zou W; Restifo NP. T(H)17 cells in tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 248-256.

- Bergholz JS; Wang Q; Kabraji S; Zhao JJ. Integrating immunotherapy and targeted therapy in cancer treatment: Mechanistic insights and clinical implications. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 5557-5566. [CrossRef]

- Abou-El-Enein M; Elsallab M; Feldman SA; Fesnak AD; Heslop HE; Marks P; Till BG; Bauer G; Savoldo B. Scalable manufacturing of CAR T cells for cancer immunotherapy. Blood Cancer Discov. 2021, 2, 408-422.

- Bol KF; Mensink HW; Aarntzen EH; Schreibelt G; Keunen JE; Coulie PG; de Klein A; Punt CJ; Paridaens D; Figdor CG; de Vries IJ. Long overall survival after dendritic cell vaccination in metastatic uveal melanoma patients. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 158, 939-947.

- Palucka K; Banchereau J. Dendritic-cell-based therapeutic cancer vaccines. Immunity 2013, 39, 38-48. [CrossRef]

- Pitt JM; Charrier M; Viaud S; André F; Besse B; Chaput N; Zitvogel L. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes as immunotherapies in the fight against cancer. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 1006-1011. [CrossRef]

- Waldmann TA. Cytokines in cancer immunotherapy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018, 10, a028472. [CrossRef]

- Xu Z; Zeng S; Gong Z; et al. Exosome-based immunotherapy: a promising approach for cancer treatment. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 160. [CrossRef]

- Escudier B; Dorval T; Chaput N; André F; Caby MP; Novault S; Flament C; Leboulaire C; Borg C; Amigorena S; Boccaccio C; Bonnerot C; Dhellin O; Movassagh M; Piperno S; Robert C; Serra V; Valente N; Le Pecq JB; Spatz A; Lantz O; Tursz T; Angevin E; Zitvogel L. Vaccination of metastatic melanoma patients with autologous dendritic cell (DC) derived-exosomes: Results of the first phase I clinical trial. J. Transl. Med. 2005, 3, 10.

- Wu J; Shen Z. Exosomal miRNAs as biomarkers for diagnostic and prognostic in lung cancer. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 6909-6922. [CrossRef]

- Saida Y; Watanabe S; Koyama S; Togashi Y; Kikuchi T. Strategies to overcome tumor evasion and resistance to immunotherapies by targeting immune suppressor cells. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1240926. [CrossRef]

- Sheikhlary S; Lopez DH; Moghimi S; Sun B. Recent findings on therapeutic cancer vaccines: An updated review. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 503. [CrossRef]

- Lim HX; Hong HJ; Jung MY; Cho D; Kim TS. Principal role of IL-12p40 in the decreased Th1 and Th17 responses driven by dendritic cells of mice lacking IL-12 and IL-18. Cytokine 2013, 63, 179-186. [CrossRef]

- Kim CR; Kim B; Ning MS; Reddy JP; Liao Z; Tang C; Welsh JW; Mott FE; Shih YT; Gomez DR. Cost analysis of PET/CT versus CT as surveillance for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer after definitive radiation therapy. Clin. Lung Cancer 2018, 19, e517-e528. [CrossRef]

- Olson BM; McNeel DG. Monitoring regulatory immune responses in tumor immunotherapy clinical trials. Front. Oncol. 2013, 3, 109. [CrossRef]

- Deng M; Wu S; Huang P; Liu Y; Li C; Zheng J. Engineered exosomes-based theranostic strategy for tumor metastasis and recurrence. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 18, 100870. [CrossRef]

- Lee KW; Yam JWP; Mao X. Dendritic cell vaccines: A shift from conventional approach to new generations. Cells 2023, 12, 2147. [CrossRef]

- Shalaby N; Dubois VP; Ronald J. Molecular imaging of cellular immunotherapies in experimental and therapeutic settings. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2022, 71, 1281-1294. [CrossRef]

- Sathyanarayanan V; Neelapu SS. Cancer immunotherapy: Strategies for personalization and combinatorial approaches. Mol. Oncol. 2015, 9, 2043-2053. [CrossRef]

- Pitt JM; André F; Amigorena S; Soria JC; Eggermont A; Kroemer G; Zitvogel L. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes for cancer therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 2016, 126, 1224-1232.

- Das S; Dey MK; Devireddy R; Gartia MR. Biomarkers in cancer detection, diagnosis, and prognosis. Sensors (Basel) 2023, 24, 37.

- Bhavsar D; Raguraman R; Kim D; Ren X; Munshi A; Moore K; Sikavitsas V; Ramesh R. Exosomes in diagnostic and therapeutic applications of ovarian cancer. J. Ovarian Res. 2024, 17, 113.

- Pham TD; Teh MT; Chatzopoulou D; Holmes S; Coulthard P. Artificial intelligence in head and neck cancer: Innovations, applications, and future directions. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 5255-5290. [CrossRef]

- Wandrey M; Jablonska J; Stauber RH; Gül D. Exosomes in cancer progression and therapy resistance: Molecular insights and therapeutic opportunities. Life (Basel) 2023, 13, 2033. [CrossRef]

- Yao Y; Fu C; Zhou L; Mi QS; Jiang A. DC-derived exosomes for cancer immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 3667. [CrossRef]

- Lee S; Margolin K. Cytokines in cancer immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2011, 3, 3856-3893. [CrossRef]

- Subbiah V; Murthy R; Hong DS; Prins RM; Hosing C; Hendricks K; Kolli D; Noffsinger L; Brown R; McGuire M; Fu S; Piha-Paul S; Naing A; Conley AP; Benjamin RS; Kaur I; Bosch ML. Cytokines produced by dendritic cells administered intratumorally correlate with clinical outcome in patients with diverse cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 3845-3856.

- Gonzalez-Angulo AM; Hennessy BT; Mills GB. Future of personalized medicine in oncology: a systems biology approach. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 2777-2783. [CrossRef]

- Yu X; Ibrahim SM. Evidence of a role for Th17 cells in the breach of immune tolerance in arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011, 13, 132. [CrossRef]

- Shang N; Figini M; Shangguan J; Wang B; Sun C; Pan L; Ma Q; Zhang Z. Dendritic cells based immunotherapy. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2017, 7, 2091-2102.

- Pathania AS; Prathipati P; Challagundla KB. New insights into exosome mediated tumor-immune escape: Clinical perspectives and therapeutic strategies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2021, 1876, 188624. [CrossRef]

- Vu SH; Vetrivel P; Kim J; Lee MS. Cancer resistance to immunotherapy: Molecular mechanisms and tackling strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10906. [CrossRef]

- Zanotta S; Galati D; De Filippi R; Pinto A. Enhancing dendritic cell cancer vaccination: The synergy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in combined therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7509. [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari Laleh N; Ligero M; Perez-Lopez R; Kather JN. Facts and hopes on the use of artificial intelligence for predictive immunotherapy biomarkers in cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 316-323. [CrossRef]

- Lai JJ; Chau ZL; Chen SY; Hill JJ; Korpany KV; Liang NW; Lin LH; Liu JK. Exosome processing and characterization approaches for research and technology development. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.) 2022, 9, e2103222. [CrossRef]

- Bhinder B; Gilvary C; Madhukar NS; Elemento O. Artificial intelligence in cancer research and precision medicine. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 900-915. [CrossRef]

- van Gulijk M; Dammeijer F; Aerts JGJV; Vroman H. Combination strategies to optimize efficacy of dendritic cell-based immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2759. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Z; Wang J; Wang J; Yang S; Wang R; Zhang G; Li Z; Shi R. Deciphering the tumor immune microenvironment from a multidimensional omics perspective: Insight into next-generation CAR-T cell immunotherapy and beyond. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 131. [CrossRef]

- Song MS; Nam JH; Noh KE; Lim DS. Dendritic cell-based immunotherapy: The importance of dendritic cell migration. J. Immunol. Res. 2024, 2024, 7827246. [CrossRef]

- Lyakh L; Trinchieri G; Provezza L; Carra G; Gerosa F. Regulation of interleukin-12/interleukin-23 production and the T-helper 17 response in humans. Immunol. Rev. 2008, 226, 112-131.

- Makler A; Asghar W. Exosomal biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and patient monitoring. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2020, 20, 387-400. [CrossRef]

- Dumbrava EI; Meric-Bernstam F. Personalized cancer therapy-leveraging a knowledge base for clinical decision-making. Cold Spring Harb. Mol. Case Stud. 2018, 4, a001578. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q; Li S; Dupuy A; Mai HL; Sailliet N; Logé C; Robert JH; Brouard S. Exosomes as new biomarkers and drug delivery tools for the prevention and treatment of various diseases: Current perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7763. [CrossRef]

- Hato L; Vizcay A; Eguren I; Pérez-Gracia JL; Rodríguez J; Gállego Pérez-Larraya J; Sarobe P; Inogés S; Díaz de Cerio AL; Santisteban M. Dendritic cells in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16, 981.

- Sajan A; Lamane A; Baig A; Floch KL; Dercle L. The emerging role of AI in enhancing intratumoral immunotherapy care. Oncotarget 2024, 15, 635-637. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z; Wang Q; Qin F; Chen J. Exosomes: a promising avenue for cancer diagnosis beyond treatment. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1344705. [CrossRef]

- Zhao N; Yi Y; Cao W; Fu X; Mei N; Li C. Serum cytokine levels for predicting immune-related adverse events and the clinical response in lung cancer treated with immunotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 923531. [CrossRef]

- Kamigaki T; Takimoto R; Okada S; Ibe H; Oguma E; Goto S. Personalized dendritic-cell-based vaccines targeting cancer neoantigens. Anticancer Res. 2024, 44, 3713-3724. [CrossRef]

- Sabado RL; Balan S; Bhardwaj N. Dendritic cell-based immunotherapy. Cell Res. 2017, 27, 74-95.

- Luo S; Chen J; Xu F; Chen H; Li Y; Li W. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes in cancer immunotherapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2070. [CrossRef]

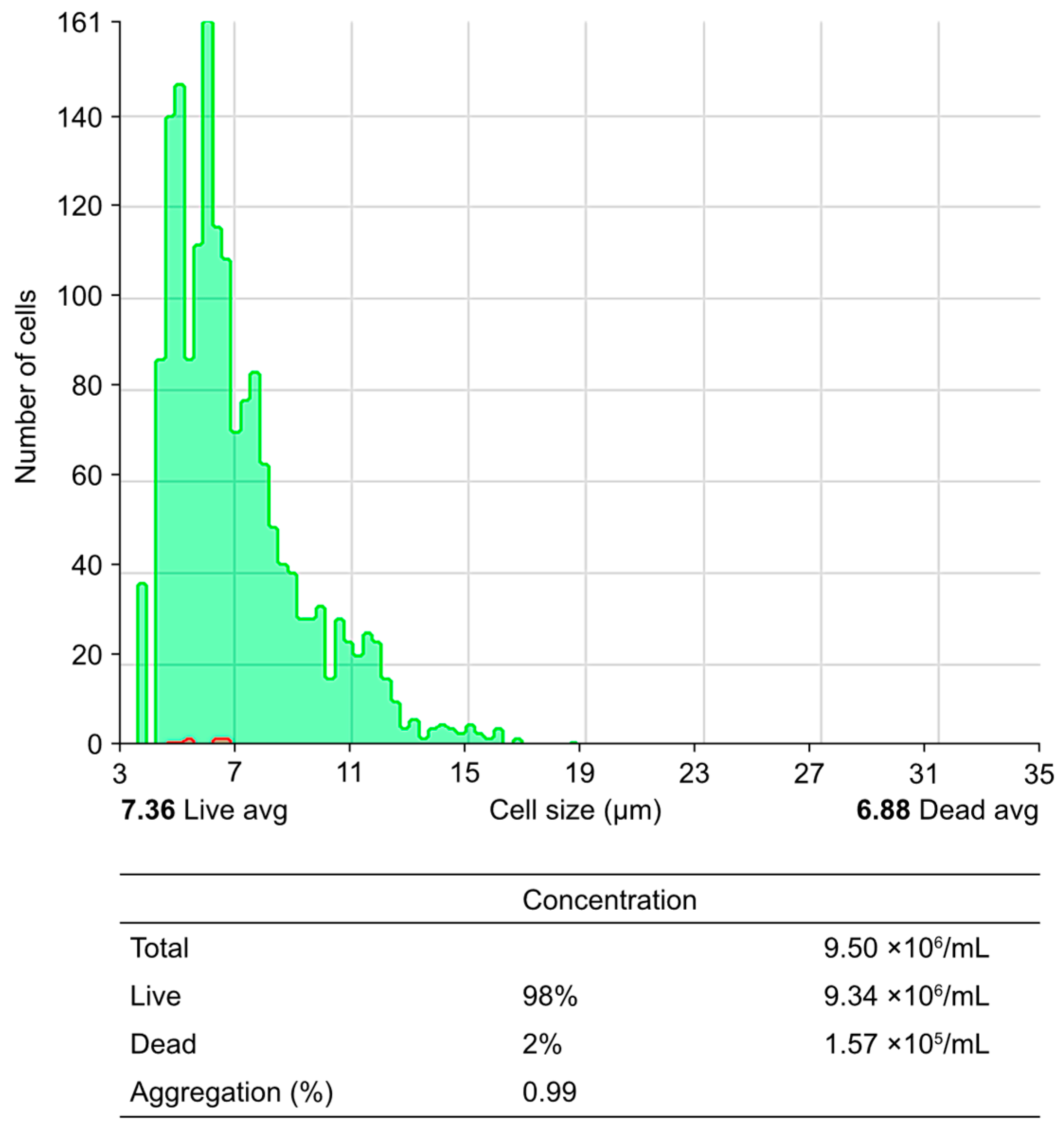

Figure 1.

Obtaining peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from peripheral blood using a Ficoll–Hypaque gradient: the process of obtaining PBMCs through a density gradient via centrifugation is illustrated. The upper histogram illustrates the cell size and cell count per analyzed field, differentiating between live cells (green area) and dead cells (red area). The lower table corresponds to the quantification of live and dead cells through analysis with the Countess 3 Automated Cell Counter (number of PBMCs per mL before the seeding process).

Figure 1.

Obtaining peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from peripheral blood using a Ficoll–Hypaque gradient: the process of obtaining PBMCs through a density gradient via centrifugation is illustrated. The upper histogram illustrates the cell size and cell count per analyzed field, differentiating between live cells (green area) and dead cells (red area). The lower table corresponds to the quantification of live and dead cells through analysis with the Countess 3 Automated Cell Counter (number of PBMCs per mL before the seeding process).

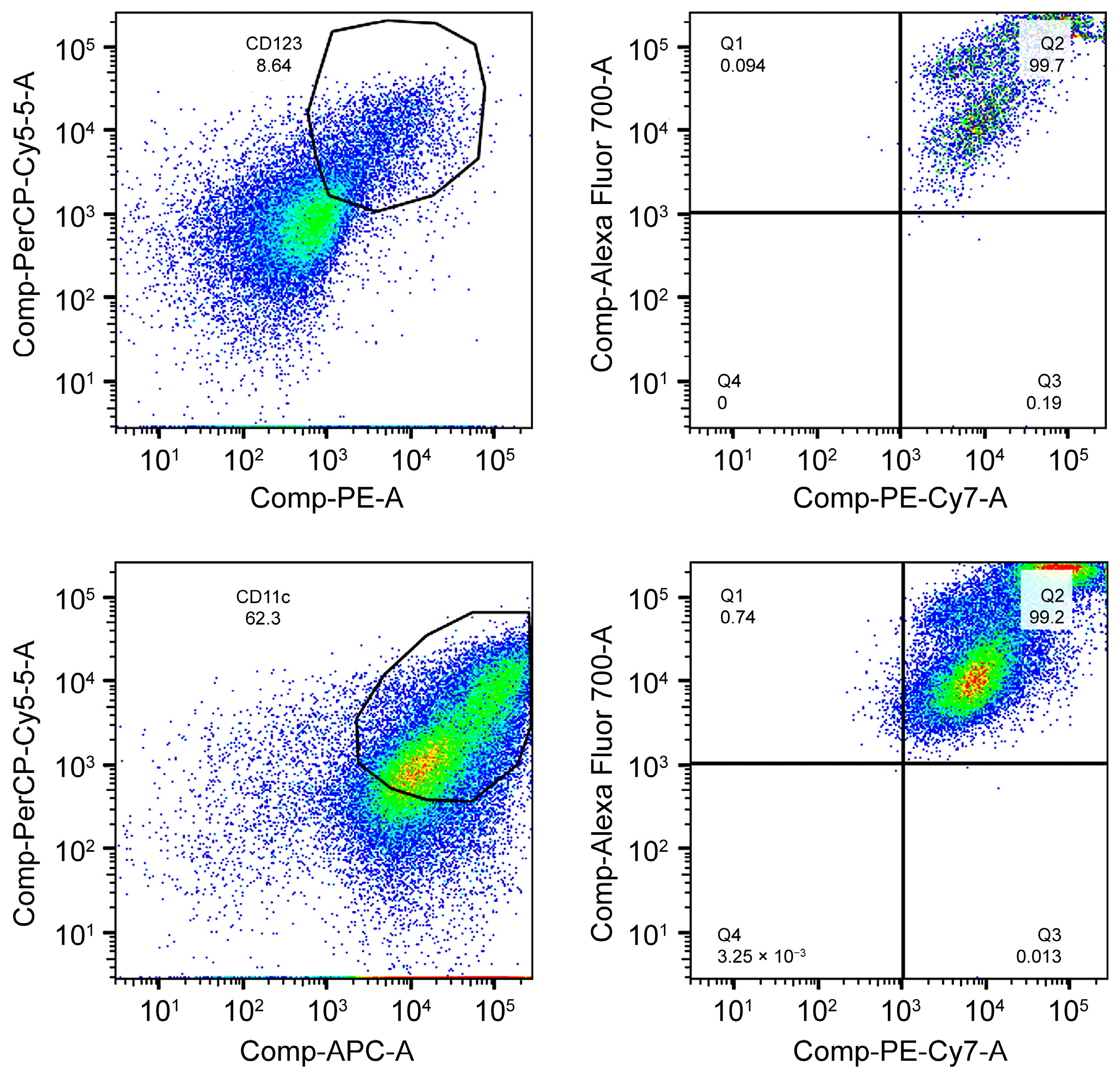

Figure 2.

Monitoring of the expression of CD subpopulations in in vitro culture. The expression of the plasmacytoid dendritic cell (DC) subpopulation at the in vitro level is shown. The graphs show, in the upper left corner, a flow cytometry dot plot showing the CD population based on analyzing the expression of the HLA-DR (PerCP-Cy5.5) and CD123 (PE) markers. On the right is a flow cytometry dot plot showing the CD+ population for CD80 (Alexa fluor 700) and CD83 (PE-Cy7). At the bottom, the expression of the myeloid DC subpopulation at the in vitro level is shown. On the left is a flow cytometry dot plot showing the CD population based on analyzing the expression of the HLA-DR (PerCP-Cy5.5) and CD11c (APC) markers. On the right is a flow cytometry dot plot showing the CD+ population for CD80 (Alexa fluor 700) and CD83 (PE-Cy7).

Figure 2.

Monitoring of the expression of CD subpopulations in in vitro culture. The expression of the plasmacytoid dendritic cell (DC) subpopulation at the in vitro level is shown. The graphs show, in the upper left corner, a flow cytometry dot plot showing the CD population based on analyzing the expression of the HLA-DR (PerCP-Cy5.5) and CD123 (PE) markers. On the right is a flow cytometry dot plot showing the CD+ population for CD80 (Alexa fluor 700) and CD83 (PE-Cy7). At the bottom, the expression of the myeloid DC subpopulation at the in vitro level is shown. On the left is a flow cytometry dot plot showing the CD population based on analyzing the expression of the HLA-DR (PerCP-Cy5.5) and CD11c (APC) markers. On the right is a flow cytometry dot plot showing the CD+ population for CD80 (Alexa fluor 700) and CD83 (PE-Cy7).

Figure 4.

The monitoring of Th1, Th2, and Th17 cytokines in the secretome of mature dendritic cells using the Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) technique is shown. The upper panels display: (i) a Dot Plot (FSC-A vs SSC-A) used to select specific cellular events, where the X-axis represents cell size (FSC-A) and the Y-axis represents internal complexity (SSC-A); (ii) a Histogram (APC-A) illustrating the distribution of events based on fluorescence intensity (APC-A on the X-axis) and event count (Y-axis); and (iii) a Dot Plot (APC-A vs PE) analyzing fluorescence intensities associated with Th1, Th2, and Th17 cytokines, with PE on the X-axis and APC-A on the Y-axis. The lower graph presents the obtained and normalized concentrations (pg/mL) of the different cytokines, where the X-axis lists the analyzed cytokines (IL-17A, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-10, IL-6, IL-4, and IL-2), and the Y-axis represents their respective concentrations. The results highlight IL-6 and TNF-α as the most abundant cytokines, reflecting the immune response in the secretome of mature dendritic cells.

Figure 4.

The monitoring of Th1, Th2, and Th17 cytokines in the secretome of mature dendritic cells using the Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) technique is shown. The upper panels display: (i) a Dot Plot (FSC-A vs SSC-A) used to select specific cellular events, where the X-axis represents cell size (FSC-A) and the Y-axis represents internal complexity (SSC-A); (ii) a Histogram (APC-A) illustrating the distribution of events based on fluorescence intensity (APC-A on the X-axis) and event count (Y-axis); and (iii) a Dot Plot (APC-A vs PE) analyzing fluorescence intensities associated with Th1, Th2, and Th17 cytokines, with PE on the X-axis and APC-A on the Y-axis. The lower graph presents the obtained and normalized concentrations (pg/mL) of the different cytokines, where the X-axis lists the analyzed cytokines (IL-17A, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-10, IL-6, IL-4, and IL-2), and the Y-axis represents their respective concentrations. The results highlight IL-6 and TNF-α as the most abundant cytokines, reflecting the immune response in the secretome of mature dendritic cells.

Table 1.

Summary of the main markers used to evaluate viability and immune activation in DC- and exosome-based immunotherapy. The evaluation methods used allow precise data on the effectiveness of T-cell activation and DC maturation to be obtained, which is essential for optimizing the immune responses in cancer patients.

Table 1.

Summary of the main markers used to evaluate viability and immune activation in DC- and exosome-based immunotherapy. The evaluation methods used allow precise data on the effectiveness of T-cell activation and DC maturation to be obtained, which is essential for optimizing the immune responses in cancer patients.

| Marker |

Description |

Evaluation Method |

Expected Value |

| CD69 |

Early marker of T-cell activation |

Flow cytometry |

>70% activated lymphocytes |

| CD25 |

Late activation marker and regulatory function |

Flow cytometry |

>60% activated lymphocytes |

| HLA-DR |

DC maturation marker |

Flow cytometry |

High expression (>80%) |

| IFN-γ |

Key cytokine for Th1 polarization |

ELISA |

>100 pg/mL |

| IL-12 |

Cytokine for the induction of Th1 response |

ELISA |

>80 pg/mL |

Table 2.

Key features of dendritic cell-derived exosomes (DEXs), along with the methods used for their evaluation. Maintaining these parameters within optimal ranges is crucial to ensure the structural stability and functionality of exosomes as immunological signaling vehicles in oncology immunotherapy.

Table 2.

Key features of dendritic cell-derived exosomes (DEXs), along with the methods used for their evaluation. Maintaining these parameters within optimal ranges is crucial to ensure the structural stability and functionality of exosomes as immunological signaling vehicles in oncology immunotherapy.

| Parameter |

Description |

Evaluation Method |

Optimal Range |

| Size |

Average diameter of exosomes |

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) |

100–150 nm |

| Concentration |

Number of exosomes per mL of sample |

NTA |

>109 particles/mL |

| CD63 |

Exosome-specific surface marker |

Western blotting |

Positive expression |

| CD81 |

Extracellular vesicle marker |

Western blotting |

Positive expression |

| Alix |

Marker of exosome integrity and biogenesis |

Western blotting |

Positive expression |

Table 3.

Cost–benefit comparison of the different monitoring techniques used in immunotherapy, highlighting their approximate costs and clinical benefits. Flow cytometry, PET-CT, and NTA are essential tools for evaluating the effectiveness of the treatment and adjusting the protocol based on the results obtained.

Table 3.

Cost–benefit comparison of the different monitoring techniques used in immunotherapy, highlighting their approximate costs and clinical benefits. Flow cytometry, PET-CT, and NTA are essential tools for evaluating the effectiveness of the treatment and adjusting the protocol based on the results obtained.

| Monitoring Technique |

Approximate Cost |

Benefits |

| Flow cytometry |

High |

High precision in the quantification of cellular markers |

| PET-CT with 18F-FDG |

Very high |

Early detection of metabolic changes in the tumor |

| NTA |

Moderate |

Accurate assessment of exosome size and concentration |

Table 4.

Th1, Th2, and Th17 immune profiles, detailing key associated cytokines and their impact on the effectiveness of DC- and exosome-based immunotherapy. Understanding and monitoring these profiles is critical to optimizing the therapeutic strategy based on the patient’s immune response.

Table 4.

Th1, Th2, and Th17 immune profiles, detailing key associated cytokines and their impact on the effectiveness of DC- and exosome-based immunotherapy. Understanding and monitoring these profiles is critical to optimizing the therapeutic strategy based on the patient’s immune response.

| Immune Profile |

Key Cytokines |

Effect on Therapy |

| Th1 |

IFN-γ, IL-12 |

Drive a robust cytotoxic response, enhancing T-cell activation and tumor clearance. |

| Th2 |

IL-4, IL-10 |

May suppress cytotoxic responses, potentially compromising therapy efficacy. |

| Th17 |

IL-6, IL-17A |

Linked to pro-inflammatory responses, necessitating careful modulation to prevent excessive inflammation and associated side effects. |

Table 5.

Design of a validation and monitoring protocol for the efficacy of immunotherapy with pulsed DEXs, which must include controls at each stage of the process to ensure its correct evolution for each of the key stages.

Table 5.

Design of a validation and monitoring protocol for the efficacy of immunotherapy with pulsed DEXs, which must include controls at each stage of the process to ensure its correct evolution for each of the key stages.

| No. |

Stage |

Day |

Sample |

Exam |

Purpose |

| 1 |

Isolation of PBMCs |

Day 1 |

Peripheral blood |

Separation of PBMCs using the Ficoll density gradient technique. |

Isolate PBMCs with high viability and functionality to ensure suitability for subsequent differentiation and activation protocols. |

| 2 |

Cell viability and integrity test |

Day 1 |

Isolated PBMNCs |

Cell viability (Trypan blue or Annexin 5 assay) |

Assess viability (>95%) and integrity of PBMCs, ensuring optimal vitality and functional competence |

| 3 |

DC differentiation |

Day 7 |

PBMC culture |

Expression of HLA-DR, CD123, and CD11c via flow cytometry |

Confirm efficient differentiation into DCs through high expression of phenotypic markers |

| 4 |

DC maturation |

Day 10 |

Immature DCs |

Evaluation of maturation markers CD80, CD83, and CD86 via flow cytometry |

Verify the complete maturation of DCs, demonstrating the capacity for lymphocyte activation |

| 5 |

Obtaining and characterizing exosomes |

Day 12 |

DC secretome |

Concentration and size via NanoSight |

Quantify the concentration and characterize the size of exosomes (90–120 nm), ensuring uniformity and stability |

| 6 |

Immunopotency assessment |

Day 12 |

DC secretome |

Evaluation of the Th1, Th2, and Th17 cytokine profiles using ELISA and CBA |

Confirm the ability to produce proinflammatory cytokines capable of generating an effective immune response and respective lymphocyte activation (TNF-Q, IFN-y, IL-6, IL-17a, and IL-1b) |

| 7 |

Lymphocyte activation |

Day 14 |

Co-culture of exosomes and/or DCs with T lymphocytes |

Determination of lymphocyte activation (CD69 and CD25, via flow cytometry) |

Confirm the functional activation of T lymphocytes, evaluating their proliferative capacity, activation, and production of cytotoxic cytokines |

| 8 |

Induction of tumor apoptosis |

Day 14 |

Co-culture of activated T cells and tumor cells |

Apoptosis assay (LDH, caspase activation) |

Quantify the cytotoxic capacity of activated T lymphocytes to induce apoptosis in tumor cells, demonstrating the efficacy of the immunotherapeutic protocol |

| 9 |

Final product characterization |

Day 14 |

Enriched exosome concentrate |

Safety, viability, and membrane integrity tests, and immunological markers |

Confirm the quality and safety of the product before its clinical administration, complying with regulatory standards |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).