1. Introduction

Blockchain (BC) technology has transformed the way we think about centralized and decentralized secure systems. Blockchain ensures that once an event is recorded, it becomes a permanent and irreversible part of the systems’ history. This permanence can also be seen from the perspective of

information entropy [

1]: at the cost of running a Blockchain system, the information stored in it is “

frozen to eternity”. The

stability of dynamic systems has been analyzed by A.M. Lyapunov [

2]. We utilize this analysis to demonstrate that BC systems also operate around a

consensus equilibrium. In a malicious attempt to attack and destabilize a BC system, someone will have to confront the immense properties of

Secure Hashing: a vast amount of effort which by far exceeds every sensible scale, has to be paid [3-7].

To safeguard the minimum required level of consensus every time, all the prevailing Blockchain architectures utilize some form of data and functional redundancy [

8], often in the form of

State Machine Replication [

9]. This comes at a considerable cost for the nodes, leading back to centralization. Yet in general, the more the redundancy in a BC system, the more the fault and failure tolerance it delivers. In a more abstract social systems’ equivalence, the more the

common sense and the

shared values in a community, the more its

coherency [

10].

The resilience resulting from replication has a strong theoretical foundation as well: more redundancy results in lower overall system entropy, making it easier for the BC to serve its purpose as a zero-entropy reservoir.

In this work we investigate the Bolzman-Shannon entropy of a generic Blockchain consensus-enabling mechanism with respect to the degree of information redundancy in it. We demonstrate that consensus, being expressed as the complement of disagreement in a system, resembles a Lyapunov function: a positive definite function that decreases as the agent’s states converge.

Modeling Consensus

In nature, living organisms have inherited the ability to decode their sensorial inputs. An analogous inheritance property is infused in the autonomous artificial systems, for its atoms (i.e. the agents/nodes) to be able to reach consensus.

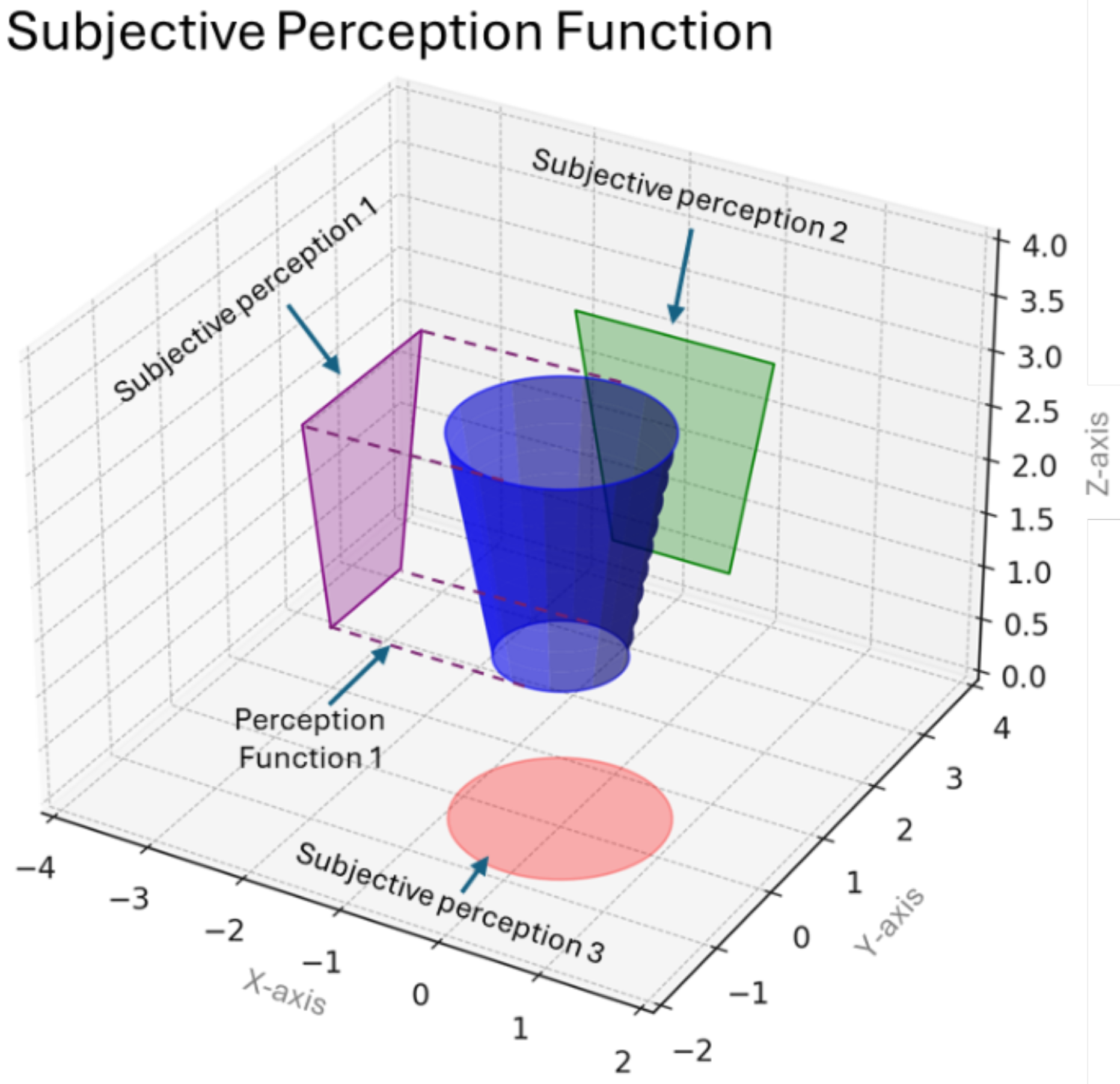

Setting a macroscopic example, a

cup should be a

cup irrespective of the atomic bias in the

perceptions (the personal viewpoints) of the observers (

Figure 1). This is a challenging requirement if we consider the limitations of the atoms and thus of the system as a whole. As has been extensively demonstrated in [

8],

subjectivity is inevitable in finite capacity systems.

In multi-agent systems, consensus relies on the Mutual Proof of a property e.g. Proof of Work, Proof of Stake, Proof of Capacity, Proof of Existence. This comes along with the requirement that the autonomous nodes have the individual capacity to prove, as well as to check the validity of the proof for themselves.

Consensus dynamics describes how a group of autonomous entities such as IoT devices, robots, sensors, drones, organisms coordinate their actions or inner states to reach an agreement.

In our exemplar, for the system to converge (i.e. for the observers to agree that what they see is actually the Cup), the outcome of their perception function(s) must be “close enough”: the likelihood that the Cup was the actual object in the initial input of the perception function needs to be above a certain threshold for all the consenters.

Due to its intrinsic complexity, consensus is susceptive to various definitions; from more tangible and deterministic ones (e.g. agreement on the outcome of a simple algebra function) to more abstract ones (e.g. agreement on the differences between the Democrats and the Republicans). In its more primitive forms, consensus often takes the form of catholic axioms i.e. 1+1=2.

If someone attempts to take consensus back to its primeval origins, he will without any doubt reach back to the Aristotelean definition of “true” or “existent” (the ancient Greek “ών”) [

11].

Reducing the subject of consensus to the extreme minima of a

“one-bit-something”, consensus is reduced to an agreement on “true” or “false”, “being” and “not being”. This constitutes perhaps the strongest form of consensus in human perception [

12]. Reducing the plurality of the system down to a

single-entity universe, consensus becomes semantically identical to inner consistency (i.e. agreement with the self) [

13].

At any rate, for the autonomous atoms/nodes/agents to be able to conclude on the consistency of their perceptions and to eventually reach consensus with each-other over an event, a set of internal validity rules has to operate within each one.

In this work we utilize the

IoT micro-Blockchain framework [

9] as a simple validity- enabling framework operating in each node. An overview of its basic points is quoted in section 2.

Our analysis on the BC systems’ consensus dynamics relies on three major pillars:

The adoption of the Boltzmann-Shannon equation on information entropy as the basic tool for our analysis

The modeling of consensus as a function of the number of nodes-witnesses consenting over an event (W)

The acknowledgement of the disagreement in a system as a discrete Lyapunov stability function with respect to the number of the event-witnesses in a system

We then investigate the effect of W in the stability and the entropy of the system. We prove that the entropy of the system decreases more sharply for small values of W (for few but >0 event-witnesses). We also demonstrate that the effect of W on the stability of the system remains linear over W.

2. Materials and Methods

Consensus and Stability

In our approach, we deal with the simplest form of consensus, i.e. consensus over bit-events. In this perspective, consensus-achievement in system takes the form of a majority “count of 1’s”. The nodes who agree on the bit-event coincide with the consistent witnesses of the event. While this is intuitively valid for bit-events like switching a lamp on/off, it actually holds for every perception function with binary output, irrespective of the dimensions of the input vector .

In this work we demonstrate that disagreement, being the complement of consensus in multi-agent autonomous systems, can be modeled as a Lyapunov function linked with the information entropy of the system: a positive definite function that decreases as the agents’ states converge.

In general, a Lyapunov stability function is a scalar function with the following properties:

at the equilibrium point x* (the desired degree of consensus reached, typically taken as the origin x=0, for simplicity).

for all , meaning is positive definite around the equilibrium point.

, meaning decreases or stays constant over time, ensuring that the system does not gain energy or move away from the equilibrium.

The contemplation behind the consideration of consensus in terms of Lyapunov stability is presented in section 3 Analysis & Results.

Perception and Consensus

Generalizing the Cup example, let an event object with k observable dimensions and , in be the perception functions of two distinct observers of the event. In the general case, perception is a function of reduction. being real numbers representing the observable attributes of the event (the magnitudes of the Event in every observable dimension), the and often produce their results in a lower-dimesion space .

From the collective point of view, the ends up being the aggregate of all the perceptions in the world, i.e. .

The Perception Convergence function over the event can consequently be defined as the distance of the two perceptions . To determine agreement, thresholds are defined. If , then the two perceptions converge; both observers 1 and 2 perceive as “the Cup”.

In its essence, consensus is a bit function that determines whether two observers agree or disagree upon the event : .

If for simplicity we try to reduce the data describing the event down to a single bit (e.g. the Event is the mere opening of a door), then and consensus upon is reduced to its most primitive semantic form (occurrence/not occurrence, existence/nonexistence of ).

At any rate, the

Collective Consensus of a realm of

N nodes over the event

E represents the number of the nodes that have observed (witnessed) the

Event and agree on it:

and the normalized Collective Consensus is the percentage of the nodes in the realm that consent on the

event E:

. (a)

In the world of Blockchain, reaching consensus over a new event

has an additive impact as well. As soon as a node agrees on the validity of the new

, he accepts as valid the whole sequence of the events in the chain since the beginning of the recordings

. At the cost of running the Blockchain, the overall normalized Collective Consensus becomes identical to the average percentage of the nodes that agree on each upcoming event

, aka the

Witnesses of

[

14].

For a Blockchain system to be stable, a minimum number of W consenting nodes has to be reached. In other words, we need (b) in the chain, setting the down-limit for since at least W per event witnesses is mandatory. This way equation (a) becomes .

The boundaries for

W are widely investigated under the Byzantine Fault Tolerance conceptual framework [

15]. If everyone is a witness of every new event, then consensus becomes absolute (

) and consequently

.

This holds especially true for the case of blockchain architectures that are built to facilitate monetary/ownership transfer transactions (like the Bitcoin Blockchain).

Modeling the Entropy of Collective Consensus

In our approach, we investigate the entropy differential from the simplistic perspective of the

free memory in the system. In our consideration, the memory of the nodes (and consequently of the system as a whole) is logically divided in two parts: the memory allocated to witness the events of

the others, and the

free memory remaining to store unique

own events. The more the free memory in the system, the more the Shannon entropy it bears (analyzed in detail in section 3). We treat witnessing as the mere cloning, transmission and storage of the data of an event on the local memory of

W siblings. To enable this, we utilize the properties of the

IoT micro-Blockchain framework defined in [

9], the main points of which we quote here.

The IoT Micro-Blockchain Framework

If someone tries to skim Blockchain to its absolute essentials, he will come down to a minimal functionality that every node has to be capable of carrying out of in order to be able to invoke in peer Blockchain operation with its siblings. The IoT micro-Blockchain is such a framework. It considers a peer network of minimal autonomous nodes capable of the essential BC functionality, namely, of peer communication and of essential information processing to facilitate hashing. Each node bears a limited amount of memory in order (a) to keep a small core of initial “inherited” programs (ROM-like part of reserved memory) and (b) to store the events data (RAM-like active memory).

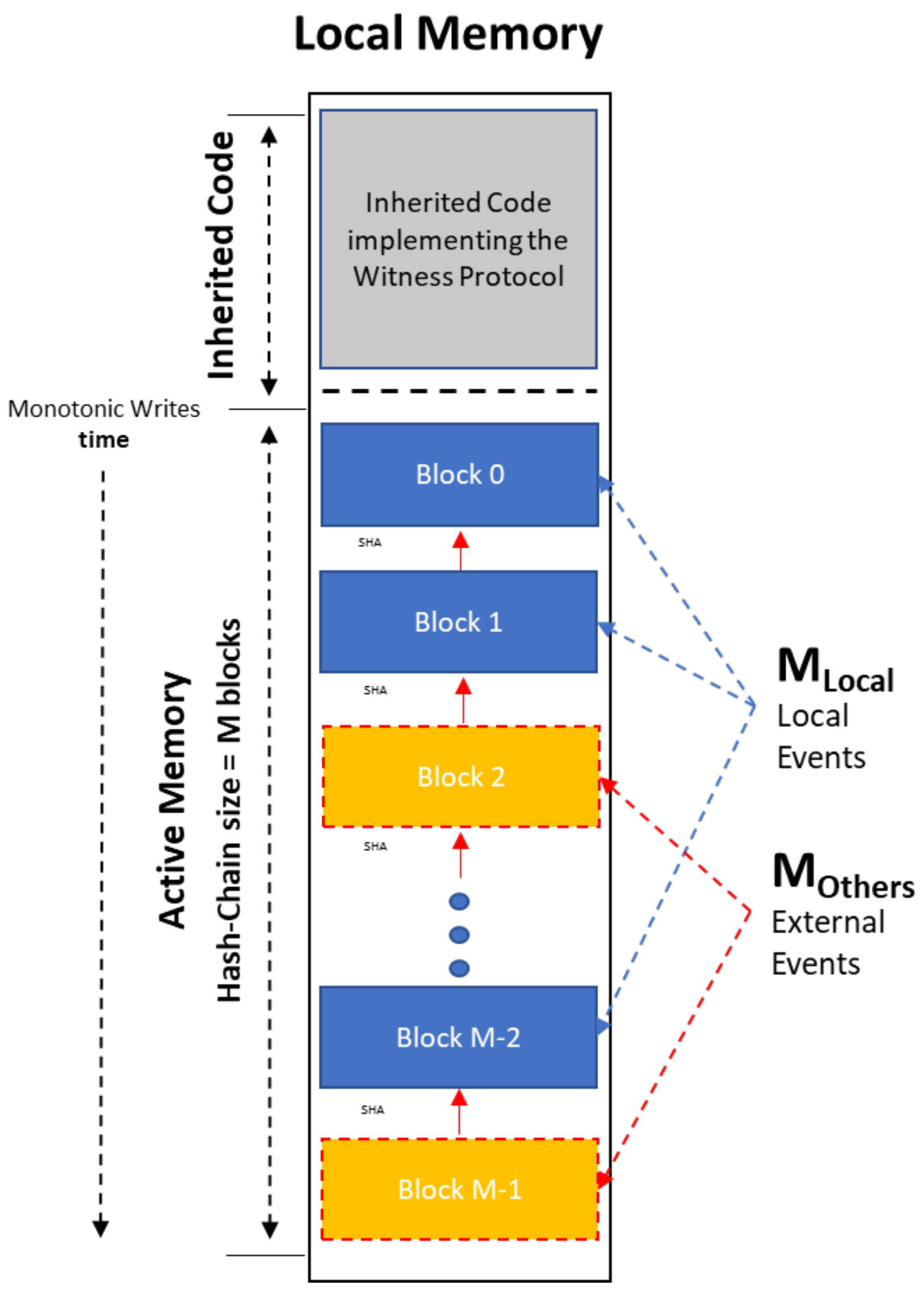

Thus, the

active memory of each node (

M) is further semantically divided in two parts: the

M_local that keeps the information of the events that take place inside the node, and the

M_others that keeps the information of the events that take place in others (

Figure 2).

Each node has a memory capacity of M blocks, each block storing the data of a single event. The events are stored in the memory of the node monotonically in time forming a local event hash-chain.

The active memory stores both local events as well as external events (events that took place on other nodes) on which the node is a witness, and thus we get:

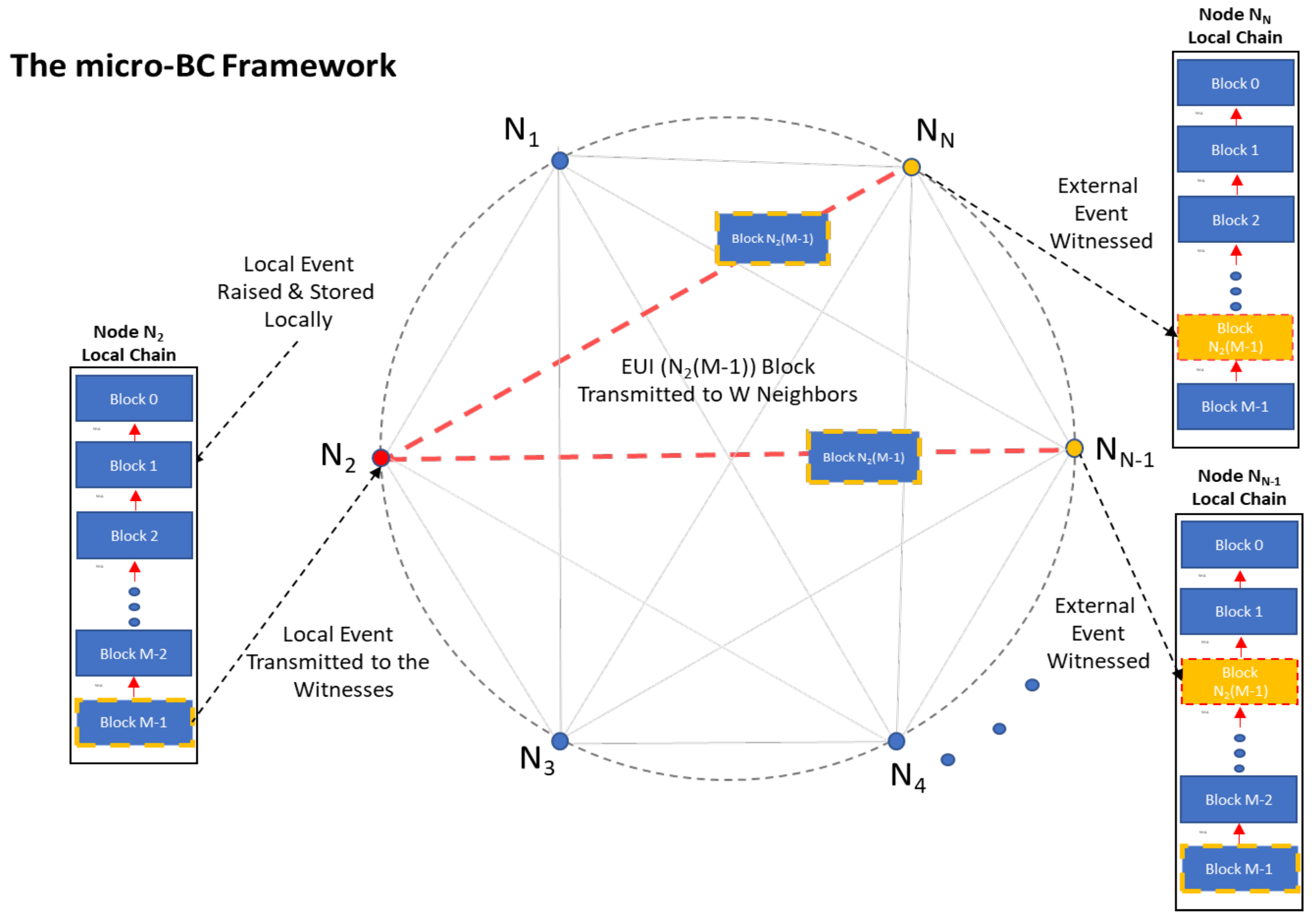

The system is self-contained. New events are taking place only within each of the

N nodes of the system. In the light of a new event,

W witnesses are being contacted to record it (

Figure 3).

The current work is built on proving a plain assumption: the more the witnessing in a system, the more the stability and the fault-tolerance it infuses. This comes along with the observation that the more the redundancy in a system, the more the cost that has been paid for it (the resources that have been invested) within the containing supersystem to establish and support the process. From the technical point of view, more memory cells and processing units are provided to the contained subsystem.

At the cost of running its consensus mechanism, the inner system tends to move towards a more stable and reduced-entropy state. This is getting more apparent while contemplating the causativeness and the finiteness of the digital systems. Since the digital systems are finite systems, the more the replication in them, the less the remaining free memory (memory to store unique events) and thus the information entropy of the system.

This simplistic observation, however, conceals the fact that redundancy itself comes at a significant thermal cost hidden in the production and maintenance of memory cells, in the computation/accumulation of the contents of the memory, etc. [

16].

3. Analysis and Results

Based on our previous considerations, we demonstrate the behavior of Information Entropy and Stability in distributed systems with respect to the event-witnesses W.

Stability and Consensus

Lyapunov Equilibria

Under the perspective of Consensus, every Blockchain system tends to be in a completely steady state, apart of course from the moment of the rise of a new to-be-added-to-the-chain event, and until this is successfully added. As soon as consensus is reached upon the new event(s), the system becomes finalized and steady over again. Every Blockchain is explicitly and specifically designed to serve this function. Seen under the Lyapunov stability perspective, a functional Blockchain will always move around this consensus equilibrium.

This said, in the general theoretical case of a totally peer, node-agnostic Blockchain system of N nodes, in order to reach consensus, NxN peer agreements have to be investigated upon every new event. In a totally peer and decentralized environment, everyone should match his perception against the perception of every other to conclude on convergence.

In the real world though, a way more efficient approach has been adopted. Every agent carries a pre-determined

vision of the Cup, a consistent personal representation of an

[

12]. He then matches his sensorial inputs against it to determine the degree resemblance. In autonomous systems,

everyone carries an inherited build-in validity framework.

To simplify and generalize our consideration, let be the perception of the observer i on the Cup, and the representation of the Ideal Cup in its memory. Macroscopically, the Ideal Cup may be defined as the median, the mean, or any other aggregate representation that minimizes perception differences (aka disagreements) among the observers. The incarnates a collective Lyapunov equilibrium over the Cup.

Irrespective of the details of the aggregation that defines the Ideal Cup, we can define a binary distance function with if is “close enough” to to be perceived as the Cup and consequently for observer i to become a Witness of the existence of the Cup, and if is not “close enough” to .

As stated before in section 2, for binary-outcome perception functions, consensus can be modeled as the mere count of Witnesses upon .

The number of the

Witnesses becomes:

We can then define a function representing the

degree of disagreement over the Cup, with respect to the normalized Collective Consensus over the event

E as:

In this perspective, is a scalar that satisfies all the properties of a Lyapunov function, since:

at the equilibrium (total consensus W=N),

when W<N (not all agree on the cup)

decreases monotonically as W increases, with rate:

The derivative is negative, highlighting that decreases increasing W. This aligns perfectly with the intuitive notion of system stability: the more the nodes that agree on the Cup are, the more the stability of the system becomes, and the corresponding Lyapunov function of disagreement moves closer to 0.

The rate of change is constant . This suggests that each additional witness has a fixed impact on reducing linearly, pushing the system closer to the consensus equilibrium. Since N is a positive natural number representing the number of autonomous nodes in the realm, always holds, ensuring that decreases monotonically with W. This negative rate of change reflects that the system moves towards increased stability as more nodes agree on the Cup, stressing the Lyapunov stability properties of .

Information Entropy and Consensus

Consensus among autonomous peer individuals is an inference process which relies on the mutual proof of some property, such as PoW, PoS, PoE, PoA. For this to take place, both functional and data redundancy is mandatory among the nodes: to conclude on the validity of the outcome, we need to share the initial data describing the event, as well as some processing principles.

This suggests that redundancy, which in the prevailing Blockchain systems is often realized in the form of pure state replication, is an essential integral part of the process of the consensus. As a macroscopic observation we may pose that “the more the information we share, the more the chances to reach to common perception on an event” – aka consensus.

Yet, in a finite capacity system, (and consequently in every digital system), this inevitably points to less free memory in the system and points directly to reduced overall system entropy.

Shannon Information Entropy

The general Shannon entropy formula for a discrete probability distribution is given by:

where

H the entropy of the system,

s the total number of possible states and

the probability of each state, where i=1,2,…,s [

1].

For combined binary events,

H goes

and is measured in bits:

In our model (i.e.

IoT micro-BC), the

unique events that are stored in the local memory of a node are given by

and consequently, the count of all the unique events in the system is

This corresponds to the total number of memory blocks that are assigned in our system to store unique events.

Without hurting generality, we can consider for simplicity that the stored events are binary (1 bit per event). Then, the whole of the unique events in the system can be represented as a bit-stream of bits.

To maximize the information capacity and to set the upper limit of the entropy of the system, we consider that every event combination has equal probability to occur.

Then, the total number of

unique events in our system is

bit-long and the probability

of any

unique event combination becomes:

Substituting

into Shannon’s Entropy Formula we get:

and since

is equal for every unique event, we get

Further substituting

in the entropy formula, we get

Which, further simplifies in:

This strengthens our initial assertion: the entropy drops proportionally to the increment of the witnessing in the system.

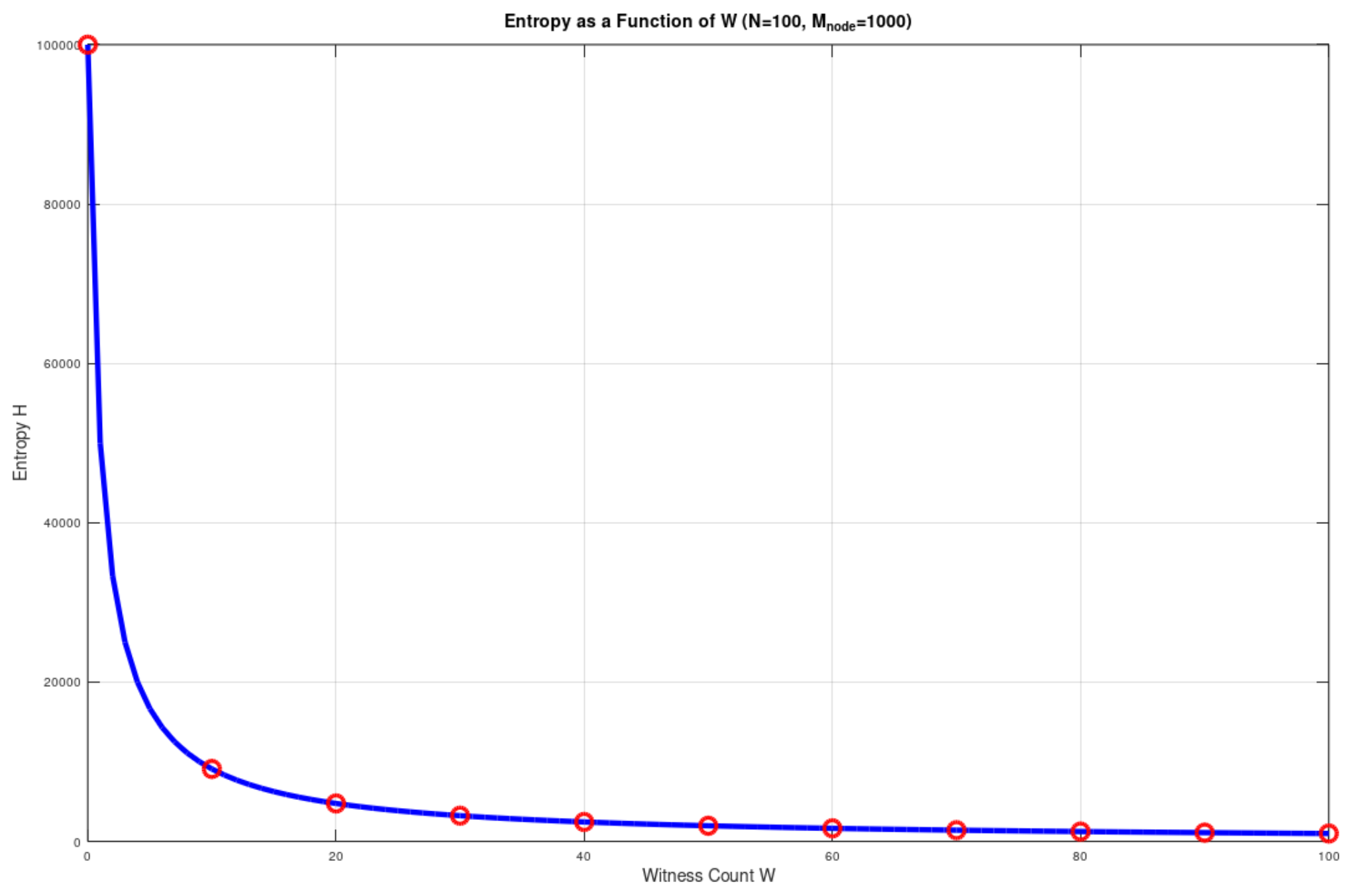

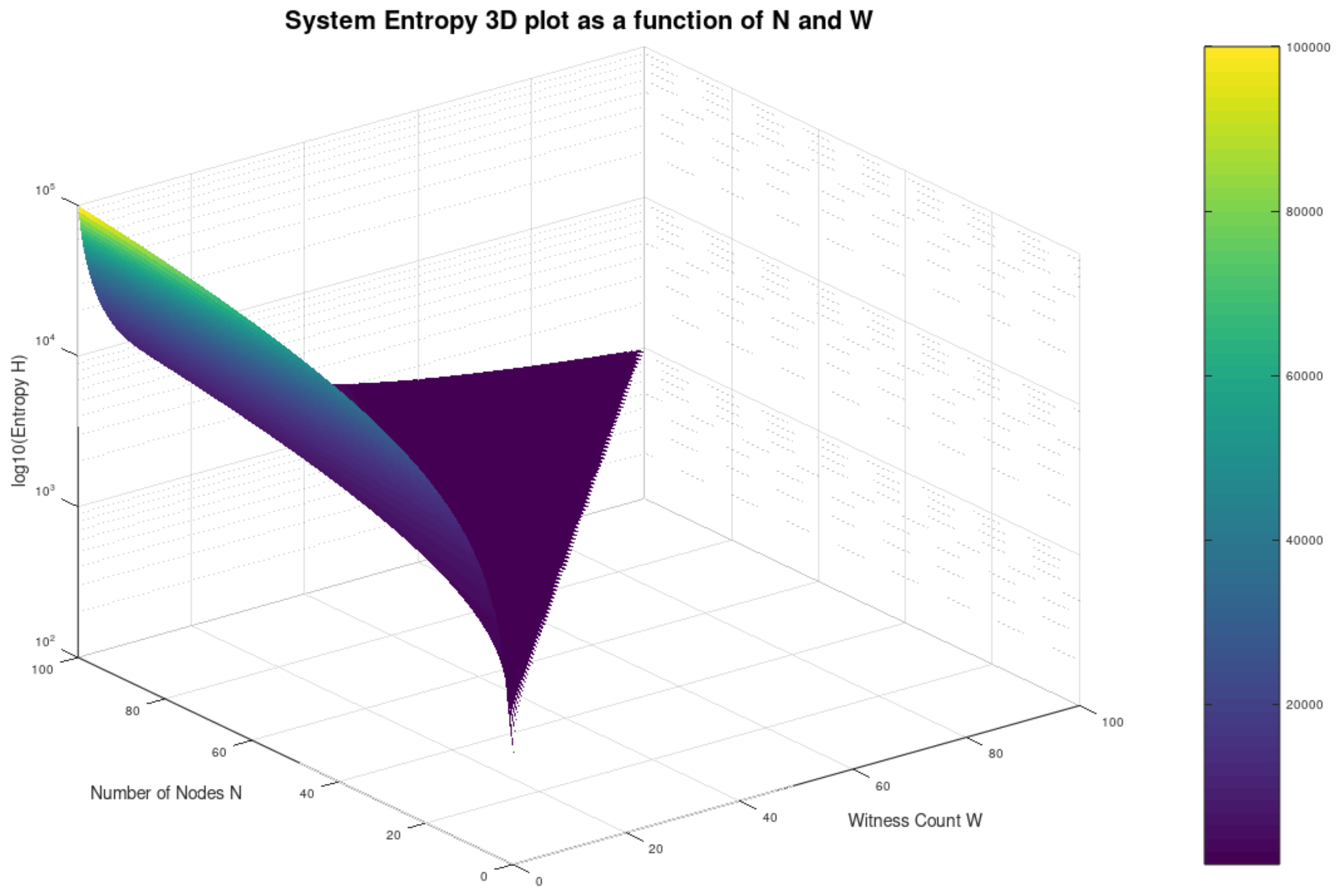

In

Figure 4 we see the effect of W on the overall Shannon entropy H in a static system of 100 nodes, while in

Figure 5 we see the impact of both W and N respectively, with N varying from 1 to 100 and W ranging from 0.1 to N-1 for Mnode =1000 bit every time.

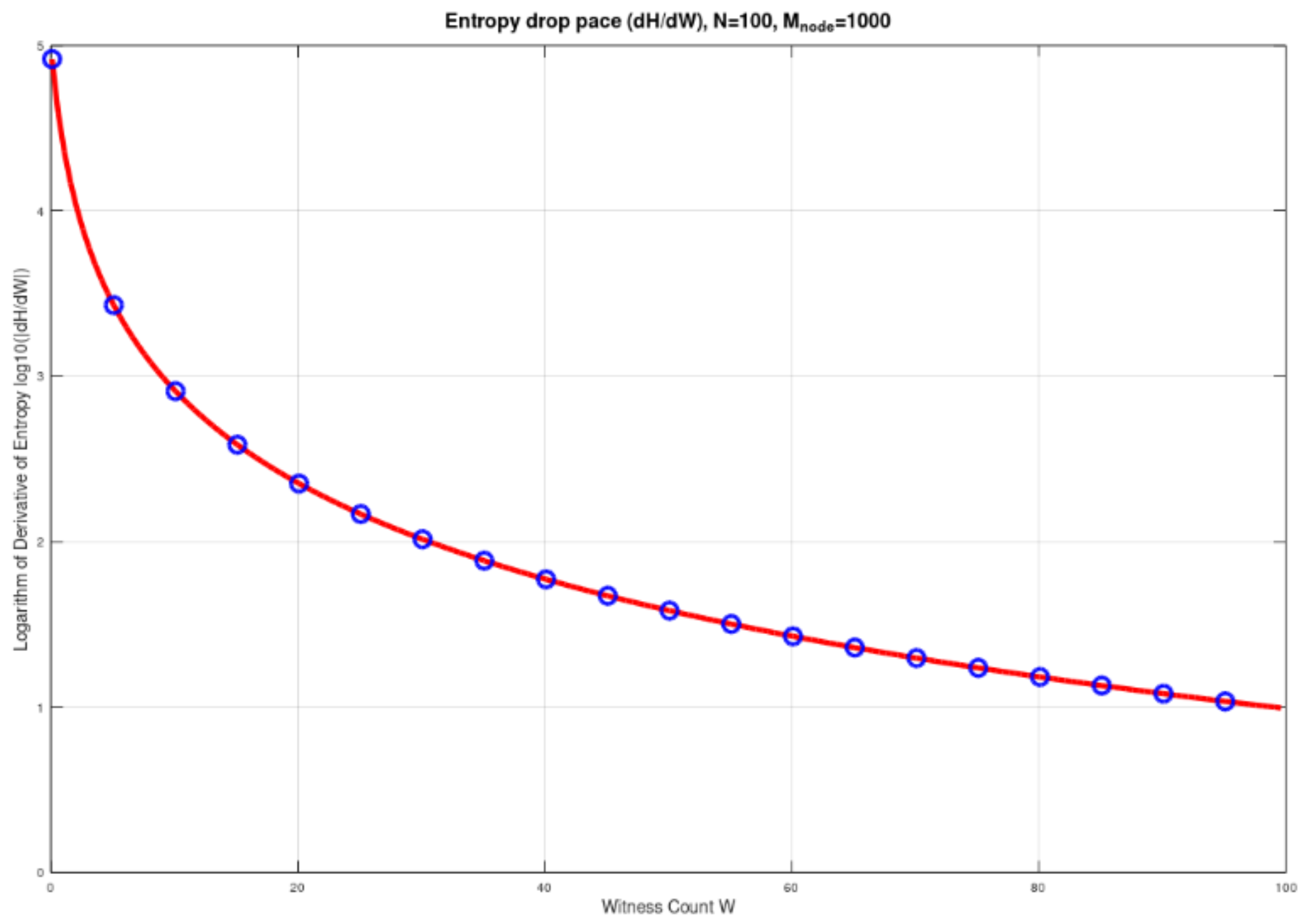

To determine the degree of the

entropy reduction with respect to W, we differentiate

H over W:

and since

, the derivative of H with respect to W becomes

This represents the rate at which the entropy drops increasing W.

Again, in

Figure 6 we see the effect of W in the pace of the entropy reduction in a static system of N nodes, while in

Figure 7 we see the impact of both W and N, with N varying from 1 to 100, W ranging from 0.1 to N-1 and Mnode =1000 bit.

We observe that the drop is steepest for low values of W. This highlights the fact that the effect of witnessing in the entropy of the system is higher for small values of W.

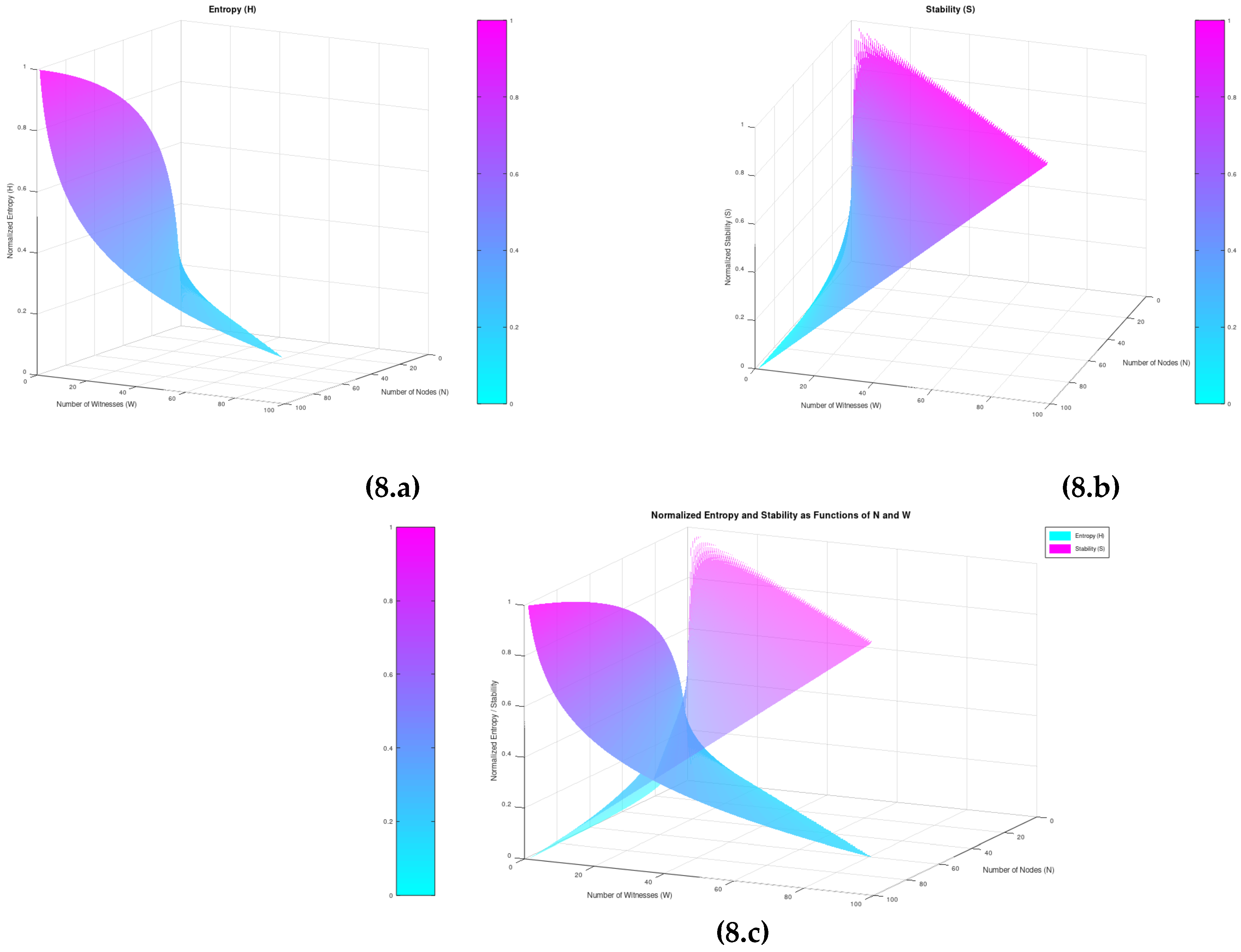

Figures 8(a,b,c) illustrate the meshes of the normalized entropy and stability with respect to N and W as well, to highlight the tradeoff between the information entropy and the stability of the system.

The optimization of W is in its essence, a quest for the steepest information entropy reduction path that guarantees the desired degree of stability every time and is subject to the needs of each specific application and architecture.

Measuring efficiency

While seeing Blockchain consensus mechanism as an entropy-conversion mechanism, its efficiency can be defined as the overall information entropy drop (bit) per consumed power (Watt). The actual absolute power consumption in the IoT micro-Blockchain model utilized in this work, as well as in any consensus-achievement architecture, is not constant over W. It is subject to a number of implementation-related factors such as the value of population count N, the computational efficiency of the nodes, the infinitesimal per memory cell power consumption, the minimum per-event witnessing processing required, the existence/absence of a broadcasting channel, and the conflicts relating to new events’ frequency and distribution among the nodes. These are subject to extensive analysis in other evolving works.

4. Discussion

Consensus achievement constitutes a major pillar of every Blockchain Architecture and information redundancy is an integral part of the consensus process.

Every

digital system is a

finite capacity system in which, as the

Information theory suggests, the less the

free memory, the less the

information entropy. In an attempt to reduce the overall entropy of digital systems, many mechanisms and policies have been devised, among which is the Blockchain. While the robustness and the resilience of the Blockchain are acclaimed for their application in the world of transactional systems and cryptocurrencies, its attributes can benefit every autonomous system [

17].

The impact of Replication on the Information Entropy of Blockchain-based systems

The prevailing Blockchain architectures greatly rely their universality and robustness on the

virtue of majority: in the light of a dispute, the

majority prevails. The process is facilitated through

information replication [

18]. The nodes in a Blockchain realm need to at least share a

common logic to tell

valid from

false (functional redundancy), as well as the data of the event(s) that they are meant to

prove or

verify (data replication). Absolute,

state machine replication is proclaimed and enforced in many prominent architectures [

18,

19,

26,

27].

However,

replication can be equivalently perceived as an effective way to

reduce the overall resources available in the system in order to process and store

unique events. The “free-memory”, or under the K. Fristones’ perspective the “free-energy” of the system decreases, and along with this, the

information entropy of the system decreases proportionally [

20,

21]. Yet, it is this exact entropy reduction that constitutes perhaps one of the most desired traits in every artificial system, and a profound reason behind the success of the Blockchain technology.

In a broader perspective

reduced entropy strongly relates to

life itself [

22]. Under the scope of the Second Law of Thermodynamics,

entropic efficiency seems to be a substantial feature of

existence: the degree of

entropy-reduction that can be achieved per

consumed power unit underlies in the definition of the

efficiency of every process, and the consensus-achievement mechanisms do not escape the trait. In this work we present a way to measure the information entropy reduction they bring to the system, and based on this, to point to a new universal way to measure their efficiency. Nature’s tendency to follow the steepest entropy ascendance paths, comes hand-in-hand with systems’ primary tendency towards adopting the steepest entropy reduction paths [

23].

Conceptually seen, Replication drives

Uniformity, which in turn plays a vital role in

nature and in

human society as well:

Biological replication infused in the atoms as chromosome inheritance, as well as

data replication infused through

learning and

education, establish a certain degree of “common sense” among the atoms [

24]. Down the line, it enables the atoms to act autonomously and with the need of fewer

witnesses (and

verifiers),

yet in consistency with each other. In an ideal world, every atom should be equipped with the means to act autonomously, while consensus would always be guaranteed [

25].

In this work we model replication as common events’ witnessing, and we prove that it has a significant, non-linear impact on the entropy reduction of the system: the less the existing witnesses in a system, the more the entropy decrement per additional witness becomes.

For simplicity we consider a constant average power consumption per event-witnessing. In practice though, the cost of witnessing is

exponentially increasing with W, due to

conflicts within and among the nodes that trigger increased retransmission and reprocessing requirements [

9].

We demonstrate, that in terms of entropy conversion, it is more efficient to keep the number of event-witnesses as low as possible in order to support the desired level of stability every time. In our quest for Blockchain optimization, this rational tradeoff reflects once again the necessity for scalability in the consensus process: we need to support the desired level of entropy and stability, at the lowest possible power cost. Under this perspective, the absolutistic requirement that every peer node gets to know and hold every single transaction in the network since the beginning of time, (i.e. at all times), which was posed during the infancy of the Blockchain architectures (such as the early stages of Bitcoin), is proved here to be the most inefficient in terms of information entropy reduction.

The impact of W on Stability

Having modeled replication as common event witnessing, we quantify the contribution of adding more witnesses to the stability of the system. We define a function representing the degree of disagreement over the exemplar event E (the recognition of a Cup), with respect to the normalized Collective Consensus over the event E and prove that it bears all the properties of a Lyapunov function. We also demonstrate that in contrast to its impact on the entropy, the impact of W on the stability of the system remains linear irrespective of its magnitude.

Functional redundancy vs Pure data replication

In many contemporary Blockchain architectures, the number of the witnesses tends to be reduced (W<<N), without compromising the robustness of the system [

26,

27]. The community realizes the benefits of scalability on the consensus achievement-process and strategy. The careful observer may pose and support the idea that the introduction of more

functional than

data redundancy in as system (as for example the utilization of more Merkle tree-like structures), introduces high robustness effects for significantly low(er) values of

W. Still, this is often misleading and concealing of important aspects:

The robustness of the system may take various forms, often exceeding the pure BFT consensus consideration (e.g. tolerance to physical disasters), imposing high values of W as a primeval functional mandate.

Such functionality-redundancy mechanisms, while seen under the prism of the second law of thermodynamics are significantly energy-consuming, and thus are expected to move the overall efficiency away from optimum.

The debate between functional redundancy and pure data replication holds strong. Which one is the most efficient? Irrespective of the nature of the redundancy, through this work we propose a metric of the efficiency of the consensus-enabling mechanism as the ratio of the phenomenal (observable) information entropy reduction to the overall energy consumed to achieve it. During this study we identified early signs of evidence that while pure data replication has a directly measurable impact in the information entropy of the contained system, the overall entropy impact of functional redundancy can be better integrally estimated at a higher level (i.e. in the containing super-system), as if executing an entropy-reduction piece of code, (such as a building a Merkle-like hash-tree), coincides with some form of derivative on the event data with respect to the external variable of time.

At any rate, in order to make more copies of the information in a system as well as to process information multiple times, more resources must be consumed to the containing supersystem for building and running more memory cells and for processing and sharing more data [

28]. With respect to the second law of thermodynamics, the overall entropy of the containing systems is expected to increase in every step in both cases.