Submitted:

14 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

One of the most emblematic theorems in the theory of distributed databases is the Eric Brewer’s CAP theorem. It stresses the tradeoffs between Consistency, Availability and Partition and states that it is impossible to guarantee all three of them simultaneously. Inspired by this, we introduce the new CAP theorem for autonomous consensus systems, and we demonstrate that of the three elementary properties, Consensus achievement (C), Autonomy (A) and entropic Performance (P), two at the most can be optimized at any given time. To formalize and analyze this tradeoff, we utilize the IoT micro-Blockchain as a universal, minimal, consensus-enabling framework. We define a set of quantitative functions relating each of the properties to the number of event-witnesses in the system. We identify the existing mutual exclusions, and we demonstrate that (A), (C), and (P) cannot be optimized simultaneously. This imposes an intrinsic limitation on the design and the optimization of distributed Blockchain consensus mechanisms.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Contribution

- -

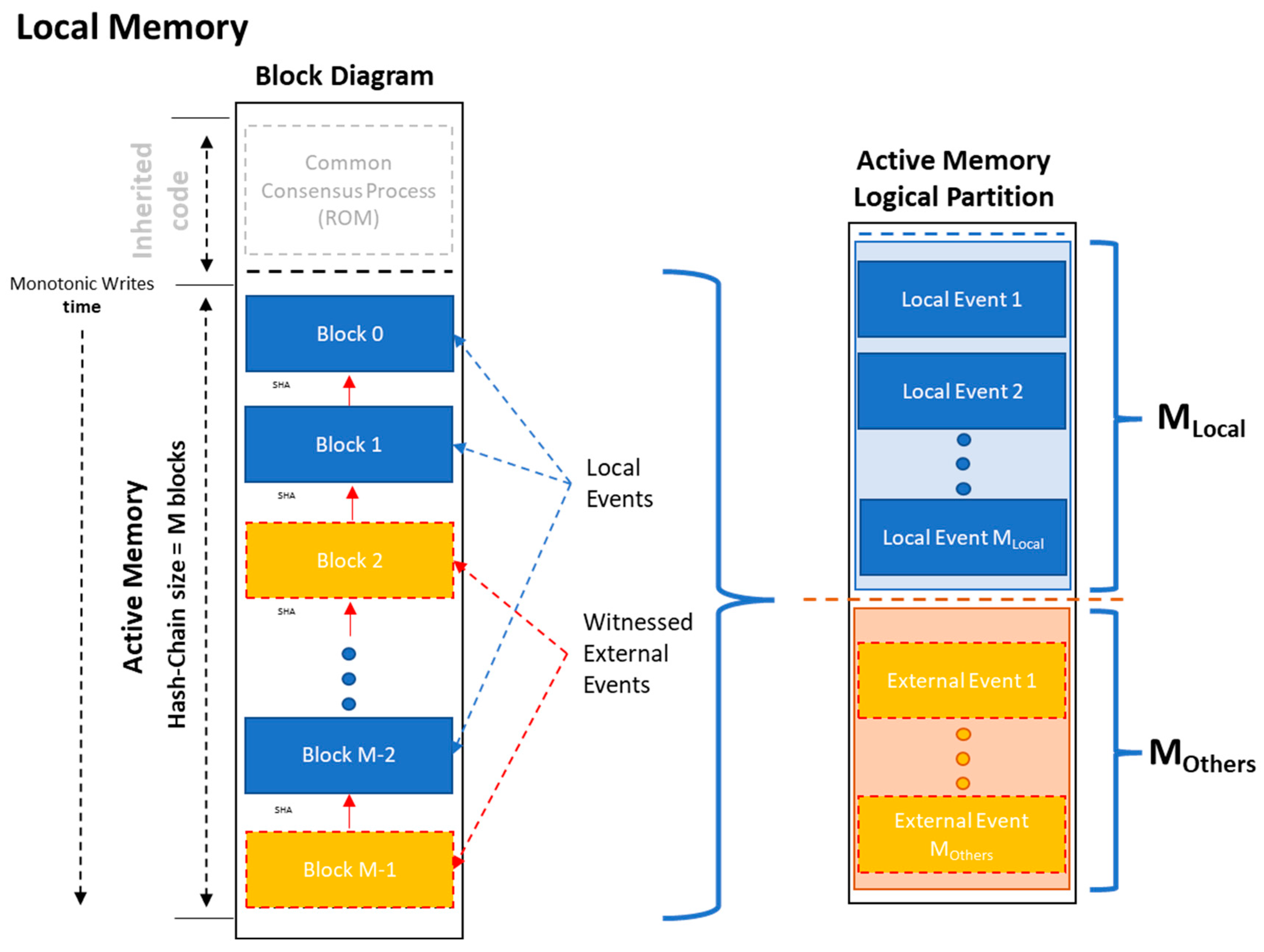

- Autonomy is defined at the atomic scale, as the fraction of the memory of each node reserved to serve local operations.

- -

- Consensus achievement is defined at the system scale as the fraction of nodes required to reach agreement (i.e., consent) on new events for the system to function.

- -

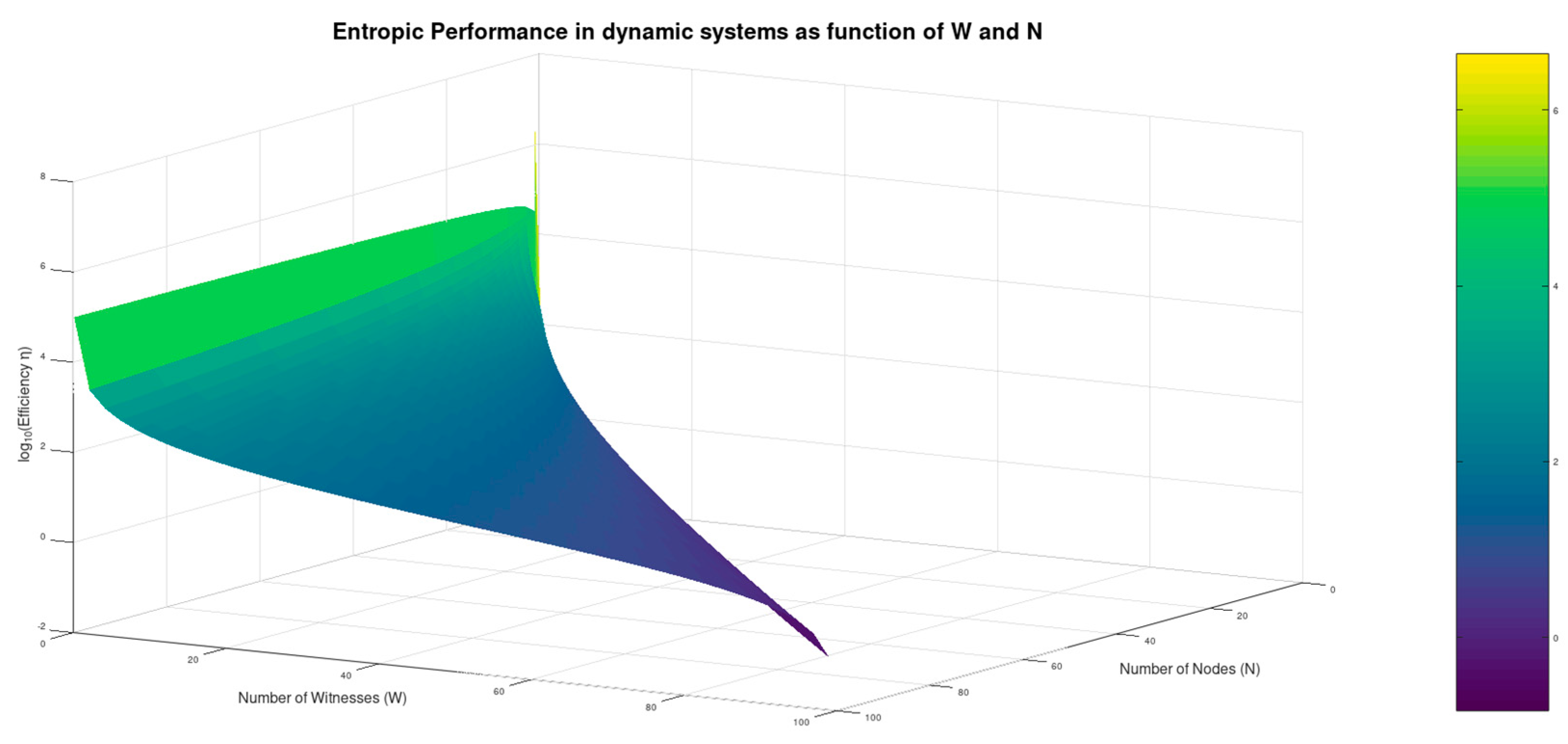

- Entropic Performance is introduced, following [14], as a metric for the efficiency of the consensus process quantified by the overall reduction in the information entropy of the system per unit of consumed energy.

- -

- We prove that of these three essential properties, two at the most can be optimized simultaneously at any given time.

- -

- We demonstrate that this trait comes in a direct analogy and has the same semantic origins as Eric Brewer’s CAP theorem.

2. Materials and Methods

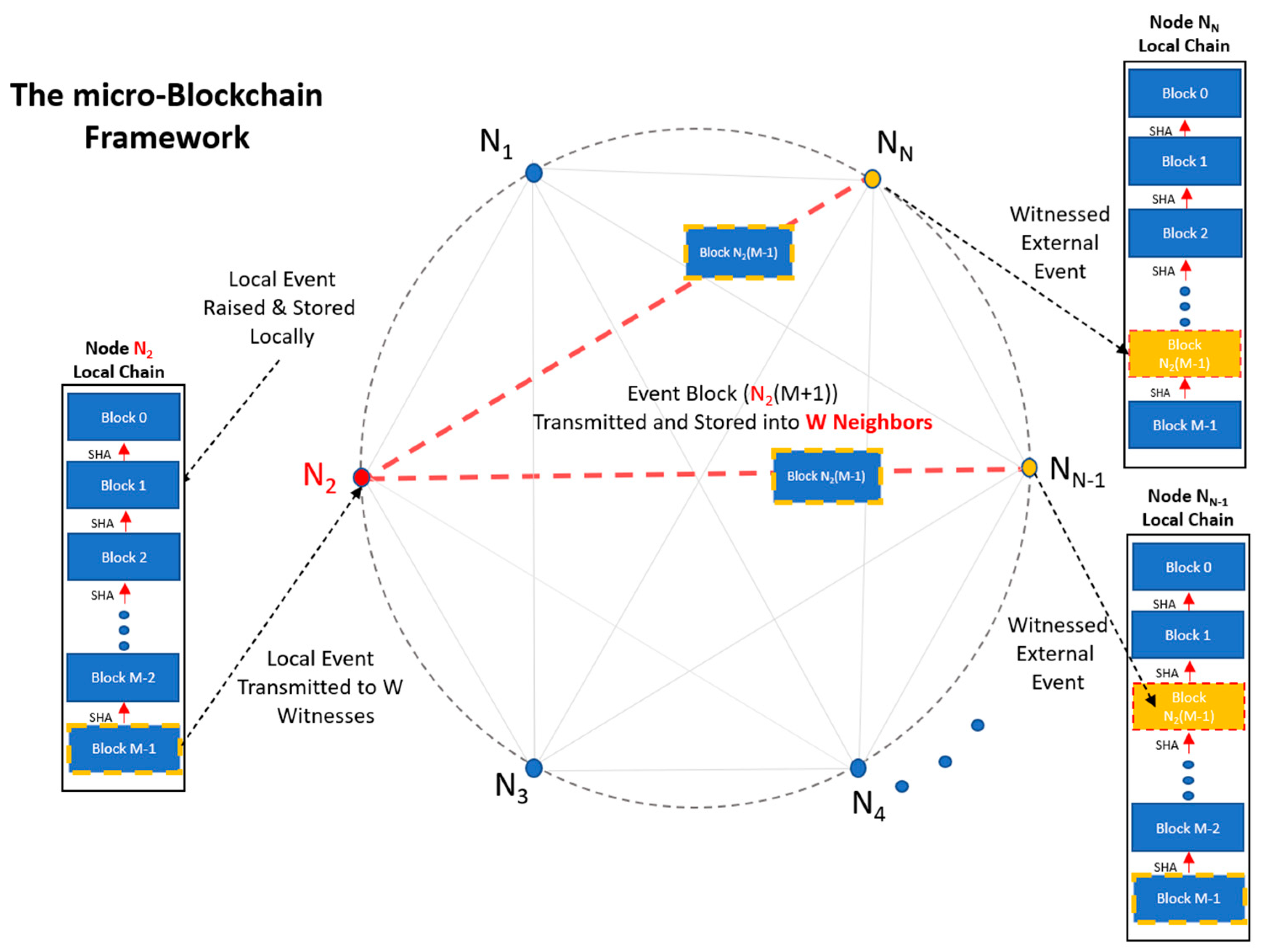

2.1. The IoT Micro-Blockchain Framework

2.2. Consensus, Autonomy and Entropic Performance

3. Analysis and Results

3.1. Formal Definitions

4. The New CAP Theorem

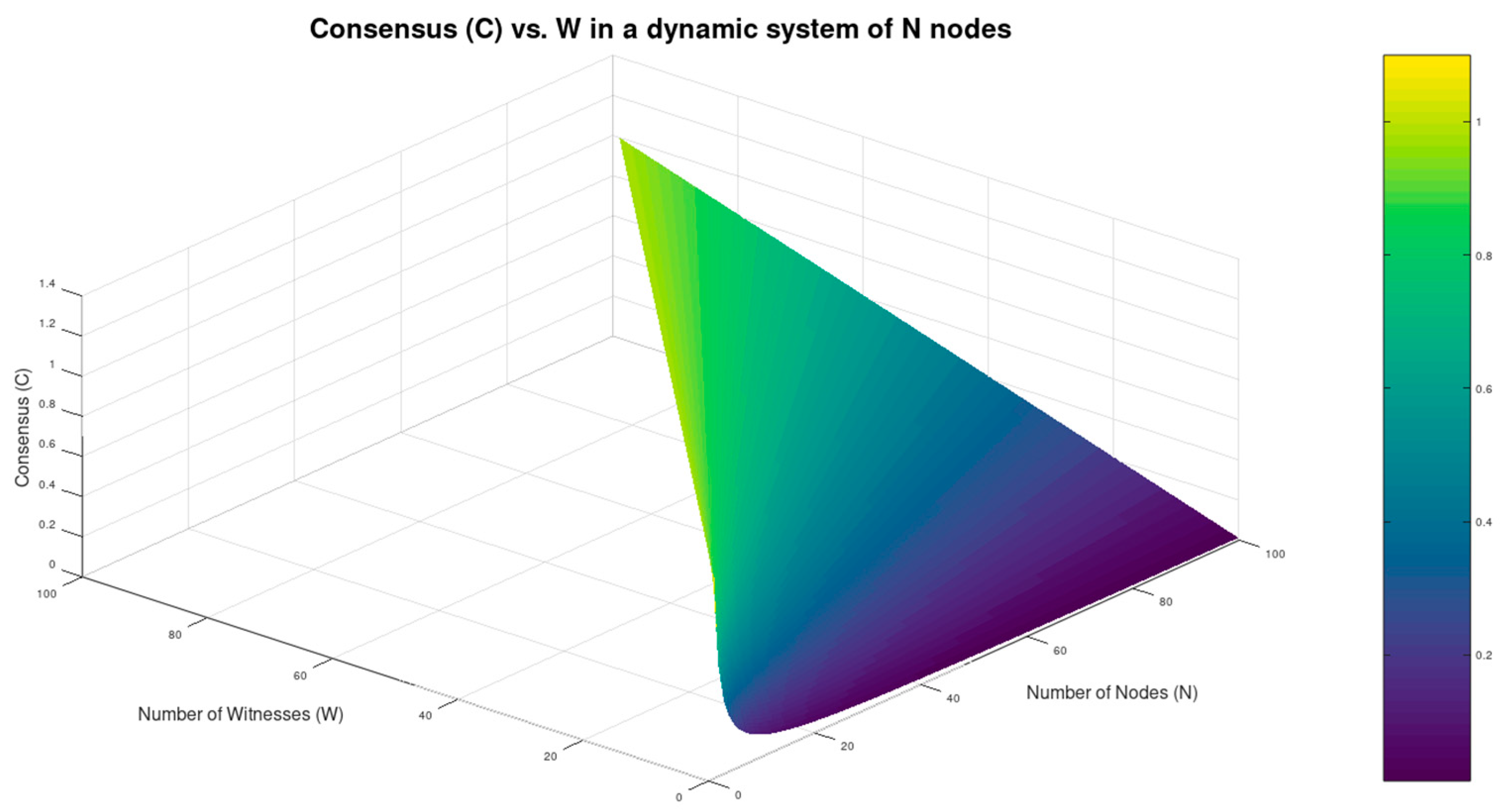

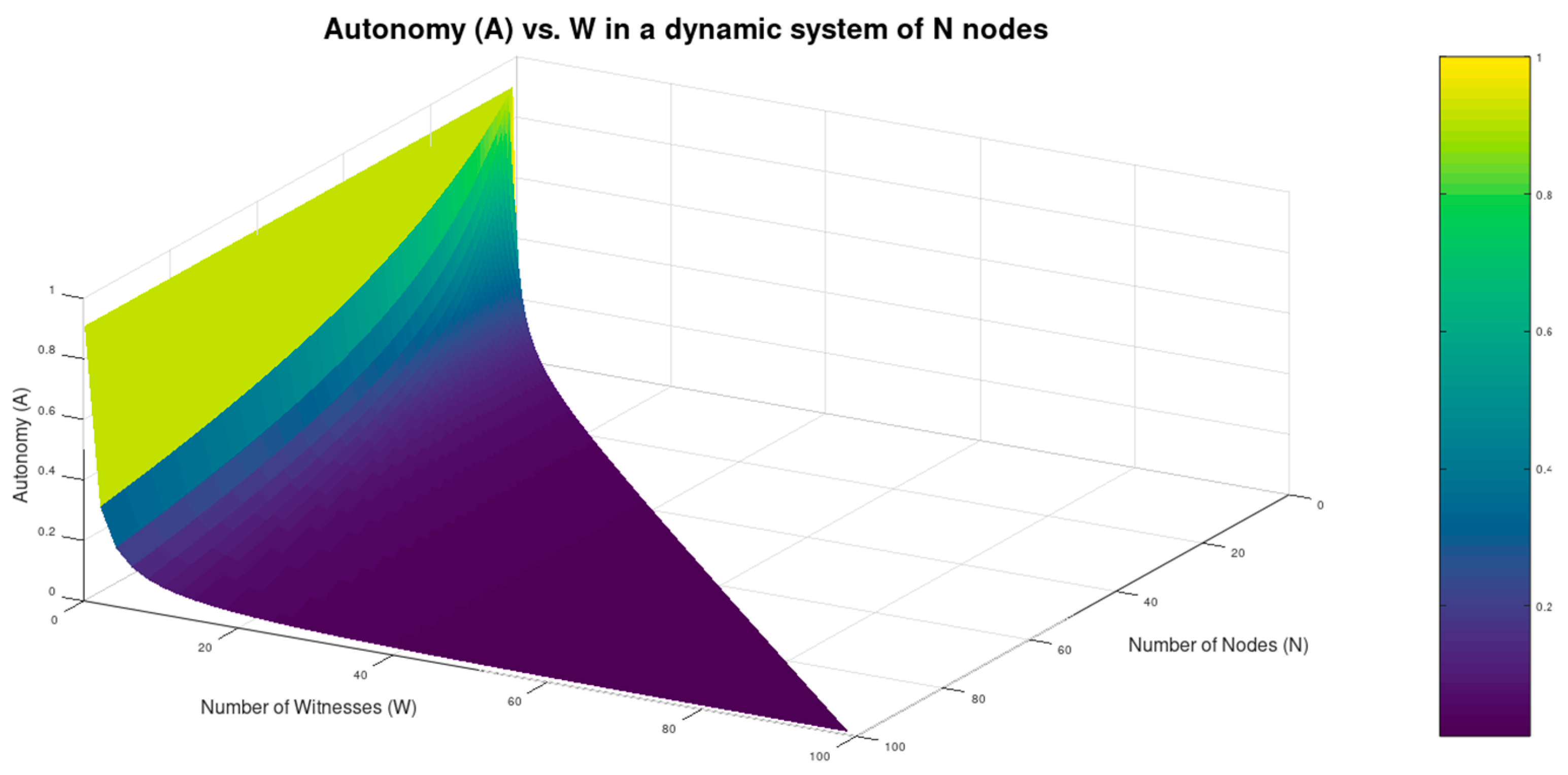

4.1. Autonomy and Consensus as Functions of W

4.2. Autonomy (A) vs Consensus (C)

4.3. Consensus (C) vs Entropic Performance (P)

4.4. Autonomy (A) vs Entropic Performance (P)

4.5. Entropic Performance (P) as a Function of W

5. Discussion

- (a)

-

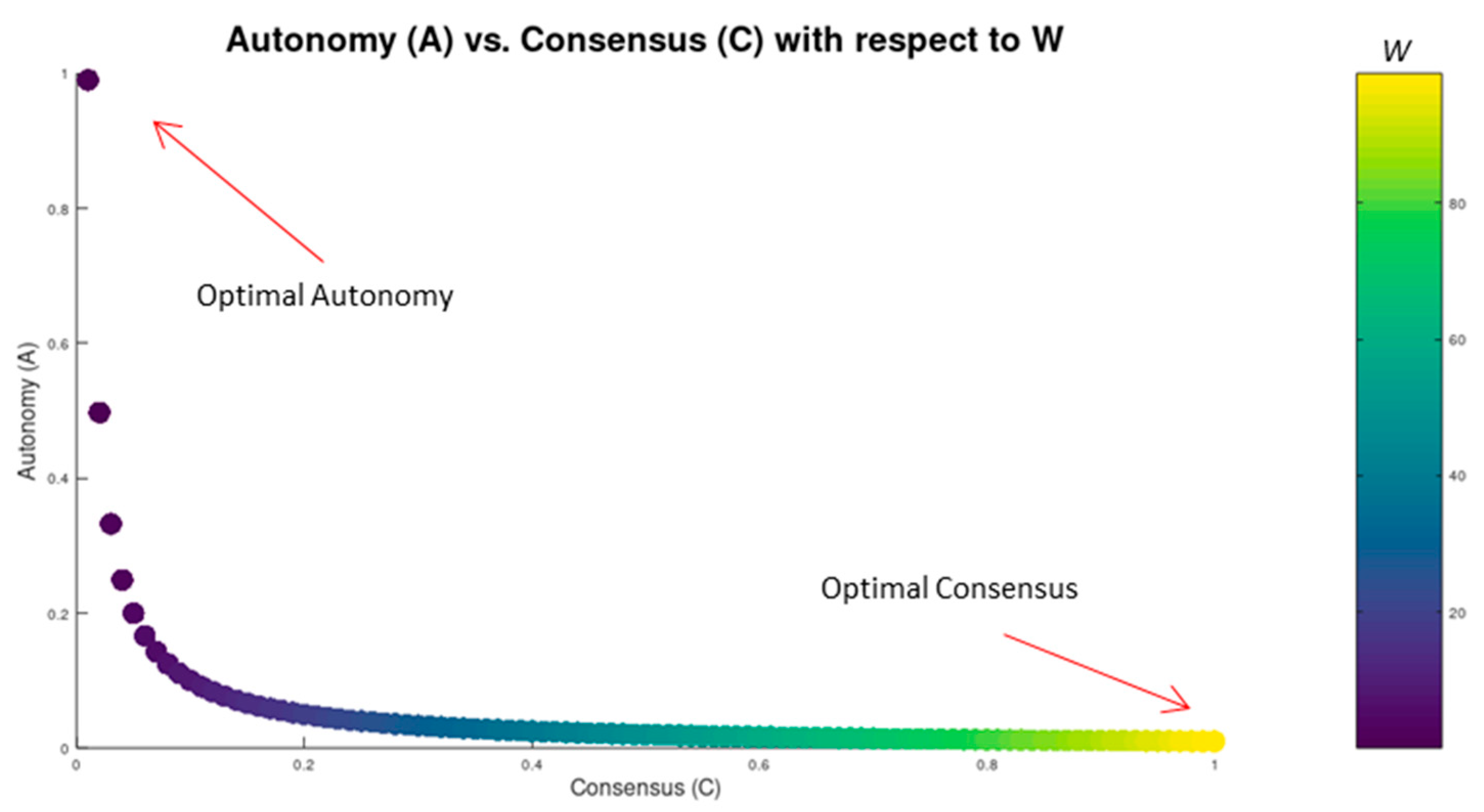

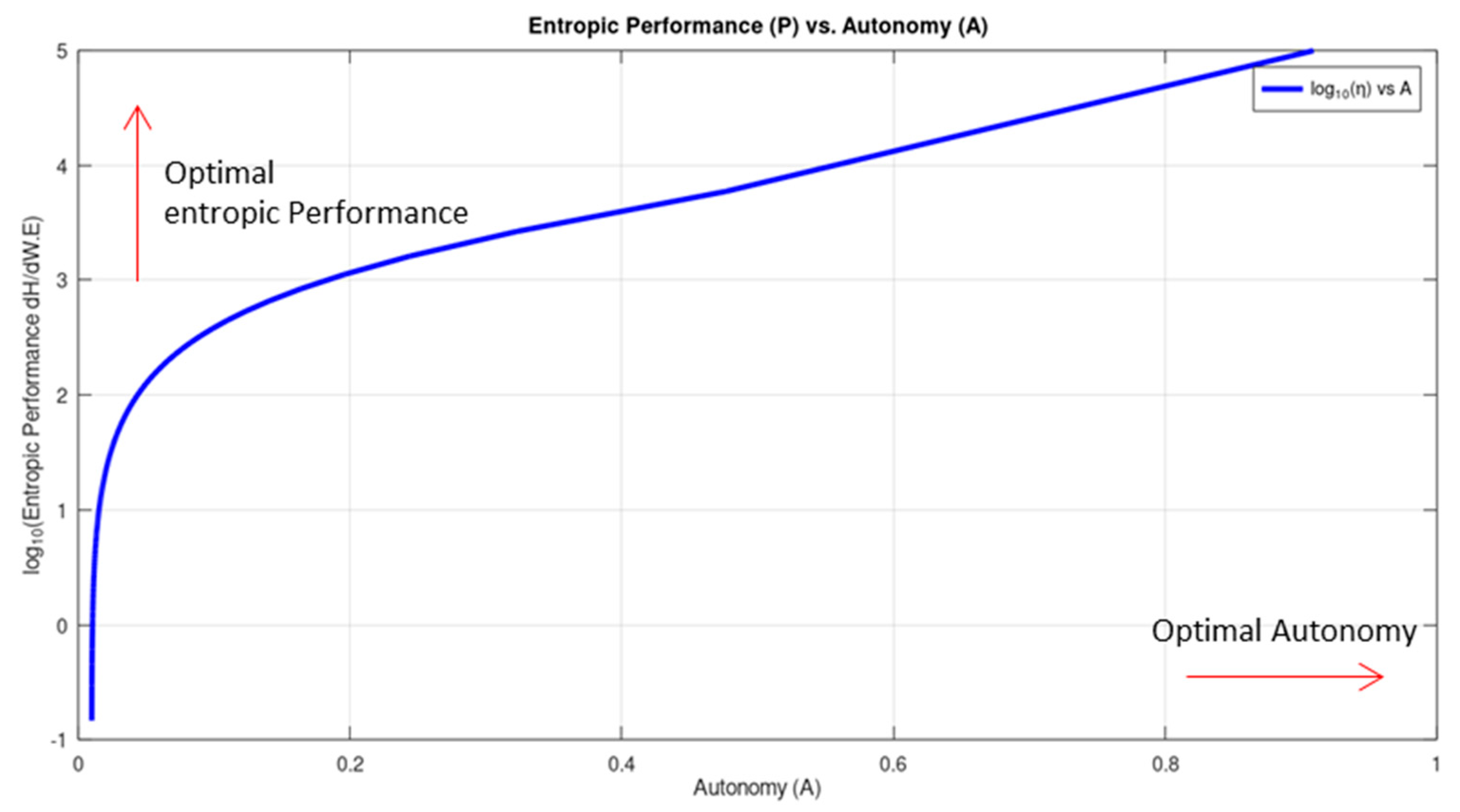

Between Autonomy (A) and Consensus achievement (C)In an attempt to optimize one of two, the other is sacrificed. This derives from eq.4, eq.5 and eq.6 in section 3.1 and is demonstrated in Figure 4, section 4.2. An attempt to optimize Autonomy (moving ) would leave the nodes without any resources to serve the community: W moves close to 0, leading Consensus achievement to minimum and the system degrades down to a set of isolated nodes. Again, trying to optimize Consensus (, we would have to withhold resources from the atoms to serve the system, sacrificing Autonomy.This intrinsic constraint was revealed in this work by starting from two apparently independent starting points: while we define Autonomy in the micro-scale of the atom, Consensus is defined in macro, with respect to the properties of the realm. This strengthens the hypothesis for the existence of an inherent constraint among A and C.

- (b)

-

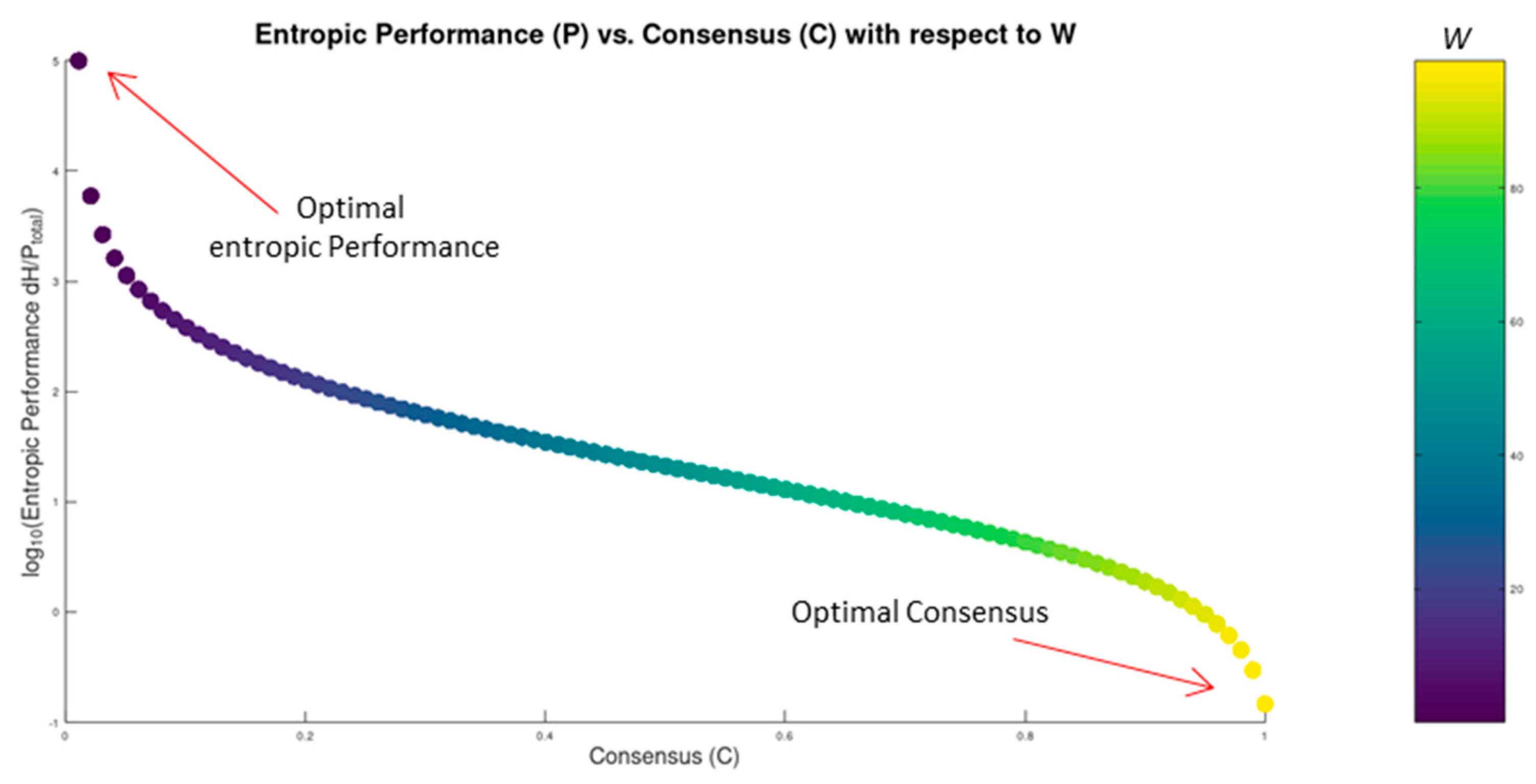

Between Consensus achievement (C) and entropic Performance (P)Consensus achievement is an energy-consuming process: it relies on data transmission, processing and storage, all of which are known to be energy consuming tasks. The constraint between (C) and (P) is revealed in section 3.1 through eq. 5 and eq. 9 and is demonstrated in Figure 5 section 4.3. Again, trying to optimize one of the two, the other is forced away from optimal. Our consideration for the two properties has independent starting points as well: while C is defined with respect to the macroscopic traits of the system, P is defined based on Shannon information entropy principles. This further strengthens the finding of the inherent constraint among C and P. The entropic traits of distributed consensus systems are studied extensively in [14].

5. Conclusions

References

- Aristoteles (284~322 B.C.) “Hθικά Νικομάχεια” Book 1, p. VII. Available online: https://www.greek-language.gr/digitalResources/ancient_greek/library/ browse.html?text_id=78&page=8 Last (accessed on 10/5/2024).

- Anagnostakis, A.G.; Naxakis, C.; Giannakeas, N.; Tsipouras, M.G.; Tzallas, A.T.; Glavas, E. Scalable Consensus over Finite Capacities in Multiagent IoT Ecosystems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 10, 6673–6688. [CrossRef]

- Dwork, C.; Lynch, N.; Stockmeyer, L. Consensus in the Presence of Partial Synchrony. J. ACM 1988, 35, 288–323.

- Alon, N.; Benjamini, I.; Lubetzky, E.; Sodin, S. Communication Cost of Consensus for Nodes with Limited Memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 1912980117. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, E.J.; Fonseca, E.S.; Mendonça, J.A.; Neto, J.B.; Pinto, A. Sustainable Consensus Algorithms Applied to Blockchain. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10552. [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Schülke, C.; Ehlers, M. Beyond Bitcoin: Evaluating Energy Consumption and Environmental Impact of Various Cryptocurrencies. Energies 2024, 16, 6610. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Sun, X. Concerning Consensus Fairness and Efficiency with Uncertain Costs. Mathematics 2023, 12, 1266. [CrossRef]

- Anagnostakis, A.G.; Giannakeas, N.; Tsipouras, M.G.; Glavas, E.; Tzallas, A.T. IoT Micro-Blockchain Fundamentals. Sensors 2021, 21, 2784. [CrossRef]

- Vogels, W. Eventually Consistent. Commun. ACM 2009, 52, 40–44. [CrossRef]

- Brewer, E.A. Towards Robust Distributed Systems. Proceedings of the Annual ACM Symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing (PODC), Portland, OR, USA, 16–19 July 2000. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/343477.343502.

- Gilbert, S.; Lynch, N. Brewer's Conjecture and the Feasibility of Consistent, Available, Partition-Tolerant Web Services. ACM SIGACT News 2002, 33, 51–59. [CrossRef]

- Rožman, N.; Corn, M.; Škulj, G.; Berlec, T.; Diaci, J.; Podržaj, P. Exploring the Effects of Blockchain Scalability Limitations on Performance and User Behavior in Blockchain-Based Shared Manufacturing Systems: An Experimental Approach. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4251. [CrossRef]

- Bulgakov, A.L.; Aleshina, A.V.; Smirnov, S.D.; Demidov, A.D.; Milyutin, M.A.; Xin, Y. Scalability and Security in Blockchain Networks: Evaluation of Sharding Algorithms and Prospects for Decentralized Data Storage. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3860. [CrossRef]

- Anagnostakis, A.G.; Glavas, E. Entropy and Stability in Blockchain Consensus Dynamics. Information 2025, 16, 138. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, C.; Wang, X.; Yang, F. A Witness-Based Consensus Algorithm for Private Blockchains. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 38874–38883. [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. Bitcoin.org. 2008. Available online: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf (accessed on 15/5/2024).

- Buterin, V. A Next-Generation Smart Contract and Decentralized Application Platform. Available online: https://blockchainlab.com/pdf/Ethereum_white_paper-a_next_generation_smart_contract_and_decentralized_application_platform-vitalik-buterin.pdf (accessed on 10/1/2025).

- Hyperledger Fabric Documentation. Available online: https://hyperledger-fabric.readthedocs.io/ (accessed on 10/1/2025).

- Arduino. Arduino ABX00027 Datasheet. Available online: https://docs.arduino.cc/resources/datasheets/ABX00027-datasheet.pdf (accessed on 1/2/2025).

- Noether, E. Invariante Variationsprobleme. Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse 1918, 235–257. Available online: https://eudml.org/doc/59024 (accessed on 14/2/2025).

- Noether, E. Invariant Variation Problems. Translated by M.A. Tavel. Transp. Theory Stat. Phys. 1971, 1, 186–207. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/physics/0503066.pdf (accessed on 14/2/2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).