Submitted:

05 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

How Much Evidence Is Enough?

Means, Motive and Opportunity

Two Lines of Easily Misconstrued Evidence Dominate the Field

“Specifically, in utero (but not postnatal) exposure to paracetamol results in a 19% increased risk of ASD (Masarwa et al., 2018, Alemany et al., 2021, Khan et al., 2022)…”

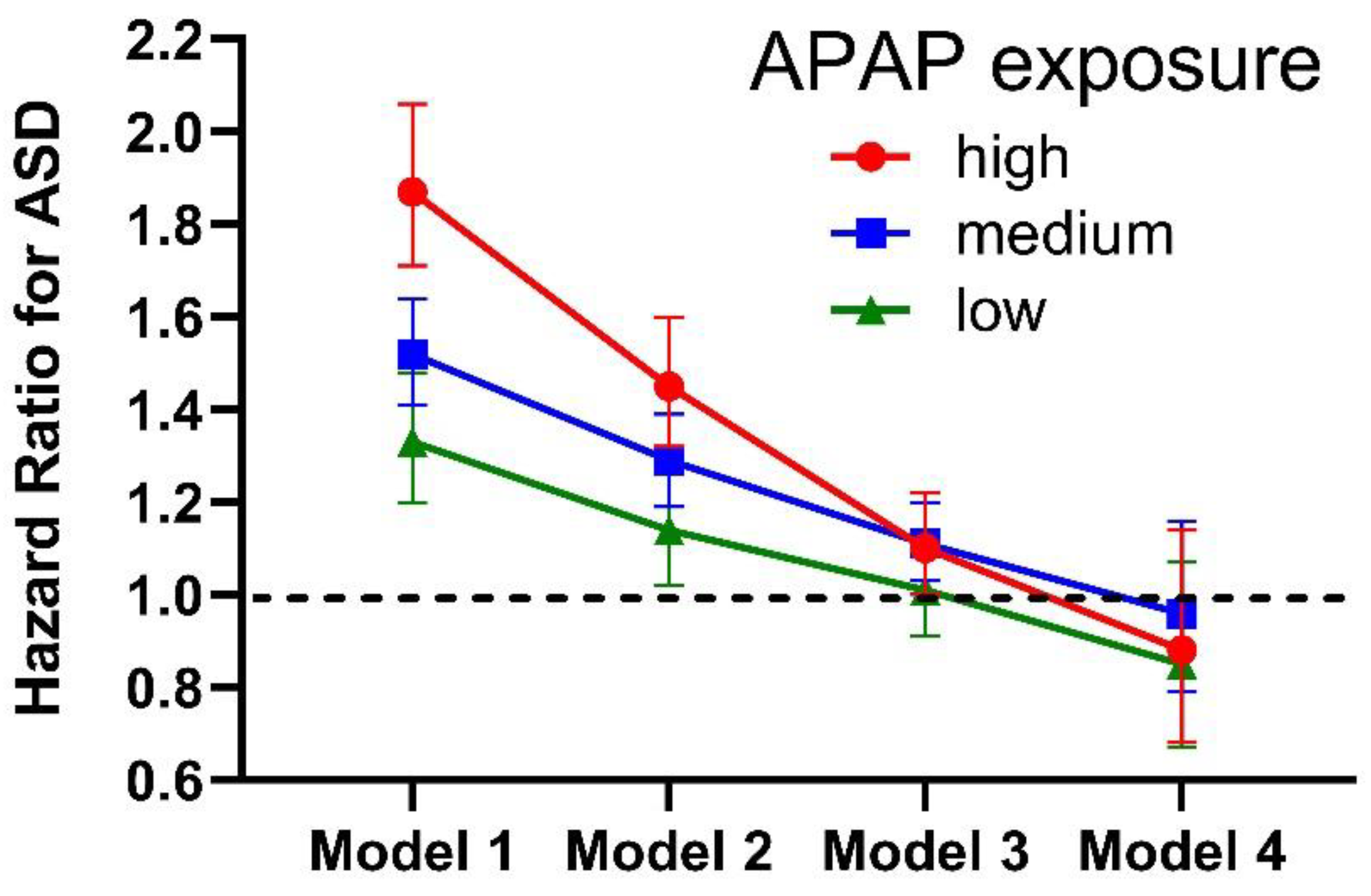

“It is concluded that risks of acetaminophen use for neurodevelopment obtained from multivariate analysis of cohort data depend on underlying assumptions in the analyses, and that other evidence, both abundant and robust, demonstrate the critical role of acetaminophen in the etiology of ASD.”

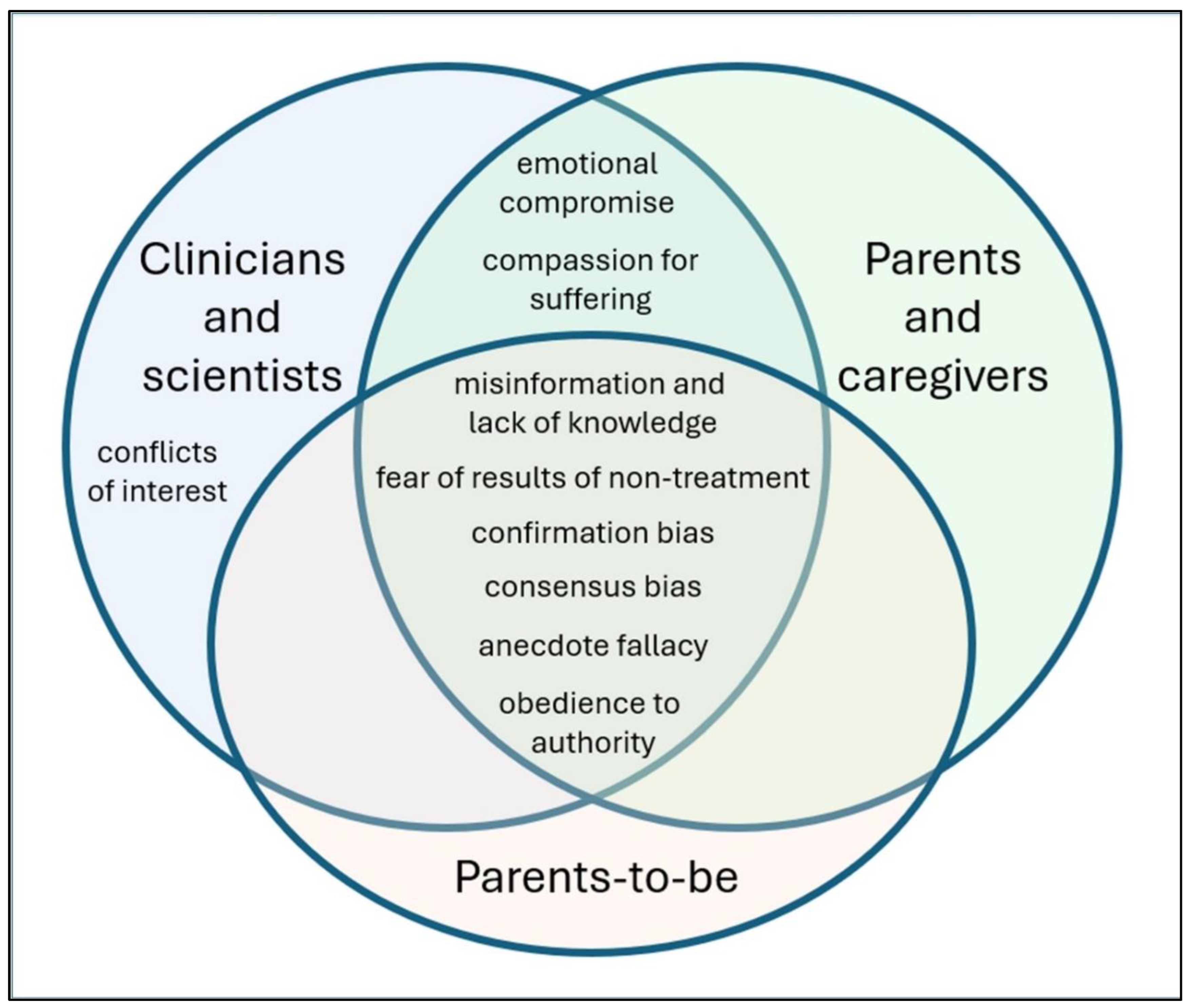

Barriers to Moving Forward

Clinical Implications

Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Zhao L, Jones J, Anderson L, Konsoula Z, Nevison C, Reissner K, et al. Acetaminophen causes neurodevelopmental injury in susceptible babies and children: no valid rationale for controversy. Clinical and experimental pediatrics. 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel E, Jones Iii JP, 3rd, Bono-Lunn D, Kuchibhatla M, Palkar A, Cendejas Hernandez J, et al. The safety of pediatric use of paracetamol (acetaminophen): a narrative review of direct and indirect evidence. Minerva pediatrics. 2022, 74, 774–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker W, Anderson LG, Jones JP, Anderson R, Williamson L, Bono-Lunn D, et al. The Dangers of Acetaminophen for Neurodevelopment Outweigh Scant Evidence for Long-Term Benefits. Children. 2024, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones JP, 3rd, Williamson L, Konsoula Z, Anderson R, Reissner KJ, Parker W. Evaluating the Role of Susceptibility Inducing Cofactors and of Acetaminophen in the Etiology of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Life (Basel, Switzerland). 2024, 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graeca M, Kulesza R. Impaired brainstem auditory evoked potentials after in utero exposure to high dose paracetamol exposure. Hear Res. 2024, 454, 109149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinz B, Cheremina O, Brune K. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor in man. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogestatt ED, Jonsson BA, Ermund A, Andersson DA, Bjork H, Alexander JP, et al. Conversion of acetaminophen to the bioactive N-acylphenolamine AM404 via fatty acid amide hydrolase-dependent arachidonic acid conjugation in the nervous system. J Biol Chem. 2005, 280, 31405–31412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirai T, Umeda N, Harada T, Okumura A, Nakayasu C, Ohto-Nakanishi T, et al. Arachidonic acid-derived dihydroxy fatty acids in neonatal cord blood relate symptoms of autism spectrum disorders and social adaptive functioning: Hamamatsu Birth Cohort for Mothers and Children (HBC Study). Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2024, 78, 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schultz ST, Klonoff-Cohen HS, Wingard DL, Akshoomoff NA, Macera CA, Ji M. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) use, measles-mumps-rubella vaccination, and autistic disorder. The results of a parent survey. Autism. 2008, 12, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cendejas-Hernandez J, Sarafian J, Lawton V, Palkar A, Anderson L, Lariviere V, et al. Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) Use in Infants and Children was Never Shown to be Safe for Neurodevelopment: A Systematic Review with Citation Tracking. . Eur J Pediatr. 2022, 181, 1835–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertmann RK, Møller JJ, Waldorff FB, Siersma V, Reventlow S, Söderström M. The majority of sick children receive paracetamol during the winter. Danish medical journal. 2012, 59, A4555. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bornehag CG, Reichenberg A, Hallerback MU, Wikstrom S, Koch HM, Jonsson BA, et al. Prenatal exposure to acetaminophen and children's language development at 30 months. Eur Psychiatry. 2018, 51, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker W, Hornik CD, Bilbo S, Holzknecht ZE, Gentry L, Rao R, et al. The role of oxidative stress, inflammation and acetaminophen exposure from birth to early childhood in the induction of autism. J Int Med Res. 2017, 45, 407–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji Y, Azuine RE, Zhang Y, Hou W, Hong X, Wang G, et al. Association of Cord Plasma Biomarkers of In Utero Acetaminophen Exposure With Risk of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder in Childhood. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020, 77, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Baker BH, Lugo-Candelas C, Wu H, Laue HE, Boivin A, Gillet V, et al. Association of Prenatal Acetaminophen Exposure Measured in Meconium With Risk of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Mediated by Frontoparietal Network Brain Connectivity. JAMA pediatrics. 2020, 174, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ahlqvist VH, Sjöqvist H, Dalman C, Karlsson H, Stephansson O, Johansson S, et al. Acetaminophen Use During Pregnancy and Children's Risk of Autism, ADHD, and Intellectual Disability. Jama. 2024, 331, 1205–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lexchin J, Bero LA, Djulbegovic B, Clark O. Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review. BMJ. 2003, 326, 1167–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lundh A, Lexchin J, Mintzes B, Schroll JB, Bero L. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017, 2, Mr000033 Epub 2017/02/17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bero L, Oostvogel F, Bacchetti P, Lee K. Factors associated with findings of published trials of drug-drug comparisons: why some statins appear more efficacious than others. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bero, LA. Tobacco industry manipulation of research. Public health reports (Washington, DC : 1974). 2005, 120, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fabbri A, Holland TJ, Bero LA. Food industry sponsorship of academic research: investigating commercial bias in the research agenda. Public health nutrition. 2018, 21, 3422–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Whitstock, M. Manufacturing the truth: From designing clinical trials to publishing trial data. Indian journal of medical ethics. 2018, 3, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta R, Chernesky J, Lembke A, Michaels D, Tomori C, Greene JA, et al. The opioid industry's use of scientific evidence to advance claims about prescription opioid safety and effectiveness. Health affairs scholar. 2024, 2, qxae119 Epub 2024/10/25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Legg T, Hatchard J, Gilmore AB. The Science for Profit Model-How and why corporations influence science and the use of science in policy and practice. PLoS One. 2021, 16, e0253272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tovo-Rodrigues L, Schneider BC, Martins-Silva T, Del-Ponte B, Loret de Mola C, Schuler-Faccini L, et al. Is intrauterine exposure to acetaminophen associated with emotional and hyperactivity problems during childhood? Findings from the 2004 Pelotas birth cohort. BMC Psychiatry. 2018, 18, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlenterie R, Wood ME, Brandlistuen RE, Roeleveld N, van Gelder MM, Nordeng H. Neurodevelopmental problems at 18 months among children exposed to paracetamol in utero: a propensity score matched cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 1998–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liew Z, Ritz B, Virk J, Arah OA, Olsen J. Prenatal Use of Acetaminophen and Child IQ: A Danish Cohort Study. Epidemiology. 2016, 27, 912–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liew Z, Bach CC, Asarnow RF, Ritz B, Olsen J. Paracetamol use during pregnancy and attention and executive function in offspring at age 5 years. Int J Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 2009–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avella-Garcia CB, Julvez J, Fortuny J, Rebordosa C, Garcia-Esteban R, Galan IR, et al. Acetaminophen use in pregnancy and neurodevelopment: attention function and autism spectrum symptoms. Int J Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 1987–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemany S, Avella-García C, Liew Z, García-Esteban R, Inoue K, Cadman T, et al. Prenatal and postnatal exposure to acetaminophen in relation to autism spectrum and attention-deficit and hyperactivity symptoms in childhood: Meta-analysis in six European population-based cohorts. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021, 36, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skovlund E, Handal M, Selmer R, Brandlistuen RE, Skurtveit S. Language competence and communication skills in 3-year-old children after prenatal exposure to analgesic opioids. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017, 26, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liew Z, Ritz B, Rebordosa C, Lee PC, Olsen J. Acetaminophen use during pregnancy, behavioral problems, and hyperkinetic disorders. JAMA pediatrics. 2014, 168, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liew Z, Ritz B, Virk J, Olsen J. Maternal use of acetaminophen during pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorders in childhood: A Danish national birth cohort study. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research. 2016, 9, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ystrom E, Gustavson K, Brandlistuen RE, Knudsen GP, Magnus P, Susser E, et al. Prenatal Exposure to Acetaminophen and Risk of ADHD. Pediatrics. 2017. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson JM, Waldie KE, Wall CR, Murphy R, Mitchell EA. Associations between acetaminophen use during pregnancy and ADHD symptoms measured at ages 7 and 11 years. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e108210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stergiakouli E, Thapar A, Davey Smith G. Association of Acetaminophen Use During Pregnancy With Behavioral Problems in Childhood: Evidence Against Confounding. JAMA pediatrics. 2016, 170, 964–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brandlistuen RE, Ystrom E, Nulman I, Koren G, Nordeng H. Prenatal paracetamol exposure and child neurodevelopment: a sibling-controlled cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2013, 42, 1702–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Masarwa R, Levine H, Gorelik E, Reif S, Perlman A, Matok I. Prenatal Exposure to Acetaminophen and Risk for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Autistic Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression Analysis of Cohort Studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2018, 187, 1817–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan FY, Kabiraj G, Ahmed MA, Adam M, Mannuru SP, Ramesh V, et al. A Systematic Review of the Link Between Autism Spectrum Disorder and Acetaminophen: A Mystery to Resolve. Cureus. 2022, 14, e26995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viberg H, Eriksson P, Gordh T, Fredriksson A. Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) Administration During Neonatal Brain Development Affects Cognitive Function and Alters Its Analgesic and Anxiolytic Response in Adult Male Mice. Toxicol Sci. 2013, 138, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch M, Simonsen J. Ritual circumcision and risk of autism spectrum disorder in 0- to 9-year-old boys: national cohort study in Denmark. J R Soc Med. 2015, 108, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bauer A, Kriebel D. Prenatal and perinatal analgesic exposure and autism: an ecological link. Environmental Health. 2013, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris BJ, Krieger JN, Klausner JD. CDC's Male Circumcision Recommendations Represent a Key Public Health Measure. Global health, science and practice. 2017, 5, 15–27. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sneppen I, Thorup J. Foreskin Morbidity in Uncircumcised Males. Pediatrics. 2016; 137. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumack BH. Aspirin versus acetaminophen: a comparative view. Pediatrics. 1978, 62(5 Pt 2 Suppl):943-6. [PubMed]

- Chen L, Zhang M, Yung J, Chen J, McNair C, Lee KS. Safety of Rectal Administration of Acetaminophen in Neonates. The Canadian journal of hospital pharmacy. 2018, 71, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Anderson BJ, van Lingen RA, Hansen TG, Lin YC, Holford NH. Acetaminophen developmental pharmacokinetics in premature neonates and infants: a pooled population analysis. Anesthesiology. 2002, 96, 1336–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birmingham PK, Tobin MJ, Fisher DM, Henthorn TK, Hall SC, Coté CJ. Initial and subsequent dosing of rectal acetaminophen in children: a 24-hour pharmacokinetic study of new dose recommendations. Anesthesiology. 2001, 94, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery CJ, McCormack JP, Reichert CC, Marsland CP. Plasma concentrations after high-dose (45 mg.kg-1) rectal acetaminophen in children. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d'anesthesie. 1995, 42, 982–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulthard KP, Nielson HW, Schroder M, Covino A, Matthews NT, Murray RS, et al. Relative bioavailability and plasma paracetamol profiles of Panadol suppositories in children. J Paediatr Child Health. 1998, 34, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paracetamol use with Bexsero New Zealand: Immunisation Advisory Centre; 2018 [updated 2023, cited 2024 December 21]. Available from: https://www.immune.org.nz/factsheets/paracetamol-use-with-bexsero-r.

- Meningococcal disease. In: Care HaA, editor.: Australian Government; 2024.

- Using paracetamol to prevent and treat fever after MenB vaccination. In: Agency UHS, editor. UK: National Health Service; 2022.

- Meningococcal vaccines: Canadian Immunization Guide. In: Canada PHAo, editor.: Government of Canada; 2024.

- Vaccines for Children Israel: Ministry of Health; 2021 [cited 2024 21 December]. Available from: https://www.gov.il/en/pages/vaccines-for-children-pamphlet.

- Significant events in meningococcal vaccination practice in Australia Australia: National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance; 2020 [cited 2024 21 December]. Available from: https://www.ncirs.org.au/sites/default/files/2020-07/Meningococcal-history-July%202020.pdf.

- Autism in Australia, 2022.: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2024. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/autism-australia-2022.

- Dinstein I, Solomon S, Zats M, Shusel R, Lottner R, Gershon BB, et al. Large increase in ASD prevalence in Israel between 2017 and 2021. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research. 2024, 17, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Ryan ML, Saxena S, Baum F. Time for a revolution in academic medicine? BMJ. 2024, 387, q2508. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti A, Pirrone P, Elia M, Waring RH, Romano C. Sulphation deficit in "low-functioning" autistic children: a pilot study. Biol Psychiatry. 1999, 46, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geier DA, Kern JK, Garver CR, Adams JB, Audhya T, Geier MR. A prospective study of transsulfuration biomarkers in autistic disorders. Neurochem Res. 2009, 34, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagan C, Benabou M, Leblond C, Cliquet F, Mathieu A, Lemière N, et al. Decreased phenol sulfotransferase activities associated with hyperserotonemia in autism spectrum disorders. Translational Psychiatry. 2021, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzezinski MR, Boutelet-Bochan H, Person RE, Fantel AG, Juchau MR. Catalytic activity and quantitation of cytochrome P-450 2E1 in prenatal human brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999, 289, 1648–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos JX, Rasga C, Marques AR, Martiniano H, Asif M, Vilela J, et al. A Role for Gene-Environment Interactions in Autism Spectrum Disorder Is Supported by Variants in Genes Regulating the Effects of Exposure to Xenobiotics. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2022, 16, 862315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Braam W, Keijzer H, Struijker Boudier H, Didden R, Smits M, Curfs L. CYP1A2 polymorphisms in slow melatonin metabolisers: a possible relationship with autism spectrum disorder? J Intellect Disabil Res. 2013, 57, 993–1000. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita M, Stempel KS, Borges do Nascimento IJ, Bruschettini M. Systemic opioids versus other analgesics and sedatives for postoperative pain in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023, 3, Cd014876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Suda N, Hernandez JC, Poulton J, Jones JP, Konsoula Z, Smith C, et al. Therapeutic doses of paracetamol with co-administration of cysteine and mannitol during early development result in long term behavioral changes in laboratory rats. PLoS One. 2020, 16, e0253543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippot G, Gordh T, Fredriksson A, Viberg H. Adult neurobehavioral alterations in male and female mice following developmental exposure to paracetamol (acetaminophen): characterization of a critical period. J Appl Toxicol. 2017, 37, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean SL, Knutson JF, Krebs-Kraft DL, McCarthy MM. Prostaglandin E2 is an endogenous modulator of cerebellar development and complex behavior during a sensitive postnatal period. Eur J Neurosci. 2012, 35, 1218–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Philippot G, Hosseini K, Yakub A, Mhajar Y, Hamid M, Buratovic S, et al. Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) and its Effect on the Developing Mouse Brain. Frontiers in toxicology. 2022, 4, 867748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Klein RM, Rigobello C, Vidigal CB, Moura KF, Barbosa DS, Gerardin DCC, et al. Gestational exposure to paracetamol in rats induces neurofunctional alterations in the progeny. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2020, 77, 106838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker BH, Rafikian EE, Hamblin PB, Strait MD, Yang M, Pearson BL. Sex-specific neurobehavioral and prefrontal cortex gene expression alterations following developmental acetaminophen exposure in mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2023, 177, 105970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Blecharz-Klin K, Wawer A, Jawna-Zboińska K, Pyrzanowska J, Piechal A, Mirowska-Guzel D, et al. Early paracetamol exposure decreases brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in striatum and affects social behaviour and exploration in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2018, 168, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanno SI, Tomizawa A, Yomogida S, Hara A. Glutathione peroxidase 3 is a protective factor against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in vivo and in vitro. Int J Mol Med. 2017, 40, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Posadas I, Santos P, Blanco A, Muñoz-Fernández M, Ceña V. Acetaminophen induces apoptosis in rat cortical neurons. PLoS One. 2010, 5, e15360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Donovan AP, Basson MA. The neuroanatomy of autism - a developmental perspective. J Anat. 2017, 230, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Casanova MF, Sokhadze EM, Casanova EL, Opris I, Abujadi C, Marcolin MA, et al. Translational Neuroscience in Autism: From Neuropathology to Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Therapies. The Psychiatric clinics of North America. 2020, 43, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dong D, Zielke HR, Yeh D, Yang P. Cellular stress and apoptosis contribute to the pathogenesis of autism spectrum disorder. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research. 2018, 11, 1076–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lv MN, Zhang H, Shu Y, Chen S, Hu YY, Zhou M. The neonatal levels of TSB, NSE and CK-BB in autism spectrum disorder from Southern China. Translational neuroscience. 2016, 7, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stancioiu F, Bogdan R, Dumitrescu R. Neuron-Specific Enolase (NSE) as a Biomarker for Autistic Spectrum Disease (ASD). Life (Basel, Switzerland). 2023, 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ham A, Chang AY, Li H, Bain JM, Goldman JE, Sulzer D, et al. Impaired macroautophagy confers substantial risk for intellectual disability in children with autism spectrum disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glick D, Barth S, Macleod KF. Autophagy: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Pathol. 2010, 221, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Du K, Farhood A, Jaeschke H. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant Mito-Tempo protects against acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Arch Toxicol. 2017, 91, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Frye RE, Sequeira JM, Quadros EV, James SJ, Rossignol DA. Cerebral folate receptor autoantibodies in autism spectrum disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2013, 18, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutabarat RM, Unadkat JD, Kushmerick P, Aitken ML, Slattery JT, Smith AL. Disposition of drugs in cystic fibrosis. III. Acetaminophen. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1991, 50, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearns, GL. Hepatic drug metabolism in cystic fibrosis: recent developments and future directions. Ann Pharmacother. 1993, 27, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts ID, Krajbich I, Way BM. Acetaminophen influences social and economic trust. Scientific Reports. 2019, 9, 4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewall CN, Macdonald G, Webster GD, Masten CL, Baumeister RF, Powell C, et al. Acetaminophen reduces social pain: behavioral and neural evidence. Psychol Sci. 2010, 21, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durso GRO, Luttrell A, Way BM. Over-the-Counter Relief From Pains and Pleasures Alike: Acetaminophen Blunts Evaluation Sensitivity to Both Negative and Positive Stimuli. Psychol Sci. 2015, 26, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randles D, Kam JWY, Heine SJ, Inzlicht M, Handy TC. Acetaminophen attenuates error evaluation in cortex. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2016, 11, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, J. A history of drug advertising: the evolving roles of consumers and consumer protection. Milbank Q. 2006, 84, 659–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimland, B. The autism increase: research needed on the vaccine connection. Autism Research Review International. 2000.

- Howard CR, Howard FM, Weitzman ML. Acetaminophen analgesia in neonatal circumcision: the effect on pain. Pediatrics. 1994, 93, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim YS, Leventhal BL, Koh YJ, Fombonne E, Laska E, Lim EC, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in a total population sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2011, 168, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, G. 2.64% of South Korean children aged 7 to 12 have autism spectrum disorders. Evidence Based Mental Health. 2012, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall C, Smith M. Increased cGMP enforcement has gone international: South Korean action against Johnson & Johnson serves as warning. White Collar Watch. 2013.

- Green MD, Shires TK, Fischer LJ. Hepatotoxicity of acetaminophen in neonatal and young rats. I. Age-related changes in susceptibility. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1984, 74, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raz R, Weisskopf MG, Davidovitch M, Pinto O, Levine H. Differences in autism spectrum disorders incidence by sub-populations in Israel 1992-2009: a total population study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015, 45, 1062–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kacker S, Tobian AA. Male circumcision: integrating tradition and medical evidence. The Israel Medical Association journal : IMAJ. 2013, 15, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Anvik, JO. Acetaminophen toxicosis in a cat. The Canadian veterinary journal = La revue veterinaire canadienne. 1984, 25, 445–447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Savides MC, Oehme FW, Nash SL, Leipold HW. The toxicity and biotransformation of single doses of acetaminophen in dogs and cats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1984, 74, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Court, MH. Feline drug metabolism and disposition: pharmacokinetic evidence for species differences and molecular mechanisms. The Veterinary clinics of North America Small animal practice. 2013, 43, 1039–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lautz LS, Jeddi MZ, Girolami F, Nebbia C, Dorne J. Metabolism and pharmacokinetics of pharmaceuticals in cats (Felix sylvestris catus) and implications for the risk assessment of feed additives and contaminants. Toxicology letters. 2021, 338, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller RP, Roberts RJ, Fischer LJ. Acetaminophen elimination kinetics in neonates, children, and adults. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1976, 19, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook SF, Stockmann C, Samiee-Zafarghandy S, King AD, Deutsch N, Williams EF, et al. Neonatal Maturation of Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) Glucuronidation, Sulfation, and Oxidation Based on a Parent-Metabolite Population Pharmacokinetic Model. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2016, 55, 1395–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Freed GL, Clark SJ, Butchart AT, Singer DC, Davis MM. Parental vaccine safety concerns in 2009. Pediatrics. 2010, 125, 654–659. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazzano A, Zeldin A, Schuster E, Barrett C, Lehrer D. Vaccine-related beliefs and practices of parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. American journal on intellectual and developmental disabilities. 2012, 117, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakefield AJ, Murch SH, Anthony A, Linnell J, Casson DM, Malik M, et al. Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Lancet. 1998, 351, 637–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, S. Understanding Autism: My Quest for Nathan: Schultz Publishing LLC; 2013. 92 p.

- Aguiar AG, Mainegra FD, García RO, Hernandez FY. Diagnosis in children with autism spectrum disorders in their development in textual comprehension. Rev Medical Sciences. 2016, 20, 729–737. [Google Scholar]

- Kosteva, D. A Peek at Pharmacy Practice in Cuba: Pharmacy Times; 2016. Available from: https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/a-peek-at-pharmacy-practice-in-cuba.

- Yeldham C. Going to Cuba? Here’s What Else To Pack: STARTUP CUBA.TV; 2021 [cited 2024 December 18]. Available from: https://startupcuba.tv/2021/11/10/going-to-cuba-heres-what-else-to-pack/.

- Sainsbury B. 20 things to know before visiting Cuba: Lonely Planet; 2024 [cited 2024 December 18]. Available from: https://www.lonelyplanet.com/articles/things-to-know-before-traveling-to-cuba.

- Preparing for Cuba: The Ultimate Packing List For Health & Safety: Simply Cuba Tours; 2023 [cited 2024 December 18]. Available from: https://simplycubatours.com/preparing-for-cuba-the-ultimate-packing-list-for-health-safety/.

- How to Support Local Cubans When You Travel to Cuba: Locally Sourced Cuba Tours; [cited 2024 December 18]. Available from: https://locallysourcedcuba.com/how-to-support-locals-in-cuba/.

- Maher, B. Personal genomes: The case of the missing heritability. Nature. 2008, 456, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts AL, Lyall K, Rich-Edwards JW, Ascherio A, Weisskopf MG. Maternal exposure to childhood abuse is associated with elevated risk of autism. JAMA psychiatry. 2013, 70, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Evidence/References | Background/Additional Information |

|---|---|

| 1. Mechanisms of APAP-mediated injury are plausible. For review, see Jones et al. [4] | The first study showing that children with ASD are deficient in a metabolic pathway necessary to safely detoxify APAP in babies (sulfation) is now more than a quarter of a century old [60], and was subsequently corroborated [61,62]. One enzyme (CyP450 2E1) which produces the toxic metabolite of APAP (NAPQI) is expressed in the human brain from before birth [63], and polymorphisms in another enzyme (CyP450 1A2) that produces the same toxic metabolite of APAP is associated with ASD [64,65]. |

| 2. APAP use during early childhood is associated with a 20-fold greater risk of regressive ASD [9]. | This case-controlled study, now more than 16 years old, has been widely criticized, but careful analysis does not reveal any valid objections [1]. |

| 3. APAP use with an adverse reaction to a vaccine, but not an adverse reaction to a vaccine alone, is associated with ASD [9]. | This study, the same as in line of evidence #2, was the first study to separate the impact of vaccines from APAP on neurodevelopment, and the first to directly connect APAP with ASD. |

| 4. APAP was never demonstrated to be safe for neurodevelopment [10]. Over two thousand papers in the medical literature claim that APAP is safe for babies and/or children when used as directed, but all studies were based on the false assumption that adverse reactions in babies would be the same as in adults [10]. | Like APAP, opioids have also never been shown to be safe for neurodevelopment [66]. However, unlike APAP, opioids are not generally assumed to be safe for neurodevelopment when used as directed. Further, one study probing the safety of in utero opioid exposure found reductions in communication skills in children associated with in utero APAP exposure, but not with in utero opioid exposure [31]. |

| 5. Numerous studies in laboratory animals from multiple laboratories indicate that early life exposure to APAP causes long term changes in brain function [40,67,68,69,70,71,72,73]. | After adjusting for weight, the amount of APAP that causes profound changes in laboratory animals in some studies is very close to [40] or even less than [67] the amount administered to human babies and children. Thus, APAP could never be used in babies or children if current guidelines for drug safety were applied. |

| 6. Early life exposure to APAP has a greater long-term impact on male laboratory animals than female laboratory animals [69,72,74]. ASD is more common in males than in females. | The reason or reasons why males are more susceptible to APAP-mediated injury has been considered in some detail [69,74], but the answer is not entirely known. |

| 7. In utero exposure of laboratory rats to APAP causes problems with the processing of sound [5]. Some degree of auditory dysfunction is seen in the majority of individuals with ASD. Reviewed by Graeca and Kulesza [5]. | The investigators found developmental delays with ear opening and, essentially, difficulty with hearing later in life after exposure to APAP as a fetus. It is unknown whether these affects in laboratory animals are related to impairments in some individuals with ASD. |

| 8. APAP causes apoptosis-mediated death of cortical neurons in laboratory rats [75], and cortical neurons may be involved in the pathology of ASD [76,77]. | Increased levels of biomarkers for neuronal apoptosis [78,79,80] and impaired autophagy [81] are associated with ASD. Autophagy is necessary to clearing damaged organelles such as mitochondria [82], which are created by aberrant metabolism of APAP [83]. |

| 9. Genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors associated with an increased risk of ASD have an adverse effect on the body’s ability to safely metabolize APAP [13,60,84]. | The wide array of factors associated with ASD have led to the hypothesis that many things can come together to cause ASD, but ASD is characterized by impairment of social function and other particular phenotypes, suggesting specificity in the etiology of the condition. |

| 10. Cystic fibrosis is associated with unusually efficient (effective) metabolism of APAP [85,86], and the prevalence of ASD is apparently very low in patients with cystic fibrosis [13]. | The mental health of patients with cystic fibrosis has been characterized extensively, but no association between ASD and cystic fibrosis has been reported. |

| 11. APAP temporarily blunts social trust [87] and awareness [88], emotional responses to external stimuli [89], and the ability to identify errors [90] in adults. | Although the mechanisms are unknown, these studies show that APAP affects aspects of mental function that are impaired in individuals with ASD. |

| 12. Higher levels of APAP in cord blood are associated with ASD [14]. | For the analysis, the authors divided the women into three groups based on cord blood APAP levels. The third with the highest levels had 3.6 times more likelihood of having a child with ASD that the third with the lowest levels of APAP. |

| 13. Use of APAP during pregnancy has been associated with adverse long-term effects on the mental function of offspring in numerous studies [14,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. | This line of evidence has received more attention than any other line of evidence, to the point of being the only line of evidence considered by many investigators. However, the numerous studies underpinning this line of evidence are hampered by several factors which can cause underestimation or overestimation of the association between APAP and ASD [4]. A recent study found a dramatic association (OR for ASD with APAP use = 1.8) [16], but incorrectly and completely cancelled out that association using an error in the assumptions underlying the statistical analysis [2,4]. |

| 14. Analysis of the Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC) revealed an odds ratio (OR) of 1.3 (CI 1.02–1.66) for ASD associated with postnatal APAP exposure [30], despite the fact that the use of APAP appears to be dramatically underreported in the DNBC [1]. | The study authors averaged the results from the DNBC with assessments of autism-like symptoms (not ASD) from smaller data sets, and reported no association between APAP use and those symptoms (not ASD) in the abstract of the paper. This issue has been addressed in detail by us in the literature [1,2], but unfortunately may still result in confusion [5]. In addition, the study employed invalid statistical adjustments expected to underestimate the association between APAP and ASD [2,4]. See text for additional discussion. |

| 15. The incidence of ASD began to increase in the early 1980s, coinciding with the increase in APAP use after aspirin was associated with Reye’s syndrome [13] | Temporal associations do not prove causality, but are a necessary prerequisite for causality to exist. Alternative explanations for the rise in prevalence of ASD face several insurmountable problems, previously reviewed [1,4]. |

| 16. The incidence of ASD has steadily increased [13] as direct-to-consumer advertising [91] and perhaps other factors such as mandated use of APAP with the MenB vaccine (see discussion) have led to increased APAP exposure early in life. | Temporal associations do not prove causality, but are a necessary prerequisite for causality to exist. Alternative explanations for the rise in prevalence of ASD face several insurmountable problems, previously reviewed [1,4]. A likely explanation for the persistence of such alternative explanations is that most investigators are unaware of a satisfactory explanation consistent with available evidence. |

| 17. The ratio of regressive to infantile ASD rose at the same time as pediatric APAP use rose [92] after aspirin was associated with Reye’s syndrome [13]. | This observation, made in 2000, would suggest that something was introduced into the environment that could induce ASD after months or even years of neurodevelopment. This factor was tragically and incorrectly suspected to be a vaccine at that time, an issue that was decisively addressed by Stephen Schultz eight years later (see line of evidence #3). |

| 18. Circumcision of males is associated with a 2-fold increase in the risk for early-onset (infantile) ASD [41]. | Circumcision is often performed using APAP as an analgesic despite the fact that such use is of highly questionable effectiveness [93]. |

| 19. The popularity of APAP use and the prevalence of ASD was substantially higher in Denmark than in Finland in the mid-2000s [3]. | Geographic-dependent associations do not prove causality, but do provide evidence to be considered. Particularly in the absence of alternative explanations, these associations can be compelling. |

| 20. An exceptionally high prevalence of ASD was identified in South Korea [94,95] following repeated findings of levels of APAP exceeding the package label of children’s products [96]. | Repeating mistakes made when the initial determination of APAP safety for pediatric use was determined (See line of evidence #4), public health authorities assessed the prevalence of reports of liver failure in the pediatric population, and determined that no harm was caused by the excess active ingredient (APAP) in the formulation. Liver failure is the primary adverse event from APAP overdose in adults. However, a study in laboratory animals in the 1980s demonstrated that the liver is not susceptible to APAP-mediated injury in very young animals, even with lethal doses of APAP [97]. |

| 21. Ultra-Orthodox Jews [98] in Israel have a reported prevalence of ASD less than half of that of reform Jews. Traditional circumcision practices employed by Ultra-Orthodox Jews do not utilize APAP. | Circumcision is often performed using APAP as an analgesic despite the fact that such use is of highly questionable effectiveness [93]. Almost all Israeli Jews are circumcised [99]. |

| 22. APAP is not used in domestic cats because they lack of a robust glucuronidation-dependent capacity for metabolism [100,101,102,103], making them susceptible to APAP-mediated injury. Human neonates also lack a robust glucuronidation-dependent pathway [104,105]. | Based on liver function in human babies and children, APAP was incorrectly determined to be safe for pediatric use in the 1960s and 1970s (see line of evidence # 4), before this evidence from veterinary science became available in the 1980s. One study in laboratory animals in the 1980s showed that even lethal doses of APAP do not cause liver failure in neonates [97], but the first study showing APAP-mediated neurodevelopmental brain injury in laboratory animals was not published until 2013 [40]. |

| 23. Surveys show that up to 50% of parents who have a child with ASD believe that their children’s ASD was induced by a vaccine [106,107]. | Although this belief has been widely attributed to a 1998 report describing 12 patients [108], the title of that report is not intelligible to individuals outside of the medical profession, and medical papers have seldom affected public opinion. A more likely explanation involves the induction of ASD by APAP use concurrent with vaccination, as suggested by Schultz [9,109]. |

| 24. Studies in several countries with chronic shortages of medication found dramatically lower-than-expected levels of ASD relative to other developmental issues, including Down syndrome. Reviewed by Jones et al. [4] | Not included in the previous review of this issue [4] is the apparently low levels of ASD in Cuba, where 241 cases of ASD in the entire nation (1 in 25,000 children) have been identified based on a 2016 report [110]. APAP is available in Cuba by prescription only [111], and multiple travel advisors cite APAP in particular as being in short supply in Cuba [112,113,114,115]. |

| 25. APAP binds directly to arachidonic acid [7] and affects arachidonic acid metabolism [6]. Alterations of arachidonic acid are associated with ASD [8]. | It is unknown what role arachidonic acid plays in ASD, but arachidonic acid plays a role in both the analgesic and antipyretic properties of APAP, and its metabolism is associated with ASD. |

| 26. The “missing heritability” paradox of ASD suggests that epigenetic factors or very early exposure to environmental factors might influence the onset of ASD [116]. | The role of APAP in the induction of ASD nicely resolves the missing heritability paradox connected with ASD, in which sibling studies indicate a high contribution of genetics, but genome wide studies fail to identify the genes involved [116]. The observation that abuse of a mother when she was a child is associated with ASD in the offspring [117] is one example of evidence that supports this view. |

| 27. ASD and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) are similar in many regards. Reviewed by Jones et al. [4] | This observation demonstrates that a complex spectrum disorder (FASD) sharing many similarities with ASD can (a) be induced by a single chemical and (b) be influenced by a variety of genetic and environmental factors. |

| Variable | HR (CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| APAP, actual risk built into virtual construct | 2.667 (NA) | NA |

| APAP, result of regression analysis | 2.55 (2.41-2.71) | 2 x 10-16 |

| APAP, adjusted for all contributing cofactors | 0.85 (0.80-0.90) | 2 x 10-7 |

| OS factor 1, all individuals | 1.24 (1.23-1.26) | 2 x 10-16 |

| OS factor 1, virtual individuals with APAP use only | 1.32 (1.30-1.34) | 2 x 10-16 |

| OS factor 1, virtual individuals with no APAP use only | 1.00 (0.97-1.03) | 0.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).