1. Introduction

The vaccine efforts during the height of the pandemic were instrumental in decreasing the morbidity and mortality of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak and gave rise to several vaccines to combat the disease - BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech), mRNA-1273 (Moderna), Ad26.COV2.S (Janssen), and NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax)[

1,

2,

3]. All of the currently FDA approved vaccines utilize the spike (S) glycoprotein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus as antigen[

1,

3]. However, as a result of the emergence of mutation-carrying variants of concern (VOC), it has become imperative for researchers to identify an alternative antigen from a more conserved portion of the virus that is still accessible to antibodies.

The SARS-CoV-2 viral genome is approximately 29.7kb and encodes a total of 29 proteins that include 16 nonstructural proteins, 4 structural proteins, and 9 accessory open reading frames (ORFs)[

4]. Among them is the protein ORF3a, which has been discovered to be the largest accessory protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. ORF3a protein has been assigned significant roles in viral pathogenesis and disease severity of COVID-19[

4,

5], mainly in the form of cell membrane permeability, Ca

2+ homeostasis, viral entry and replication, and release of viral particles[

5]. This impact on COVID-19 disease severity comes in the form of a cytokine storm induction where ORF3a has been observed to induce a pro-inflammatory immune response in infected cells, activating the NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, and creating a hyper-inflammatory response[

5].

The rationale for targeting the ORF3a protein follows recent literature regarding its significant contribution to disease severity and viral pathogenesis. Most notably, the 1-34 N-terminal ectodomain of ORF3a has been found to be highly conserved and is a viable therapeutic target due to its presence on the surface of the virion. Historically, both cell and humoral-based immunity have been essential for control of infection[

6,

7,

8], and since this region is exposed on the virion surface, it is accessible to antibodies unlike other internal nonstructural proteins that are highly conserved, such as the nucleoprotein (NP). Further, ORF3a has been found to contain immunodominant T-cell responses in people[

9,

10,

11].

CCL20, also known as macrophage inflammatory protein-3 alpha (MIP-3α), is the only chemokine that has high specificity for the chemokine receptor CCR6, which is highly expressed on several human cell types including immature dendritic cells (iDCs), effector/memory CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, and interleukin-17 (IL-17) producing T cells (TH

17)[

12]. The ligand-receptor pair of CCL20-CCR6 is also responsible for the chemoattraction of iDCs and plays a role in the pathogenesis and pathology of several inflammatory diseases including cancer, psoriasis, and rheumatoid arthritis[

12,

13]. Therapeutically, MIP-3α has also been utilized to enhance the immunogenicity of DNA vaccination when fused to an antigen by increasing DC trafficking, targeting, and activation[

14,

15,

16]. Previous disease models using Haemophilus influenzae, GFP, melanoma, tuberculosis, malaria, and the SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain have all found MIP-3α to be an effective iDC targeting agent that has the potential to be utilized to achieve antigen specific protective immunity[

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

Here, we present our immunological findings of vaccines in murine models targeting the ORF3a ectodomain, including a DNA vaccine expressing MIP3α-ORF3a6-34 administered intramuscularly (IM) with electroporation or intranasally with CpG adjuvant, as well as a peptide vaccine of ORF3a15-28 fused to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) administered systemically with Addavax adjuvant. Our results indicate that the DNA formulation elicits ORF3a-specific T-cell responses in the spleen with IM and in the lung with IN immunizations. Our studies further indicate that the peptide vaccine elicits an anti-ORF3a antibody response in the serum as well as in the lung and sinuses. We show that this highly conserved, antibody-accessible region of SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a can be targeted by vaccines eliciting T-cell and antibody-based responses in the lung.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

C57BL/6 or BALB/C mice (4-5 weeks old) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) and maintained in a pathogen-free micro-isolation facility in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the humane use of laboratory animals. Strain and Sex will be noted in figure legends. All experimental procedures involving mice were approved by the IACUC of Johns Hopkins University (Protocol Number: MO23H131). Experiments began after the mice reached 6 to 10 weeks of maturity.

2.2. DNA Vaccine Plasmid Construction and Verification

A pUC57 plasmid containing DNA encoding mouse codon-optimized

MIP3α-ORF3a6-34 was purchased from GenScript (Piscataway, NJ, USA) and was reconstituted (200 ng/µl) and transformed into DH5-α E. coli cells (Invitrogen™ Thermo Fisher Scientific (TFS), Waltham, MA, USA). Transformed bacteria were selected with ampicillin (100 mg/ml) (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA). DNA was then extracted from the transformed bacteria using a Qiagen (Germantown, MD) QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit. DNA quality, amount, and correctness were verified by agarose gel electrophoresis, restriction enzyme analysis, and NanoDrop (TFS) spectrophotometry. The

MIP3α- ORF3a6-34 containing plasmid was then cut using HindIII and BamHI (New England BioLabs, Inc. (NEB), Ipswich, MA) restriction enzymes and ligated into a previously generated pSecTag2b plasmid[

21].

Myc-His tag regions were synthesized to help detect the expressed protein using gBlocks Gene Fragments from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). The sequence is as follows: 5’ GGTGAACGAGCGGCGATACGCGGATCCAGATCCGCAGAAGAACAGAAACTGATCTCAGAAGAGGATCTGGCCCACCACCATCACCATCACTAAGAATTCACTCGGATCTTACACTCTAGCCGGACATGC 3’. The Myc-His tag fragments were then cut using BamHI and EcoRI restriction enzymes (NEB) and cloned into the previously ligated pSecTag2b product. A second version of the vaccine was created in the same way, but with an additional PADRE sequence (AKFVAAWTLKAAA) between the antigen and the tags.

The resulting ligation was then transformed into DH5-α E. coli cells (Invitrogen). Bacteria were then selected with ampicillin (100 mg/ml). DNA was extracted from the bacteria containing the ligated product using Qiagen EndoFree Plasmid Kits and was diluted with endotoxin-free 1x PBS to 400 ng/µl. DNA quality, amount, and correctness were verified once again by agarose gel electrophoresis, restriction enzyme analysis, and NanoDrop spectrophotometry.

2.3. Mammalian Cell Transfection

HEK293T cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured at 37ºC and 5% CO2 using DMEM (Gibco™, TFS) media, containing 4.5g/L glucose, 4% L-glutamine, and 110mg/L sodium pyruvate, with additions of 10% FBS (Heat inactivated, Millipore Sigma), and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (10,000 U/ml, Gibco™, TFS). HEK293T cells were plated at a seeding density of 2 x 105 cells/well into a Falcon Multiwell 12-well tissue culture treated plate (Corning, Inc.; Corning, NY). Plate was kept at 37ºC and 5% CO2 until the cell culture reached approximately 70% confluency. The cells were then transfected with 5 µg/well of the MIP3α-ORF3a6-34 DNA vaccine using the Lipofectamine 3000 Reagent Protocol supplied by Invitrogen and then returned to the incubator at 37ºC and 5% CO2 for 72 hours.

2.4. Western Blot

After 72 hours, protein from cell lysates and culture supernatants were collected. Cell supernatant was then concentrated using an Amicon-Ultra 4kd centrifuge tube (Millipore Sigma) and spun for an hour. Both cell lysates and culture supernatants were then run on precast TGX Gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 150V for 30 minutes and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). The membrane was then blocked with a 5% milk solution containing 1x TBS (Quality Biological, Gaithersburg, MD), probed with anti-C-myc (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) at RT for 2 hours at 1:5000 dilution, washed, probed with AP-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA, USA) at 1:1000 dilution for 1 hour, washed, and visualized with NBT-BCIP reagent (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.5. Vaccine Administration

MIP-3αORF3a vaccine formulations were diluted in 1x endotoxin-free PBS to 400 ng/µl and were administered intramuscularly (IM) by injection of 50 µl (20µg) into the right gastrocnemius muscle of each mouse. Saline group received 50 µl of 1x endotoxin-free PBS. Vaccinations were given to all three groups at 2-week intervals for a total of three doses and were accompanied by electroporation[

25,

26]. Blood was obtained by tail vein nicking just prior to each vaccination and processed for ELISA-based detection of anti-ORF3a antibodies. Local electroporation was administered using an ECM830 square wave electroporation (EP) system (BTX Harvard Apparatus Company, Holliston, MA, USA). Each of the two-needle array electrodes delivered 15 pulses of 72V (a 20-ms pulse duration at 200-ms intervals). The weights of each mouse were also recorded prior to each vaccination (

Supplemental Figure S1). For the purposes of this study, both vaccine groups were combined since the PADRE formulation showed no immunological difference from the original

MIP-3αORF3a vaccine (

Supplemental Figure S2). Pilot experiments with the same protocol except adding 50μg of CpG-B (ODN 1826, Adipogen, San Diego, CA), CpG-C (ODN 2395, Adipogen), or a STING agonist (2’3’-c-di-AM(PS)2 (Rp,Rp), Invivogen, San Diego, CA) at time of vaccination were also performed.

For mice immunized intranasally, mice were first anesthetized by inhaled vaporized isoflurane and then were given approximately 100μl total volume (50 per nostril) dropwise by pipette, as previously described[

21,

23]. Vaccines were prepared and mixed evenly by inversion with CpG-B or 1xPBS. Final concentrations of 2mg/ml vaccine (200μg total) and 200μg/ml CpG (20μg total) were administered.

For studies of mice immunized with ORF3a-KLH, the protein vaccine was created and verified by GenScript, with alpha strain ORF3a 15-28 region (LKQGEIKDATPSDF) fused to Keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) on the N-terminal side. Quality control measures included HPLC and Mass Spectrometry analyses performed by GenScript. Vaccines were combined with equal volume of either Addavax adjuvant (Invivogen) or 1xPBS and mixed gently. The vaccines were administered intraperitoneally at 200μl total volume at 50 or 200μg doses described in the figure.

2.6. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Serum and broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) fluid were collected as done previously[

23]. Briefly, after euthanasia by high-dose Tri-bromoethanol (TFS) administration, blood was collected by cardiac puncture, was allowed to coagulate for 1 hour at room temperature, clotted blood was pelleted, and the serum supernatant was collected. Wash fluid for BAL and nasal wash was prepared as 1× PBS with 100 μM EDTA (0.5M Corning, Glendale, AZ) and 1x protease inhibitors (200xPMSF, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Post cardiac puncture, a mouse endotracheal tube (20 G× 1 in., Kent Scientific Corp., Torrington, CT, USA) was inserted into the trachea and 0.5ml wash fluid was syringe-injected into the lungs and aspirated back into the syringe. This process was repeated once if the initial yield was less than approximately 250μl. For nasal washes, after cardiac puncture and BAL extraction, the mouse was laid on its side and 50μl of wash fluid was injected into the upper nostril by pipette and then aspirated back into the pipette from the lower nostril. The procedure was repeated once if less than 25μl was recovered. BAL and nasal fluids were transferred to tubes, cells were pelleted, and fluid supernatants were utilized.

ELISAs were performed as previously described[

23]. ELISA plate wells were coated with 1μg of ORF3a

1-34 peptide (GenScript) overnight at 4°C, washed with PBS-T (1xPBS+0.05% Tween 20), and blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature (RT). Serum or fluid dilutions were assayed as two-fold dilution series in singlicate beginning at 1:1000 for serum and 1:20 for BAL and nasal washes. Biological samples incubated for 2 hours at RT, were washed with PBS-T, and then incubated with of 1:1,000 diluted HRP goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) secondary antibody (Biotium, Fremont, CA, USA) at RT for 1 h. Wells were washed with PBS-T, and then 100 μl of KPL ABTS® Peroxidase Substrate (SeraCare Life Sciences Inc., Milford, MA, USA) was added into each well, and the plates were incubated at RT in the dark for 1 h. Data were collected using the Synergy HT at O.D.405 nm (BioTek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). Antibody titers were calculated as the highest serum dilution that registered absorbance values above (≥) the background threshold. The threshold was defined as twice the average value of technical control wells. To ensure reproducibility, intermediate serum timepoints were also tested from tail vein blood extractions and were found to be consistent with endpoint results (data not shown).

2.7. Lymphocyte Isolation

Mice were euthanized as described above. After fluid collections, spleens and lungs were collected under sterile conditions. Spleens were harvested and placed in 1x PBS on ice. Lungs were harvested and placed in 1x PBS on ice and were then transferred to wells containing 1 mL of digestion buffer (RPMI 1640 media (TFS), 100 μg/mL of Liberase TL (Millipore Sigma) , and 100 μg/mL of DNase I (Millipore Sigma)), minced with scissors, and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. Spleens and lungs were then ground gently with a pestle over 70 μM (spleens) and 40 μM (lungs) mesh filters, into 50 mL conical tubes, and immediately centrifuged at 300g for 10 minutes at 4ºC. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was fully resuspended using 1 mL ACK lysis buffer (Quality Biological, Gaithersburg, MD) and incubated at room temperature (RT) for 3-4 minutes. To stop cell lysis, cells were diluted with 30 mL of cold 1x PBS and were then pelleted at 300g for 5 minutes at 4ºC. Supernatant was again removed, and the remaining pellet was fully resuspended in 5 mL of 1x PBS. After another centrifugation under the same conditions, the supernatant was removed and the pellet was resuspended in 4 mL (spleens) or 1 mL (lungs) of freezing media (90% FBS (Heat inactivated, Millipore Sigma), 10% DMSO (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) and aliquoted into four (spleens) or two (lungs) tubes for cryo-storage using isopropanol cooling containers (Mr. Frosty, TFS) at −80°C for at least 4 hours and then moved to −150°C. Prior to use all cells were counted by hemocytometer with Gibco™ Trypan Blue solution 0.4% (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA).

2.8. T-Cell Stimulation and Flow Cytometry

Cryopreserved cells were briefly thawed at 37℃ and slowly diluted to 10mL with warm complete media (RPMI 1640 (TFS), 10% FBS (Millipore Sigma), 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco™), 20mM HEPES (TFS), 1% sodium pyruvate (Millipore Sigma), 1% non-essential amino acids (Millipore Sigma), and 1% L-glutamine (TFS)). Cells were spun at 250xg for 7 minutes at room temperature and resuspended to a final concentration of ≤1x106 cells per well in 200µL complete media. Cells incubated at humid 5% CO2 at 37℃ 2-4 hours. Cells stimulated in duplicate with 1µg ORF3α (aa. 1-34, GenScript) for 16 hours at 37℃. Positive controls stimulated for 4 hours with 1µg per well Cell Stimulation Cocktail (Biolegend). In the last 4 hours of stimulation 1µg per well anti-CD28 and anti-CD49d costimulatory antibodies and Brefeldin-A (Biolegend Cat. Nos 420601, 102116, and 103629) were added to the cells. Cells transferred to a 96-well V-bottom plate after stimulation, centrifuged 300xg for 5 minutes at room temperature, and washed with 150µL FACS buffer (0.5% BSA in 1X PBS. Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Pellets stained with Live/Dead (1:2000 dilution in 1X PBS, LIVE/DEAD Fixable Near-IR Dead Cell Stain Kit, TFS) stain with 100µL per well and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 minutes. Cells centrifuged and washed with 150µL FACS buffer. 50µL 2% Fc Block (TruStain FcX, Biolegend Cat. No 101320) added to each well and incubated on ice in the dark for 15 minutes. After centrifugation, cells were resuspended in anti-mouse extracellular stain cocktail (1:200 FITC conjugated anti-CD4, 1:200 PercPCy5.5 conjugated anti-CD3, and 1:200 Alexa Fluor 700 conjugated anti-CD8 (Biolegend Cat. Nos 100405, 100217, and 155022) in FACS) and incubated the dark for 20 minutes at room temperature. After centrifugation, cell pellets resuspended in 150µL fixation buffer (Cyto-Fast Fix/Perm Buffer Set, Biolegend, Cat. No 426803) and incubated overnight at 4℃. Fixed cells centrifuged at 500xg for 5 minutes at room temperature before staining with 50µL intracellular stain (1:100 PE conjugated anti-IL2, 1:200 PECy & conjugated anti-TNF-α, 1:100 APC conjugated IFN-y (Biolegend Cat. Nos 506323, 503808, and 505809) in 1X Perm Buffer) for 20 minutes in the dark at room temperature. 100µL perm buffer added after incubation, then plate spun down at 500xg for 5 minutes at room temperature. Pellets washed with 150µL FACS before resuspension in 150µL 1X PBS. Flow cytometry run on an Attune™ NxT Flow Cytometer (TFS). Flow data was analyzed using FlowJo software (FlowJo10.10.0, LLC, Ashland, OR, USA). Gates formed based on negative stimulation controls and FMO staining controls.

2.9. Statistics

Datasets comparing three groups were tested by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test. Datasets comparing two groups were analyzed by Welch’s T-test if standard deviations were significantly different or Student’s T-test if not, as noted in figure legends. Splenic stimulation data were excluded if there were fewer than 100 CD4+ or CD8+ T cells per well. Splenic stimulation samples were run in duplicate wells and averages of technical replicates reported. Mouse weights analyzed by Area Under the Curve (AUC) analysis, with non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals considered significant. All error bars represent the estimation of the standard error of the mean and a significance level of α ≤ 0.05 was set for all experiments. GraphPad Prism 10 (San Diego, CA, USA) was utilized for all statistical analyses and figure generation on raw, non-transformed data. The processed data is supplied in Supplemental Data File S1.

3. Results

3.1. Antigen Evolution

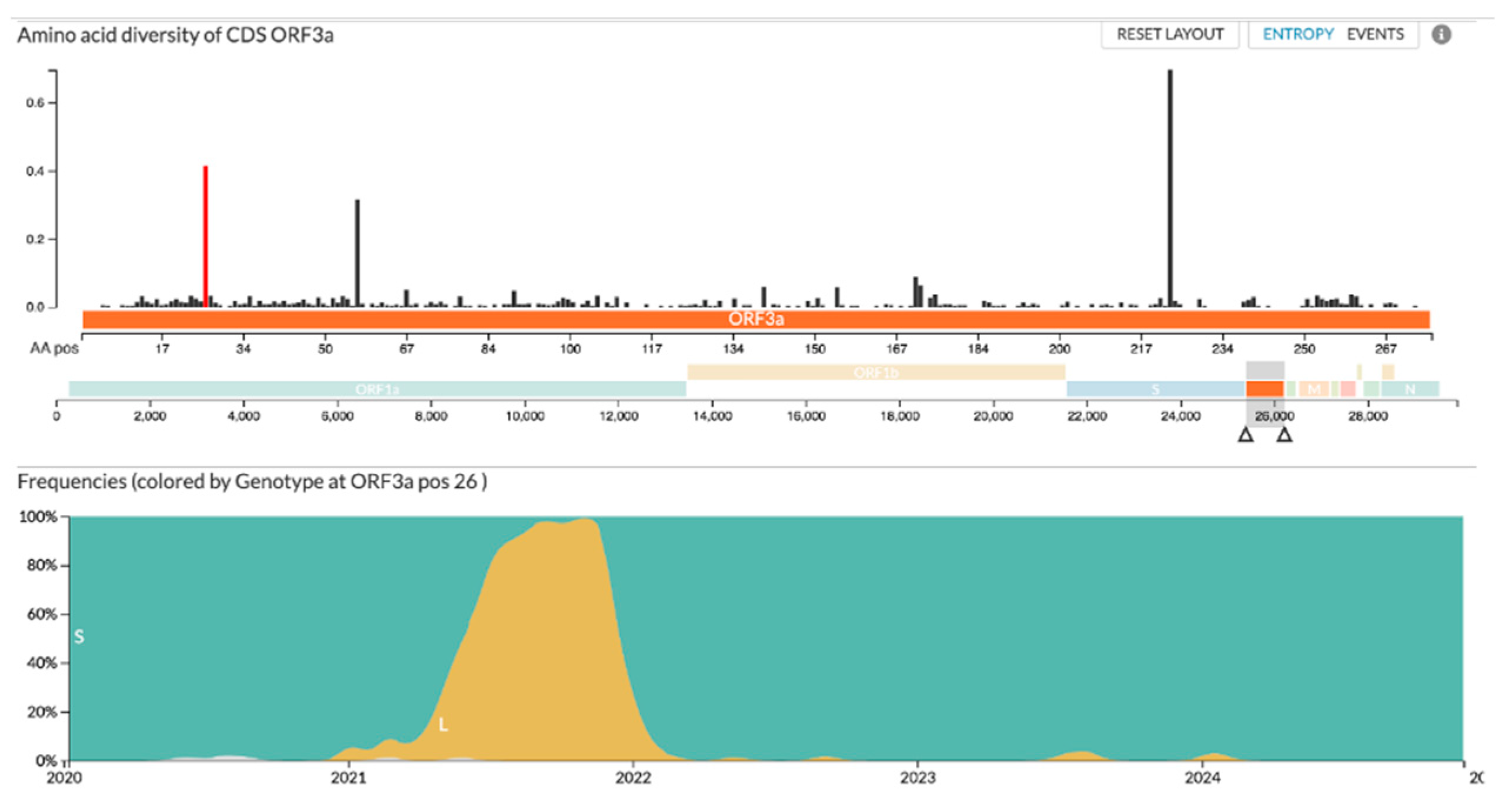

The genotypic diversity within the ORF3a protein has proven to be relatively low since the start of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic

(Figure 1). Since 2020, only one amino acid within the targeted 6-34 region has changed significantly. As shown in

Figure 1, position 26 of the ORF3a protein remained stable until the beginning of 2021 when B.1.617.2 (Delta) became the primary variant of concern, changing the serine residue to a leucine before reverting to a serine residue in early 2022 after the emergence of the Omicron variant. Importantly, the residue has remained consistent since the reversion.

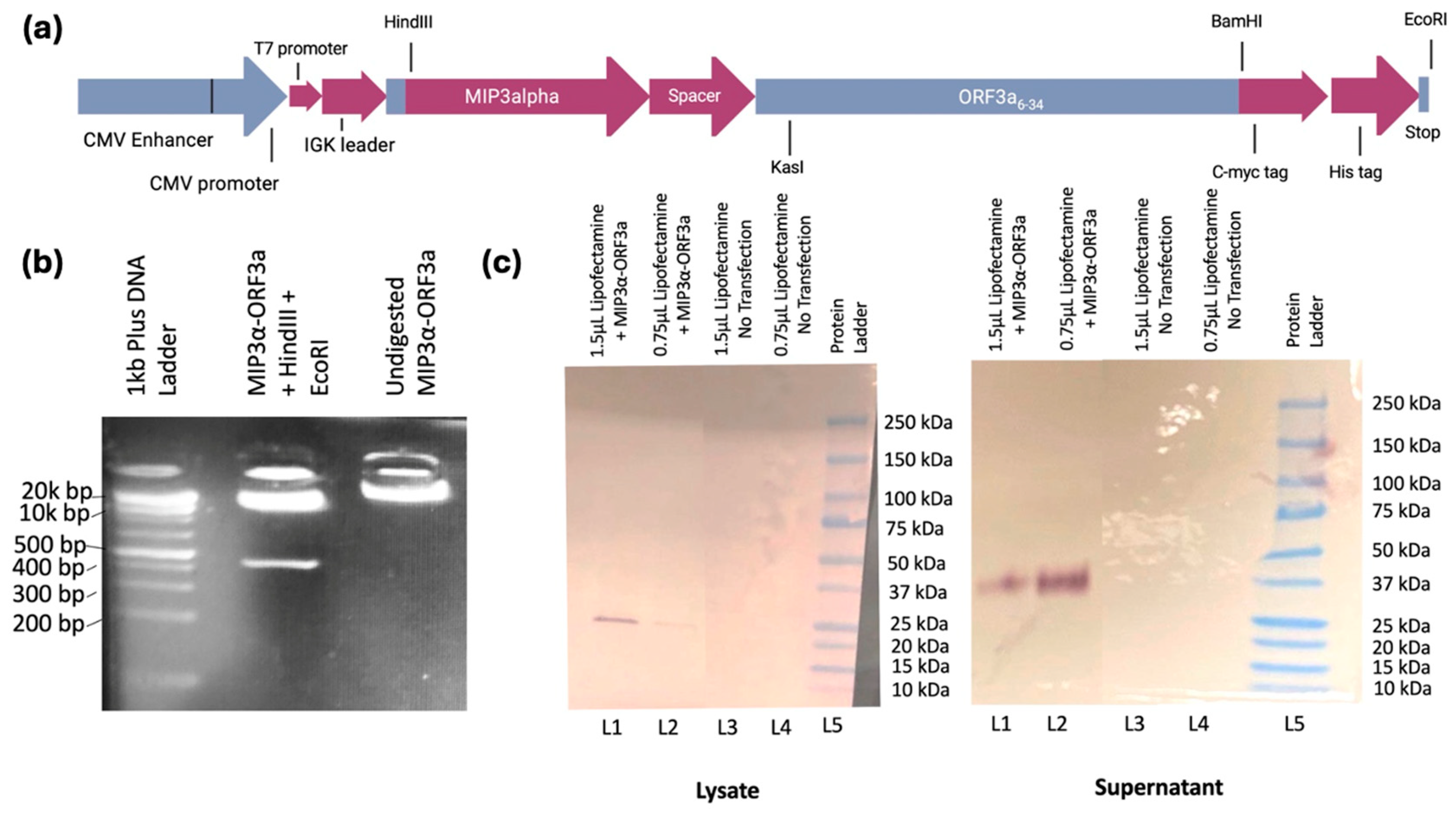

3.2. DNA Vaccine Creation

The primary hypothesis of this study was to assess whether an immunogenic vaccine targeting the evolutionarily stable ectodomain of ORF3a (amino acids 6-34) could be designed. First, a DNA vaccine was constructed fusing the

ORF3a genetic domain to the

MIP3α gene

(Figure 2a

), which has been studied extensively in our laboratory and has been shown across models to enhance immune responses[

16,

17,

18,

19,

21,

22,

23,

24].

DNA quality and correctness of the synthesized

MIP-3α-ORF3a DNA fusion vaccine in the mammalian expression vector pSecTag2b was assessed and verified by gel electrophoresis and restriction enzyme analysis (

Figure 2b) as well as insert sequencing (Supplemental Data File S2). Lane 2 shows the digest with HindIII and EcoRI results in the expected linear plasmid band and a single band representing the expressed vaccine sequence at the expected size (426bp), and lane three shows the plasmid vaccine was primarily in a supercoiled state. To ensure that the expression vector was functional in a mammalian cell, the vaccine was transiently transfected into HEK293T cells, and cell lysate and supernatants were collected. Western Blot analysis of the fusion vaccine targeting the C-terminal myc tag confirmed full length protein production that was present in the lysate at expected size (approximately 20kDa) and secreted into the supernatant likely as a dimer (approximately 40kDa) (

Figure 2c). Previous MIP3α-antigen vaccines from the laboratory have not shown dimerization[

20,

21,

23]. It is probable, therefore, that the ectodomain plays a role in the known oligomerization of ORF3a[

4].

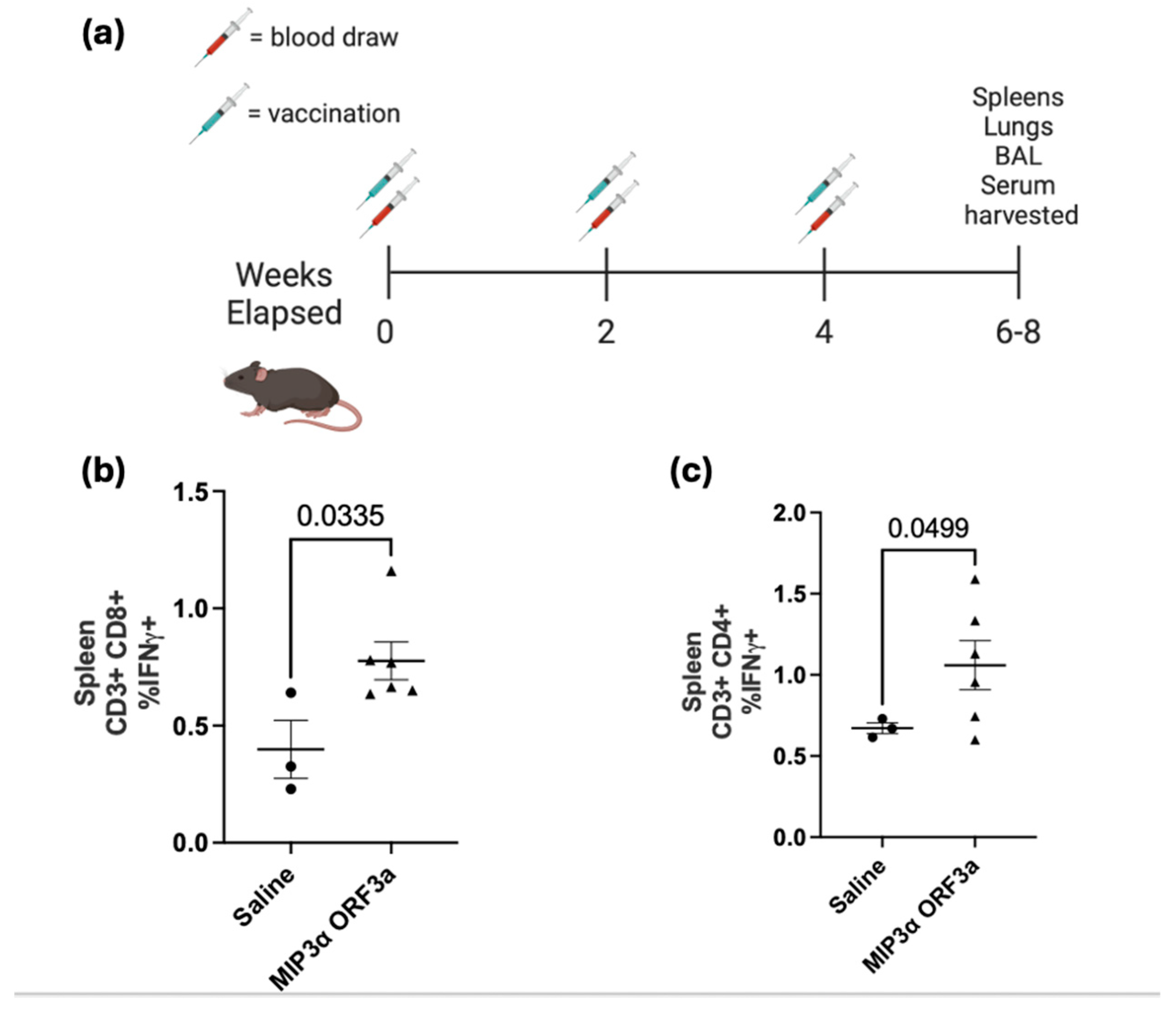

3.3. DNA Intramuscular Vaccine Immunogenicity

Utilizing a standard intramuscular electroporation vaccination schedule in a mouse model (

Figure 3a), the immunogenicity of the DNA vaccine was tested[

25,

26]. Three weeks after the third vaccination, tissues were collected. ELISA assays of serum showed insignificant antibody responses (data not shown). Splenocytes were collected and then stimulated with ORF3a peptide in the presence of cell transport inhibitors, followed by staining with surface antibodies and intracellular staining for T cell activation cytokines for analysis by flow cytometry. The lymphocytes were gated for populations of CD4 and CD8 positive T cells and then assessed for IFN-γ and TNF-α production. Our results demonstrated a significant increase (p < 0.05) in CD8+ T cell splenocytes that were positive for IFN-γ between the saline group and the MIP-3α-ORF3a vaccinated group, showing an almost two-fold difference (0.4% vs. 0.78%) (

Figure 3b). The MIP3α-ORF3a vaccinated group also demonstrated a significant increase (p < 0.05) in splenocytes that were positive for IFN-γ producing CD4+ T cells, showing an increase of 58% over background level (

Figure 3c). The splenocytes did not show increases of TNFα under the conditions tested. Pilot experiments with adjuvants also given intramuscularly showed that CpG types B and C did not dramatically increase the T-cell response over the known immunostimulatory activity of electroporation[

26,

27,

28], but the addition of a STING agonist did increase T-cell responses (

Supplemental Figure S3). However, the mice receiving the STING agonist lost weight over time, and so the experiment was not repeated due to suspected toxicity (

Supplemental Figure S1d).

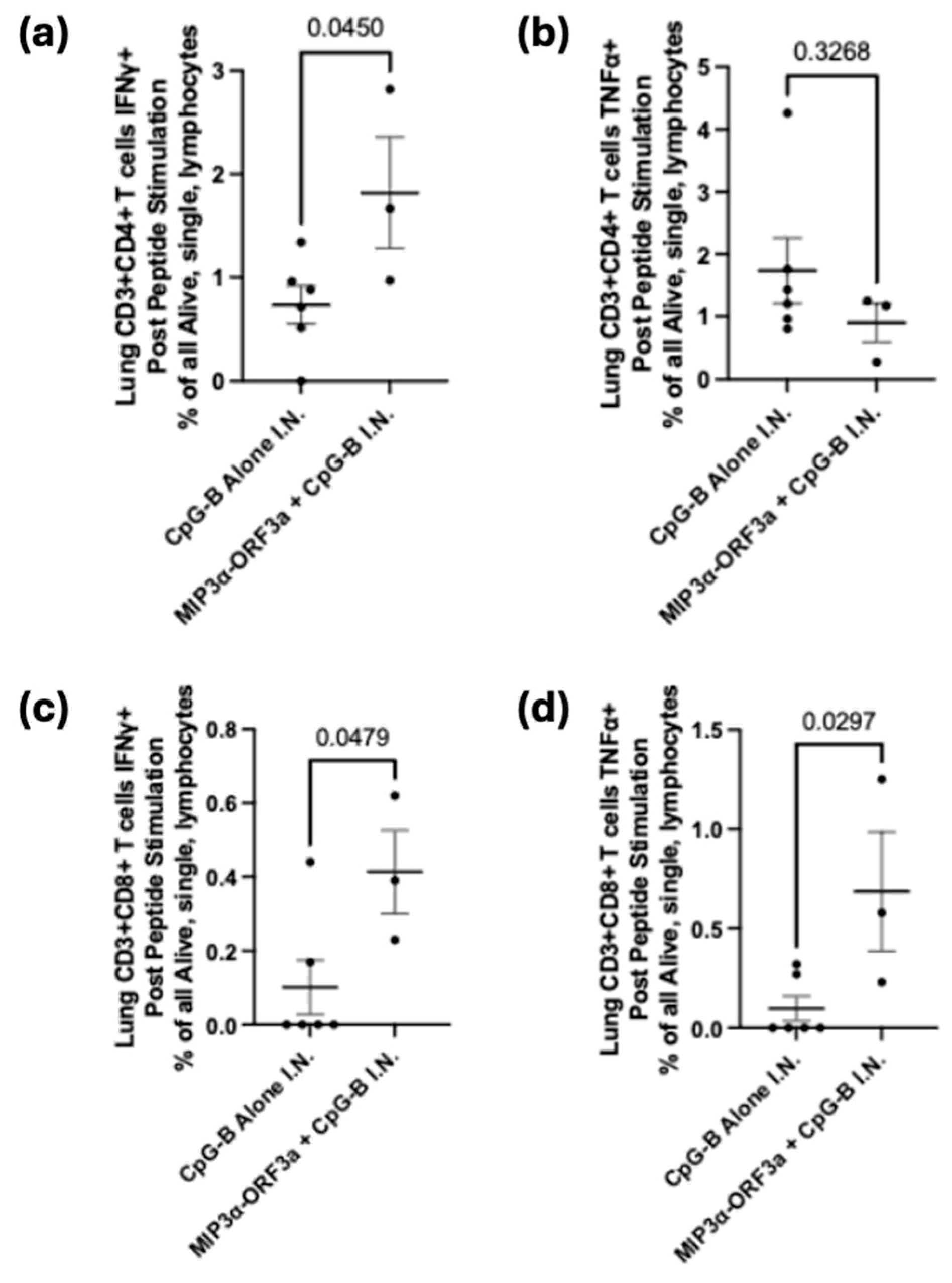

3.4. DNA Intranasal Vaccine Immunogenicity

A previous DNA vaccine fusing

MIP3α to the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor binding domain sequence proved that intranasal forms of our DNA vaccine could induce lung-associated T-cell responses[

23]. It was hypothesized that the

MIP3α-ORF3a vaccine would similarly be able to induce a T-cell response at the lung site of potential infection. To assess T-cell specificity for ORF3a after intranasal vaccination with the

MIP3α-ORF3a DNA vaccine construct, mice were immunized in the same schedule (

Figure 3a) but intranasally. To enhance responses for an intranasal DNA vaccine unable to receive electroporation, CpG-B adjuvant was mixed with the vaccine DNA. Tissues were collected two weeks after the final vaccination. Serum and lavage antibody responses were negligible (data not shown). Lungs were processed into single cells and stimulated as before. Previous work has shown that MIP3α vaccines administered intranasally were especially potent at recruiting more overall effector T cells to the lung, and so the most informative measure would be to assess responses as an overall percentage of cells and not a percentage of T cells[

23]. The CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations both demonstrate significant (p < 0.05) differences between the adjuvant only and adjuvant with DNA sample groups, with increased IFN-γ production in samples given the vaccine as well as the adjuvant (

Figure 4a,c). There is also a significant (p < 0.05) increase in TNF-α production by CD8+ T cells, but this is not seen in the CD4+ T cells (

Figure 4b,d). As demonstrated by cytokine production from CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, the intranasally-administered vaccine elicits a significant T-cell response in the critical site of the lung.

3.5. ORF3a-KLH Peptide Vaccine

We hypothesized that the specific formulation of the DNA vaccine was responsible for the lack of antibody response, and not a biological trait of the region. The specific sub-region of the ectodomain ORF3a

15-28, known to elicit an antibody response in SARS-CoV-1 systems[

29,

30,

31], was created in peptide form fused to immunogenic carrier protein Keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH). With the same schedule as

Figure 3a, mice were immunized intraperitoneally with ORF3a-KLH peptide along with Addavax adjuvant. To quantify antibody production in response to vaccine administration, sera, BAL fluid, and nasal wash fluid were collected four weeks after the third vaccination and were assessed by ORF3a-specific antibody titers. Titers form sera (

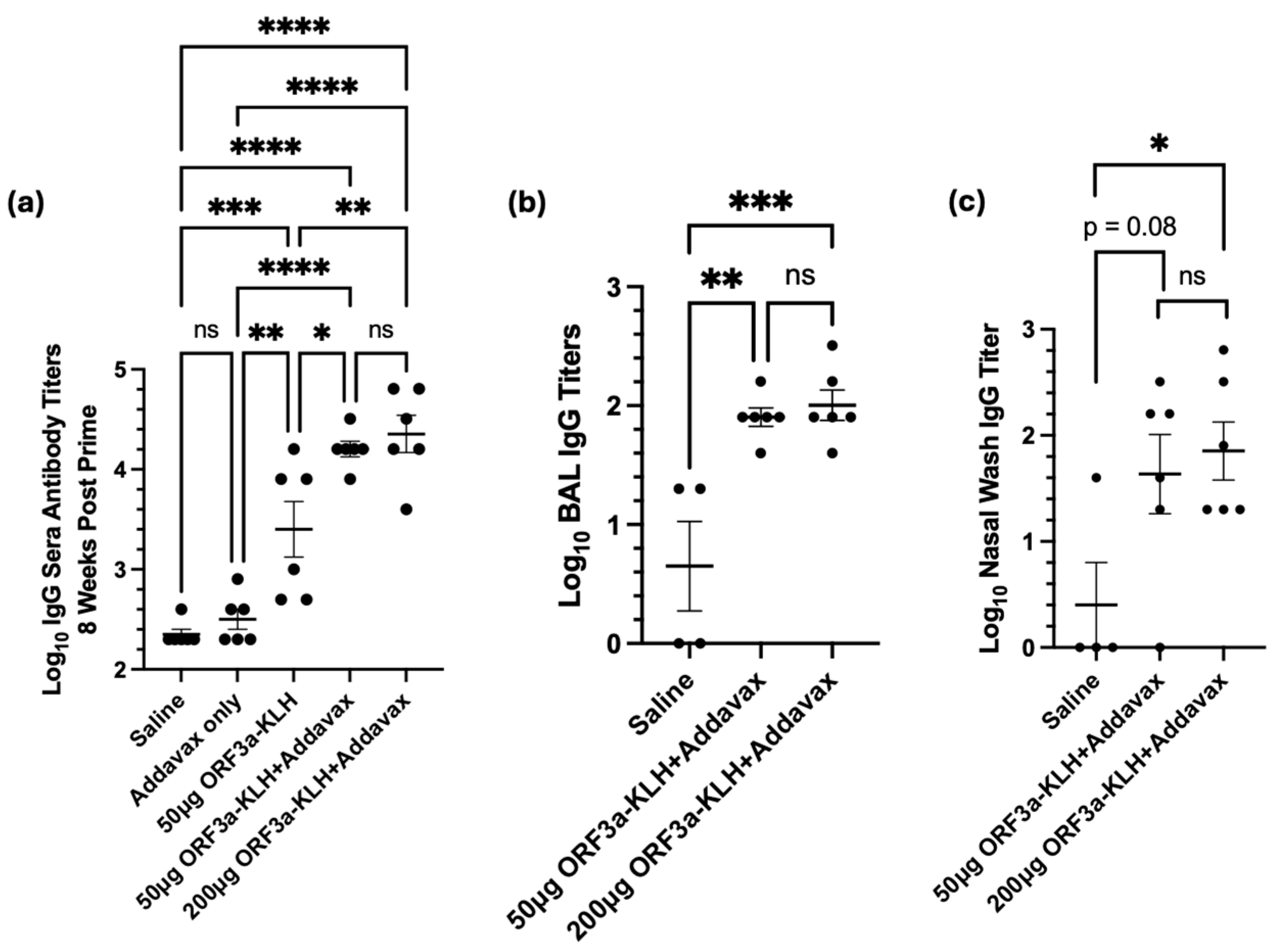

Figure 5a) showed that without adjuvant, the vaccine resulted in titers roughly one log above background (p<0.01). Addition of Addavax adjuvant further boosted the titer by almost an additional order of magnitude (p<0.05, compared to without adjuvant). Interestingly, increasing the dose to 200μg of ORF3a-KLH with Addavax did not result in higher titers as compared to 50μg.

Mucosal fluids were also tested to assess the presence of antibodies at the primary site at which SARS-CoV-2 infection and disease would be manifest. The BAL titers show significantly higher antibody levels from animals receiving the ORF3a-KLH with Addavax vaccine than in the negative control animals receiving saline. Similarly to serum, no difference is seen between the doses of 50µg or 200µg ORF3a-KLH (

Figure 5b). Nasal wash samples also provide data showing vaccine-induced antibody responses, with a significant difference (<0.05) between the saline and the 200µg ORF3a-KLH and Addavax groups, with a trend toward a significant difference (p=0.08) between the saline and the 50µg ORF3a-KLH and Addavax groups (

Figure 5c). The consistent trend seen across all collected sample sources indicates that ORF3a-KLH administered with Addavax effectively elicits an antibody response systemically and in the mucosa.

4. Discussion

The viability of the ORF3a’s ectodomain (amino acids 1-36) as a well-conserved target for SARS-CoV-2 was assessed in terms of genetic drift across variants over the past several years, visualized in

Figure 1. The amino acid composition is surprisingly well conserved across the SARS-CoV-2 variants, with only amino acid 26 being variable, starting as serine before changing to leucine with the delta strain and then back to serine with the omicron strain. With this high level of conservation in the ORF3a ectodomain demonstrated across variants, as expected based on previous literature, we believe that ORF3a presents a vaccine target that would be less susceptible to mutational escape[

5,

32,

33]. Given the challenges of targeting the highly variable spike protein, mutations in which have decreased the long-term efficacy of the available vaccines, ORF3a may be a more effective target that could increase the window of efficacy for COVID vaccines[

5,

32,

33,

34,

35].

Fusing

MIP3α and

ORF3a in a DNA vaccine elicits a significant cell-mediated immune response. With both intramuscular (i.m.) administration (with electroporation) and intranasal (i.n.) administration (with CpG adjuvant),

MIP3α-ORF3a vaccinated mice elicited significant specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses as measured by ex vivo cytokine production post stimulation of T cells from spleen (i.m.) and lung (i.n.) (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4)[

36]. This is the first study to our knowledge showing the feasibility of eliciting a T-cell response to SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a. However, the DNA vaccine formulations were unable to induce antibody responses to ORF3a

6-34. Importantly, though, the intranasal version of the DNA vaccine was able to elicit robust T-cell responses within the lung environment, which are known to be important for limiting disease severity[

6,

7]. T-cell immunity is furthermore less subject to genetic drift escape if a rare mutation event in this domain does happen[

9,

10,

11].

Therefore, a second formulation was investigated to interrogate whether an antibody response to this region could be induced by a vaccine. Instead of DNA, a peptide vaccine comprising a stable region of the ectodomain (ORF3a

15-28) was constructed and fused to immunogenic carrier molecule, Keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH)[

29,

37]. Immunogenicity mouse studies with ORF3a-KLH showed robust antibody responses induced with the combination of the vaccine with Addavax adjuvant (

Figure 5). Antibodies were detected in serum, lung lavage fluid, and also in nasal wash samples, suggesting that the immune response included the mucosal sites of initial infection. Interestingly, this vaccine was unable to elicit robust T-cell responses (data not shown).

The success of these vaccine models in developing adaptive immune responses to the highly conserved SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a ectodomain supports our hypothesis that ORF3a could be a viable vaccine target. We hypothesize that combining the intranasal administration of the DNA vaccine with the systemic administration of the peptide vaccine would elicit both specific T cell and antibody responses in the mucosal lung environment that could provide protection and/or disease mitigation for the host. Further work should be done to continue optimization of the immunization schedule and to test out this combination in an animal challenge model system[

38,

39].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Jacob Meza and Elizabeth Glass share first authorship. Conceptualization, Richard Markham and James Gordy; Formal analysis, Jacob Meza, Elizabeth Glass, Avinaash Sandhu, Styliani Karanika and James Gordy; Funding acquisition, Petros Karakousis and Richard Markham; Investigation, Jacob Meza, Elizabeth Glass, Avinaash Sandhu, Yangchen Li, Styliani Karanika, Kaitlyn Fessler, Yinan Hui, Courtney Schill, Tianyin Wang, Jiaqi Zhang, Rowan Bates, Alannah Taylor, Aakanksha Kapoor, Samuel Ayeh and James Gordy; Methodology, Jacob Meza, Avinaash Sandhu, Styliani Karanika, Aakanksha Kapoor, Samuel Ayeh and James Gordy; Project administration, Petros Karakousis, Richard Markham and James Gordy; Supervision, Petros Karakousis, Richard Markham and James Gordy; Writing – original draft, Jacob Meza and Elizabeth Glass; Writing – review & editing, Petros Karakousis, Richard Markham and James Gordy. Richard Markham and James Gordy share last authorship. All authors have approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Sea Grape Foundation to RBM and NIAID Grant 5R01AI148710 awarded to PK and RM and K24AI143447 to PK.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the IACUC of Johns Hopkins University (Protocol Number: MO23H131).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Presented data are provided in the submission supplement. Any other data or materials are available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the staff at JHU Research Animal Resources for their assistance with animal care. We would like to thank the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute and Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology (MMI) and specifically Dr. Prakash Srinivasan for the maintenance and support of the the Attune NxT Flow Cytometer.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCV2 |

SARS-CoV-2 |

| ORF |

Open reading frame |

| MIP3α |

Macrophage-inflammatory protein 3 alpha |

| IM |

Intramuscular |

| IN |

Intranasal |

| KLH |

Keyhole limpet hemocyanin |

| iDC |

Immature dendritic cell |

| IFNγ |

Interferon gamma |

| TNFα |

Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| STING |

Stimulator of interferon genes |

| BAL |

Bronchoalveolar lavage |

References

- COVID (SARS-CoV-2) Vaccine. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567793/ (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- Emergency Use Authorization. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/mcm-legal-regulatory-and-policy-framework/emergency-use-authorization#vaccines (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Zheng, C.; Shao, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, G.; Zhang, W. Real-world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines: a literature review and meta-analysis. International journal of infectious diseases 2022, 114, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Ejikemeuwa, A.; Gerzanich, V.; Nasr, M.; Tang, Q.; Simard, J.M.; Zhao, R.Y. Understanding the Role of SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a in Viral Pathogenesis and COVID-19. Frontiers in microbiology 2022, 13, 854567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Hom, K.; Zhang, C.; Nasr, M.; Gerzanich, V.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Q.; Xue, F.; Simard, J.M.; Zhao, R.Y. SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a Protein as a Therapeutic Target against COVID-19 and Long-Term Post-Infection Effects. Pathogens (Basel) 2024, 13, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, P. The T cell immune response against SARS-CoV-2. Nat Immunol 2022, 23, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardhana, S.; Baldo, L. ; Morice, 2.,William G.; Wherry, E.J. Understanding T cell responses to COVID-19 is essential for informing public health strategies. Science immunology 2022, 7, eabo1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Parkkila, S.; Wu, X.; Aspatwar, A. SARS-CoV-2 variants and COVID-19 vaccines: Current challenges and future strategies. Int Rev Immunol 2023, ahead-of-print. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifoni, A.; Weiskopf, D.; Ramirez, S.I.; Mateus, J.; Dan, J.M.; Moderbacher, C.R.; Rawlings, S.A.; Sutherland, A.; Premkumar, L.; Jadi, R.S.; Marrama, D.; de Silva, A.M.; Frazier, A.; Carlin, A.F.; Greenbaum, J.A.; Peters, B.; Krammer, F.; Smith, D.M.; Crotty, S.; Sette, A. Targets of T Cell Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus in Humans with COVID-19 Disease and Unexposed Individuals. Cell 2020, 181, 1489–1501.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarke, A.; Sidney, J.; Kidd, C.K.; Dan, J.M.; Ramirez, S.I.; Yu, E.D.; Mateus, J.; da Silva Antunes, R.; Moore, E.; Rubiro, P.; Methot, N.; Phillips, E.; Mallal, S.; Frazier, A.; Rawlings, S.A.; Greenbaum, J.A.; Peters, B.; Smith, D.M.; Crotty, S.; Weiskopf, D.; Grifoni, A.; Sette, A. Comprehensive analysis of T cell immunodominance and immunoprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 epitopes in COVID-19 cases. Cell reports.Medicine 2021, 2, 100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, S.K.; Hersby, D.S.; Tamhane, T.; Povlsen, H.R.; Amaya Hernandez, S.P.; Nielsen, M.; Gang, A.O.; Hadrup, S.R. SARS-CoV-2 genome-wide T cell epitope mapping reveals immunodominance and substantial CD8 + T cell activation in COVID-19 patients. Science immunology 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.; Detels, R.; Chang, L.C.; Butch, A.W. Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-3 Alpha (MIP-3alpha)/CCL20 in HIV-1-Infected Individuals. J AIDS Clin Res 2016, 7, 587, Epub 2016 Jun 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutyser, E.; Struyf, S.; Van Damme, J. The CC chemokine CCL20 and its receptor CCR6. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2003, 14, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiavo, R.; Baatar, D.; Olkhanud, P.; Indig, F.E.; Restifo, N.; Taub, D.; Biragyn, A. Chemokine receptor targeting efficiently directs antigens to MHC class I pathways and elicits antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell responses. Blood 2006, 107, 4597–4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biragyn, A.; Ruffini, P.A.; Coscia, M.; Harvey, L.K.; Neelapu, S.S.; Baskar, S.; Wang, J.; Kwak, L.W. Chemokine receptor-mediated delivery directs self-tumor antigen efficiently into the class II processing pathway in vitro and induces protective immunity in vivo. Blood 2004, 104, 1961–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, K.; Zhang, H.; Zavala, F.; Biragyn, A.; Espinosa, D.A.; Markham, R.B.; Kumar, N. Fusion of antigen to a dendritic cell targeting chemokine combined with adjuvant yields a malaria DNA vaccine with enhanced protective capabilities. PloS one 2014, 9, e90413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheinecker, C.; Castellino, F.; Germain, R.N.; Altan-Bonnet, G.; Stoll, S.; Huang, A.Y. Chemokines enhance immunity by guiding naive CD8 + T cells to sites of CD4 + T cell-dendritic cell interaction. Nature 2006, 440, 890–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.H.; Fan, M.W.; Sun, J.H.; Jia, R. Fusion of antigen to chemokine CCL20 or CXCL13 strategy to enhance DNA vaccine potency. Int Immunopharmacol 2009, 9, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodama, S.; Abe, N.; Hirano, T.; Suzuki, M. A single nasal dose of CCL20 chemokine induces dendritic cell recruitment and enhances nontypable Haemophilus influenzae-specific immune responses in the nasal mucosa. Acta Otolaryngol 2011, 131, 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordy, J.T.; Luo, K.; Zhang, H.; Biragyn, A.; Markham, R.B. Fusion of the dendritic cell-targeting chemokine MIP3α to melanoma antigen Gp100 in a therapeutic DNA vaccine significantly enhances immunogenicity and survival in a mouse melanoma model. J Immunother Cancer 2016, 4, 96, Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5168589/ (accessed on Jul 20, 2024). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karanika, S.; Gordy, J.T.; Neupane, P.; Karantanos, T.; Ruelas Castillo, J.; Quijada, D.; Comstock, K.; Sandhu, A.K.; Kapoor, A.R.; Hui, Y.; Ayeh, S.K.; Tasneen, R.; Krug, S.; Danchik, C.; Wang, T.; Schill, C.; Markham, R.B.; Karakousis, P.C. An intranasal stringent response vaccine targeting dendritic cells as a novel adjunctive therapy against tuberculosis. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 972266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, K.; Gordy, J.T.; Zavala, F.; Markham, R.B. A chemokine-fusion vaccine targeting immature dendritic cells elicits elevated antibody responses to malaria sporozoites in infant macaques. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordy, J.T.; Hui, Y.; Schill, C.; Wang, T.; Chen, F.; Fessler, K.; Meza, J.; Li, Y.; Taylor, A.D.; Bates, R.E.; Karakousis, P.C.; Pekosz, A.; Sachithanandham, J.; Li, M.; Karanika, S.; Markham, R.B. A SARS-CoV-2 RBD vaccine fused to the chemokine MIP-3α elicits sustained murine antibody responses over 12 months and enhanced lung T-cell responses. Frontiers in Immunology 2024, 15, Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1292059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, P.; Yanik, S.; Venkatesh, V.; Gordy, J.; Alameh, M.; Meza, J.; Li, Y.; Glass, E.; Flores-Garcia, Y.; Tam, Y.; Chaiyawong, N.; Sarkar, D.; Weissman, D.; Markham, R. Immature dendritic cell-targeting mRNA vaccine expressing PfCSP enhances protective immune responses against Plasmodium liver infection. 2024. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-4656309/v1 (accessed on Jul 30, 2024). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollefsen, S.; Vordermeier, M.; Olsen, I.; Storset, A.K.; Reitan, L.J.; Clifford, D.; Lowrie, D.B.; Wiker, H.G.; Huygen, K.; Hewinson, G.; Mathiesen, I.; Tjelle, T.E. DNA Injection in Combination with Electroporation: a Novel Method for Vaccination of Farmed Ruminants. Scand J Immunol 2003, 57, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babiuk, S.; Baca-Estrada, M.; Foldvari, M.; Middleton, D.M.; Rabussay, D.; Widera, G.; Babiuk, L.A. Increased gene expression and inflammatory cell infiltration caused by electroporation are both important for improving the efficacy of DNA vaccines. J Biotechnol 2004, 110, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlen, G.; Soderholm, J.; Tjelle, T.; Kjeken, R.; Frelin, L.; Hoglund, U.; Blomberg, P.; Fons, M.; Mathiesen, I.; Sallberg, M. In Vivo Electroporation Enhances the Immunogenicity of Hepatitis C Virus Nonstructural 3/4A DNA by Increased Local DNA Uptake, Protein Expression, Inflammation, and Infiltration of CD3+ T Cells. The Journal of immunology (1950) 2007, 179, 4741–4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JINYAN, L.I.U.; KJEKEN, R.; MATHIESEN, I.; BAROUCH, D.H. Recruitment of Antigen-Presenting Cells to the Site of Inoculation and Augmentation of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 DNA Vaccine Immunogenicity by In Vivo Electroporation. J Virol 2008, 82, 5643–5649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Guo, Z.; Yang, H.; Peng, L.; Xie, Y.; Wong, T.; Lai, S.; Guo, Z. Amino terminus of the SARS coronavirus protein 3a elicits strong, potentially protective humoral responses in infected patients. J Gen Virol 2006, 87, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Åkerström, S.; Tan, Y.; Mirazimi, A. Amino acids 15–28 in the ectodomain of SARS coronavirus 3a protein induces neutralizing antibodies. FEBS Lett 2006, 580, 3799–3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Tao, L.; Wang, T.; Zheng, Z.; Li, B.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Wang, H. Humoral and Cellular Immune Responses Induced by 3a DNA Vaccines against Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) or SARS-Like Coronavirus in Mice. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology 2009, 16, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Xia, H.; Zou, J.; Muruato, A.E.; Periasamy, S.; Kurhade, C.; Plante, J.A.; Bopp, N.E.; Kalveram, B.; Bukreyev, A.; Ren, P.; Wang, T.; Menachery, V.D.; Plante, K.S.; Xie, X.; Weaver, S.C.; Shi, P. A live-attenuated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidate with accessory protein deletions. Nature communications 2022, 13, 4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, M.E.; Xue, Y.; Dillen, C.; Oldfield, L.; Assad-Garcia, N.; Zaveri, J.; Singh, N.; Baracco, L.; Taylor, L.J.; Vashee, S.; Frieman, M.B. SARS-CoV-2 variant spike and accessory gene mutations alter pathogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences - PNAS 2022, 119, e2204717119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; Wu, R.; Shen, M.; Huang, J.; Li, T.; Hu, C.; Luo, F.; Song, S.; Mu, S.; Hao, Y.; Han, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Li, S.; Chen, Q.; Wang, W.; Jin, A. Extended SARS-CoV-2 RBD booster vaccination induces humoral and cellular immune tolerance in mice. iScience 2022, 25, 105479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Then, E.; Lucas, C.; Monteiro, V.S.; Miric, M.; Brache, V.; Cochon, L.; Vogels, C.B.F.; Malik, A.A.; De la Cruz, E.; Jorge, A.; De los Santos, M.; Leon, P.; Breban, M.I.; Billig, K.; Yildirim, I.; Pearson, C.; Downing, R.; Gagnon, E.; Muyombwe, A.; Razeq, J.; Campbell, M.; Ko, A.I.; Omer, S.B.; Grubaugh, N.D.; Vermund, S.H.; Iwasaki, A. Neutralizing antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron variants following heterologous CoronaVac plus BNT162b2 booster vaccination. Nat Med 2022, 28, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ploeg, K.; Kirosingh, A.S.; Mori, D.A.M.; Chakraborty, S.; Hu, Z.; Sievers, B.L.; Jacobson, K.B.; Bonilla, H.; Parsonnet, J.; Andrews, J.R.; Press, K.D.; Ty, M.C.; Ruiz-Betancourt, D.; de la Parte, L.; Tan, G.S.; Blish, C.A.; Takahashi, S.; Rodriguez-Barraquer, I.; Greenhouse, B.; Singh, U.; Wang, T.T.; Jagannathan, P. TNF-α+ CD4+ T cells dominate the SARS-CoV-2 specific T cell response in COVID-19 outpatients and are associated with durable antibodies. Cell reports.Medicine 2022, 3, 100640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.R.; Markl, J. Keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH): a biomedical review. Micron 1999, 30, 597–623, Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0968432899000360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wherry, E.J.; Barouch, D.H. T cell immunity to COVID-19 vaccines. Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science) 2022, 377, 821–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chandrashekar, A.; Sellers, D.; Barrett, J.; Jacob-Dolan, C.; Lifton, M.; McMahan, K.; Sciacca, M.; VanWyk, H.; Wu, C.; Yu, J.; Collier, A.Y.; Barouch, D.H. Vaccines elicit highly conserved cellular immunity to SARS-CoV-2 Omicron. Nature 2022, 603, 493–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadfield, J.; Megill, C.; Bell, S.M.; Huddleston, J.; Potter, B.; Callender, C.; Sagulenko, P.; Bedford, T.; Neher, R.A. Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagulenko, P.; Puller, V.; Neher, R.A. TreeTime: Maximum-likelihood phylodynamic analysis. Virus Evol 2018, 4, vex042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).