1. Introduction

The study and understanding of active tectonics provide the scientific community with information on the movement of Earth’s plates. In this way, the monitoring of Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) signals through geodetic receivers in permanent monuments is the most accurate technique for the study and analysis of ground deformations in these hard-to-reach areas.

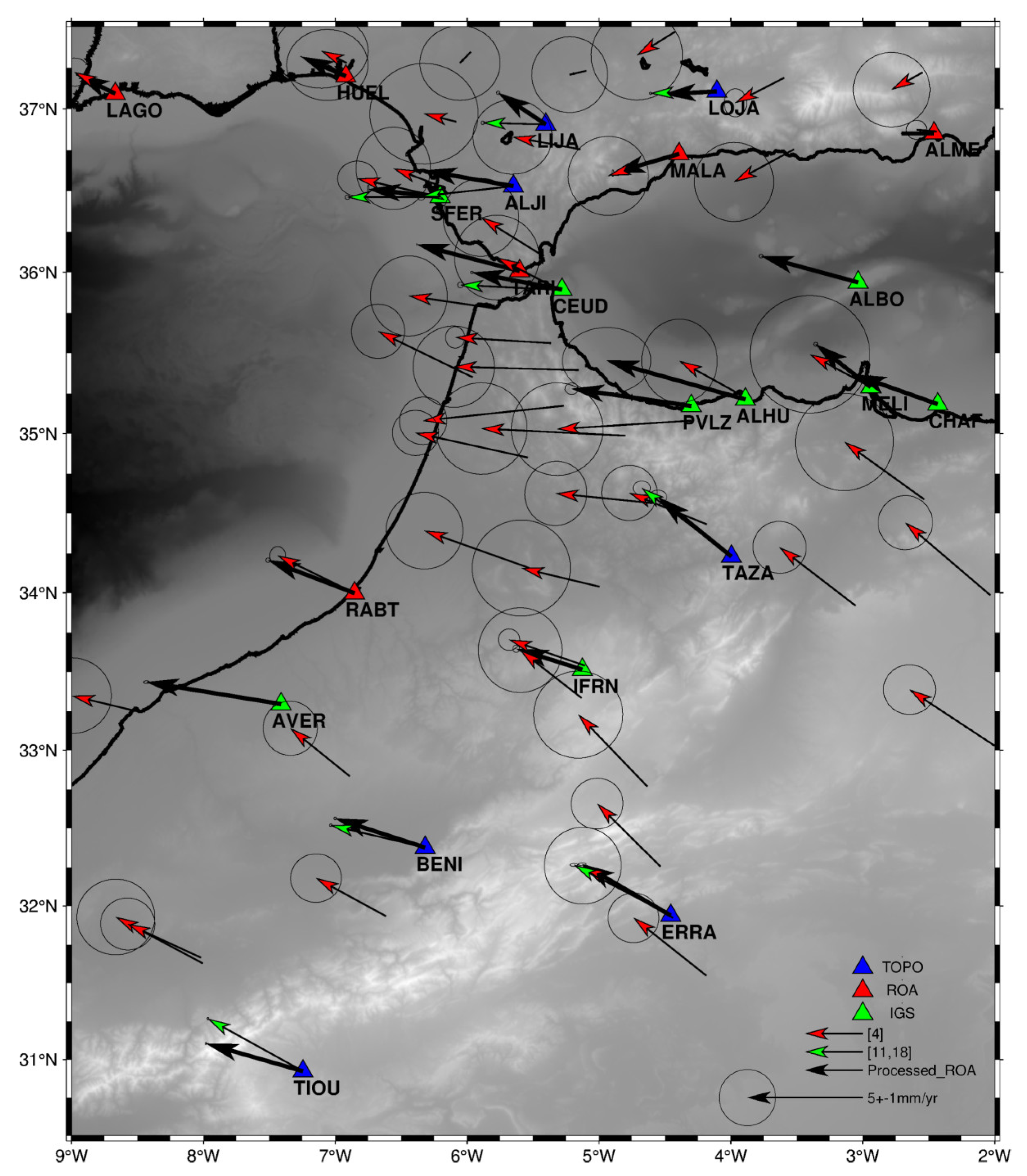

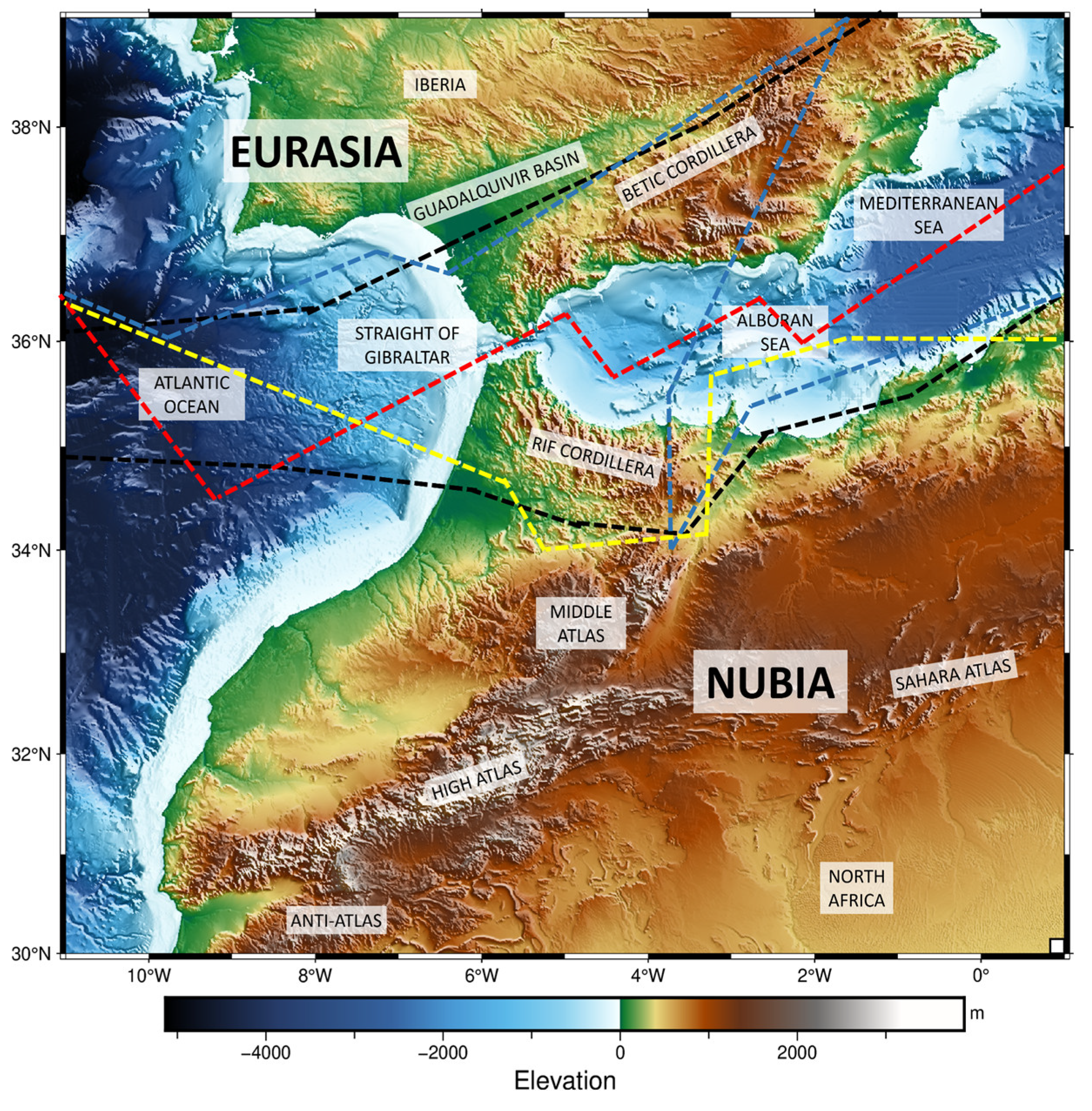

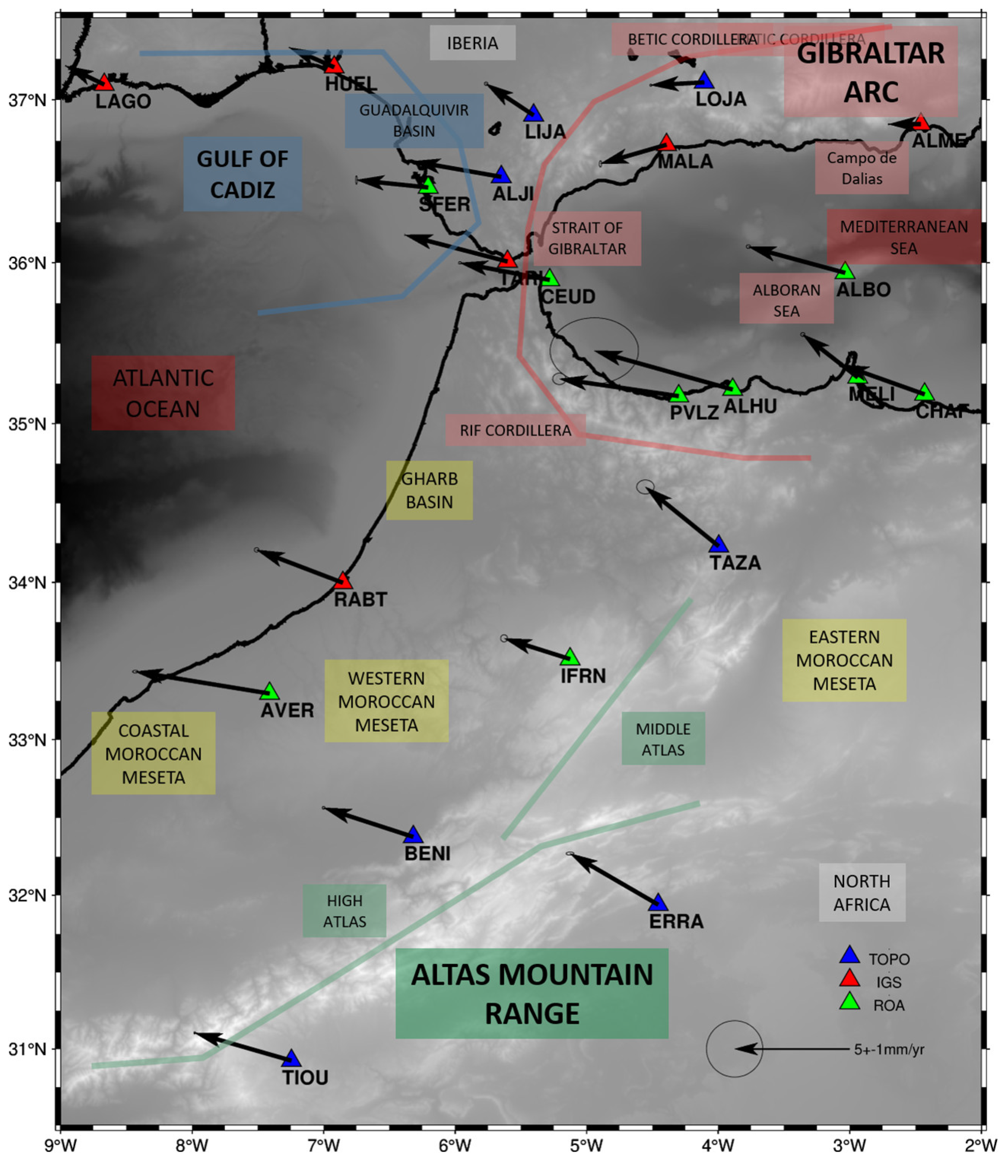

The Eurasia-Nubian plate convergence zone is an area of great interest due to its high geodynamic activity. The Strait of Gibraltar, the Alboran Sea domain, the Maghrebides or the Betic Cordilleras are clear examples of this complex structure (

Figure 1). This area is a North-South convergence zone of diffuse tectonics between the African and Eurasian Plates whose limit is still under discussion [

1]. Currently, the convergence between both plates is evolving in a NW-SE direction with an approximate rate of 4-5 millimeters per year [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

The most updated studies in the GNSS field in this region, mainly in North Africa, include campaigns with data from continuous stations up to 2014, such as those presented in the TopoIberia project [

10]. The rest of the studies have been carried out with episodic campaigns as for example [

2,

4,

16,

17], which could present significant drawbacks compared to continuous stations, mainly in the lack of data continuity, lower precision, and inability to monitor short-term phenomena or provide real-time data.

Within the confluence zone of EURA-NUBIA, the active region between the Betics Mountain range and the northern Alboran Sea has been well defined by several studies that explain the tectonic behavior [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Those studies show in general that the velocity field in the Iberian Peninsula from the north of Betics mountain range forms part of the stable Eurasian plate, with a residual movement between 2-3 millimeters per year. Because of these exhaustive scientific studies, the deformation patterns and geodynamics of this area of the Gibraltar Arc are quite well established in areas of interest such as the Campo de Dalias [

16], Granada Basin [

21] or the eastern shear zone of the Betics Cordillera [

20,

22]. On the other part, in Morocco, while the Rif can be considered within this diffuse zone, the Atlas mountain range is already at the limit within the North African plate according to recent studies in this region [

10,

18,

24,

25,

26]. Furthermore, the stresses between plates are not accommodated in the same way, with the North African contact zone being the most active [

19,

20]. This shows a clear example of a complex incidence model that makes it possible to accommodate deformations.

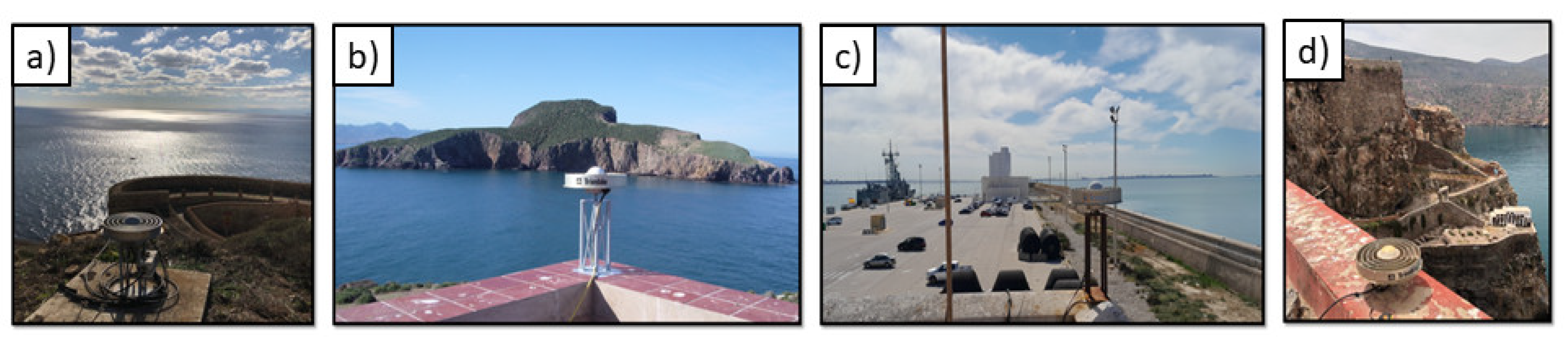

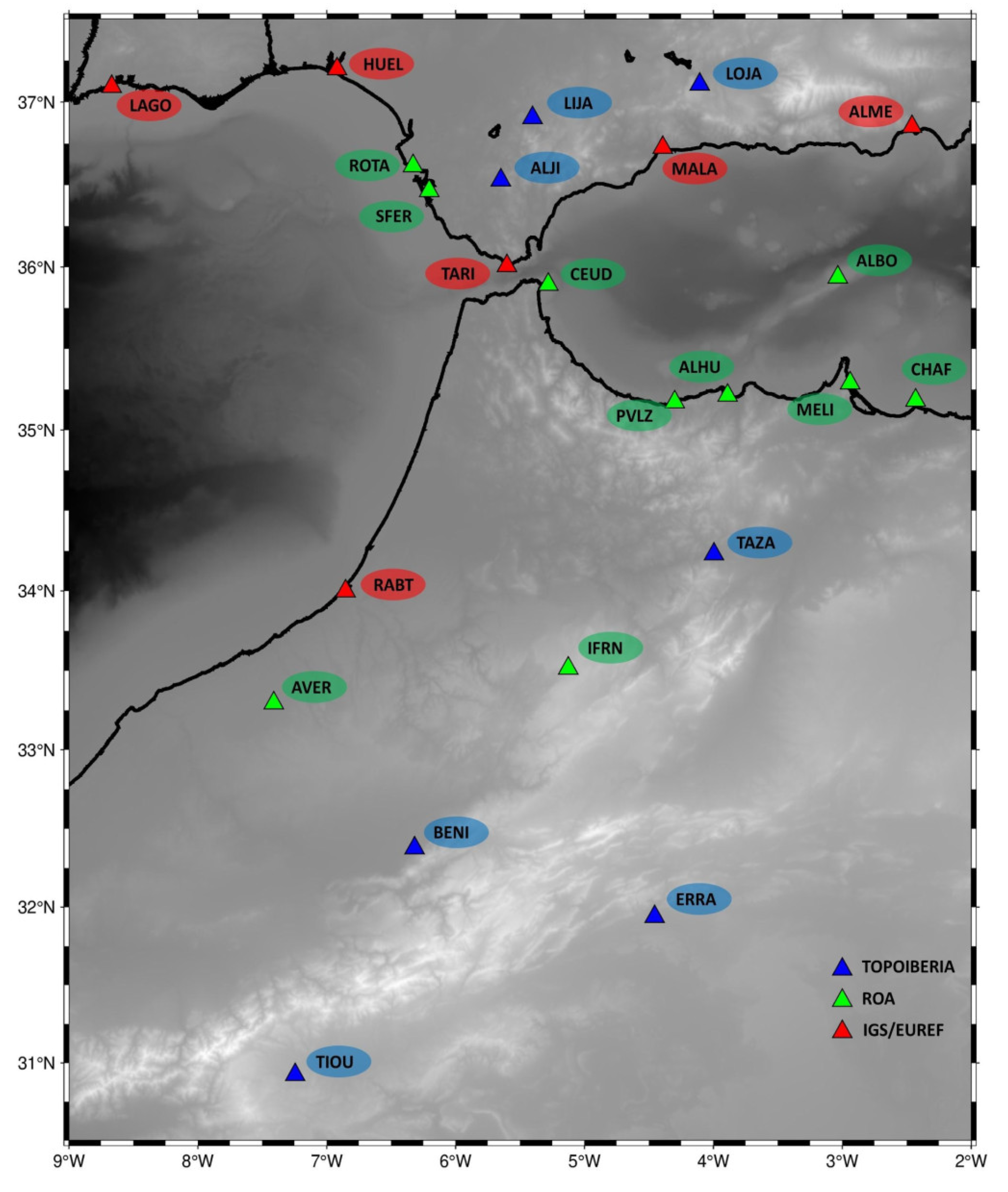

The Royal Institute and Observatory of the Spanish Navy (ROA) is currently committed to maintaining continuous GNSS stations in the South of Spain and North Africa. For this purpose, precise geodetic devices were installed in strategic and interesting points as seen in

Figure 2. In addition, the maintenance of its own station inherited from the TopoIberia Project [

27], of which only Tiouine (Station of TIOU) is preserved. At present, there are no other continuous GNSS networks in this interesting area of study. The interpretation of the data processed can add useful information to clarify the behavior of this confusing and poorly monitored region, as well as complementing several previous studies, such as those cited above.

The objective of this paper is to present a new velocity field calculated from continuous GNSS stations located in southern Spain and North Africa. This velocity field includes for the first time CGNSS data from CEUD, PVLZ, ALHU, ALBO, MELI, CHAF and AVER; but also complemented with the continuity of the data that have not yet been published, TIOU, LIJA, ALJI, LOJA and IFRN (

Figure 2). These stations belong to the ROA.

2. GNSS Stations and Data Processing

2.1. General Description of the Emplacements

The GNSS stations of the ROA have been installed at the different sites for more than 20 years, some through completed collaborative projects and others on the own initiative of the staff of the geophysics section. The main characteristics of the equipment and current status of these stations are summarized in

Table 1, they are listed below in alphabetical order. For the stations belonging to IGS, the considered period ranges from the installation of the station to 2024/06/16. Station belonging to TopoIberia has observations from 2008 to 2014/02/02, the end of the research project [

11]. The stations belonging to the ROA, along with those inherited from TopoIberia, do not have the same period of data since they were installed at different times and some have had technical problems. In any case, all stations except ALHU have more than five years of data. Most have more than 10 years of data.

As can be observed, several of these continuous GNSS station sites exhibit a series of constraints that render them challenging to exploit. Power supply, vandalism, or weather conditions add to the difficult access in some cases, making the maintenance and monitoring of these sites a daunting task. Therefore, to keep this type of station up to date, it is necessary to have the necessary infrastructure and good associated logistics. This means that the stations are exposed to periods of maintenance or failures that make it difficult for them to operate continuously. Communications also play a key role as real-time service is required. In stations where there is no internet network connection, satellite communications or multi-operator modems have been installed, so that it is possible to access the equipment remotely. Due to the circumstances described above, all installed equipment must be robust and energy-efficient, so as to ensure the reliability of the station over a long period of time.

Figure 3.

Some of the continuous stations belonging to the ROA. a) CEUD (Desnarigado Castle in Ceuta), b) CHAF (Isabel II Island Lighthouse in the Chafarinas Archipelago), c) ROTA (Rota Naval Base Dock) and d) PVLZ (Vélez de la Gomera Rock Lighthouse).

Figure 3.

Some of the continuous stations belonging to the ROA. a) CEUD (Desnarigado Castle in Ceuta), b) CHAF (Isabel II Island Lighthouse in the Chafarinas Archipelago), c) ROTA (Rota Naval Base Dock) and d) PVLZ (Vélez de la Gomera Rock Lighthouse).

2.2. Methodology Employed

A Station log has been created for each station, documenting the maintenance activities carried out at the various sites as well as the instrumentation changes over the years. Data processing was performed with PRIDE-PPPAR (Precise Point Positioning with Ambiguity Resolution) software [

28], which was used to obtain the daily time series. This program allows us to obtain coordinate files, starting from the RINEX files of the observations with 30-second sampling intervals every 24 hours. The observation period for every station is shown in

Table 1. Daily position files are converted into an annual series of positions, in which we obtain the displacements that have occurred since the beginning of our time series. The data were processed using the PPP (Precise Point Positioning) technique [

29]. The final combined solutions products (ephemeris, clock files and Earth Rotation Parameters) used correspond to those provided by the IGS Central Office and the IGS Reference Framework Coordinator for the 3rd IGS reprocessing campaign land frame (repro3) [

30], which form the IGS contribution to the ITRF2020 [

31]. An ionosphere-free combination was used along with the application of High Order Ionosphere corrections. For the ZTD estimation, the Saastamoinen model [

32] was used and for troposphere mapping every hour, the Global Mapping Function was selected [

33]. The tidal model was calculated using [

34], which refers to the FES2014 tidal model [

35]. The LAMBDA (Least-squares Ambiguity Decorrelation Adjustment) method [

36] has been used for the resolution of ambiguities.

SARI [

37] is a software that allows users to visualize different formats of discrete time series data, and also to process and analyze the series individually, fit unidimensional models and finally save the results. Coordinated time series of the stations were uploaded directly from the servers of the different GNSS data web servers (EUREF, IGS…) [

38,

39] if they were available, although they have also been processed by PRIDE-PPPAR for verification of results. In our case, we enter a file in PBO format (ASCII file with .pos extension), where it is possible to remove outliers with residual threshold or manually. We were able to upload complementary information for the purpose of the GNSS signal analysis, it was used to incorporate the site logs of the stations and to introduce the predefined plate motion model which refers to [

40]. For model fitting, the least squares (LS) option was used [

41]. From among the options, the linear trend is introduced, the discontinuities detected in the series by defining the reference epochs, and the periodic signals with a reference epoch that is the average of the available measurement data, where the phase values are estimated accordingly. For velocity verification with SARI, the Median Interannual Difference Adjusted for Skewness (MIDAS) algorithm [

42] has been used. An analysis of noise is performed to estimate the complete variance-covariance matrix that optimally characterizes the model or filter residuals as a Gaussian process, using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) to determine the parameters of a selected covariance model.

The data have been represented in Python [

43] thanks to PyGMT library (Python interface for the Generic Mapping Tools) [

44]. The final strain-stress results have been obtained with the algorithm Optimal Interpolation of Spatially Discretized Geodetic Data [

45] from the previously calculated GNSS velocities. The Global Multi-Resolution Topography (GMRT) Synthesis databases have been used to represent the topography of the maps [

12].

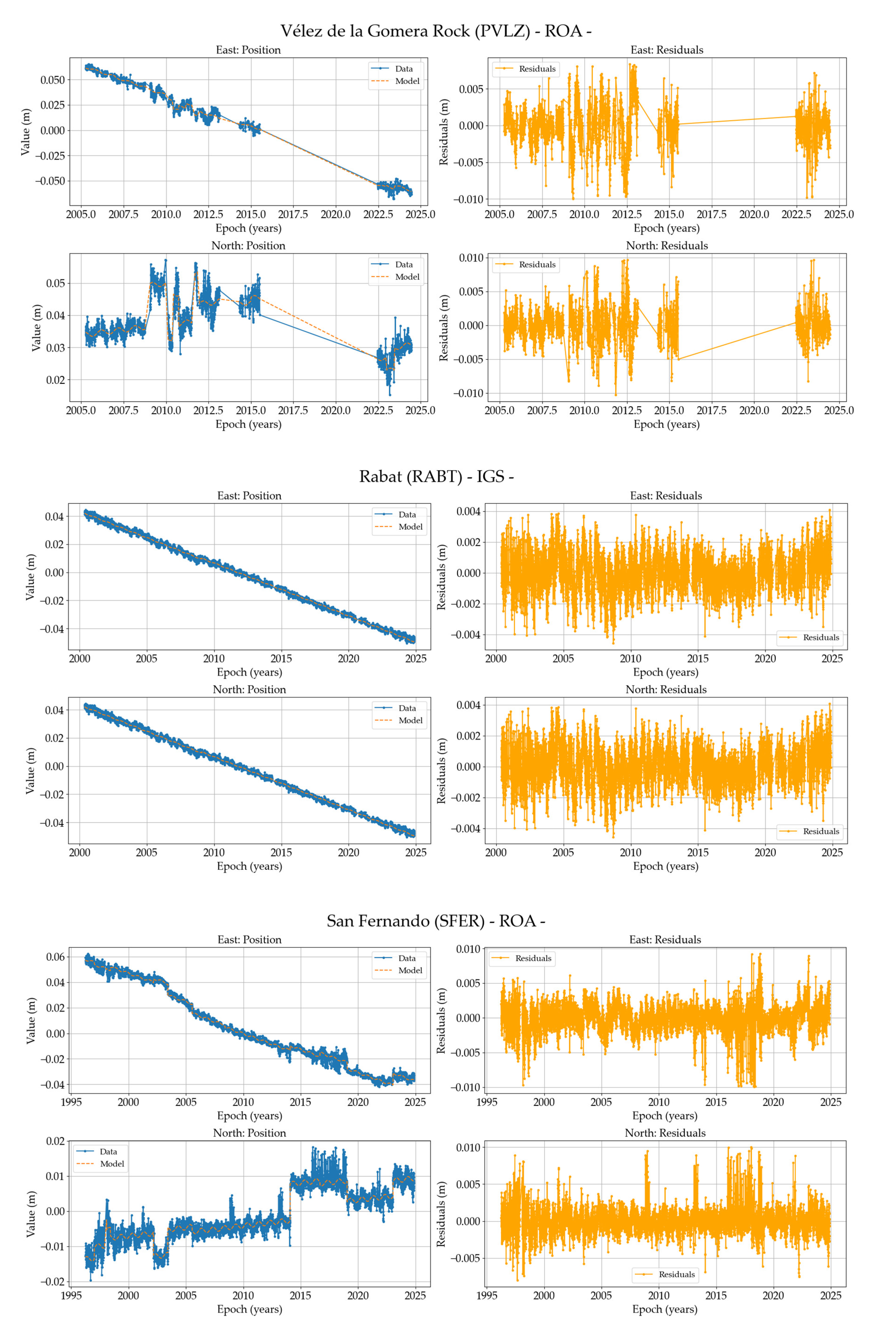

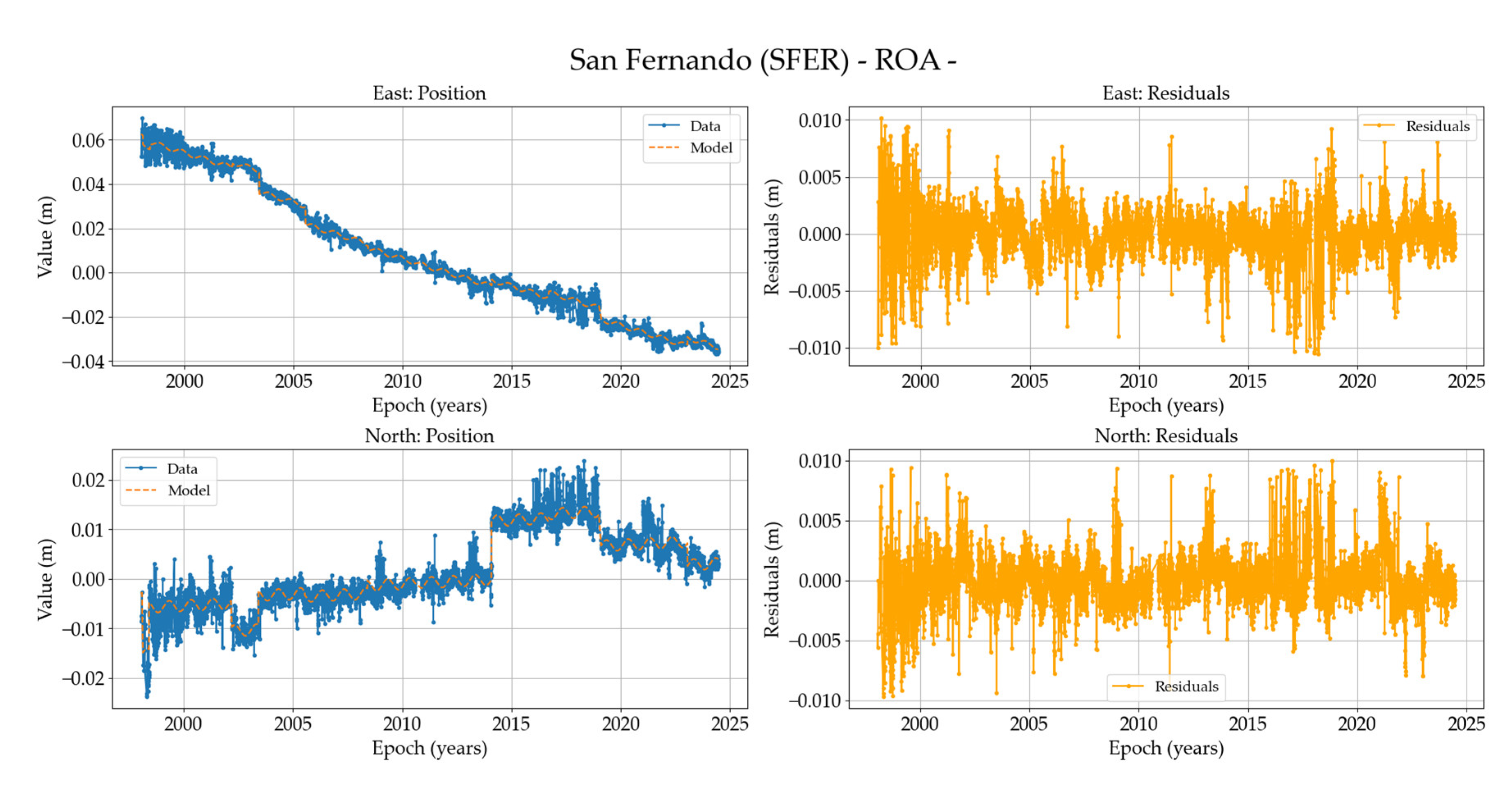

3. GNSS Network Results

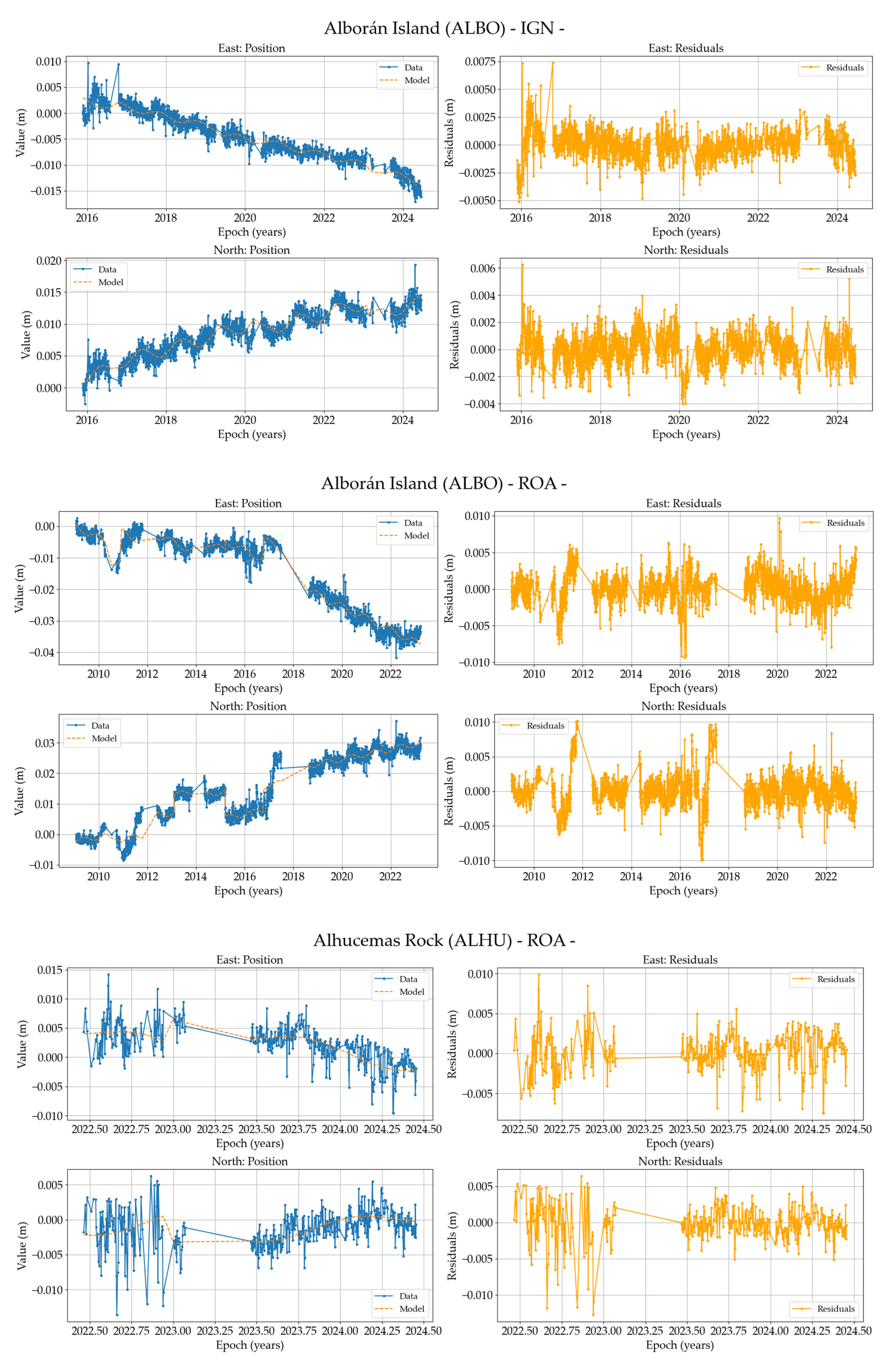

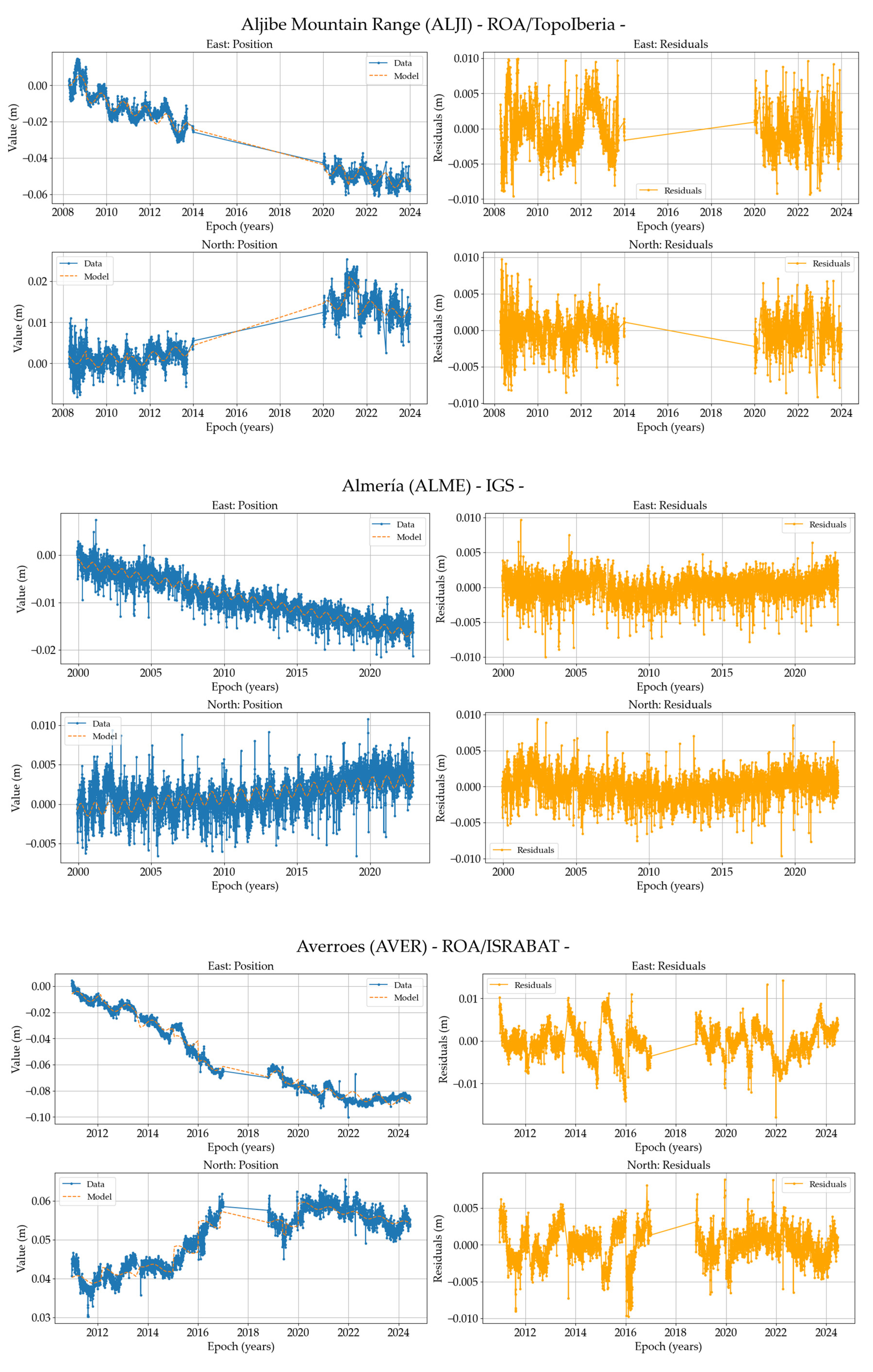

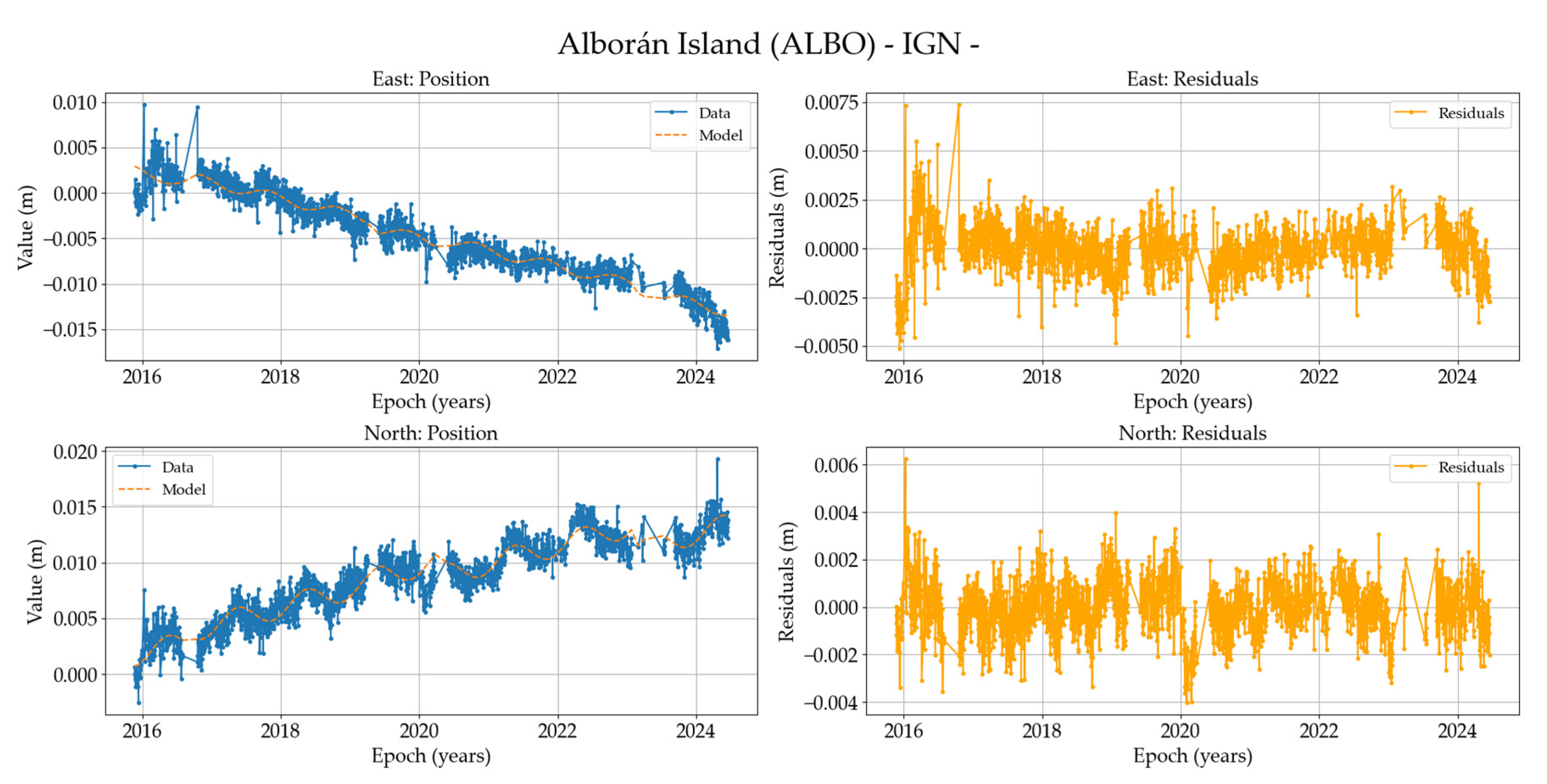

The final results can be visualized as a 2D time series in East and North coordinates in the

Appendix A, where values are expressed in meters.

Figure 4 shows the time series of ALBO in its horizontal coordinates (east and north) as an example of the content in

Appendix A.

Analyzing the time series from

Figure 4, most exhibit a standard behavior; however, we will discuss those that may present any notable details. Some of the stations such as ALJI, BENI, ERRA, LIJA, LOJA, TAZA and TIOU have already been exploited by other authors; the new feature is that to the 4 years studied, for example in the case of TIOU, 10 more years of uninterrupted data have been added. ALHU is the newest station with two years of data collection; the abrupt change in result dispersion is due to an instrumentation upgrade to a higher-performance model. ALJI experienced a period of inactivity following the TopoIberia project; however, once reactivated and analyzed, the time series shows stability and validity, maintaining the trend observed previously. LIJA and LOJA have experienced communication issues but currently have real-time data available. Lastly, in TARI, there was a slight change in the antenna position, but the time series appears to remain completely stable.

Table 2.

Information of the stations: Displacement velocity w.r.t IGb20 in mm/yr and its standard deviation in mm/yr, displacement velocity w.r.t EURA and its standard deviation in mm/yr. Additionally, we have introduced the results using MIDAS to enable comparison with LS (For simplification, they have only been provided w.r.t. EURA. The ALHU period is too short to be processed).

Table 2.

Information of the stations: Displacement velocity w.r.t IGb20 in mm/yr and its standard deviation in mm/yr, displacement velocity w.r.t EURA and its standard deviation in mm/yr. Additionally, we have introduced the results using MIDAS to enable comparison with LS (For simplification, they have only been provided w.r.t. EURA. The ALHU period is too short to be processed).

| Station |

Total Vel (mm/year) |

SD (mm/year) |

EURA Vel (mm/year) |

SD (mm/year) |

| East |

North |

East |

North |

| East |

North |

East |

North |

LS |

MIDAS |

LS |

MIDAS |

LS |

MIDAS |

LS |

MIDAS |

| ALBO ROA |

16.14 |

17.69 |

±0.03 |

±0.03 |

-4.20 |

-4.33 |

1.14 |

1.12 |

±0.04 |

±0.17 |

±0.03 |

±0.13 |

| ALBO IGN |

18.09 |

17.80 |

±0.03 |

±0.03 |

-2.43 |

-2.40 |

1.34 |

1.25 |

±0.03 |

±0.21 |

±0.03 |

±0.16 |

| ALHU |

14.69 |

15.22 |

±0.20 |

±0.20 |

-6.01 |

- |

1.68 |

- |

±0.787 |

- |

±0.58 |

- |

| ALJI |

16.19 |

17.67 |

±0.03 |

±0.03 |

-3.86 |

-4.45 |

0.68 |

0.71 |

±0.03 |

±0.55 |

±0.01 |

±0.31 |

| ALME |

18.81 |

16.64 |

±0.02 |

±0.02 |

-1.39 |

-1.25 |

-0.01 |

-0.01 |

±0.02 |

±0.02 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

| AVER |

14.71 |

16.57 |

±0.08 |

±0.08 |

-5.83 |

-5.59 |

-0.95 |

-1.31 |

±0.05 |

±0.41 |

±0.02 |

±0.19 |

| BENI |

16.62 |

17.94 |

±0.02 |

±0.02 |

-3.89 |

-3.96 |

1.27 |

1.09 |

±0.02 |

±0.15 |

±0.02 |

±0.17 |

| CEUD |

15.83 |

16.94 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

-3.90 |

-4.17 |

0.74 |

0.51 |

±0.02 |

±0.26 |

±0.02 |

±0.17 |

| CHAF |

16.91 |

18.02 |

±0.09 |

±0.09 |

-3.63 |

-3.82 |

1.49 |

1.79 |

±0.03 |

±0.14 |

±0.04 |

±0.18 |

| ERRA |

15.76 |

18.91 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

-3.83 |

-4.01 |

2.22 |

2.13 |

±0.01 |

±0.15 |

±0.01 |

±0.16 |

| HUEL |

17.55 |

17.51 |

±0.02 |

±0.02 |

-1.94 |

-1.90 |

0.90 |

0.89 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

| IFRN |

17.60 |

17.54 |

±0.06 |

±0.06 |

-2.87 |

-2.73 |

0.94 |

1.18 |

±0.06 |

±0.22 |

±0.06 |

±0.20 |

| LAGO |

17.42 |

17.41 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

-1.67 |

-1.60 |

0.81 |

0.79 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

| LIJA |

17.62 |

17.97 |

±0.02 |

±0.02 |

-2.07 |

-2.26 |

1.37 |

0.92 |

±0.03 |

±0.19 |

±0.03 |

±0.21 |

| LOJA |

17.53 |

16.43 |

±0.01 |

±0.02 |

-2.32 |

-2.29 |

-0.13 |

-0.22 |

±0.02 |

±0.14 |

±0.01 |

±0.19 |

| MALA |

17.13 |

1.94 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

-2.87 |

-2.78 |

-0.83 |

-0.80 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

| MELI ROA |

18.04 |

18.41 |

±0.03 |

±0.03 |

-2.39 |

-2.91 |

1.86 |

2.04 |

±0.04 |

±0.18 |

±0.03 |

±0.15 |

| MELI IGN |

17.46 |

18.76 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

-2.89 |

-2.93 |

1.65 |

1.86 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

| PVLZ |

15.06 |

17.34 |

±0.10 |

±0.10 |

-5.19 |

-5.70 |

0.75 |

0.98 |

±0.11 |

±0.22 |

±0.10 |

±0.23 |

| RABT |

16.38 |

18.04 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

-3.75 |

-3.68 |

1.43 |

1.40 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

| ROTA |

18.27 |

19.64 |

±0.34 |

±0.34 |

-2.38 |

-1.85 |

2.22 |

-1.60 |

±0.04 |

±0.60 |

±0.04 |

±0.22 |

| SFER |

16.55 |

16.98 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

-3.12 |

-3.29 |

0.32 |

0.43 |

±0.01 |

±0.07 |

±0.01 |

0.06 |

| TARI |

15.83 |

18.04 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

-4.46 |

-4.32 |

1.16 |

1.10 |

±0.001 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

±0.01 |

| TAZA |

17.31 |

19.17 |

±0.11 |

±0.10 |

-3.18 |

-2.91 |

2.58 |

1.88 |

±0.02 |

±0.39 |

±0.01 |

0.36 |

| TIOU |

16.48 |

17.93 |

±0.14 |

±0.14 |

-4.20 |

-4.27 |

1.21 |

1.13 |

±0.01 |

±0.09 |

±0.01 |

±0.11 |

The time series from Alborán Island, where the IGN and ROA stations are located, have also been compared. Given that the IGN station exhibits better stability, we have chosen to use it for the final results, even though both stations display fairly similar behavior. In Melilla, encountering a similar situation, we proceeded to compare both stations. However, in this case, the time series are virtually identical even though the IGN time series was affected by the 2016 earthquake, and we opted to use the ROA station. An initial assessment suggests that if a highly noisy environment or complex errors were present, processing with MIDAS would offer significant advantages over least squares. However, the results obtained indicate that this is not the case, as the final values are very similar. The differences found when comparing LS with MIDAS are within the range of tenths of a millimetre, which is consistent with results published in [

42]. Additionally, to verify PPP processing with PRIDE, the final results of the IGS stations have been cross-checked using SARI, obtaining satisfactory results across all stations confirming publications such as [

46].

Table 3 shows the results obtained in SFER as an example.

According to Apendix A, the velocities w.r.t. EURA have been plotted in

Figure 5. Additionally, the stress tensors produced by these deformations at each point have been represented in

Figure 6.

Regarding the observed annual deformations, three distinct behavior domains are identified, though all exhibit a predominant WNW motion. The first block could comprise the stations of LAGO, HUEL and LIJA, located in the Gulf of Cádiz region in the southwestern Iberian Peninsula. In this area, it is evident that as the stations get closer to the Strait of Gibraltar, their residual velocity relative to the fixed Eurasian block increases, with the maximum recorded at LIJA exceeding 2 mm per year. The next tectonic group is known as the Gibraltar Arc, encompassing the Betic Cordillera up to SFER, the Alboran Sea, and northern Morocco, extending from the Rif to CHAF. In the Spanish sector, the data indicate a consistent westward motion of the Betic Cordillera with respect to the relatively stable Iberian Massif block. Displacement rates progressively increase toward the south and west, reaching maximum values in the Gibraltar Strait region (SFER, TARI and CEUD with velocities ranging between 3.5 and 4.5 mm/yr,), before gradually decreasing toward the northwestern mountain front (ALJI and ALME showing displacements between 1 and 2 mm/yr). Additionally, the dynamics in North Africa and the Alboran Sea follow a similar pattern to that observed in the Strait region. However, a small anomaly is noted at MELI to the north, where displacement rates more closely resemble those observed at TAZA in the Atlas Mountains. The ROA time series extends until 2015, but the IGN time series, which includes 2016, captures the earthquake that occurred in the Alboran Sea and affected the city of Melilla. The post-seismic period has been included in the processing of MELI. This displacement pattern aligns with the clockwise rotation of tectonic units within the Gibraltar Arc sector. The final domain is composed of the Moroccan Meseta and the Atlas Mountains. Here a collective northwestward motion is observed, with velocities ranging between 4.5 and 3 mm/yr. There may be a differentiation in behavior among the stations more aligned with the Atlas Mountains domain (TIOU, BENI, IFRN, and RABT), with the station AVER located on the Western Moroccan Meseta showing a slight eastward shift and an increase in velocity (5 mm/yr). This deformation observed at the AVER station, which generates an extension relative to the other stations in Morocco, requires further investigation; the results for this area must remain on hold. The time series from the Averroes station suggests a possible subsidence of the terrain that must be considered in detail. TAZA, located in the Middle Atlas, exhibits a rotation toward the NNW as previously noted, while ERRA, situated within the more stable portion of the NUBIA plate, displays a distinct pattern.

In

Figure 6, the stress tensors at each point derived from these residual velocities are also displayed. Overall, it is evident that the region exhibits a continuously evolving plate collision regime with a dominant oblique horizontal compressional trend, following a NW-SE direction. The displacement is better seen in

Figure 5 with respect to stable Eurasia. In

Figure 6, it is observed mainly in the center-east of Alboran and Rif. Along the southwestern coast of the Iberian Peninsula it is variable in the Gulf of Cadiz; as a result, there appear to be small arrows of NW-SE extension towards the N part of the Gulf and ENE-WSW compression towards the central zone. Between AlJI and LIJA there is almost an N-S extension. The ENE-WSW compression in the Gulf of Cadiz is straightforward to interpret, as it likely corresponds to the westward thrusting of the Gibraltar Arc. In contrast, in the Gibraltar Strait the stress components rotate clockwise, showing more pronounced NW-SE compression and SW-NE extension. In the westernmost area, the behavior is similar to that of the rest of the Alboran Sea. The maximum stress values are observed in the eastern Rif region and in the Betics between LIJA and ALJI. A greater challenge arises between Rabat and the Rif, where NE-SW extension is observed due to the Gharb Basin, presumably aligning with the advancing direction of the mountain front. However, the issue likely stems from the lack of continuous stations in the area. The intense deformation around AVER station depicts an additional consideration on its stability because it is built on thick, poorly consolidated sediments and the apparent NE-SW extensional trends may be a consequence of local subsidence.

In

Figure 7, rotations and shear stresses affecting the points are shown, based on the deformations introduced in

Table 2. The image highlights that the most extreme values are concentrated in the Gibraltar Arc region, where counterclockwise (red) rotations are observed dominate in the Betics and Gibraltar Strait, while clockwise (blue) rotations are more evident in the Rif. This suggests strong tectonic activity of the Gibraltar Arc that is localized in highly deformed areas.

4. Discussion

From a global perspective, analyzing these preliminary results provides insight into the motion between the EURA and NUBIA plates. It is possible to observe, based on the velocities of the GNSS stations located in the more tectonically stable areas of Ibero-Magrebi (LAGO and HUEL in EURA plate and TIOU and ERRA in NUBIA plate), that there is indeed a convergence in the NW-SE direction at a rate of approximately 4.5 mm/yr tending with clockwise rotation to N-S. This observation is consistent with previous studies referenced [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Furthermore, a perpendicular heterogeneous extension in the ENE-WSW direction is associated with the previously-mentioned convergence. As a consequence, there are regions where compressional shortening is primarily observed, while in others extensional deformation predominates. This corroborates findings from several studies, such as [

2,

14,

39,

40]. It is true that, when compared with previous studies, it is important to consider that these were conducted in earlier reference frames [

48,

49], which could introduce a slight displacement; however, given the localized and nearby areas, this effect should be minimal.

To accurately compare the new insights provided by the analysis of the network used with previous studies in this region,

Figure 7 displays the velocities relative to EURA from the most representative prior research, including [

4,

10,

18].

Focusing a little more on the different blocks described in the results, the stations in the southwestern Iberian Peninsula exhibit similar results; these measurements consistently show a westward motion of the Betic Cordillera relative to the more stable Iberian Peninsula which is consistent with previous studies [

2,

4,

10,

18,

50]. However, there are no stations close to LIJA, which shows discrepancies compared to the analyses in [

10], presenting a pronounced turn to the north. This may be attributed to the availability of longer time series. Both stations exhibit very similar dynamics in both velocity and direction, which also occurs with LAGO or HUEL, although with lower magnitude. However, at SFER, the displacement is comparable to that observed at other stations in the Strait of Gibraltar and North Africa. LIJA may be highlighting part of the boundary of the diffuse convergence zone between the EURA and NUBIA plates which could cross along the Guadalquivir Basin.

Figure 7.

Overview of the confluence zone of North Africa and the southern Iberian Peninsula. The residual velocities w.r.t. EURA (scale 5mm/year) of continuous and episodic stations used for the study are plotted. In black stations included in the study, in red [

4] and in green [

11,

18].

Figure 7.

Overview of the confluence zone of North Africa and the southern Iberian Peninsula. The residual velocities w.r.t. EURA (scale 5mm/year) of continuous and episodic stations used for the study are plotted. In black stations included in the study, in red [

4] and in green [

11,

18].

No further details will be provided on the results from the eastern Betics, as the ROA only has the LOJA station in Granada. The aim is simply to corroborate previous results and the already analyzed behavior of this station by extending the time series for LOJA and ALBO as well as MALA and ALME, for the study of the region. This area is under continuous analysis due to its high interest, given its constant tectonic and seismic activity. As our data align with previous findings, we will reference various studies as benchmarks for understanding its behavior. [

16,

17,

53] presents the recent behavior of NE-SW in the middle of the Betic Cordillera, verifying the results. Further south, as observed in the Campo de Dalías [

11], a geological and geophysical comparison of active tectonic structures reveals a region affected by continuous deformation, which includes NNW-SSE convergence accommodated by ENE-WSW folds, and orthogonal ENE-WSW extension accommodated by normal faults (with the Balanegra Fault standing out, showing a surface displacement of up to 1 mm/yr). This aligns perfectly with the results interpreted in this study, although it is true that the accommodation of deformations is more interpretable as NE-SW extension, as shown in

Figure 6.

Another area of special interest is the Strait of Gibraltar. Several studies corroborate the presence of faults in this area, particularly to the west at Punta Camarinal (51,52). When observing the relative velocities at the SFER, TARI, CEUD, and other stations in North Africa near the Strait of Gibraltar and the Bay of Cádiz, it is difficult to appreciate that these faults remain active. At first glance, it appears that the stations exhibit similar behavior, suggesting that the movement between both continents is quite stable and raising the possibility that this area is part of the same current tectonic domain underlining that the plate boundary does not cross through the Gibraltar Strait.

Focusing now on South Iberia and North Africa, the first observation is that the stations in the southern Iberian Peninsula (SFER, TARI, and ALJI) exhibit similar behavior to those in North Africa (CEUD, PVLZ, ALHU, and CHAF), as well as the Alboran Island IGN station (ALBO). These could be part of the same tectonic domain, as indicated in [

4,

13]. However, it is noted that MELI shows a more northward trend, resembling TAZA. A lack of stations between RABT and CEUD is noted, which would enable a better understanding of the behavior between the Rif region and the Western Moroccan Meseta. It is possible that these two stations are connected by the North-Middle-Atlas Fault, which could explain this similar behavior, as observed in [

12], by extending the fault line of the Middle Atlas. At this point, it is important to highlight the possibility of an active compression zone between Alborán Island and Melilla that had not been previously detected. This has also been verified through the redundancy of ROA-IGN stations. Another peculiarity is the difference in the magnitude of the deformation velocity at the Alhucemas Rock (ALHU), which could aid in understanding the expansion of the Nekor Basin [

24] with episodic campaigns of [

19], as well as the geophysical and geological studies of [

54].

As we move deeper into the Atlas, the stations show the movement of the NUBIA plate, with a clear NW trend of approximately 4-5 millimeters per year; this is especially verified by TIOU, which have long continuous data series. This result agrees with other recent studies, such as [

4,

20]. However, there are discrepancies, such as the case of AVER, which rotates slightly to the WNW and increases its velocity by more than 0.5 mm/yr compared to the others. One hypothesis may be that it belongs to the Coastal Meseta block, as shown in [

20]; however, there is also the possibility of subsidence or an undetected local behavior at this station. On the other hand, IFRN shows less deformation than the others, which may further explain or verify the active faults in the Fez region, as studied in [

12].

The highest stress zone is observed in the Gibraltar Arc, with the most significant shear points located in the Guadalquivir Basin and the Al Hoceima area. The results obtained are somewhat consistent with those previously presented in studies like [

2,

13,

14,

15], although in our case, an ENE-WSW in average compression trend is more evident. On the other hand, in the Guadalquivir Basin a NW-SE extensional trend is observed, which requires further detailed investigation. Additionally, by incorporating more data, we have gained a better understanding of the Cádiz Bay area and North African coast. Moreover, this region is known for the potential subduction associated with the continental margin, probably located beneath the Betics and the eastern Rif. According to the hypothesized models presented in studies such as [

55,

56], the delamination front in the Alboran Sea is expected to propagate in a SW direction, which would help identify the active faults associated with the Al Hoceima earthquakes. However, it is essential to use combined models with different types of studies, as seen in [

57] which aligns perfectly with our study’s results and provides a clear interpretation of the Gibraltar Arc’s behavior, suggesting that the uplift of the Betic-Rif chain is driven by the convergence of the EURA and NUBIA plates.

5. Conclusions

The use of continuous geodetic stations is crucial due to the stability achieved through long and consistent time series. The objective of this study was to introduce a new velocity field calculated from cGNSS stations located in southern Spain and North Africa including for the first time data from CEUD, PVLZ, ALHU, ALBO, MELI, CHAF and AVER and data not used before from TIOU, LIJA, ALJI, LOJA and IFRN. The methodology used to process cGNSS data is based on the PPP technique. The software PRIDE has been used to estimate daily coordinates and the program SARI has been used to analyze the corresponding coordinates time series.

This study has presented the final analysis of GNSS data from the ROA stations, which provide displacement velocities from new continuous stations that had not been processed until now, in contrast to previous studies based on episodic campaigns or more sparse CGNSS stations with few years of processing. This new set of data adds precision to previously-published research on tectonic deformations and enhances the detail of the present-day deformation of the region.

The results obtained from processing additional years at stations such as ALJI, ERRA, TAZA, BENI, LOJA, IFRN and SFER have corroborated those of previous studies, even when using the PPP program from PRIDE with different processing methods, in addition to all the supplementary stations.

EURA-NUBIA plate convergence with a WNW-ESE trend at a rate of 4.5 mm/yr, as proposed by previous studies, as well as the anti-clockwise rotation in the Gibraltar Arc in the Betic Cordillera in addition to clockwise rotation of the Rif have been confirmed. Several stations have provided specific insights. In the Rif, although ALHU has only been operational for two years, it is situated in a crucial location and provides additional information about the extension of the Nekor basin. Eastwards and southwads, TAZA and MELI exhibited very similar velocities, which could link them as part of the same zone related to the Rif foreland. AVER was positioned alongside past studies regarding the behavior of stations in the Coastal Meseta of western Morocco, although its behavior suggests that it has an unstable position, and TIOU exhibited a more westerly trend, which may be attributed to the long data collection period. In Betics, LIJA, however, exhibited a behavior that varied to the NW. The most interesting and peculiar behavior revealed for the first time in this contribution is the shortening observed between Alborán Island and Melilla, suggesting that the Eastern Alboran Sea is a weak area deformed by the Betic-Alboran-Rif seismically active shear zone, and also by folds that accomodate the Eurasian-Nubia convergence.

In summary, a network of significant interest has been introduced in a sparsely populated area, which could complement many past studies. It is important to emphasize the need for and the effort involved in maintaining such networks, as they are essential for complementing other geophysical and geological studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.R.C., A.B.H., M.C.L.P., J.G.-Z., A.J.G, M.S.P., M.M. and I.O.; methodology, D.R.-C., A.B.H., M.C.L.P., J.G.-Z., M.S.P., M.M. and I.O.; software, D.R.-C. and A.B.H.; validation, D.R.C., M.C.L.P., J.G-Z. and A.J.G.; formal analysis, D.R-C., M.C.L.P. and A.B.H.; investigation, D.R.C., M.C.L.P and A.B.H.; resources, D.R.C., A.B.H., M.C.L.P, J.G.-Z., M.S.P., M.M. and I.O.; data curation, D.R.C., A.B.H. and M.C.L.P.; writing—original draft preparation, D.R.C.; writing—review and editing, D.R.C., A.B.H., M.C.L.P, J.G.-Z., A.J.G. and M.S.P.; visualization, D.R.C.; supervision, D.R.C., M.C.L.P., A.J.G. and J.G.Z.

Funding

Spanish Navy, Ministry of Defense. Grupo RNM148 of Junta de Andalucía. PID2022-136678NB-I00 AEI/FEDER (BARACA) financed by MICIU/AEI 10.13039/501100011033 FEDER, UE.

Data Availability Statement

The data are the property of the Royal Institute and Observatory of the Spanish Navy. For any inquiries or requests, please contact the lead author for possible arrangements.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the technical staff of the ROA’s geophysics section for their daily maintenance work, especially Antonio and Javier. Likewise, we would like to thank Nick Snow for his correction and translation work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

This annex includes all the time series from the stations processed in the study. These time series correspond to horizontal positions in the east and north components.

References

- Palano, M.; González, P.J.; Fernández, J. The Diffuse Plate boundary of Nubia and Iberia in the Western Mediterranean: Crustal deformation evidence for viscous coupling and fragmented lithosphere. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2015, 430, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpelloni, E.; Vannucci, G.; Pondrelli, S.; Argnani, A.; Casula, G.; Anzidei, M.; Baldi, P.; Gasperini. P. Kinematics of the Western Africa-Eurasia plate boundary from focal mechanisms and GPS data. 2007, 169(3), 1180–1200. [CrossRef]

- Nocquet, J.M. Present-day kinematics of the Mediterranean: A comprehensive overview of GPS results. Tectonophysics 2012, 579, 220–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulali, A.; Ouazar, D.; Tahayt, A.; King, R.W.; Vernant, P.; Reilinger, R.E.; McClusky, S.; Mourabit, T.; Davila, J. M.; Amraoui, N. New GPS constraints on active deformation along the Africa–Iberia plate boundary. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, Volume 308, Issues 1–2, 2011, Pages 211-217, ISSN 0012-821X. [CrossRef]

- Vernant, P.; Fadil, A.; Mourabit, T.; Ouazar, D.; Koulali, A.; Davila, J.M.; Garate, J.; McClusky, S.; Reilinger, R. (2010). Geodetic constraints on active tectonics of the Western Mediterranean: Implications for the kinematics and dynamics of the Nubia-Eurasia plate boundary zone. 49(3-4), 0–129. [CrossRef]

- Argus, D.F.; Gordon, R.G.; DeMets, C.; Stein, S. Closure of the Africa-Eurasia-North America plate motion circuit and tectonics of the Gloria fault. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1989, 94, 5585–5602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMets, C.; Gordon, R.G.; Argus, D.F.; Stein, S. Current plate motions. Geophys. J. Int. 1990, 101, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMets, C.; Gordon, R.G.; Argus, D.F.; Stein, S. Effect of recent revisions to the geomagnetic reversal time scale on estimates of current plate motions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1994, 21, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparacino, F.; Palano, M.; Peláez, J.A.; Fernández, J. Geodetic deformation versus seismic crustal moment-rates: Insights from the Ibero-Maghrebian region. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garate, J.; Martin-Davila, J.; Khazaradze, G.; Echeverria, A.; Asensio, E.; Gil, A. J.; de Lacy, M. C.; Armenteros, J. A.; Ruiz, A. M.; Gallastegui, J.; Alvarez-Lobato, F.; Ayala, C.; Rodríguez-Caderot, G.; Galindo-Zaldívar, J.; Rimi, A.; Harnafi, M. (2015). Topo-Iberia project: CGPS crustal velocity field in the Iberian Peninsula and Morocco. GPS Solutions, 19(2), 287–295. [CrossRef]

- Gallart, J. 2006. Geosciences in Iberia: Integrated studies of topography and 4-D evolution. ’Topo-Iberia’ supported by the Spanish Government. Instituto de Ciencias de la Tierra ’Jaume Almera’ del Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. CONSOLIDER-INGENIO 2010.

- Ryan, W.B.F.; Carbotte, S.M.; Coplan, J.O.; O’Hara, S.; Melkonian, A.; Arko, R.; Weissel, R.A.; Ferrini, V.; Goodwillie, A.; Niche, F.; Bonczkowski, J.; Zemsky, R. (2009), Global Multi-Resolution Topography synthesis, Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst., 10, Q03014. [CrossRef]

- Klitgord, K.D.; Schouten, H. 1986. Plate kinematics of the central Atlantic. In: Vogt, P.R., Tucholke, B.E. (Eds.), The Western North Atlantic Region, vol. M. GSA DNAG, pp. 351–378. [CrossRef]

- Bird, P. 2003. An updated digital model of plate boundaries. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 4. [CrossRef]

- Gutscher, M.A. 2004. What caused the Great Lisbon earthquake? Science 305, 1247–1248. [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Zaldivar, J.; Gil, A.J.; Tendero-Salmerón, V.; Borque, M.J.; Ercilla, G.; González-Castillo, L.; Sánchez-Alzola, A.; Lacy, M.C.; Estrada, F.; Avilés, M.; et al. The Campo de Dalias GNSS Network Unveils the Interaction between Roll-Back and Indentation Tectonics in the Gibraltar Arc. Sensors 2022, 22, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalouan, A.; Gil, A.J.; Galindo-Zaldivar, J.; Ahmamou, M.; Ruano, P.; Lacy, M.C.; Ruiz-Armenteros, A.; Benmakhlouf, M.; Riguzzi, F. Active faulting in the frontal Rif Cordillera (Fes region, Morocco): Constraints from GPS data. Journal of Geodynamics. 2014, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadil, A.; Vernant, P.; Mcclusky, S.; Reilinger, R.; Gomez, F.; Ben Sari, D.; Mourabit, T.; Feigl, K.L.; Barazangi, M. Active tectonics of the western Mediterranean: Geodetic evidence for rollback of a delaminated subcontinental lithospheric slab beneath the Rif Mountains, Morocco. Geology 2006, 34, 529–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palano, Mimmo & González, Pablo & Fernandez, Jose. Strain and stress fields along the Gibraltar Orogenic Arc: Constraints on active geodynamics. Gondwana Research 2013. 23. 1071-1088. [CrossRef]

- Borque, M.J.; Sánchez-Alzola, A.; Martin-Rojas, I.; Alfaro, P.; Molina, S.; Rosa-Cintas, S.; et al. (2019). How much Nubia-Eurasia convergence is accommodated by the NE end of the Eastern Betic Shear Zone (SE Spain) Constraints from GPS velocities. Tectonics,38, 1824–1839. [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, P.; Sánchez-Alzola, A.; Martin-Rojas, I.; García-Tortosa, F.J.; Galindo-Zaldívar, J.; Avilés, M.; López Garrido, A.C.; Sanz de Galdeano, C.; Ruano, P.; Martínez-Moreno, F.J.; Pedrera, A.; Lacy, M.C.; Borque, M.J.; Medina-Cascales, I.; Gil, A.J. Geodetic fault slip rates on active faults in the Baza sub-Basin (SE Spain): Insights for seismic hazard assessment, Journal of Geodynamics, Volume 144, 2021, 101815, ISSN 0264-3707. [CrossRef]

- Gil, A.J.; Borque, M.; Avilés, M.; Lacy, M.; Galindo-Zaldívar, J.; Alfaro, P.; García-Tortosa, F.J.; Sanchez-Alzola, A,; Martin-Rojas, I.; Medina-Cascales, I.; Ruano, P.; Tendero-Salmerón, V.; Madarieta-Txurruka, A.; Blanca, S.; Madrigal, M.; Chacón, F.; Miras, L.; (2022). Crustal velocity field in Baza and Galera faults: A new estimation from GPS position time series in 2009 - 2018-time span. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Castillo, L.; Galindo-Zaldivar, J.; de Lacy, M.C.; Borque, M.J.; Martínez-Moreno, F.J.; García-Armenteros, J.A.; Gil, A.J. Active rollback in the Gibraltar Arc: Evidences from CGPS data in the western Betic Cordillera, Tectonophysics, Volume 663, 2015, Pages 310-321, ISSN 0040-1951. [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Zaldivar, J.; Azzouz, O.; Chalouan, A.; Pedrera, A.; Ruano, P.; Ruiz-Constán, A.; Sanz de Galdeano, C.; Marín-Lechado, C.; López-Garrido, A.; Anahnah, F.; Benmakhlouf, M. (2015). Extensional tectonics, graben development and fault terminations in the eastern Rif (Bokoya-Ras Afraou area). Tectonophysics. 663. [CrossRef]

- Chalouan, A.; Gil, A. J., Chabli, A.; Bargach, K.; Liemlahi, H.; El Kadiri, K.; Tendero-Salmerón, V.; Galindo-Zaldívar, J. (2023). cGPS Record of Active Extension in Moroccan Meseta and Shortening in Atlasic Chains under the Eurasia-Nubia Convergence. Sensors, 23(10). [CrossRef]

- Moussaid, B.; Hmidou, E.; Casas-Sainz, A.; Pocoví, A.; Román-Berdiel, T.; Oliva-Urcia, B.; C. Ruiz-Martínez, V.; Villalaín, J. (2023). The Geological Setting of the Moroccan High Atlas and Its Plate Tectonics Context. In: Calvín, P., Casas-Sainz, A.M., Román-Berdiel, T., Villalaín, J.J. (eds) Tectonic Evolution of the Moroccan High Atlas: A Paleomagnetic Perspective. Springer Geology. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Gallastegui, J.; Pulgar, J.; González-Cortina, J.; Garate, J.; Martín-Dávila, J.; Khazaradze, G.; Gil, A.J.; Ruiz-Armenteros, A.M.; Jiménez-Munt, I.; Ayala, C.; Téllez, J.; Rodríguez-Caderot, G.; Ayarza, P.; Lobato, F. (2008). Despliegue de estaciones GPS permanentes en el marco del proyecto Topo-Iberia. Conference: VII Congreso Geológico de España. Volume: Geo-Temas 10, (ISSN: 1567- 5172).

- Geng, J.; Chen, X.; Pan, Y.; Mao, S.; Li, C.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, K. (2019). PRIDE PPP-AR: an open-source software for GPS PPP ambiguity resolution. GPS Solutions, 23(91):1-10. [CrossRef]

- Teunissen, P.; Montenbruck, O. 2017. Title: “Precise Point Positioning: A Powerful Technique with Applications in GPS, GLONASS, Galileo, and BeiDou Navigation Systems”. Journal: GPS Solutions, Volume: 21, Issue: 1, Pages: 1-12.

- Dach, R.; Selmke, I.; Villiger, A.; Arnold, D.; Prange, L.; Schaer, S.; Sidorov, D.; Stebler, P.; Jäggi, A.; Hugentobler, U. 2021. Review of recent GNSS modelling improvements based on CODEs Repro3 contribution, Advances in Space Research, Volume 68, Issue 3, 2021, Pages 1263-1280, ISSN 0273-1177. [CrossRef]

- Altamimi, Z.; Rebischung, P.; Collilieux, X.; Métivier, L.; Chanard, K. (2023) ITRF2020: an augmented reference frame refining the modeling of nonlinear station motions. Journal of Geodesy, 97(47). [CrossRef]

- Saastamoinen, J. (1972). Atmospheric correction for the troposphere and stratosphere in radio ranging satellites. Geophysical Monograph Series, 15, 247–251. [CrossRef]

- Boehm, J.; Werl, B.; Schuh, H. (2006), Troposphere mapping functions for GPS and very long baseline interferometry from European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts operational analysis data, J. Geophys. Res., 111, B02406. [CrossRef]

- Bos, M.S.; Scherneck, H.G. (2024). http://holt.oso.chalmers.se/loading/.

- Lyard, F.H.; Allain, D.J.; Cancet, M.; Carrère, L.; Picot, N. FES2014 global ocean tide atlas: design and performance, Ocean Sci., 17, 615–649, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Teunissen, P.; Jonge, P.; Tiberius, C. (1997). The least-squares ambiguity decorrelation adjustment: Its performance on short GPS baselines and short observation spans. Journal of Geodesy. 71. 589-602. [CrossRef]

- Santamaría-Gómez, A. SARI: interactive GNSS position time series analysis software. GPS Solut 23, 52 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Bruyninx, C.; Legrand, J.; Fabian, A.; Pottiaux, E. (2019). GNSS Metadata and Data Validation in the EUREF Permanent Network. GPS Sol., 23(4). [CrossRef]

- Johnston, G.; Riddell, A.; Hausler, G. (2017). The International GNSS Service. Teunissen, Peter J.G., & Montenbruck, O. (Eds.), Springer Handbook of Global Navigation Satellite Systems (1st ed., pp. 967-982). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Altamimi, Z., Métivier, L., Rebischung, P., Collilieux, X., Chanard, K., Barnéoud, J. (2023) ITRF2020 plate motion model. Geophysical Research Letters, 50. [CrossRef]

- Strutz, T. Data Fitting and Uncertainty (A practical introduction to weighted least squares and beyond). 2nd edition, Springer Vieweg, 2016, ISBN 978-3-658-11455-8.

- Blewitt, G.; Kreemer, C.; Hammond, W.C.; Gazeaux, J. (2016) MIDAS robust trend estimator for accurate GPS station velocities without step detection. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 121(3):2054-2068. [CrossRef]

- Van Rossum, G.; Drake, F.L. (2009). Python 3 Reference Manual. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace.

- Wessel, P.; Luis, J.F.; Uieda, L.; Scharroo, R.; Wobbe, F.; Smith, W.H.F.; Tian, D. (2019). The Generic Mapping Tools version 6. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 20, 5556–5564. [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Mao, S. (2021). Massive GNSS network analysis without baselines: Undifferenced ambiguity resolution. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 126, e2020JB021558. [CrossRef]

- Zheng-Kang, S.; Min, W.; Yuehua, Z.; Fan, W. (2015). Optimal Interpolation of Spatially Discretized Geodetic Data. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 105. 2117-2127. [CrossRef]

- Instituto Geográfico Nacional (IGN). Catálogo de terremotos. [CrossRef]

- Altamimi, Z.; Collilieux, X.; Metivier, L. (2011) ITRF2008: an improved solution of the international terrestrial reference frame. J Geod 85:457–473. [CrossRef]

- Altamimi, Z.; Collilieux, X.; Legrand, J.; et al. (2007) ITRF2005: a new release of the international terrestrial reference frame based on time series of station positions and earth orientation parameters. J Geophys Res 112:B09401. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.M.S.; Miranda, J.M.; Meijninger, B.M.L.; Bos, M.S.; Noomen, R.; Bastos, L.; Ambrosius, B.A.C.; Riva, R.E.M.; 2007. Surface velocity field of the Ibero–Maghrebian segment of the Eurasia–Nubia plate boundary. Geophysical Journal International 169 (1), 315–324. [CrossRef]

- Grützner, C.; Reicherter, K.; Hübscher, C.; G. Silva, P. Active faulting and neotectonics in the Baelo Claudia area, Campo de Gibraltar (southern Spain), Tectonophysics, Volumes 554–557, 2012, Pages 127- 142, ISSN 0040-1951. [CrossRef]

- Luján, M.; Crespo-Blanc, A.; Comas, M. Morphology and structure of the Camarinal Sill from high-resolution bathymetry: evidence of fault zones in the Gibraltar Strait. Geo-Mar Lett 31, 163–174 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Martin-Rojas, I.; Alfaro, P.; Galindo-Zaldivar, J.; Borque-Arancón, M. J.; García-Tortosa, F. J.; Sanz de Galdeano, C.; et al. (2023). Insights of active extension within a collisional orogen from GNSS (Central Betic Cordillera, S Spain). Tectonics, 42, e2022TC007723. [CrossRef]

- Lafosse, M.; d’Acremont, E.; Rabaute, A.; Lépinay, B.; Tahayt, A.; Ammar, A.; Gorini, C. (2016). Evidence of Quaternary transtensional tectonics in the Nekor basin (NE Morocco). Basin Research. in press. [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Zaldivar, J.; Ercilla, G.; Estrada, F.; Catalán, M.; d’Acremont, E.; Azzouz, O.; et al. (2018). Imaging the growth of recent faults: The case of 2016–2017 seismic sequence sea bottom deformation in the Alboran Sea (western Mediterranean). Tectonics, 37, 2513–2530. [CrossRef]

- Perouse, E.; Vernant, P.; Chery, J.; Reilinger, R.; McClusky, S. (2010). Active surface deformation and sub-lithospheric processes in the western Mediterranean constrained by numerical models. Geology, 38(9), 823–826. [CrossRef]

- Civiero, C.; Custódio, S.; Duarte, J.C.; Mendes, V.B.; Faccenna, C. (2020). Dynamics of the Gibraltar arc system: A complex interaction between plate convergence, slab pull, and mantle flow. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 125, e2019JB018873. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).