1. Introduction

Wildfires were among the deadliest natural disasters in 2023, surpassing storms and floods [

1]. The five-year average cost of firefighting in the US is estimated at

$2.3 billion. With the number of wildfires on the rise, developing solutions for early wildfire detection is a societal issue of utmost urgency.

Several works have proposed automated solutions with a particular focus on detecting early indications of wildfires. With rapid advancements in computer vision, image-based solutions have attracted substantial attention recently. Yazdi et al. [

2] conducted a comparative study of existing wildfire monitoring approaches, including high [

3] and low-altitude remote sensing [

4], local sensing [

5], and terrestrial surveillance [

2]. They concluded that using deep learning with terrestrial surveillance to detect wildfire smoke was the most effective method of predicting wildfires. Terrestrial surveillance cameras positioned at vantage points have continuous temporal coverage with a wide field of view, producing high-resolution images. This allows wildfires to be detected in their incipient stage, the earliest stage of wildfires characterized by small smoke plumes. This makes terrestrial surveillance the most competitive monitoring approach.

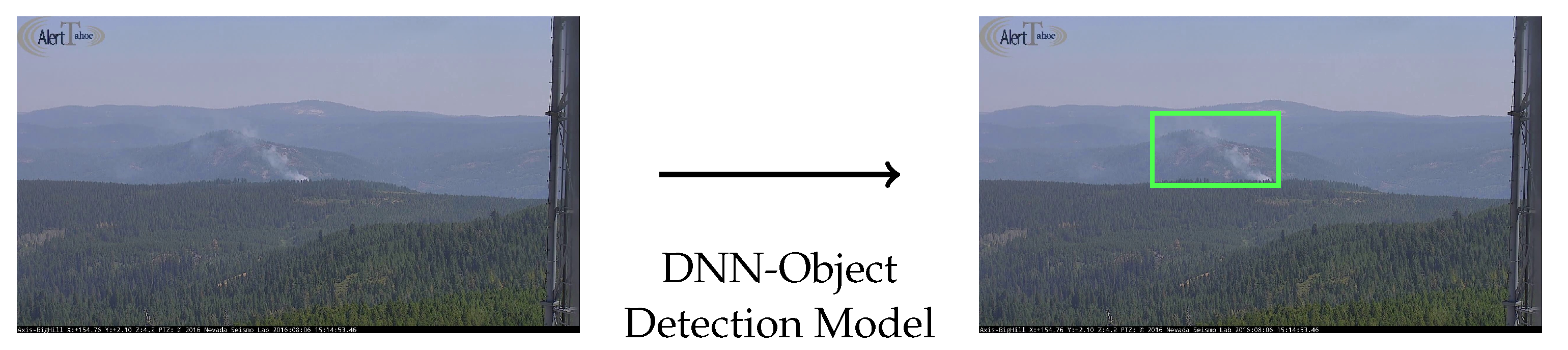

Wildfire smoke detection using deep learning typically involves object detection, a highly established task in computer vision, which consists of identifying and locating an object with a

bounding box within an image. The target object is wildfire smoke in this context.

Figure 1 illustrates wildfire smoke object detection from surveillance video images using deep learning. To develop object detection models, large-scale

deep neural network (DNN) models are trained on image data usually in quantities well over the thousands for each target object. Using the trained DNN models, smoke objects can be detected in real-time, creating a powerful synergy with continuous surveillance.

1.1. Existing DNN Solutions to Wildfire Smoke Detection

Existing wildfire smoke detection frameworks in the literature are characterized by two major DNN architectures:

CNN and

Transformer. For the CNN-based approaches, Jeong et al. [

7] proposed a real-time wildfire detection model, where a YOLOv3 [

8]-based CNN framework (for producing candidate proposals for smoke-positive regions) is combined with Long-Short Term Memory (LSTM) [

9] (for screening the candidates). While enforcing temporal consistency is demonstrated to be effective in distinguishing smoke and cloud, the model was trained on samples taken from only 12 scenes. Despite a large number of image frames, the effective sample size may be as few as 12, potentially limiting the model’s ability to generalize. Additionally, for wildfire

flame detection, which is considerably easier than

smoke detection, Al-Smadi et al. [

10] developed another CNN-based detection model using newer version of YOLOs to report on extremely high prediction performance. However, the model was trained on positive-only samples with a relatively small image count (1,723). It is not entirely clear how the limited sample size and synthetically inflated wildfire occurrences affect model robustness and generalizability.

For the transformer-based approach, there has only been one work in the literature so far. Yazdi et al. [

2] proposed NEMO (NEvada sMOke detection benchmark), using the DEtection TRansformer (DETR) [

11] framework for the first time in wildfire smoke detection. They set the practical benchmark for state-of-the-art precision (See

Table 3). To address the issue of false positives, they use several data preprocessing strategies to artificially diversify data. Specifically, they inject 260 smoke-negative background images randomly selected from the internet. They also create 116 collages from reused smoke-positive and smoke-negative images to further address this problem. Generally, collages were effective not only for reducing false positives but for introducing variety in the object’s position and size. It was shown that this preprocessing step can reduce the false alarm rate. However, detailed discussions on the model’s generalizability and robustness on real-life data are not present beyond an ablation study of the detection encoder mechanism of the model and a typical time-series detection analysis.

1.2. Challenges in Adapting DNN Solutions to Wildfire Smoke Detection

While the DNN-based object detection approach has shown promising results [

2,

7,

10], two main challenges remain: 1) the limited sample size coupled with low image diversity in wildfire smoke training images, and 2) the lack of universal solutions for improving model robustness.

The first challenge arises because of the properties of wildfire smoke. Smoke is

spatially anomalous because it occupies a small portion relative to the entire image. As a result, it is absent from the vast majority of pixels in the frames of high-resolution continuous surveillance videos. This makes manual annotation of images for object detection highly labor-intensive, necessitating ad-hoc preprocessing steps as discussed in

Section 1.1. Furthermore, smoke is

temporally anomalous becuaise it originates from it being a rare event. This results in surveillance image sequences having relatively small smoke-positive frames compared to the entire data. When trained on limited datasets, DNNs are known to produce unexpected and/or detrimental outcomes even from slight modifications to the input [

12]. In wildfire smoke detection, where training data are almost always limited, this problem can be exacerbated by the current trend of shifting from CNNs (Convolutional Neural Networks) to Transformer-based models [

13]. Despite the importance of this issue, little work has been done to assess the

robustness of wildfire detection models across various inputs.

The second challenge stems from the black-box nature of DNNs. Since the internal workings of the model, including feature extraction processes and the role of parameters, are not immediately discernible, addressing potential issues requires significant case-by-case effort, even if the source code is available. The architecture of CNNs and Transformers differs greatly, making analysis based on model-specific quantities (e.g., gradients) less practical. Since the spatiotemporal anomaly issue could potentially introduce vulnerabilities to the model, a model-agnostic framework for evaluating the model’s robustness and fine-tuning must be developed.

1.3. Contributions

To address these challenges, we propose WARP (Wildfire Adversarial Robustness Procedure), the first model-agnostic framework to comprehensively evaluate the adversarial robustness of wildfire detection models. Unlike common adversarial attack methods, which often rely on solving an optimization problem for perturbations using internal model details, WARP is model-agnostic and uses relatively simple noise injection methods. Additionally, WARP incorporates wildfire-specific contexts in designing noise tests, especially in the distinction between smoke and cloud, rather than using generic random noise. To the best of our knowledge, WARP is the first framework to offer a model-agnostic, contextual adversarial robustness evaluation method specifically tailored for wildfire detection. Insights obtained through WARP’s analysis can be used to further improve the model through data augmentation, making it a crucial first step toward a truly practical/reliable wildfire detection system. The main contributions of our study are summarized as follows.

We propose WARP, consisting of global and local model-agnostic evaluation methods for model robustness, tailored to wildfire smoke detection.

We compare the robustness of DNN-based wildfire detection models across two major neural network architectures, namely CNNs and Transformers, and provide detailed insights into specific vulnerabilities of those models.

We propose data augmentation approaches for potential model improvement based on the above findings.

2. Preliminaries

We seek to quantitatively evaluate the adversarial robustness of wildfire smoke detection models, comparing the two main DNN architectures: CNN and Transformer. This section formally summarizes the problem setting and provides a concise overview of adversarial robustness.

2.1. Problem Statement

We assume that an image-based wildfire detection model

is given, where

x is an input image, typically an image frame captured by a surveillance camera, and

is the binary label indicating whether

x contains wildfire smoke (

) or not (

). Since wildfire smoke is spatially localized, the function

f incorporates two steps: bounding box generation (locating subimages within

x) and scoring (estimating the probability of containing smoke), as illustrated in

Figure 1.

Additionally, we assume that a test dataset is available, where is the n-th image. Since the input images are often noisy due to varying weather and lighting conditions, a practical wildfire detection system must be robust to small variations in test images. The central question we address in this papers is how robust such a wildfire detection model is.

We address this question by proposing metrics indicating

changes of the classification outcomes upon introducing small perturbations to the input image. Specifically, as illustrated in

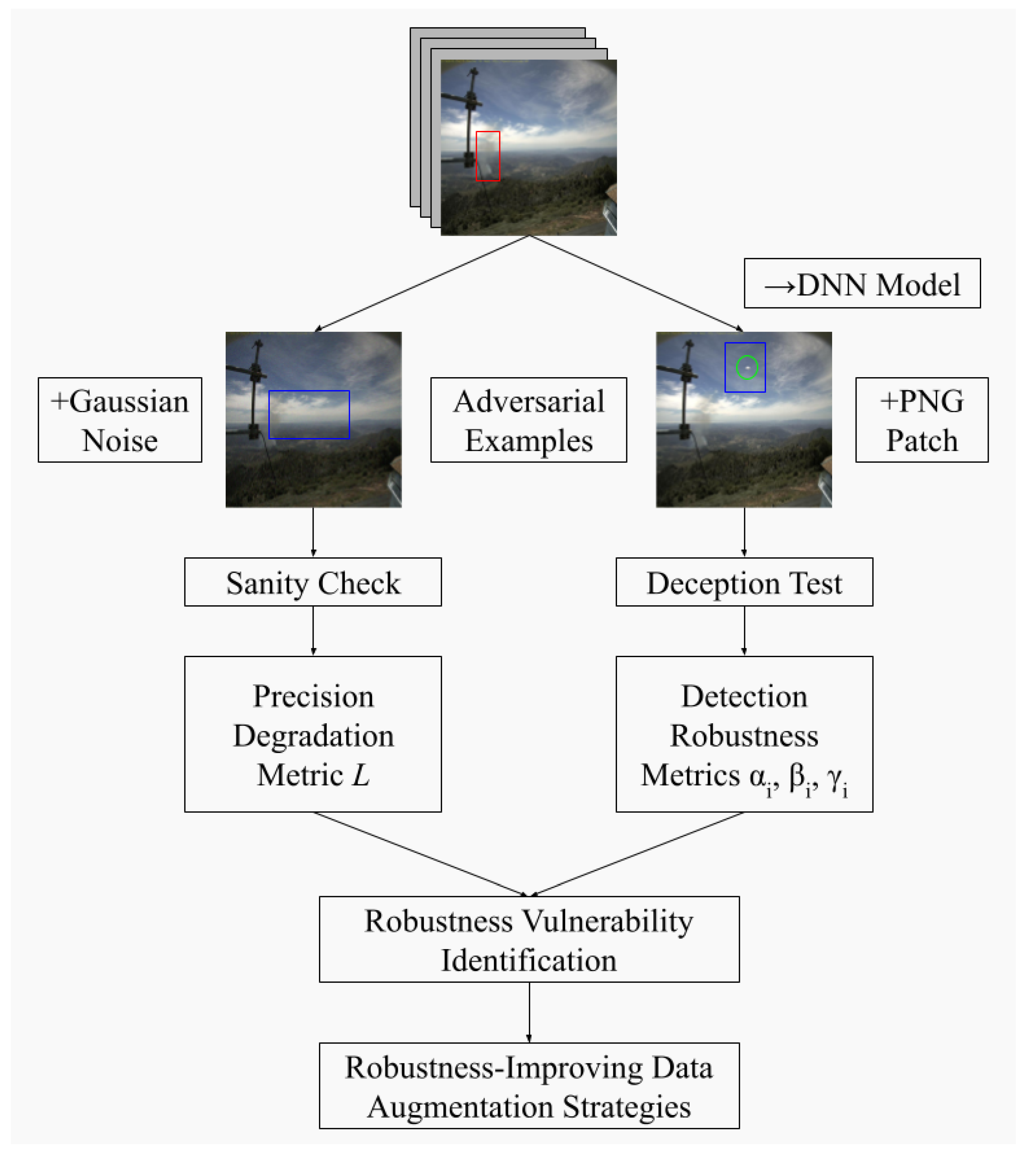

Figure 2, we compute the precision degradation metric

L, the classification flip probabilities

and

, and the localization deception rate

.

L (see

Section 3.1) seeks to quantify the model’s robustness against global noise, whereas

,

, and

(see

Section 3.2 seek to quantify the model’s robustness against local noise.

As discussed, wildfire smoke detection models need an adaptable and contextualized adversarial robustness evaluation method. For a disaster prevention task where human lives are involved, wildfire detection solutions must be

robust. That is, a DNN wildfire prediction model must be able to adapt to a variety of wildfire scenarios, not exclusive to the wildfires it has seen in its training data. We leverage adversarial attacks to identify any critical model vulnerabilities through a variety of noise perturbations. Insights obtained will be vital especially in a task like image-based wildfire smoke detection, as they can be used to further diversify the training data through data augmentation which will be discussed in

Section 5.

2.2. Adversarial Robustness

Adversarial robustness refers to a model’s resilience to external attacks on its input. “Attacks" usually involve the injection of noise perturbations (slight modifications in the form of noise) onto the original input to artificially create counterfactual (unforeseen) test scenarios. These are called adversarial examples.

In a classification task, adversarial robustness is typically evaluated by quantifying the resilience of the original detection when facing input perturbations. Let be the classification model, , where m is the dimension of the input image tensor (), k is the number of classes. In wildfire smoke detection, k is 2 as the only classes are null and smoke. The fundamental question that is considered when evaluating adversarial robustness is as follows.

Given a test input and a perturbation , compare how differs from .

If

matched the ground truth, but

does not, the model cannot be considered robust. However, it is conditionally required that

r be reasonably small, as it is almost guaranteed that the classification output will change if

r is arbitrarily large. Therefore, the most desirable perturbed image tensor

looks almost identical to the original image tensor

x, but has the maximum impact on classification outcome. The optimization problem to find such a perturbation is called an

adversarial attack [

14]:

where

l is the predicted class label for

x (i.e.,

), Loss

is a loss function for an input and output pair

, and

is a small positive error constant to keep the perturbed input close to the original input. Typically, the loss function is the same as that of the trained model.

Depending on their nature, perturbations can generally be categorized into two categories: global and local attacks [

15].

1) Global Attacks: Both [

16] and [

12] proposed global attack methods that seek the optimal perturbation that covers the entire input image. [

16] incorporated the distant constraint as a penalty term

, where

c is a constant and

is the

norm, that is added to the objective function. Moreover, [

12] proposed a more computationally efficient approach by constraining

r not by a constant but only to the sign of the gradient of the loss function

.

2) Local Attacks: Both [

17] and [

18] proposed local attack methods. [

18] proposed a single-pixel attack method based on a differential evolution framework. However, single-pixel attacks are highly inefficient for the typical object detection input which is a

pixel image. Additionally, [

17] proposed a patch-based method, where a constant patch would be directly injected into the image. These patches adapt to different backgrounds and transformations, including position, size, and rotation. Patches were generally successful at deceiving otherwise rigorously trained models, thus making them a prime tool for adversarial robustness.

There are several trends for both categories of existing adversarial attack approaches that limit their utility when applied to wildfire smoke detection.

Global attack methods often require model-specific elements for efficient computation, such as the gradient of the loss function. This necessitates the full knowledge of the architecture of the DNN model, thus making each model’s adversarial attack case-by-case. Given the variety of DNN architectures in wildfire smoke detection and the rapid development of new computer vision frameworks, this reliance on model elements may be computationally expensive. To comprehensively evaluate adversarial robustness for all wildfire smoke detection frameworks, a model-agnostic approach is necessary.

Moreover, local attack methods typically disregard the context of their task. Both single-pixel attacks and patch noise attacks are generally abstract formulations when viewed by humans, and generally do not fit in the context of wildfire smoke detection (i.e., abstract glob-like patches will not appear in camera surveillance images). Thus, their utility may be limited to deceiving the model in highly specific conditions. While this kind of noise fine-tuning can be useful for models trained to detect everyday objects on massive quantities of data, wildfire smoke detection is a more nuanced task. Contextual cues, such as the subtle differences in objects’ shape, color, and position, are paramount to distinguish smoke from clouds under limited data. Therefore, contextual awareness is essential for developing robust and reliable smoke detection systems.

3. Wildfire Adversarial Robustness Procedure

In this section, we introduce the proposed framework, WARP (Wildfire Adversarial Robustness Procedure), for comprehensively assessing the robustness of smoke detection models. WARP generates two types of adversarial examples through data augmentation: global noise (i.e., Gaussian noise) and local noise (i.e., cloud PNG patches). We then compare the original detection (red bounding box) with the perturbed detection (blue bounding box): we conduct a sanity check for images perturbed global noise, which analyzes the effect of global noise on model precision (see

Section 3.1). Additionally, we conduct the deception test for images perturbed local noise, which analyzes the robustness of the model’s localization and classification abilities on specific objects (see

Section 3.2). We later demonstrate in

Section 5 that the tests outlined above can identify vulnerabilities in robustness for wildfire detection models, which can produce data augmentation strategies tailored specifically for improving robustness for DNN models.

3.1. Global Sanity Check: Noise Overlay

For practical wildfire smoke detection, models must distinguish smoke from similar objects such as clouds, fog, and camera artifacts. Since this distinction can be subtle, model training typically requires a significant sample size, which is currently unavailable in wildfire smoke detection, as discussed in

Section 1.1. This raises questions about whether existing DNN models are robust enough against adversarial attacks.

As a preliminary test, the

global sanity check uses image-wide random perturbations. Specifically, a random noise overlay following the Gaussian distribution (

, i.e., Gaussian noise with zero mean and unit variance) of the same size as the input tensor

x is added to the entire image. The perturbed image

is given by

where

a denotes the noise level that takes a value in the range

, and

is the standard deviation of the input image tensor. The perturbation is contextualized to the input image since

is uniquely computed from that particular image.

For a given noise level, the

mAP (mAP50-95) Percentage Loss is calculated to quantify the precision loss from the addition of random noise. We choose

mAP (see

Appendix A.1 for detailed definitions) as the primary challenge metric since fixed threshold-precision metrics (i.e., mAP33, mAP50, mAP75, etc.) may only offer a limited evaluation of precision.

mAP measures the mean average precision across Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds ranging from 0.50 to 0.95, making it a robust metric [

2].

where

is the mAP score after adding random noise to the dataset, and

is the mAP score for the original dataset.

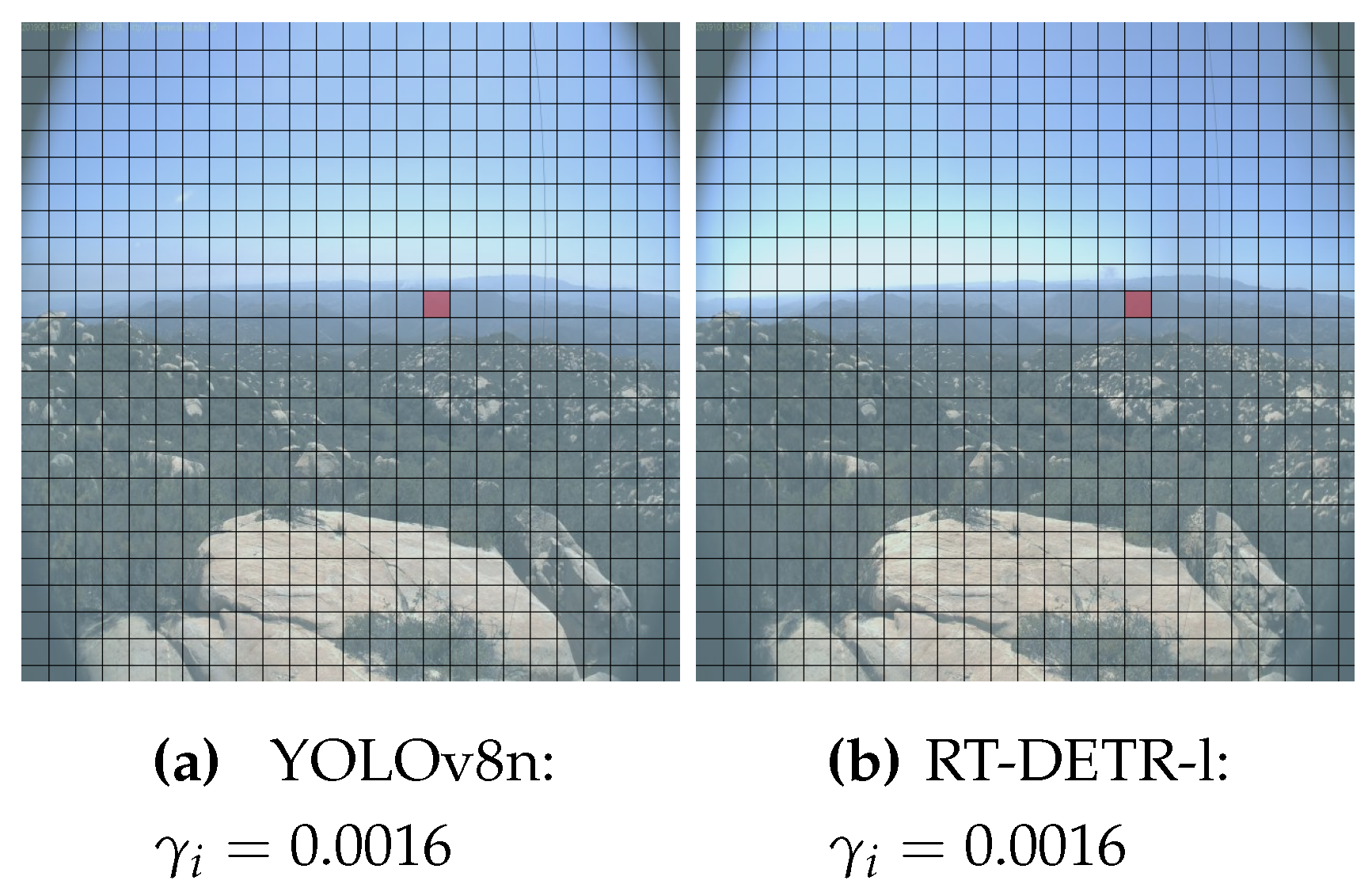

3.2. Local Deception Test: Noise Patch

The previous test considers only the context of noise level variability via

. We also proposes the

local deception test, which introduces

spatial context specific to the smoke detection task. Specifically, local noise patches (small images in the PNG (portable network graphics) format) are used to check for robustness against localized perturbations specific to wildfires. For each image

i, a PNG patch of constant size is injected at a specific spot in the image (see

Figure 3 (a) for instance). For computational efficiency, we divide each image into 25 by 25 grids, and the noise is injected in the center of each grid slot. “Noise” can be any wildfire-related object, including smoke-like objects such as clouds, or other objects in context, such as trees, buildings, glare, etc. We specifically used clouds as they are the most common subject of false positives in previous works [

2,

7,

10].

Figure 3 (b) shows the cloud PNG used in the local deception test. Despite being horizontally wider than wildfire smoke, they represent the everyday

cumulus-type clouds, which is why we selected it. After observing existing wildfire smoke data, and testing different configurations, we configured the patch to be

pixels at 100% brightness.

To quantify the robustness against patch noise, three metrics are proposed,

, and

. They are defined in Eqs. (

4), (5), and (

6) in the following sections.

3.2.1. Classification Flip Probabilities

Wildfire smoke detection models’ performance can be divided into classification and localization abilities. The classification ability refers to how precisely the model identifies an image as smoke-positive or smoke-negative. The localization ability refers to how precisely the model locates the smoke with bounding boxes given a smoke-positive image.

The Classification Flip Probabilities focuses on the vulnerability of the model’s classification abilities. When smoke-positive input images are given, a model may fail to generate bounding boxes for some images. These misclassified images can be called false negatives (FN). On the other hand, if the model successfully generates at least one bounding box in any location of an image, the image can be called a true positive (TP).

The Classification Flip Probabilities quantify how many TPs or FNs are “flipped” upon injecting

local noise. Unlike the global sanity check test, noise injection is done grid-wise. Image

i is divided into

equal grids, and local noise is injected into each grid slot. The classification outcome is then observed

times in total for the image. For each image

i, depending on whether it is a TP or FN, the classification vulnerability of a model can be quantified by calculating two conditional probabilities:

where

and

denote the null and smoke classes.

is the indicator function, which equals 1 if the specified flip occurs for image

i when the noise is injected into the

j-th grid slot. It equals 0 otherwise. Again,

is fixed at

for every image.

These image-wise probabilities are averaged over the entire test set data to evaluate the model’s classification vulnerabilities. In summary, and represents the prediction robustness that image i is smoke-positive and smoke-negative, respectively.

3.2.2. Localization Deception Rate

We propose the

Localization Deception Rate (for each image

i in the test set data) to evaluate the localization ability. Unlike the Classification Flip Probabilities,

quantifies bounding box detection robustness, which is defined below (see

Figure 4):

where

is the number of detections and its bounding box has

(see Equation

A4 for further details) with the injected noise’s bounding box.

is the number of attempts, or the number of possible positions for the noise to be injected in a

grid (

. Since

is discrete,

is also discrete. That is,

is the set of all possible values of

, and the set of all possible deception rates

is

.

A higher indicates that the model is more vulnerable to noise injection for image i. The overall localization robustness of the model can be evaluated by averaging across all images in the test set data. In a theoretical model with perfect adversarial robustness, all values of should have a frequency of 0.

3.3. Data Collection and Preparation

We used two datasets to train, validate, and test the model: the NEMO dataset [

2], curated from various sources including [

6], and a dataset from [

4], collected from the High-Performance Wireless Research and Education Network (HPWREN) database [

19].

The NEMO dataset was originally created to fine-tune DETR. It contains 2,500+ images, with roughly 90% being smoke-positive. The smoke-positive regions in the original video frames were cropped and zoomed for efficient training. Following [

2], we used this dataset for model training. In contrast, the dataset by [

4] contains more realistic 1,661 unedited smoke-positive images. We used this dataset for model testing and robustness evaluation.

Table 1 shows the data split.

3.4. Object Detection Framework

Since the ultimate goal is to establish an automated wildfire smoke detection system allowing real-time detection and continuous model improvement, we focus on object detection models allowing

real-time object detection. Real-time models allow faster feedback when detecting real-life adversarial scenarios. Additionally, we contributed to the nascent model zoo in camera-based real-time wildfire smoke detection [

2,

7,

10,

20,

21,

22,

23] by introducing two previously unused open-source models to the field.

For a CNN-based real-time object detection model, we choose YOLOv8, the 8th generation model of the YOLO (You Only Look Once) framework. It is a popular real-time object detection frameworks and is publically available on the Ultralytics API [

24].

For a Transformer-based real-time object detector, we choose RT-DETR (Real-Time Detection-Transformer), which can be viewed as a real-time variant of DETR used by [

2]. RT-DETR overcomes the computation-costly limitations of transformers by sacrificing minimal accuracy for speed by prioritizing and selectively extracting object queries that overlap the ground truth bounding boxes by a certain IoU [

25].

Pre-trained weights were transferred from COCO-dataset-trained versions of YOLOv8 and RT-DETR. Their lightweight versions, namely YOLOv8-nano (YOLOv8n) and RT-DETR-large (RT-DETR-l), were chosen to reduce computation time during robustness evaluation. Default training and inference hyperparameters were used from [

24] except for those shown in

Table 2. Extensive hyperparameter tuning is encouraged in the future.

We use metrics mAP and mAP50 to measure model precision (See

Appendix A.1 for detailed definitions), which are common challenge metrics in object detection. All training, validation, and testing were run on a Python 3.8.12 virtual environment with CUDA version 12.2, equipped with quadruple NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1080 GPUs.

4. Results

This section presents the results of the adversarial robustness of CNN- and Transformer-based wildfire detection model architectures, trained on two publicly available datasets.

4.1. Post-Training

Table 3 compares precision metrics for

real-time YOLOv8n and RT-DETR-l. Metrics for

non-real-time models are also shown for comparison, which are the Transformer-based model (NEMO-DETR) and last-generation CNN-based models (NEMO-FRCNN, NEMO-RNet), trained by [

2]. YOLOv8n outperforms RT-DETR-l in precision and parameter efficiency. Specifically, YOLOv8n achieved a very efficient mAP-to-parameter ratio with little hyperparameter tuning. YOLOv8n approached NEMO-DETR’s mAP by ≈7.80%, whereas RT-DETR-l approached it by ≈23.6%. YOLOv8n and RT-DETR-l outperformed NEMO-FRCNN and NEMO-RNet, but lost to the state-of-the-art NEMO-DETR. We expected this as YOLOv8n and RT-DETR-l had a reduced parameter size for computational efficiency. Nevertheless, both are competitive wildfire smoke detection models.

Table 3.

Comparison of smoke detection accuracies. Note that NEMO models are not real-time and for comparison purposes only. Their results were adapted from [

2].

Table 3.

Comparison of smoke detection accuracies. Note that NEMO models are not real-time and for comparison purposes only. Their results were adapted from [

2].

| |

mAP |

mAP50 |

Parameter size |

mAP-to-param ratio |

| YOLOv8n |

39.0 |

72.0 |

3.2M |

|

| RT-DETR-l |

32.2 |

69.7 |

33M |

|

| NEMO-DETR |

42.3 |

79.0 |

41M |

|

| NEMO-FRCNN |

29.5 |

69.3 |

43M |

|

| NEMO-RNet |

28.9 |

68.8 |

32M |

|

Despite its state-of-the-art transformer architecture, RT-DETR-l’s precision was lower than the CNN-based YOLOv8n. This may be attributed to RT-DETR-l’s IoU-Aware Query Selection mechanism [

25]. This mechanism prioritizes object queries with good initial IoU with ground truth. Small objects like wildfire smoke have small bounding boxes, making it likely that their IoU with initial predictions is low. Object queries for small smoke are therefore less prioritized during training, making it harder for RT-DETR to pick up smoke’s subtle features. Without extensive data fine-tuning and hyperparameter-tuning, speed-optimized transformers may be unable to take advantage of the strengths of the self-attention mechanism. This requirement can be harmful for nuanced tasks that require continual updating to accommodate unforeseen circumstances. Wildfire smoke detection may be only one such case where this may be a problem.

In addition, general model evaluation approaches using metrics that do not account for model robustness may not be appropriate. Modern metrics reflect the model’s performance under one validation dataset. Even if extensive hyperparameter tuning can significantly improve precision, it may not noticeably change results in practical testing.

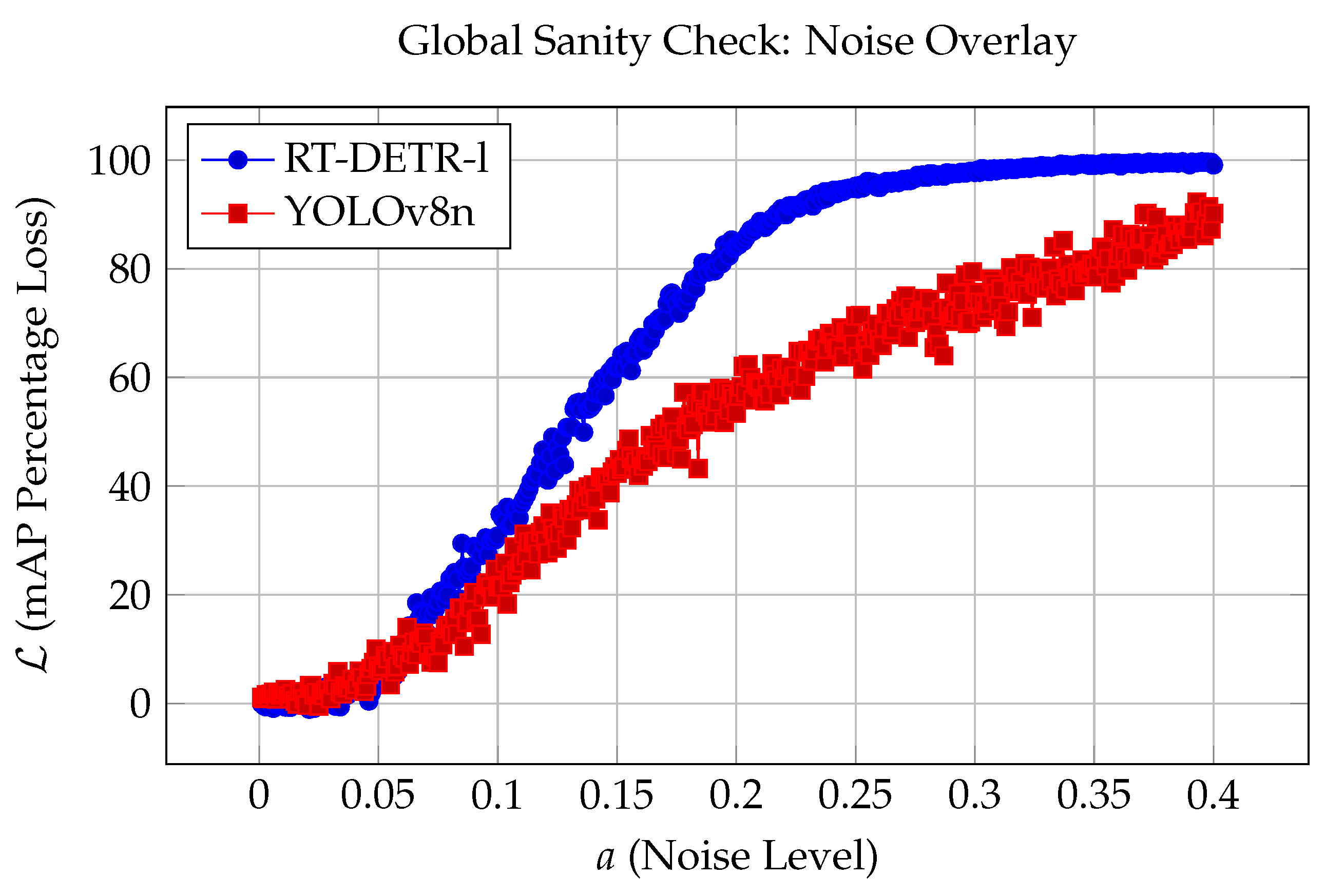

4.2. Results of Global Sanity Check

Figure 5 shows the result of the global sanity check as the noise level

a is increased in increments of 0.001 from 0.0 to 0.4 over 400 iterations. Interestingly, we observed a substantial difference between the two architectures. Specifically, the mAP Percentage Loss

for the transformer-based RT-DETR-l generally degraded at a higher rate than that of the CNN-based YOLOv8n.

for RT-DETR-l converged to ≈100 at noise level

, whereas YOLOv8n did not show signs of convergence even after the terminal noise level 0.400.

and

.

Overall, YOLOv8n was more resilient to image-wide perturbation attacks than RT-DETR-l. RT-DETR-l and YOLOv8n had the largest difference in

at noise level

, where RT-DETR-l’s

was more than 70% more than that of YOLOv8n (

and

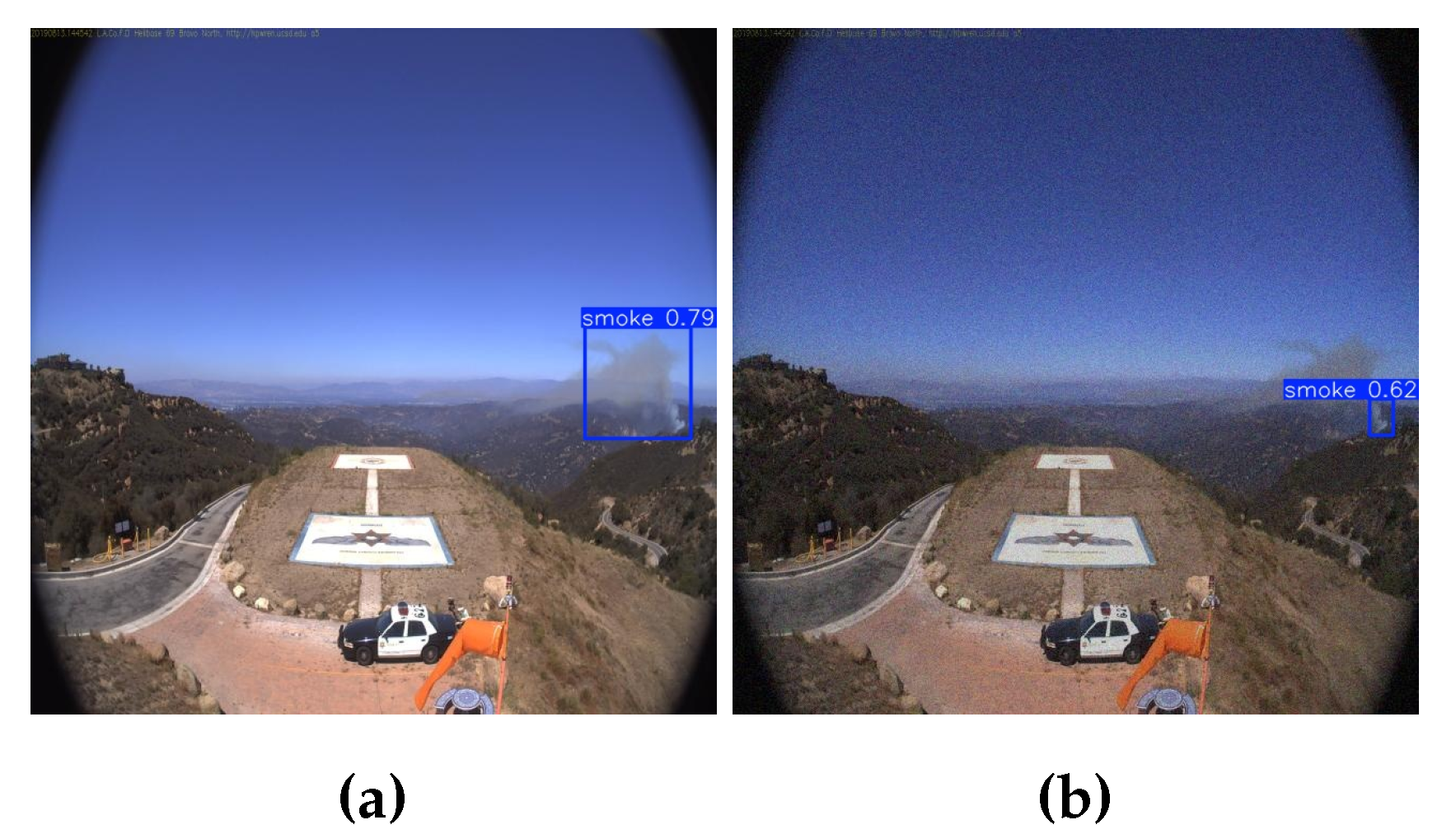

). To illustrate how the global noise affects object detection performance,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 are representative examples that compare original detection results with that at the noise level

for identical images.

To the naked eye, the noise is barely visible, only appearing as a dimming in image luminosity. There was minimal difference between the performance of the two models without noise (compare

Figure 6 (b) with

Figure 7 (a)). However, it is important to note that both models suffered in precision. YOLOv8n tended to be more conservative with its detections, only detecting smoke with a definitive white color, or in other words, at a later period of the incipient stage (see

Figure 6 (b)). On the other hand, RT-DETR-l did not have this bias but instead began to confuse the sky as smoke with relatively high confidence (see

Figure 7 (b)).

Further observation shows that both models may confuse clouds with smoke under noise stress (compare

Figure 8 (a) with

Figure 8 (b)), but RT-DETR-l makes false positives even when no clouds exist (see

Figure 9 (b)). Again, YOLOv8n became conservative with its detections, losing detection confidence and sometimes not detecting at all (see

Figure 9 (a)).

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 are two representative examples of false detections made by both models for identical images, again at noise level

.

This raises model robustness concerns when encountering real image-wide noise. A notable possibility is quality of service degradation events, where network latency or data transfer loss causes footage to become heavily distorted, which may be common given that the cameras are located in remote areas. Other possibilities may include various camera debris (for example, a rain mark near the left in

Figure 9).

4.3. Results of Local Deception Test

In this section, we summarize the results of the local deception test, namely the classification flip probabilities and the localization deception rate. They offer a nuanced review of model robustness and how it translates to detection results. In addition, we conduct an auxiliary test was conducted for further insight.

4.3.1. Result of Classification Flip Probabilities

To see the robustness of the classification outcome under local noise, we calculate the expected value of both

and

over the entire test set for both YOLOv8n and RT-DETR-l below.

where

k is the total number of images in the test dataset, which was 1,661 in the HPWREN data (See

Table 1).

The results are summarized in

Table 4. As discussed,

shows the robustness of the prediction that image

i is smoke-positive, and

shows the robustness of the prediction that image

i is smoke-negative. The results indicate a trend of wildfire smoke detection. Since smoke’s features are subtle, the smoke-positive prediction is easily flipped by injecting a cloud-like noise into even one of the 625 grids. This strongly suggests that there is substantial room for improvement in the model, possibly through

data augmentation with additional images containing smoke-like objects, as discussed in Section . On the other hand, both models show strong robustness for smoke-free predictions. In particular, no smoke-to-null flips were observed for RT-DETR-l, suggesting a greater potential of the transformer-based model for general object detection tasks.

Here, RT-DETR-l’s self-attention mechanism may work in its favor for local perturbation

classification. The architecture may help defend against classification changes under local perturbations, as demonstrated in

Table 4. This can be because of the self-attention mechanism in transformers, which captures and leverages global relationships across the image. Unlike

Section 4.2, where the entire image was perturbed, local perturbations may not substantially affect the global relationships within the original image.

4.3.2. Results of Localized Deception Rate

Table 5 shows the count of each possible

value for YOLOv8n and RT-DETR-l. The occurrence of local deception is relatively rare in both models. We also calculated the expected deception rate:

Contrary to

Section 4.3.1, RT-DETR-l’s self-attention may work to its deficit in local perturbation

localization.

Section 3.4 demonstrated that RT-DETR’s transformer architecture may cause challenges in small-object detection. In particular, object queries representing smoke’s subtle features may be de-prioritized, leading to worse precision for small objects. This causes bounding box confusion with similar small smoke-like objects like the cloud PNG patch. This is consistent with

Table 5, as RT-DETR-l frequently recorded higher

values, and its localization deception rate was more than three times that of YOLOv8n. However, more testing is required to determine the significance of these results in real conditions.

Table 5.

The frequency of detections for each observed value of . Other values were not observed.

Table 5.

The frequency of detections for each observed value of . Other values were not observed.

|

0.0000 |

0.0016 |

0.0032 |

0.0048 |

| YOLOv8n |

1629 |

32 |

0 |

0 |

| RT-DETR-l |

1570 |

85 |

5 |

1 |

For further analysis, we extracted RT-DETR-l detections with a

, and compared to their YOLOv8n counterpart. We highlight the region where the noise patch deceived the model. There were 5 images where both models detected with a

. Interestingly, 4/5 of these detections were taken from the same surveillance camera, namely from the SMER TCS9 Site.

Figure 10 (a) and

Figure 10 (b) show two such cases. There were several cases where RT-DETR-l recorded multiple deceptions whereas YOLOv8n remained completely unaffected. In particular, there were cases in which RT-DETR-l detected with a

value of 0.0032 and 0.0048 (see

Figure 11 (b) and

Figure 12 (b), respectively), but YOLOv8n remained unchanged and detected with

value of 0.0000 (see

Figure 11 (a) and

Figure 12 (a)). Below are identical images detected by the two models, where each grid represents the position at which the cloud-noise was injected. Red areas indicate noise-affected regions, whereas blue regions indicate otherwise.

Factoring out rare cases where the cloud noise completely overlapped the smoke (this could only happen in one or two grids, putting the probability at around 0.16-0.32%), both models were deceived when the cloud PNG patch was near the smoke. This is alarming, since the cameras are positioned at vantage points, and clouds are more clearly visible at higher altitudes. Thus, the occlusion of smoke by clouds would be a relatively common occurrence. Furthermore, it can be explained that the models confuse smoke with cloud since both are similar in features, and the parts of the cloud PNG patch merge with the smoke at times. As seen with YOLOv8n, the models tend to reliably detect when the smoke has developed a clear white coloration. Thus, the models may have interpreted the cloud as the origin point of the smoke, even when the direction of the smoke plumes suggested otherwise.

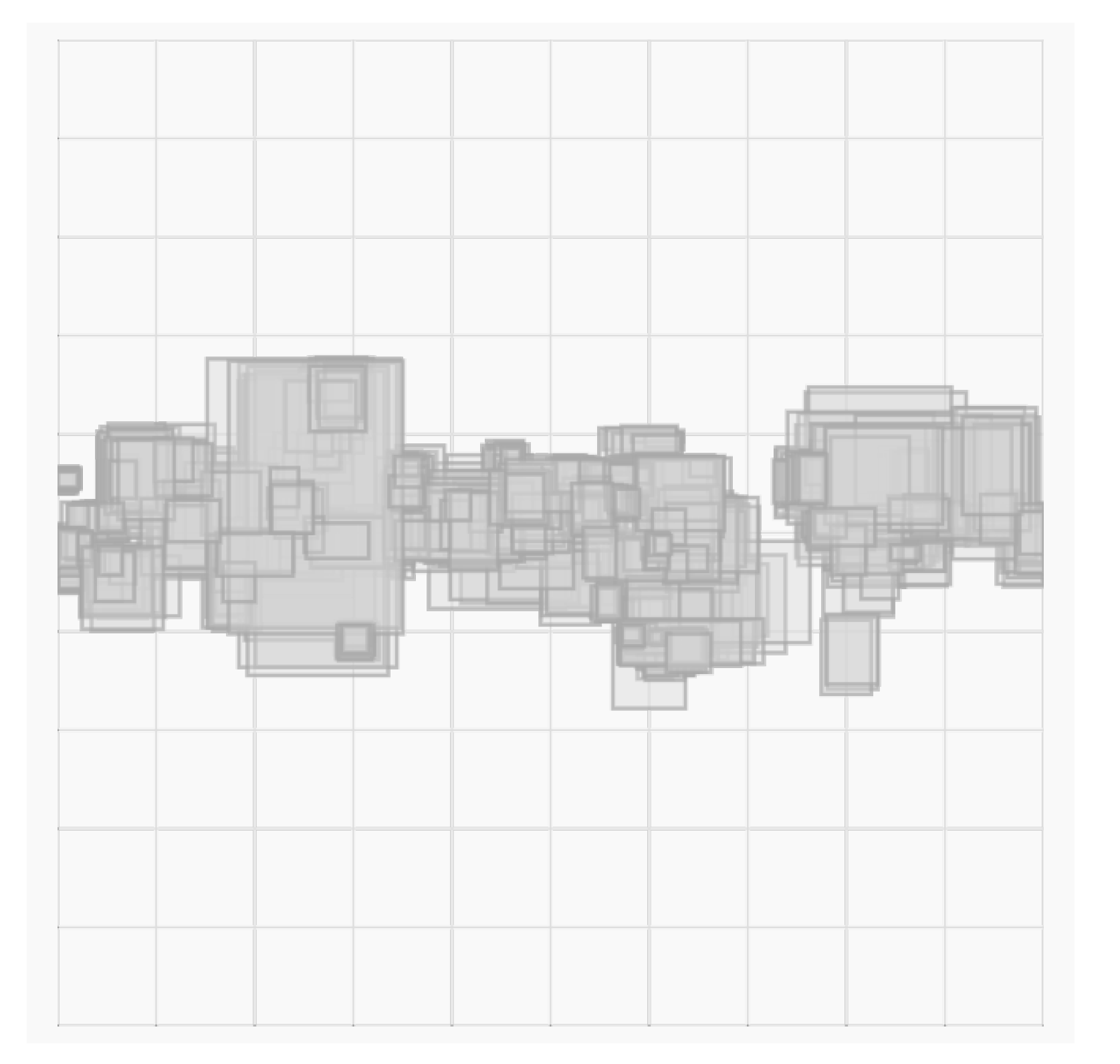

To test if there was a spatial relationship between the deceptions, we enumerated the cumulative number of noise-affected detections for each slot that the patch noise was injected for both models. Both models exhibited a slight bias to be deceived at the center regions (see

Figure 13 (a) and

Figure 13 (b)). A potential explanation is that smoke is most frequently depicted in the middle horizontal of the image. It becomes easier for human observers to spot and annotate as rises above the horizon, which is frequently in this region. This creates an annotation bias in the test set (see

Figure 14). Thus, cloud PNG patches may appear as part of the smoke in this zone.

5. Discussion

Based on our analysis, we propose the following data augmentation strategies. These solutions should provide future training data for first-generation YOLOv8 and RT-DETR-based wildfire detection models. While these preliminary solutions appear to be promising, a more specific evaluation of adversarial robustness for proceeding generation models should be a topic of future research. Because this framework is model-agnostic, even if new DNN architectures are incorporated into wildfire smoke detection, these solutions may still be applied to diversify the limited quantity of wildfire smoke data. We propose the following data augmentation techniques for robustification and their reason for implementation.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we introduced WARP (Wildfire Adversarial Robustness Procedure), the first-ever model-agnostic framework for evaluating the adversarial robustness of wildfire smoke detection models, designed to address limitations arising from insufficient variety in smoke images.

WARP supports both global and local adversarial attack methods. While the global attack method employs image-contextualized random noise overlays, the local attack method is tailored to address two key aspects of smoke detection: 1) classification between smoke-positive and smoke-negative instances and 2) smoke object bounding box localization.

In a comprehensive comparative study, we assessed the adversarial robustness of CNN- and Transformer-based real-time smoke detection models, leveraging WARP’s model-agnostic capabilities. The main findings are summarized below:

The Global Sanity Check revealed that the transformer-based RT-DETR-l model was substantially more vulnerable to global noise injection compared to the CNN-based YOLOv8, even at noise levels barely visible to the human eye.

Analysis of the Classification Flip Probabilities revealed that both CNN- and Transformer-based models are extremely sensitive to local noise injection. A single injected noise grid (out of 625 total) resulted in flip probabilities of and in the smoke-positive prediction for the CNN and Transformer models, respectively. These results underscore the need for further model training using data augmentation techniques.

Analysis of the Localization Deception Rate revealed areas within the images that were particularly vulnerable to local noise injection. Detailed analysis suggests that human annotation bias may contribute to this vulnerability in the middle-horizontal region, offering insights for future data augmentation strategies to enhance model robustness.

Based on these findings, we proposed wildfire-specific data augmentation approaches. We leave the detailed analysis of the proposed data augmentation approaches in future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.I. and L.Y.; methodology, R.I.; software, R.I. and L.Y.; validation, R.I. and L.Y.; formal analysis, R.I.; investigation, R.I.; resources, R.I.; data curation, L.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, R.I.; writing—review and editing, R.I. and L.Y.; visualization, R.I.; supervision, L.Y; project administration, L.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project is supported in part by the National Science Foundation OIA-2148788.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study are openly available: NEMO [

2], HPWREN [

4,

19].

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Amirhesam Yazdi from the University of Nevada Reno for their thoughtful discussions, alongside Mr. Patrick Watters’s generous help for debugging. We also acknowledges Mr. Austin Parkerson for his continued support in providing the GPU computing service which was vital for the experimentation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WARP |

Wildfire Adversarial Robustness Protocol |

| DNN |

Deep Neural Network |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| YOLO |

You Only Look Once |

| LSTM |

Long Short Term Memory |

| mAP |

mean Average Precision |

| NEMO |

NEvada sMOke detection benchmark |

| DETR |

DEtection TRansformer |

| IoU |

Intersection over Union |

| HPWREN |

High-Performance Wireless Research and Education Network |

| RT-DETR |

Real-Time DETR |

| COCO |

Common Objections in COntext |

| FRCNN |

Faster Region-based Convolutional Neural Network |

| RNet |

RetinaNet |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Mean Average Precision (mAP) is a common metric for precision in machine learning. It is obtained by calculating numerous other sub-metrics, which are shown here.

Precision and

Recall are well established performance metrics in machine learning.

Average Precision can be calculated by taking the area beneath the Precision-Recall curve (i.e.,

), typically using the Trapezoid Rule.

where TP is the number of true positives, FP is the number of false positives, and FN is the number of false negatives. A detection is considered a true positive when the detection bounding box

A overlaps the ground truth bounding box

B by a certain overlap threshold.

The degree of overlap is quantified by the

Intersection over Union (IoU), which is obtained by

The

mean Average Precision (mAP) can be obtained by taking the average of AP across all classes.

where the class index

l runs over all the class labels

with

k being the total number of classes.

There are certain variations of mAP based on what IoU threshold is used. The most common is mAP50:95 or simply mAP, which is the average of mAP scores from thresholds 50 to 95 at increments of 0.05. There is also mAP50, where mAP is calculated with a fixed overlap threshold of .

References

- Salas, E.B. Number of fatalities due to natural disasters U.S. 2023, 2024.

- Yazdi, A.; Qin, H.; Jordan, C.B.; Yang, L.; Yan, F. Nemo: An open-source transformer-supercharged benchmark for fine-grained wildfire smoke detection. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.M.; Utkin, A.B.; Lavrov, A.V.; Vilar, R.M. Development of neural network committee machines for automatic forest fire detection using lidar. Pattern Recognition 2004, 37, 2039–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govil, K.; Welch, M.L.; Ball, J.T.; Pennypacker, C.R. Preliminary results from a wildfire detection system using deep learning on remote camera images. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmpoutis, P.; Papaioannou, P.; Dimitropoulos, K.; Grammalidis, N. A review on early forest fire detection systems using optical remote sensing. Sensors 2020, 20, 6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ALERTWildfire. Wildfire Dataset, 2023.

- Jeong, M.; Park, M.; Nam, J.; Ko, B.C. Light-weight student LSTM for real-time wildfire smoke detection. Sensors 2020, 20, 5508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmon, J. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S. Long Short-term Memory. Neural Computation MIT-Press 1997.

- Al-Smadi, Y.; Alauthman, M.; Al-Qerem, A.; Aldweesh, A.; Quaddoura, R.; Aburub, F.; Mansour, K.; Alhmiedat, T. Early wildfire smoke detection using different yolo models. Machines 2023, 11, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision. Springer, 2020, pp. 213–229.

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Shlens, J.; Szegedy, C. Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6572. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Guo, J.; Liu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Xiao, A.; Xu, C.; Xu, Y.; et al. A survey on vision transformer. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2022, 45, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molnar, C. , Interpretable Machine Learning: A Guide for Making Black Box Models Explainable; Christoph Molnar, 2024; chapter 10.4 Adversarial Examples.

- Chen, P.Y.; Hsieh, C.J. Adversarial robustness for machine learning; Academic Press, 2022.

- Szegedy, C. Intriguing properties of neural networks. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6199. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.B.; Mané, D.; Roy, A.; Abadi, M.; Gilmer, J. Adversarial patch. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.09665. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.; Vargas, D.V.; Sakurai, K. One pixel attack for fooling deep neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2019, 23, 828–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HPRWEN. The HPWREN Fire Ignition images Library for neural network training, 2023.

- Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, K.; An, K. A Deep Learning-Based Experiment on Forest Wildfire Detection in Machine Vision Course. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 32671–32681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, P.; Gupta, H.; Pachauri, N.; Sharma, V.; Verma, O.P. Real-time wildfire detection via image-based deep learning algorithm. In Proceedings of the Soft Computing: Theories and Applications: Proceedings of SoCTA 2020, Volume 2. Springer, 2021, pp. 539–550.

- Oh, S.H.; Ghyme, S.W.; Jung, S.K.; Kim, G.W. Early wildfire detection using convolutional neural network. In Proceedings of the International workshop on frontiers of computer vision. Springer, 2020, pp. 18–30.

- Wei, C.; Xu, J.; Li, Q.; Jiang, S. An intelligent wildfire detection approach through cameras based on deep learning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultralytics. Ultralytics YOLO Docs, 2024.

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Detrs beat yolos on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 16965–16974.

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.Y.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).