1. Introduction

Forest fires are a type of natural disaster characterized by their sudden onset, significant destructiveness, and considerable challenges in emergency response. They pose a threat not only to the stability of ecosystems but also to human life and the integrity of infrastructure [

1]. According to statistics, in 2022, China experienced 709 forest fires, with an affected forest area of approximately 0.5 million hectares [

2]. In 2023, the number of forest fires decreased to 328, and the affected area was about 0.4 million hectares [

2]. Research indicates that early forest fire detection technology can identify fire sources at the initial stage of a fire, thereby helping to keep fire losses within an acceptable range [

3].

China has vast territories with extensive forest areas and complex terrain, resulting in numerous monitoring blind spots. Moreover, the early signs of forest fires are often not obviously and can be easily obscured by vegetation, which presents significant challenges for fire detection. Traditional fire detection methods typically rely on varIoUs sensors to detect early signs of fires, such as optical sensors [

5], acoustic sensors [

6], and gas concentration sensors [

7]. However, given the extensive forest coverage in China, deploying a large number of sensors in forest areas is not only costly but also cannot guarantee the accuracy and real-time nature of detection. With the continuous development of digital forestry and intelligent technologies, image-based early forest fire detection technology based on deep learning has gradually gained widespread application. This technology can autonomously learn fire characteristics from a vast amount of image data, overcoming the limitations of traditional manual feature extraction [

8]. In addition, systems combining drones with optical sensors can achieve rapid and accurate early fire detection [

9]. Visible light sensors, which capture images with distinct features and rich texture details, can intuitively display the situation on-site and are thus widely used in image-based fire detection technology [

10].

A forest fire detection system based on aerial visible light images typically consists of three key components: image acquisition, fire recognition, and fire warning [

11]. The image acquisition component captures real-time image data of forest areas using drones equipped with visible light cameras. The fire recognition component analyzes the images using target detection algorithms from deep learning to identify the presence of fires. The fire warning component then promptly alerts firefighting personnel upon fire detection. The fire recognition component is the core of the fire detection system, with research mainly focusing on constructing appropriate datasets and optimizing target detection algorithms to improve the accuracy and real-time nature of fire detection.

Deep learning-based target detection algorithms are mainly divided into two categories: two-stage algorithms represented by the R-CNN (Region-CNN) series and one-stage algorithms represented by the YOLO (You Only Look Once) series [

12]. Due to the advantage of one-stage detection algorithms in detection speed, they are widely used in fire detection tasks with high real-time requirements. Xue et al. [

13] and Zhao et al. [

14] both focused on the flame characteristics of forest fires in their research. Xue et al. improved the YOLOv5 algorithm by adding a small object detection layer and attention mechanism, modifying the SPPF and PANet structures, and validated it using a self-built forest fire dataset. Zhao et al. replaced the backbone feature extraction network of YOLOv3 with EfficientNet to enhance the detection performance of small objects, but their dataset was not from a forest scene. Zu Xin ping et al. [

15] targeted the smoke characteristics of forest fires, modified the backbone network and prediction network of YOLOv3 SPP to improve the accuracy and real-time nature of fire detection. Su Xiaodong et al. [

16] and Pi Jun et al. [

17] replaced the backbone network of YOLOv5 with lightweight network models and introduced attention mechanisms at appropriate positions to optimize the detection performance of aerial forest fire datasets. With the accelerated iteration of algorithms, researchers have explored more cutting-edge technological paths. Zhang et al. proposed the YOLOv8-FFD model, which introduces deformable convolution modules and cross-scale feature fusion mechanisms. On the FireNet public dataset for forest fire detection, it achieved a 91.2%mAP,a 6.3 percentage point improvement over the baseline model [

18].Wang et al. developed a YOLO-Fusion framework based on visible light-infrared dual-modal fusion. The proposed dynamic weight allocation module effectively solved the feature alignment problem of heterogeneous images, achieving a recall rate of 89.7%in nighttime forest fire detection [

19].

For UAV inspection scenarios, Liu et al. constructed a 3D-YOLOv5 model containing elevation features. Through a height-aware feature pyramid network(HA-FPN),it optimized the scale sensitivity of aerial images, reducing the false alarm rate in complex terrain forest fire detection to 2.1% [

20].The Chen teamattempted to combine the Transformer architecture with YOLOv9,proposing a Swin-YOLO model with a dynamic sparse attention mechanism. It achieved a detection accuracy of 87.4%for small-target flames while maintaining real-time performance at 38FPS [

21]. Notably, Zhou et al. introduced the FireDet-3D system, which innovatively uses Neural Radiance Fields(NeRF)technology to build a 3D fire simulation environment and integrates an improved YOLOv10 architecture. This system first realized 3D spatial positioning of forest fires, controlling spatial errors within 1.5 meters [

22]. Meanwhile, the Gupta team(2025)developed EdgeFireNet, which uses Neural Architecture Search(NAS)technology to automatically optimize network structure. It achieved a real-time detection performance of 24FPS on embedded devices with power consumption reduced to 3.2W [

23].

Overall, most researchers exploring deep learning-based image-based early forest fire detection techniques are more focused on algorithm optimization to improve detection accuracy and real-time performance. However, these studies tend to ignore the unique characteristics of early forest fires, tend to simplify the detection of targets, and do not fully consider the applicability in UAV low computing power scenarios. In terms of dataset selection, scholars rarely conduct a comprehensive assessment of its suitability for forest environments.

To address these issues, this study proposes key factors to consider when collecting data on early forest fires, combining the characteristics of early forest fires with an aerial perspective. Based on these factors, a customized early forest fire dataset was constructed. Because of the low latency and low computing power consumption of YOLOv5s, the actual deployment difficulty is greatly reduced, so a new early forest fire detection algorithm YOLO-UFS is proposed with YOLOv5s as the baseline model. In order to further improve the detection performance, the combination of detection technology and unmanned aerial vehicle system was considered in this study. By modifying the network structure and loss function of YOLOv5s, and introducing the ObjectBox detector and NAM attention mechanism, a lightweight detection model is realized without sacrificing accuracy, so as to improve the real-time processing ability of the system's detection information.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

A New Early Forest Fire Detection Model: YOLO-UFS Model: We propose a novel detection model, YOLO-UFS, designed to enhance drone-based early forest fire and smoke detection by addressing low computational cost, low latency, complex background interference, and the coexistence of smoke and fire.

Self-built Dataset: A custom dataset was created, comprising three types of data: small flames only, smoke only, and combined small flames and smoke. Experiments were conducted to compare its performance with classical algorithms.

Model improvements: We improved by replacing the C3 module with C3-MNV4 to reduce parameters and improve feature extraction. The AF-IoU loss function optimizes detection accuracy, especially for small targets. NAM concentrates the kernel in the target region, while ObjectBox and BiFPN improve detail retention and generalization. These upgrades make YOLO-UFS more accurate and efficient in early forest fire detection.

The structure of the paper is as follows: 2.1. The data collection process, improvement methods, evaluation indicators, and experimental environment parameters are described in detail. 2.2. The improved method based on YOLOv5s is described in detail to propose YOLO-UFS. In

Section 3, the effectiveness of the proposed method is confirmed by ablation experiments and comparison with classical models, and the effectiveness of the self-built dataset in the training of early forest fire models is confirmed by in-depth analysis and discussion of the detection results of public datasets and self-built datasets.

Section 4 summarizes and outlines future research directions. All of the results obtained are discussed in

Section 5.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Early Forest Fire Selection Image Acquisition

In the context of early forest fire detection from an aerial perspective, the primary focus is on data collection in forest environments and the detection of fire-related targets. When constructing a dataset for early forest fires, it is essential to consider the characteristics of forest fires and the features of aerial images. The following are key considerations:

- a.

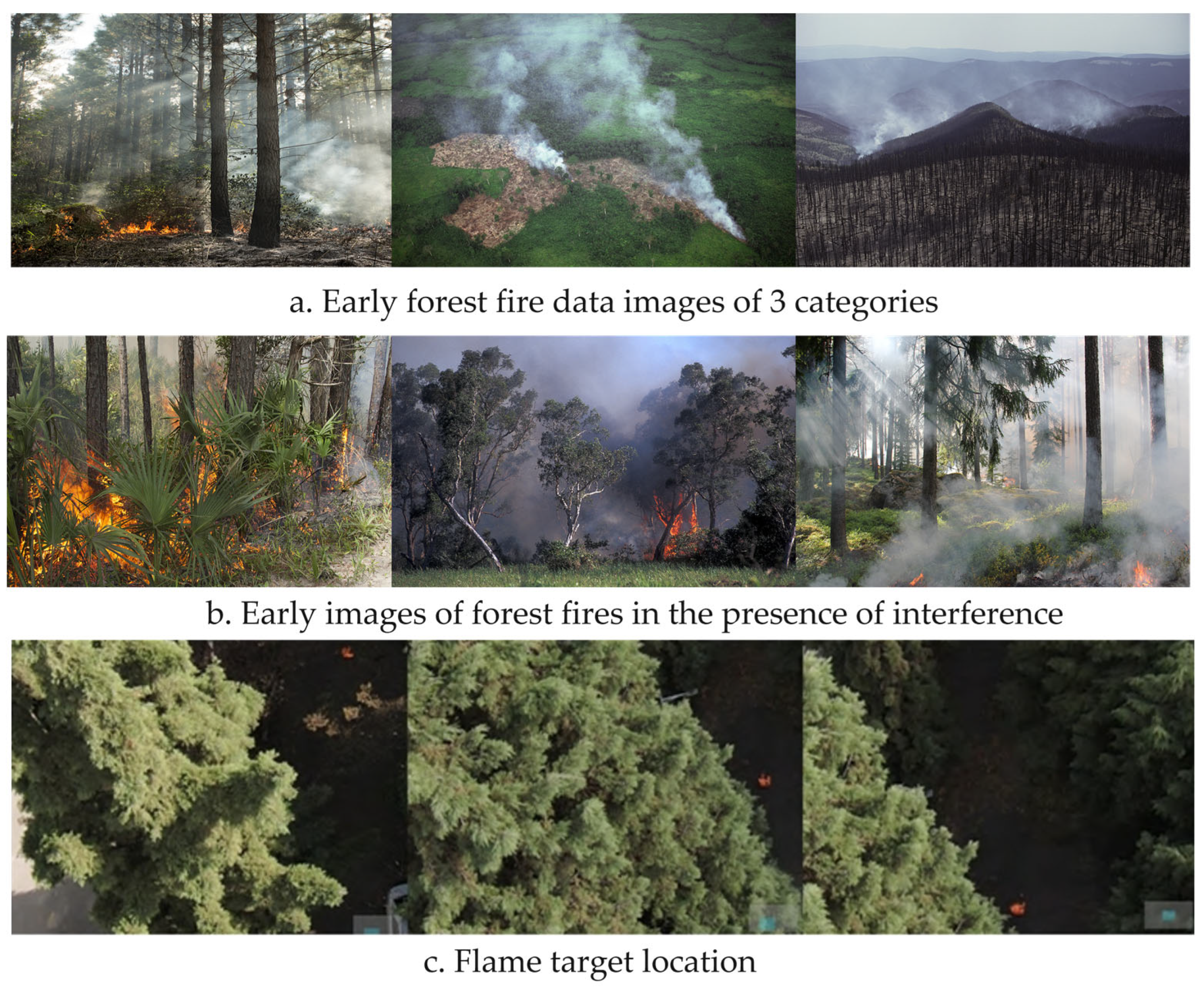

Target Identification

During the early stages of a forest fire, the flames are typically small and not easily distinguishable. In aerial images captured by drones, small flames can be easily obscured by surrounding vegetation, making them difficult to detect. Relying solely on flames as the detection target can lead to missed detections. However, early fires often produce significant amounts of smoke, which can spread across the forest canopy and is more easily detected. Therefore, incorporating both smoke and flames as detection targets can enhance detection accuracy and reliability [

24]. Consequently, the dataset should include three typical types of early forest fire images: scenes with only small flames, scenes with only smoke, and scenes with both flames and smoke, as shown in

Figure 1.a.

- b.

Interference with Detection Targets

In forest environments, numerous objects can interfere with the detection of flames and smoke, leading to false positives. Flames may be confused with objects of similar color and shape, such as sunlight reflections or reddish-yellow leaves [

25]. Smoke characteristics, including color and shape, can vary depending on environmental conditions. For instance, when the forest contains flammable materials with high oil content or is at a higher temperature, smoke may appear grayish-black or black, and tree shadows in sunlight can be mistaken for smoke. Conversely, when there are fewer flammable materials or the temperature is lower, smoke may appear blue-white or white, and objects like mist, snow, or clouds can be misidentified as smoke [

26]. Including these potential interferences in the dataset can increase the diversity of scenarios and enhance the accuracy of early forest fire detection. Examples of fire images with interferences are shown in

Figure 1.b.

- c.

Position of Detection Targets

During forest fire patrols, drones typically follow predefined flight paths [

27], and the areas scanned by their cameras are limited. To improve patrol efficiency, areas already scanned are not rechecked, meaning that fire locations may not always be within the camera's field of view. Additionally, early forest fires are often obscured by surrounding vegetation, further complicating detection. Therefore, when collecting data, it is crucial to account for the possibility that flames and smoke may appear in varIoUs positions within the image and may be partially or fully obscured by vegetation,as illustrated in

Figure 1.c.

2.1.1. Data Augmentation Processing

Initially, the image data underwent resizing to standardize all images to a resolution of 640×640 pixels. Subsequently, the LabelImg tool was employed to annotate the images [

28]. The labels were categorized as "fire," and the dataset was divided into training, validation, and testing sets in a 7:2:1 ratio. Through in-depth analysis of the dataset and detection targets, the diversity of the samples was enhanced. To further enrich the data, this study applied data augmentation techniques, including HSV color space transformations, horizontal and vertical flipping of images, and contrast adjustments.

For images with inconspicuous or small-sized targets, the Mosaic data augmentation method was utilized [

29]. This technique involves randomly cropping, scaling, and stitching together four images, making small targets more recognizable to the model. This approach effectively increases the number of samples [

30] and significantly reduces the risk of missed detections. An example of an image after data augmentation is shown in

Figure 2.

2.1.2. Dataset Construction

In this study, we defined samples containing early forest fire characteristics as positive samples and included the following three types of data: samples containing only small flames, samples containing smoke only, and samples containing both small flames and smoke. Conversely, samples that do not contain early fire features are defined as negative samples, and these samples usually contain only interferences, or images of the forest that resemble the fire scene but do not have the actual fire.

Based on the above image acquisition analysis, we constructed an early forest fire dataset. Firstly, the experimental simulation drone patrols the forest area to obtain multi-view early forest fire videos. The videos were shot at Northeast Forestry University and were filmed using a DJI drone with a visible light camera to simulate an early forest fire scene. Secondly, in order to increase the diversity of the dataset, we also collected early forest fire images and videos from the perspective of drones from the network and public datasets. A total of 10476 early forest fire images (positive samples) were obtained by sampling the video frames using Pycharm software, and one image was captured every 60 frames. According to the 4:1 ratio, these images were divided into a training set and a validation set, where the training set contained 7685 early forest fire images and the validation set contained 620 early forest fire images. In addition, an additional 639 forest images (negative samples) were collected and added to the validation set.

Table 1 shows the distribution of different types of samples in the training and validation sets.

In order to label the early forest fire samples, we used the commonly used image annotation tool labelImg. In the labeling process, flame and smoke are labeled as two independent detection targets, in which the flame characteristics of the fire are marked with the "fire" label and the smoke characteristics of the fire are marked with the "smoke" label.

2.2. The YOLO-UFS Model

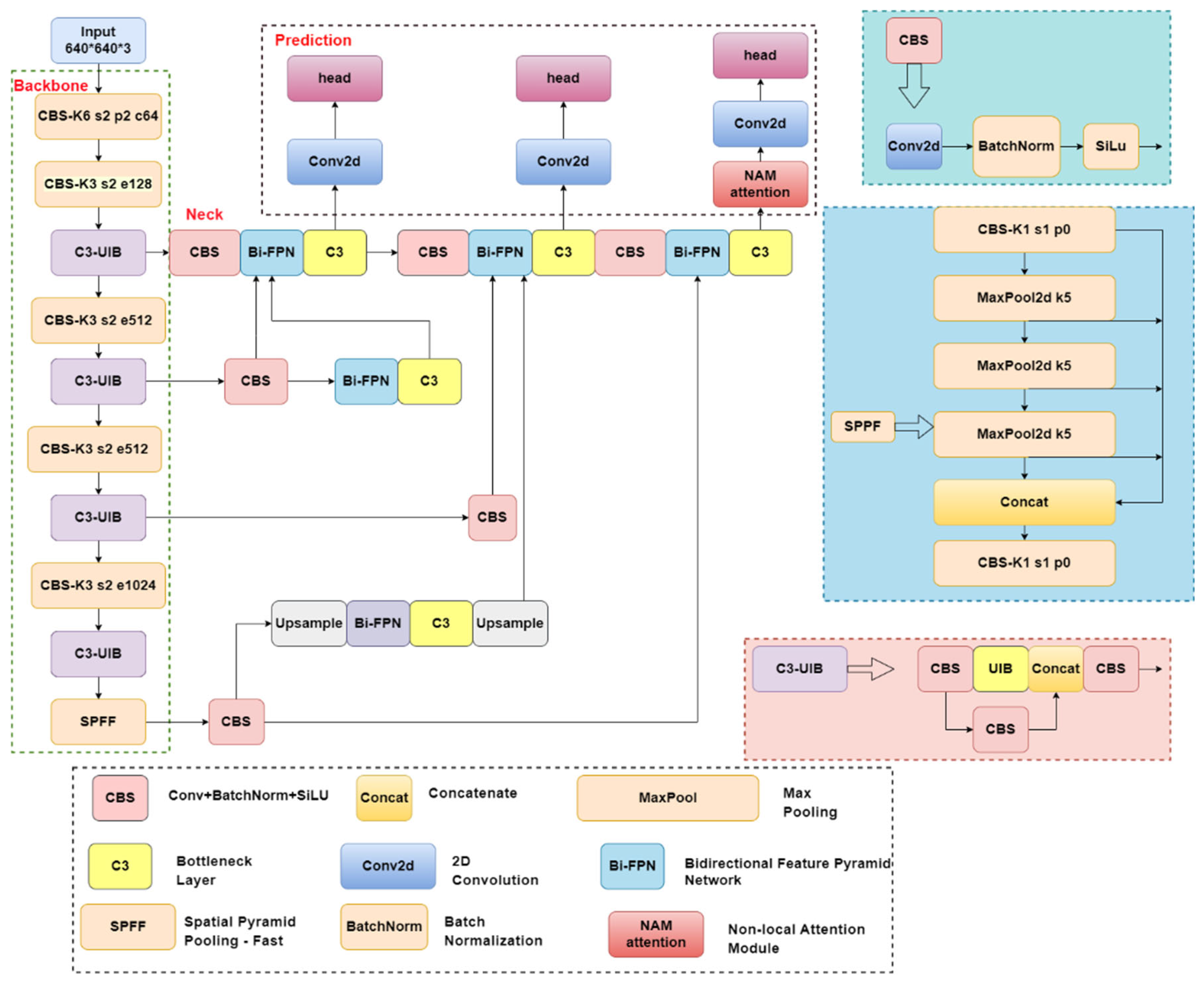

The YOLO-UFS model based on the enhanced YOLOv5s algorithm proposed in this study has been optimized to better adapt to the needs of forest fire detection in UAVs scenarios. In addition, the model has been improved in terms of detection accuracy and ability to recognize fine details, improving its overall robustness.

Figure 3 illustrates the optimized network structure for an improved algorithmic model.

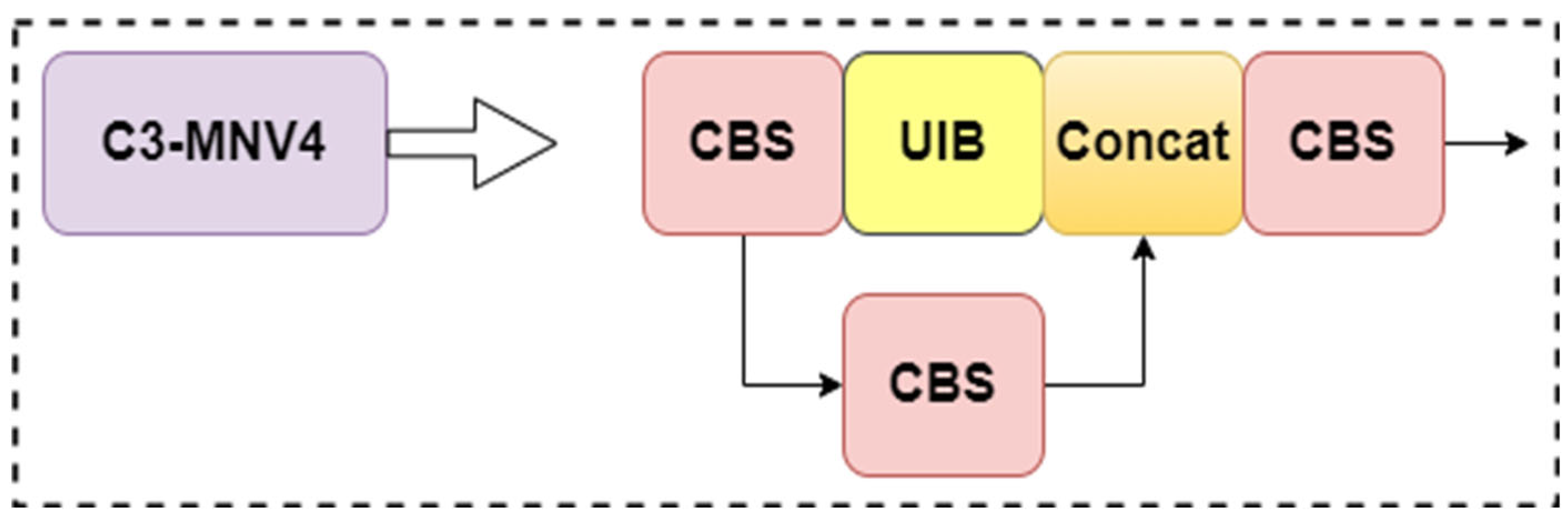

2.2.1. Replace the C3 Module

In embedded devices, computing resources are limited, so the detection model needs to be lightweighted. The Universal Inverted Bottleneck (UIB) module proposed in MobileNetV4 [

31] provides an effective solution to this problem. This module can be applied to the C3 module in the YOLOv5s backbone network to reduce the number of parameters of the model.

The UIB module integrates the Inverted Bottleneck (IB), ConvNext, Feed-Forward Network (FFN) in MobileNetV2 [

32], and the new Extra Depth (ExtraDW) variant in MobileNetV4. Among them, IB processes the extended feature activation through spatial blending. ConvNext performs spatial blending operations before feature expansion; ExtraDW can improve the depth and receptive field of the network without significantly increasing the computational cost. FFN consists of two 1×1 point-by-point convolutions stacked with an activation layer and a normalization layer in between. The UIB module enables adaptive mixing of spaces and channels, flexible adjustment of the receptive field, and maximization of computational utilization.

The UIB module replaces the bottleneck structure in the C3 module to build a new C3-MNV4(C3-MobileNetV4) module. This module effectively reduces the parameter count of the C3 module while enhancing its feature extraction ability, thereby reducing the computational burden and ensuring the accuracy of early forest fire detection. The structure of the fused C3-MNV4 is shown in

Figure 4.

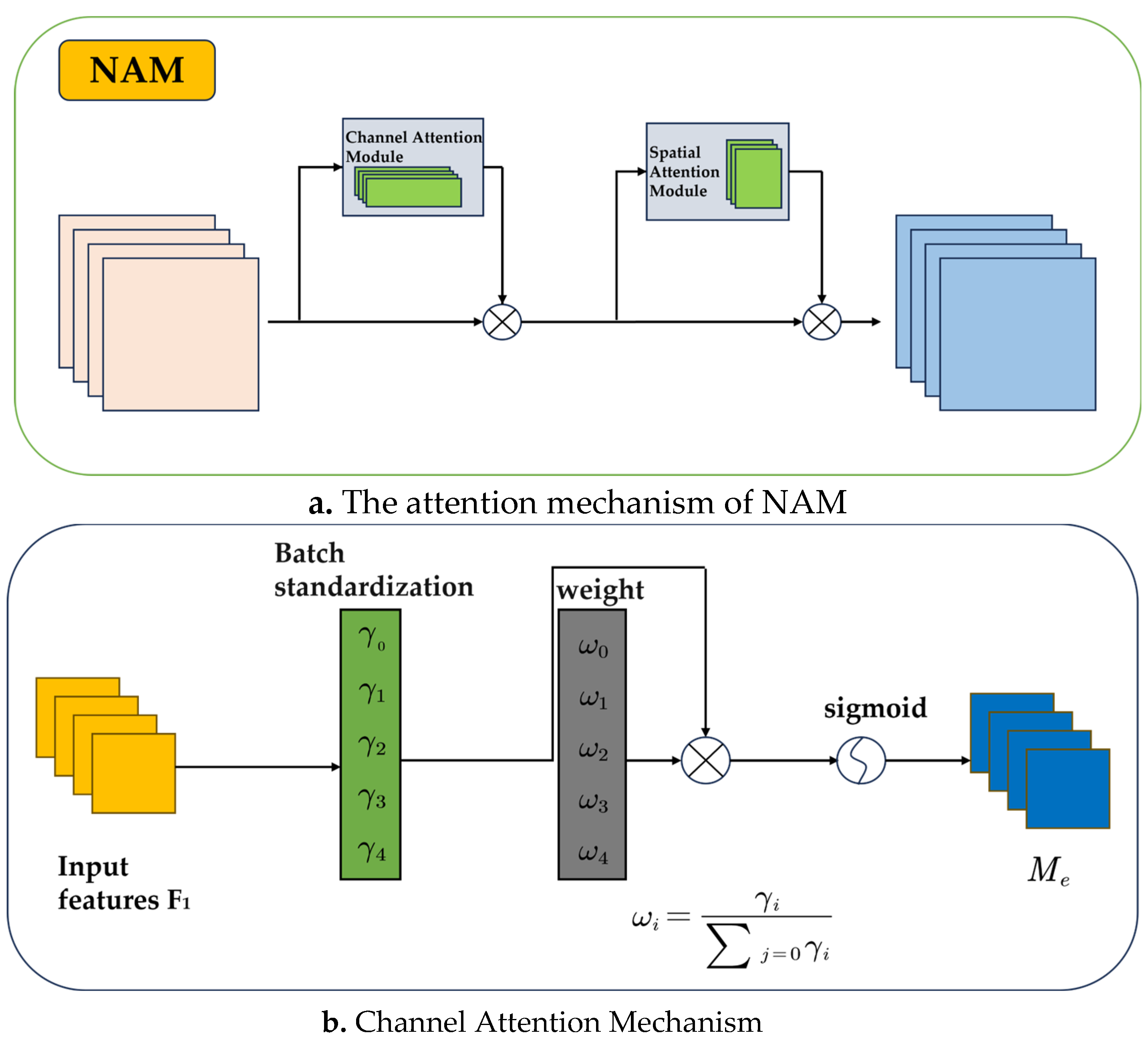

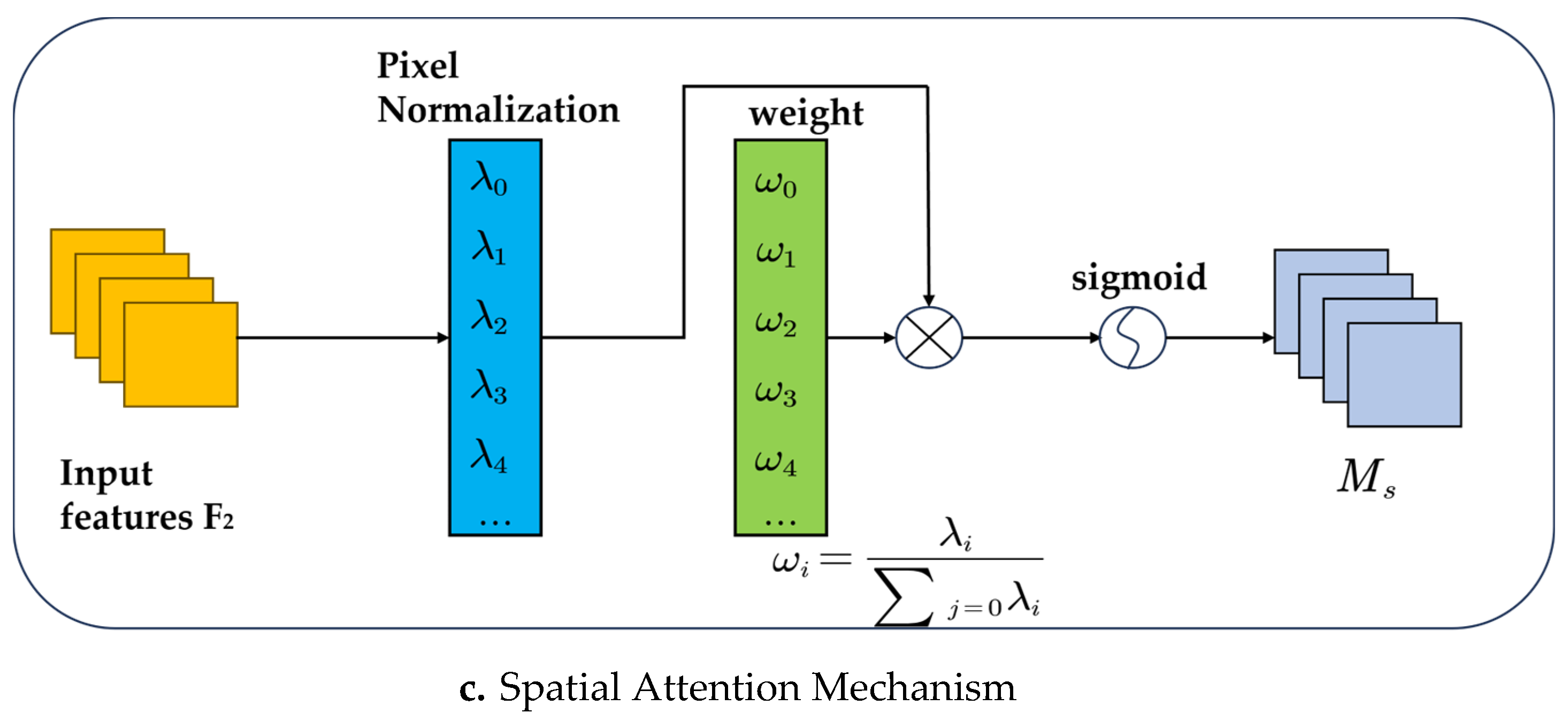

2.2.2. Introduction of the Attention Mechanism NAM

In the training process of neural networks, the attention mechanism plays a key role in suppressing less prominent features in both the channel and spatial dimensions. PrevIoUs research has mainly used attention operators for feature extraction, which can reveal feature information across different dimensions. The contribution factor of weights helps to suppress insignificant features, making the prominent features more noticeable. However, earlier methods did not consider this factor sufficiently. Thus, targeting the contribution factor of weights is an effective way to enhance the attention mechanism. This can be achieved by utilizing the scaling factor in Batch Normalization to represent the importance of the weights [

33]. This approach avoids the need to add extra fully connected or convolutional layers, as seen in methods like SE, BAM, and CBAM [

34].

Therefore, this study proposes a novel attention mechanism: Normalization-based Attention Mechanism (NAM) [

35]NAM is a lightweight attention mechanism that integrates the space and channel attention modules of CBAM, adjusting them to allow NAM to be embedded at the end of each network block. For residual networks, NAM can be incorporated at the end of the residual structure. In the channel attention submodule, the scaling factor from Batch Normalization is used, as shown in formula (1).

where

and

represent the input and output of the module, respectively, and

and

are the mean and standard deviation of the mini-batch

and

are trainable affine transformation parameters (scale and shift). The scaling factor shows the degree of change in each channel’s information and reflects the importance of each channel [

36].

Specifically, a larger variance indicates more significant changes in the channel, meaning it contains more useful information and therefore has more importance. On the other hand, channels with small variance change less and contain less information, thus they are less important. The channel attention mechanism is shown in

Figure 5.b. and expressed in formula (2).

where

is the output feature and

is the weight. For the spatial dimension, a Batch Normalization scaling factor is applied to measure pixel importance, which is referred to as pixel normalization. The spatial attention mechanism is shown in

Figure 5.c. and expressed in formula (3).

where

is the output feature,

is the scaling factor, and

is the weight.

Formula (4) introduces a regularization term into the loss function to suppress insignificant weights, where is the input, is the output, is the network weights, is the loss function, and is the -norm penalty function. The parameter balances the penalties of and

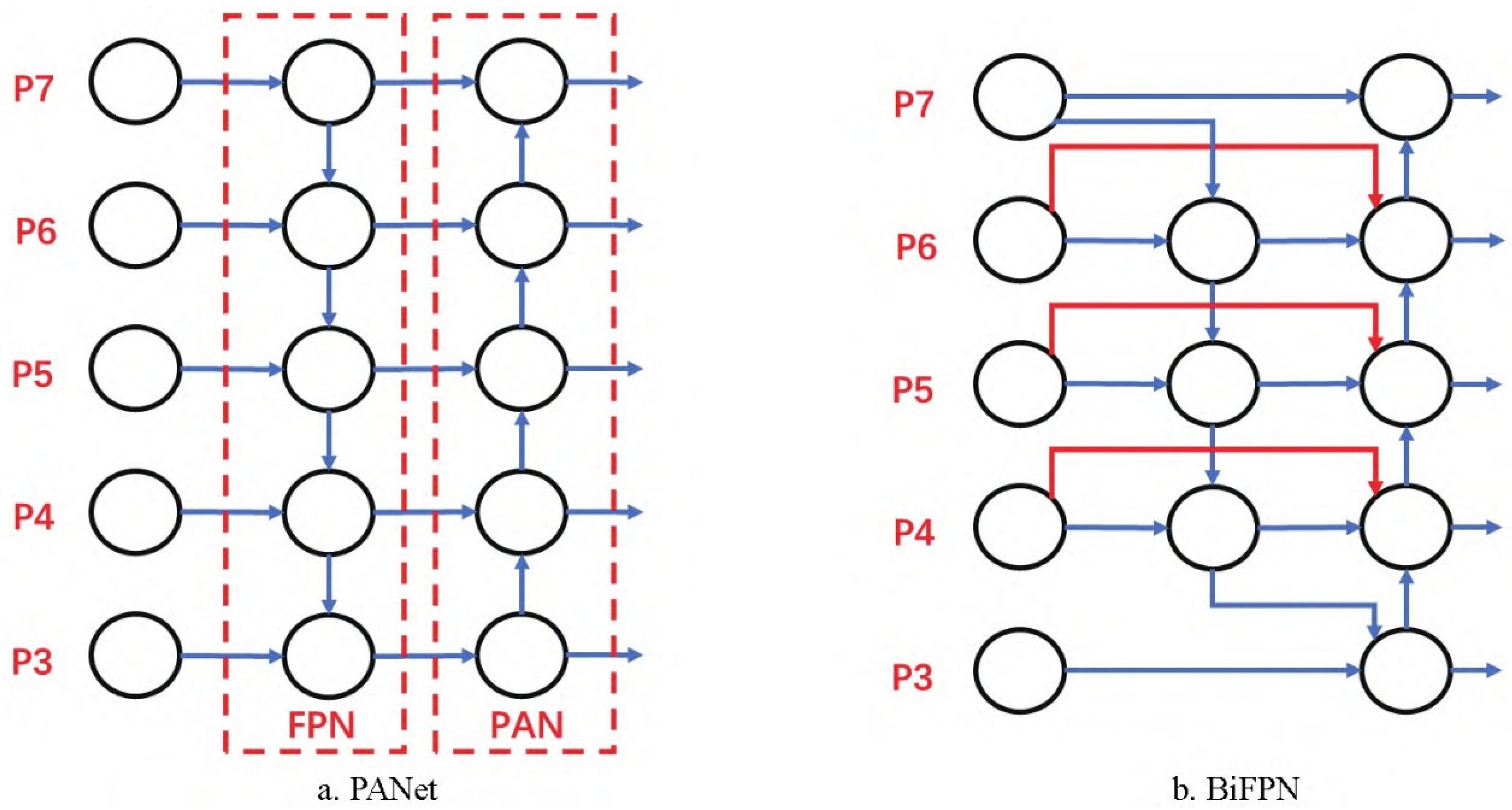

2.2.3. Bidirectional Characteristic Pyramid Network (BiFPN)

BiFPN (Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network) [

37] is an efficient multi-scale feature fusion architecture, which is further optimized on the basis of the PANet structure that fuses FPN (Feature Pyramid Network) [

38] and PAN (Path Aggregation Network). The structural design of BiFPN and PANet is shown in

Figure 6.

In the PANet architecture, the FPN structure transmits the strong semantic information from the top layer to the bottom layer through the top-down upsampling operation, while the PAN structure transmits the position information from the bottom layer to the top layer through the bottom-up downsampling operation. This combination method enables the parameter aggregation of features of different detection layers, so that the feature maps of different sizes contain both semantic information and position information of the image. BiFPN is optimized and improved on the basis of PANet. It not only retains the advantages of bidirectional connection and allows information fusion between features of different scales, but also introduces a weighted feature fusion mechanism. This mechanism enables the network to pay more attention to features with a larger amount of information, so as to improve the efficiency and effect of feature fusion. In addition, BiFPN removes nodes with only one input, adds connections between input and output nodes at the same level, and treats each bidirectional path as a network feature layer to optimize cross-scale connections. These improvements make BiFPN more structurally lean and significantly improve the network's ability to handle targets of different sizes and complexity.

In this study, small flames and smoke were used as detection targets. Due to the great difference in features between the two, the BiFPN structure can be used to replace the original PANet structure in the neck of YOLOv5s, which can better realize multi-scale feature fusion and improve the processing ability of different detection targets. This not only improves the accuracy of detection, but also reduces the weight of the network model.

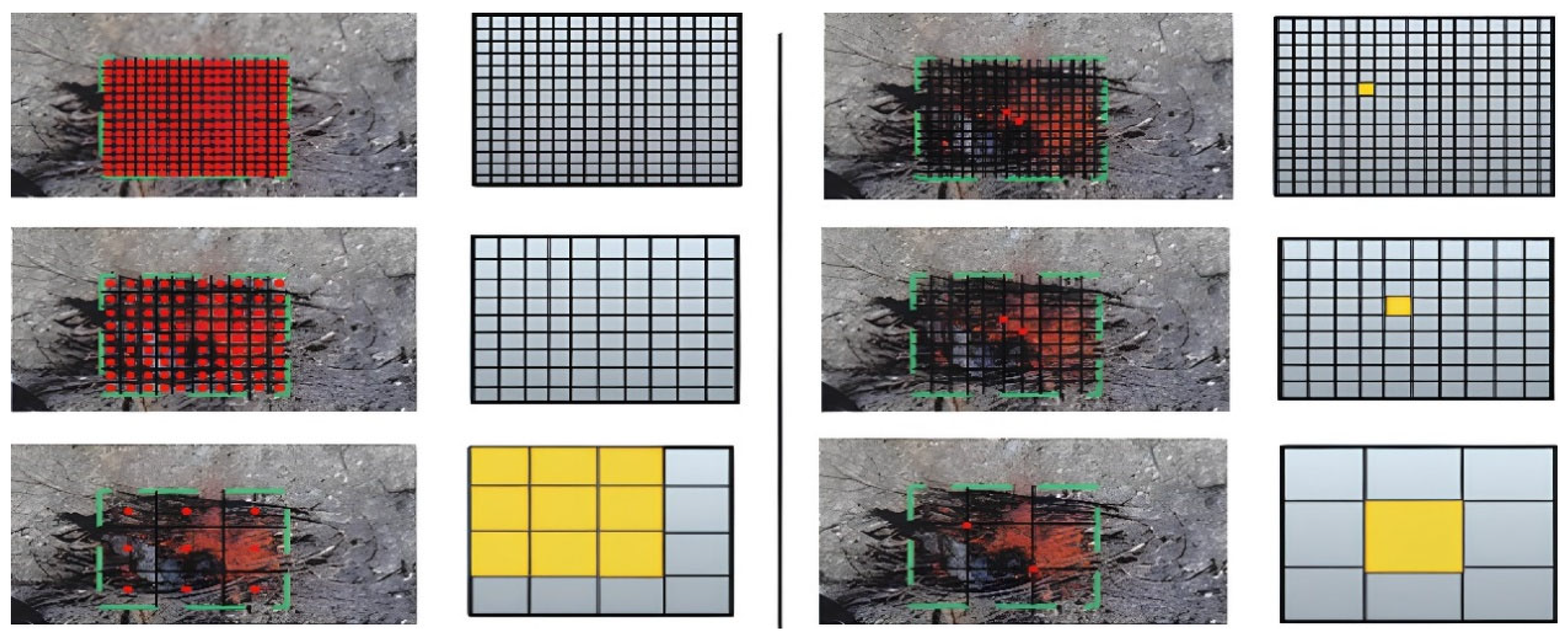

2.2.4. ObjectBox Detector

In the YOLOv5s model, the object detection head consists of three detectors, which use the grid-based anchor mechanism to achieve object detection through multi-scale feature maps. In the experiment, when the input image size is 640×640, the network will output three feature maps of different scales, 80×80, 40×40 and 20×20. Among them, the feature map of 80×80 is a shallow feature, which contains more low-level target information and is suitable for detecting small targets, so a small-scale anchor is configured. The feature map of 20×20 represents deep features and contains more high-level information, such as contours and structures, which is suitable for detecting large targets, so large-scale anchors are configured. The characteristic map of 40×40 is used to detect medium-sized targets.

However, this study proposes an innovative single-stage anchor-free and highly versatile object detection method, ObjectBox [

39]. Unlike traditional anchor-free detectors, existing methods are usually biased towards targets of a specific scale in label assignment. Whereas, ObjectBox relies only on the central position of the target as a positive sample and treats all targets equally at all feature levels, regardless of size or shape. The traditional anchor-free method first looks for candidate positive samples in a certain area through spatial and scale constraints, and then selects positive samples according to the scale, but this method has certain limitations because it ignores the situation that different size and shape targets may lead to different target boxes.

In contrast, the ObjectBox method proposed in this study proposes a fairer treatment by regressing only from the center of the target. To achieve this, we define the regression target as the distance from the two corners containing the target center grid element to the bounding box boundary.

Figure 7. illustrates how the original Anchor-free detector works with the ObjectBox detector in this study: the latter extends the range of positive samples by regressing only from the central position.

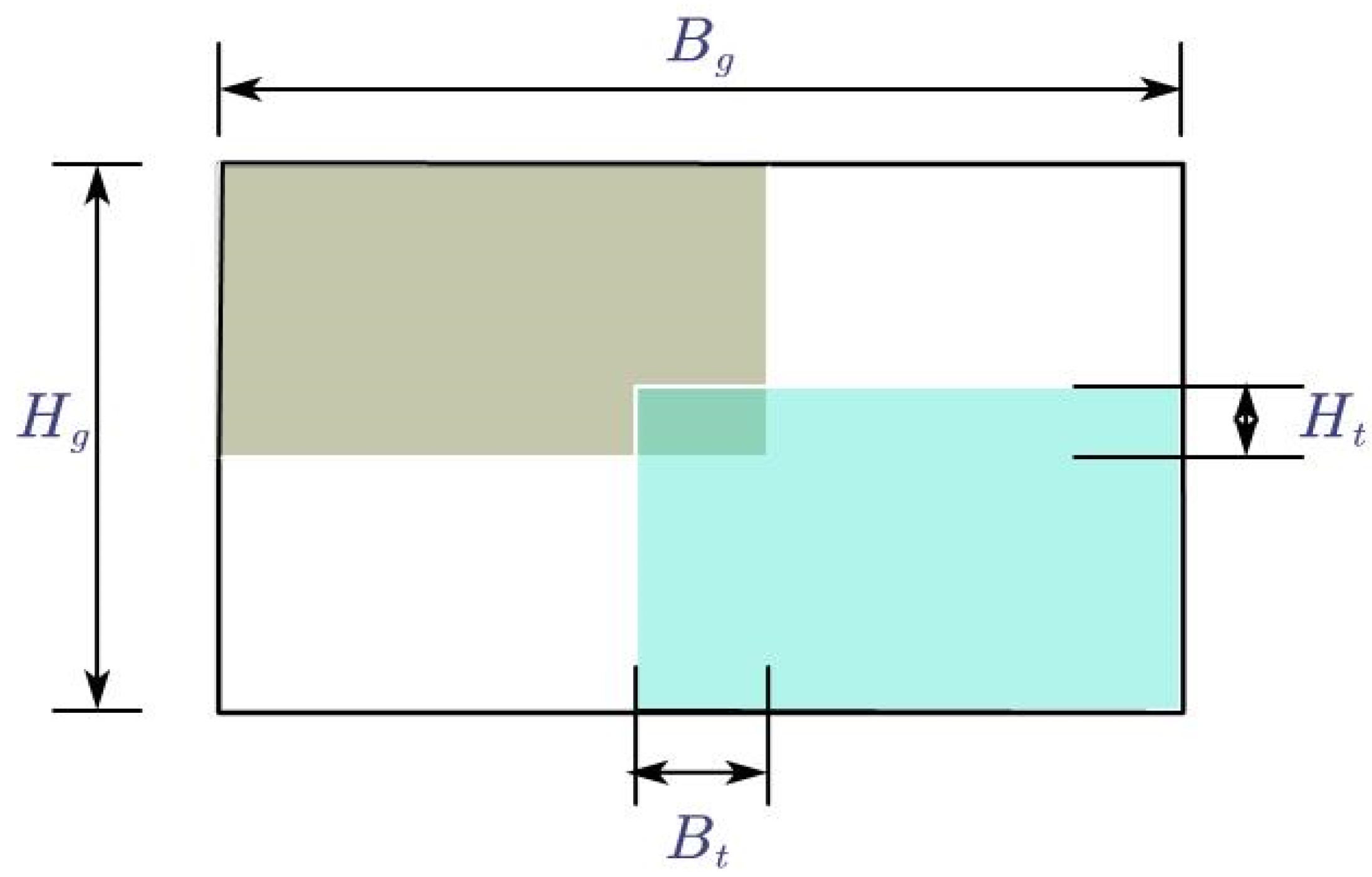

2.2.5. Optimize the Loss Function

The loss function is an important tool to measure the difference or error between the predicted output of the model and the actual target. Although the existing GIoU (Generalized Intersection over Union) loss function can calculate IoU (Intersection over Union) at a broader level, it cannot accurately reflect the actual situation when dealing with the inclusion relationship between the two prediction frames, resulting in the degradation of GIoU into an ordinary IoU indicator [

40]. In addition, GIoU needs to calculate the minimum bounding box for each prediction box and the real box, which not only increases the computational complexity, but also limits the convergence speed of the loss function.

In order to solve these problems, the improved network adopts the Adaptive Focus Intersection over Union (AF-IoU) loss function. AF-IoU significantly improves the generalization ability of the model by reducing the weight of position information when the anchor frame coincides with the target frame, reducing the interference in the pre-training process. As a bounding box regression loss, AF-IoU introduces a dynamic non-monotonic mechanism, and designs a reasonable gradient gain allocation strategy, which effectively avoids the large gradient or harmful gradient that may occur in extreme samples. The AF-IoU of bounding box regression is shown in

Figure 6 and is calculated as follows:

where r is the gradient gain, β is the non-monotonic focusing coefficient, and the α and δ are hyperparameters. (x,y) is the coordinate of the center point of the prediction box, (x

gt,y

gt) is the coordinate of the center point of the target box, Bg is the width of the union of the prediction box and the target box, and Hg is the height of the union of the prediction box and the target box.

RIoU is used to amplify the weight of the ordinary mass anchor frame, so that the model pays more attention to the anchor frame with low overlap between the prediction frame and the target box. LIoU is used to reduce the weight of high-quality anchor frames and reduce the attention to the distance between the center points when the overlap between the prediction box and the target box is high. In addition, by separating Bg and Hg from the computational plot, it is possible to prevent RIoU from creating gradients that hinder convergence. As shown in

Figure 8.

Since LIoU is dynamic, the quality classification criteria of the anchor frame also changes dynamically, which enables AF-IoUv3 to flexibly adjust the gradient gain allocation strategy according to the current training situation, so as to effectively improve the overall performance of object detection.

3. Experiments and Analysis of Results

3.1. Test Conditions and Indicators

In this experiment, the AutoDL server was used for the training of the early forest fire detection model, and the mirror environment chosen was PyTorch 1.11.0, Cuda 11.3, the programming language was Python 3.8 (ubuntu20.04), and the hardware configuration consisted of an RTX4060 GPU (8 GB) and 8 GB of RAM. The input image size for model training is 640 × 640, the number of training rounds is 300, the initial learning rate is 0.01, and the optimizer uses Adam. In the study of early forest fire detection based on aerial visible images, in addition to ensuring detection accuracy, this paper considers embedding the detection model into the UAV platform and optimizing the model by lightweighting it to increase the computational speed, so as to ensure that real-time processing of detection information.

In cases of imbalanced samples, using accuracy alone as a metric for model evaluation does not fully reflect the model's performance. Moreover, since both flame and smoke features are considered as detection targets in this study, we evaluate the model’s accuracy in early wildfire detection using three metrics: Precision (P), Recall (R), and Mean Average Precision (mAP).

To assess whether the detection model achieves lightweight optimization, the frames per second (FPS) may vary depending on the computer’s performance. Therefore, this study uses the number of model parameters (Params) and floating-point operations (FLOPs) to evaluate the model's lightweight nature and real-time performance. The formulas for Precision (P), Recall (R), and Mean Average Precision (mAP) are as follows:

Where is the number of true positive samples correctly predicted by the model, is the number of false positives (negative samples predicted as positive), and is the number of false negatives (positive samples predicted as negative).

3.2. Comparative Experiments

In order to verify the advantages of the optimized YOLOv5s model in early forest fire detection, this paper uses the same experimental conditions on a self-constructed early forest fire dataset and compares it with YOLOv3 Tiny [

41], YOLOv8, and YOLOXs [

42] proposed in similar studies. The experimental results are shown in

Table 2.

From

Table 2, it can be found that the YOLOv3-Tiny model is better than YO-LO-UFS in terms of lightweight, but its accuracy in early forest fire detection is reduced. Compared with YOLOv5s, YOLOv8 increased the mAP value of early forest fire detection by 3.5%, but its number of parameters and floating-point operations were much higher than those of YOLO-UFS. However, the YOLOXs model proposed in other similar studies can only detect flame targets, and its number of parameters and floating-point operations are higher than those of the detection model proposed in this study. In contrast, the YOLO-UFS model in this study outperforms other YOLO algorithms in terms of accuracy and lightweight. This suggests that the YOLO-UFS model in this study has an advantage when working with visible images from a bird's eye view. If it is applied to the UAV platform, the detection information can be processed more efficiently and the real-time detection can be ensured. In order to further verify the robustness of the detection network structure, forest fire experiments in other periods will be carried out in the future to evaluate its application in real scenarios.

3.3. Ablation Experiments

In order to verify whether the YOLO-UFS network structure can be improved by introducing ObjectBox, BiFPN, NAM, AF-Loss and C3-MNV4, making the model lighter and improving the accuracy and real-time accuracy of early detection of forest fires, we carried out ablation experiments on the self-built forest fire early dataset. The results of the experiment are shown in

Table 3. Among them, the first set of experiments was tested based on the original model of YOLOv5s; For each optimization method, experiments from groups 2 to 6 were tested separately. Groups 7 to 12 were tested by combining some optimization methods. Group 13 experiments were tested by applying all optimization methods simultaneously.

According to the data analysis in

Table 5, ObjectBox and BiFPN can improve the accuracy of early forest fire detection, significantly reduce the number of parameters and floating-point arithmetic of the model, and successfully achieve the lightness of the network model. While AF Loss has no direct effect on the lightness of the model, they effectively improve the accuracy of detection. Specifically, compared with the original model, the accuracy of ObjectBox and BiFPN has decreased, but the recall rate and average accuracy have been significantly improved, and the C3-MNV4 module reduces the number of parameters while enhancing its feature extraction ability to ensure the accuracy of early forest fire detection. NAM Attention enhances the detection of network models in noisy environments. In the field of early detection of forest fires, it is important to follow the principle of "false positive and false detection is better than false detection". Therefore, maximizing recall while ensuring accuracy is key. mAP is used as an evaluation metric that takes into account accuracy and recall, which means that the overall accuracy rate is improved.

By comparing the 7th and 12th group trials, it can be found that there are significant differences in the accuracy, recall, and mAP improvement ability of different optimization methods. The results of the fusion of the four optimization methods provide a good balance between precision, recall, and mAP. Compared to the original model, the accuracy (P) is improved by 3.8%, the recall (R) is increased by 4.1%, the average accuracy (mAP) is increased by 3.2 %, the floating point arithmetic (FLoPs) is reduced by 74.7%, and the number of parameters is reduced by 78.3%. The results show that the optimization method proposed in this paper can not only ensure the accuracy, but also realize the lightweight of the early detection model of forest fires, and improve the recall rate as much as possible under the premise of ensuring accuracy.

3.4. Generalization Experiment

3.4.1. Generalization Comparison Experiments

In order to further verify the generalization of the improved algorithm, the network models YOLOv3, YOLOv4, YOLOv5, YOLOv7 and YOLOX under other fire stage configurations in the public dataset environment are compared with the proposed algorithm. In the experiment, all five networks use the same loss function, LCIoU, to ensure the accuracy of the experimental results. In addition, the evaluation indicators of the comparative test still follow the above index system.

As shown in

Table 3, the YOLO-UFS network model shows obvIoUs advantages over other network models in forest fire detection tasks. Compared with the YOLOv5s model, the mAP value is increased by 3 percentage points, which is of great significance in practical applications. Compared to YOLOv7, YOLO-UFS has an mAP value that is about 3.6 percentage points higher, while its advantage over YOLOX is even more obvIoUs, with an mAP value that is about 6.3 percentage points higher.

The results of these comparative experiments strongly show that YOLO-UFS has better results in identifying forest fires, complex environments, low latency, and small targets. These characteristics also correspond to those of early forest fires (see

Table 4 for detailed data).

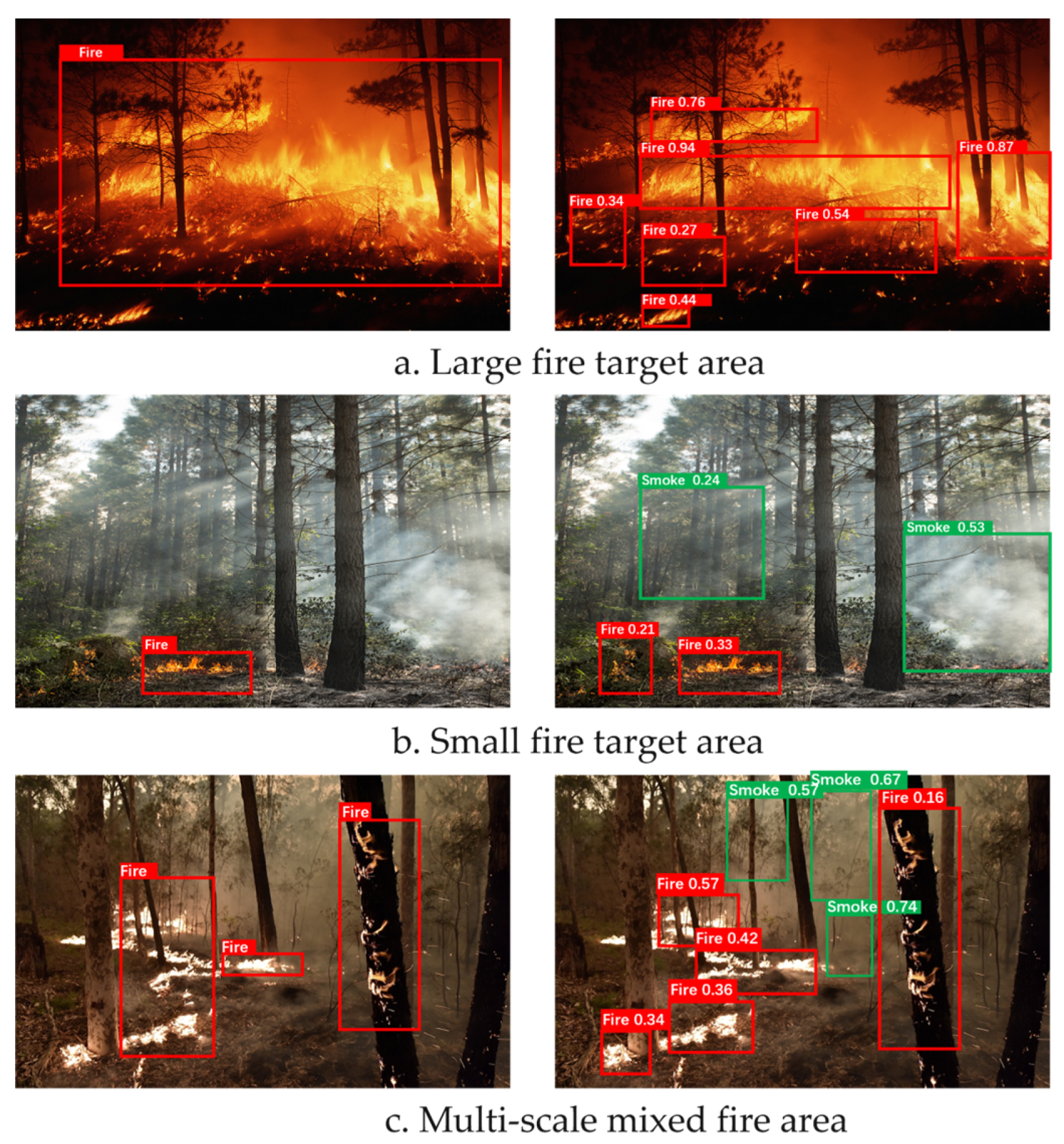

The detection effect of the YOLO-UFS model on forest fire data samples is shown in

Figure 9. From the figure, it can be clearly seen that the model is able to accurately perform the recognition operation when facing targets of different scales and shapes. This indicates that the YOLO-UFS model not only outperforms other similar models in terms of performance indexes, but also can better cope with a variety of complex detection scenarios in the actual forest fire detection task, which provides a stronger technical support for the early warning and rapid response of forest fire.

3.4.2. Generalized Ablation Experiments

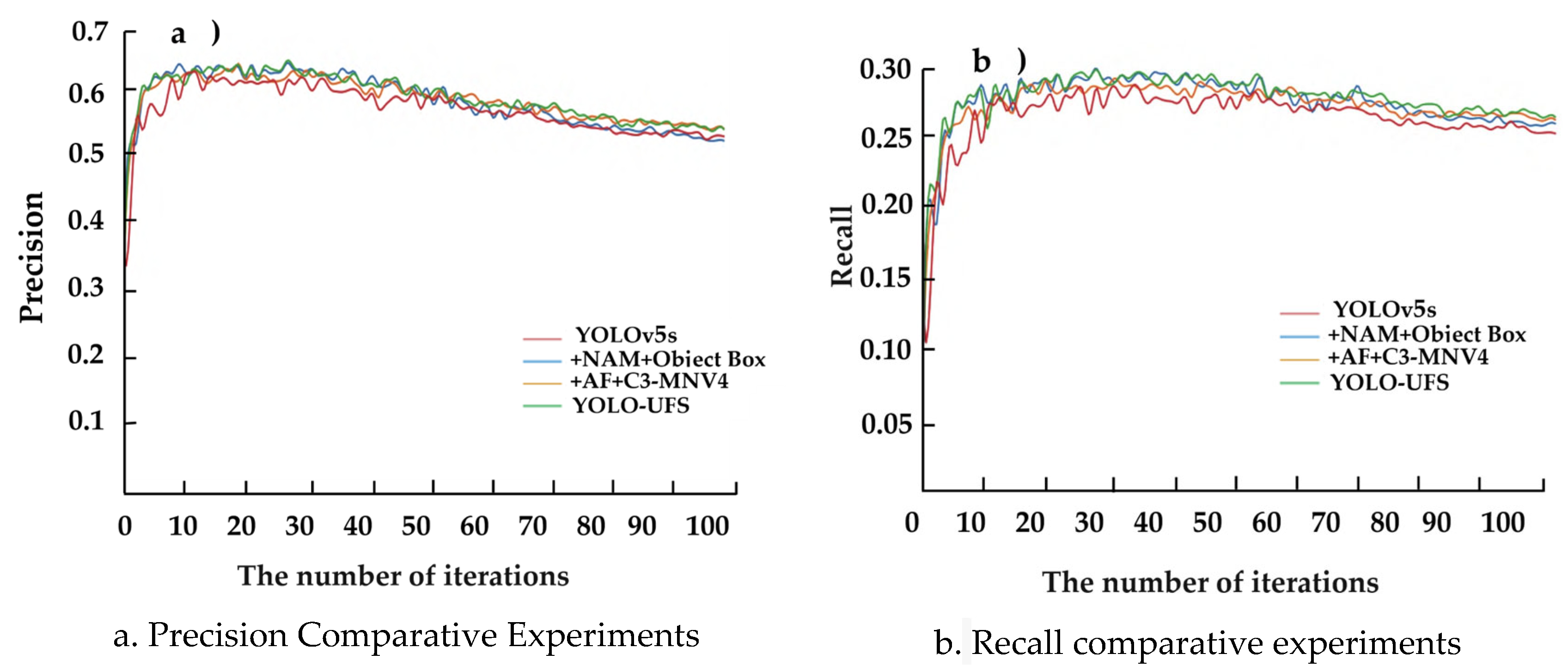

When generalized ablation experiments were performed using publicly available datasets, the accuracy and recall results of YOLO-UFS and different modules as a function of the number of iterations were shown in

Figure 10.

The inspection accuracy reflects the proportion of targets that the model actually correctly predicts to be positive, and higher values indicate that the model is more accurate in judging positive samples during the identification process, and can filter out relevant targets more effectively, thereby improving the relevance of the results. The full detection rate (i.e., recall) focuses on the proportion of all true positive targets correctly predicted by the model, which intuitively reflects the degree to which the model covers the positive samples, and the higher the value, the true target in the im-age is successfully identified.

As can be seen in

Figure 10a, the YOLO⁃UFS model outperforms YOLOv5s; As can be seen from

Figure 10b, several models rise very rapidly before 3 epochs, first falling rapidly between 3~7 epochs, and then showing an upward trend. Specifically, the combination of C3-MNV4 and AF-lou loss function is mainly responsible for reducing the amount of data and improving precision, but the improvement on the recall is also better than that of the baseline algorithm, while the improvement of NAM attention and ObjectBox on the recall is more bvious, and the conclusion of the complete YOLO⁃UFS model training under the public dataset is basically the same as that of the self-built dataset. The improved generalization ability and the multi-environment applicability of the algorithm are demonstrated.

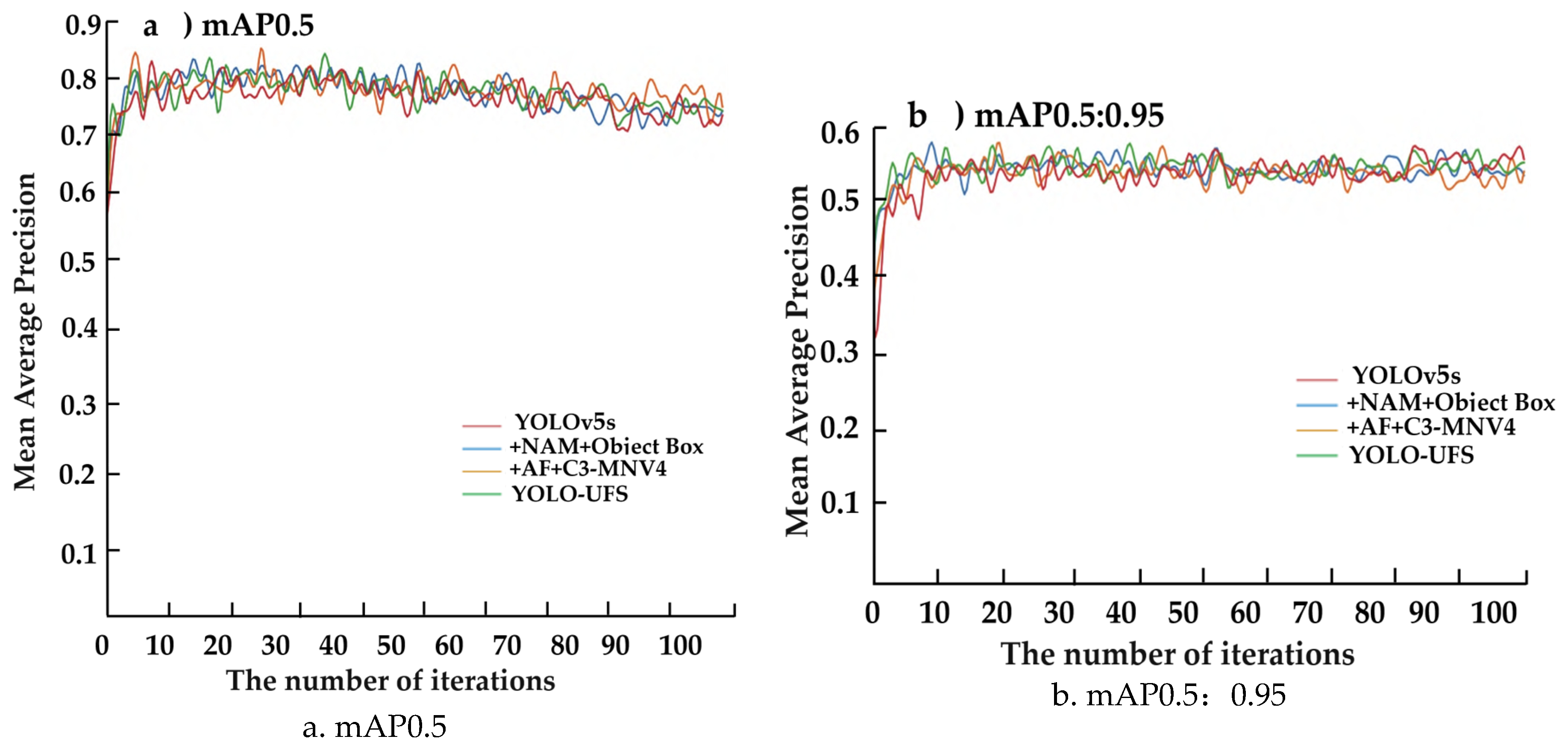

The mAP trend obtained by each algorithm in the public experimental dataset is shown in

Figure 11, where 0.50 and 0.95 are threshold settings, and the mAP value represents the average accuracy value of the average calculation of all classified targets, and the mAP value of the model shows an upward trend in general, and the mAP value of the model is also increasing with the optimization of the model, mAP0.5 has increased from 85.2% of the original model to 86.3%, and the value of mAP0.5:0.95 has also increased from the initial 56.7% That's 57.9 percent. The YOLOv5s model is being optimized step by step; The mean average accuracy has improved significantly. Then, on the premise of ensuring that the loss function is the initial function of YOLOv5s, the data augmentation mode of the network is changed, and it is found that the baseline model uses the Mixup data augmentation method less effectively, but after changing the An⁃chor⁃free mode of the original network and using a more accurate ObjectBox detector and NAM attention mechanism, the experimental evaluation index is more obviously. The experimental results showed that the total mAP value increased by 3.3%.

In summary, the replacement of the C3 module, the data augmentation method, the fixed change loss function, and the unanchored frame detector adopted in this experiment have good results in forest fire detection, and the improvement of the experiment has a strong pertinence, and the detection effect is significant when the drone shoots the environment, showing the excellent performance of the model in dealing with different target environments.

4. Visual Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Visual Analysis and Shortcomings

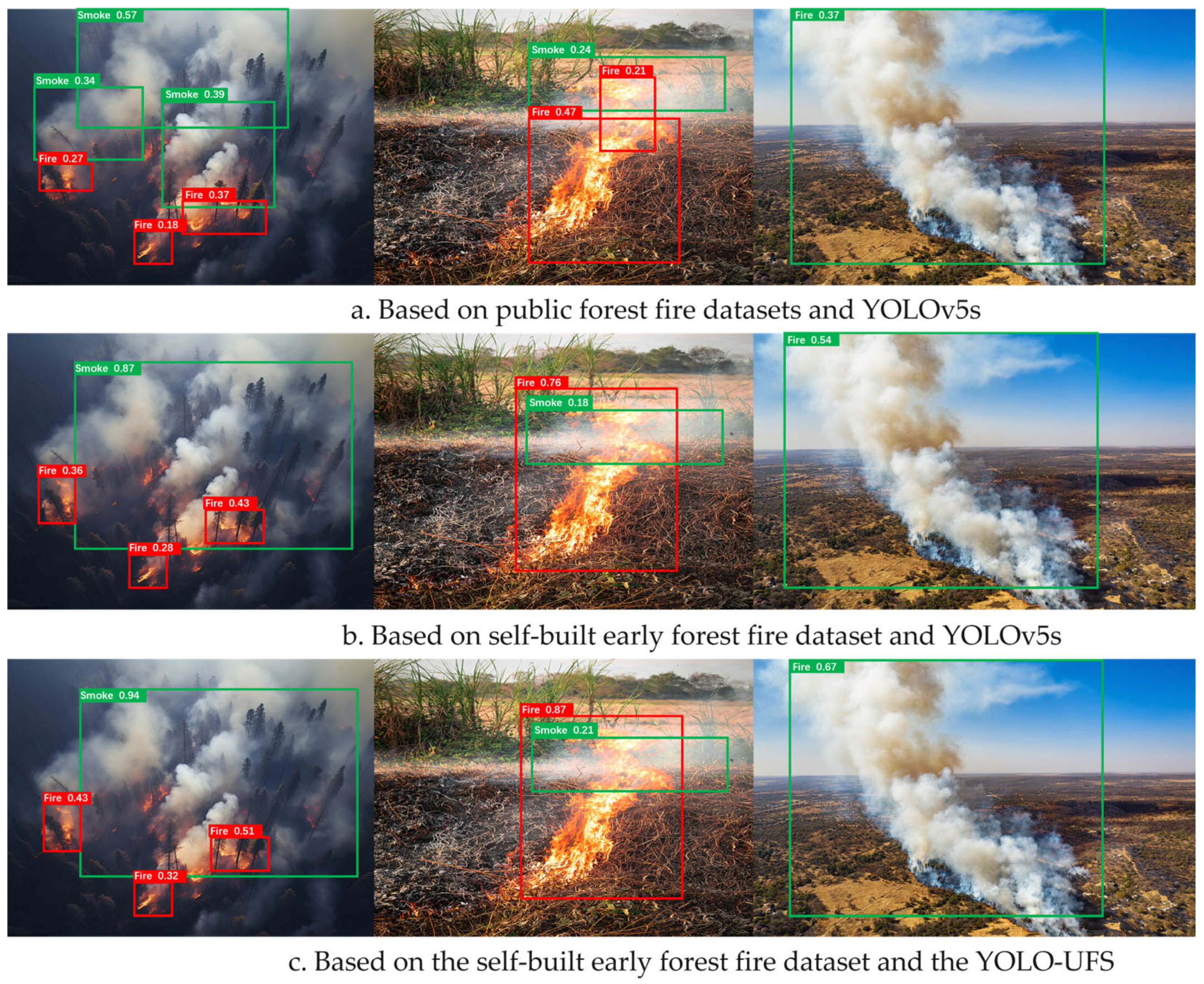

In this experiment, we conducted an in-depth comparative analysis of three different detection models. The three models are an open flame detection model based on the open flame dataset and YOLOv5s, an early forest fire detection model based on the self-built early forest fire dataset and YOLOv5s, and an early forest fire detection model based on the self-built early forest fire dataset and YOLO-UFS. A closer look at the visualization results in

Figure 12 shows that although all three models exhibit high accuracy in the detection task of flame and smoke targets, the optimized early forest fire detection model in this study performs particularly well on several key performance indicators. In particular, in terms of confidence, the model shows a significant advantage in identifying relevant targets for early forest fires with a higher level of confidence. At the same time, it effectively reduces the phenomenon of duplicate detection, which fundamentally improves the accuracy and reliability of detection. In addition, compared with the self-built dataset and the model trained on the public dataset, the optimized model has stronger performance in target directionality, and shows a higher sensitivity to the typical feature of early forest fires, "big smoke and small fire", and can more keenly capture this key feature, so as to send out early warning signals in time in the early stage of fires.

4.2. Discussion of Future Work

Despite the significant breakthroughs in accuracy and recall of the model, we must also be aware that there are still some shortcomings when using public datasets for testing. This indicates that the current model may still have some limitations when dealing with diverse and complex practical scenarios. Therefore, future research work should further optimize the model architecture and actively expand the scale and diversity of datasets. By introducing more real-world scene data, the model will be able to better learn the fire characteristics in different environments, thereby further improving its detection performance and adaptability in the real world.

Looking to the future, research on forest fire detection will focus on four main directions to meet the high standards of comprehensive coverage and zero false negatives. First, by integrating infrared sensors (for precise detection of flames and high-temperature areas) with multispectral sensors (for analyzing smoke spectral characteristics) , a multidimensional perception system will be constructed to overcome the limitations of single visible light data. Second, lightweight model architectures will be adopted, incorporating attention mechanisms and adaptive data augmentation techniques to improve the detection accuracy of small targets while reducing inference time by 30%. Model compression algorithms will be optimized in parallel to ensure that the model can achieve real-time analysis capabilities of 25 frames per second on drone edge devices. Finally, a large-scale, cross-regional, and multi-meteorological condition annotated dataset with millions of entries will be developed. Through fine-grained labeling, the model's generalization performance in complex forest areas will be enhanced, ultimately building an integrated early warning system for" precise perception—rapid response—round-the-clock monitoring."

5. Conclusion

This study explores the early detection of forest fires using drones and deep learning techniques. A high-quality dataset for early forest fire detection was created through aerial image analysis, which provided strong data support for model training. YOLO-UFS is proposed by improving the YOLOv5s network model, which optimizes several of its functions, including BiFPN, novel loss function, anchor-free detector, and NAM attention mechanism. These improvements improved the model's mAP value for early forest fire detection to 91.3%, striking a balance between accuracy and real-time performance. Compared with the original model, the accuracy, recall and average accuracy of the improved YOLOv5s model are increased by 3.8%, 4.1% and 3.2%, respectively, and the amount of floating-point operations and parameters are reduced by 74.7% and 78.3%, respectively, and the performance is also better than that of other mainstream algorithms of the YOLO series. And it is more lightweight, and the low latency means that it is more likely to be deployed on drone platforms. For other phases of forest fires, mAP0.5 increased from 85.2% to 86.3%, mAP0.5:0.95 increased from 56.7% to 57.9%, and the overall mAP value increased by 3.3 percentage points. Experimental results show that YOLO-UFS is superior to other object detection methods, providing higher accuracy with fewer parameters. This makes YOLO-UFS a more practical and effective solution for real-time forest fire detection on airborne platforms. This study provides effective data and methodological support for early forest fire detection using aerial horizon. Future work can explore a number of avenues to further improve detection reliability. First, improving datasets remains a challenge. Adversarial networks (GANs) can be generated, which can be used to generate synthetic, but photorealistic images of fires to expand the dataset. In addition, we will explore innovative integration techniques to seamlessly integrate additional sensor data into the inspection system, combined with a human verification process to improve accuracy and minimize resource consumption.

Author Contributions

The conceptualization of the study was carried out by Z.L., H.X., and Z.J. The methodology was developed by Z.L. and H.X., while the software was handled by Z.L. ,C.C. and C.Z. Validation was performed by H.X. and Z.J., and formal analysis was conducted by H.X., Z.L., and Z.J. The investigation was led by C.Z., H.X., and Z.J., with resources provided by Z.L. C.C. and H.X. Data curation was managed by C.Z. and H.X. The original draft preparation was carried out by Z.L. ,C.C. and H.X. and the writing—review and editing was completed by Z.L., H.X., and C.Z. Visualization was done by C.Z., Z.J., and Z.L. Supervision was provided by H.X., and C.C project administration was managed by Z.L. Funding acquisition was also secured by Z.L. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the University Student Innovation Training Program (National Level) of China, grant numbers 202410225290, and the Heilongjiang Northeast Forestry University Innovation Program, Open Funding Item No. 0824.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions of this study are incorporated into the article. For further inquiries, please contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- CUI, R. K., QIAN, L. H., & WANG, Q. H. (2023). Research progress on fire protection function evaluation of forest road network. World Forestry Research, 36(6), 32-37.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2024). Statistical Bulletin of the People’s Republic of China on National Economic and Social Development for 2023 [EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202402/t20240228_1947915.html.

- ABID, F. (2021). A survey of machine learning algorithms based forest fires prediction and detection systems. Fire Technology, 57, 559-590.

- ALKHATIB, A. A. A. (2014). A review on forest fire detection techniques. International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks, 10, 597368.

- CHUN, B., JIE, C., QUN, H., et al. (2023). Dual-YOLO architecture from infrared and visible images for object detection. Sensors, 23(6), 2934.

- ZHANG, S., GAO, D., LIN, H., et al. (2019). Wildfire detection using sound spectrum analysis based on the internet of things. Sensors, 19, 5093.

- LAI, X. L. (2015). Research and design of forest fire monitoring system based on data fusion and Iradium communication [D]. Beijing: Beijing Forestry University.

- NAN, Y. L., ZHANG, H. C., ZHENG, J. Q., et al. (2021). Application of deep learning to forestry. World Forestry Research, 34(5), 87-90.

- YUAN, C., ZHANG, Y. M., & LIU, Z. X. (2015). A survey on technologies for automatic forest fire monitoring, detection, and fighting using unmanned aerial vehicles and remote sensing techniques. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 45(7), 783-792.

- HAN, Z. S., FAN, X. Q., FU, Q., et al. (2024). Multi-source information fusion target detection from the perspective of unmanned aerial vehicle. Systems Engineering and Electronic Technology. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.2422.tn.20240430.1210.003.

- PANAGIOTIS, B., PERIKLIS, P., KOSMAS, D., et al. (2020). A review on early forest fire detection systems using optical remote sensing. Sensors, 20(22), 6442.

- LI, D. (2023). The research on early forest fire detection algorithm based on deep learning [D]. Changsha: Central South University of Forestry & Technology.

- XUE, Z., LIN, H., & WANG, F. (2022). A small target forest fire detection model based on YOLOv5 improvement. Forests, 13(8), 1332.

- ZHAO, L., ZHI, L., ZHAO, C., et al. (2022). Fire-YOLO: A small target object detection method for fire inspection. Sustainability, 14(9), 4930.

- ZU, X. P. (2023). Research on forest fire smoke recognition method based on deep learning [D]. Harbin: Northeast Forestry University.

- SU, X. D., HU, J. X., CHENLIN, Z. T., et al. (2023). Fire image detection algorithm for UAV based on improved YOLOv5. Computer Measurement & Control, 31(5), 41-47.

- PI, J., LIU, Y. H., & LI, J. H. (2023). Research on lightweight forest fire detection algorithm based on YOLOv5s. Journal of Graphics, 44(1), 26-32.

- Zhang, Y., Li, Q., & Wang, H. (2024). YOLOv8-FFD: An Enhanced Deformable Convolution Network for Forest Fire Detection. *IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing*, 62, 5602715.

- Wang, X., Chen, Z., & Liu, Y. (2024). Visible-Infrared Cross-Modality Forest Fire Detection Using Dynamic Feature Fusion. *Remote Sensing*, 16(3), 521.

- Liu, J., Zhang, W., & Zhou, L. (2024). 3D-YOLOv5: A Height-Aware Network for Aerial Forest Fire Detection. *ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing*, 210, 1-15.

- Chen, K., Xu, M., & Huang, S. (2024). Swin-YOLO: Transformer-Based Adaptive Sparse Attention for Forest Fire Detection. *Expert Systems with Applications*, 238, 121731.

- Zhou, T., Wang, Q., & Li, X. (2025). 3D Localization of Forest Fires Using Neural Radiance Fields and Deep Learning. *Fire Technology*, 61(2), 789-806.

- Gupta, A., Sharma, P., & Kumar, R. (2025). EdgeFireNet: Neural Architecture Search for Real-Time Forest Fire Detection on Edge Devices. *IEEE Internet of Things Journal*, 12(5), 8012-8023.

- SUN X, SUN L, HUANG Y. (2020). Forest fire smoke recognition based on convolutional neural network [J]. Journal of Forestry Research, 32(5):1-7.

- LU K J, HUANG J W, LI J H, et al. MTL-FFDET: a multi task learning-based model for forest fire detection [J]. Forests, 2022,13(9):1448.

- PREMA C E, VINSLEY S S, SURESH S. Multi feature analysis of smoke in YUV color space for early forest fire detection [J]. Fire Technology,2016,52:1319-1342.

- XU Y Q, LI J M, ZHANG F Q. A UAV-based forest fire patrol path planning strategy [J]. Forests,2022,13:1952.

- Zu Xinping, Li Dan. (2022). Forest fire smoke recognition method based on UAV images and improved YOLOv3-SPP algorithm. Journal of Forestry Engineering, 7(5), 142-149. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. A., Liu, Y. Q., Gong, C. Y., et al. (2020). Applications of deep learning for dense scenes analysis in agriculture: A review. Sensors, 20(5), 1520. [CrossRef]

- Bu Huili, Fang Xianjin, Yang Gaoming. (2022). Object Detection Algorithm for Remote Sensing Images Based on Multi-dimensional Information Interaction. Journal of Heilongjiang Institute of Technology (Comprehensive Edition), 22(10), 58-65. [CrossRef]

- QIN D F, CHAS LEICHNER, MANOLIS DELAKIS, et al. MobilNetV4: universal models for the mobile ecosystem [J]. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:2404.10518.

- [MARK SANDLER, ANDREW HOWARD, ZHU M L, et al. (2018) MobileNetV2: inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks [C]. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, :4510-4520.

- Yang, Yu. (2022). Research on image data augmentation method based on generative adversarial network. Zhengzhou:Strategic Support Force Information Engineering University. [CrossRef]

- Xiu, Y., Zheng, X. Y., Sun, L. L., et al. (2022). FreMix: Frequency-based Mixup for data augmentation. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing, 2022, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. C., Shao, Z. R., Teng, Y. Y., et al. (2021). NAM: Normalization-based attention module. arXiv. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2111.12419.

- Yao Xiaokai. (2022). Research on airtight water inspection method of closed container based on deep separable convolutional neural network. Xi'an:Xijing University. [CrossRef]

- Tan, M. X., Pang, R. M., & Quoc, V. L. (2020). EfficientDet: Scalable and efficient object detection. In IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA (pp. 10781-10790).

- Liu, S., Qi, L., Qin, H. F., et al. (2018). Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA (pp. 8759-8768).

- Zand, M., Etemad, A., & Greenspan, M. (2022). ObjectBox: From centers to boxes for anchor-free object detection. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (pp. 390-406). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. [CrossRef]

- TONG Z J, CHEN Y H, XU Z W,et al. (2023) Wise-IoU:boun⁃T-box regression loss with dynamic focusing mechanism, 2023, 08-12.

- REDMON J, FARHADI A. Yolov3: An incremental improvement [J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.02767,2018.

- SU X D, HU J X, CHENLIN Z T, et al.( 2023) Fire image detection algorithm for UAV based on improved YOLOv5 [J]. Computer Measurement & Control, 31(5):41-47.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).