1. Introduction

Rapid progress in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) technology has facilitated its extensive utilization in various fields such as aerial photography, agricultural surveillance, space exploration, and others, due to its high precision, safety, and ability for large-scale surveys [

1,

2]. The images captured by UAVs show a wide coverage, reduced target dimensions, and versatile viewing perspectives, offering crucial technical support to identify key areas, provide assistance, and monitor hazardous regions [

3,

4]. As a result, UAV aerial image object detection presents significant potential in contemporary scientific research and practical applications. Deep learning-driven object detection surpasses conventional methods in accuracy, efficiency, and adaptability by enabling automated feature extraction, end-to-end optimization, and multiscale analysis, establishing itself as the predominant choice in both industrial applications (e.g., autonomous driving, security) and academia[

5,

6].Despite its heavy reliance on extensive datasets and computational resources, the benefits of this approach far outweigh those of traditional methods in most real-world situations. However, challenges persist in detecting small targets, as these objects occupy minimal image space, have lower resolution, and exhibit less distinct visual features. Similarly to human visual perception, where attention is naturally drawn to larger objects in images, object detectors tend to prioritize medium-to-large targets, leading to higher rates of missed and false detection for smaller objects[

7,

8]. Moreover, shallow layers in neural networks such as YOLOv8 can inadvertently filter out crucial spatial details necessary for detecting these small targets, resulting in data loss. Additionally, during the feature extraction process, small objects are at risk of being obscured by larger ones, leading to the loss of vital information required for accurate detection. Overcoming these obstacles is imperative for improving overall detection accuracy and reliability in practical applications.

Currently, the field of object detection is mainly dominated by two main methodologies: the two-stage models typified by the R-CNN series [

9,

10,

11], and the single-stage models exemplified by the YOLO series [

12,

13,

14]. Among the various iterations of YOLO, YOLOv8 has garnered attention because of its well-balanced performance in terms of accuracy and speed. Despite notable advancements in the detection of small targets, there are persistent challenges, particularly in aerial image analysis, such as missed detection and false positives. To address these issues, this study introduces the DCS-YOLOv8 algorithm, which is built upon the YOLOv8 framework.

This paper introduces several key innovations:

1) Dedicated Small Object Detection Layer (P2): To enhance the detection of small objects, a dedicated detection layer (P2) is integrated into the YOLOv8 model, specifically designed to capture fine details such as edges and textures, thus significantly improving detection accuracy.

2) DCS-Net Architecture: The DCAM is combined with the C2f module to create the C2f-DCAM structure. By incorporating the SCDown module, the DCS-Net serves as the foundational network for DCS-YOLOv8, enhancing both feature extraction capabilities and global contextual feature representation learning.

3) SDBIoU Loss Function: SDBIoU is proposed as a replacement for CIoU, allowing for dynamic adjustment of loss weights based on the scale of targets. This approach addresses challenges associated with traditional loss functions, such as handling label noise, scale sensitivity, and ensuring convergence stability.

4) Hardware Validation: The model is deployed on the RK3588 platform to achieve real-time small target detection, showcasing the practical efficacy of the proposed methodology in enhancing detection performance for real-world applications.

2. Related Work

Object detection is a fundamental undertaking in computer vision that involves the precise localization and classification of objects in images or videos through the delineation of bounding boxes. The detection of small targets, a prominent area of interest and complexity in this domain, poses a significant challenge due to their limited spatial extent, resulting in a reduced pixel footprint. This diminutive size leads to a sparsity of features following convolutional processes, thereby heightening the likelihood of overlooking these targets during detection.

Conventional approaches such as R-CNN [

10] and Fast R-CNN[

9] are constrained by utilizing single-scale feature maps, thereby restricting their detection efficacy. The introduction of the Region Proposal Network (RPN) in Faster R-CNN [

11] has addressed this limitation by automating the generation of candidate regions and sharing convolutional features among subsequent classification and regression networks. This innovation has led to enhancements in both speed and accuracy. However, YOLO encounters challenges in representing global contextual features due to its reliance on convolutional layers, which inherently capture local neighborhood information. While the integration of multiple convolutional layers can enlarge the receptive field, they fall short in establishing long-range pixel relationships, in contrast to the self-attention mechanisms in Transformers [

15,

16,

17,

18], which directly model global dependencies. Notably, YOLO may struggle to exploit contextual correlations for joint reasoning when objects are spatially distant in an image. Furthermore, YOLO’s partitioning of images into fixed grids (e.g., 7×7 or denser) results in a lack of global information sharing across predictions within these grids. Consequently, small targets confined to a few grids suffer from inadequate global context, leading to increased instances of missed or erroneous detection.

In UAV-acquired images, instances of dense crowds or significant occlusions are frequently encountered[

19,

20]. The absence of comprehensive global contextual analysis in YOLO poses challenges in delineating boundaries or relationships among intersecting objects. Additionally, aerial imagery commonly exhibits complex backgrounds. In cases where targets exhibit resemblances to the background in local features, YOLO’s dependence solely on local data renders it susceptible to disruptions, underscoring the potential benefits of integrating global context for enhanced discriminative insights.

In recent years, researchers globally have conducted extensive studies aimed at improving the accuracy of small target detection. For example, YOLOv3 [

21] was the first to introduce the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) [

22], facilitating multi-scale object detection and feature fusion, thereby significantly enhancing small target detection capabilities. Nevertheless, there remains limited global interaction across feature pyramid levels. The amalgamation of high-level semantic features (pertaining to large objects) and low-level detailed features (associated with small objects) primarily relies on rudimentary methods such as upsampling or concatenation, rather than globally optimized integration. Subsequent iterations such as YOLOv4 and YOLOv5 integrated the Path Aggregation Network (PAN) to establish a bidirectional feature pyramid (PAN-FPN), employing concatenation (in YOLOv4) or weighted fusion (in YOLOv5) to amalgamate multi-level features, thereby further enhancing the localization of small targets.Liu et al. [

23] integrated Transformers with YOLO by incorporating self-attention layers into either the backbone network or detection heads, explicitly capturing global dependencies. Wei et al. [

24] introduced Enhanced-YOLOv8, a novel model tailored for small target detection, which includes a specialized small target detection layer added to the original effective feature layers of YOLOv8. Expanding on the conventional Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM), they introduced a Position Attention Module (PAM) and a Fusion Convolutional Block Attention Module (FCBAM), in conjunction with a Semantic Fusion Network (SFN) based on residual networks, resulting in a substantial enhancement in detection accuracy. Xu et al. [

25] devised a small target detection algorithm for UAV images using an enhanced YOLOv8 model (YOLOv8-MPEB). This method replaces the CSPDarknet53 backbone with a lightweight MobileNetV3 backbone, integrates an Efficient Multi-scale Attention (EMA) mechanism into the C2f module, and incorporates a Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network (BiFPN) in the neck section. These adjustments effectively mitigate detection errors stemming from scale variations and complex scenes, thereby augmenting the model’s generalization capabilities.

Released by Ultralytics in 2023, YOLOv8 (You Only Look Once version 8)[

14] is a real-time object detection model known for its one-stage architecture, which allows for simultaneous object localization and classification in a single pass of the neural network, thereby significantly improving detection efficiency compared to its predecessor, YOLOv5. YOLOv8 introduces several key upgrades in architecture and functionality:

1. Enhanced Backbone: YOLOv8 features an improved CSPDarknet53 backbone that enhances gradient flow by replacing the C3 module in YOLOv5 with a C2f module, while still maintaining a lightweight design.

2. Anchor-Free Detection Head:YOLOv8 utilizes an anchor-free head that directly predicts object center points, simplifying training and enhancing accuracy in detecting small targets.

3. Decoupled Head: This model separates classification and bounding box regression tasks through a decoupled head, leading to improved training efficiency.

4. Varifocal Loss (VFL):YOLOv8 employs Varifocal Loss instead of traditional loss functions to improve robustness against class imbalance and noisy labels.

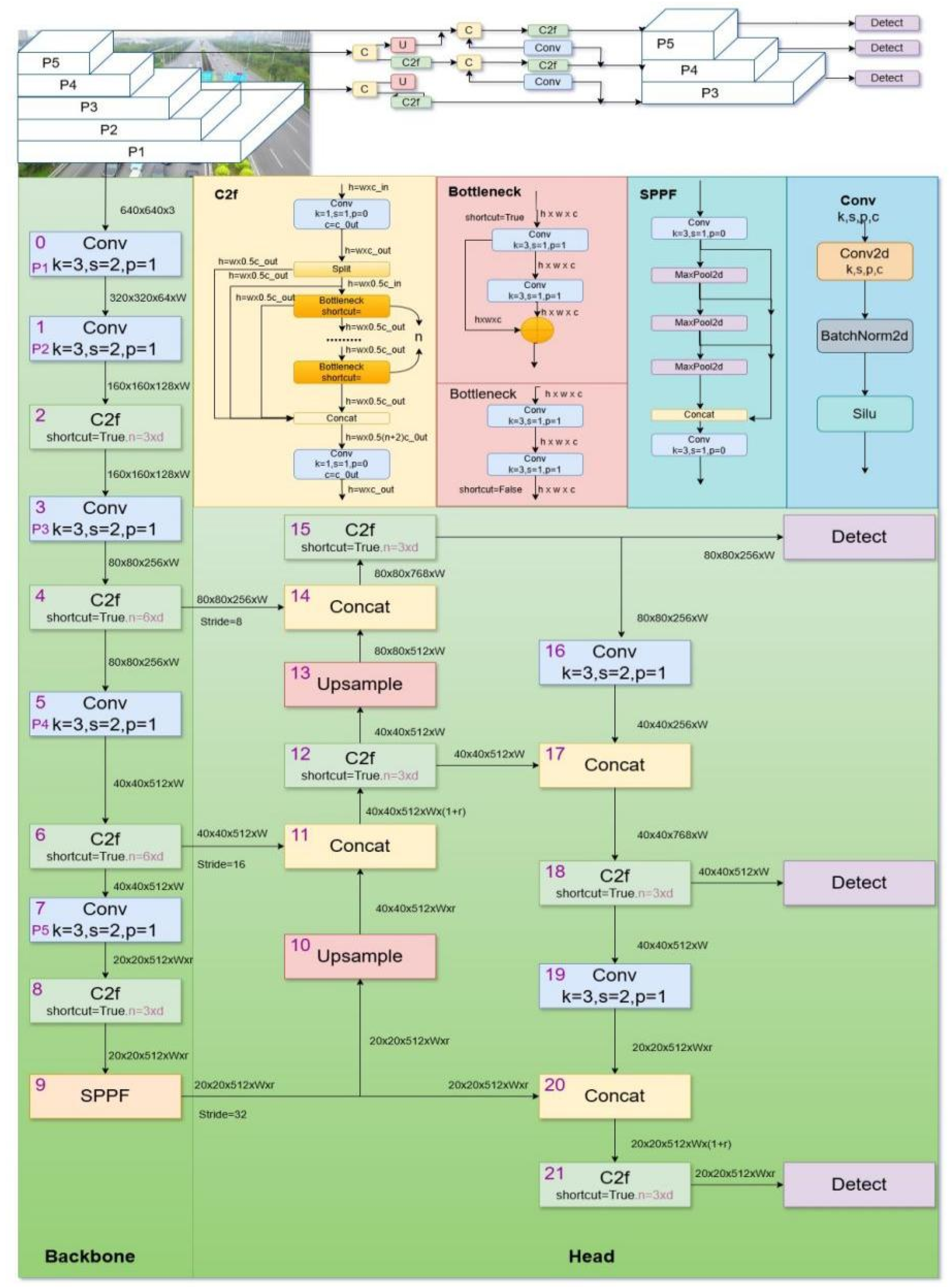

YOLOv8 is extensively utilized in various fields such as autonomous driving, medical imaging analysis, and security surveillance. It has emerged as a leading model in object detection due to enhancements in both architecture and algorithms. The model’s ability to achieve a balance between real-time performance and high precision renders it well-suited for applications necessitating swift and accurate detection.The network architecture of YOLOv8 is illustrated in

Figure 1.

3. Proposed Method

Figure 1 illustrates the utilization of a CSPDarknet53 backbone network with a C2f module and an FPN-PANet neck in the YOLOv8 architecture. This section provides a comprehensive overview of the DCS-YOLOv8 model’s network design. The primary objective is to enhance the detection performance of the YOLOv8s model, particularly for small objects in drone images, which presents a significant challenge. Our study introduces three key enhancements to improve small-object detection. Firstly, we incorporate a dedicated small-object detection layer to augment the model’s capability in capturing features of small objects. Secondly, we introduce the DCAM module, which is integrated with the C2f module to create the C2f-DCAM module. This integration enhances global context feature representation and strengthens the fusion of local and global features. Additionally, we implement the SCDown module to accelerate computation and reduce parameters. Lastly, we substitute CIoU with SDBIoU, which dynamically adjusts the loss weights for targets of varying sizes, thereby addressing limitations of conventional loss functions related to label noise, scale sensitivity, and convergence stability.

3.1. P2: Small Object Detection Head

To enhance the model’s performance across various scales, particularly for small and medium-sized objects, we introduce an additional detection layer (P2) specifically designed for small targets. The P2 layer, functioning as a lower-level feature map, offers detailed information and high-resolution features, enabling the model to detect both large and small objects effectively, thus enhancing its capability in small object detection. A key challenge in object detection is the wide range of target sizes. By integrating with other layers such as P3 and P4, the P2 layer empowers the YOLOv8 model to deliver superior overall performance in handling objects of diverse scales. This hierarchical architecture allows YOLOv8 to detect targets spanning from minuscule to extremely large sizes while maintaining a high level of accuracy.

3.2. DCS-Net Architecture

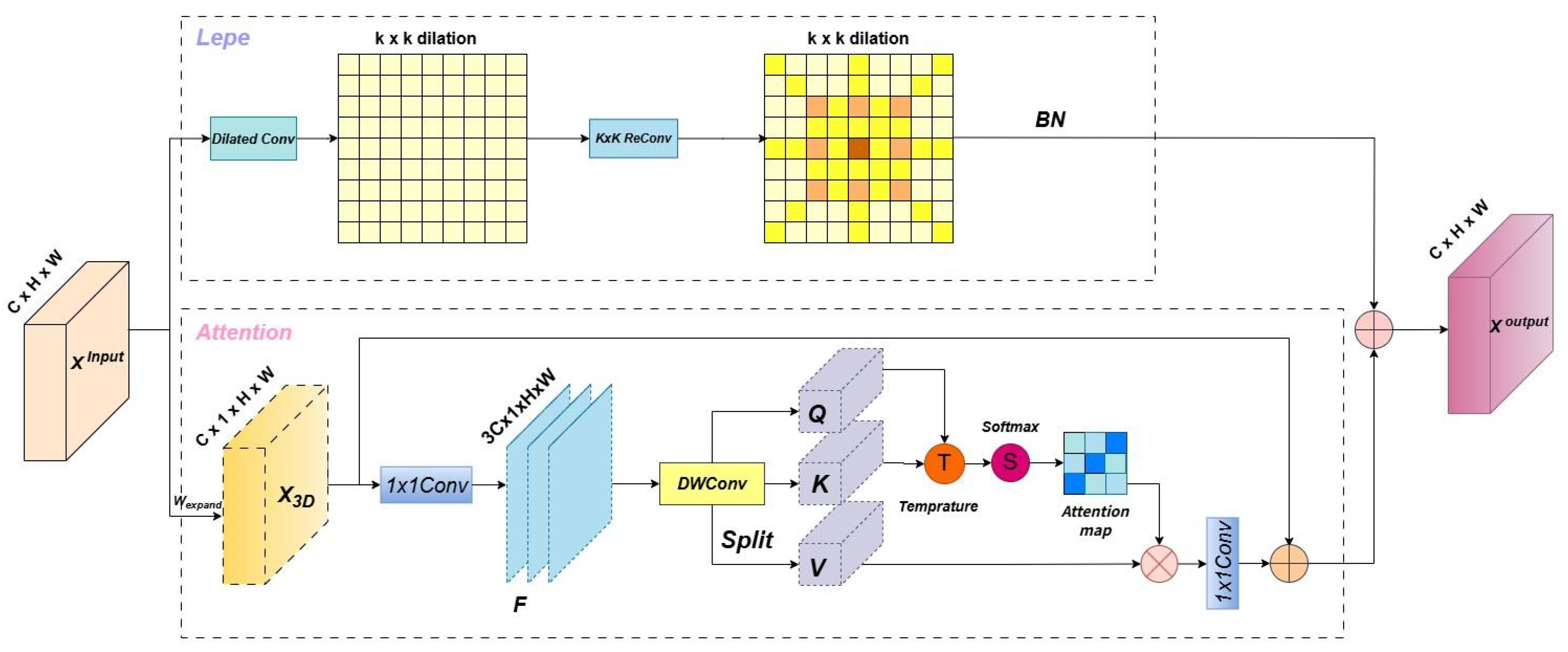

3.2.1. DCAM Module

Accurately modeling both local and global contextual information is critical for detecting small or obscured objects in UAV imagery. However, traditional convolutional architectures often fall short in this regard due to their inherently limited receptive fields. To address this challenge, we propose the Dynamic Convolution Attention Mixture (DCAM) module, as illustrated in

Figure 2. DCAM is designed to simultaneously enhance local feature extraction and global dependency modeling within CNNs by integrating dilated convolution, multi-branch reparameterization, and multi-head attention mechanisms.The DCAM consists of two parallel branches: the Lepe branch and the Attention branch, each responsible for different aspects of feature representation.The subsequent section provides an elaborate exposition of this module:

Lepe Branch

The Lepe branch is built upon the Dilated Reparam Block (DBR) [

26], which fuses large-kernel convolutions with parallel small-kernel convolutions employing various dilation rates. This design enables the module to capture both fine-grained local structures and broader spatial patterns efficiently. During training, the outputs from different branches are combined to enhance multi-scale representation. After training, these branches are consolidated into a single equivalent convolution via reparameterization, thus reducing inference complexity without sacrificing performance. By taking the input feature graph (

) and leveraging the convolution reparameterization block, we enhance the local multiscale features, as depicted in

Equation (1):

Where

is the output of the Lepe branch,

is the input feature. The Dilated Reparam Block (DBR) consists of multiple convolution branches with different dilation rates, which are merged into a single convolution operation through reparameterization.

employed to accelerate training convergence.

Attention Branch

In the attention branch, we first extend the input feature tensor

(2D image feature) to

by

. and generate query(

Q), key(

K)and value(

V) by depth-wise convolution (DWConv),

. Next we reshape

Q into

,reshaped

K into

, compute the inner product of

and

, use dynamic temperature modulation, introduce temperature parameters

T, Softmax function

S, generate attention map

. The computational burden is reduced instead of computing the huge regular attention map of size

, Then we splice

V with the attention map and output it via

. As shown in

formula (2) and (3):

Where

is the output of the Attention Branch.

denotes

.

is the output of the scaled dot-product attention module.

T is the temperature parameters,

is temperature scaling factor.

Finally, the output of the DCAM module calculation is computed as:

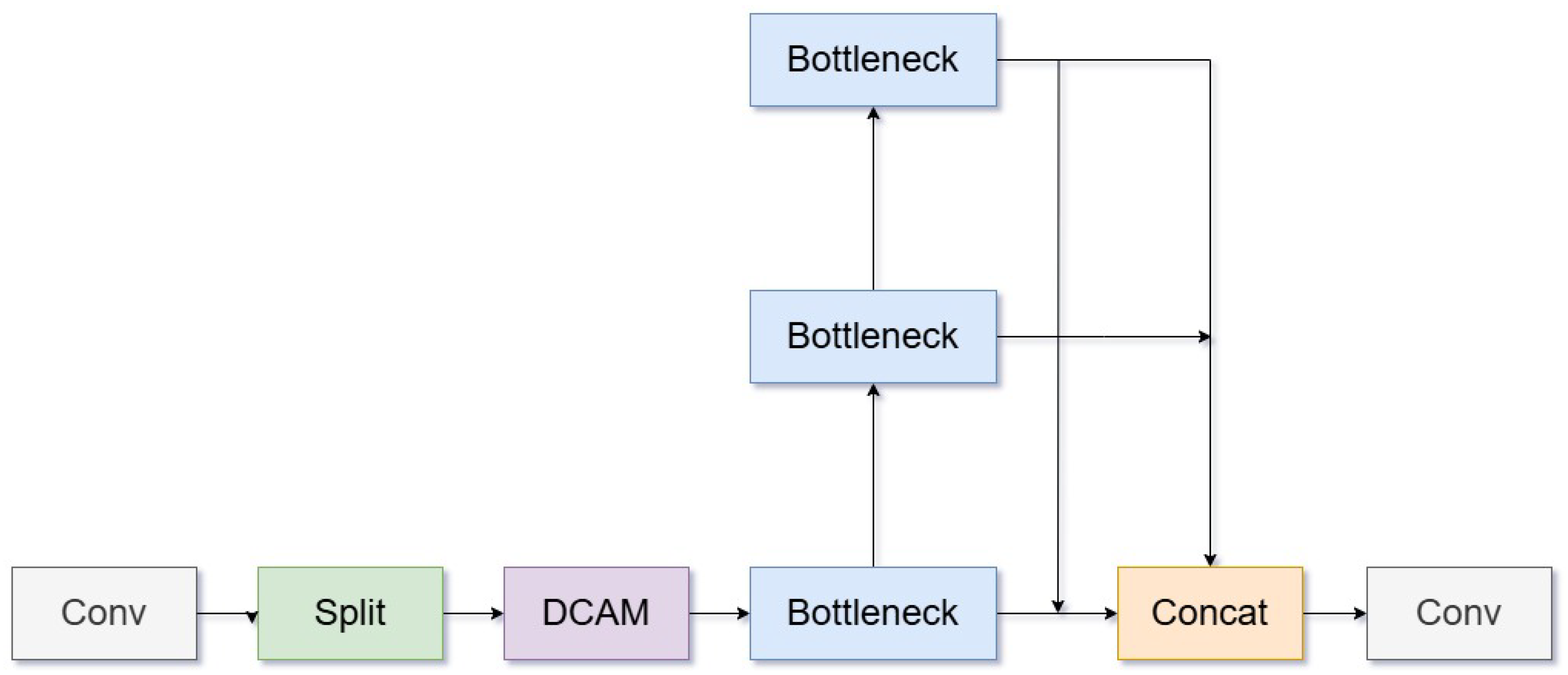

3.2.2. C2f-DCAM

As shown in

Figure 3, we integrate the DCAM module into the C2f block of YOLOv8 to form the C2f-DCAM module. The original C2f module enhances feature reuse and gradient propagation through residual connections and multi-branch structure. By embedding DCAM, we further boost its capacity to fuse local and global features, which is particularly advantageous for small object detection.This hybrid module enables richer spatial representations and deeper contextual understanding, allowing the network to better distinguish subtle object boundaries and fine details in cluttered aerial scenes.

3.2.3. SCDown Module

In standard YOLO architectures, downsampling is typically performed using 3×3 convolutions with stride 2, which increases channel depth while reducing spatial resolution. However, this approach introduces significant computational overhead. To address this, we design the SCDown module, a lightweight downsampling block that separates spatial and channel operations for better efficiency. SCDown comprises two sequential components:

This decoupled design minimizes information loss during downsampling by preserving fine-grained spatial cues while significantly lowering the computational burden. As a result, SCDown enhances the network’s ability to process multi-scale features effectively, which is vital for detecting small or overlapping targets in UAV imagery.

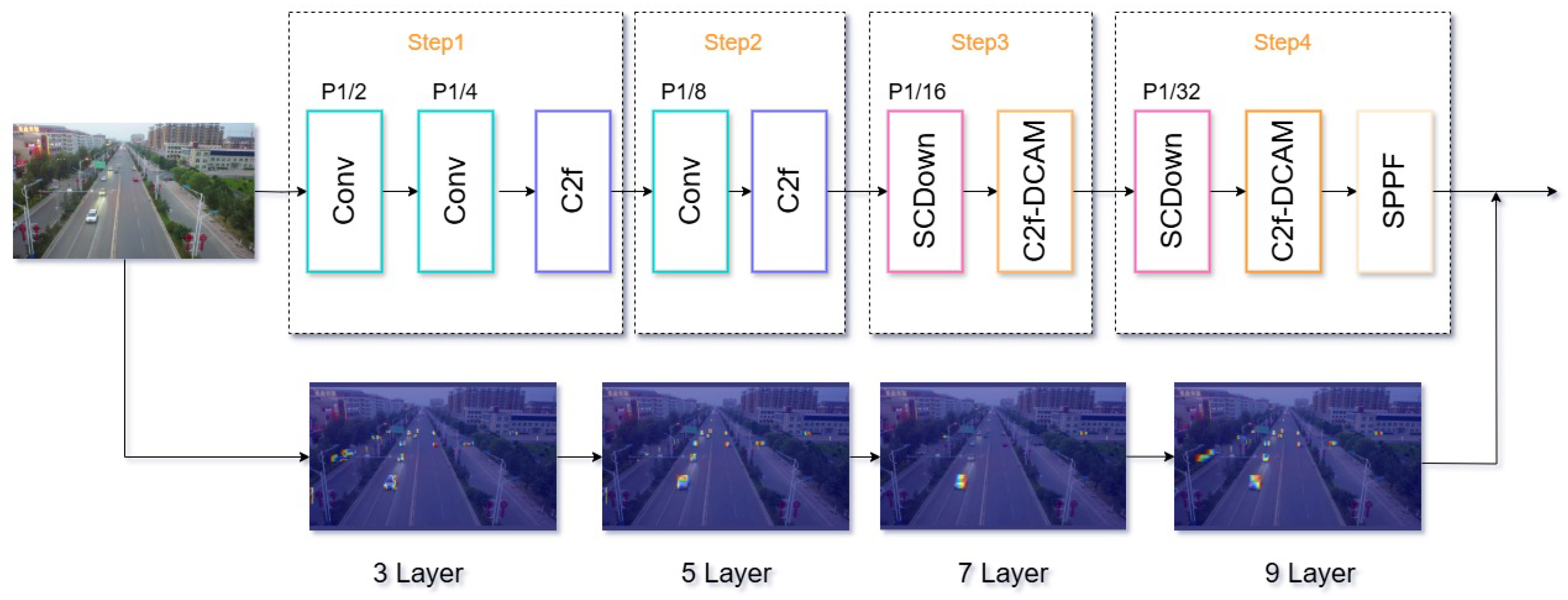

3.2.4. Overall Architecture

Figure 4 shows the overall network architecture of DCS-Net, which is designed for images with input size P= 640 x 640 and consists of four stages, each of which extracts and refines image features in turn. In order to further verify the correspondence between the structural design of each stage of DCS-Net and the perception ability of small targets, we visualized the feature maps of each key stage of the network and generated the thermal map shown in

Figure 4. The results show that there are significant differences in spatial attention area and feature response intensity in each stage, reflecting the synergy and complementarity between module functions:

Stage 1 The input image undergoes convolution and downsampling, reducing the feature map size by 1/4 while increasing the number of channels to 64-128. This process facilitates initial low-level feature extraction, focusing on aspects like edges and textures. The resulting thermal map primarily highlights the edge contours in the image, exhibiting heightened sensitivity to low-level features such as textures and boundaries. This stage captures intricate spatial details, establishing the groundwork for further feature extraction.

Stage 2 The feature map is further reduced to 1/8 of its original size to emphasize extracting intricate local structural details. This process aids the model in discerning boundary and shape characteristics of small targets. The thermal map progressively narrows down to the target region, displaying pronounced highlights around small targets. This phenomenon suggests that the network is differentiating foreground from background areas and developing semantic recognition capabilities.

Stage 3 The feature map size is reduced through the integration of the C2f-DCAM module. This module, known as the Dynamic Convolutional Attention Blending Module (DCAM), enhances the contextual semantic representation of small targets by employing parallel local enhancement (Lepe branching) and global dependency modeling (Attention branching). These mechanisms notably enhance target detection in scenarios with occluded, dense, or complex backgrounds. Notably, the thermal map excels in its capacity to concentrate on specific areas: it significantly amplifies responses in regions containing small targets while preserving background structural information. This observation suggests that the DCAM module steers the network towards establishing prolonged dependencies on critical regions via a global attention mechanism, thereby enhancing the discernment of small targets within intricate backgrounds.

Stage 4 The feature map undergoes additional compression for downsampling efficiency, departing from conventional large-step convolution methods. The SCDown module operates through channel-wise spatial compression and separate dot-convolution channel compression, diminishing parameter volume while preserving essential spatial structures. This approach effectively addresses information loss concerns. Despite further reduction in thermal map spatial resolution, high responsiveness to small target areas is preserved. This outcome is credited to the SCDown module’s computational compression, which safeguards crucial spatial layout features and prevents excessive information loss.Finally, SPPF module (Fast Spatial Pyramid Pooling) fuses feature maps from different scales to enhance the adaptability to multi-scale objects, especially for detecting large and small objects simultaneously.

The DCS-Net exhibits well-defined functions and tight integration across its stages. Its structural design significantly diminishes model complexity while upholding detection accuracy, enabling efficient real-time inference on edge devices like RK3588. The hierarchical arrangement of DCS-Net aligns closely with the spatial attention pattern of thermal maps. The design of each stage is pivotal in determining the attention span and discrimination capability for detecting small targets, thereby achieving dual optimization for precise localization and effective reasoning.

3.3. SDBIoU Loss Function

The YOLO loss function plays a crucial role in enhancing object detection accuracy by employing multi-task learning to refine bounding box localization, object confidence, and classification precision. While IoU-based loss functions are indispensable for assessing spatial overlap, their efficacy diminishes in the absence of overlap, resulting in minimal gradient signals. To mitigate this issue, several IoU-based loss functions have been devised, each characterized by distinct attributes and constraints.

DIoU (Distance-IoU) [

27] serves as an enhanced regression loss function in the realm of object detection. It incorporates the concept of "centroid distance" into the loss computation, thereby augmenting the efficiency and precision of aligning predicted bounding boxes with their ground-truth counterparts. Nevertheless, it is important to note that DIoU primarily focuses on optimizing position and overlap metrics, neglecting the aspect of shape congruence. Consequently, this singular emphasis may result in bounding boxes that are aligned based on centroids but do not match in terms of shape, thereby compromising the overall quality of fitting. The DIoU formula is delineated in

Equation (5):

Where

represents the intersection over union of the prediction and ground - truth boxes.

denotes the Euclidean distance between their center points.

c indicates the diagonal length of the smallest enclosing box covering both prediction and ground - truth boxes.

CIoU (Intersection over Union)[

28] is a loss function utilized in object detection for refining bounding box regression. It enhances the conventional IoU metric by incorporating penalties for the distance between the centers of the predicted and ground-truth boxes, as well as for differences in aspect ratio. This modification results in a more holistic evaluation of the discrepancy between the predicted and actual bounding boxes. Nevertheless, the dynamically adjusted weights in CIoU may exhibit fluctuations in scenarios where IoU values are either very high or very low, thereby introducing instability during the training process. Furthermore, CIoU demonstrates reduced efficacy in accurately detecting objects with highly irregular shapes. The mathematical expression for CIoU is presented in

Equation (6):

where

is the weight coefficient that controls the influence of

,

represents the aspect - ratio penalty, compensating for the difference in aspect ratios between prediction and ground - truth boxes.

and

denote the width and height of the prediction and ground - truth boxes respectively.

EIOU[

29] is a refined loss function utilized in object detection for bounding-box regression, aiming to enhance both detection precision and training efficiency. It achieves this by breaking down geometric inaccuracies into three components: the intersection area, the distance between center points, and variations in width and height. Additionally, it incorporates a dynamic weighting mechanism to prioritize optimizing challenging instances. Despite its effectiveness in addressing size discrepancies, EIOU encounters difficulties related to anchor box expansion and slow convergence during regression. Its superior accuracy is counterbalanced by increased computational complexity, necessitating meticulous parameter adjustments and a higher implementation threshold. The calculation formula for EIOU is presented in

Equation (7):

where

and

denote the width and height of the smallest enclosing box that covers both the prediction box and the ground - truth box.

We replace the CIoU with SDBIoU (Scale-based Dynamic Loss) [

30] to overcome challenges associated with traditional loss functions related to label noise, scale sensitivity, and convergence stability. SDBIoU dynamically adjusts loss weights based on the scale of targets to address issues such as disproportionate amplification of localization errors for small targets under fixed-weight loss calculations and convergence oscillations caused by gradients from targets of different scales interfering with each other. Moreover, annotation errors, such as bounding box offsets, are inaccurately magnified by fixed loss functions, compromising model robustness. The mathematical formulation of SDBIoU is presented in

equations (8), (9), (10), and (11), where it integrates IoU and centroid distance by introducing a dynamic coefficient

to adjust the weight range. SDBIoU incorporates a scale-aware mechanism to calculate influence coefficients based on target area and implements collaborative optimization through separate scale loss (Sloss) and localization loss (Lloss) components.

Where

represents the Intersection over the Union of thepredicted and ground truth BBox,

measures the aspectratio consistency of the BBox,

is the Euclidean distance,

and

are the centroids of the predicted BBox

and target BBox

, and

c is the diagonal length of two BBoxes.

Where

represent the scaling factors for width and height between the original image and the current feature map. and

denote the width and height of the original image, while

denote the width and height of the current feature map.

Where

represents the influence coefficient of the BBox.

is determined by the maximum size of IRST defined by the International Society for Optics and Photonics (SPIE),

is served as the dynamic coefficient.

Where

and

are the influence factors of

and

respectively

4. Results

The section begins by introducing the datasets utilized in the study, followed by comprehensive descriptions of the experimental setting and training methodologies. It also delineates the evaluation metrics utilized to gauge model performance. The efficacy of the proposed approach is validated through comparative analysis against leading models, with YOLOv8 serving as the reference point. Furthermore, this section assesses the model’s efficacy in demanding real-world scenarios, including the detection of distant and small objects situated far from the camera.

4.1. Dataset

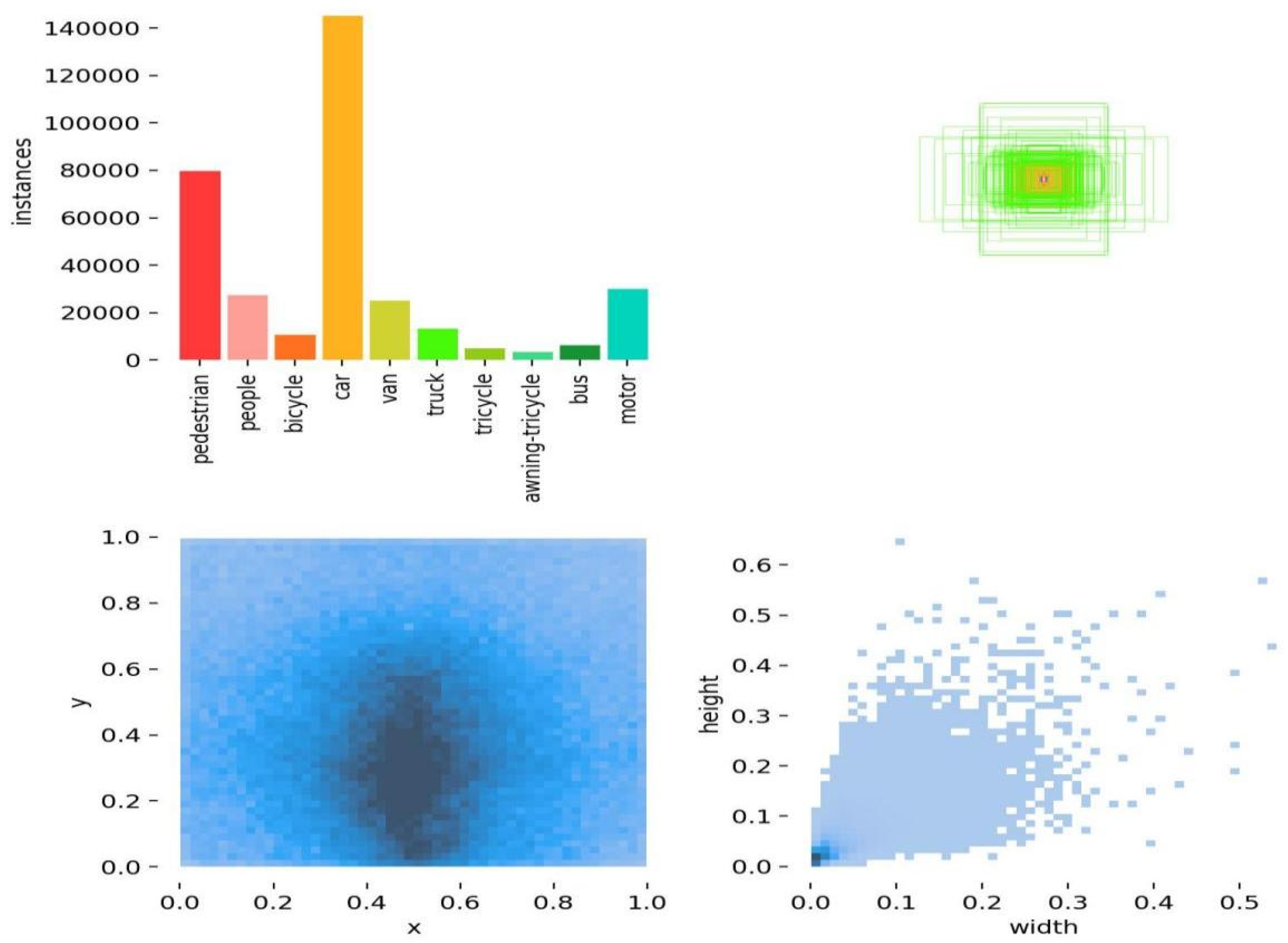

The VisDrone2019 dataset [

31], a renowned compilation of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) aerial photographs, was collaboratively developed by the Machine Learning and Data Mining Laboratory at Tianjin University and the AISKYEYE data mining group. This dataset consists of 288 video segments (amounting to 261,908 frames) and 10,209 still images. It was acquired using multiple cameras mounted on drones in over a dozen cities across China.

One of the most remarkable aspects of this dataset is its high degree of diversity. It encompasses a broad range of geographical locations, environmental circumstances, and object types. Geographically, it includes imagery from 14 distinct Chinese cities, offering a comprehensive portrayal of both urban and rural landscapes. The dataset contains various entities such as pedestrians, automobiles, and bicycles, and it covers a wide range of population densities, from sparsely populated regions to highly congested areas. Additionally, it captures images under different illumination conditions, including both daylight and nocturnal scenes.

A crucial feature of the VisDrone2019 dataset is the inclusion of numerous small objects of varying sizes, depicted from multiple viewpoints and within different contexts. This diversity increases the dataset’s intricacy and difficulty level, distinguishing it as a particularly demanding benchmark in the realm of computer vision.

Figure 5 illustrates the process of manually annotating objects in the VisDrone2019 dataset.

4.2. Experimental Environment and Training Strategy

The experiments were conducted on a Ubuntu 22.04 system equipped with an Intel i7-12800HX CPU, NVIDIA A10 GPU, and 32GB RAM. The deep learning environment is based on PyTorch 2.3.1, utilizing CUDA 12.1 for computational acceleration, and Python 3.10 as the programming language.The experiment configured 150 training epochs, set the batch size at 16, and determined the image size as 640. All the other hyper - parameters were established at their original default values, and the baseline model was YOLOv8s.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

To assess our enhanced model’s detection performance, we used several evaluation metrics: Precision, Recall, , , and the model parameter count. The formulas for these metrics are as follows:

Precision is an indicator of the ratio of true positives to the total predicted positives, as shown in

Equation (12):

True positives (

) are instances where the model correctly predicts positive cases. False positives (

) are cases where the model incorrectly predicts positive instances. False negatives (

) refer to instances where the model fails to detect actual positive cases.

Recall measures the ratio of correctly predicted positive samples to all actual positive samples,as shown in

Equation (13):

Average precision (AP) represents the area under the precision-recall curve,as shown in

equation(14):

Mean average precision (

) indicates the average of

across all classes, showing the model’s detection performance on the entire dataset. as shown in

Equation (15):

Where

denotes the Average Precision for the category indexed by

i,

N represents the total number of categories in the training dataset.

4.4. Experiment Results

This section provides an in-depth evaluation of the DCS-YOLOv8 model through a series of targeted experiments. We begin by comparing the proposed SDBIoU loss with several widely used IoU-based loss functions. The results demonstrate that SDBIoU effectively mitigates issues such as label noise and scale sensitivity, particularly benefiting small object detection.We then assess the model’s performance relative to different YOLO variants and state-of-the-art detectors including Faster R-CNN[

11], Cascade R-CNN[

32], Swin Transformer[

33], and CenterNet[

34]. DCS-YOLOv8 consistently achieves a better trade-off between accuracy and model complexity, outperforming many larger models in both precision and recall while maintaining a lightweight structure.Ablation studies further validate the individual contributions of each enhancement module—namely the P2 detection head, the DCAM attention mechanism, SCDown downsampling, and the SDBIoU loss. These components each offer measurable improvements, and their combined integration results in a significant overall performance boost.Finally, real-world deployment on RK3588 embedded hardware confirms that DCS-YOLOv8 supports real-time inference, validating its practical utility for UAV-based scenarios. The model demonstrates not only competitive accuracy but also strong adaptability to resource-constrained environments, confirming its value for real-time small object detection in aerial imagery.

4.4.1. Comparison of Loss Functions

We conducted a comprehensive comparison between the proposed Scale-based Dynamic Balanced IoU (SDBIoU) and several commonly used IoU-based loss functions within the YOLOv8 framework, including CIoU, DIoU, EIoU, and MPDIoU, using identical training settings to ensure fairness. As shown in

Table 1, SDBIoU demonstrates competitive or superior detection performance across key evaluation metrics. While its precision shows a slight decrease compared to CIoU, it achieves notable gains in recall, indicating improved sensitivity to true positive detections—especially for small or low-resolution targets.

This trade-off ultimately leads to a net improvement in the overall detection capability. The enhanced performance of SDBIoU can be attributed to its dynamic loss weighting mechanism, which adjusts the influence of each sample based on object scale and spatial characteristics. By incorporating a scale-aware influence coefficient, SDBIoU effectively reduces the disproportionate penalization of small objects and mitigates instability caused by inconsistent IoU gradients. This enables the model to maintain more stable convergence and greater robustness during training, particularly in scenarios involving densely packed or variably scaled targets.

4.4.2. Comparison with Different Mainstream Models

We conducted extensive comparative experiments to evaluate the performance of DCS-YOLOv8 against both existing YOLO variants and several mainstream object detection frameworks. The results, summarized in

Table 2 and Table 3, consistently highlight the superior efficiency and accuracy of the proposed model, particularly in small-object detection scenarios.

Compared with earlier YOLO versions such as YOLOv3, YOLOv5s, and YOLOv7,DCS-YOLOv8 achieves notably higher detection accuracy while maintaining a significantly lower or comparable parameter count. Although YOLOv7 is exceptionally lightweight, its detection performance lags behind that of DCS-YOLOv8, indicating that model compactness alone does not ensure reliable detection in challenging aerial scenes. In contrast, DCS-YOLOv8 offers a better balance between parameter efficiency and detection robustness, making it highly suitable for real-time applications on resource-constrained platforms.

In addition, DCS-YOLOv8 was evaluated against multiple YOLOv8 variants, ranging from YOLOv8n to YOLOv8x. These variants increase detection capacity by scaling depth and width, but at the cost of rising computational demands. Despite having fewer parameters than most of these models, DCS-YOLOv8 delivers superior detection performance:our enhanced model achieves detection rates of 44.5%

and 26.9%

with a parameter count of only 9.9 million. Furthermore, when compared to advanced YOLOv8-based models such as PVswin-YOLO[

36], Cot-YOLO[

37], and DS-YOLO[

38], our approach exhibits highly competitive results. While minor variations are observed in individual metrics (e.g., precision or recall), DCS-YOLOv8 consistently maintains a strong overall balance across all performance indicators, particularly excelling in scenarios involving small or visually ambiguous targets. For instance, in comparison to PVswin-YOLO, DCS-YOLOv8 shows a marginal 0.3% decrease in Precision but a corresponding 0.3% improvement in Recall, 1.2% higher

, and 0.5 higher

.

To further assess the generalizability of DCS-YOLOv8, we compared its performance with several state-of-the-art object detectors outside the YOLO family, including Faster R-CNN[

11], Swin Transformer[

33], CenterNet[

34], and Cascade R-CNN[39]. These models are known for their architectural sophistication and have shown strong performance across various benchmarks. However, their limitations become evident when applied to UAV imagery: Faster R-CNN struggles with low-resolution feature maps, Swin Transformer’s window-based attention can lead to information discontinuities, CenterNet has difficulty localizing small targets in cluttered scenes, and Cascade R-CNN demands high computational resources. In contrast, DCS-YOLOv8 achieves superior accuracy and generalization across object categories, as evidenced by its consistently higher scores in both

(44.5%) and

(26.9%).

These experimental results clearly validate the advantages of DCS-YOLOv8 in balancing computational complexity, detection accuracy, and real-time inference capability, thereby demonstrating its strong suitability for deployment in UAV-based detection systems, particularly those requiring accurate recognition of small, dense, or partially occluded objects.

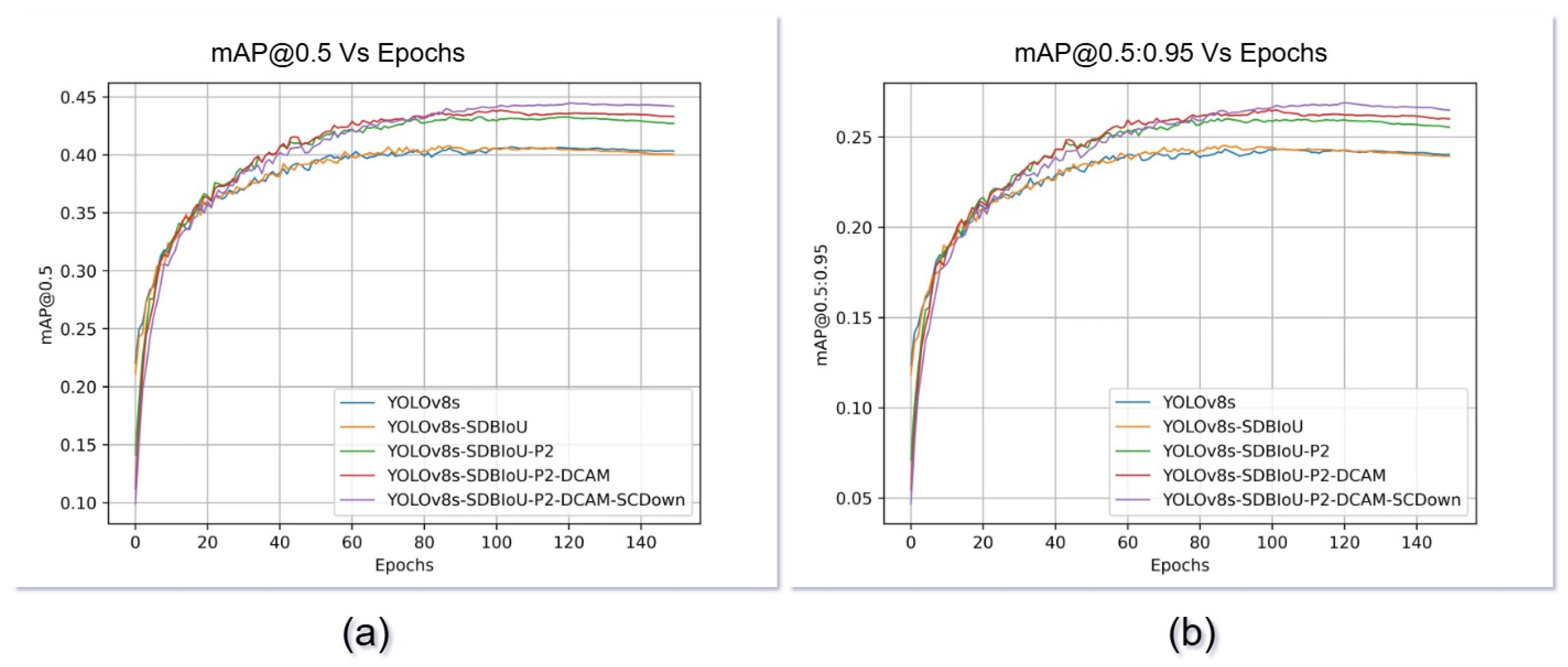

4.5. Ablation Experiments

To quantitatively assess the contribution of each proposed component in DCS-YOLOv8, we conducted a series of ablation experiments based on the YOLOv8s baseline model. The results, summarized in

Table 4, demonstrate that each enhancement—namely SDBIoU, the P2 detection layer, DCAM, and the DCS-Net backbone—provides measurable performance gains across multiple object categories, particularly for small and dense targets.

Initially, replacing the standard CIoU with SDBIoU yields a modest yet consistent improvement. Although the overall only increases from 40.6% to 40.8%, category-level gains are more evident—such as a 1.2% increase in the Tricy category (from 28.5% to 29.7%) and a 3.1% rise in Bus detection (from 57.8% to 60.9%). This highlights SDBIoU’s effectiveness in enhancing localization robustness for medium-to-large-scale objects and improving recall for hard-to-detect instances.

The integration of the P2 detection layer has a more substantial impact. When added on top of YOLOv8s-SDBIoU, it increases the overall from 40.8% to 43.3%, representing a 2.5% absolute gain. This enhancement particularly benefits small object categories: Pedestrian detection improves from 44.1% to 50.0%, Bicycle from 14.4% to 16.6%, Car from 79.6% to 83.3%, and Motorcycle from 44.9% to 50.6%. These results confirm that the P2 layer effectively captures high-resolution spatial features essential for detecting low-scale targets.

Replacing the original YOLOv8 backbone with the proposed DCS-Net, which integrates the C2f-DCAM and SCDown modules, further improves detection performance. The full model—YOLOv8s-SDBIoU-P2 with DCS-Net—achieves an overall of 44.5%, the highest among all tested variants. Category-wise, additional improvements are observed in ’People’ (42.5%, up from 34.3% in baseline), ’Van’ (48.5%, up from 45.5%), and ’A-tricy’ (18.1%, up from 16.6%). These results validate DCS-Net’s effectiveness in enhancing both local detail preservation and global context awareness.

Table 5 further highlights the cumulative effect of these enhancements. Compared to the baseline YOLOv8s, the final DCS-YOLOv8 model improves overall Precision from 51.8% to 54.2%, Recall from 39.4% to 42.1%, from 40.6% to 44.5%, and from 24.3% to 26.9%. Moreover, these improvements are achieved while reducing the parameter count from 11.1 million to 9.9 million, and maintaining real-time inference with an average latency of 10.1 ms per image.

These findings confirm that the incremental integration of SDBIoU, the P2 layer, and DCS-Net modules not only enhances the detection accuracy—particularly for small or complex objects—but also improves model compactness and inference speed, which are critical for UAV-based applications.

Figure 6 presents the training dynamics of DCS-YOLOv8 compared to the baseline YOLOv8s over 150 epochs, with evaluation metrics including and . Notably, DCS-YOLOv8 begins to outperform YOLOv8s in both metrics from approximately epoch 22. The performance gap steadily widens thereafter, and DCS-YOLOv8 stabilizes earlier—around epoch 50—indicating faster convergence and greater training stability.

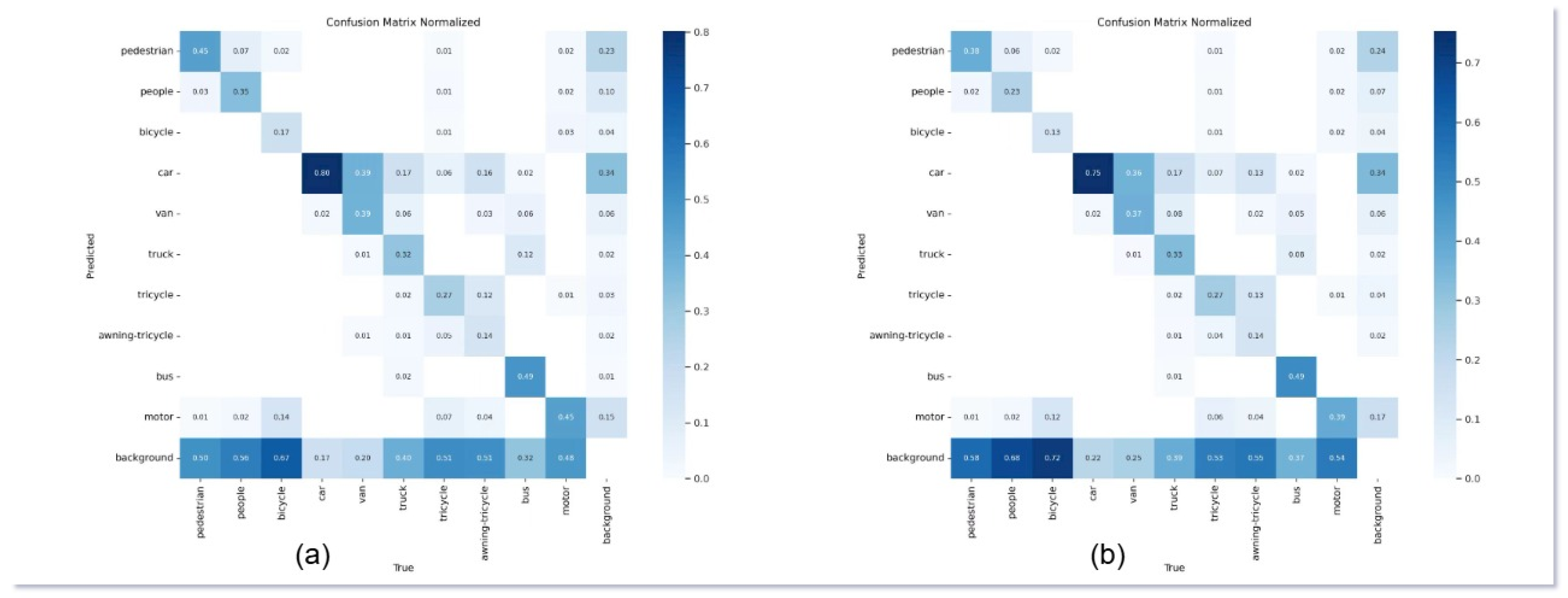

4.6. Visual Assessment

To further analyze classification accuracy, we employed a confusion matrix comparing DCS-YOLOv8 and YOLOv8s across 10 object categories. As shown in

Figure 7, the diagonal elements of DCS-YOLOv8’s matrix exhibit consistently darker shades compared to those of YOLOv8s, indicating a higher frequency of correct predictions. In contrast, the off-diagonal elements—especially in the final row corresponding to background misclassification—appear lighter, suggesting that DCS-YOLOv8 makes significantly fewer false negative errors.

For instance, in the ’Pedestrian’ category, the accuracy of DCS-YOLOv8 increases from 44.2% to 51.5%, while ’People’ improves from 34.3% to 42.5%, and ’Motorcycle’ from 44.8% to 50.6%. These improvements underscore the model’s enhanced sensitivity to small-scale, human-related targets. Additionally, the confusion matrix reveals that misclassifications into the ’background’ class are greatly reduced. This is particularly evident in categories such as ’Bus’ and ’Tricycle’, which often suffer from occlusion and scale ambiguity in UAV images.

Nevertheless, some challenges remain. Categories such as ’Bicycle’ (17.2%), ’Tricycle’ (33.3%), and ’A-tricycle’ (18.1%) continue to exhibit notable confusion, frequently misidentified either among themselves or as background. This is likely due to similar visual structures and dense scene contexts. Even so, the overall improvement across most categories highlights DCS-YOLOv8’s superior feature discrimination and contextual reasoning capabilities.

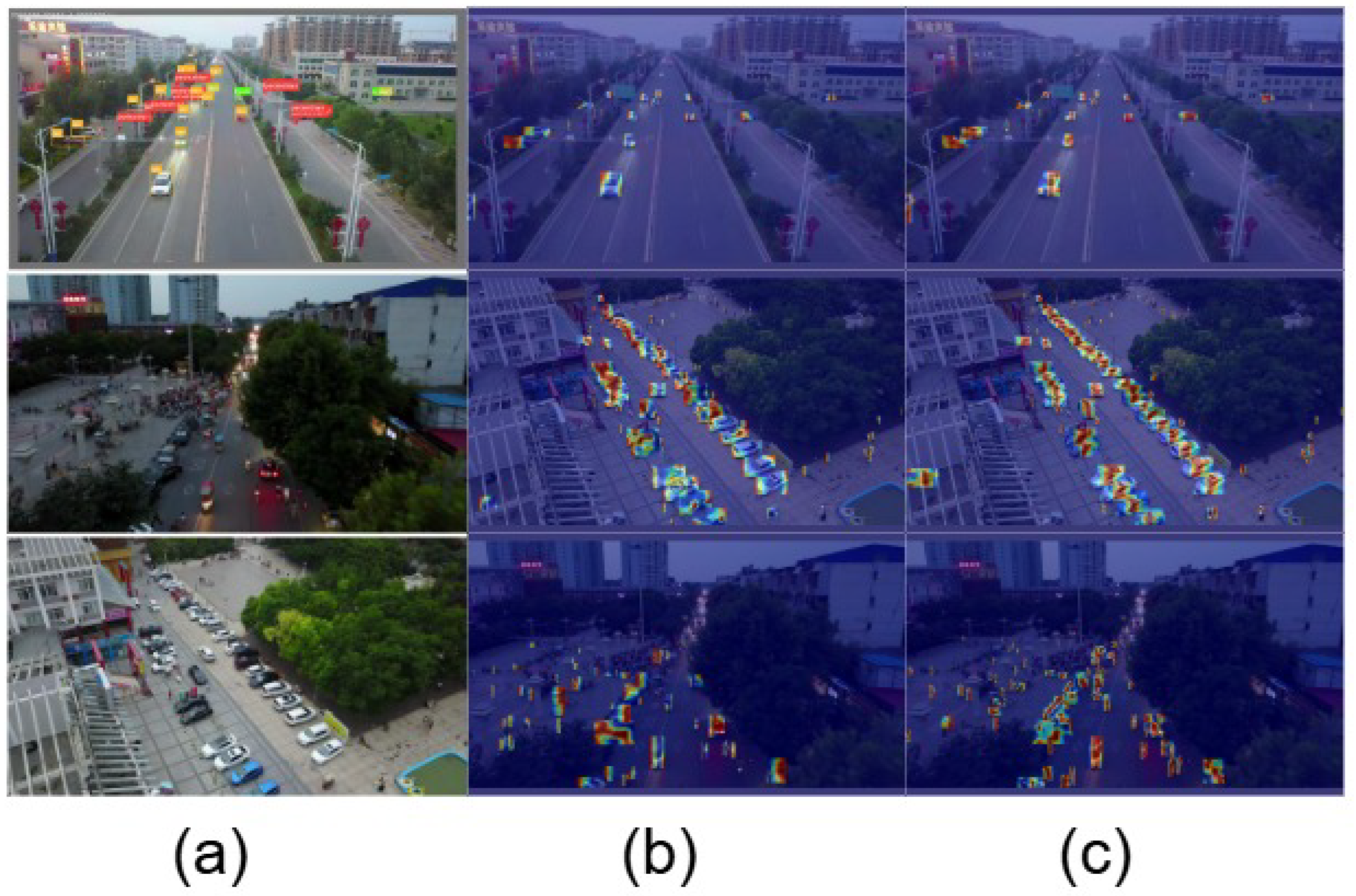

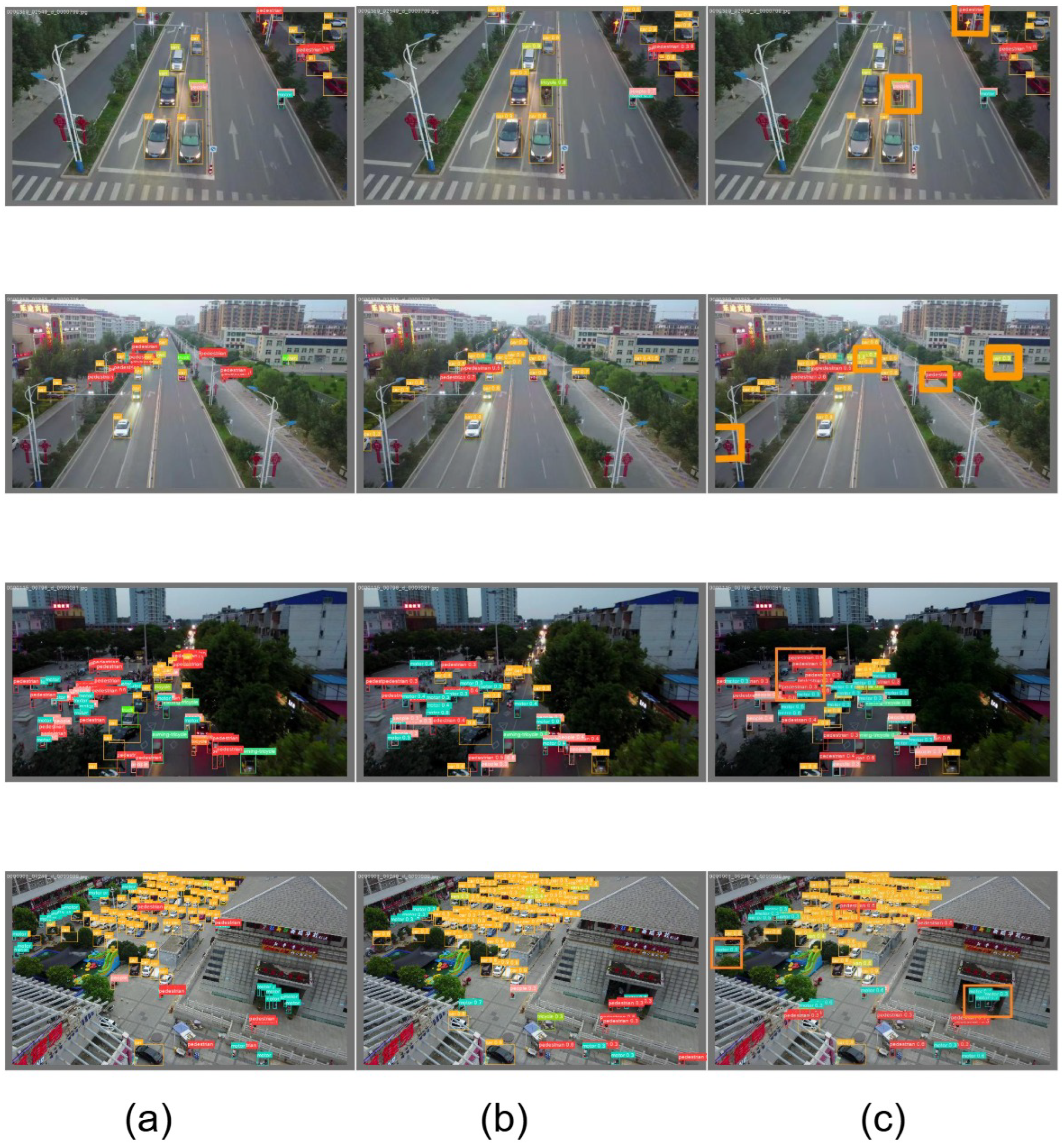

As illustrated in

Figure 8, we conducted a comparative analysis of feature activation heatmaps produced by the baseline model, YOLOv8s, and our proposed DCS-YOLOv8 across a variety of UAV-based detection scenarios. These include environments with heavy occlusion, densely cluttered backgrounds, and poor lighting conditions—all of which pose significant challenges to conventional object detection systems.

Notably, DCS-YOLOv8 exhibited consistently stronger and more concentrated activations in relevant semantic regions, indicating improved spatial attention and a heightened ability to distinguish target features from background noise. Compared to the other models, DCS-YOLOv8 generated heatmaps with clearer focus on small or partially occluded objects, while reducing irrelevant or scattered activation across the image.

These results demonstrate that the proposed model effectively learns to allocate attention toward task-critical areas, particularly for small and hard-to-detect objects. The observed improvements can be attributed to the inclusion of the DCAM module, which enhances both global and local feature representations, and the P2 detection layer, which enables high-resolution detail preservation at shallow feature levels. Altogether, these mechanisms contribute to the model’s superior perception capability in complex aerial environments.

As shown in

Figure 9, we qualitatively evaluated the detection performance of the baseline model, YOLOv8s, and our DCS-YOLOv8 across multiple challenging UAV scenarios. These scenarios include high-altitude surveillance views, night-time urban scenes with low illumination, crowded intersections with overlapping objects, and visually complex backgrounds with high texture similarity.

Across all scenarios, DCS-YOLOv8 demonstrated clear improvements in detecting small, occluded, and distant targets that were frequently missed by the baseline and YOLOv8s models. In low-light scenes, DCS-YOLOv8 produced more confident detections with better-aligned bounding boxes. In crowded environments, it successfully separated overlapping objects such as pedestrians and cyclists, maintaining high detection fidelity even at the image boundaries. Additionally, in scenes involving distant targets, the model maintained robust detection performance with higher IoU values and fewer false positives.

These improvements highlight the effectiveness of DCS-YOLOv8 in extracting semantically meaningful features and achieving fine-grained localization across diverse real-world conditions. The integration of structural innovations—namely, the P2 detection layer, DCAM attention mechanism, and the scale-sensitive SDBIoU loss—play a pivotal role in enabling the model to generalize across varying object scales and densities. Collectively, the results confirm the enhanced adaptability and detection reliability of DCS-YOLOv8 in practical UAV applications.

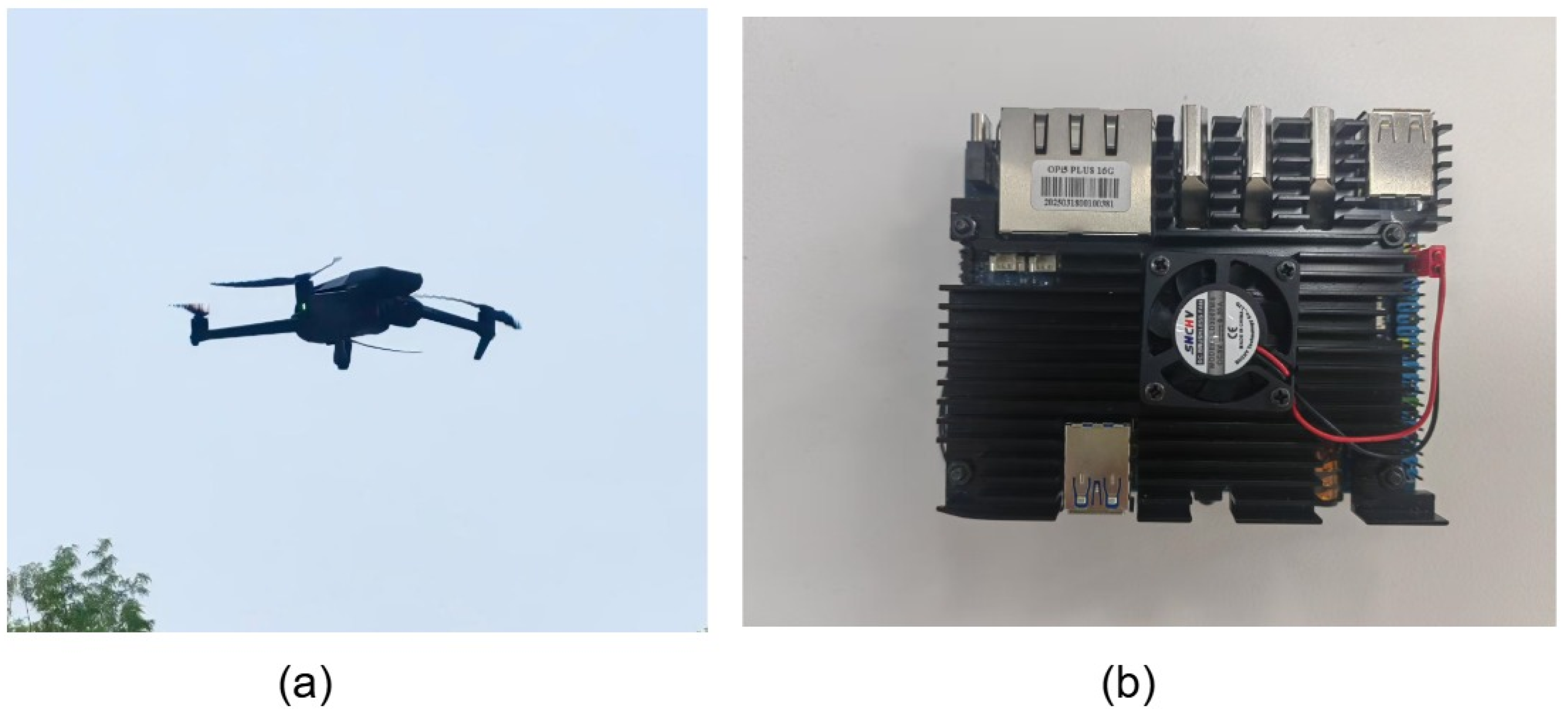

4.7. Real - Time Object Detectio

To validate the real-time feasibility of our model, we deployed DCS-YOLOv8 on an embedded UAV detection platform comprising the Orange Pi RK3588 board and the DJI Mavic 3 drone, as illustrated in

Figure 10. The RK3588 is powered by a 64-bit octa-core Rockchip RK3588S processor and features an integrated 3D GPU, delivering a high-performance yet compact solution for edge AI inference.The DJI Mavic 3 drone, equipped with a 4/3 CMOS Hasselblad main camera and a 28× hybrid zoom telephoto lens, served as the image acquisition device for aerial traffic monitoring. This system architecture ensures low-latency data transmission and onboard processing, making it suitable for time-sensitive applications such as intelligent traffic surveillance, emergency response, and security patrols.

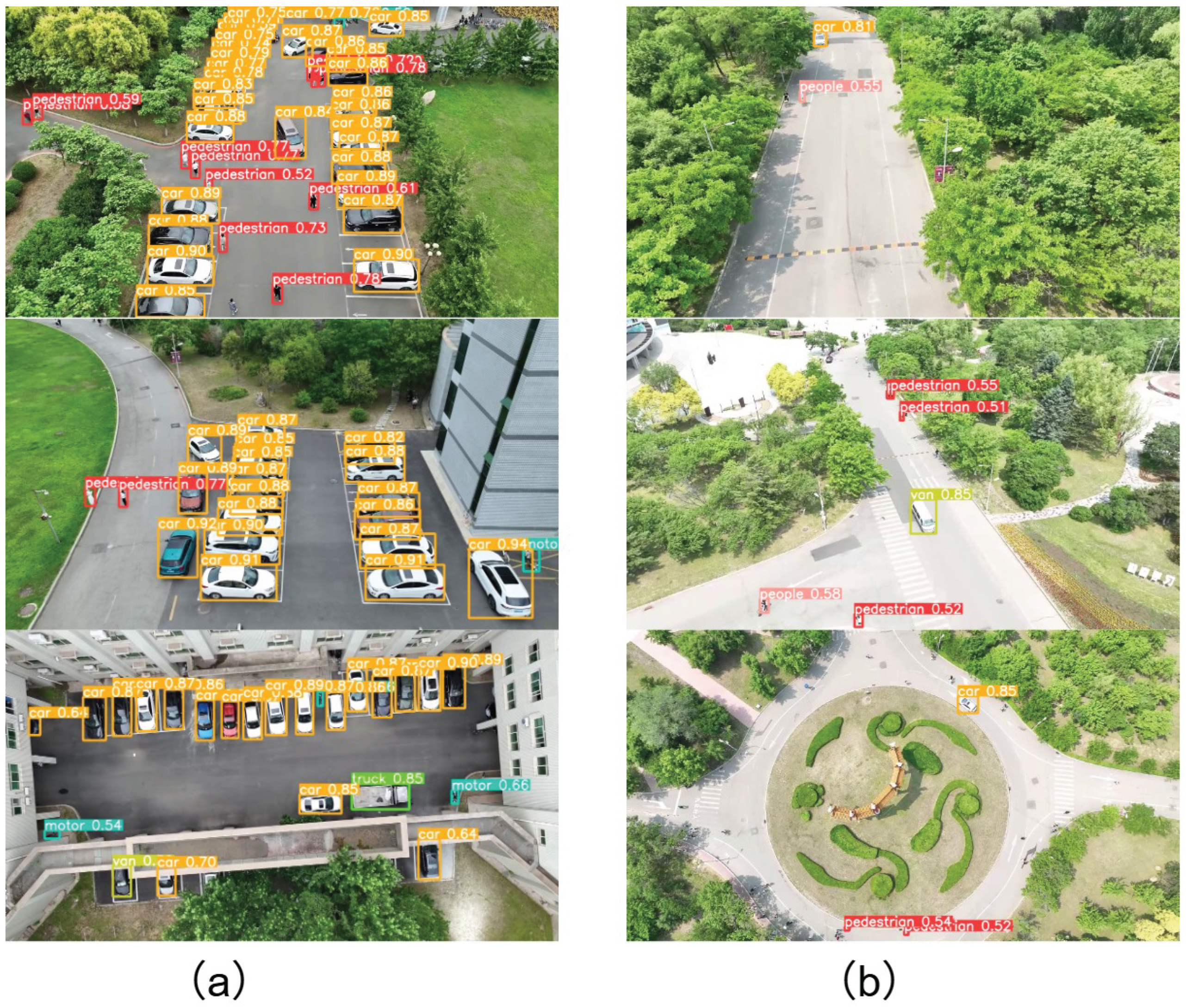

Figure 11 presents UAV-captured target detection results across various scenes and flight altitudes, illustrating the model’s capability to recognize multi-scale targets in complex spatial environments.

The figure presents images captured from various angles and altitudes, covering scenarios such as dense traffic areas, urban streets, and crowded locations. The results indicate that DCS-YOLOv8 consistently delivers stable detection performance for large, well-defined targets like cars, vans, and trucks, regardless of flight altitude. This suggests the model’s robust scaling capabilities, with precise target boundaries and accurate positioning. Conversely, for smaller targets like pedestrians, people, and motorcycles, detection effectiveness is more altitude-dependent. At lower altitudes, higher resolution and detailed textures enhance detection, while at higher altitudes, reduced pixel proportions and blurred details lead to decreased accuracy, resulting in incomplete boundaries or increased missed detections.The figure illustrates DCS-YOLOv8’s stability in handling real-world interference factors like background complexity and target occlusion. In low-altitude images, despite challenges such as multi-target aggregation and angle tilt, the model effectively distinguishes and accurately identifies various targets, demonstrating high robustness in dense scenes. Even in high-altitude images, where target sizes are further reduced, the model accurately detects main vehicles, evidencing its strong generalization capability for small, distant targets.

Figure 11 demonstrates DCS-YOLOv8’s proficiency in detecting multi-scale targets across varying flight altitudes and scenarios, confirming the efficacy of its multi-scale feature fusion and small target perception mechanisms, and reinforcing its utility in UAV monitoring tasks.

4.8. Discussion

The experimental results highlight the superior detection performance of our proposed DCS-YOLOv8 model compared to the baseline YOLOv8s. This performance enhancement is attributed to a series of architectural optimizations targeting small object detection in UAV imagery. Specifically, the improvements encompass the addition of a dedicated small-object detection layer (P2), the introduction of the Dynamic Convolution Attention Mixture (DCAM) module, the use of the SCDown module for lightweight downsampling, and the replacement of the CIoU loss function with the Scale-based Dynamic Balanced IoU (SDBIoU).

First, the P2 detection layer was integrated to enhance high-resolution feature utilization, enabling finer localization of small targets typically lost in deeper layers. Second, DCAM strengthens the model’s capability in both local feature enhancement and global context modeling, effectively handling occlusion and cluttered backgrounds. Third, SCDown reduces computational complexity while maintaining spatial fidelity, allowing deployment on embedded hardware such as the RK3588. Lastly, SDBIoU introduces scale-aware loss reweighting, addressing label noise, scale imbalance, and instability during training, as shown in

Table 5.

In this study, we evaluated the DCS-YOLOv8 model through the following comparative and ablation analyses:

Baseline comparison: As shown in

Table 5, compared to YOLOv8s, DCS-YOLOv8 achieves a 3.9% increase in

(from 40.6% to 44.5%) and a 2.6% increase in

(from 24.3% to 26.9%), while simultaneously reducing parameter count from 11.1M to 9.9M, confirming both performance and efficiency gains.

YOLOv8 series comparison:

Table 2 demonstrates that DCS-YOLOv8 outperforms YOLOv8n, YOLOv8s, and YOLOv8m in precision, recall, and mAP metrics, and achieves comparable performance to the heavier YOLOv8l with fewer parameters. Notably, it surpasses YOLOv8s by 2.4% in

and 2.6% in

, validating the scalability and effectiveness of our enhancements.

Mainstream YOLO models comparison: Compared to YOLOv3, YOLOv5s, and YOLOv7, DCS-YOLOv8 delivers a better balance between inference speed and detection accuracy. Although YOLOv7 has fewer parameters, its detection performance lags behind, particularly in complex UAV imagery.

State-of-the-art detectors comparison:

Table 3 illustrates that DCS-YOLOv8 outperforms advanced detectors such as Faster R-CNN, Swin Transformer, Cascade R-CNN, and CenterNet, with a

increase of 4.8% and

increase of 2.7% over the best-performing baseline, confirming its robustness and adaptability in real-world scenarios.

Ablation studies: The incremental addition of each module was evaluated. As shown in

Table 4 and

Table 5, the SDBIoU loss improves

by 0.2%, P2 layer by 2.5%, and DCAM by 0.6%, while integrating SCDown leads to a further 0.6% improvement in

. These results demonstrate that each component meaningfully contributes to the final model performance.

Following quantitative assessments, we conducted extensive visual analysis, including feature heatmaps, confusion matrices, and qualitative detection visualizations. DCS-YOLOv8 exhibits stronger activation on small and occluded targets, better separation from background noise, and fewer false negatives compared to YOLOv8s.

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 further confirm its superior localization precision and robustness in dense UAV scenes.

Despite these promising results, challenges remain. As evidenced in the confusion matrix and class-wise AP breakdown, small categories such as Bicycle, Tricycle, and A-tricycle still suffer from misclassification and lower recall, largely due to their similar visual patterns and scale variability. This limitation prompts future work to explore semantic-level fusion, adaptive receptive fields, and cross-scale attention mechanisms.

In summary, DCS-YOLOv8 offers a lightweight yet powerful solution for UAV-based small object detection, demonstrating state-of-the-art performance with improved efficiency, and provides a strong foundation for further research into scale-sensitive detection tasks.

5. Conclusion

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) image detection presents persistent challenges, primarily due to the prevalence of small-scale targets, complex and cluttered backgrounds, and variable lighting conditions. These factors often result in high rates of missed detections and false positives, limiting the effectiveness of conventional object detection frameworks. In response, this study proposes DCS-YOLOv8—a specialized object detection model optimized for UAV-based scenarios with an emphasis on small object recognition.

Built upon the YOLOv8 architecture, DCS-YOLOv8 integrates two core modules: C2f-DCAM, which fuses local and global contextual features via dynamic convolution and attention mechanisms; and SCDown, a lightweight spatial downsampling strategy that reduces computational overhead while preserving spatial detail. Additionally, the model incorporates a high-resolution detection head (P2) to enhance feature extraction for small targets. To improve loss optimization across diverse object scales, the traditional CIoU loss function is replaced with the proposed Scale-based Dynamic Balanced IoU (SDBIoU), enabling dynamic adjustment of loss weights based on target size and spatial distribution.

While experimental results on the VisDrone2019 dataset demonstrate significant improvements in precision, recall, and mAP metrics compared to baseline and state-of-the-art models, practical deployment still faces challenges. Specifically, although the model achieves competitive accuracy, its inference latency on embedded hardware platforms such as the RK3588 remains suboptimal, necessitating further optimization for low-resource environments.

Looking ahead, future work will focus on three key directions: (1) extending the evaluation of DCS-YOLOv8 to additional aerial image datasets with varied geographic and environmental characteristics; (2) investigating the model’s robustness under adverse weather conditions such as rain, fog, or low illumination; and (3) refining the DCAM module and backbone design to further reduce model complexity without compromising detection accuracy. These efforts aim to enhance the generalizability and deployment readiness of DCS-YOLOv8 for real-world UAV applications in smart cities, environmental monitoring, and emergency response.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z.Z and Z.J.Y; Methodology,X.Z.Z and Z.J.Y; Software,X.Z.Z and Z.J.Y; Validation, X.Z.Z; Formal analysis,X.Z.Z,; Investigation, Z.J.Y ; Resources,Z.J.Y and H.C.Z; Writing—original draft, X.Z.Z; Writing—review and editing,Z.J.Y and H.C.Z; Supervision,Z.J.Y; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Duotao Pan for the operation of the experiment in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adil, M.; Song, H.; Jan, M.A.; Khan, M.K.; He, X.; Farouk, A.; Jin, Z. UAV-Assisted IoT Applications, QoS Requirements and Challenges with Future Research Directions. ACM Computing Surveys 2024, 56, 35. [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Wei, Z. Remote Sensing Image Classification Based on a Cross-Attention Mechanism and Graph Convolution. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2020. [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Zhu, M.; Ren, H.; Emam, M. Small Object Detection Method Based on Weighted Feature Fusion and CSMA Attention Module. Electronics 2022. [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Hu, Y.; Li, W.; Yang, F. Improved YOLOv8 algorithms for small object detection in aerial imagery. Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences 2024, 36. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, T.; Jiao, J.L. Remote Sensing Object Detection Meets Deep Learning: A metareview of challenges and advances. Geoscience and remote sensing 2023, 11, 8–44. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Xi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Y.; Tan, F.; Hou, Q. Infrared Small Target Detection Based on Local Contrast Measure With a Flexible Window. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, 21. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dong, Y.; Shen, L.; Liu, Y.; Pei, Y.; Yang, H.; Zheng, L.; Ma, J. Development and challenges of object detection: A survey. Neurocomputing 2024, 598, 23. [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Ni, J.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, Y.; Cao, W. A Survey of Object Detection for UAVs Based on Deep Learning. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 29. [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision, 2015.

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich Feature Hierarchies for Accurate Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2014, pp. 580–587. [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis & Machine Intelligence 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision & Pattern Recognition, 2016.

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLO9000: Better, Faster, Stronger. IEEE 2017, pp. 6517–6525.

- Terven, J.; Cordova-Esparza, D.M.; Romero-Gonzalez, J.A. A Comprehensive Review of YOLO Architectures in Computer Vision: From YOLOv1 to YOLOv8 and YOLO-NAS. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction 2023, 5, 1680–1716. [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Zhu, Z.; Meng, Q. Transformer in Computer Vision. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Computer Science, Electronic Information Engineering and Intelligent Control Technology (CEI), 2021, pp. 178–188. [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Pan, X.; Song, S.; Li, L.E.; Huang, G. Vision Transformer with Deformable Attention 2022.

- Shah, S.; Tembhurne, J. Object detection using convolutional neural networks and transformer-based models: a review. Journal of Electrical Systems and Information Technology 2023, 10, 1–35. [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Elmekki, H.; Pedrycz, R.W. A comprehensive survey on applications of transformers for deep learning tasks. Expert Systems with Application 2024, 241, 122666.1–122666.48. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhang, L. SL-YOLO: A Stronger and Lighter Drone Target Detection Model 2024.

- Khalili, B.; Smyth, A.W. SOD-YOLOv8 – Enhancing YOLOv8 for Small Object Detection in Traffic Scenes 2024.

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement. arXiv e-prints 2018.

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollar, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection. IEEE Computer Society 2017. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Tang, H.; He, S.; Yu, Q.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, N. Performance Validation of Yolo Variants for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the BIC 2021: 2021 International Conference on Bioinformatics and Intelligent Computing, 2021.

- Wei, L.; Tong, Y. Enhanced-YOLOv8: A new small target detection model. Digital Signal Processing 2024, 153, 104611. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Cui, C.; Ji, Y.; Li, X.; Li, S. YOLOv8-MPEB small target detection algorithm based on UAV images. Heliyon 2024, 10, 18. [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, Y.; Zhao, S.; Song, L.; Yue, X.; Shan, Y. UniRepLKNet: A Universal Perception Large-Kernel ConvNet for Audio, Video, Point Cloud, Time-Series and Image Recognition. IEEE 2023.

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, P.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Ye, R.; Ren, D. Distance-IoU Loss: Faster and Better Learning for Bounding Box Regression. arXiv 2019.

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, P.; Ren, D.; Liu, W.; Ye, R.; Hu, Q.; Zuo, W. Enhancing Geometric Factors in Model Learning and Inference for Object Detection and Instance Segmentation 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Ren, W.; Zhang, Z.; Jia, Z.; Wang, L.; Tan, T. Focal and Efficient IOU Loss for Accurate Bounding Box Regression 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, S.; Wu, J.; Su, X.; Hai, N.; Huang, X. Pinwheel-shaped Convolution and Scale-based Dynamic Loss for Infrared Small Target Detection 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Wen, L.; Du, D.; Bian, X.; Fan, H.; Hu, Q.; Ling, H. Detection and Tracking Meet Drones Challenge. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2022, 44, 7380–7399. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Vasconcelos, N. Cascade R-CNN: High Quality Object Detection and Instance Segmentation. IEEE 2021. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows 2021.

- Duan, K.; Bai, S.; Xie, L.; Qi, H.; Huang, Q.; Tian, Q. CenterNet: Keypoint Triplets for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2019, pp. 6568–6577. [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Xu, Y. MPDIoU: A Loss for Efficient and Accurate Bounding Box Regression 2023.

- Tahir, N.U.A.; Long, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Asim, M.; Elaffendi, M. PVswin-YOLOv8s: UAV-Based Pedestrian and Vehicle Detection for Traffic Management in Smart Cities Using Improved YOLOv8. Drones (2504-446X) 2024, 8. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pan, F.; Li, Z.; Xin, X.; Li, W. CoT-YOLOv8: Improved YOLOv8 for Aerial images Small Target Detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 China Automation Congress (CAC), 2023, pp. 4943–4948. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, G.; Wan, D.; Wang, Z.; Dong, J.; Lin, S.; Deng, L.; Liu, H. DS-YOLO: A dense small object detection algorithm based on inverted bottleneck and multi-scale fusion network. Microelectronics Journal 2024, 4.

Figure 1.

YOLOv8 Network Architecture, comprising the following modules: (1) C2F module, (2) Bottleneck layer, (3) Convolutional layer (Conv), (4) Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast (SPPF), (5) Detection layer.

Figure 1.

YOLOv8 Network Architecture, comprising the following modules: (1) C2F module, (2) Bottleneck layer, (3) Convolutional layer (Conv), (4) Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast (SPPF), (5) Detection layer.

Figure 2.

A schematic diagram of our proposed dynamic convolution (DCAM).

Figure 2.

A schematic diagram of our proposed dynamic convolution (DCAM).

Figure 5.

Information regarding the manual annotation process for objects in the VisDrone2019dataset.

Figure 5.

Information regarding the manual annotation process for objects in the VisDrone2019dataset.

Figure 6.

(a) and (b) show the training epochs of DCS-YOLOv8’s and .

Figure 6.

(a) and (b) show the training epochs of DCS-YOLOv8’s and .

Figure 7.

(a) Confusion matrix of DSC-YOLOv8; (b) confusion matrix of YOLOv8s.

Figure 7.

(a) Confusion matrix of DSC-YOLOv8; (b) confusion matrix of YOLOv8s.

Figure 8.

Feature activation maps generated by (a) the baseline model, (b) YOLOv8s, and (c) the proposed DCS-YOLOv8 under complex UAV scenarios, including dense occlusion, background clutter, and low illumination. Compared to (a) and (b), DCS-YOLOv8 exhibits more concentrated and context-aware attention, enabling more accurate identification of small and obscured objects.

Figure 8.

Feature activation maps generated by (a) the baseline model, (b) YOLOv8s, and (c) the proposed DCS-YOLOv8 under complex UAV scenarios, including dense occlusion, background clutter, and low illumination. Compared to (a) and (b), DCS-YOLOv8 exhibits more concentrated and context-aware attention, enabling more accurate identification of small and obscured objects.

Figure 9.

Detection results produced by (a) the baseline model, (b) YOLOv8s, and (c) DCS-YOLOv8 across various real-world aerial scenarios such as high-altitude views, occluded urban scenes, and low-light environments. DCS-YOLOv8 outperforms the other models in detecting small, overlapping, and visually ambiguous objects, while maintaining better localization accuracy and fewer false positives.

Figure 9.

Detection results produced by (a) the baseline model, (b) YOLOv8s, and (c) DCS-YOLOv8 across various real-world aerial scenarios such as high-altitude views, occluded urban scenes, and low-light environments. DCS-YOLOv8 outperforms the other models in detecting small, overlapping, and visually ambiguous objects, while maintaining better localization accuracy and fewer false positives.

Figure 10.

Hardware setup of the real-time UAV detection system integrating DCS-YOLOv8. (a) for DJI Mavic 3 drone, (b) for Orange Pi RK3588 hardware

Figure 10.

Hardware setup of the real-time UAV detection system integrating DCS-YOLOv8. (a) for DJI Mavic 3 drone, (b) for Orange Pi RK3588 hardware

Figure 11.

Detection results of DCS-YOLOv8 under different UAV flight altitudes. (a) contains dense, large-scale targets such as vehicles; (b) shows sparse, small-scale targets like pedestrians and riders. Large objects are detected reliably across altitudes, while small object detection benefits from lower-altitude imaging.

Figure 11.

Detection results of DCS-YOLOv8 under different UAV flight altitudes. (a) contains dense, large-scale targets such as vehicles; (b) shows sparse, small-scale targets like pedestrians and riders. Large objects are detected reliably across altitudes, while small object detection benefits from lower-altitude imaging.

Table 1.

Detection results of YOLOv8s with different bounding box loss functions, shown as percentages (best outcomes in bold).

Table 1.

Detection results of YOLOv8s with different bounding box loss functions, shown as percentages (best outcomes in bold).

| Metrics |

Precision |

Recall |

|

|

| CIoU |

51.8 |

39.4 |

40.6 |

24.3 |

| DIoU |

52 |

38.9 |

40.6 |

24.5 |

| EIoU |

49.8 |

39.4 |

40 |

24.3 |

| MPIoU[35] |

52.1 |

39 |

40.7 |

23.9 |

| SDBIoU(d=0.5) |

51.1 |

39.5 |

40.4 |

24.3 |

| SDBIoU(d=0.7) |

51.2 |

39.3 |

40.2 |

24.1 |

| SDBIoU(d=0.3) |

51.6 |

40.1 |

40.8 |

24.5 |

Table 2.

Different YOLO models’ results, presented as percentages.(The best-performing outcomes are highlighted in bold).

Table 2.

Different YOLO models’ results, presented as percentages.(The best-performing outcomes are highlighted in bold).

| Models |

Precision |

Recall |

|

|

Time/ms |

Parameter/

|

| YOLOv3 |

53.8 |

43.1 |

42.2 |

23.2 |

210 |

18.4 |

| YOLOv5s |

46.7 |

34.9 |

34.5 |

19.4 |

14.1 |

12.0 |

| YOLOv7 |

51.6 |

42.3 |

40.2 |

21.9 |

73.3 |

1.7 |

| YOLOv8n |

45.9 |

34.2 |

34.5 |

19.8 |

5.7 |

3.1 |

| YOLOv8s |

51.8 |

39.4 |

40.6 |

24.3 |

7.1 |

11.1 |

| YOLOv8m |

55.8 |

42.6 |

44.5 |

26.6 |

16.8 |

25.9 |

| YOLOv10n |

45.5 |

33.5 |

34 |

19.8 |

8 |

2.7 |

| YOLOv10s |

51 |

39.4 |

40.8 |

24.6 |

7.6 |

8.1 |

| PVswin-YOLO[36] |

54.5 |

41.8 |

43.3 |

26.4 |

8.8 |

10.1 |

| CoT-YOLO[37] |

53.2 |

41.1 |

42.7 |

25.7 |

12.2 |

10.6 |

| DS-YOLO[38] |

52.4 |

41.6 |

43.1 |

26.0 |

19.7 |

9.3 |

| DCS-YOLOv8 |

54.2 |

42.1 |

44.5 |

26.9 |

10.1 |

9.9 |

Table 3.

Results from different widely used models, presented as percentages.(The best-performing outcomes are highlighted in bold).

Table 3.

Results from different widely used models, presented as percentages.(The best-performing outcomes are highlighted in bold).

| Models |

|

|

| Faster R-CNN[11] |

36.6 |

21.1 |

| Swin Transformer[33] |

39.7 |

23.1 |

| CenterNet [34] |

39.2 |

22.7 |

| Cascade R-CNN [32] |

39.4 |

24.2 |

| DCS-YOLOv8 |

44.5 |

26.9 |

Table 4.

Comparative experiments between the enhanced model and YOLOv8s across various categories, with percentages presented (best-performing outcomes highlighted in bold).

Table 4.

Comparative experiments between the enhanced model and YOLOv8s across various categories, with percentages presented (best-performing outcomes highlighted in bold).

| Models |

Pedestrian |

People |

Bicycle |

Car |

Van |

Truck |

Tricy |

A-tricy |

Bus |

Motor |

|

| YOLOv8s |

44.2 |

34.3 |

13.9 |

80 |

45.5 |

40.2 |

28.5 |

16.6 |

57.8 |

44.8 |

40.6 |

| YOLOv8s-SDBIoU |

44.1 |

34.0 |

14.4 |

79.6 |

45.8 |

38.4 |

29.7 |

15.8 |

60.9 |

44.9 |

40.8 |

| YOLOv8s-SDBIoU-P2 |

50 |

40.7 |

16.6 |

83.3 |

46.7 |

39.7 |

29.1 |

16 |

60.5 |

50.6 |

43.3 |

| YOLOv8s-SDBIoU-P2-DCAM |

51 |

40.8 |

16.9 |

83.8 |

47.5 |

39.3 |

32.3 |

17 |

59.4 |

50.5 |

43.9 |

| YOLOv8s-SDBIoU-P2-DCS-Net |

51.5 |

42.5 |

17.2 |

83.8 |

48.5 |

39.4 |

33.3 |

18.1 |

59.8 |

50.6 |

44.5 |

Table 5.

Detection results following the adoption of different improvement strategies, presented as percentages.

Table 5.

Detection results following the adoption of different improvement strategies, presented as percentages.

| Baseline |

SDBIOU |

P2 |

DCAM |

SCDown |

Precision |

Recall |

|

|

Time/ms |

Parameter/

|

| ✓ |

|

|

|

|

51.8 |

39.4 |

40.6 |

24.3 |

7.1 |

11.1 |

| ✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

51.6 |

40.1 |

40.8 |

24.5 |

5.5 |

11.1 |

| ✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

53.9 |

41.2 |

43.3 |

26.1 |

6.6 |

10.6 |

| ✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

54.8 |

41.8 |

43.9 |

26.5 |

9.7 |

11.3 |

| ✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

54.2 |

42.1 |

44.5 |

26.9 |

10.1 |

9.9 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).