1. Introduction

Cider, an alcoholic beverage produced through the fermentation of apple juice, has experienced a significant rise in popularity within the alcoholic beverage market. Traditional cider-producing and consuming countries such as Spain, England, France and Ireland have increased the production and consumption of this beverage. Additionally, cider has expanded into new markets, including the United States, Australia and Asia [

1]. In Argentina, cider production is primarily concentrated in the North Patagonian region, where most apple orchards are located. Reflecting global trends, this industry is becoming an increasingly important segment of the apple fruit sector, partly due to the decline in fresh apple exports and the consequent reduction in fresh fruit prices [

2].

Unlike what happens in other countries, Argentine cider has been traditionally produced from apple varieties whose main use is fresh consumption. Moreover, the use of discarded apples that do not meet the quality standards required to be sold on the international market is also a particularly common practice in local cider-making. Regarding the yeasts used in this industry, spontaneous fermentations or conducted fermentations using commercial cultures are employed. In recent years, the use of other apple varieties and even new local yeasts have been evaluated with the aim of differentiating the product and increasing its economic value [

3,

4,

5].

An increasingly common strategy to enhance the flavor complexity of ciders is the inoculation of apple musts with pure cultures of yeasts belonging to

Saccharomyces genus selected according to their metabolic and technological abilities [

6,

7]. More recently, different non-

Saccharomyces yeast strains were also evaluated because of their ability to produce specific cider volatile compounds [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. In a few cases, mixed cultures of two non-

Saccharomyces strains [

12] or a combination of

S. cerevisiae and a non-

Saccharomyces yeast were also proposed [

13,

14,

15].

Among non-

Saccharomyces yeast species,

Pichia kudriavzevii has gained attention. This species is recognized for its ability to degrade organic acids, release hydrolases and flavor compounds, and exhibit probiotic properties, making it a promising starter culture in the beverage industry [

15]. While it is commonly associated with wine due to its prevalence in vineyards and wineries, it has also been isolated from other substrates such as apple surfaces, spontaneous cider and Baijiu fermentations, and sourdough in recent years [

5,

14,

16,

17]. Strains of

P. kudriavzevii have been reported to enhance the aromatic profiles of wines [

18,

19,

20] and also contribute to the production of high-quality ciders when used in mixed cultures [

13,

14].

The ability of

P. kudriavzevii to degrade malic acid in wine [

21,

22,

23,

24] makes it a promising species for the production of cider from musts with a high concentration of this particularly pungent organic acid. L(-)Malic acid is the predominant component of the non-volatile organic acid fraction in apples. Its concentration is influenced by apple variety, maturity, and climatic conditions. Apples grown in cooler regions tend to have higher levels of L(-)malic acid due to a lower respiratory quotient compared to those from warmer areas [

25]. This explains the high content of this acid (>10 g L⁻¹) in the most cultivated varieties in Argentina's North Patagonia. From a sensory perspective, malic acid can be harsh at high concentrations. Microbiologically, it is unstable because lactic acid bacteria can metabolize it, leading to the formation of undesirable compounds. One common strategy in winemaking, and much less explored in cider making, is to induce malolactic fermentation using selected lactic acid bacteria before bottling, which helps to reduce malic acid content and, according to some producers, enhances the beverage's characteristics. However, other studies report that malolactic fermentation can be a challenging process to control, potentially leading to a deterioration in the quality of the final product [

26]. In this context, the use of starter cultures containing

P. kudriavzevii strains seems interesting.

In a previous study, Mazzucco et al. [

27] examined

P. kudriavzevii strains isolated from different substrates in the Patagonian region—wine, cider, and natural environments—and demonstrated that the cider strain

P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651 could degrade L(-)malic acid as its sole carbon source and consume malic acid present in acidic apple musts. This strain also stood out for its high fermentative capacity and fructose consumption. Additionally, the indigenous wine strain

S. cerevisiae ÑIF8 demonstrated some capacity to consume malic acid while also exhibiting a high fermentative ability.

In this study, pure and mixed fermentations were carried out using P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651 and S. cerevisiae ÑIF8 to determine the optimal fermentation strategy for producing ciders with low acidity and distinct physicochemical and aromatic profiles - key attributes when selecting starter cultures for cider production from acidic apples. The simultaneous inoculation at a 1:1 ratio is proposed for further pilot-scale testing in natural (non sterile) musts due to the physicochemical and aromatic profile of the resulting ciders and the practicality of the strategy. Additionally, reducing malic acid levels in ciders could lessen the need for added sugar during the final adjustment stage to balance the harshness of malic acid, resulting in a healthier beverage and providing cost savings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Yeasts and Growth Conditions

One

P. kudriavzevii strain (NPCC1651) and one

S. cerevisiae strain (ÑIF8 strain) previously isolated from the North Patagonian Region (Argentina) and tested in their capability for cider production [

27] were used in this study.

P. kudriavzevii strain was isolated from spontaneous cider [

5] and

S. cerevisiae strain was obtained from a Patagonian wine cellar [

21]. Yeasts were conserved in vials containing YEPD (g L-1: yeast extract 10, glucose 20, peptone 20, and agar 20, pH 4.5) - glycerol 20% v/v. The activation was carried out by spreading onto YEPD-agar and incubation at 25°C for 24 hours.

P. kudriavzevii strain is deposited in the North Patagonian Culture Collection (NPCC), Neuquén, Argentina.

2.2. Antagonist Activity

Antagonist activity between

P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651 and

S. cerevisiae ÑIF8 was determined using the seeded-agar-plate technique on YEPD-MB medium (w/v: 1% yeast extract, 2% glucose, 2% peptone, 2% agar, 0.0003% methylene blue) buffered at pH 4.6 with 0.5 M phosphate–citrate as described by Lopes and Sangorrín et al. [

28]. The collection strains K2-type killer

S. cerevisiae NCYC 738 and

Candida glabrata NPCC106 were used as a control of killer and sensitive yeasts, respectively.

2.3. Laboratory-Scale Fermentations in Sterile Apple Must

2.3.1. Fermentation Trial

Apple juice (12.6°Brix, 47.0 g/L glucose and 92.7 g/L fructose, 25 g/L sucrose, 9.9 g/L sorbitol, 7.67 g/L malic acid, pH 3.21) was prepared from Granny Smith apples harvested during 2023 from orchards located in the North Patagonian region (Río Negro province, Argentina), sulfited (100 mg L-1 potassium metabisulfite) and sterilized (120 °C, 20 min).

P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651 and

S. cerevisiae ÑIF8 strains were activated and pre-cultured in 50 mL YEPD medium at 28°C for 24 h with agitation (150 rpm), separated by centrifugation, washed with sterile water, and inoculated in 400 mL sterilized apple juice. Yeast inoculation strategies consisted of six fermentation tests (

Table 1): (1) single inoculation with

P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651 strain (2x10

6 cell/mL) (P); (2) single inoculation with

S. cerevisiae ÑIF8 strain (2x10

6 cell/mL) (S); (3) simultaneous inoculation with

S. cerevisiae ÑIF8 and

P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651 at a cell concentration ratio of 1:1 (2x10

6 cell/mL: 2x10

6 cell/mL) (Sim 1:1); (4) simultaneous with

S. cerevisiae ÑIF8 and

P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651 at a cell concentration ratio of 1:10 (1x10

6 cell/mL: 1x10

7 cell/mL) (Sim 1:10); (5) sequential inoculation with

S. cerevisiae ÑIF8 48 h after inoculation with

P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651 at a ratio of 1:1 (2x10

6 cell/mL: 2x10

6 cell/mL) (Seq P-S); and (6) sequential inoculation with

P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651 48 h after inoculation with

S. cerevisiae ÑIF8 at a ratio of 1:1 (2x10

6 cell/mL: 2x10

6 cell/mL) (Seq S-P). All fermentations were carried out at 20°C in duplicate using an incubator. The fermentations evolution was followed daily by measuring °Brix using a refractometer (Gery Anderson) until constant values. After this point, total reducing sugars were daily evaluated by the DNS method [

29] until the end of the processes (less than 2 g/L total reducing sugars). The sterility of the must was confirmed through microscopic observations (absence of bacterial cells) at various fermentation stages.

2.3.2. Kinetic Parameters

Kinetic parameters were calculated from each fermentation individually using °Brix measure daily in the system. Two models were tested:

i. Exponential decay function previously used by Arroyo-López et al. [

30]: Y=D+S∗e−K∗t. Where Y is the final °Brix value, t is the time (h), D is a specific value when t → ∞, S is the estimated value of change, and K is the kinetic constant (h−1).

ii. Sigmoid or altered Gompertz decay function, used previously by Lambert and Pearson [

31]: Y=A+C⁎e−e^(K⁎ (t−M)). Where Y is °Brix still present in must, t is the time (h), A is the lower asymptote when t tends to infinity (t→∞), K is the kinetic constant (h−1), C is the distance between the upper and lower asymptote, and M is the time when the inflection point is obtained (50% of the total °Brix variation).

Analysis was carried out using the non-linear module of the Statistica 7.0 software package and its Quasi-Newton option (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA), minimizing the sum of squares of the difference between experimental data and the fitted model. Fit adequacy was checked by the proportion of variance explained by the model (r2) respect to experimental data. The two equation were tested and the function with the highest r2 (r2>0.98) was chosen. ANOVA and Tukey honest significant difference tests (HSD) with α = 0.05 were performed by mean comparison of kinetic parameters. The data normality and variance homogeneity in the residuals were verified by Lilliefors and Bartlet tests respectively.

2.3.3. Microbiological Counts

Viable counts of S. cerevisiae and P. kudriavzevii were directly determined based on their different colony morphology on WL Nutrient Agar (Merck) plates. Diluted cider samples (corresponding to 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 11, and 15 days of fermentation) were spread on the WL plates. The plates were incubated at 25°C for 2 days to allow the yeast cell to form colonies and the colony-forming units per milliliter (cuf/mL) were calculated.

2.3.4. Sugar Utilization

Glucose and fructose concentration were measured at various stages of the alcoholic fermentation process using a commercial kit (Megazyme, Ireland). Kinetic parameters of glucose and fructose consumption were calculated from each fermentation individually. Two models were tested:

i. Exponential decay function proposed by Arroyo-López et al. [

30]: Y=D+S∗e−K∗t. In this assay Y is the amount of sugar (glucose, fructose or sucrose) still present in the must, t is the time (h), D is a specific value when t → ∞ (sugar concentration at the end of the fermentation), S is the estimated value of change (total sugar consumption), and K is the kinetic constant or substrate (sugar) consumption rate (h−1).

ii. Sigmoid or altered Gompertz decay function proposed by Lambert and Pearson [

31]: Y=A+C⁎e−e^(K⁎ (t−M)). In this assay Y is the amount of sugar still present in the must, t is the time (h), A is the lower asymptote when t tends to infinity (t→∞) (sugar concentration at the end of the fermentation), K is the kinetic constant or substrate consumption rate (h−1), C is the distance between the upper and lower asymptote (total sugar consumption), and M is the time when the inflection point is obtained (50% of the total sugar variation). The data analysis was carried out as described in

Section 2.2. In addition, the time needed to decrease 10%, 50% and 90% of the sugar of the must was calculated by solving the “t” variable from the exponential (i) or sigmoid equation (ii), as corresponding. These parameters represent t10, t50 and t90, respectively.

2.4. Chemical Analysis of the Ciders

Ethanol, glycerol, methanol, sorbitol, glucose, fructose, and organic acids (citric, malic, acetic, lactic and succinic) were determined by HPLC using a Liquid Chromatograph Agilent 1260 (Quat Pump VL, ALS, TCC, DAD) with detector RID (55 °C) (for ethanol, glycerol, methanol, sorbitol, glucose and fructose) and DAD (214 nm) (for malic, acetic, citric, succinic and lactic acids). The stationary phase was performed with HIPLEX-H column (300×7.7 mm) and mobile phase with isocratic gradient (100% H2SO4 0.001M flux: 0.4 mL min-1). Sucrose was determined by RID detector. The stationary phase was performed with a ZORBAX Carbohydrate Analysis Column (150x4.6 mm) and mobile phase with isocratic gradient (75% acetonitrile in water flux 1mL min-1). The samples were filtered through a 0.22 μm nylon filters and injected onto the chromatographic column in duplicate. The determinations were conducted following the Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, in accordance with the specifications provided by the column supplier. Calibration curves were prepared using HPLC-grade standard solutions (Sigma). pH was measured using a (Oakton) pHimeter.

Higher alcohols, esters, acetaldehyde and terpenes were determined by headspace solid-phase-microextraction sampling (SPME) using 50/30 μm DVB/CAR/PDMS fibers (Sigma-Aldrich) and GC according to Rojas et al. [

32]. Aliquots of 1.5 mL of the samples were placed in 15 mL vials and 0.3 g of NaCl and 15 μL of 0.1% (v/v) 2-octanol in ethanol were added as internal standard. The vials were closed with screwed caps and 3 mm thick teflon septa. Fibers were injected through the vial septum and exposed to the headspace for 30 min and then desorbed during 10min in an HP 7890 series II gas chromatograph equipped with an HP Innowax column (Hewlett-Packard) (length, 60 m; inside diameter, 0.32 mm; film thickness, 0.50 μm). The injection block and detector (FID) temperatures were kept constant at 220 and 250 °C, respectively. The oven temperature was programmed as follows: 40 (7 min) to 180 °C at 5 °C min−1, and 200 to 260 °C at 20 °C min−1 and kept 15 min at 260 °C. Total running time: 75 min. The following standards were purchased from Sigma Aldrich: isobutilic alcohol, isoamylic alcohol, 1-hexanol, bencylic alcohol, 2-phenyl ethanol, ethyl acetate, isobutyl acetate, ethyl lactate, isoamyl acetate, hexyl acetate, diethyl succinate, bencyl acetate, ethyl caprylate, ethyl 3-hydroxibutanoate, 2-penylethyl acetate, 4-terpineol, limonene, linalool, nerol and geraniol. All standards were of 99% purity. Values calculated for each different compound were the average of two independent assays.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using RStudio [

33]. Mean values for chemical and kinetic parameters were compared using one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05), followed by Tukey's Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test for mean comparisons. °Brix values and glucose and fructose concentrations were fitted to obtain kinetic parameters, and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed to evaluate aromatic variables.

3. Results

3.1. Fermentations Kinetics

Laboratory-scale fermentations (400 mL) were conducted by inoculating pure or mixed (simultaneous and sequential) cultures of two regional strains belonging to the species

P. kudriavzevii and

S. cerevisiae into sterile Granny Smith apple must (

Table 1). In simultaneous fermentations, both

S. cerevisiae and

P. kudriavzevii species were inoculated at ratios 1:1 (Sim 1:1) or 1:10 (Sim 1:10), respectively. On the other hand, sequential fermentations were inoculated with

P. kudriavzevii (from the beginning) and

S. cerevisiae (after 48 h of fermentation) (Seq P-S), or vice versa (Seq S-P).

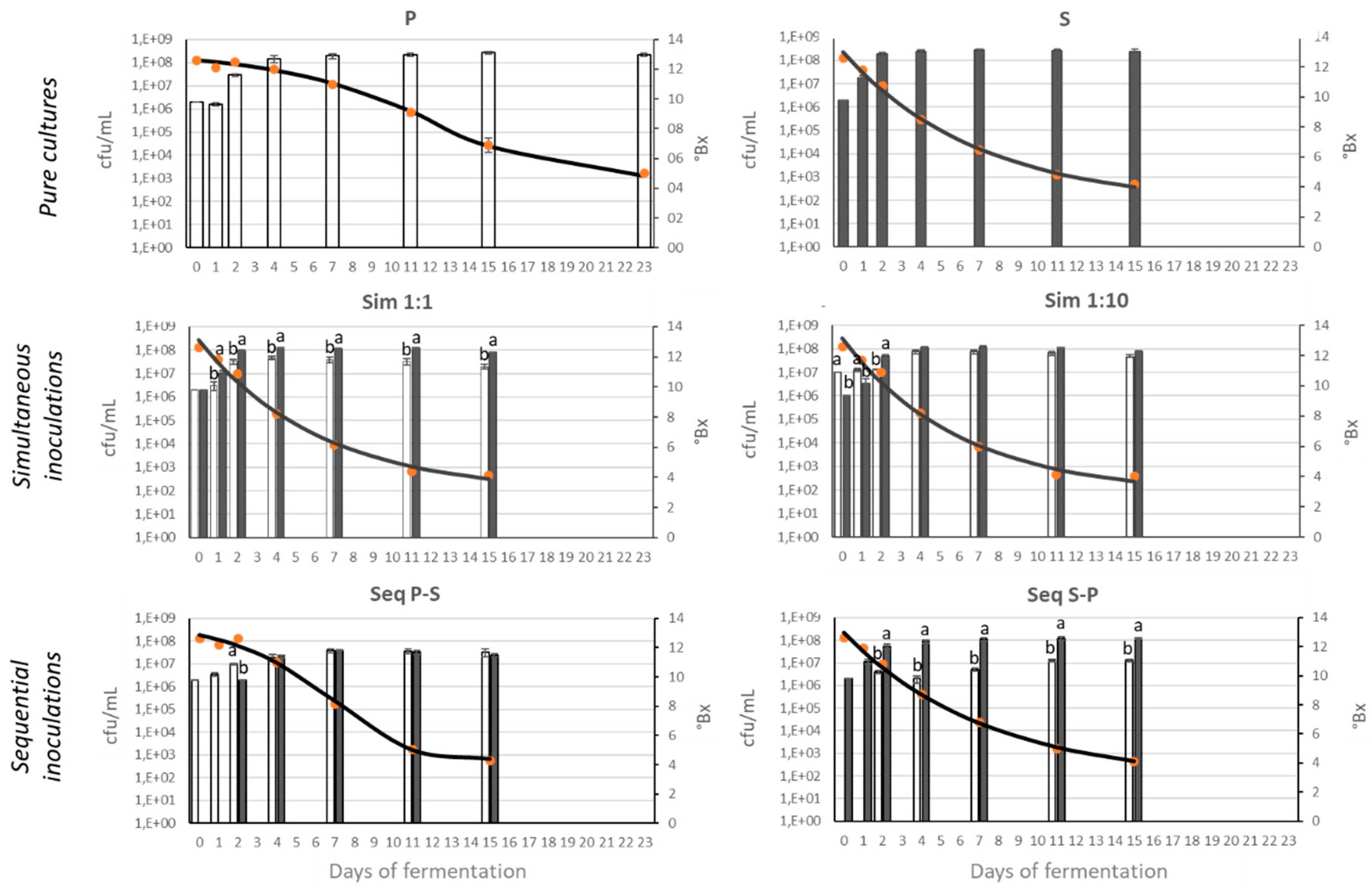

The progression of fermentations was monitored by measuring °Brix (and total reducing sugars after °Brix stabilization) and cfu/mL counts (

Figure 1). All fermentations except for those inoculated with the pure

P. kudriavzevii culture showed complete sugar consumption (less than 2 g/L of total reducing sugars) after 16 days of inoculation. In contrast, fermentations carried out by the pure

P. kudriavzevii culture took a total of 23 days to complete sugar consumption.

Bars represent yeast viable count (cfu/mL) for S. cerevisiae (gray) and P. kudriavzevii (white). Lines indicate modeled °Brix values and points indicate observed °Brix values. Different letters indicate significant differences between P. kudriavzevii and S. cerevisiae cfu/mL values on a given fermentation day (Tukey test, n=2). P: P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651; S: S. cerevisiae ÑIF8; Sim 1:1: Simultaneous fermentation by S:P ratio 1:1; Sim 1:10: Simultaneous fermentation by S:P ratio 1:10; Seq P-S: Sequential fermentation by S. cerevisiae ÑIF8 48 h after P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651; Seq S-P: Sequential fermentation by P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651 48 h after S. cerevisiae ÑIF8.

The evolution data of °Brix obtained from fermentations with

P. kudriavzevii alone (P) and with sequential inoculation initiated with

P. kudriavzevii (Seq P-S) fitted the sigmoid or modified Gompertz decay model, whereas the data for the remaining fermentation trials (S, Sim 1:1, Sim 1:10, Seq S-P) fitted the exponential decay model (

Table 2). The most notable difference among fermentations was the substrate consumption rate (parameter

K). This parameter can be compared only among fermentations that fitted the same model. For fermentations fitted to sigmoid model, those conducted with the pure culture of

P. kudriavzevii exhibited a significantly lower rate of sugar consumption (lower

K value) compared to the sequential fermentation initiated with this strain (Seq P-S). Among the fermentations fitted to exponential model, those simultaneously inoculated with the two strains (both Sim 1:1 and Sim 1:10) exhibited the highest

K values (

Table 2), possibly due to the highest yeast inoculum concentration (

Table 1).

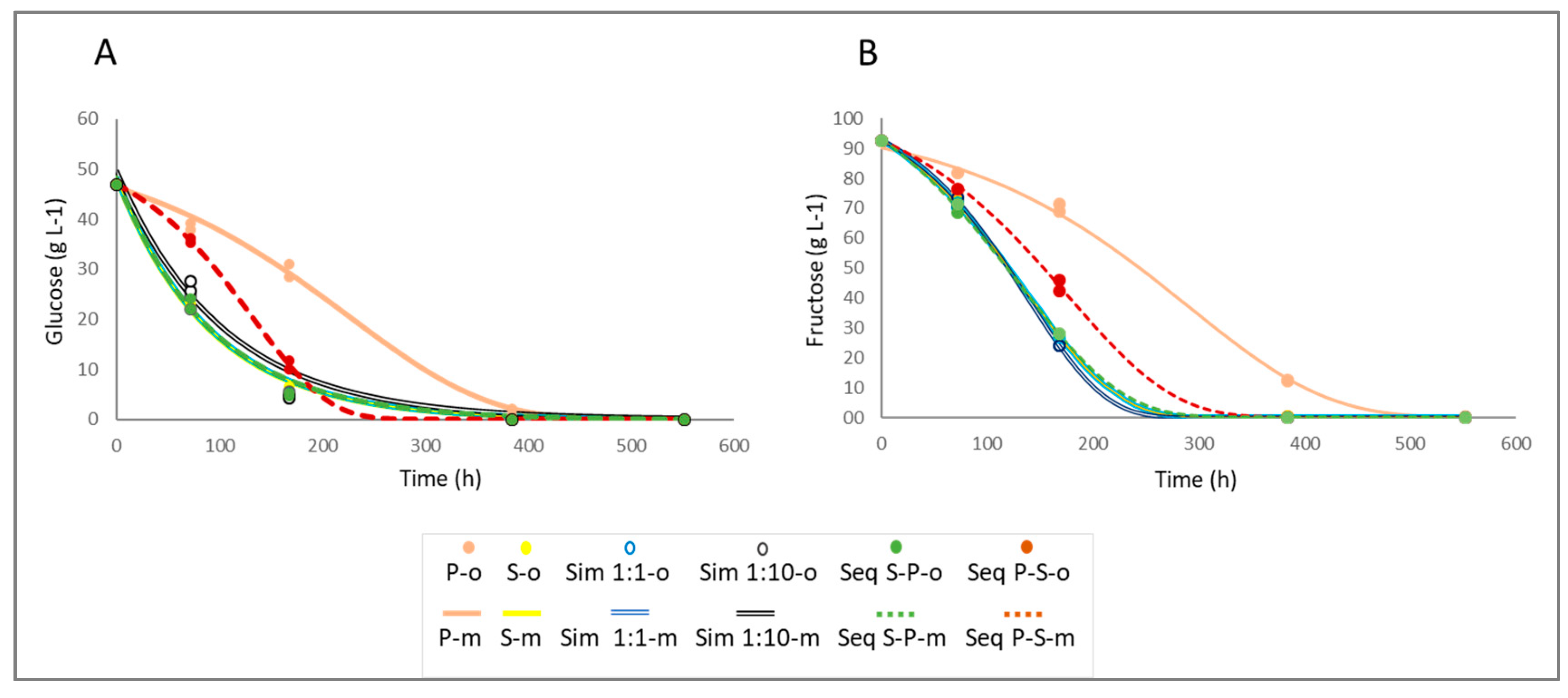

In order to evaluate the sugar consumption kinetics of the different fermentations, glucose and fructose concentrations were measured at various stages of the alcoholic fermentation (

Figure 2). As in the case of °Brix, the observed data were fitted to the modified sigmoid decay model and to the exponential decay model, and the model that showed the best fit was selected to obtain the kinetic parameters (

Table 3).

Lines represent modeled values (m) of glucose (A) and fructose (B) over time for each fermentation trial, while points indicate observed values (o). P: P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651; S: S. cerevisiae ÑIF8; Sim 1:1: Simultaneous S:P ratio 1:1; Sim 1:10: Simultaneous S:P ratio 1:10; Seq P-S: Sequential fermentation by S. cerevisiae ÑIF8 48 h after P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651; Seq S-P: Sequential fermentation by P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651 48 h after S. cerevisiae ÑIF8.

As it was observed for °Brix, glucose consumption kinetics in both, pure fermentations inoculated with

P. kudriavzvii (P) and sequential fermentation initiated with this strain (Seq P-S), fitted to the sigmoid decay model. Among them, the sequential fermentations exhibited the highest glucose consumption rate (parameter

K) (

Table 3). Conversely, for all other fermentations (S, Sim 1:1, Sim 1:10, and Seq S-P), glucose consumption kinetics fitted to an exponential decay model. Among them, the Sim 1:10 trial exhibited the lowest glucose consumption rate, with no significant differences detected among the other fermentations (

Table 3).

Regarding fructose consumption, all fermentations fitted the sigmoid decay model (

Table 3), allowing the comparison of kinetic parameters among them. The highest consumption rate for this sugar was observed in the Sim 1:10 fermentation, while the lowest one was observed in those inoculated with the pure culture of

P. kudriavzevii (P).

Finally, the times required to consume 10%, 50%, and 95% (t10, t50, and t95) of each sugar (glucose and fructose) were calculated (

Table 4). It is worth noting that these times can be compared among fermentations that fit different models. As expected, those fermentations inoculated with the pure culture of

P. kudriavzevii showed the highest values for the three parameters (t10, t50, and t95) and for the two sugars (glucose and fructose). Moreover, fermentations involving only

P. kudriavzevii during the first 48 hours (P and Seq P-S) showed the highest fructose consumption times (t50 and t95).

3.2. Fermentation Dynamics

Regarding the monitoring of cfu/mL along fermentations, a clear reduction in the total number of each species was observed in mixed fermentations compared to the pure cultures (

Figure 1). While pure cultures reached counts of 4x10

8 cfu/mL, the maximum value obtained in mixed cultures was 2x10

8 cfu/mL in simultaneous cultures (adding the cfu/mL numbers of the two species). Another interesting observation is the persistence of

P. kudriavzevii strains with notable cfu/mL numbers in the final stages of all mixed fermentations. These values were even similar to those detected for

S. cerevisiae, as in the cases of simultaneous 1:10 and sequential P-S fermentations (

Figure 1).

Specifically, in simultaneous fermentations, it was noteworthy that the inoculation of

P. kudriavzevii in a concentration ten times higher than

S. cerevisiae (Sim 1:10) resulted in similar cfu/mL values for the two species since the middle fermentation stages (day 4) until the end. In contrast, inoculation of the two species at the same concentration (Sim 1:1) led to the dominance of

S. cerevisiae over

P. kudriavzevii after 24 hours of inoculation and until the end (

Figure 1).

For the sequential fermentations, when

S. cerevisiae was added to the apple must after 48 hours of inoculation with

P. kudriavzevii (Seq P-S), the proportion of the two species in cfu/mL numbers remained consistent from day 4 until the end of the fermentation process. In contrast, when

P. kudriavzevii was added after 48 hours of inoculation with

S. cerevisiae (Seq S-P), a significantly higher proportion of

S. cerevisiae over

P. kudriavzevii was observed during the whole fermentation process (

Figure 1).

3.3. Antagonist Activity

In order to rule out the potential antagonistic activity (including killer activity) between the two evaluated yeast strains, in vitro antagonistic analyses were carried out (data not shown). No antagonistic effect was observed in assays using either P. kudriavzevii as a lawn and striked with S. cerevisiae or S. cerevisiae as a lawn and streaked with P. kudriavzevii. On the other hand, S. cerevisiae was shown to exhibit antagonistic effect on Candida glabrata sensitive strain NPCC106 and a weak sensitivity to the reference S. cerevisiae K2 killer strain. P. kudriavzevii was neither able to show antagonistic effect against the C. glabrata sensitive strain nor sensitivity to the reference S. cerevisiae K2 killer strain.

3.4. Chemical Properties of Base Ciders

The physicochemical characteristics of the base ciders are summarized in

Table 5. Among the general chemical compounds analyzed, significant differences were observed in glycerol concentrations. Base ciders fermented with pure cultures of

P. kudriavzevii and

S. cerevisiae, as well as those from the mixed Seq S-P strategy, exhibited the highest glycerol levels. Additionally, a significant decrease in sorbitol concentration (approximately 45%) was observed in all ciders compared to the uninoculated apple must.

The effect of the inoculation strategy was slightly evident in the composition of the organic acids in the base ciders. Both lactic and succinic acid concentrations were higher in ciders where

S. cerevisiae predominated (S, Sim 1:1 and Seq S-P). Volatile acidity (acetic acid) levels were higher in the ciders dominated by

P. kudriavzevii (P and Seq P-S fermentations); however, the concentration was within acceptable limits (2.5 g L−1). Contrarily, the lowest levels of this acid were found in the ciders produced exclusively by

S. cerevisiae (S). On the other hand, malic acid is the predominant acid in the apple must and ciders. The concentration of this acid decreased in all the fermentations analyzed, relative to its content in the apple must. The consumption percentages ranged from 27% in the ciders produced by the pure

P. kudriavzevii culture to 33–34% in the simultaneous (Sim 1:1 and Sim 1:10) and the sequential Seq S-P fermentations (

Table 5).

Analysis of volatile compounds of ciders, detected by GC-MS analysis, was carried out to study the effects of the different inoculation strategies on the aroma of the base ciders elaborated from the same apple must (

Table 5).

Higher alcohols are important aromatic compounds in fermented beverages, produced through the secondary metabolism of yeasts. The most abundant higher alcohols detected in the ciders were isoamyl alcohol (contributing fruity and marzipan notes), followed by isobutyl alcohol (imparting mild alcoholic aromas) and 2-phenylethanol (associated with rose and floral aromas). Base ciders fermented with the pure culture of P. kudriavzevii produced the significantly highest levels of isobutyl alcohol, while the same fermented with the pure culture of S. cerevisiae produced the significantly highest levels of 2-phenylethanol. With regard to the concentrations of isoamyl alcohol, the highest levels were observed in base ciders where S. cerevisiae predominated (S, Sim 1:1 and Seq S-P). These results position Sim 1:10 and Seq P-S fermentations as the trials that produce the base ciders with the lowest levels of total higher alcohols.

In addition to higher alcohols, esters also play a crucial role as aroma compounds in cider. The most abundant esters in the base ciders analyzed were by far ethyl acetate, followed by isoamyl acetate, benzyl acetate, ethyl hexanoate and ethyl octanoate. The comparison between the fermentation trials revealed that the base cider produced by the pure culture of

P. kudriavzevii exhibited the highest levels of total esters, especially due to the ethyl acetate concentration and, to a lesser extent, benzyl acetate and isobutyl acetate levels. Both isoamyl acetate and ethyl octanoate showed the highest concentrations in base ciders produced by simultaneous inoculations, independently of the

Saccharomyces:Pichia ratio. These ciders, along with those produced by sequential fermentation initiated with

S. cerevisiae (Seq S-P), showed the highest levels of total esters when ethyl acetate is excluded from the analysis (

Table 5).

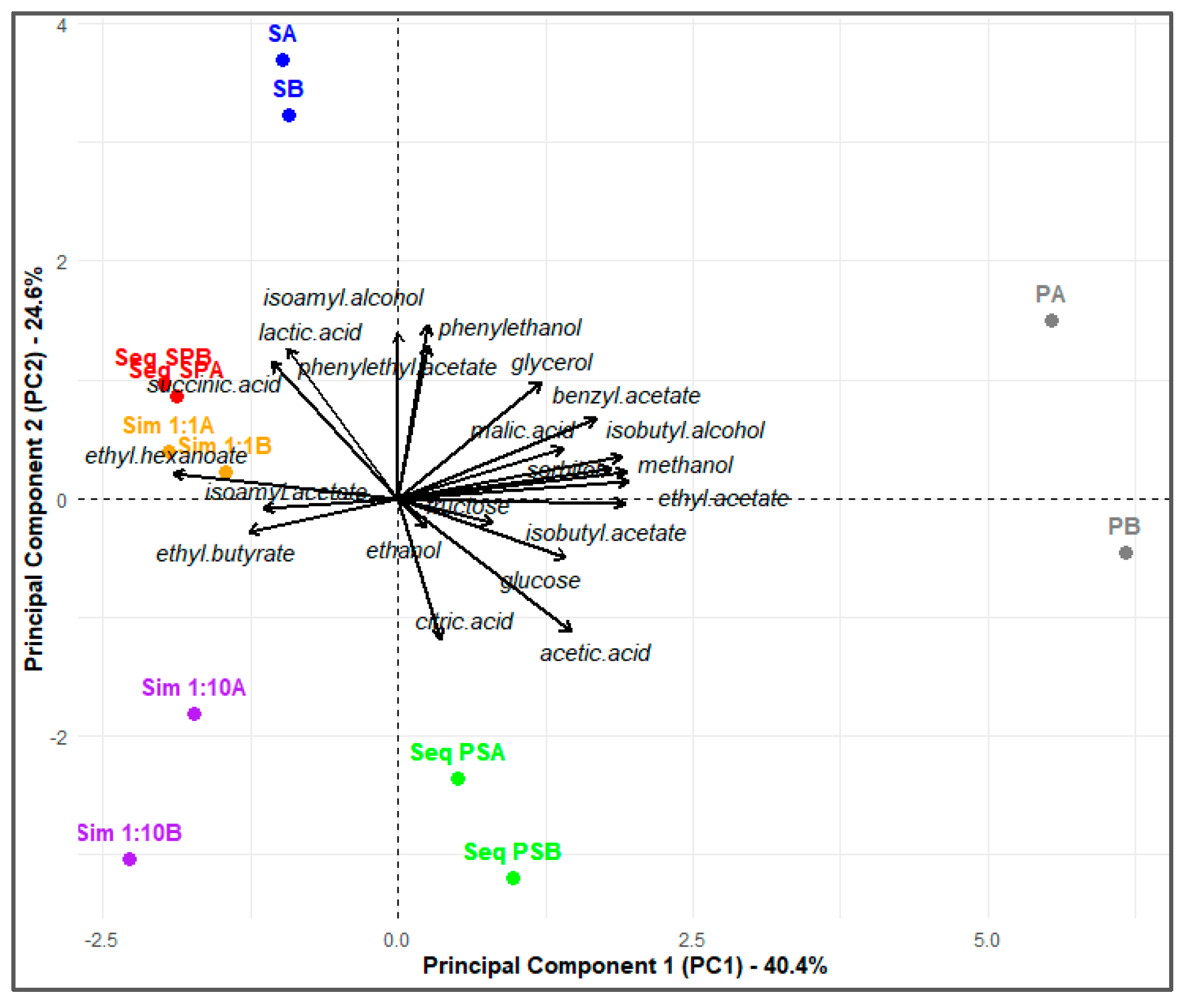

The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) visualized the influence of each yeast and inoculation method on the chemical profiles of the ciders (

Figure 3). The analysis clearly demonstrated that ciders obtained through the Sim 1:1 and Seq S-P strategies shared similar characteristics, as they were located in the same quadrant of the plot. Among the mixed fermentations, these ciders were associated with a high contribution of compounds such as glycerol, lactic and succinic acid, isoamyl alcohol, 2-phenylethanol, isoamyl acetate, and 2-phenylethyl acetate. Additionally, these strategies showed a low production of ethyl acetate. Conversely, the remaining strategies displayed distinct separations in the PCA space, emphasizing differences in the chemical profiles of the ciders. A clear separation was observed for the ciders produced through pure fermentations with

P. kudriavzevii (PA, PB) and

S. cerevisiae (SA, SB). As expected, fermentations with

P. kudriavzevii were associated with higher levels of ethyl acetate and acetic acid, while fermentations with

S. cerevisiae showed stronger contributions of 2-phenylethanol and isoamyl acetate. Another notable difference in location was observed for the sequential strategies. The Seq S-P strategy was associated with higher contributions of isoamyl alcohol, 2-phenylethyl acetate, and ethyl hexanoate, reflecting the metabolic influence of

S. cerevisiae in this strategy. Conversely, the Seq P-S strategy aligned more closely with ethyl acetate and acetic acid, demonstrating the stronger influence of

P. kudriavzevii in these fermentations.

These results demonstrate that the choice of fermentation strategy significantly influences the metabolic contributions of S. cerevisiae and P. kudriavzevii, ultimately shaping the aromatic profiles and quality of the resulting ciders.

Finally, terpenes and volatile phenols were below the detection limit of the equipment in all the analyzed products.

Projection of the vectors onto the two principal components (PC1-PC2) plane. PC1 and PC2 account for 40.4% and 24.6% of the total variation, respectively. The vectors represent the variables influencing cider characteristics and their lengths are proportional to the percentage of variability explained by PC1 and PC2. P: P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651; S: S. cerevisiae ÑIF8; Sim 1:1: Simultaneous S:P ratio 1:1; Sim 1:10: Simultaneous S:P ratio 1:10; Seq P-S: Sequential fermentation by S. cerevisiae ÑIF8 48 h after P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651; Seq S-P: Sequential fermentation by P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651 48 h after S. cerevisiae ÑIF8. A and B indicate duplicates of each fermentation trial.

4. Discussion

In recent years, the role of non-

Saccharomyces yeasts in cidermaking has been re-evaluated, leading to several studies exploring the use of controlled mixed fermentations involving

Saccharomyces and various non-

Saccharomyces yeast species from wine and cider environments (7, 34, 10, 11). Among the non-

Saccharomyces species,

Pichia kudriavzevii has raised particular interest due to its contributions to organic acid degradation and the release of hydrolases and flavor compounds [

15]. While these studies have predominantly focused on wine fermentations, more recently, some authors have begun to explore the application of

P. kudriavzevii in cider production [

13,

14]. In the present study, we evaluated different strategies for inoculation of an acidic apple must using the regional strains

S. cerevisiae ÑIF8 and

P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651, with the goal of producing ciders with reduced acidity and distinct aromatic profiles.

Fermentation Kinetics and Sugar Utilization

The utilization of sugar indicates the capability of cultures during alcoholic fermentation and the substrate transformation ability of yeasts. Therefore, sugar utilization was evaluated by measuring °Brix and analyzing the consumption kinetics of glucose and fructose —the latter being the predominant sugar in apple musts—in order to determine the fermentation capacity of the six fermentation trials.

These results indicate a lower fermentative efficiency of

P. kudriavzevii, particularly at the beginning of fermentation, which explains the longer time required for the pure culture of this strain to reach the end point of fermentation compared to the other fermentation trials (23 vs. 16 days). However, it is noteworthy that this fermentation successfully completed, consuming all the glucose and fructose present in the must. The differential ability of the

P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651 strain to consume fructose, compared to other strains from different isolated origins, was previously demonstrated by our research group [

27]. Beyond that study, to our knowledge, only two additional studies have evaluated residual sugar levels in ciders produced with

P. kudriavzevii. Li et al. [

14] reported that

P. kudriavzevii strains produced apple ciders with high levels of residual sugars (6.2 and 13 g/L of glucose and fructose), indicating low fermentation efficiency. Similarly, Hu et al. [

13] observed residual sugar levels ranging from 5 to 25 g/L in ciders produced via mixed inoculation with

S. cerevisiae,

P. kudriavzevii, and Lactobacillus plantarum, using different

P. kudriavzevii strains. Further investigation is required to understand the potential mechanisms behind the differential fructose consumption exhibited by the

P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651 strain, given that this trait is highly valued in yeasts used for fermenting apple musts, as fructose is the predominant sugar.

In contrast, the rapid decrease in °Brix and residual glucose and fructose observed in fermentations initiated with

S. cerevisiae highlights its well-known strong adaptation to fermentable substrates and high fermentative capacity [

35].

Malic Acid Consumption

The ability of

P. kudriavzevii to consume malic acid aligns with its classification as a Krebs (+) yeast. This group includes species such as

Candida sphaerica,

C. utilis,

Hansenula anomala,

Pichia anomala,

P. kudriavzevii, and

Kluyveromyces marxianus, which are capable of metabolizing malic acid and other Krebs cycle intermediates as carbon and energy sources [

36,

37]. This capability was previously demonstrated for the

P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651 strain by our research group. In fact, this strain was selected over other

P. kudriavzevii isolates from various substrates in the Patagonian region due to its higher malic acid consumption [

28]. In that previous study, conducted in the same acidic must variety, malic acid consumption was higher than that observed in the current study, with

S. cerevisiae ÑIF8 and

P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651 consuming 4.7 g L⁻¹ and 3.7 g L⁻¹ of malic acid, respectively. This different behavior could be attributed to variations in must composition, given the variability in apple harvests from year to year. Specifically, the must used in the present study contained lower malic acid levels compared to those used in the previous work (7.6 vs 13.3 g/L). Nevertheless, the malic acid consumption levels observed in the current study remain higher than those reported in studies conducted with wine. For instance, Kim et al. [

22] found that a

P. kudriavzevii strain isolated from Korean grape wine consumed only 0.33 g L⁻¹ of malic acid when co-fermented with

S. cerevisiae at a 1:1 ratio. Similarly, del Monaco et al. [

21] reported that a

P. kudriavzevii wine strain consumed 1.14 g L⁻¹ of malic acid in synthetic wine must. One study performed in cider reported malic acid reduction during fermentations involving

P. kudriavzevii; however, it remains unclear whether the reduction was attributable to this strain or to the lactic acid bacteria inoculated alongside it in the mixed culture [

13].

Regarding

S. cerevisiae ÑIF8, it belongs to the Krebs (-) group, which can only metabolize malic acid in the presence of glucose or another assimilable carbon source. Despite this limitation, species within the

Saccharomyces genus exhibit high intraspecies variability, with strains differing in their capacities for malic acid degradation, and in some cases, even producing malic acid during alcoholic fermentation [

9,

38,

39,

40]. The

S. cerevisiae strain used in this study consumed 29% of the malic acid, equivalent to 2.2 g L⁻¹, classifying among strains capable of degrading this acid.

The results showed that the highest percentage of malic acid consumption (35.4%, equivalent to 2.6 g L⁻¹) was observed in the Seq S-P inoculation. Based on the Krebs (+) condition of P. kudriavzevii, greater malic acid consumption was expected in this strategy; this is likely due to the reduced nutrient availability encountered by P. kudriavzevii upon inoculation. Nonetheless, variations among the fermentation strategies were slight, making this factor less critical in determining the best inoculation strategy.

Viable Cell Counts and Antagonistic Activity

Cell population dynamics are critical factors influencing fermentative efficiency, competition between strains, and the contribution of each yeast's metabolism to the final beverage. Therefore, the antagonistic interactions between yeast strains and the viable cell count of each strain throughout the fermentation were evaluated in the fermentation trials.

The antagonistic activity of yeast strains with potential for use as starter cultures is considered a relevant technological attribute [

41]. Strains with antagonistic capabilities can inhibit the growth of wild

S. cerevisiae strains during natural fermentations, thereby enhancing their implantation capacity. Since non-Saccharomyces yeasts, such as

P. kudriavzevii in this study, are usually employed as mixed starter cultures in combination with

S. cerevisiae, it is essential to evaluate the potential inhibition of the non-Saccharomyces strain by

S. cerevisiae during co-fermentation. Interestingly, the

S. cerevisiae strain used in this study exhibited antagonistic activity against the sensitive reference strain (

C. glabrata NPCC106), confirming its killer phenotype. However, it did not display killer activity against

P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651. Furthermore,

P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651 strain showed no antagonistic activity but demonstrated resistance to both

S. cerevisiae ÑIF8 and the K2-type killer reference strain. This lack of sensitivity aligns with previous studies reporting the resistance of many Patagonian

P. kudriavzevii isolates to the antagonistic activity of

S. cerevisiae killer strains [

42]. Certain

P. kudriavzevii strains have been reported to inhibit the growth of bacteria and fungal pathogens that cause post-harvest diseases in fruits, such as apples and citrus [

43,

44,

45]. This antifungal capacity highlights the potential to further explore the antagonistic properties of the

P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651 strain.

Additionally,

P. kudriavzevii is well-documented for its multi-stress tolerance, including resistance to acidic conditions, ethanol, salt, sulfites, and high temperatures [

15,

27], all of which are desirable attributes for yeast strains in the cider industry.

In line with these results and previous reports, viable counts of both strains were successfully detected at the end of all the mixed fermentations. This finding aligns with the limited studies, exclusively conducted in wine, that analyzed microbiological counts of co-cultures of

P. kudriavzevii and

S. cerevisiae strains [

16,

22]. The combination of the killer activity of

S. cerevisiae ÑIF8 and the resistance of

P. kudriavzevii to this antagonistic activity is a noteworthy feature, making them a reliable pairing for mixed cultures in cider production.

Physicochemical and Aromatic Composition of Ciders

No significant differences were observed in residual glucose and fructose levels, as these sugars were completely consumed in all fermentations. Similarly, ethanol concentrations showed no significant variation among treatments. This aligns with the reported high ethanol production and tolerance of

P. kudriavzevii [

15], which enables it to accompany

S. cerevisiae strains through the completion of alcoholic fermentation. While these similarities were consistent across the fermentations, some differences emerged in the production of glycerol, certain organic acids, and aromatic compounds.

Considerations of Simultaneous Fermentations

Among the two simultaneous inoculation strategies, the Sim 1:1 approach resulted in higher glycerol levels. Glycerol is a desirable compound in cider, as it plays a primary role in enhancing the body and fullness of the final product [

44]. Regarding the organic acid profile, the Sim 1:1 cider exhibited higher concentrations of lactic acid and succinic acid than the Sim 1:10 trial. Succinic acid contributes umami notes and a rounded flavor, while lactic acid is a mild-tasting, stable acid compared to malic acid, which is associated with a harsh taste and is more prone to microbial metabolism [

24]. It is worth mentioning that among all fermentations, higher levels of lactic acid were detected in ciders where

S. cerevisiae dominated the fermentation process (S and Seq S-P), suggesting that its production is characteristic of this strain's metabolism. Lactic acid production by the

S. cerevisiae F8 strain has been previously reported [

27].

Higher alcohols are primarily produced by live yeast cells through amino acid deamination during fermentation and positively contribute to the aromatic complexity of fermented beverages when their concentration remains below 300 mg/L [

46], as observed for all the ciders obtained in this study. The major fusel alcohols identified in the ciders were isoamyl alcohol (contributing fruity and marzipan notes), isobutyl alcohol (imparting mild alcoholic aromas) and 2-phenylethanol (associated with rose and floral aromas). The comparison between the two simultaneous inoculation strategies showed that Sim 1:1 yielded higher levels of higher alcohols compared to Sim 1:10, with notable amounts of 2-phenylethanol and isoamyl alcohol. 2-phenylethanol, known for its rose and honey aromas, is considered one of the most important aromatic alcohols contributing to flavor in fermented beverages [

18,

46]. Its levels in the ciders obtained in this study—except for Sim 1:10 and Seq P-S, where it was not detected—were near the detection threshold of 10 mg/L [

47] and comparable to those produced by

Saccharomyces strains tested in apple must fermentations [

4]. However, these levels were not as high as those found in ciders produced by

S. uvarum strains [

5,

8].

Esters are a class of volatile compounds known for imparting predominantly pleasant aromas. Produced by yeasts during fermentation as secondary byproducts of sugar metabolism, these compounds are essential contributors to the desirable fruity and floral ester-like character of the beverage. Among them, acetate esters are synthesized through the catalysis of higher alcohols and acetyl-CoA by alcohol acyl-transferases, while ethyl esters are produced via an enzyme-catalyzed condensation reaction between ethanol and an acyl-CoA component [

48].

Regarding the ester profile of the ciders produced through simultaneous inoculation, slightly higher levels of isoamyl acetate (notes of green apple) and slightly lower levels of ethyl hexanoate (pineapple and pear notes) were observed in the Sim 1:1 strategy compared to Sim 1:10. Furthermore, both compounds were present at higher concentrations in Sim 1:1 when compared to all other fermentation trials. Notably, the levels of isoamyl acetate detected in all ciders from this study were substantially higher than those found in ciders produced with

S. uvarum strains that exhibited fermentative potential for cidermaking [

5].

Simultaneous inoculations demonstrated a balanced metabolic contribution from both yeasts, resulting in characteristics that could enhance cider aroma and flavor. However, the Sim 1:1 strategy stood out, and, given that the use of 10 times more P. kudriavzevii entails additional production costs, we propose Sim 1:1 as the most promising approach of the two simultaneous inoculation strategies tested for cider production.

Considerations of Sequential Fermentations

As shown in the PCA plot, sequential inoculations exhibited divergent contributions depending on the timing of yeast inoculation. The Seq S-P strategy yielded ciders with lower ethyl acetate and acetic acid levels, likely due to the earlier dominance of

S. cerevisiae. In contrast, the Seq P-S strategy reflected a stronger influence of

P. kudriavzevii, resulting in higher levels of these compounds. More specifically, the Seq P-S approach produced ciders with higher levels of acetic acid and ethyl acetate, along with lower levels of lactic acid and succinic acid. This chemical profile closely resembled that of ciders produced by pure

P. kudriavzevii inoculation (P), which suggests that the metabolism of this strain is primarily responsible for the production of the acetic acid and ethyl acetate found in P and Seq P-S ciders, compounds that contribute to the perception of sourness and roughness in cider and are undesirable at high concentrations [

46,

49]. However, it is important to note that the acetic acid concentrations in P and Seq P-S ciders (0.4 g/L) remained within the acceptable limit of 2.5 g/L set by the Argentine Food Code [

50]. Additionally, it has been reported that acetic acid becomes unpleasant at concentrations nearing its sensory threshold of 0.7–1.1 g/L, while values between 0.2 and 0.7 g/L are typically considered optimal [

51].

Ethyl acetate, the main ester in cider and wine, is formed from ethanol and acetic acid. It can impart spoilage characteristics when present at concentrations between 150 and 200 mg/L [

49,

51]. In this study, we found that Seq P-S ciders exhibited ethyl acetate levels three times higher than those of Seq S-P ciders, with concentrations surpassing the sensory threshold. However, it is worth noting that when

P. kudriavzevii is inoculated in mixed cultures Sim 1:1, Sim 1:10 and Seq S-P, the levels of ethyl acetate decrease drastically in the resulting ciders, falling below the sensory threshold. The greater capacity of species from the genera

Pichia to produce ethyl acetate compared to

S. cerevisiae wine strains has been well-documented [

34]. Subsequently, a study grouping ester production by yeast genera specifically highlighted

Hanseniaspora and

Pichia as notable producers of ethyl acetate [

52]. More recently, ethyl acetate levels similar to those observed in this study were reported in wines produced by mixed inoculation with P. kudriavzevii and a commercial

S. cerevisiae [

16,

53].

The Seq S-P strategy displayed other favorable attributes compared to Seq P-S, including higher levels of total alcohols, particularly 2-phenylethanol and isoamyl alcohol, which contribute floral and marzipan/green fruity aromas, respectively. Additionally, Seq S-P ciders exhibited higher levels of 2-phenylethyl acetate (associated with rose, honey, fruity, and flowery notes), isoamyl acetate (linked to banana and pear aromas), and ethyl hexanoate (which imparts apple, banana, violet-like aromas). These findings support the selection of the Seq S-P strategy over Seq P-S for producing ciders with enhanced aromatic complexity.

Considerations of Pure Fermentations

The grouping of pure fermentations in the PCA highlights the distinct metabolic profiles of the two yeasts. The association of P. kudriavzevii with higher levels of ethyl acetate and acetic acid is consistent with its previously mentioned capacity to produce these compounds. In contrast, S. cerevisiae displayed a stronger association with 2-phenylethanol and isoamyl acetate, emphasizing its role in contributing floral and fruity aromas to the cider. However, the total ester content (excluding ethyl acetate) in these ciders did not reach the levels observed in the mixed fermentation strategies Sim 1:1 and Seq S-P, which were selected as the most promising approaches for enhancing cider quality.

Selection of the Inoculation Strategy

Few studies have explored mixed fermentations of

S. cerevisiae and

P. kudriavzevii in wines. Zhu et al. [

20] demonstrated that a 1:1 inoculation ratio of

S. cerevisiae and

P. kudriavzevii in Cabernet Sauvignon increased the number of aromatic compounds and enhanced fruity, floral, herbaceous, and caramel-like notes compared to single-strain fermentations. Similarly, Liu et al. [

18] found that mixed fermentations in Cabernet Sauvignon improved phenolic and aromatic compounds, particularly isoamyl alcohol and ethyl esters, which contribute rose-like and fruity aromas. However, the authors reported even better results when

P. kudriavzevii was used at ten times the inoculum level of

S. cerevisiae.

A recent study demonstrated that different species of non-Saccharomyces yeast do have an important impact on the characteristics of cider and that co-inoculation of non-

Saccharomyces yeast with

S. cerevisiae for cider fermentation may be a strategy to improve the flavor of cider [

15]. However, to our knowledge, no studies have reported mixed fermentations exclusively using

S. cerevisiae and

P. kudriavzevii in cider. Two recent studies [

13,

14] employed these yeasts, but as part of a triple inoculation strategy along with

Lactobacillus plantarum. Notably, in both studies, the inoculum ratio of

S. cerevisiae to

P. kudriavzevii was 1:1, the same ratio selected in this work.

In this study, as revealed by the PCA, ciders obtained through the Sim 1:1 and Seq S-P strategies shared similar characteristics within the mixed fermentations. These ciders were associated with a high contribution of compounds such as glycerol, lactic and succinic acids, isoamyl alcohol, 2-phenylethanol, isoamyl acetate, and 2-phenylethyl acetate. Additionally, these strategies showed a higher malic acid consumption compared to pure fermentations. These features make them particularly attractive to the cider industry. Due to the practicality of co-culturing, which enables the preparation of a single inoculum and its inoculation in a single step on the same day, we propose the Sim 1:1 strategy to be tested in natural must at a pilot scale.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the effects of mixed-culture fermentation using the autochthonous S. cerevisiae ÑIF8 and P. kudriavzevii NPCC1651 strains on the production of high-quality ciders. The results highlight the complementary metabolic roles of S. cerevisiae and P. kudriavzevii in enhancing cider quality and provide valuable insights for optimizing fermentation strategies in cidermaking.

In all fermentation trials, both yeasts successfully completed the process, significantly contributing to the chemical and sensory characteristics of the ciders. The Sim 1:1 and Seq S-P strategies were identified as the most promising approaches, producing ciders with elevated levels of lactic and succinic acids, isoamyl alcohol, 2-phenylethanol, isoamyl acetate, and 2-phenylethyl acetate, and reduced levels of acetic acid and ethyl acetate. These strategies also consumed more malic acid than pure fermentations. The reduction in malic acid decreases the need for added sugar during the final adjustment stage, resulting in a healthier beverage. Given the practicality of co-culturing, which enables the preparation and inoculation of a single inoculum in one step, we propose the Sim 1:1 strategy as the preferred approach to be tested in natural must at a pilot scale for the production of ciders with low acidity and controlled, distinctive quality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Maria Mazzucco, María Rodríguez and Christian Lopes; Formal analysis, Maria Mazzucco and Milena Jovanovich; Funding acquisition, Maria Mazzucco, María Rodríguez and Christian Lopes; Investigation, Maria Mazzucco and Milena Jovanovich; Project administration, Maria Mazzucco and Christian Lopes; Resources, Juan Oteiza; Supervision, María Rodríguez and Christian Lopes; Validation, Maria Mazzucco; Visualization, Maria Mazzucco and Milena Jovanovich; Writing – original draft, Maria Mazzucco; Writing – review & editing, María Rodríguez and Christian Lopes.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Agency for the Promotion of Research, Technological Development and Innovation (Argentina) (PICT-2021-GRF-T2-00417 and PICT Start-up 2019-0034) and the National University of Comahue (Argentina) (PI04-L012 and PI04-143).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ing. Agr. Leonardo Lustig (Agro Roca S.A.) for kindly providing the apples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- AICV Cider Trends. 2022. Available online: https://aicv.org/en/publications (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- Argentine Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries. 2022. Cider value chain report in Argentina. Available online: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/cadenasagroalimentarias-febrero2020.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- Argentine Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries. 2024. Variedades no tradicionales de manzana para la elaboración de sidra. Available online: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/variedades-no-tradicionales-de-manzana-para-la-elaboracion-de-sidra (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- González Flores, M.; Rodríguez, M.E.; Oteiza, J.M.; Barbagelata, R.J.; Lopes, C.A. Physiological characterization of Saccharomyces uvarum and Saccharomyces eubayanus from Patagonia and their potential for cidermaking. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 249, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González Flores, M.; Rodríguez, M.E.; Origone, A.C.; Oteiza, J.M.; Querol, A.; Lopes, C.A. Saccharomyces uvarum isolated from Patagonian ciders shows excellent fermentative performance for low temperature cidermaking. Food Res. Int. 2019, 126, 108656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Daccache, M.; Koubaa, M.; Maroun, R.G.; Salameh, D.; Louka, N.; Vorobiev, E. Impact of the physicochemical composition and microbial diversity in apple juice fermentation process: A review. Molecules 2020, 25, 3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, P.T.; Hu, C.Y.; Tian, D.; Deng, H.; Meng, Y.H. Screening low-methanol and high-aroma produced yeasts for cider fermentation by transcriptive characterization. Fermentation 2023, 9(4), 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzini, M.; Simonato, B.; Slaghenaufi, D.; Ugliano, M.; Zapparoli, G. Assessment of yeasts for apple juice fermentation and production of cider volatile compounds. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 99, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pando Bedriñana, R.; Picinelli Lobo, A.; Rodríguez Madrera, R.; Suárez Valles, B. Characteristics of Ice Juices and Ciders made by cryo-extraction with different cider apple varieties and yeast strains. Food Chem. 2019, 292, 125831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Yue, T. Characterization and screening of non-Saccharomyces yeasts used to produce fragrant cider. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 107, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zou, S.; Dong, L.; Lin, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ji, C.; Liang, H. Chemical Composition and Flavor Characteristics of Cider Fermented with Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Non-Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Foods 2023, 12, 3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ju, H.; Niu, C.; Song, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Yue, T. Assessment of chemical composition and sensorial properties of ciders fermented with different non-Saccharomyces yeasts in pure and mixed fermentations. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 318, 108471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Chen, X.; Lin, R.; Xu, T.; Xiong, D.; Li, L.; Zhao, Z. Quality Improvement in Apple Ciders during Simultaneous Co-Fermentation through Triple Mixed-Cultures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia kudriavzevii, and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. Foods 2023, 12, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Jin, J.; Lim, J.; Lee, J.; Piao, M.; Mok, I.K.; Kim, D. Brewing of glucuronic acid-enriched apple cider with enhanced antioxidant activities through the co-fermentation of yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Pichia kudriavzevii) and bacteria (Lactobacillus plantarum). Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 30, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Y.; Li, M.; Jin, J.; Dong, X.; Xu, K.; Jin, L.; Qiao, Y.; Ji, H. Advances in the Application of the Non-Conventional Yeast Pichia kudriavzevii in Food and Biotechnology Industries. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.-R.; Xu, M.; Zheng, J.; Liu, Y.-J.; Sun, C.-H.; Wang, H.; Guo, X.-W.; Xiao, D.-G.; Wu, X.-L.; Chen, Y.-F. Application Potential of Baijiu Non-Saccharomyces Yeast in Winemaking Through Sequential Fermentation With Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 902597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzini, M.; Simonato, B.; Zapparoli, G. Yeast species diversity in apple juice for cider production evidenced by culture-based method. Folia Microbiol. 2018, 63, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Ji, R.; Aimaier, A.; Sun, J.; Pu, X.; Shi, X.; Cheng, W.; Wang, B. Adjustment of impact phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity and aroma profile in Cabernet Sauvignon wine by mixed fermentation of Pichia kudriavzevii and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Food Chem. X 2023, 18, 100685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhuo, X.; Hu, L.; Zhang, X. Effects of Crude β-Glucosidases from Issatchenkia terricola, Pichia kudriavzevii, and Metschnikowia pulcherrima on the Flavor Complexity and Characteristics of Wines. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.-X.; Wang, G.-Q.; Aihaiti, A. Combined Indigenous Yeast Strains Produced Local Wine from Over Ripe Cabernet Sauvignon Grape in Xinjiang. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 36, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Monaco, S.M.; Barda, N.B.; Rubio, N.C.; Caballero, A.C. Selection and characterization of a Patagonian Pichia kudriavzevii for wine deacidification. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 117, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-H.; Hong, Y.-A.; Park, H.-D. Co-fermentation of grape must by Issatchenkia orientalis and Saccharomyces cerevisiae reduces the malic acid content in wine. Biotechnol. Lett. 2008, 30, 1633–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.-H.; Rhee, C.; Park, H.-D. Degradation of malic acid by Issatchenkia orientalis KMBL 5774, an acidophilic yeast strain isolated from Korean grape wine pomace. J. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, J.; Baran, Y.; Navascués, E.; Santos, A.; Calderón, F.; Marquina, D.; Rauhut, D.; Benito, S. Biological management of acidity in wine industry: A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 375, 109726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribereau-Gayon, P.; Dubourdieu, D.; Doneche, B.; Lonvaud, A. Tratado de Enología: microbiología del vino vinificaciones, 2nd ed.; Hemisferio Sur: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2003; pp. 154-196.

- Fu, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. The Application of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts for Cider Fermentation and Their Impact on the Aroma and Quality of Cider. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucco, M.B.; Rodríguez, M.E.; Caballero, A.C.; Lopes, C.A. Differential consumption of malic acid and fructose in apple musts by Pichia kudriavzevii strains. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, C.A.; Sangorrín, M.P. Optimization of killer assays for yeast selection protocols. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2010, 42, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid agent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-López, F.N.; Bautista-Gallego, J.; Durán-Quintana, M.C.; Garrido-Fernández, A. Effects of ascorbic acid, sodium metabisulfite and sodium chloride on freshness retention and microbial growth during the storage of Manzanilla-Aloreña cracked table olives. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, R.J.W.; Pearson, J. Susceptibility testing: accurate and reproducible minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and non-inhibitory concentration (NIC) values. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 88, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, V.; Gil, J.V.; Piñaga, F.; Manzanares, P. Studies on acetate ester production by non-Saccharomyces wine yeast. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 70, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RStudio Version 4.4.2, R Core Team, 2022.

- Padilla, B.; Gil, J.V.; Manzanares, P. Past and Future of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts: From Spoilage Microorganisms to Biotechnological Tools for Improving Wine Aroma Complexity. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parapouli, M.; Vasileiadis, A.; Afendra, A.-S.; Hatziloukas, E. Saccharomyces cerevisiae and its industrial applications. AIMS Microbiol. 2020, 6, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saayman, M.; Viljoen-Bloom, M. The biochemistry of malic acid metabolism by wine yeasts—a review. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2006, 27, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volschenk, H.; van Vuuren, H.J.J.; Viljoen-Bloom, M. Malo-ethanolic fermentation in Saccharomyces and Schizosaccharomyces. Curr. Genet. 2003, 43, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redžepović, S.; Orlić, S.; Majdak, A.; et al. Differential malic acid degradation by selected strains of Saccharomyces during alcoholic fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 83, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.-Y.; Li, H. The use of lactic acid-producing, malic acid-producing, or malic acid-degrading yeast strains for acidity adjustment in the wine industry. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yéramian, N.; Chaya, C.; Suárez-Lepe, J.A. L-(-)-malic acid production by Saccharomyces spp. during the alcoholic fermentation of wine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, A.M.; Taggart, N.T.; Lee, M.D.; Boyer, J.M.; Rowley, P.A. The prevalence of killer yeasts and double-stranded RNAs in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2023, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Mónaco, S.; Rodríguez, M.E.; Lopes, C.A. Pichia kudriavzevii as a representative yeast of North Patagonian winemaking terroir. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 230, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleve, G.; Grieco, F.; Cozzi, G.; Logrieco, A.; Visconti, A. Isolation of epiphytic yeasts with potential for biocontrol of Aspergillus carbonarius and A. niger on grape. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 108, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottoh, I.D.; Chen, O.; Wang, W.; Yi, L.; Deng, L.; Zeng, K. Evaluation of yeast isolates from kimchi with antagonistic activity against green mold in citrus and elucidating the action mechanisms of three yeasts: P. kudriavzevii, K. marxianus, and Y. lipolytica. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 182, 111495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madbouly, A.K.; Abo Elyousr, K.A.M.; Ismail, I.M. Biocontrol of Monilinia fructigena, causal agent of brown rot of apple fruit, by using endophytic yeasts. Biocontrol 2020, 151, 104239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiegers, J.H.; Bartowsky, E.J.; Henschke, P.A.; Pretorius, I.S. Yeast and bacterial modulation of wine aroma and flavour. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2005, 11, 139–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiegers, J.H.; Pretorius, I.S. Yeast modulation of wine flavor. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 57, 131–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Li, K.; Chen, H.; Li, Z. Reviewing the Source, Physiological Characteristics, and Aroma Production Mechanisms of Aroma-Producing Yeasts. Foods 2023, 12, 3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpena, M.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Otero, P.; Nogueira, R.A.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Secondary Aroma: Influence of Wine Microorganisms in Their Aroma Profile. Foods 2020, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argentine Food Code. Argentine Ministry of Health, National Administration of Drugs, Foods, and Medical Technology (ANMAT). 2023. Chapter XIII, Article 1085 and 1087. Available online: http://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/anmat_caa_capitulo_xiii.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- Lambrechts, M.G.; Pretorius, I.S. Yeast and its Importance to Wine Aroma – A Review. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vit. 2000, 21 (Special Issue), 97–129.

- Viana, F.; Gil, J.V.; Genovés, S.; Vallés, S.; Manzanares, P. Rational selection of non-Saccharomyces wine yeasts for mixed starters based on ester formation and enological traits. Food Microbiol. 2008, 25(6), 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.-K.; Wang, J.; Chen, F.-S.; Zhang, X.-Y. Effect of Issatchenkia terricola and Pichia kudriavzevii on wine flavor and quality through simultaneous and sequential co-fermentation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 116, 108477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).