Introduction

Over the past decade, the rise of AI technologies has been meteoric, permeating various dimensions of lives with unprecedented speed and depth. The advancement in machine learning algorithms, the exponential growth of digital data, and the increasing accessibility of powerful computing resources have affected various sectors including the ever-evolving landscape of Education.

The recent emergence of generative AI in education has sparked substantial interest among scholars, fueling discussions regarding its potential use in research, pedagogical methods (Peres et al., 2023), assessment techniques (Nguyen, 2023), and ethical implications (Yusuf, 2024). This evolution presents fresh opportunities and hurdles for educators, particularly in balancing student learning outcomes with the advantages of generative AI. From the literature surveyed, there is more consensus on the benefit of Gen AI as a pedagogical tool (Lodge et al., 2023; Dai et al., 2023; Katz et al., 2023) but this technological advancement poses a notable challenge, particularly concerning the assessment and attainment of students’ learning objectives (Nguyen et al., 2023; Yusuf et al., 2024). While AI-driven assessment technologies offer the promise of continuous, formative feedback, and enhanced diagnostic insights, they also demand a reevaluation of the cognitive processes and skills deemed essential for 21st-century learners.

In this paper, we critically reexamine and reconceptualize frameworks that build off Bloom’s Taxonomy (Bloom et al., 1956). Originally proposed by Benjamin Bloom and colleagues in 1956, Bloom’s Taxonomy has served as a foundational framework for educators worldwide, guiding the design of instructional objectives and assessment strategies. However, in the age of generative AI, we argue that the traditional hierarchy of cognitive processes outlined in Bloom’s Taxonomy must be reexamined to accommodate the complexities of AI-enhanced learning environments.

Bloom’s Cognitive Taxonomy and Its Iterations

The Bloom’s Taxonomy (BT)

The Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, widely known as Bloom’s Taxonomy was introduced in 1956 in an attempt to build a taxonomy of educational objectives, providing a common standard for educators to refer to when they reference “learning”, and the kind of behaviour educators wished to document as evidence of student learning (Bloom et al., 1956). This taxonomy was based on a behaviorist paradigm of learning. While the authors recognize that learning is a phenomenon that cannot be directly observed or manipulated, educational objectives expressed in behavioral terms align with observable behaviors of individuals could be used to infer if learning has taken place. They argued that these behaviors can be seen, described, and classified through descriptive statements.

BT eventually categorized cognitive skills into six distinct levels, ranging from lower-order thinking skills to higher-order thinking skills, intending to break away from the fixation with rote learning by promoting what they saw as higher-level cognitive skills. At the base of the taxonomy are the lower-order skills of Knowledge and Comprehension, which involve recalling information and demonstrating comprehension of concepts. Moving up the hierarchy, the taxonomy encompasses the application of knowledge through Application and the analysis of information through Analysis. At the apex of the taxonomy are the higher-order skills of Synthesis, where learners combine ideas to generate new ideas or products, and Evaluation, where learners make judgments based on criteria. BT is one of the most extensively utilized frameworks that provides educators with a structured approach to designing learning objectives and assessments that target specific cognitive levels. It stands as one of the most influential and frequently referenced resources in the field of education (Houghton et al., 2004).

However, much literature is critical of the overly simplified nature of BT (Case, 2013). Bloom himself was the biggest critic concerned with his work (Wilson, 2016). For example, “Knowledge”, labeled as the lowest level in the BT, did not correspond to the other five levels which deal with cognitive skills and abilities. He was aware that “knowledge” provides context and content that is being operated on, or with, those other five cognitive skills. Bloom’s student, Anderson, and Krathwohl, who was a project member in BT’s development, picked this up and their work resulted in the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy (2001), further discussed in the following subsection.

The Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy (RBT)

In their seminal work “A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives,” Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) presented a refined version of Bloom’s Taxonomy, which expands the traditional framework to incorporate understandings of learning from the perspectives of cognitive psychology. The revised taxonomy reflects a shift from a primarily static notion to one that is more dynamic in reflecting the actions performed by the learners in attaining the intended cognitive processes. It was based on a two-dimensional framework (Urgo et al., 2019), that any statement of a learning objective should contain a verb -an associated action that reflects the attainment of the cognitive process; and an object -describing the knowledge students are expected to construct or acquire, identified as factual, conceptual, procedural or metacognitive knowledge (Anderson and Krathwohl, 2001, pp. 4–5). With a clearer framework for articulating learning objectives students are expected to meet at the end of a learning episode, the revised taxonomy helped align learning objectives, instructional activities, and assessment strategies (Urgo et al., 2019).

A consistent notion that has been carried through from its predecessor BT to RBT is strongly based on the premise that each category or dimension lies on a continuum, from a simpler to more complex cognitive processes. This is also a premise that many critics have based their arguments on, in highlighting the hierarchic structure of BT and its revised iteration which suggests that some cognitive skills are superior to others, especially with the label of “lower-order thinking skills” and “higher-order thinking skills”(Amer, 2006). The complex and messy process of learning was also downplayed by such a hierarchical structure which does not take into account the different variables influencing learning, such as interactions and motivation (Amer, 2006). Analysts detest the idea that students must progress from a lower to a higher level, suggesting a flatter, circular structure to depict that learning operates as an integrated, cyclical process, with learners frequently employing cognitive skills concurrently (WBT System, 2023).

Similarly, Darwazeh (2017) also questioned the inclusion of metacognition as a knowledge dimension in the RBT, when it is widely coined and defined as a process of thinking, and not a type of knowledge hence positioning metacognition as one of the levels, and not as a separate knowledge dimensions. She further adds that the category “creating” in RBT was perceived differently from “synthesis” in BT, and “remembering” should be further differentiated to distinguish “remembering general information” and “remembering specific information”, where the latter is subsumed by the prior based on Component Display Theory (Merril, 1983). As a result, Darwazeh (2017) proposed a nine-level taxonomy, calling it the “Revision to the [revised] Bloom’s Taxonomy”.

Bloom’s Digital Taxonomy (BDT)

The more technology-centred iteration of BT and perhaps the most relevant to this paper, is the BDT which was introduced by Churches (2007). His work was inspired by the elements and actions outlined by the RBT which were limited in describing learning activities and assessment of ICT-integrated classrooms. He further outlined possible digital activities corresponding to the levels in RBT, and suggested examples of how different assessment strategies could be incorporated in ICT classrooms (Churches, 2007). While BDT’s focus is on digital literacy skills, it merely extends BT and RBT’s foundation into a different educational environment, enabled by access to information technology and was cited in work related to the use of technology, including AI in adult education (Albakheel, 2022).

Learning and Assessment in the Age of Generative AI

The literature extensively discusses the looming threat posed by General Artificial Intelligence (Gen AI) to students’ learning agencies, particularly within the context of higher education institutions (HEIs). HEIs prioritize authentic assessments aimed at cultivating critical thinking skills and enhancing student motivation for learning (Villarroel et al., 2018). Consequently, much emphasis is placed on projects and take-home assignments, where the authenticity of student work may potentially be compromised through the use of AI-generated artifacts, leading educators and assessors into believing that students completed the work themselves.

In response to this concern, scholarly discourse has shifted towards the development of assessment designs that are resilient to AI manipulation. For instance, research by Nguyen et al. (2023) investigated the efficacy of mainstream Gen AI tools such as Chat GPT, Microsoft Bing, and Google Bard. Their study revealed that crafting tasks focused on constructing arguments based on theoretical frameworks, ensuring argument coherence, and incorporating relevant references could deter students from heavily relying on Gen AI for assignment completion. These tasks were identified as areas where Gen AI tools struggled to perform optimally.

Additionally, Nguyen et al. (2023) also highlighted Gen AI’s proficiency in handling tasks corresponding to Bloom’s Taxonomy levels of “remembering,” “understanding,” and “evaluating.” This proficiency often leads to the displacement of student efforts in memorization, factual processing, and data analysis, as Gen AI substitutes these tasks with insightful interpretations- a finding aligned with other research done with a similar aim (Chiu et al., 2023; Cooper, 2023; Halaweh, 2023).

However, it is essential to recognize that Gen AI’s responses may improve over time as more data becomes available and prompts are better engineered. Given our current understanding of large language models (LLMs), it is predicted that these factors may not pose significant limitations for future versions of Gen AI.

Discussion

The above sections have discussed how the evolution of BT occurred in response to changing learning environments from the mid-twentieth century to the second decade of the twenty-first century. For instance, the transition from BT to RBT was prompted by developments in cognitive psychology, putting the focus in RBT on cognitive processes, captured in the active verbs. Thus, for instance, the category of “knowledge” in BT was represented by verbs like “remembering” in RBT. Later, this taxonomy was adapted into BDT to take into account the influence of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) on learning during the 1900s.

In what follows we make the case for the necessity of reimagining BT in an era where the utilization of Gen AI is pervasive in education. As the influence of Gen AI in learning is still ‘a work-in-progress’ , we articulate the broad parameters of what a reimagined BT will entail.

Essentially, we build upon existing critiques regarding the static nature of cognitive levels, proposing a progression from rudimentary cognitive tasks, such as basic recall, to more intricate cognitive processes, like creative ideation. While we share Drawazeh’s (2017) observation that traditional cognitive levels were overly generalized, leading to the refinement of “Remembering” with subcategories of “Remembering of detailed information” and “Remembering of general information,” we contend that the landscape of “remembering” has evolved in the era of Gen AI. In this context, we identify a new cognitive level situated below the conventional “Remembering” phase, which we term “Ventriloquising”. At this level, learners engage in a process common in puppetry, where the human “voice’ is projected onto the puppet by the puppet master. The puppet itself only “appears” to speak merely by ventriloquising the external voice of a third party, namely that of the puppet master. Thus, in the context of Gen AI-supported ’remembering,’ the Gen AI tool, as a large language model, ’remembers’ by retrieving and providing information from its dataset. The human agent then merely replicates this ’memory’ onto the task or assignment. While some may argue that this approach does not constitute genuine learning due to its reliance on copy-pasting, we posit a similar critique for “remembering” as traditionally defined by Anderson and Krathwohl, which entails the recollection of previously memorized material. This aligns with Weiss’s (1990) definition of learning as the acquisition of knowledge leading to substantial behavioral change, thereby prompting a reconsideration of what truly constitutes learning in the digital age.

In examining the verbs outlined in RBT, it becomes apparent that they may no longer adequately capture the complexity of cognitive processes in the era of Gen AI. The verbs assigned to each level of the taxonomy appear overly simplistic because they fail to accurately reflect the intricate actions necessary for task completion in a Gen AI-driven environment. For instance, traditionally, assessing a learner’s understanding of a concept involves evaluating their ability to construct meaningful interpretations of the subject matter. Thus, a question like “Explain what is photosynthesis” typically prompts learners to articulate their comprehension of the process, or what was labeled as “Understanding” in RBT. However, in today’s educational landscape, where learners utilize Gen AI tools to craft responses, the cognitive demands are considerably heightened. In this context, learners must not only generate suitable prompts but also critically analyse (“Analysing” in RBT) the output produced, make informed decisions regarding prompt revisions (“Evaluating” in RBT), and potentially validate the relevance of the information provided by cross-checking other resources available. They are also actively engaging the “Remembering” level as they recall the words used in the initial prompts in the attempt to create (“Creating”) better prompts for more suitable output. The cognitive processes involved in responding to the same question before and during the Gen AI era differ significantly, with the latter necessitating more advanced skills such as evaluation and creation. Furthermore, we argue that the cognitive skill of “remembering” is closely intertwined with “creating” and “evaluating,” challenging its placement as the lowest level in the taxonomy. This suggests that progression through the levels may not necessarily occur linearly before a learner can engage in “creating”; rather, as the example of the case of the “explain what is photosynthesis” illustrates, the processes involved may be non-linear and discursive.

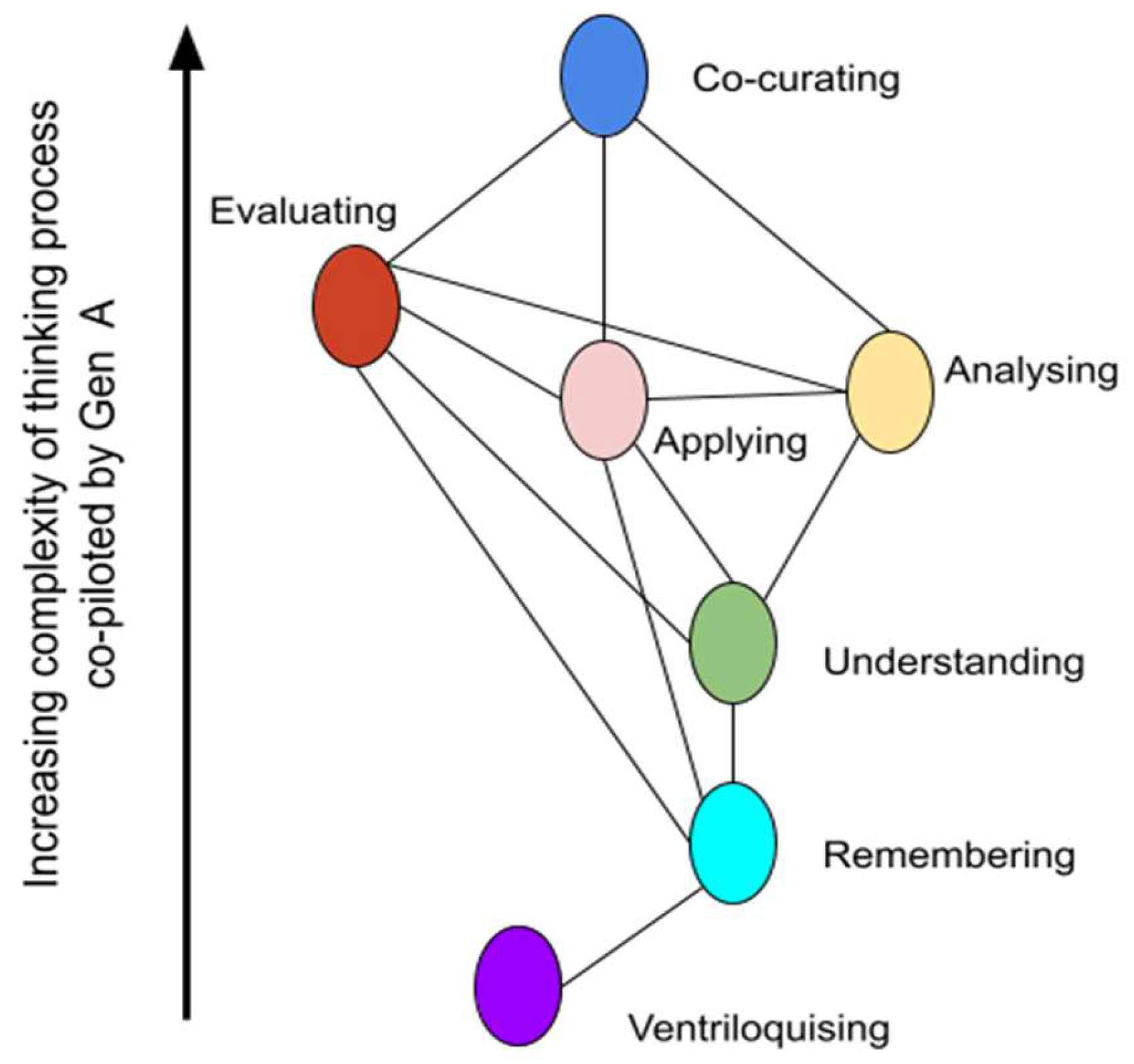

Through such complex interaction, while there are other contenders of Bloom’s Taxonomy advocating for a flatter and circular model of cognitive process, we deem that the cognitive skills should be viewed as nodes of a cognitive skill network, where the skills are interconnected rather than arranged in a linear hierarchy or circular fashion. This allows for more flexibility and complexity in representing relationships between different elements of learning.

Figure 1.

Proposed nodes of cognitive skill network.

Figure 1.

Proposed nodes of cognitive skill network.

It’s crucial to acknowledge that despite the increased complexity of cognitive processes, the resulting output presented to assessors may appear similar. This complicates the transparency of discerning the type of learning achieved through the designed task. The verbs or educational outcomes proposed within the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy framework primarily focus on the observable actions performed by the learner as evidence of cognitive engagement at a particular level. However, they fail to account for the intricate sequence of actions leading up to these terminal behaviors in the age of Gen AI. Assessment of learning in the age of AI demands a nuanced approach that integrates process measures. This entails guiding students to articulate their arguments and provide evidence of the cognitive processes that underpin the creation of their learning outcomes or artifacts. An apt analogy to elucidate this concept is the diverse array of alternative methods employed in solving dimensional analysis problems in Mathematics. Just as these methods illuminate the step-by-step thought processes behind arriving at a solution, incorporating process measures into learning assessment allows for a deeper understanding of students’ cognitive engagement and problem-solving strategies. This analytical framework not only evaluates the outcome but also captures the intricacies of students’ learning journeys, fostering a more comprehensive and insightful assessment paradigm in the age of AI. Therefore, we advocate for the implementation of Process-Driven Assessment as a pivotal strategy in evaluating and enhancing student learning experiences in an AI-driven educational landscape.

In addition, we argue for a critical reassessment of the terms “Create” (in BT) and “Synthesis” (in RBT), which have been traditionally used interchangeably within the RBT framework. We concur with Darwazeh’s assertion that synthesis requires less cognitive effort than creating. Specifically, synthesis involves assembling elements or parts according to established principles, whereas creation necessitates the production of an entirely original piece. However, in the era of Generative AI, we contend that the synthesis phase must acknowledge the co-piloting role of Gen AI. This collaboration implies that the output can be original within certain contexts. To better capture the pervasive influence of technology in the 21st century, we propose adopting a recently recognized term by established English dictionaries. The term “curate,” defined as to “Select, organize, and present (online content, merchandise, information, etc.), typically using professional or expert knowledge” (Cambridge University, n.d), aptly reflects this nuanced approach. This redefinition emphasizes the meticulous and selective process involved in synthesis, enhanced by Gen AI, which may or may not result in an “original” piece as defined by BT.

In line with our stance outlined above, we are attempting to develop an initial framework to guide educators in rethinking their teaching and assessment design. Central to this effort is the concept of “Intelligence Augmentation (IA),” as coined by Dede & McCool (Harvard Graduate School of Education, February 24, 2024). IA represents the symbiotic relationship between artificial intelligence and human intelligence, where AI excels in computational tasks such as “reckoning” and predictive analysis, while humans provide nuanced judgment informed by their lived experiences. This emerging framework not only acknowledges the transformative potential of AI in education but also underscores the critical importance of human judgment and critical thinking in effectively leveraging AI for enhanced learning outcomes. By mapping the roles of generative AI to each category in the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy and delineating the corresponding human capacities, we aim to provide educators with the tools to design teaching and assessment tasks that optimize IA. In doing so, it allows educators the space to create learning environments that fully harness the benefits of both AI and human intelligence, fostering deeper and more meaningful educational experiences.

This initial framework above expands upon the traditional categories of RBT, recognizing the evolving role of Gen AI as a partner or co-pilot in learning. With reference to

Table 1, we elaborate on each of the categories in the figure, highlighting the complementary roles of AI and the human subject.

1. Ventriloquising (Not listed in RBT)

- AI Role: Information Retrieval - AI serves as a tool for information retrieval, with no human judgment involved.

- Human Role: This category highlights the passive role of humans in simply receiving information retrieved by AI, akin to a ventriloquist’s puppet echoing pre-determined lines. The human’s role is primarily to absorb the information provided.

2. Remembering (Remembering in RBT):

- AI Role: Information Retrieval - AI aids in retrieving information, augmenting human memory.

- Human Role: Humans juxtapose information retrieved by AI with their own memory, augmenting the AI’s input. This symbiotic relationship between AI and human memory enhances the recall process.

3. Understanding or Critical Understanding (Combining Understanding, Applying, Analysing, Evaluating in RBT):

- AI Role: Describing concepts and curating detailed examples.

- Human Role: Humans augment AI’s descriptions by providing contextualization and deeper analysis. This collaboration allows for the application of knowledge in specific contexts and the critical evaluation of concepts. While AI provides descriptions and examples, humans enhance this input with their experience and critical understanding, resulting in a more nuanced comprehension. This may or may not result in a synthesized tangible outcome. However, we acknowledge that a human may not articulate or utilise all the categories listed under Critical Understanding.

4. Co-curating (Creating in RBT):

- AI Role: Providing output and options for human selection, such as curating new versions of visuals based on existing ones.

- Human Role: Humans evaluate the output generated by AI and augment it with their creativity, experience, and critical understanding to produce a co-curated piece. This category recognizes that the process of creation involves more than just generating content; it requires curation and the collaborative effort of both AI and human actors. Moreover, the concept of “curation” as undertaken by humans aligns with Constructivist paradigm, wherein cognitive schemes or schemata are constructed based on prior experiences. Through the dynamic processes of assimilation and accommodation, individuals actively integrate new information into existing cognitive frameworks, fostering learning and conceptual development (Piaget, 1971).

The absence of the traditional “Creating” category reflects the complexity of the creation process in the context of AI integration. The new category of “Co-curating” acknowledges the dynamic interplay between AI and human creativity, emphasizing the collaborative nature of content generation and curation. By delineating specific roles for AI and humans in each category, the framework provides a comprehensive understanding of how AI can enhance various cognitive processes in education.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our endeavor has not merely focused on adapting existing frameworks, but rather involves a fundamental redesign of the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy (RBT) and Bloom’s Taxonomy (BT) to incorporate the intricacies inherent in the Intelligence Augmentation (IA) paradigm. This undertaking represents a significant departure from traditional approaches, signaling a paradigm shift in the educational taxonomy which leads towards a more holistic and dynamic understanding of the interplay of cognitive processes between AI and human in the age of AI. However, it is vital to acknowledge that this work remains a dynamic and ongoing process. While we have made attempts at reconceptualizing RBT/BT, future endeavors may entail a more nuanced specification of verbs and the exploration of their underlying processes. Such endeavors are likely to require extensive empirical investigation to unravel the complexities of AI-human interaction within educational contexts.

The implications of our work extend beyond the realm of taxonomy redesign. It underscores the potential limitations of relying solely on verb-based categorisations, which may obscure the intricate and multifaceted nature of cognitive processes. Merely assessing the output or product of learning activities may not fully capture the depth and complexity of student engagement and learning. One possible future direction of work is to consider clusters of cognitive processes that work interactively rather than linearly. Therefore, the integration of process measures alongside outcome assessments becomes imperative. Each verb, representing an outcome action, should prompt a deeper inquiry into the processes that generated it, facilitating a more comprehensive understanding of student cognition and learning. In essence, our work advocates for a paradigm shift towards a process-oriented approach to educational taxonomy, one that acknowledges the symbiotic relationship between AI and human intelligence and recognizes the importance of understanding the underlying cognitive processes driving learning outcomes. By embracing this perspective, educators can craft teaching and assessment strategies that synergize AI with IA, fostering profound engagement, incisive critical thinking, and transformative learning experiences tailored for the digital age.

References

- Abalkheel, A. (2022). Amalgamating Bloom’s Taxonomy and Artificial Intelligence to Face the Challenges of Online EFL Learning Amid Post-COVID-19 In Saudi Arabia. International Journal of English Language and Literature Studies, 11(1), 16–30. [CrossRef]

- Amer, A. (2006). Reflections on Bloom’s revised taxonomy. Electronic Journal of Research in Education Psychology, 8(4), 214-230.

- Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman.

- Bloom, B. S.; Engelhart, M. D.; Furst, E. J.; Hill, W. H.; Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Company.

- Cambridge University. (n.d.). Curate. In Cambridge University Dictionary Press & Assessment. Retrieved from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/curate.

- Case, R. (2013). The unfortunate consequences of Bloom’s taxonomy. Social Education, 77(4),196-200.

- Chiu, T. K. F., Moorhouse, B. L., Chai, C. S., & Ismailov, M. (2023). Teacher support and student motivation to learn with artificial intelligence (AI) based chatbot. Interactive Learning Environments,1–17. [CrossRef]

- Churches, A. (2007). Bloom’s Digital Taxonomy. Retrieved from http://www.techlearning.com/news/0002/blooms-digital-taxonomy/68809.

- Cooper, G. (2023). Examining science education in ChatGPT: An exploratory study of generative artificial intelligence. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 32(3), 444–452. [CrossRef]

- Dai, W., Lin, J., Jin, H., Li, T., Tsai, Y.-S., Gašević, D., & Chen, G. (2023). Can large language models provide feedback to students? A case study on ChatGPT. In M. Chang, N.-S, Chen, R. Kuo, G. Rudolph, D. G.Sampson, & A. Tlili (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (pp. 323–325). [CrossRef]

- Darwazeh, A. N. (2017). A New Revision of the [Revised] Bloom’s Taxonomy. Distance Learning, 14(3), p. 13-28.

- Halaweh, M. (2023). ChatGPT in education: Strategies for responsible implementation. Contemporary Educational Technology, 15(2). [CrossRef]

- Harvard Graduate School of Education. (2024, February 24). AI won’t take your job if you know about IA [Harvard University]. Retrieved from https://www.gse.harvard.edu/ideas/news/24/02/ai-wont-take-your-job-if-you-know-about-ia.

- Houghton, J., Steele, C., & Henty, M. (2004). Research practices and scholarly communication in the digital environment. Learned Publishing, 17(3), 231-249. [CrossRef]

- Katz, A., Wei, S., Nanda, G., Brinton, C., & Ohland, M. (2023). Exploring the efficacy of ChatGPT in analyzing student teamwork feedback with an existing taxonomy. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Lodge, J. M., Thompson, K., & Corrin, L. (2023). Mapping out a research agenda for generative artificial intelligence in tertiary education. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 39(1), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Merrill, M. D. (1983). The component display theory. In C. M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional design theories and models: An overview of their current status. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Nguyen, TB, Diem Thi Hong Vo, Minh Nguyen Nhat, Thi Thu Tra Pham, Hieu Thai Trung, and Son Ha Xuan. (2023). “Race with the Machines: Assessing the Capability of Generative AI in Solving Authentic Assessments.” Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 39(5): 59–81. [CrossRef]

- Peres, R., Schreier, M., Schweidel, D., & Sorescu, A. (2023). Editorial: On ChatGPT and beyond: How generative artificial intelligence may affect research, teaching, and practice. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 40(2), 269–275. [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J. (1971). The theory of stages in cognitive development. In D. R. Green, M. P. Ford, & G. B. Flamer, Measurement and Piaget. McGraw-Hill.

- Urgo, K., Arguello, J., & Capra, R. (2019). Anderson and Krathwohl’s Two-Dimensional Taxonomy Applied to Task Creation and Learning Assessment. Proceedings of the 2019 ACM SIGIR International Conference on Theory of Information Retrieval, 117–124. [CrossRef]

- Villarroel, V., Bloxham, S., Bruna, D., Bruna, C., & Herrera-Seda, C. (2018). Authentic assessment: Creating a blueprint for course design. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 43(5), 840– 854. [CrossRef]

- WBT Systems. (2023, September 12). Learning science made easy: The original, revised & rebuked Bloom’s Taxonomy. Retrieved from https://www.wbtsystems.com/learning-hub/blogs/blooms-taxonomy.

- Weiss, H. M. (1990). Learning theory and industrial and organizational psychology. In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (2nd ed., pp. 171–221). Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Yusuf, A., Pervin, N., & Roman-Gonzales, M. (2024). Generative AI and the future of higher education: A threat to academic integrity or reformation? Evidence from multicultural perspectives. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21(1), 1-29. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Roles of Humans and Generative AI in Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy and Proposed Categories.

Table 1.

Roles of Humans and Generative AI in Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy and Proposed Categories.

| RBT categories |

Proposed Categories |

Role of AI |

Role of Human |

| None |

Ventriloquising |

Information Retrieval |

No human judgment is involved |

| Remembering |

Remembering |

Information Retrieval |

Juxtapose information retrieved from AI with human memory; AI augments human memory |

| Understanding |

Understanding |

Critical Understanding |

AI describes a concept and curating possible examples with more details |

Human augments AI input to describe concepts and contextualise different examples. These prompts will allow human AI partnership to apply knowledge in specific context, analyse different components of their understanding and to make appropriate critical evaluation. This may or may not result in a synthesized tangible outcome.

However, we acknowledge that a human may not articulate or utilise all the levels described above. |

| Applying |

|

| Analysing |

| Evaluating |

| Creating |

Co-curating |

AI providing output and options for human to choose from. For example, DALL.E curating new versions of visuals based on existing visuals. |

Human will evaluate the output given by AI, augmenting it with his or her experience, creativity and critical understanding, to produce a “co-curated” piece. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).