Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This research project involves a comprehensive approach to utilizing artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), & deep learning (DL), for detecting climate change related natural disasters such as flooding/desertification from aerial imagery. By compiling images of numerous datasets from an open-access data site, this work offers an extensive novel dataset, the Climate Change Dataset. This dataset was utilized to train DL models including transfer learning models for the detection of climate related natural disasters. Four ML models trained on the Climate Change Dataset were compared including: a convolutional neural network (CNN), DenseNet201, VGG16, and ResNet50. Our DenseNet201 model was chosen for optimization leading to improved performance. The 4 ML models all performed well with DenseNet201 Optimized and ResNet50 yielding the highest accuracies of 99.37% and 99.21% respectively. By advancing our scientific knowledge in climate change impacts, desertification & flood detection, this research project has demonstrated the potential of AI to proactively address environmental challenges. Our study is intended for the use of AI for Climate Change and Environmental Sustainability.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Compiling the Climate Change Dataset

2.2. Preprocessing and Model Initiation

2.3. VGG16 Network Model

2.4. DenseNet201 Network Model

2.4.1. Data Augmentation Layer

2.4.2. Rescaling Layer

2.4.3. Global Average Pooling Layer

2.4.4. Dropout Layer

2.4.5. Fully Connected Layer and Classifier

2.5. ResNet50 Network Model

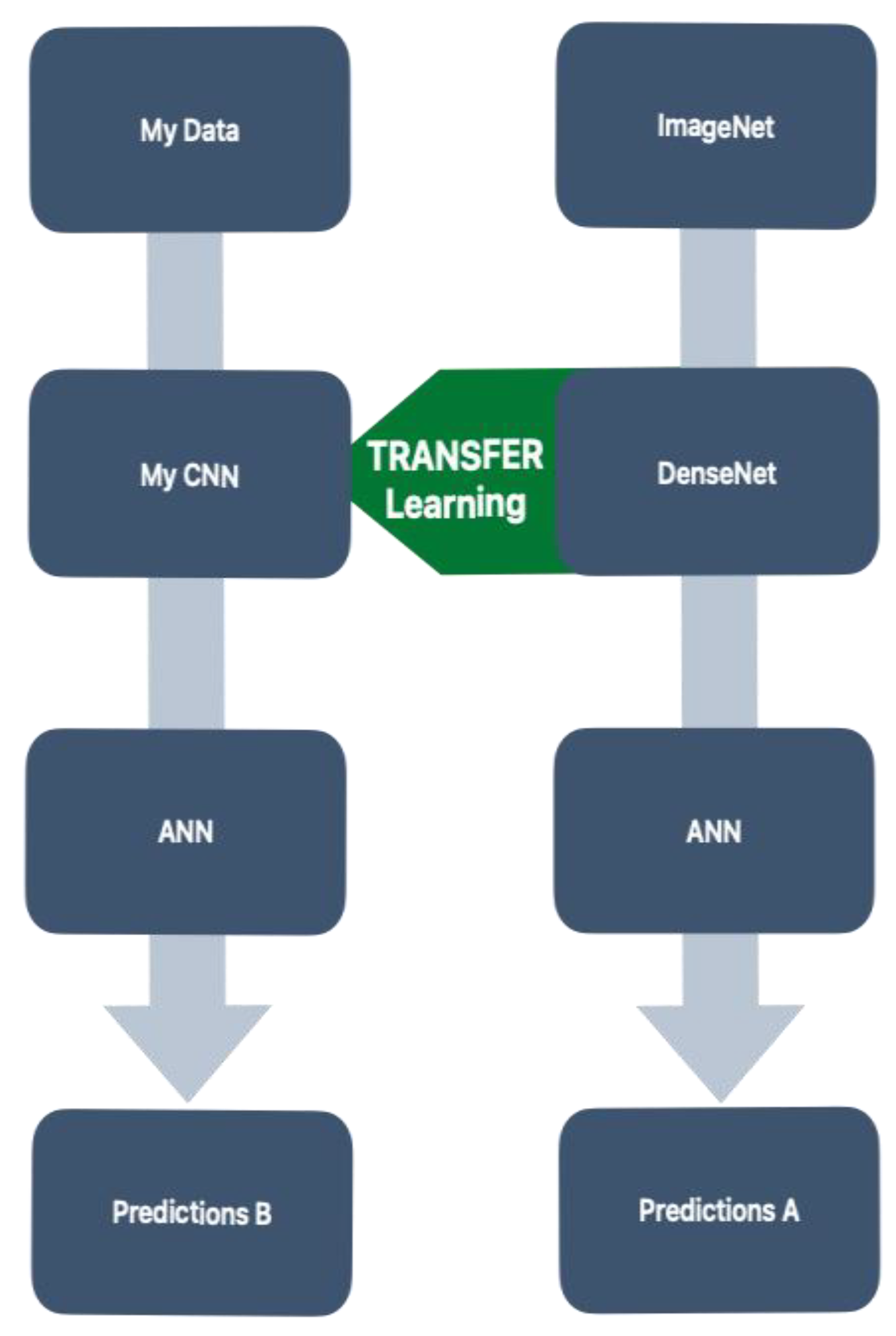

2.6. Transfer Learning Framework

2.7. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) Model

2.7.1. CNN Layers

- 1 rescaling layer

- 1 data augmentation layer

- 3 convolutional layers

- 3 pooling layers

- 1 drop-out layer

- 3 fully connected (FC) layers

2.7.2. Pooling Layers

2.8. Experimental Set-Up

- Collaborate online with code/feedback

- Accelerate our ML workload with Google GPUs/TPUs

- Utilize Google’s cloud computing resources.

2.9. Evaluation Metrics

3. Results

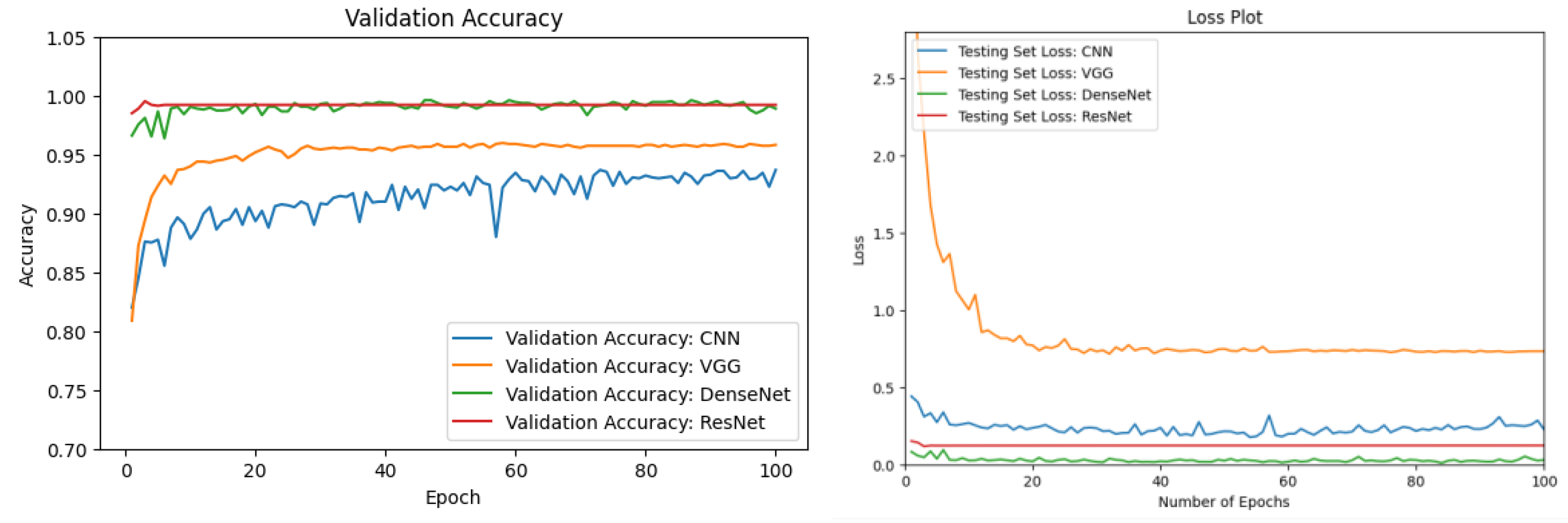

3.1. Individual Model Performance

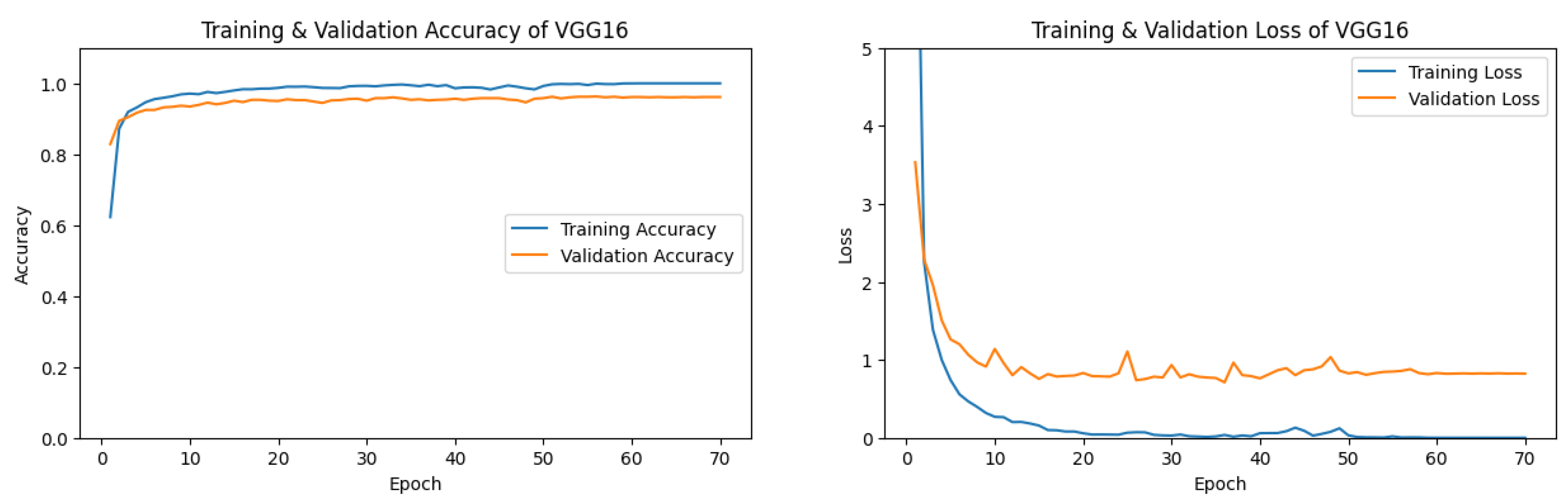

3.1.1. VGG16 Performance

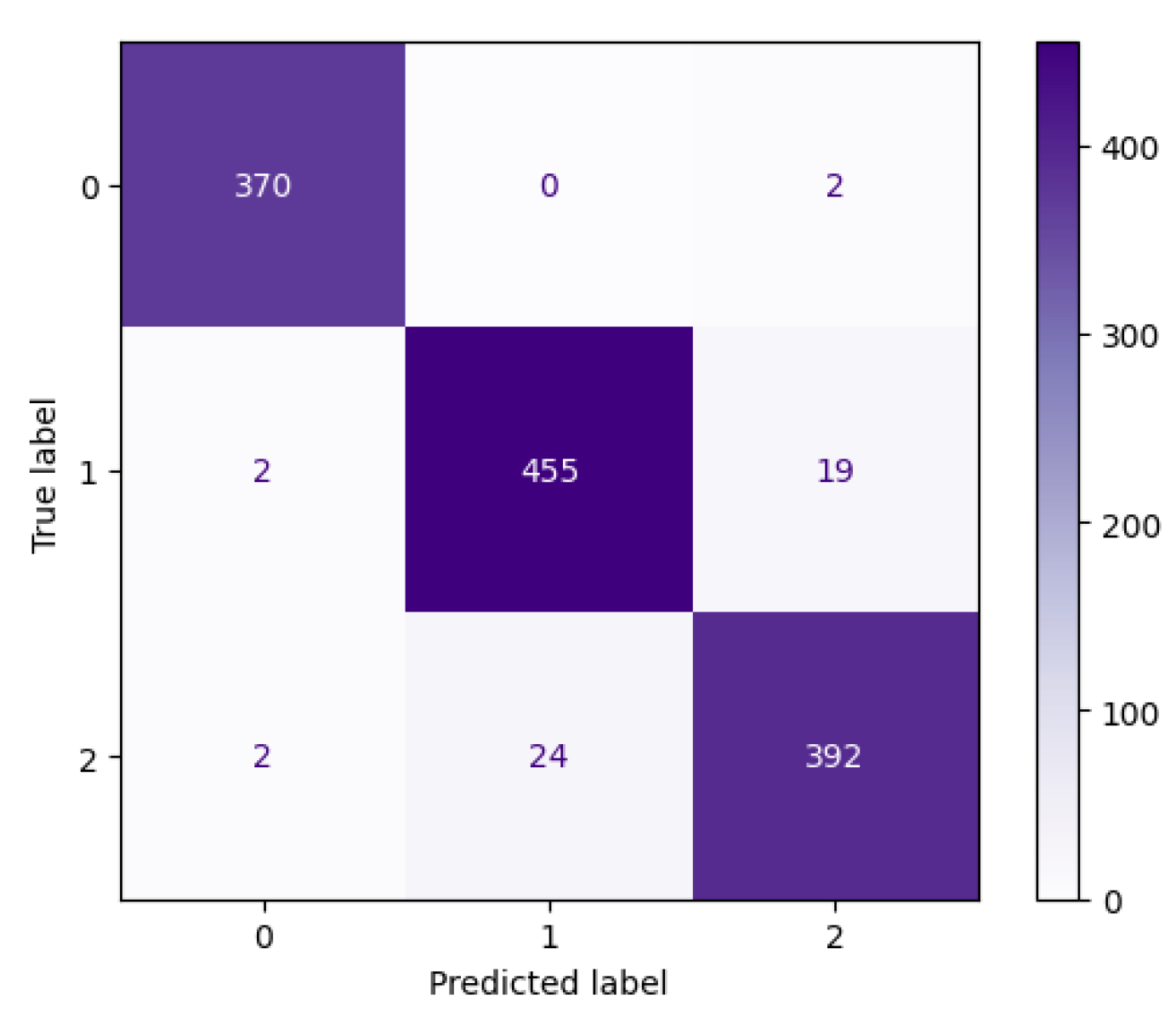

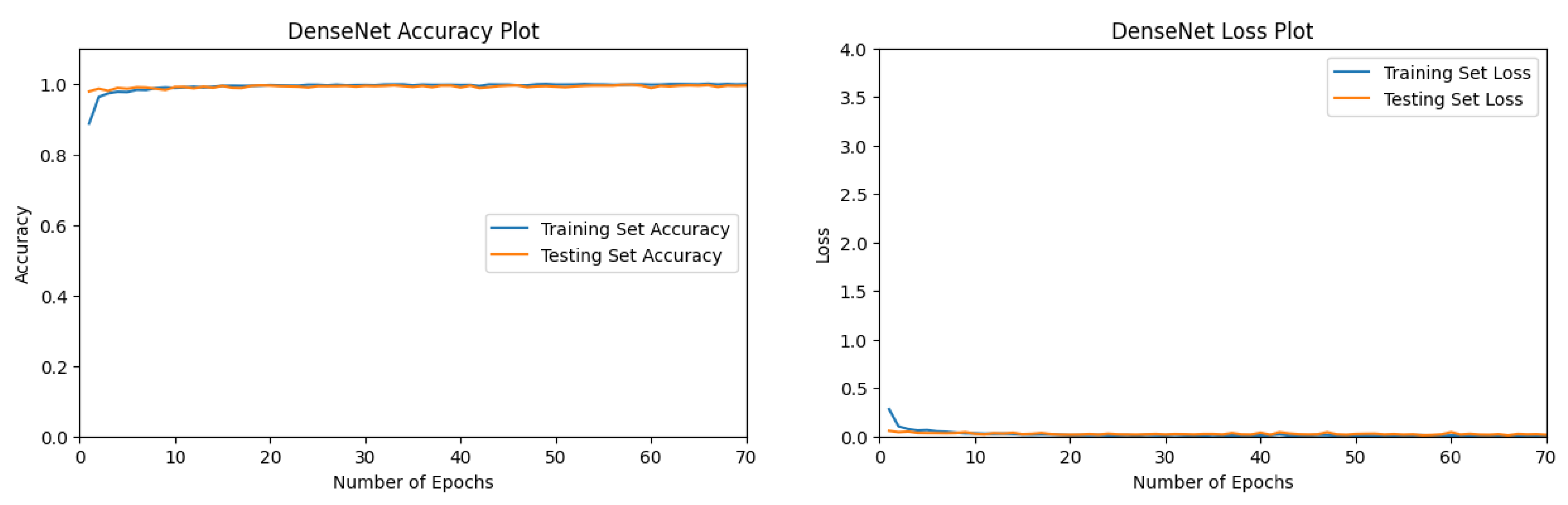

3.1.2. DenseNet Performance

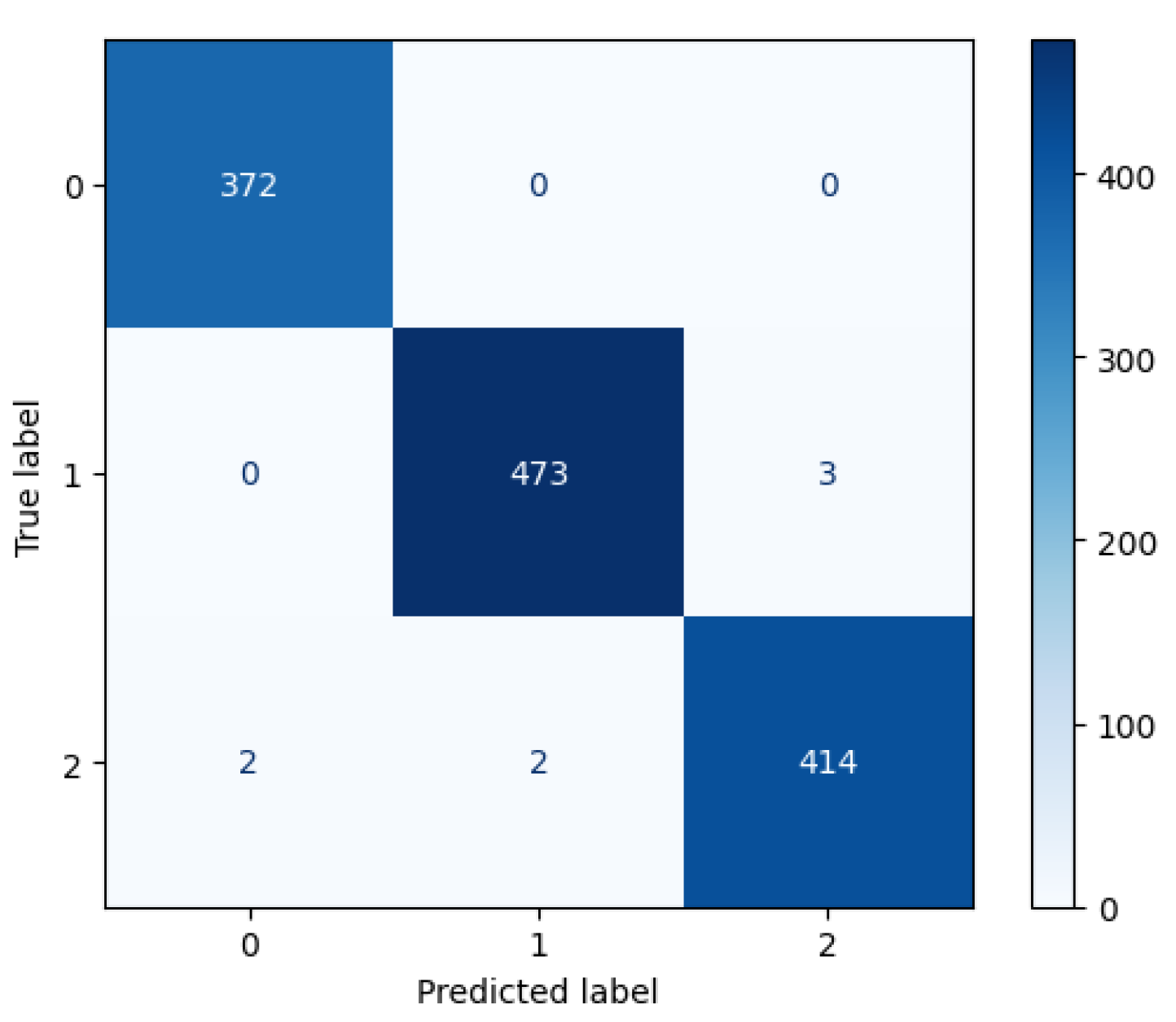

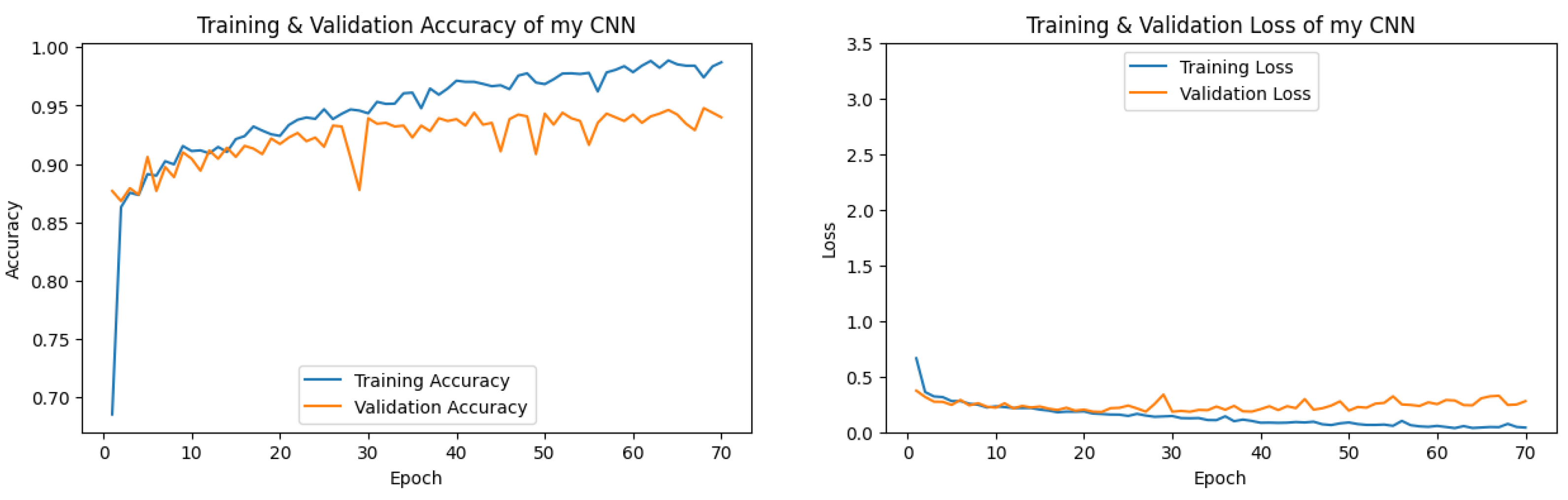

3.1.3. CNN Performance

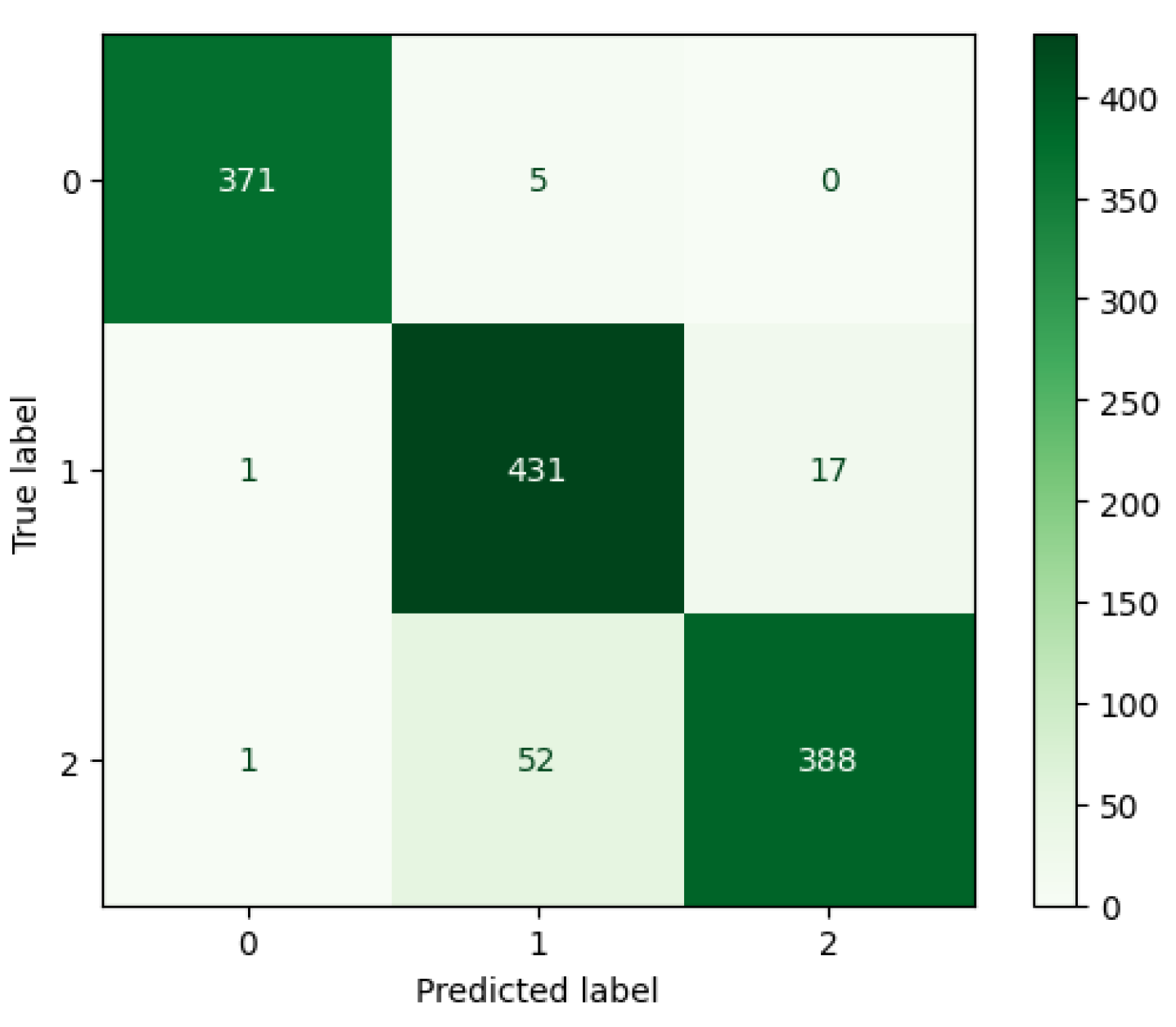

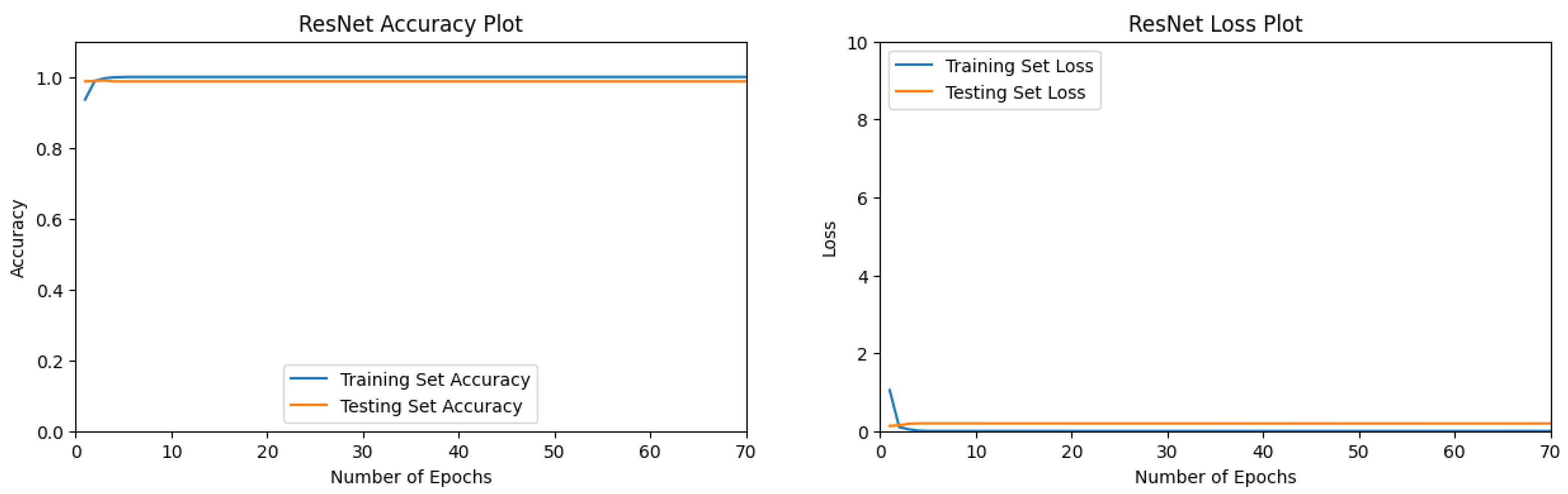

3.1.4. ResNet Performance

3.2. ML Model Comparison

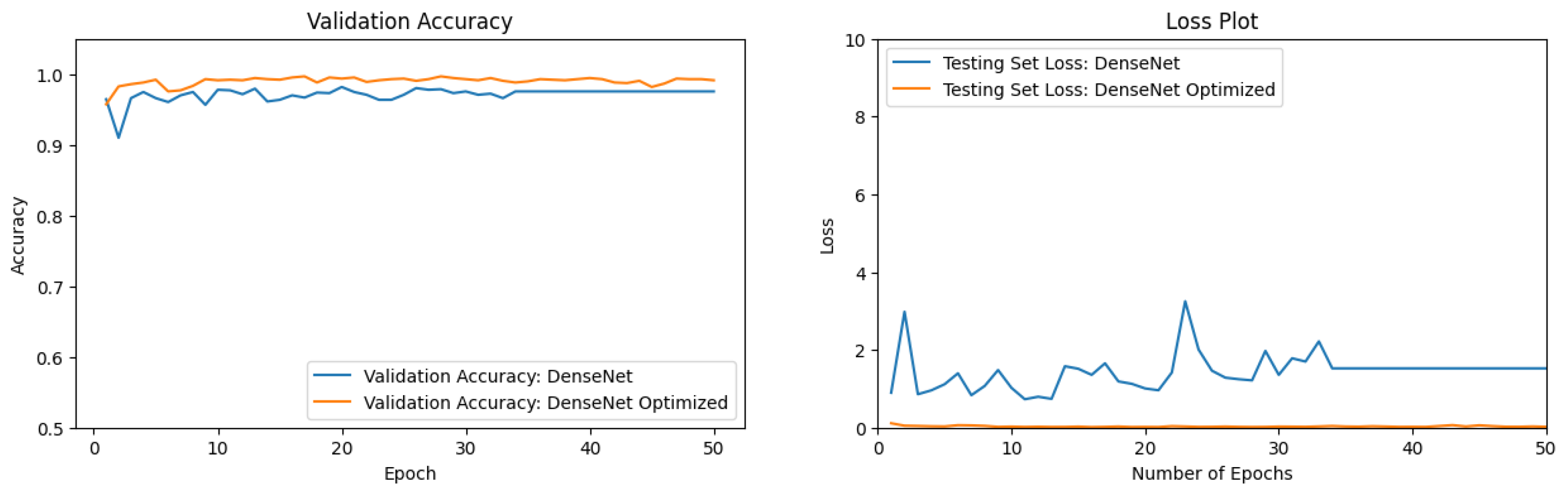

3.3. Optimization of DenseNet

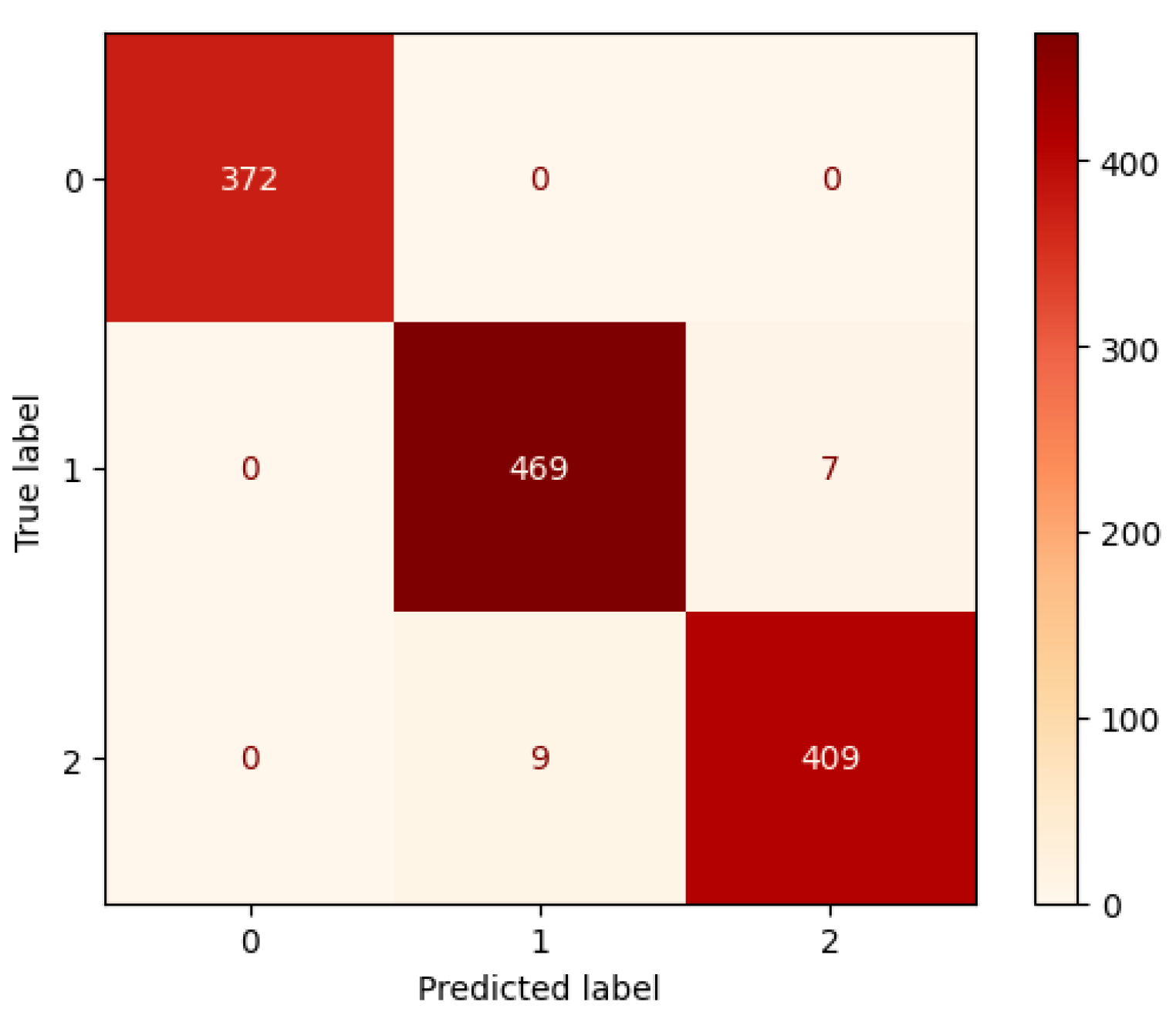

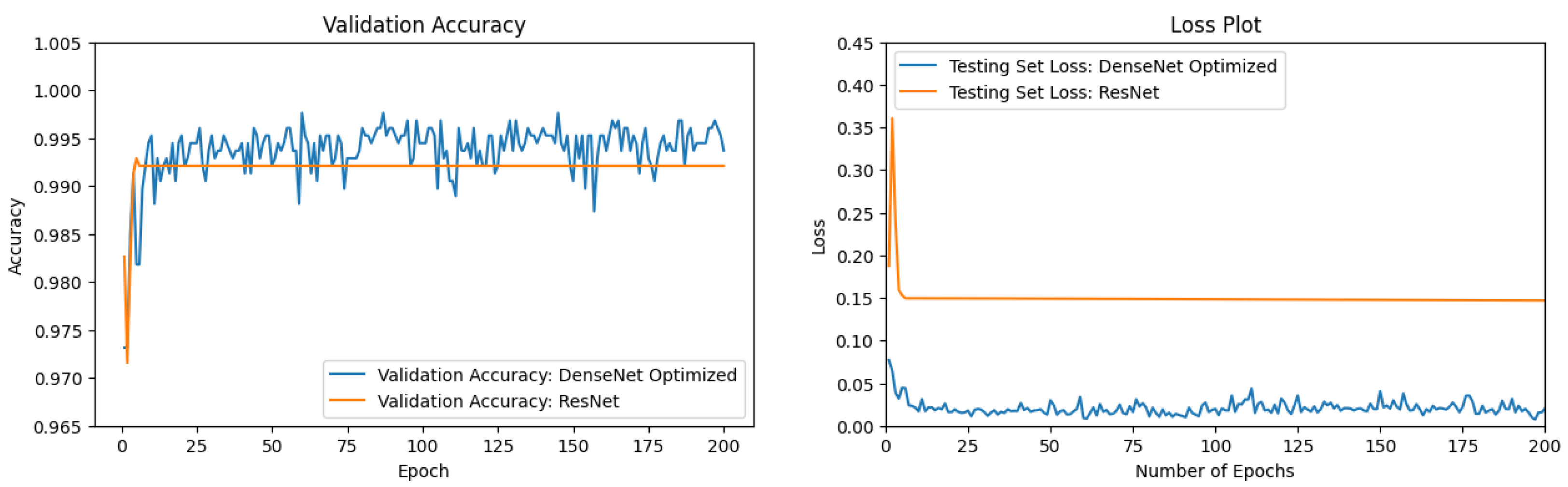

3.4. ResNet vs. DenseNet Optimized

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- B. Clarke, F. Otto, R. Stuart-Smith and L. Harrington, "Extreme weather impacts of climate change: an attribution perspective," Environmental Research: Climate, pp. 1-26. doi:10.1088/2752-5295/ac6e7d, 2022.

- Intergovernmental_Panel_On_Climate_Change(IPCC), "Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change," Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2023.

- C. Raymond, T. Matthews and R. Horton, "The emergence of heat and humidity too severe for human tolerance," Science Advances, vol. 6, no. 19, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw1838, 2020.

- EMDAT, "The emergency events database," (Univ of Louvain - CRED), 2019.

- C. Cho, R. Li, S.-Y. Wang, J. -H. Yoon and R. R. Gillies, "Anthropogenic Footprint of Climate Change in the June 2013 Northern India Flood," Climate Dynamics, pp. 797-805. doi: 10.1007/s00382-015-2613-2, 2015.

- P. Pall, C. Patricola, M. Wehner, D. Stone, C. Paciorek and W. Collins, "Diagnosing conditional anthropogenic contributions to heavy Colorado rainfall in September 2013," Weather and Climate Extremes, vol. 17, pp. 1-6. doi:10.1016/j.wace.2017.03.004, 2017.

- K. van der Wiel, S. B. Kapnick, G. J. van Oldenborgh, K. Whan, S. Philip, G. Vecchi, R. K. Singh, J. Arrighi and H. Cullen, "Rapid attribution of the August 2016 flood-inducing extreme precipitation in south Louisiana to climate change," Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 897-921. doi:10.5194/hess-21-897-2017, 2017.

- S. Philip, S. F. Kew, G. J. van Oldenborgh, E. Aalbers, R. Vautard, F. Otto, K. Haustein, F. Habets and R. Singh, "Validation of a rapid attribution of the May/June 2016 flood-inducing precipiation in France to climate change," Journal of Hydrometerorology, vol. 19, no. 11, pp. 1881-1898. doi: 10.1175/JHM-D-18-0074.1, 2018.

- B. Teufel, L. Sushama, O. Huziy, G. T. Diro, D. Jeong, K. Winger, C. Garnaud, R. de Elia, F. W. Zwiers, H. D. Matthews and V.-T.-V. Nguyen, "Investigation of the mechanisms leading to the 2017 Montreal flood," Climate Dynamics, pp. 4193-4206. doi: 10.1007/s00382-018-4375-0, 2019.

- J. Huang, G. Zhang, Y. Zhang, X. Guan, Y. Wei and R. Guo, "Global desertification vulnerability to climate change and human activities," Land Degrad Dev., pp. 1380-1391. doi: 10.1002/ldr.3556, 2020.

- UNCCD, "United Nations convention to combat desertification in countries experiencing serous drought and/or desertification, paticularly in Africa," Paris, 1994.

- S. Nicholson, C. Tucker and M. Ba, "Desertification, Drought, and Surface Vegetation: An Example from the West African Sahel," Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, vol. 79, pp. 815-829. doi: 10.1175/1520-0477(1998)079<0815:DDASVA>2.0.CO;2, 1998.

- M. Sivakumar, "Interactions between climate and desertification," Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, vol. 142, no. 2-4, pp. 143-155. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2006.03.025, 2007.

- MillenniumEcosystemAssessment(MEA), "Ecosystems and human well-being: Desertification synthesis.," Washington, D.C.: World Resources Institute, 2005.

- D. Hernández, J.-C. Cano, F. Silla, C. T. Calafate and J. M. Cecilia, "AI-Enabled Autonomous Drones for Fast Climate Change Crisis Assessment," IEEE Internet of Things Journal, pp. 7286-7297. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2021.3098379, 2022.

- Alsumayt, N. El-Haggar, L. Amouri, Z. M. Alfawaer and S. S. Aljameel, "Smart Flood Detection with AI and Blockchain Integration in Saudi Arabia Using Drones," Sensors, pp. 1-30. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/s23115148, 2023.

- N. S. Intizhami, E. Q. Nuranti and N. I. Bahar, "Dataset for flood area recognition with semantic segmentation," Data in Brief, vol. 51, pp. 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2023.109768, 2023.

- F. S. Alrayes, S. S. Alotaibi, K. A. Alissa, M. Maashi, A. Alhogail, N. Alotaibi, H. Mohsen and A. Motwakel, "Artificial Intelligence-Based Secure Communication and Classification for Drone-Enabled Emergency Monitoring Systems," Drones, vol. 6, no. 9, pp. 1-18. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones6090222, 2022.

- R. Karanjit, R. Pally and S. Samadi, "FloodIMG: Flood image DataBase system," Data in Brief, vol. 48, pp. 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2023.109164, 2023.

- D. Hamlington, A. Tripathi, D. R. Rounce, M. Weathers, K. H. Adams, C. Blackwood, J. Carter, R. C. Collini, L. Engeman, M. Haasnoot and R. E. Kopp, "Satellite monitoring for coastal dynamic adaptation policy pathways," Climate Risk Management, vol. 42, pp. 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2023.100555, 2023.

- J. P. Dash, G. D. Pearse and M. S. Watt, "UAV Multispectral Imagery Can Complement Satellite Data for Monitoring Forest Health," Remote Sens., pp. 1-22. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10081216, 2018.

- K. Dilmurat, V. Sagan and S. Moose, "AI-DRIVEN MAIZE YIELD FORECASTING USING UNMANNED AERIAL VEHICLE-BASED HYPERSPECTRAL AND LIDAR DATA FUSION," ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, pp. 193-198. https://doi.org/10.5194/isprs-annals-V-3-2022-193-2022, 2022.

- Raniga, N. Amarasingam, J. Sandino, A. Doshi, J. Barthelemy, K. Randall, S. A. Robinson, F. Gonzalez and B. Bollard, "Monitoring of Antarctica’s Fragile Vegetation Using Drone-Based Remote Sensing, Multispectral Imagery and AI," Sensors, pp. 1-29. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24041063, 2024.

- A. Santangeli, Y. Chen, E. Kluen, R. Chirumamilla, J. Tiainen and J. Loehr, "Integrating drone-borne thermal imaging with artificial intelligence to locate bird nests on agricultural land," Scientific Reports, pp. 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67898-3, 2020.

- H. R. G. Malamiri, F. A. Aliabad, S. Shojaei, M. Morad and S. S. Band, "A study on the use of UAV images to improve the separation accuracy of agricultural land areas," Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, vol. 184, pp. 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2021.106079, 2021.

- Alvarez-Vanhard, T. Corpetti and T. Houet, "UAV & satellite synergies for optical remote sensing applications: A literature review," Science of Remote Sensing, vol. 3, pp. 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srs.2021.100019, 2021.

- A. Marx, D. McFarlane and A. Alzahrani, "UAV data for multi-temporal Landsat analysis of historic reforestation: a case study in Costa Rica," International Journal of Remote Sensing, pp. 2331-2348. doi:10.1080/01431161.2017.1280637, 2017.

- N. Hassan, A. S. Musa Miah and J. Shin, "Residual-Based Multi-Stage Deep Learning Framework for Computer-Aided Alzheimer’s Disease Detection," Journal of Imaging, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 1-21. doi:10.3390/jimaging10060141, 2024.

- A.M. Ibrahim, M. Elbasheir, S. Badawi, A. Mohammed and A. F. M. Alalmin, "Skin Cancer Classification Using Transfer Learning by VGG16 Architecture (Case Study on Kaggle Dataset)," Journal of Intelligent Learning Systems and Applications, vol. 15, pp. 67-75. doi: 10.4236/jilsa.2023.153005, 2023.

- B. Abu Sultan and S. S. Abu-Naser, "Predictive Modeling of Breast Cancer Diagnosis Using Neural Networks:A Kaggle Dataset Analysis," International Journal of Academic Engineering Research, pp. 1-9, 2023.

- S. Bojer and J. P. Meldgaard, "Kaggle forecasting competitions: An overlooked learning opportunity," International Journal of Forecasting, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 587-603. doi:10.1016/j.ijforecast.2020.07.007, 2021.

- J. Ker, L. Wang, J. Rao and T. Lim, "Deep Learning Applications in Medical Image Analysis," IEEE Access, pp. 9375-9389. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2788044, 2018.

- R. Ghnemat, S. Alodibat and Q. A. Al-Haija, "Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) for Deep Learning Based Medical Imaging Classification," Journal of Imaging, pp. 1-31. doi:10.3390/jimaging9090177, 2023.

- Kwenda, M. Gwetu and J. V. Fonou-Dombeu, "Hybridizing Deep Neural Networks and Machine Learning Models for Aerial Satellite Forest Image Segmentation," Journal of Imaging, pp. 1-34. doi: 10.3390/jimaging10060132 PMCID: PMC11204628 , 2024.

- T. Boston, A. Van Dijk and R. Thackway, "U-Net Convolutional Neural Network for Mapping Natural Vegetation and Forest Types from Landsat Imagery in Southeastern Australia," Journal of Imaging, pp. 1-24. doi:10.3390/jimaging10060143, 2024.

- A. Kumar, A. Jaiswal, S. Garg, S. Verma and S. Kumar, "Sentiment Analysis Using Cuckoo Search for Optimized Feature Selection on Kaggle Tweets," International Journal of Information Retrieval Research , vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1-15. doi: 10.4018/IJIRR.2019010101, 2019.

- Albin Ahmed, A. Shaahid, F. Alnasser, S. Alfaddagh, S. Binagag and D. Alqahtani, "Android Ransomware Detection Using Supervised Machine Learning Techniques Based on Traffic Analysis," Sensors, pp. 1-21. doi:10.3390/s24010189, 2024.

- S. B. Taieb and R. J. Hyndman, "A gradient boosting approach to the Kaggle load forecasting competition," International Journal of Forecasting, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 382-394. doi: 10.1016/j.ijforecast.2013.07.005, 2014.

- "Kaggle," [Online]. Available: https://www.kaggle.com/. [Accessed 1 10 2024].

- RahulTP, "Louisiana flood 2016," Kaggle, [Online]. Available: www.kaggle.com/datasets/rahultp97/louisiana-flood-2016. [Accessed 1 Oct 2024].

- M. Wang, "FDL_UAV_flooded areas," Kaggle, [Online]. Available: www.kaggle.com/datasets/a1996tomousyang/fdl-uav-flooded-areas. [Accessed 1 Oct 2024].

- R. Rupak, "Cyclone, Wildfire, Flood, Earthquake Database," Kaggle, [Online]. Available: www.kaggle.com/datasets/rupakroy/cyclone-wildfire-flood-earthquake-database. [Accessed 1 Oct 2024].

- M. Reda, "Satellite Image Classification," Kaggle, [Online]. Available: www.kaggle.com/datasets/mahmoudreda55/satellite-image-classification. [Accessed 1 Oct 2024].

- G. Mystriotis, "Disasters Dataset," Kaggle, [Online]. Available: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/georgemystriotis/disasters-dataset. [Accessed 1 Oct 2024].

- A. Bhardwaj and Y. Tuteja, "Aerial Landscape Images," Kaggle, [Online]. Available: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ankit1743/skyview-an-aerial-landscape-dataset. [Accessed 1 Oct 2024].

- Y. Tuteja and A. Bhardwaj, "Aerial Images of Cities," Kaggle, [Online]. Available: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/yessicatuteja/skycity-the-city-landscape-dataset. [Accessed 1 Oct 2024].

- Demir, K. Koperski, D. Lindenbaum, G. Pang, J. Huang and S. Basu, "DeepGlobe 2018: A Challenge to Parse the Earth through Satellite Images," in 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Salt Lake City, UT, 2018.

- Simonyan and A. Zisserman, "Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition," arXiv, pp. 1-14. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1409.1556, 2015.

- X. Zan, X. Zhang, Z. Xing, W. Liu, X. Zhang, W. Su, Z. Liu, Y. Zhao and S. Li, "Automatic Detection of Maize Tassels from UAV Images by Combining Random Forest Classifier and VGG16," Remote Sensing, vol. 12, no. 18, pp. 1-17. doi : 10.3390/rs12183049, 2020.

- G. Huang, Z. Liu, L. van der Maaten and K. Q. Weinberger, "Densely Connected Convolutional Networks," arXiv, pp. 1-8. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1608.06993, 2018.

- A. Mumumi and F. Mumuni, "Data augmentation: A comprehensive survey of modern approaches," Array, vol. 16, pp. 1-27. doi : 10.1016/j.array.2022.100258, 2022.

- X. Pei, Y. h. Zhao, L. Chen, Q. Guo, Z. Duan, Y. Pan and H. Hou, "Robustness of machine learning to color, size change, normalization, and image enhancement on micrograph datasets with large sample differences," Materials & Design, vol. 232, pp. 1 - 13. doi : 10.1016/j.matdes.2023.112086, 2023.

- G. Habib and S. Qureshi, "GAPCNN with HyPar: Global Average Pooling convolutional neural network with novel NNLU activation function and HYBRID parallelism," Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience, vol. 16, pp. 1 - 18. doi : 10.3389/fncom.2022.1004988, 2022.

- S. Shabbeer Basha, S. R. Dubey, V. Pulabaigari and S. Mukherjee, "Impact of fully connected layers on performance of convolutional neural networks for image classification," Neurocomputing, vol. 378, pp. 112-119. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2019.10.008, 2020.

- He, X. Zhang, S. Ren and J. Sun, "Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition," arXiv, pp. 1 - 12. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1512.03385, 2015.

- W. Alsabhan and T. Alotaiby, "Automatic Building Extraction on Satellite Images Using Unet and ResNet50," Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, pp. 1-12. doi : 10.1155/2022/5008854, 2022.

- A. Zafar, M. Aamir, N. M. Nawi, A. Arshad, S. Riaz, A. Alruban, A. K. Dutta and S. Almotairi, "A Comparison of Pooling Methods for Convolutional Neural Networks," Applied Sciences, vol. 12, no. 17, pp. 1-21. doi : 10.3390/app12178643, 2022.

- A.G. Ajayi and J. Ashi, "Effect of varying training epochs of a Faster Region-Based Convolutional Neural Network on the Accuracy of an Automatic Weed Classification Scheme," Smart Agricultural Technology, vol. 3, pp. 1-14. doi: 10.1016/j.atech.2022.100128, 2023.

| Name of Dataset | Total Image Count | Flooded | Desert | Neither |

| Louisiana Flood 2016 [40] | 263 | 102 | 0 | 161 |

| FDL_UAV_flood areas [41] | 297 | 130 | 0 | 167 |

| Cyclone, Wildfire, Flood, Earthquake Database [42] | 613 | 613 | 0 | 0 |

| Satellite Image Classification Disaster Dataset [43] |

1131 | 0 | 1131 | 0 |

| Disasters Dataset [44] | 1630 | 1493 | 0 | 137 |

| Aerial Landscape Images [45] | 800 | 0 | 800 | 0 |

| Aerial Images of Cities [46] | 600 | 0 | 0 | 600 |

| Forest Aerial Images for Segmentation [47] | 1000 | 0 | 0 | 1000 |

| Totals | 6334 | 2338 | 1931 | 2065 |

| Category | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

| Desert | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Flooded | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

| Neither | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Category | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

| Desert | 0.99 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Flooded | 1.0 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Neither | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Category | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

| Desert | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Flooded | 0.88 | 0.96 | 0.92 |

| Neither | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.92 |

| Category | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

| Desert | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Flooded | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.98 |

| Neither | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| ML Model | Validation Accuracy |

| CNN | 0.9368 |

| VGG16 [48] | 0.9581 |

| DenseNet201 [50] Optimized | 0.9889 |

| ResNet50 [55] | 0.9921 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).