Submitted:

03 January 2025

Posted:

04 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Chemical Diversity of M. polymorpha

2.1. Terpenoids

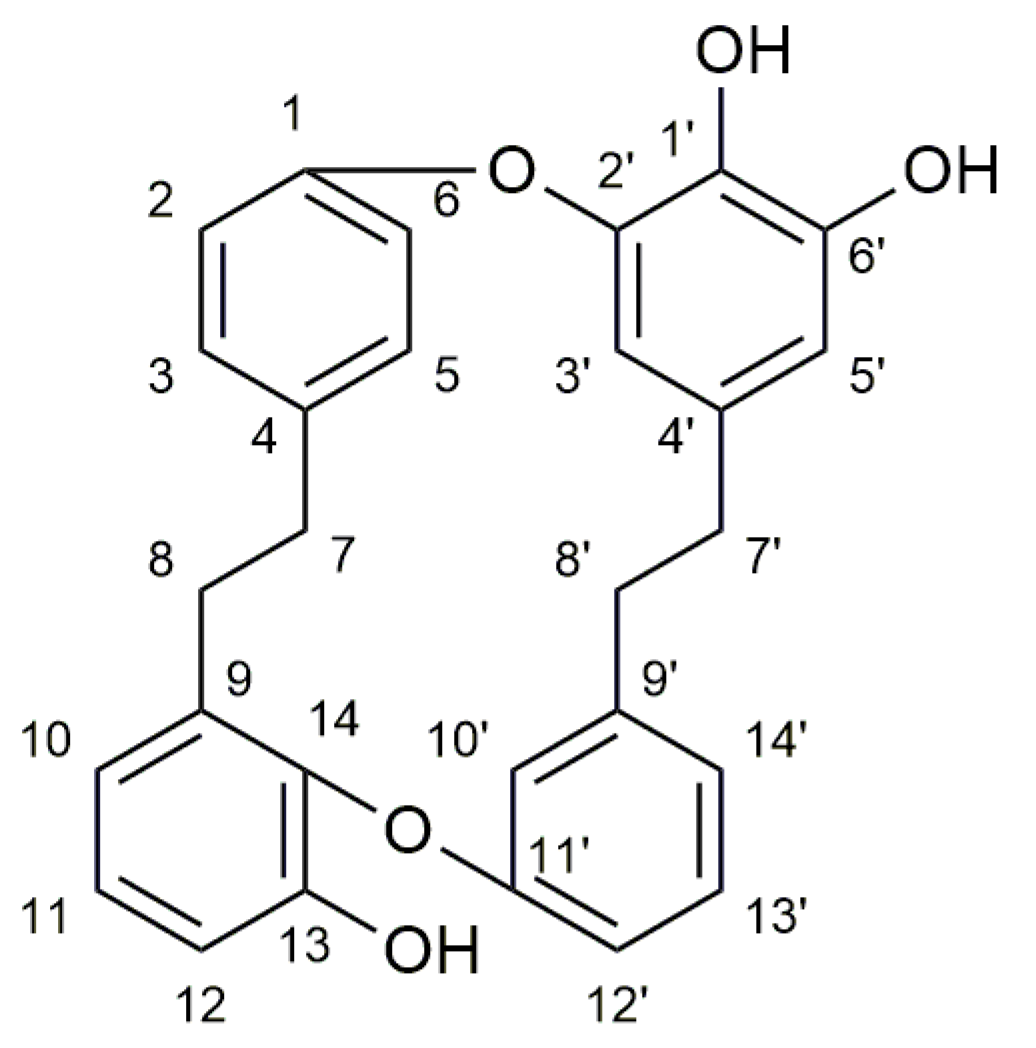

2.2. Bibenzyls and Bisbibenzyls

2.3. Other Compounds Found in M. polymorpha

3. Biological Activities

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asakawa, Y.; Ludwiczuk, A. Chemical Constituents of Bryophytes: Structures and Biological Activity. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81, 641–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwiczuk, A.; Asakawa, Y. Bryophytes as a Source of Bioactive Volatile Terpenoids - A Review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 132, 110649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asakawa, Y. Chemical Constituents of the Hepaticae. In Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products; Herz, W., Grisebach, H., Kirby, G.W., Heidelberger, M., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, 1982; Vol. 42, pp. 1–285. ISBN 978-3-7091-8677-0. [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa, Y. Chemical Constituents of the Bryophytes. In Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products; Herz, W., Kirby, G. W., Moore, R. E., Steglich, W., Tamm, Ch., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, 1995; Vol. 65, pp. 1–618. ISBN 978-3-7091-6896-7. [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa, Y.; Ludwiczuk, A.; Nagashima, F. Chemical Constituents of Bryophytes. Bio- and Chemical Diversity, Biological Activity, and Chemosystematics. In Progress in the chemistry of organic natural products; Kinghorn, A., Falk, D., Kobayashi, J., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Vienna, 2013; Vol. 95, p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Bischler-Causse, H. Marchantia L. The Asiatic and Oceanic Taxa.; Bryophytorium Bibliotheca; Cramer: Vaduz, 1989; Vol. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Bischler-Causse, H. Marchantia L. The European and African Taxa.; Bryophytorium Bibliotheca; Cramer: Stuttgart, 1993; Vol. 45. [Google Scholar]

- M. C. Boisselier-Dubayle; M. F. Jubier; B. Lejeune; H. Bischler Genetic Variability in the Three Subspecies of Marchantia Polymorpha (Hepaticae): Isozymes, RFLP and RAPD Markers. TAXON 1995, 44, 363–376. [CrossRef]

- Linde, A.-M.; Sawangproh, W.; Cronberg, N.; Szövényi, P.; Lagercrantz, U. Evolutionary History of the Marchantia Polymorpha Complex. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asakawa, Y.; Toyota, M.; Tori, M.; Hashimoto, T. Chemical Structures of Macrocyclic Bis(Bibenzyls) Isolated from Liverworts (Hepaticae). Spectroscopy 2000, 14, 149–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suire, C. A Comparative, Transmission-Electron Microscopic Study on the Formation of Oil Bodies in Liverworts. J. Hattori Bot. Lab. 2000, 89, 209–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, R.-L. The Oil Bodies of Liverworts: Unique and Important Organelles in Land Plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2013, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, F.; Banić, E.; Florent, S.N.; Kanazawa, T.; Goodger, J.Q.D.; Mentink, R.A.; Dierschke, T.; Zachgo, S.; Ueda, T.; Bowman, J.L.; et al. Oil Body Formation in Marchantia Polymorpha Is Controlled by MpC1HDZ and Serves as a Defense against Arthropod Herbivores. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, 2815–2828.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kempinski, C.; Zhuang, X.; Norris, A.; Mafu, S.; Zi, J.; Bell, S.A.; Nybo, S.E.; Kinison, S.E.; Jiang, Z.; et al. Molecular Diversity of Terpene Synthases in the Liverwort Marchantia Polymorpha. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 2632–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelmasiewicz, M.; Świątek, Ł.; Ludwiczuk, A. Phytochemical Profile and Anticancer Potential of Endophytic Microorganisms from Liverwort Species, Marchantia Polymorpha L. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, Y.; Toyota, M.; Nakaishi, E.; Tada, Y. Distribution of Terpenoids and Aromatic Compounds in New Zealand Liverworts. J. Hattori Bot. Lab. 1996, 80, 271–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, Y.; Baser, K.H.C.; Erol, B.; Von Reuß, S.; Konig, W.A.; Ozenoglu, H.; Gokler, I. Volatile Components of Some Selected Turkish Liverworts. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2018, 13, 1934578X1801300729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, A.; Nakayama, N.; Nakayama, M. Enantiomeric Type Sesquiterpenoids of the Liverwort Marchantia Polymorpha. Phytochemistry 1985, 24, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, Y.; Toyota, M.; Bischler, H.; Hattori, S. Comparative Study of Chemical Constituents of Marchantia Species. J. Hattori Bot. Lab. 1984, 57, 383. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwiczuk, A.; Nagashima, F.; Gradstein, S.; Asakawa, Y. Volatile Components from Selected Mexican, Ecuadorian, Greek, German and Japanese Liverworts. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2008, 3, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, Y.; Tori, M.; Masuya, T.; Frahm, J.P. Ent-Sesquiterpenoids and Cyclic Bis(Bibenzyls) from the German Liverwort Marchantia Polymorpha. Phytochemistry 1990, 29, 1577–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, Y.; Tori, M.; Takikawa, K.; Krishnamurty, H.G.; Kar, S.K. Cyclic Bis(Bibenzyls) and Related Compounds from the Liverworts Marchantia Polymorpha and Marchantia Palmata. Phytochemistry 1987, 26, 1811–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, Y.; Matsuda, R.; Takemoto, T.; Hattori, S.; Mizutani, M.; Inoue, H.; Suire, C.; Huneck, S. Chemosystematics of Bryophytes VII. The Distribution of Terpenoids and Aromatic Compounds in Some European and Japanese Hepaticae. J. Hattori Bot. Lab. 1981, 50, 107. [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa, Y.; Tokunaga, N.; Toyota, M.; Takemoto, T.; Suire, C. Chemosystematics of Bryophytes I. The Distribution of Terpenoids of Bryophytes. J. Hattori Bot. Lab. 1979, 45, 385. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, B.J.; Perold, G.W. (S)-2-Hydroxycuparene [p-(1,2,2-Trimethylcyclopentyl)-o-Cresol] and 3,4′-Ethylenebisphenol from a Liverwort, Marchantia Polymorpha Linn. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin 1 1974, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Syrkin Wurtele, E.; Lamotte, C.E. Abscisic Acid Is Present in Liverworts. Int. J. Plant Biochem. 1994, 37, 625–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyota, M.: Chemical Constituents of Marchantia Polymorpha, Riccardia Multifida and Plagiochila Genus (Hepaticae). Ph. D. Thesis, 1987. Ph.D. Thesis, Tokushima Bunri University: Tokushima, 1987.

- Gleizes, M.; Pauly, G.; Suire, C. Les Essences Extraites Du Thalle Des Hepatiques II. - La Fraction Sesquiterpenique de l’Essence de Marchantia Polymorpha L. (Marchantiale). Botaniste 1973, 209.

- Rieck, A.; Bülow, N.; Fricke, C.; Saritas, Y.; König, W.A. (−)-1(10),11-Eremophiladien-9β-Ol from the Liverwort Marchantia Polymorpha Ssp. Aquatica. Phytochemistry 1997, 45, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanasaki, T.; Ohta, K. Isolation and Identification of Costunolide as a Piscicidal Component of Marchantia Polymorpha. Agric. BioI. Chern. (Tokyo) 40, 1239 (1976). Agric BioI Chern Tokyo 1976, 40, 1239. [Google Scholar]

- Van Nguyen, N.K.; Tran, H.-D.-T.; Duong, T.-H.; Tuyen Pham, N.K.; Trang Nguyen, T.Q.; Thao Nguyen, T.N.; Chavasiri, W.; Nguyen, N.-H.; Tri Nguyen, H. Bio-Guided Isolation of Alpha-Glucosidase Inhibitory Compounds from Vietnamese Liverwort Marchantia Polymorpha : In Vitro and in Silico Studies. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 35481–35492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, Y.; Toyota, M.; Takeda, R.; Matsuda, R.; Gradstein, S.R.; Takikawa, K.; Takemoto, T. New Diterpenoids from Lejeuneaceae, Porellaceae and Marchantiaceae.; Nagasaki, Japan, 1983.

- Asakawa, Y.; Okada, K.; Perold, G.W. Distribution of Cyclic Bis(Bibenzyls) in the South African Liverwort Marchantia Polymorpha. Phytochemistry 1988, 27, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, G.W.; Wolfe, G.R.; Salt, T.A.; Chiu, P.L. Sterols of Bryophytes with Emphasis on the Configuration at C-24. In Bryophytes: Their Chemistry and Chemical Taxonomy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1990; p. 103. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, P.-L.; W. Patterson, G.; P. Fenner, G. Sterols of Bryophytes. Phytochemistry 1985, 24, 263–266. [CrossRef]

- Abe, S.; Ohta, Y. Lunularic Acid in Cell Suspension Cultures of Marchantia Polymorpha. Phytochemistry 1983, 22, 1917–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, K.P. Marchantia Polymorpha (Liverwort): Culture and Production of Metabolites. In Medicinal and Aromatic Plants IX; Bajaj, Y.P.S., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1996; pp. 186–201. ISBN 978-3-662-08618-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ohta, Y.; Abe, S.; Komura, H.; Kobayashi, M. Prelunularic Acid, a Probable Immediate Precursor of Lunularic Acid, in Suspension-Cultured Cells of Marchantia Polymorpha. J. Hattori Bot. Lab. 1984, 56, 249. [Google Scholar]

- Ohta, Y.; Abe, S.; Komura, H.; Kobayashi, M. Prelunularic Acid, a Probable Immediate Precursor of Lunularic Acid. First Example of a “Prearomatic” Intermediate in the Phenylpropanoid-Polymalonate Pathway. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, Y.; Katoh, K.; Takeda, R. Growth and Secondary Metabolites Production in Cultured Cells of Liverworts. In Bryophyte Development: Physiology and Biochemistry; Chopra, R.N., Bhatla, S.C., Eds.; CRC Press, 1990.

- Qu, J.B.; Xie, C.F.; Ji, M.; Shi, Y.Q.; Lou, H.X. Water-Soluble Constituents from the Liverwort Marchantia Polymorpha. Helv. Chim. Acta 2007, 90, 2109–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Guo, H.F.; Lou, H.X. Three New Bibenzyl Derivatives from the Chinese Liverwort Marchantia Polymorpha L. Helv. Chim. Acta 2007, 90, 748–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C.; Qu, J.B.; Lou, H.X. Antifungal Bis[Bibenzyls] from the Chinese Liverwort Marchantia Polymorpha L. Chem. Biodivers. 2006, 3, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabovljević, M.S.; Vujičić, M.; Wang, X.; Garraffo, H.M.; Bewley, C.A.; Sabovljević, A. Production of the Macrocyclic Bis-Bibenzyls in Axenically Farmed and Wild Liverwort Marchantia Polymorpha L. Subsp. Ruderalis Bischl. et Boisselier. Plant Biosyst. - Int. J. Deal. Asp. Plant Biol. 2017, 151, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, Y. Phytochemistry of Hepaticae: Isolation of Biologically Active Aromatic Compounds and Terpenoids. Rev. Latinoam. Quím. 1984, 14, 109. [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa, Y.; Toyota, M.; Matsuda, R.; Takikawa, K.; Takemoto, T. Distribution of Novel Cyclic Bisbibenzyls in Marchantia and Riccardia Species. Phytochemistry 1983, 22, 1413–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, Y.; Matsuda, R.; Toyota, M.; Suire, C.; Takemoto, T.; Hattori, S. Phylogenetic Evolution of the Hepaticae Using by Chemical Character. , P. 92 (1981). In Proceedings of the Symposium Papers; Yamaguchi, Japan., 1981; p. 92.

- Konoshima, M. Phytochemical Studies on the Liverworts Marchantia, Reboulia and Wiesnerella. Master’s Thesis, Tokushima Bunri University, Tokushima, Japan, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Oiso, Y.; Toyota, M.; Asakawa, Y. Occurrence of Digalactopyranosylmonoacylglycerol in the Liverwort Marchantia Polymorpha. J. Hattori Bot. Lab. 1999, 86, 169. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, E.O.; Markham, K.R.; Moore, N.A.; Porter, L.J.; Wallace, J.W. Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Implications of Comparative Flavonoid Chemistry of Species in the Family Marchantiaceae. J. Hattori Bot. Lab. 1979, 45, 185. [Google Scholar]

- Markham, K.R.; Porter, L.J. Flavonoids of the Liverwort Marchantia Polymorpha. Phytochemistry 1974, 13, 1937–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markham, K.R.; Porter, L.J. Production of an Auron by Bryophytes in the Reproductive Phase. Phytochem. 17, 159-160 (1978). Phytochemistry 1978, 17, 159–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, S.; Burkhardt, G.; Becker, H. Riccionidins a and b, Anthocyanidins from the Cell Walls of the Liverwort Ricciocarpos Natans. Phytochemistry 1993, 35, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saruwatari, M.; Takio, S.; Ono, K. Low Temperature-Induced Accumulation of Eicosapentaenoic Acids in Marchantia Polymorpha Cells. Phytochemistry 1999, 52, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinmen, Y.; Katoh, K.; Shimizu, S.; Jareonkitmongkol, S.; Yamada, H. Production of Arachidonic Acid and Eicosapentaenoic Acids by Marchantia Polymorpha in Cell Culture. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 3255–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Esaki, T.; Kenmoku, H.; Koeduka, T.; Kiyoyama, Y.; Masujima, T.; Asakawa, Y.; Matsui, K. Direct Evidence of Specific Localization of Sesquiterpenes and Marchantin A in Oil Body Cells of Marchantia Polymorpha L. Phytochemistry 2016, 130, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, N.C.T.; Tan, T.Q.; Lien, D.T.M.; Huong, N.T.M.; Tuyen, P.N.K.; Phung, N.K.P.; Phuong, Q.N.D.; Thu, N.T.H. Five Phenolic Compounds from Marchantia Polymorpha L. and Their in Vitro Antibacterial, Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Activities. Vietnam J. Chem. 2020, 58, 810–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friederich, S.; Maier, U.H.; Deus-Neumann, B.; Yoshinori Asakawa; H. Zenk, M. Biosynthesis of Cyclic Bis(Bibenzyls) in Marchantia Polymorpha. Phytochemistry 1999, 50, 589–598. [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, Y.; Ludwiczuk, A.; Novakovic, M.; Bukvicki, D.; Anchang, K.Y. Bis-Bibenzyls, Bibenzyls, and Terpenoids in 33 Genera of the Marchantiophyta (Liverworts): Structures, Synthesis, and Bioactivity. J. Nat. Prod. 2022, 85, 729–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asakawa, Y.; Ludwiczuk, A.; Nagashima, F. Phytochemical and Biological Studies of Bryophytes. Phytochemistry 2013, 91, 52–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamory, E.; Keseru, G.M.; Papp, B. Isolation and Antibacterial Activity of Marchantin A, a Cyclic Bis(Bibenzyl) Constituent of Hungarian Marchantia Polymorpha. Planta Med. 1995, 61, 387–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asakawa, Y.; Toyota, M.; Nagashima, F.; Hashimoto, T. Chemical Constituents of Selected Japanese and New Zealand Liverworts. 2008, 3, 289–300. [CrossRef]

- Ludwiczuk, A.; Raharivelomanana, P.; Pham, A.; Bianchini, J.P.; Asakawa, Y. Chemical Variability of the Tahitian Marchantia Hexaptera Reich. Phytochem. Lett. 2014, 10, xcix–ciii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyota, M.; Asakawa, Y. Sesquiterpenoids and Cyclic Bis(Bibenzyls) from the Pakistani Liverwort Plagiochasma Appendiculatum. J. Hattori Bot. Lab. 1999, 86, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.L.; Zhang, J.Z.; Liu, X.Y.; Deng, J.Q.; Zhu, T.T.; Ni, R.; Tan, H.; Sheng, J.Z.; Lou, H.X.; Cheng, A.X. Identification and Characterization of Two Bibenzyl Glycosyltransferases from the Liverwort Marchantia Polymorpha. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Ludwiczuk, A.; Wei, G.; Chen, X.; Crandall-Stotler, B.; Bowman, J.L. Terpenoid Secondary Metabolites in Bryophytes: Chemical Diversity, Biosynthesis and Biological Functions. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2018, 37, 210–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Kityania, S.; Nath, R.; Das, S.; Nath, D.; Talukdar, A.D. Bioactive Compounds from Bryophytes. In Bioactive Compounds in Bryophytes and Pteridophytes; Murthy, H.N., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-3-030-97415-2. [Google Scholar]

- Gahtori, D.; Chaturvedi, P. Antifungal and Antibacterial Potential of Methanol and Chloroform Extracts of Marchantia Polymorpha L. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2011, 44, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mewari, N.; Kumar, P. Evaluation of Antifungal Potential of Marchantia Polymorpha L., Dryopteris Filix-Mas (L.) Schott and Ephedra Foliata Boiss. against Phyto Fungal Pathogens. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2011, 44, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, H.; Shi, F.; Li, M.W.; Chen, X.; Liao, L.; Li, J. Screening of the Antibacterial Activity of Accompanying Weed Extracts against Fusarium Solani[伴生杂草提取液对花椒根腐病菌的抑菌活性]. Chin. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. 2023, 29, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryophyte Development: Physiology and Biochemistry; Chopra, R.N., Bhatla, S.C., Eds.; CRC Press, 1990.

- Guo, X.L.; Leng, P.; Yang, Y.; Yu, L.G.; Lou, H.X. Plagiochin E, a Botanic-derived Phenolic Compound, Reverses Fungal Resistance to Fluconazole Relating to the Efflux Pump. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 104, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivković, I.M.; Bukvički, D.R.; Novaković, M.M.; Ivanović, S.G.; Stanojević, O.Ј.; Nikolić, I.С.; Veljić, M.M. Antibacterial Properties of Thalloid Liverworts Marchantia Polymorpha L., Conocephalum Conicum (L.) Dum. and Pellia Endiviifolia (Dicks.) Dumort. J Serb Chem Soc 2021, 86, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.Y.; Chen, T.; Cao, J.F. Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Metabolites From the Cultured Suspension Cells of Marchantia Polymorpha L. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeeva, L.R.; Dzhabrailova, S.M.; Sharipova, M.R. Cis-Prenyltransferases of Marchantia Polymorpha: Phylogenetic Analysis and Perspectives for Use as Regulators of Antimicrobial Agent Synthesis. Mol. Biol. 2022, 56, 902–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.S.R.E.; Omarsdottir, S.; Thorsteinsdottir, J.B.; Ogmundsdottir, H.M.; Olafsdottir, E.S. Synergistic Cytotoxic Effect of the Microtubule Inhibitor Marchantin A from Marchantia Polymorpha and the Aurora Kinase Inhibitor MLN8237 on Breast Cancer Cells In Vitro. Planta Med. 2012, 78, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaweł-Bęben, K.; Osika, P.; Asakawa, Y.; Antosiewicz, B.; Głowniak, K.; Ludwiczuk, A. Evaluation of Anti-Melanoma and Tyrosinase Inhibitory Properties of Marchantin A, a Natural Macrocyclic Bisbibenzyl Isolated from Marchantia Species. Phytochem. Lett. 2019, 31, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, T.; Sahu, V.; Meena, S.; Pal, M.; Asthana, A.K.; Datta, D.; Upreti, D.K. A Comparative Study of in Vitro Cytotoxicity and Chemical Constituents of Wild and Cultured Plants of Marchantia Polymorpha L. South Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 157, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Aipire, A.; Xia, L.; Halike, X.; Yuan, P.; Sulayman, M.; Wang, W.; Li, J. Marchantia Polymorpha L. Ethanol Extract Induces Apoptosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells via Intrinsic- and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Associated Pathways. Chin. Med. 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelmasiewicz, M.; Świątek, Ł.; Ludwiczuk, A. Chemical and Biological Studies of Endophytes Isolated from Marchantia Polymorpha. Molecules 2023, 28, 2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwai, Y.; Murakami, K.; Gomi, Y.; Hashimoto, T.; Asakawa, Y.; Okuno, Y.; Ishikawa, T.; Hatakeyama, D.; Echigo, N.; Kuzuhara, T. Anti-Influenza Activity of Marchantins, Macrocyclic Bisbibenzyls Contained in Liverworts. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e19825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, S.; Omarsdottir, S.; Bwalya, A.G.; Nielsen, M.A.; Tasdemir, D.; Olafsdottir, E.S. Marchantin A, a Macrocyclic Bisbibenzyl Ether, Isolated from the Liverwort Marchantia Polymorpha, Inhibits Protozoal Growth in Vitro. Phytomedicine 2012, 19, 1191–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoguro, K.; Ishiyama, A.; Iwatsuki, M.; Namatame, M.; Nishihara-Tukashima, A.; Kiyohara, H.; Hashimoto, T.; Asakawa, Y.; Ōmura, S.; Yamada, H. In Vitro Antitrypanosomal Activity of Bis(Bibenzyls)s and Bibenzyls from Liverworts against Trypanosoma Brucei. J. Nat. Med. 2012, 66, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.J.; Wu, C.L.; Lin, C.W.; Chi, L.L.; Chen, P.Y.; Chiu, C.J.; Huang, C.Y.; Chen, C.N. Marchantin A, a Cyclic Bis(Bibenzyl Ether), Isolated from the Liverwort Marchantia Emarginata Subsp. Tosana Induces Apoptosis in Human MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells. Cancer Lett. 2010, 291, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartner, C.; Bors, W.; Michel, C.; Franck, U.; Müller-Jakic, B.; Nenninger, A.; Asakawa, Y.; Wagner, H. Effect of Marchantins and Related Compounds on 5-Lipoxygenase and Cyclooxygenase and Their Antioxidant Properties: A Structure Activity Relationship Study. Phytomedicine 1995, 2, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, A.; Ishtiaq, S.; Kamran, S.H.; Youssef, F.S.; Lashkar, M.O.; Ahmed, S.A.; Ashour, M.L. UHPLC−QTOF−MS Metabolic Profiling of Marchantia Polymorpha and Evaluation of Its Hepatoprotective Activity Using Paracetamol-Induced Liver Injury in Mice. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Cao, H.; Gao, Y.; Zhong, M.; Wang, Y.; Guan, Y.; Wei, R.; Jin, L. Marchantia Polymorpha L. Flavonoids Protect Liver From CCl4-Induced Injury by Antioxidant and Gene-Regulatory Effects. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2022, 28, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harinantenaina, L.; Quang, D.N.; Takeshi, N.; Hashimoto, T.; Kohchi, C.; Soma, G.I.; Asakawa, Y. Bis(Bibenzyls) from Liverworts Inhibit Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inducible NOS in RAW 264.7 Cells: A Study of Structure-Activity Relationships and Molecular Mechanism. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 1779–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esplugues, J.V. NO as a Signalling Molecule in the Nervous System. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 135, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwiczuk, A.; Asakawa, Y. Terpenoids and Aromatic Compounds from Bryophytes and Their Central Nervous System Activity. Curr. Org. Chem. 2020, 24, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keseru, G.M.; Nógrádi, M. The Biological Activity of Cyclic Bis(Bibenzyls): A Rational Approach. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1995, 3, 1511–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelmasiewicz, M.; Świątek, Ł.; Gibbons, S.; Ludwiczuk, A. Bioactive Compounds Produced by Endophytic Microorganisms Associated with Bryophytes—The “Bryendophytes”. Molecules 2023, 28, 3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Compounds | Formula | Plant origin | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MONOTERPENOIDS | |||||

| 1 | Limonene | C10H16 | USA (axenic culture) | [14] | |

| SESQUITERPENOIDS | |||||

| 2 | β-Acoradiene | C15H24 | Poland | [15] | |

| 3 | α-Neocallitropsene | C15H26 | Poland | ||

| 4 | β-Alaskene | C15H24 | Poland | [15] | |

| 5 | Acorenone B | C15H24O | Poland | [15] | |

| 6 | α-Gurjunene | C15H24 | New Zealand, USA (axenic culture) | [14,16] | |

| 7 | Aromadendrene | C15H24 | Turkey | [17] | |

| 8 | α-Barbatene | C15H24 | Japan | [18] | |

| 9 | β-Barbatene | C15H24 | Japan | [18,19,20] | |

| 10 | α-Chamigrene | C15H24 | Japan, Germany, India | [19,20,21,22] | |

| 11 | β-Chamigrene | C15H24 | Germany, India, Poland, USA (axenic culture) | [14,15,19,21,22,23,24] | |

| 12 |

ent-9-oxo-α-Chamigrene (Laurencenone C) |

C15H22O | Japan, Germany, Poland | [20,21,23] | |

| 13 | Cuparene | C15H24 | Turkey, Japan, Poland, USA (axenic culture) | [14,15,17,18,24] | |

| 14 | α-Cuprenene | C15H24 | Japan, Poland | [15,20] | |

| 15 | β-Cuprenene | C15H24 | [19] | ||

| 16 | γ-Cuprenene | C15H24 | Japan | [20] | |

| 17 | δ-Cuprenene | C15H24 | Japan, Poland | [15,20] | |

| β-Microbiotene | C15H24 | Poland | [15] | ||

| 18 | 2-Cuparenol (= Cuparophenol, δ-Cuparenol) | C15H22O | Turkey, South Africa | [17,18,23,25] | |

| 19 | ent-Cuprenenol | C15H26O | [19] | ||

| 20 | Cyclopropanecuparenol | C15H26O | Japan, Poland | [15,19,20] | |

| 21 | epi-Cyclopropanecuparenol | C15H26O | Poland | [15,19] | |

| 22 | α-Selinene | C15H24 | New Zealand, Poland | [15,16] | |

| 23 | ent-β-Selinene | C15H24 | India | [19,22] | |

| 24 | α-Eudesmol | C15H26O | Turkey | [17] | |

| 25 | (2Z,4E)-Abscisic acid | C15H20O3 | [26] | ||

| 26 | (2E,4E)-Abscisic acid | C15H20O3 | [26] | ||

| 27 | ent-Thujopsene | C15H24 | Japan, Poland, USA (axenic culture) | [14,15,18,19,20,27] | |

| 28 | ent-Thujopsan-7β-ol | C15H26O | Japan, Germany | [20,21] | |

| 29 |

ent-Thujopsenone (= Thujops-3-en-5-one) |

C15H22O | Japan | [18,19,20] | |

| 30 | Bicycloelemene | C15H24 | [19] | ||

| 31 | β-Elemene | C15H24 | [19,28] | ||

| 32 | γ-Elemene | C15H24 | [19] | ||

| 33 | δ-Elemene | C15H24 | [23,24] | ||

| 34 | Eremophilene | C15H24 | [28] | ||

| 35 | 1(10),11-Eremophiladien-9β-ol | C15H24O | Germany | [29] | |

| 36 | Costunolide | C15H20O2 | Japan | [30] | |

| 37 | α-Himachalene | C15H24 | USA (axenic culture) | [14,24] | |

| 38 | β-Bisabolene | C15H24 | [19] | ||

| 39 | β-Caryophyllene | C15H24 | [19] | ||

| 40 | α-Cedrene | C15H24 | [19] | ||

| 41 | 7-epi-α-Cedrene | C15H24 | Poland | [15] | |

| 42 | β-Cedrene | C15H24 | [28] | ||

| 43 | β-Herbertenol | C15H22O | Japan, Poland | [15,18,19] | |

| 44 | ent-α-Herbertenol | C15H22O | Germany | [21] | |

| 45 | Widdrol | C15H26O | Japan | [18,19] | |

| DITERPENOIDS | |||||

| 46 | Marchanol | C20H32O2 | Vietnam | [31] | |

| 47 | Labda-7,13E-dien-15-ol | C20H34O | [19,27,32] | ||

| 48 | Vitexilactone | C22H34O4 | Vietnam | [31] | |

| 49 | Phytol | C20H40O | South Africa, Poland | [15,19,33] | |

| STEROLS and TRITERPENOIDS | |||||

| 50 | Campesterol | C28H48O | South Africa, Germany, India | [21,22,33,34] | |

| 51 | Brassicasterol | C28H46O | [23] | ||

| 52 | Dihydrobrassicasterol | C28H48O | [34,35] | ||

| 53 | Stigmasterol | C29H48O | South Africa, Germany | [21,33] | |

| 54 | Sitosterol | C29H50O | South Africa, Germany | [21,33,34] | |

| 55 | Clionasterol (24β-ethyl) | C29H50O | [34,35] | ||

| 56 | 12-Oleanene-3-one | C30H48O | Vietnam | [31] | |

| 57 | Ursolic acid | C30H48O3 | Vietnam | [31] | |

| 58 | 3,11-Dioxoursolic acid | C30H44O4 | Vietnam | [31] | |

| BIBENZYLS | |||||

| 59 | Lunularin | C14H14O2 | Germany, Vietnam | [19,21,31] | |

| 60 | Lunularic acid | C15H14O4 | Cell culture, Japan Germany | [36,37,38] | |

| 61 | Prelunularic acid | C15H16O5 | [38,39,40] | ||

| 62 | 2,5-Di-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl- 4′-hydroxybibenzyl | C26H34O13 | [41] | ||

| 63 | 2-[3-(Hydroxymethyl) phenoxy]-3-[2- (4-hydroxyphenyl) ethyl]phenol | C21H20O4 | China | [42] |

|

| BISBIBENZYLS | |||||

| 64 | Riccardin C | C28H24O4 | South Africa, India, Vietnam | [22,31,33] | |

| 65 | Riccardin D | C28H24O4 | China | [43] | |

| 66 | Riccardin H | C31H28O4 | China | [43] | |

| 67 | Isoriccardin C | C28H24O4 | India, Vietnam | [22,31] | |

| 68 | Isoriccardin D | C28H24O4 | China | [42] | |

| 69 | 13,13′-O-Isopropylidenericcardin D | C31H28O4 | China | [43] | |

| 70 | Polymorphatin A | C28H24O4 | China | [42] | |

| 71 | Marchantin A | C28H24O5 | China, Germany, India, Japan, Serbia (natural and cultured), Vietnam | [19,21,22,24,27,31,43,44,45,46,47] | |

| 72 | 7′,8′-Dehydromarchantin A | C28H24O4 | Serbia (cell culture) | [44] | |

| 73 | Marchantin B | C28H24O6 | China Germany Japan | [19,21,27,43,45,46] | |

| 74 | Marchantin C | C28H24O4 | South Africa, Germany, India, Japan, Serbia (cell culture) | [19,21,22,27,33,44,45,46] | |

| 75 | Marchantin D | C28H24O6 | Germany, India, Japan | [19,21,22,27,45,46,48] | |

| 76 | Marchantin E | C29H26O6 | China, Germany, India, Japan, Serbia (cell culture) | [19,21,22,27,43,44,45,46] | |

| 77 | Marchantin F | C28H24O7 | South Africa, | [33] | |

| 78 | Marchantin G | C28H22O6 | [48] | ||

| 79 | Marchantin H | C28H24O5 | South Africa, | [33] | |

| 80 | Marchantin J | C30H28O6 | China, Germany | [21,42] | |

| 81 | Marchantin K | C29H26O7 | Germany, Vietnam | [21,31] | |

| 82 | Marchantin L | C28H24O6 | Germany | [21] | |

| 83 | Isomarchantin C | C28H24O4 | India | [22] | |

| 84 | Neomarchantin A | C28H24O4 | China | [43] | |

| 85 | Perrottetin E | C28H26O4 | China, India | [22,42] | |

| OTHER AROMATICS | |||||

| 86 | 3R-(3,4-Dimethoxybenzyl)-5,7-dimethoxyphthalide | C19H20O6 | Vietnam | [31] | |

| 87 | Marchatoside | C20H22O7 | Vietnam | [31] | |

| 88 | 3-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)- 8-hydroxyisocoumarin | C15H10O5 | Germany (cell culture) | [37] | |

| 89 | 2,3-Dimethoxy-7-hydroxy- phenanthrene |

C16H14O3 | Germany (cell culture) | [37] | |

| 90 | 2,7-Dihydroxy-3-methoxy- phenanthrene |

C15H12O3 | Germany (cell culture) | [37] | |

| 91 | 3,3′-Dimethoxy-2,2′,7,7′-tetra- hydroxy-1,1′-biphenanthrene |

C30H22O6 | Germany (cell culture) | [37] | |

| 92 | 2-Hydroxy-3,7-dimethoxy phenanthrene | C16H14O3 | India | [22] | |

| 93 | m-Hydroxybenzaldehyde | C7H6O2 | Germany | [21] | |

| 94 | p-Hydroxybenzaldehyde | C7H6O2 | South Africa, Germany | [21,33] | |

| 95 | 3-Methoxy-2,2′,3′,7,7′-pentahydroxy- 1,1′-biphenanthrene | C29H20O6 | Germany (cell culture) | [37] | |

| 96 | 2,2′,3,3′,7,7′-Hexahydroxy- 1,1′-biphenanthrene | C28H18O6 | Germany (cell culture) | [37] | |

| 97 | 2-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-ethyl-β-d-allopyranoside | C14H20O8 | [41] | ||

| 98 | 2-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-ethyl-β-d-glucopyranoside | C14H20O8 | [41] | ||

| 99 | 2-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-ethyl- O-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-d- allopyranoside | C20H30O12 | [41] | ||

| 100 | 2-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-ethyl- O-β-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→6)-O-β-d-allopyranoside | C19H28O12 | [41] | ||

| 101 | Salidroside | C14H20O7 | [49] | ||

| 102 | β-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)ethyl- O-β-d-glucoside | C14H20O8 | Germany (cell culture) | [37,49] | |

| 103 | Indole acetic acid | C9H7O2N | [26] | ||

| FLAVONOIDS | |||||

| 104 | Apigenin | C15H10O5 | Germany (cell culture); New Zealand |

[37,50,51] | |

| 105 | Apigenin-7-O-β-D-glucuronide | C21H18O11 | New Zealand | [50,51] | |

| 106 | Apigenin-7,4'-di-O-glucuronide | C27H26O17 | New Zealand | [50,51] | |

| 107 | Luteolin | C15H10O6 | Germany | [21,50,51] | |

| 108 | Luteolin-7-O-β-D-glucuronide | C21H18O12 | New Zealand | [50,51] | |

| 109 | Luteolin-7,3'-di-O-β-glucuronide | C27H26O18 | New Zealand | [50,51] | |

| 110 | Luteolin-7,4'-di-O-β-glucuronide | C27H26O18 | New Zealand | [50,51] | |

| 111 | Luteolin-3'4'-di-O-β-glucuronide | C27H26O18 | New Zealand | [50,51] | |

| 112 | Luteolin-3'-O-β-glucuronide | C21H18O12 | New Zealand | [50,51] | |

| 113 | Luteolin-7,3'4'-tri-O-β-glucuronide | New Zealand | [50,51] | ||

| 114 | Artemetin | C20H20O8 | Vietnam | [31] | |

| 115 | Kaempferol | C15H10O6 | Vietnam | [31] | |

| 116 | Quercetin | C15H10O7 | Vietnam | [31] | |

| 117 | Aureusidin-6-O-g1ucuronide | C21H18O12 | New Zealand | [52] | |

| 118 | 5,3′,4′-Trihydroxyisoflavone- 7-O-β-d-glucopyranoside ( = Orobol-7-O-glucoside) |

C21H20O11 | [41] | ||

| 119 | Riccionidin A | C15H9O6 | [53] | ||

| 120 | Riccionidin B | C30H17O12 | [53] | ||

| LIPIDS | |||||

| 121 | Palmitic acid (16:0) (= Hexadecanoic acid) |

C16H32O2 | Cell culture Japan, sporophyte |

[20,54] | |

| 122 | Ethyl palmitate (= Hexadecanoic acid ethyl ester) | C18H36O2 | Japan, sporophyte | [20] | |

| 123 | Stearic acid (18:0) (= Octadecanoic acid) |

C18H36O2 | Cell culture |

[54] | |

| 124 | Palmitoleic acid (16:1n-7) (= 9-Hexadecenoic acid) |

C16H30O2 | Cell culture |

[54] | |

| 125 | Oleic acid (18:1n-9) (= 9-Octadecenoic acid) |

C18H34O2 | Cell culture |

[54] | |

| 126 | Linoleic acid (18:2n-6) (= 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid) |

C18H32O2 | Japan, sporophyte Cell culture |

[20,54] | |

| 127 | α-Linolenic acid (18:3n-3) (= 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid) |

C18H30O2 | Cell culture |

[54] | |

| 128 | Arachidonic acid (20:4n-6) (= 5,8,11,14-Eicosatetraenoic acid) |

C20H32O2 | Cell culture |

[54,55] | |

| 129 | EPA (20:5n-3) (= Eicosapentaenoic acid) |

C20H30O2 | Cell culture |

[54,55] | |

| 130 | Oxacycloheptadecan-2-one | C16H30O2 | Japan, sporophyte | [20] | |

| OTHER COMPOUNDS | |||||

| 131 | Shikimic acid 4-(β-d-xylopyranoside) | C12H18O9 | [41] | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).