1. Introduction

The assessment of risk of bias (RoB) is fundamental to evidence-based research, ensuring the methodological rigor of studies and identifying flaws that could skew the true effect of an intervention (Higgins et al. 2011; Faggion 2016; Sterne et al. 2019). Recognizing the limitations of the original RoB tool, the Cochrane Collaboration introduced the Revised Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (RoB2) in 2019 as an evolution aimed at improving the accuracy and comprehensiveness of bias assessment (Sterne et al. 2019). RoB2 addresses previous shortcomings by focusing on five key domains: bias due to the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, outcome measurement, and the selection of reported outcomes (Sterne et al. 2019). This refined approach was designed to set a new gold standard for bias assessment, offering a more detailed and structured evaluation process. Despite the advancements offered by RoB2, many systematic reviews continue to employ the original RoB tool, raising concerns about the consistency and reliability of bias assessments across studies from different methodological aspects (Higgins et al. 2011; Faggion 2016; Moon and Rao 2021). The implications of this practice are particularly unclear in the field of dental research, where the specificity of clinical trials may lead to differences in bias assessment outcomes when using RoB2 compared to its predecessor (Cioffi and Farella 2011; Saltaji et al. 2017). The potential for upgraded 2019; Ortiz et al. 2021; Limones et al. 2022 Sep 12). RoB scores with RoB2, due to its more nuanced criteria, could have significant consequences for the synthesis of evidence and decision-making processes in dental research. However, ensuring the adherence to a new tool is of paramount importance (De Bruin et al. 2015; Cook et al. 2018). In dental research this is no exception, as journal requirements to implement CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) improved methodological quality, despite some methodological concerns remained that may threaten RoB (Pandis et al. 2014; Leow et al. 2016; Papageorgiou et al. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate and compare the outcomes of bias assessments using both the original RoB tool and RoB2 in a sample of dental and oral research trials. By exploring the level of agreement between these tools, we seek to inform researchers and systematic reviewers of the potential impact of continued reliance on the original RoB tool, highlighting the importance of adopting ROB2 as the standard for bias assessment in dental research.Bias in research can originate from multiple sources, including selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, and reporting bias (Santaguida et al. 2012). This is essential when conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses, as these processes can significantly influence the synthesis of evidence and subsequent decision-making procedures(Santaguida et al. 2012). The proposed study aims to assess RoB and RoB2 results in a sample of trials of Dental and Oral Research and comparing it agreement results. These results may be informative for readers, particularly those who perform systematic reviews. The assessment of risk of bias (RoB) is fundamental to evidence-based research, ensuring the methodological rigor of studies and identifying flaws that could skew the true effect of an intervention (Leow et al. 2016; Papageorgiou et al. 2019; Ortiz et al. 2021; Limones et al. 2022 Sep 12). Recognizing the limitations of the original RoB tool, the Cochrane Collaboration introduced the Revised Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (RoB2) in 2019 as an evolution aimed at improving the accuracy and comprehensiveness of bias assessment (Papageorgiou et al. 2019). RoB2 addresses previous shortcomings by focusing on five key domains: bias due to the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, outcome measurement, and the selection of reported outcomes (Papageorgiou et al. 2019). This refined approach was designed to set a new gold standard for bias assessment, offering a more detailed and structured evaluation process.

2. Materials and Methods

In this meta-research study we assessed a sample of randomly included trials against the first (Higgins et al. 2011) and second versions of Cochrane risk of bias (ROB) tools.

2.1. Studies search and eligibility criteria

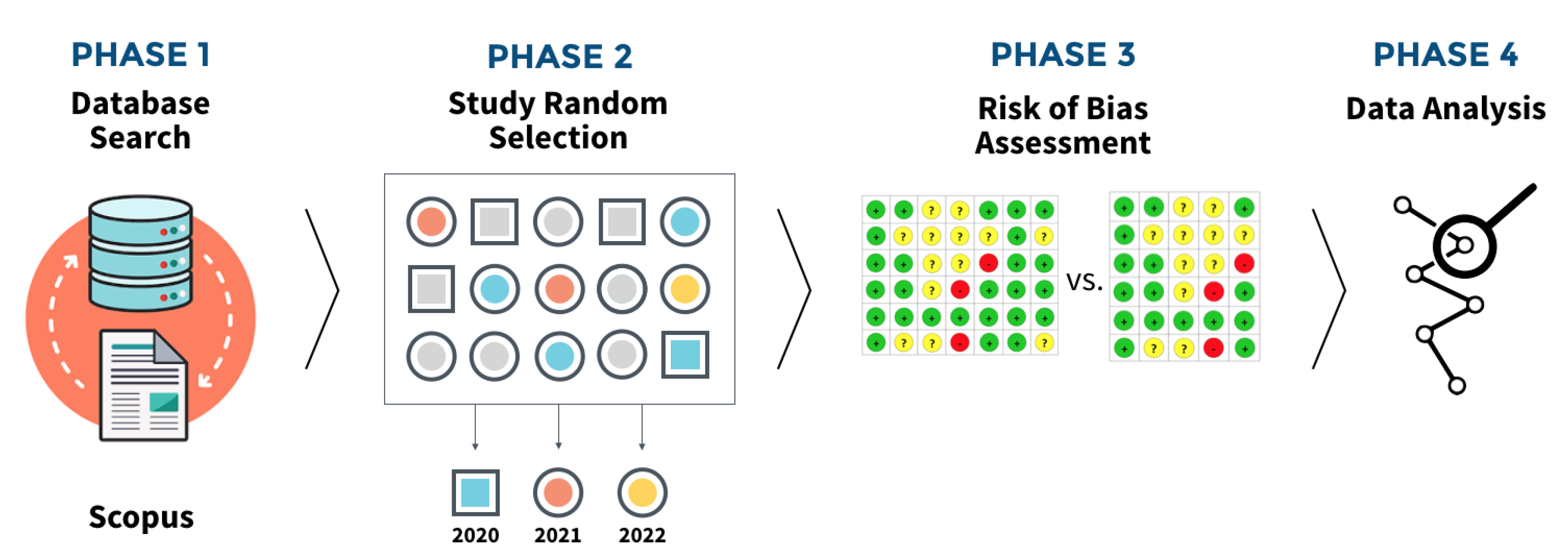

To be included in the final sample, studies had to be: classified as randomised clinical trials where only the sample was carried out in vivo; conducted in the field of oral/dental research; and whose publication was after the release of the RoB2, 28 August 2019. Considering a period of adaptation and indirect impact on trial reporting, we established a publication year period between 2020 and 2022 were included. This project began mid 2023, thus establishing the last complete year as temporal limit for trials search and inclusion. We structured this study in four distinct stages (

Figure 1). First, the databases PubMed/Medline, Scopus and EMBASE were searched with controlled and free keywords to identify applied randomized clinical trials. The studies carried out were included without language restrictions. The syntax used to search trials was as follows and adapted accordingly: (oral OR dental) AND (intervention* OR treatment* or therapeutic*) AND ("randomized controlled trial" OR "randomized clinical trial").

2.2. Studies Random Sampling Method

The raw dataset of studies that met the eligibility criteria was extracted and imported to Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet (v.16.35, Microsoft, Boston, MA, USA). To ensure a representative and unbiased sample, we randomly selected 50 studies for each year (2020, 2021, and 2022) using Microsoft Excel’s random function (‘=RAND()’) to generate a random number for each study. Following this, per year, we sorted the entire dataset by the random number column in descending order. By selecting the top 50 studies from this sorted list for each year, we ensured that our sample was random and free from any systematic selection biases. If a study did not meet the eligibility criteria, the next study in the order was included, until the estimated sample of studies was achieved.

2.3. Risk of bias assessment

Two examiners, J.V. and J.B., carried out the risk of bias assessment simultaneously in the same environment. This procedure was adopted to ensure a more rigorous and detailed analysis of possible biases that could affect the results of the study in question. The presence of both examiners in the same place allowed for direct and immediate interaction, facilitating the exchange of opinions and discussion of any points of divergence. When they found discrepancies in their assessments, the examiners resorted to a structured conflict resolution method: consulting a third reviewer (V.M.). This third reviewer acted as a mediator and his intervention was essential to guarantee the impartiality and accuracy of the final assessment. The need for consensus reflects the importance attached to objectivity and reliability in the process of assessing the risk of bias. The approach adopted, involving multiple assessors and a clear mechanism for resolving disagreements, reinforces the integrity of the review process. This method ensures that decisions are not one-sided and that different perspectives are considered, promoting a more balanced and comprehensive analysis. Following the instructions of both instruments we applied ROB (Higgins et al. 2011) and RoB2 [

14] of Cochrane risk of bias (RoB) tools using supported by the online full guidance document ([CSL STYLE ERROR: reference with no printed form.]). The first version of RoB has 7 domains: Random Sequence Generation; Allocation concealment; Blinding of participants and personel; Blinding of assessment outcome; Incomplete outcome data; Selective reporting; and, Other bias. RoB2 has 5 domains: Randomisation Process; Deviations from the Intended Intervention; Missing outcome data; Measurement of the outcome; and, Selection of the reported result.

2.4. Bibliometric Data and Reporting Guideline Adherence

Descriptive data from included studies, including authors, publication year, journal quartile ranking, journal impact factor ranking, via the Journal Citation Reports Clarivate (via

https://jcr.clarivate.com/jcr/browse-journals) ([CSL STYLE ERROR: reference with no printed form.]). Journal quartiles were used as a proxy of impact factor within its field or research. We also explored if a reporting guideline had been used, whether Data was available, which study design was present (Parallel, Split-mouth, cross-over or other) and whether a sample calculation was carried out

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Cohen’s weighted kappa coefficient was used to assess the measure of agreement between RoB and ROB2 classification. To categorize trials based on the journal impact factor, we calculated the median (3.4) and determined <3.4 (coded as 0) and 3.4 or higher (coded as 1). The weighted kappa coefficient was calculated using the 'irr' package in R, comparing the classifications of RoB and RoB2 for each observation with appropriate weighting based on the degree of disagreement. The resulting coefficient provides insight into the extent of agreement between the two classifications, ranging from -1 (indicating perfect disagreement) to 1 (indicating perfect agreement), with 0 suggesting agreement equivalent to chance. Furthermore, visualization of the RoB and RoB2 classifications was enhanced using the 'ggplot2' and 'ggalluvial' packages in R. Alluvial diagrams were created to illustrate the flow of data between different levels of risk of bias, providing a clear and intuitive representation of the classification process. The final images were refined and polished using Keynote on macOS.

3. Results

3.1. Trials Characteristics

From a total of 150 trials, 73.3% were published in Q1 and Q2 journals (n=52 and n=58, respectively), 22.7% in Q3 and Q4 journals (n= 22 and n=12, respectively), while 4% had no quartile attributed (n=6). When stating the use of a reporting guideline, only 51.3% expressed reporting the study following the CONSORT statement (n=77), while the remaining did not follow a reporting guideline. Concerning the type of trial design, most studies applied a parallel-arm design (74.7%, n=112), followed cross-over studies 11.3% (n=17) and split-mouth 14% (n=21). Of the total sample, the vast majority didn't provide information on dates, with only 30% (n=45) articles providing this information. The sample size was not calculated in 8.7% (n=13) articles.

3.2. RoB Instruments Comparison

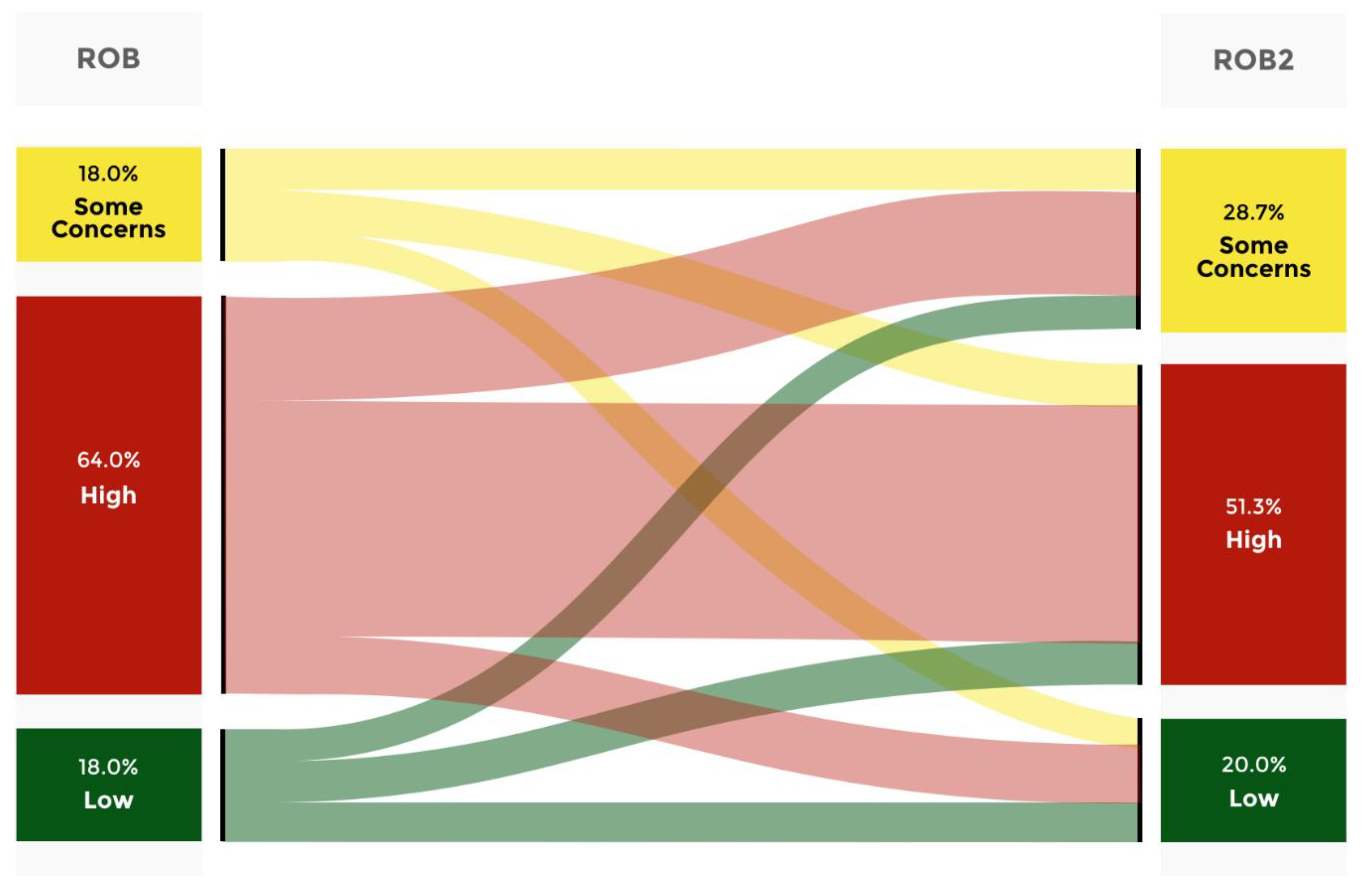

When examining the accordance between ROB and ROB2, it was observed that approximately 33.3% of the articles simultaneously categorized as Low risk of bias through both analyses were in agreement (

Figure 1). Additionally, it was noted that 29.6% of the articles classified as Low risk of bias through the RoB analysis were downgraded to Some concerns through the RoB2 analysis. Moreover, it was revealed that 37% of the cases classified as Low risk of bias through the initial assessment tool were downgraded to High risk of bias by the most recent RoB. Furthermore, when analyzing the Some concerns category, it was found that 25.9% of the cases were upgraded to Low. In 37% of the cases, the analysis remained constant with RoB2. Additionally, it was found that 37% of the cases were downgraded to High risk of bias. Moreover, when analyzing the articles classified as High risk of bias using RoB, it was observed that 14.6% of the articles were upgraded to a Low risk of bias with the latest evaluation tool. In 26% of the cases, there was an upgrade to some concerns, and in 59.4% of the cases, it remained with High risk of bias in both instruments. The same analysis was carried out for each Quartile category and for journal without Quartile attribution.

3.3. Variables associated RoB agreement

The results presented in

Table 2 demonstrated a higher level of agreement in the RoB outcomes when assessed using the CONSORT guidelines (κ = 0.225, 95% CI: 0.046-0.405). However, when examining whether a sample calculation was performed, it was found that among studies that did not perform this calculation, there was a higher level of agreement (κ = 0.261, 95% CI: -0.027; 0.548). With regard to the type of study, a greater degree of agreement was observed in studies that utilized the parallel model (κ = 0.221, 95% CI: 0.070; 0.372), but studies employing a split-mouth (κ = 0.016, 95% CI: -0.327; 0.358) or a cross-over (κ = 0.056, 95% CI: -0.369; 0.480) design revealed the lowest level of agreement. In terms of the quartile categorization of journal types, a higher level of agreement was observed in journals classified as quartile 4 (κ = 0.464, 95% CI: -0.040; 0.969). Finally, it appears that the impact factor had no bearing on the level of agreement between the two journals, with the lower-ranked journal having an impact factor of 3.4.

4. Discussion

Discussion In this study, we examined the level of agreement between the original and updated versions of the Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB) tool in the context of dental and oral research trials. Our analysis revealed a notable discrepancy in the agreement between these two versions, indicating potential challenges in the assessment of bias across studies in this field. These findings underscore the importance of critically evaluating methodological tools and their application in systematic reviews, particularly within specialized domains such as dental and oral research. In this discussion, we delve deeper into the implications of our findings, exploring potential factors contributing to the observed discordance and suggesting avenues for future research and methodological refinement. Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) are considered the gold standard in scientific research, especially in areas such as dentistry (Kahan et al. 2015; Clyne et al. 2020). These studies are designed to assess the effectiveness of clinical interventions in a rigorous and unbiased way (Turner et al. 2012; Kahan et al. 2015). One of the main concerns in RCTs is the risk of bias, which can jeopardise the validity of the results (Zhai et al. 2015). To address this issue, risk of bias assessment instruments are used, such as RoB (Risk Of Bias) and RoB2 (a more recent and updated version). These instruments were developed to provide a structured and standardised assessment of the risk of bias in clinical trials. In dentistry, RCTs are widely used to evaluate the effectiveness of different treatments and interventions, such as restorative materials, surgical techniques, preventive approaches, orthodontic therapies and periodontal treatments. The application of the RoB and RoB2 instruments in these studies helps to ensure that the results are reliable and valid (Rutterford et al. 2015; Hays et al. 2016; Goldacre et al. 2019). Clinical procedures in Dental and Oral Research can vary significantly, not only between different types of treatment, but also in the way they are carried out by different professionals. In the surgical Techniques, different dental surgeons may adopt variations in tooth extraction or implant techniques, which can introduce variability that is not fully captured by the RoB or RoB2 criteria. In restorative materials, the choice and application of restorative materials can vary depending on the dentist, the patient, and the specific conditions of the tooth, introducing variability that is difficult to standardize and fully assess. Regarding to dental aesthetics, evaluations of aesthetic results are often subjective and can vary between patients and evaluators. Concerning pain and comfort measures of post-operative pain and comfort are highly subjective and can be influenced by personal and psychological factors that are difficult to control and assess consistently. In view of this, we believe that the RoB tool needs to be adapted for dentistry, as this causes many of the published studies to present a false idea of low risk of bias, when in reality they have some concerns or high risk of bias. Adapting the tool is crucial to ensure a more accurate and rigorous assessment of dental studies. The current criteria of the RoB tool may not adequately capture the specificities and nuances of dental research, leading to an underestimation of the risk of bias. This is particularly worrying as clinical decisions and health policies can be based on scientifically compromised evidence. Furthermore, correctly identifying the risks of bias allows researchers and health professionals to recognise the limitations of studies and make more informed decisions. With an adapted tool, it is hoped that there will be an improvement in the quality of publications and, consequently, in clinical practice. Our analysis highlights a substantial number of articles that were either downgraded or upgraded. This poses serious challenges to scientific integrity and evaluation criteria, as downgrading suggests methodological flaws and inadequate tools that fail to capture study nuances and bias risks, potentially disseminating inaccurate information. Conversely, upgrading implies undervaluation of research due to inconsistent evaluation criteria, hindering scientific progress and practical application. Comparing the original tool (RoB) and its updated version (RoB2) reveals critical implications for scientific integrity and evaluation standards. The significant proportion of articles either downgraded or upgraded emphasizes the inherent challenges in the evolution of assessment methodologies. The transition to RoB2 highlights discrepancies and inconsistencies in the evaluation process, revealing instances where valuable research may have been disregarded or underestimated. This situation not only hampers scientific progress by neglecting potentially impactful findings but also impedes their practical application in clinical settings or policy formulation. In essence, the comparison between RoB and RoB2 underscores the dynamic nature of scientific evaluation and the ongoing quest for more robust and nuanced assessment methodologies. While the transition to updated tools like RoB2 represents progress towards more accurate and comprehensive evaluations, it also prompts a critical reevaluation of past research assessments and their implications for the broader scientific community. Strengths and Limitations This is simultaneity crucial for our research, as it allows for a more consistent and reliable assessment of the risk of bias in the publications analysed. The simultaneous existence of the two versions of the RoB offers a unique opportunity to compare and validate the methods for assessing the risk of bias. RoB, the original version, and RoB 2, the updated version, have methodological differences that can impact the analysis of the data. By focusing on the period when both versions were in use, we reduced the heterogeneity in the application of the assessment tools, which is fundamental to guaranteeing the integrity and comparability of the results. Furthermore, by limiting the study to these years, we mitigated potential biases that could arise from changes in research practices or publication guidelines that occurred outside of this interval. Significant changes in bias assessment guidelines could introduce unwanted variability into the results, making it difficult to accurately interpret the data.

Future perspectives

With these results, there is a need for a deeper understanding of how trial design characteristics influence the discrepancy between the two versions of the RoB tool. Secondly, considering the influence of journal ranking on the agreement between RoB versions suggests the importance of journal policies and editorial practices in ensuring methodological rigor and transparency in published research. Collaborative efforts between journals and research communities to uphold reporting guidelines and promote adherence to methodological standards can enhance the reliability and consistency of bias assessments across studies. Furthermore, exploring the factors that contribute to discrepancies in risk of bias assessments can inform the refinement of reporting guidelines and methodological standards specific to dental and oral research. Tailoring guidelines to address unique challenges and considerations in this field may improve the comparability and reliability of bias assessments between RoB versions

5. Conclusions

The level of agreement between the first and second version of Cochrane RoB tool was low in trials of dental and oral research. This level of agreement seems to be influenced by trial design, journal ranking and the adherence to reporting guidelines. Future efforts shall be made to strengthen the quality of trials, to uphold reporting guidelines and promote adherence to methodological standards.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.V, J.B and V.M.; methodology, J.V, J.B, V.M, C.L, P.L and M.J.; software, J.V, J.B and P.L.; validation, J.V, J.B, V.M, C.L, P.L and M.J.; formal analysis J.V, J.B and V.M.; investigation, J.V, J.B, V.M, C.L, P.L and M.J.; resources, J.V, J.B and P.L.; data curation, , J.V, J.B and P.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.V, J.B, P.L and V.M.; writing—review and editing, J.V, J.B, V.M, C.L, P.L and M.J.; visualization, J.V, J.B, V.M, C.L, P.L and M.J.; supervision, J.V and J.B; project administration, J.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

: Asbjørn Hróbjartsson: Contributed to conception, design, data acquisition and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CONSORT |

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials |

| NA |

Not attributed |

| Q1 |

Quartile 1 |

| Q2 |

Quartile 2 |

| Q3 |

Quartile 3 |

| Q4 |

Quartile 4 |

| RCT |

Randomized controlled trial |

| RCTS |

Randomized controlled trials |

| ROB |

Risk of Bias |

| ROB2 |

Risk of Bias 2 |

References

- Cioffi I, Farella M. 2011. Quality of randomised controlled trials in dentistry. Int Dent J. 61(1):37–42.

- Clyne B, Boland F, Murphy N, Murphy E, Moriarty F, Barry A, Wallace E, Devine T, Smith SM, Devane D, et al. 2020. Quality, scope and reporting standards of randomised controlled trials in Irish Health Research: an observational study. Trials. 21(1):494.

- Cook C, Checketts JX, Atakpo P, Nelson N, Vassar M. 2018. How well are reporting guidelines and trial registration used by dermatology journals to limit bias? A meta-epidemiological study. Br J Dermatol. 178(6):1433–1434.

- De Bruin M, McCambridge J, Prins JM. 2015. Reducing the risk of bias in health behaviour change trials: Improving trial design, reporting or bias assessment criteria? A review and case study. Psychol Health. 30(1):8–34.

- Faggion, CM. 2016. The rationale for rating risk of bias should be fully reported. J Clin Epidemiol. 76:238.

- Goldacre B, Drysdale H, Dale A, Milosevic I, Slade E, Hartley P, Marston C, Powell-Smith A, Heneghan C, Mahtani KR. 2019. COMPare: a prospective cohort study correcting and monitoring 58 misreported trials in real time. Trials. 20(1):118.

- Hays M, Andrews M, Wilson R, Callender D, O’Malley PG, Douglas K. 2016. Reporting quality of randomised controlled trial abstracts among high-impact general medical journals: a review and analysis. BMJ Open. 6(7):e011082.

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JAC, et al. 2011. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 343(oct18 2):d5928–d5928.

- Journal Citation Reports - Journals. [accessed 2024a Jun 5]. https://jcr.clarivate.com/jcr/browse-journals.

- Kahan BC, Rehal S, Cro S. 2015. Risk of selection bias in randomised trials. Trials. 16(1):405.

- Leow NM, Hussain Z, Petrie A, Donos N, Needleman IG. 2016. Has the quality of reporting in periodontology changed in 14 years? A systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 43(10):833–838.

- Limones A, Celemín-Viñuela A, Romeo-Rubio M, Castillo-Oyagüe R, Gómez-Polo M, Martínez Vázquez de Parga JA. 2022 Sep 12. Outcome measurements and quality of randomized controlled clinical trials of tooth-supported fixed dental prostheses: A systematic review and qualitative analysis. J Prosthet Dent.:S0022-3913(22)00282–7.

- Moon K, Rao S. 2021. Assessment of the Risk of Bias. In: Patole S, editor. Principles and Practice of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis. Cham: Springer International Publishing. p. 43–55. [accessed 2024 Jun 5]. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-71921-0_4.

- Ortiz MIG, Ribeiro MES, Lima DANL, Silva CM, Loretto SC, da Silva E Souza Júnior MH. 2021. Compliance of randomized clinical trials on dental caries prevention methods with the consort statement: a systematic review. J Evid-Based Dent Pract. 21(2):101542.

- Pandis N, Shamseer L, Kokich VG, Fleming PS, Moher D. 2014. Active implementation strategy of CONSORT adherence by a dental specialty journal improved randomized clinical trial reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 67(9):1044–1048.

- Papageorgiou SN, Antonoglou GN, Martin C, Eliades T. 2019. Methods, transparency and reporting of clinical trials in orthodontics and periodontics. J Orthod. 46(2):101–109.

- Risk of bias tools - Current version of RoB 2. [accessed 2024b Jun 5]. https://www.riskofbias.info/welcome/rob-2-0-tool/current-version-of-rob-2.

- Rutterford C, Taljaard M, Dixon S, Copas A, Eldridge S. 2015. Reporting and methodological quality of sample size calculations in cluster randomized trials could be improved: a review. J Clin Epidemiol. 68(6):716–723.

- Saltaji H, Armijo-Olivo S, Cummings GG, Amin M, Flores-Mir C. 2017. Randomized clinical trials in dentistry: Risks of bias, risks of random errors, reporting quality, and methodologic quality over the years 1955–2013. Gluud C, editor. PLOS ONE. 12(12):e0190089.

- Santaguida PL, Riley CM, Matchar DB. 2012. Chapter 5: Assessing Risk of Bias as a Domain of Quality in Medical Test Studies. J Gen Intern Med. 27(S1):33–38.

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng H-Y, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, et al. 2019. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 366:l4898.

- Turner L, Shamseer L, Altman DG, Weeks L, Peters J, Kober T, Dias S, Schulz KF, Plint AC, Moher D. 2012. Consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) and the completeness of reporting of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published in medical journals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 11(11):MR000030.

- Zhai X, Wang Y, Mu Q, Chen X, Huang Q, Wang Q, Li M. 2015. Methodological Reporting Quality of Randomized Controlled Trials in 3 Leading Diabetes Journals From 2011 to 2013 Following CONSORT Statement: A System Review. Medicine (Baltimore). 94(27):e1083.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).