Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analysis of Pseudomonas spp. Using the AppIndels Server

3. Results

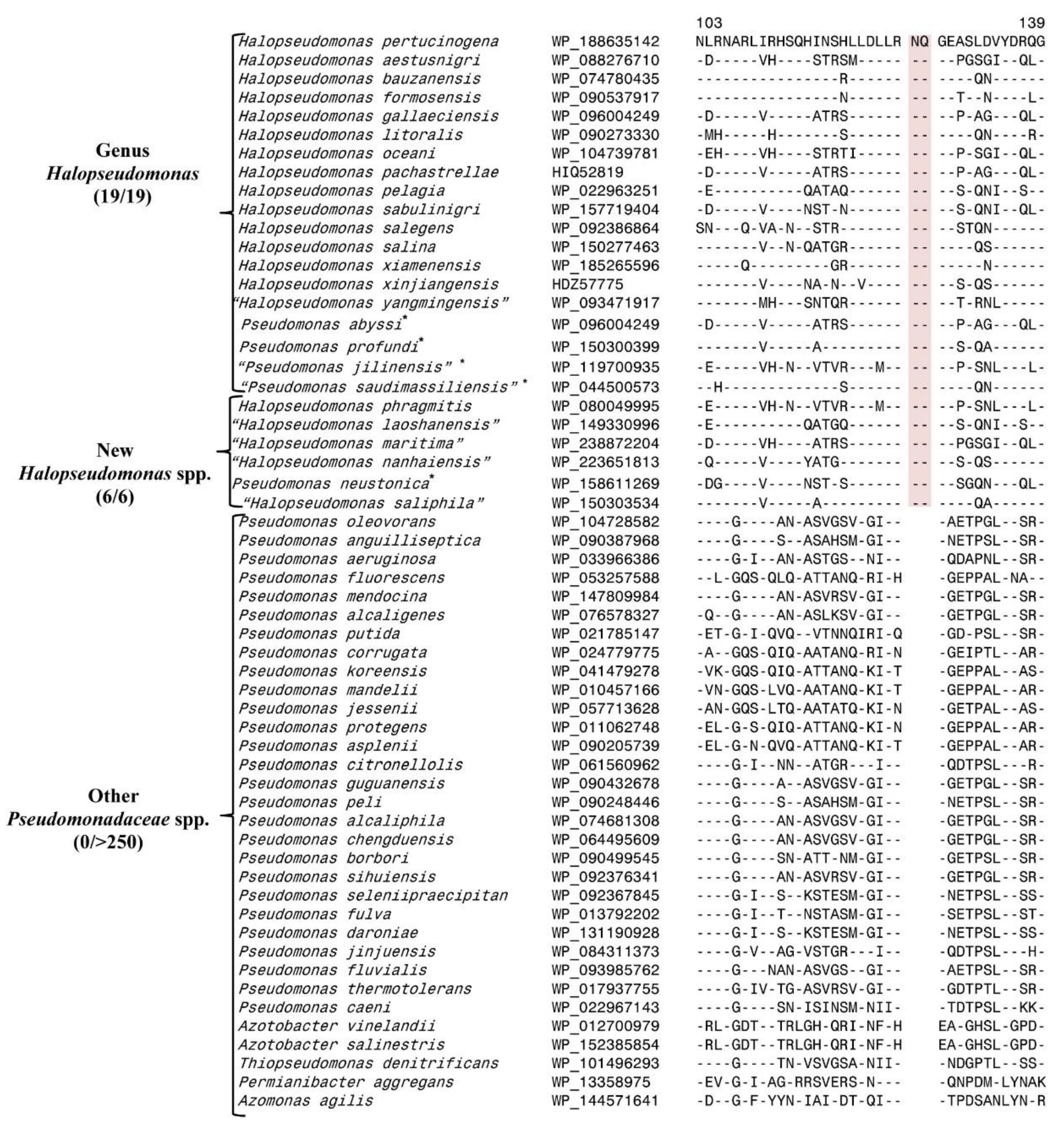

3.1. Predictive Ability of a CSI Specific for the Genus Halopseudomonas

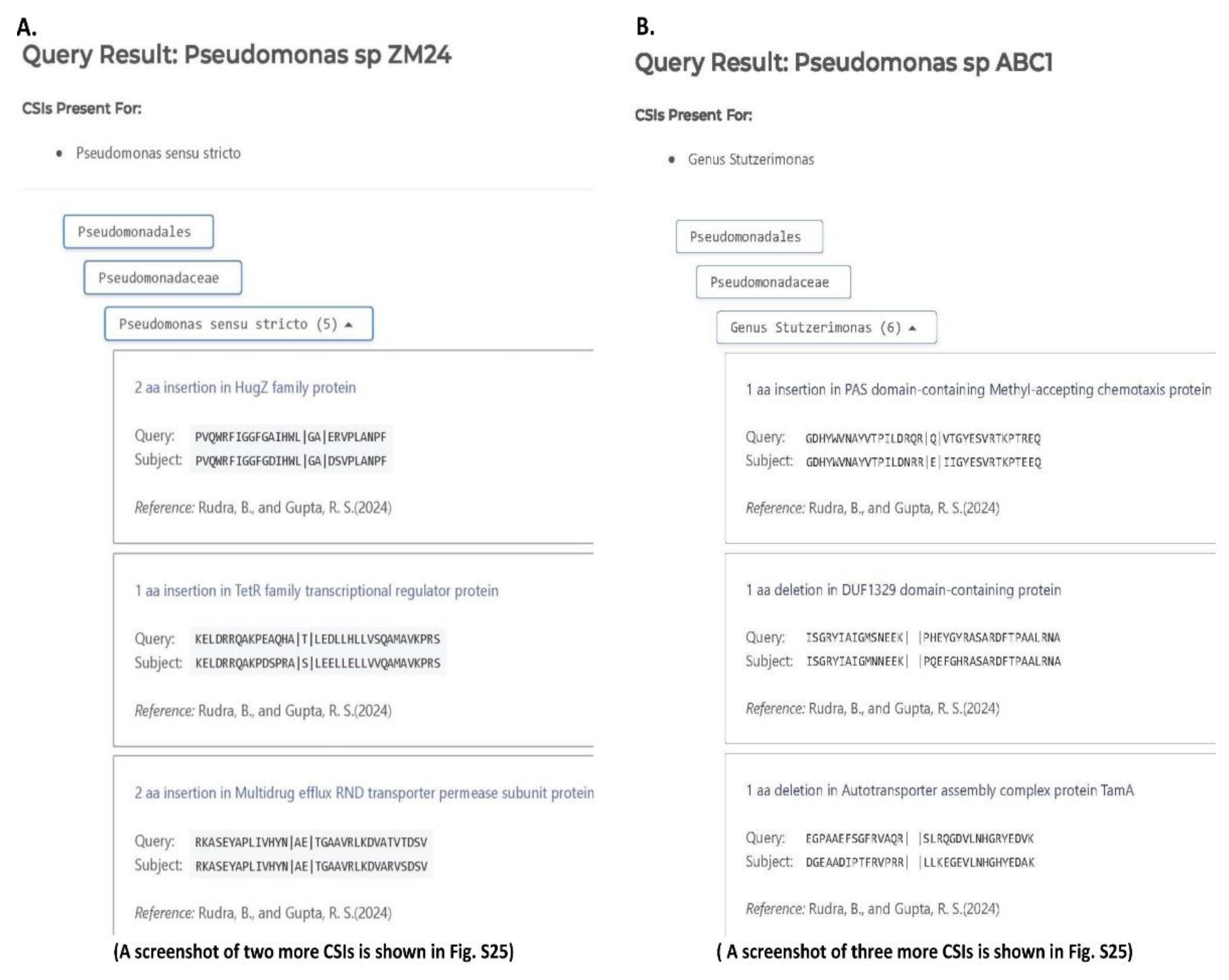

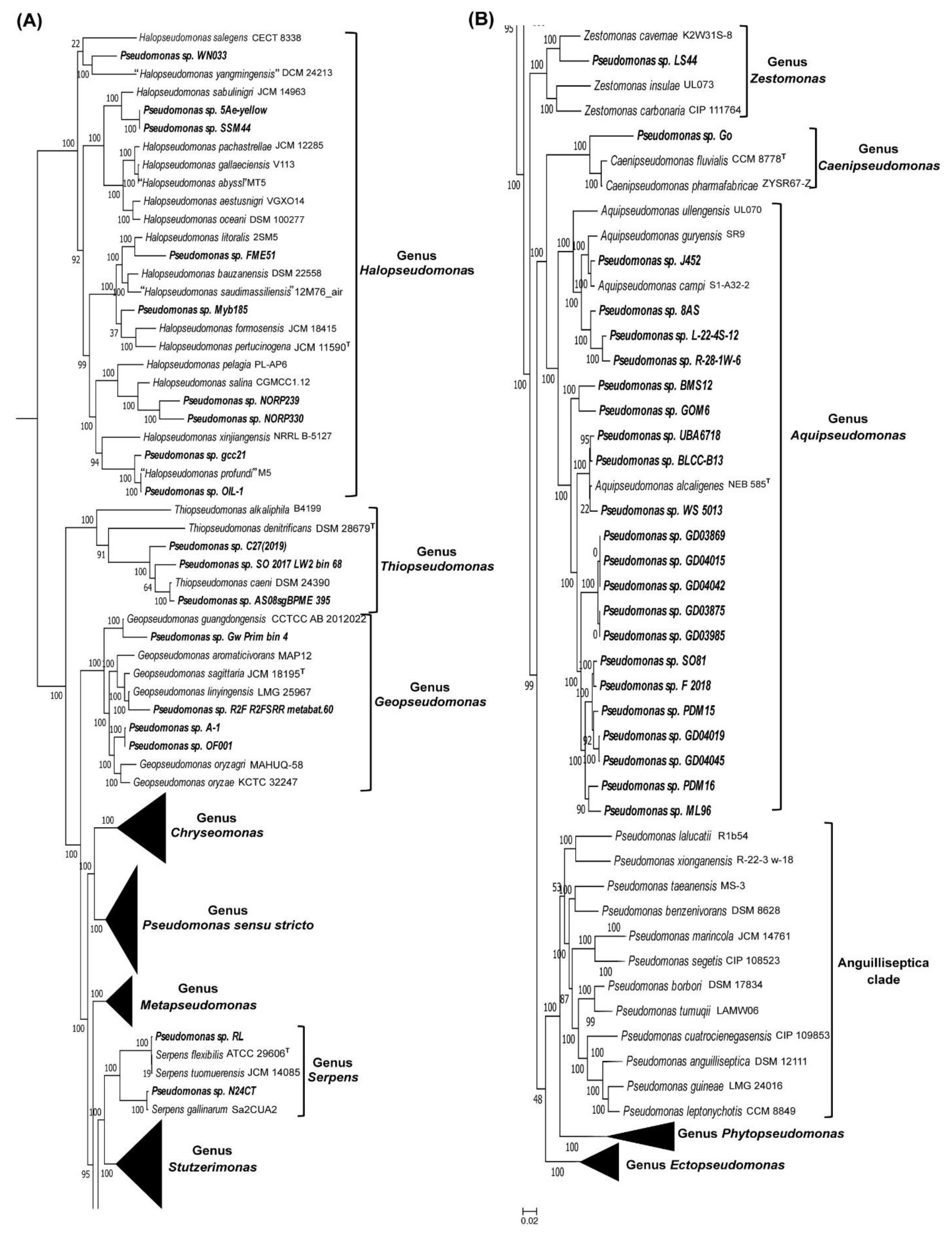

3.2. Examining the Usefulness of the CSIs Specific for the Pseudomonadaceae Genera for Determining the Taxonomic Affiliation of Unclassified Pseudomonas spp. Using the AppIndels.com Server

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Migula W. Uber ein neues System der Bakterien. Arb. Bakt. Inst. Kar1sruhe 1894;1(235):238.

- Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved lists of bacterial names. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980;30:225-420.

- Jun SR, Wassenaar TM, Nookaew I, Hauser L, Wanchai V et al. Diversity of Pseudomonas Genomes, Including Populus-Associated Isolates, as Revealed by Comparative Genome Analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol 2016;82(1):375-383.

- Lalucat J, Gomila M, Mulet M, Zaruma A, Garcia-Valdes E. Past, present and future of the boundaries of the Pseudomonas genus: Proposal of Stutzerimonas gen. Nov. Syst Appl Microbiol 2022;45(1):126289. [CrossRef]

- Rudra B, Gupta RS. Phylogenomic and comparative genomic analyses of species of the family Pseudomonadaceae: Proposals for the genera Halopseudomonas gen. nov. and Atopomonas gen. nov., merger of the genus Oblitimonas with the genus Thiopseudomonas, and transfer of some misclassified species of the genus Pseudomonas into other genera. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2021;71(9):005011. [CrossRef]

- Saati-Santamaria Z, Peral-Aranega E, Velazquez E, Rivas R, Garcia-Fraile P. Phylogenomic Analyses of the Genus Pseudomonas Lead to the Rearrangement of Several Species and the Definition of New Genera. Biology (Basel) 2021;10(8). [CrossRef]

- Hesse C, Schulz F, Bull CT, Shaffer BT, Yan Q et al. Genome-based evolutionary history of Pseudomonas spp. Environ Microbiol 2018;20(6):2142-2159.

- Gomila M, Pena A, Mulet M, Lalucat J, Garcia-Valdes E. Phylogenomics and systematics in Pseudomonas. Front Microbiol 2016;6:214. [CrossRef]

- Peix A, Ramirez-Bahena MH, Velazquez E. The current status on the taxonomy of Pseudomonas revisited: An update. Infect Genet. Evol 2018;57:106-116. [CrossRef]

- Peix A, M.H. R-B, Velázquez E. Historical evolution and current status of the taxonomy of genus Pseudomonas. Infect Genet. Evol 2009;9:1132-1147. [CrossRef]

- Rudra B, Gupta RS. Phylogenomics studies and molecular markers reliably demarcate genus Pseudomonas sensu stricto and twelve other Pseudomonadaceae species clades representing novel and emended genera. Frontiers in Microbiology 2024;14:1273665. [CrossRef]

- Oren A, Arahal DR, Goker M, Moore ERB, Rossello-Mora R et al. International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes. Prokaryotic Code (2022 Revision). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2023;73(5a).

- Lalucat J, Mulet M, Gomila M, Garcia-Valdes E. Genomics in Bacterial Taxonomy: Impact on the Genus Pseudomonas. Genes (Basel) 2020;11:139. [CrossRef]

- Girard L, Lood C, Hofte M, Vandamme P, Rokni-Zadeh H et al. The Ever-Expanding Pseudomonas Genus: Description of 43 New Species and Partition of the Pseudomonas putida Group. Microorganisms 2021;9(8). [CrossRef]

- Passarelli-Araujo H, Franco GR, Venancio TM. Network analysis of ten thousand genomes shed light on Pseudomonas diversity and classification. Microbiol Res 2022;254:126919. [CrossRef]

- Adeolu M, Alnajar S, Naushad S, Gupta S. Genome-based phylogeny and taxonomy of the ’Enterobacteriales’: proposal for Enterobacterales ord. nov. divided into the families Enterobacteriaceae, Erwiniaceae fam. nov., Pectobacteriaceae fam. nov., Yersiniaceae fam. nov., Hafniaceae fam. nov., Morganellaceae fam. nov., and Budviciaceae fam. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2016;66(12):5575-5599.

- Gupta RS. Identification of conserved indels that are useful for classification and evolutionary studies. Methods Microbiol 2014;41:153-182.

- Gupta RS. Impact of genomics on the understanding of microbial evolution and classification: the importance of Darwin’s views on classification. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2016;40(4):520-553. [CrossRef]

- Gupta RS, Chander P, George S. Phylogenetic framework and molecular signatures for the class Chloroflexi and its different clades; proposal for division of the class Chloroflexia class. nov. [corrected] into the suborder Chloroflexineae subord. nov., consisting of the emended family Oscillochloridaceae and the family Chloroflexaceae fam. nov., and the suborder Roseiflexineae subord. nov., containing the family Roseiflexaceae fam. nov. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2013;103(1):99-119.

- Gupta RS, Patel S, Saini N, Chen S. Robust demarcation of 17 distinct Bacillus species clades, proposed as novel Bacillaceae genera, by phylogenomics and comparative genomic analyses: description of Robertmurraya kyonggiensis sp. nov. and proposal for an emended genus Bacillus limiting it only to the members of the Subtilis and Cereus clades of species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2020;70:5753-5798. [CrossRef]

- Holmes B, Steigerwalt A, Weaver R, Brenner DJ. Chryseomonas polytricha gen. nov., sp. nov., a Pseudomonas-like organism from human clinical specimens and formerly known as group Ve-1. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 1986;36(2):161-165. [CrossRef]

- Hespell RB. Serpens flexibilis gen. nov., sp. nov., an unusually flexible, lactate-oxidizing bacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 1977;27(4):371-381.

- Palleroni NJ. Pseudomonas. John Wiley and Sons in Association with Bergey’s Manual Trust; 2015. pp. 1-105.

- Rossi E, La Rosa R, Bartell JA, Marvig RL, Haagensen JAJ et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa adaptation and evolution in patients with cystic fibrosis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021;19(5):331-342. [CrossRef]

- Lund-Palau H, Turnbull AR, Bush A, Bardin E, Cameron L et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis: pathophysiological mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Expert. Rev. Respir. Med 2016;10:685-697.

- Parte AC, Sarda Carbasse J, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Reimer LC, Goker M. List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) moves to the DSMZ. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2020;70(11):5607-5612. [CrossRef]

- Gupta RS, Eivin DA. AppIndels.com Server: A Web Based Tool for the Identification of Known Taxon-Specific Conserved Signature Indels in Genome Sequences: Validation of Its Usefulness by Predicting the Taxonomic Affiliation of >700 Unclassified strains of Bacillus Species. Int J Syst and Evol Microbiol 2023;73::005844.

- Wang Z, Wu M. A phylum-level bacterial phylogenetic marker database. Mol. Biol. Evol 2013;30(6):1258-1262. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, Rudra B, Gupta RS. Phylogenomics and molecular signatures support division of the order Neisseriales into emended families Neisseriaceae and Chromobacteriaceae and three new families Aquaspirillaceae fam. nov., Chitinibacteraceae fam. nov., and Leeiaceae fam. nov. Syst Appl Microbiol 2021;44(6):126251.

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol 2018;35(6):1547-1549. [CrossRef]

- Girard L, Lood C, De Mot R, van Noort V, Baudart J. Genomic diversity and metabolic potential of marine Pseudomonadaceae. Front Microbiol 2023;14:1071039. [CrossRef]

- Kujur RRA, Ghosh M, Basak S, Das SK. Phylogeny and structural insights of lipase from Halopseudomonas maritima sp. nov., isolated from sea sand. Int Microbiol 2023;26(4):1021-1031. [CrossRef]

- Winsor GL, Griffiths EJ, Lo R, Dhillon BK, Shay JA et al. Enhanced annotations and features for comparing thousands of Pseudomonas genomes in the Pseudomonas genome database. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44:D646-D653. [CrossRef]

- Xin XF, Kvitko B, He SY. Pseudomonas syringae: what it takes to be a pathogen. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 2018;16:316-328. [CrossRef]

- Palleroni NJ. Genus I. Pseudomonas Migula 1894. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology (The Proteobacteria), part B (The Gammaproteobacteria), 2nd edn,. Edited by D. J. Brenner, N. R. Krieg, James T. Staley & G. M. Garrity. New York: Springer 2005;2:323-379.

- Stover CK, Pham XQ, Erwin A, Mizoguchi S, Warrener P et al. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 2000;406(6799):959-964. [CrossRef]

- Planquette B, Timsit J-F, Misset BY, Schwebel C, Azoulay E et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia. predictive factors of treatment failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;188(1):69-76.

- Duman M, Mulet M, Altun S, Saticioglu IB, Gomila M et al. Corrigendum: Pseudomonas piscium sp. nov., Pseudomonas pisciculturae sp. nov., Pseudomonas mucoides sp. nov. and Pseudomonas neuropathica sp. nov. isolated from rainbow trout. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2021;71(12).

- Sayers EW, Agarwala R, Bolton EE, Brister JR, Canese K et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res 2019;47(D1):D23-D28. [CrossRef]

- Khadka B, Persaud D, Gupta RS. Novel Sequence Feature of SecA Translocase Protein Unique to the Thermophilic Bacteria: Bioinformatics Analyses to Investigate Their Potential Roles. Microorganisms 2020;8:59. [CrossRef]

- Singh B, Gupta RS. Conserved inserts in the Hsp60 (GroEL) and Hsp70 (DnaK) proteins are essential for cellular growth. Mol. Genet. Genomics 2009;281:361-373. [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto K, Panchenko AR. Mechanisms of protein oligomerization, the critical role of insertions and deletions in maintaining different oligomeric states. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010;107(47):20352-20357. [CrossRef]

- Miton CM, Tokuriki N. Insertions and deletions (indels): a missing piece of the protein engineering jigsaw. Biochemistry 2022;62(2):148-157. [CrossRef]

- Khadka B, Gupta RS. Identification of a conserved 8 aa insert in the PIP5K protein in the Saccharomycetaceae family of fungi and the molecular dynamics simulations and structural analysis to investigate its potential functional role. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 2017;85(8):1454-1467. [CrossRef]

| Genera/Species name | No. of Identified CSIs | Weight Value for Each CSI |

|---|---|---|

| Aquipseudomonas | 6 | 0.4 |

| Atopomonas | 22 | 0.2 |

| Azomonas | 5 | 0.4 |

| Azotobacter | 10 | 0.4 |

| Caenipseudomonas | 8 | 0.4 |

| Chryseomonas | 11 | 0.3 |

| Ectopseudomonas | 5 | 0.4 |

| Geopseudomonas | 15 | 0.3 |

| Halopseudomonas | 24 | 0.2 |

| Metapseudomonas | 5 | 0.4 |

| Phytopseudomonas | 12 | 0.3 |

| Pseudomonas sensu stricto | 6 | 0.4 |

| Serpens | 3 | 0.5 |

| Stutzerimonas | 7 | 0.4 |

| Thiopseudomonas | 6 | 0.3 |

| Zestomonas | 5 | 0.4 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 7 | 0.3 |

| Pseudomonas paraeruginosa | 5 | 0.4 |

| Genera/Species | No. of strains | Range of CSIs | Pseudomonas Spp. strain Nos. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas sensu stricto | 46 | 5-6 | 21, 273, 30_B, AAC, ADPe, ATCC 13867, AU11447, AU12215, BJa5, EGD-AKN5, GCEP-101, GD03691, GD03903, GD04087, HMSC75E02, HS-18, LA21, M1, NBRC 111135, NBRC100443, PDM17, PDM18, PDM19, PDM20, PDM21, PDM22, PDM23, PDM33, PDNC002, PI1, PSE14, R3.Fl, RW407, SCB32, UMA601, UMA603, UMA643, UMC3103, UMC3106, UMC3129, UMC631, UMC76, UME83, ZM23, ZM24, ZM25. |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 64 | 5-7 | 203-8, 17023526, 17023671, 17033095, 17053182, 17053418, 17053703, 17063399, 17072548, 17073326, 17102422, 17103552, 17104299, 18073667, 18082547, 18081308, 18082551, 18082574, 18083194, 18083202, 18083259, 18083286, 18084127, 18092229, 18093371, 18101001-2, 18102011, 18103014, 18113298, 19062259, 19064969, 19072337-2, 19082381, 2VD, 3PA37B6, AF1, AFW1, AK6U, B111, BDPW, BIS, BIS1, CP-1, FDAARGOS_761, HMSC057H01, HMSC072F09, HMSC16B01, HMSC076A11, HMSC060F12, HMSC065H01, HMSC066A08, HMSC065H02, HMSC067G02, HMSC063H08, HMSC058C05, P179, P20, P22, PAH14, Pseudomonas_assembly, PS1(2021), RGIG3665, S33, S68. |

| Aquipseudomonas | 21 | 4-6 | 8AS, BLCC-B13, BMS12, F(2018), GD03869, GD03875, GD03985, GD04015, GD04019, GD04042, GD04045, GOM6, J452, L-22-4S-12, ML96, PDM15, PDM16, R-28-1W-6, UBA6718, SO81,WS 5013. |

| Caenipseudomonas | 1 | 7 | Go_SlPrim_bin_81 |

| Chryseomonas | 32 | 6-11 | 313, AS2.8, BAV 2493, BAV 4579, GM_Psu_1, GM_Psu_2, HUK17, LTJR-52, MAG002Y, PS02302, RIT 411, S1C77_SP397, S2C3242, SP152, SP29, SP3, SP403, SP421, WAC2, HPB0071, Snoq117.2, MS15, JUb52, EpSL25, PLB05, HR1, CBMAI 2609,UBA6549, UBA7233, UBA3149, UBA4102. |

| Ectopseudomonas | 46 | 3-5 | 297, 07-Jan, 905_Psudmo1, AA-38, ALS1131, ALS1279, AOB-7, B11D7D, BMW13, DS1.001, EGD-AK9, EggHat1, GD03721, GD03722, GD03919, GD04158, GOM7, GV_Bin_12, Gw_UH_bin_155, HS-2, KB-10, KHPS1, LPH1, Leaf83, MDMC17, MDMC216, MDMC224, MSPm1, Marseille-Q0931, NCCP-436, NFACC19-2, NFPP33, o96, OA3, P818, 8O, 8Z, REST10, RGIG627, THAF187a, THAF42, WS 5019, YY-1, Z8(2022), ZH-FAD, phDV1. |

| Geopseudomonas | 4 | 4-15 | A-1, OF001, R2F_R2FSRR_metabat.60, Gw_Prim_bin_4. |

| Halopseudomonas | 9 | 20-24 | 5Ae-yellow, FME51, MYb185, NORP239, NORP330, OIL-1, SSM44, WN033, gcc21. |

| Metapseudomonas | 22 | 3-5 | 57B-090624, 1D4, A46, BN102, BN411, BN414, BN415, BN417, BN515, BN606, D(2018), DY-1, ENNP23, FeS53a, JG-B, JM0905a, LFM046, PDM13, Pc102, Q1-7, SLBN-26, TCU-HL1. |

| Phytopseudomonas | 17 | 9-12 | AG1028, Bi70, BIGb0408, CrR14, CNPSo 3701, MEJ086, MM211, PDM11, PDM12, S2C11432_SP223, S2C78296_SP133, sia0905, SP200_1_metabat2_genome_mining.44, SP236_1_metabat2_genome_mining.8, PA1, PA15, PA27. |

| Serpens | 2 | 3 | N24CT, RL. |

| Stutzerimonas | 31 | 4-7 | 10B238, 9Ag, A192_concoct.bin.7, ABC1, ALOHA_A2.5_105, BAY1663, BRH_c35, C42_metabat.bin.8, Choline-3u-10, DF_1_3.23, DNDY-54, IC_126, JI-2, KSR10, M30B71, MCMED-G45, MT-1, MT4, MTM4, N17CT, NP21570, Q2-TVG4-2, RS261_metabat.bin.8, S5(2021), SCT, SST3, TTU2014-066ASC, TTU2014-096BSC, TTU2014-105ASC, WS 5018, s199. |

| Thiopseudomonas | 3 | 4-5 | AS08sgBPME_395, C27(2019), SO_2017_LW2 bin 68. |

| Zestomonas | 1 | 3 | LS44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).