Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder marked by socio-communicative deficits, repetitive and stereotyped behaviors, and restricted interests. The severity of each symptom lies along a spectrum, such that clinical presentation varies from patient to patient (Lord et al., 2020). Patients with ASD show other comorbidities, like motor problems and anxiety, among others (Lord et al., 2020). About 1 in 36 children born today are expected to receive an ASD diagnosis (Maenner et al., 2021), and an ASD diagnosis can exact a potentially heavy economic burden, estimated to be $3.6 million (Cakir et al., 2020). Because of the significant public health challenge posed by ASD, decades of preclinical research have sought to uncover effective therapeutic strategies (Gandal et al., 2016; Manoli and State, 2021; Sztainberg and Zoghbi, 2016). Unfortunately, this work has so far yielded few effective therapies, with the only existing pharmacological therapies treating symptoms, rather than core ASD traits (Aishworiya et al., 2022).

Still, this body of work has revealed features of ASD pathophysiology that merit further consideration. Studies in both ASD patients and mouse models of ASD have demonstrated disrupted learning and memory (Banker et al., 2021); dysregulation of synaptic function and plasticity (Hu et al., 2022; Sohal and Rubenstein, 2019; Zoghbi and Bear, 2012); altered neurotrophic function (Camuso et al., 2022; Reim and Schmeisser, 2017); disrupted neurogenesis (Bukatova et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2023); and increased neuroinflammation (Meng et al., 2024; Xiong et al., 2023). These features may yet be fruitful targets for drug development.

Erythropoietin (EPO) may be an intriguing therapeutic possibility for addressing some or all of these aspects of ASD pathophysiology. Over the last two decades, this endogenous cytokine and anemia treatment has emerged as a potential treatment for a variety of neurological and psychiatric disorders, most notably depression (Newton and Sathyanesan, 2021; Vittori et al., 2021). Studies into EPO’s role in the brain revealed that it is involved in memory improvement; improved synaptic plasticity; increased neurotrophic signaling and neurogenesis; and reduced neuroinflammation (Girgenti et al., 2009; Hassouna et al., 2016; Leconte et al., 2011; Sirén et al., 2009; Vittori et al., 2021). Because of the remarkable overlap between EPO effects and ASD pathophysiology, it is reasonable to hypothesize that EPO could rescue the clinical features of ASD, though few studies have investigated this hypothesis specifically.

However, a critical limitation is that EPO at clinically relevant doses has adverse side effects due to its hematopoietic activity (Newton and Sathyanesan, 2021). In response, the field has shifted its focus to developing EPO analogs that retain the neurological effects but preclude their hematological effects. One such drug is carbamoylated EPO (CEPO), prepared by carbamoylation of key lysine residues of EPO (Leist et al., 2004; Sathyanesan et al., 2018). Like EPO, CEPO improves mood and cognition in rodents (Leconte et al., 2011; Rahmani et al., 2022; Sampath et al., 2020; Sathyanesan et al., 2018), particularly in models of depression, like the stress-susceptible inbred mouse BALB/c (Sampath et al., 2020). These CEPO effects appear to correspond with enhancement of synaptic plasticity, neurotrophic signaling, neuroinflammation, and neurogenesis (Choi et al., 2014; Leconte et al., 2011; Rahmani et al., 2022; Rothschadl et al., 2023; Sampath et al., 2020; Sathyanesan et al., 2017; Tiwari et al., 2021). Importantly, CEPO is safe for at least 10 doses (Pekas et al., 2020; Sampath et al., 2020; Sathyanesan et al., 2018). Thus, CEPO appears to be a suitable alternative for testing the efficacy of non-erythropoietic EPO-like molecules in ASD.

In the present study, we leveraged the BALB/cJ (BALB) mouse to determine whether CEPO can rescue behavioral phenotypes related to ASD. In addition to its depression-related behavioral phenotypes, the BALB/c mouse shows low sociability in the three-chamber social approach task compared to more social C57BL/6J (C57) mice; thus, it is considered an idiopathic mouse model with face validity for ASD (Brodkin, 2007; Sankoorikal et al., 2006). We found that chronic delivery of CEPO rescues sociability--a key phenotype for ASD in model mice--while also alleviating other anxiety-related behaviors relevant to ASD, including in the elevated-plus maze. Overall, this study establishes CEPO as a promising therapeutic for treating several core traits of ASD.

Methods and Materials

Animals

Male BALB/cJ (BALB) mice and male C57BL/6J (C57) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine; BALB/cJ, #000651, C57BL/6J, #000664). Animals arrived at 7 weeks of age and were habituated in the vivarium for 1 week. Drug or vehicle administration began at 8 weeks of age. In total, 45 mice were used in this experiment, 24 BALB mice and 21 C57 mice (

Table 1). The mice were housed with a 12-hour light/dark cycle in

open-top mouse cages (Ancare, Bellmore, NY, USA) with 3-4 mice in each cage. All mice were housed with other animals from the same experimental group. Cages were cleaned twice a week, and all mice had

ad libitum access to food and water. All experimental procedures complied with regulations set by Augustana University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Drug Administration

Carbamoylated erythropoietin (CEPO) was generated at the University of South Dakota according to previously published procedures (Sampath et al., 2020; Sathyanesan et al., 2018; Tiwari et al., 2021, 2019). CEPO dissolved in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4; vehicle) was administered intraperitoneally every other day for 21 days after the mice reached eight weeks of age. The CEPO concentration used was 40 μg/kg, which did not induce hematological changes compared to vehicle in previous studies with erythropoietin and non-hematopoietic erythropoietin derivatives (Leconte et al., 2011; Tiwari et al., 2021). Of the 24 BALB mice, 12 received CEPO, and 12 received vehicle only. Of the 21 C57 mice, 11 received CEPO, and 10 received vehicle only. Mice were weighed before every drug administration to ensure the appropriate doses were delivered and to and monitor health.

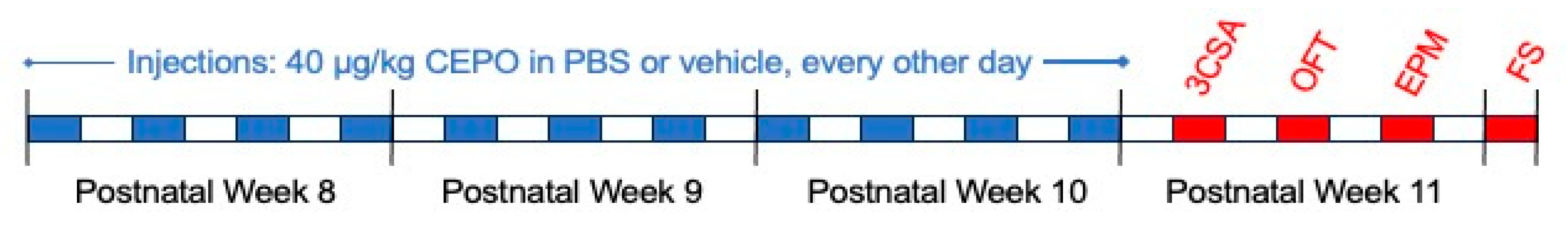

Behavioral Timeline

Following the drug administration period, all mice were subjected to four behavioral tasks (

Figure 1). These tasks were selected to evaluate the effects of CEPO on social behaviors (three-chamber social-approach task), anxiety behaviors (open field and elevated-plus maze), and depression-like behaviors that had been previously evaluated in BALB mice (Sampath et al., 2020). All behavioral experiments took place in a dedicated room under low light (approximately 4 lux) conditions in the presence of white noise (approximately 50 dB; Noise & Co Colored Noise Generator,

https://mynoise.net/NoiseMachines/whiteNoiseGenerator.php).

Three-Chamber Social Approach Task

The three-chamber social approach task aided in the quantification of the sociability of the mice according to previously published protocols (Kloth et al., 2015; Rein et al., 2020). Before the task, the mice were allowed to acclimate in the behavioral room for 30 minutes. This task consisted of three phases, with each phase lasting 10 minutes. In the first phase, the mouse explored a custom-built three-chamber maze (Yang et al., 2011) without any novel objects or mice present. In the second phase, two empty wire mesh pencil cups (Amazon Basics) were placed upside down, one in each of the outermost chambers, and the mouse was again free to explore the maze. Finally, in the third phase, a strain-matched, aged-matched novel stranger mouse was placed in one of the empty cups, and a novel non-social object (plain wooden block) was placed in the opposite cup. Again, the mouse was free to explore the entire space. Between the experimental phases, the mouse was temporarily placed in a separate open-top cage. After the task, the three-chamber maze was cleaned using a 70% ethanol solution.

Each phase was recorded using a PSEye camera (Sony Interactive Entertainment, San Mateo, CA, USA) mounted on the ceiling (Cosgrove et al., 2022). Each video was analyzed by two individuals blinded to the compound injected into the mouse. Phase two recordings were timed manually and analyzed to determine whether there was any side bias that might be present in any individual mouse; to do so, the time of interactions was measured, defined as directed exploratory behavior within 3 cm of an object, with the cups on either side of the maze. Side bias was calculated according to the equation [(left chamber time - right chamber time)/(left chamber time + right chamber time)]. Mice were excluded if the side bias was more extreme than ± 0.7.

Phase three recordings were timed manually and analyzed to determine social and non-social behaviors in the presence of the novel stranger mouse. The following parameters were collected: time spent interacting with both of the cups, defined as directed exploratory behavior within 3 cm of an object; the number of 5-second interaction bouts with each object; the amount of time spent grooming; the number of 5-second bouts of grooming; and the number of rears (Rein et al., 2020). Climbing the cup without interest in the object/animal inside was not counted as social behavior. Rears were defined as vertical movement on the hind legs, either using a wall for support or in the open. Finally, to determine sociability, the sociability index was calculated as [(interaction time with social object - interaction time with non-social object)/(interaction time with social object + interaction time with non-social object)], per previous studies (Rein et al., 2020). A positive sociability index denotes increased interaction time with the novel stranger mouse.

Open Field

The open field task is one measure of the anxiety and exploratory activity of the mice (Seibenhener and Wooten, 2015). The task was carried out as previously described (Cosgrove et al., 2022). Prior to the task, the mice were allowed to acclimate in the behavior room for 30 minutes. The open field maze consisted of a large white Plexiglas box with dimensions of 41 cm x 41 cm x 41 cm and an open top. Mice allowed to explore the maze for 20 minutes. Mice were recorded using a PSEye camera (Sony Interactive Entertainment, San Mateo, CA, USA) mounted on the ceiling. Distance traveled and percentage of time spent in the center of the maze were calculated using a custom MATLAB (RRID: SCR_001622) code, as in previous studies (Cosgrove et al., 2022). The center was defined as 10.25 cm from the walls. Rears were counted and defined as standing on the hind legs, either using a wall for support or in the open. Time spent grooming, as well as the number of 5-second bouts of grooming, were also recorded.

Elevated-Plus Maze

The elevated-plus maze acted as a second measure of anxiety (Walf and Frye, 2007). The elevated-plus maze was 50 cm off the ground: all arms were 50 cm long when measured from the center and 10 cm wide. Two arms on opposite sides of the maze had walls that were 30 cm high; the other two arms were open. Before the task, the mice were allowed to acclimate in the behavior room for 30 minutes. To start the task, mice were placed in the center of the plus and were allowed to explore the maze for 10 minutes. While in the maze, mice were recorded using a PSEye camera (Sony Interactive Entertainment, San Mateo, CA, USA) mounted on the ceiling. Measurements were performed manually, and the metrics analyzed included counting the number of rears, counting the number of times mice entered the open arms, and the time spent grooming.

Forced Swim

The forced swim task measures the tenacity under stress of the mice (Can et al., 2012). The experiment was carried out according to previously published protocols (Cosgrove et al., 2022). Preceding the task, the mice acclimated to the behavior room for 30 minutes. A 3-liter beaker was filled ¾ of the way with water at approximately 25 ℃. The mice were placed in the water for a total of 6 minutes. For the first 2 minutes, the mice acclimated to the water; the final 4 minutes were recorded and analyzed. To analyze this task, the amount of time the mice spent actively paddling (using hind and front limbs to produce rhythmic and propulsive movement) was compared to the amount of time spent immobile.

Statistics

All statistical analysis was done in GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA; RRID:SCR_002798) using the two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test with post hoc comparisons. Post hoc comparisons between groups were carried out following the discovery of statistically significant effects between groups. The Bonferroni-corrected planned comparisons were computed between C57-vehicle mice and BALB-vehicle mice, BALB-vehicle mice and BALB-CEPO mice, and BALB-CEPO mice and C57-vehicle mice (

Figure 2,

Figure 3A,D1,D2 and

Figure 4) or between social object-vehicle and social object-CEPO groups, social object-vehicle and non-social object-vehicle groups, social object-CEPO and non-social object-CEPO groups, and non-social object-vehicle and non-social object-CEPO groups (

Figure 3(B1,B2,C1,C2)). The homoscedasticity of residuals was confirmed using Spearman's rank correlation test, and the normality of residuals was confirmed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. In some cases, data were transformed to satisfy the assumptions of the two-way ANOVA using

or

transformations. These cases are indicated in

Supplementary Table S1. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant unless otherwise specified. A complete report of statistical comparisons in this study can be found in

Supplementary Table S1.

Results

Following a series of 11 injections every other day, mice underwent behavioral testing (

Figure 1). Complete results from statistical analyses can be found in

Supplementary Table S1.

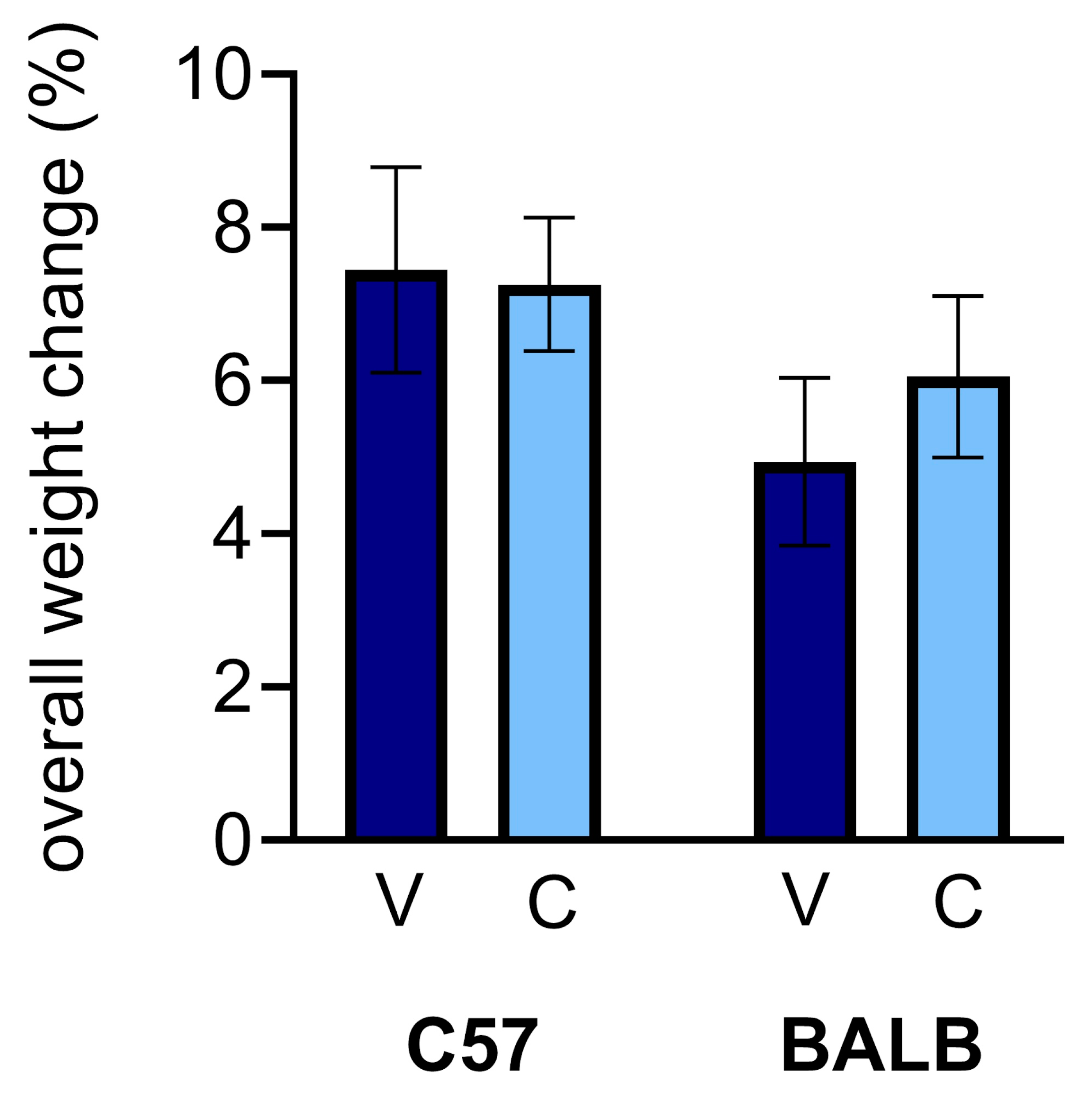

Weights. Unlike erythropoietin administration, CEPO injections have been shown to have a negligible effect on the overall health of mice (Tiwari et al., 2021, 2019). To monitor the effect of CEPO on the physical health of the mice, each mouse was weighed before the injection period and before each subsequent dose. Here, we report on the change in weights from the first injection to the eleventh injection. The percent weight changes for C57 and BALB mice were not significantly different between treatment groups after the complete course of injections, regardless of mouse strain (

Figure 2; two-way ANOVA, treatment effect: p = 0.6759). However, there is a small, but noticeable, strain difference (

Figure 2; two-way ANOVA, strain effect: p = 0.0979).

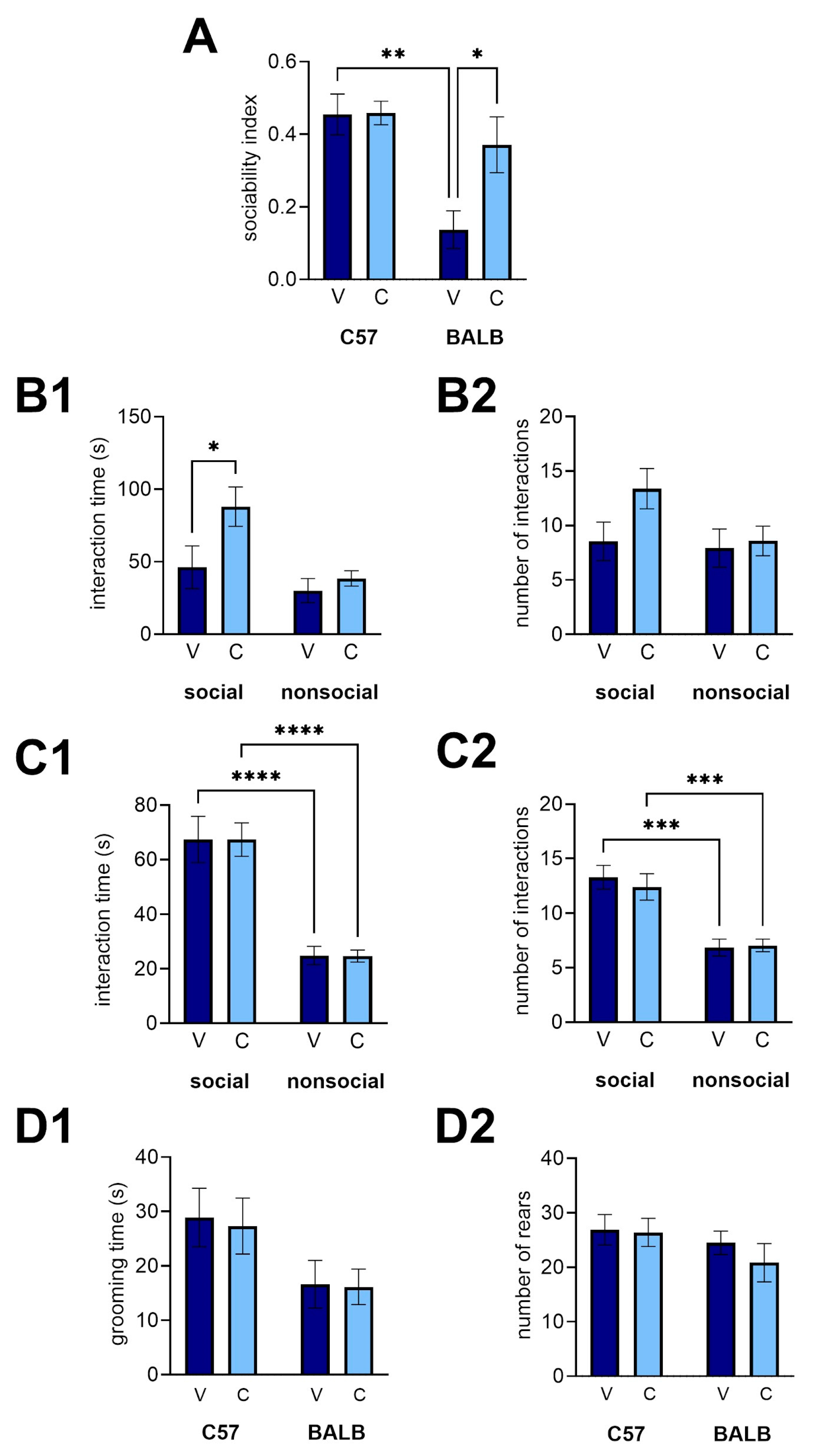

Three-chamber social approach task. We used the three-chamber task to examine whether CEPO could revert well-documented social-approach deficits in male BALB mice to C57 levels. There was a considerable difference in sociability between strains (

Figure 3A; two-way ANOVA with planned comparison, strain effect: p = 0.0008), and the sociability deficit in BALB mice (vehicle mice compared to C57 vehicle mice, p = 0.0015) was rescued by CEPO (

Figure 3A; two-way ANOVA with planned comparisons, treatment effect, p = 0.0388; interaction, p = 0.0456; BALB vehicle vs. BALB CEPO, p = 0.0298; C57 vehicle vs. BALB CEPO: p = 0.7453). Analyzing the interaction time and number of interactions more closely reveals that the improvement in the sociability index is driven almost entirely by an increase in interaction time with the social object (

Figure 3B1; two-way ANOVA with planned comparisons, object effect, p = 0.0323, treatment effect, p = 0.0130, interaction, p = 0.27, social object vehicle vs social object CEPO, p = 0.0493). There was a modest, but statistically insignificant, difference between social object interaction time and non-social object interaction time (p = 0.0803), likely contributing to the difference in sociability. There was no similar significant difference in the amount of time exploring the non-social object (non-social object vehicle vs. non-social object CEPO, p > 0.9999), and BALB vehicle mice showed no significant preference for the social object over the non-social object (p > 0.9999). There was no evidence of a concomitant difference in the number of interactions with either object between the vehicle and CEPO BALBs (

Figure 3B2; two-way ANOVA, treatment effect: p = 0.1173, object effect: p = 0.1119, interaction: p = 0.2257). For C57 mice, no significant difference was observed between the CEPO and vehicle groups (

Figure 3C1; two-way ANOVA, treatment effect: p = 0.8962, interaction: p = 0.2257). As expected, there was a significant difference in the time spent with the social vs. non-social object (

Figure 3C1; two-way ANOVA, object effect: p < 0.0001). These differences in both vehicle and CEPO C57 groups (social object-vehicle vs. non-social object-vehicle, p < 0.0001; social object-CEPO vs. non-social object-vehicle, p < 0.0001) likely account for the positive sociability in both groups. Likewise, for the number of interactions, treatment yielded no significant impact (

Figure 3C2; two-way ANOVA with planned comparisons, treatment effect: p = 0.7142, interaction: p = 0.5679), but there was a significant object effect (p < 0.0001). There was no significant difference in the time spent grooming between treatments, but there was between strains of mice (

Figure 3D1; two-way ANOVA, treatment effect: p = 0.4675, strain effect: p = 0.0269, interaction: p = 0.4707). However, no planned comparison showed significant differences between groups (p > 0.05). There was no significant difference in the number of rears due to strain or treatment (

Figure 3D2; two-way ANOVA, treatment effect: p = 0.4675, strain effect: p = 0.1670, interaction: p = 0.5784).

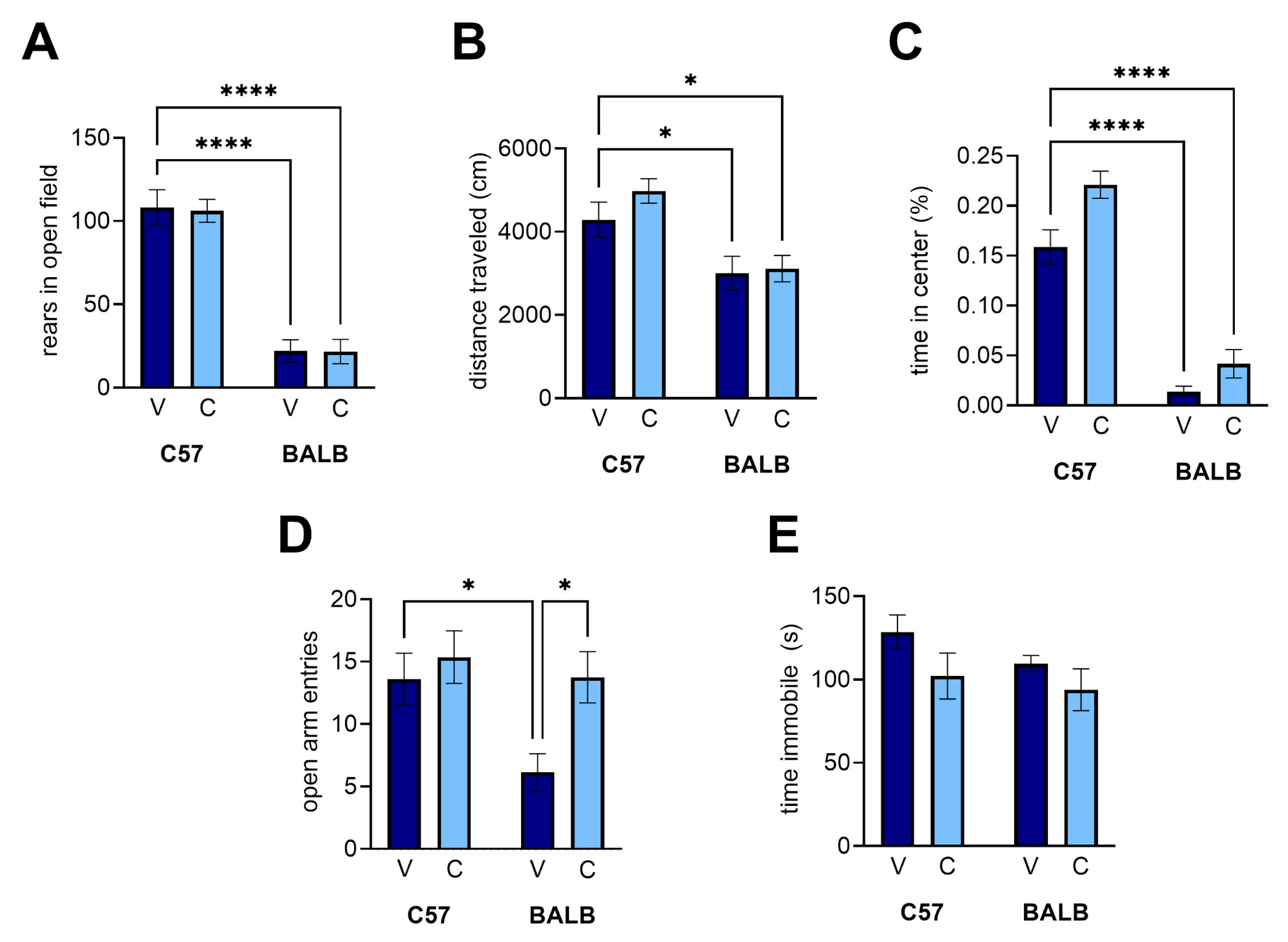

Open field task. We used the open-field task to determine whether CEPO could rescue anxiety-related exploratory behaviors in BALB mice relative to C57 controls (Sankoorikal et al., 2006, 2006). While we were able to recapitulate the anxiety-related differences in rears (

Figure 4A; two-way ANOVA with planned comparisons, strain effect, p < 0.0001, BALB vehicle vs. C57 vehicle, p < 0.0001) and total distance traveled (

Figure 4B; two-way ANOVA with planned comparisons, strain effect, p < 0.0001, BALB vehicle vs. C57 vehicle, p = 0.0713) between BALB and C57 mice, there were no significant differences between the treatments for C57 or BALB mice for rears (

Figure 4A, treatment effect, p = 0.9100, interaction, p = 0.9728) or total distance (

Figure 4B, treatment effect, p = 0.2770, interaction, p = 0.4237). Being generally more anxious, the BALB mice exhibited less exploratory behaviors than their C57 counterparts, independent of receiving the CEPO treatment. We were also able to recapitulate a strain difference in time spent in the center of the open field (

Figure 4C; two-way ANOVA with planned comparisons, strain effect, p < 0.0001) and observed an effect on treatment (treatment effect, p = 0.0282) with no interaction (p = 0.1425). However, this effect is modest at best, as it was not accompanied by statistically significant improvements in either group (C57 CEPO vs. C57 vehicle, p = 0.2338, BALB CEPO vs. BALB vehicle, p = 0.279).

Elevated-plus maze. We used the elevated-plus maze as a second measurement of anxiety in BALB mice, as it has been observed to differ from C57 (Russo et al., 2019). We confirmed a difference between strains (

Figure 4D; two-way ANOVA with planned comparisons, strain effect, p = 0.0212) with a statistical difference between vehicle groups (C57 vehicle vs. BALB vehicle, p = 0.0463). In the BALB mice, treatment with CEPO significantly increased the number of entries the mice made into the open arms (treatment effect, p = 0.0212, BALB interaction, p = 0.1425, BALB vehicle vs. BALB CEPO, p = 0.0295). This increase constituted a rescue in the number of entries made into open arms, as the BALB-CEPO levels are statistically indistinguishable from C57-vehicle levels (p > 0.9999). CEPO had no effect on C57 behavior (p = 0.9538).

Porsolt’s forced swim task. Finally, we used the forced swim task to compare our experiments with prior experiments with CEPO in BALB mice. We observed a modest decrease in immobility time due to treatment that did not reach the level of statistical significance (

Figure 4E; two-way ANOVA with planned comparisons, treatment effect, p = 0.0516). Moreover, we did not observe an appreciable difference in immobility between strains (strain effect, p = 0.1983, interaction, p = 0.6062).

Discussion

We hypothesized that carbamoylated erythropoietin (CEPO) could rescue autism spectrum disorder (ASD)-related behaviors that appear in the BALB/cJ (BALB) mouse model. Like erythropoietin (EPO), CEPO may have a pharmacological profile that may alter the underlying pathophysiology of ASD and thus affect the behaviors that characterize the disorder. Using a battery of tasks that demonstrate significant behavioral differences between BALB and C57 mice (Lalonde and Strazielle, 2008; Sankoorikal et al., 2006), we were able to rescue deficits in the three-chamber social approach task and the elevated-plus maze task, but not in the open field or forced swim tasks. These findings suggest that the administration of CEPO may have value for treating ASD, but the generalizability of these results to the wide variety of mouse models merits further consideration.

We were most interested in whether CEPO could rescue disrupted social behavior, the primary ASD-relevant phenotype in the BALB mouse (Brodkin, 2007; Ellegood and Crawley, 2015). Consistent with other studies examining social approach in the BALB mouse, we found that BALB mice had significantly reduced sociability compared to age-matched C57 controls, particularly in settings with restricted social contact like the three-chamber maze (Arakawa, 2018; Burket et al., 2016; Fairless et al., 2012; Kapitsa et al., 2021; Russo et al., 2019; Sankoorikal et al., 2006). The present study is notable in that it found a more pronounced sociability difference in adult male mice, whereas other studies suggested the sociability deficit seen in juvenile (Kapitsa et al., 2021; Sankoorikal et al., 2006) and adolescent (Fairless et al., 2012; Russo et al., 2019) BALB mice improves with age, as compared to C57 mice. Our observations may be explained by our use of a standardized, three-phase protocol for the three-chamber task, which has been demonstrated to detect social deficits more sensitively (Rein et al., 2020). Semi-chronic administration of CEPO was able to rescue this deficit in BALB mice. This improvement was largely driven by an increase in the amount of time interacting with the stranger mouse, with no change in time interacting with the non-social object or in other exploratory behaviors. This finding may indicate that CEPO decreases putative social interaction deficits in the BALB mouse (An et al., 2011), without altering overall activity in the task.

Our study is the first demonstration of a role for non-hematopoietic EPO derivatives in rescuing social dysfunction, and it is just the fourth study to examine EPO or its derivatives in an ASD rodent model (Haratizadeh et al., 2023b; Hosny et al., 2023; Solmaz et al., 2020). These three prior studies looked at social behavior in environmentally induced rat models of autism. Solmaz and colleagues (2020) found that daily EPO administration of a relatively high dose improved social interaction time in liposaccharide-exposed male rats, but sociability overall was not addressed. Hosny and colleagues (2023) made a similar observation in EPO-treated propionic acid-exposed rats, albeit in the open field. Haratizadeh and colleagues (2023) observed that early postnatal EPO administration did not rescue sociability in valproic acid-exposed rats but did improve social preference, indicating an improvement in memory that is consistent with other studies. Other studies investigating the therapeutic potential of erythropoietin have demonstrated its ability to rescue three-chamber social approach behavior in rodent models of other neurodevelopmental insults, including prenatal brain injury (Robinson et al., 2018). Together, this evidence suggests a role for EPO in modulating social behavior. Our study builds on this work by exploring the role of an EPO derivative using the “gold standard” of social behavior--the three-chamber social approach task--in an idiopathic mouse model that more closely examines the complex genetic background of ASD. Future work could leverage transgenic mouse models of ASD-related single-gene disorders to understand the generalizability of the effects of CEPO on social behavior and uncover the mechanisms underlying these actions.

The BALB mouse also demonstrates anxiety-related behavior, an ASD-related behavior that might also explain the social deficits (Burket et al., 2016; Russo et al., 2019). In our study, we documented that BALB mice exhibited significantly less time in the center of the open field and significantly fewer entries into the open arms of the elevated-plus maze, compared to C57 controls. This is consistent with other studies (Russo et al., 2019). However, where CEPO was able to rescue the number of open-arm entries, it made a small but statistically insignificant improvement in behavior in the open field. This finding in the open field is consistent with previous studies on the acute effects of CEPO in BALB mice (Sampath et al., 2020). Our results suggest that CEPO improves a mechanism underlying one distinct aspect of anxiety-related behavior, but not others; indeed, findings in the elevated-plus maze and the open field in BALB mice and other strains are often weakly correlated (Carola et al., 2002). Moreover, it remains to be seen whether this effect in the elevated-plus is related to the change in social behavior. A small number of studies show a weak correlation between elevated-plus behavior and social behavior in BALB mice (An et al., 2011; Russo et al., 2019), and none of the previous studies on the effects of EPO and its derivatives in social behavior examined anxiety-related behavior as well. It is entirely possible that CEPO acts on distinct mechanisms responsible for social and anxiety-related behaviors.

It should be noted that we were unable to replicate the rescue of depression-like behavior in the forced swim that had been previously observed with CEPO in BALB mice (Sampath et al., 2020), and with EPO in some studies with other rodent models (Osborn et al., 2013). We speculate that these differences might be accounted for by slight differences in the forced-swim protocol used in our laboratory, or due to washout several days after the last CEPO injection. Prior studies have evaluated the effects of EPO and its derivatives delivered just hours before the forced-swim task (Leconte et al., 2011; Osborn et al., 2013; Pekas et al., 2020; Sampath et al., 2020). This point highlights the importance of evaluating the long-lasting impacts of CEPO after cessation of the drug, not just for depression-like behaviors but for ASD-relevant behaviors as well.

The mechanism by which CEPO affects social behavior in BALB mice remains unknown. CEPO has been demonstrated to elevate levels of neurotrophic factors, including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Sathyanesan et al., 2018; Tiwari et al., 2021); engage immediate early genes and other mechanisms that modulate synaptic function (Leconte et al., 2011; Tiwari et al., 2021, 2019); regulate neuronal development and dendritic outgrowth (Choi et al., 2014; Rahmani et al., 2022; Tiwari et al., 2021); alter the neuroinflammatory response and modulate glial function (Villa et al., 2007; Rahmani et al., 2022); and regulate neurogenesis (Leconte et al., 2011), among other functions (Newton and Sathyanesan, 2021). Though these findings were primarily restricted to the hippocampus--which plays a role in social memory--it is possible that CEPO causes similar alterations in other parts of the social circuitry. However, it is unclear which mechanisms would be responsible for our observations in this study. The few studies that have addressed the mechanisms underlying social dysfunction in BALB mice have focused on improving glutamatergic transmission (Deutsch et al., 2011; Jacome et al., 2011)--suggesting overlap with the pro-neuroplastic properties of CEPO--or on altering the serotonin-oxytocin pathway (Arakawa, 2017). These studies do not exclude the possibility that other mechanisms are involved. In this direction, there is evidence that the mechanisms engaged by CEPO, EPO, and other EPO derivatives might correct social behavior in ASD animal models. For example, in their study of EPO administration on liposaccharide-exposed rats, Solmaz observed diminished TNF-ɑ levels and reduced glial activity concomitant with improvements in social behavior (Solmaz et al., 2020). Another study observed a similar relationship between glial activity and social behavior using an EPO derivative (Haratizadeh et al., 2023a). Still, other studies that use non-EPO compounds that engage similar mechanisms have shown improvements in sociability (Hagen et al., 2015; Luo et al., 2023; Perets et al., 2018, 2017; Segal-Gavish et al., 2016). Future work should examine the mechanisms underlying social dysfunction in BALB mice and whether CEPO directly influences those mechanisms in a manner that correlates with social improvement.

There are several ways that our study--focused on delivering CEPO to a single ASD mouse model, semi-chronically in young adulthood--should be extended to understand how generally effective CEPO and other EPO derivatives can be as ASD treatments. While the BALB mouse, as an idiopathic mouse model, more closely mimics the genetic underpinnings of autism in patients, it is by no means representative of all ASD cases. For instance, one study that used neuroimaging to understand the heterogeneity of ASD mouse models showed that BALB mice are included in one of three clusters, suggesting important pathophysiological differences among models of the same disorder (Ellegood et al., 2013). It will be necessary to extend our work to other ASD mouse models outside the BALB cluster to determine whether CEPO or other EPO derivatives are generally effective at rescuing social disruption, and whether that rescue is associated with similar changes at the cellular and molecular level. It will also be necessary to understand how sex plays a role as a biological variable--both from the standpoint of sex differences in social dysfunction and in sex differences in CEPO effectiveness. In addition, the limits of CEPO administration remain to be seen. It will be important to examine whether CEPO administration is more or less effective at different developmental time points, as ASD is a chronic disorder (Castrén et al., 2012).Furthermore, it is crucial to understand how long the effects of semi-chronic dosing of CEPO last. Answering these questions will be essential to understanding how to extend this limited study to a more broadly effective eventual treatment for ASD patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (P20GM103443), by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health (R01MH106640) to S.S.N., and by the National Science Foundation/EPSCoR Award No. IIA-1355423 to the South Dakota Board of Regents. Special thanks to Brenda Rieger and Brian Vander Aarde of Augustana University for animal husbandry and technical assistance.

References

- Aishworiya, R., Valica, T., Hagerman, R., Restrepo, B., 2022. An Update on Psychopharmacological Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neurotherapeutics 19, 248–262. [CrossRef]

- An, X.-L., Zou, J.-X., Wu, R.-Y., Yang, Y., Tai, F.-D., Zeng, S.-Y., Jia, R., Zhang, X., Liu, E.-Q., Broders, H., 2011. Strain and Sex Differences in Anxiety-Like and Social Behaviors in C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ Mice. Exp. Anim. 60, 111–123. [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, H., 2018. Analysis of Social Process in Two Inbred Strains of Male Mice: A Predominance of Contact-Based Investigation in BALB/c Mice. Neuroscience 369, 124–138. [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, H., 2017. Involvement of serotonin and oxytocin in neural mechanism regulating amicable social signal in male mice: Implication for impaired recognition of amicable cues in BALB/c strain. Behav. Neurosci. 131, 176–191. [CrossRef]

- Banker, S.M., Gu, X., Schiller, D., Foss-Feig, J.H., 2021. Hippocampal contributions to social and cognitive deficits in autism spectrum disorder. Trends Neurosci. 44, 793–807. [CrossRef]

- Brodkin, E.S., 2007. BALB/c mice: low sociability and other phenotypes that may be relevant to autism. Behav. Brain Res. 176, 53–65. [CrossRef]

- Bukatova, S., Bacova, Z., Osacka, J., Bakos, J., 2023. Mini review of molecules involved in altered postnatal neurogenesis in autism. Int. J. Neurosci. 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Burket, J.A., Young, C.M., Green, T.L., Benson, A.D., Deutsch, S.I., 2016. Characterization of gait and olfactory behaviors in the Balb/c mouse model of autism spectrum disorders. Brain Res. Bull. 122, 29–34. [CrossRef]

- Cakir, J., Frye, R.E., Walker, S.J., 2020. The lifetime social cost of autism: 1990–2029. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 72, 101502. [CrossRef]

- Camuso, S., La Rosa, P., Fiorenza, M.T., Canterini, S., 2022. Pleiotropic effects of BDNF on the cerebellum and hippocampus: Implications for neurodevelopmental disorders. Neurobiol. Dis. 163, 105606. [CrossRef]

- Can, A., Dao, D.T., Arad, M., Terrillion, C.E., Piantadosi, S.C., Gould, T.D., 2012. The Mouse Forced Swim Test. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 3638. [CrossRef]

- Carola, V., D’Olimpio, F., Brunamonti, E., Mangia, F., Renzi, P., 2002. Evaluation of the elevated plus-maze and open-field tests for the assessment of anxiety-related behaviour in inbred mice. Behav. Brain Res. 134, 49–57. [CrossRef]

- Castrén, E., Elgersma, Y., Maffei, L., Hagerman, R., 2012. Treatment of neurodevelopmental disorders in adulthood. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 32, 14074–14079. [CrossRef]

- Choi, M., Ko, S.Y., Lee, I.Y., Wang, S.E., Lee, S.H., Oh, D.H., Kim, Y.-S., Son, H., 2014. Carbamylated erythropoietin promotes neurite outgrowth and neuronal spine formation in association with CBP/p300. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 446, 79–84. [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, J.A., Kelly, L.K., Kiffmeyer, E.A., Kloth, A.D., 2022. Sex-dependent influence of postweaning environmental enrichment in Angelman syndrome model mice. Brain Behav. e2468. [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, S.I., Burket, J.A., Jacome, L.F., Cannon, W.R., Herndon, A.L., 2011. d-Cycloserine improves the impaired sociability of the Balb/c mouse. Brain Res. Bull. 84, 8–11. [CrossRef]

- Ellegood, J., Babineau, B.A., Henkelman, R.M., Lerch, J.P., Crawley, J.N., 2013. Neuroanatomical analysis of the BTBR mouse model of autism using magnetic resonance imaging and diffusion tensor imaging. NeuroImage 70, 288–300. [CrossRef]

- Ellegood, J., Crawley, J.N., 2015. Behavioral and Neuroanatomical Phenotypes in Mouse Models of Autism. Neurotherapeutics 12, 521–533. [CrossRef]

- Fairless, A.H., Dow, H.C., Kreibich, A.S., Torre, M., Kuruvilla, M., Gordon, E., Morton, E.A., Tan, J., Berrettini, W.H., Li, H., Abel, T., Brodkin, E.S., 2012. Sociability and brain development in BALB/cJ and C57BL/6J mice. Behav. Brain Res. 228, 299–310. [CrossRef]

- Gandal, M.J., Leppa, V., Won, H., Parikshak, N.N., Geschwind, D.H., 2016. The road to precision psychiatry: translating genetics into disease mechanisms. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 1397–1407. [CrossRef]

- Girgenti, M.J., Hunsberger, J., Duman, C.H., Sathyanesan, M., Terwilliger, R., Newton, S.S., 2009. Erythropoietin induction by electroconvulsive seizure, gene regulation, and antidepressant-like behavioral effects. Biol. Psychiatry 66, 267–274. [CrossRef]

- Hagen, E., Shprung, D., Minakova, E., Washington, J., Kumar, U., Shin, D., Sankar, R., Mazarati, A., 2015. Autism-Like Behavior in BTBR Mice Is Improved by Electroconvulsive Therapy. Neurotherapeutics 12, 657–666. [CrossRef]

- Haratizadeh, S., Ranjbar, M., Basiri, M., Nozari, M., 2023a. Astrocyte responses to postnatal erythropoietin and nano-erythropoietin treatments in a valproic acid-induced animal model of autism. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 130, 102257. [CrossRef]

- Haratizadeh, S., Ranjbar, M., Darvishzadeh-Mahani, F., Basiri, M., Nozari, M., 2023b. The effects of postnatal erythropoietin and nano-erythropoietin on behavioral alterations by mediating K-Cl co-transporter 2 in the valproic acid-induced rat model of autism. Dev. Psychobiol. 65, e22353. [CrossRef]

- Hassouna, I., Ott, C., Wüstefeld, L., Offen, N., Neher, R.A., Mitkovski, M., Winkler, D., Sperling, S., Fries, L., Goebbels, S., Vreja, I.C., Hagemeyer, N., Dittrich, M., Rossetti, M.F., Kröhnert, K., Hannke, K., Boretius, S., Zeug, A., Höschen, C., Dandekar, T., Dere, E., Neher, E., Rizzoli, S.O., Nave, K.-A., Sirén, A.-L., Ehrenreich, H., 2016. Revisiting adult neurogenesis and the role of erythropoietin for neuronal and oligodendroglial differentiation in the hippocampus. Mol. Psychiatry 21, 1752–1767. [CrossRef]

- Hosny, S., Abdelmenem, A., Azouz, T., S. Kamar, S., M. ShamsEldeen, A., A. El-Shafei, A., 2023. Beneficial Effect of Erythropoietin on Ameliorating Propionic Acid-Induced Autistic-Like Features in Young Rats. ACTA Histochem. Cytochem. 56, 77–86. [CrossRef]

- Hu, C., Li, H., Li, J., Luo, X., Hao, Y., 2022. Microglia: Synaptic modulator in autism spectrum disorder. Front. Psychiatry 13, 958661. [CrossRef]

- Jacome, L.F., Burket, J.A., Herndon, A.L., Cannon, W.R., Deutsch, S.I., 2011. D-serine improves dimensions of the sociability deficit of the genetically-inbred Balb/c mouse strain. Brain Res. Bull. 84, 12–16. [CrossRef]

- Kapitsa, I.G., Ivanova, E.A., Voronina, T.A., Seredenin, S.B., 2021. Characteristics of the Behavioral Phenotype of BALB/C Mice. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 51, 93–99. [CrossRef]

- Kloth, A.D., Badura, A., Li, A., Cherskov, A., Connolly, S.G., Giovannucci, A., Bangash, M.A., Grasselli, G., Peñagarikano, O., Piochon, C., Tsai, P.T., Geschwind, D.H., Hansel, C., Sahin, M., Takumi, T., Worley, P.F., Wang, S.S.-H., 2015. Cerebellar associative sensory learning defects in five mouse autism models. eLife 4, e06085. [CrossRef]

- Lalonde, R., Strazielle, C., 2008. Relations between open-field, elevated plus-maze, and emergence tests as displayed by C57/BL6J and BALB/c mice. J. Neurosci. Methods 171, 48–52. [CrossRef]

- Leconte, C., Bihel, E., Lepelletier, F.-X., Bouët, V., Saulnier, R., Petit, E., Boulouard, M., Bernaudin, M., Schumann-Bard, P., 2011. Comparison of the effects of erythropoietin and its carbamylated derivative on behaviour and hippocampal neurogenesis in mice. Neuropharmacology 60, 354–364. [CrossRef]

- Leist, M., Ghezzi, P., Grasso, G., Bianchi, R., Villa, P., Fratelli, M., Savino, C., Bianchi, M., Nielsen, J., Gerwien, J., Kallunki, P., Larsen, A.K., Helboe, L., Christensen, S., Pedersen, L.O., Nielsen, M., Torup, L., Sager, T., Sfacteria, A., Erbayraktar, S., Erbayraktar, Z., Gokmen, N., Yilmaz, O., Cerami-Hand, C., Xie, Q.-W., Coleman, T., Cerami, A., Brines, M., 2004. Derivatives of erythropoietin that are tissue protective but not erythropoietic. Science 305, 239–242. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Liu, J., Gong, H., Liu, T., Li, X., Fan, X., 2023. Implication of Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Implications. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 21, 2266–2282. [CrossRef]

- Lord, C., Brugha, T.S., Charman, T., Cusack, J., Dumas, G., Frazier, T., Jones, E.J.H., Jones, R.M., Pickles, A., State, M.W., Taylor, J.L., Veenstra-VanderWeele, J., 2020. Autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 6, 5. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y., Lv, K., Du, Z., Zhang, D., Chen, M., Luo, J., Wang, L., Liu, T., Gong, H., Fan, X., 2023. Minocycline improves autism-related behaviors by modulating microglia polarization in a mouse model of autism. Int. Immunopharmacol. 122, 110594. [CrossRef]

- Maenner, M.J., Shaw, K.A., Bakian, A.V., Bilder, D.A., Durkin, M.S., Esler, A., Furnier, S.M., Hallas, L., Hall-Lande, J., Hudson, A., Hughes, M.M., Patrick, M., Pierce, K., Poynter, J.N., Salinas, A., Shenouda, J., Vehorn, A., Warren, Z., Constantino, J.N., DiRienzo, M., Fitzgerald, R.T., Grzybowski, A., Spivey, M.H., Pettygrove, S., Zahorodny, W., Ali, A., Andrews, J.G., Baroud, T., Gutierrez, J., Hewitt, A., Lee, L.-C., Lopez, M., Mancilla, K.C., McArthur, D., Schwenk, Y.D., Washington, A., Williams, S., Cogswell, M.E., 2021. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2018. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. Surveill. Summ. Wash. DC 2002 70, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Manoli, D.S., State, M.W., 2021. Autism Spectrum Disorder Genetics and the Search for Pathological Mechanisms. Am. J. Psychiatry 178, 30–38. [CrossRef]

- Meng, J., Zhang, L., Zhang, Y.-W., 2024. Microglial Dysfunction in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neurosci. Rev. J. Bringing Neurobiol. Neurol. Psychiatry 10738584241252576. [CrossRef]

- Newton, S.S., Sathyanesan, M., 2021. Erythropoietin and Non-Erythropoietic Derivatives in Cognition. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 728725. [CrossRef]

- Osborn, M., Rustom, N., Clarke, M., Litteljohn, D., Rudyk, C., Anisman, H., Hayley, S., 2013. Antidepressant-Like Effects of Erythropoietin: A Focus on Behavioural and Hippocampal Processes. PLOS ONE 8, e72813. [CrossRef]

- Pekas, N.J., Petersen, J.L., Sathyanesan, M., Newton, S.S., 2020. Design and Development of a Behaviorally Active Recombinant Neurotrophic Factor. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 14, 5393–5403. [CrossRef]

- Perets, N., Hertz, S., London, M., Offen, D., 2018. Intranasal administration of exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells ameliorates autistic-like behaviors of BTBR mice. Mol. Autism 9, 57. [CrossRef]

- Perets, N., Segal-Gavish, H., Gothelf, Y., Barzilay, R., Barhum, Y., Abramov, N., Hertz, S., Morozov, D., London, M., Offen, D., 2017. Long term beneficial effect of neurotrophic factors-secreting mesenchymal stem cells transplantation in the BTBR mouse model of autism. Behav. Brain Res. 331, 254–260. [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, N., Mohammadi, M., Manaheji, H., Maghsoudi, N., Katinger, H., Baniasadi, M., Zaringhalam, J., 2022. Carbamylated erythropoietin improves recognition memory by modulating microglia in a rat model of pain. Behav. Brain Res. 416, 113576. [CrossRef]

- Reim, D., Schmeisser, M.J., 2017. Neurotrophic Factors in Mouse Models of Autism Spectrum Disorder: Focus on BDNF and IGF-1. Adv. Anat. Embryol. Cell Biol. 224, 121–134. [CrossRef]

- Rein, B., Ma, K., Yan, Z., 2020. A standardized social preference protocol for measuring social deficits in mouse models of autism. Nat. Protoc. 15, 3464–3477. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S., Corbett, C.J., Winer, J.L., Chan, L.A.S., Maxwell, J.R., Anstine, C.V., Yellowhair, T.R., Andrews, N.A., Yang, Y., Sillerud, L.O., Jantzie, L.L., 2018. Neonatal erythropoietin mitigates impaired gait, social interaction and diffusion tensor imaging abnormalities in a rat model of prenatal brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 302, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Rothschadl, M.J., Sathyanesan, M., Newton, S.S., 2023. Synergism of Carbamoylated Erythropoietin and Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 in Immediate Early Gene Expression. Life Basel Switz. 13, 1826. [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.M., Lawther, A.J., Prior, B.M., Isbel, L., Somers, W.G., Lesku, J.A., Richdale, A.L., Dissanayake, C., Kent, S., Lowry, C.A., Hale, M.W., 2019. Social approach, anxiety, and altered tryptophan hydroxylase 2 activity in juvenile BALB/c and C57BL/6J mice. Behav. Brain Res. 359, 918–926. [CrossRef]

- Sampath, D., McWhirt, J., Sathyanesan, M., Newton, S.S., 2020. Carbamoylated erythropoietin produces antidepressant-like effects in male and female mice. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 96, 109754. [CrossRef]

- Sankoorikal, G.M.V., Kaercher, K.A., Boon, C.J., Lee, J.K., Brodkin, E.S., 2006. A mouse model system for genetic analysis of sociability: C57BL/6J versus BALB/cJ inbred mouse strains. Biol. Psychiatry 59, 415–423. [CrossRef]

- Sathyanesan, M., Haiar, J.M., Watt, M.J., Newton, S.S., 2017. Restraint stress differentially regulates inflammation and glutamate receptor gene expression in the hippocampus of C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice. Stress 20, 197–204. [CrossRef]

- Sathyanesan, M., Watt, M.J., Haiar, J.M., Scholl, J.L., Davies, S.R., Paulsen, R.T., Wiederin, J., Ciborowski, P., Newton, S.S., 2018. Carbamoylated erythropoietin modulates cognitive outcomes of social defeat and differentially regulates gene expression in the dorsal and ventral hippocampus. Transl. Psychiatry 8, 113. [CrossRef]

- Segal-Gavish, H., Karvat, G., Barak, N., Barzilay, R., Ganz, J., Edry, L., Aharony, I., Offen, D., Kimchi, T., 2016. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation Promotes Neurogenesis and Ameliorates Autism Related Behaviors in BTBR Mice. Autism Res. 9, 17–32. [CrossRef]

- Seibenhener, M.L., Wooten, M.C., 2015. Use of the Open Field Maze to Measure Locomotor and Anxiety-like Behavior in Mice. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 52434. [CrossRef]

- Sirén, A.-L., Faßhauer, T., Bartels, C., Ehrenreich, H., 2009. Therapeutic potential of erythropoietin and its structural or functional variants in the nervous system. Neurotherapeutics 6, 108–127. [CrossRef]

- Sohal, V.S., Rubenstein, J.L.R., 2019. Excitation-inhibition balance as a framework for investigating mechanisms in neuropsychiatric disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 24, 1248–1257. [CrossRef]

- Solmaz, V., Erdoğan, M.A., Alnak, A., Meral, A., Erbaş, O., 2020. Erythropoietin shows gender dependent positive effects on social deficits, learning/memory impairments, neuronal loss and neuroinflammation in the lipopolysaccharide induced rat model of autism. Neuropeptides 83, 102073. [CrossRef]

- Sztainberg, Y., Zoghbi, H.Y., 2016. Lessons learned from studying syndromic autism spectrum disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 1408–1417. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, N.K., Sathyanesan, M., Kumar, V., Newton, S.S., 2021. A Comparative Analysis of Erythropoietin and Carbamoylated Erythropoietin Proteome Profiles. Life 11, 359. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, N.K., Sathyanesan, M., Schweinle, W., Newton, S.S., 2019. Carbamoylated erythropoietin induces a neurotrophic gene profile in neuronal cells. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 88, 132–141. [CrossRef]

- Vittori, D.C., Chamorro, M.E., Hernández, Y.V., Maltaneri, R.E., Nesse, A.B., 2021. Erythropoietin and derivatives: Potential beneficial effects on the brain. J. Neurochem. 158, 1032–1057. [CrossRef]

- Walf, A.A., Frye, C.A., 2007. The use of the elevated plus maze as an assay of anxiety-related behavior in rodents. Nat. Protoc. 2, 322–328. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y., Chen, J., Li, Y., 2023. Microglia and astrocytes underlie neuroinflammation and synaptic susceptibility in autism spectrum disorder. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1125428. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M., Silverman, J.L., Crawley, J.N., 2011. Automated three-chambered social approach task for mice. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. Chapter 8, Unit 8.26. [CrossRef]

- Zoghbi, H.Y., Bear, M.F., 2012. Synaptic dysfunction in neurodevelopmental disorders associated with autism and intellectual disabilities. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a009886. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Experimental timeline for this experiment. Drug administration (blue) took place over three weeks, starting 9 weeks postnatal, with a period of behavioral testing (red) following drug administration. Each division corresponds to one day. PBS, phosphate buffered saline; 3CSA, three-chamber social approach task; OFT, open field task; EPM, elevated-plus maze task; FS, Porsolt’s forced swim test.

Figure 1.

Experimental timeline for this experiment. Drug administration (blue) took place over three weeks, starting 9 weeks postnatal, with a period of behavioral testing (red) following drug administration. Each division corresponds to one day. PBS, phosphate buffered saline; 3CSA, three-chamber social approach task; OFT, open field task; EPM, elevated-plus maze task; FS, Porsolt’s forced swim test.

Figure 2.

CEPO administration did not significantly impact the weights of mice of either strain compared to vehicle injection (two-way ANOVA followed by planned comparisons, p > 0.05). Dark blue, vehicle (V) injections; light blue, CEPO (C) injections. Error bars represent ± standard error of the mean.

Figure 2.

CEPO administration did not significantly impact the weights of mice of either strain compared to vehicle injection (two-way ANOVA followed by planned comparisons, p > 0.05). Dark blue, vehicle (V) injections; light blue, CEPO (C) injections. Error bars represent ± standard error of the mean.

Figure 3.

CEPO administration in the BALB mice recovered social approach deficits in the three-chamber task. (A) Sociability index in the three-chamber task for each strain. (B1) Interaction time and (B2) number of interactions with each object for BALB mice. (C1) Interaction time and (C2) number of interactions for C57 mice. (D1) Grooming time and (D2) number of rears during the three-chamber task for each strain. V, vehicle injections, C, CEPO injections. Error bars represent ± standard error of the mean. Two-way ANOVA with planned comparisons: *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001, ***, p < 0.0001.

Figure 3.

CEPO administration in the BALB mice recovered social approach deficits in the three-chamber task. (A) Sociability index in the three-chamber task for each strain. (B1) Interaction time and (B2) number of interactions with each object for BALB mice. (C1) Interaction time and (C2) number of interactions for C57 mice. (D1) Grooming time and (D2) number of rears during the three-chamber task for each strain. V, vehicle injections, C, CEPO injections. Error bars represent ± standard error of the mean. Two-way ANOVA with planned comparisons: *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001, ***, p < 0.0001.

Figure 4.

CEPO administration affected open arm entries in the elevated-plus maze but not behavior in the open field task and the forced swim task. (A) Rears in the open field. (B) distance traveled in the open field. (C) Percentage of time spent in the center of the open field. (D) Open arm entries, elevated-plus maze. (E) Immobility time, forced swim task. V, vehicle injections, C, CEPO injections. Error bars represent ± standard error of the mean. Two-way ANOVA with planned comparisons: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001, ****, p < 0.0001.

Figure 4.

CEPO administration affected open arm entries in the elevated-plus maze but not behavior in the open field task and the forced swim task. (A) Rears in the open field. (B) distance traveled in the open field. (C) Percentage of time spent in the center of the open field. (D) Open arm entries, elevated-plus maze. (E) Immobility time, forced swim task. V, vehicle injections, C, CEPO injections. Error bars represent ± standard error of the mean. Two-way ANOVA with planned comparisons: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001, ****, p < 0.0001.

Table 1.

Number of animals used in this study.

Table 1.

Number of animals used in this study.

| |

BALB (n = 24 total) |

C57 (n = 21 total) |

| Carbamoylated erythropoietin (CEPO, 40 μg/kg; n = 23 total) |

12 |

11 |

| Vehicle (n = 22 total) |

12 |

10 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).