Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Open-Source Parametric Design

2.2. Pipe Fitting Customization and 3D Printing

2.3. Pipe Fitting Testing

2.4. Economic Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Open-Source Parametric Pipe Fittings

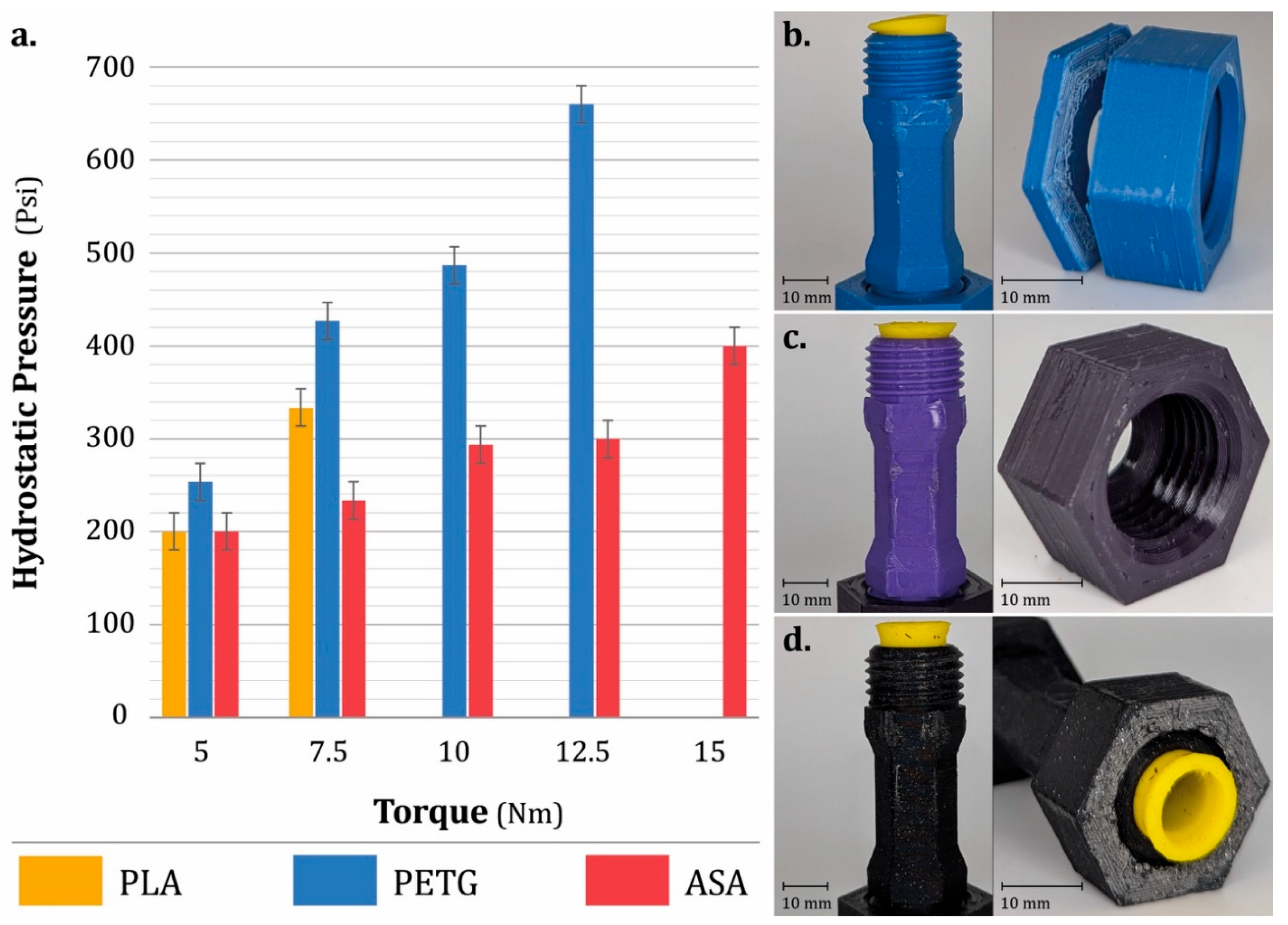

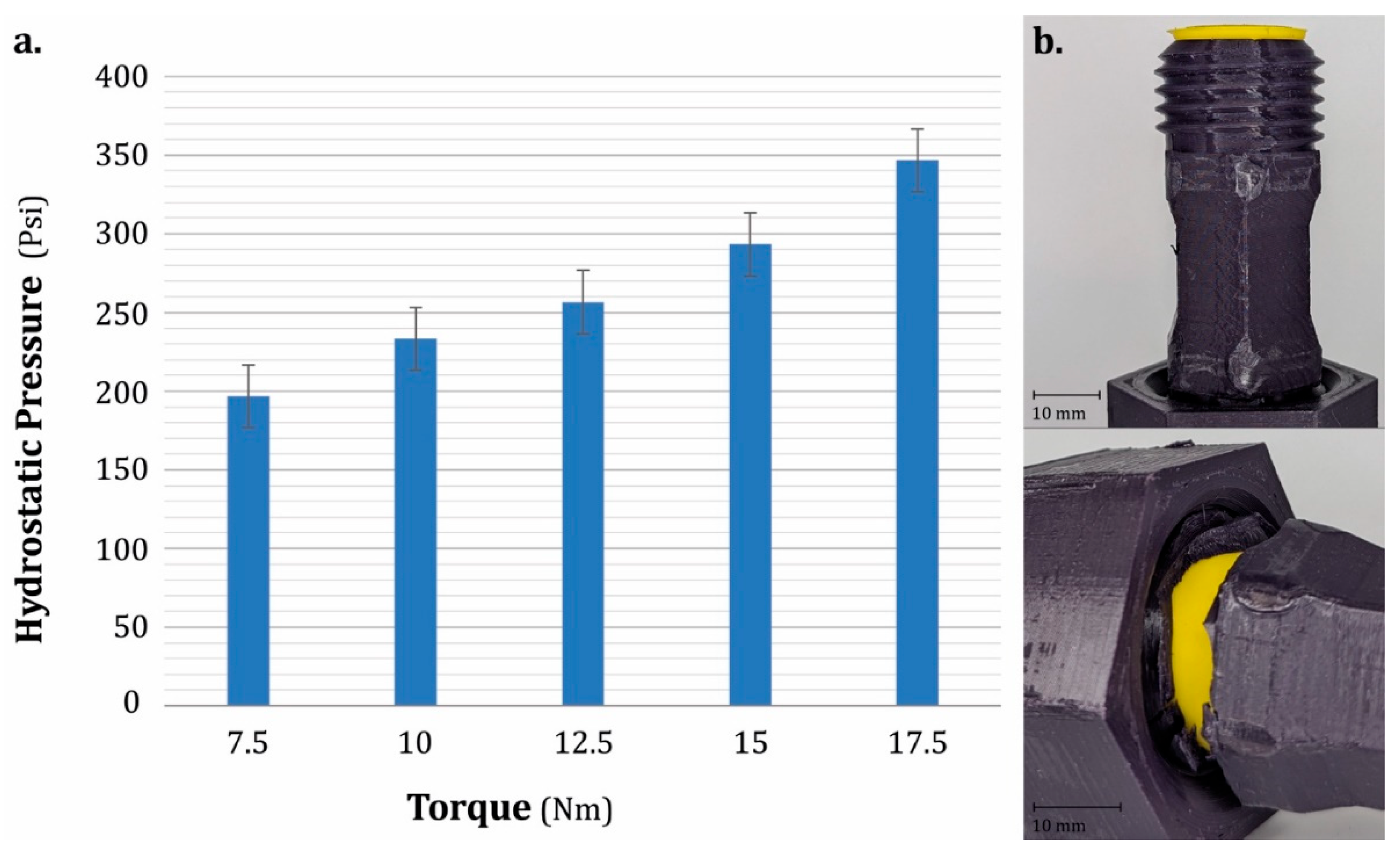

3.2. Pipe Fitting Testing

3.3. Economic Analysis

3.4. Impact, Application Context, and Feasibility

3.5. Future Work

4. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- K. D. R. R.A, “Growing Population and Climate Challenges How To Effects the Future Social Structural Changes and World Conflicts In 21st Century,” SSRN Electron. J., 2020. [CrossRef]

- An Urbanizing World, vol. 55.

- Dhawan, P.; Torre, D.D.; Zanfei, A.; Menapace, A.; Larcher, M.; Righetti, M., “Assessment of ERA5-Land Data in Medium-Term Drinking Water Demand Modelling with Deep Learning,” Water, vol. 15, no. 8, Art. no. 8, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- “Sustainability Insights Research: Lost Water: Challenges And Opportunities | S&P Global Ratings.” Accessed: May 02, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.spglobal.com/ratings/en/research/pdf-articles/230906-sustainability-insights-research-lost-water-challenges-and-opportunities-101585883.

- “Experimental Quantification of Contaminant Ingress into a Buried Leaking Pipe during Transient Events.” Accessed: Jul. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ascelibrary.org/doi/epdf/10.1061/%28ASCE%29HY.1943-7900.0001040.

- Bishoge, O.K., “Challenges facing sustainable water supply, sanitation and hygiene achievement in urban areas in sub-Saharan Africa,” Local Environ., vol. 26, no. 7, pp. 893–907, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Dighade, R.R.; Kadu, M.S.; Pande, A.M., “Challenges in Water Loss Management of Water Distribution Systems in Developing Countries,” vol. 3, no. 6, 2007.

- Bulti, A.T.; Yutura, G.A., “Water infrastructure resilience and water supply and sanitation development challenges in developing countries,” AQUA — Water Infrastruct. Ecosyst. Soc., vol. 72, no. 6, pp. 1057–1064, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Liemberger, R.; Wyatt, A., “Quantifying the global non-revenue water problem,” Water Supply, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 831–837, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- “Energy and Costs of Leaky Pipes: Toward Comprehensive Picture.” Accessed: Jul. 18, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ascelibrary.org/doi/epdf/10.1061/%28ASCE%290733-9496%282002%29128%3A6%28441%29.

- “Rain Bird Easy Fit 0.5-in Drip Irrigation Compression Fitting Coupling.” Accessed: Nov. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.rona.ca/en/product/rain-bird-easy-fit-05-in-drip-irrigation-compression-fitting-coupling-efc25-1pk-32025049.

- “SharkBite K120Z2 EvoPEX Connector x 1/2 Inch MNPT RT, Push-to-Connect, PEX, Misc, Tools & Home Improvement - Amazon Canada.” Accessed: Nov. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.amazon.ca/SharkBite-K120Z2-Plumbing-Connector-Misc/dp/B07WRFDKZ7.

- “John Guest 1/4 in. Polypropylene Push-to-Connect Union Fitting,” The Home Depot Canada. Accessed: Nov. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.homedepot.ca/product/john-guest-1-4-in-polypropylene-push-to-connect-union-fitting/1001830380.

- “SharkBite ProLock 1/2 inch Push-to-Connect Plastic Slip Coupling Fitting,” The Home Depot Canada. Accessed: Nov. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.homedepot.ca/product/sharkbite-prolock-1-2-inch-push-to-connect-plastic-slip-coupling-fitting/1001833994.

- “SharkBite Max 1/2 inch Brass Push-to-Connect Straight Coupling,” The Home Depot Canada. Accessed: Nov. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.homedepot.ca/product/sharkbite-max-1-2-inch-brass-push-to-connect-straight-coupling/1000791803.

- “Polypropylene, Philmac & Water Line Compression Fittings | IPEX Inc.,” IPEX. Accessed: Nov. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ipexna.com/solutions/municipal-solutions/water-service-systems/philmac-compression-fittings/.

- “1/2" Brass Push-Fit Coupling.” Accessed: Nov. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://kent.ca/en/1-2-brass-push-fit-coupling-1006411.

- Blokus-Dziula, A.; Dziula, P.; Kamedulski, B.; Michalak, P., “Operation and Maintenance Cost of Water Management Systems: Analysis and Optimization,” Water, vol. 15, no. 17, Art. no. 17, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gwamuri, J.; Wittbrodt, B.T.; Anzalone, N.C.; Pearce, J.M., “Reversing the Trend of Large Scale and Centralization in Manufacturing: The Case of Distributed Manufacturing of Customizable 3-D-Printable Self-Adjustable Glasses,” Chall. Sustain., vol. 2, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Srai, J.S.; Graham, G.; Hennelly, P.; Phillips, W.; Kapletia, D.; Lorentz, H., “Distributed manufacturing: a new form of localised production?,” Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag., vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 697–727, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sells, E.; Bailard, S.; Smith, Z.; Bowyer, A.; Olliver, V., “RepRap: The Replicating Rapid Prototyper: Maximizing Customizability by Breeding the Means of Production,” in Handbook of Research in Mass Customization and Personalization, World Scientific Publishing Company, 2009, pp. 568–580. [CrossRef]

- Jones, R. et al., “RepRap – the replicating rapid prototyper,” Robotica, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 177–191, Jan. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Bowyer, A., “3D Printing and Humanity’s First Imperfect Replicator,” 3D Print. Addit. Manuf., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 4–5, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Romero, L.; Guerrero, A.; Espinosa, M.M.; Jiménez, M.; Domínguez, I.A.; Domínguez, M., “Additive Manufacturing with RepRap Methodology: Current Situation and Future Prospects,” 2014, Accessed: May 11, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://hdl.handle.net/2152/88735.

- Salmi, M., “Comparing additive manufacturing processes for distributed manufacturing,” IFAC-Pap., vol. 55, no. 10, pp. 1503–1508, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.S.; Gilbert, S.W., “Costs and Cost Effectiveness of Additive Manufacturing,” National Institute of Standards and Technology, NIST SP 1176, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Durão, L.F.C.S.; Christ, A.; Anderl, R.; Schützer, K.; Zancul, E., “Distributed Manufacturing of Spare Parts Based on Additive Manufacturing: Use Cases and Technical Aspects,” Procedia CIRP, vol. 57, pp. 704–709, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Wittbrodt, B.T. et al., “Life-cycle economic analysis of distributed manufacturing with open-source 3-D printers,” Mechatronics, vol. 23, no. 6, pp. 713–726, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, E.E.; Pearce, J., “Emergence of Home Manufacturing in the Developed World: Return on Investment for Open-Source 3-D Printers,” Technologies, vol. 5, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.; Qian, J.-Y., “Economic Impact of DIY Home Manufacturing of Consumer Products with Low-cost 3D Printing from Free and Open Source Designs,” Eur. J. Soc. Impact Circ. Econ., vol. 3, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M., Open-Source Lab: How to Build Your Own Hardware and Reduce Research Costs. Elsevier, 2013.

- Coakley, M.; Hurt, D.E., “3D Printing in the Laboratory: Maximize Time and Funds with Customized and Open-Source Labware,” J. Lab. Autom., vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 489–495, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M., “Economic savings for scientific free and open source technology: A review,” HardwareX, vol. 8, p. e00139, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M., “Distributed Manufacturing of Open Source Medical Hardware for Pandemics,” J. Manuf. Mater. Process., vol. 4, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.L.; Zacharias, L.R.; Cota, V.R., “Open-source hardware to face COVID-19 pandemic: the need to do more and better,” Res. Biomed. Eng., vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 127–138, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.H.; Liu, P.; Mokasdar, A.; Hou, L., “Additive manufacturing and its societal impact: a literature review,” Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol., vol. 67, no. 5, pp. 1191–1203, Jul. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.; Moon, S.K.; Hwang, J., “Design for additive manufacturing in customized products,” Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf., vol. 16, no. 11, pp. 2369–2375, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; A. K. Mohanty; Misra, M., “Additive manufacturing technology of polymeric materials for customized products: recent developments and future prospective,” RSC Adv., vol. 11, no. 58, pp. 36398–36438, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.; Blair, C.M.; Laciak, K.; Andrews, R.; Nosrat, A.; Zelenika-Zovko, I., “3-D Printing of Open Source Appropriate Technologies for Self-Directed Sustainable Development,” J. Sustain. Dev., vol. 3, no. 4, Art. no. 4, Nov. 2010. [CrossRef]

- ilkinson, S.; Cope, N., “Chapter 10 - 3D Printing and Sustainable Product Development,” in Green Information Technology, M. Dastbaz, C. Pattinson, and B. Akhgar, Eds., Boston: Morgan Kaufmann, 2015, pp. 161–183. [CrossRef]

- Gwamuri, J.; Pearce, J.M., “Open source 3D printers: an appropriate technology for building low cost optics labs for the developing communities,” in 14th Conference on Education and Training in Optics and Photonics: ETOP 2017, SPIE, Aug. 2017, pp. 550–563. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.I.; Wilson, D.; Gomez-Kervin, E.; Rosson, L.; Long, J., “EcoPrinting: Investigation of Solar Powered Plastic Recycling and Additive Manufacturing for Enhanced Waste Management and Sustainable Manufacturing,” in 2018 IEEE Conference on Technologies for Sustainability (SusTech), Long Beach, CA, USA: IEEE, Nov. 2018, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R.; Rab, S., “Role of additive manufacturing applications towards environmental sustainability,” Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res., vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 312–322, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Muth, J.; Klunker, A.; Völlmecke, C., “Putting 3D printing to good use—Additive Manufacturing and the Sustainable Development Goals,” Front. Sustain., vol. 4, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Romani, A.; Rognoli, V.; Levi, M., “Design, materials, and extrusion-based additive manufacturing in circular economy contexts: from waste to new products,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 13, 2021. [CrossRef]

- King, D.L.; Babasola, A.; Rozario, J.; Pearce, J.M., “Mobile Open-Source Solar-Powered 3-D Printers for Distributed Manufacturing in Off-Grid Communities,” Chall. Sustain., vol. 2, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Gwamuri, J.; Franco, D.; Khan, K.Y.; Gauchia, L.; Pearce, J.M., “High-Efficiency Solar-Powered 3-D Printers for Sustainable Development,” Machines, vol. 4, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Baechler, C.; DeVuono, M.; Pearce, J.M., “Distributed recycling of waste polymer into RepRap feedstock,” Rapid Prototyp. J., vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 118–125, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, F.; Lanza, S.; Boudaoud, H.; Hoppe, S.; Camargo, M., “Polymer Recycling and Additive Manufacturing in an Open Source Context: Optimization of Processes and Methods,” 2015, Accessed: May 11, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://hdl.handle.net/2152/89441.

- Woern, A.L.; McCaslin, J.R.; Pringle, A.M.; Pearce, J.M., “RepRapable Recyclebot: Open source 3-D printable extruder for converting plastic to 3-D printing filament,” HardwareX, vol. 4, p. e00026, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Pearce, J.M., “Tightening the loop on the circular economy: Coupled distributed recycling and manufacturing with recyclebot and RepRap 3-D printing,” Resour. Conserv. Recycl., vol. 128, pp. 48–58, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Price, A.J.N.; Capel, A.J.; Lee, R.J.; Pradel, P.; Christie, S.D.R., “An open source toolkit for 3D printed fluidics,” J. Flow Chem., vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 37–51, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- OpenSCAD; OpenSCAD · openscad/openscad. (Feb., 2021). C++, C. Accessed: Sep. 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/openscad/openscad/releases/tag/openscad-2021.01.

- Schlatter, A.; adrianschlatter/threadlib. (Aug., 2024). OpenSCAD. Accessed: Aug. 28, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/adrianschlatter/threadlib.

- “Design, manufacturing, and economic analysis of parametric open-source 3-D printed easy connect pipe fittings,” Oct. 2024, Accessed: Oct. 08, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://osf.io/fqjxe/.

- “Releases · prusa3d/PrusaSlicer,” GitHub. Accessed: Jul. 01, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/prusa3d/PrusaSlicer/releases.

- “Standard, A. S. T. M. F2164-13, Standard Practice for Field Leak Testing of Polyethylene (PE) and Crosslinked Polyethylene (PEX) Pressure Piping Systems Using Hydrostatic Pressure. Plastic Pipe Institute.”.

- “2024 Uniform Plumbing Code.” Accessed: May 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://epubs.iapmo.org/2024/UPC/.

- “PolyLiteTM PLA,” Polymaker CA. Accessed: Nov. 07, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ca.polymaker.com/products/polylite-pla.

- “PolyLiteTM PETG,” Polymaker CA. Accessed: Nov. 07, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ca.polymaker.com/products/polylite-petg.

- “PolyLiteTM ASA,” Polymaker CA. Accessed: Nov. 07, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ca.polymaker.com/products/polylite-asa.

- “Black Standard TPE85A Filament 1.75mm,” 3D Printing Canada. Accessed: Nov. 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://3dprintingcanada.com/products/black-1-75mm-tpe-filament-0-5-kg.

- “Original Prusa XL Semi-assembled Single-toolhead 3D Printer | Original Prusa 3D printers directly from Josef Prusa,” Prusa3D by Josef Prusa. Accessed: Nov. 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.prusa3d.com/product/original-prusa-xl/#specs.

- “Electricity rates | Ontario Energy Board.” Accessed: Nov. 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.oeb.ca/consumer-information-and-protection/electricity-rates.

- Mayville, P.J.; Petsiuk, A.L.; Pearce, J.M., “Thermal Post-Processing of 3D Printed Polypropylene Parts for Vacuum Systems,” J. Manuf. Mater. Process., vol. 6, no. 5, Art. no. 5, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- “2018 INTERNATIONAL RESIDENTIAL CODE (IRC) | ICC DIGITAL CODES.” Accessed: May 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://codes.iccsafe.org/content/IRC2018P7/chapter-29-water-supply-and-distribution.

- Fudholi, A.; Sopian, K.; Yazdi, M.H.; Ruslan, M.H.; Ibrahim, A.; Kazem, H.A., “Performance analysis of photovoltaic thermal (PVT) water collectors,” Energy Convers. Manag., vol. 78, pp. 641–651, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Dubey; Tay, A.A.O., “Testing of two different types of photovoltaic–thermal (PVT) modules with heat flow pattern under tropical climatic conditions,” Energy Sustain. Dev., vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 1–12, Feb. 2013. [CrossRef]

- “Drip Irrigation Design Guide-Determining Your Water Source Flow Rate & Pressure,” Irrigation Direct Canada. Accessed: May 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.irrigationdirect.ca/2008-drip-irrigation-design-guide-determining-your-water-source-flow-rate-and-pressure.html.

- Sanchez, F.A.C.; Boudaoud, H.; Camargo, M.; Pearce, J.M., “Plastic recycling in additive manufacturing: A systematic literature review and opportunities for the circular economy,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 264, p. 121602, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Romani, A.; Perusin, L.; Ciurnelli, M.; Levi, M., “Characterization of PLA feedstock after multiple recycling processes for large-format material extrusion additive manufacturing,” Mater. Today Sustain., vol. 25, p. 100636, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, F.A.C.; Boudaoud, H.; Hoppe, S.; Camargo, M., “Polymer recycling in an open-source additive manufacturing context: Mechanical issues,” Addit. Manuf., vol. 17, pp. 87–105, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Vidakis, N. et al., “Sustainable Additive Manufacturing: Mechanical Response of Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol over Multiple Recycling Processes,” Materials, vol. 14, no. 5, Art. no. 5, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- “Ipex Philmac 3/4-in ID Quick Disconnect Compression Coupling.” Accessed: Nov. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.rona.ca/en/product/ipex-philmac-3-4-in-id-quick-disconnect-compression-coupling-358101-00685560.

| Thread Type | Range | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Metric Threads | M0.25 to M600 | Coarse, fine, and super-fine pitches |

| Unified Inch Screw Threads (UNC, UNF, UNEF) | Various (UNC, UNF, UNEF) including 4-UN, 6-UN, 8-UN, 12-UN, 16-UN, 20-UN, 28-UN, and 32-UN | All threads are class 2 threads |

| BSP Parallel Thread (G) | G1/16 to G6 | All threads are class A threads |

| PCO-1881 and PCO-1810 | Specific to PET-bottle threads | N / A |

| Royal Microscopical Society's Thread (RMS) | Typical RMS | N / A |

| N. | Input name | Range | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | input_dia | Primary | The diameter of the input pipe being fit. | |

| 2 | gasket_thickness_upper | Primary | Upper bound on desired gasket thickness. | |

| 3 | gasket_thickness_lower | Primary | Lower bound on desired gasket thickness. | |

| 4 | gasket_extra_length | Secondary | Additional length added to the end of the gasket such that the cap nut compresses it when assembled. | |

| 5 | tol_pipe | Secondary | Tolerance between the pipe and the fitting. | |

| 6 | tol_gasket | Secondary | Tolerance between the pipe and the gasket. | |

| 7 | turns | Secondary | Number of turns for the adapter threading. | |

| 8 | wall_thickness | Secondary | Thickness of the fitting walls. | |

| 9 | middle_length | Secondary | Length of the middle pipe of the fitting. | |

| 10 | transition_length | Secondary | Length of the transition from the middle pipe to the adapter threading begins. | |

| 11 | cap_thickness | Secondary | Thickness of the cover part of the cap nut. | |

| 12 | nut_wall_thickness | Secondary | Thickness of the cap nut walls. | |

| 13 | entry_chamfer | True or false | Secondary | Chamfer around the entry lip of the adapter threads. |

| 14 | style | String input | Secondary | Available options: "Hexagon", "Cone", or "Circular". |

| 15 | selectedThread | Integer | Derived | The desired adapter thread the user wishes to export, must be in range of possibilities. |

| 16 | export | True or false | Utility | Set to true to remove all design possibilities and only display the selected one. |

| 17 | selectedPart | String input | Utility | Available options: "fitting", "nut", "gasket", or "all" to select objects for export. |

| Steps | Parameters (Input Name) |

Unit | Batch 1 (10 mm Diameter) |

Batch 2 (20 mm Diameter) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customization (OpenSCAD) | Input diameter (input_dia) | mm | 10 | 20 | ||||

| Gasket thickness up (gasket_thickness_upper) | mm | 17 | 19 | |||||

| Gasket thickness low (gasket_thickness_lower) |

mm | 15 | 15 | |||||

| Gasket extra length (gasket_extra_length) |

mm | 6 | 8 | |||||

| Tolerance pipe (tol_pipe) | mm | 0.5 | 0.5 | |||||

| Tolerance gasket (tol_gasket) | mm | 0.1 | 0.1 | |||||

| Number of turns (turns) | // | 5 | 5 | |||||

| Wall thickness (wall_thickness) |

mm | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Lower length (middle_length) | mm | 12 | 12 | |||||

| Mid height (middle_length) | mm | 5 | 7 | |||||

| Cap thickness (cap_thickness) | mm | 3 | 4 | |||||

| Nut wall thickness (nut_wall_thickness) |

mm | 4 | 6 | |||||

| Entry chamfer (entry_chamfer) | // | enabled | Enabled | |||||

| External cross-section style (style) | // | hexagon | Hexagon | |||||

| Selected thread (selectedthread) |

// | 5 | 5 | |||||

| 3D printing (Prusa slicer) | Materials | // | PETG | PLA | ASA | TPE | PETG | TPE |

| 3D printer (Prusa) | // | XL | MK3S | XL | MK3S | |||

| Nozzle diameter | mm | 0.4 | 0.4 | |||||

| Extruder temperature | °C | 240 | 215 | 260 | 230 | 240 | 230 | |

| Bed temperature | °C | 80 | 60 | 105 | 50 | 80 | 50 | |

| Speed | mm/s | 65 | 30 | 65 | 30 | |||

| Infill (Type) | // | Rectilinear | Rectilinear | |||||

| Infill (Overlap) | % | 20 | 20 | |||||

| Infill (Percentage) | % | 100 | 100 | |||||

| Flow (Percentage)a | % | 115-110 | 115-110 | 110-100 | 10 | 110-100 | 100 | |

| Layer height | mm | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.15 | 0.2 | |||

| Perimeters | // | 6 | 4 | 6 | 4 | |||

| Adhesiona | // | Brim - none | Brim | Brim - none | Brim | |||

| Custom Design | Material | Parts | Material | Weight (Nominal) | Weight (Measured) | Time | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch | Unit | // | // | g | g | min | CAD |

| Batch 1 (10 mm diameter) | PLA | Pipe fitting (x1 main body) |

PLA | 12,2 | 10,3 | 82 | 0.31 |

| Nut (x2 parts) | PLA | 21,4 | 20,2 | 61 | 0.58 | ||

| Gasket (x2 parts) | TPE | 3,9 | 3,2 | 45 | 0.15 | ||

| Total assembly | // | 37,5 | 33,7 | 188 | 1.03 | ||

| PETG | Pipe fitting (x1 main body) |

PETG | 11,7 | 10,6 | 80 | 0.32 | |

| Nut (x2 parts) | PETG | 20,4 | 19,7 | 98 | 0.58 | ||

| Gasket (x2 parts) | TPE | 3,9 | 3,2 | 45 | 0.15 | ||

| Total assembly | // | 36,0 | 33,5 | 223 | 1.04 | ||

| ASA | Pipe fitting (x1 main body) |

ASA | 10,1 | 8,4 | 113 | 0.35 | |

| Nut (x2 parts) | ASA | 17,6 | 16,2 | 94 | 0.65 | ||

| Gasket (x2 parts) | TPE | 3,9 | 3,2 | 45 | 0.15 | ||

| Total assembly | // | 31,6 | 27,8 | 252 | 1.15 | ||

| Batch 2 (20 mm diameter) | PETG | Pipe fitting (x1 main body) |

PETG | 28,3 | 29,0 | 146 | 0.85 |

| Nut (x2 parts) | PETG | 69,8 | 71,2 | 296 | 2.07 | ||

| Gasket (x2 parts) | TPE | 11,2 | 8,4 | 125 | 0.38 | ||

| Total assembly | // | 109,3 | 108,6 | 567 | 3.30 |

| Specifications | Vendor | Material | Pipe Diameter | Pressure Rating [psi] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rain Bird Easy Fit Compression Fitting [11] | RONA | ABS | 16-17 mm | 60 | 4.79 |

| John Guest Push-to-Connect Union Fitting [13] | Home Depot | Polypropylene | 1/4 inch | 150 | 5.13 |

| SharkBite ProLock Push-to-Connect Plastic Coupling [14] | Home Depot | Polymer | 1/2 inch | 160 | 13.16 |

| SharkBite Max Brass Push Coupling [15] | Home Depot | Brass | 1/2 inch | 250 | 13.68 |

| IPEX Philmac Quick Disconnect Compression Coupling [16,74] | RONA | polypropylene | 1/2 inch | 230 | 17.49 |

| Aqua-Dynamic 3/4" Brass Push-Fit Coupling [17] | KENT | Brass | 1/2 inch | 200 | 17.99 |

| SharkBite EvoPEX Connector Push-to-Connect [12] | Amazon.ca | Stainless Steel | 1/2 inch | 200 | 18.44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).