1. Introduction

Zeolites are amongst the most extensively explored crystalline porous materials due to their variable chemical composition, framework geometry, pore size, and tunability. Because of their high surface area, adsorption selectivity, and mechanical, biological, chemical, and thermal stability, these molecular sieves are widely used in adsorption, catalysis, ion exchange, and separation technology.

Porosity is a crucial feature of most zeolites, playing a pivotal role in many applications such as water purification, catalysis, and gas separation. This property controls the size and accessibility of the internal surface area, where important chemical interactions occur.

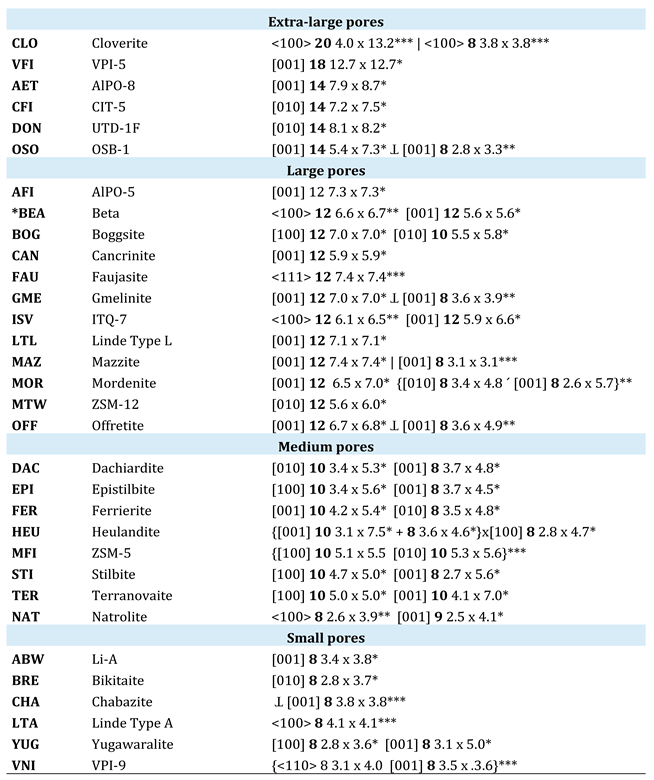

The simplest way to classify zeolites is by the number of tetrahedra that form their pore openings (see

Table 1). According to Flanigen et al. [

1], zeolites with

tiny pores have channels defined by 8-membered rings (8R) with diameters ranging from 3.5 to 4.5 Å (for example, gismondine).

Medium-pore zeolites contain 10-membered rings (10R) with apertures between 4.5 and 6 Å (such as ferrierite).

Large-pore zeolites are characterized by 12-membered rings (12R), with free diameters ranging from 6 to 8 Å (for instance, mordenite). Finally, zeolites with pore openings consisting of 14 or more membered rings (14+R) fall into the category of

extra-large pores (such as covert) [

2].

According to Catizzone et al. [

3], the characteristics of the zeolite channel system—including channel orientation and geometry, spatial connections, pore size, and presence of cages—are essential factors that influence their activity and selectivity in transformations of organic compounds. These features play a significant role in the diffusion processes within zeolites and affect the performance of zeolite catalysts. Increasing both channel dimensions and connectivity was thought to improve zeolite activity. Notably, zeolites with lower dimensionality in their channels exhibit more rapid deactivation. The shape selectivity property strongly depends on the zeolite structure: channels with different paths and shapes (e.g., sinusoidal or straight channels) and pore dimensions can limit or enhance the diffusion of host molecules, thus determining unique selectivity effects. Therefore, access to the framework voids is allowed only to species characterized by shapes and sizes comparable to the framework topology selected.

Figure 1.

Zeolites with channels mono, bi, and tri-directional.

Figure 1.

Zeolites with channels mono, bi, and tri-directional.

Micropores frequently restrict the diffusion of reactants and products to and from active sites due to their molecular dimensions. Shortening the diffusion route in voids improves transport and makes zeolites more efficient as catalysts. Attempts have been undertaken to introduce mesopores into zeolites to overcome the constraints of the zeolite framework in allowing large molecules (kinetic diameter 4-10 Å) [

4]. The intracrystalline mesoporosity can be achieved through templating, post-synthesis treatments (dealumination and desilication), or hydrothermal treatment using steam [

5,

6,

7]. The latter often involves temperatures above 500 °C and utilizes ammonium (or hydrogen) zeolites. As a result, the Si-O and Al-O bonds in the framework undergo hydrolysis, which greatly increases the mobility of aluminum and silicon species, leaving a void (hydroxyl nest) or partial amorphization. Combining micropores and mesopores in a single zeolite crystal can improve catalytic performance significantly [

8,

9]. Mesopores in zeolite crystals lead to shorter intracrystalline diffusion channel lengths and increased exterior surface area. Mesopores facilitate the efficient transport of reactants and products, while the micropores in zeolites contribute to shape-selective properties. The features of zeolites arise from structural confinement, resulting in an inherently confined system at the molecular scale. Significant effort has been devoted to exploring and employing this structural confinement to address two fundamental questions what causes the distinctive properties of zeolites and how they can be applied in innovative applications.

This short review highlights the significant progress achieved in leveraging the properties of zeolite materials for various applications, including gas separation and storage, adsorption, catalysis, chemical sensing, and biomedical applications. The aim is to emphasize their capabilities by showcasing significant milestones that have driven research in this field toward new and unexpected areas of material chemistry.

2. Zeolites for Sustainable Environmental Applications

To effectively control and optimize the properties of zeolites, it is crucial to understand their framework types, structural connectivity of tetrahedrally coordinated atoms, and crystal chemistry. The Si/Al ratio (SAR) of zeolites is a critical parameter affecting properties such as the maximum ion-exchange capacity, thermal and hydrothermal stability, hydrophobicity, concentration, and strength of Bronsted-type acid sites, along with catalytic activity and selectivity (

Figure 2).

Zeolites with high SAR exhibit higher thermal stability reaching temperatures as high as 1300 °C, and lower dehydration temperatures, due to their surfaces becoming more hydrophobic [

10,

11,

12,

13]. The selective adsorption capability alongside the size and shape of the pores and channels through which host molecules diffuse. Consequently, zeolites can act like molecular sieves, meaning that when a mixture containing two components differing in shape and size flows through the zeolite channels, the different components can be successfully separated.

2.1. Zeolites for Inorganic Contaminants Removal

The SAR significantly impacts the ability to host water and extraframework cations [

14]. The high ion exchange capability and the selectivity of zeolites are vital for removing ammonia, heavy metals, and radionuclides from natural waters and wastewater. According to Jin et al. [

15], heavy metal adsorption initially involves the external surface of the particles, followed by the counter-diffusion of interchangeable cations, and finally the sorption in the microporosities of the zeolite. Zeolites such as X, Y, A, and P can achieve the removal of up to 96% of heavy metals, 90% of phosphoric compounds, 96% of dyes, 80% of nitrogen compounds (96% specifically for ammonium), and 89% of organic substances [

16,

17]. The sequestration of Hg, Cu, Cd, Zn, Cr, and Ni using natural zeolites like clinoptilolite and chabazite can be enhanced through iron coating or by utilizing nanoscale zero-valent iron combined with zeolite materials. Core-shell ZnO/Y particles are effective at enhancing lead uptake and have antibacterial properties. [

18]. Due to the similarity in size between metallic ions and the pores, the kinetics are fast, regardless of the type of zeolite or the heavy metal being removed.

Zeolites are radiologically stable and exhibit a strong affinity for radionuclides like

90Sr and

137Cs. Natural mordenite and clinoptilolite are effective in decontaminating nuclear power plant wastewater [

19]. Furthermore, all-silica zeolites are used to capture iodine released during the dissolution of nuclear fuel rods [

20,

21].

Recently, Kwon et al. [

22] investigated the efficiency of zeolites with both different framework topologies and Si/Al ratios, to carefully evaluate their sequestration capabilities for Cs

+ and Sr

2+ in simulated groundwater and seawater. The strong attraction of the Cs+ ion to zeolites with high Si/Al ratios can be explained through dielectric theory. The geometry and dimensions of zeolite openings are also significant in their ion-exchange capabilities. Zeolite frameworks containing 8-membered rings (8MR), such as LTA, GIS, CHA, and MOR, demonstrate exceptional selectivity for Cs+ compared to frameworks without 8MR units. This occurs because Cs

+ is likely to fit within the center of the 8MR units, and its ionic size (3.6 Å) is well matched to the size of these cavities, which range from 3.6 to 4.1 Å [

23]. On the other hand, zeolites with larger and more ellipsoidal cages, like chabazite, phillipsite, stilbite, and heulandite (with SAR, ranging from 2 to 3), tend to prefer larger cations, such as Cs over Na

+ or Sr

2+. Conversely, lower Si/Al ratios are crucial for enhancing the attraction to strontium ions, as this allows for the formation of Al-Al pairs that can effectively interact with strontium.

Moreover, zeolites with low Si/Al ratios can release extraframework sodium and calcium ions from their structure to sequester ammonium and potassium from soils (

Figure 3). This process reduces the leaching of nutrients from the soil and enhances the recovery of insoluble phosphorus from agricultural fields, promoting a more sustainable and healthier farming environment. Zeolites exhibiting a high Si/Al ratio possess fewer sites available for exchange, a lower electric field gradient, and a reduced level of hydration [

1]. In these materials, the ion exchange capacity is strongly related to defect sites (SiO

-) and the framework-terminating Si-OH groups.

2.2. Zeolites for the Removal of Organic Contaminants

Zeolites are pivotal in environmental remediation efforts, contributing to outdoor air quality monitoring, as well as the purification of water and wastewater by efficiently removing cationic species, including ammonium, heavy metals, rare-earth cations, radioactive species, and various organic pollutants [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. It has been noted that the zeolites' adsorption is strongly affected by their composition and structural features. Factors such as pore window size, internal pore volume, and steric hindrance are crucial in determining adsorption selectivity. Medium-pore zeolites, including ZSM-5 and ferrierite, exhibit exceptional efficiency in removing volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and organic molecules of moderate size, from dilute aqueous solutions [

31,

32]. Conversely, zeolite Y demonstrates noteworthy adsorption capabilities for larger molecules, especially drugs [

32,

33,

34] (

Figure 3).

Recent studies focused on the effectiveness of 13X and ZSM-5 adsorbent materials have been undertaken in the industrial area of Tito Scalo, located in the Basilicata Region of Southern Italy, specifically focusing on removing heavy metals and VOCs from polluted water. The results revealed that ZSM-5 demonstrated remarkable efficacy in the removal VOCs, specifically 1,2-dichloroethylene and trichloroethylene, achieving removal efficiencies exceeding 87%. On the other hand, 13X zeolite exhibited remarkable selectivity for the in situ abatement of heavy metals, with efficiencies reaching up to 100%. These noteworthy findings suggest that a sequential filtration system using both ZSM-5 and 13X zeolites could function as a highly effective adsorption method for the remediation of groundwater contaminants, similar to the functionality of Permeable Reactive Barriers [24; 35].

Zeolites have emerged as a focal point in the research aimed at reducing emerging contaminants in aqueous environments, including pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and perfluorinated compounds (PFAS) [

36]. Previous investigations have shown that some monomers of humic acids possess the ability to compete with these contaminants for adsorption sites on zeolites [

37]. This competition is made more complex by the potential for complex interactions between organic contaminants and naturally dissolved organic matter, which can significantly influence the adsorption process [

38]. Recently, an investigation was conducted to assess the impact of humic monomers, specifically vanillin and caffeic acid, on the adsorption of sulfamethoxazole by high-silica zeolite Y [

39,

40,

41]. The results indicated that the adsorption of caffeic acid was minimal and did not significantly affect the adsorption of sulfamethoxazole within a pH range of 5 to 8. However, more recent studies have revealed that caffeic acid concentrations below 20 mg L

−1 can enhance the adsorption of sulfonamide antibiotics on ZSM-5 at a pH of 9 [

39].

It is also crucial to consider that these substances frequently coexist with a variety of other contaminants in both natural and wastewater systems, i.e. per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). PFAS are emerging contaminants that are gaining attention for their ubiquitous distribution, persistence, and toxicity in the environment and ecosystem. As regulatory frameworks become increasingly stringent regarding environmental and health standards for PFAS, adsorption is emerging as a promising technique to address these challenges effectively. Among the PFAS removal approaches, the adsorption from water and wastewater through porous materials has shown great effectiveness, albeit the PFOA and PFOS adsorption mechanisms are not yet completely understood. Zeolites differing in framework topology ((including FAU, LTL, BEA, MOR, CHA, and KFI) and SiO

2/Al

2O

3 have been evaluated for several types of PFAS (i.e. PFCAs, PFSA, FTSAs, and FOSA) [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. Several factors, including the perfluoroalkyl chain length, the presence of functional groups, and the molecular size, influence the adsorption capacity of individual PFAS. Other key factors affecting the affinity of zeolite for PFAS include the SAR, the nature of tetrahedral cations, the occurrence of silanol groups, the zeolite hydrophobicity, and any post-synthesis modifications like ion exchange and ammonium fluoride treatments. [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47].

PFASs were recently removed from different polluted waters (untreated water from drinking water facilities, wastewater discharges from processing plants, leachate from landfills, and groundwater from waste sites) in Uppsala, Sweden. The results indicated that zeolite Beta (SAR=25) and mordenite (SAR=240) demonstrated absorption capacities of 99.5% and 99.2%, respectively [

42]. The ability of these materials to absorb individual PFAS was affected by several factors including the length of the perfluoroalkyl chain, the presence of functional groups, and the molecular size. Furthermore, it has been suggested that modifying the most effective zeolites with silver could help prevent biofilm formation while improving antifouling and adsorption capabilities in wastewater treatment processes. Notably, silver-functionalized zeolites demonstrated superior PFAS uptake capacities, indicating that silver functionalization may facilitate catalytic reactions in the degradation of PFAS [

44].

Zeolite membranes can remove salts and oils from water, offering an alternative to reverse osmosis membranes. Natural zeolite membranes, like heulandite and clinoptilolite show high rejection rates for metal cations and toluene in synthetic seawater.

Zeolite-coated mesh films, such as those made with silicalite-1, achieve efficient gravity-driven oil-water separation thanks to their super hydrophilicity and underwater superoleophobicity [

48,

49]. Composite zeolite-polymeric membranes (like polysulfone, polyethersulfone, polyacrylonitrile, polyvinylidene fluoride, alcohol/agar, and cellulose acetate) result in a powerful mix of mechanical toughness, chemical stability, flexibility, adsorption ability, selectivity, and surface area. [

50,

51]. Recent studies highlight the great potential of zeolite/activated carbon composites in water treatment technologies. These composites are highly effective at trapping heavy metals and dyes from water because of the tiny pore sizes of zeolites, while the multilayer structure of activated carbon facilitates the absorption of larger molecules [

53]. Increased amounts of graphene oxide greatly improve dye decolorization. Additionally, a new hybrid magnetic composite combining zeolite and graphene oxide has successfully adsorbed 97.346 mg/g of methylene blue dye [

54].

Lastly, the development of a water purification membrane made of zeolite, graphene oxide, and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) demonstrates outstanding water permeability at 28.9 L/m²/h and a remarkable desalination efficiency of 98% [

55]. These cutting-edge innovations are leading towards a cleaner and more sustainable future for water treatment.

2.3. Zeolites for CO2 Capture and Storage

Zeolites with FAU-type topology (i.e. 13X, 4A, and NaY) have been investigated for their ability to capture and retain CO

2 concentrations from 400 ppm to 20–30% [

56]. The trapping mechanism involves both reversible physical adsorption and irreversible chemical adsorption. Typically, zeolites display moderate adsorption capacities (1–7 mmol g

–1) at low pressure (1 bar) and elevated temperatures. Surface modification of zeolites through acid treatment increases performance by raising the number of acid sites on their surfaces. Moreover, the rate of CO

2 adsorption can be increased through amine-functionalization (i.e. involving mono-ethanolamine, diethanolamine, and triethanolamine) due to the chemical reactions between the –NH

2 functional group, CO

2 molecules, and the active sites of the zeolites. Amine grafting is a chemical method that increases CO

2 uptake by promoting interactions between CO2 and amine groups and improving the zeolites' surface area and porosity. The CO

2 adsorption performance can be further enhanced by ion exchange with Li

+, H

+, NH

4+, Ba

2+, Mg

2+, Ca

2+, and Fe

3+, which modifies the surface properties and structure of the zeolite. For large and medium-pore zeolites, the spatial constraints are usually negligible because the molecular dimensions of CO

2 are considerably smaller than the window apertures. Here, the adsorption capacity and selectivity are mainly influenced by the interactions between CO

2 and the cations. For example, the CO

2 adsorption capacity of 13X is enhanced after Li-loading as the smaller atomic size and higher basicity of lithium lead to stronger ion-quadrupole interactions in comparison to larger cations like Na

+, K

+, Rb

+, and Cs

+.

This is clearly illustrated by the "

molecular trapdoor/cation gating" and "

gate breathing" effects observed in high-aluminum RHO-type, CHA-type, GIS-type, and MER-type zeolites [

57,

58]. These phenomena can lead to significantly enhanced selectivity for CO2/N2 and CO2/CH4, highlighting the complex relationship between zeolite structure and gas adsorption behavior. For example, zeolites like EDI, FER, and ISV show about 5% in terms of electrostatic interaction, while structures like GIS, MER, MOR, and RHO reveal interactions exceeding 15% [

57]. Membranes based on small-pore zeolites (with 8-membered rings, or 8MR) are being actively studied for their capabilities in separating light gases because their pore sizes are ideally suited for accommodating various light gases. Key examples of 8MR zeolites applied in catalysis, adsorption, and membrane separation include DDR (3.6 × 4.4 Å), LTA (4.1 × 4.1 Å), CHA (3.8 × 3.8 Å), ERI (3.6 × 5.1 Å), and MER (3.4 × 5.1 Å) [

57]. Natural clinoptilolite, particularly when exchanged with alkali and alkaline earth cations (following order of effectiveness: Cs

+ > Rb

+ > K

+ > Na

+ > Li

+ and Ba

2+ > Sr

2+ > Ca

2+ > Mg

2+), emerges as an up-and-coming candidate for CO

2 uptake due to its adsorption capacity, widespread availability, and economic viability [

58,

59,

60].

2.4. Zeolites for Catalytic Processes

Despite all the new fields of applications, in the 1960s, catalysis in the petrochemical sector continues to be the main domain where zeolites are utilized extensively due to their remarkable capability to enhance catalytic processes [

3]. Specifically, the possibility to modify both the type and location of extraframework cations as well as the incorporation of framework heteroatoms, allows changes in the selectivity and catalytic activity of zeolites [

61]. Zeolite-supported metal catalysts facilitate the formation of ultrasmall and remarkably stable metal species, contributing to their exceptional thermal and hydrothermal stability during catalytic reactions, particularly in challenging environments. Additionally, they exhibit unique shape-selectivity, which improves their performance in a wide range of catalytic activities. In heterogeneous catalysis, these materials favored several important reactions, such as hydrogenation of CO and CO

2, dehydrogenation, oxidation, selective catalytic reduction of NOx using ammonia (NH

3-SCR), and hydroisomerization. Nickel and cerium-zeolites (i.e. MFI, BEA, FAU, MOR, ITE) are efficient catalysts for converting CO

2 to methane, because the presence of oxygen vacancies in CeO

2 species enhances the activation of CO

2 and increased the dispersion of Ni species [

61,

62,

63]. Not only rare earth and noble metal-supported zeolites (Pd, Ru, and Rh) but also alkali and alkaline metal ions (Li, Na, K, Cs, Ba, Ca, Mg) enhance the CO

2 adsorption and activation. Their unique properties (i.e. excellent selectivity, long-term stability, and recyclability) not only improve reaction outcomes but also pave the way for more sustainable and efficient chemical processes.

Indeed, the presence of hydroxyl Si-OH-Al groups (Brønsted acid sites, BAS) along with the insertion of tri- or tetravalent heteroatoms within the framework sites confer enhanced catalytic properties. Similarly, extra-framework aluminum species have also been reported to act as a Lewis acid site (LAS). BAS and LAS in zeolites are extensively explored key roles in many biomass conversion processes. For example, Brønsted acidic zeolites with large pores facilitate the conversion of lactic acid (LA) into lactide, as well as catalyze condensation reactions. Zeolite H-Beta demonstrates remarkable selectivity in the synthesis of lactide, achieving a yield of approximately 79% at full conversion of LA. Additionally, zeolites with large and medium pores zeolites may also serve as catalysts for the oxidation of bioethanol to acetaldehyde, or in the conversion of sugar-based 2,5-dimethylfuran to aromatic compound. Indeed, the channels of high dimensions together with the presence of additional supercages, render large pores zeolites suitable for large-scale processes such as the fluid catalytic cracking of oil for gasoline production and transalkylation in the refinery processes. Furthermore, medium pore zeolites are widely used as hydrocracking catalysts in processes that necessitate greater shape-selectivity towards organic compounds, including olefin isomerization, dewaxing in refineries, xylene isomerization [64 and references therein]. LAS are most extensively evaluated for alkene epoxidation, Baeyer−Villiger oxidation of ketones and aromatic aldehydes, alcohol dehydration, and conversion of sugars, furan, and acid derivatives. The combination of LAS with additional functional sites (for example, Brønsted acid sites, metal sites, and alkaline sites) could open new possibilities for producing high-value chemicals or fuels from biomass-derived oxygenates.

2.5. Zeolites in Bioprocessing Applications

In the last years, the potential of zeolites for recovering amino acids from fermentation broths, underscoring their practical relevance in bioprocessing was reported [

65,

66,

67]. Zeolites used as sorbent media for α-aminoacids adsorption usually belong to medium and large pores. The affinity between the sorbents and α-aminoacids strongly depends on their net charge, which can vary from positive/neutral to negative in water solutions [

68,

69], along with occurring host-guest interactions. The uptake of amino acids is mainly influenced by the electrostatic interactions between the positively charged ammonium group of the amino acids and the negatively charged surface of the zeolite [

70]. This fundamental interaction forms the basis for the binding process. Additionally, the hydrophobic interactions arising from the non-polar side chains of the adsorbed amino acid molecules further enhance the overall binding mechanism. These ionic and hydrophobic interactions synergistically aid adsorption, providing insights into how amino acids interact with zeolite surfaces. [

70,

71]. The intricate interplay between these forces is crucial for comprehending the mechanisms that control adsorption, making it a significant topic in material science and biochemistry. Notably, Beltrami et al. [

71] demonstrated that when L-lysine is adsorbed onto L zeolite, it adopts an α-helical conformation, which is stabilized by strong hydrogen bonds formed between the terminal amino groups of lysine, co-adsorbed water, and the oxygen atoms in the zeolite framework.

Furthermore, investigations by Chen et al. [

72,

73] on achiral MFI zeolites have shown that these materials exhibit differential adsorption properties for the L- and D-Lys enantiomers in acidic solutions (pH < 2). This finding suggests that achiral zeolites may be applicable for chiral separations, thereby expanding their applications in biochemical separation processes. Furthermore, zeolites are increasingly recognized for their significance in the medical and biotechnological fields. From a medical perspective, zeolites enhance livestock's nutritional status and immune response while serving as detoxifying agents for humans and animals [

74,

75,

76,

77]. This multifaceted utility underscores the vital role that zeolites play in advancing sustainable technologies, i.e., in detecting biomarkers, controlled drug and gene delivery, tissue engineering, biomaterial coating, and separation of cells and biomolecules [

78,

79,

80].

3. Conclusions

Zeolites are crystalline microporous materials extensively studied because of their distinctive features, including shape selectivity, adsorption, ion exchange ability, and low manufacturing costs. Due to their extensive surface area and stability in mechanical, biological, chemical, and thermal processes, these molecular sieves are utilized not just in conventional processes (petrochemical, coal chemical industries, separation, adsorption) but also as catalysts for the conversion of greenhouse gases (CO2 and CH4) and biomass. Multifunctional zeolites, which combine Brønsted and Lewis acid sites, improve the efficacy of multistep reactions, thus offering new approaches for generating high-value chemicals from biomass. Moreover, zeolites are utilized to produce hydrogen and methanol for fuel cells, providing outstanding membrane characteristics and selectivity, deserving of further investigation. Zeolites play a crucial role in generating hydrogen and methanol for fuel cells, functioning as membranes that inhibit methanol crossover while providing excellent selectivity and remarkable mechanical and thermal stability, justifying further investigation into this technology.

Zeolites can trap CO2 due to their powerful electric fields and transform them into fuels and chemicals, demonstrating excellent selectivity and stability.

Zeolite-water adsorption systems can store and release energy, making them useful for solar energy applications and industrial waste heat storage. By coating zeolites onto a metallic bed, heat, and mass transfer efficiency are enhanced, and the adsorption system is made more compact and lasts longer. Zeolite composites can be used efficiently to eliminate heavy metals and dyes in water purification, providing a cost-effective solution enhancing soil fertility and agricultural practices through their cation exchange properties.

Furthermore, zeolites decrease air pollutants by reducing NOx and NH3 emissions and turning volatile organic compounds into harmless byproducts, although there are still issues with emissions treatment.

Despite significant advancements, the application of zeolites in sustainable processes can still be further enhanced. Primary objectives include enhancing catalyst selectivity, reducing expenses, and evaluating the economic viability of novel zeolites. With nearly a century of substantial history, the future for zeolitic research and its applications appears promising.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, M.M. and A.M.; validation, M.M. and A.M.; investigation, M.M. and A.M.; resources, A.M.; data curation, M.M. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M. and A.M.; writing—review and editing, M.M. and A.M.; visualization, M.M. and A.M.; supervision, A.M.; funding acquisition, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 04 Component 2 Investment 1.5 – NextGenerationEU, call for tender n. 3277 dated 30/12/2021, Award Number: 0001052 dated 23/06/2022.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Flanigen, E. M. Zeolites, and molecular sieves: a historical perspective. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 2001, 137, 11-35. [CrossRef]

- Casci, J. L. Zeolite molecular sieves: preparation and scale-up. Microporous and Mesoporous Mater. 2005, 82(3), 217-226. [CrossRef]

- Catizzone, E.; Aloise, A.; Migliori, M.; & Giordano, G. From 1-D to 3-D zeolite structures: Performance assessment in catalysis of vapor-phase methanol dehydration to DME. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat., 2017, 243, 102-111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2017.02.022. [CrossRef]

- Corma, A. State of the art and future challenges of zeolites as catalysts. J. Catal. 2003, 216(1-2), 298-312. [CrossRef]

- Van Donk, S.; Janssen, A. H.; Bitter, J. H.; de Jong, K. P. Generation, characterization, and impact of mesopores in zeolite catalysts. Catal. Rev. Sci. Eng. 2003, 45(2), 297-319. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Liu, X.; Yu, L.; Miao, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Xie, S.; Xu, L. Preparation of hierarchical mordenite zeolites by sequential steaming-acid leaching-alkaline treatment. Microporous and Mesoporous Mater. 2014, 191, 18-26. [CrossRef]

- Mancinelli, M.; Precisvalle, N.; Ardit, M.; Beltrami, G.; Gigli, L.; Catizzone, E.; Migliori, M.; Giordano, G.; Martucci, A. Thermal stability of templated ZSM-5 zeolites: An in-situ synchrotron X-ray powder diffraction study. Microporous and Mesoporous Mater. 2023, 362, 112777. [CrossRef]

- Corma, A. From microporous to mesoporous molecular sieve materials and their use in catalysis. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97(6), 2373-2420. [CrossRef]

- Velty, A.; Corma, A. Advanced zeolite and ordered mesoporous silica-based catalysts for the conversion of CO2 to chemicals and fuels. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52(5), 1773-1946. [CrossRef]

- Alberti, A.; Martucci, A. Phase transformations and structural modifications induced by heating in microporous materials. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 2005, 155, 19-43. [CrossRef]

- Alberti, A.; Martucci, A. Reconstructive phase transitions in microporous materials: Rules and factors affecting them. Microporous and Mesoporous Mater. 2011, 141(1-3), 192-19. [CrossRef]

- Cruciani, G. Zeolites upon heating: Factors governing their thermal stability and structural changes. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2006, 67(9-10), 1973-1994. [CrossRef]

- Bish, D. L.; Carey, J. W. Thermal behavior of natural zeolites. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2001, 45(1), 403-452. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Botella, E.; Valencia, S.; Rey, F. Zeolites in adsorption processes: State of the art and future prospects. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122(24), 17647-17695. [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Yang, Y.; Jin, J.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, F.; Shao., M; Wan, Y. Characterization of phosphate modified red mud–based composite materials and study on heavy metal adsorption. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024 31, 43687–43703. [CrossRef]

- Daer, S.; Kharraz, J.; Giwa, A.; Hasan, S. W. Recent applications of nanomaterials in water desalination: a critical review and future opportunities. Desalination 2015, 367, 37-48. [CrossRef]

- Swenson, P.; Tanchuk, B.; Bastida, E.; An, W.; Kuznicki, S. M. Water desalination and de-oiling with natural zeolite membranes—Potential application for purification of SAGD process water. Desalination 2012, 286, 442-446, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2011.12.008. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, L.; Yu, J. Applications of zeolites in sustainable chemistry. Chem. 2017, 3(6), 928-949. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Reyes, M.; Almazán-Sánchez, P. T.; Solache-Ríos, M. Radioactive waste treatments by using zeolites. A short review. J. Environ. Radioact. 2021, 233, 106610. [CrossRef]

- Riley, B. J.; Chong, S.; Schmid, J.; Marcial, J.; Nienhuis; Bera, M. K.; Lee, S.; Canfield, N. L.; Kim, S.; Derewinski, M. A.; Motkuri, R.K. Role of zeolite structural properties toward iodine capture: A head-to-head evaluation of framework type and chemical composition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022, 14(16), 18439-18452. [CrossRef]

- Pham, T. C. T.; Docao, S.; Hwang, I. C.; Song, M. K.; Moon, D.; Oleynikov, P.; Yoon, K. B. Capture of iodine and organic iodides using silica zeolites and the semiconductor behavior of iodine in a silica zeolite. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9(3), 1050-1062. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Kim, C.; Han, E.; Lee, H.; Cho, H. S.; Choi, M. Relationship between zeolite structure and capture capability for radioactive cesium and strontium. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 408, 124419. [CrossRef]

- Hijikata, T., Koyama, T.; Aikyo, Y.; Shimura, S.; Kawanishi, M. Strontium adsorption characteristics of natural Zeolites for permeable reactive barrier in Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2021, 58(10), 1079-1098. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223131.2021.1911871. [CrossRef]

- Belviso, C. Special Issue “Sustainable Remediation Processes Based on Zeolites”. Processes 2021, 9(12), 2153. [CrossRef]

- de Gennaro, B.; Aprea, P.; Liguori, B.; Galzerano, B.; Peluso, A.; Caputo, D. Zeolite-rich composite materials for environmental remediation: Arsenic removal from water. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10(19), 6938. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cao, B.; Yin, H.; Meng, L.; Jin, W.; Wang, F.; Xu, J.; Al-Tabbaa, A. Application of zeolites in permeable reactive barriers (PRBs) for in-situ groundwater remediation: A critical review. Chemosphere 2022, 308, 136290. [CrossRef]

- Eberle, S.; Börnick, H.; Stolte, S. Granular natural zeolites: Cost-effective adsorbents for the removal of ammonium from drinking water. Water 2022, 14(6), 939. [CrossRef]

- Mancinelli, M.; Arfè, A.; Martucci, A.; Pasti, L.; Chenet, T.; Sarti, E.; Vergine, G.; Belviso, C. Evaluation for the removal efficiency of VOCs and heavy metals by zeolites-based materials in the wastewater: A case study in the Tito Scalo industrial area. Processes 2020, 8(11), 1519. [CrossRef]

- Guzzinati, R.; Sarti, E.; Catani, M.; Costa, V.; Pagnoni, A.; Martucci, A.; Rodeghero, E.; Capitani, D.; Pietrantonio, M.; Cavazzini, A.; Pasti, L. Formation of Supramolecular Clusters at the Interface of Zeolite X Following the Adsorption of Rare-Earth Cations and Their Impact on the Macroscopic Properties of the Zeolite. ChemPhysChem 2018, 19(17), 2208-2217. [CrossRef]

- Mijailović, N. R.; Nedić Vasiljević, B.; Ranković, M.; Milanović, V.; Uskoković-Marković, S. Environmental and pharmacokinetic aspects of zeolite/pharmaceuticals systems. Two facets of adsorption ability. Catalysts 2022, 12(8), 837. [CrossRef]

- Martucci, A.; Pasti, L.; Marchetti, N.; Cavazzini, A.; Dondi, F.; Alberti, A. Adsorption of pharmaceuticals from aqueous solutions on synthetic zeolites. Microporous and Mesoporous Mater. 2012, 148(1), 174-183. [CrossRef]

- Pasti, L.; Sarti, E.; Cavazzini, A.; Marchetti, N.; Dondi, F.; Martucci, A. Factors affecting drug adsorption on beta zeolites. J. Sep. Sci. 2013, 36(9-10), 1604-1611. [CrossRef]

- Sarti, E.; Chenet, T.; Stevanin, C.; Costa, V.; Cavazzini, A.; Catani, M.; Martucci, A.; Precisvalle, N.; Beltrami, G.; Pasti, L. High-silica zeolites as sorbent media for adsorption and pre-concentration of pharmaceuticals in aqueous solutions. Molecules 2020, 25(15), 3331. [CrossRef]

- Braschi, I.; Blasioli, S.; Gigli, L.; Gessa, C. E.; Alberti, A., Martucci, M. Removal of sulfonamide antibiotics from water: evidence of adsorption into an organophilic zeolite Y by its structural modifications. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 178(1-3), 218-225. [CrossRef]

- Belviso, C.; Lucini, P.; Mancinelli, M.; Abdolrahimi, M.; Martucci, A.; Peddis, D.; Maraschi, F.; Cavalcante, F.; Sturini, M. Lead, zinc, nickel and chromium ions removal from polluted waters using zeolite formed from bauxite, obsidian and their combination with red mud: Behaviour and mechanisms. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 415, 137814. [CrossRef]

- Chenet, T.; Mancinelli, M.; Sarti, E.; Costa, V.; D’Anna, C.; Martucci, A.; Pasti, L. Competitive Adsorption of 4-Hydroxybenzaldehyde and Toluene onto High Silica Zeolites. Environ. Process. 2024, 11(3), 49. [CrossRef]

- Y.; Cao, B.; Yin, H.; Meng, L.; Jin, W.; Wang, F.; Xu, J.; Al-Tabbaa, A. Application of zeolites in permeable reactive barriers (PRBs) for in-situ groundwater remediation: A critical review. Chemosphere 2022, 308, 136290. [CrossRef]

- Braschi, I.; Martucci, A.; Blasioli, S.; Mzini, L. L.; Ciavatta, C.; Cossi, M. Effect of humic monomers on the adsorption of sulfamethoxazole sulfonamide antibiotic into a high silica zeolite Y: An interdisciplinary study. Chemosphere 2016, 155, 444-452. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Qian, C.; Ma, S.; Xiong, J. Sulfonamide antibiotics sorption by high silica ZSM-5: effect of pH and humic monomers (vanillin and caffeic acid). Chemosphere 2020, 248, 126061. [CrossRef]

- Chenet, T.; Sarti, E.; Costa, V.; Cavazzini, A.; Rodeghero, E.; Beltrami, G.; Felletti, S.; Pasti, L.; Martucci, A. Influence of caffeic acid on the adsorption of toluene onto an organophilic zeolite. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8(5), 104229. [CrossRef]

- Mancinelli, M.; Ardit, M.; Chenet, T.; Pasti, L.; Martucci, A. Desorption of humic monomers from Y zeolite: A high-temperature X-ray diffraction and thermogravimetric study. Microporous and Mesoporous Mater. 2024, 379, 113270,.

- Mancinelli, M.; Martucci, A.; Ahrens, L. Exploring the adsorption of short and long-chain per-and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) to different zeolites using environmental samples. Environ. Sci.: Water Res. Technol. 2023, 9(10), 2595-2604. [CrossRef]

- Ponge, C. A.; Sheehan, N. P.; Corbin, D. R.; Peltier, E.; Hutchison, J. M.; Shiflett, M. B. Zeolites for Sorption of PFAS from Water. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63(27), 12102-12112. [CrossRef]

- Mancinelli, M.; Stevanin, C.; Ardit, M.; Chenet, T.; Pasti, L.; Martucci, A. PFAS as emerging pollutants in the environment: A challenge with FAU type and silver-FAU exchanged zeolites for their removal from water. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10(4), 108026. [CrossRef]

- Ponge, C. A.; Corbin, D. R.; Sabolay, C. M.; Shiflett, M. B. Designing zeolites for the removal of aqueous PFAS: a perspective. Ind. Chem. Mater. 2024, 2(2), 270-275. [CrossRef]

- Mancinelli, M.; Martucci, A.; Salani, G. M.; Bianchini, G.; Gigli, L.; Plaisier, J. R.; Colombo, F. High-temperature behavior of Ag-exchanged Y zeolites used for PFAS sequestration from water. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25(29), 20066-20075. [CrossRef]

- Omo-Okoro, P. N.; Curtis, C. J.; Marco, A. M.; Melymuk, L.; Okonkwo, J. O. Removal of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances from aqueous media using synthesized silver nanocomposite-activated carbons. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2021, 19, 217-236. [CrossRef]

- Riley, B. J.; Chong, S.; Schmid, J.; Marcial, J.; Nienhuis; Bera, M. K.; Lee, S.; Canfield, N. L.; Kim, S.; Derewinski, M. A.; Motkuri, R.K. Role of zeolite structural properties toward iodine capture: A head-to-head evaluation of framework type and chemical composition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022, 14(16), 18439-18452. [CrossRef]

- Pham, T. C. T.; Docao, S.; Hwang, I. C.; Song, M. K.; Moon, D.; Oleynikov, P.; Yoon, K. B. Capture of iodine and organic iodides using silica zeolites and the semiconductor behavior of iodine in a silica zeolite. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9(3), 1050-1062. [CrossRef]

- Senila, M.; Cadar, O. Modification of natural zeolites and their applications for heavy metal removal from polluted environments: Challenges, recent advances, and perspectives. Heliyon 2024, 10(3), e25303. [CrossRef]

- Velarde, L.; Nabavi, M. S.; Escalera, E.; Antti, M. L.; Akhtar, F. Adsorption of heavy metals on natural zeolites: A review. Chemosphere 2023, 328, 138508. [CrossRef]

- Tufail, M. K.; Ifrahim, M.; Rashid, M.; Haq, I. U.; Asghar, R.; Uthappa, U. T., Selvaraj, M; Kurkuri, M. Chemistry of zeolites and zeolite based composite membranes as a cutting-edge candidate for removal of organic dyes & heavy metal ions: Progress and future directions. Sep. Purif. Technol., 2024, 128739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2024.128739. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zheng, F.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Huang, X.; Chen, L.; Bashir, S.; Liu, J. L. Facile preparation of zeolite-activated carbon composite from coal gangue with enhanced adsorption performance. Chem. Eng. J., 2020, 390, 124513.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2020.124513. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi, N. M.; Saffar-Dastgerdi, M. H. Clean Laccase immobilized nanobiocatalysts (graphene oxide-zeolite nanocomposites): From production to detailed biocatalytic degradation of organic pollutant. Appl. Catal. B: Environ., 2020, 268, 118443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118443. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.; Mushtaq, R.; Saghar, S.; Younas, U.; Pervaiz, M.; Muteb Aljuwayid, A.; Habila, M. A.; Sillanpaa, M. Fabrication of graphene-oxide and zeolite loaded polyvinylidene fluoride reverse osmosis membrane for saltwater remediation. Chemosphere, 2022, 307, 136012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136012. [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Xiao, H.; Azarabadi, H.; Song, J.; Wu, X.; Chen, X.; Lackner, K.S. Sorbents for the direct capture of CO2 from ambient air. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59(18), 6984-7006. [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Davis, M. E. Carbon dioxide capture with zeotype materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51(22), 9340-9370. [CrossRef]

- Confalonieri, G.; Grand, J.; Arletti, R.; Barrier, N.; Mintova, S. CO2 adsorption in nanosized RHO zeolites with different chemical compositions and crystallite sizes. Microporous and Mesoporous Mater. 2020, 306, 110394,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2020.110394. [CrossRef]

- Rahmah, W.; Kadja, G. T. M.; Mahyuddin, M. H.; Saputro, A. G.; Dipojono, H. K., Wenten, I.G. Small-pore zeolite and zeotype membranes for CO2 capture and sequestration–A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10(6), 108707. [CrossRef]

- Davarpanah, E.; Armandi, M.; Hernández, S.; Fino, D.; Arletti, R.; Bensaid, S.; Piumetti, M. CO2 capture on natural zeolite clinoptilolite: Effect of temperature and role of the adsorption sites. J. Environ. Manage. 2020, 275, 111229. [CrossRef]

- Colella, C. Natural zeolites in environmentally friendly processes and applications. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 1999, 125, 641-655. [CrossRef]

- Boronat, M.; Corma, A. Factors controlling the acidity of zeolites. Catal. Letters 2015, 145, 162-172. [CrossRef]

- Čejka, J.; Wichterlová, B. Acid-catalyzed synthesis of mono-and dialkyl benzenes over zeolites: Active sites, zeolite topology, and reaction mechanisms. Catal. Rev. 2002, 44(3), 375-421. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; bin Samsudin, I.; Jaenicke, S.; Chuah, G. K. Zeolites in catalysis: sustainable synthesis and its impact on properties and applications. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2022, 12(19), 6024-6039. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Wang, N.; Yu, J. Advances in catalytic applications of zeolite-supported metal catalysts. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33(51), 2104442. [CrossRef]

- Dusselier, M.; Van Wouwe, P.; Dewaele, A.; Jacobs, P. A.; Sels, B. F. Shape-selective zeolite catalysis for bioplastics production. Science 2015, 349(6243), 78-80. [CrossRef]

- Faisal, A.; Holmlund, M.; Ginesy, M.; Holmgren, A.; Enman, J.; Hedlund, J.; Grahn, M. Recovery of l-arginine from model solutions and fermentation broth using zeolite-Y adsorbent. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7(9), 8900-8907. [CrossRef]

- Jatoi, A. S.; Baloch, H. A.; Mazari, S. A.; Mubarak, N. M.; Sabzoi, N.; Aziz, S.; Soomro, S. A.; Abro, R.; Shah, S. F. A review of extractive fermentation via ion exchange adsorption resins opportunities, challenges, and prospects. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2021, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Feng, K.; Liu, J. Oriented fermentation of food waste towards high-value products: A review. Energies 2020, 13(21), 5638; https://doi.org/10.3390/en13215638. [CrossRef]

- Munsch, S.; Hartmann, M.; Ernst, S. Adsorption and separation of amino acids from aqueous solutions on zeolites. Chem. Comm. 2021, 19, 1978-1979. [CrossRef]

- Polisi, M.; Fabbiani, M.; Vezzalini, G.; Di Renzo, F.; Pastero, L.; Quartieri, S.; Arletti, R. Amino acid encapsulation in zeolite MOR: Effect of spatial confinement. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23(36), 20541-20552. [CrossRef]

- Beltrami, G.; Martucci, A.; Pasti, L.; Chenet, T.; Ardit, M.; Gigli, L.; Cescon, M.; Suard, E. L− Lysine Amino Acid Adsorption on Zeolite L: a Combined Synchrotron, X-Ray and Neutron Diffraction Study. Chemistry Open 2020, 9(10), 978-982. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wun, C. K. T.; Day, S. J.; Tang, C. C.; Lo, T. W. B. Enantiospecificity in achiral zeolites for asymmetric catalysis. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22(34), 18757-18764. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Huang, B.; Day, S.; Tang, C. C.; Tsang, S. C. E.; Wong, K.; Lo, T. W. B. Differential Adsorption of l-and d-Lysine on Achiral MFI Zeolites as Determined by Synchrotron X-Ray Powder Diffraction and Thermogravimetric Analysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59(3), 1093-1097. [CrossRef]

- 74. Serati-Nouri, H.; Jafari, A.; Roshangar, L.; Dadashpour, M.; Pilehvar-Soltanahmadi, Y.; Zarghami, N. Biomedical applications of zeolite-based materials: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 116, 111225. [CrossRef]

- Elsherbeni, A. I.; Youssef, I. M.; Kamal, M.; Youssef, M. A.; El-Gendi, G. M.; El-Garhi, O. H.; Alfassam, H. E.; Rudayni, H. A.; Allam, A. A.; Moustafa, M.; Alshaharni, M. O.; Al-Shehri, M.; El Kholy, M. S.; Hamouda, R.E. Impact of Adding Zeolite to broilers' Diet and Litter on Growth, Blood Parameters, Immunity, and Ammonia Emission. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103981. [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, D.; Katsoulos, P. D.; Panousis, N.; Karatzias, H. The role of natural and synthetic zeolites as feed additives on the prevention and/or the treatment of certain farm animal diseases: A review. Microporous and Mesoporous Mater. 2005, 84(1-3), 161-170. [CrossRef]

- Kucherenko, I. S.; Soldatkin, O. O.; Dzyadevych, S. V.; Soldatkin, A. P. Application of zeolites and zeolitic imidazolate frameworks in biosensor development. Biomater Adv. 2022, 143, 213180. [CrossRef]

- Bacakova, L.; Vandrovcova, M.; Kopova, I.; Jirka, I. Applications of zeolites in biotechnology and medicine – a review. Biomater. Sci. 2018, 6(5), 974-989. [CrossRef]

- Servatan, M.; Zarrintaj, P.; Mahmodi, G.; Kim, S. J.; Ganjali, M. R.; Saeb, M. R.; Mozafari, M. Zeolites in drug delivery: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. Drug Discov. Today 2020, 25(4), 642-656. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J. F. Adsorption and polymerization of amino acids on mineral surfaces: a review. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 2008, 38, 211-242. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).