1. Introduction

Heart failure (HF) remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide (1). The prevalence of HF ranges from 1% to 5%, with significantly higher rates among older adults, and is expected to rise further, driven in part by an aging population (2). However, these numbers may be underestimated, as HF is often underdiagnosed in older patients due to its overlap with geriatric syndromes such as frailty and multimorbidity (3). These factors contribute to an increase in the absolute number of HF hospitalizations, which is projected to grow by as much as 50% over the next 20 years (4), posing a substantial public health challenge.

In older patients, several aging-related factors, along with traditional risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and coronary artery disease, trigger structural and functional changes in the heart, increasing the incidence of HF(5). One frequently overlooked but crucial aspect is iron deficiency (ID), which affects up to 50% of HF patients (6). ID is closely linked to chronic low-grade inflammation, a condition commonly associated with aging (7). The concept of “inflammaging” highlights how persistent inflammatory pathways in older adults contribute to an increased cardiovascular risk. Consequently, aging, chronic inflammation, and ID collectively exacerbate HF (8).

ID has emerged has emerged as a significant factor in Heart Failure with reduced (HFrEF) or mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) , associated with worse quality of life and a higher risk of adverse events. ID treatment has been shown to improve exercise tolerance and quality of life, as well as reduce hospitalizations and mortality(4). However, further evidence is needed on managing ID, especially in patients with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and older adults (9). The divergent results from trials evaluating the role of ID in HF underscore the need for further research into the pathophysiology of HF and highlight the necessity of refining current definitions of ID in HF to improve patient outcomes (10,11).

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the main pathophysiological mechanisms driving inflammation and ID in HF, focusing on older patients. We will address the ongoing controversies, the limitations of current treatments, and gaps in our understanding while discussing the latest pharmacological advancements and pivotal studies in this evolving field to improve patient outcomes.

2. Pathophysiology of Heart Failure: role Inflammation and Iron Deficiency

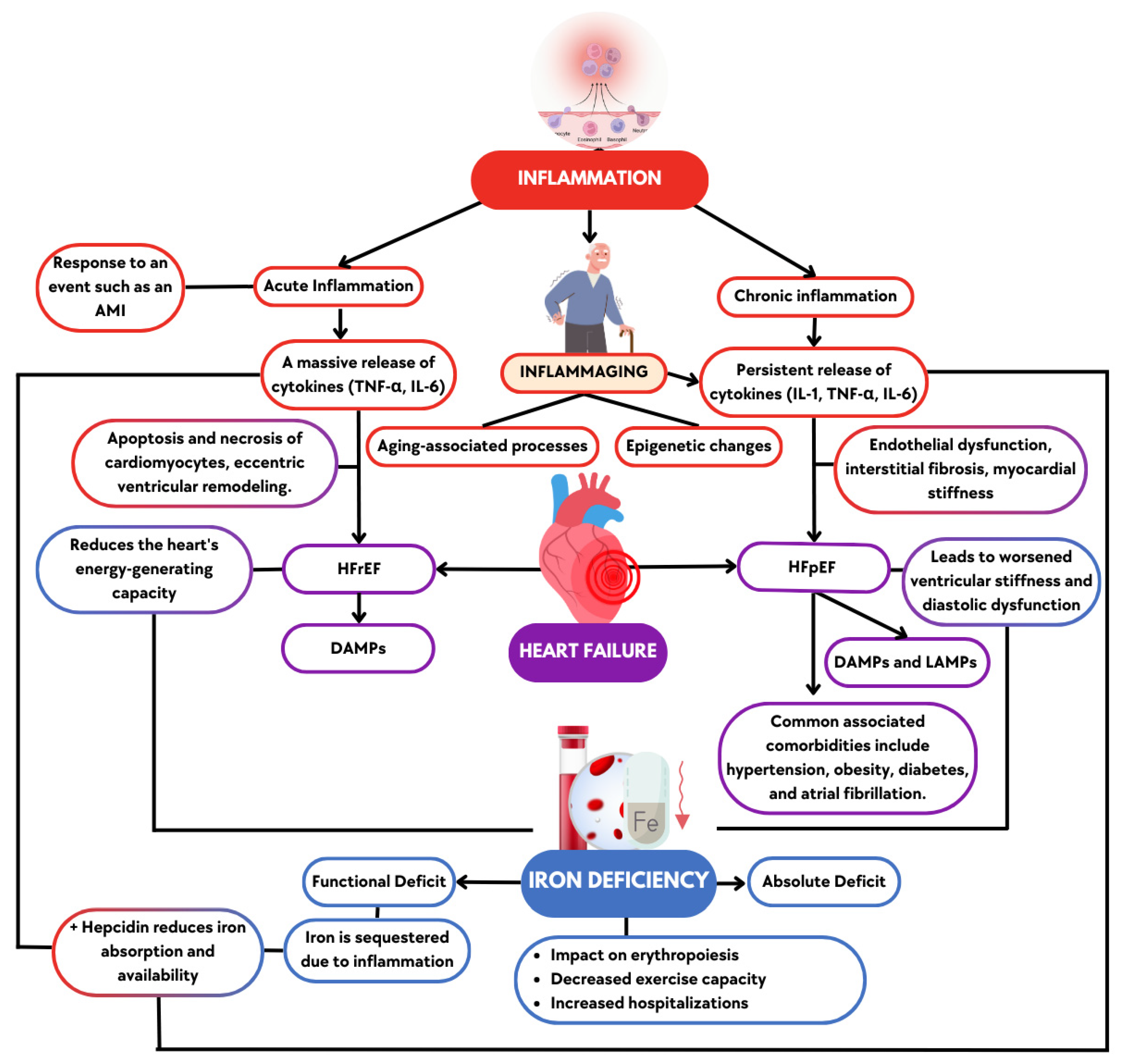

HF represents the final common pathway of numerous cardiovascular pathologies, driven by a complex interplay of hemodynamic, neurohormonal, metabolic, and inflammatory factors that contribute to its onset and progression. Inflammation plays a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of heart failure by regulating key processes, like fibrosis and ventricular remodeling.(12). In older patients, chronic low-grade inflammation and immunosenescence, combined with comorbidities, accelerate cardiac dysfunction, a progression that is particularly notable in those patients with ID (13). In this section, we discuss how inflammation is linked with HF pathophysiology, the role of “inflammaging” in older patients, and the relationship of these processes to ID in this context (

Figure 1).

2.1. Inflammation in Heart Failure

Inflammation in HF can be categorized into acute or chronic (12). Acute inflammatory episodes, such as those following an acute myocardial infarction (AMI), trigger an intense inflammatory response aimed at repairing tissue damage (14). However, when this response is prolonged, it contributes to adverse myocardial remodeling, ultimately leading to HF (15). During AMI, the massive release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) promotes the infiltration of inflammatory cells, which can lead to damage and loss of cardiomyocytes, as well as fibrosis (16).

Chronic low-grade inflammation is even more insidious, occurring in individuals with comorbidities and is closely associated with aging. These conditions create an unresolved inflammatory state , involving effectors such as proinflammatory cytokines and components of the innate and humoral immune response, which contribute to the progressive dysfunction of the left ventricle (17). Both HFrEF and HFpEF are influenced by inflammation but with distinct mechanisms and outcomes (11).

In HFrEF, the inflammatory process primarily targets cardiomyocytes, leading to their apoptosis and necrosis, which drives eccentric remodeling of the left ventricle, resulting in ventricular dilation and decreased contractile function (18). In contrast, HFpEF involves endothelial dysfunction, increasing myocardial stiffness through interstitial fibrosis and impairing diastolic function (18). HFpEF is now recognized as a systemic syndrome, where inflammation, aging, lifestyle factors, genetic predisposition, and comorbidities such as age, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and atrial fibrillation play a significant role (19). All these factors lead to fibrosis, nitric oxide signaling deficits, and mitochondrial dysfunction, contributing to the structural and functional changes in the heart (20). Finally, all these inflammatory processes, affecting cardiomyocytes in HFrEF or endothelial function in HFpEF, are associated with molecular patterns that drive immune responses and contribute to disease progression (21).

The interaction between pathogens, tissue damage, and immune responses in HF can be understood through the concepts of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), and Lifestyle-associated molecular patterns (LAMPs) (22). PAMPs originate from pathogens, DAMPs from damaged tissues like after a myocardial infarction, while LAMPs are influenced by lifestyle factors like poor diet or inactivity. All these patterns can dysregulate the immune system, leading to unresolved inflammation, chronic damage, and worsening HF (22).

Table 1 summarizes the main aspects that differentiate inflammation in HF.

2.2. Inflammation in the Older Patient

In older patients, the phenomenon of inflammaging—a chronic, low-grade inflammation that accompanies aging—plays a central role in the progression of HF and the development of ID (23).

Inflammaging involves chronic innate immune activation, leading to the release of inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, TNF-α, IL-6) that exacerbate HF and systemic organ damage. Mechanisms like NF-κB activation and NLRP3 inflammasome formation drive systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, arterial stiffness, and endothelial dysfunction, increasing cardiovascular risk (24). This creates a cycle of inflammation that accelerates HF progression and adverse outcomes (25). The upregulation of pro-inflammatory mediators like IL-1β and Interleukin-18 (IL-18) further exacerbates this, as both are implicated in cardiac fibrosis, hypertrophy, and diastolic dysfunction (26).

Moreover, in patients with HF, elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) damage cardiomyocytes, while chronic inflammation impairs iron regulation, worsening ID and its impact on HF (27). In addition, infiltration of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages into the myocardium was observed more prominently in aging women, reduced the presence of anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, and contributed to cardiac dysfunction. In contrast, male patients with end-stage cardiomyopathy display a higher presence of CD68-positive macrophages, highlighting sex differences in immune responses associated with inflammaging and HF progression (24).

2.3. The Role of Inflammation in Iron Deficiency

The link between inflammation and ID in HF is well-established and especially relevant in older patients (28). Under conditions of chronic inflammation, as seen in HF and inflammaging, levels of IL-6 increase, which triggers the production of hepcidin (29). Hepcidin reduces iron absorption in the intestines and sequesters iron in macrophages and hepatocytes. This primarily leads to functional ID, where iron stores are adequate but it is not available for essential processes such as hemoglobin synthesis and ATP production in mitochondria (30). Several studies have demonstrated the relationship between inflammation and ID (31–33). Specifically, an international registry including 2,329 HF patients found that increased plasma IL-6 concentrations were associated with lower iron and higher hepcidin levels, highlighting IL-6’s role in the dysregulation of iron metabolism (29). Inflammatory cytokines also inhibit erythropoiesis by impairing the bone marrow’s response to erythropoietin, contributing to anemia (34). In patients with HF, exacerbated inflammation promotes this state of functional ID. This interaction between inflammation, ID, and anemia increase stress on the heart and exacerbates HF symptoms, including fatigue and exercise intolerance (35).

2.4. Iron Deficiency in Heart Failure

ID is common in patients with HF, affecting up to 50% of them, regardless of the presence of anemia (36). According to heart failure practice guidelines, ID in HF is classified into two main forms: absolute and functional. Absolute ID occurs when total body iron stores are depleted, while functional ID occurs when iron is sequestered in the body despite adequate stores, usually due to inflammation (27). Both forms of ID are associated with poorer outcomes in HF patients, including reduced exercise tolerance, higher hospitalization rates, and increased mortality (37).

As previously explained, ID impacts hematopoietic function and directly affects cellular function due to its role in mitochondrial respiration and energy production (27). In HF patients, ID is associated with reduced functional capacity, decreased quality of life, and increased hospitalizations and mortality (38). In HFrEF, ID directly contributes to myocardial dysfunction by reducing the heart’s ability to generate energy. But ID not only impacts in HfrEF, it is also prevalent in HFpEF, though the mechanisms by which it impacts cardiac and muscular performance may differ slightly from those observed in HfrEF (39). Rather than contractility failure, HFpEF patients experience ventricular stiffness and diastolic dysfunction exacerbated by inflammation and ID (40).

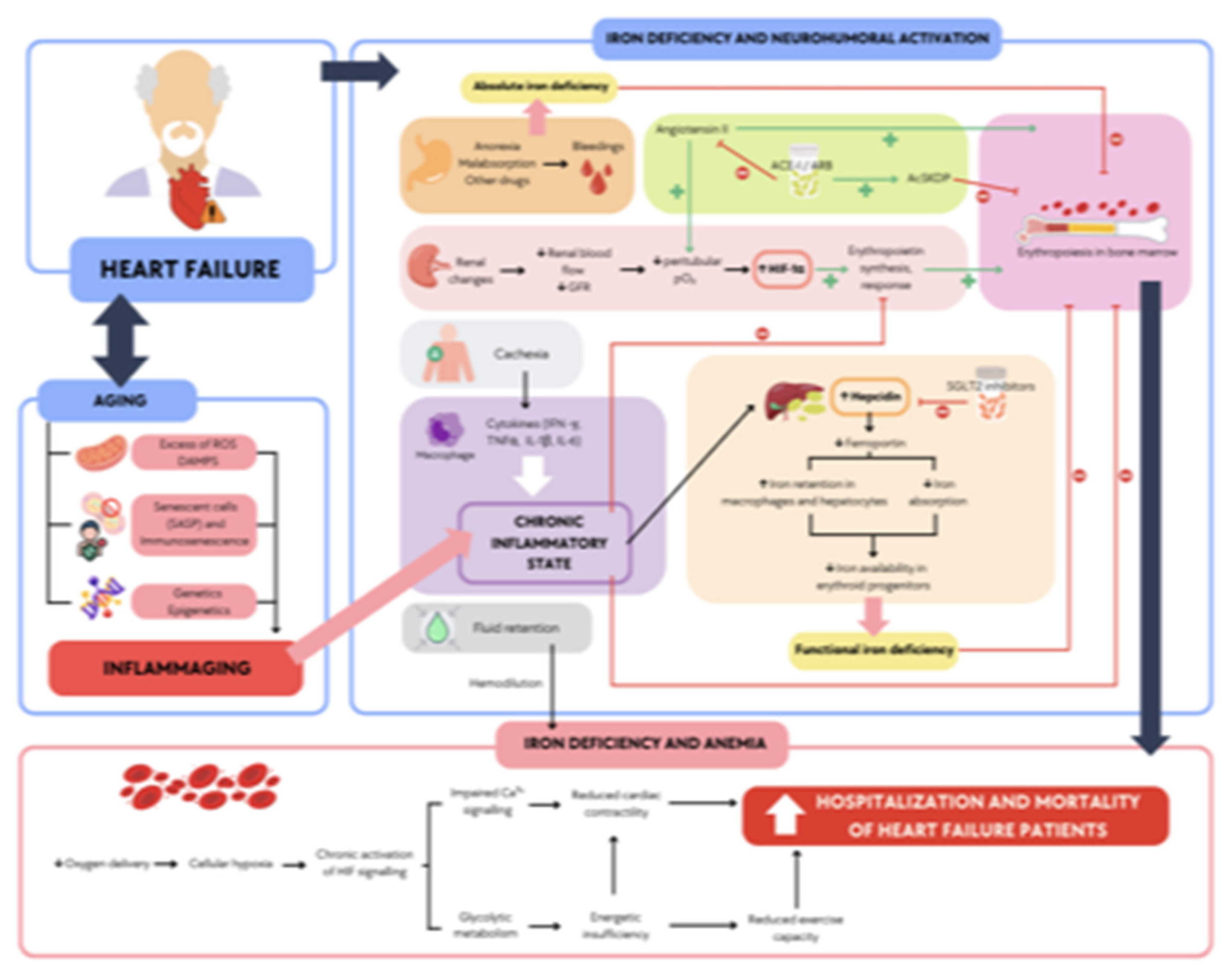

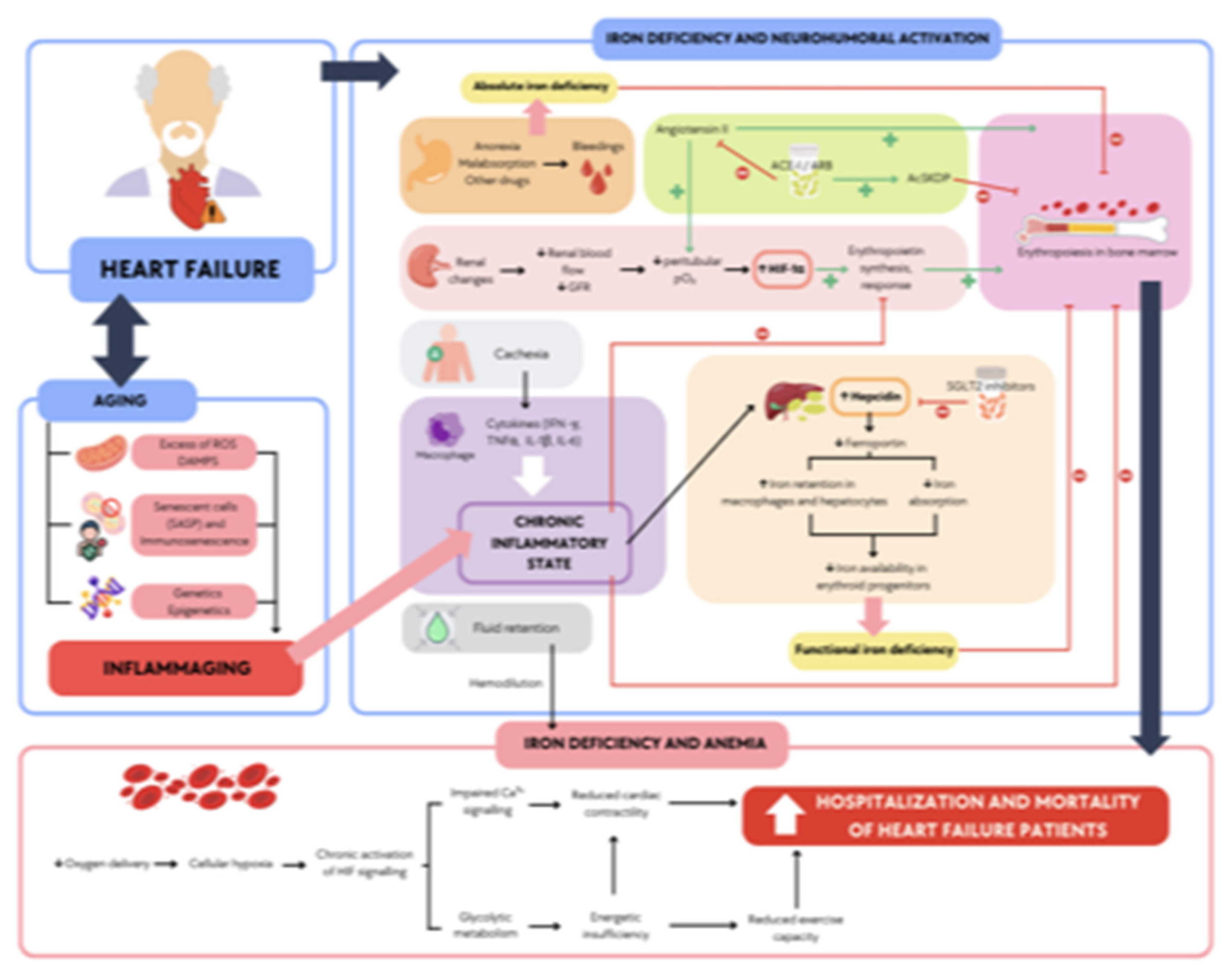

3. Impact of Iron Deficiency on Heart Failure in Older Patients

In older patients with HF, a vicious cycle emerges from the interplay of multimorbidity, inflammaging, and inflammatory mediators such as IL-6, worsening anemia, and frailty (41). Chronic inflammation, often driven by comorbidities, elevates hepcidin levels, leading to functional ID. This inflammatory state not only impairs iron metabolism but also exacerbates HF symptoms, promoting cardiac dysfunction and fatigue. This interaction significantly worsens prognosis, increasing hospitalizations and mortality (4). The intricate relationship between aging, inflammation, and ID in HF highlights the need for a deeper understanding of these mechanisms to improve patient outcomes.

3.1. The Role of Aging and Inflammation in Iron Deficiency

Aging-related changes in immune function, termed immunosenescence and inflammaging, synergistically worsen iron dysregulation in older HF patients (23). In this population, the inflammatory state becomes even more pronounced, as HF is associated with elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

In this context, hepcidin, a central iron homeostasis regulator, leads to functional iron deficiency (42). As a result, HF patients with ID experience disrupted mitochondrial function, impairing the electron transport chain and reducing oxidative phosphorylation, forcing the heart to rely on glycolysis for energy production (27). This shift is partly driven by the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway, as ID stabilizes HIF by inhibiting prolyl hydroxylases, even in normoxic conditions. The activation of HIF target genes mimics a hypoxic response, further promoting glycolysis over oxidative metabolism. While glycolysis generates energy faster, it is less efficient, leading to diminished ATP production and compromised cardiac contractility, worsening HF outcomes (35).

Futhermore, the combined effects of aging, inflammation, and iron deficiency severely impair cardiac function and elevate the risk of hospitalizations in older HF patients (38).

Figure 2 summarizes how the combined impact of inflammation from HF and aging exacerbates ID, leading to increased hospitalizations and a worse overall prognosis.

A systematic review and meta-analysis examined the relationship between anemia and frailty in older adults (43). The study found that frail individuals are more than twice as likely to present anemia with their non-frail counterparts, underscoring the close association between these two conditions. The pooled prevalence of frailty among individuals with anemia was 24%, further highlighting the need to consider frailty when assessing older adults with anemia (43).

On the other hand, a study involving 208 older hospitalized patients categorized by frailty revealed that inflammation significantly increased the prevalence of anemia, particularly in frail patients (44).

The diagnosis of ID in older patients is essential for improving outcomes. In older adults with multimorbidity, factors like frailty, malnutrition, and chronic diseases often contribute to anemia, making it difficult to distinguish ID for HF from other causes of anemia. This challenge is especially relevant in frail patients, who are more likely to have elevated markers of inflammation that can obscure ID (45).

4. Diagnosis, Treatment, and Therapeutic Challenges

Early diagnosis is critical because treating ID has been shown to improve clinical outcomes, reduce hospitalizations, and enhance quality of life (4). A retrospective study of older patients with HF showed that addressing ID early, particularly with IV iron, reduced the incidence of infections and improved functional capacity (46). Therefore, screening for ID in older patients with HF should be a routine part of clinical care, as these patients are at higher risk of complications from untreated ID.

The diagnosis of ID in HF patients relies on serum ferritin and transferrin saturation (TSAT) as primary biomarkers. Current guidelines define ID as a ferritin level <100 ng/mL or 100-299 ng/mL with TSAT <20% (4). However, this definition has sparked significant controversy due to the distortion of ferritin levels by systemic inflammatory states, commonly seen in older adults and patients with chronic conditions like inflammatory bowel disease or chronic kidney disease (CKD) (31). Additionally, as ferritin is an acute-phase reactant, its levels are often elevated in response to inflammation, potentially masking actual ID (47).

Packer et al. highlighted that nearly 25 years ago, the diagnostic threshold for ferritin in patients with HF was significantly increased—by 5- to 20-fold—to promote the use of iron supplements and improve the effectiveness of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in treating renal anemia (10). However, this change was driven by clinical necessity rather than studies on total body iron depletion. As a result, this threshold is not a reliable ID indicator in HF patients. He proposes that, in the context of HF, a transferrin saturation (TSAT) threshold of less than 20% should be prioritized over ferritin levels to diagnose iron deficiency (10). This approach emphasizes the need for a more precise ID marker, which helps identify patients who would most benefit from intravenous iron therapy (10).

Shifting the focus from ferritin to TSAT <20% could lead to earlier interventions and better outcomes for HF patients, particularly older adults prone to both inflammation and ID (10,28). This change in diagnostic criteria is particularly relevant in light of the evidence that patients with functional ID (low TSAT but normal ferritin) respond well to IV iron supplementation (10).

4.1. Clinical Trials Supporting Intravenous Iron Therapy

Current guidelines recommend IV iron therapy for patients with HF and <50% left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and ID, supported by evidence from clinical trials outlined in

Table 2 (4). These studies consistently show that IV iron alleviates symptoms, enhances functional capacity, and reduces hospitalizations in this population. However, despite the prevalence of ID and associated symptoms, similar recommendations do not extend to patients with HFpEF, where the evidence is less (40).

4.2. Response in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction

While ID is common in HFpEF patients, the current guidelines do not advocate for routine iron supplementation (4). This discrepancy is primarily due to the limited evidence regarding the efficacy of iron treatment in this population. For example, the Ferric carboxymaltose and exercise capacity in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and iron deficiency: the FAIR-HFpEF trial (FAIR-HFpEF trial) investigated the impact of IV iron on exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with HFpEF and serum ferritin < 100 ng/mL or ferritin 100-299 ng/mL with TSAT < 20%. Although some patients experienced improvements, the overall results did not justify a broad recommendation of iron therapy in this group because the trial lacked sufficient power to identify or refute effects on symptoms or quality of life. Consequently, many patients with HFpEF continue to suffer debilitating symptoms, yet there is insufficient evidence to support routine iron supplementation (53).

The Trial of Exercise Training in Patients with Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction (TRAINING-HF) was a landmark study designed to evaluate the efficacy of structured exercise training in improving functional capacity and quality of life in patients with HFpEF. The trial demonstrated that tailored exercise programs significantly enhance peak oxygen consumption (peak VO2), functional status, and symptoms in HFpEF patients, providing robust evidence for the role of physical training in this population. Moreover, the findings highlighted the influence of patient-specific factors, such as ID, on the overall response to therapy (54).

Building on these findings, a substudy of TRAINING-HF by Palau et al. provides additional insights into the specific role of ID in modulating exercise response in HFpEF. This substudy revealed that patients with ID, defined as ferritin levels <100 ng/mL or TSAT <20%, exhibited a markedly poorer response to exercise interventions compared to non-ID patients (P for interaction <0.001). Specifically, individuals with lower baseline ferritin or TSAT showed less improvement in peak VO2, a key marker of aerobic capacity and functional status (55). These findings underscore the importance of evaluating and addressing iron status as part of the pre-exercise assessment in HFpEF patients to optimize therapeutic outcomes.

4.3. Impact of Pharmacologic Treatments on Iron Metabolism

Pharmacologic treatments for HF, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), may influence iron metabolism. ACEi and ARBs may affect iron metabolism by suppressing erythropoietin production (56). This medication could exacerbate anemia and worsen ID in some patients (57). Although these drugs improve cardiovascular outcomes by modulating the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), their impact on iron regulation needs further exploration.

Conversely, sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitors (SGLT2i) have shown promise in improving iron homeostasis by reducing hepcidin levels. By lowering hepcidin, SGLT2i may enhance iron mobilization, improving ID and HF outcomes in patients across the ejection fraction spectrum (58).

Finally, neprilysin inhibitors such as sacubitril/valsartan may also influence iron metabolism. By reducing inflammation, these drugs lower hepcidin and ferritin levels, improving iron availability and promoting erythropoiesis (59). However, they may also distort the interpretation of iron biomarkers, complicating the diagnosis and management of ID in HF (10). Similarly, vericiguat has been associated with an increased incidence of anemia, as observed in the VICTORIA trial (60). However, the underlying pathophysiological mechanism remains unclear due to the lack of ferric metabolism biomarkers collected during the study.

4.4. Clinical Implications and Management

Despite compelling evidence that TSAT <20% is a more reliable marker of ID than ferritin, current clinical guidelines have not yet fully adopted this approach (4). It is argued that reliance on ferritin thresholds is outdated and propose prioritizing TSAT to identify better patients who would benefit from IV iron therapy. This shift would align with the growing evidence showing that patients with hypoferremia (TSAT <20%) respond best to iron supplementation (10). The role of pharmacologic treatments in managing iron deficiency also requires careful consideration. As noted, ACEi, ARBs, neprilysin inhibitors, and SGLT2i influence iron metabolism differently. Clinicians should consider these effects when interpreting iron biomarkers and making treatment decisions. For instance, SGLT2 inhibitors may reduce hepcidin and improve iron availability, while ACE inhibitors and ARBs may exacerbate anemia by suppressing erythropoiesis.

Managing ID in HF, particularly in older adults, is essential for improving clinical outcomes. Recent guidelines emphasize the importance of regularly assessing iron status—measuring ferritin and TSAT levels—to identify and treat ID early (4). While IV iron therapy has emerged as a valuable treatment for patients with symptomatic ID with HF and <50% LVEF, the situation remains unclear for those with HFpEF (53). Additionally, addressing ID could enhance the effectiveness of exercise-based rehabilitation programs in HFpEF patients (55). Managing ID may improve exercise tolerance and quality of life, but further research is needed to confirm these benefits (53,55).

The inflammatory burden, combined with ID, complicates the management of HF patients, particularly in older adults who often face concurrent conditions. This complex interplay between immunosenescence and HF-induced inflammation creates a cycle that accelerates disease progression and limits the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions, including physical rehabilitation (61). To achieve better outcomes, clinicians should consider the impact of pharmacologic treatments on iron metabolism and tailor their management strategies accordingly.

5. Future Directions: Emerging Research and Therapeutic Approaches

Diagnostic criteria for ID in chronic heart failure (CHF) patients may be inadequate and potentially misleading, as they rely too heavily on serum ferritin and TSAT thresholds. Ferritin alone may not accurately reflect functional ID, as it can be influenced by inflammation and other non-iron-related factors common in HF. This imprecision may result in the inclusion of patients who are unlikely to benefit from iron supplementation, while excluding those who could experience significant clinical improvements. A revaluation of these biomarkers is needed to better identify ID that is clinically relevant to HF. A refined definition could enable more targeted and effective therapeutic interventions in this population (10).

ID and inflammation play a key role in chronic HF, with distinct inflammatory pathways potentially requiring tailored therapeutic approaches. HFrEF and HFpEF may exhibit different inflammatory profiles, suggesting that a standardized approach to iron supplementation may not be optimal for all patients. This variation underscores the need for targeted research, especially in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, who are often underrepresented in clinical trials despite constituting a significant portion of the CHF population (62). Ongoing studies aim to address specific mechanisms of ID across different HF phenotypes by examining the role of inflammation and its impact on iron metabolism. The ongoing IRON-PATH II (NCT05000853) seeks to elucidate the specific mechanisms of iron deficiency across different heart failure phenotypes by examining the role of inflammation and its impact on iron metabolism. By clarifying these mechanisms, this study hopes to pave the way for more individualized and effective iron repletion strategies that consider the unique inflammatory and iron-handling characteristics of each HF subtype (63).

A better understanding of iron homeostasis has provided a deeper understanding of iron biomarkers interrelation, presenting new and untapped opportunities to improve the management of ID in HF patients. Hepcidin is one of the key players involved in iron homeostasis, but the focus has not been set on it. Its principal function consists on reducing iron cell uptake by inhibiting ferroportin, the main cell iron exporter, and its levels are influenced by iron levels and inflammation (64). In this regard, clinical trials are testing agonists and blockers for therapeutic use, mostly being tested in hematological diseases by the moment (65). In the field of HF, treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors has shown biomarkers changes consistent with improved iron utilization by increasing serum transferrin receptor and reduced ferritin, TSAT and hepcidin. The reduction in plasma hepcidin is consistent with an improved capacity for iron absorption and increased mobilization of iron from sequestered stores (66). In this regard, in post hoc analysis of the IRONMAN trial revealed a trend to a greater increase in hemoglobin with ferric derisomaltose in iron-deficient patients taking an SGLT2 inhibitor at baseline, as compared with those not taking one (66).

Additionally, findings from the Randomized Trial of Empagliflozin in Nondiabetic Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction (EMPA-TROPISM trial) suggest that empagliflozin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, reversed cardiac remodeling and increased physical capacity in stable non-diabetic patients HFrEF (67). A post hoc study explores whether treatment effects in this cohort, comprising patients who had a high prevalence of ID, were related to iron metabolism. The analysis indicated that empagliflozin might positively influence iron metabolism in HF patients by reducing inflammation, influencing hepcidin levels and iron homeostasis (67). These results align with the observed hepcidin-lowering effects of SGLT2 inhibitors, supporting their potential to improve iron mobilization and utilization in iron-deficient HF patients by enhancing the release of iron from storage sites and facilitating its availability for erythropoiesis (67).

The hepcidin modulation capability by dapagliflozin, a SGLT2 inhibitor, is under investigation in ADIDAS trial (NCT04707261), a study conducted on a large cohort of anemic HF patients (68). Further studies are needed to elucidate whether iSGLT2 can contribute to restoring iron balance and could be positioned as a potentially beneficial drug and another tool for the treatment of ID (68).

Exacerbated inflammation contributes to functional ID by increasing hepcidin levels, which in turn restricts iron availability and exacerbates anemia (31). Addressing inflammation with anti-inflammatory therapies, therefore, could be a crucial strategy in improving iron homeostasis in this scenario. Recently, the COLICA trial demonstrated a significant reduction in inflammation markers in acute HF patients treated with colchicine (69). However, despite these changes in biomarkers, the study did not observe major improvements in hard clinical endpoints, such as mortality or hospital readmission rates. These findings suggest that while colchicine effectively reduces inflammation, its broader clinical impact in HF remains uncertain. There is a potential value of further investigation in anti-inflammatory therapies specifically designed to address the unique inflammatory mechanisms at play in HF with ID. By refining our understanding of inflammation’s role in iron metabolism across different HF phenotypes, including HFrEF and HFpEF as well as acute versus chronic presentations, we may be able to develop more targeted anti-inflammatory strategies that enhance both iron mobilization and patient outcomes (70).

Emerging therapies such as Roxadustat, a prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor (PHI), represent a promising future direction for addressing anemia and iron metabolism disorders in HF. Roxadustat has shown the ability to reduce hepcidin levels and enhance iron absorption, effectively improving iron availability. While its current focus lies in nephrology, its application in HF populations could open new avenues for managing anemia and functional ID, especially in patients with concurrent chronic kidney disease. Future trials in HF patients will be essential to evaluate its efficacy and safety within this context (70,71).

Future directions should focus on developing specific recommendations for iron therapy in HFpEF, as there is currently a lack of evidence-based studies supporting its use in this population, despite the high prevalence of ID (9). While IV iron therapy is well-supported for patients with HFrEF, the clinical complexity of HFpEF patients, most frequently presented in elderly people who often present with additional comorbidities and distinct inflammatory profiles, warrants further investigation. Ongoing and future clinical trials addressing the unique characteristics of HFpEF and its interaction with ID will be crucial to determine whether iron supplementation could provide meaningful clinical benefits and to establish more effective, tailored treatment strategies for this population (40,53).

6. Conclusions

ID and chronic inflammation are critical factors exacerbating the burden of HF, especialy in older adults. The interplay between inflammaging, multimorbidity, and functional ID significantly worsens HF outcomes, leading to higher rates of hospitalizations and mortality. While IV iron therapy has demonstrated benefits in improving symptoms, quality of life, and reducing hospitalizations in patients with HFrEF, its role in HFpEF remains uncertain due to limited evidence.

Current diagnostic criteria for ID in HF, primarily based on serum ferritin and TSAT, may not adequately reflect iron status in the context of chronic inflammation. Emerging data suggest prioritizing TSAT thresholds over ferritin to more accurately identify patients who could benefit from iron supplementation. Additionally, novel therapies targeting inflammation and iron homeostasis, such as SGLT2 inhibitors, show promise in improving iron mobilization and HF outcomes.

Future research should focus on refining diagnostic biomarkers for ID, exploring anti-inflammatory strategies, and conducting robust clinical trials to establish evidence-based recommendations for iron therapy in HFpEF and older adults with HF. Personalized treatment approaches addressing the unique inflammatory and iron-handling profiles of HF subtypes and patient populations are essential to optimize clinical outcomes.

Author Contributions

Daniela Maidana conceived and designed the review. The manuscript was drafted by Daniela Maidana, Andrea Arenas-Loriente, Pedro Cepas-Guillen, and Raphaela Tereza Brigolin Garofo, with contributions to the figures by Andrea Arroyo-Álvarez and Guillermo Barreres-Martín. Pedro Caravaca-Pérez, Pedro Cepas-Guillen and Clara Bonanad reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article as it is a review of existing literature.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the JR team at the Hospital Clínico de Valencia, including administrative staff and nurses, for their invaluable support throughout this project. Their dedication and assistance have been essential to the completion of this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shahim B, Kapelios CJ, Savarese G, Lund LH. Global Public Health Burden of Heart Failure: An Updated Review. Cardiac Failure Review [Internet]. 2023 Jul 27 [cited 2024 Nov 17];9:e11. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10398425/. [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt B, Ahmad T, Alexander K, Baker WL, Bosak K, Breathett K, et al. HF STATS 2024: Heart Failure Epidemiology and Outcomes Statistics An Updated 2024 Report from the Heart Failure Society of America. Journal of Cardiac Failure [Internet]. 2024 Sep 24 [cited 2024 Nov 17];0(0). Available from: https://onlinejcf.com/article/S1071-9164%2824%2900232-X/fulltext. [CrossRef]

- Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Anderson CAM, Arora P, Avery CL, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2023 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023 Feb 21;147(8):e93–621. [CrossRef]

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2023 Oct 1;44(37):3627–39.

- Coats AJS. Ageing, demographics, and heart failure. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2019 Dec;21(Suppl L):L4–7.

- Palleschi L, Nunziata E. Iron deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia in elderly patients with chronic heart failure. Geriatric Care [Internet]. 2017 Dec 20 [cited 2024 Sep 11];3(4). Available from: https://www.pagepressjournals.org/gc/article/view/7163. [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek M, Schwarz F, Sadlon A, Abderhalden LA, de Godoi Rezende Costa Molino C, Spahn DR, et al. Iron deficiency and biomarkers of inflammation: a 3-year prospective analysis of the DO-HEALTH trial. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022 Mar;34(3):515–25. [CrossRef]

- Franceschi C, Garagnani P, Vitale G, Capri M, Salvioli S. Inflammaging and “Garb-aging.” Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2017 Mar;28(3):199–212. [CrossRef]

- Beale AL, Warren JL, Roberts N, Meyer P, Townsend NP, Kaye D. Iron deficiency in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart [Internet]. 2019 Apr 3 [cited 2024 Oct 14];6(1):e001012. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6519409/.

- Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, Cleland JGF, Kalra PR, Mentz RJ, et al. Redefining Iron Deficiency in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure. Circulation [Internet]. 2024 Jul 9 [cited 2024 Aug 29];150(2):151–61. [CrossRef]

- Paulus WJ, Tschöpe C. A Novel Paradigm for Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: Comorbidities Drive Myocardial Dysfunction and Remodeling Through Coronary Microvascular Endothelial Inflammation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology [Internet]. 2013 Jul 23 [cited 2024 Oct 13];62(4):263–71. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109713018901.

- Boulet J, Sridhar VS, Bouabdallaoui N, Tardif JC, White M. Inflammation in heart failure: pathophysiology and therapeutic strategies. Inflamm Res. 2024 May;73(5):709–23. [CrossRef]

- Graham FJ, Friday JM, Pellicori P, Greenlaw N, Cleland JG. Assessment of haemoglobin and serum markers of iron deficiency in people with cardiovascular disease. Heart. 2023 Aug 11;109(17):1294–301. [CrossRef]

- Matter MA, Paneni F, Libby P, Frantz S, Stähli BE, Templin C, et al. Inflammation in acute myocardial infarction: the good, the bad and the ugly. European Heart Journal [Internet]. 2024 Jan 7 [cited 2024 Aug 29];45(2):89–103. [CrossRef]

- Prabhu SD, Frangogiannis NG. The Biological Basis for Cardiac Repair After Myocardial Infarction: From Inflammation to Fibrosis. Circ Res. 2016 Jun 24;119(1):91–112.

- Zhang H, Dhalla NS. The Role of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in the Pathogenesis of Cardiovascular Disease. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. 2024 Jan 16 [cited 2024 Oct 13];25(2):1082. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10817020/. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Zhao H, Wang J. Metabolism and Chronic Inflammation: The Links Between Chronic Heart Failure and Comorbidities. Front Cardiovasc Med [Internet]. 2021 May 5 [cited 2024 Oct 13];8:650278. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8131678/. [CrossRef]

- Simmonds SJ, Cuijpers I, Heymans S, Jones EAV. Cellular and Molecular Differences between HFpEF and HFrEF: A Step Ahead in an Improved Pathological Understanding. Cells [Internet]. 2020 Jan [cited 2024 Nov 17];9(1):242. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4409/9/1/242. [CrossRef]

- Campbell P, Rutten FH, Lee MM, Hawkins NM, Petrie MC. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: everything the clinician needs to know. Lancet. 2024 Mar 16;403(10431):1083–92. [CrossRef]

- Hamo CE, DeJong C, Hartshorne-Evans N, Lund LH, Shah SJ, Solomon S, et al. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024 Aug 14;10(1):55.

- Mann DL. THE EMERGING ROLE OF INNATE IMMUNITY IN THE HEART AND VASCULAR SYSTEM: FOR WHOM THE CELL TOLLS. Circulation research [Internet]. 2011 Apr 29 [cited 2024 Nov 17];108(9):1133. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3084988/.

- Halade GV, Lee DH. Inflammation and resolution signaling in cardiac repair and heart failure. EBioMedicine. 2022 May;79:103992. [CrossRef]

- Franceschi C, Garagnani P, Parini P, Giuliani C, Santoro A. Inflammaging: a new immune-metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018 Oct;14(10):576–90. [CrossRef]

- Barcena ML, Aslam M, Pozdniakova S, Norman K, Ladilov Y. Cardiovascular Inflammaging: Mechanisms and Translational Aspects. Cells [Internet]. 2022 Mar 16 [cited 2024 Oct 13];11(6):1010. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8946971/. [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci L, Fabbri E. Inflammageing: chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018 Sep;15(9):505–22. [CrossRef]

- Vlachakis PK, Theofilis P, Kachrimanidis I, Giannakopoulos K, Drakopoulou M, Apostolos A, et al. The Role of Inflammasomes in Heart Failure. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. 2024 May 14 [cited 2024 Oct 13];25(10):5372. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC11121241/.

- Alnuwaysir RIS, Hoes MF, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Meer P, Grote Beverborg N. Iron Deficiency in Heart Failure: Mechanisms and Pathophysiology. J Clin Med. 2021 Dec 27;11(1):125. [CrossRef]

- Graham FJ, Guha K, Cleland JG, Kalra PR. Treating iron deficiency in patients with heart failure: what, why, when, how, where and who. Heart. 2024 Aug 23;heartjnl-2022-322030.

- Markousis-Mavrogenis G, Tromp J, Ouwerkerk W, Devalaraja M, Anker SD, Cleland JG, et al. The clinical significance of interleukin-6 in heart failure: results from the BIOSTAT-CHF study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019 Aug;21(8):965–73. [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci L, Semba RD, Guralnik JM, Ershler WB, Bandinelli S, Patel KV, et al. Proinflammatory state, hepcidin, and anemia in older persons. Blood [Internet]. 2010 May 6 [cited 2024 Oct 14];115(18):3810–6. [CrossRef]

- Marques O, Weiss G, Muckenthaler MU. The role of iron in chronic inflammatory diseases: from mechanisms to treatment options in anemia of inflammation. Blood [Internet]. 2022 Nov 10 [cited 2024 Oct 23];140(19):2011–23. [CrossRef]

- Weiss G, Ganz T, Goodnough LT. Anemia of inflammation. Blood [Internet]. 2019 Jan 3 [cited 2024 Nov 17];133(1):40–50. [CrossRef]

- Malesza IJ, Bartkowiak-Wieczorek J, Winkler-Galicki J, Nowicka A, Dzięciołowska D, Błaszczyk M, et al. The Dark Side of Iron: The Relationship between Iron, Inflammation and Gut Microbiota in Selected Diseases Associated with Iron Deficiency Anaemia—A Narrative Review. Nutrients [Internet]. 2022 Jan [cited 2024 Nov 17];14(17):3478. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/14/17/3478.

- Ferrell PB, Koury MJ. Approach to the Diagnosis and Management of the Anemia of Chronic Inflammation. The Hematologist [Internet]. 2013 Mar 1 [cited 2024 Nov 17];10(2). [CrossRef]

- Lakhal-Littleton S, Cleland JGF. Iron deficiency and supplementation in heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2024 Jul;21(7):463–86. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo C, Carbonara R, Ruggieri R, Passantino A, Scrutinio D. Iron Deficiency: A New Target for Patients With Heart Failure. Front Cardiovasc Med [Internet]. 2021 Aug 10 [cited 2024 Oct 14];8:709872. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8383833/. [CrossRef]

- Kocyigit D, Gürses KM. Iron deficiency and its treatment in heart failure: indications and effect on prognosis [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www.escardio.org/Journals/E-Journal-of-Cardiology-Practice/Volume-14/Iron-deficiency-and-its-treatment-in-heart-failure-indications-and-effect-on-prognosis.

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. Guía ESC 2021 sobre el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la insuficiencia cardiaca aguda y crónica. Rev Esp Cardiol [Internet]. 2022 Jun 1 [cited 2023 Nov 29];75(6):523.e1-523.e114. Available from: http://www.revespcardiol.org/es-guia-esc-2021-sobre-el-articulo-S0300893221005236.

- Sato R, Koziolek MJ, von Haehling S. Translating evidence into practice: Managing electrolyte imbalances and iron deficiency in heart failure. European Journal of Internal Medicine [Internet]. 2024 Nov 9 [cited 2024 Nov 17];0(0). Available from: https://www.ejinme.com/article/S0953-6205%2824%2900444-8/fulltext. [CrossRef]

- Mollace A, Macrì R, Mollace R, Tavernese A, Gliozzi M, Musolino V, et al. Effect of Ferric Carboxymaltose Supplementation in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Role of Attenuated Oxidative Stress and Improved Endothelial Function. Nutrients. 2022 Nov 28;14(23):5057. [CrossRef]

- Maidana D, Bonanad C, Ortiz-Cortés C, Arroyo-Álvarez A, Barreres-Martín G, Muñoz-Alfonso C, et al. Sex-Related Differences in Heart Failure Diagnosis. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2023 Jun 13. [CrossRef]

- Nemeth E, Ganz T. Hepcidin and Iron in Health and Disease. Annual Review of Medicine [Internet]. 2023 Jan 27 [cited 2024 Oct 17];74(Volume 74, 2023):261–77. Available from: https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-med-043021-032816. [CrossRef]

- Palmer K, Vetrano DL, Marengoni A, Tummolo AM, Villani ER, Acampora N, et al. The Relationship between Anaemia and Frailty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22(8):965–74. [CrossRef]

- Herpich C, Göger L, Faust L, Kalymon M, Ott C, Walter S, et al. Disentangling Anemia in Frailty: Exploring the role of Inflammation. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2024 Oct 3;glae243. [CrossRef]

- Burton JK, Yates LC, Whyte L, Fitzsimons E, Stott DJ. New horizons in iron deficiency anaemia in older adults. Age and Ageing [Internet]. 2020 May 1 [cited 2024 Oct 23];49(3):309–18. [CrossRef]

- Lanz P, Wieczorek M, Sadlon A, de Godoi Rezende Costa Molino C, Abderhalden LA, Schaer DJ, et al. Iron Deficiency and Incident Infections among Community-Dwelling Adults Age 70 Years and Older: Results from the DO-HEALTH Study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2022;26(9):864–71. [CrossRef]

- Fertrin KY. Diagnosis and management of iron deficiency in chronic inflammatory conditions (CIC): is too little iron making your patient sick? Hematology [Internet]. 2020 Dec 4 [cited 2024 Oct 23];2020(1):478–86. [CrossRef]

- Kalra PR, Cleland JGF, Petrie MC, Thomson EA, Kalra PA, Squire IB, et al. Intravenous ferric derisomaltose in patients with heart failure and iron deficiency in the UK (IRONMAN): an investigator-initiated, prospective, randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint trial. Lancet. 2022 Dec 17;400(10369):2199–209. [CrossRef]

- Graham FJ, Pellicori P, Kalra PR, Ford I, Bruzzese D, Cleland JGF. Intravenous iron in patients with heart failure and iron deficiency: an updated meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023 Apr;25(4):528–37. [CrossRef]

- Ponikowski P, Kirwan BA, Anker SD, McDonagh T, Dorobantu M, Drozdz J, et al. Ferric carboxymaltose for iron deficiency at discharge after acute heart failure: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2020 Dec 12;396(10266):1895–904. [CrossRef]

- Macdougall IC, White C, Anker SD, Bhandari S, Farrington K, Kalra PA, et al. Intravenous Iron in Patients Undergoing Maintenance Hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jan 31;380(5):447–58. [CrossRef]

- Ponikowski P, van Veldhuisen DJ, Comin-Colet J, Ertl G, Komajda M, Mareev V, et al. Beneficial effects of long-term intravenous iron therapy with ferric carboxymaltose in patients with symptomatic heart failure and iron deficiency. Eur Heart J. 2015 Mar 14;36(11):657–68. [CrossRef]

- Von Haehling S, Doehner W, Evertz R, Garfias-Veitl T, Derad C, Diek M, et al. Ferric carboxymaltose and exercise capacity in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and iron deficiency: the FAIR-HFpEF trial. Eur Heart J. 2024 Oct 5;45(37):3789–800.

- Palau P, Domínguez E, López L, Ramón JM, Heredia R, González J, et al. Inspiratory Muscle Training and Functional Electrical Stimulation for Treatment of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: The TRAINING-HF Trial. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2019 Apr;72(4):288–97. [CrossRef]

- Palau P, López L, Domínguez E, Espriella R de L, Campuzano R, Castro A, et al. Exercise training response according to baseline ferrokinetics in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A substudy of the TRAINING-HF trial. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle [Internet]. 2024 Apr 1 [cited 2024 Oct 17];15(2):681–9. [CrossRef]

- Vlahakos DV, Tsioufis C, Manolis A, Filippatos G, Marathias KP, Papademetriou V, et al. Inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system in the cardiorenal syndrome with anaemia: a double-edged sword. J Hypertens. 2019 Nov;37(11):2145–53.

- Cheungpasitporn W, Thongprayoon C, Chiasakul T, Korpaisarn S, Erickson SB. Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors linked to anemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. QJM. 2015 Nov;108(11):879–84. [CrossRef]

- Tziastoudi M, Pissas G, Golfinopoulos S, Filippidis G, Dousdampanis P, Eleftheriadis T, et al. Sodium–Glucose Transporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors and Iron Deficiency in Heart Failure and Chronic Kidney Disease: A Literature Review. Life [Internet]. 2023 Dec [cited 2024 Nov 18];13(12):2338. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-1729/13/12/2338. [CrossRef]

- Yang TY, Lee CM, Wang SR, Cheng YY, Weng SE, Hsu WT. Anemia warrants treatment to improve survival in patients with heart failure receiving sacubitril-valsartan. Sci Rep. 2022 May 17;12(1):8186.

- Ezekowitz JA, Zheng Y, Cohen-Solal A, Melenovský V, Escobedo J, Butler J, et al. Hemoglobin and Clinical Outcomes in the Vericiguat Global Study in Patients With Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction (VICTORIA). Circulation. 2021 Nov 2;144(18):1489–99.

- De Martinis M, Franceschi C, Monti D, Ginaldi L. Inflamm-ageing and lifelong antigenic load as major determinants of ageing rate and longevity. FEBS Lett. 2005 Apr 11;579(10):2035–9. [CrossRef]

- McDonagh T, Damy T, Doehner W, Lam CSP, Sindone A, van der Meer P, et al. Screening, diagnosis and treatment of iron deficiency in chronic heart failure: putting the 2016 European Society of Cardiology heart failure guidelines into clinical practice. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018 Dec;20(12):1664–72. [CrossRef]

- Comín J. New Pathophysiological Pathways Involved in Iron Metabolism Disorder in Heart Failure: The IRON-PATH II Investigator Initiated Study [Internet]. clinicaltrials.gov; 2022 Dec [cited 2024 Nov 18]. Report No.: NCT05000853. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05000853.

- Xu Y, Alfaro-Magallanes VM, Babitt JL. Physiological and pathophysiological mechanisms of hepcidin regulation: clinical implications for iron disorders. Br J Haematol. 2021 Jun;193(5):882–93. [CrossRef]

- Pascale MRD, Rondinelli MB, Ascione F, Maffei V, Lorenzo DI, Scagliarini S, et al. Iron and Heart Failure: Current Concepts and Emerging Pharmacological Paradigms. World Journal of Cardiovascular Diseases [Internet]. 2024 Apr 12 [cited 2024 Nov 18];14(4):195–216. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=132466. [CrossRef]

- Docherty KF, Welsh P, Verma S, De Boer RA, O’Meara E, Bengtsson O, et al. Iron Deficiency in Heart Failure and Effect of Dapagliflozin: Findings From DAPA-HF. Circulation. 2022 Sep 27;146(13):980–94. [CrossRef]

- Angermann CE, Santos-Gallego CG, Requena-Ibanez JA, Sehner S, Zeller T, Gerhardt LMS, et al. Empagliflozin effects on iron metabolism as a possible mechanism for improved clinical outcomes in non-diabetic patients with systolic heart failure. Nat Cardiovasc Res. 2023 Nov;2(11):1032–43. [CrossRef]

- Zeng J, Zhu Y, Zhao W, Wu M, Huang H, Huang H, et al. Rationale and Design of the ADIDAS Study: Association Between Dapagliflozin-Induced Improvement and Anemia in Heart Failure Patients. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2022 Jun;36(3):505–9. [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Figal D, Núñez J, Pérez-Martínez MT, González-Juanatey JR, Taibo-Urquia M, Llàcer Iborra P, et al. Colchicine in acutely decompensated heart failure: the COLICA trial. Eur Heart J. 2024 Aug 30;ehae538. [CrossRef]

- Xing MD G. A Randomized, Parallel Controlled Trial of Roxadustat Combined with Sacubitril Valsartan Sodium Tablets in the Treatment of Cardiorenal Anemia Syndrome [Internet]. clinicaltrials.gov; 2021 Sep [cited 2024 Dec 13]. Report No.: NCT05053893. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05053893.

- Ren J. Study of the Safety and Efficacy of Roxadustat in the Treatment of Heart Failure With Chronic Kidney Disease and Anemia [Internet]. clinicaltrials.gov; 2023 Jan [cited 2024 Dec 13]. Report No.: NCT05691257. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05691257.

Figure 1.

Inflammation and Its Role in Heart Failure with Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction. Acute inflammation, triggered by events such as heart attacks, is more closely associated with the development of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), while chronic inflammation is more commonly linked to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Both types of inflammation, along with their respective forms of heart failure, contribute to impaired heart function and iron deficiency, which further exacerbates cardiac dysfunction. AMI (acute myocardial infarction), DAMPs (damage-associated molecular patterns), HFpEF (heart failure with preserved ejection fraction), HFrEF (heart failure with reduced ejection fraction), IL-1 (interleukin-1), IL-6 (interleukin-6), LAMPs (lifestyle-associated molecular patterns), and TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor-alpha).

Figure 1.

Inflammation and Its Role in Heart Failure with Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction. Acute inflammation, triggered by events such as heart attacks, is more closely associated with the development of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), while chronic inflammation is more commonly linked to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Both types of inflammation, along with their respective forms of heart failure, contribute to impaired heart function and iron deficiency, which further exacerbates cardiac dysfunction. AMI (acute myocardial infarction), DAMPs (damage-associated molecular patterns), HFpEF (heart failure with preserved ejection fraction), HFrEF (heart failure with reduced ejection fraction), IL-1 (interleukin-1), IL-6 (interleukin-6), LAMPs (lifestyle-associated molecular patterns), and TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor-alpha).

Figure 2.

Main effects and interactions associated with heart failure in older patients: inflammation and iron deficiency. Older patients with heart failure experience renal changes, fluid retention, anorexia, poor nutrient absorption, cachexia, and immune and cytokine dysregulation, leading to a chronic inflammatory state. Additionally, due to age-related processes, they are affected by factors such as an excess of reactive oxygen species and cellular senescence, which contribute to systemic and chronic inflammation. Combined with medications used to treat heart failure, these factors result in anemia and functional iron deficiency, leading to increased mortality and hospitalizations in heart failure patients. AcSDKP (N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline), ACE-I (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors), ARB (angiotensin receptor blockers), DAMPs (damage-associated molecular patterns), GFR (glomerular filtration rate), IL-1β (interleukin-1β), IL-6 (interleukin-6), ROS (reactive oxygen species), and SGLT2 (sodium-glucose cotransporter 2).

Figure 2.

Main effects and interactions associated with heart failure in older patients: inflammation and iron deficiency. Older patients with heart failure experience renal changes, fluid retention, anorexia, poor nutrient absorption, cachexia, and immune and cytokine dysregulation, leading to a chronic inflammatory state. Additionally, due to age-related processes, they are affected by factors such as an excess of reactive oxygen species and cellular senescence, which contribute to systemic and chronic inflammation. Combined with medications used to treat heart failure, these factors result in anemia and functional iron deficiency, leading to increased mortality and hospitalizations in heart failure patients. AcSDKP (N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline), ACE-I (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors), ARB (angiotensin receptor blockers), DAMPs (damage-associated molecular patterns), GFR (glomerular filtration rate), IL-1β (interleukin-1β), IL-6 (interleukin-6), ROS (reactive oxygen species), and SGLT2 (sodium-glucose cotransporter 2).

Table 1.

Differences in Inflammatory Mechanisms in HFrEF and HFpEF.

Table 1.

Differences in Inflammatory Mechanisms in HFrEF and HFpEF.

| Aspect |

HFrEF |

HFpEF |

| Type of Inflammation |

Primarily acute and chronic low-grade inflammation |

Chronic low-grade inflammation |

| Triggering Events |

AMI leading to intense inflammatory response |

Comorbidities and lifestyle factors create an unresolved inflammatory state |

| Primary Targets |

Cardiomyocytes, leading to apoptosis and necrosis |

Endothelial cells and interstitial tissue |

| Mechanism of Action |

Pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) promote inflammation and cell infiltration |

Increased myocardial stiffness and fibrosis due to chronic inflammation |

| Outcomes of Inflammation |

Eccentric remodeling, ventricular dilation, and decreased contractile function |

Impaired diastolic function and increased myocardial stiffness

|

| Patterns mainly associated |

PAMPs and DAMPs |

DAMPs with LAMPs |

| Influencing Factors |

Focused on myocardial damage and inflammatory cell infiltration |

Systemic syndrome influenced by aging, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and atrial fibrillation

|

Table 2.

Key clinical trials supporting intravenous iron therapy in heart failure. Evidence from “2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for diagnosing and treating acute and chronic heart failure”. ID: Iron Deficiency; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; T: TSAT, transferrin saturation (%); F: ferritin (µg/L); CVM, cardiovascular mortality; HHF, hospitalization for heart failure; IV, intravenous.

Table 2.

Key clinical trials supporting intravenous iron therapy in heart failure. Evidence from “2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for diagnosing and treating acute and chronic heart failure”. ID: Iron Deficiency; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; T: TSAT, transferrin saturation (%); F: ferritin (µg/L); CVM, cardiovascular mortality; HHF, hospitalization for heart failure; IV, intravenous.

| Study |

Number of patients

(n) |

Patient Population and ID definition |

Intervention |

Primary Outcomes |

Key Findings |

IRONMAN

(2022)

(48) |

1137 |

HF patients (LVEF ≤ 45%).

T <20% + F <400 or F <100 |

Ferric derisomaltose vs. usual care |

Composite of total HF hospitalizations and CVM |

RR 0.82 (95% CI 0.66–1.02; P=0.070); significant benefit post-COVID-19 analysis (HR 0.76, P=0.047) in reducing primary endpoint. |

Graham et al. (2023)

(49) |

3373 |

Meta-analysis

10 trials

F <100 or F 100–300 + T <20%

IRONMAN also allowed T <20% F <400. |

IV iron therapy vs. standard care |

Composite of total HHF and CVM. |

IV iron reduced total HHF and CVM (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.61–0.93; P < .01); first HF hospitalization or CV death (OR 0.72, P=0.04). |

AFFIRM-AHF

(2020)

(50) |

1108 |

HF patients (LVEF < 50%)

F <100 or T <20% + F 100–299 |

Ferric carboxymaltose vs. placebo |

Total HF hospitalizations and CVM |

Ferric carboxymaltose reduced the risk of first heart failure hospitalization (RR 0.74; 95% CI 0.58–0.94; p=0.013) and recurrent hospitalizations. |

PIVOTAL (2019)

(51) |

2141 |

End-stage CKD patients on hemodialysis

F < 400 T < 30%, and receiving erythropoiesis-stimulating agents |

High-dose IV iron vs. low-dose iron |

First and recurrent HF events |

High-dose IV iron reduced HHF (HR: 0.66; 95% CI: 0.48–0.91; p = 0.01) in hemodialysis patients. |

CONFIRM-HF (2015)

(52) |

301 |

HF patients (LVEF ≤45%)

F <100 or T <20% + F 100–300 |

Ferric carboxymaltose vs. placebo |

Change in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) at 24 weeks |

Significant improvement in 6MWD (+33±11 m, P=0.002); reduced HHF. HR 0.39; 95% CI: 0,19–0,82; p = 0,009. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).