Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Wholesale Electricity Markets

- Electricity energy markets - Long-term power purchase agreements, day-ahead markets, and real-time/balancing markets facilitate the buying and selling of electricity for final consumption.

- Reliability/Capacity markets - Capacity obligations are purchased through centralized auctions and bilateral contracts to ensure adequate generation and demand-side resources are available to meet system reliability requirements.

- Ancillary services markets - Grid resources bid or agree on bilateral contracts to provide essential reliability services like frequency regulation, operating reserves, voltage support, and black start.

- Transmission markets - Prices for transmission networks, like access rights, are determined to efficiently manage grid congestion and losses.

2.1. Day-Ahead and Real-Time/Balancing Markets

- Operate the day before electricity delivery (hence “day-ahead”).

- Participants submit bids to buy or offers to sell electricity for each hour of the next day.

- The system operator matches supply and demand for each hour to determine the market clearing price at the minimum cost, safeguarding system reliability and electricity transmission constraints.

- Provides price signals for generators and load-serving entities to plan their operations and bidding for the next day.

- Results in financial commitments to buy or sell electricity at the day-ahead price.

- Operate in real time as electricity is delivered, with intervals that can be 5 minutes.

- The ISO/RTO uses it to balance differences between day-ahead schedules and real-time demand/generation at the minimum cost, safeguarding system reliability and electricity transmission constraints.

- Prices fluctuate minute-to-minute based on actual system conditions.

- Generators are paid the real-time price for any extra electricity produced.

- Load-serving entities pay the real-time price for any extra electricity consumed.

- Provides price signals to incentivize generators to follow dispatch instructions.

- Day-ahead prices are based on expected conditions and bids, whereas real-time prices reflect actual conditions.

- Day-ahead markets provide financial certainty, while real-time markets balance physical differences.

- Day-ahead markets have higher trade volumes, while real-time markets ensure reliability.

- Day-ahead prices are generally less volatile than real-time prices.

2.2. Capacity Market

- Market Efficiency: Supporters of capacity markets argue that these mechanisms ensure sufficient generation capacity to meet peak demand, thereby maintaining grid reliability. Critics contend that capacity markets can distort price signals, potentially leading to costly overinvestment in unnecessary capacity.

- Cost to Consumers: Proponents believe capacity markets promote long-term price stability and secure supply, benefiting consumers in the long run. Detractors, however, argue that these markets increase consumer costs by compensating generators for potential capacity rather than actual production, which may not always be economically justified.

- Impact on Renewable Energy: Capacity markets can, some argue, facilitate renewable integration by ensuring a reliable backup capacity. Yet, others warn that capacity markets tend to favor traditional fossil fuel generators, potentially slowing the transition to cleaner energy sources.

- Complexity of Market Design: Advocates assert that capacity markets can be tailored to meet specific regional needs and policy goals, helping to stabilize prices that might otherwise become volatile under scarcity pricing alone. Conversely, critics argue that capacity markets add unnecessary complexity to electricity markets, creating opportunities for manipulation by market participants.

- Impact on Innovation: Capacity markets may provide revenue certainty, potentially encouraging investment in new technologies. However, some argue they may stifle innovation by favoring established technologies and existing market structures over more disruptive advancements.

2.3. Long-Term Purchase Agreements

2.4. Ancillary Services Market

2.5. Cost Base Centralized Systems

2.6. Transmission Markets

- (a)

-

Open Access Interconnection Lines are essential infrastructure for interregional power exchanges and market integration. They provide non-discriminatory access to all qualified market participants, usually under regulated tariffs. Examples include:

- US interstate transmission lines under FERC Order 888 [68].

- European cross-border interconnectors are regulated by EU Regulation 714/2009 [69].

- Chile’s north-south interconnection system, Sistema Eléctrico Nacional (SEN) [70].

- Australian interstate connectors in the National Electricity Market (NEM) [71].

- (b)

- Dedicated Transmission Lines (Generator Lead Lines) connect specific generation facilities to the main grid or load centers. Usually funded and owned by the generator, these lines often have limited third-party access. Examples include lines that connect remote renewable projects, large thermal power plants, and mining operations.

- (c)

- Shared Access (Limited Participation) lines serve multiple users under restricted access schemes. Costs for these lines are typically shared among pre-defined users, and private agreements with possible regulatory oversight often govern them. Examples include shared infrastructure for mining companies or industrial parks.

- (d)

- Hybrid Access Lines: These lines blend dedicated use with open access requirements, where the primary capacity is reserved for an anchor user, but excess capacity is available for others through open access provisions. This often requires regulatory approval and may include compensation mechanisms for the original investor.

- Transmission Market Structures: Financial Instruments vs. Centralized Expansion

- Chile: The Coordinador Eléctrico Nacional (CEN) centrally plans transmission expansions, applying uniform tariffs across all users [72]Error! Reference source not found..

- Brazil: Transmission is centrally regulated by Agência Nacional de Energia Elétrica (ANEEL), with expansion carried out through public auctions [73].

- Mexico: Centro Nacional de Control de Energía (CENACE) manages grid operations and expansion, using a postage stamp system to allocate transmission costs [74].

- Decentralized Markets: The US and parts of Europe use financial instruments (FTRs/CRRs) to manage congestion, offering flexibility for market participants to hedge against transmission risks.

- Centralized Markets: Chile, Brazil, and Mexico rely on centralized planning with uniform cost distribution and without financial tools for hedging congestion risks.

- System Reliability and Congestion Management

- Transmission Market Evolution

3. Decarbonization in Electricity Market and Trends

- Larger Capacity and Operating Reserves per GWh

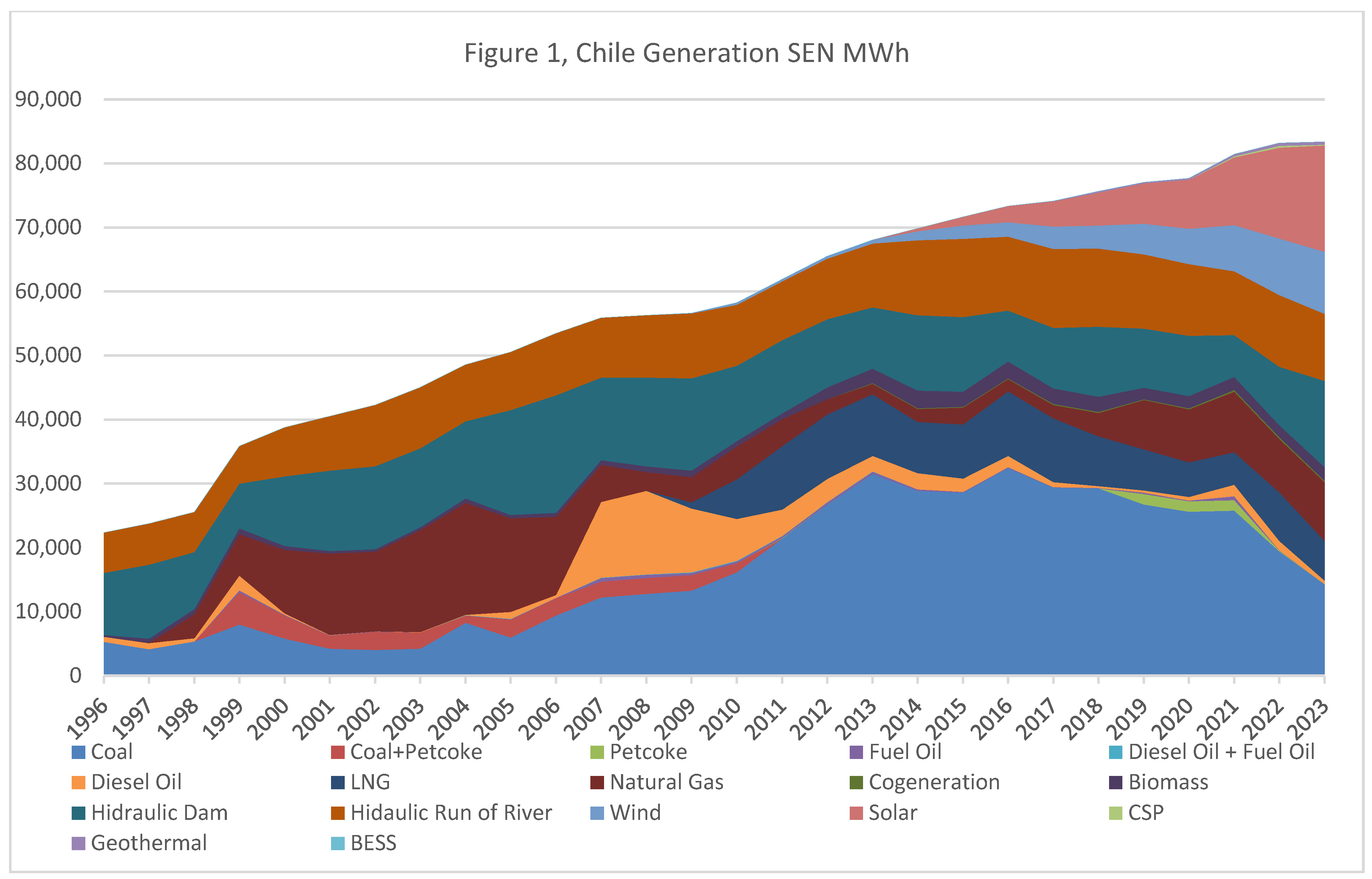

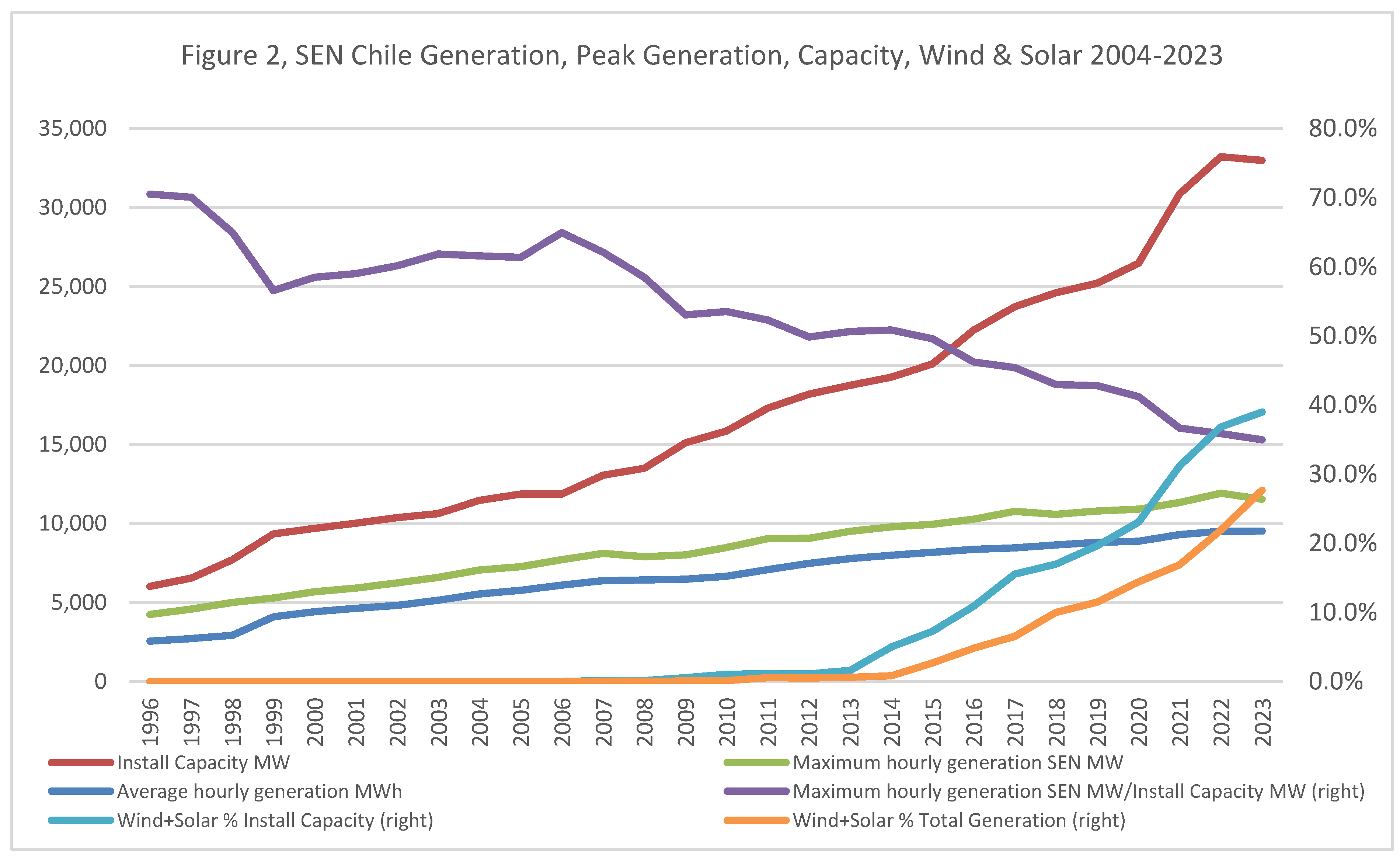

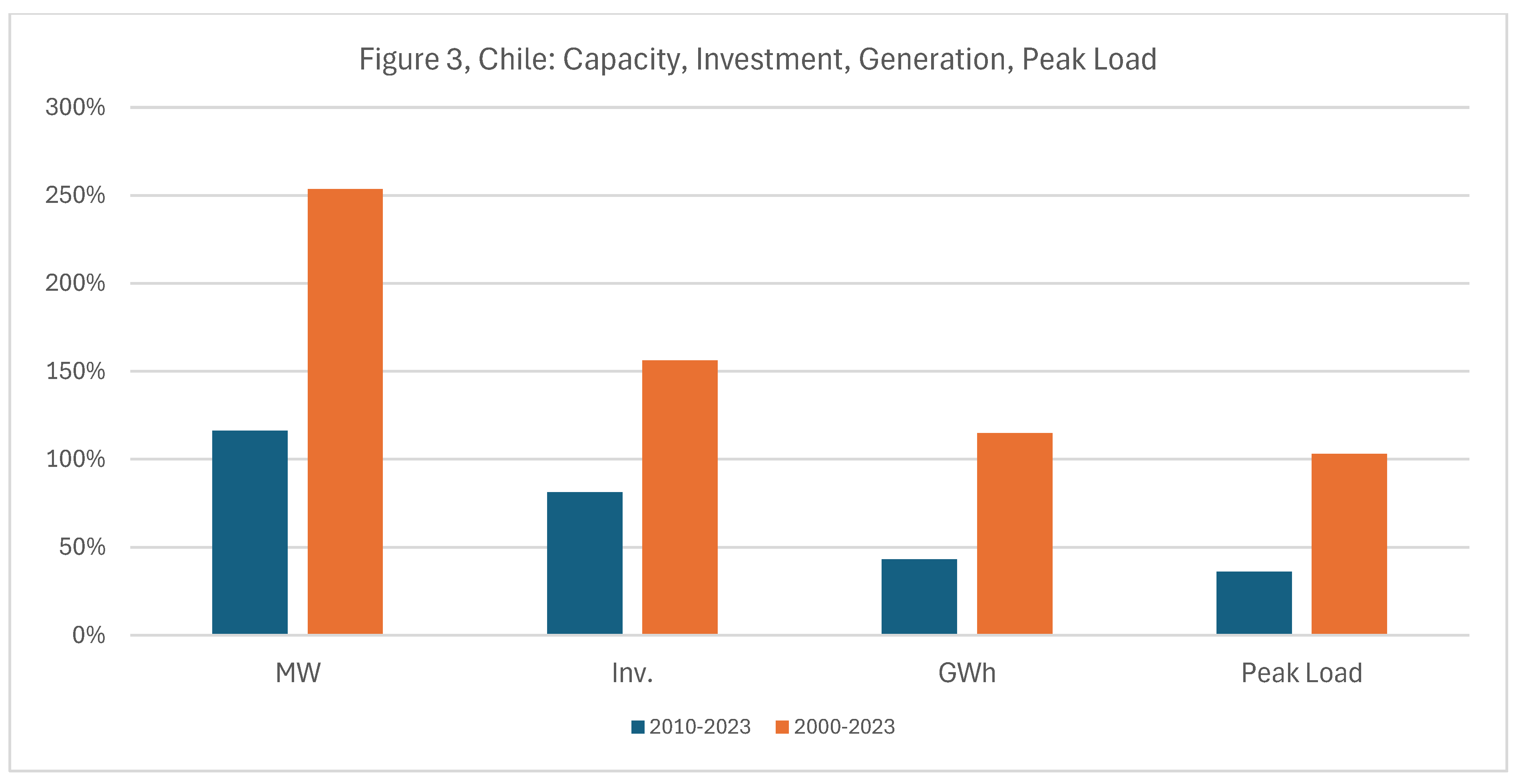

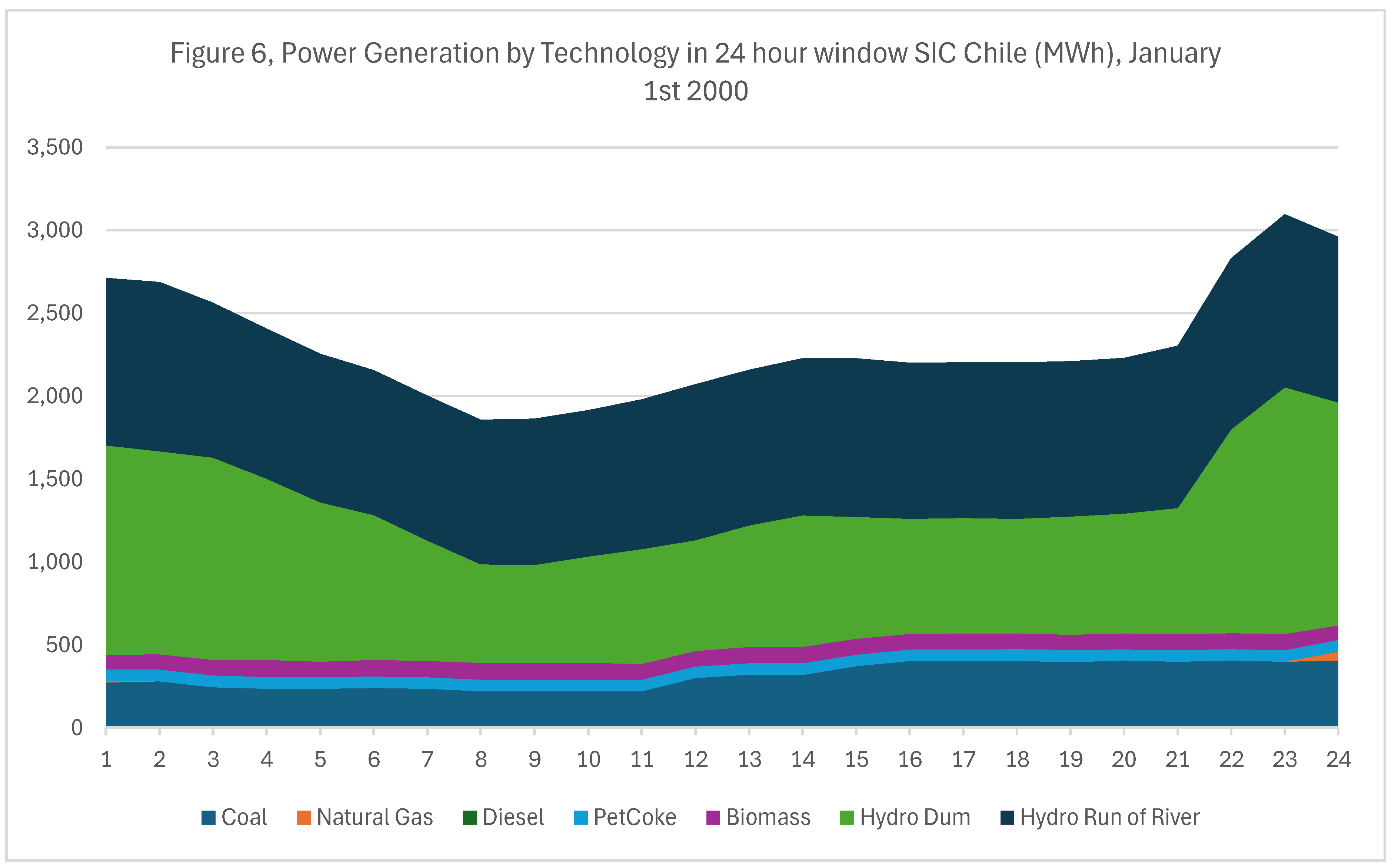

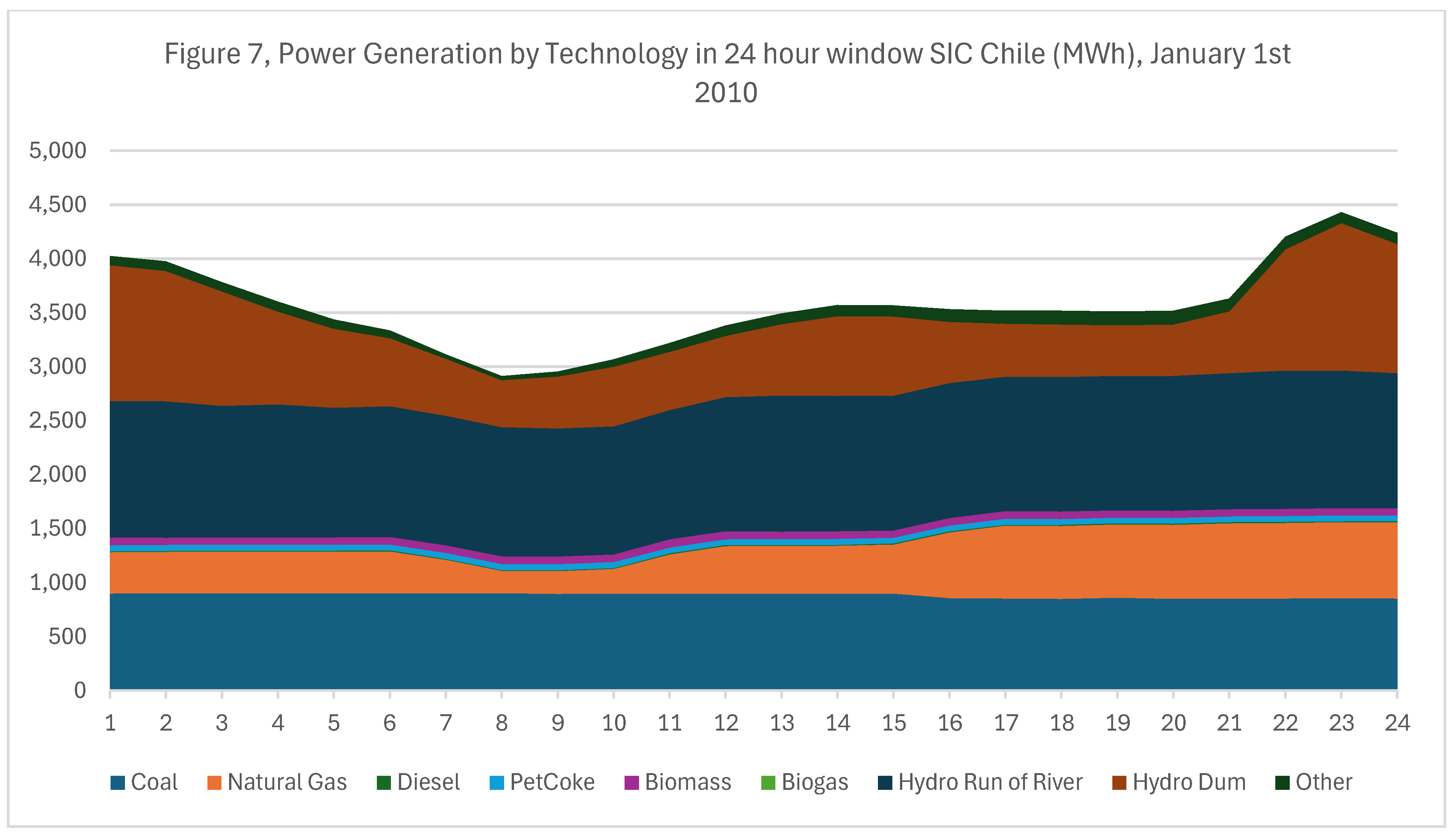

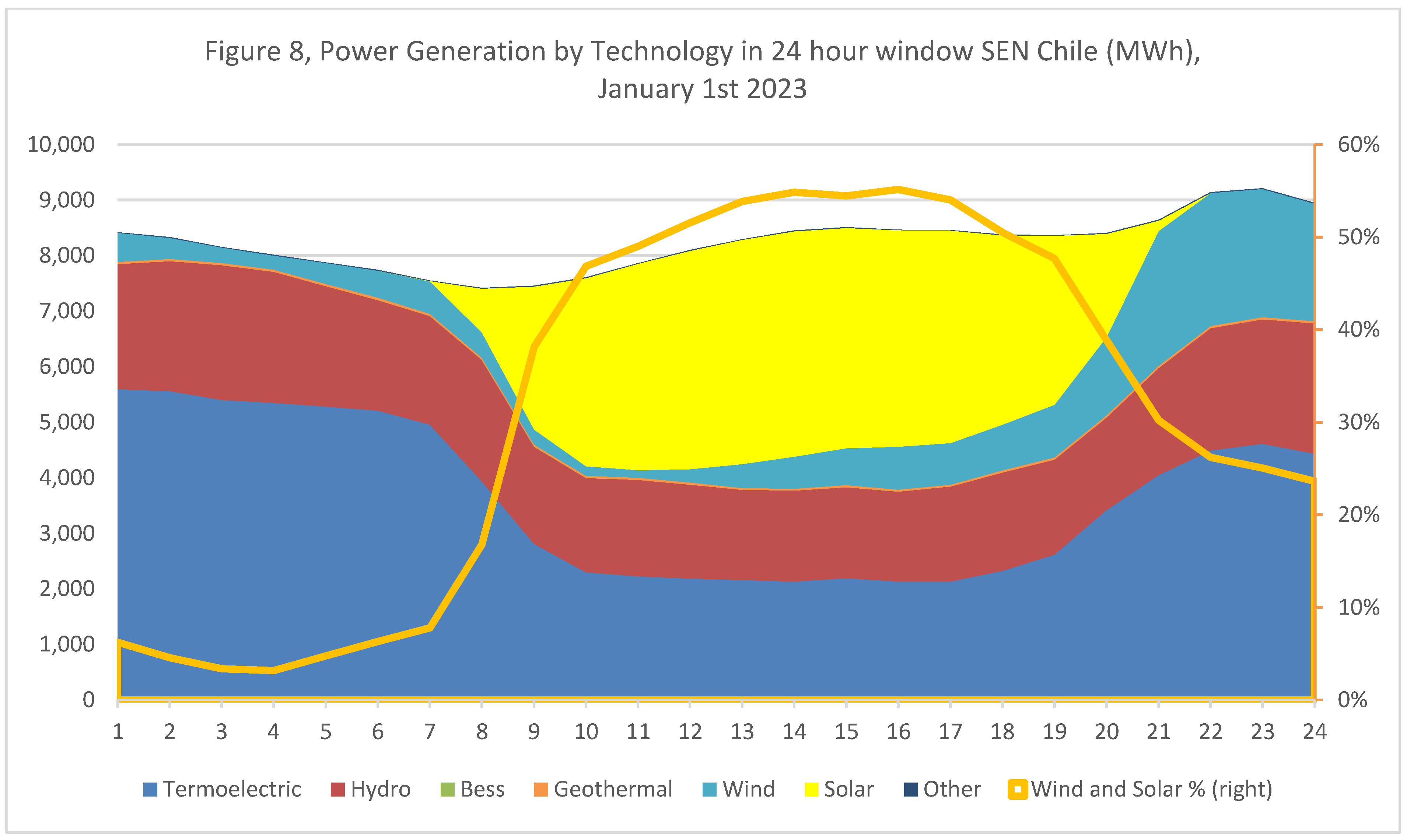

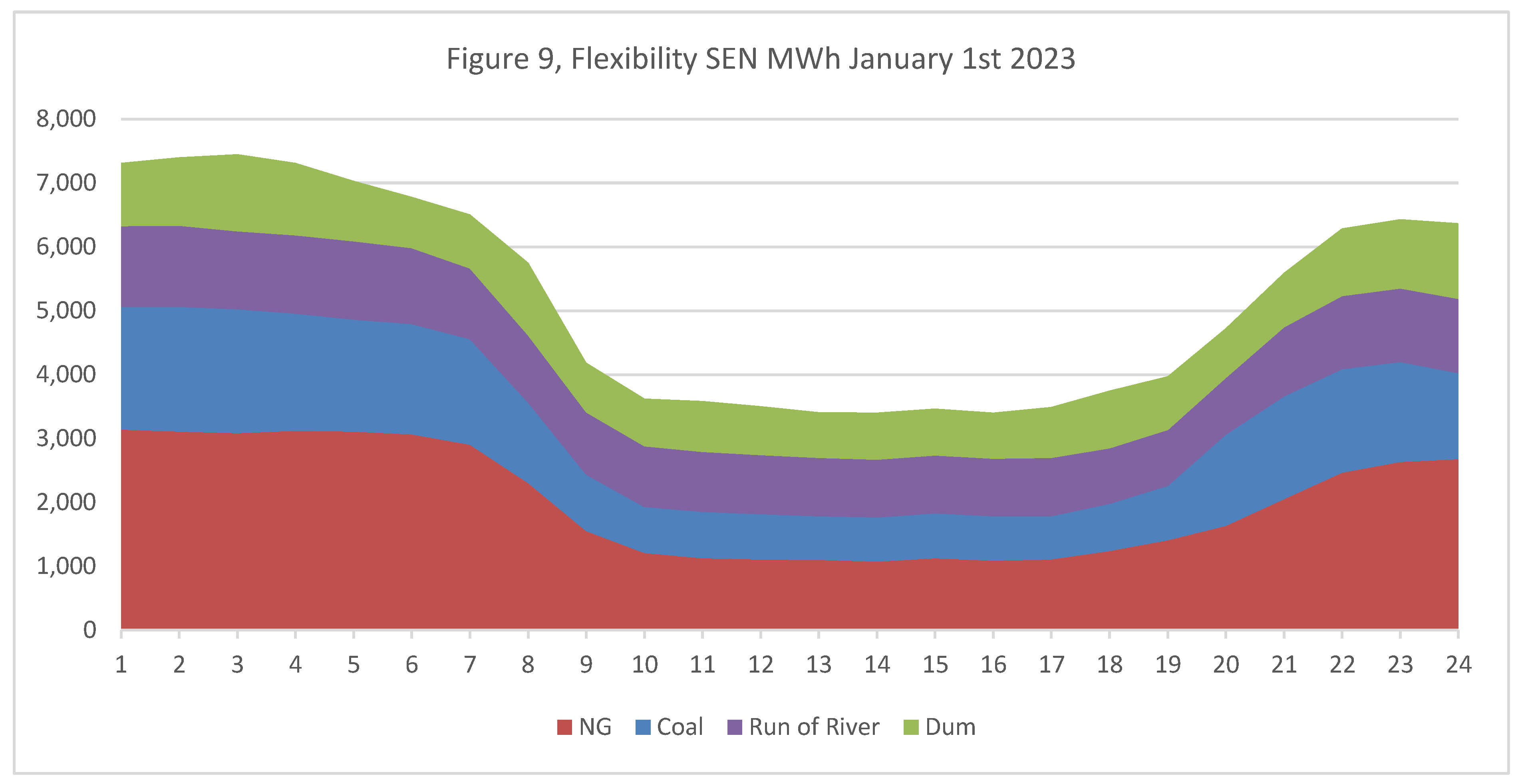

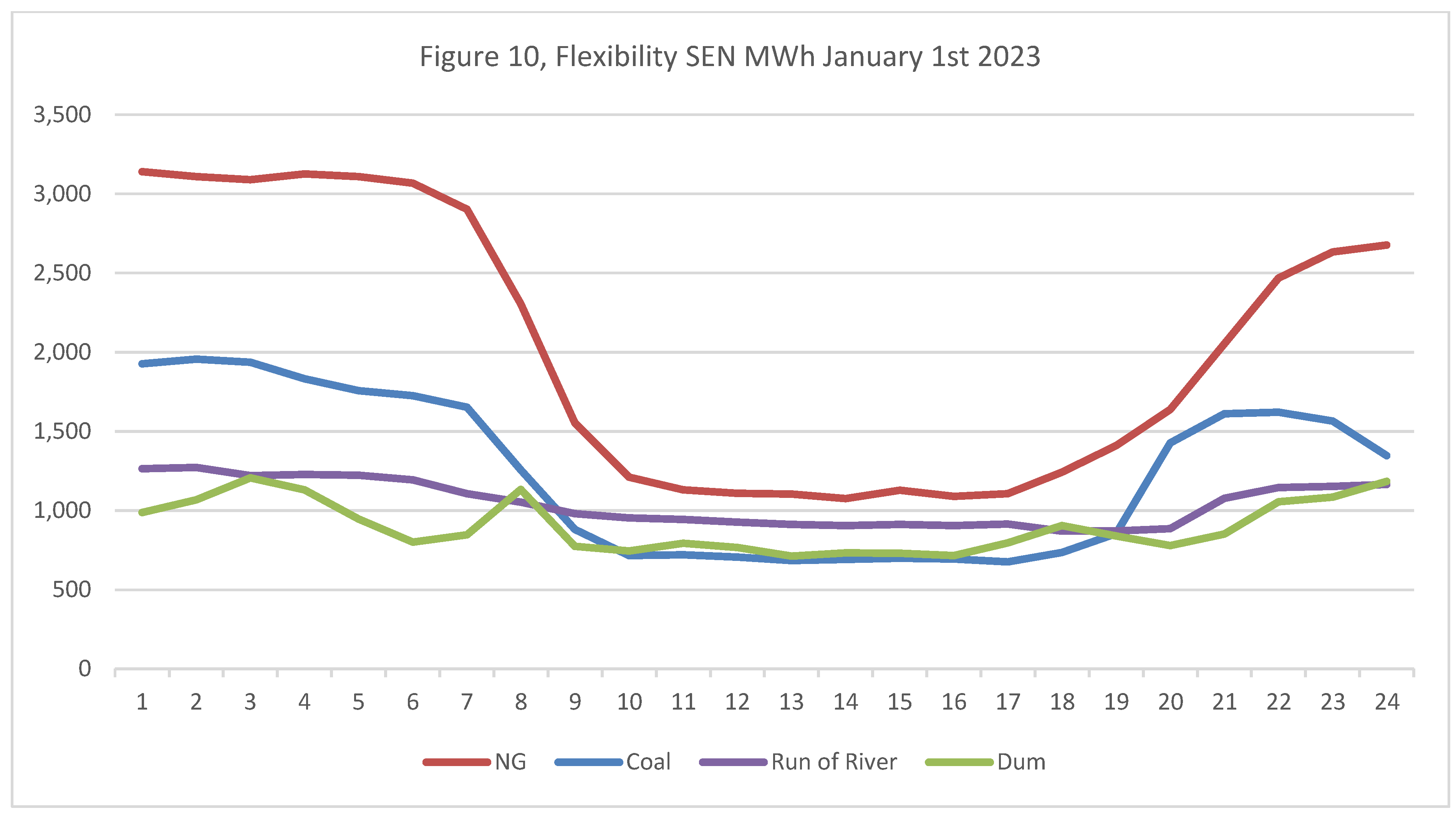

- Chile’s Case Study

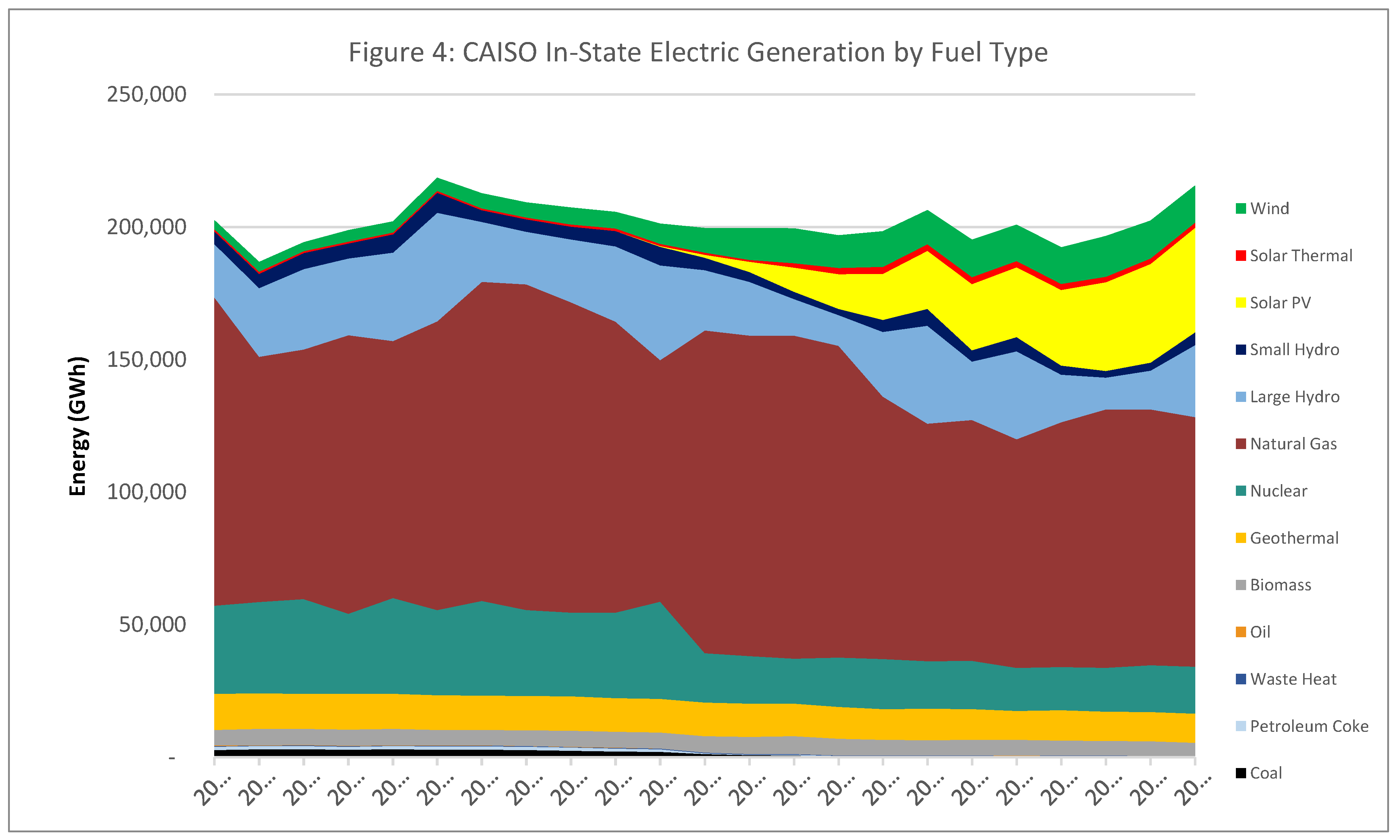

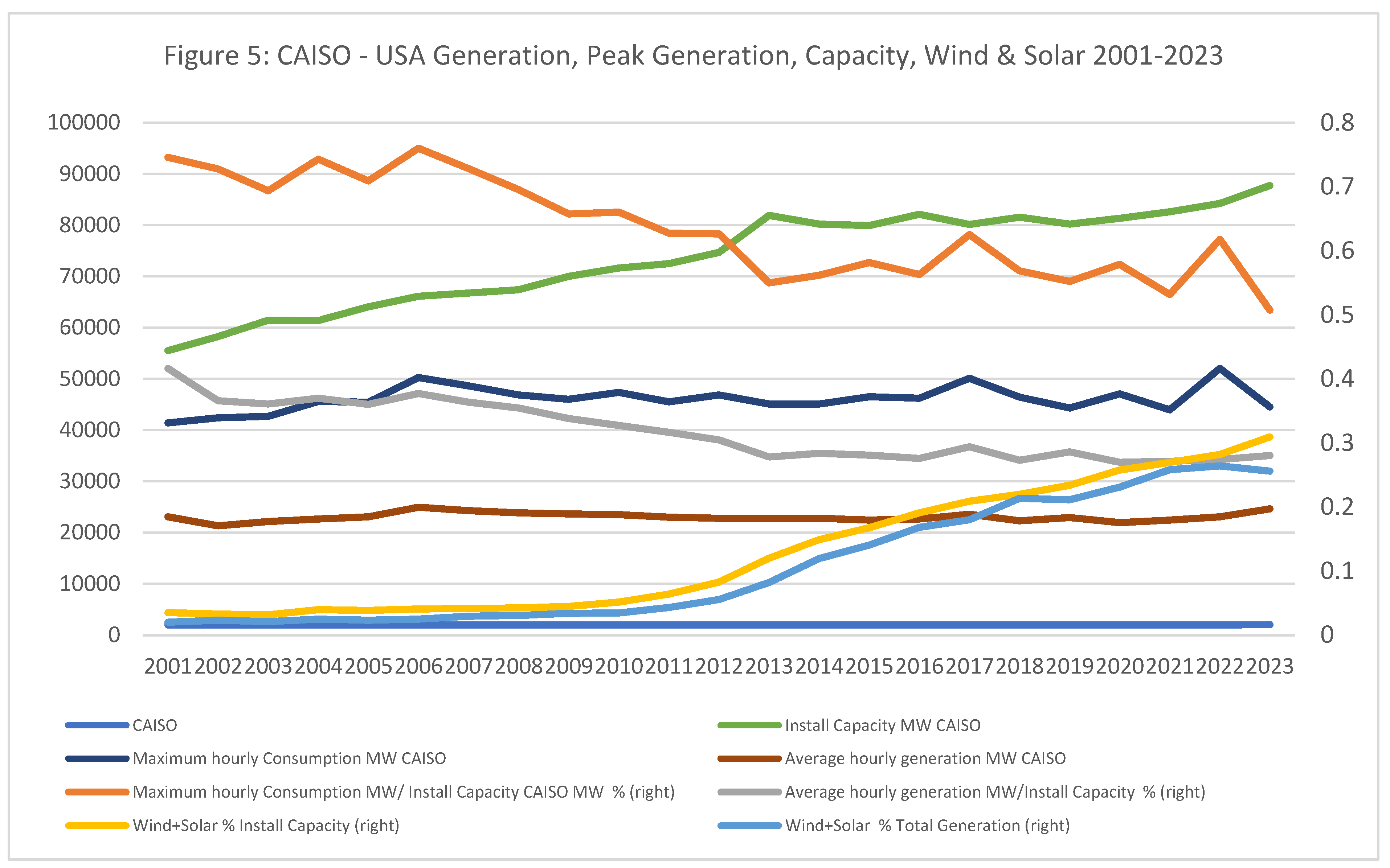

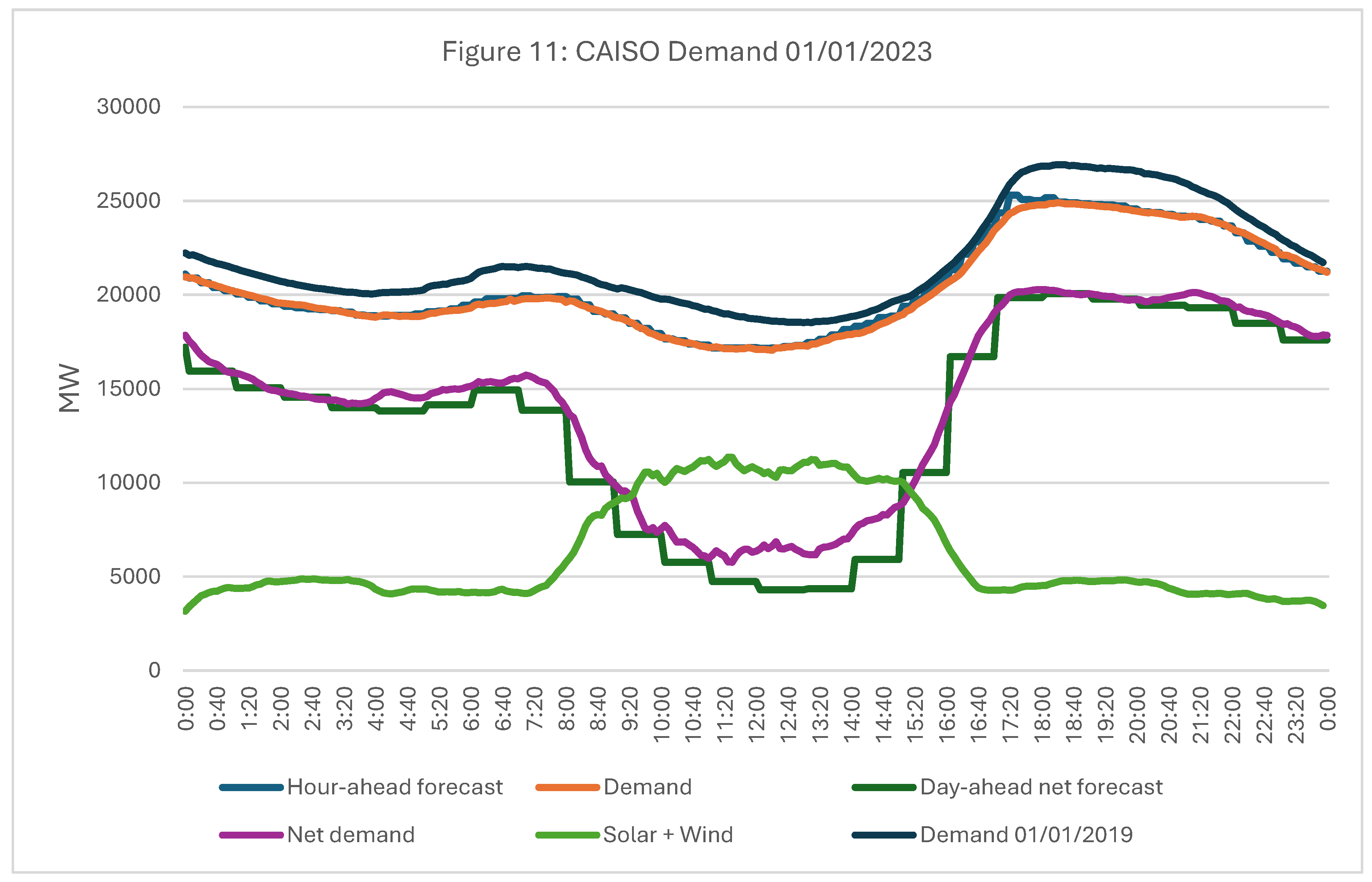

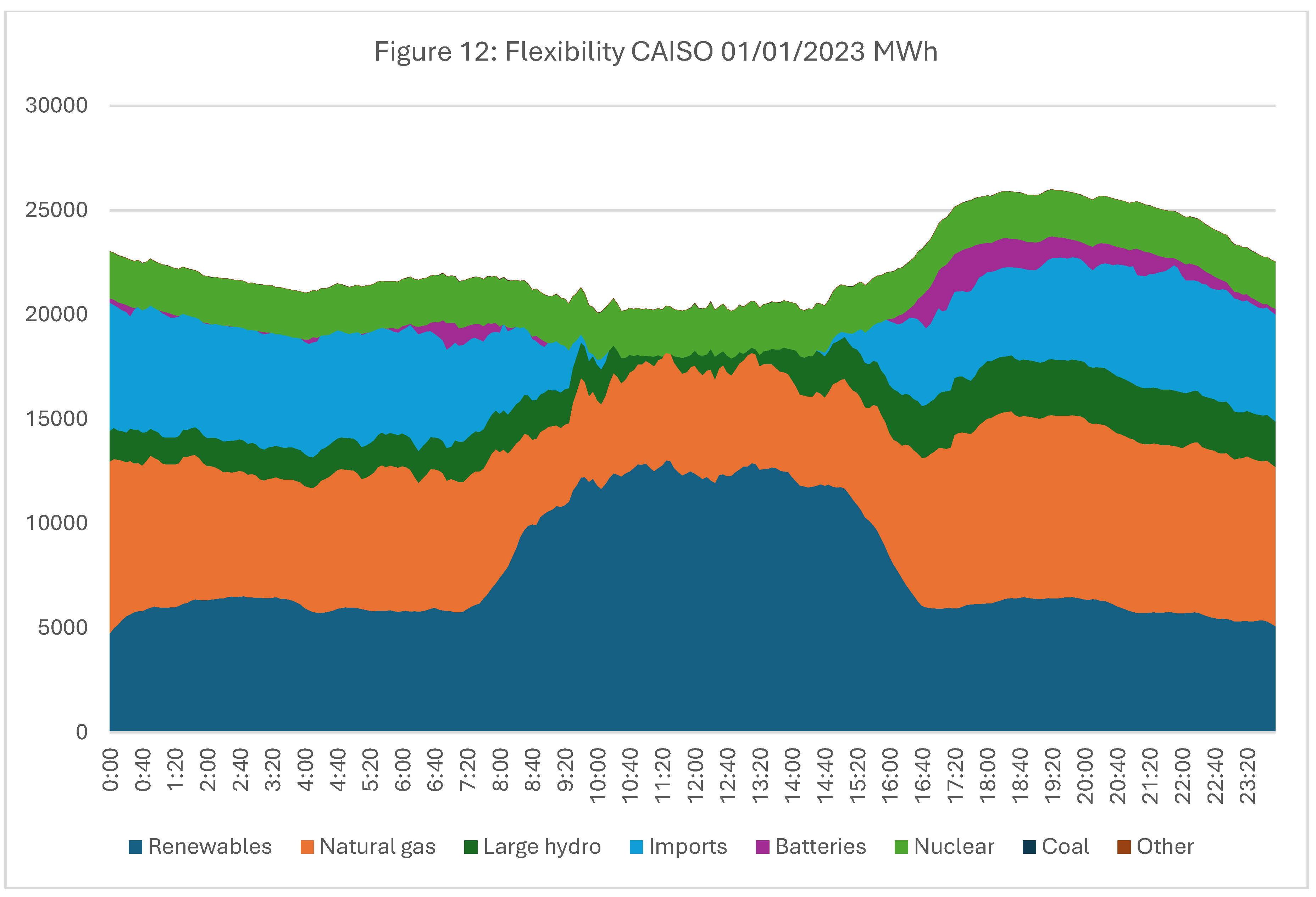

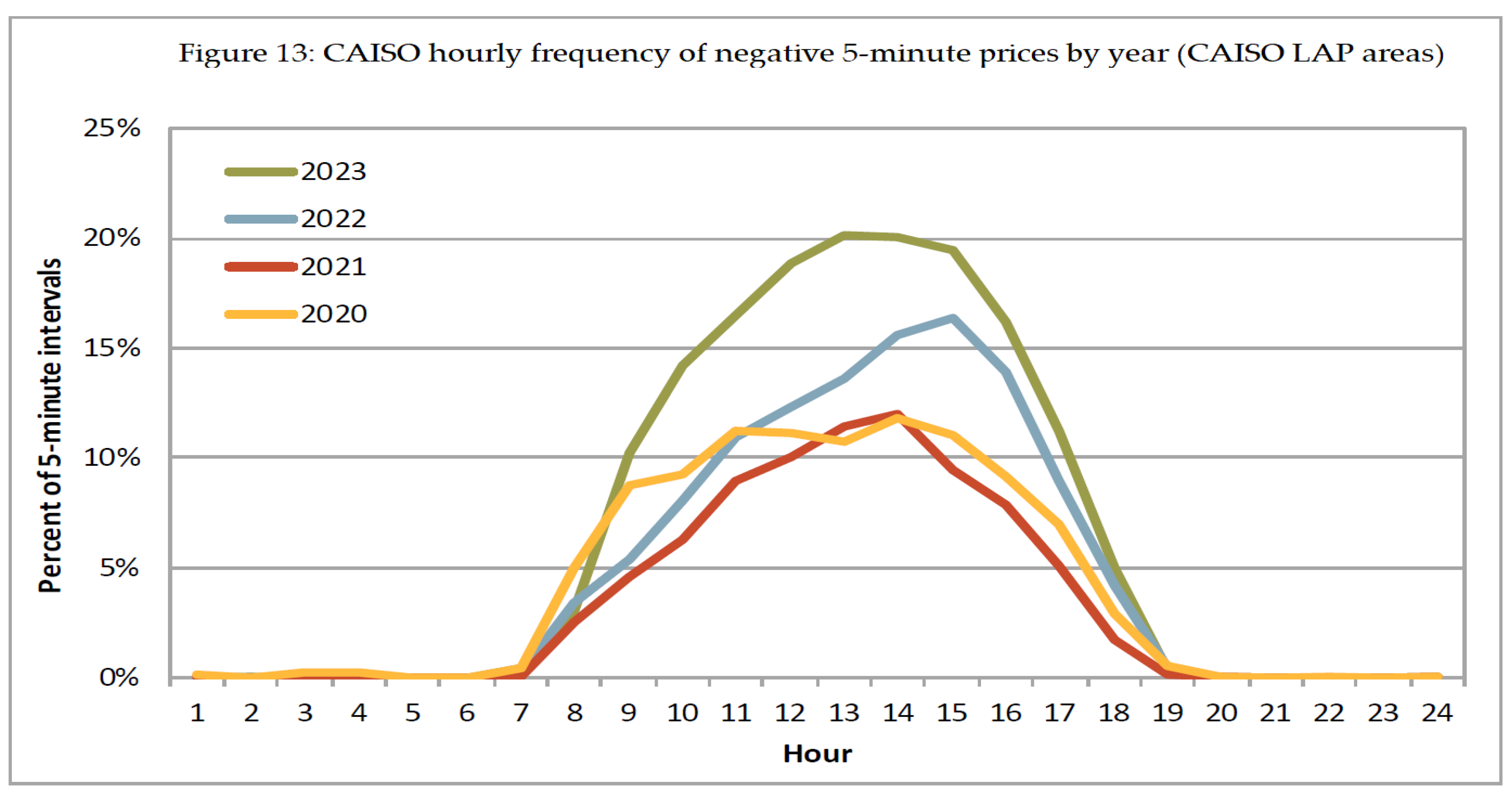

- CAISO Case Study

- Ramping Capacity Needs and Operating Reserves

- Balancing costs: The expenses for ancillary services needed to stabilize the grid include load-following and managing unforeseen fluctuations.

- Capacity costs: Backup generation and storage are required during low VRE output periods to ensure reliability.

- Transmission and distribution costs: Upgrading grid infrastructure to accommodate the increasing number of small power plants, DG systems, and behind-the-meter VRE sources.

- Operational costs: Coordinating a diverse and larger array of power generators, energy storage, prosumers, and demand management systems.

- Curtailment costs: Managing surplus generation when VRE output exceeds demand, leading to curtailment or the need for investment in energy storage.

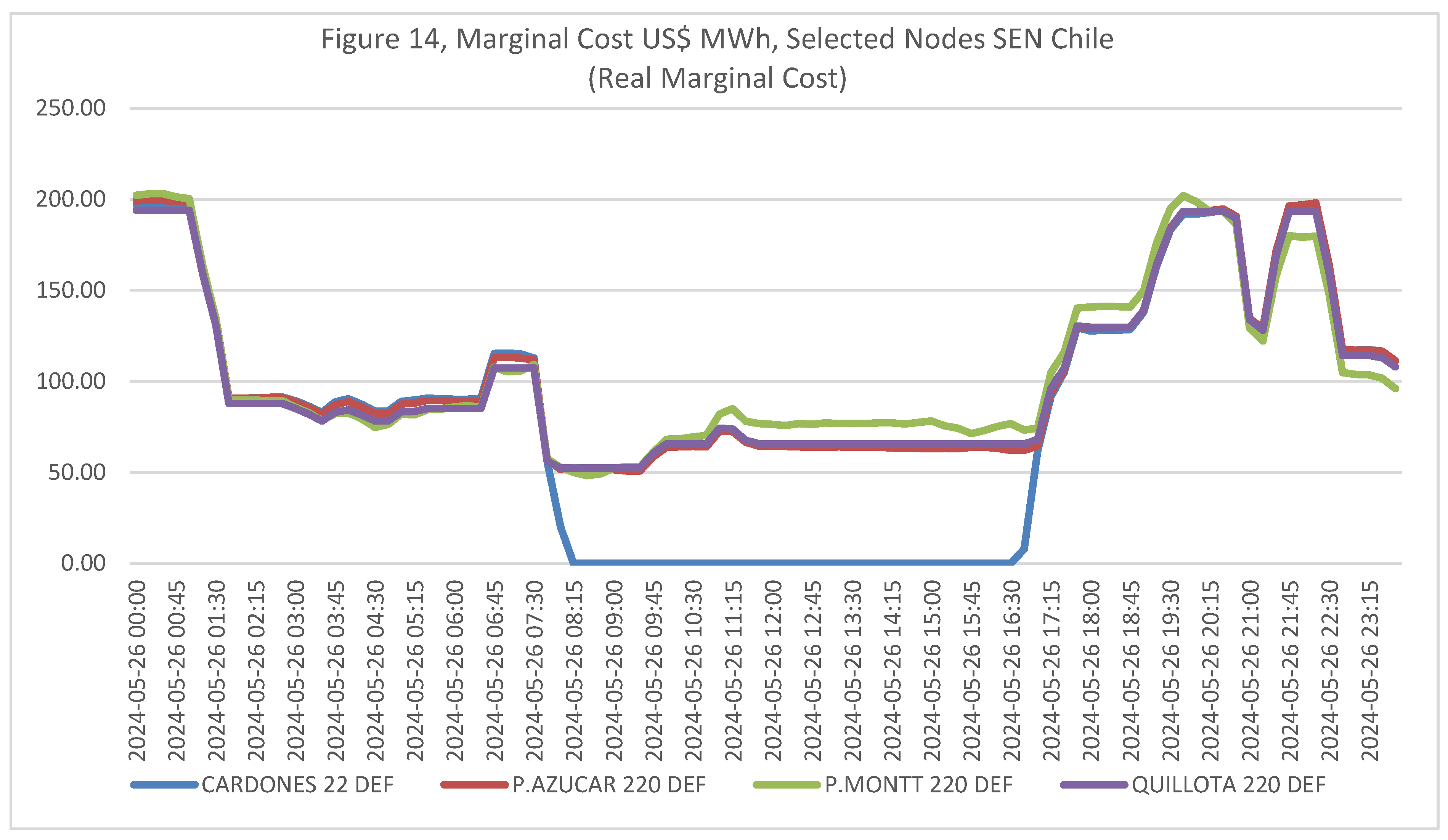

- Chile’s Case Study

- Caiso Case Study

- Discrepancies within day-ahead and real-time markets

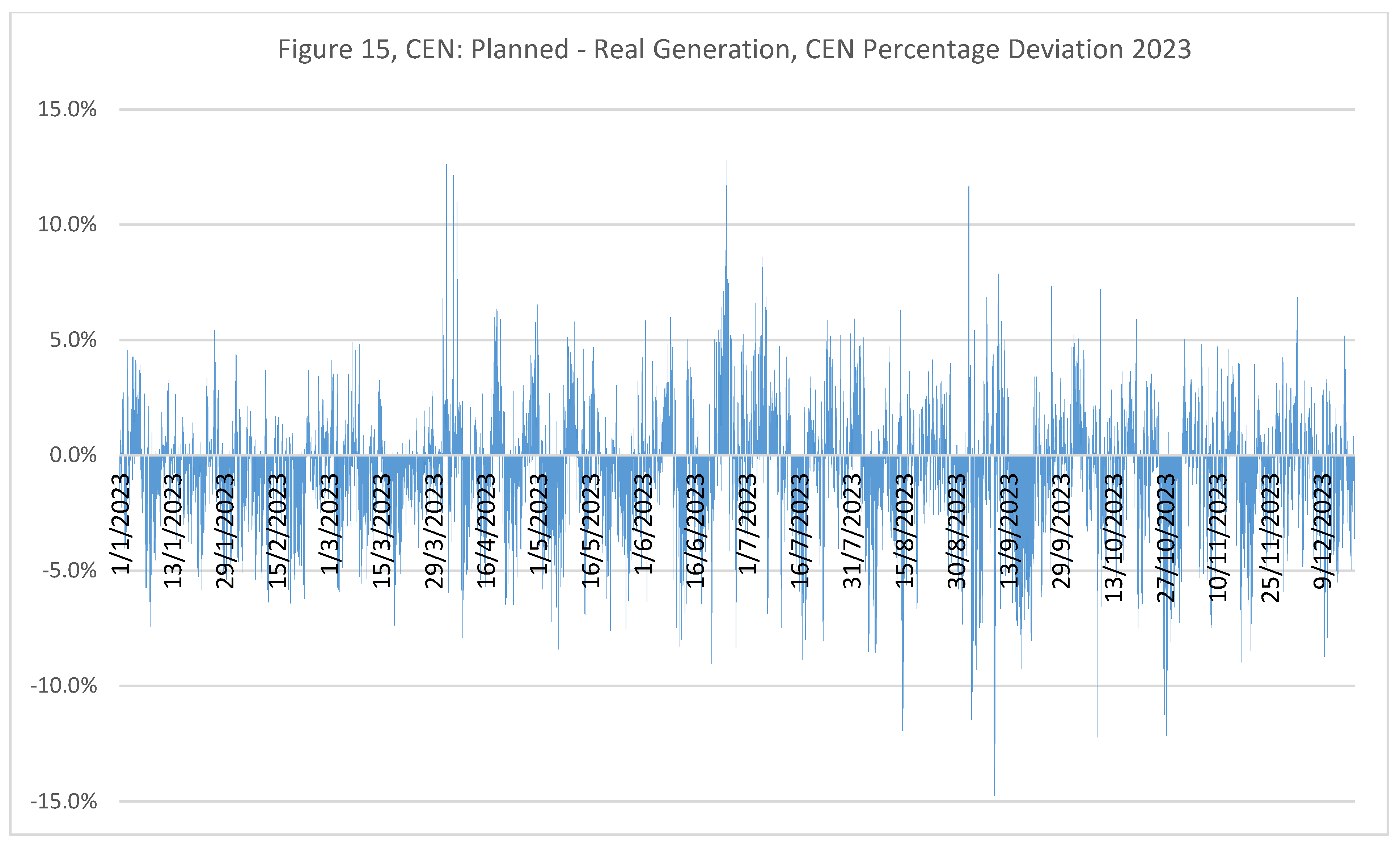

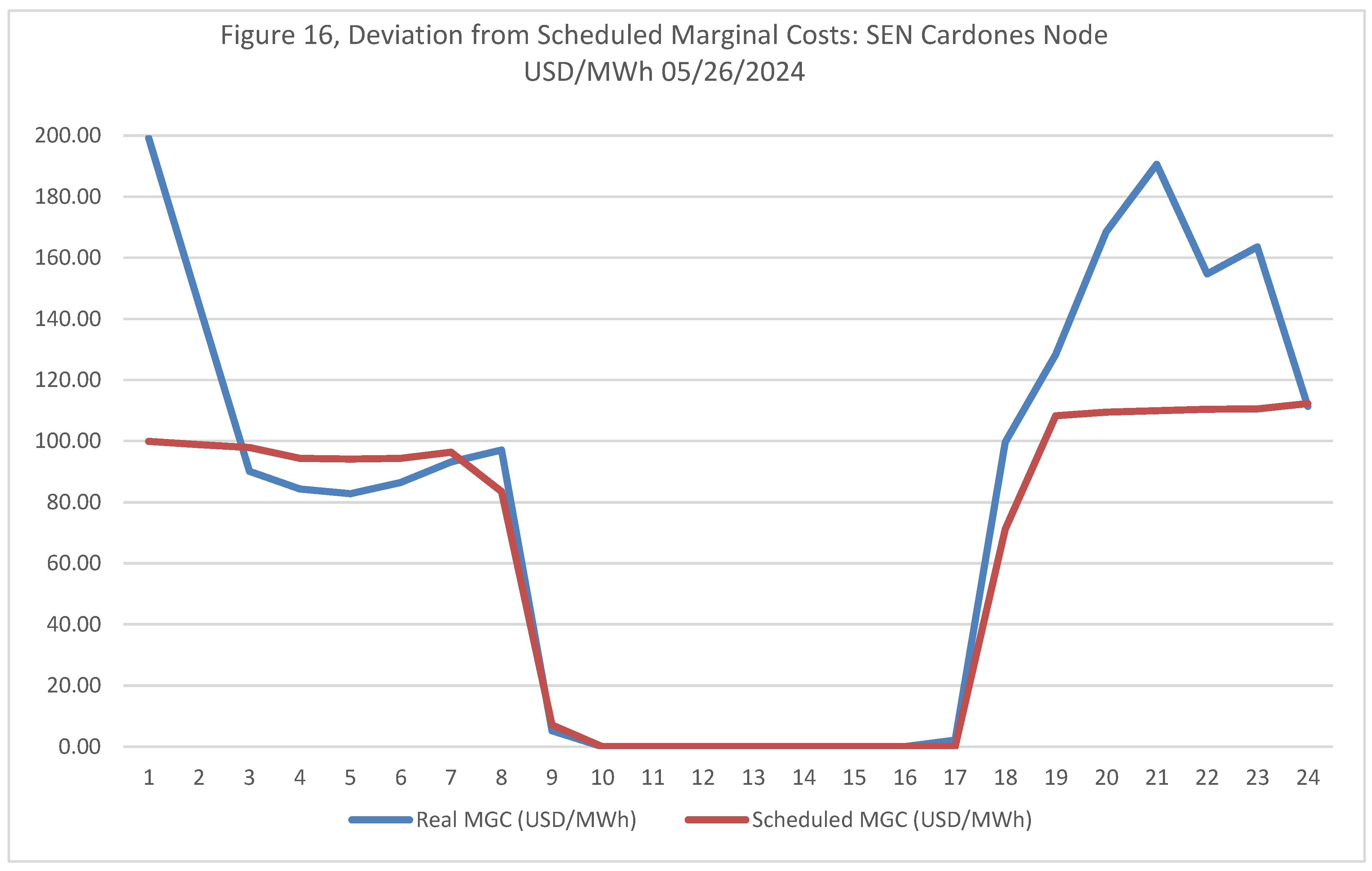

- Chile’s Case Study

4. Implications of Decarbonization for Electricity Market Design

- 1)

- Day-Ahead and Real-Time/Balancing Markets: Decarbonization significantly impacts day-ahead and real-time/balancing electricity markets, requiring enhanced flexibility, forecasting, and market design. The variability and uncertainty of increased VRE requires flexible generation, ramping capabilities, and operating reserves, supported by improved weather and climate forecasting for day-ahead planning. However, real-time markets must address persistent uncertainties and risks of overgeneration, where oversupply may lead to zero or negative LMPs. Strengthened transmission networks and innovative technologies like dynamic line ratings can alleviate constraints and optimize renewable integration. The evolving resource mix, replacing baseload FF plants with renewables, DER, storage, hydrogen, and flexible nuclear, necessitates upgraded scheduling, operational, and dispatch approaches. Granular pricing intervals, advanced ICT, smart metering, and control technologies enable markets to better align with system dynamics, balancing flexibility and revenue adequacy. These reforms, coupled with mechanisms to mitigate oversupply and incentivize ancillary services, are essential for integrating high shares of renewables across day-ahead and real-time markets.

- 2)

- Capacity Market: Decarbonization fundamentally reshapes capacity markets, necessitating adaptations to ensure grid reliability and resource adequacy amid increased reliance on VRE and DER. The low marginal costs and weather-dependent nature of VRE stress reserve margins threaten the financial sustainability of conventional power plants, with reduced hours of operation and, as such, leading to higher average energy costs, which require support that can come from capacity market revenues. These markets must integrate emerging resources like ES, DR, and DER while valuing their contributions to reliability. Shorter development timelines for renewables and batteries offer flexibility in capacity procurement but require alignment with the slower expansion of transmission infrastructure. As renewable sources with lower capacity factors replace baseload and FF plants, capacity markets must procure more nameplate capacity and embrace multi-year commitments with updated performance requirements to incentivize flexible and reliable resources. Enhanced forecasting and interregional transmission coordination will be essential for addressing grid bottlenecks and optimizing capacity procurement. Decarbonization’s dual impact—driving up capacity prices due to reduced reserve margins and downward energy price pressures from low-cost renewables—requires holistic market redesigns to ensure revenue adequacy for conventional and emerging technologies, securing grid stability in a low-carbon future.

- 3)

- Long-term Purchase Agreements: Decarbonization significantly reshapes LTPA, making them a part of the equation to secure financing for capital-intensive renewable projects while introducing new complexities. As VRE with zero marginal costs increases, LTPA provides revenue certainty but faces challenges like shorter contract terms due to rapid technological advancements and the risk of stranded assets. Hybrid structures combining RE with ES, hydrogen, or DERs might become more common to enhance flexibility and capacity commitments. Corporate renewable PPA may perhaps increase, expanding access to LTPA. However, evolving risks such as counterparty challenges from utilities with high-carbon assets and pricing pressures from declining clean technology costs necessitate more dynamic agreements, often with renegotiation clauses or price adjustments. Despite these shifts, LTPA remains critical for securing investment in a renewable-focused energy landscape.

- 4)

- Ancillary Services Market: Decarbonization fundamentally transforms ancillary services markets, increasing demand for services like operating reserves, frequency regulation, ramping, and reactive power to manage the variability and dispersion of RE. Faster response times and higher accuracy become critical, necessitating new ancillary services such as capacity synchronization, stability support, and congestion relief. Emerging resources like battery storage, advanced inverters, intelligent appliances, and electric vehicles are poised to play a significant role, requiring smarter grids and operations. Co-optimization of ancillary services and energy dispatch can leverage shared flexibilities, but market designs must evolve to introduce new products and compensation mechanisms for advanced technologies. Prices in ancillary services markets are likely to experience greater volatility, with potential spikes due to flexibility scarcity and the need for faster, more dynamic responses. Significant upgrades in ancillary services markets are essential to ensure system stability and reliability in a high-renewables grid.

- 5)

- Centralized Dispatch System: Decarbonization introduces significant complexity to centralized dispatch systems based on declared marginal costs, as the variability of VRE and DG challenges traditional supply-demand balancing. The predominance of low or zero-marginal-cost resources, coupled with overgeneration risks during periods of high renewable output and low demand, necessitates enhanced curtailment, load flexibility, and revenue mechanisms to ensure financial sustainability. Long-term planning becomes critical for capital-intensive projects like nuclear, pumped hydro, and transmission while managing security constraints and diverse generation profiles, such as DERs requiring advanced algorithms.23 Integrating advanced technologies and additional ancillary services through dynamic auctions will be essential to maintaining system stability. Declining marginal costs and clearing prices in merit-order dispatch systems could undermine conventional generators' revenues, raising the need for innovative capacity and ancillary service procurement strategies. Ultimately, while a centralized dispatch system could coordinate an efficient zero-carbon grid, success hinges on addressing flexibility needs, optimizing marginal costs, and leveraging competitive electricity generation to deliver transparent, dynamic price signals.

- 6)

- Transmission Markets: Decarbonization places unprecedented demands on transmission markets, highlighting their central role in integrating renewable energy and ensuring the energy transition's success. Utility-scale renewables, often sited far from demand centers, require robust and flexible transmission systems to deliver energy efficiently, reduce congestion, and prevent renewable curtailment. However, the rapid deployment of renewable generation outpaces the slower transmission infrastructure development, creating significant bottlenecks and curtailing clean energy's full potential. This disconnect undermines economic viability, exacerbates grid stability challenges, and necessitates sophisticated planning and investment. Modern grids must adapt to bidirectional power flows, integrate DER, and lose the natural inertia from traditional power plants, requiring advanced control systems and AS. Solutions such as grid-enhancing technologies, dynamic line ratings, strategically deployed energy storage, and innovative market mechanisms like financial transmission rights are helping optimize current infrastructure and incentivize investment. Addressing this challenge requires earlier and proactive transmission planning, updated regulatory frameworks for fair cost allocation, and enhanced coordination between transmission and distribution systems. Accelerating transmission development through technical, policy, and market reforms is essential to achieving a sustainable and decarbonized energy future.

- 7)

- Effects of Power Sector Decarbonization on Power Plant Revenues: Decarbonization fundamentally reshapes power plant revenues, creating challenges and opportunities depending on the resource type and market participation. VRE introduces increased market variability, with low or even negative prices during high output periods, reducing traditional FF plants’ revenues as their operating hours decline. Price volatility and regulatory costs, like carbon pricing, further pressure FF plants, which may need to shift from a baseload to a more flexible peaking role with less predictable but higher short-term earnings during low renewable output periods. Capacity markets and ancillary services offer new revenue streams for flexible resources like gas peakers, hydropower, and storage, rewarding their ability to stabilize the grid amidst renewable variability. Renewable plants benefit from LTPA and priority dispatch, but overgeneration risks and curtailment can undermine their earnings without sufficient storage or demand-side flexibility. As storage and DR technologies become cost-effective, competition in capacity and ancillary markets intensifies. Adapting to these dynamics by embracing flexibility, advanced technologies, and new market roles will be essential for sustaining power plant profitability in a decarbonized energy system.

- 8)

- Implications of Decarbonization on financial or derivatives markets and prices: Decarbonization significantly impacts financial and derivatives markets by increasing the demand for risk management tools to address heightened variability and uncertainty in energy output and prices. Integrating VRE introduces sharper price fluctuations, reflected in energy derivatives such as futures and options, which traders and investors use to hedge against market volatility. Capacity derivatives may adjust to shifts in reserve margins and the growing influence of weather-dependent resources. At the same time, AS markets could drive new financial instruments like options or swaps to manage risks tied to grid stability. Transmission congestion, a frequent challenge in renewable-heavy systems, heightens the relevance of instruments like CRRs and FTRs to hedge against localized price spikes. LTPA and its associated financial products could also evolve and be influenced by shifting technology costs and market structures. Additionally, derivatives tied to centralized dispatch systems may reflect the uncertainties of marginal costs and renewable integration efficiency. Decarbonization prompts the development of sophisticated financial tools to manage risks, ensure market stability, and capitalize on emerging opportunities in a transitioning energy landscape.

- 9)

- Emerging Technologies: The transformation of electricity markets necessitates a comprehensive approach integrating cutting-edge technologies and innovative market designs. Artificial intelligence and machine learning [129] can significantly enhance market forecasting and operational optimization, particularly for managing VRE uncertainties and DERs. Digital twin technologies offer crucial virtual simulation capabilities for testing grid scenarios, VRE integration strategies, and market responses.

5. Conclusion

- Market Dynamics and Flexibility: The variability and uncertainty introduced by VRE challenge traditional market structures, driving a shift toward markets that value flexibility. Resources capable of rapid response, such as energy storage and demand-side solutions, are becoming pivotal in maintaining system balance and reliability.

- Forecasting and Real-Time Operations: Accurate forecasting and responsive real-time operations are essential to bridge the gaps between day-ahead schedules and actual conditions. Improved forecasting techniques are critical to reducing costly system imbalances caused by discrepancies in renewable output.

- Generation Mix and Investment Patterns: A significant transition is evident, with traditional FF-based generation giving way to VRE, ES, and DER. Investment patterns are shifting towards grid modernization and technologies that enable VRE integration.

- Transmission and Overgeneration: Transmission constraints and overgeneration issues are highlighted as critical bottlenecks. Overgeneration leads to curtailment and wasted clean energy, undermining renewable project economics. The study stresses the importance of expanded transmission infrastructure, better integration of storage solutions, and refined renewables incentive schemes to address these challenges.

- Capacity and Ancillary Services Markets: Decarbonization redefines capacity markets, which should prioritize flexible resources like storage and DR over a model designed to favor traditional baseload generators. Ancillary services markets are evolving to address the challenges posed by high VRE penetration, such as frequency regulation, ramping, and voltage support.

- Economic Dynamics and Policy Focus: The transition to VRE has implications for investment costs, Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCOE), and system costs. Policymakers must incentivize clean energy adoption, encourage energy efficiency, and support the adoption and research into emerging technologies while addressing the system`s costs, the public good nature of energy security, and system flexibility.

- Financial Markets and Instruments: VRE variability underscores the importance of financial tools like LTPA, carbon pricing, and derivatives for managing risks and stabilizing revenues. These instruments and the adoption of new technologies, like Blockchain and Smart Contracts, will play a growing role in adapting to the evolving electricity market landscape.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Global greenhouse gas emissions can also be broken down by the economic activities that lead to their production: 25% is from electricity and heat production, 14% from transport, 6% from residential and commercial buildings, 21% from industry, 24% from agriculture, forestry, and other land use, and 10% from other energy uses. |

| 2 |

In the US the concept of Independent System Operators (ISOs) emerged in response to Orders Nos. 888/889, from 1996, where the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission proposed it as a means for addressing the need to provide non-discriminatory access to transmission within existing tightly integrated power pools. Following this, Order No. 2000, from 1999, encouraged the voluntary establishment of Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs) to oversee the transmission grid regionally across North America, encompassing Canada. Order No. 2000 outlined twelve specific characteristics and functions that an entity must fulfill to qualify as a RTO.

RTOs play a role similar to ISOs. Both ISOs and RTOs emerged in the US following the restructuring of traditionally vertically integrated utility companies. Their autonomy is crucial for ensuring reliable system coordination, efficient market operations, transparent planning, and impartial access to the grid, eliminating conflicts of interest.

Notable examples of ISOs/RTOs in North America include:

|

| 3 | Financial instrument or derivatives in the electric industry are contracts which derive their value from an underlying financial asset, commodity, index, market metric, or other measurable event like a weather or climate event. In the electricity sector, derivatives include forwards, futures, swaps, options, securities and insurance based on electricity prices. |

| 4 | The day-ahead market operates through a daily blind auction, where market participants submit locational orders to buy or sell electricity for each hour of the next day. This auction matches supply and demand to determine a locational market clearing price. The intraday market allows for continuous trading, enabling adjustments closer to the delivery time, enhancing flexibility. Both markets are integrated across European borders. Clearing houses ensure the fulfillment of transactions, mitigating counterparty risks and ensuring secure, reliable operations. |

| 5 |

Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) (2023). In the Australian electricity market, where generators submit locational offers indicating the price and quantity of electricity they are willing to produce over 5-minute intervals to the system operator, Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO). AEMO runs the security-constrained economic dispatch model every 5 minutes to determine which generators will be dispatched in merit order from lowest to highest offer price to meet forecast electricity demand over the next interval. The objective is to meet demand reliably at least cost. There are five regions corresponding to state boundaries, each with its own regional reference node for pricing purposes. For financial settlement purposes, the 5-minute dispatch prices are averaged to form a 30-minute spot price that all generation in each trading interval receives. While the 5-minute dispatch prices are location-specific, the 30-minute spot price used for financial settlement may be aggregated to a regional level. This centralized dispatch process relies on generator offers that reflect their short-run marginal costs of supplying the next increment of electricity to the grid. By coordinating generator dispatch decisions every 5 minutes based on their economic offers, AEMO aims to meet demand at high efficiency and low prices.

On September 2021, AEMC implemented the rule which transition the settlement interval for the electricity spot price from 30 minutes to five minutes. This adjustment was aimed to offer a more precise signal regarding the value of investments in fastresponse technologies, including batteries, emerging gas peaking plants, and demand response strategies.

|

| 6 | Generators submit bids and offers based on their short-run marginal costs into the Nord Pool day-ahead and intraday markets. Based on supply and demand fundamentals, Nord Pool calculates hourly market clearing prices for the following day. |

| 7 | In 2003 launched hourly and, half-hourly day-ahead and real-time markets, where the price of electricity in the wholesale electricity market changes every half-hour. |

| 8 | Over the past decades the provinces of Alberta and Ontario have undertaken varying degrees of deregulation within their electric industries. Although both provinces maintain electricity markets, notable distinctions exist between their respective systems. in Alberta, the competitive landscape is prevalent in the generation sector, while transmission and distribution operate under rate regulation. On the other hand, Ontario employs a hybrid model where the Ontario Power Authority, now consolidated with the IESO, manages functions such as contracting for supply, integrated system planning, and regulated pricing for a substantial portion of Ontario's generation and load. |

| 9 |

Seven Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs) operate wholesale electricity markets in the United States:

Of these, only ERCOT remains fully under state jurisdiction, as its footprint is contained within Texas. The other six RTOs fall under Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) oversight.

|

| 10 | In the US, currently, four out of the seven RTOs - MISO, PJM, NYISO, and ISO-NE - administer capacity markets through their footprint. These markets secure future resource adequacy commitments to meet peak demand forecasts. The other three RTOs (CAISO, SPP, ERCOT) fulfill capacity needs through alternative mechanisms and do not operate formal capacity market constructs. |

| 11 | Decreto Supremo No. 70 of 2023 (DS 70) from Ministerio de Energía [35], introduced relevant changes in the recognition and compensation of energy storage systems and hybrid plants with storage capacity. Among the most important modifications, a methodology was incorporated to evaluate and recognize the power capacity of stand-alone energy storage systems, and rules were established to determine payment for capacity specifically for renewable energy plants equipped with storage capacities, and the availability of data and studies was improved to more accurately identify the peak hours that determine the calculation and payment for capacity. |

| 12 |

Reliability Markets:

|

| 13 | The State of Hawaii Public Utilities Commission oversees four electric utility firms involved in generating, acquiring, transmitting, distributing, and selling electric energy within the State. Hawaii's six primary islands operate independent electrical grids without interconnection. Together, HECO, MECO, and HELCO are collectively referred to as the "HECO Companies" and cater to approximately 95% of the State's population. KIUC, situated on Kauai, serves the remaining 5%. Notably, the islands of Niihau and Kahoolawe lack electric utility services. |

| 14 | As of December 2023, the national electric system, Sistema Eléctrico Nacional (SEN), has an installed capacity of 33,831.6 MW. 62.7% of the installed capacity corresponds to renewable sources (21.9% hydraulic, 26.4% solar, 13.7% wind, 2.2% biomass, and 0.3% geothermal), while 35.1% corresponds to thermal sources (11.0% coal, 15.7% natural gas and 8.4% oil). |

| 15 | The Committee for Economic Operation of the System (Comité de Operación Económica del Sistema Interconectado Nacional, COES SINAC) is the ISO responsible for coordinating dispatch, managing transmission, and operating wholesale electricity markets. For the most part, Peru relies on marginal cost-based economic dispatch of generation resources to meet electricity demand efficiently. Generators submit information on availability, technical parameters, and short-run marginal costs to COES for the unit commitment and dispatch processes from one day ahead to real-time. Some spot energy and capacity and ancillary services markets provide revenue streams for generators based on marginal costs and auction clearing prices. |

| 16 | For example, as of May 2024, the Chilean electricity system SEN had a total of 1,008 electricity generating plants. Of these, 740 were defined as small distributed generation facilities (with a capacity of up to 9 MW), with an average installed capacity of 3.2 MW. And this is without counting micro installations behind the meters, such as solar PV rooftop installations, which in the case of Chile are still in their infancy. As a reference, in 2010 the power system had about 150 units. |

| 17 | Start-up Costs refer to the expenses incurred to bring a power plant from a non-operational state to an operational state; Shut-down Costs refer to the costs associated with ceasing the operation of a power plant and transitioning it to a non-operational state; and wear and tear costs refer to the costs related to the wear and tear of equipment during operation, often expressed as a cost per megawatt-hour of electricity generated. The wear and tear costs consider not only physical degradation but also operational expenses such as fuel consumption and maintenance due to frequent cycling. |

| 18 | Demand, Residual Demand, and Elasticities: Market demand can be expressed as P=a−bQ, where P is the price, Q is the total quantity, and a and b are constants. Residual demand, which flexible power units and BESS face, is the market demand minus the supply provided by VRE and other inflexible baseload generation. The elasticity of market demand is given by ϵm=−bP/Q, and the residual demand elasticity for flexible power units, BESS, and demand response (leaders) is ϵr=−bP/Qr, Qr is the flexible generators output, where Qr = Q – Qs, and Qs is output by unflexible generators. When residual demand becomes more inelastic (lower elasticity), as fewer units can provide flexibility, these units have greater market power because they can change prices without significantly reducing the quantity demanded. This situation arises when few competitors or alternatives are available to ISOs/RTOs, or the grid. |

| 19 | CAISO [96] experienced a reduction in energy demand in 2023, attributed to milder summer conditions as compared to previous years, and an increase in behind-the-meter (BTM) photovoltaic (PV) generation. This trend has continued from 2020, reflecting how decentralized solar generation and changing weather patterns are influencing overall energy consumption across the state. |

| 20 | Generators may bid at negative prices to avoid costly shutdown and restart cycles of their plants, effectively paying consumers to take excess electricity off the grid. This practice is particularly relevant for nuclear and coal-fired plants with high operational transition costs, as running at a temporary loss during low-demand periods is more economical than cycling the plant. Additionally, renewable generators may also face the incentive to continue producing during negative pricing periods when production tax credits and renewable certificates can offset these losses.. |

| 21 | On PJM Interconnection overcommitment see [99–105]. |

| 22 |

On December 1, 2023, the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit upheld PJM Interconnection, L.L.C.’s latest minimum offer price rule (Focused MOPR), rejecting challenges to both the substance of the rule and FERC’s approval. The Focused MOPR went into effect after the FERC Commissioners deadlocked and failed to issue a timely order. The Third Circuit stated that judicial review of FERC's action, whether actual or constructive, follows the same deferential standards under the Federal Power Act (FPA) and the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). The court found FERC's acceptance of the Focused MOPR was not arbitrary and capricious, as it was supported by substantial evidence, including arguments from then-Chairman Glick and Commissioner Clements.

The Focused MOPR mitigates buyer-side market power in two scenarios: when a capacity resource can exercise market power and when a resource receives state subsidies likely preempted by the FPA. It replaced the Expanded MOPR adopted in 2019 and took effect by law on September 29, 2021, after FERC failed to act on PJM's filing within the statutory deadline. Requests for rehearing were deemed denied by law on November 29, 2021, prompting several entities to seek appellate review.

On appeal, the court held that its review must follow the same standards as if FERC had issued an order. The court determined that the Joint Statement from FERC Commissioners supporting the Focused MOPR was reasoned and based on the record, addressing concerns about inflated prices, state policy changes, auction results, and states' potential abandonment of the capacity market. The court dismissed arguments that the Joint Statement ignored investors' reliance on existing PJM market mechanisms and confirmed that the Focused MOPR effectively balances the risks of over- and under-mitigation. The Third Circuit concluded that FERC's constructive acceptance of the Focused MOPR was neither arbitrary nor capricious and was backed by substantial evidence. See [106].

|

| 23 | Central Dispatch Systems are not exempt from controversy regarding declared marginal costs, particularly concerning the complex interplay between generators' fuel procurement strategies and their influence on both declared marginal and system marginal costs. A critical question emerges: Do natural gas combined cycle (NGCC) natural gas "take or pay" contracts inherently establish a must-run generation condition with a fuel opportunity cost of zero? See, for example, [128]. |

| 24 | A VPP represents a sophisticated networked ecosystem of DERs that extends far beyond traditional solar and battery storage. This innovative platform integrates an expanding array of technologies, including grid-interactive efficient appliances, smart buildings, electric vehicle charging infrastructure, and thermal energy storage systems. By leveraging sophisticated control mechanisms, aggregators, utilities, and grid operators can collaboratively and remotely modulate these distributed resources under mutually agreed contractual frameworks. The primary objectives encompass optimizing clean energy generation, enhancing grid reliability, and delivering essential grid services—all while preserving end-user comfort and operational productivity. Through an intricate integration of advanced software and hardware technologies, VPPs transcend conventional energy management paradigms by transforming diverse, decentralized energy assets into cohesive, dynamically responsive grid resources capable of providing utility-scale capabilities from behind-the-meter installations. |

References

- IPCC (2014). Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Edenhofer, O., R. Pichs-Madruga, Y. Sokona, E. Farahani, S. Kadner, K. Seyboth, A. Adler, I. Baum, S. Brunner, P. Eickemeier, B. Kriemann, J. Savolainen, S. Schlömer, C. von Stechow, T. Zwickel and J.C. Minx (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. EPA (2023). https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-data#:~:text=Carbon%20dioxide%20(CO2)%3A,agriculture%2C%20and%20degradation%20of%20soils (Accessed 12/12/2023).

- EPRI (2021). “US-REGEN Documentation.” https://us-regen-docs.epri.com/v2021a/assumptions/electricity-generation.html#existing-fleet (Accessed 11/15/2023).

- FERC (2023). “RTOs and ISOs,” https://www.ferc.gov/power-sales-and-markets/rtos-and-isos (Accessed 11/29/2023).

- FERC (1996). “Order No. 888.” https://www.ferc.gov/industries-data/electric/industry-activities/open-access-transmission-tariff-oatt-reform/history-oatt-reform/order-no-888 (Accessed 11/29/2023).

- FERC (1996). “Order No. 889.” https://www.ferc.gov/industries-data/electric/industry-activities/open-access-transmission-tariff-oatt-reform/history-of-oatt-reform/order-no-889-1 (Accessed 11/29/2023).

- FERC (1999). “Order No. 2000.” chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.ferc.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/RM99-2-00K_1.pdf (Accessed 11/29/2023).

- Intercontinental Exchange, Inc. operates global financial exchanges for electricity markets, North American & European Power Futures. See [6] ICE https://www.ice.com/energy/power (Accessed 12/12/2023).

- Denga, S.J.; and Oren, S.S. (2006). “Electricity derivatives and risk management,” Energy Vol 31, pp. 940–953. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://oren.ieor.berkeley.edu/pubs/Deng%20and%20Oren-86.pdf (Accessed 12/12/2023).

- World Federation of Exchanges (2022). “WFE Derivatives Report 2021,” April 2022. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.world-exchanges.org/storage/app/media/2021%20Annual%20Derivatives%20Report.pdf (Accessed 1/30/2024).

- Bublitz, A.; Keles, D.; Fichtner, W. (2017). An analysis of the decline of electricity spot prices in Europe: Who is to blame? Energy Policy, 107, 323-336. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301421517302598 (Accessed September 14, 2023).

- Raineri, R.; Rios, S.; Schiele, D., 2006. "Technical and economic aspects of ancillary services markets in the electric power industry: an international comparison," Energy Policy, Elsevier, vol. 34(13), pages 1540-1555, September.

- PJM Markets and Operations (2023). “PJM Markets and Operations.” https://www.pjm.com/markets-and-operations (Accessed 11/27/2023).

- PJM`s Energy Markets (2023). “PJM`s Energy Markets.” https://learn.pjm.com/three-priorities/buying-and-selling-energy/energy-markets (Accessed 12/11/2023).

- ISO New England Markets and Operations (2023). https://www.iso-ne.com/markets-operations (accessed 11/27/2023).

- California ISO Markets and Operations (2023). https://www.caiso.com/market/Pages/default.aspx (Accessed 11/27/2023).

- New York ISO Markets (2023). https://www.nyiso.com/markets (Accessed 11/27/2023).

- ERCOT Market Information (2023). https://www.ercot.com/mktinfo (Accessed 11/27/2023).

- EPEXSpot (2014). “Basics of the Power Market,” https://www.epexspot.com/en/basicspowermarket (Accessed June 10, 2024).

- ENTSO-E Market (2023). https://www.entsoe.eu/ (Accessed 11/27/2023); EPEX SPOT Market (2023). https://www.epexspot.com/ (Accessed 11/27/2023); Nord Pool Markets (2023). https://www.nordpoolgroup.com/ (Accessed 11/27/2023).

- Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) (2023). https://www.aemc.gov.au/energy-system/electricity/electricity-market/how-power-dispatched-across-system#:~:text=AEMO's%20central%20dispatch%20engine%20orders,generators%20to%20meet%20expected%20demand. (Accessed 11/20/2023).

- Australian Energy Market Operator -AEMO- (2023). https://aemo.com.au/ (Accessed 11/27/2023). https://www.aemc.gov.au/energy-system/electricity/electricity-market/spot-and-contract-markets.

- Energy Facts Norway (2023). https://energifaktanorge.no/en/norsk-energiforsyning/kraftmarkedet/ (Accessed 11/21/2023).

- Energy Market Authority of Singapore (2023). https://www.ema.gov.sg/our-energy-story/energy-market-landscape/electricity (Acceded 11/17/2023).

- Independent Electricity System Operator (IESO) (2023). Markets and Related Programs https://www.ieso.ca/ (Accessed 10/15/2024).

- Alberta Electric System Operator (AESO) (2023). Guide to understanding Alberta’s electricity market https://www.aeso.ca/aeso/understanding-electricity-in-alberta/continuing-education/guide-to-understanding-albertas-electricity-market/ (Accessed 10/15/2024).

- Canada Energy Regulator -CER- (2024). “Provincial and Territorial Energy Profiles – Canada,” https://www.cer-rec.gc.ca/en/data-analysis/energy-markets/provincial-territorial-energy-profiles/provincial-territorial-energy-profiles-canada.html (Accessed 10/15/2024).

- Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (2015). “Chronology of New Zealand Electricity Reform,” Energy Markets Policy, Energy & Resources Branch of Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, August 2015, https://www.mbie.govt.nz/assets/2ba6419674/chronology-of-nz-electricity-reform.pdf (Accessed 12/11/2023).

- Transpower (2023). https://www.transpower.co.nz/ (Accessed 11/20/2023).

- FERC (2023). “Electric Power Markets.” https://www.ferc.gov/electric-power-markets (Accessed 11/27/2023).

- American Public Power Association (2023). “Wholesale Electricity Markets and Regional Transmission Organizations,” Electricity Markets Issue Brief. https://www.publicpower.org/policy/wholesale-electricity-markets-and-regional-transmission-organizations-0 (Accessed 11/30/2023).

- PJM (2023). “Capacity Market (RPM),” https://www.pjm.com/markets-and-operations/rpm#:~:text=PJM's%20capacity%20market%2C%20called%20the,energy%20demand%20in%20the%20future. (Accessed 11/29/2023).

- PJM (2023). “PJM Manual 18: PJM Capacity Market, Revision: 58,” Effective Date: November 15, 2023. Prepared By Capacity Market & Demand Response Operations. https://www.pjm.com/~/media/documents/manuals/m18.ashx (Accessed 12/4/2023).

- Hancher, L.; de Hauteclocque, A.; Huhta, K.; Malgorzata, S. (Editors) (2022). "Capacity mechanisms in the EU energy markets: law, policy, and economics," Energy Union Law, Book edited by Leigh Hancher, Adrien de Hauteclocque, Kaisa Huhta, Sadowska Malgorzata. https://fsr.eui.eu/publications/?handle=1814/75007 (Accessed 10/15/2024).

- Raineri, R. (2006). “Chile: Where it all started,” chapter 3 in the Book Electricity Market Reform: An International Perspective, Fereidoon P. Sioshansi and Wolfgang Pfaffenberger editors. Chapter 3, pg. 77-108. Series: Global Energy Policy and Economics, Elsevier 2006.

- Ministerio de Energía Chile (2023). “Decreto Supremo No. 70 de 2023 (DS 70).”.

- Cramton, P.; & Stoft, S. (2005). A Capacity Market that Makes Sense. The Electricity Journal, 18(7), 43-54. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1040619005000850 (Accessed September 12, 2023).

- Joskow, P. L. (2008). Capacity payments in imperfect electricity markets: Need and design. Utilities Policy, 16(3), 159-170. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0957178707000926 (Accessed September 12, 2023).

- Newbery, D. (2016). Missing money and missing markets: Reliability, capacity auctions and interconnectors. Energy Policy, 94, 401-410. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301421515301555 (Accessed September 14, 2023).

- Hogan, W. W. (2005). On an "Energy Only" Electricity Market Design for Resource Adequacy. Center for Business and Government, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, September 23, 2005. https://scholar.harvard.edu/whogan/files/hogan_energy_only_092305.pdf (Accessed September 22, 2023).

- Bushnell, J.; Flagg, M.; Mansur, E. (2017). Capacity Markets at a Crossroads. Energy Institute at Haas Working Paper 278, April 2017. https://www.haas.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/WP278Updated.pdf (Accessed September 22, 2023).

- Hogan, W. W. (2013). Electricity Scarcity Pricing Through Operating Reserves. Economics of Energy & Environmental Policy, 2(2), 65-86. https://www.pserc.cornell.edu/empire/2_2_a04.pdf (Accessed September 22, 2023).

- Levin, T.; & Botterud, A. (2015). Electricity market design for generator revenue sufficiency with increased variable generation. Energy Policy, 87, 392-406. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301421515300999 (Accessed September 24, 2023).

- Grubb, M.; Newbery, D. (2018). UK Electricity Market Reform and the Energy Transition: Emerging Lessons. The Energy Journal, 39(6), pp. 1-26. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26606242 (Accessed September 24, 2023).

- Simshauser, P. (2018). On intermittent renewable generation & the stability of Australia's National Electricity Market. Energy Economics, 72, 1-19. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0140988318300562 (Accessed September 24, 2023).

- de Vries, L.; Heijnen, P. (2008). The impact of electricity market design upon investment under uncertainty: The effectiveness of capacity mechanisms. Utilities Policy, 16(3), 215-227. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0957178708000027 (Accessed September 26, 2023).

- Bajo-Buenestado, R. (2017). Welfare implications of capacity payments in a price-capped electricity sector: A case study of the Texas market (ERCOT). Energy Economics, 64, 272-285. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0140988317301032 (Accessed September 26, 2023).

- Schwenen, S. (2014). Market design and supply security in imperfect power markets. Energy Economics, V. 43, May 2014, Pages 256-263. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0140988314000395 (Accessed September 26, 2023).

- Brown, D. P. (2018). Capacity payment mechanisms and investment incentives in restructured electricity markets. Energy Economics, 74, 131-142. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0140988318302068 (Accessed September 28, 2023).

- Bhagwat, P. C.; Iychettira, K. K.; Richstein, J. C.; Chappin, E. J.; De Vries, L. J. (2017). The effectiveness of capacity markets in the presence of a high portfolio share of renewable energy sources. Utilities Policy, 48, 76-91. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0957178716300406#:~:text=A%20decline%20or%20no%20growth,14 (Accessed September 28, 2023).

- Commission de Regulation de L`Energie (2023). “Wholesale electricity market.” https://www.cre.fr/en/Electricity/Wholesale-electricity-market/wholesale-electricity-market (Accessed 11/21/2023).

- Guénaire, M.; Dufour, T.; George, E.; Assayag, S.; Nouel, G.L. (2020). “Electricity regulation in France: overview,” in Practical Law, Thomson Reuters. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.gide.com/sites/default/files/electricity_regulation_in_france_overview_7-629-75671.pdf (Accessed 11/21/2023).

- des Comptes,C. (2022). “Organization oe the electricity markets,” Rapport public thématique, public policy evaluation, July 2022. https://www.ccomptes.fr/system/files/2022-10/20220705-Organisation-electricity-markets-summary.pdf (Accessed 11/27/2023).

- FERC (2023). “Electric Power Markets.” https://www.ferc.gov/electric-power-markets.

- Southface Institute, Vote Solar (2018). “Understanding the Electricity System in Georgia”, Draft prepared by Southface Institute and Vote Solar, May 2018. https://www.southface.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Georgia-Electricity-System-Primer-May-2018-Draft.pdf (Accessed 11/27/2023).

- WRAL NEWS (2023). “Big electricity users push for competition in NC energy market.” NC State Capitol Bureau, State Capitol news. https://www.wral.com/story/big-electricity-users-push-for-competition-in-nc-energy-market/20943043/ (Accessed 11/28/2023).

- Tennesse Valley Authority (2023). https://www.tva.com/ (Accessed 27/11/2023).

- FERC (2023). “Electric Power Markets.” https://www.ferc.gov/electric-power-markets.

- State of Hawaii, Public Utilities Commission (2023). [55] “Electric Utilities,” https://puc.hawaii.gov/energy/ (Accessed 11/29/2023).

- Hawaiian Electric (2023). https://www.hawaiianelectric.com/ (Accessed 11/29/2023).

- Alaska Energy Authority (2023). https://www.akenergyauthority.org/ (Accessed 29/11/2023).

- Alaska Power Association (2023). https://alaskapower.org/ (Accessed 11/29/2023).

- FERC (2023). “Electric Power Markets.” https://www.ferc.gov/electric-power-markets (Accessed 11/27/2023).

- Coordinador Eléctrico Nacional -CEN- (2023). https://www.coordinador.cl/ (Accessed 11/29/2023);

- Becker, E. (2020). “Análisis del Mercado Eléctrico Argentino: Impacto de la regulación en su funcionamiento,” Departamento de Economía- Universidad Nacional del Sur Trabajo de grado de la Licenciatura en Economía. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://repositoriodigital.uns.edu.ar/bitstream/handle/123456789/5378/Becker%2C%20Eleonora_%20Tesis%20de%20Grado%202020.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (Accessed 11/21/2023).

- Comité de Operación Económica del Sistema Interconectado Nacional COES SINAC (2023). https://www.coes.org.pe/portal/ (Accessed 11/29/2023).

- Yongping, Z.; Feng, Z.; Linan, P.; Yang, Y. (2023). “The current state of China’s electricity market,” China Dialogue, September 1, 2023. https://chinadialogue.net/en/energy/the-current-state-of-chinas-electricity-market/ (Accessed 11/29/2023).

- Hove, A. (2023). “China’s new capacity payment risks locking in coal,” China Dialogue, November 23, 2023. https://chinadialogue.net/en/energy/chinas-new-capacity-payment-risks-locking-in-coal/ (Accessed 11/29/2023).

- Federal Energy Reulatory Commissionn (2006). “Order No. 888: Promoting Wholesale Competition Through Open Access Non-discriminatory Transmission Services by Public Utilities; Recovery of Stranded Costs by Public Utilities and Transmitting Utilities” https://www.ferc.gov/industries-data/electric/industry-activities/open-access-transmission-tariff-oatt-reform/history-oatt-reform/order-no-888 (Accessed 18/10/2024).

- European Union (2009). “Regulation (EC) No 714/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 on conditions for access to the network for cross-border exchanges in electricity and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1228/2003,” (Text with EEA relevance). http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2009/714/oj (Accessed 10/18/2024).

- Araneda, J.C. (2021). “El Sistema Eléctrico Chileno,”Coordinador Eléctrico Nacional, Encuentro virtual de la Región Iberoamericana de CIGRE (e-RIAC) “Desafíos de la operación en la Región Iberoamericana. Una mirada postpandémica". chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.cigre.cl/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Sistema-Electrico_CHILE__e_RIAC_2021.pdf (Accessed 10/18/2024).

- Energy Networks Australia (2021). “Guide to Australia's Energy Networks,” www.energynetworks.com.au/assets/uploads/Guide-to-Australias-Energy-Networks_2021-1.pdf (Accessed 10/18/2024).

- Coordinador Eléctrico Nacional (2024). “Coordinador Eléctrico impulsa licitación de obras de ampliación del sistema de transmisión por más de US$ 34,5 millones,” November 13, 2024. https://www.coordinador.cl/novedades/coordinador-electrico-impulsa-licitacion-de-obras-de-ampliacion-del-sistema-de-transmision-por-mas-de-us-345-millones/ (Accessed 10/18/2024).

- Agência Nacional de Energia Elétrica (ANEEL) (2024). “Transmissão,” https://www.gov.br/aneel/pt-br/assuntos/transmissao (Accessed 10/18/2024).

- Centro Nacional de Control de Energía (CENACE) (2024) . “Quiénes Somos,” https://www.cenace.gob.mx/CENACE.aspx (Accessed 10/18/2024).

- NEA (2019). “The Costs of Decarbonisation: System Costs with High Shares of Nuclear and Renewables,” OECD Publishing, Paris. https://www.oecd-nea.org/jcms/pl_15000/the-costs-of-decarbonisation-system-costs-with-high-shares-of-nuclear-and-renewables?details=true (Accessed November 27, 2024).

- Ethan Howland E. (2023). “PJM it will remain profitable to sell PJM capacity that you can’t deliver,” Utility Dive, Published Sept. 28, 2023. https://www.utilitydive.com/news/pjm-interconnection-board-capacity-market-proposal-ferc-reliability/695037/ (Accessed November 25, 2024).

- Energy Information Administration (2023). “Levelized Costs of New Generation Resources in the Annual Energy Outlook 2023,” https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/electricity_generation/pdf/AEO2023_LCOE_report.pdf#:~:text=URL%3A%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.eia.gov%2Foutlooks%2Faeo%2Felectricity_generation%2Fpdf%2FAEO2023_LCOE_report.pdf%0AVisible%3A%200%25%20 (Accessed 11/30/2023).

- NREL (2012), “Power Plant Cycling Costs,” conducted by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy12osti/55433.pdf (Accessed November 29, 2024).

- Savin, O.S.; & Badina, C.; Baroth, J.; Charbonnier, S.; Berenguer, C. (2020). Start and Stop Costs for Hydro Power Plants: A Critical Literature Review. Proceedings of the 29th European Safety and Reliability Conference (ESREL) 342-349. 10.3850/978-981-14-8593-0_4102-cd. [CrossRef]

- Van den Bergh, K.; Delarue, E. (2015). Cycling of conventional power plants: Technical limits and actual costs. Energy Conversion and Management, 97, 70-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2015.03.026 (Accessed Noveember 10, 2024). [CrossRef]

- Schill, W.P.; Pahle, M.; Gambardella, C. (2016). “On Start-up Costs of Thermal Power Plants in Markets with Increasing Shares of Fluctuating Renewables,” Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung, Berlin. https://d-nb.info/115301274X/34 (Accessed Noveember 10, 2024).

- Xu, T; Birchfield, A.B.; Gegner, K.M.; Shetye, K.S.; Overbye, T.J. (2017). “Application of Large-Scale Synthetic Power System Models for Energy,” Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. Pg 3123-3129. URI: http://hdl.handle.net/10125/41535 (Accessed November 20, 2023).

- Coordinado Eléctrico Nacional (2022), “Resumen Ejecutivo Estudio de Desgaste de SSCC.” https://www.coordinador.cl/mercados/documentos/servicios-complementarios/estudio-de-costos-de-desagste-sscc/2022-estudio-de-costos-de-desagste-sscc/ (Accessed November 18, 2023).

- Coordinado Eléctrico Nacional (2024), “Estudio de costos de los servicios complementarios sistema eléctrico nacional 2024-2027.” https://www.coordinador.cl/mercados/documentos/servicios-complementarios/estudio-de-costos-de-sscc/estudio-de-costos-sscc-2024/ (Accessed November 20, 2024).

- EIA (2020). “About 25% of US power plants can start up within an hour.” https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=45956 (Accessed November 20, 2024).

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). (2018). "Operational Analysis of the Eastern Interconnection at Very High Renewable Penetrations;".

- US Energy Information Administration (EIA) (2019). "Annual Energy Outlook 2019 with projections to 2050.".

- Huang, C.; Han, D.; Yan, Z.; Li, Y.; Sun, C.; Jia,Q. (2022). “Bidding strategy of energy storage in imperfectly competitive flexible ramping market via system dynamics method,” International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, Volume 136, 107722, ISSN 0142-0615, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2021.107722. [CrossRef]

- Ela, E.G.; O'Malley, M. (2015). “Scheduling and Pricing for Expected Ramp Capability in Real-Time Power Markets,” August 2015, Power Systems, IEEE Transactions on 31(3):1-11. DOI: 10.1109/TPWRS.2015.2461535. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, S. (2020). “System Market Power: HASP Based Mitigation Design Discussion,”Member, California ISO Market Surveillance Committee, Western Imbalance market, July 30, 2020. https://www.caiso.com/documents/systemmarketpowermitigationdiscussion-harvey-presentation-july30_2020.pdf (Accessed October 20, 2024).

- IEA (2019). “Status of Power System Transformation 2019 Power system flexibility,” May 2019. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/00dd2818-65f1-426c-8756-9cc0409d89a8/Status_of_Power_System_Transformation_2019.pdf (Accessed September 27, 2024).

- Wiser, R.; Mills, A.; Seel, J.; Levin, T.; Botterud, A. (2017). "Impacts of Variable Renewable Energy on Bulk Power System Assets, Pricing, and Costs." Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). (2020). "State of the Markets Report 2019." Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, March 19, 2020), https://www.ferc.gov/sites/default/files/2020-04/2019StateoftheMarketsReport.pdf.

- Barbose, G. (2024). "US States Renewables Portfolio & Clean Electricity Standards: 2024 Status Update." Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. https://emp.lbl.gov/publications/us-state-renewables-portfolio-clean-0 (Accessed September 15, 2024).

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (2024). “2023 State of the Markets,” Office of Energy Policy and Innovation, March 21, 2024, Staff Report.

- California ISO (2024). “Department of Market Monitoring: 2023 Annual Report on Market Issues & Performance,” July 29, 2024.

- Neeley, J. (2021). “Understanding Negative Prices in the Texas Electricity Market”, R Street Institute, 2021. Available online at: https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/understanding-negative-prices-in-the-texas-electricity-market/.

- CAISO (2024). “Annual Report on Market Issues and Performance,” Department of Market Monitoring, CA ISO July 29, 2024.

- Monitoring Analytics, LLC (2018). “State of the Market Report for PJM 2017,” Independent Market Monitor for PJM, 8 March 2018.

- Levin, T.; Botterud, A. (2015). “Electricity market design for generator revenue sufficiency with increased variable generation,” Energy Policy, 2015, vol. 87, issue C, pg. 392-406.

- Wilson, J. (2021). “Over-Procurement of Generating Capacity in PJM: Causes and Consequences,” Wilson Energyy Economics, report Prepared For Sierra Club Natural Resources Defense Council. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://wilsonenec.com/dev/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Wilson-Overprocurement-of-Capacity-in-PJM.pdf (Accessed October 7, 2024);

- Hogan, W. (2022). Electricity Market Design and Zero-Marginal Cost Generation. Current Sustainable/Renewable Energy Reports. 9. 1-12. 10.1007/s40518-021-00200-9. [CrossRef]

- Hogan, M. (2017). “Follow the missing money: Ensuring reliability at least cost to consumers in the transition to a low-carbon power system,” The Electricity Journal, Volume 30, Issue 1, January–February 2017, Pages 55-61. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1040619016302512#sec0035 (Accessed October 7, 2024);

- Milstein, I.; Tishler, A. (2019). “On the effects of capacity payments in competitive electricity markets: Capacity adequacy, price cap, and reliability,”. Energy Policy, June 2019, pg. 370-385. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301421519301119 (Accessed October 7, 2024);

- Lavin, L.; Murphy, S.; Sergi, B.; Apt, J. (2020). "Dynamic operating reserve procurement improves scarcity pricing in PJM," Energy Policy, Volume 147, 111857. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301421520305747 (Accessed October 7, 2024).

- Shrestha, S.; O'Konski, K. (2023). “Third Circuit Upholds FERC’s Approval of PJM’s Focused MOPR,” Troutman Pepper, Posted in Market Policy, December 11, 2023. https://www.troutmanenergyreport.com/2023/12/third-circuit-upholds-fercs-approval-of-pjms-focused-mopr/ (Accessed February 24, 2024).

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (2024). “2023 State of the Markets,” Office of Energy Policy and Innovation, March 21, 2024, Staff Report.

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (2024). “2023 State of the Markets,” Office of Energy Policy.

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (2024). Innovation, March 21, 2024, Staff Report.

- US Department of Energy (2023). “National Transmission Needs Study,” October 2023.

- Jowett, P. (2024). “Negative electricity prices registered in nearly all European energy markets,” PV Magazine, 10 April 2024. https://www.pv-magazine.com/2024/04/10/negative-electricity-prices-registered-in-nearly-all-european-energy-markets/ (Accessed June 14, 2024).

- European Commission. (2024, March 22). “Report on energy prices and costs in Europe,” March 22, 2024 (COM(2024) 136 final). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52024DC0136 (Accessed Octyobeer 10, 2024); and.

- AleaSoft Energy Forecasting (2024). “European electricity markets react to increased wind energy production with price declines,” June 17. https://aleasoft.com/decreases-european-market-prices-increase-wind-energy/ (Accessed October 7, 2024).

- Horsch, A.; Aust, B. (2020). “Negative market prices on power exchanges: Evidence and policy implications from Germany.” The Electricity Journal, Volume 33, Issue 3, April 2020, 106716, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1040619020300087 (Accessed October 10, 2024).

- Council of European Energy Regulators (CEER) (2023). "Status Review of Renewable Support Schemes in Europe for 2020 and 2021," Council of European Energy Regulators (CEER) Report, Renewables Work Stream of Electricity Working Group Ref: C22-RES-80-04 28 September 2023. https://www.ceer.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/RES_Status_Review_in_Europe_for_2020-2021.pdf (Accessed October 10, 2024).

- De Vos, K. (2015). "Negative Wholesale Electricity Prices in the German, French and Belgian Day-Ahead, Intra-Day and Real-Time Markets," The Electricity Journal, Volume 28, Issue 4, May 2015, Pages 36-50. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1040619015000652#:~:text=Pages%2036%2D50-,Negative%20Wholesale%20Electricity%20Prices%20in%20the%20German%2C%20French%20and%20Belgian,Day%20and%20Real%2DTime%20Markets&text=Negative%20prices%20are%20a%20correct,caused%20by%20renewable%20support%20mechanisms. (Accessed October 10, 2024).

- International Energy Agency (IEA) (2024). “Woorld Energy Outlook Special Report: Batteries and Secure Energy Transitions.” https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/cb39c1bf-d2b3-446d-8c35-aae6b1f3a4a0/BatteriesandSecureEnergyTransitions.pdf (Accessed October, 2024).

- Joos, M.; Staffell, I. (2018). "'Short-term integration costs of variable renewable energy: Wind curtailment and balancing in Britain and Germany," Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Volume 86, April 2018, Pages 45-65. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364032118300091 (Accessed October 3, 2024).

- Nicolosi, M. (2010). Wind power integration and power system flexibility–An empirical analysis of extreme events in Germany under the new negative price regime. Energy Policy, 38(11), 7257-7268. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301421510005860 (Accessed September 28, 2023).

- European Commission (2024). “Quarterly report On European electricity markets with focus on annual overview for 2023,” Market Observatory for Energy, DG Energy Volume 16 (issue 4, covering fourth quarter of 2023).

- Evol Services (2024), “Pérdidas De Energía Aumentan Y Alcanzan Más Del 18% De Producción Eólica Y Solar Del País En El Primer Trimestre.” https://services.evol.energy/2024/04/15/perdidas-de-energia-aumentan-y-alcanzan-mas-del-18-de-produccion-eolica-y-solar-del-pais-en-el-primer-trimestre/ (Accessed 25 July 2024).

- IEA (2019). “Status of Power System Transformation 2019 Power system flexibility,” May 2019. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/00dd2818-65f1-426c-8756-9cc0409d89a8/Status_of_Power_System_Transformation_2019.pdf (Accessed September 27, 2024).

- Csereklyei, Z. (2020). “Price and income elasticities of residential and industrial electricity demand in the European Union,” Energy Policy, Volume 137, Page 111079, February 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111079 (Accessed January 1st, 2024). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, L. (2017). “Improving economic values of day-ahead load forecasts to real-time power system operations,” IET Generation, Transmission and Distribution, pg. 4238-4247, 06 September 2017. https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-gtd.2017.0517 (Accessed February 22, 2024). [CrossRef]

- Monitoring Analytics, LLC (2024). “2023 Annual State of the Market Report for PJM.” www.monitoringanalytics.com/reports/PJM_State_of_the_Market/2023/2023-som-pjm-vol2.pdf (Accessed June 6, 2024).

- Coordinador Electrico Nacional (2024). “Operational Data for 2022 and 2023 from Coordinador Electrico Nacional, Desviación de la Demanda Programada,” https://www.coordinador.cl/ Data retrieved on June 1st, 2024.

- Adhikari, U. (2019). “Solving Price Volatility in Renewable Energy Wholesale Markets Renewable Energy Procurement,” The Sol Source, Third Quarter 2019, 05 Nov 2019, pg. 6-9. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.solsystems.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Sol_SOURCE_Q3.pdf (Accessed June 15, 2024).

- García Bernal, N. (2021). "Condición de inflexibilidad del GNL en el Sistema Eléctrico Nacional,” Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile, Asesoría Técnica Parlamentaria, June 2021. https://obtienearchivo.bcn.cl/obtienearchivo?id=repositorio/10221/32301/1/BCN___Condicion_de_inflexibilidad_del_GNL.pdf (Accessed 12/19/2023).

- Gaamouche, R.; Chinnici, M.; Lahby, M.; Abakarim, Y.; Hasnaoui, A. (2022). Machine Learning Techniques for Renewable Energy Forecasting: A Comprehensive Review. In: Lahby, M., Al-Fuqaha, A., Maleh, Y. (eds) Computational Intelligence Techniques for Green Smart Cities. Green Energy and Technology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96429-0_1 (Accessed November 3, 2024). [CrossRef]

- Vionis, P.; Kotsilieris, T. (2024). “The Potential of Blockchain Technology and Smart Contracts in the Energy Sector: A Review.” Applied Sciences, 14(1), 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14010253. [CrossRef]

- US Department of Energy (). “Virtual Power Plants.” https://www.energy.gov/lpo/virtual-power-plants (Accessed November 10, 2024).

- Fournely, C.; Pečjak, M.; Smolej, T.; Türk, A.; Neumann, C. (2022). "Flexibility markets in the EU: Emerging approaches and new options for market design," 18th International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM), Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2022, pp. 1-7, doi: 10.1109/EEM54602.2022.9921138. https://xflexproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/9_Flexibility-markets-in-the-EU-Emerging-approaches-and-new-options-for-market-design.pdf (Accessed December 9, 2024). [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2020). "Clean Energy for All Europeans Package". Official Publications. https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-strategy/clean-energy-all-europeans-package_en#electricity-market-design (Accessed December 9, 2024).

- Australian Renewable Energy Agency -ARENA- (2017). “Virtual power plant in South Australia Stage 1 milestone report,” July 31st, 2017. https://arena.gov.au/assets/2017/02/VPP-SA-Public-Milestone-1-Report-Final-for-issue.pdf (Accessed December 9, 2024).

- Australian Renewable Energy Agency -ARENA- (2018). “Virtual power plant in South Australia Stage 2 public report,” June 15, 2018. (Accessed December 9, 2024). https://arena.gov.au/assets/2017/02/virtual-power-plants-in-south-australia-stage-2-public-report.pdf (Accessed December 9, 2024).

- TEPCO (2018). “TEPCO looks to the transformative potential of blockchain by investing in Electron, a UK energy technology company,” Announcement Jan 19, 2018. https://www.tepco.co.jp/en/announcements/2018/1473674_15434.html (Accessed December 3, 2024).

- Losanova, S. (2024). “What is a Virtual Power Plant (VPP)?” Greenlancer. https://www.greenlancer.com/post/virtual-power-plants-vpps (Accessed December 3, 2024).

- EPRI (2024). “Vermont Green P2P Trading,” EPRI Tech Portal. https://techportal.epri.com/demonstrations/demo/ubig/7FzJj6XWufc3QP08AqlfzC (Accessed December 3, 2024).

- Energy Web (2024). “About Energy Web,” https://www.energyweb.org/about (Accessed December 3, 2024).

- Kraken (2022). “What is Energy Web Token? (EWT),” Kraken Learn team, Jan 19, 2022. https://www.kraken.com/learn/what-is-energy-web-token-ewt (Accessed December 3, 2024).

- Energy Web (2020. “LO3 Energy Updates Pando Platform, Migrates To Energy Web Chain,” Medium.com Sep 24, 2020. https://medium.com/energy-web-insights/lo3-energy-updates-pando-platform-migrates-to-energy-web-chain-d709ae0e5311 (Accessed December 3, 2024).

- European Commission (2023). “Electricity market design,” Energy, Climate change, Environment. https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/markets-and-consumers/electricity-market-design_en?utm_source=chatgpt.com (Accessed November 7, 2024).

| Fuel Type | Ramp Rate (% of rated capacity per min)* | Start-up Costs (USD/ MW/ start)* | Shut-down Costs (USD/ MW/ shutdown)* | Start-up Time (hours)* | Shut-down Time (hours)* | Minimum On Time (hours)* | Minimum Off Time (hours)* | Cost of Wear and Tear (USD/MWh-h) For Primary and secondary frequency control ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coal | 0.6-8 | 100-250 | 10-25 | 4-9 | 2-9 | 0-12 | 0-12 | 1.087-1.760 |

| Natural Gas | 0.8-30 | 20-150 | 2-15 | 2-4 | 1-4 | 0-2 | 0-1 | 1.243-1.824 |

| Nuclear | 0-5 | 1000 | 1000 | 24 | 24 | Days | Days | 0.029 |

| Hydro | 15-25 | 0-5 | 0-0.5 | 0-1 | 0-1 | 0-1 | 0-1 | 2.722-4.714 Dum;0.029 Run of River |

| Wind | Non-dispatchable | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.006-0.070 |

| Solar | Non-dispatchable | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.006-0.235 PV 0.017 CSP |

| Battery Storage | 0-100 | Varies | Varies | < 0.25 | < 0.25 | < 1 | < 1 | 0.042 (PV+BEES) |

| Diesel | 2-5 | 5-20 | 1-5 | 0.25-0.5 | 0.17-0.33 | 1-2 | 1-2 | 0.043 |

| Source: *[82]; ** [83,84,85]. | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).