Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Performance and Key Properties

2. Applications of GPEs in Energy Storage Devices

2.1. Lithium-Ion Batteries:

2.2. Sodium-Ion Batteries:

2.3. Zinc-Batteries:

2.4. Supercapacitors

3.0. Case studies on GPEs

3.1. Dendrites Control

3.2. Wide Electrochemical Stability Window

3.3. Enhanced Interfacial Stability

4.0. A Note on Transference Number

5.0. Conclusions and Future Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goodenough, J.B.; Park, K.-S. The Li-Ion Rechargeable Battery: A Perspective. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthiram, A. A reflection on lithium-ion battery cathode chemistry. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.N.; Kim, M.-H.; Meena, A.; Wi, T.-U.; Lee, H.-W.; Kim, K.S. Na/Al Codoped Layered Cathode with Defects as Bifunctional Electrocatalyst for High-Performance Li-Ion Battery and Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Small 2021, 17, 2005605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wu, N. Ionic conductivity and ion transport mechanisms of solid-state lithium-ion battery electrolytes: A review. Energy Science & Engineering 2022, 10, 1643–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.N.; Islam, M.; Meena, A.; Faizan, M.; Han, D.; Bathula, C.; Hajibabaei, A.; Anand, R.; Nam, K.-W. Unleashing the Potential of Sodium-Ion Batteries: Current State and Future Directions for Sustainable Energy Storage. Advanced Functional Materials 2023, 33, 2304617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Cao, Z.; Lam Chee, M.O.; Dong, P.; Ajayan, P.M.; Shen, J.; Ye, M. Advances in Zn-ion batteries via regulating liquid electrolyte. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 32, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, Y.; Jaumaux, P.; Xu, Y.; Fei, Y.; Mo, X.; Wang, G.; Zhou, X. Research development on electrolytes for magnesium-ion batteries. Science Bulletin 2023, 68, 1819–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, L.; Yue, S.; Jia, S.; Wang, C.; Zhang, D. Electrolytes for Aluminum-Ion Batteries: Progress and Outlook. Chemistry – A European Journal 2024, 30, e202402017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, G.J.; Han, J.; Song, S.-W. Fire-Preventing LiPF6 and Ethylene Carbonate-Based Organic Liquid Electrolyte System for Safer and Outperforming Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, 12, 42868–42879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, M.D.; O'Dwyer, C. Density functional theory calculations for ethylene carbonate-based binary electrolyte mixtures in lithium ion batteries. Current Applied Physics 2014, 14, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.G.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, J.S. Dynamic observation of dendrite growth on lithium metal anode during battery charging/discharging cycles. npj Computational Materials 2022, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Sun, Q.; Lu, L.; Adams, S. Understanding and Preventing Dendrite Growth in Lithium Metal Batteries. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2021, 13, 34320–34331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, G.; Xiao, M.; Wang, S.; Han, D.; Li, Y.; Meng, Y. Polymer-Based Solid Electrolytes: Material Selection, Design, and Application. Advanced Functional Materials 2021, 31, 2007598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, M.; Xiao, Y.; Hu, H.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Y. Construction of covalent electrode/solid electrolyte interface for stable flexible solid-state lithium batteries. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 500, 157382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Pan, J.; Zhao, Y.; Liao, M.; Peng, H. Gel polymer electrolytes for electrochemical energy storage. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1702184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, J.; Pathak, T.S.; Santos, D.M. Applications of polymer electrolytes in lithium-ion batteries: a review. Polymers 2023, 15, 3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yue, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z. Thermal stable polymer-based solid electrolytes: Design strategies and corresponding stable mechanisms for solid-state Li metal batteries. Sustainable Materials and Technologies 2023, 36, e00587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, L.; Qi, L.; Oh, K.-S.; Hu, P.; Lee, S.-Y.; Chen, C. Gel polymer electrolytes for rechargeable batteries toward wide-temperature applications. Chemical Society Reviews 2024, 53, 5291–5337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Chai, J.; Du, H.; Duan, Y.; Xie, G.; Liu, Z.; Cui, G. Facile and Reliable in Situ Polymerization of Poly(Ethyl Cyanoacrylate)-Based Polymer Electrolytes toward Flexible Lithium Batteries. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2017, 9, 8737–8741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.; Santiago, A.; Judez, X.; Garbayo, I.; Coca Clemente, J.A.; Morant-Miñana, M.C.; Villaverde, A.; González-Marcos, J.A.; Zhang, H.; Armand, M.; et al. Safe, Flexible, and High-Performing Gel-Polymer Electrolyte for Rechargeable Lithium Metal Batteries. Chemistry of Materials 2021, 33, 8812–8821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.N.; Meena, A.; Nam, K.-W. Gels in Motion: Recent Advancements in Energy Applications. Gels 2024, 10, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Song, J.; Gao, Y.; Wang, D.; Liu, S.; Peng, S.; Usher, C.; Goliaszewski, A.; Wang, D. Supremely elastic gel polymer electrolyte enables a reliable electrode structure for silicon-based anodes. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Silva, S.R.P.; Zhang, P.; Liu, K.; Zhang, S.; Shao, G. A multifunctional fire-retardant gel electrolyte to enable Li-S batteries with higher Li-ion conductivity and effectively inhibited shuttling of polysulfides. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 467, 143378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Feng, X.; Chen, W. Progress in Gel Polymer Electrolytes for Sodium-Ion Batteries. ENERGY & ENVIRONMENTAL MATERIALS 2023, 6, e12422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Li, H.; Teng, Z.; Luo, Y.; Chen, W. MOF-modified dendrite-free gel polymer electrolyte for zinc-ion batteries. RSC Advances 2024, 14, 15337–15346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanchukwu, C.V.; Chang, H.-H.; Gauthier, M.; Feng, S.; Batcho, T.P.; Hammond, P.T. One-Electron Mechanism in a Gel–Polymer Electrolyte Li–O2 Battery. Chemistry of Materials 2016, 28, 7167–7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.K.L.; Pham-Truong, T.-N. Recent Advancements in Gel Polymer Electrolytes for Flexible Energy Storage Applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Deng, D.; Bai, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhao, X.; Xiong, X.; Lei, Y. Low-temperature resistant gel polymer electrolytes for zinc–air batteries. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2022, 10, 19304–19319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, H.; Girard; Gaetan, M.A.; Yunis, R.; MacFarlane, D.R.; Mecerreyes, D.; Bhattacharyya, A.J.; Howlett, P.C.; Forsyth, M. Preparation and characterization of gel polymer electrolytes using poly(ionic liquids) and high lithium salt concentration ionic liquids. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2017, 5, 23844–23852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, M.S.A.; Norrrahim, M.N.F.; Knight, V.F.; Nurazzi, N.M.; Abdan, K.; Lee, S.H. A Review of Solid-State Proton–Polymer Batteries: Materials and Characterizations. Polymers 2023, 15, 4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Xiao, Q.; Li, Q.-Y.; Liang, W.-C.; Chen, F.; Li, L.-Y.; Ren, S.-J. Cross-linked Electrospun Gel Polymer Electrolytes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2024, 42, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Cai, X.; Li, C.; Yao, J.; Liu, W.; Qiao, C.; Li, G.; Wang, Q.; Han, J. Construction of Alkaline Gel Polymer Electrolytes with a Double Cross-Linked Network for Flexible Zinc–Air Batteries. ACS Applied Polymer Materials 2023, 5, 3622–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.-H.; Lin, Y.-H.; Subramani, R.; Su, Y.-H.; Lee, Y.-L.; Jan, J.-S.; Chiu, C.-C.; Hou, S.-S.; Teng, H. On-site-coagulation gel polymer electrolytes with a high dielectric constant for lithium-ion batteries. Journal of Power Sources 2020, 480, 228802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.; Tang, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Shao, A.; Ma, Y. An in-situ polymerization strategy for gel polymer electrolyte Si||Ni-rich lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakrishnan, N.T.M.; Das, A.; Joyner, J.D.; Jabeen Fatima, M.J.; Raphael, L.R.; Pullanchiyodan, A.; Raghavan, P. Quest for high-performance gel polymer electrolyte by enhancing the miscibility of the bi-polymer blend for lithium-ion batteries: performance evaluation in extreme temperatures. Materials Today Chemistry 2023, 29, 101407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, W.; Kim, B.; Ryoo, W.S.; Earmme, T. A Brief Review of Gel Polymer Electrolytes Using In Situ Polymerization for Lithium-ion Polymer Batteries. Polymers 2023, 15, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel Stephan, A. Review on gel polymer electrolytes for lithium batteries. European Polymer Journal 2006, 42, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskoro, F.; Wong, H.Q.; Yen, H.-J. Strategic Structural Design of a Gel Polymer Electrolyte toward a High Efficiency Lithium-Ion Battery. ACS Applied Energy Materials 2019, 2, 3937–3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Li, G.; Wang, J.; Yang, G.; Lin, H.; Lin, J.; Ou, X.; Zheng, W. Gel Polymer Electrolyte Enables Low-Temperature and High-Rate Lithium-Ion Batteries via Bionic Interface Design. Small 2024, 20, 2404879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang Huy, V.P.; So, S.; Hur, J. Inorganic Fillers in Composite Gel Polymer Electrolytes for High-Performance Lithium and Non-Lithium Polymer Batteries. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzuto, C.; Teeters, D.C.; Barberi, R.C.; Castriota, M. Plasticizers and Salt Concentrations Effects on Polymer Gel Electrolytes Based on Poly (Methyl Methacrylate) for Electrochemical Applications. Gels 2022, 8, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Li, N.-W.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, S.; Cao, R.; Yin, Y.; Xing, Y.; Wang, J.; Guo, Y.-G.; Li, C. A Dual-Salt Gel Polymer Electrolyte with 3D Cross-Linked Polymer Network for Dendrite-Free Lithium Metal Batteries. Advanced Science 2018, 5, 1800559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Deng, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Yue, Y.; Ren, S. In Situ Cross-Linked Gel Polymer Electrolyte Membranes with Excellent Thermal Stability for Lithium Ion Batteries. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Dong, M.; Sun, K.; Feng, E.; Peng, H.; Lei, Z. A redox mediator doped gel polymer as an electrolyte and separator for a high performance solid state supercapacitor. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2015, 3, 4035–4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenough, J.B. How we made the Li-ion rechargeable battery. Nature Electronics 2018, 1, 204–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.N.; Singh, A.K.; Nam, K.-W. Cutting the Gordian knot of Li-rich layered cathodes. Matter 2022, 5, 2587–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, R.; Huang, J.; Liu, B.; Zhou, M.; Wen, B.; Xia, Y.; Okada, S. Flexible poly (vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene)-based gel polymer electrolyte for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. RSC advances 2021, 11, 11943–11951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zuo, X.; Wu, J.; Deng, X.; Xiao, X.; Liu, J.; Nan, J. Polyethylene-supported ultra-thin polyvinylidene fluoride/hydroxyethyl cellulose blended polymer electrolyte for 5 V high voltage lithium ion batteries. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2018, 6, 1496–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Xu, R.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhou, T.; Liu, M.; Wang, X. PVDF-HFP-SN-based gel polymer electrolyte for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. Nano Research 2023, 16, 9480–9487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Luo, H.; Liu, G.; Luo, C.; Niu, Y.; Li, G. High-performance gel polymer electrolytes derived from PAN-POSS/PVDF composite membranes with ionic liquid for lithium ion batteries. Ionics 2021, 27, 2945–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouraliraman, D.; Shaji, N.; Praveen, S.; Nanthagopal, M.; Ho, C.W.; Varun Karthik, M.; Kim, T.; Lee, C.W. Thermally Stable PVDF-HFP-Based Gel Polymer Electrolytes for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.; Zhao, M.; Xie, B.; Wang, X.; Jiang, M.; Guan, P.; Han, P.; Cui, G. A rigid-flexible coupling gel polymer electrolyte towards high safety flexible Li-Ion battery. Journal of Power Sources 2021, 499, 229944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Mishra, K.; Chaudhary, N.A.; Madhani, V.; Chaudhari, J.J.; Kumar, D. A sodium ion conducting gel polymer electrolyte with counterbalance between 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate and tetra ethylene glycol dimethyl ether for electrochemical applications. RSC Advances 2024, 14, 14358–14373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Sun, K.; Sun, W. Developing a novel polyurethane-based gel polymer electrolyte to enable high safety and remarkably cycling performance of sodium ion batteries. Journal of Power Sources 2024, 610, 234715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, S.; Tiwari, J.N.; Singh, A.N.; Zhumagali, S.; Ha, M.; Myung, C.W.; Thangavel, P.; Kim, K.S. Single Atoms and Clusters Based Nanomaterials for Hydrogen Evolution, Oxygen Evolution Reactions, and Full Water Splitting. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1900624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, R.; Tang, W.; Shi, Y.; Teng, K.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, R. Gel Polymer Electrolyte toward Large-Scale Application of Aqueous Zinc Batteries. Advanced Functional Materials 2023, 33, 2306052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.R.; Shafi, P.M.; Karthik, R.; Dhakal, G.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, M.; Shim, J.-J. Safe and extended operating voltage zinc-ion battery engineered by a gel-polymer/ionic-liquid electrolyte and water molecules pre-intercalated V2O5 cathode. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2022, 367, 120399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Zhang, G.; Rawach, D.; Fu, C.; Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Dubois, M.; Lai, C.; Sun, S. Polymer gel electrolytes for flexible supercapacitors: Recent progress, challenges, and perspectives. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 34, 320–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Jiang, W.; Jian, X.; Hu, F. Development of flame-retardant ion-gel electrolytes for safe and flexible supercapacitors. Science China Materials 2023, 66, 3129–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Liu, H. Insight of super-capacitive properties of flexible gel polymer electrolyte containing butyl imidazole ionic liquids with different anions based on PVDF-HFP. Journal of Polymer Research 2024, 31, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Huang, W.-T.; Huang, Y.-T.; Jhang, Y.-N.; Shih, T.-T.; Yılmaz, M.; Deng, M.-J. Evaluation of Polymer Gel Electrolytes for Use in MnO2 Symmetric Flexible Electrochemical Supercapacitors. Polymers 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, Z.; Li, G.; Melvin, D.L.R.; Chen, Y.; Bu, J.; Spencer-Jolly, D.; Liu, J.; Hu, B.; Gao, X.; Perera, J.; et al. Dendrite initiation and propagation in lithium metal solid-state batteries. Nature 2023, 618, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

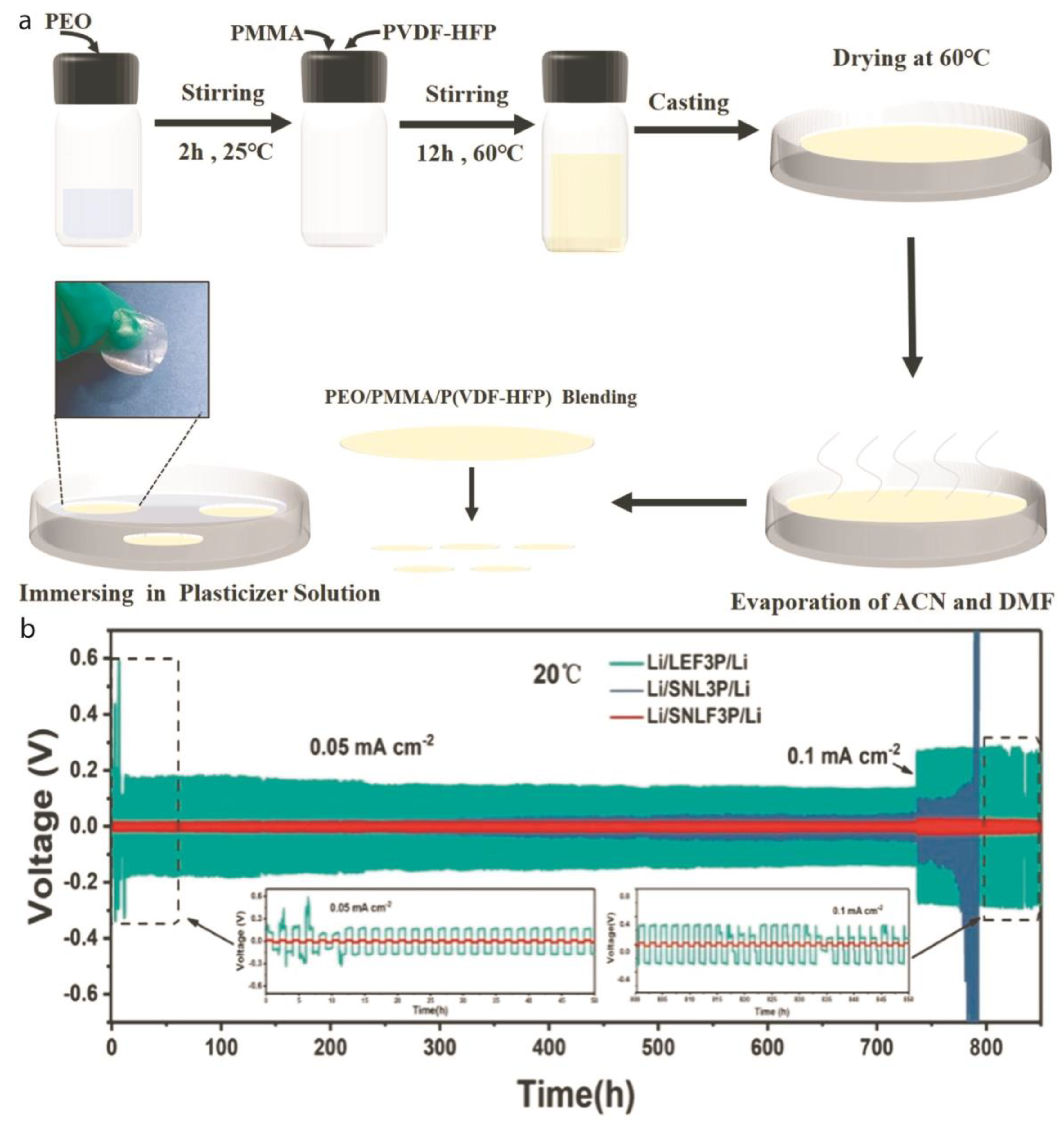

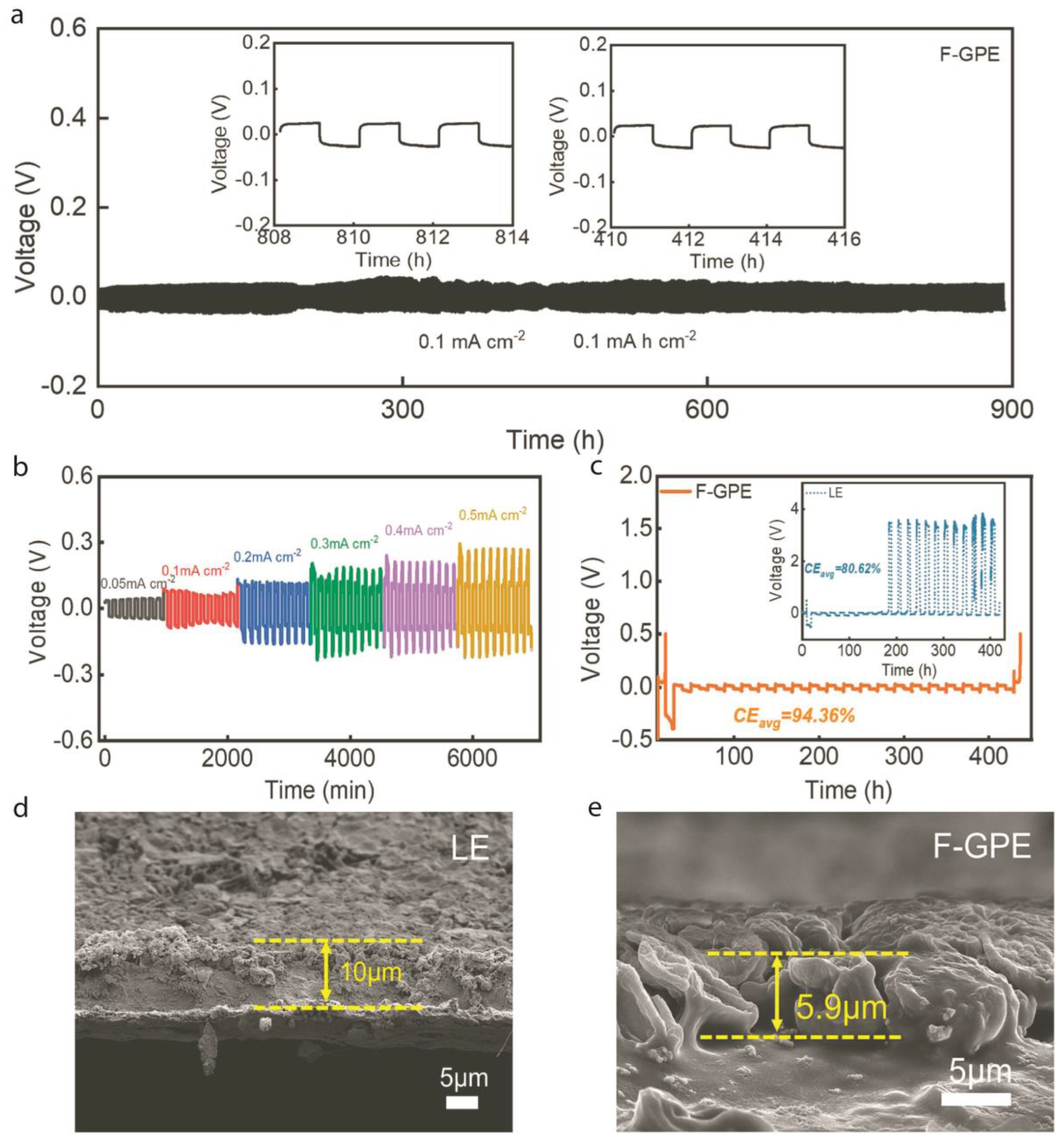

- Ye, X.; Xiong, W.; Huang, T.; Li, X.; Lei, Y.; Li, Y.; Ren, X.; Liang, J.; Ouyang, X.; Zhang, Q.; et al. A blended gel polymer electrolyte for dendrite-free lithium metal batteries. Applied Surface Science 2021, 569, 150899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, S.; Sheng, L.; Xue, W.; Wang, L.; Xu, H.; Zhang, H.; He, X. Challenges of polymer electrolyte with wide electrochemical window for high energy solid-state lithium batteries. InfoMat 2023, 5, e12394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Qiu, J.; Wen, Y.; Chen, J. In situ cross-linked fluorinated gel polymer electrolyte based on PEGDA-enabled lithium-ion batteries with a wide temperature operating range. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 467, 143311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.-J.; Sun, C.-C.; Fang, L.-F.; Song, Y.-Z.; Yan, Y.; Qiu, Z.-L.; Shen, Y.-J.; Li, H.-Y.; Zhu, B.-K. A lithiated gel polymer electrolyte with superior interfacial performance for safe and long-life lithium metal battery. Journal of Energy Chemistry 2021, 55, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabryelczyk, A.; Swiderska-Mocek, A. Tailoring the Properties of Gel Polymer Electrolytes for Sodium-Ion Batteries Using Ionic Liquids: A Review. Chemistry–A European Journal 2024, 30, e202304207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, L.; Shi, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Yuan, S. Gel Polymer Electrolyte with High Li+ Transference Number Enhancing the Cycling Stability of Lithium Anodes. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2019, 11, 5168–5175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).