1. Introduction

Pediatric soft tissue sarcomas (STS) are a rare and heterogeneous group of aggressive malignancies originating from mesenchymal cells, accounting for approximately 8% of all pediatric cancers [

1,

2]. These tumors predominantly affect children and adolescents under 18 years of age and encompass over 70 distinct histological subtypes, with rhabdomyosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma being the most prevalent [

3]. Despite advances in multimodal therapies—including surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy—the prognosis for pediatric STS remains dismal [

4]. While survival rates for localized disease have improved, the 5-year overall survival for advanced or metastatic STS remains as low as 8% [

5]. Moreover, existing chemotherapy is largely palliative and comes with significant toxicities and long-term adverse effects [

6,

7], underscoring the critical need for targeted therapies to improve outcomes for these vulnerable patients.

The cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme superfamily consists of monooxygenases responsible for metabolizing endogenous and exogenous compounds, playing critical roles in physiological and pathological processes [

8]. Among its members, CYP2W1 has emerged as a promising area of research due to its tumor-specific expression and aberrant reactivation in various human malignancies [

9]. In normal tissues, CYP2W1 is naturally expressed during fetal development, but is silenced after birth through methylation [

10]. Interestingly, recent studies have documented the reactivation of CYP2W1 expression in different cancers of epithelial origin such as the colon, colorectal, adrenal gland, breast, and hepatocellular carcinoma, with prevalence rates ranging from 30% to 60% [11-15]. However, the precise molecular mechanisms driving CYP2W1 dysregulation in human cancers remain unclear.

Regardless of its potential significance, this enzyme is still classified as an orphan enzyme due to its largely unknown biological function during development and substrate specificity [

9]. Clinically, CYP2W1 upregulation has been associated with tumor aggressiveness, including higher metastatic potential, advanced histological differentiation, and advanced tumor stage, making it a potential biomarker for poor prognosis in colorectal cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma [12,15-17].

Capitalizing on CYP catalytic activity, this cancer-specific CYP enzyme offer novel opportunities for developing selective targeted therapies for cancers expressing this enzyme. In preclinical studies, CYP2W1 demonstrates the ability to selectively bioactivate prodrugs, such as duocarmycin analogs and AQ4N, into highly cytotoxic metabolites within tumor cells [18-20], thereby minimizing damage to normal tissues. Moreover, its translocation to the tumor cell surface, as observed in colon cancer cells, facilitates its use as a tumor-associated antigen for immunotherapy-based treatments [

21,

22]. Integrating CYP2W1-prodrug activation with immunotherapy positions CYP2W1 as a key player in precision oncology, providing safer and more effective therapeutic options for cancer patients.

Despite its potential, the CYP2W1 expression profile and clinical significance in pediatric soft tissue sarcomas (STS) remain largely underexplored. Preliminary screenings by our group on mesenchymal tumors revealed CYP2W1 overexpression in a small subset of rhabdomyosarcomas, the most common pediatric STS subtype [

23]. In contrast, CYP2W1 protein was undetectable in the corresponding non-tumoral skeletal muscle of the same patients and in healthy skeletal muscle from independent pediatric controls [

23,

24]. Motivated by these findings and the therapeutic potential of CYP2W1 in cancer, this study aims to comprehensively investigate CYP2W1 expression across major STS subtypes affecting children and adolescents, evaluating its clinical relevance and prognostic value. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive analysis of CYP2W1 in multiple pediatric STS subtypes and clinical subsets to date.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Patient and Tissue Specimens

This study was conducted following approval by the Institutional Ethics and Clinical Research Committees of the National Institute of Pediatrics, Mexico (protocols INP-55/2008 and INP-053/2015). Informed consent for tissue use was obtained from patients or their guardians, with all patient information anonymized. The research adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Between December 2010 and December 2018, 42 paired primary STS tissue and adjacent normal tissue specimens were collected from pediatric patients (aged ≤18 years) undergoing open biopsy or surgical resection at the Department of Surgery, National Institute of Pediatrics. None of the patients had received chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy prior to sample collection. Tissue fragments were immediately preserved in RNA stabilization solution (RNAlater; Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) and stored at −80 °C until analysis.

Histological confirmation of all specimens was performed by expert pathologists. Adjacent normal tissue samples, located >5 cm from the tumor margin and confirmed as noncancerous by the pathologist, were selected based on the tumor's location and origin. Clinicopathological data, including patient age, sex, tumor grade, and stage, were retrieved from pathology reports and medical records. STS specimens were graded using the French Federation of Cancer Center Sarcoma Group (FNCLCC) system, which evaluates mitotic index, extent of necrosis, and histological differentiation. Tumors were classified into three grades: Grade I (low grade), Grade II (intermediate grade), and Grade III (high grade) [

25]. Tumor staging was determined using the TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors, categorizing tumors as Stage I, II, or III [

26]. Stage IV was excluded from the analysis as all tumors examined were primary and non-metastatic.

2.2. Total RNA and Protein Extraction

Total RNA and protein were extracted from the 42 pairs of STS tissues and adjacent normal tissues using TRIzol™ (Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA), following the manufacturer's protocol as described in our previous studies [

26,

27]. Briefly, each tissue sample (50–100 mg) was homogenized in 1 mL of TRIzol using a tissue disrupter, mixed with 200-μL of chloroform, and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 minutes to separate the organic and aqueous phases. RNA was retained in the upper aqueous phase, while proteins and DNA were partitioned into the lower phenol phase. The aqueous phase was precipitated with isopropanol, and the RNA pellet was washed with 150-μL of 70% ethanol, air-dried, and dissolved in 20 μL of DEPC-treated water. RNA concentration and purity were determined by the 260/280 absorbance ratio using a NanoDrop ND-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). RNA integrity was assessed via agarose gel electrophoresis, with visual confirmation of expected bands. The extracted RNA was stored at −70 °C until further analysis.

Total protein was isolated from the organic phase by precipitation with isopropyl alcohol, followed by centrifugation. The resulting protein pellet was washed with 0.3 M guanidine hydrochloride in 95% ethanol, then resuspended in a solution containing 10 mM urea and 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and sonicated until fully solubilized. Total protein concentration was measured using the Lowry method. The extracted protein was stored at −70 °C until further analysis.

2.3. Reverse Transcription-PCR, and Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 2 µg of total RNA extracted from 42 primary STS tissue samples and their corresponding normal tissues. The synthesis was performed using random hexamers and the TaqMan Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

The CYP2W1 mRNA expression level relative to β-actin mRNA level was measured by RT-qPCR using TaqMan probes, as described previously [

27]. Briefly, CYP2W1 mRNA level was measured by RT-qPCR using commercially available TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems) for CYP2W1 (Assay ID: Hs00908623_m1), with β-actin (Assay ID: 4333762F) as the reference gene serving as an internal control. Each reaction included 2 µL of cDNA, 1x TaqMan PCR Master Mix, and 100 nM of the TaqMan probe, in a final reaction volume of 20 µL. All RT-PCR reactions were performed in triplicate for each sample and analyzed using the ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The fold change in relative expression levels for CYP2W1 was calculated using the 2^−ΔΔCt comparative method [

27], with β-actin as the internal control. All samples were analyzed in triplicate and by independent experiments.

2.4. Western Blot Analysis of CYP2W1

Western blot assays were conducted following a standard protocol. Briefly, 40 µg of protein extracted from each primary STS and adjacent non-tumor tissue sample was loaded per lane. Proteins of CYP2W1-transfected 293T cells (sc-158417; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) were used as a positive control. Proteins were separated on a 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.5% Tween-20 at room temperature for 1 hour. The membranes were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with a commercially available, validated polyclonal anti-CYP2W1 antibody (1:1,000; ab113910, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Antigen-antibody complexes were detected using a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Life Science, Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire, UK). Membranes were stripped and re-probed with an anti-β-actin antibody (1:3,000, ab115777, monoclonal rabbit, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) as a loading control.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The sample size was determined based on the number of patients with treatment-naïve STS diagnoses who received care at our single center during the study period. Statistical analyses and graphical visualizations were conducted using SPSS Statistics version 20.0 (IBM, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, USA). Differences between groups were assessed using the t-test for continuous variables and either the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, depending on the data distribution. Overall survival in relation to protein expression was evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier survival curve and compared with the log-rank test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

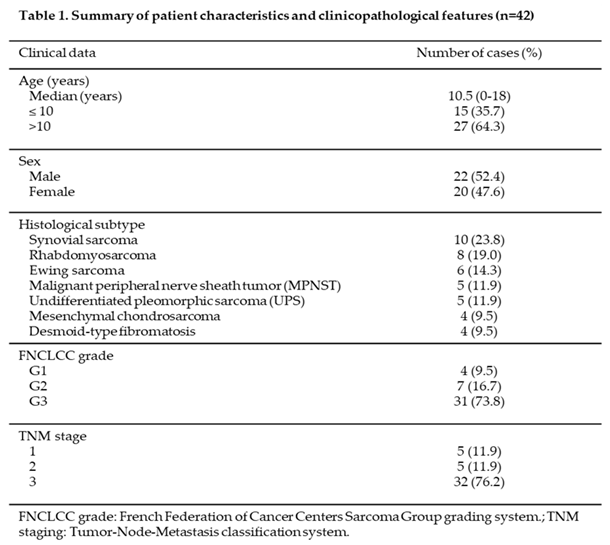

3.1. Baseline Demographic and Clinicopathologic Features

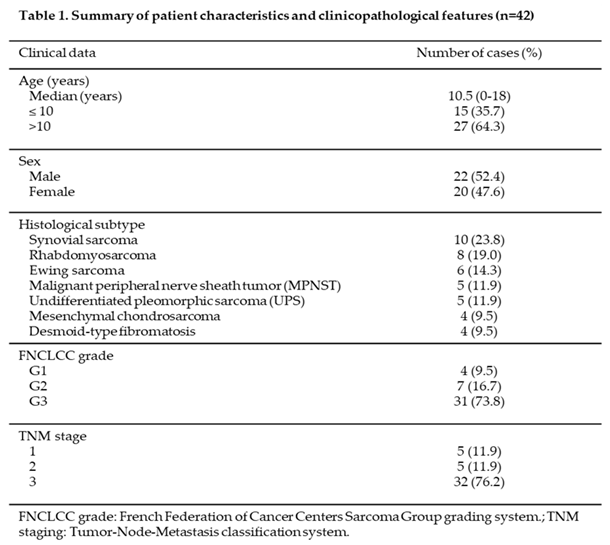

A total of 42 pediatric patients (<18 years at diagnosis) with newly diagnosed soft tissue sarcomas (STS) were included in the analysis. The baseline demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Of the cohort, 52% were male, with a median age at diagnosis of 10.5 years (range: 0–18 years). Seven histological subtypes of STS were identified, including synovial sarcoma (n=10), rhabdomyosarcoma (n=8), Ewing sarcoma (n=6), malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) (n=5), undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (n=5), mesenchymal chondrosarcoma (n=4), and desmoid-type fibromatosis (n=4). The majority of primary STS tumors were classified as Grade 3 (high grade) according to the FNCLCC grading system, accounting for 73.8% (n=31) of cases. Grade 2 (intermediate grade) and Grade 1 (low grade) tumors were less common, representing 16.7% (n=7) and 9.5% (n=4) of cases, respectively. Regarding TNM staging, most tumors were classified as stage 3 (n=32), reflecting a predominance of advanced disease within the cohort. Stages 2 and 1 were less frequent, with 5 tumors each, representing approximately 12% of cases per stage. These findings highlight the predominance of high-grade and advanced-stage tumors in this cohort of pediatric STS patient3.2. Increased CYP2W1 mRNA Expression in STS Tissues

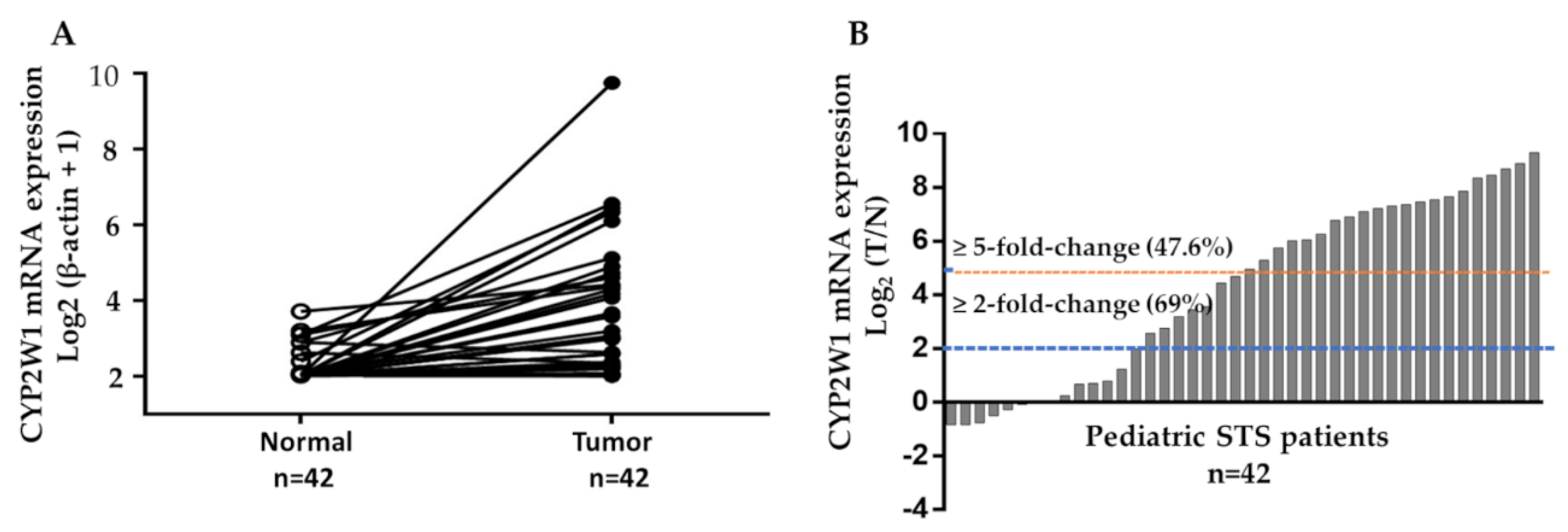

The mRNA level of CYP2W1 was determined by real-time quantitative RT-PCR assays in 42 paired of pediatric STS tumor tissues and their corresponding adjacent normal tissues. The expression levels of CYP2W1 mRNA were significantly higher in STS tissues than matched adjacent normal tissues (p < 0.001,

Figure 1A). In 29 of 42 cases, CYP2W1 mRNA was upregulated (≥2-fold change) in primary STS tissues relative to adjacent noncancerous tissues. Furthermore, 20 of these cases (47.6%) demonstrated a more pronounced overexpression, with a ≥5-fold increase (

Figure 1B). These results showed the upregulation of CYP2W1 mRNA levels in pediatric STS, suggesting its potential role in tumor biology.

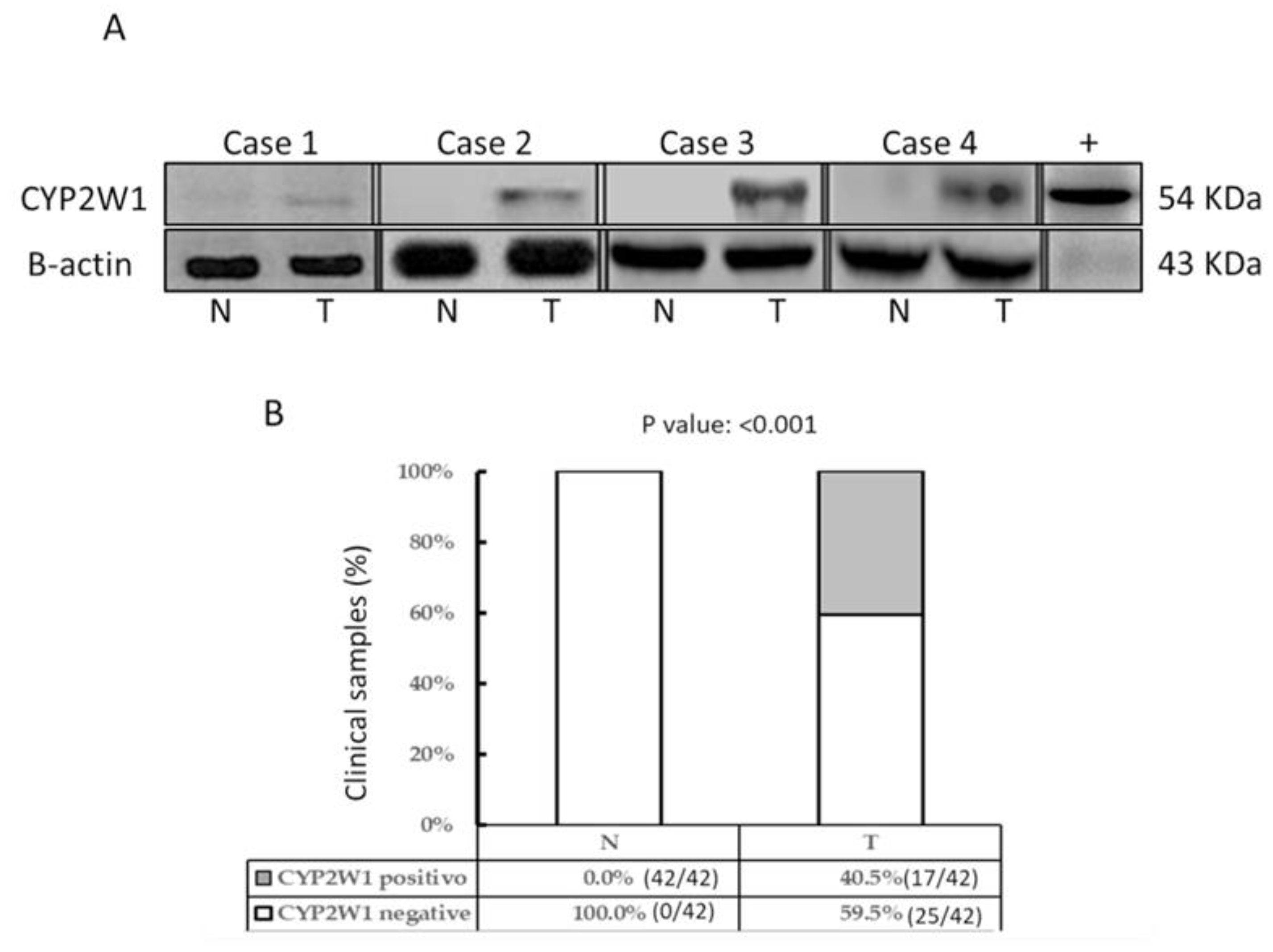

3.3. Aberrant Expression of CYP2W1 protein in STS Tissues

CYP2W1 protein expression was analyzed by Western blot in the same tissue samples previously assessed for mRNA levels. Representative immunoblot results are shown in

Figure 2A. Consistent with the mRNA expression profile, CYP2W1 protein was overexpressed in a subset of primary STS tumor tissues (17/42, 40.5%), but was undetectable in all paired adjacent normal tissues (0/42) (

Figure 2B). Differential expression was significant (p < 0.001).

Interestingly, aberrant CYP2W1 protein expression was exclusively observed in STS tumor specimens with significantly elevated mRNA levels (≥5-fold increase compared to normal tissues) (data not shown). This suggests a strong correlation between mRNA abundance and protein translation efficiency, further underscoring the tumor-specific expression of CYP2W1 in pediatric STS tissues.

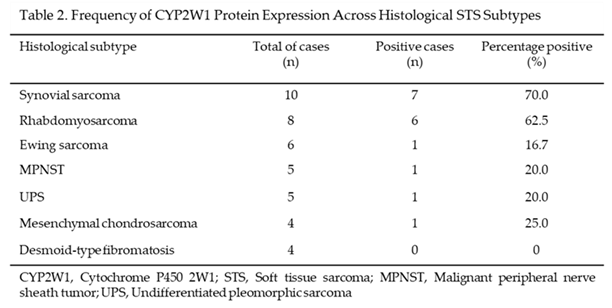

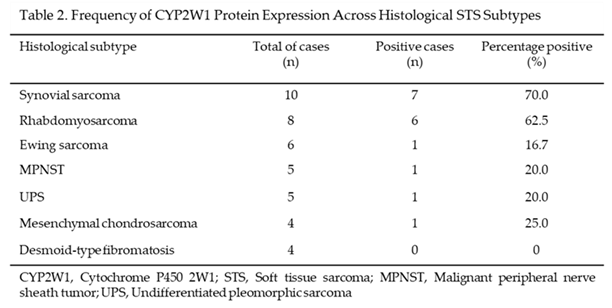

3.4. Frequency of CYP2W1 Protein Expression Across of Different Histological STS Subtypes

The frequency of CYP2W1 protein expression showed significant variability across different histological subtypes of pediatric STS tested, as shown in Table 2. Synovial sarcoma exhibited the highest frequency of aberrant CYP2W1 expression, with 70% (7/10) of cases testing positive. Similarly, a high expression rate was observed in rhabdomyosarcoma, with 62.5% (5/8) of tumors expressing CYP2W1. In contrast, lower expression frequencies were noted in Ewing sarcoma (16.7%, 1/6), malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) (20%, 1/5), undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (20%, 1/5), and mesenchymal chondrosarcoma (25%, 1/4). Notably, no CYP2W1 expression was detected in desmoid-type fibromatosis (0%, 0/4). Thus, if these results are validated in independent cohorts of pediatric patients, synovial sarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma could represent the most promising candidates for CYP2W1-based therapeutic strategies, given their notably high expression rates.

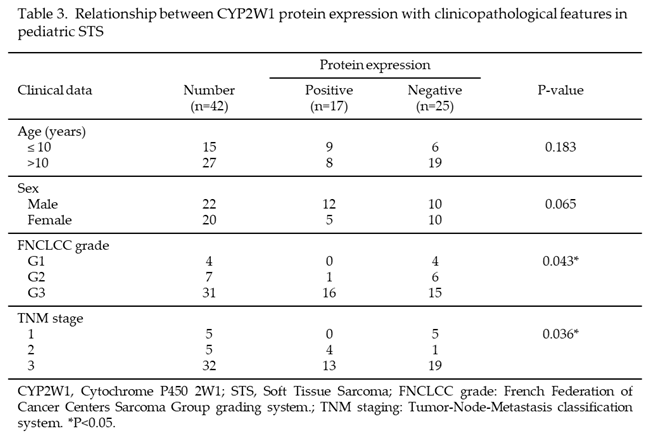

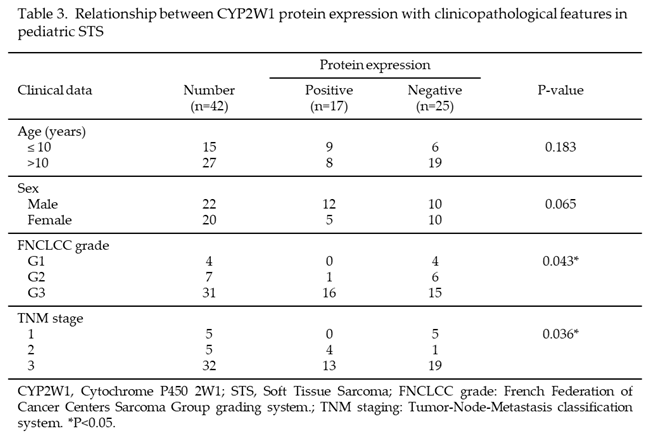

3.5. Association of Aberrant CYP2W1 Protein Expression with Clinicopathological Features

To assess the relationship between CYP2W1 protein expression and clinicopathological characteristics, cases were categorized into CYP2W1-positive (n=17) and CYP2W1-negative groups. As summarized in Table 3, no significant association was found between CYP2W1 expression and patients’ sex or age (p > 0.05). However, a significant association was identified between CYP2W1 protein expression and both high FNCLCC grade (p = 0.043) and advanced TNM stage (p = 0.036). For FNCLCC grades, CYP2W1 expression was most frequent in Grade 3 (high grade) tumors, with 51.6% (16/31) showing expression. In contrast, Grade 2 (intermediate grade) tumors exhibited CYP2W1 expression in 14.3% of cases (1/7), and no CYP2W1 expression was detected in Grade 1 (low grade) tumors (0/4). Similarly, CYP2W1 expression was significantly associated with TNM stages. Higher expression rates were observed in Stage 3 tumors (40.6%, 13/32) and Stage 2 tumors (80%, 4/5), while no CYP2W1 expression was detected in Stage 1 tumors (0/5). These findings suggest that CYP2W1 protein expression may play a role in the progression of pediatric STS, correlating with more aggressive and advanced disease features.

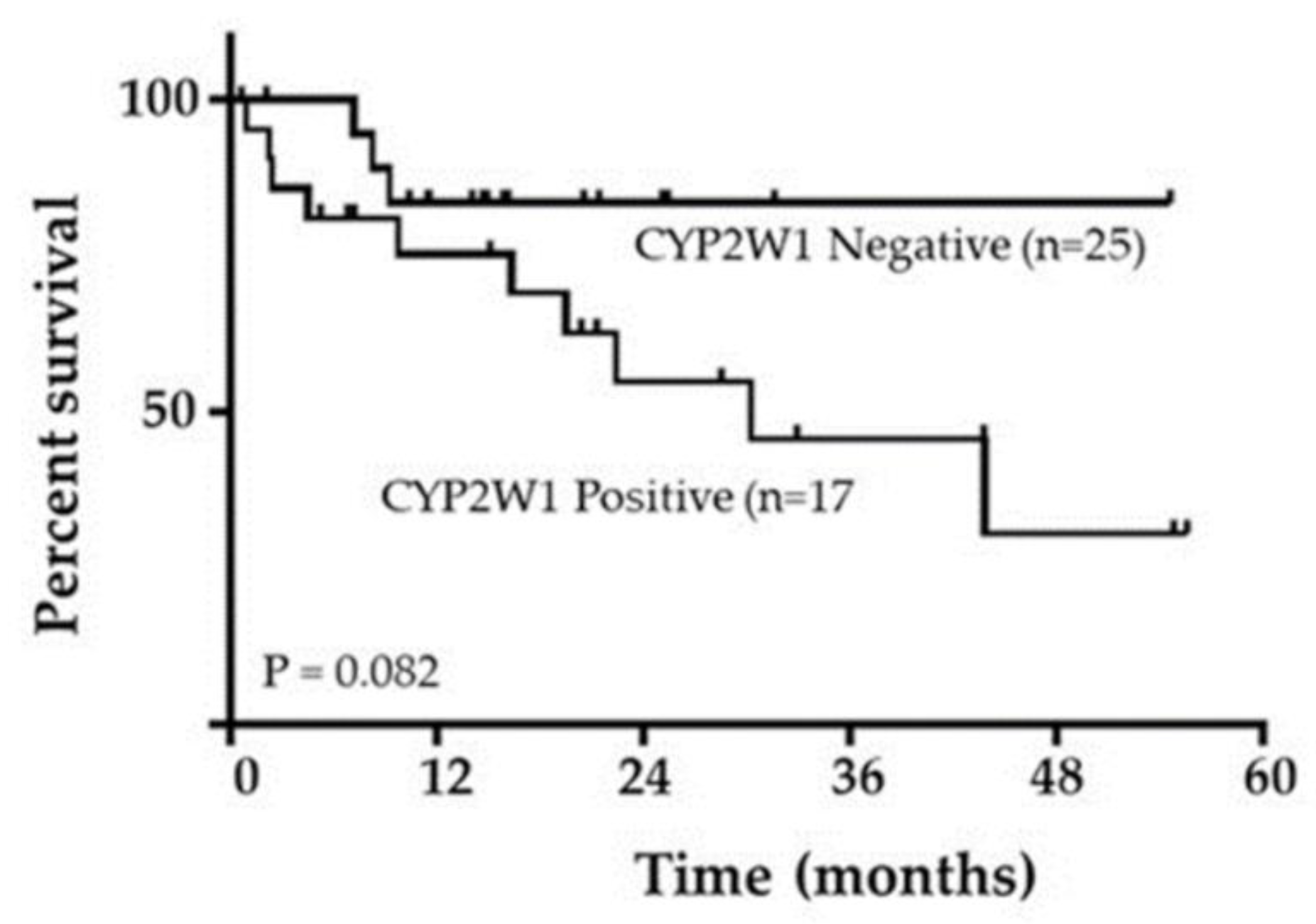

3.6. Survival Analysis and Prognostic Value of CYP2W1 Protein Expression

Patient survival outcomes were analyzed based on CYP2W1 expression status. Patients were grouped into those with negative CYP2W1 expression (49.5%, 25 cases) and those with positive CYP2W1 expression (40.5%, 17 cases). Kaplan- 252 Meier survival analysis and the log-rank test revealed a trend suggesting an association between CYP2W1 expression and shorter overall survival in pediatric STS patients. Although the trend did not reach statistical significance (log-rank test: P 255 = 0.082;

Figure 3), patients with CYP2W1 expression appeared to have poorer survival outcomes compared to those without expression. These findings highlight the potential role of CYP2W1 in influencing survival outcomes, warranting further investigtion with larger cohorts to confirm its prognostic significance.

4. Discussion

Pediatric STS represent a diverse group of aggressive malignancies with limited systemic treatment options, particularly in advanced or recurrent cases. Current therapies, such as cytotoxic chemotherapy, are associated with significant toxicity and offer only modest survival benefits [

29], emphasizing the urgent need for novel, targeted therapeutic approaches to develop more effective and less toxic therapies [

30]. In this context, CYP2W1 has emerged as a promising therapeutic target due to its tumor-specific expression and unique metabolic properties [

31]. Our findings provide the first comprehensive evidence of aberrant CYP2W1 expression across multiple pediatric STS subtypes and its potential clinical implications.

An initial screening conducted by our group identified CYP2W1 upregulation in a subset of rhabdomyosarcoma tumors, the most common pediatric STS subtype [

23]. Building on these findings, this study expands the analysis to characterize CYP2W1 expression across major pediatric STS subtypes, examining its clinicopathological associations and prognostic significance for the first time.

We demonstrated significant upregulation of CYP2W1 at both mRNA and protein levels in pediatric STS tissues compared to negligible or absent expression in adjacent normal tissues. Corresponding CYP2W1 protein was detected in 40.5% of tumor samples, while all matched normal tissues lacked detectable expression, suggesting selective activation of this enzyme in a significant subset of pediatric STS and reinforcing its potential as a targeted therapeutic candidate. These results align with findings from our initial screening in rhabdomyosarcoma [

23]. Importantly, the prevalence of CYP2W1-positive cases and the levels of detectable CYP2W1 observed in our study also are comparable to those reported in some adult epithelial-origin malignancies [31-33], where CYP2W1 has shown tumor-selective expression. This consistency suggests that CYP2W1’s tumor-specific reactivation and contribution to malignant behavior may represent a common feature among diverse cancer types, including pediatric STS.

In the current study, the highest expression frequencies of CYP2W1 protein expression were observed in synovial sarcoma (70%) and rhabdomyosarcoma (62.5%). These pathohistological subtypes are among the most aggressive and frequent pediatric STS subtypes [

34]. Other STS subtypes included in this study also displayed aberrant expression, but with only one positive case per subtype. In contrast, no CYP2W1 protein expression was detected in desmoid-type fibromatosis, a non-metastatic and well-differentiated subtype [

35]. These findings suggest a strong correlation between CYP2W1 expression and tumor aggressiveness, reinforcing its potential role in STS progression. Additionally, they identify synovial sarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma as key subtypes that could benefit from CYP2W1-targeted therapies in the future due to the frequent expression of CYP2W1 in these aggressive tumors. However, the study's limited sample size and uneven subtype representation restrict definitive conclusions. Larger, more balanced cohorts are needed to validate these results and further clarify CYP2W1’s role across specific STS subtypes.

Abundant evidence shows that CYP2W1 expression is associated with aggressive behavior and poor survival in epithelial-origin cancers, such as colorectal cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma [

16,

17,

32,

33]. In our study, significant associations were determined between CYP2W1 protein expression and histological grade and stage of the disease, both recognized markers of tumor progression [

36]. No CYP2W1 expression was observed in low-grade or early-stage. STS tumors, while high-grade and advanced-stage cases showed prominent expression, suggesting that CYP2W1 may play a role in tumor aggressiveness and progression in pediatric STS.

Our survival analysis revealed a trend toward shorter overall survival in patients with CYP2W1-positive tumors, although this did not reach statistical significance. This finding aligns with previous studies in colorectal and hepatic carcinomas [

32,

33], where CYP2W1 has been linked to tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis While our results indicate the potential of CYP2W1 as a prognostic biomarker, larger cohorts with extended follow-up are needed to validate these trends and establish its independent prognostic value.

To date, CYP2W1 stands out as the most tumor-specific member of the cytochrome P450 family identified in STS tumors. Unlike CYP1B1 and CYP2E1—two others notable P450 enzymes that, while expressed in various cancers, including pediatric STS [

37], are also present in corresponding normal tissues—CYP2W1 it appears is exclusively upregulated in tumor tissues, making it a uniquely selective therapeutic target. However, our study did not investigate the molecular mechanisms driving CYP2W1 activation in tumor tissues. Prior studies suggest that epigenetic dysregulation, such as CpG island demethylation, may play a critical role in reactivating CYP2W1 expression [

10,

11]. Similar epigenetic mechanisms are known to regulate other oncofetal genes, including carcinoembryonic antigen and trophoblast glycoprotein, which are aberrantly re-expressed in cancer [

38]. Therefore, future researcher is required to clarify the molecular mechanisms of CYP2W1 reactivation in primary STS tissues.

The fact that CYP2W1 is aberrantly overexpressed in a significant subset if primary STS tissues but is either found absent in normal tissues makes it a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of cancers expressing CYP2W1. These therapeutic strategies are CYP2W1-based immunotherapy, and CYP1B1-directed prodrugs []. CYP2W1-based therapies could selectively target tumor cells, providing safer and more effective treatment options, especially for aggressive subtypes like synovial sarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma. CYP2W1’s ability to bioactivate prodrugs, such as duocarmycin analogs and AQ4N, into cytotoxic agents highlights its substantial therapeutic potential [

31]. Furthermore, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) targeting CYP2W1 offer innovative treatment strategies that could enhance precision and efficacy [

22]. While CYP2W1-specific therapies are not yet commercially available, these approaches hold great promise for improving outcomes in pediatric STS. The development of CYP2W1-focused therapies, including prodrugs and immunotherapy, is essential to address the unmet clinical needs of this aggressive cancer.

Although our study findings are promising, we acknowledge some limitations that should be addressed in the future. First, due to the rarity of pediatric STS and the single-center nature of this study, the sample size and imbalance of histological subtypes included in our research was limited, and hence, the study was subject to selection bias. Second, our study cohort included a relatively small number of patients, and the follow-up time for evaluating patient survival was relatively short, which cause less statistical power. Third, the underlying mechanisms of CYP2W1 in pediatric STS patients were not investigated in this study. Therefore, our observations require large-scale clinical trials and multicenter clinical studies to be confirmed, involving more pediatric patients as well as defined larger groups of each subtype as well as clarify the molecular mechanisms of CYP2W1 overexpression in STS.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our research demonstrates that CYP2W1 is aberrantly expressed in a significantly subset of primary STS tumors, with the highest prevalence rates in synovial sarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma. Additionally, CYP2W1 expression is significantly associated with aggressive phenotype. These findings suggest that CYP2W1 could serve as a promising therapeutic target; however, its utility would be limited to individuals whose tumors demonstrate CYP2W1 expression. Future research should focus on validating its clinical relevance and exploring personalized therapeutic approaches tailored to CYP2W1-positive pediatric STS cases, offering a more targeted and effective treatment strategy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V-M (Araceli Vences-Mejia) and D.M-O.; methodology, C.T-Z. and D.M-O; validation, A.V-M (Araceli Vences-Mejia), C.T-Z. and D.M-O.; formal analysis, A.V-M (Araceli Vences-Mejia) and C.T-Z.; investigation, C.T-Z and D.M-O; obtaining informed consent from patients and/or Parents/Guardians, D.H-A, J.P-A. and J.S-K; surgical procurement of biological samples, D.H-A., J.P-A. and J.S-K; clinical follow-up of patients, R.C-C. and M.R.A-O; clinicopathological evaluation of patients and biological samples, R.C-C and M.R.A-O; data curation, R-S-P, E.H-U and V.D-G. writing—original draft preparation, A.V-M (Araceli Vences-Mejia), D.M-O and C.T-Z; writing—review and editing, A.V-M (Araceli Vences-Mejia), D.M-O and C.-T-Z; visualization, E.H-U, R.S-P-and V.D-G; project administration, A.V-M (Araceli Vences-Mejia), D.M-O; and C.T-Z; funding acquisition, A.V-M (Araceli Vences-Mejia) and D.M-O. All authors agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología Mexico, under grants 86395 and 262423.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review and Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Pediatrics, Mexico (INP-55/2008 and INP-053/2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients and/or their parents/guardians.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical concerns.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to all individuals and collaborators referenced who contributed to the successful completion of this research. In particular, we extend our heartfelt thanks to the medical residents who participated in the patient surgeries and to the staff of the Pathology Department at the National Institute of Pediatrics for their invaluable work in the histological classification of the biological samples used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ferrari, A.; Sultan, I.; Rodriguez-Galindo, C. Soft tissue sarcomas in children and adolescents: Pediatric versus adult sarcomas. Cancer 2010, 116, 2590–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collignon, C.; Carton, M.; Brisse, H.J.; Pannier, S.; Gauthier, A.; Sarnacki, S.; et al. Soft tissue sarcoma in children, adolescents, and young adults: Outcomes according to compliance with international initial care guidelines. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 46, 1277–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, M.E.; Taylor, A.L.; Martinez, P.R. Classification and characteristics of pediatric soft tissue sarcomas. Pediatr. Cancer Res. 2019, 15, 203–215. [Google Scholar]

- Sultan, I.; Rodriguez-Galindo, C.; Saab, R.; Yasir, S.; Casanova, M.; Ferrari, A. Soft tissue sarcomas in children and adolescents: An overview. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2010, 55, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpam, D.; Garg, V.; Ganguly, S.; Biswas, B. Management of refractory pediatric sarcoma: Current challenges and future prospects. OncoTargets Ther. 2020, 13, 5093–5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Bisogno, G. The management of pediatric soft tissue sarcomas. Pediatr. Drugs 2018, 20, 361–373. [Google Scholar]

- Pappo, A.S.; Dirksen, U. Rhabdomyosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and other soft tissue sarcomas of childhood and adolescence: Current concepts and future perspectives. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebert, D.W.; Russell, D.W. Clinical importance of the cytochromes P450. Lancet 2002, 360, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, A.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M. CYP2W1: An enigmatic P450 enzyme with an emerging role in cancer and therapeutic drug targeting. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009, 76, 443–451. [Google Scholar]

- Choong, E.; Stark, K.; McKinnon, R.A.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M. The roles of genetic and epigenetic variations in CYP2W1 expression in normal and tumor tissues. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choong, E.; Guo, J.; Persson, A.; Virding, S.; Johansson, I.; Mkrtchian, S.; et al. Developmental regulation and induction of cytochrome P450 2W1, an enzyme expressed in colon tumors. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edler, D.; Stenstedt, K.; Ohrling, K.; Hallström, M.; Karlgren, M.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M.; Ragnhammar, P. The expression of the novel CYP2W1 enzyme is an independent prognostic factor in colorectal cancer—a pilot study. Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchi, C.L.; Sbiera, S.; Volante, M.; Steinhauer, S.; Scott-Wild, V.; Altieri, B.; et al. CYP2W1 is highly expressed in adrenal glands and is positively associated with the response to mitotane in adrenocortical carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szaefer H, Licznerska B, Cykowiak, M., et al. Expression ofCYP2S1 and CYP2W1 in breast cancer epithelial cells and modu-lation of their expression by synthetic methoxy stilbenes.Pharmacol Rep 2019; 71: 1001–1005.

- Aiyappa-Maudsley, R.; Storr, S.J.; Rakha, E.A.; Green, A.R.; Ellis, I.O.; Martin, S.G. CYP2S1 and CYP2W1 expression is associated with patient survival in breast cancer. J. Pathol. Clin. Res. 2022, 8, 550–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenstedt, K.; Hallström, M.; Lédel, F.; Ragnhammar, P.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M.; et al. The expression of CYP2W1 in colorectal primary tumors, corresponding lymph node metastases, and liver metastases. Acta Oncol. 2014, 53, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edler, D.; Stenstedt, K.; Öhrling, K.; Hallström, M.; Karlgren, M.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M.; Ragnhammar, P. The expression of the novel CYP2W1 enzyme is an independent prognostic factor in colorectal cancer—A pilot study. Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo J, Wennerholm M, Ericson I, et al. The CYP2W1 enzyme: regulation, properties and activation of prodrugs. Drug Metab Rev. 2016;48(3):369–386.

- Travica, S.; Karlgren, M.; Stark, K.; Simonsson, U.S.H.; Jörntell, M.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M. Bioactivation of duocarmycin-based prodrugs by cytochrome P450 2W1 in tumor cells. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2013, 41, 631–637. [Google Scholar]

- McFadyen, M.C.; Melvin, T.; Murray, G.I.; Kerr, D.J.; Cassidy, J. Cytochrome P450 2W1 (CYP2W1): Potential for activation of the hypoxia-activated prodrug AQ4N. Front. Oncol. 2003, 3, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, A.; Nekvindova, J.; Travica, S.; Lee, M.-Y.; Johansson, I.; et al. Colorectal cancer-specific cytochrome P450 2W1: Intracellular localization, glycosylation, and catalytic activity. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010, 78, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch, A.; Kettenbach, J.; Humphreys, R.; Miller, M.L. Antibody-drug conjugates in pediatric oncology: Potential and challenges. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 3835–3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Ortiz, D.; Camacho-Carranza, R.; González-Zamora, J.F.; Shalkow-Klincovstein, J.; Cárdenas-Cardós, R.; Nosti-Palacios, R.; Vences-Mejía, A. Differential expression of cytochrome P450 enzymes in normal and tumor tissues from childhood rhabdomyosarcoma. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Ortiz, D.; González-Zamora, J.F.; Camacho-Carranza, R.; López-Acosta, O.; Colin-Martínez, O.; Domínguez-Ramírez, A.M.; Vences-Mejía, A. Xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes in skeletal muscle of children and adolescents. Pharmacol. Pharm. 2013, 4, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuville, A.; Chibon, F.; Coindre, J.-M. Grading of soft tissue sarcomas: from histological to molecular assessment. Pathology 2014, 46, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, E.; Huang, S.H.; Hosni, A.; Razak, A.A.; Jones, R.L.; Dickson, B.C.; Sturgis, E.M.; Patel, S.G.; O'Sullivan, B. Ending 40 years of silence: Rationale for a new staging system for soft tissue sarcoma of the head and neck. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2018, 15, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangkhathat, S. Current management of pediatric soft tissue sarcomas. World J Clin Pediatr. 2015;4(4):94-105. [CrossRef]

- Miwa, S. , Yamamoto, N., Hayashi, K., Takeuchi, A., Igarashi, K., Tsuchiya, H. Recent advances and challenges in the treatment of rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancers. 2020;12(7):1758. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.L.; Denny, C.T.; Tap, W.D.; Federman, N. Pediatric sarcomas: translating molecular pathogenesis of disease to novel therapeutic possibilities. Pediatr. Res. 2012, 72, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, E.C.; Pan, Y. Cytochrome P450 2W1 (CYP2W1) as a novel drug target in colon cancer therapy. Xenobiotica 2017, 47, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Chen, S.; Yu, J.; Shen, Z. Expression and prognostic significance of CYP2W1 in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 7669–7673. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Jiang, L.; He, R.; Li, B.-L.; Jia, Z.; Huang, R.-H.; Mu, Y. Prognostic value of CYP2W1 expression in patients with human hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 7669–7673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Characteristics of Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcomas: Recent Advances in Management and Treatment. Front. Oncol. 2023, Research Topic. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/37862/the-characteristics-of-pediatric-soft-tissue-sarcomas-recent-advances-in-management-and-treatment/magazine.

- Garcia-Ortega, D.Y.; Martín-Tellez, K.S.; Cuellar-Hubbe, M.; Martínez-Said, H.; Álvarez-Cano, A.; Brener-Chaoul, M.; Alegría-Baños, J.A.; Martínez-Tlahuel, J.L. Desmoid-type fibromatosis. Cancers 2020, 12, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramu, E.M.; Houdek, M.T.; Isaac, C.E.; Dickie, C.I.; Ferguson, P.C.; Wunder, J.S. Management of soft-tissue sarcomas; treatment strategies, staging, and outcomes. SICOT J. 2017, 3, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Zárate, C.; Vences-Mejía, A.; Espinosa-Aguirre, J.J.; Díaz-Díaz, E.; Palacios-Acosta, J.M.; Cárdenas-Cardós, R.; Hernández-Arrazola, D.; Shalkow-Klincovstein, J.; Jurado, R.R.; Santes-Palacios, R.; Molina-Ortiz, D. Expression of cytochrome P450 enzymes in pediatric non-rhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcomas: Possible role in carcinogenesis and treatment response. Int. J. Toxicol. 2022, 41, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidi, S.K.; Frietze, S.E.; Gordon, J.A.; Heath, J.L.; Messier, T.L.; Hong, D.; Boyd, J.R.; Kang, M.; Imbalzano, A.N.; Lian, J.B.; Stein, J.L.; Stein, G.S. Bivalent Epigenetic Control of Oncofetal Gene Expression in Cancer. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2017, 37, e00352–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).