1. Introduction

The experimental tests showed that the rapid realization of thermodynamically unstable processes is useful, both in the lubricant and on the surface of the friction pairs in the friction initial stage. This presupposes physic-chemical processes favoring friction, in operating conditions, such as polymerization, and formation of active substances, colloids, and other compounds, at the contact surface. The physic-chemical processes in the contact areas are complex and through the factors that influence them (pressure, sliding speed, temperature, and collisions between the asperities of contact surfaces, tribodestruction - i.e. the catalytic effect of the material and oxide layers on the lubricant) are conditions for a selective transfer. Thus, in the works [

1,

2,

3] it is defined that the friction in such conditions is called selective transfer and is used where the mixed and adhesion layers friction is not sufficiently reliable, or the duration of the use of the friction pairs is not insured.

As shown in the works [

1,

2], the lubricant tribodestruction leads to the friction beginning, under selective transfer conditions, both to the oxidation problem solution and to the formation of metal-organic compounds, colloids and surfactants that have the effect of transporting metal particles in the contact area, until establishing the balance between the contact area and the friction surface area is established, which inevitably leads to friction and wear reduction.

In the selective transfer process, the metals tend towards reducing oxides and are used both against oxidation to protect the rubbing surfaces and to create on the rubbing surfaces a special layer that takes without destruction the shear stress and thereby protects against wear, the base metal. Therefore, to reduce friction and wear during selective transfer, it avoids the oxidation both of metal and lubricant.

Research on the physic-chemical mechanism for friction and wear reduction in the selective transfer process [

1,

2,

4] led to the conclusion that is the action result of the self-regulating phenomena of equilibrium processes, disturbed in the work process, as well as of the friction force.

Practically, it must be used those lubricants that can self-regulate, i.e., not only work under selective transfer conditions but also friction conditions in the mixed and adhesion layers [

5], respectively like a polymerization in the contact areas [

6]. Therefore, the basis for the selective transfer is the physic-chemical processes of the tribodestruction of a lubricant and the electrochemical reactions, which occur in the friction pairs, leading to a self-regulation of the equilibrium processes, disturbed at the appearance of wear, as well as to a reduction of the friction force. For this reason, the selective transfer is a complex process that leads to pressure and shear resistance reduction in the contact zone, deformations compensation, and the formation of a layer of polymerized protection (also called “servowite” film) [

1,

2,

3], as a result of the energy flow, that appears in the friction process.

Depending on the materials couple (here the bronze/steel pair lubricated with glycerin) which works in the selective transfer conditions, the mechanism of the servowitte film formation on the friction surfaces can be diverse [

1,

2,

4]. Glycerin was used because, as shown in the papers [

1,

2,

3,

4,

7], it is a model liquid, achieves the selective transfer regime more easily than other liquids, and for the materials pair, one, should be a material copper-based. In the case of the bronze/steel friction pair, in the first period of operation occurs dissolution of the bronze friction surface, and the glycerin acts as a weak acid in the rubbing process. The bronze component elements atoms (Sn, Al, Zn, Fe, etc.) are transferred into the lubricating liquid, and the bronze surface is enriched with copper atoms [

8,

9,

10]. After this, the phenomenon repeats itself (the surface of the bronze through deformation in the friction process makes like new atoms of the bronze component elements that diffuse to the surface and reach the lubricating liquid).

Thus, the bronze surface becomes predominantly rich in copper, due to the release of these elements. As a result, gradually, the steel surface is covered with a thin layer of copper, and the layer on the bronze surface thins because it transfers to the steel surface, so a continuous dissolution of the bronze, it produced. This is happening until a 1...3 μm thick copper layer is formed on the bronze and steel surfaces in contact. The formation of the copper layer on the bronze surface is the result of the metal dissolution electrochemical process [

11]. Physic-chemical investigations of the servowite film structure [

3] allowed assuming that the film material is in a melt-like state. Thus, for bronze/steel friction pairs lubricated with glycerin, on the friction surfaces is formed the servowitte film (the lubricating material), as a result of the decomposition (at low temperatures) of the copper melt [

1,

2,

3] (which is a solid solution), easing in the diffusion process, the shear deformation. [

12].

The film has an oxide-free top layer and can transfer from one friction surface to another, i.e. adhere without an increase in the friction force and damage. Friction in the conditions of selective transfer in bronze/steel friction pairs can be compared to the sliding of a body on ice, during which the low friction coefficient is ensured by the copper film [

8,

9]. In addition, the functional behavior of machines, installations, devices, etc. is dependent on operating parameters (load, speed, operating environment, etc.), as well as on the initial quality of the contact surfaces, which changes continuously, with a lower or higher speed [

13,

14,

15,

16].

The surface roughness, physical-mechanical condition, the superficial layer microstructure, and the permanent stresses caused by mechanical processing or the final heat treatment are properties that characterize the contact surface quality of the friction pairs [

17,

18]. An important role in the operation of pairs with friction and minimal wear, as in the case of friction pairs with selective transfer, is played by the arrangement of the asperities of the friction surfaces [

19,

20,

21].

Therefore, specific to the selective transfer mechanism is the material transfer from one element of the friction pair to the other that manifests itself in the friction process of certain materials and the presence of suitable lubricants. This transfer takes place for a certain time, stabilizing at an optimal thickness, then, the process occurs in reverse (the transferred layer partially or returns to the initial element), surely leading to the improvement of the quality of the friction surfaces.

Also, the geometry of the friction pair surfaces influences their friction and wear behavior, which implies studying the friction surface asperities formed by selective transfer and analyzing the macro and microgeometric parameters.

The friction pairs contact surfaces are obtained by different technological processes, that generate the surface total profile of the surface [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Taking as the object of study friction surfaces with a well-defined outline to obtain precise information, an important role is played by the type of processing and the shape of the deviations obtained, which, based on statistical processing, can lead to the establishment of the quality of the surfaces [

30,

31]. Therefore, in this paper it is shown that the roughness in the contact area of the friction surfaces is minimal, as a result of the selective transfer, becoming optimal so that friction and wear are as low as possible, i.e. confers that equilibrium state for which the friction pair works with minimal friction and wear. Thus, the study and layout of the asperities of the friction surfaces formed by selective transfer to the spindle-bearing friction pair, becomes important through the analysis of their macro and microgeometric parameters, for the operation of pair with minimal friction and wear.

2. Materials and Methods

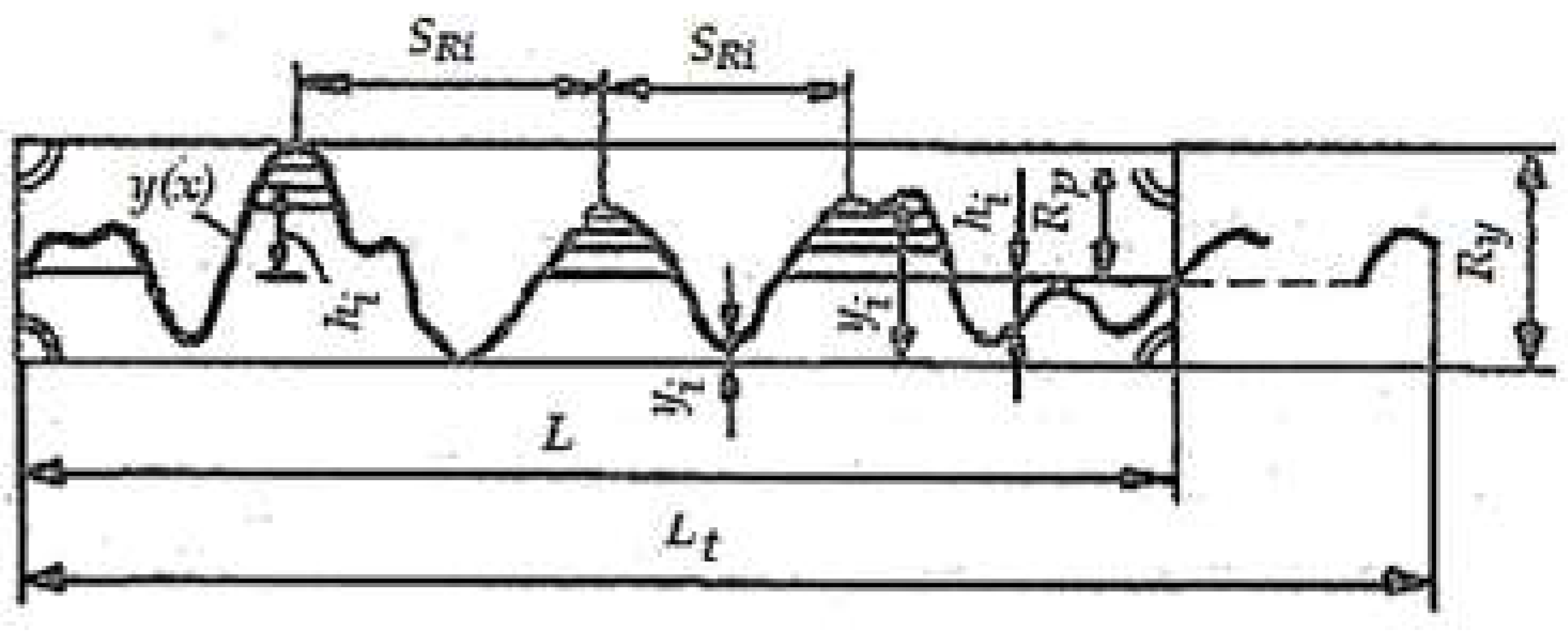

Assuming that the theoretical profile of the asperities of some surfaces is best indicated in

Figure 1, the recommendations regarding the choice of roughness characteristics [

2,

15,

16,

17,

18] for cases corresponding to practical applications are given in

Table 1.

To study the effect of selective transfer, the following roughness evaluation characteristics are recommended [

2]:

- –

average height of the asperities of the profile, Rz;

- –

height distribution function of the profile, p(y);

- –

real profile of the asperities;

- –

relative length of the asperity profile, Lr;

- –

complex parameter of surface roughness, Δ;

- –

autocorrelation function, R(x).

These are indispensable for the evaluation of friction and wear in the complex process produced by friction between the layers of the surfaces under the selective transfer conditions, which by possibilities special of specific reproduction, led to the simultaneous formation of optimal roughnesses in the process of operation.

For the studies carried out regarding the evaluation of the micro geometry change in the contact area of the friction pair elements in selective transfer mode were used a bushing of OLC 45 (AISI/SAE 1045) bushing which represents the spindle and a CuSn12T (UNS-C90800), which is bearing, lubricated with glycerin, at speed of v = 0.75 m/s and the pressure in the contact area, p = 0.8 MPa, operating for approximately 2.2 hours, i.e. z ≈ 105 operating cycles.

The lubricant that achieves the selective transfer regime more easily than other lubricants is glycerin, right for that in the research and experimental studies carried out under conditions of selective transfer, this lubricant was used. Thus, the viscosity of liquid substances (varies with temperature) represents one of the important properties that determine their behavior as lubricants, as a result it was analyzed the rheological behavior of glycerin.

The viscosity of glycerin at different temperatures was determined on an Ubbelohde-type capillary viscometer (

CANNON Instrument Company, Central Pennsylvania, USA), which is based on Poisseuile's law:

where:

where: V represents the volume of liquid that flows during time

t through a capillary of length

, l and radius

, r under the pressure difference

, Δ

p. From the relationship (1) results the dynamic viscosity

η or kinematic

ν:

ρ being the density of glycerin.

To have security that the glycerin viscosity determinations on the capillary viscometer are correct, the same determinations (presented in the table below –

Table 2) were also made on the rotating electric viscometer (TMAX Laboratory Equipments, Xiamen, Fujian, China), which is based on the following principle: if the fluid mass (here, glycerin) is rotated with a certain speed in a spherical body (here, cylindrical), the moment that opposes the rotation is directly proportional to the viscosity of the fluid (glycerin). The cylindrical (spherical) body is set in motion with an electric motor with adjustable speed.

3. Results and Discussion

As mentioned above, the lubricant that achieves the selective transfer regime more easily than other lubricants is glycerin, used to achieve the selective transfer, in the experimental research carried out.

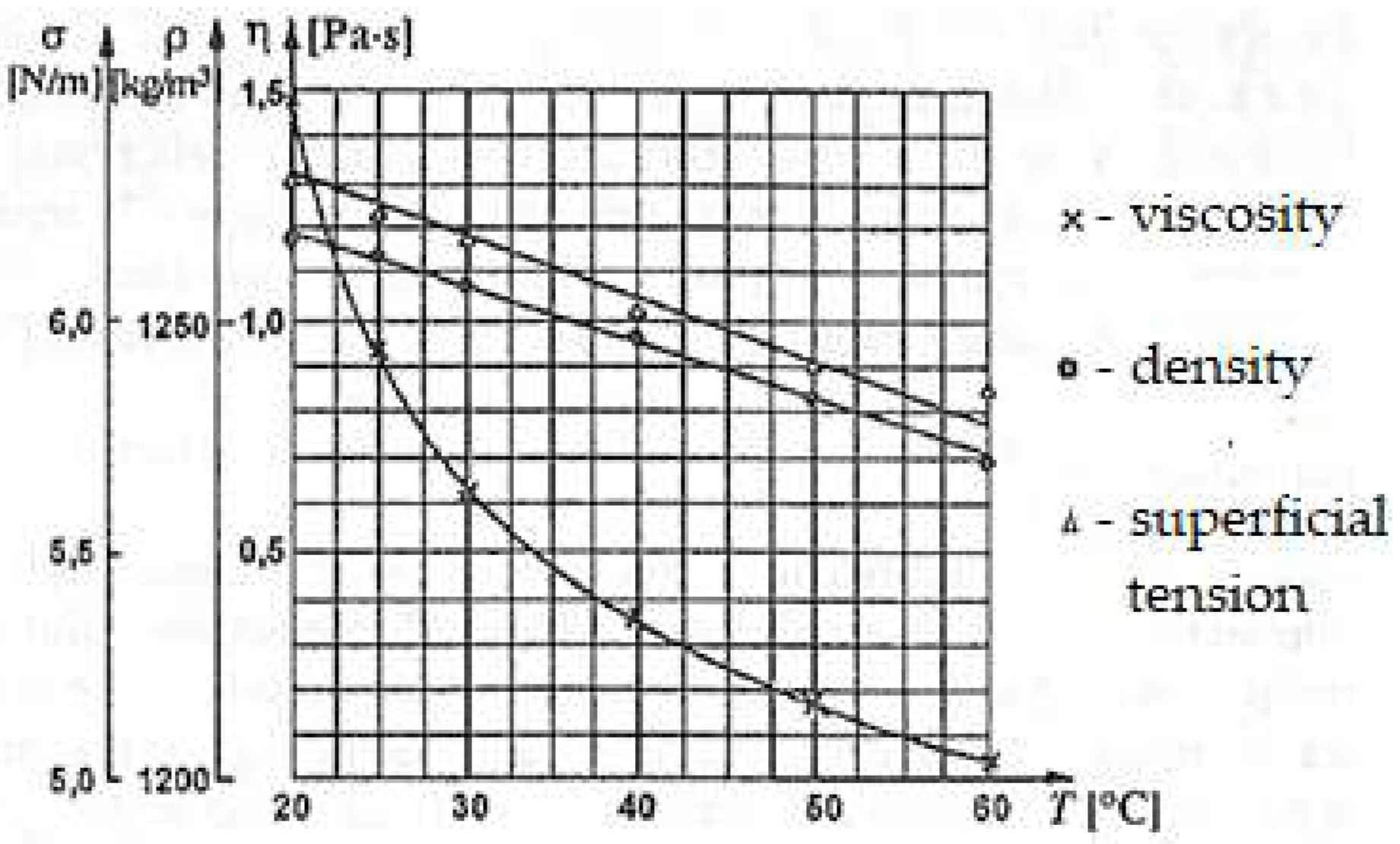

For this, the rheological behavior of glycerin was also analyzed [

32], by determining the viscosity, density, and superficial tension and how they vary with temperature. An additional characteristic equally important in the practice of lubrication is the thermal sensitivity of viscosity.

The obtained results are presented in

Table 2 together with those taken from the work [

33], for comparison.

The differences that appear between the values from one source to another are because they are for pure glycerine in the chemical engineer's manual, while technical glycerin was used on the viscometers from

Table 2, which also has a higher water content. From

Table 2 it can be seen that the viscosity and density values differ very little, thus proving the determination's correctness, and it can be stated that glycerin behaves like a Newtonian fluid. This is also confirmed by the graphic representations of viscosity, density, and surface tension with temperature in

Figure 2.

At the same time on the 4-ball machine/tribometer (RTEC Instruments, San Jose, USA) the load and time minimum seizure were also determined, and the obtained values are:

- –

seizure minimum load of 220 N, and the seizure minimum time of 2640 s, to the rolling friction;

- –

seizure minimum load of 80 N, and the seizure minimum time of 976 s, to the sliding friction.

It can be seen that glycerin supports a load and time of seizure of about 3 times greater at rolling friction compared to the sliding one.

From the point of view of friction and wear behavior, any surface must be characterized by the following dimensions:

- –

the maximum height of the roughness on the reference length, Ry;

- –

the average height of the roughness (in ten points), Rz;

- –

arithmetic average height (standardized parameter), Ra;

- –

the leveling depth of roughnesses, Rp;

- –

parameters of the Abbott – Firestone curve, b, and νp;

- –

the complex parameter of the micro geometry,

[

2,

15,

34,

35],

ra -being the average radius of the asperities;

- –

sliding direction;.

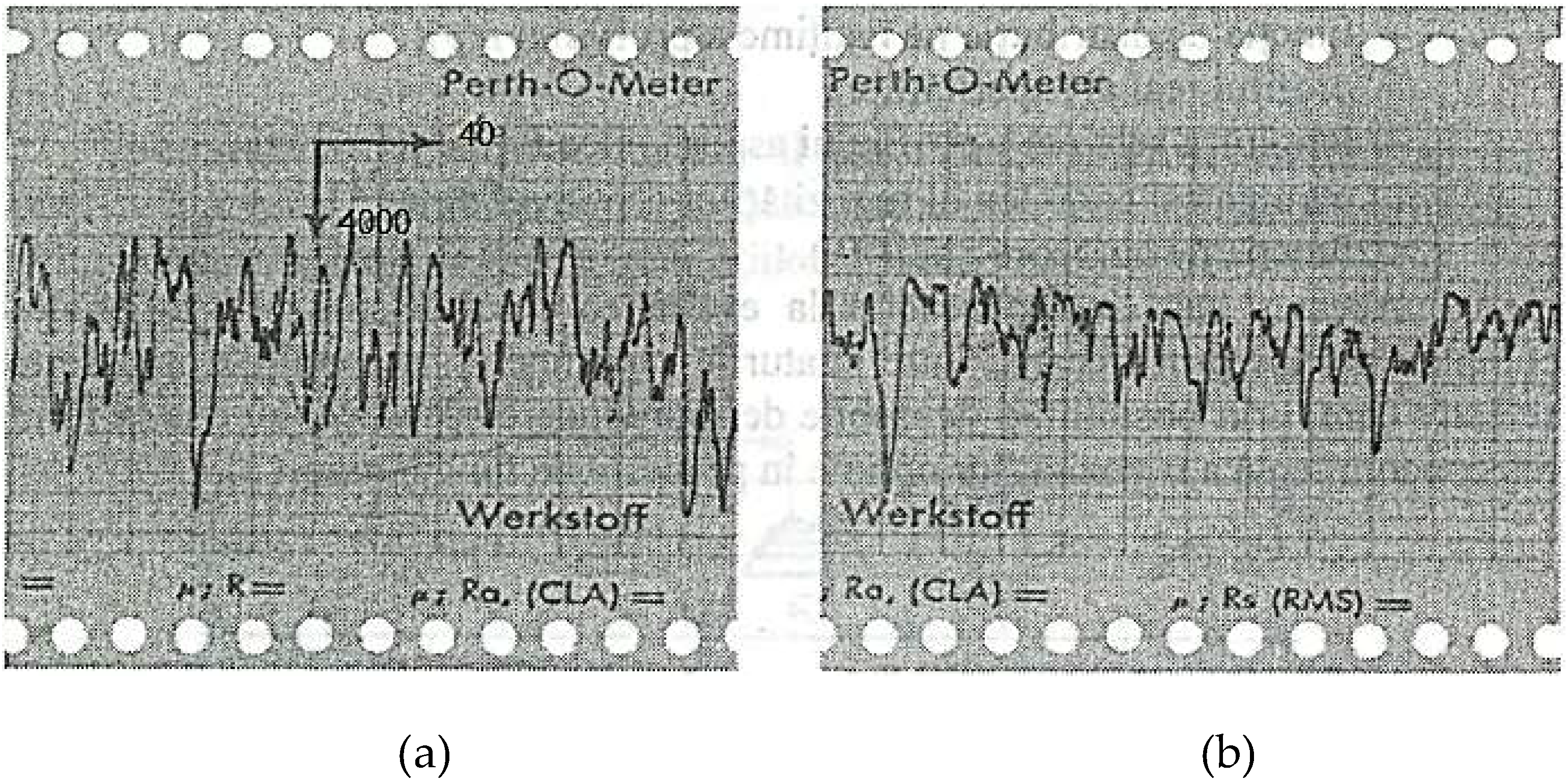

For the couple studied (spindle-bearing), the real profile of the friction surface roughness, before and after the experimental tests, is shown by the profilograms in

Figure 3.

A detailed analysis of the profilograms is necessary to highlight:

- –

the number of all maxima m on the standardized reference length L = 0.8 mm;

- –

the average frequency of peaks determined on the middle line of the profile, n being the number of peaks;

- –

the average slope of the roughness

[

2,

34], that will guide us to that equilibrium or optimal microgeometry, through which the friction process is characterized by a minimum friction coefficient and minimum wear intensity, also specific to the phenomenon of selective transfer [

2,

3,

7].

To study the state of the surfaces of this couple, before the experimental determinations (see

Figure 3a), the profilograms of the contact surfaces were drawn with the help of a Perth O. Meter profilograph ((Hirox Europe, Limonest, France

), and after the experiments with selective transfer (see

Figure 3b), the operation was repeated (the areas each time are the same).

Initially (see

Figure 3a), the spindle specimen had:

Ry = 7 μm;

Rz = 6.5 μm;

Ra = 1.5 μm;

Rp = 3.07 μm;

Lr = 5.6·10

-3 μm/mm;

b = 1.00;

νp = 1.07;

Δ = 0.357. After the experimental tests (

Figure 3b), under the conditions of selective transfer, the friction surface roughness parameters from the contact area have become:

Ry = 5 μm;

Rz = 4.6 μm;

Ra = 1.07 μm;

Rp = 2.8 μm;

Lr =1.55·10

-3 μm/mm;

b = 12.6;

νp = 1.07;

Δ = 0.123.

It should be noted that the values of these parameters were determined by measurement on the profilograms from

Figure 3, followed by the appropriate calculation according to refs.: [

33,

34,

35].

From the profilograms of the contact surfaces of the spindle specimen from OLC 45 ((AISI/SAE 1045), it can be seen how the asperities of the contact surfaces look after the mechanical processing, with varied and sharp shapes, the asperities having Ry, Rz, Ra, Rp, Δ much higher. In contrast, in the same areas after testing, on which a thin layer of copper was deposited, the asperities tend to become uniform (as if they were cut), so, it would correspond to the state after running-in, when obtained an optimal roughness, respectively a "balance" surface.

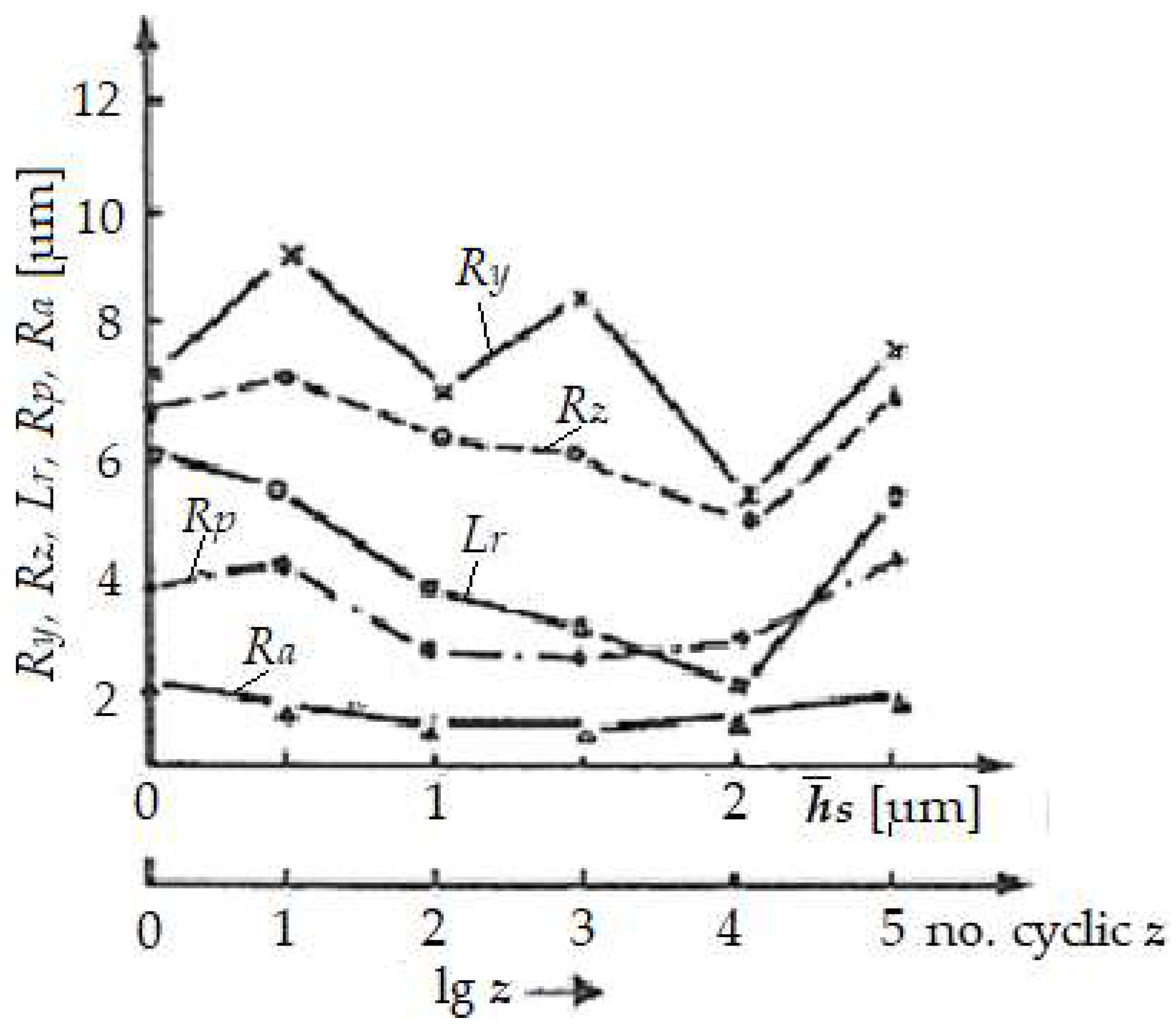

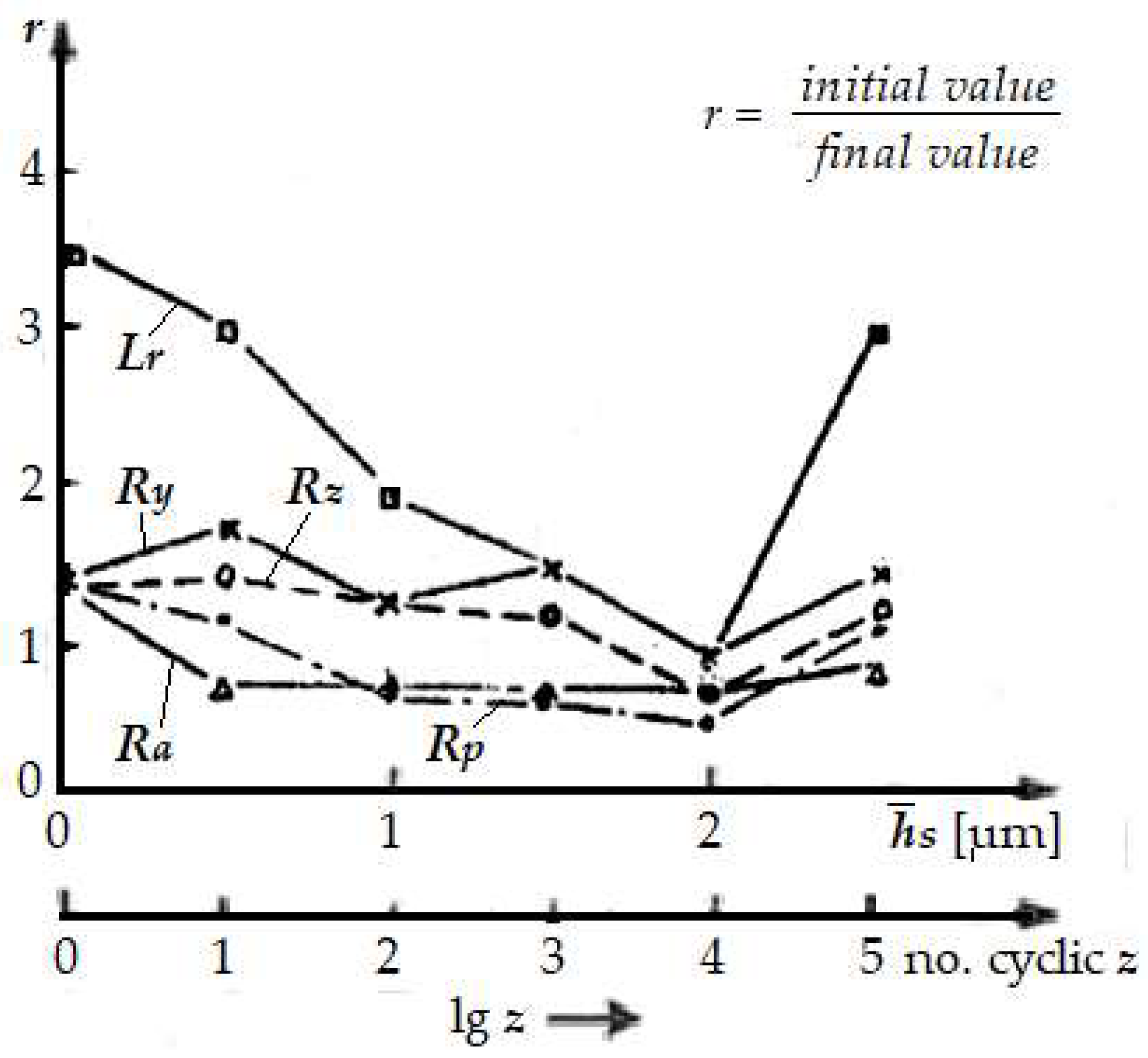

This proves that by selective transfer, the recesses between the asperities of the contact surfaces are filled with a thin layer of copper, up to a certain level corresponding to the optimal roughness, leading to the increase of the real contact surfaces and, therefore, to the decrease of the real contact pressure, having as an effect reducing friction and wear. Additionally,

Figure 4 shows the variation of the measured roughness parameters (

Lr,

Ry,

Rz,

Ra, and

Rp) depending on the average thickness,

of the copper layer transferred on steel specimen (from spindle-bearing pair), by friction in glycerine medium and the number of stress cycles,

z, when it was obtained the optimal roughness, respectively "balance" surface.

of the copper film generated on the steel specimen the spindle-bearing pair, by friction in the glycerin medium and the number of stress cycles, z for optimal friction conditions.

It was also represented in

Figure 5 the variation of the ratio

r between the initial and final values of these parameters depending on the average thickness of the transferred layer and the number of stress cycles, where the tendency of the ratios for

Ry,

Rz,

Ra,

Rp (tending to approximately the same value), so that at

= 2 μm and

z = 10

4 cycles and the ratio of the values of the parameter

Lr tends to the same value.

of the transferred layer and the number of stress cycles, z at the spindle-bearing pair.

This confirms the possibility of obtaining an optimal roughness and, therefore, the equilibrium surface for selective transfer. The way these parameters vary for z = 104 cycles, gives us minimal information on the roughness to be able to evaluate friction and wear. However, this created optimal conditions for a selective transfer, because a layer was deposited on the friction surfaces from copper-based alloys with an average thickness of 2 μm, which led to the reduction of roughness.

For example,

Ry from 7.0 μm has shrunk to 5.0 μm,

Rz from 6.5 μm to 4.6 μm, etc., and

Lr from 5.6·10

-3 μm/mm to 1.55 ·10

-3 μm/mm. These results show that through selective transfer, the copper layer changed the initial state of the roughness of the friction surfaces, transforming into a state of equilibrium of the roughness. From the study of the roughness traces and the graphic representations (see

Figure 4), it was found that

Lr and

Rz are the parameters that give the most information on the micro geometry of the surfaces obtained as a result of the selective transfer, and the standardized parameter

Ra is less useful.

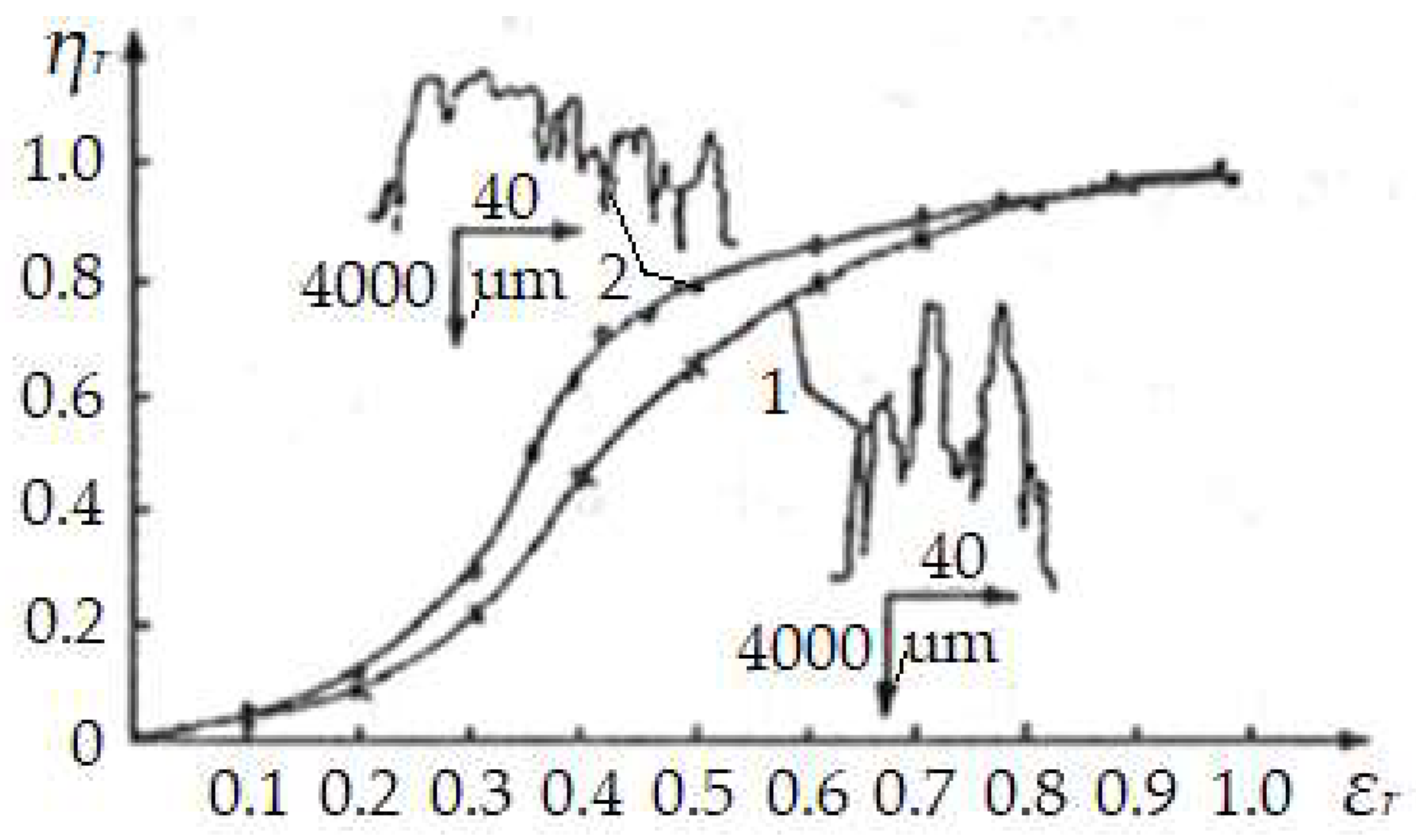

Analyzing the state of the surfaces before and after the deposition of the copper layer by sectioning, it can be seen from

Figure 6, the profiles and distribution curves of the roughness, with their quantitative and qualitative changes. The representation of

ηr as a function of

ε shows these changes both on the ordinate and on the abscissa (see

Figure 6), obtaining the parameters necessary for the calculation of friction and wear, according to the theory of deformations.

This is possible based on refs. [

34,

35], in which the Abbott – Firestone curve can be analytically expressed through a practical utility relationship in the form:

where:

ηr represents the relative ratio between the real and the nominal contact area;

ε = y/Ry – the relative deformation of roughnesses/asperities;

y – the absolute deformation, considered from the peak of the highest roughness/roughness and

Ry – the maximum height of the roughness/roughness on the reference length,

L (see

Figure 1);

b and

νp – parameters of the Abbott – Firestone curve, which depends on the material of the pair and the technological process of creating the friction surface.

Notes: The parameters of the Abbott – Firestone curve are calculated based on the profilograms of the surfaces (see

Figure 3), considering the discretized roughness model under the shape of rods of different heights (Kraghelski model) [

35].

An important role in the application of this theory belongs to the parameter,

Rz [

2,

34,

35,

36,

37]. All this leads to an optimal roughness for

z = 10

4 cycles in the rubbing process with copper film thickness,

= 2 μm.

The change in the density of the protrusions of the roughness profile

p(y) shows the characteristics of the wear process. Greater changes in the tilt density, of –2

o < φ < 2

o, show the friction and wear behavior under conditions of selective transfer [

38], where the distribution density is 97%. If in the initial state, the surfaces have an inclination range between -17

o< φ < 20

o, in the final state, after friction under selective transfer conditions, when the thickness of the transferred film is 2 μm, the inclination range is between -10

o < φ < 10

o.

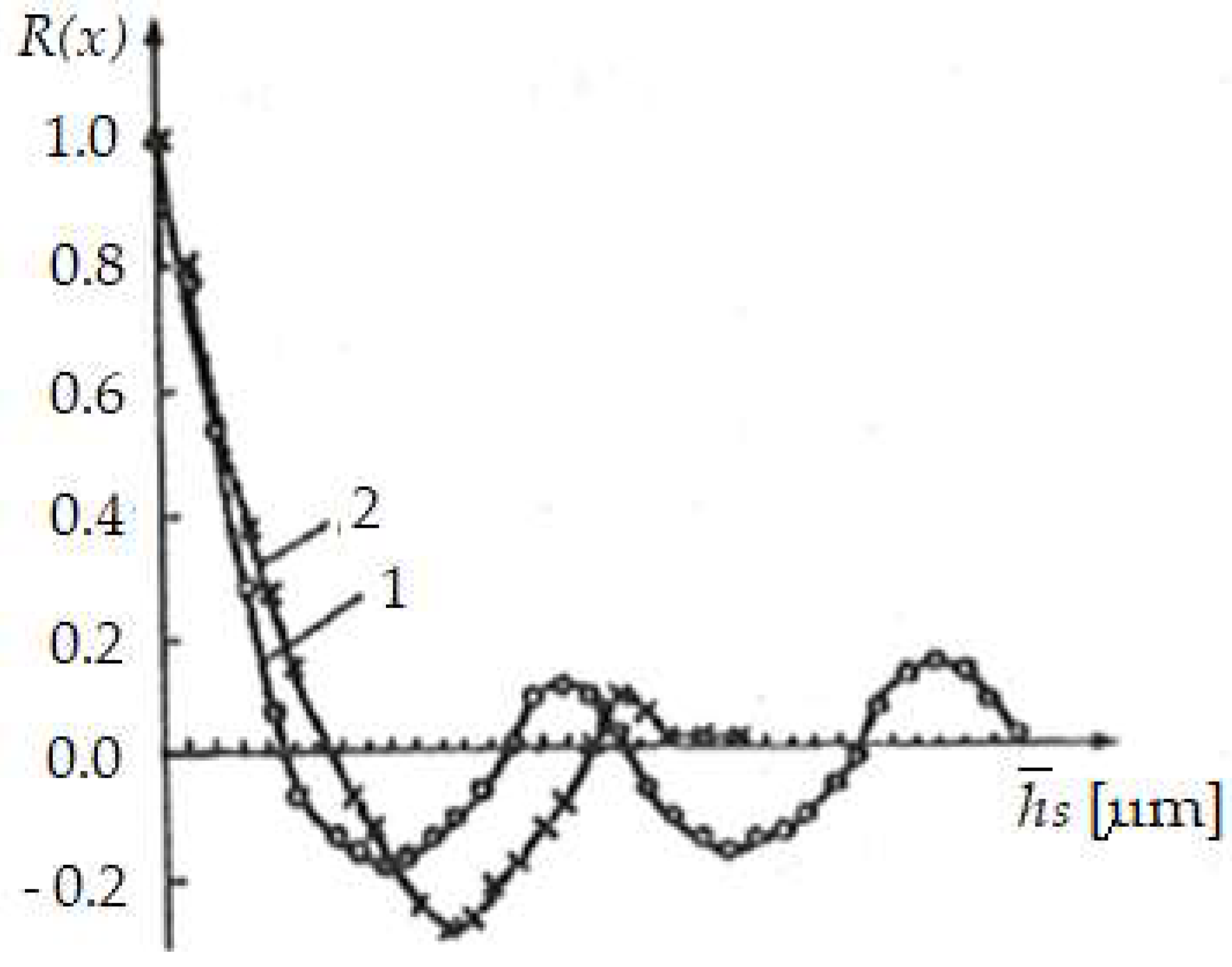

The description of the roughness profile for the normalization of the autocorrelation function

R(x) clearly shows the periodicity and the stochastic part in

Figure 7.

Curve 1 corresponds to the initial state of the surface of the spindle specimen from OLC 45, and curve 2 corresponds to the final state, after z = 104 friction cycles. The periodic part of the autocorrelation function from curve 1 is influenced by the execution technology of the friction pair elements in operation mode.

Finally, as a result of frictional operation under selective transfer conditions, the periodic part of the autocorrelation function decreases greatly, which shows that the wear of the transferred layer is very reduced.

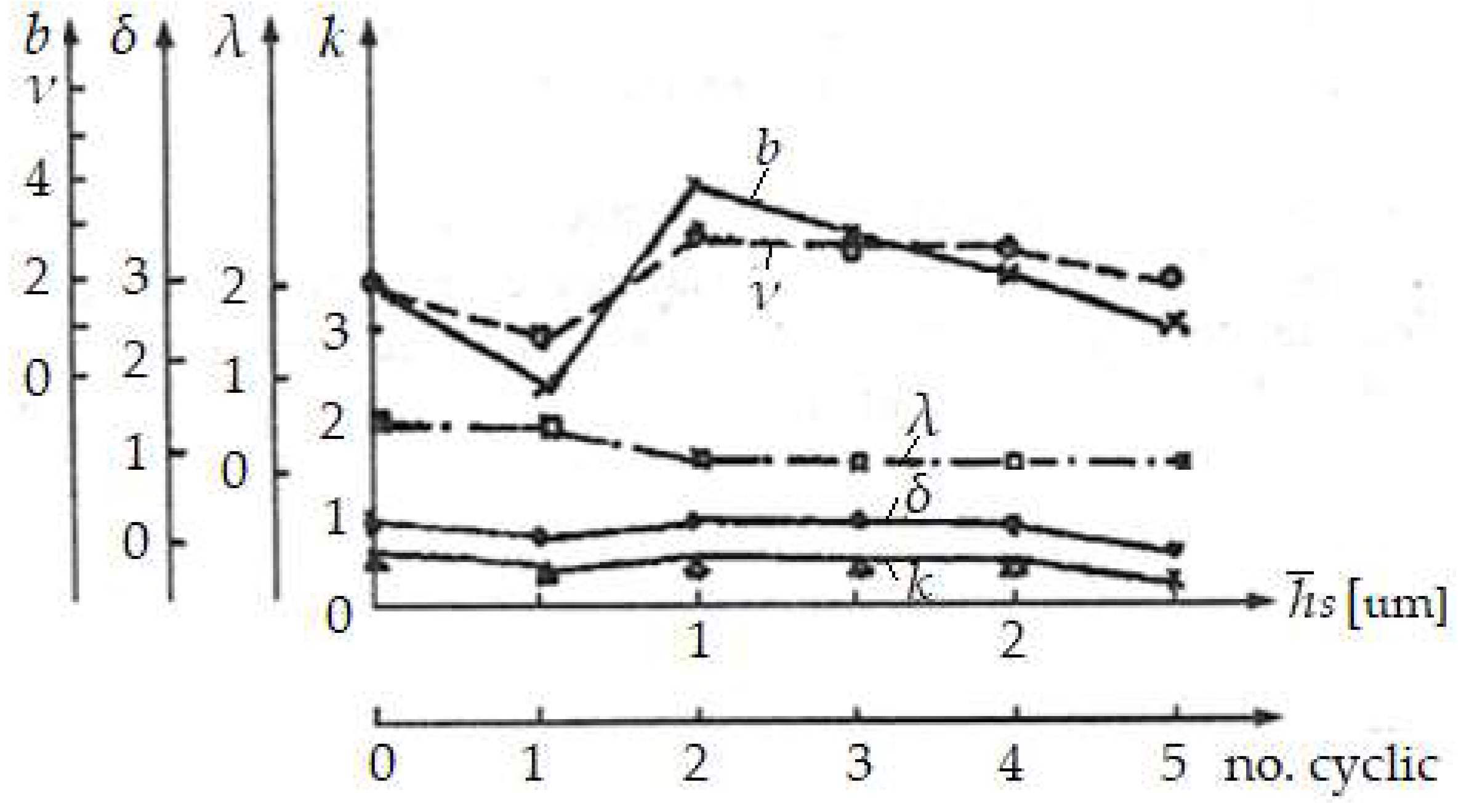

In

Figure 8 the variations of the lift curve parameters

b and

νp, of the complex parameter,

Δ, of the degree of profiling,

λ = Rp/Ry, of the fullness coefficient,

k = (Ry - Rp)/Ry and of the shape coefficient,

δ = R

a/R

p in depending on the average thickness of the transferred copper layer,

and the number,

z of stress cycles.

of the copper film transferred to the surface of the spindle specimen of the spindle-bearing pair, by friction in glycerin medium and optimal working conditions.

The analysis shows that these parameters contribute to a small extent to the evaluation of the selective transfer. For this reason, the parameters of the lift curve, b, and νp have a relatively large dispersion, as well as the complex parameter, Δ. So the parameters that are important in evaluating the selective transfer remain, Lr and Rz.

5. Conclusions

Evaluating the results of the roughness research on the spindle bushing and the flat specimen that functioned by friction under the conditions of the existence of the selective transfer effect, they showed that the wear is extremely low and the coefficient of friction is low.

It is observed that the selective transfer action, as a result of the copper layer formation on the spindle surface, occurs at Rz = 4.6 μm, and the Lr parameter decreases to 1.5·10-3 μm/mm for the spindle specimen, respectively in these experiments, the inclination angle, φ was included between the limits of –2o < φ < 2o and the distribution density of 97%.

It follows that for the study of the selective transfer and the research of the friction surface roughness, the kinematics of the elements of the friction pairs must be taken into account, where the friction takes place with the release of heat, influencing the appearance and development of the selective transfer. In optimal conditions by selective transfer, a copper film of about 2 μm (in thickness) appears on the friction surfaces, with little roughness.

It turns out that the roughness, after the appearance of the copper film, as a result of the selective transfer, is minimal, becoming optimal so that friction and wear are reduced as much as possible. These are in correspondence with the modern hypotheses, unanimously accepted that in the presence of a quasi-liquid copper layer between the layers of friction surfaces, friction, and wear are minimal.

For this, the useful roughness parameters, researched by selective transfer, were the roughness profile average height, Rz, and the relative length of the roughness profile, Lr.

The optimal conditions for selective transfer correspond to the generation of a copper film with an average thickness of 2 μm in the contact area of the friction surfaces, giving them that equilibrium state for which it works with minimal friction and wear.