Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location and Experimental Units

2.2. PRRS Vaccination and Blood Sampling

2.3. Genotyping and Quality Control

2.4. Genome-Wide Association Study

2.5. SNP Validation Genotyping

2.6. Statistical Analysis of the Genotype to Phenotype Validation Study

3. Results

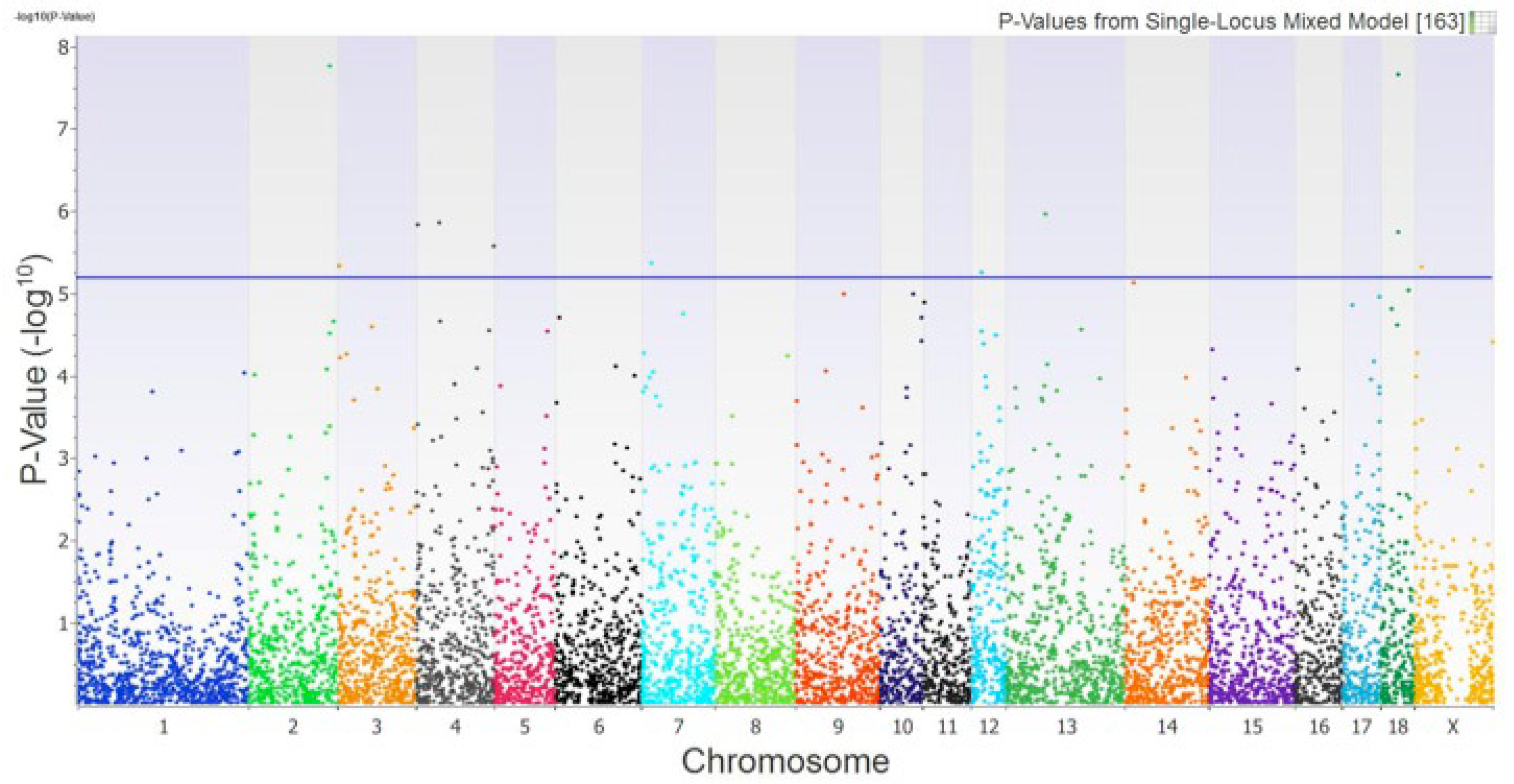

3.1. Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS)

3.2. SNP Validation Study

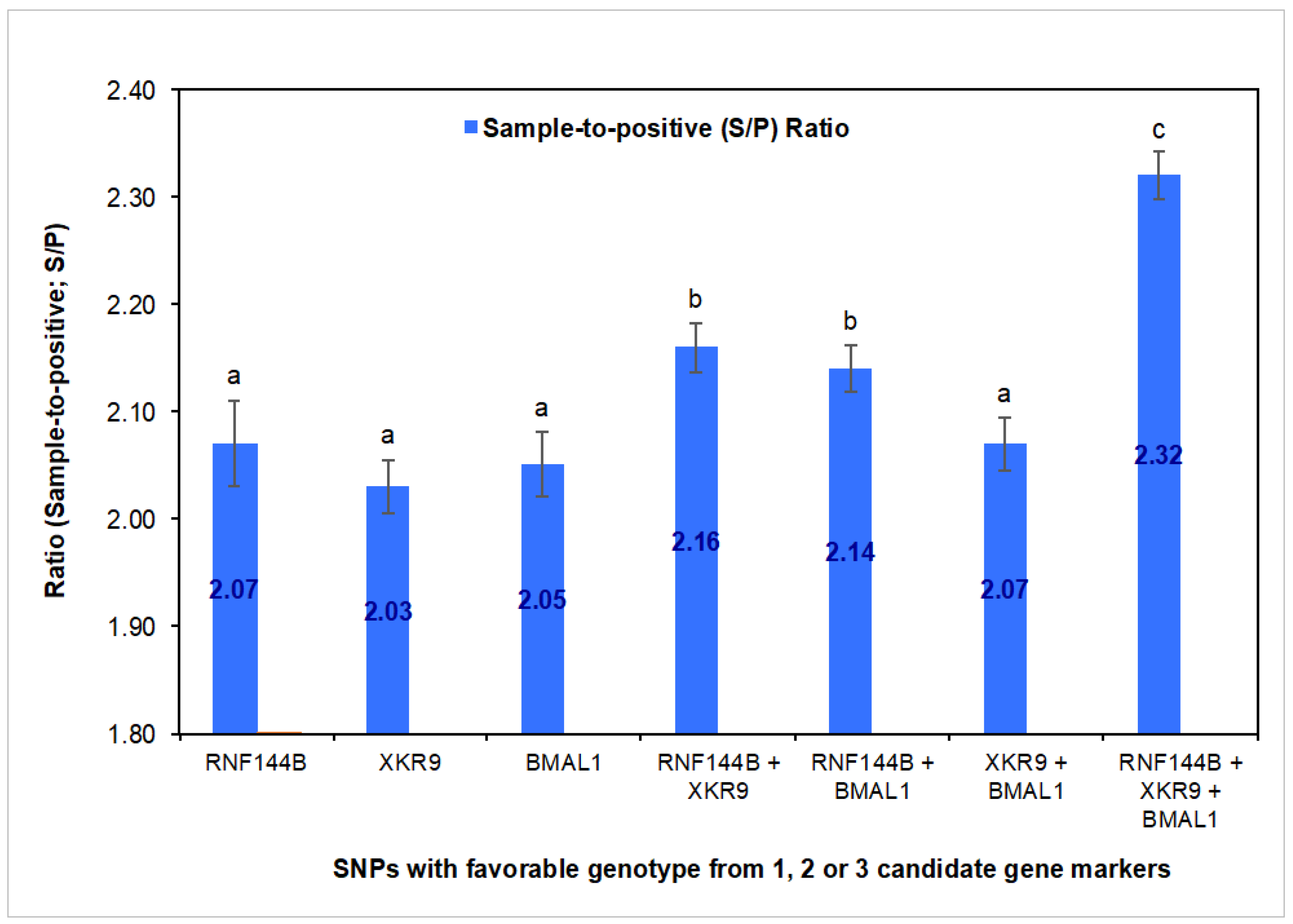

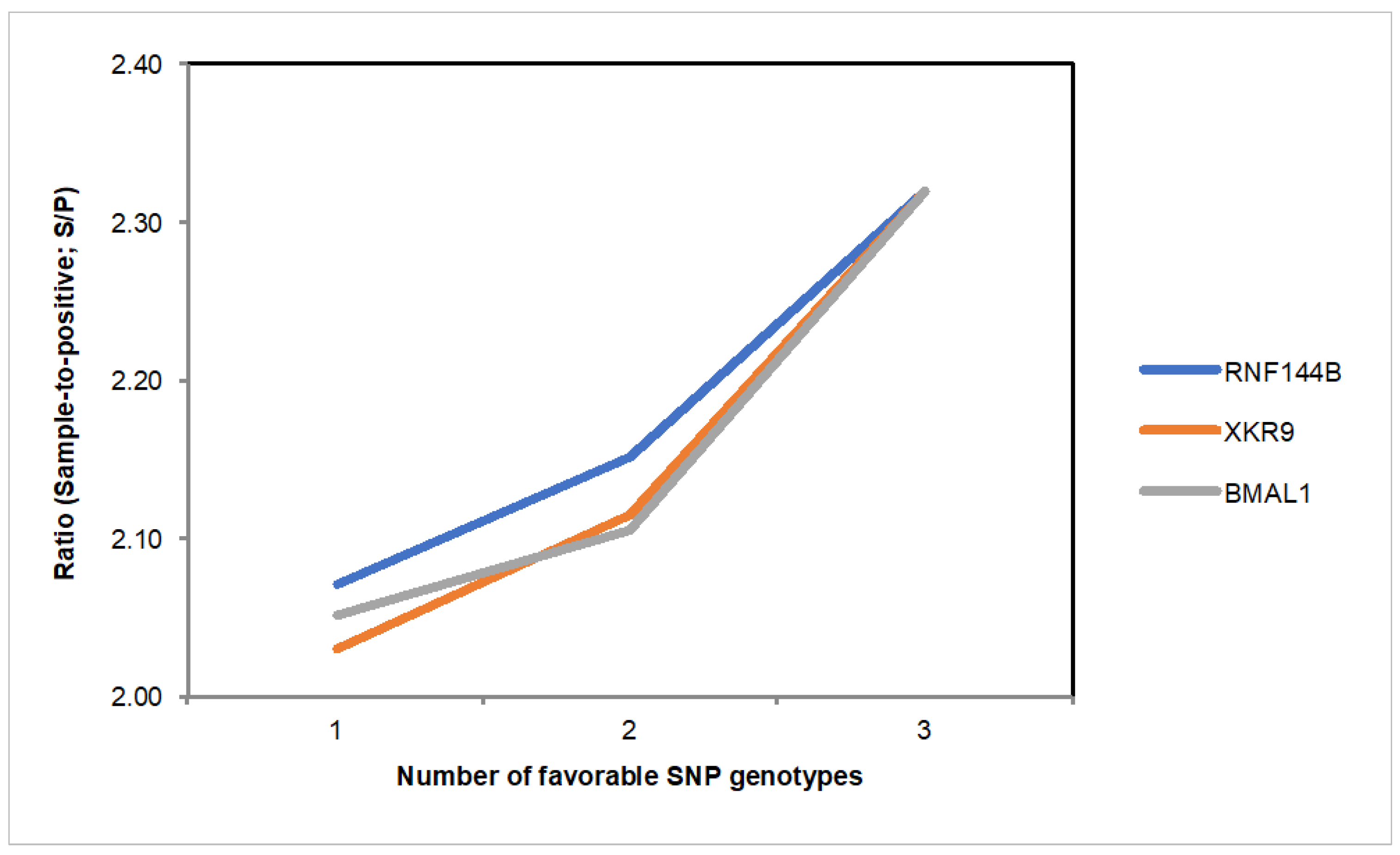

3.3. SNP Genotype Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- López-Heydecka S.M.; Alonso-Morales, R.A.; Mendieta-Zerón, H.; Vázquez-Chagoyán, J.C. Porcine respiratory and reproductive syndrome: Review. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pec. 2015, 6(1), 69-68.

- Zimmerman, J.; Locke, A.K.; Ramirez, A.; Schwarts, K.J.; Stevenson, G.W.; Zhang, K. Diseases of swine. First edition. Publisher: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2019.

- Nan, Y.; Wu, C.; Gu, G.; Sun, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, E.M. Improved vaccine against PRRSV: Current progress and future perspective. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1635. [CrossRef]

- Renson, P.; Mahé, S.; Andraud, M.; Le Dimna, M.; Paboeuf, F.; Rose, N.; Bourry, O. Effect of vaccination route (intradermal vs. intramuscular) against porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome using a modified live vaccine on systemic and mucosal immune response and virus transmission in pigs. BMC Vet Res. 2024, 20(1), 5. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.A.; Jayaramaiah, U.; You, S.H.; Shin, E.G.; Song, S.M.; Ju, L.; Kang, S.J.; Hyun, B.H.; Lee, H.S. Molecular Characterization of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus in Korea from 2018 to 2022. Pathogens 2023, 12(6), 757. [CrossRef]

- Chae, C. Commercial PRRS modified-live virus vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9(2), 185. [CrossRef]

- Sanglard, L.P.; Hickmann, F.M.W.; Huang, Y.; Gray, K.A.; Linhares, D.C.L.; Dekkers, J.C.M.; Niederwerder, M.C.; Fernando, R.L.; Braccini Neto, J.; Serão, N.V.L. Genomics of response to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in purebred and crossbred sows: antibody response and performance following natural infection vs. vaccination. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 99(5), skab097. [CrossRef]

- Rowland, R.R.; Lunney, J.; Dekkers, J. Control of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) through genetic improvements in disease resistance and tolerance. Front. Genet. 2012, 3, 260. [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Trejo, C.M.; Luna-Nevárez, G.; Reyna-Granados, J.R.; Zamorano-Algandar, R.; Romo-Rubio, J.A.; Sánchez-Castro, M.A.; Enns, R.M.; Speidel, S.E.; Thomas, M.G.; Luna-Nevárez, P. Polymorphisms associated with the number of live-born piglets in sows. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pec 2020, 11(3), 828-847. [CrossRef]

- Sanglard, L.P.; Fernando, R.L.; Gray, K.A.; Linhares, D.C.L.; Dekkers, J.C.M.; Niederwerder, M.C.; Serão, N.V.L. Genetic analysis of antibody response to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome vaccination as an indicator trait for reproductive performance in commercial sows. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 1011. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, Z.; Luo, S.; Wu, J.; Zhou, L.; Liu, J. Genome-wide association analysis and genetic parameters for feed efficiency and related traits in Yorkshire and Duroc pigs. Animals (Basel) 2022, 12(15), 1902. [CrossRef]

- Luan, M.; Ruan, D.; Qiu, Y.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, S.; Yang, J.; Sun, Y.; Ma, F.; Wu, Z.; Yang, J.; Yang, M.; Zheng, E.; Cai, G.; Huang, S. Genome-wide association study for loin muscle area of commercial crossbred pigs. Anim. Biosci. 2023, 36(6), 861-868. [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Yang, M.; Quan, J.; Li, S.; Zhuang, Z.; Zhou, S.; Zheng, E.; Hong, L.; Li, Z.; Cai, G.; Huang, W.; Wu, Z.; Yang, J. Single-locus and multilocus genome-wide association studies for intramuscular fat in Duroc pigs. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 619. [CrossRef]

- Chang Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, X.; Wu, S.; Bao, W. A genome-wide association study of important reproduction traits in Large White pigs. Gene, 2022, 838, 146702. [CrossRef]

- Óvilo, C.; Trakooljul, N.; Núñez, Y.; Hadlich, F.; Murani, E.; Ayuso, M.; García-Contreras, C.; Vázquez-Gómez, M.; Rey, A.I.; García, F.; et al. SNP discovery and association study for growth, fatness and meat quality traits in Iberian crossbred pigs. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12(1), 16361. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Quan, J.; Ruan, D.; Qiu, Y.; Ding, R.; Xu, C.; Ye, Y.; Cai, G.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Identification of candidate genes for economically important carcass cutting in commercial pigs through GWAS. Animals (Basel), 2023, 13(20), 3243. [CrossRef]

- Boddicker, N.; Waide, E.H.; Rowland, R.R.; Lunney, J.K.; Garrick, D.J.; Reecy, M.; Dekkers, J.C. Evidence for a major QTL associated with host response to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus challenge. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90(6), 1733-1746. [CrossRef]

- Sanglard, L.P.; Huang, Y.; Gray, K.A.; Linhares, D.; Dekkers, J.; Niederwerder, M.C.; Fernando, R.L.; Serão, N. Further host-genomic characterization of total antibody response to PRRSV vaccination and its relationship with reproductive performance in commercial sows: Genome-wide haplotype and zygosity analyses. Gen. Sel. Evol. 2021, 53(1), 91. [CrossRef]

- Dunkelberger, J.R.; Serão, N.V.L.; Weng, Z.; Waide, E.H.; Niederwerder, M.C.; Kerrigan, M.A.; Lunney, J.K.; Rowland, R.R.R.; Dekkers, J.C.M. Genomic regions associated with host response to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome vaccination and coinfection in nursery pigs. BMC Genomics 2017, 18(1), 865. [CrossRef]

- Torricelli, M.; Fratto, A.; Ciullo, M.; Sebastiani, C.; Arcangeli, C.; Felici, A.; Giovannini, S.; Sarti, F.M.; Sensi, M.; Biagetti, M. Porcine reproductive and respiratory ryndrome (PRRS) and CD163 resistance polymorphic markers: What is the scenario in naturally infected pig livestock in central Italy?. Animals (Basel), 2023, 13(15), 2477.

- Walker, L.R.; Jobman, E.E.; Sutton, K.M.; Wittler, J.; Johnson, R.K.; Ciobanu, D.C. Genome-wide association analysis for porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus susceptibility traits in two genetic populations of pigs1. J Anim Sci. 2019, 97(8), 3253-3261. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, R.; Jiang, Y.; Yao, Z.,; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Yuan, X. The Association of an SNP in the EXOC4 gene and reproductive traits suggests its use as a breeding marker in pigs. Animals (Basel), 2021, 11(2), 521. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Shan, B.; Ni, C.; Feng, S.; Liu, W.; Wang, X.; Wu, H.; Zuofeng, Y.; et al. Optimized protocol for double vaccine immunization against classical swine fever and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome. BMC Vet Res. 2023, 19(1), 14. [CrossRef]

- Serão, N.V.; Kemp, R.A.; Mote, B.E.; Willson, P.; Harding, J.C.; Bishop, S.C.; Plastow, G.S.; Dekkers, J.C. Genetic and genomic basis of antibody response to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) in gilts and sows. Gen. Sel. Evol. 2016, 48(1), 51. [CrossRef]

- Serão, N.V.; Matika, O.; Kemp, R.A.; Harding, J.C.; Bishop, S.C.; Plastow, G.S.; Dekkers, J.C. Genetic analysis of reproductive traits and antibody response in a PRRS outbreak herd. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 92(7), 2905-2921. [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; de Bakker, P.I.; Daly, M.J.; Sham, P.C. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81(3), 559-575. [CrossRef]

- Weir, B.S. Forensics. Iin Handbook of Statistical Genetics. First Edition. D.J. Balding, M. Bishop, C. Cannings Eds. Publisher: John Wiley and Sons, LTD, New York, NY. 2001. Pp. 275.

- Falconer, D.S.; Mackay, T.F.C. Introduction to quantitative genetics. 4th Edition. Longman Scientific and Technical, New York, NY. 1996. [CrossRef]

- Montaner-Tarbes, S.; Del Portillo, H.A.; Montoya, M.; Fraile, L. Key gaps in the knowledge of the porcine respiratory and reproductive syndrome virus (PRRSV). Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 38.

- Ko, H.; Sammons, J.; Pasternak, J.A., Hamonic, G.; Starrak, G., MacPhee, D.J., Detmer, S.E., Plastow, G.S., Harding, J.C.S. Phenotypic effect of a single nucleotide polymorphism on SSC7 on fetal outcomes in PRRSV-2 infected gilts. Liv. Sci., 2022, 255, 104800. [CrossRef]

- Luna-Nevárez, G.; Kelly, A.C.; Camacho, L.E.; Limesand, S.W.; Reyna-Granados, J.R.; Luna-Nevárez, P. Discovery and validation of candidate SNP markers associated to heat stress response in pregnant ewes managed inside a climate-controlled chamber. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2020, 52, 3457–3466. [CrossRef]

- Luna-Nevárez, G.; Pendleton, A.L.; Luna-Ramirez, R.I.; Limesand, S.W.; Reyna-Granados, J.R.; Luna-Nevárez, P. Genome-wide association study of a thermo-tolerance indicator in pregnant ewes exposed to an artificial heat-stressed environment. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 101, 103095. [CrossRef]

- Zamorano-Algandar, R.; Medrano, J.F.; Thomas, M.G;, Enns, R.M.; Speidel, S.E.; Sánchez-Castro, M.A.; Luna-Nevárez, G.; Leyva-Corona, J.C.; Luna-Nevárez, P. Genetic markers associated with milk production and thermotolerance in Holstein dairy cows managed in a heat-stressed environment. Biology (Basel), 2023, 12, 679. [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, E.K.; Baranowska, I.; Wade, C.M.; Salmon Hillbertz, N.H.; Zody, M.C.; Anderson, N.; Biagi, T.M.; Patterson, N.; Pielberg, G.R.; Kulbokas, E.J.; et al. Efficient mapping of Mendelian traits in dogs through genome-wide association. Nature Genetics 2007, 39(11), 1321-1328. [CrossRef]

- Visscher, P.M. Sizing up human height variation. Nature Genetics 2008, 40(5), 89-90. [CrossRef]

- Hickmann, F.M.W.; Braccini-Neto, J.; Kramer, L.M.; Huang, Y.; Gray, K.; Dekkers, J.C.M.; Sanglard, L.P.; Serão, N.V.L. Host genetics of response to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome in sows: Antibody response as an indicator trait for improved reproductive performance. Front. Gen. 2021, 12, 707873. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Q.; Chen, W.; Wang, C. Dynamic regulation of innate immunity by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews 2013, 24(6), 559-570. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, B.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, L.; Chu, C.; Guo, Q.; Wei, R.; Yin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. RNF144B inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory responses by binding TBK1. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2019, 106(6), 1303-1311. [CrossRef]

- Crow, M.K. Type I interferon in organ-targeted autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2010, 12(Suppl 1), S5. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Miller, L.C.; Sang, Y. Current status of vaccines for porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome: Interferon response, immunological overview, and future prospects. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12(6), 606. [CrossRef]

- Budronim, V.; Versteeg, G.A. Negative regulation of the innate immune response through proteasomal degradation and deubiquitination. Viruses 2021, 13(4), 584.

- Ke, H.; Yoo, D. The viral innate immune antagonism and an alternative vaccine design for PRRS virus. Vet. Microbiol. 2017, 209, 75-89. [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Wu, M.; Liu, Z. Dysregulation in IFN-γ signaling and response: the barricade to tumor immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1190333. [CrossRef]

- Cheon, H.; Wang, Y.; Wightman, S.M.; Jackson, M.W.; Stark, G.R. How cancer cells make and respond to interferon-I. Trends Cancer 2023, 9(1), 83-92. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, J.; Imanishi, E.; Nagata, S. Exposure of phosphatidylserine by Xk-related protein family members during apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289(44), 30257-30267. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Li, R.; Qiao, S.; Chen, X.; Xing, G.; Zhanga, G. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus utilizes porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus utilizes host cells. J. Virol. 2020, 94(17), e00709-20.

- Li, H.; Li, K.; Zhang, K.; Li, Y.; Gu, H.; Liu, H.; Yang, Z.; Cai, D. The circadian physiology: Implications in livestock health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22(4), 2111. [CrossRef]

- Mazzoccoli, G.; Vinciguerra, M.; Carbone, A.; Relógio, A. The circadian clock, the immune system, and viral infections: The intricate relationship between biological time and host‒virus interaction. Pathogens 2020, 9(2), 83.

- Nguyen, K.D.; Fentress, S.; Qiu, Y.; Yun, K.; Cox, J.S.; Chawla, A. Circadian gene Bmal1 regulates diurnal oscillations of Ly6C(hi) inflammatory monocytes. Science 2013, 341(6153), 1483-1488.

- Fairbairn, L.; Kapetanovic, R;, Beraldi, D.; Sester, D.P.; Tuggle, C.K.; Archibald, A.L.; Hume, D.A. Comparative analysis of monocyte subsets in the pig. J. Immunol. 2013, 190(12), 6389-6396. [CrossRef]

| SNP ID 1 | Variant 2 | BTA 3 | Position 4 | Gene 5 | Alleles 6 | Variance 7 | p-Value 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs81358818 | Intronic | 2 | 49’336890 | BMAL1 | C/T | 2.82 | 1.77x10-8 |

| rs705026086 | Intronic | 18 | 31’655298 | FOXP2 | A/G | 2.79 | 2.25x10-8 |

| rs343308278 | 3’UTR | 13 | 71’562221 | GP9 | C/T | 2.19 | 1.12x10-6 |

| rs80896559 | Intronic | 4 | 70’291983 | XKR9 | A/G | 2.16 | 1.40x10-6 |

| rs80844350 | Intronic | 4 | 42’489363 | CPQ | A/G | 2.15 | 1.46x10-6 |

| rs331531082 | Intergenic | 18 | 32’235004 | -------- | C/T | 2.12 | 1.81x10-6 |

| rs80969120 | Intergenic | 4 | 70’092569 | -------- | C/T | 2.06 | 2.67x10-6 |

| rs80904326 | Intronic | 7 | 14’901075 | RNF144B | A/G | 1.98 | 4.36x10-6 |

| rs707607708 | Intronic | 3 | 3’156750 | SDK1 | C/T | 1.96 | 4.73x10-6 |

| rs3475576322 | Non-coding | 12 | 19’663911 | -------- | C/G | 1.85 | 5.63x10-6 |

| SNP ID 1 | Gene 2 | Allele Frequency 3 | HWE Test 4 | HWE p-Value 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | G | ||||

| rs80904326 | RNF144B | 0.69 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.79 |

| rs80896559 | XKR9 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 1.15 | 0.46 |

| rs80844350 | CPQ | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.86 | 0.58 |

| rs705026086 | FOXP2 | 0.23 | 0.77 | 0.47 | 0.71 |

| C | T | ||||

| rs81358818 | BMAL1 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.75 | 0.64 |

| rs343308278 | GP9 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 24.19 | < 0.01 |

| rs707607708 | SDK1 | 0.97 | 0.03 | 18.73 | < 0.01 |

| SNP ID 1 | Gene 2 | Least-Square Means by Genotype ± SE 3 | p-Value 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | AG | GG | |||

| rs80904326 | RNF144B | 1.90 ± 0.03a | 2.36 ± 0.10b | 2.51 ± 0.09b | 0.0009 |

| rs80896559 | XKR9 | 2.24 ± 0.11a | 1.88 ± 0.07b | 1.76 ± 0.08b | 0.0065 |

| rs80844350 | CPQ | 1.96 ± 0.12a | 1.79 ± 0.10a | 1.68 ± 0.14a | 0.4238 |

| rs705026086 | FOXP2B | 1.74 ± 0.06a | 2.01 ± 0.06a | 2.18 ± 0.08a | 0.1875 |

| CC | CT | TT | |||

| rs81358818 | BMAL1 | 2.31 ± 0.08a | 2.14 ± 0.06b | 1.87 ± 0.07c | <0.0001 |

| SNP ID 1 | Gene 2 | Allele Substitution Effects | Fixed Estimates Effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F. Allele 3 | p-Value 4 | Estimate ± SE 5 | p-Value 6 | AddE 7 | DomE 8 | ||

| rs80904326 | RNF144B | G | <0.0010 | 0.301 ± 0.016 | <0.0010 | 0.305 | 0.155 |

| rs80896559 | XKR9 | A | <0.0100 | 0.230 ± 0.010 | <0.0080 | 0.240 | 0.120 |

| rs81358818 | BMAL1 | C | <0.0001 | 0.216 ± 0.012 | <0.0001 | 0.220 | 0.050 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).