Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Method

3.1. Problem Formulation

- represents the i-th object’s localization (e.g. the local center of coordinates of the bounding box).

- represents the i-th object’s dimensions (e.g. the dimension of the bounding box).

- is the semantic label assigned to the i-th object, being the set of all possible semantic classes (e.g. table, chair, vase, etc.).

- is a list of possible additional properties describing the i-th object.

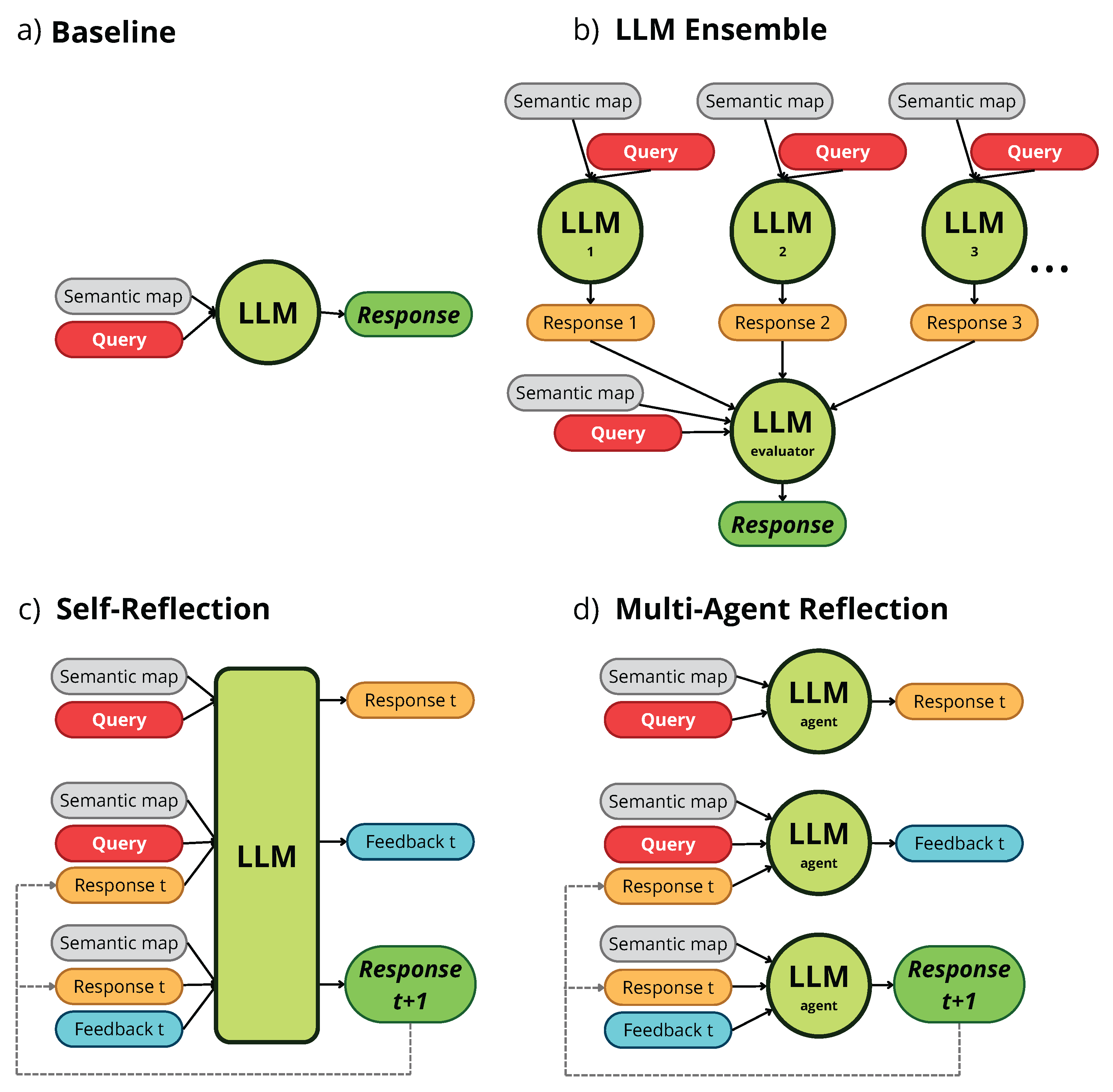

3.2. Baseline

- Inferred query: a short interpretation of the query.

- Query achievable: whether or not the user query is achievable using the objects in the semantic map.

- Explanation: brief explanation of what are the most relevant objects, and how they can be used to achieve the task.

3.3. Self-Reflection

3.4. Multi-Agent Reflection

3.5. LLM Ensemble

3.6. Agentic Workflows Evaluation Context

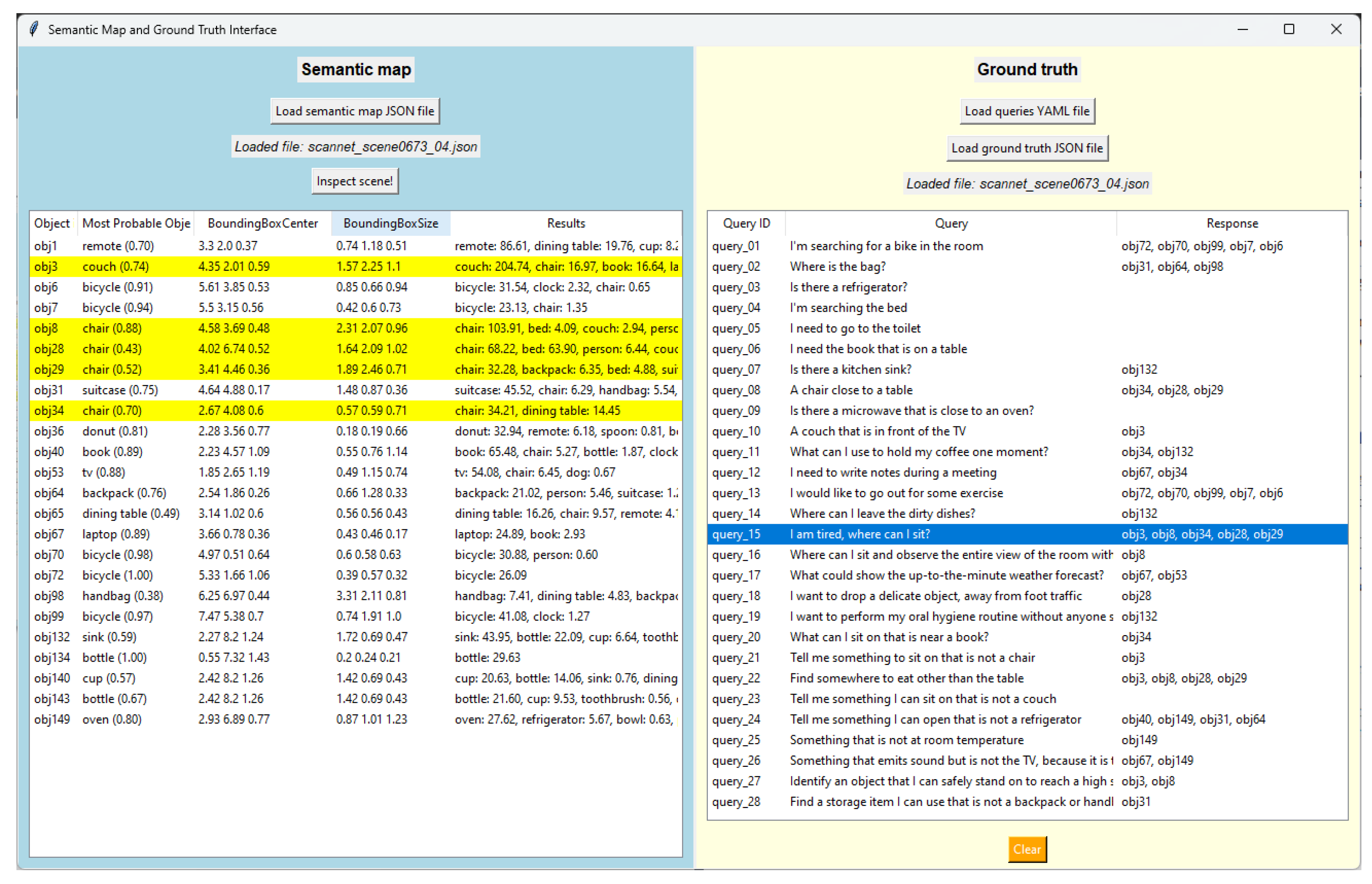

4. Dataset Description

- is a query from the set of queries with size m.

- is a map in JSON format from the set of semantic maps with size n.

- is the response to query when evaluated on map , being the set of all objects in said map.

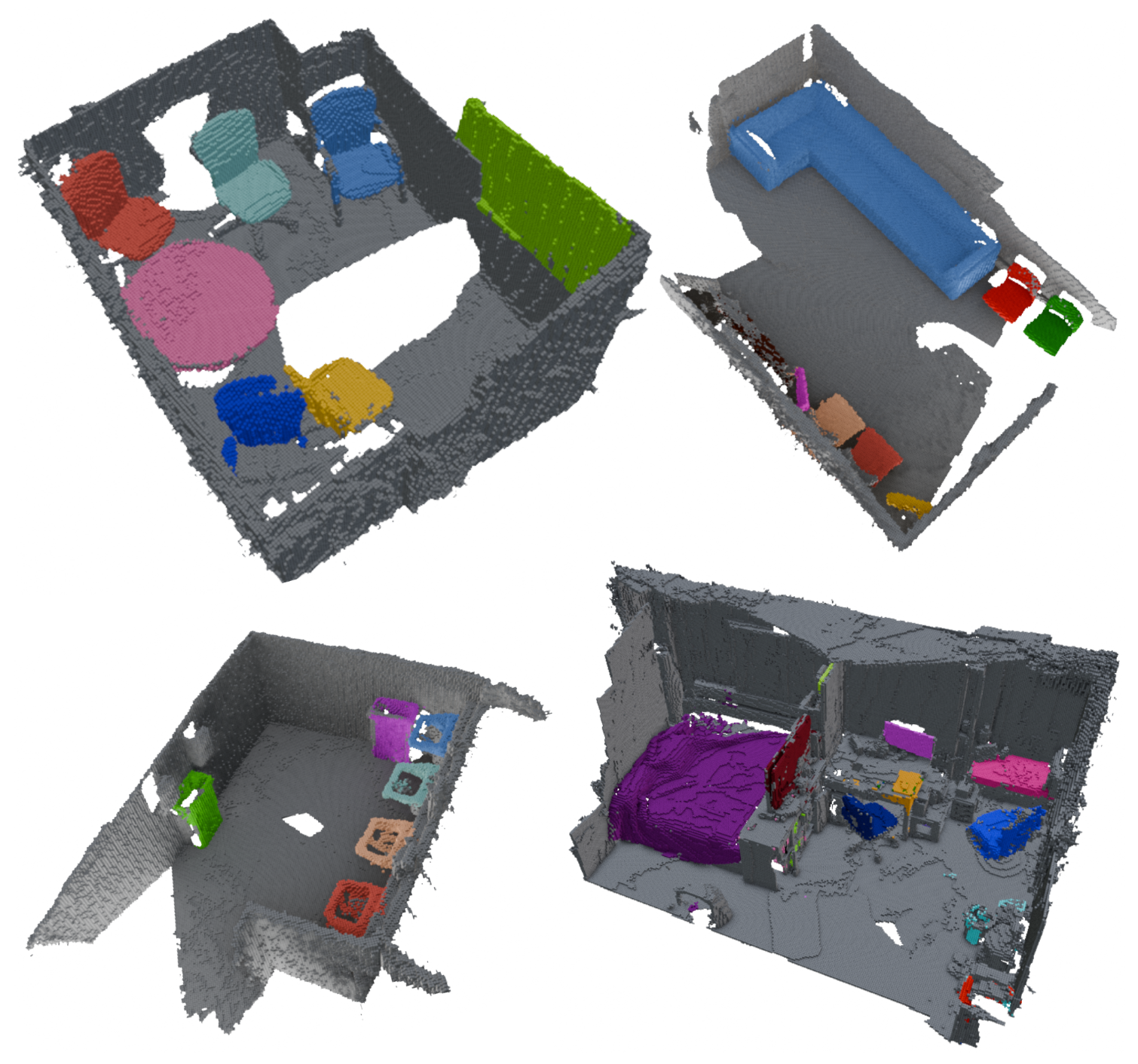

4.1. Generating the Semantic Maps

4.2. Datasets Description

4.3. Queries Design

- Descriptive queries prompt the system to identify objects based on their category, some characteristics within a scene, or their spatial location. An example of this query type is query_09 which states "Is there a microwave that is close to an oven?". The evaluation of this type of queries provides an approximation of how the system will behave in simple tasks.

- Affordance queries evaluate the system’s ability to infer the functionality and uses of objects in specific contexts. In general, they ask for objects to perform an action or to fill a need. An example of this is query_15, "I am tired, where can I sit?". These queries assess application of real-world information in our context by LLMs.

- Negation queries test the model’s ability to find a solution excluding specific objects or objects with specific features. An example is query_23, "Tell me something I can sit on that is not a couch". These queries are especially interesting for the evaluation of workflows, as LLMs tend to perform poorly when inputted with prompts containing negated instructions [53].

4.4. Annotating Responses

5. Experimental Setup

5.1. Implementation Details

5.2. Metrics

- Top-1 checks if the first object in the system’s response, , appears in the ground truth, , or if both lists are empty. It is defined as:

- Top-2 checks if any of the first two objects from the system response, and , belong to the ground truth, . It is defined as:

- Top-3, similar to Top-2, checks whether some of the first three objects in the system response belong to the ground truth:

- Top-Any measures whether any of the objects in the system’s response appear in the ground truth. It is defined as:

6. Evaluation

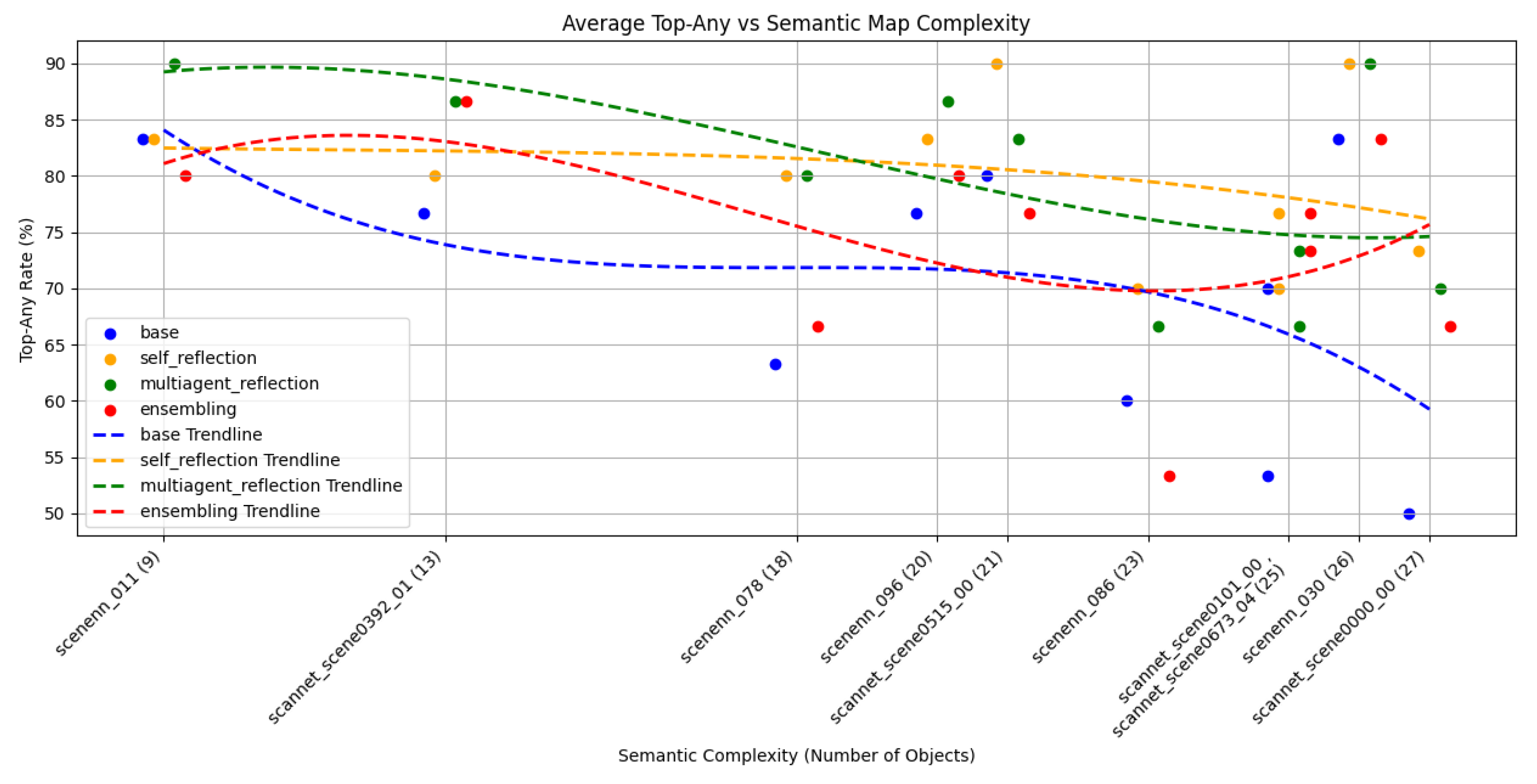

6.1. Workflows Comparison

6.2. Impact of Semantic Map Complexity

6.3. Errors Qualitative Analysis

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| GUI | Graphical User Interface |

| JSON | Javascript Object Notation |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| LVLM | Large Vision-Language Model |

| OWL | Web Ontology Language |

| PDDL | Planning Domain Definition Language |

| RDF | Resource Description Framework |

| RGB-D | Red Green Blue - Depth |

| SfM | Structure from Motion |

| SLAM | Simultaneous Localization and Mapping |

| SPARQL | SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language |

| SWRL | Semantic Web Rule Language |

Appendix A

| Type | Difficulty | Query ID | Query |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive | Easy | query_01 | I’m searching for a bike in the room |

| query_02 | Where is the bag? | ||

| query_03 | Is there a refrigerator? | ||

| query_04 | I’m searching the bed | ||

| query_05 | I need to go to the toilet | ||

| Difficult | query_06 | I need the book that is on a table | |

| query_07 | Is there a kitchen sink? | ||

| query_08 | A chair close to a table | ||

| query_09 | Is there a microwave that is close to an oven? | ||

| query_10 | A couch that is in front of the TV | ||

| Affordance | Easy | query_11 | What can I use to hold my coffee one moment? |

| query_12 | I need to write notes during a meeting | ||

| query_13 | I would like to go out for some exercise | ||

| query_14 | Where can I leave the dirty dishes? | ||

| query_15 | I am tired, where can I sit? | ||

| Difficult | query_16 | Where can I sit and observe the entire view of the room without obstruction? | |

| query_17 | What could show the up-to-the-minute weather forecast? | ||

| query_18 | I want to drop a delicate object, away from foot traffic | ||

| query_19 | I want to perform my oral hygiene routine without anyone seeing me | ||

| query_20 | What can I sit on that is near a book? | ||

| Negative | Easy | query_21 | Tell me something to sit on that is not a chair |

| query_22 | Find somewhere to eat other than the table | ||

| query_23 | Tell me something I can sit on that is not a couch | ||

| query_24 | Tell me something I can open that is not a refrigerator | ||

| query_25 | Something that is not at room temperature | ||

| Difficult | query_26 | Something that emits sound but is not the TV, because it is turned off | |

| query_27 | Identify an object that I can safely stand on to reach a high shelf, which is not a chair | ||

| query_28 | Find a storage item I can use that is not a backpack or handbag | ||

| query_29 | Locate an item that provides light but isn’t a table lamp | ||

| query_30 | Something where I can deposit liquids, that doesn’t close? |

References

- Rubio, F.; Valero, F.; Llopis-Albert, C. A review of mobile robots: Concepts, methods, theoretical framework, and applications. International Journal of Advanced Robotic Systems 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, C.; Saffiotti, A.; Coradeschi, S.; Buschka, P.; Fernandez-Madrigal, J.A.; González, J. Multi-hierarchical semantic maps for mobile robotics. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems. IEEE, 2005, pp. 2278–2283.

- 3D Nüchter, A.; Wulf, O.; Lingemann, K.; Hertzberg, J.; Wagner, B.; Surmann, H. 3D mapping with semantic knowledge. In Proceedings of the RoboCup 2005: Robot Soccer World Cup IX 9. Springer, 2006, pp. 335–346.with semantic knowledge.

- Ranganathan, A.; Dellaert, F. Semantic Modeling of Places using Objects. In Proceedings of the Robotics: Science and Systems, 2007, Vol. 3, pp. 27–30.

- Meger, D.; Forssén, P.E.; Lai, K.; Helmer, S.; McCann, S.; Southey, T.; Baumann, M.; Little, J.J.; Lowe, D.G. Curious george: An attentive semantic robot. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2008, 56, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uschold, M.; Gruninger, M. Ontologies: Principles, methods and applications. The knowledge engineering review 1996, 11, 93–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassila, O. Resource Description Framework (RDF) Model and Syntax 1997.

- McGuinness, D.L. OWL Web Ontology Language Overview. W3C Member Submission 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Prud’hommeaux, E.; Seaborne, A. SPARQL Query Language for RDF. https://www.w3.org/TR/rdf-sparql-query/, 2008. W3C Recommendation.

- Horrocks, I.; Patel-Schneider, P.F.; Boley, H.; Tabet, S.; Grosof, B.; Dean, M.; et al. SWRL: A semantic web rule language combining OWL and RuleML. W3C Member submission 2004, 21, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, T.; Hariprasad, V.; Shuttleworth, R.S.; Kumar, N.; Lozano-Pérez, T.; Kaelbling, L.P. PDDL Planning with Pretrained Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2022 Foundation Models for Decision Making Workshop, 2022.

- Vaswani, A. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training 2018.

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding, 2019, [arXiv:cs.CL/1810.04805].

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I.; et al. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog 2019, 1, 9. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. GPT-4 Technical Report. https://openai.com/research/gpt-4, 2023. Accessed: 2024-12-05.

- Gu, Q.; Kuwajerwala, A.; Morin, S.; Jatavallabhula, K.M.; Sen, B.; Agarwal, A.; Rivera, C.; Paul, W.; Ellis, K.; Chellappa, R.; et al. ConceptGraphs: Open-Vocabulary 3D Scene Graphs for Perception and Planning, 2023, [arXiv:cs.RO/2309.16650].

- Rana, K.; Haviland, J.; Garg, S.; Abou-Chakra, J.; Reid, I.; Suenderhauf, N. SayPlan: Grounding Large Language Models using 3D Scene Graphs for Scalable Robot Task Planning, 2023, [arXiv:cs.RO/2307.06135].

- Gao, T.; Fisch, A.; Chen, D. Making Pre-trained Language Models Better Few-shot Learners, 2021, [arXiv:cs.CL/2012.15723].

- Ji, Z.; Lee, N.; Frieske, R.; Yu, T.; Su, D.; Xu, Y.; Ishii, E.; Bang, Y.J.; Madotto, A.; Fung, P. Survey of hallucination in natural language generation. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 55, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Galley, M.; He, P.; Cheng, H.; Xie, Y.; Hu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Liden, L.; Yu, Z.; Chen, W.; et al. Check Your Facts and Try Again: Improving Large Language Models with External Knowledge and Automated Feedback, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CL/2302.12813].

- Patil, S.G.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X.; Gonzalez, J.E. Gorilla: Large Language Model Connected with Massive APIs, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CL/2305.15334].

- Schick, T.; Dwivedi-Yu, J.; Dessì, R.; Raileanu, R.; Lomeli, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Cancedda, N.; Scialom, T. Toolformer: Language Models Can Teach Themselves to Use Tools, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CL/2302.04761].

- Madaan, A.; Tandon, N.; Gupta, P.; Hallinan, S.; Gao, L.; Wiegreffe, S.; Alon, U.; Dziri, N.; Prabhumoye, S.; Yang, Y.; et al. Self-Refine: Iterative Refinement with Self-Feedback, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CL/2303.17651].

- Shinn, N.; Cassano, F.; Berman, E.; Gopinath, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Yao, S. Reflexion: Language Agents with Verbal Reinforcement Learning, 2023, [arXiv:cs.AI/2303.11366].

- Dai, A.; Chang, A.X.; Savva, M.; Halber, M.; Funkhouser, T.; Nießner, M. ScanNet: Richly-annotated 3D Reconstructions of Indoor Scenes. In Proceedings of the Proc. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), IEEE, 2017.

- Hua, B.S.; Pham, Q.H.; Nguyen, D.T.; Tran, M.K.; Yu, L.F.; Yeung, S.K. SceneNN: A Scene Meshes Dataset with aNNotations. In Proceedings of the 2016 Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), 2016, pp. 92–101. [CrossRef]

- Matez-Bandera, J.L.; Ojeda, P.; Monroy, J.; Gonzalez-Jimenez, J.; Ruiz-Sarmiento, J.R. Voxeland: Probabilistic Instance-Aware Semantic Mapping with Evidence-based Uncertainty Quantification, 2024, [arXiv:cs.RO/2411.08727].

- Galindo, C.; Fernandez-Madrigal, J.A.; Gonzalez, J. Multihierarchical Interactive Task Planning: Application to Mobile Robotics. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part B (Cybernetics) 2008, 38, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Sarmiento, J.R.; Galindo, C.; Gonzalez-Jimenez, J. Building multiversal semantic maps for mobile robot operation. Knowledge-Based Systems 2017, 119, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sünderhauf, N.; Pham, T.T.; Latif, Y.; Milford, M.; Reid, I. Meaningful Maps With Object-Oriented Semantic Mapping, 2017, [arXiv:cs.RO/1609.07849].

- McCormac, J.; Handa, A.; Davison, A.; Leutenegger, S. SemanticFusion: Dense 3D Semantic Mapping with Convolutional Neural Networks, 2016, [1609.05130]. [CrossRef]

- Rünz, M.; Buffier, M.; Agapito, L. MaskFusion: Real-Time Recognition, Tracking and Reconstruction of Multiple Moving Objects, 2018, [1804.09194]. [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Chatrath, V.; Yang, J.; Servos, J.; Schoellig, A.P.; Waslander, S.L. POCD: Probabilistic Object-Level Change Detection and Volumetric Mapping in Semi-Static Scenes, 2022, [2205.01202]. [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Chatrath, V.; Servos, J.; Mavrinac, A.; Burgard, W.; Waslander, S.L.; Schoellig, A.P. POV-SLAM: Probabilistic Object-Aware Variational SLAM in Semi-Static Environments, 2023, [2307.00488].

- Ren, S. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1506.01497 2015.

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 2961–2969. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, M.; Brohan, A.; Brown, N.; Chebotar, Y.; Cortes, O.; David, B.; Finn, C.; Fu, C.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Hausman, K.; et al. Do As I Can, Not As I Say: Grounding Language in Robotic Affordances, 2022, [arXiv:cs.RO/2204.01691].

- Liu, B.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, S.; Biswas, J.; Stone, P. LLM+P: Empowering Large Language Models with Optimal Planning Proficiency, 2023, [arXiv:cs.AI/2304.11477].

- Huang, W.; Xia, F.; Xiao, T.; Chan, H.; Liang, J.; Florence, P.; Zeng, A.; Tompson, J.; Mordatch, I.; Chebotar, Y.; et al. Inner Monologue: Embodied Reasoning through Planning with Language Models, 2022, [arXiv:cs.RO/2207.05608].

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.L.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback, 2022.

- Madaan, A.; Tandon, N.; Rajagopal, D.; Clark, P.; Yang, Y.; Hovy, E. Think about it! Improving defeasible reasoning by first modeling the question scenario. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Moens, M.F.; Huang, X.; Specia, L.; Yih, S.W.t., Eds., Online and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 2021; pp. 6291–6310. [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Ichter, B.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CL/2201.11903].

- Chang, K.; Xu, S.; Wang, C.; Luo, Y.; Xiao, T.; Zhu, J. Efficient Prompting Methods for Large Language Models: A Survey, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2404.01077].

- Yang, K.; Tian, Y.; Peng, N.; Klein, D. Re3: Generating Longer Stories With Recursive Reprompting and Revision, 2022, [arXiv:cs.CL/2210.06774].

- Qian, C.; Liu, W.; Liu, H.; Chen, N.; Dang, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, C.; Chen, W.; Su, Y.; Cong, X.; et al. ChatDev: Communicative Agents for Software Development, 2024, [arXiv:cs.SE/2307.07924].

- Hong, S.; Zhuge, M.; Chen, J.; Zheng, X.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Yau, S.K.S.; Lin, Z.; et al. MetaGPT: Meta Programming for A Multi-Agent Collaborative Framework, 2024, [arXiv:cs.AI/2308.00352].

- Wu, Q.; Bansal, G.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, B.; Zhu, E.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; et al. AutoGen: Enabling Next-Gen LLM Applications via Multi-Agent Conversation, 2023, [arXiv:cs.AI/2308.08155].

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners, 2020, [arXiv:cs.CL/2005.14165].

- Bender, E.M.; Gebru, T.; McMillan-Major, A.; Shmitchell, S. On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, New York, NY, USA, 2021; FAccT ’21, p. 610–623. [CrossRef]

- Matez-Bandera, J.L.; Monroy, J.; Gonzalez-Jimenez, J. Sigma-FP: Robot Mapping of 3D Floor Plans With an RGB-D Camera Under Uncertainty. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2022, 7, 12539–12546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morilla-Cabello, D.; Mur-Labadia, L.; Martinez-Cantin, R.; Montijano, E. Robust Fusion for Bayesian Semantic Mapping. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2023, pp. 76–81. [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Ye, S.; Seo, M. Can Large Language Models Truly Understand Prompts? A Case Study with Negated Prompts, 2022, [arXiv:cs.CL/2209.12711].

- Team, G.; Anil, R.; Borgeaud, S.; Alayrac, J.B.; Yu, J.; Soricut, R.; Schalkwyk, J.; Dai, A.M.; Hauth, A.; Millican, K.; et al. Gemini: a family of highly capable multimodal models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.11805 2023.

- Liu, N.F.; Lin, K.; Hewitt, J.; Paranjape, A.; Bevilacqua, M.; Petroni, F.; Liang, P. Lost in the Middle: How Language Models Use Long Contexts, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CL/2307.03172].

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 |

| Method | Top-1 | Top-2 | Top-3 | Top-Any |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | 66.60 | 68.67 | 69.33 | 69.67 |

| LLM Ensemble | 0.00 | +2.67 | +4.00 | +4.67 |

| Multi-Agent Reflection | +8.33 | +8.33 | +9.00 | +9.67 |

| Self-Reflection | +7.67 | +8.33 | +8.67 | +10.00 |

| Dataset | Agentic Workflow | Query Type | Top-1 | Top-2 | Top-3 | Top-Any |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ScanNet [26] | Base | Descriptive | 78.00 | 82.00 | 84.00 | 84.00 |

| Affordance | 52.00 | 58.00 | 60.00 | 60.00 | ||

| Negation | 52.00 | 54.00 | 54.00 | 54.00 | ||

| Average | 60.67 | 64.67 | 66.00 | 66.00 | ||

| LLM Ensemble | Descriptive | 0.00 | +2.00 | 0.00 | +2.00 | |

| Affordance | +8.00 | +10.00 | +18.00 | +20.00 | ||

| Negation | −4.00 | +6.00 | +8.00 | +8.00 | ||

| Average | +1.33 | +6.00 | +8.67 | +10.00 | ||

| Multi-Agent Reflection | Descriptive | +4.00 | +2.00 | +2.00 | +2.00 | |

| Affordance | +8.00 | +8.00 | +10.00 | +10.00 | ||

| Negation | +16.00 | +16.00 | +18.00 | +18.00 | ||

| Average | +9.33 | +8.67 | +10.00 | +10.00 | ||

| Self-Reflection | Descriptive | +8.00 | +6.00 | +4.00 | +4.00 | |

| Affordance | +10.00 | +8.00 | +12.00 | +14.00 | ||

| Negation | +14.00 | +18.00 | +18.00 | +18.00 | ||

| Average | +10.67 | +10.67 | +11.33 | +12.00 | ||

| SceneNN [27] | Base | Descriptive | 86.00 | 86.00 | 86.00 | 86.00 |

| Affordance | 72.00 | 76.00 | 76.00 | 78.00 | ||

| Negation | 56.00 | 56.00 | 56.00 | 56.00 | ||

| Average | 71.33 | 72.67 | 72.67 | 73.33 | ||

| LLM Ensemble | Descriptive | −4.00 | −4.00 | −4.00 | −2.00 | |

| Affordance | −6.00 | −8.00 | −8.00 | −10.00 | ||

| Negation | +6.00 | +10.00 | +10.00 | +10.00 | ||

| Average | −1.33 | −0.67 | −0.67 | −0.67 | ||

| Multi-Agent Reflection | Descriptive | +6.00 | +6.00 | +6.00 | +6.00 | |

| Affordance | +2.00 | +2.00 | +2.00 | +4.00 | ||

| Negation | +14.00 | +16.00 | +16.00 | +18.00 | ||

| Average | +7.33 | +8.00 | +8.00 | +9.33 | ||

| Self-Reflection | Descriptive | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Affordance | +2.00 | +2.00 | +2.00 | +8.00 | ||

| Negation | +12.00 | +16.00 | +16.00 | +16.00 | ||

| Average | +4.67 | +6.00 | +6.00 | +8.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).