1. Introduction

Palm oil serves as an essential commodity for the world since it can be used as a raw material for various essential products such as cooking oil, food, and cosmetics (M. H. Sitepu et al., 2020). Concurrently, with the extensive search for clean and renewable sources of energy to replace the dependency on fossil fuels, palm oil has also been found to be an excellent source for the development of biofuels such as biodiesel and biogas (Kaniapan et al., 2021). The diversified use of palm oil simultaneously increases the demand for its production globally. Despite this, the diversification could also, at the same time, be a double-edged sword, as more land has to be cleared for the palm oil industry to cater to global needs. Thus, attention has been shifted toward searching for an alternative source of biofuel derived from non-edible biomass, such as organic waste.

Palm oil mill effluents (POME) are the viscous liquid wastewater generated from oil extraction processes such as sterilization and fruit washing in palm oil refineries (Kadir et al., 2020). POME comprises 95–97% water and 3-5% palm acid oil (PAO) (Market, 2020). For every 1 tonne of rough palm oil made, an immense 5-7.5 tonne of water is required. Over 50% of the water used in palm oil refineries is wastewater (Singh et al., 1999). Raw POME generally contains a high concentration of organic matter, a high amount of total solids, oil, and grease, and high chemical oxygen demand (COD) and biological oxygen demand (BOD). Although POME is considered a non-toxic waste product, the discharge of it without sufficient treatment into the water bodies could cause severe environmental pollution (Lam & Lee, 2011). For instance, methane gas production due to anaerobic processes in POME ponds contributes to increased greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. An average of 12.36 kg of methane gas is estimated to be released for every tonne of POME treated (Yacob et al., 2005).

To mitigate this problem, several treatments have been proposed, which include coagulation-flocculation (Zahrim et al., 2014), anaerobic digestion (Islam et al., 2017), and photo-catalytic treatment (Alhaji et al., 2016). However, these treatment methods are often associated with high costs and extensive use of chemicals. Thus, an eco-friendly and cost-effective way of disposal aligned with sustainability and a lower overall cost of treatment is desirable (Iwuagwu & Ugwuanyi, 2014). Bioremediation is an environmentally friendly approach that involves the use of microbes to clean up the polluted environment (Iwamoto & Nasu, 2001). These microbes are selected based on their ability to detoxify and degrade specific environmental contaminants. Various oleaginous microorganisms like yeast, algae, mold, and bacteria are reported to be able to utilize waste such as POME and accumulate lipid (Islam et al., 2018) in the form of single-celled oil (SCO). It is possible because POME is rich in minerals and vitamins, which could help stimulate cell growth (Habib et al., 1997). Recycling waste to culture microorganisms for lipid production is definitely more advantageous, as it could recover value-added products at the end of the treatment process by adopting a zero-waste discharge concept.

Yeast is a preferable microorganism to produce microbial oil than filamentous fungi, microalgae, or bacteria. Compared to microalgae, yeast does not require land to grow, has a higher growth rate, and can utilize a broader range of carbon sources. Regarding lipid production, the lipid content harvested from the yeast is higher, and the process of scaling up is also easier (Li et al., 2008). Moreover, yeasts also tolerate living in extreme conditions, such as in an environment with low pH. This feature could be used to control bacterial contamination, as most bacterial growth is likely to be inhibited in low pH conditions (Juanssilfero et al., 2018a). Yeasts capable of accumulating lipids more than 20% of their dry cell weight (DCW) are classified as oleaginous (Ratledge & Wynn, 2002). Presently, several oleaginous yeasts such as Yarrowia, Candida, Rhodotorula, Rhodosporidium, Cryptococcus, Trichosporon, and Lipomyces have been extensively studied for lipid accumulation (Islam et al., 2018).

Meyerozyma guillermondii is another oleaginous yeast with notable potential for lipid production due to its ability to utilize diverse carbon sources, including lignocellulosic hydrolysates, waste materials, and other renewable feedstocks (Yan et al., 2021). This yeast is recognized for its relatively fast growth rate and metabolic versatility, which make it an attractive candidate for biotechnological applications. In addition, M. guillermondii demonstrates adaptability to various environmental conditions and resistance to inhibitors typically found in industrial processes. Therefore, M. guillermondii is promising to be used for industrial-scale lipid production.

As far as the research is concerned, there is no comprehensive report yet on using palm acid oil (PAO) by any strain of M. guillermondii for single-cell oil production. In this study, M. guillermondii strain is used as a platform to evaluate the cell growth and lipid production in nutrient-rich media supplemented with palm acid oil as the sole carbon substrate. The effect of various concentrations of palm acid oil on cell growth and subsequent lipid production is also investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Yeast Strain and Growth Condition

Meyerozyma guillermondii from a private collection (No. PK01) at Kobe University was used in the study. The yeast strain was preserved in 20% (w/w) glycerol and revived by streaking on a potato dextrose agar (PDA) plate. For short-term storage, the yeast strain was grown on a yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) agar plate and maintained at 4 °C. The composition of YPD agar was yeast extract 10 g/L, peptone 20 g/L, glucose 20 g/L, and agar 15 g/L. The culture was subcultured regularly to a new plate at least once a month to maintain its freshness. A single colony of the strain from YPD agar was inoculated into 12 mL of YPD broth in a 100 mL Erlenmeyer flask. The composition of YPD broth was yeast extract 10 g/L, peptone 20 g/L, and glucose 20 g/L. The seed cultures were incubated in an orbital shaker incubator (BioShaker BR-43FH MR, Taitec Corp., Tokyo, Japan) at 29 °C, 190 rpm for 18 h-24 h before inoculation. Shake flask fermentation was conducted in a 100-mL Erlenmeyer flask with 12 mL of working volume. The seed volume of the inoculum was adjusted to an initial optical density (OD600nm) of 16-18 to obtain an appropriate amount of active cells for higher lipid production. Afterward, the seed culture was transferred to each YP medium containing different concentrations of PAO, as shown in Table 1. The cultivation mode is by batch, and the fermentation is terminated after 4 days (96 hours).

2.2. Media Preparation

The fermentation medium used in this study was yeast extract-peptone (YP) broth supplemented with PAO, which varied from 1% to 10%. The fermentation media comprised yeast extract 10 g/L, peptone 20 g/L, and various concentrations of PAO, as shown in the table below. Moreover, YP without any supplementary PAO was prepared as the negative control and composed of only 10 g/L yeast extract and 20 g/L peptone.

2.3. Carbon Sources

Palm acid oil (PAO) is a semi-solid waste derived from POME. The PAO was obtained from PT. Agricinal Palm Oil Mills (Bengkulu, Indonesia). PAO was heated at 70 °C overnight to obtain the liquid form prior to adding the medium.

2.4. Determination of Total Lipid Content by Gravimetric Analysis

Gravimetric analysis was used to quantify the total lipid produced in the harvested cells based on the modified Folch method (Folch et al., 1957). The triplicate of freeze-dried samples was transferred to 2.0 mL of polypropylene microvial with an O-ring-sealed cap containing 0.5 mm of Zirconia beads and 1.5 mL of Folch solvent (2:1 CHCl3: MeOH, v/v). Cells were pulverized using a Shake Master Neo ver.1.0 (BMS-M10N21, BMS, Tokyo, Japan) at 1500 rpm for 15 min. Afterward, the cells were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 5 min, the supernatant was removed by pipetting, and the remaining pellets were washed with 1.5 ml of deionized water. The cells were then re-pulverized for the second time, centrifuged, and the water was removed from the pellet. The lipid content was the weight difference and was expressed as the percentage of cell dry weight.

2.5. Determination and Quantification of Total Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAME)

The transesterification was conducted by following the protocol from the fatty acid methylation kit (Nacalai Tesque, Inc. Japan). The extracted FAME (light phase) was analyzed using a gas chromatography-mass spectrometer (GC-MS) (Shimadzu). The GC-MS was equipped with a DB-23 capillary column 0.25 mm x 30 m (J&W Scientific). The carrier was helium gas with a 0.8 mL/min flow rate with 1:5 split ratios. The initial column temperature was 250 °C, increased 50 °C for 1 min, and then increased 25 °C/min to 190 °C and 5 °C/min to 235 °C for 4 min. The internal standard of C8:0 (caprylic acid) was included in each sample. FAME was calculated as the percentage of each fatty acid relative to the total number of fatty acids produced upon fermentation.

2.6. BODIPY Staining

BODIPY (493/505) is used as a dye to visualize the triacylglycerols (TAGs) in the cell. BOD-IPY has various advantages over the other staining methods. It can be uptake efficiently with minimal dye needed, and the lipid droplets can be easily spotted in bright green fluorescence (Govender et al., 2012). BODIPY stock solution was prepared by dissolving 10 mg of BODIPY powder with 1 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to make the stock concentration 10 g/L. During sampling, 100 µL of fermentation culture was withdrawn, pelleted, and washed with 0.9% (w/w) phosphate saline buffer (PBS). After washing, the pellet was suspended in 45 µL of 0.9% (w/w) PBS. Five µL of BODIPY stock solution was added and mixed well by pipetting. The cell suspension was kept in the dark for at least 1 hour. Fluorescence images of the BODIPY-stained cells were viewed and subsequently captured on a digital inverted fluorescence microscope (Keyence Biorevo BZ-9000, Keyence, Osaka, Japan).

2.7. Lipase Activity Assay

Lipase activities were measured from the supernatant separated after centrifugation using p-nitrophenyl-butyrate (pNPB) in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, at 37 °C. Hexane was used as a solvent to wash and remove the residual POME from the supernatant. The supernatants were washed twice before being used as a sample for lipase activity evaluation. One unit of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that releases 1 μmol of p-nitrophenol per minute.

2.8. Quantitative PCR

The RNA of each sample was isolated and purified by using NucleoSpin RNA. After purification, the total RNA was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm and 280 nm using Thermo Scientific Nanodrop One. After the concentration of RNA was obtained and the purity was confirmed, the RNA was used as the template for cDNA synthesis. The process involving cDNA generation from single-stranded RNA is known as reverse transcription. The reaction mixture for the reverse transcription step was prepared using ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix. The product was later amplified, and the concentration was measured using Thermo Scientific Nanodrop One. RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) is used to quantify gene expression. The qPCR was performed in Applied Biosystems StepOnePlusTM using SYBR Green RT-PCR Master Mix (Toyobo, Japan). Amplification was carried out in a 20 µL reaction mixture solution containing 10 µL of 2x KOD SYBR qPCR mix, 0.4 µL of 50x ROX reference dye (1:10 diluted), 5 µL of cDNA template (final concentration ≈ 12.5 ng/µL), 0.8 µL of each primer (forward+reverse), and 3.8 µL of RNA-free water. The PCR conditions were 98 °C for 5 min, followed by 60 cycles of 98 °C for 10 sec, 60 °C for 11 sec, and 68 °C for 30 sec. The specificity of each pair of primers was checked by melting curve analysis (98 °C for 1 min, 60 °C for 30 sec, and 98 °C for 30 sec). The gene expression data was analyzed using the 2-∆∆Ct method (Livak & Schmittgen, 2001).

3. Results

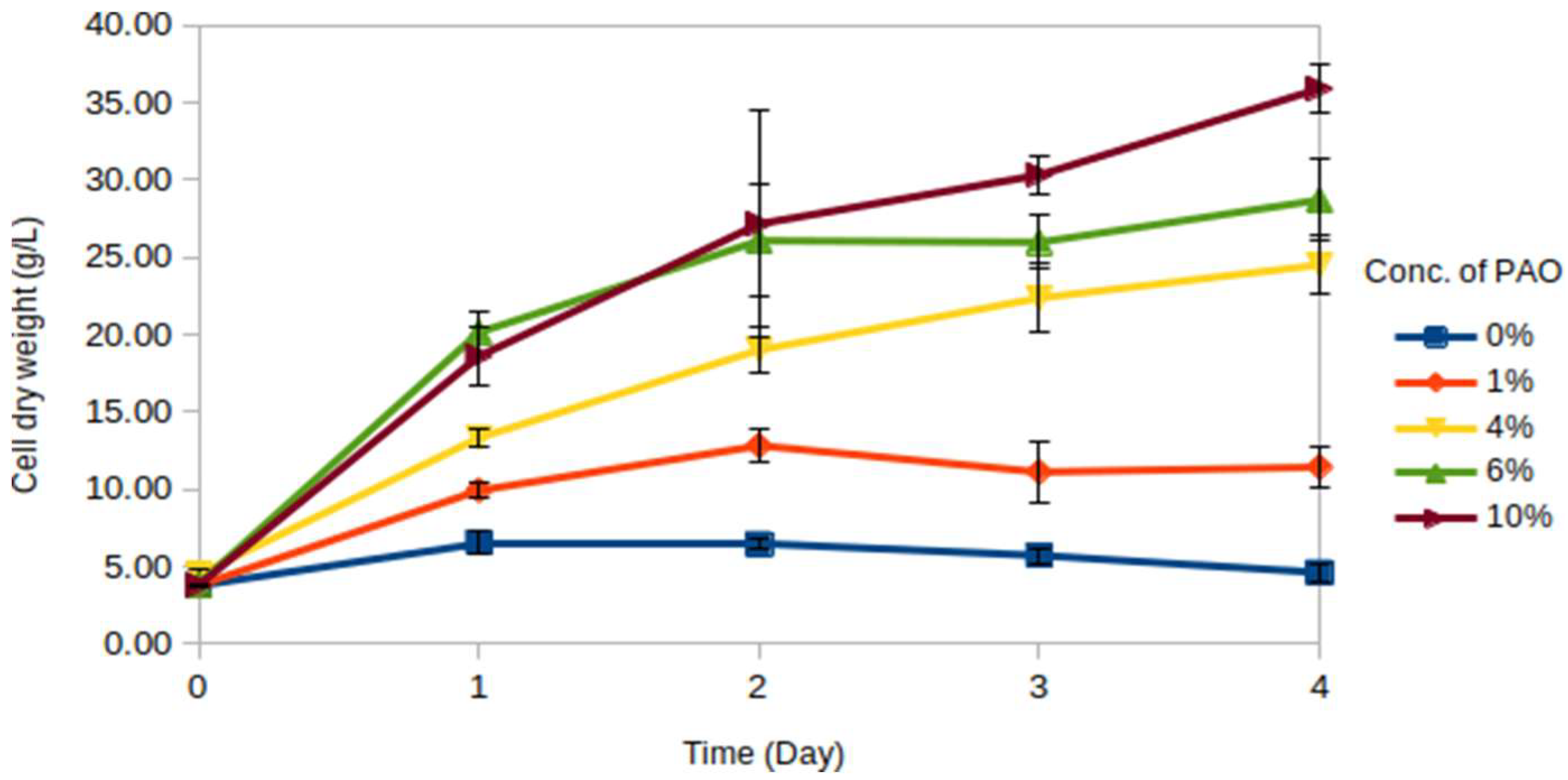

3.1. Growth of Meyerozyma Guilliermondii in PAO

The strain was grown in a nutrient-rich medium (YP broth) containing PAO as the sole source of carbon (C). Yeast extracts and peptone serve as the main source of nitrogen (N) for both cell growth and lipid accumulation in the cells. The alteration of carbon/nitrogen (C/N) ratio of the media can significantly affect the overall lipid production. On most occasions, excess carbon and nutrient starvation, such as lower N in the media, are optimum for lipid accumulation in oleaginous yeast

L. starkeyi (Ratledge & Wynn, 2002). However, the optimization of such parameters has not been tested in the current study. In a previous study by Amza et al. (2019) using

L. starkeyi, the cell biomass and lipid yield were reported to be still high under a low C/N ratio, which was demonstrated as similar to the previous study. In this study, a similar demonstration was applied to another oleaginous yeast, named

Meyerozyma guilliermondii, using PAO as a source of carbon, and the growth of this strain is studied by generating cell dry weight (CDW) profile series for the strain grown in various concentrations of PAO for 4 days. The results from the fermentation are presented in a line graph, as shown in

Figure 1.

The negative control (without PAO) records the lowest CDW and declines after 1 day of cultivation. This situation cohered to the fact that carbon is an essential element for building blocks of living organisms, and thus, the cells supplemented with carbon sources proliferate better. Principally, the biomass yield, represented by the CDW obtained, increased as the concentration of PAO increased. The highest CDW is obtained in a medium containing 10% of PAO. The growth rates of the strain grown in 6% and 10% of PAO are equally rapid at the beginning of the fermentation. The cell growth curve in 6% of PAO starts to plateau after Day 2, while the cell growth in 10% of PAO continues to increase even though the rate is not as rapid as in the beginning. Moreover, cells in both 4% and 10% of PAO continue to grow until the final day of the fermentation (Day 4). Overall, this result suggests that a higher concentration of PAO can promote cell growth and thus be used as a substrate.

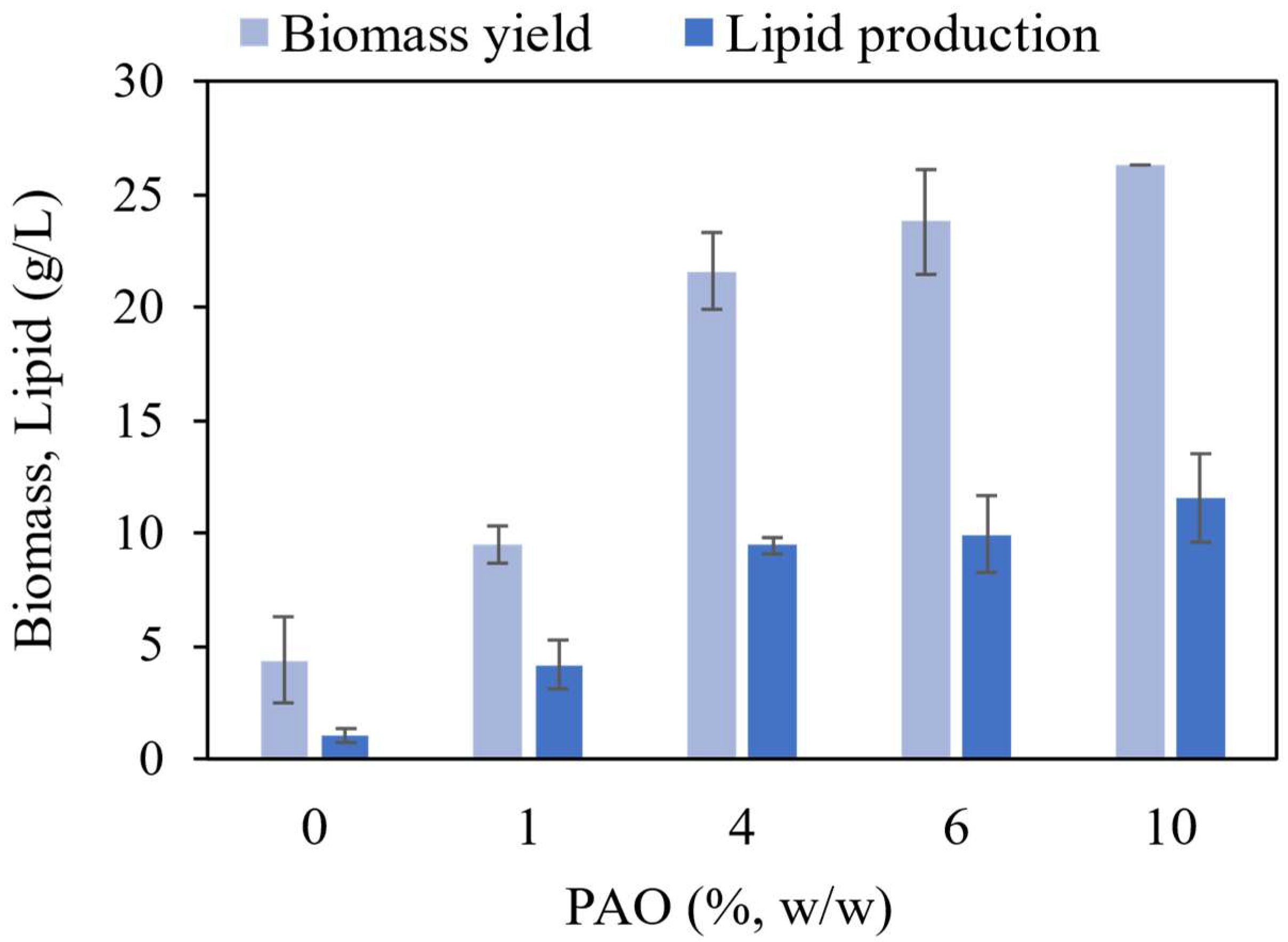

3.2. Effect of PAO on Biomass Yield and Lipid Production

Figure 2 shows a compound bar graph illustrating the harvested cell biomass and lipid production of

M. guillermondii. The data were calculated, compared, and illustrated.

The result clearly showed that an increase in PAO could simultaneously increase the biomass yield and total lipid production. When the carbon source concentration in the fermentation medium increases, the overall C/N ratio also increases. The availability of excess sugar is converted to intracellular lipids as lipid storage, which is essential for cell growth, stress response, and the survival of the species (Chapman et al., 2012). The differences in biomass yield are more considerable, from 0% to 4% of PAO than those from 4% to 10% of PAO.

The biomass yield from the harvested cells (

Figure 2) is slightly lower than CDW obtained from the sampled cells on Day 4 (

Figure 1), which technically is supposed to be the same. This is because some nutrients in the liquid medium have already been consumed by the cell. This may lead to a significant reduction of the actual volume of the medium at the end of the fermentation. Thus, the higher measured volume of the medium used in the following formula leads to a lower biomass yield obtained for the harvested cells.

The highest lipid content (45.33 % w/w) was obtained when the strain was grown in 4% of PAO. However, the lipid yield obtained in 4% of PAO is approximately 2.1 g/L lower than the lipid yield obtained in 10% of PAO. Several factors affect the lipid accumulation, and the subsequent lipid content calculated from each variable. First, since PAO solidifies and tends to clump together after it is added into the medium, the concentration of PAO in each medium might not represent the actual concentration intended to prepare. Furthermore, when PAO is not distributed evenly in the medium, the accessibility of the cells to the carbon substrate within the medium might also be affected. Nevertheless, constant agitation might help to reduce the inconsistency. Secondly, lipid accumulation is affected by the growth phase of the yeast (Uzuka et al., 1985). More lipids accumulate when the yeast enters the early stationary phase. From

Figure 1, the growth rate of cells supplemented by 10% of PAO appeared to increase more rapidly than the others. This could contribute to the lower lipid content obtained than the other concentrations. The lipid content might differ in 10% PAO if the fermentation period is prolonged. The summary of the biomass yield and lipid production is shown in

Table 1.

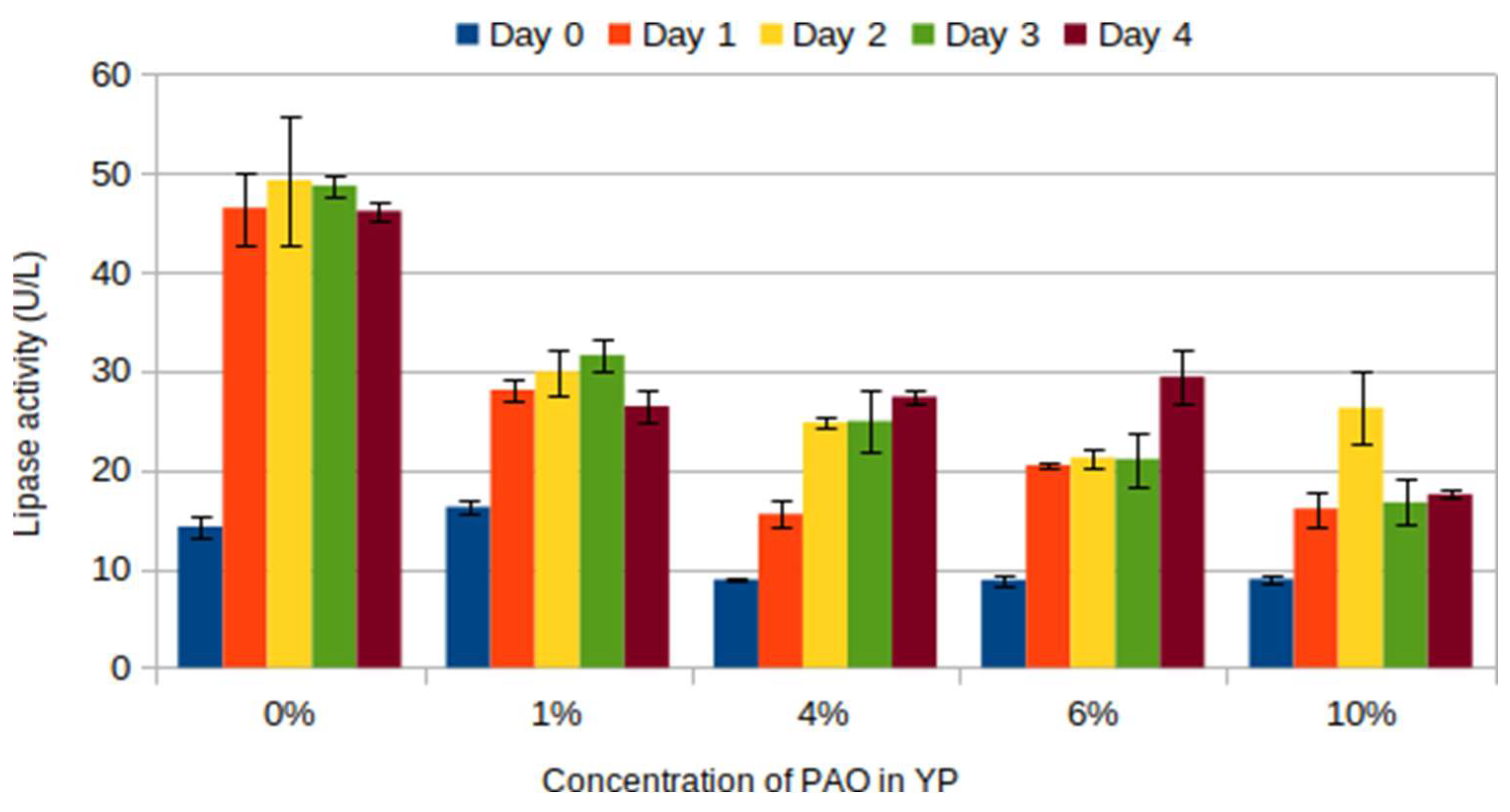

The lipase activities of cells grown in the presence of PAO are lower than the negative control (

Figure 3). PAO contains high amounts of free fatty acids. This could be why the lipase activities in the presence of PAO are lower. The cells do not need to secrete extracellular lipase because the simplest free fatty acid is already available. Furthermore, in this way, the cells can conserve energy for other essential metabolisms as the secretion can consume ATP.

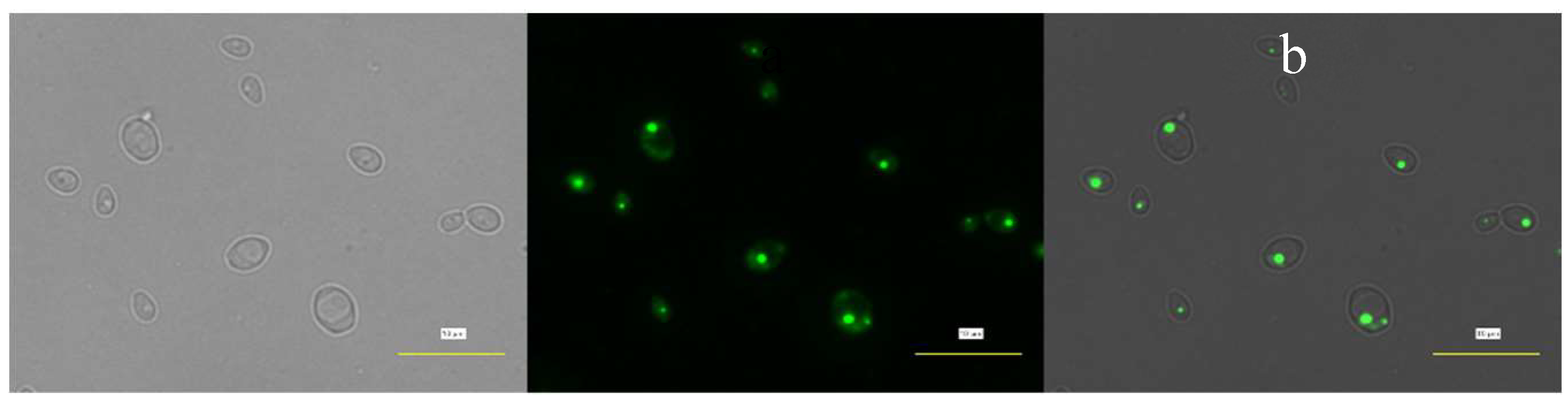

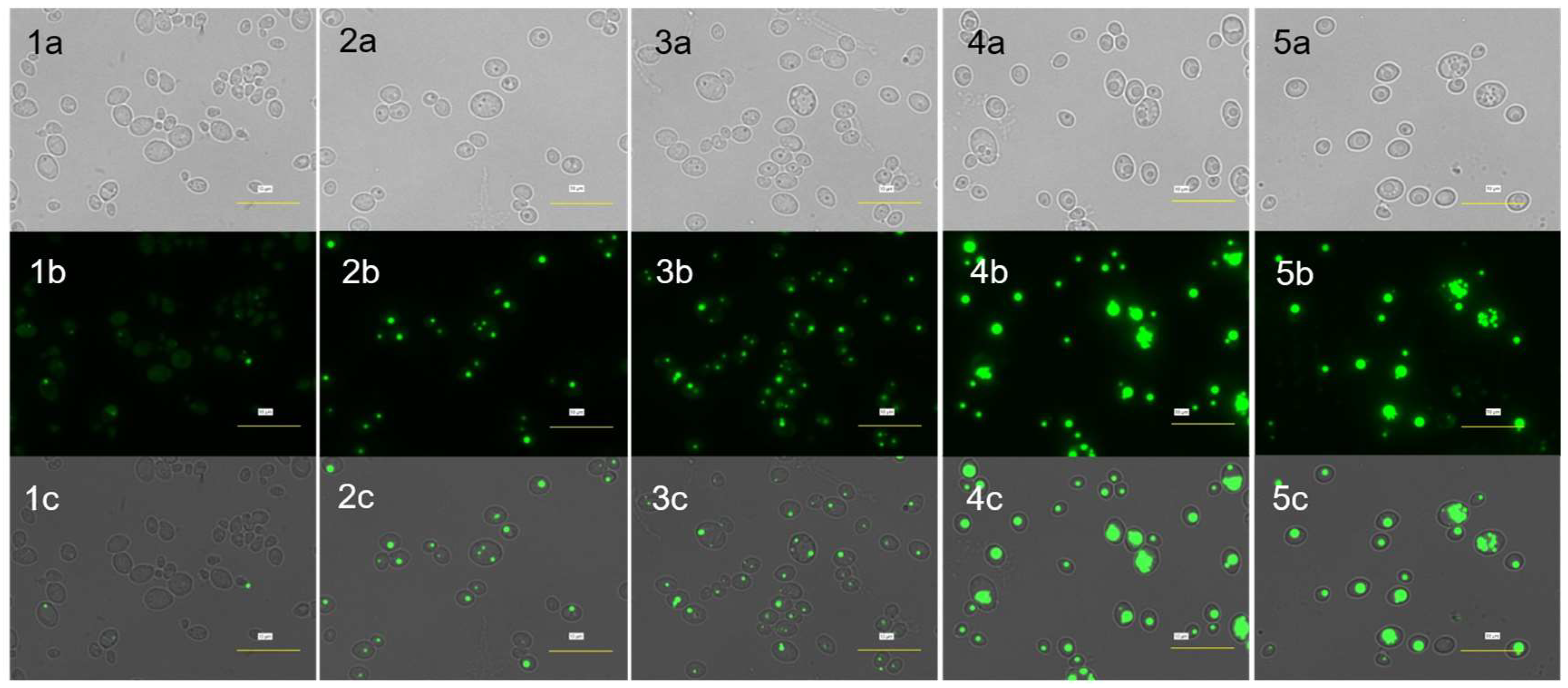

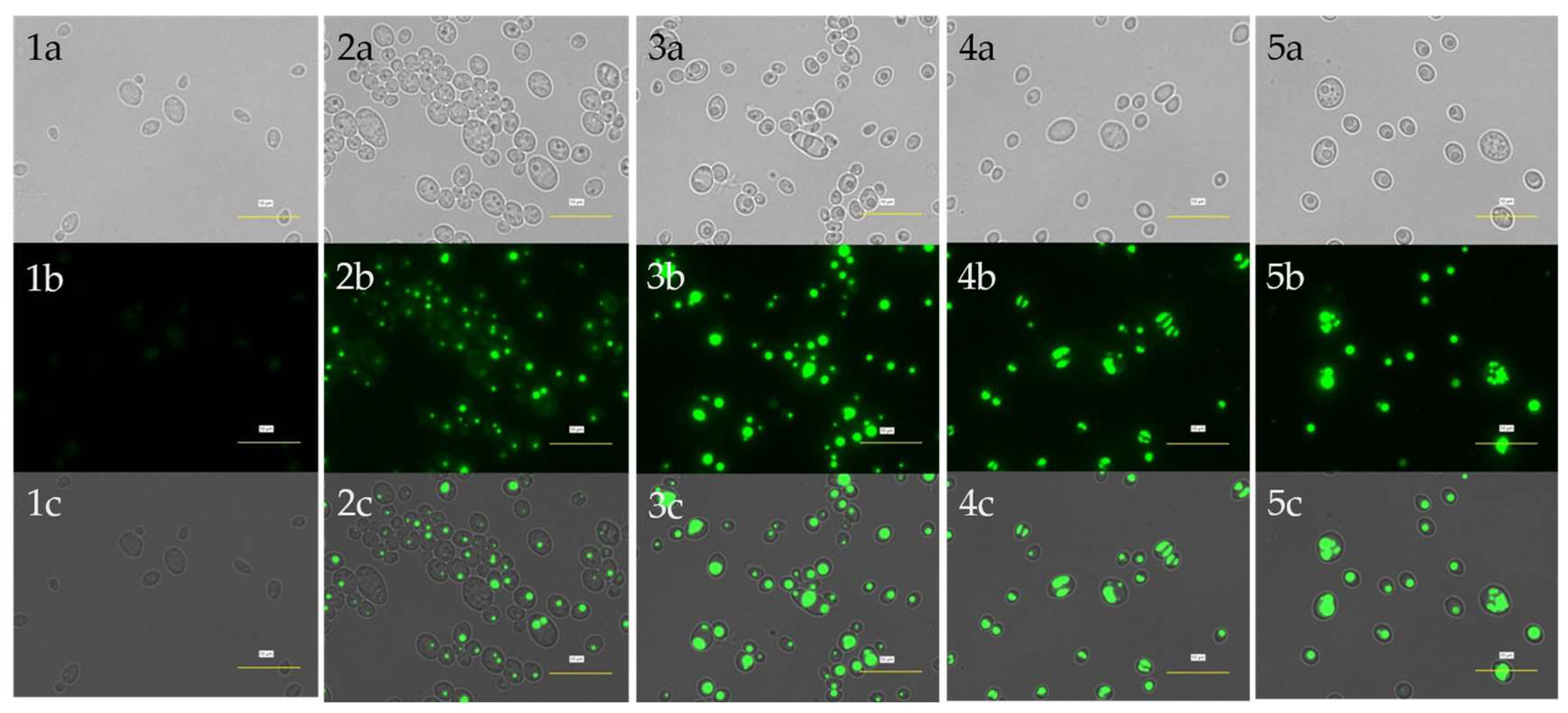

3.3. Visualization of Lipid Bodies

The accumulated single-cell lipids were visualized, analyzed, and compared qualitatively using brightfield microscopy (which generates images with shadier objects on darker backgrounds) and fluorescence microscopy (which generates images with fluorescence).

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the strain's lipid accumulation on Day 0 and Day 2, respectively.

The green fluorescence in images (b) and (c) indicates the accumulated lipid in TAGs. The intensity of green fluorescence might also indicate the amount of TAGs accumulated in the cell. Without any carbon source, fluorescence intensity appears fainter after 2 days of cultivation. This may suggest that the cell has lost some of its lipid storage or, in other words, has utilized its endogenous lipid due to stress (nutrient limitation) and thus results in fainter fluorescence on Day 2.

Figure 6

According to Holdsworth & Ratledge (1988), oleaginous yeast tends to consume its food reserve under carbon starvation, indicating that lipid metabolism is a highly controlled cellular process in yeast. On the other hand, with higher concentration of PAO (6% and 10%), the cells appeared to accumulate more lipid after 2 days of cultivation. As regards to this, it is suggested that the lipid accumulating process is activated in carbon-rich condition. Moreover, there are more multiple smaller lipid bodies being observed in the cells fed with 6% and 10% of PAO. In relation to this, a higher concentration of PAO may somehow induce the cells to accumulate lipid in several lipid bodies in smaller packs instead of accumulating all in a single but larger pack. This phenomenon may also be associated with the development of peroxisomes, which are typically induced when the yeast is grown in an environment or medium containing high fatty acids or alkanes (Teranishi et al., 1974; Veenhuis et al., 1987). The fatty acids from the PAO are ultimately taken into the cells and are converted into acetyl co-A, leading to intracellular lipid synthesis within the respective peroxisomes formed. Comparing the accumulated lipid across the series in

Figure 5, it is found that fluorescence intensity too increases when the concentration of PAO increases. Thus, when more carbon sources are made available for the cells, the ingestion will also increase and, therefore, contribute to higher lipid accumulation. Altogether, the results suggest the potential of using PAO as a carbon substrate for microbial single-cell oil (SCO) production.

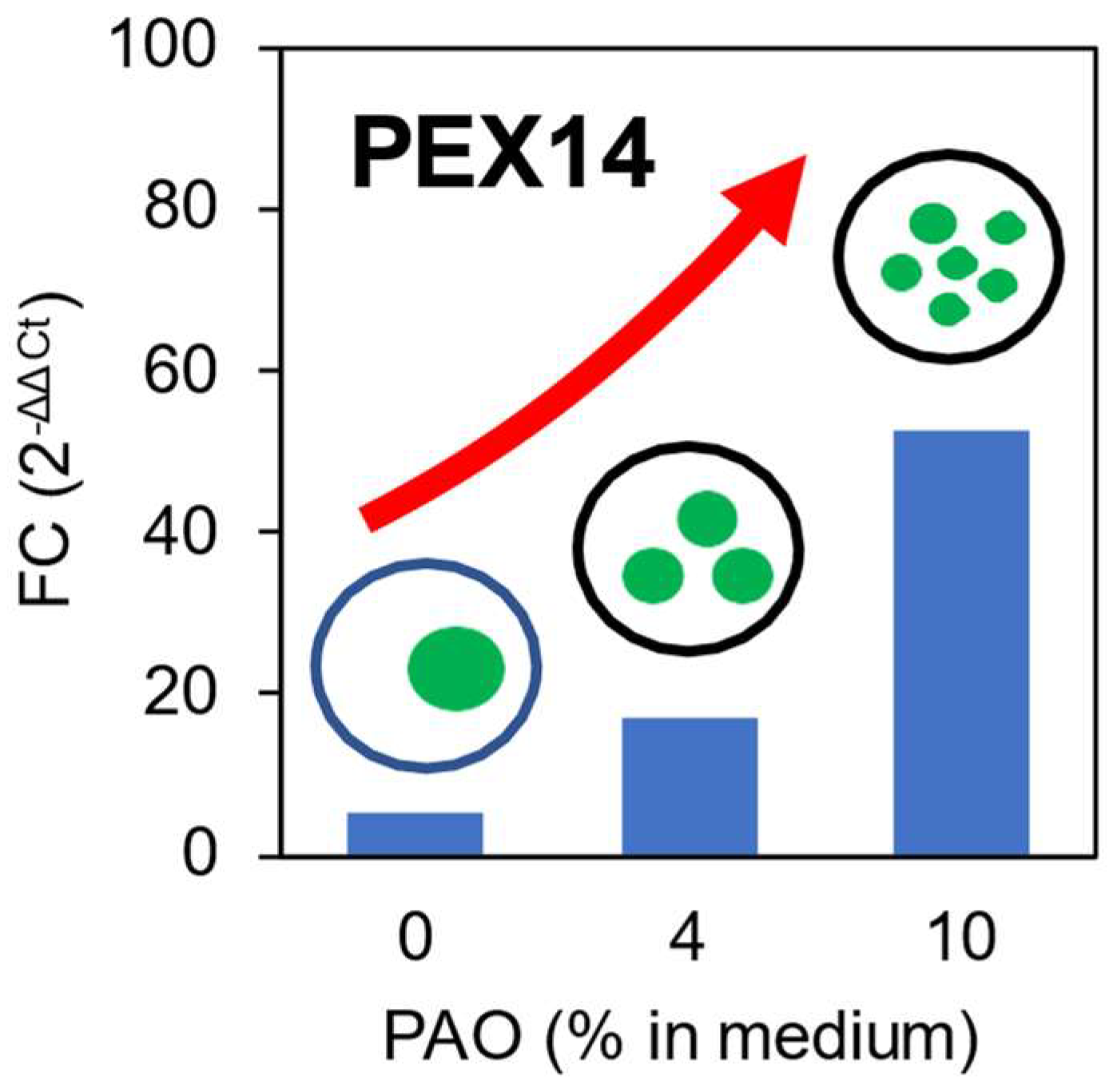

The gene expression analysis was performed to investigate and check the possible association between the formation of multiple lipid bodies and the peroxisomal function. The housekeeping gene (TUB1) is selected as the control for the analysis of gene expression. Among all the selected genes, PEX14 gene which encodes for the peroxisomal membrane protein is analyzed and discussed. According to the illustration from

Figure 7, the expression of PEX14 gene is higher when the concentration of PAO increases. Thus, it is suggested that the higher concentration of PAO may activate more PEX14 gene which resulted to more formation of peroxisomes within the cell. The expression level of PEX14 may give a direct effect to how the exogenous lipid is accumulated or stored. Thus, the formation of peroxisomes may lead to observing multiple lipid bodies observed in 6% and 10% of PAO.

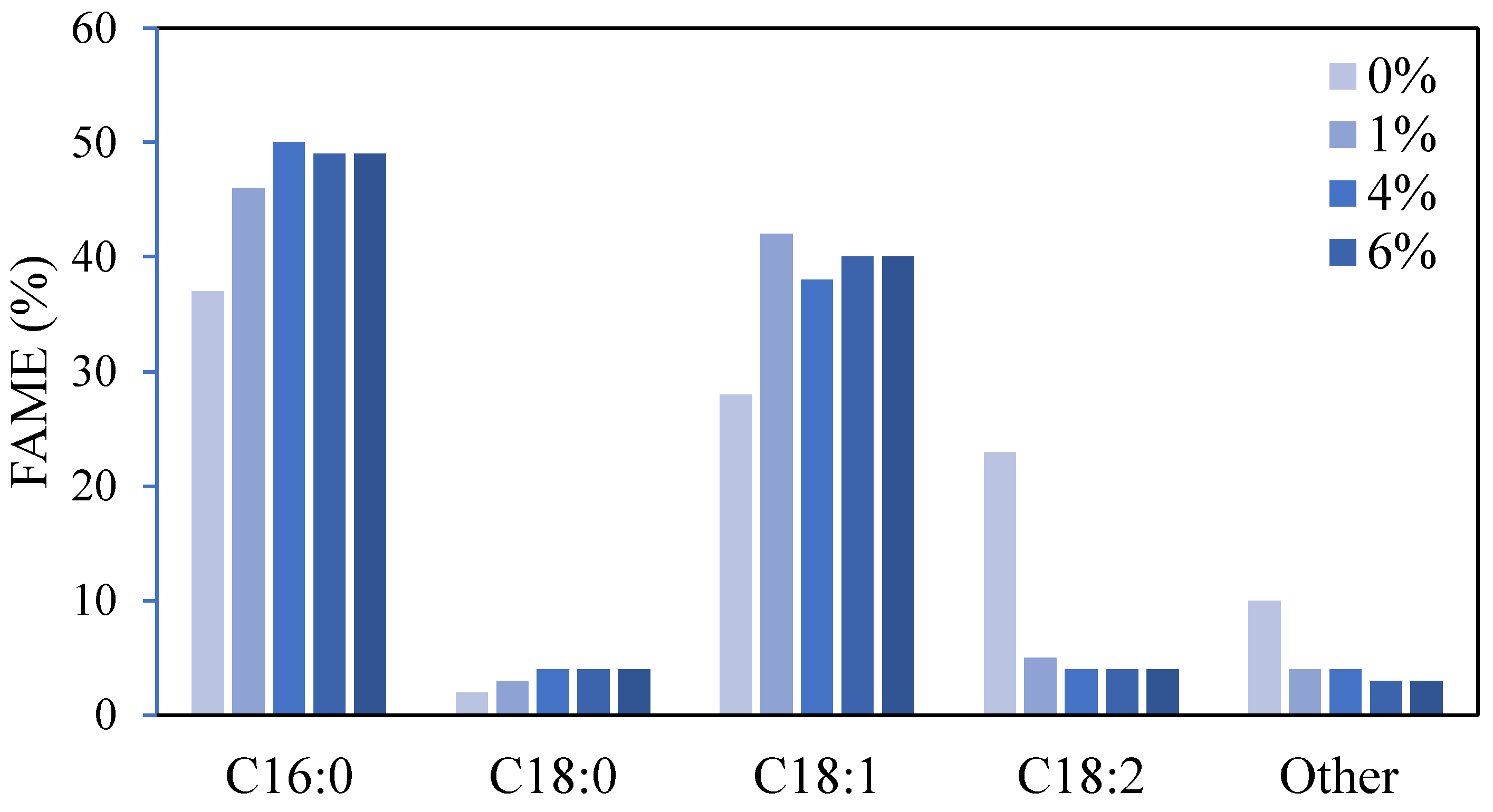

3.4. Analysis of Fatty Acid Composition

The lipid obtained from the cells grown in different concentrations of PAO was trans-methylated and analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS).

Figure 8 illustrates the fatty acid profile of the oil produced by the strain in batch fermentation under flask cultivation.

Most lipids produced are long-chain unsaturated fatty acids containing 16-carbon and 18-carbon lipid compounds. There is palmitic acid (C16:0), palmitoleic acid (C16:1), stearic acid (C18:0), oleic acid (C18:1), and linoleic acid (C18:2). The aforementioned lipid composition has the resemblance to that of plant-derived oils (Sitepu et al., 2014), specifically the palm oil. For this reason, oil derived from yeast has the potential to replace plant-derived oil as raw material for the production of valuable products such as biodiesel. Oil derived from microorganisms does not require huge amounts of land for cultivation as most plants do. Also, it can solve the higher global price for plant oil due to competition between the demand for edible oils and the demand for biofuel production (Shaah et al., 2021).

There are huge contrasts between the composition of fatty acids in the lipids of M. guillermondii grown in the presence of a carbon source and without. Generally speaking, the composition of fatty acids produced in the yeast cells is highly dependent on the medium of cultivation and fermentation conditions (Patel et al., 2016). The type of carbon source used contributes to differing fatty acid profiles by activating key metabolic genes involved in specific lipid biosynthesis pathways (Sun et al., 2021). This may be the major reason for different FA profiles being observed in the presence and absence of PAO and when glucose is used as feedstock (Appendix-Figure 13).

The compositions of fatty acids in the lipid are almost similar for cells grown in the presence of PAO. Among all, C16:0 and C18:1 account to more than 80% of the fatty acids detected. The fatty acids are the main fatty acids in the yeast fat (Deinema, 1961). All in all, the result of FAME analysis suggests that adding PAO can alter the composition of the fatty acids synthesized and accumulated in the cells. Reasonably, the carbon element from the substrate is vital to form the organism’s macromolecules and ultimately constitutes a part of itself. Thus, this also further indicates the potential of M. guillermondii to utilize PAO and accumulate oil intracellularly.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, PK; Data curation, NAAZ and TK; Formal analysis, NAAZ and TK; Funding acquisition, CO; Investigation, NAAZ, TK, PK; Methodology, PK; Project administration, PK and CO; Resources, PK and CO; Supervision, PK and CO; Validation, NAAZ, PK and CO; Writing – original draft, NAAZ, TK and PK.

Funding

This work was supported by the International Joint Program, Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development (SATREPS) from the Japan Science and Technology Agency and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JST and JICA), Japan.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Alhaji, M.H.; Sanaullah, K.; Lim, S.-F.; Khan, A.; Hipolito, C.N.; Abdullah, M.O.; Bhawani, S.A.; Jamil, T. Photocatalytic treatment technology for palm oil mill effluent (POME) – A review. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2016, 102, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amza, R.L.; Kahar, P.; Juanssilfero, A.B.; Miyamoto, N.; Otsuka, H.; Kihira, C.; Ogino, C.; Kondo, A. High cell density cultivation of Lipomyces starkeyi for achieving highly efficient lipid production from sugar under low C/N ratio. Biochem. Eng. J. 2019, 149, 107236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angerbauer, C.; Siebenhofer, M.; Mittelbach, M.; Guebitz, G. Conversion of sewage sludge into lipids by Lipomyces starkeyi for biodiesel production. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 3051–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, K. D. , Dyer, J. M., & Mullen, R. T. (2012). Biogenesis and functions of lipid droplets in plants: Thematic Review Series: Lipid Droplet Synthesis and Metabolism: from Yeast to Man. Journal of Lipid Research, 53(2), 215–226.

- Deinema, M. H. (1961). Intra-and extra-cellular lipid production by yeasts. Veenman. 61(2):1-54.

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Stanley, G.H.S. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govender, T.; Ramanna, L.; Rawat, I.; Bux, F. BODIPY staining, an alternative to the Nile Red fluorescence method for the evaluation of intracellular lipids in microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 114, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.; Yusoff, F.; Phang, S.; Ang, K.; Mohamed, S. Nutritional values of chironomid larvae grown in palm oil mill effluent and algal culture. Aquaculture 1997, 158, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, G. The Chemistry and Technology of Edible Oils and Fats and their High Fat Products; Academic Press: 2013.

- Holdsworth, J.E.; Ratledge, C. Lipid Turnover in Oleaginous Yeasts. Microbiology 1988, 134, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Woon, C.W.; Ethiraj, B.; Cheng, C.K.; Yousuf, A.; Khan, M.R. Ultrasound Driven Biofilm Removal for Stable Power Generation in Microbial Fuel Cell. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Yousuf, A.; Karim, A.; Pirozzi, D.; Khan, M.R.; Ab Wahid, Z. Bioremediation of palm oil mill effluent and lipid production by Lipomyces starkeyi: A combined approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1779–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, T.; Nasu, M. Current bioremediation practice and perspective. 2001, 92, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwuagwu, J.O.; Ugwuanyi, J.O. Treatment and Valorization of Palm Oil Mill Effluent through Production of Food Grade Yeast Biomass. J. Waste Manag. 2014, 2014, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juanssilfero, A.B.; Kahar, P.; Amza, R.L.; Miyamoto, N.; Otsuka, H.; Matsumoto, H.; Kihira, C.; Thontowi, A.; Yopi; Ogino, C. ; et al. Selection of oleaginous yeasts capable of high lipid accumulation during challenges from inhibitory chemical compounds. Biochem. Eng. J. 2018, 137, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juanssilfero, A.B.; Kahar, P.; Amza, R.L.; Miyamoto, N.; Otsuka, H.; Matsumoto, H.; Kihira, C.; Thontowi, A.; Yopi; Ogino, C. ; et al. Effect of inoculum size on single-cell oil production from glucose and xylose using oleaginous yeast Lipomyces starkeyi. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2018, 125, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadir, A. A., Abdullah, S. R. S., Othman, B. A., Hasan, H. A., Othman, A. R., Imron, M. F., Ismail, N. ‘Izzati, & Kurniawan, S. B. (2020). Dual function of Lemna minor and Azolla pinnata as phytoremediators for Palm Oil Mill Effluent and as feedstock. Chemosphere, 259, 127468.

- Kaniapan, S.; Hassan, S.; Ya, H.; Nesan, K.P.; Azeem, M. The Utilisation of Palm Oil and Oil Palm Residues and the Related Challenges as a Sustainable Alternative in Biofuel, Bioenergy, and Transportation Sector: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntom, A.; Siew, W.-L.; Tan, Y.-A. Characterization of palm acid oil. Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society 1994, 71, 525–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.K.; Lee, K.T. Renewable and sustainable bioenergies production from palm oil mill effluent (POME): Win–win strategies toward better environmental protection. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Du, W.; Liu, D. Perspectives of microbial oils for biodiesel production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 80, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Market, G.M.F.; By Manufacturers, Regions, Type and Application, Forecast to 2024. Global Info Research. 2020. Available online: Https://www.globalinforesearch.com/Reports/525193/Fulvic-Acid (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Oguro, Y.; Yamazaki, H.; Shida, Y.; Ogasawara, W.; Takagi, M.; Takaku, H. Multicopy integration and expression of heterologous genes in the oleaginous yeast, Lipomyces starkeyi. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2015, 79, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.; Arora, N.; Sartaj, K.; Pruthi, V.; Pruthi, P.A. Sustainable biodiesel production from oleaginous yeasts utilizing hydrolysates of various non-edible lignocellulosic biomasses. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 836–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).