1. Introduction

Streptococcus agalactiae, also known as Group B Streptococcus (GBS), is a leading cause of neonatal and infant infections.[

1] In neonates, GBS, alongside

E. coli, is the most common cause of culture-confirmed sepsis in high-income countries (HIC)[

2], with a case fatality rate of 3.4% in term births and 3.7% in cases of extreme prematurity.[

3] GBS meningitis is associated with high mortality, and neurological impairments have been documented in 32–44% of surviving neonates.[

4]Treating GBS infections promptly and effectively is crucial to reducing mortality and long-term complications.[

5,

6] The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends initiating prophylactic antibiotic treatment within one hour of suspected sepsis diagnosis.

In the UK, guidance from the Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists (Green-top Guidelines [

7]) advises against universal GBS screening but recommends providing pregnant women with informational leaflets. Antibiotic therapy should be initiated in cases where GBS was detected in a previous pregnancy, during the current pregnancy, or in the presence of pyrexia during labour. Benzylpenicillin is the first-line treatment, with cephalosporins or vancomycin as alternatives for penicillin-allergic patients.[

8] Neonatal treatment typically includes gentamicin combined with either benzylpenicillin or ampicillin. Erythromycin and clindamycin are not recommended.

Antibiotic resistance in GBS is a growing concern globally. The gold standard susceptibility assay is broth microdilution (BMD), as per EUCAST and ISO 20776-1 standards [

9,

10,

11]. However, BMD can be problematic for GBS due to the need for lysed horse blood supplements, which complicate turbidity readings [

10]. Use of automated systems (e.g. VITEK2, Phoenix, Microscan WalkAway, etc.) are more common in large clinical microbiology laboratories, perform well on GBS. The use of Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion on solid agar is easier to perform in small scale settings and non-GBS bacterial contaminants are easier to identify on agar. MIC determination using serial antibiotic agar-dilution is not a listed recommended method in EUCAST or CLSI (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute) GBS susceptibility testing guidelines. However, it has been used in Belgium and Japan with more than 200 GBS isolates [

12,

13].

In this study, we compare BMD and agar-dilution methodologies using twenty-four GBS strains from a previously published cohort of UK invasive isolates of known antibiotic susceptibility profiles, correlated to whole genome sequence analysis identifying defined antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) [

14]. This panel includes a range of fully susceptible strains and strains carrying ARGs for each class of antimicrobial tested (except for penicillin). Results demonstrate that both methods yield comparable outcomes, potentially offering greater flexibility for GBS resistance screening, particularly when examining large retrospective cohorts.

2. Results

Details of the twenty-four GBS strains utilised (including NCTC (National Collection of Type Culture) numbers, ARGs, serotype and sequence type) are listed in

Table 1). Quality control strains

Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC (American Typed Culture Collection) 700677 (resistant to erythromycin, penicillin, and tetracycline) and

Streptococcus pneumoniae NCTC12977 (susceptible to all) were also run in parallel, as per EUCAST guidelines[

15]. All isolates were initially cultured on Colombia Horse Blood Agar (Oxoid, UK) at 37

oC under ambient O

2 concentrations and single colonies were re-suspended in 3mL sterile 0.85% saline (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) at a concentration of 0.5 McFarland (1.5 × 108CFU/mL).

Determining minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) by assessing bacterial growth turbidity in Mueller-Hinton Fastidious (MH-F) broth was more challenging compared to using standard Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth (e.g., for

Escherichia coli) due to "trailing growth" [

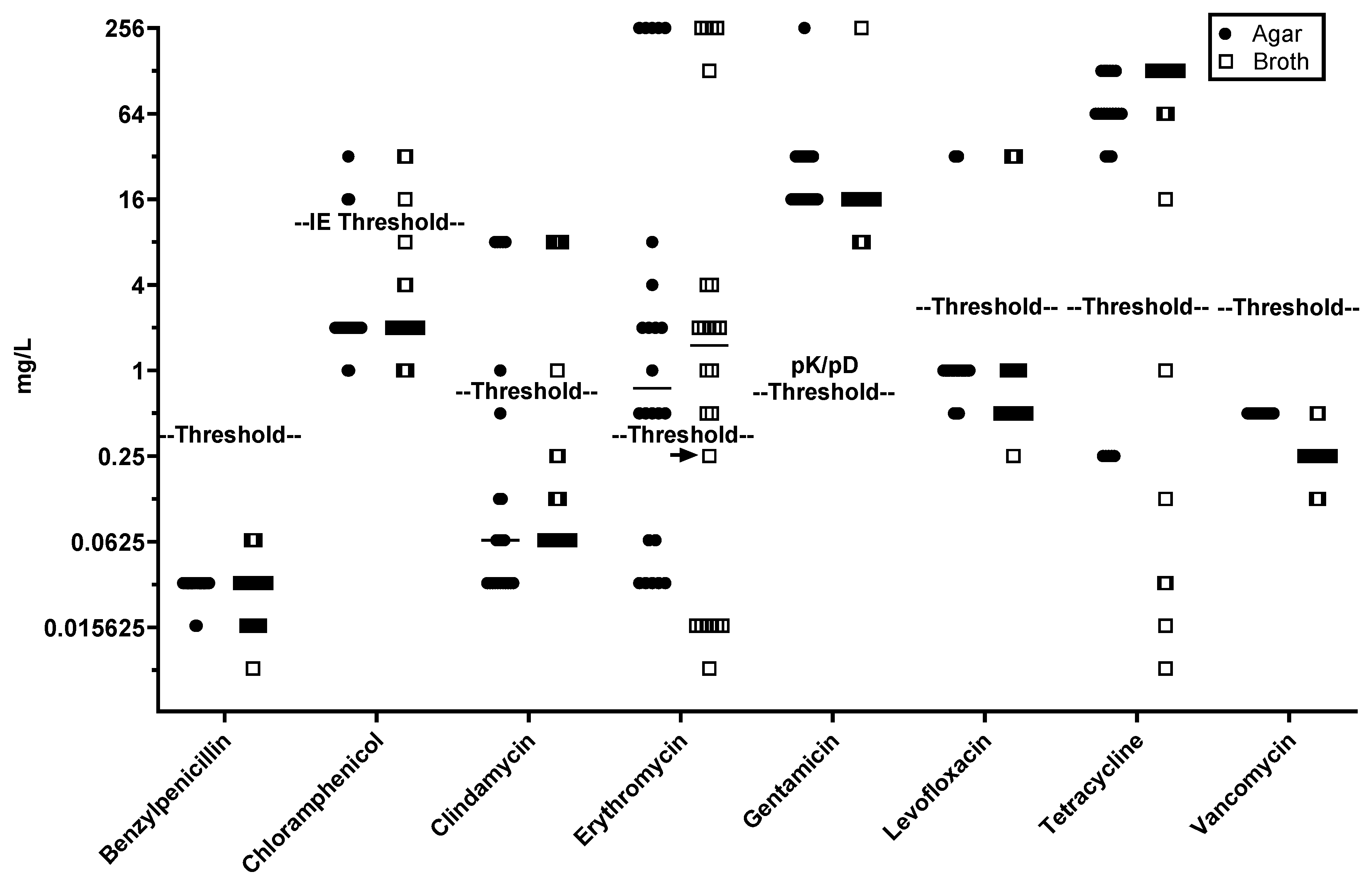

10], a phenomenon in which the turbidity cut-off for bacterial growth inhibition is unclear, as we consistently observed with MIC determinations for erythromycin. Despite this, good MIC concordance was observed between agar-dilution and broth microdilution (BMD) methods (

Figure 1).

Using EUCAST established resistance thresholds (

Table 1), all strains positive for

tet(L),

tet(M), and/or

tet(O) were resistant to tetracycline and isolates carrying mutations

gyrA S81L and/or

parC S79F were resistant to levofloxacin (

Figure 1). Isolates carrying

mef(A) and

msr(D) as sole macrolide resistance genes were consistently identified as resistant to erythromycin (MICs 2–4 mg/L) by both methods. Recently, EUCAST guidelines have changed for chloramphenicol where was 8 mg/L previously set as the threshold of for "resistant" has been altered to "IE" (Insufficient Evidence) in the EUCAST Clinical Breakpoint Tables v. 14.0; however, all strains positive for

cat(Q) or

cat(C194) were above the previous threshold (

Figure 1). While the lowest gentamicin MIC for any GBS isolate is well above a reasonable pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) threshold for clinical intervention (0.5 mg/L) the single isolate carrying

aac(6')-aph(2") exhibited a gentamicin MIC >128 mg/L, relative to 16-32 mg/L observed for all other isolates by both methods.

Data for GBS isolates carrying erm(A) and erm(B) methylases showed less consistency: three erm(A)-carrying isolates gave an MIC of 0.25 mg/L (just below the resistance threshold) in one of three BMD replicates, while a single erm(B)-carrying isolate (PHEGBS0738) gave an MIC of 0.25 mg/L for two of three BMD replicates and one of three agar-dilution replicates. Although methylases often require macrolide induction for clindamycin resistance, one of seven erm(A)-carrying isolates and six of seven erm(B)-carrying isolates displayed clindamycin resistance in both methods. An isolate carrying lsa(E) (NCTC14907) was consistently susceptible to clindamycin, with an MIC of 0.25 mg/L for two of three BMD replicates. Additionally, an isolate carrying both lnu(C) and erm(A) (NCTC14903) was consistently clindamycin-susceptible by both methods.

Strain-matched MIC concordance analysis between BMD and agar-dilution (

Table 2) demonstrated that most results were within one dilution, regardless of the method. This establishes that agar-dilution is comparable to BMD for MIC determination, with concordance rates mostly ranging from 83–100% across antibiotics and strains tested. Tetracycline was an exception, with only 52% concordance and greater variability between replicates. Notably, tetracycline MICs consistently increased with extended incubation, a phenomenon not observed for other antibiotics.

Evaluation of isolate susceptibility profiles across agar-dilution and BMD methods (

Table 3) revealed near-perfect agreement (Kappa value >0.9) for chloramphenicol, clindamycin, erythromycin, and levofloxacin, except for tetracycline. No Kappa values were calculated for benzylpenicillin, gentamicin, and vancomycin due to 100% agreement in susceptibility profiles between methods. Erythromycin, despite its lower concordance (94.44%), still displayed strong agreement (Kappa value 0.8–0.9).

3. Discussion

With a few exceptions, EUCAST recommends the use of the broth microdilution reference method as the AST gold standard, including fastidious organisms, using MH-F [

10] Similarly, CLSI also indicate that agar-dilution has not been internally performed or reviewed.[

9] However, interrogation of large cohorts against multiple antibiotics by BMD is not feasible, contamination is easier to identify on agar, and avoids “trailing growth”[

9] (a well-known phenomenon that complicates BMD determination MICs). There are many reports in the literature determining MICs using agar-dilution,[

12,

13,

16,

17] but to date a systematic comparison of BMD and agar-dilution concordance for GBS has not been performed, as Reynolds

et al., have done for

S. pneumoniae.[

18]

Amsler

et al., reported a consistent 2-fold (on average) lower MIC for agar-dilution relative to BMD for a combined subgroup of 21 GBS and 18

Streptococcus pyogenes, but with a 98.2% agreement within ±2 log2 dilutions.[

19] We did not observe this skewing in our study, except for tetracycline which was also particularly variable, with only 52.78% agreement within ±1 log2 dilution. Greater than 90% agreement, within ± 1 log2 dilution, was observed for all other antimicrobials except erythromycin (83.33%) and vancomycin (87.5%).

The variability in tetracycline MICs remains unexplained, although others have reported that doxycycline degrades in solution with increasing time[

20]. The pronounced variability for tetracycline MICs remains unexplained, especially as it was not subject to the “trailing growth” we only consistently observed for erythromycin in BMD. While Reynolds

et al.,[

18] indicated more variance between BMD and agar-dilution for tetracycline than erythromycin, clindamycin, and levofloxacin, they found still 98.9% agreement when the comparison was extended to ±2 log2 dilutions compared to our 80.5% agreement for the same range.

Tetracycline overuse of the 1960’s left a legacy of most (>90%) GBS carrying tetracycline resistance genes,[

21] agar-dilution remains suitable for MIC determination for other therapeutically relevant antimicrobials. This is particularly important when screening large cohorts of GBS isolates in antimicrobial resistance surveillance studies.

In conclusion, we have performed a direct comparison for determining MICs between agar and broth dilution using a defined cohort of GBS isolates with characterised resistance genes or mutations and found excellent concordance for 7 out of 8 antibiotics tested. Agar-dilution may be of utility for routine clinical laboratory use with high sample loads and further studies to evaluate clinical utility may be beneficial. It would be prudent to use agar-dilution for retrospective batch analysis for AMR surveillance, rendering large scale screening manageable for multiple antibiotics to contribute to the evidence-base for resistance trends to inform policy on first- and second-line therapeutics.

4. Materials and Methods

Antimicrobial sensitivity testing was compared using Muller Hinton Fastidious (MH-F) broth (BD, USA) in 96-well plates and MH-F agar (Neogen, USA) in 90 mm petri dishes, both supplemented with 10% lysed horse blood (TCS Biosciences, UK) and β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide as per EUCAST guidelines. [

10]. MICs were determined for benzylpenicillin, chloramphenicol, clindamycin, erythromycin, gentamicin, levofloxacin, tetracycline and vancomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, UK) at concentration ranges between 0.008-128 mg/L.

For solid agar dilution antibiotic stocks were prepared at 100 mg/ml in either DMSO or water and diluted into three starting stocks of 2560, 80 and 2.5 mg/L. these were then aliquoted into 50 mL falcon tubes to achieve the full serial dilution as shown in

Table 4.

Four-hundred and seventy-five mL of MH agar was autoclaved and equilibrated to 50

oC. Once stable at this temperature, 25 mL (final concentration 5%) lysed horse blood and 20 mg/L β-NAD were added and mixed, prior to dispensing 20 mL into individually labelled universal containers containing antimicrobials from

Table 4 and resuspending antimicrobial dilutions prior to being poured into square agar plates (120 x 120 mm; Griener). Once plates were solid and allowed to dry thoroughly, a 0.5 McFarland suspension was made for each bacterial isolate to be tested and a 1:10 dilution aliquoted into a sterile 96-well plate. Once all isolates were prepared in the inoculation plate it was placed in a Mast Uri® Dot multipin inoculator (1 μL pin volume) and the prepared agar dilutions plates “stamped” in ascending order (starting with an antimicrobial-free growth control plate). Inoculated plates were allowed to dry at room temperature in the biological safety cabinet 15-30 minutes (to avoid streaking when turned), inverted and incubated for 18 hours at 37

oC then read.

For broth microdilution (BMD), 0.1mL of MH-F broth was added to each well and 0.1mL containing 256 mg/L antibiotic was added to the first row, mixed and then serially transferred across the plate to give a gradient of 128-0.008 mg/L, with the exception of the last two rows (penultimate row represents antibiotic free growth control and last row left for bacteria-free MH-F broth sterility control). Plates were incubated at 37 oC overnight without CO2 and BMD results were read using a light box as per EUCAST guidelines. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

MIC thresholds for resistance are listed in

Table 5. Ethical approval was not required as only NCTC or ATCC deposited type strains were used. Data was analysed by overall percentage concordance, fold-change in MICs between repeats, and by Cohen’s kappa to measure agreement of resistance profiles.

5. Conclusions

We have shown an acceptable level of concordance between agar-dilution and broth microdilution methods to establish the former as an acceptable and valid alternative to the latter method for AST. Agar dilution is a superior method for high-throughput AMR surveillance of retrospective cohorts as up to 12 different antimicrobials can easily be performed on 96 isolates per inoculation plate. We recognise that agar dilution would be impractical for routine clinical diagnostic use, due to the requirement of individual plates to establish a range of antimicrobials; however, agar dilution would be the method of choice where evaluation of retrospective cohorts would lend itself to identifying emerging GBS resistance trends and informing therapeutic guidelines.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, OBS and VJC; methodology, EARP; validation and formal analysis CF and EARP; investigation, CF and EARP; resources, OBS, SJB and AE; data curation, JC; writing—original draft preparation, TI and EARP; writing—review and editing, all authors; supervision, OBS; project administration, JC; funding acquisition, VC, SJB, AE. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the United Kingdom Health Security Agency (Juno project)

Institutional Review Board and Informed Consent Statement

Ethical approval was not required as only NCTC or ATCC deposited type strains were used for the investigations and horse blood products were supplied by commercial sources.

Data Availability Statement

Data available from corresponding author on request. All isolates available from public culture repositories, ENA references for genomic sequences have been provided for access through public database repositories.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Seale, A.C.; Bianchi-Jassir, F.; Russell, N.J.; Kohli-Lynch, M.; Tann, C.J.; Hall, J.; Madrid, L.; Blencowe, H.; Cousens, S.; Baker, C.J.; et al. Estimates of the Burden of Group B Streptococcal Disease Worldwide for Pregnant Women, Stillbirths, and Children. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017, 65, S200–S219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decoster, L.; Frans, J.; Blanckaert, H.; Lagrou, K.; Verhaegen, J. Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Group B Streptococci Collected in Two Belgian Hospitals. Acta Clin Belg 2005, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamagni, T.; Wloch, C.; Broughton, K.; Collin, S.M.; Chalker, V.; Coelho, J.; Ladhani, S.N.; Brown, C.S.; Shetty, N.; Johnson, A.P. Assessing the Added Value of Group B Streptococcus Maternal Immunisation in Preventing Maternal Infection and Fetal Harm: Population Surveillance Study. BJOG 2022, 129, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raabe, V.N.; Shane, A.L. Streptococcus Agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus). Microbiology S 2018, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, L.M.; Kadri, S.S. Antimicrobial Treatment Duration in Sepsis and Serious Infections. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020, 222, S142–S155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, M.; Shani, V.; Muchtar, E.; Kariv, G.; Robenshtok, E.; Leibovici, L. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Efficacy of Appropriate Empiric Antibiotic Therapy for Sepsis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010, 54, 4851–4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, R.; Brocklehurst, P.; Steer, P.; Heath, P.T.; Stenson, B. Prevention of Early-Onset Neonatal Group B Streptococcal Disease: Green-Top Guideline No. 36. BJOG 2017, 124, e280–e305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, A.; Bielicki, J.; Mathur, S.; Sharland, M.; Van Den Anker, J.N. Reviewing the WHO Guidelines for Antibiotic Use for Sepsis in Neonates and Children. Paediatr Int Child Health 2018, 38, S3–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CLSI M100 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; 30th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Pennsylvania, 2020; Vol. 8; ISBN 978-1-68440-067-6.

- EUCAST EUCAST V11: The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 11.0, 2021; 2021.

- ISO 20776-1: 2019. Susceptibility Testing of Infectious Agents and Evaluation of Performance of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test Devices—Part 1: Broth Micro-Dilution Reference Method for Testing the In Vitro Activity of Antimicrobial Agents Against Rapidly G; Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Decoster, L.; Frans, J.; Blanckaert, H.; Lagrou, K.; Verhaegen, J. Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Group B Streptococci Collected in Two Belgian Hospitals. Acta Clin Belg 2005, 60, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seki, T.; Kimura, K.; Reid, M.E.; Miyazaki, A.; Banno, H.; Jin, W.; Wachino, J.I.; Yamada, K.; Arakawa, Y. High Isolation Rate of MDR Group B Streptococci with Reduced Penicillin Susceptibility in Japan. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2015, 70, 2725–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, U.B.; Portal, E.A.R.; Sands, K.; Lo, S.; Chalker, V.J.; Jauneikaite, E.; Spiller, O.B. Genomic Analysis Reveals New Integrative Conjugal Elements and Transposons in GBS Conferring Antimicrobial Resistance. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EUCAST "The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 14.0, 2024. Http://Www.Eucast.Org 2024, 0–77.

- Kardos, S.; Tóthpál, A.; Laub, K.; Kristóf, K.; Ostorházi, E.; Rozgonyi, F.; Dobay, O. High Prevalence of Group B Streptococcus ST17 Hypervirulent Clone among Non-Pregnant Patients from a Hungarian Venereology Clinic. BMC Infect Dis 2019, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wei, Y.; Li, G.; Cheng, H.; Xu, Z.; Yu, Z.; Deng, Q.; Shi, Y. Comparison of Antimicrobial Efficacy of Eravacycline and Tigecycline against Clinical Isolates of Streptococcus Agalactiae in China: In Vitro Activity, Heteroresistance, and Cross-Resistance. Microb Pathog 2020, 149, 104502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, R.; Shackcloth, J.; Felmingham, D.; MacGowan, A.P.; Booth, J.; Brown, D.F.J.; Coles, S.; Harding, I.; Livermore, D.M.; Reed, V.; et al. Comparison of BSAC Agar Dilution and NCCLS Broth Microdilution MIC Methods for in Vitro Susceptibility Testing of Streptococcus Pneumoniae, Haemophilus Influenzae and Moraxella Catarrhalis: The BSAC Respiratory Resistance Surveillance Programme. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2003, 52, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amsler, K.; Santoro, C.; Foleno, B.; Bush, K.; Flamm, R. Comparison of Broth Microdilution, Agar Dilution, and Etest for Susceptibility Testing of Doripenem against Gram-Negative and Gram-Positive Pathogens. J Clin Microbiol 2010, 48, 3353–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lallemand, E.A.; Lacroix, M.Z.; Toutain, P.L.; Boullier, S.; Ferran, A.A.; Bousquet-Melou, A. In Vitro Degradation of Antimicrobials during Use of Broth Microdilution Method Can Increase the Measured Minimal Inhibitory and Minimal Bactericidal Concentrations. Front Microbiol 2016, 7, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, V. Da; Davies, M.R.; Douarre, P.; Rosinski-, I. Streptococcus Agalactiae Clones Infecting Humans Were Selected and Fixed through the Extensive Use of Tetracycline. 2015, 337549, 1–23. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).