Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Works

1.2. Contributions & Organization

- This study introduces a CBF-pilot design to generate stealthy maneuvers based on high-fidelity flight dynamics model that captures the complex behavior of non-stealth platforms, contrary to most of the existing studies using simplified kinematic flight dynamics model. The utilization of high-fidelity flight dynamics model provides an accurate representation of flight dynamics, allowing for better assessment of radar observability under various and realistic operational conditions.

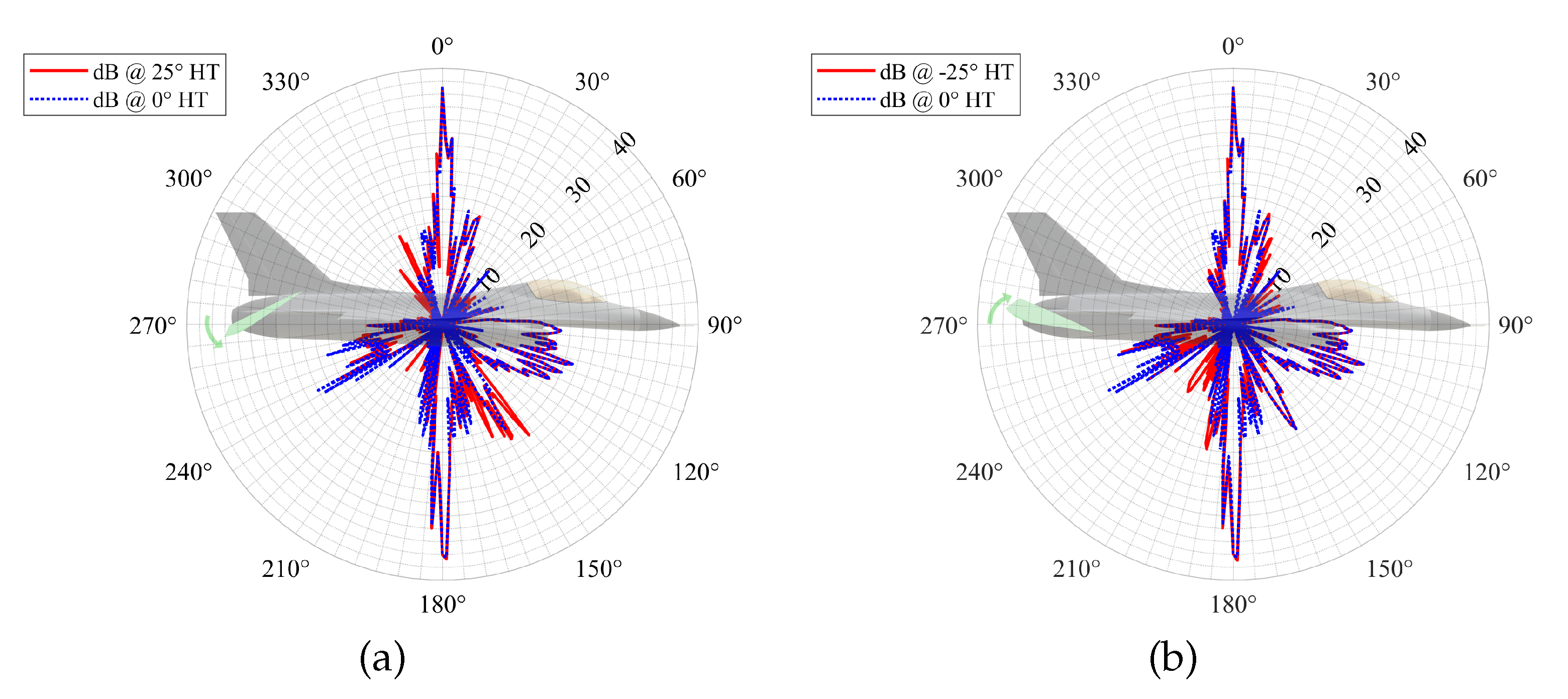

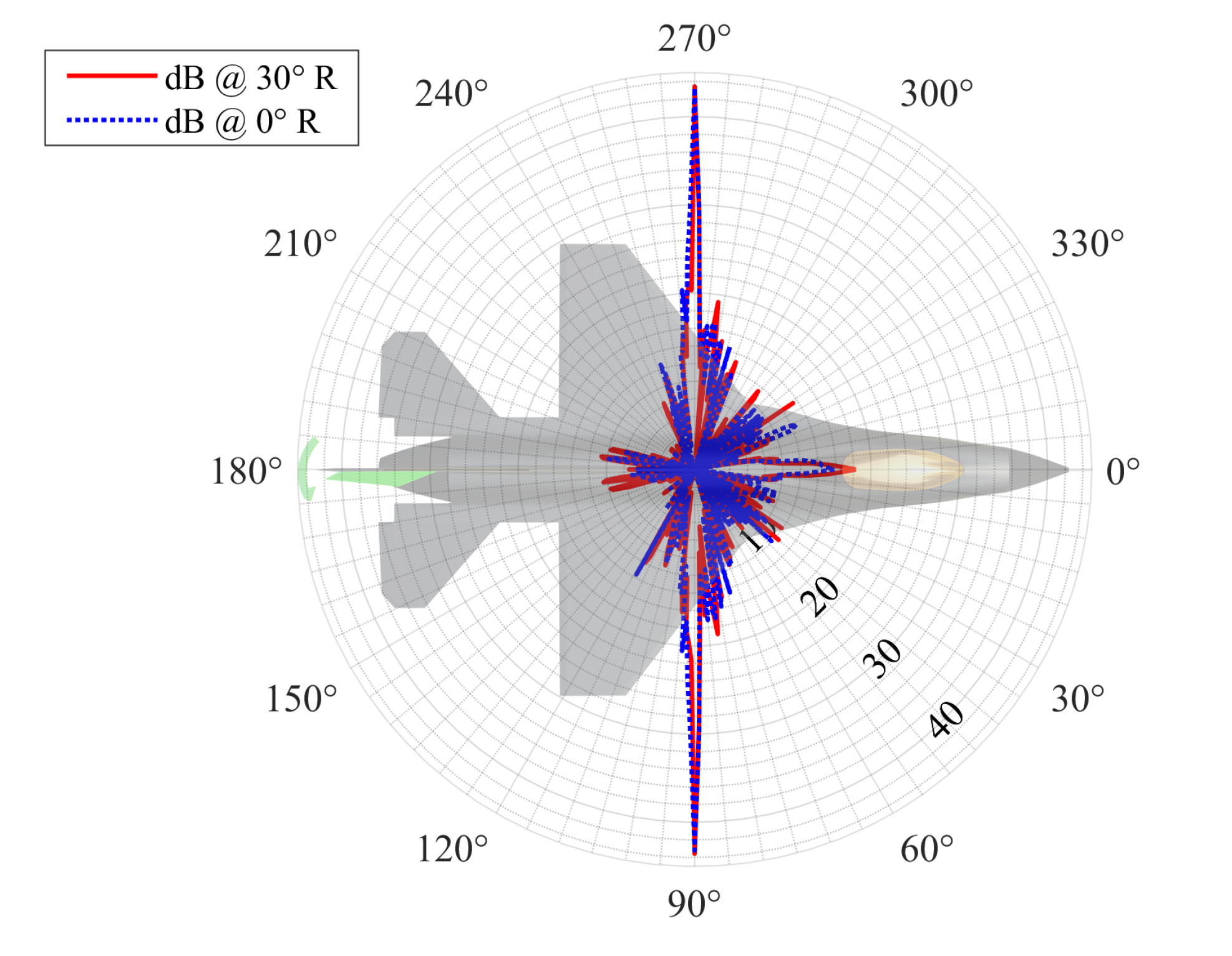

- By incorporating the effects of control surface deflections on RCS, the study ensures that these factors are properly accounted for in stealth maneuver planning. This integration enhances the realism of the model and improves the ability to generate effective stealthy maneuvers.

- The framework adapts in real time, dynamically adjusting flight maneuvers to maintain stealth characteristics. This real-time adaptability ensures that non-stealth platforms can continuously optimize their flight paths to minimize radar detectability while meeting operational constraints.

2. Problem Description and Preliminaries

2.1. Preliminaries

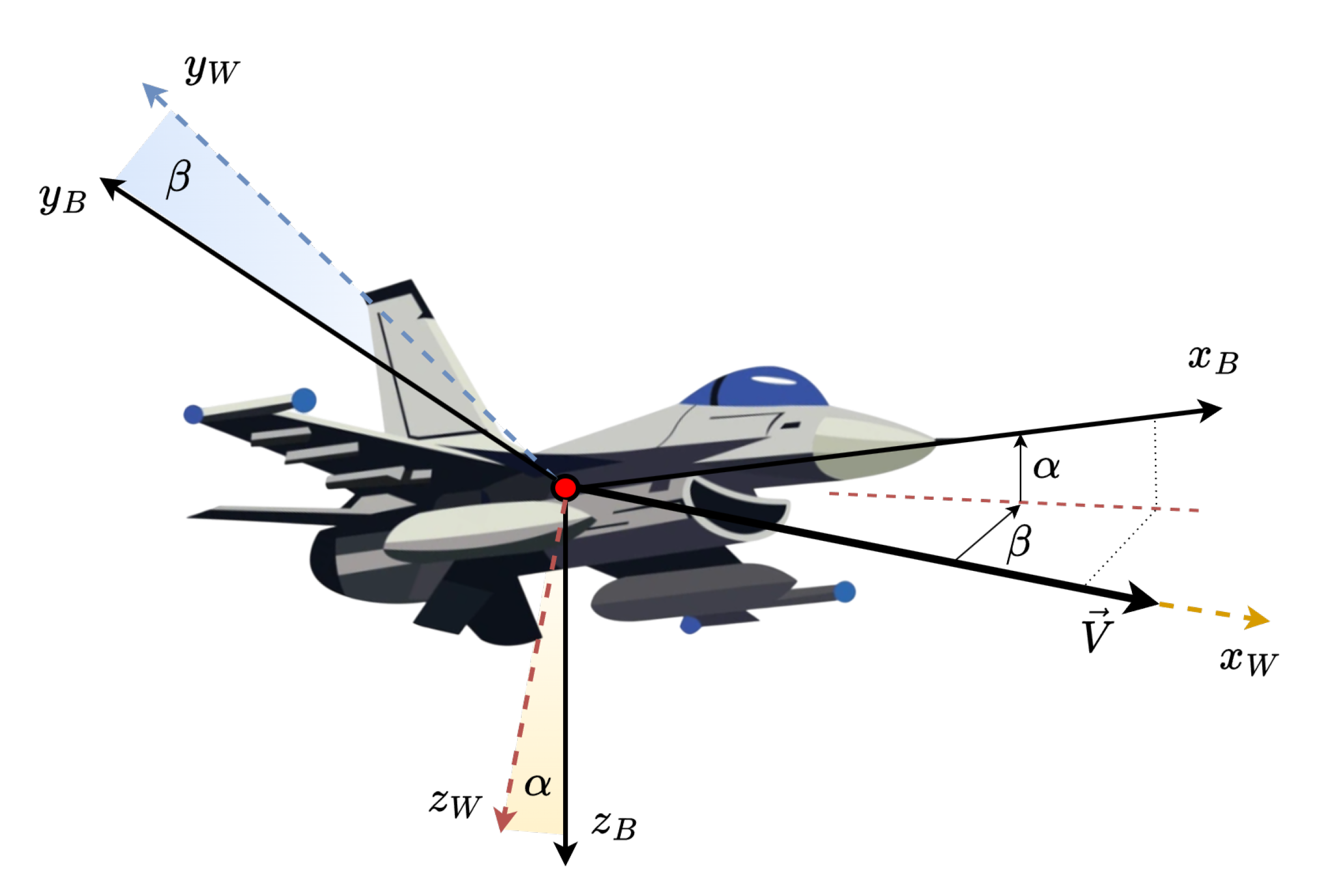

2.1.1. Flight Dynamics Model

Equations of motion

Aerodynamics & Actuators

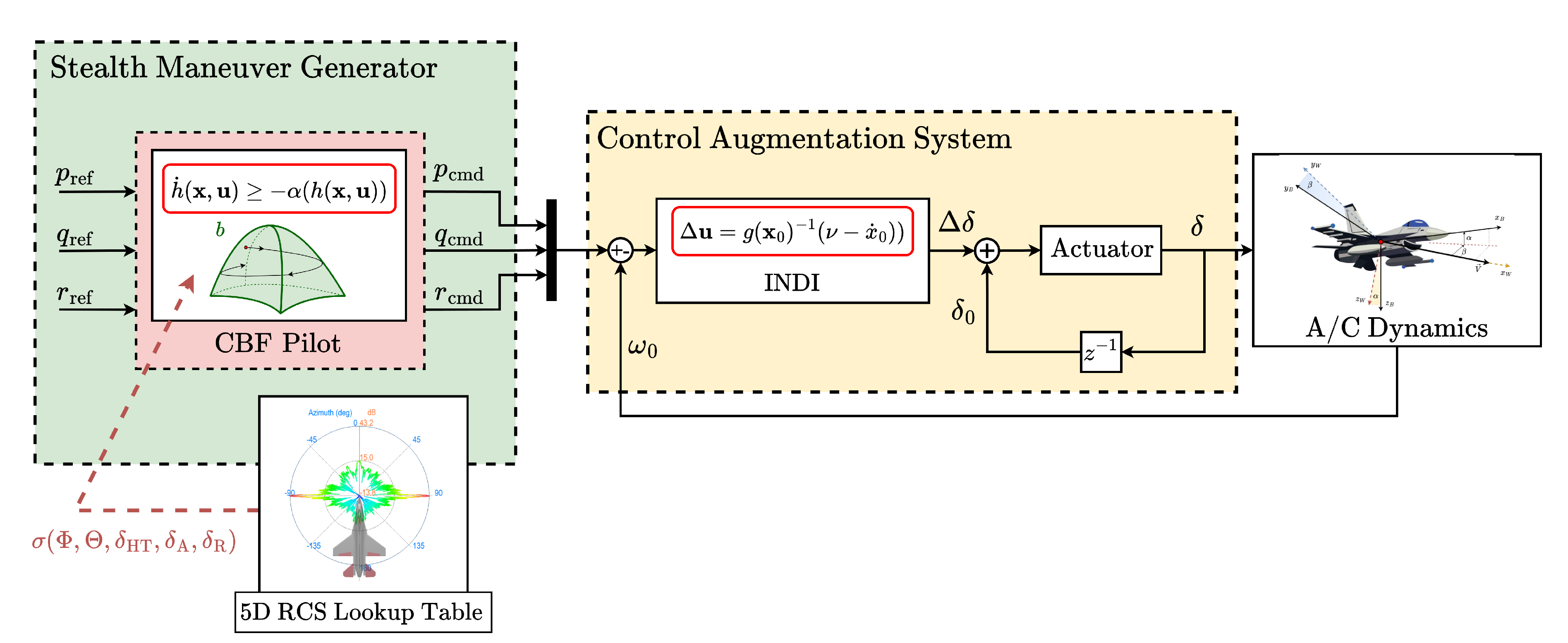

2.1.2. Flight Control Law Design

2.1.3. Control Barrier Functions

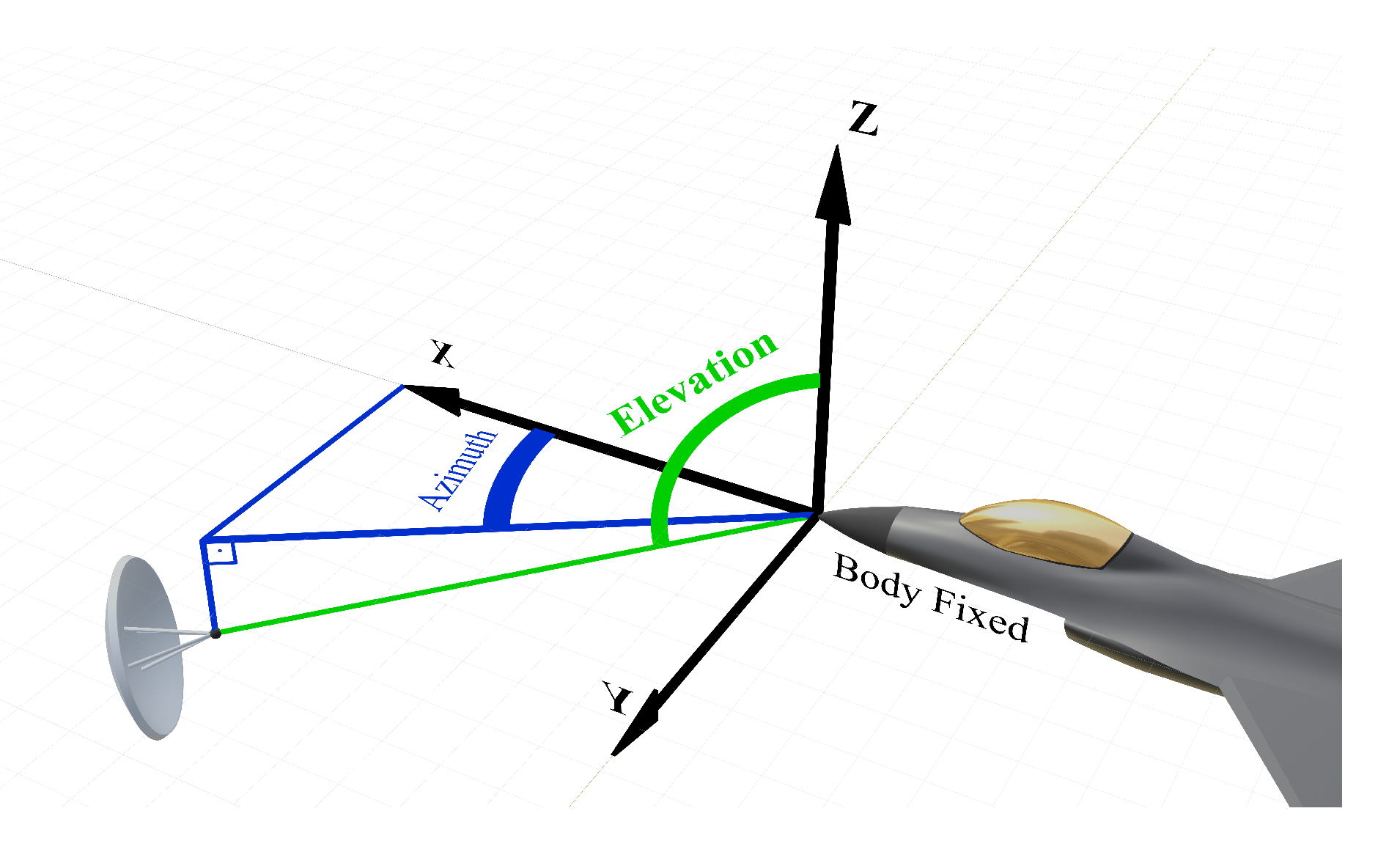

3. Radar Cross-Section Quantification

3.1. Methodology

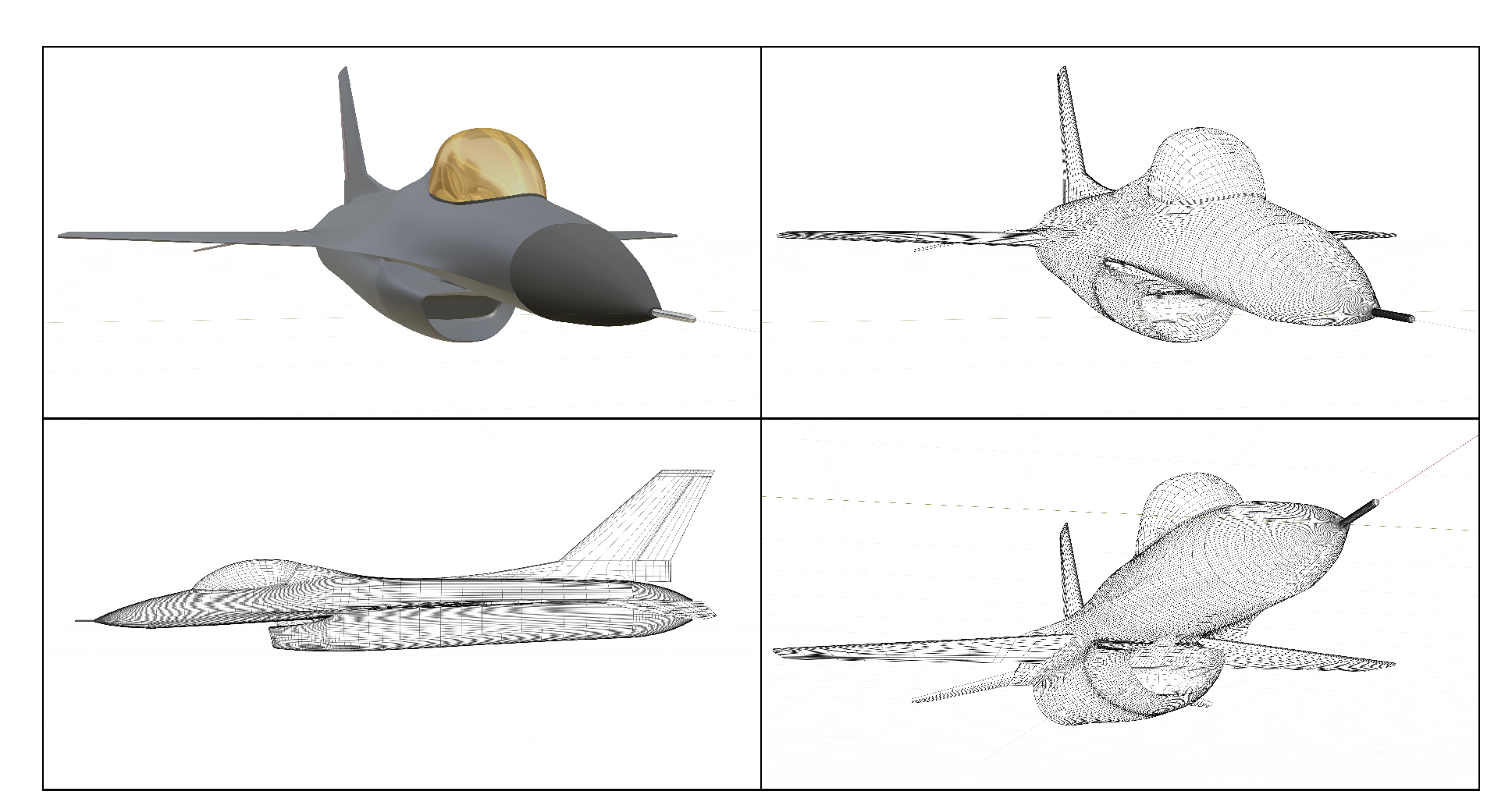

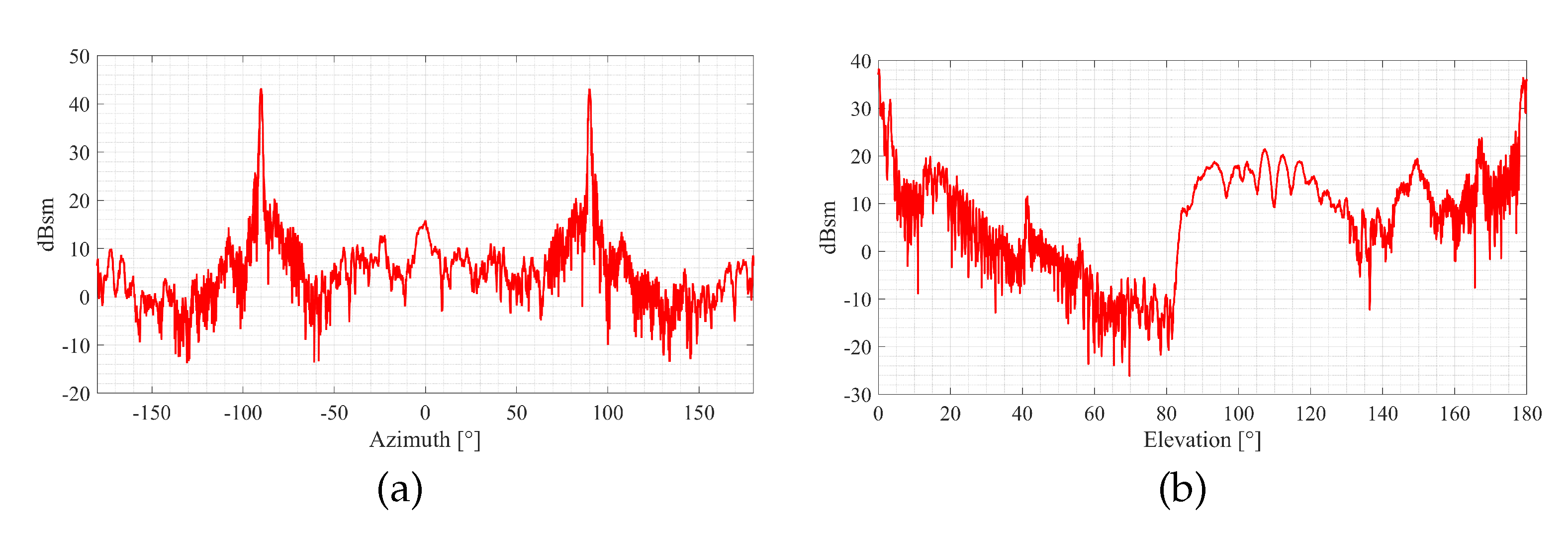

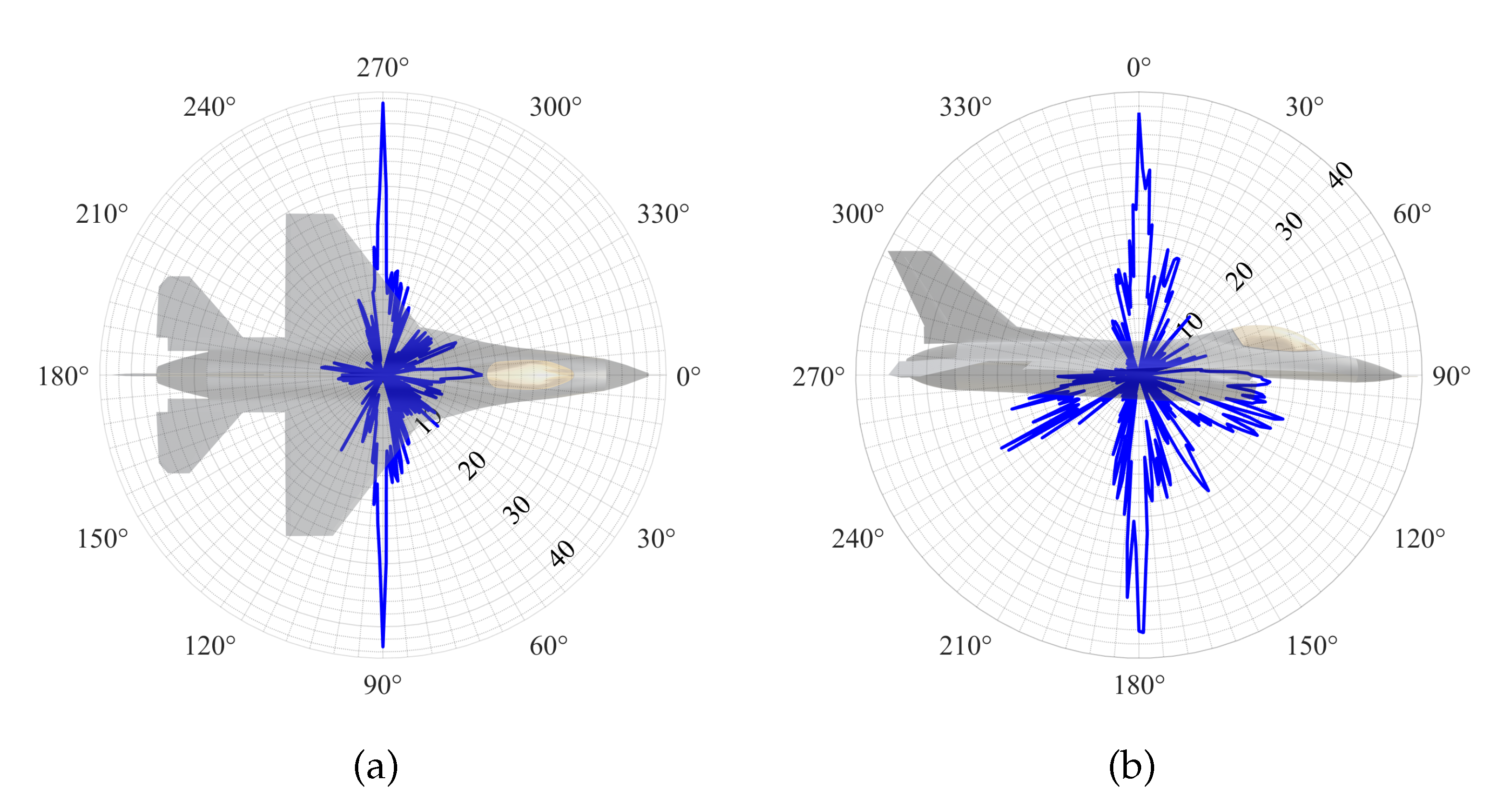

3.2. F-16 Radar Cross-Section Characteristics

4. Stealth-Maneuver Generator

5. Simulations and Results

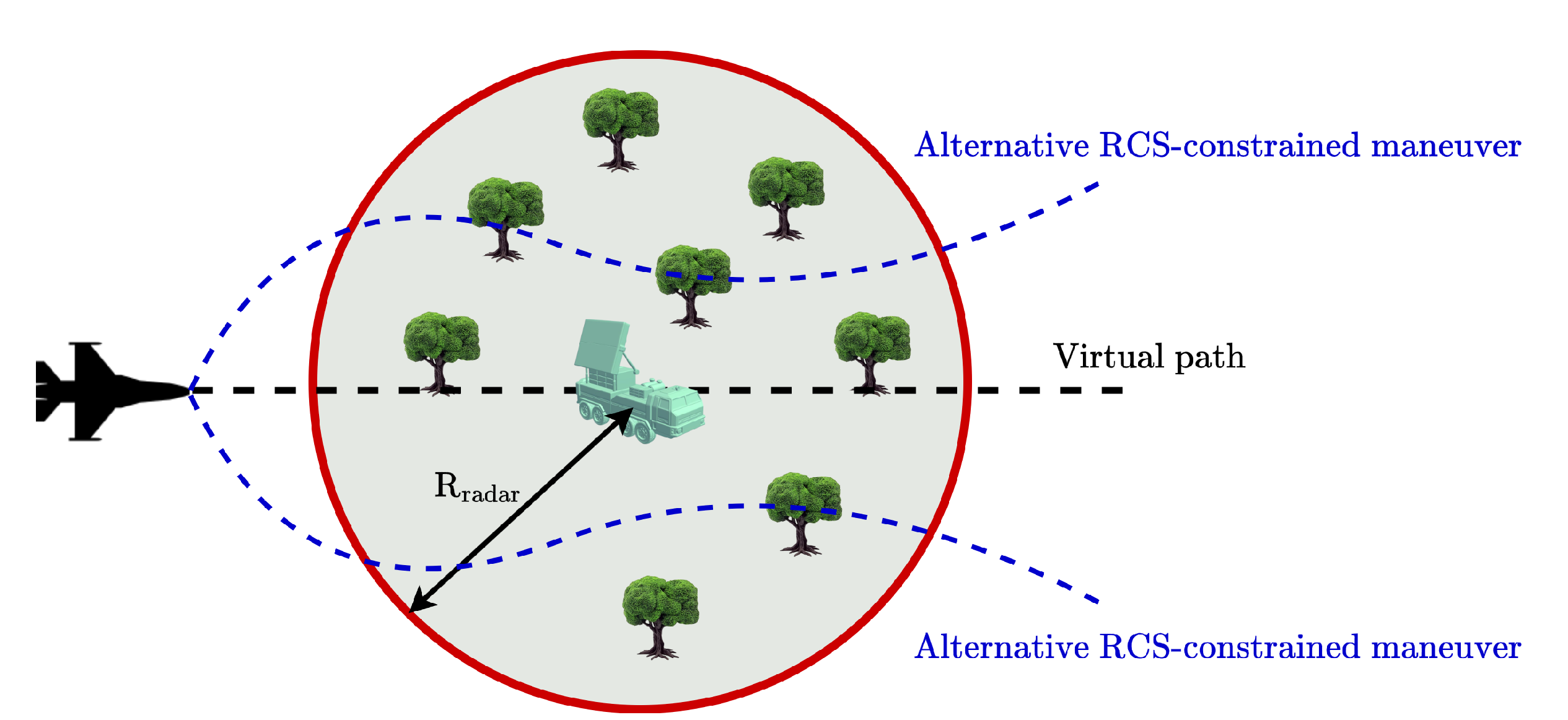

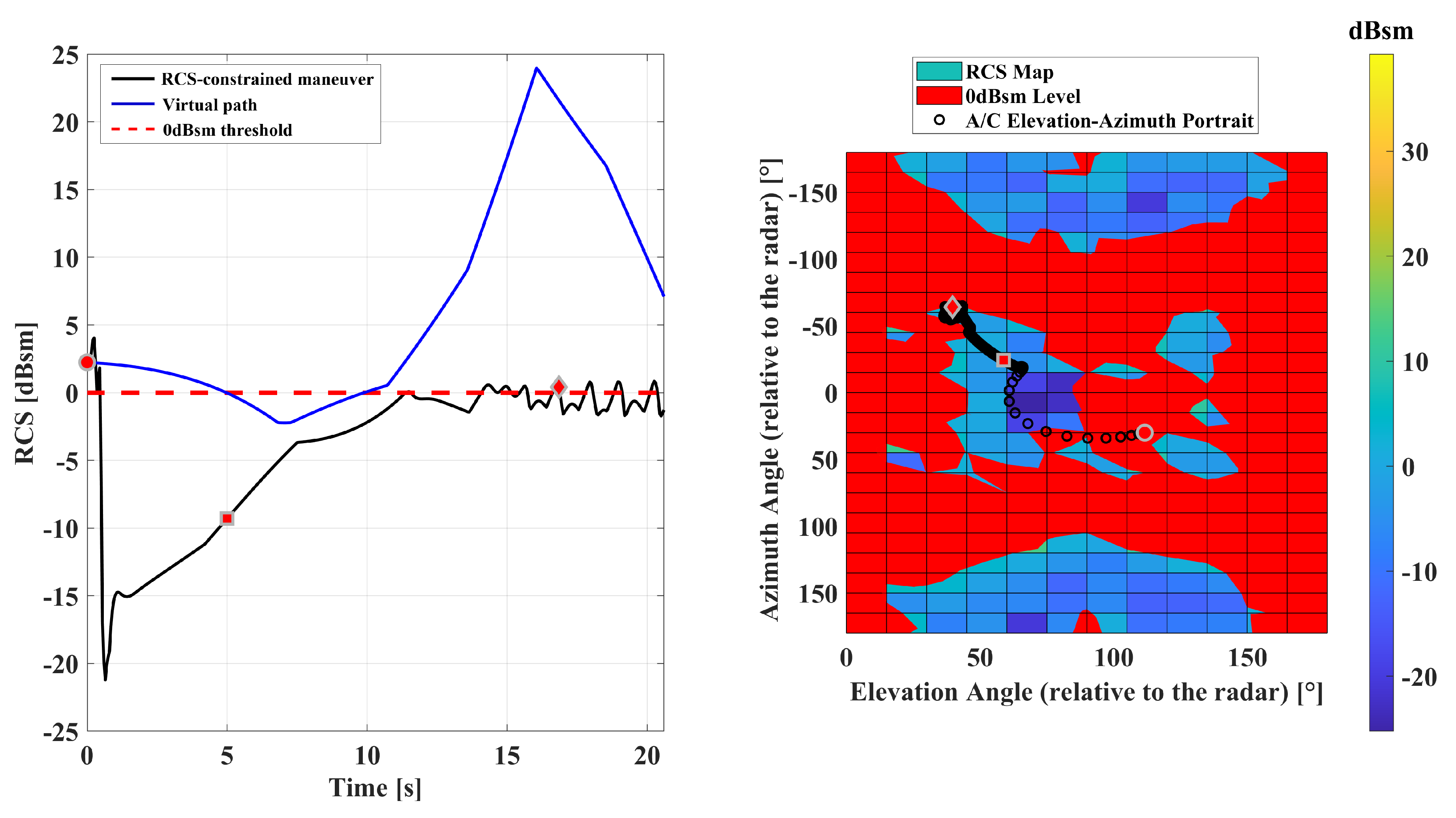

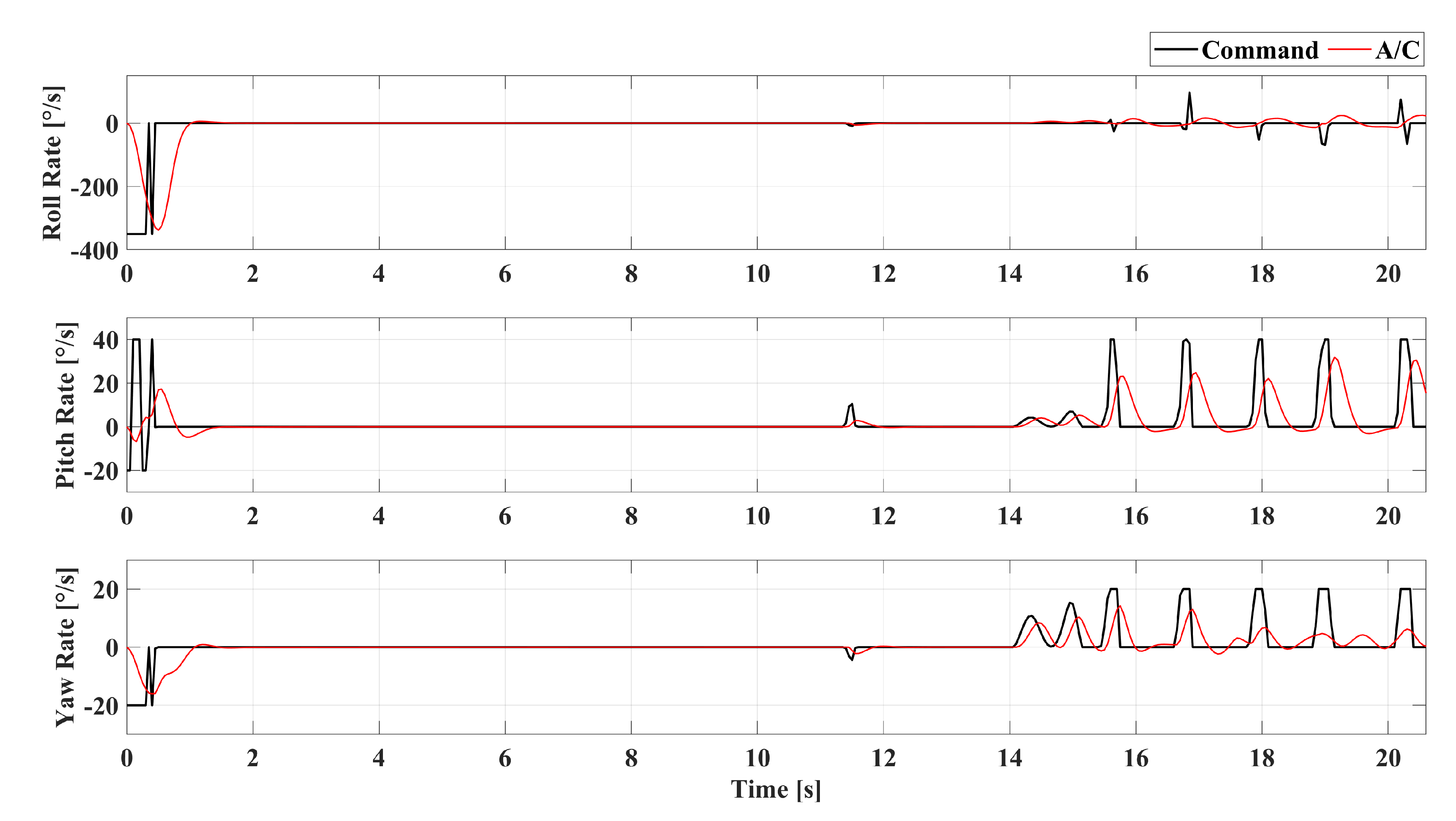

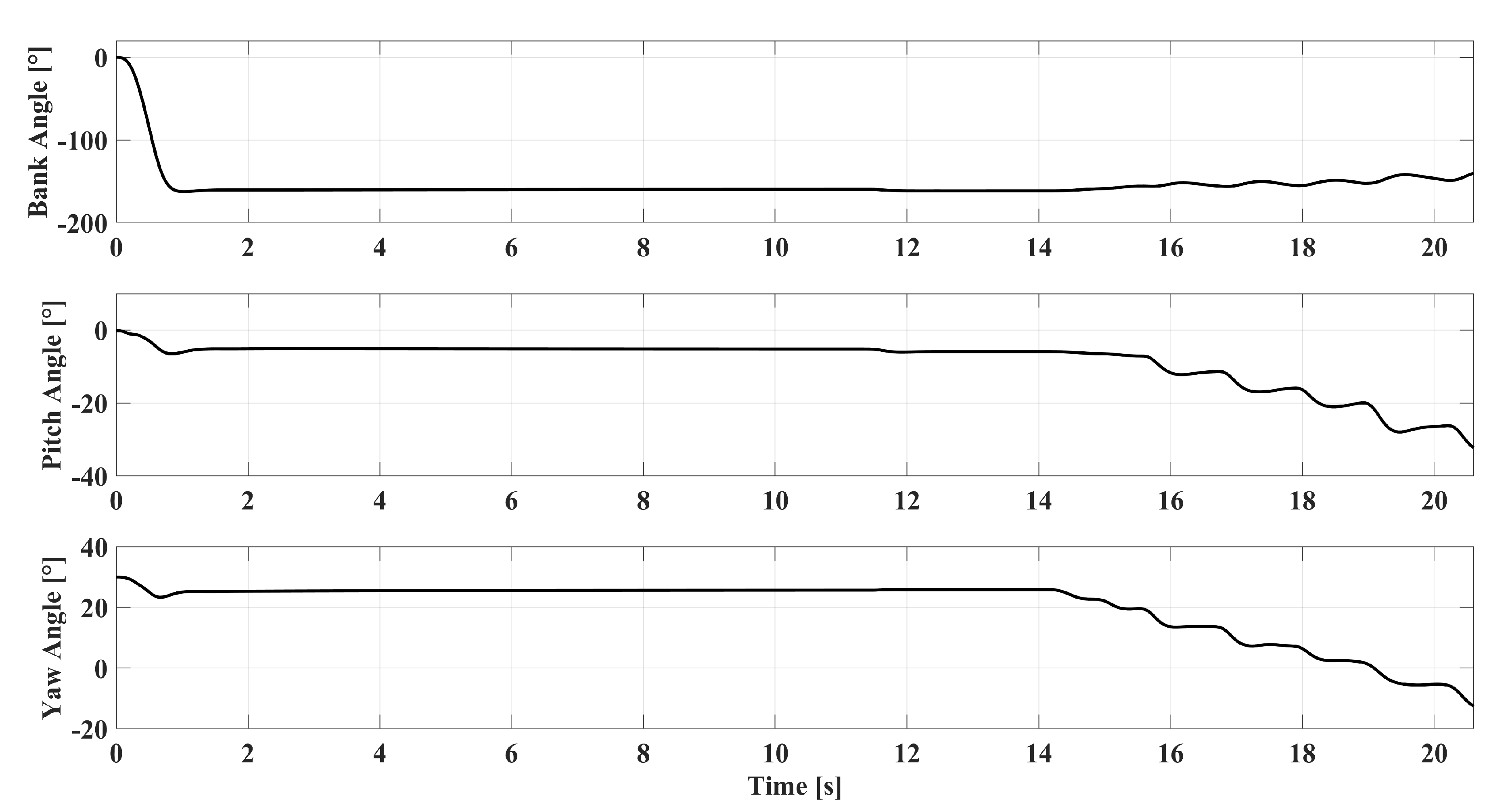

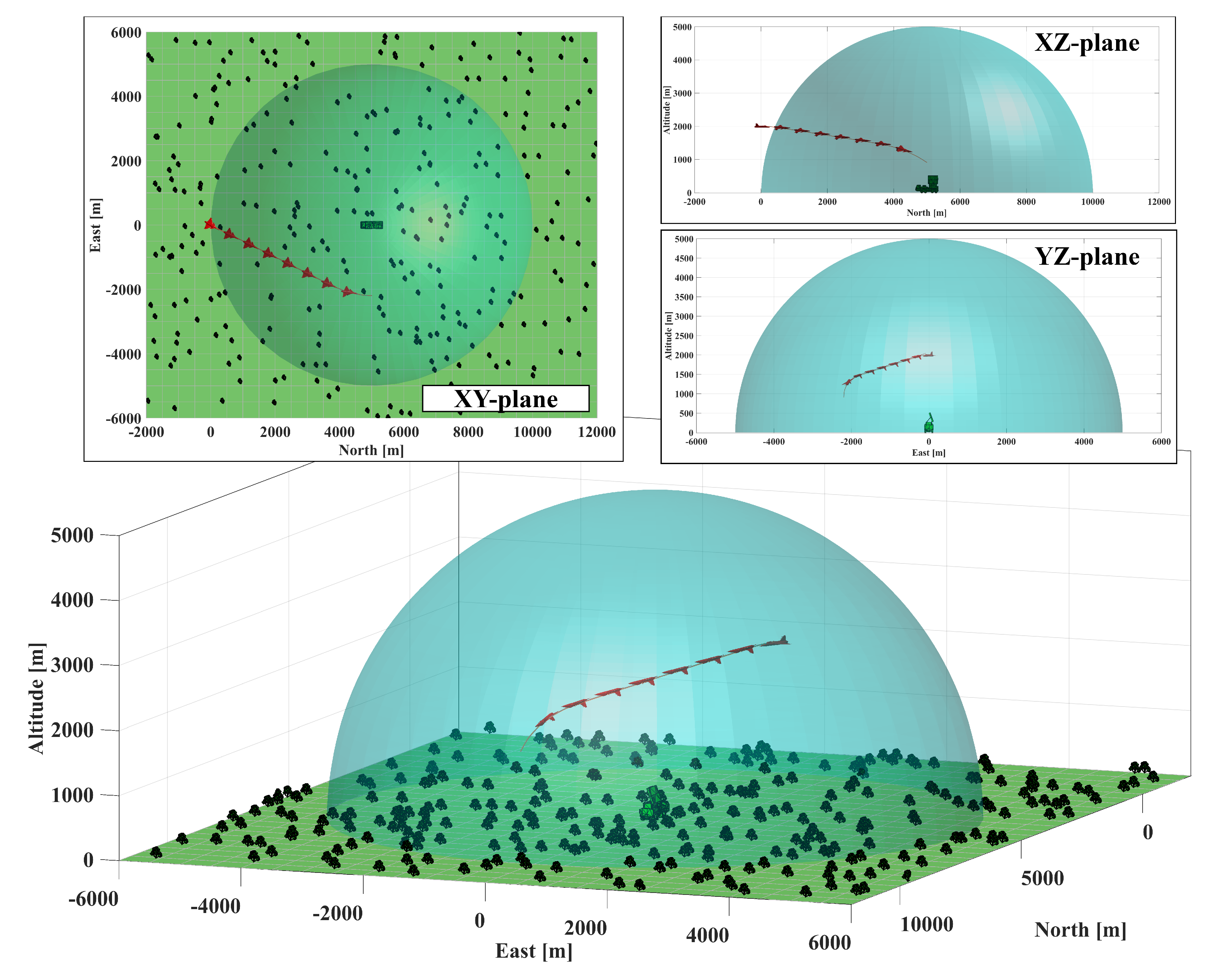

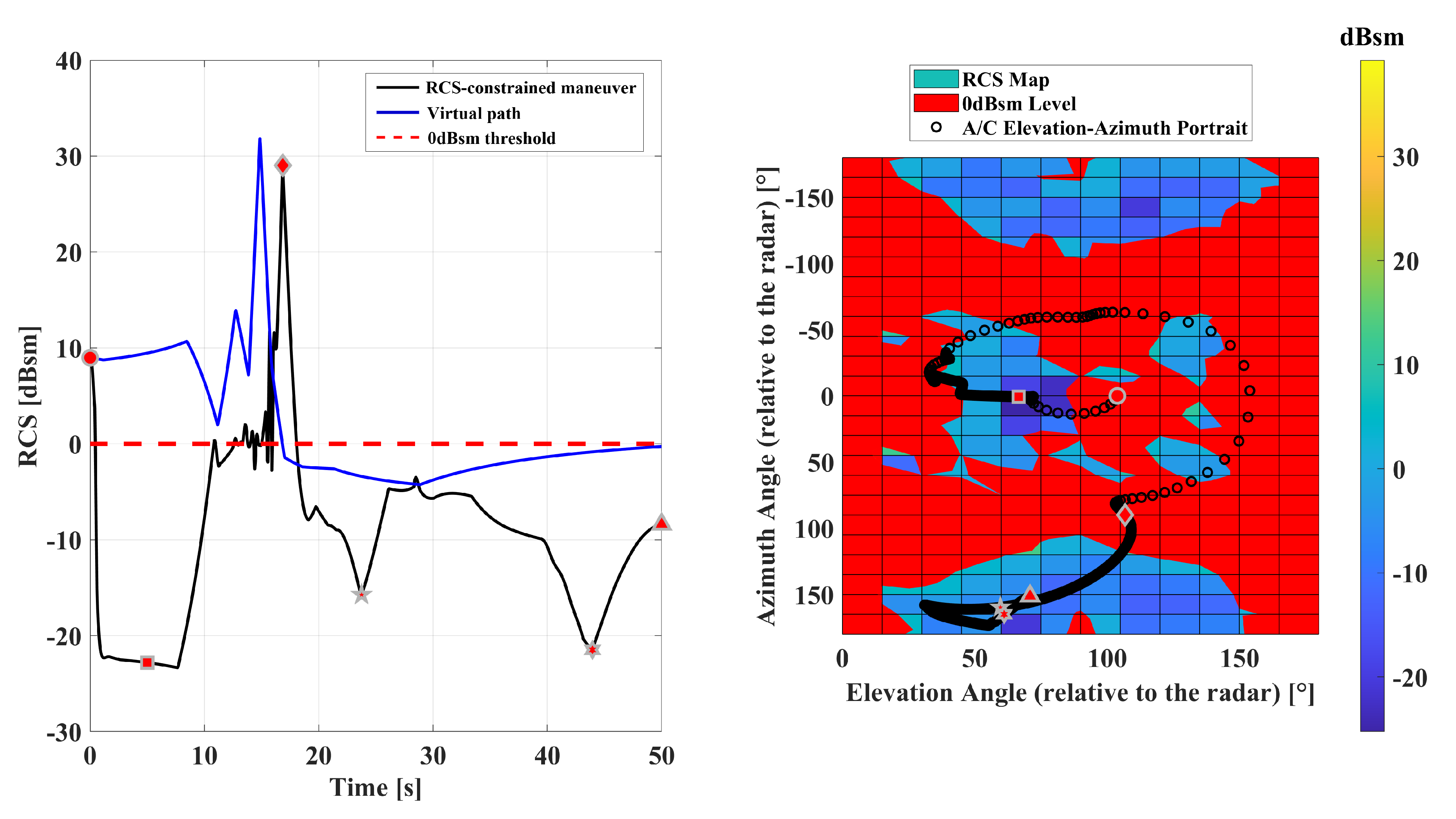

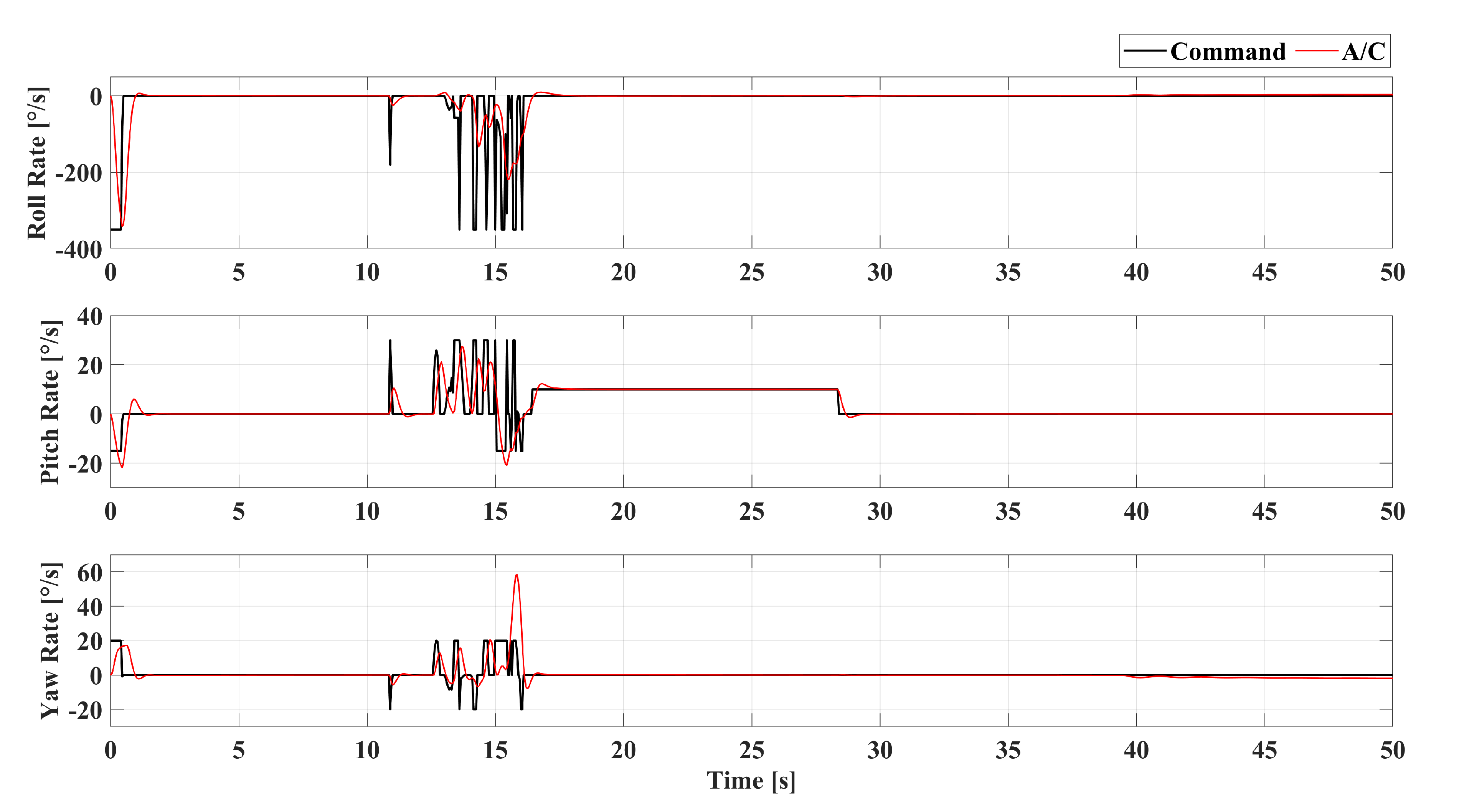

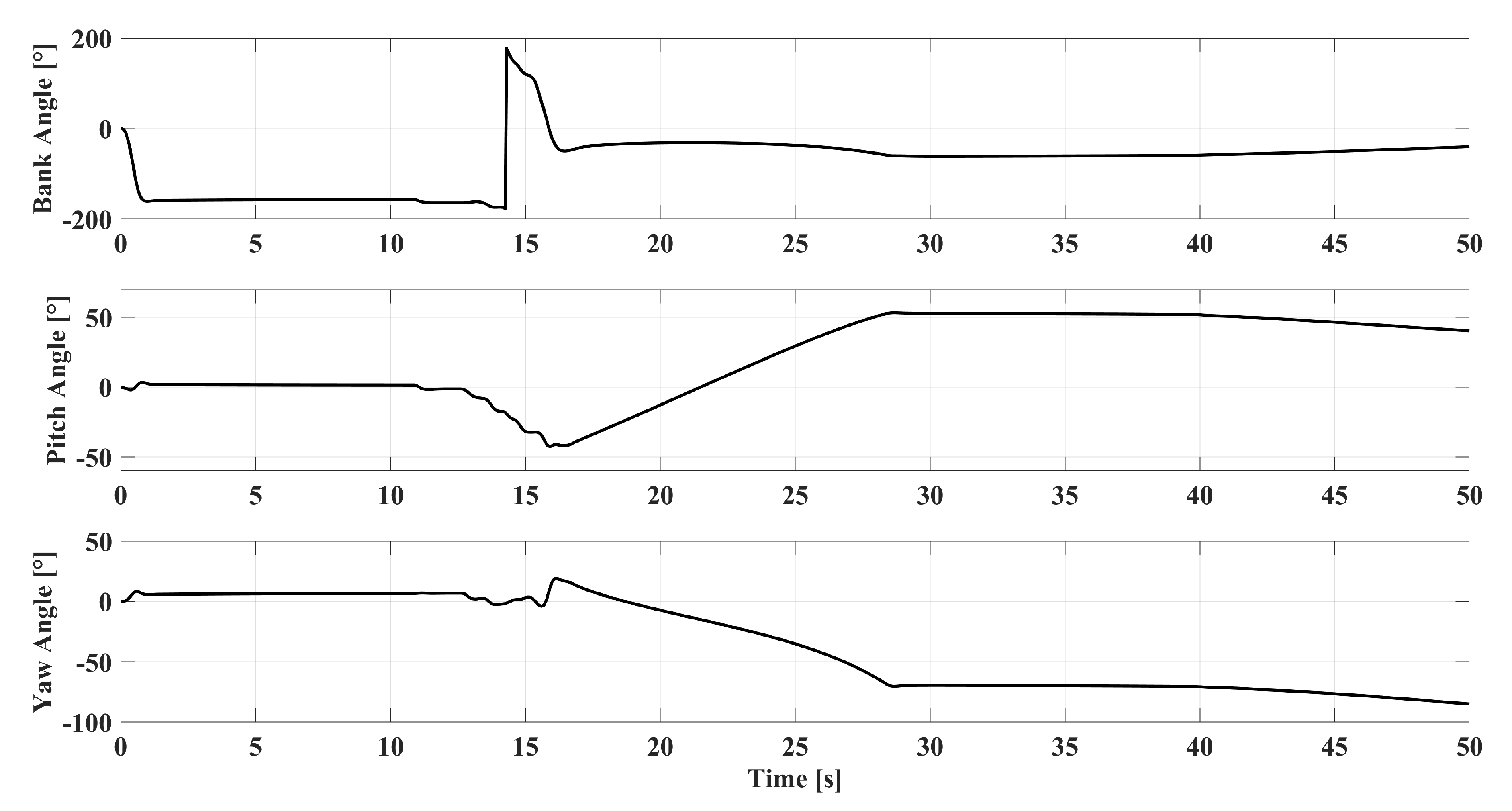

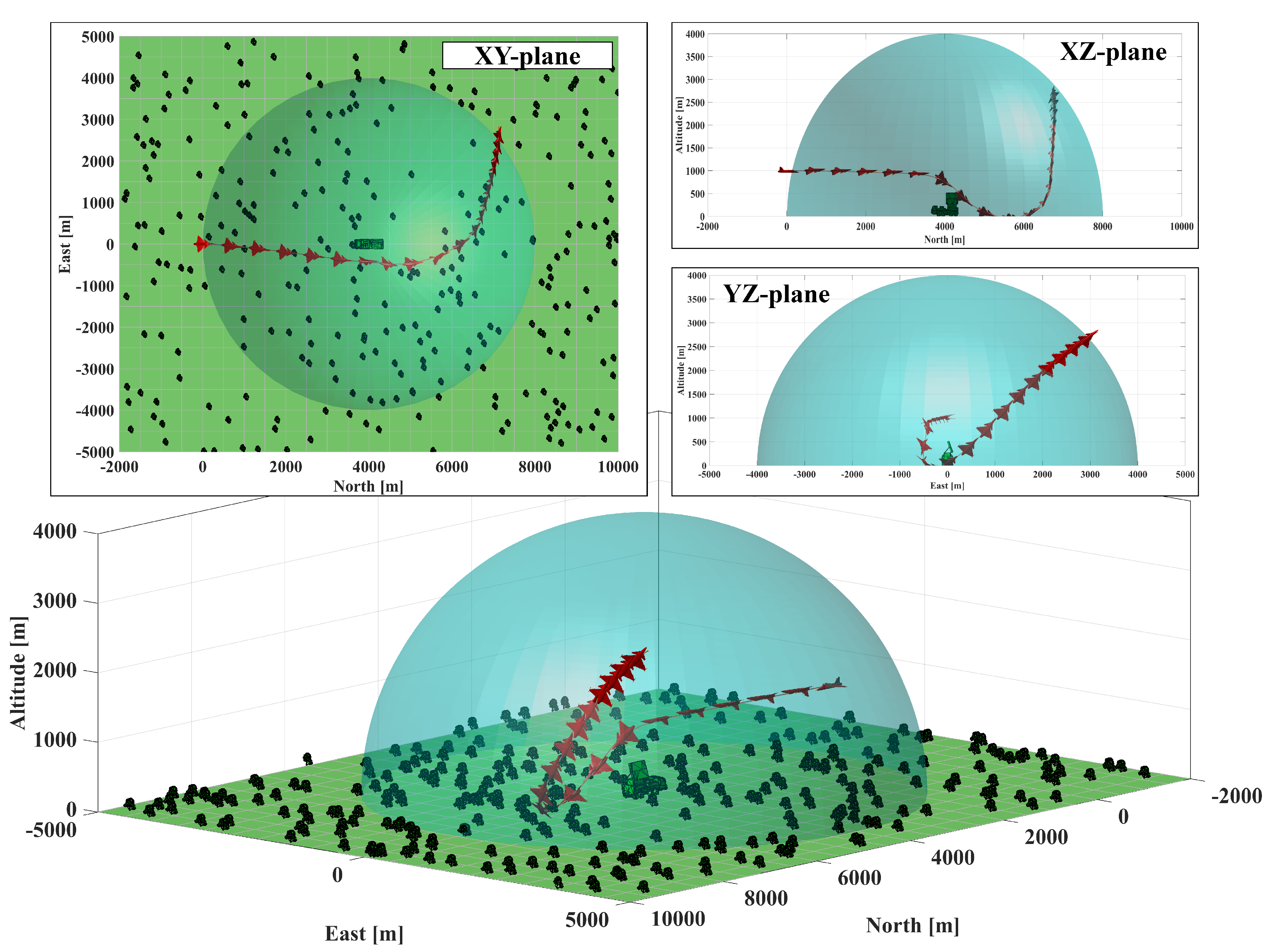

5.1. Scenario-1: Radar-Penetration Maneuver

5.2. Scenario-2: Radar-Evasive Maneuver

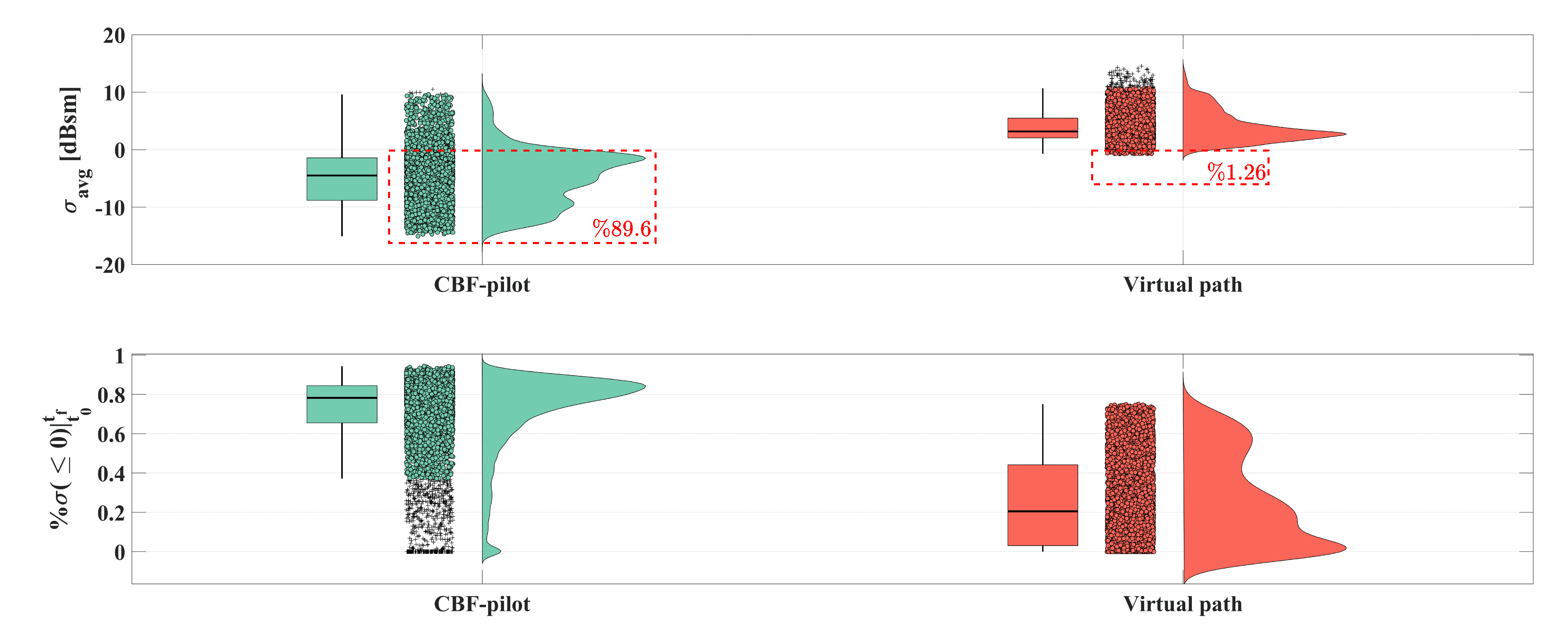

5.3. Monte Carlo Simulations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBF | Control barrier functions |

| INDI | Incremental nonlinear dynamic inversion |

| LO | Low-observability |

| RAM | Radar-absorbing material |

| RCS | Radar cross-section |

| UAV | Unmanned aerial vehicle |

| CAS | Control augmentation system |

References

- Paterson, J. Overview of low observable technology and its effects on combat aircraft survivability. Journal of Aircraft 1999, 36, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, F.W. Radar cross-section reduction via route planning and intelligent control. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 2002, 10, 696–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikidis, K.; Skondras, A.; Tokas, C. Low observable principles, stealth aircraft and anti-stealth technologies. Journal of Computations & Modelling 2014, 4, 129–165. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.H.A.; Shin, J.J.; Kim, J. Implementation and analysis of pattern propagation factor based radar model for path planning. Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems 2019, 96, 517–528. [Google Scholar]

- Norsell, M. Radar cross section constraints in flight-path optimization. Journal of aircraft 2003, 40, 412–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Wu, J.; Zhu, X. Efficient and optimal penetration path planning for stealth unmanned aerial vehicle using minimal radar cross-section tactics and modified A-Star algorithm. ISA transactions 2023, 134, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Huang, J.; Song, L.; Lu, X. Stealth Aircraft Penetration Trajectory Planning in 3D Complex Dynamic Environment Based on Sparse A* Algorithm. Aerospace 2024, 11, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, J.; Dai, J.; He, C. A novel real-time penetration path planning algorithm for stealth UAV in 3D complex dynamic environment. Ieee Access 2020, 8, 122757–122771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, J.; Dai, J.; He, C. Rapid penetration path planning method for stealth uav in complex environment with bb threats. International Journal of Aerospace Engineering 2020, 2020, 8896357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Zhai, J.; Xie, X.; Yin, H.; Zhu, Y. Machine learning-based modeling and uncertainty quantification for radar cross section of a cone-like target. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Power, Electronics and Computer Applications (ICPECA). IEEE; 2022; pp. 249–252. [Google Scholar]

- McFarland, M.B.; Zachery, R.A.; Taylor, B.K. Motion planning for reduced observability of autonomous aerial vehicles. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1999 IEEE International Conference on Control Applications (Cat. No. 99CH36328). IEEE, 1999, Vol. 1, pp. 231–235.

- Xu, Q.; Ge, J.; Yang, T.; Sun, X. A trajectory design method for coupling aircraft radar cross-section characteristics. Aerospace Science and Technology 2020, 98, 105653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Huang, J.; Guan, J.; Song, L. Stealth Aircraft Penetration Trajectory Planning in 3D Complex Dynamic Based on Radar Valley Radius and Turning Maneuver. Aerospace 2024, 11, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, J. Measuring low observable technology’s effects on combat aircraft survivability. In Proceedings of the 1997 World Aviation Congress; 1997; p. 5544. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Shen, L.; Chen, S. Low observability trajectory planning for stealth aircraft to evade radars tracking. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part G: Journal of Aerospace Engineering 2014, 228, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J. Modelling radar tracking features and low observability motion planning for UCAV. In Proceedings of the 2012 4th International Conference on Intelligent Human-Machine Systems and Cybernetics. IEEE, 2012, Vol. 2, pp. 162–166.

- Nguyen, L.T. Simulator study of stall/post-stall characteristics of a fighter airplane with relaxed longitudinal static stability; Vol. 12854, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 1979.

- Ames, A.D.; Coogan, S.; Egerstedt, M.; Notomista, G.; Sreenath, K.; Tabuada, P. Control barrier functions: Theory and applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 18th European control conference (ECC). IEEE; 2019; pp. 3420–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.; Sreenath, K. Exponential control barrier functions for enforcing high relative-degree safety-critical constraints. In Proceedings of the 2016 American Control Conference (ACC). IEEE; 2016; pp. 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovic, M.S.; Tasic, M.S.; Mrdakovic, B.L.; Kolundzija, B. WIPL-D: Monostatic RCS analysis of fighter aircrafts. In Proceedings of the 2016 10th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP). IEEE; 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

| (a) | (b) |

| (a) | (b) |

| (a) | (b) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).