Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

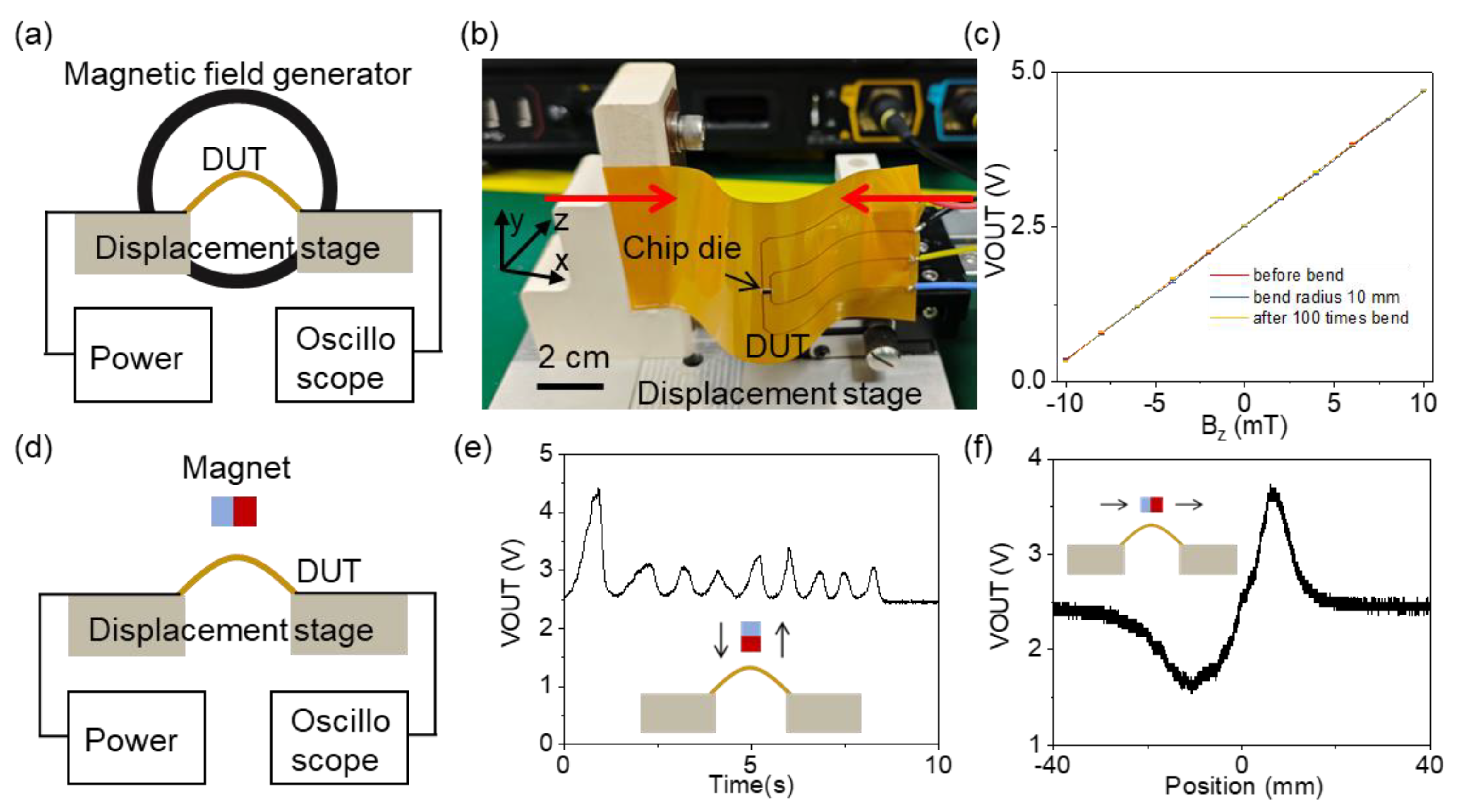

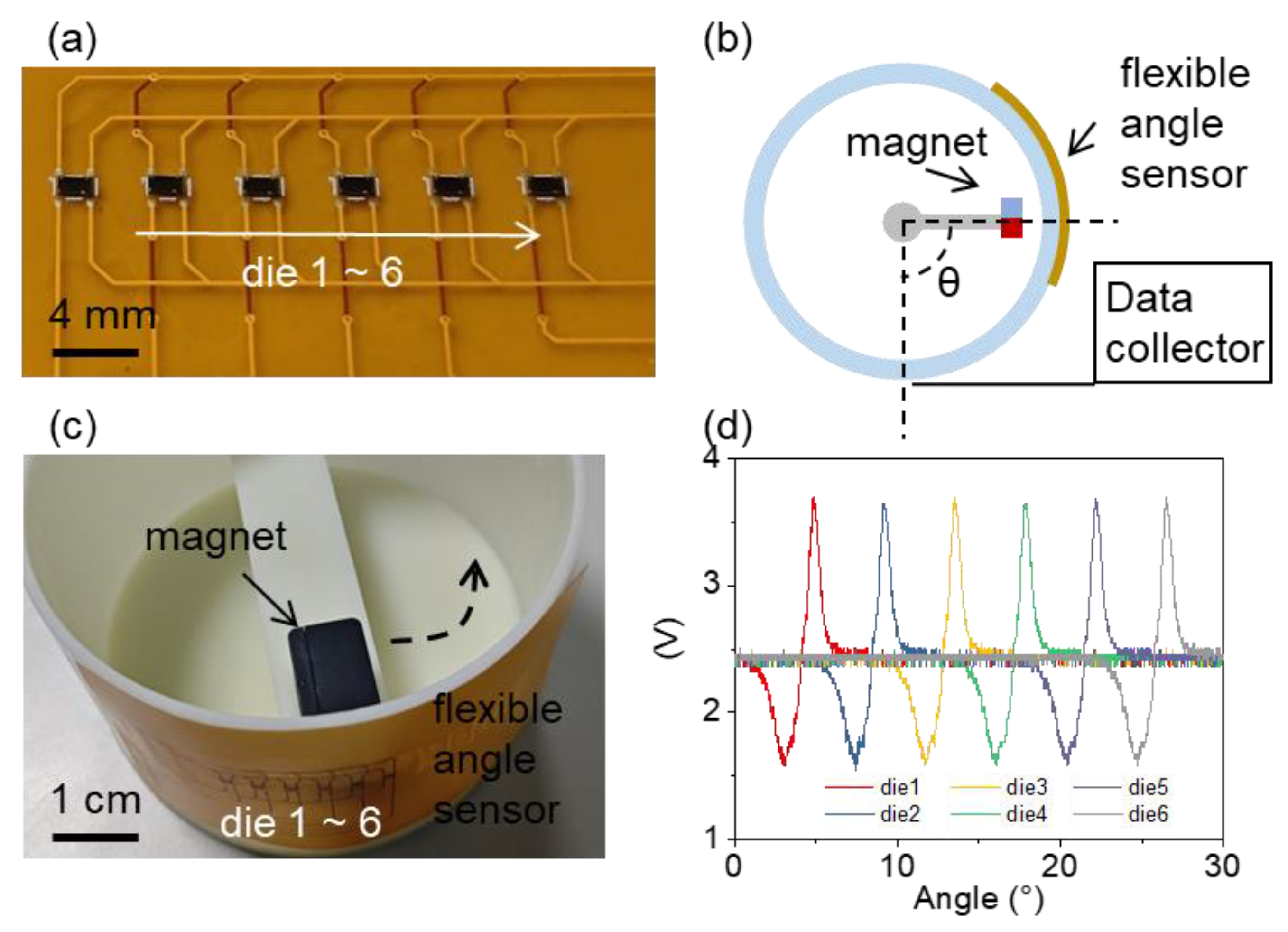

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

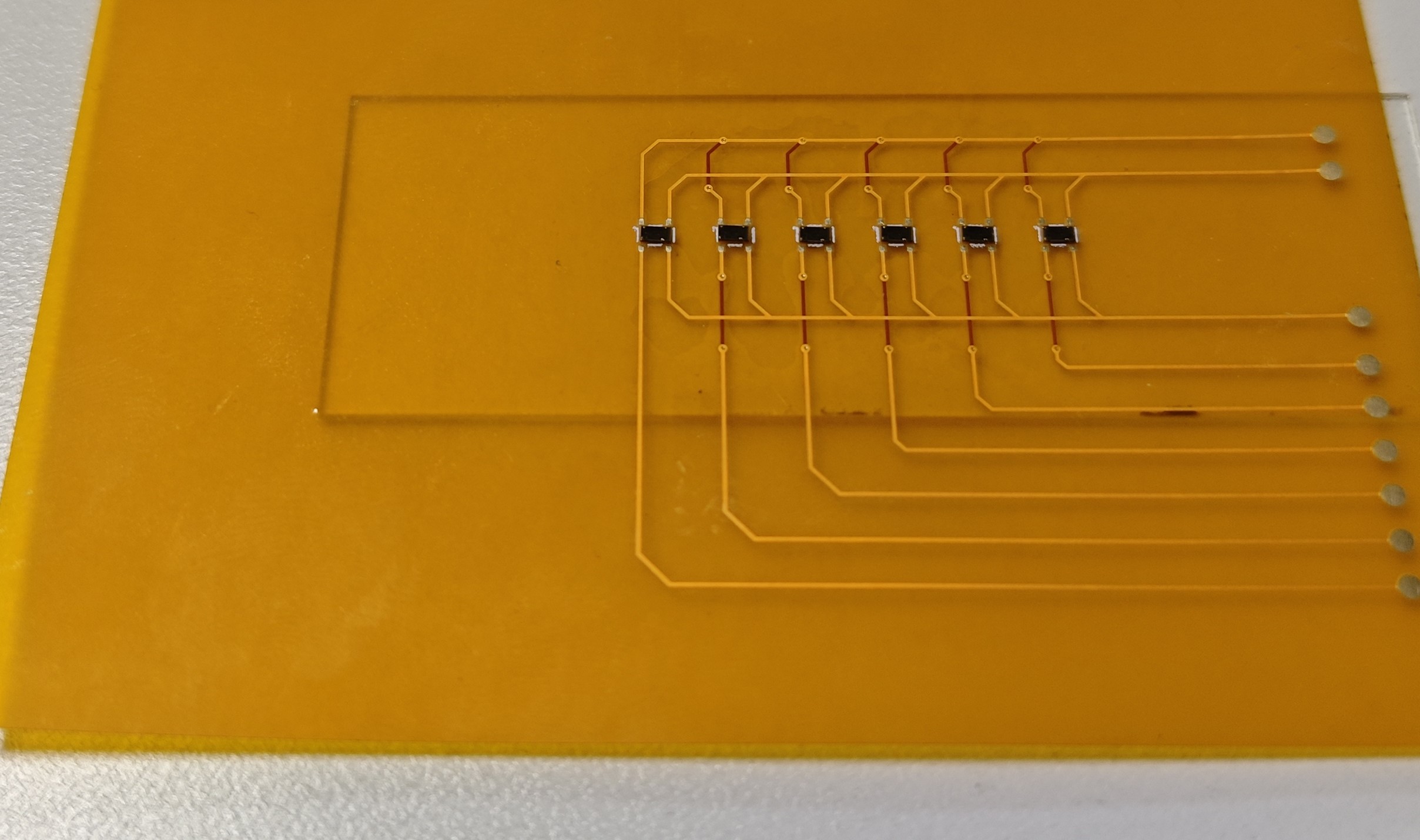

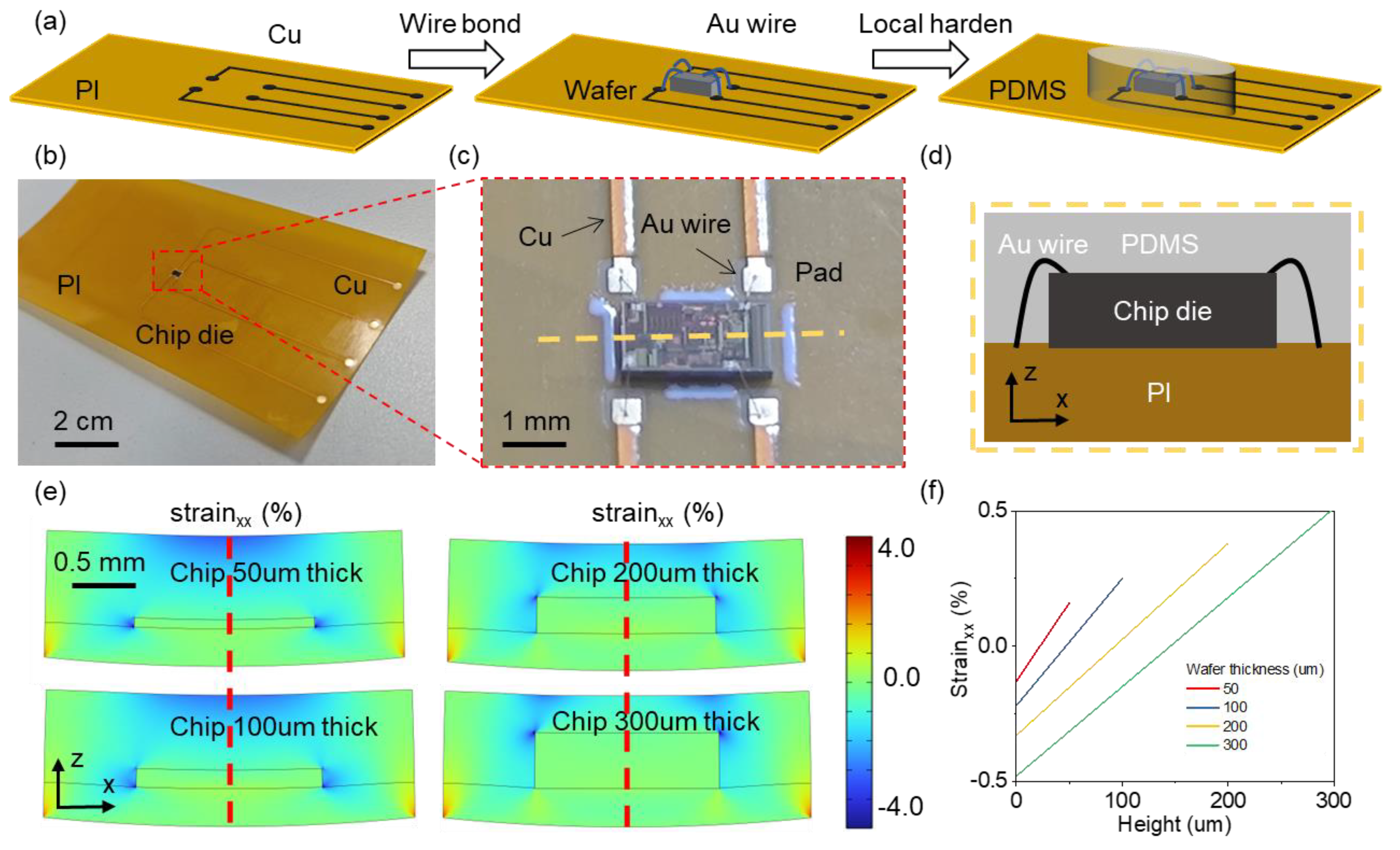

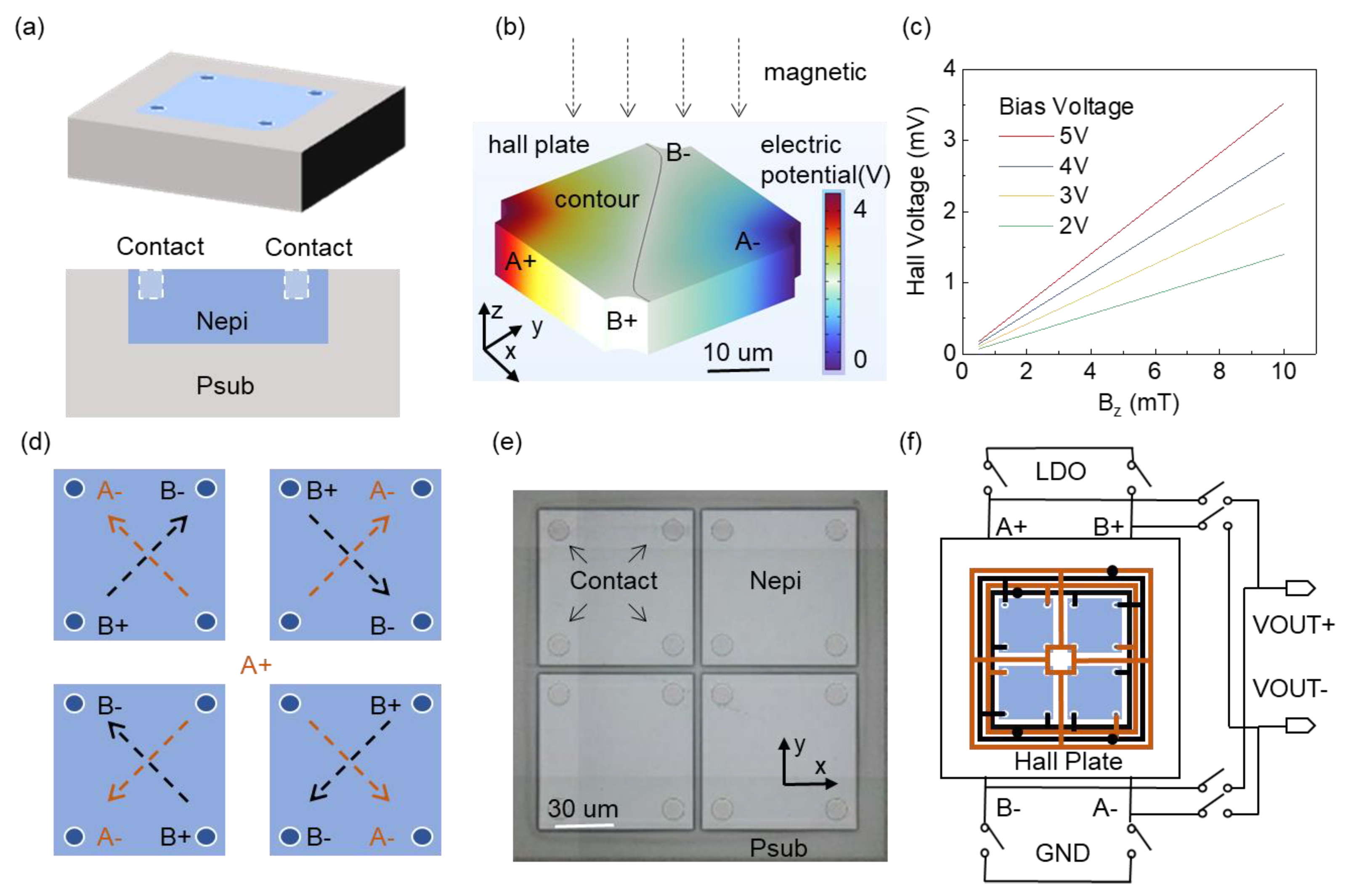

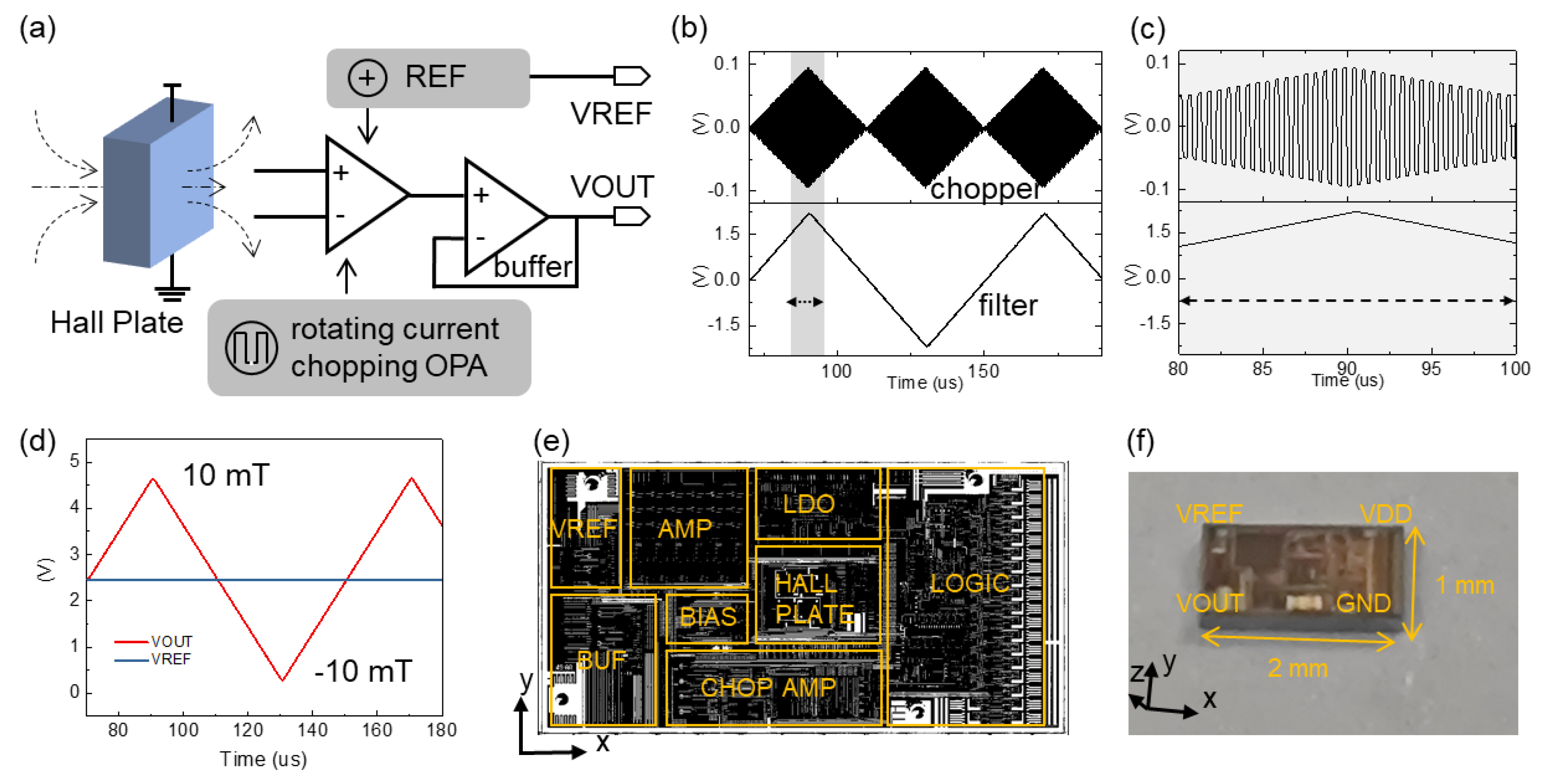

2. Design and Fabrication

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cao, B.; Lei, K.; Zou, H.; Martins, R.P.; Mak, P. Exploring the performance of hall sensor with substrate bias modulation in soi process. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 27365–27372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, T.T.H.; Trung, L.Q.; Kasai, N.; Le, M.; Luong, V.S. Development of differential hall sensors for pulsed eddy current testing using gaussian pulse excitation. Sens. Actuators, A. 2024, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibiino, G.P.; Marchesi, M.; Cogliati, M.; Syeda, S.F.; Romani, A.; Traverso, P.A.; Crescentini, M. Experimental evaluation of hall-effect current sensors in bcd10 technology. Meas. 2023, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, D.; Jeong, M.; Kang, D. Research on hall sensor fault diagnosis and compensation method to improve motor control reliability. J. Magn. 2018, 23, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Otsuki, M.; Tanaka, M. Measurement of finger joint angle using a flexible polymer sensor. Int. J. Appl. Electromagn. Mech. 2016, 52, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.G.; Wang, X.J.; Li, M.H.; Gao, Y.; Hu, Z.Q.; Nan, T.X.; Sun, N.X. Highly sensitive flexible magnetic sensor based on anisotropic magnetoresistance effect. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 9370–9379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wouters, C.; Vrankovic, V.; Roessler, C.; Sidorov, S.; Ensslin, K.; Wegscheider, W.; Hierold, C. Design and fabrication of an innovative three-axis hall sensor. Sens. Actuators, A. 2016, 237, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masias, A.; Marcicki, J.; Paxton, W.A. Opportunities and challenges of lithium ion batteries in automotive applications. ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, S.; Yenuganti, S.; Manuvinakurake, M. Fabrication and testing of a hall effect based pressure sensor. Sens. Rev. 2022, 42, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, K.; Okada, I.; Shibasaki, I. High sensitivity hybrid hall effect ics with thin film hall elements. Sens. Mater. 2002, 14, 253–261. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, Y.; Cheng, T.; Tsai, Y. Flexible printed circuit board strain sensor embedded in a miniaturized pneumatic finger. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 22456–22463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.Q.; Guo, X.H.; Zhang, T.X.; Mu, S.W.; Wu, F.; Yan, Z.H.; Zhao, Y.N. Flexible strain sensor based on nickel microparticles/carbon black microspheres/polydimethylsiloxane conductive composites for human motion detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2024, 16, 32702–32712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Park, Y.J.; Chen, X.; Das, T.; Kim, M.S.; Ahn, J.H. Graphene based flexible and stretchable electronics. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 4184–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.T.; Guo, R.; Tay, B.K.; Yan, X.B. Flexible ferroelectric devices: Status and applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, M.; Kim, I.; Lee, H. Flexible and stretchable optoelectronic devices using silver nanowires and graphene. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 4541–4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnaushenko, D.; Makarov, D.; Stöber, M.; Karnaushenko, D.D.; Baunack, S.; Schmidt, O.G. High performance magnetic sensorics for printable and flexible electronics. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 880–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.L.; Liu, M.; Ma, R.; Zhang, R.Y.; Zhang, W.Q.; Yu, D.P.; Wang, H. Mechanical strain-tunable microwave magnetism in flexible cufe2o4 epitaxial thin film for wearable sensors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.L.; Li, S.B.; Wu, Y.Z.; Bao, X.L.; Xiang, Z.Y.; Xie, Y.L.; Li, R.W. Advances in flexible magnetosensitive materials and devices for wearable electronics. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y.P.; Zhang, F.J.; Huang, D.Z.; Di, C.A.; Zhu, D.B. Sensitive flexible magnetic sensors using organic transistors with magnetic-functionalized suspended gate electrodes. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 7979–7985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wei, Y.; Qiu, J. How far for the electronic skin: From multifunctional material to advanced applications. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.; Zhu, Y.; Li, M.; Fan, X.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y. Skin comfort sensation with mechanical stimulus from electronic skin. Mater. 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Ding, C.; Li, L.; Tian, B. The design of decoupled robotic arm based on chain transmission. Mach. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, W.; Li, S.; Jiang, Y.; Zang, W.; Fu, W.; Zhang, L. A soft mimic robotic arm powered by dielectric elastomer actuator. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Sun, C.; Ma, H.; Wei, M.; Li, J.; Jian, J.; Li, L. Flexible passive integrated photonic devices with superior optical and mechanical performance. Opt. Express. 2022, 30, 26534–26543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Sun, C.; Wei, M.; Ma, H.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, L. Integrated flexible microscale mechanical sensors based on cascaded free spectral range-free cavities. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 8898–8906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morvic, M.; Betko, J. Planar hall effect in hall sensors made from inp/ingaas heterostructure. Sens. Actuators, A. 2005, 120, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lalwani, A.V.; Arora, K.; Zheng, Z.; Renteria, A.; Senesky, D.G.G.; Wang, P. Hall-effect sensor design with physics-informed gaussian process modeling. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 22519–22528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paun, M.A.; Sallese, J.M.; Kayal, M. Hall effect sensors design, integration and behavior analysis. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2013, 2, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riem, R.; Raman, J.; Rombouts, P. A 2 ms/s full bandwidth hall system with low offset enabled by randomized spinning. Sens. 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeley, A.D.; Hobbs, M.J.; Willmott, J.R. Zero drift infrared radiation thermometer using chopper stabilised pre-amplifier. Appl. Sci.-Basel. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuda, Y. A 5. 6 nv/√hz chopper operational amplifier achieving a 0.5 μv maximum offset over rail to rail input range with adaptive clock boosting technique. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits. 2016, 51, 2119–2128. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, J.Y.; Lee, Y.; Lee, T. Skin mountable functional electronic materials for bio-integrated devices. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donolato, M.; Tollan, C.; Porro, J.M.; Berger, A.; Vavassori, P. Flexible and stretchable polymers with embedded magnetic nanostructures. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).