1. Introduction

The brown macroalgal genus

Sargassum (Sargassaceae, Fucales) is one of the most important habitat-forming taxa of shallow coastal environments, occurring along the tropical and warm temperate regions worldwide [

1].

Sargassum beds represent several resources for benthic communities, such as food and space for reproduction, nursery, and protection [

2,

3]. Considering the actual scenario regarding climate and oceanographic events, a deep understanding of the photosynthetic performance of

Sargassum under the impact of increasing surface seawater temperatures (SST) is critical for forecasting their responses undergoing global warming, providing better conservation procedures. Observed current ecosystems disruptions, due to global climate changes or local anthropogenic disturbances, deeply affect the survivorship, growth, reproduction, and distribution of marine organisms [

4], particularly for sessile life on shallow rocky bottoms, such as macroalgae [

5].

There are relevant laboratory and field studies on the effects of temperature and other abiotic factors on the physiology and growth of

Sargassum species from different regions, at short temporal scales [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. These studies indicate a negative effect of increasing temperature on

Sargassum species, particularly temperatures above 30°C for species in warm-temperate regions and 33°C for tropical species [

10,

11]. The negative effects of increased temperatures on

Sargassum populations are reported by long-term studies. For instance, the frequency of occurrence and the relative cover of

Sargassum from populations subjected to heated effluent declined after more than two decades of operation of the Brazilian Nuclear Power Station (BNPS). Yet, the abundance of other brown algal species from that region,

Padina gymnospora (Dictyotales), remained high during the same period [

12,

13]. The decline and disappearance of

Sargassum and other Fucales subjected to increasing temperatures are described for other regions of the world [

14,

15]. Elevated seawater temperature directly or indirectly alters the photosynthetic performance of algae [

16], affecting their primary production.

Photosynthesis is highly sensitive to high temperatures and is often inhibited before other cellular functions are impaired due to damage to the PSII and inhibition of Rubisco activity [

17,

18,

19,

20] Wang et al., 2018). The effects of increasing temperature, as well as the combined effects of temperature and irradiance on photosynthetic activity and thermal tolerance of different

Sargassum species have been described using the pulse amplitude modulated (PAM) fluorometry technique in several studies [

7,

10,

21,

22,

23,

24]. The technique allows instantaneous and non-intrusive measurement of photosynthetic activity in real-time. Besides the maximum quantum yield (

Fv/Fm) being used as an indicator of environmental stress [

25,

26], the induction of Rapid Light Curves (RLC) allows an evaluation of the temperature effect on photosynthetic parameters, such as photosynthetic efficiency (α), maximum electron transport rate (rETR

m) and minimum irradiance for photosynthesis saturation (E

k) [

27]. RLC measures the effective quantum yield as a function of irradiance. An important piece of information provided by this technique is to estimate the working of a photoprotection mechanism that results in a dissipation of part of the light energy absorbed by PSII antenna in the form of heat, the non-photochemical quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence (NPQ). Furthermore, this approach makes it possible to describe the partitioning of absorbed excitation energy in PSII between three fundamental pathways, the complementary quantum yields [

28]: photochemical conversion (

YII), regulated thermal energy dissipation related to NPQ (

YNPO), and non-regulated energy dissipation as heat and fluorescence, mainly due to closed PSII reaction centers (

YNO). Moreover, the influence of temperature on the photosynthetic performance of

Sargassum was also studied by measuring dissolved oxygen concentrations in the incubation treatments [

21,

22,

24,

29,

30,

31]. As a general pattern, an increase in temperature inhibited photosynthesis.

In this study, we investigated the effects of increased temperatures on the photosynthetic performance of Sargassum natans, in the Brazilian southeastern coast, using PAM fluorometry and oxygen evolution rates. We focused on revealing the dynamics of the NPQ and the effective quantum yield of PSII (ΦPSII) under field conditions, as well as the behavior of other energy dissipation forms (complementary quantum yields, YII, YNPO, and YNO) under laboratory conditions. In the latter case, we comparatively assessed the effects of different temperatures on the photosynthetic performance of S. natans and Padina gymnospora, another co-occurring brown algal species.

6. Discussion

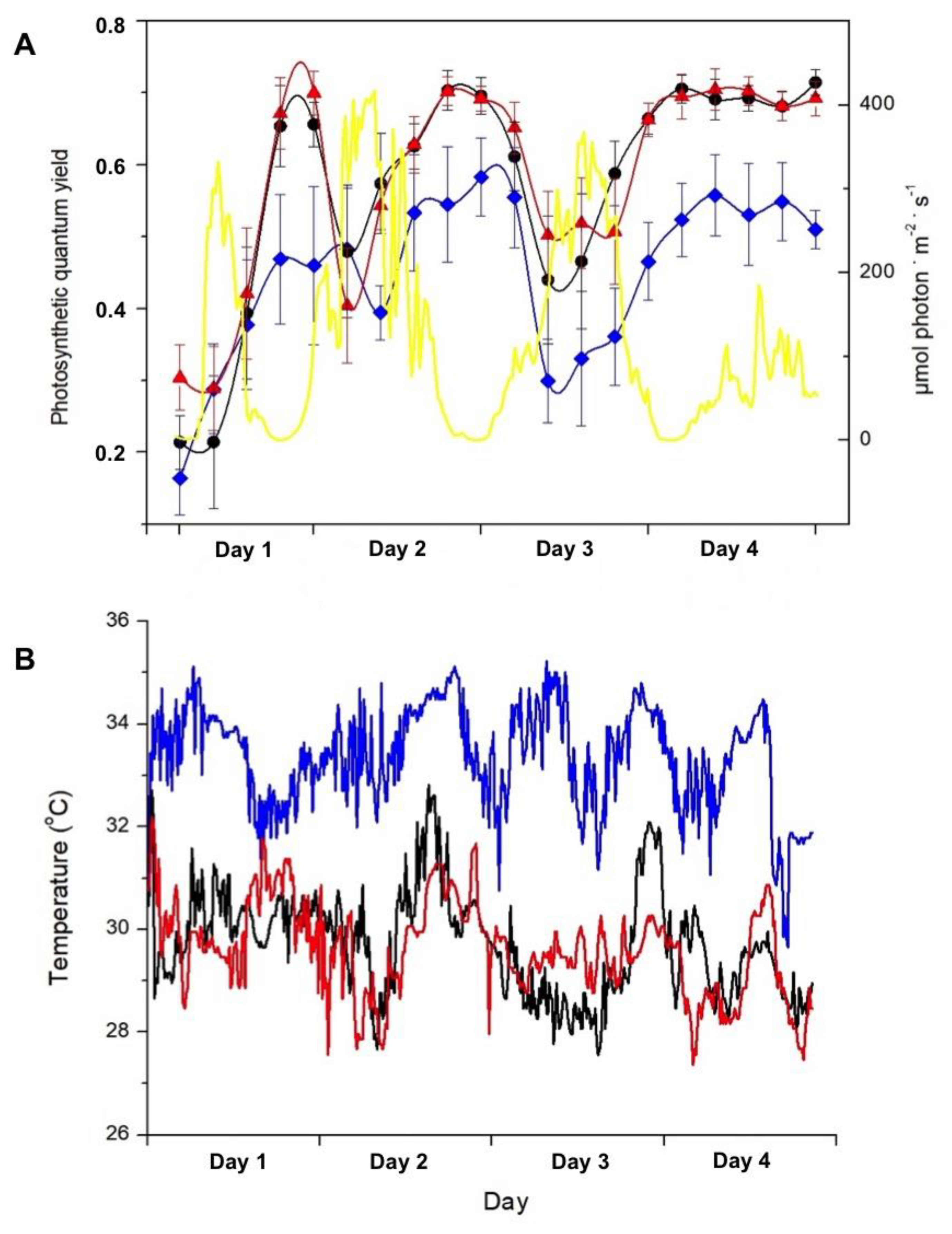

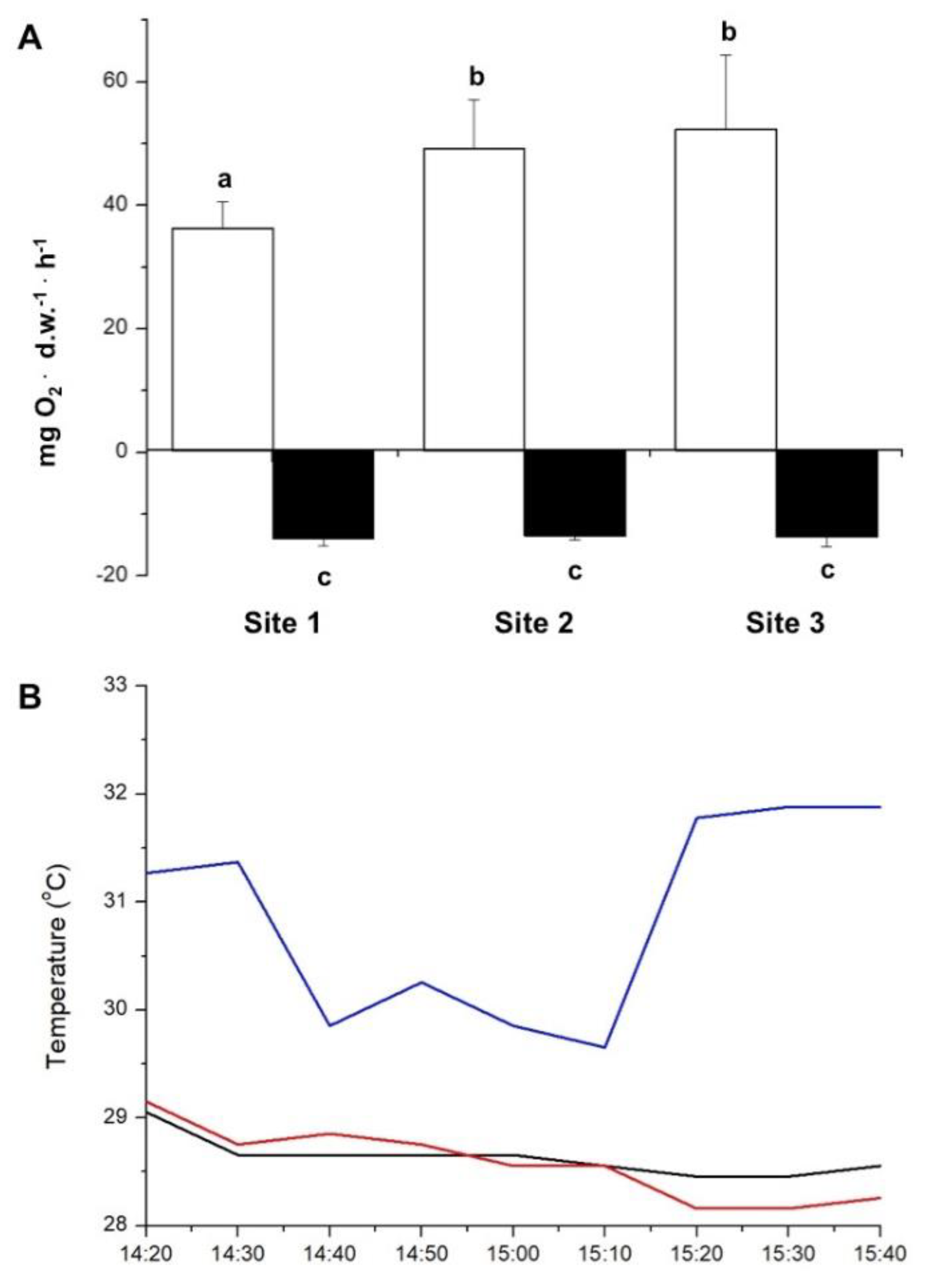

Our results clearly show that the photosynthetic activity of

S. natans was significantly affected by temperature. Net photosynthetic rates were decreased in algae incubated in the vicinity of the warm water effluent (200 m distance). Likewise, the effective quantum yield was also negatively affected by high temperatures. When manipulating the exposure of

S. natans to increased temperatures by incubating plants at closer distances to the thermal effluent outfall, an inverse relation between PAR and the photosynthetic quantum yield of PSII was observed, regardless of temperature. Over the four-day incubation, the quantum efficiency of PSII was maximal in the absence of light (21:00 h), decreased to a minimum towards midday, and recovered in late afternoon to the values recorded in early morning during the diurnal light cycle. Again, NPQ and

ΦPSII were inversely related, where

ΦPSII decreased with increasing irradiance as more electrons could accumulate at the PSII acceptor side. Then there was a relative increase in NPQ of the energy absorbed by the PSII antenna in the form of thermal energy dissipation [

26]. Because of the reduction in the incident light on the fourth day, no dissipation of energy occurred under the two temperature ranges and the quantum yields remained constant all day. It is noteworthy that at a temperature range of 28-31°C (500 and 1,200 m from the thermal effluent outfall),

Sargassum showed a substantial difference in

Fv/Fm (measured at 21:00 h) compared to exposure to higher temperatures (32-35°C). The stress induced by incubation at 32-35°C caused a decrease in

Fv/Fm by 33% on the first day and approximately 20% on the subsequent days. At the beginning of the experiment, regardless of the temperature, quantum yields were very low in the absence of light, probably indicating some sort of stress caused by the transplantation of the macroalgae.

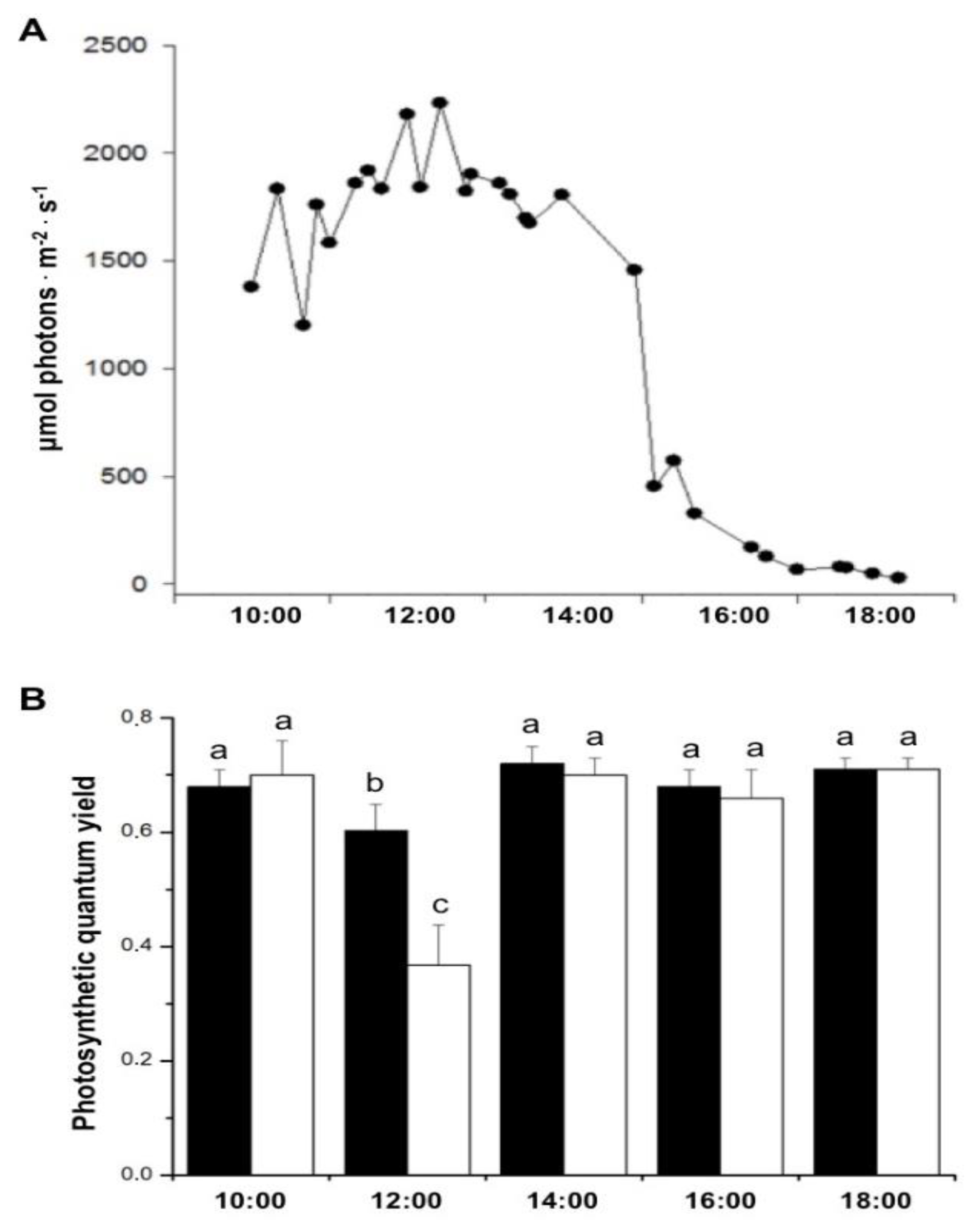

As observed for other

Sargassum species [

7,

21,

39],

S. natans collected from outside the thermal plume (at 4 m deep and temperature of 22°C along the day) exhibited characteristics of a sun-adapted plant, as evidenced by the daily variation of

Fv/Fm and

ΦPSII, suggesting the occurrence of dynamic photoinhibition. The initial value of

Fv/Fm in the morning was about 0.7, which is comparable to the levels observed for other

Sargassum species [

7,

22,

23,

39]. Photosynthesis, measured as

Fv/Fm and

ΦPSII, decreased at noon and then recovered rapidly to the values recorded in the morning, probably due to the combined factors of decreased irradiance and increase in the water column due to the tidal variation between noon and 14:00 h. Over this period time, there was an increase of approximately, 0.6 meters in the water column (Brazilian Navy’s Board of Hydrography and Navigation). The rapid recovery of

ΦPSII suggests that the responses of

S. natans to high light intensity are linked to dynamic photoinhibition, i.e., a photoprotective mechanism that involves a reversible down-regulation of the PSII activity. Thus, at midday, light-adapted

ΦPSII was 41% lower than the one measured for dark-adapted plants (

Fv/

Fm), due to the inherent impact of non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) reducing the light-adapted quantum yield [

40]. These results were reinforced by the photosynthetic performance parameters (rETR

max, alpha, and E

k) obtained from the RLC performed at different times of the day (from 10:00 to 18:00 h). Whereas the rETR

max presented essentially the same value, the decrease in alpha and the increase in E

k support the downregulation of the photosynthetic activity of

S. natans at midday. It has been reported that an increase in NPQ can reduce alpha value and avoid damage from high light stress to the PSII [

23,

41].

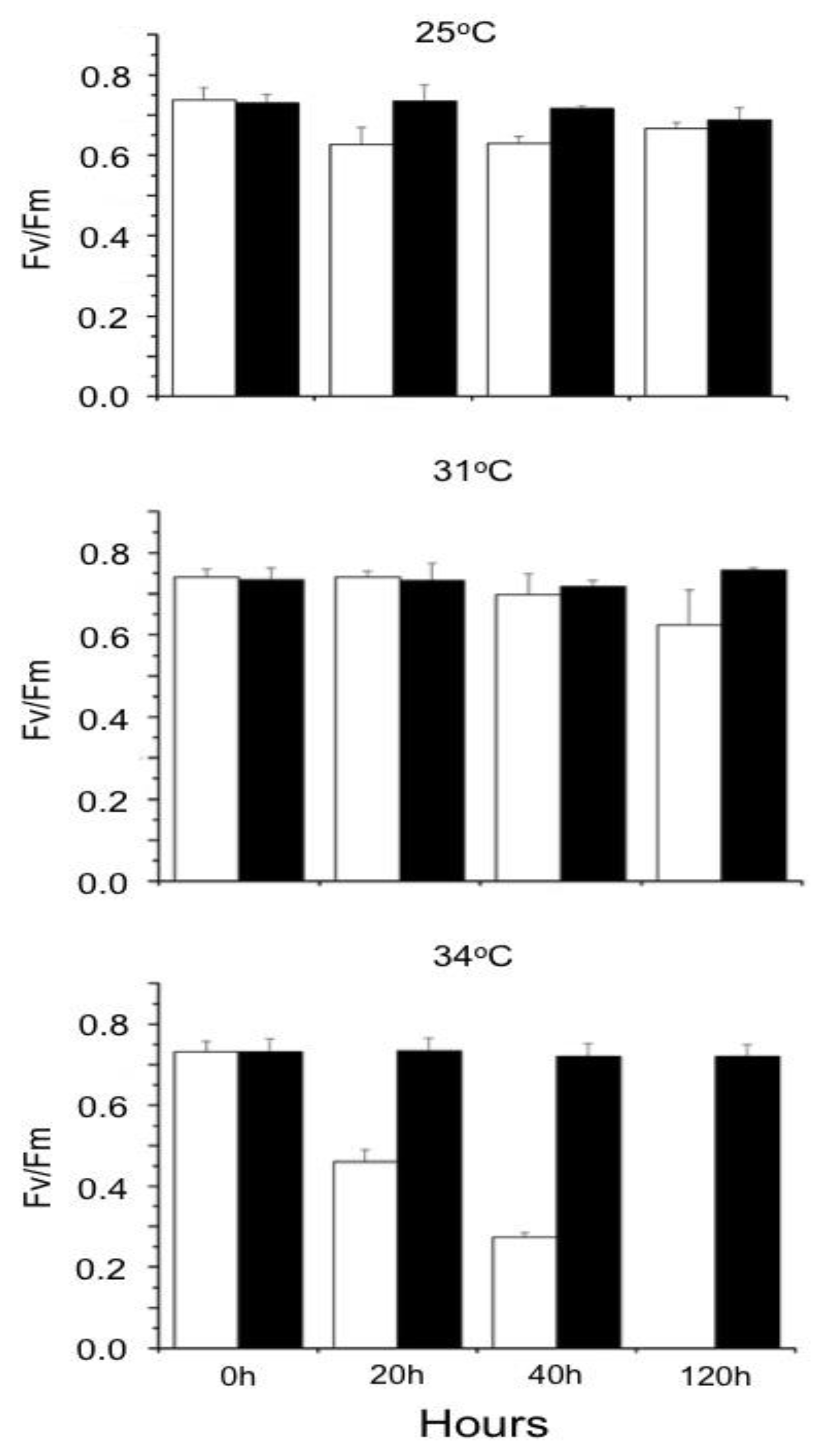

High temperature severely inhibited the photosynthetic performance of

S. natans under controlled conditions of the laboratory. The use of

Fv/Fm as an indicator of stress revealed the thermolability of the photosynthetic apparatus of

S. natans at 34°C since incubation for 20 h resulted in a 26.4% decrease in

Fv/Fm and a decline of 56.6% after incubation for 40 h. No activity was detected following 120 h incubation at 34°C. By contrast, the photosynthetic activity of

P. gymnospora was not affected by cultivation at 34°C, indicating that the plants of

P. gymnospora growing in IGB are adapted or acclimated to elevated temperatures, being tolerant to temperatures higher than 30°C, as suggested by Széchy et al. [

13].

In algae, high temperature reduces or even inactivates PSII, Rubisco, and Rubisco activase, severely inhibiting photosynthesis [

17,

18,

19]. Thus, the decline in carbon fixation via the Calvin cycle decreases the demand for reducing equivalents from the photosynthetic electron transport chain and absorption of excitation energy exceeds the capacity for its utilization, causing photodamage of the photosynthetic apparatus. In these events, massive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) causes oxidative stress that destroys cell membrane structures and leads to disorders of intracellular metabolism [

42,

43]. One of the defense mechanisms underlying the oxidative stress caused by high temperatures consists of a system that includes antioxidant enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase and peroxidases, which can mitigate oxidative damage by removing ROS formed under high-temperature stress [

20,

24]. Moreover, a multitude of photoprotection mechanisms were selected throughout evolution in plants and algae for their role in preventing damage by the action of ROS. One of the most important protection mechanisms is the dissipation of excessive excitation energy as heat in the light-harvesting complexes of the photosystems, termed NPQ [

35]. The general importance of NPQ for the photoprotection of plants and algae is documented by its wide distribution among photosynthetic organisms.

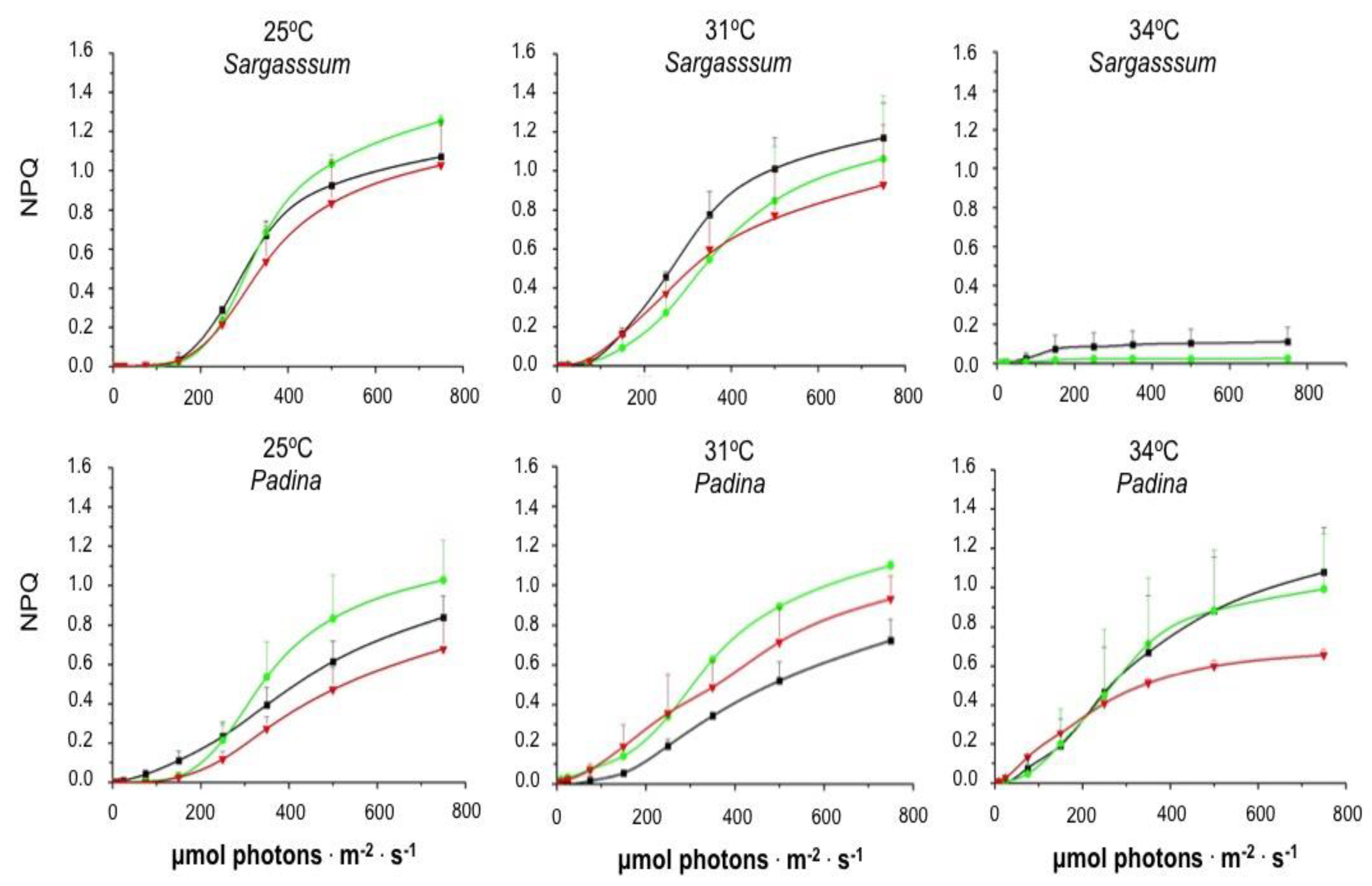

We observed that NPQ induction by increasing irradiance showed a sigmoidal-shaped NPQ pattern in the two brown algae cultured in the laboratory. Neither the induction pattern nor the NPQ capacity was affected by the exposure time (20, 40, and 120 h) to temperatures of 25, 31, and 34 °C, except for

S. natans exposed to 34°C. In this case, a virtually total inhibition of NPQ occurrence was observed after incubation for 20 h at 34°C. It is worth noting that the photoprotection (NPQ) mechanism to prevent damage to the photosynthetic apparatus was completely inhibited by high temperature before the complete decrease in

Fv/

Fm, indicating that the loss of photoprotection preceded photodamage. Thus, the antioxidant enzymes responsible for ROS scavenging [

20,

24,

43,

44] are likely unable to cope with the massive increase in ROS caused by the high temperature-induced NPQ inhibition.

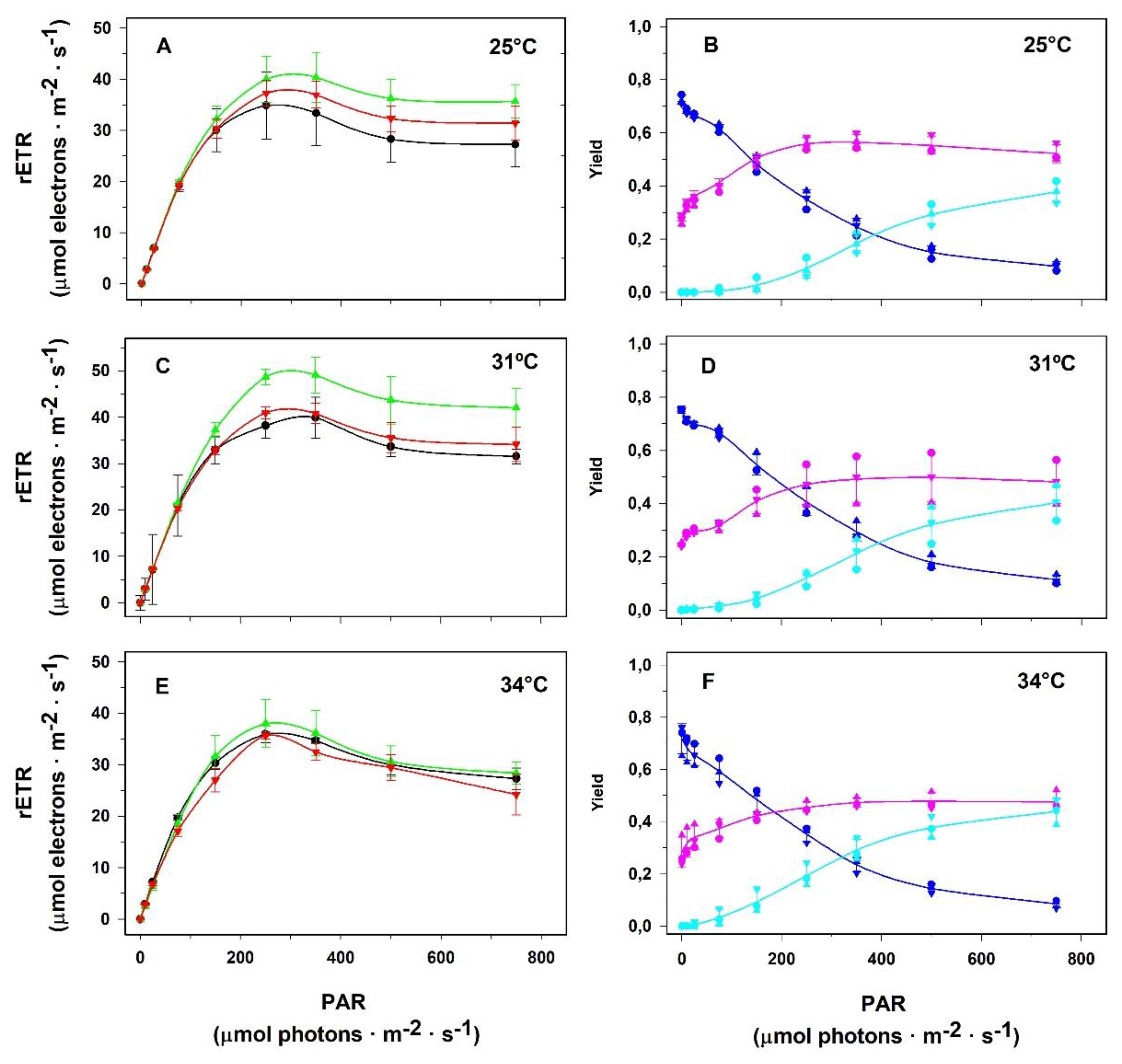

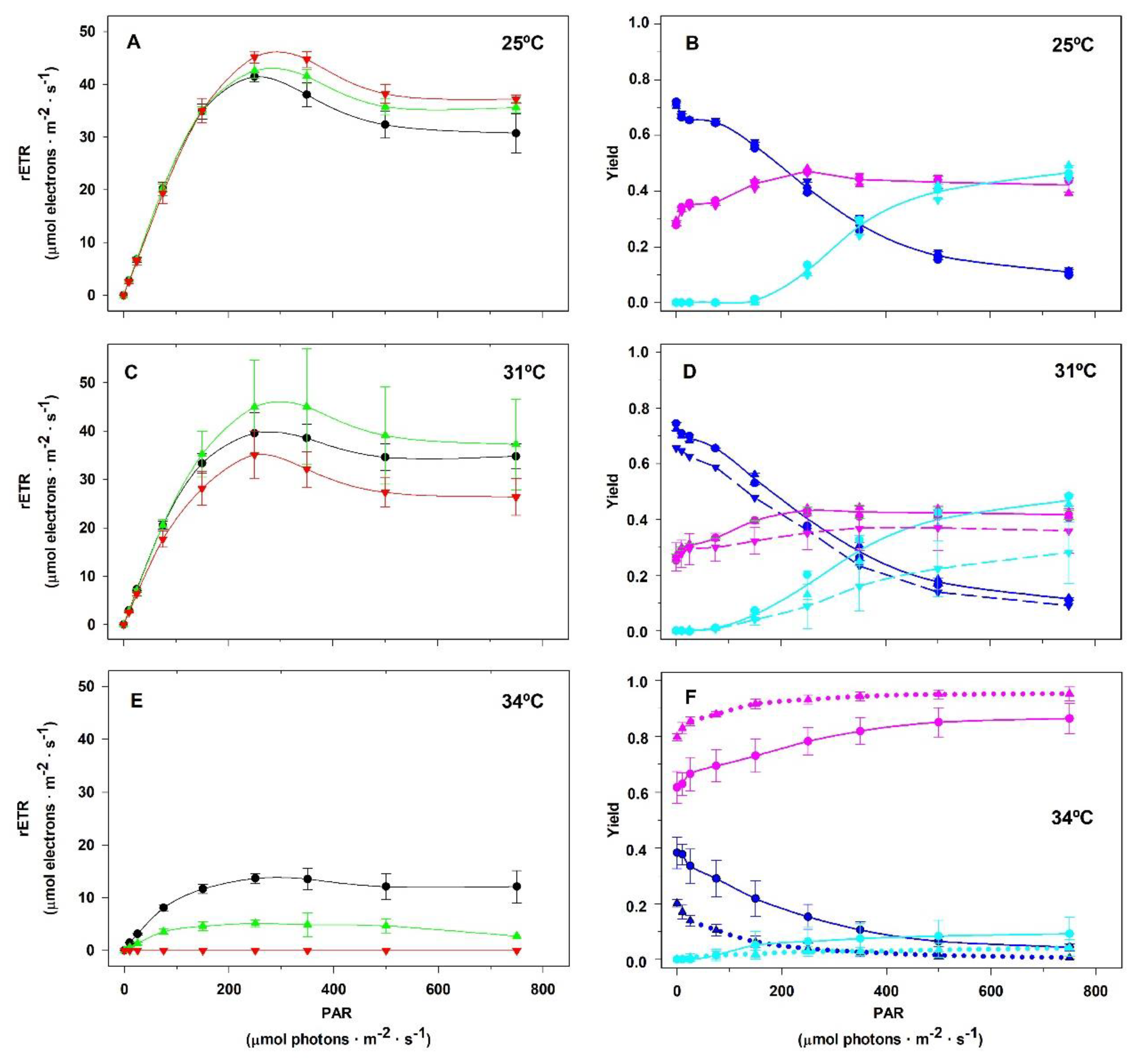

After 120 h of

S. natans cultivation under non-stressful conditions (25°C, 12 h photoperiod, and 90 μmol photon m

−2 s

−1 PAR), we found that 12, 44, and 44% of the absorbed energy from 750 μmol photon m

−2 s

−1 PAR were allocated, respectively, among

YII,

YNPQ, and

YNO. Under the same conditions, we found that

P. gymnospora shared 10, 34, and 56% of the energy absorbed by the PSII, respectively, among

YII,

YNPQ, and

YNO. Similar figures were found when

P. gymnospora was cultivated for 40 h at 34°C, whereas the fate of excitation energy in PSII among

YII,

YNPQ, and

YNO in

S. natans corresponded, respectively, to 1, 4, and 95%. According to Wang et al. [

45], a high

YNPQ indicates that the photon flux density is excessive and that the plant sample was able to protect itself by dissipation of excessive excitation energy into harmless heat. Without such dissipation, there would be the formation of ROS which causes irreversible damage. In contrast, high

YNO indicates that both photochemical and non-photochemical capacities are inefficient.

Our results reinforce that photosynthesis is highly sensitive to high-temperature stress and is often inhibited before other cell functions are impaired, in accordance to other studies [

21,

22,

24,

29,

30,

31]. In fact, photosynthesis in algae is extremely sensitive to high-temperature stress, as it can induce PSII inactivation, and destroy algal membranes and thylakoids, thereby inhibiting photosystem activities [

19]. Moreover, high temperatures reduce the activity of Rubisco, limiting photosynthetic carbon assimilation [

18,

46].

In conclusion, S. natans showed a clear dynamic photoinhibition indicated by the daily variation of Fv/Fm and ΦPSII. It also indicated that the stress induced by incubation at 32-35°C, over four days in the field, caused a decrease in Fv/Fm by 33% on the first day and approximately 20% on subsequent days. In the laboratory, the effect of exposure to different temperatures points to a lower tolerance of S. natans to temperatures above 31ºC, indicated by the significant drop in the rate of electron transport. Unlike Sargassum, P. gymnospora remained with high values of the same fluorescence parameters even at 34°C, indicating to be more equipped to thrive at temperatures higher than those presently occurring. Another result to be highlighted is the NPQ decline of non-photochemical quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence before the decline of maximum quantum yield of PSII, indicating that PSII is rapidly destroyed in the absence of this photoprotection.

Author Contributions

RC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data acquisition in the field and in the laboratory, Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing original draft, Writing-review; RM: Conceptualization, Data acquisition in the field, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology in field, Writing-review; JS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data acquisition in field, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Writing-review; CN: Obtaining, transporting and cultivating macroalgae in the laboratory, Methodology, Writing- review; FR: Methodology, Data acquisition in the laboratory, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Writing original draft, Writing-review; MTS: Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing-review.

Figure 1.

A- Diurnal variation of PAR on a pier located 200 m from the thermal effluent outfall, plotted as 10 s-average values. B- Diurnal variation in maximum (black columns) and effective (white columns) quantum yields of Sargassum natans collected at 4 m deep at the site located 200 m from the thermal effluent outfall. Means ± SD (n = 8). Different letters indicate significant differences between quantum yields values (ANOVA, p<0.05).

Figure 1.

A- Diurnal variation of PAR on a pier located 200 m from the thermal effluent outfall, plotted as 10 s-average values. B- Diurnal variation in maximum (black columns) and effective (white columns) quantum yields of Sargassum natans collected at 4 m deep at the site located 200 m from the thermal effluent outfall. Means ± SD (n = 8). Different letters indicate significant differences between quantum yields values (ANOVA, p<0.05).

Figure 2.

A- Daily variation of PAR (yellow line) and photosynthetic quantum yield at 2 m deep in sites 1 (blue symbols and line), 2 (black symbols and line) and 3 (red symbols and line), respectively 200, 500 and 1,200 m away from the thermal effluent outfall, throughout four days. At each location, the effective quantum yield was determined four times a day and the maximum quantum yield was measured once each night, and PAR was continuously registered. Means ± SD (n = 10). B- Seawater temperature at sites 1 (blue line), 2 (black line), and 3 (red line) 2 m deep, close to the studied plants, for four days.

Figure 2.

A- Daily variation of PAR (yellow line) and photosynthetic quantum yield at 2 m deep in sites 1 (blue symbols and line), 2 (black symbols and line) and 3 (red symbols and line), respectively 200, 500 and 1,200 m away from the thermal effluent outfall, throughout four days. At each location, the effective quantum yield was determined four times a day and the maximum quantum yield was measured once each night, and PAR was continuously registered. Means ± SD (n = 10). B- Seawater temperature at sites 1 (blue line), 2 (black line), and 3 (red line) 2 m deep, close to the studied plants, for four days.

Figure 3.

A- Net oxygen production in the presence of light (white columns) and oxygen consumption in the dark (black columns) after 90 min of incubation of Sargassum natans at sites 1, 2 and 3 in DBO bottles incubated at 2m deep at sites 1, 2, and 3. Means ± SD (n = 5). Different letters indicate significant differences. B- Seawater temperature during the experiment at sites 1 (blue line), 2 (black line), and 3 (red line), respectively 200, 500, and 1,200 m away from the thermal effluent outfall.

Figure 3.

A- Net oxygen production in the presence of light (white columns) and oxygen consumption in the dark (black columns) after 90 min of incubation of Sargassum natans at sites 1, 2 and 3 in DBO bottles incubated at 2m deep at sites 1, 2, and 3. Means ± SD (n = 5). Different letters indicate significant differences. B- Seawater temperature during the experiment at sites 1 (blue line), 2 (black line), and 3 (red line), respectively 200, 500, and 1,200 m away from the thermal effluent outfall.

Figure 4.

Effect of temperature on the maximum quantum yield of Sargassum natans (white columns) and Padina gymnospora (black columns). Brown algae were cultured in the laboratory for five days at 25, 31, and 34ºC under 90 µmol photons.m-2.s-1 irradiance. Following 20, 40, and 120 hours of culturing, algae plants were dark-adapted for 30 min and Fv/Fm was determined. Means ± SD (n=3).

Figure 4.

Effect of temperature on the maximum quantum yield of Sargassum natans (white columns) and Padina gymnospora (black columns). Brown algae were cultured in the laboratory for five days at 25, 31, and 34ºC under 90 µmol photons.m-2.s-1 irradiance. Following 20, 40, and 120 hours of culturing, algae plants were dark-adapted for 30 min and Fv/Fm was determined. Means ± SD (n=3).

Figure 5.

Influence of temperature on the Non-Photochemical Quenching (NPQ) as a function of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR). Brown algae were cultured at 25, 31, and 34ºC in the laboratory under 90 µmol photons.m-2.s-1 irradiance. Following 20 (black symbols and lines), 40 (green symbols and lines), and 120 (red symbols and lines) hours of culturing, Rapid Light Curves (RLC) were obtained just after the algae samples were taken from the culture vessel. Subsequently, algae were dark-adapted and Fm was obtained for the calculation of NPQ as a function of increasing irradiances. Means ± SD (n=3).

Figure 5.

Influence of temperature on the Non-Photochemical Quenching (NPQ) as a function of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR). Brown algae were cultured at 25, 31, and 34ºC in the laboratory under 90 µmol photons.m-2.s-1 irradiance. Following 20 (black symbols and lines), 40 (green symbols and lines), and 120 (red symbols and lines) hours of culturing, Rapid Light Curves (RLC) were obtained just after the algae samples were taken from the culture vessel. Subsequently, algae were dark-adapted and Fm was obtained for the calculation of NPQ as a function of increasing irradiances. Means ± SD (n=3).

Figure 6.

Influence of temperature on the allocation of the energy absorbed by PSII antenna of Padina gymnospora cultured in the laboratory at distinct temperatures under 90 µmol photons.m-2.s-1 irradiance. Rapid Light Curves (A, C, E) were obtained just after the algae samples were taken from the culture vessel following 20 h (black lines), 40 h (green lines) and 120 h (red lines) of culturing at 25 (A), 31 (C) and 34ºC (E). The complementary quantum yields (YII in navy blue lines, YNPQ in cyan lines, and YNO in pink lines) of cultures at 25 (B), 31 (D) and 34ºC (F). The complementary quantum yield lines represent average values among the three culturing times: 20, 40 and 120 h. Means ± SD (n=3).

Figure 6.

Influence of temperature on the allocation of the energy absorbed by PSII antenna of Padina gymnospora cultured in the laboratory at distinct temperatures under 90 µmol photons.m-2.s-1 irradiance. Rapid Light Curves (A, C, E) were obtained just after the algae samples were taken from the culture vessel following 20 h (black lines), 40 h (green lines) and 120 h (red lines) of culturing at 25 (A), 31 (C) and 34ºC (E). The complementary quantum yields (YII in navy blue lines, YNPQ in cyan lines, and YNO in pink lines) of cultures at 25 (B), 31 (D) and 34ºC (F). The complementary quantum yield lines represent average values among the three culturing times: 20, 40 and 120 h. Means ± SD (n=3).

Figure 7.

Influence of temperature on the allocation of the energy absorbed by PSII antenna of Sargassum natans cultured in the laboratory at distinct temperatures under 90 µmol photons.m-2.s-1 irradiance. Rapid Light Curves (A, C, E) were obtained just after the algae samples were taken from the culture vessel following 20 h (black lines), 40 h (green lines) and 120 h (red lines) of culturing at 25 (A), 31 (C) and 34ºC (E). The complementary quantum yields (YII in navy blue lines, YNPQ in cyan lines, and YNO in pink lines) of cultures at 25 (B), 31 (D) and 34ºC (F). The complementary quantum yield lines in B represent average values among the three culturing times: 20, 40 and 120 h. In D the continuous lines represent average values of 20 and 40 h, whereas the dashed lines correspond to 120 h. In F continuous lines represent values of 20 h, whereas the dotted lines correspond to 40 h values. Plants incubated for 120 h at 34ºC did not show any photosynthetic activity. Means ± SD (n=3).

Figure 7.

Influence of temperature on the allocation of the energy absorbed by PSII antenna of Sargassum natans cultured in the laboratory at distinct temperatures under 90 µmol photons.m-2.s-1 irradiance. Rapid Light Curves (A, C, E) were obtained just after the algae samples were taken from the culture vessel following 20 h (black lines), 40 h (green lines) and 120 h (red lines) of culturing at 25 (A), 31 (C) and 34ºC (E). The complementary quantum yields (YII in navy blue lines, YNPQ in cyan lines, and YNO in pink lines) of cultures at 25 (B), 31 (D) and 34ºC (F). The complementary quantum yield lines in B represent average values among the three culturing times: 20, 40 and 120 h. In D the continuous lines represent average values of 20 and 40 h, whereas the dashed lines correspond to 120 h. In F continuous lines represent values of 20 h, whereas the dotted lines correspond to 40 h values. Plants incubated for 120 h at 34ºC did not show any photosynthetic activity. Means ± SD (n=3).

Table 1.

Diurnal variation in the maximum relative electron transport rate (rETRmax), the photosynthetic efficiency (α), and the highest value of irradiance to begin saturation of photosynthetic activity (Ek) of Sargassum natans collected at 4 m deep at different daylight intensities at 10:00, 12:00, 14:00, 16:00, and 18:00 o’clock. The times correspond to GMT -3 (Greenwich Mean Time). Means ± SD (n = 5).

Table 1.

Diurnal variation in the maximum relative electron transport rate (rETRmax), the photosynthetic efficiency (α), and the highest value of irradiance to begin saturation of photosynthetic activity (Ek) of Sargassum natans collected at 4 m deep at different daylight intensities at 10:00, 12:00, 14:00, 16:00, and 18:00 o’clock. The times correspond to GMT -3 (Greenwich Mean Time). Means ± SD (n = 5).

Time

(h) |

rETRmax

(µmol electrons.m-2.s-1) |

α

(µmol electrons)/(µmol photons) |

Ek

(µmol photons.m-2.s-1) |

| 10:00 |

19.4 ± 2.0 |

0.384 ± 0.035 |

51 ± 4 |

| 12:00 |

17.8 ± 1.5 |

0.227 ± 0.048 |

62 ± 5 |

| 14:00 |

17.8 ± 1.6 |

0.422 ± 0.012 |

42 ± 3 |

| 16:00 |

16.6 ± 1.4 |

0.411 ± 0.019 |

40 ± 4 |

| 18:00 |

16.1 ± 3.3 |

0.409 ± 0.043 |

32 ± 2 |