1. Introduction

The origins of proteases are conserved alongside the evolution of proteins for catabolism and the generation of amino acids through the cleavage of peptide bonds, serving as executors of biochemical reactions in primitive organisms. However, a critical function of proteases has been identified as being of greater importance in the production of new protein products and the delineation of various cellular processes and signal transduction mechanisms in all living organisms. Proteases play a vital role in determining cell fate, localization, and the functionality of various proteins, influencing protein-protein interactions, generating new bioactive molecules, and transducing molecular signals for cellular information processing. Additionally, they are involved in DNA replication and transcription, cell growth and differentiation, tissue formation and remodeling, responses to heat shock and protein misfolding, the formation of blood vessels, the development of the nervous system, ovulation, fertilization, wound healing, mobilization of stem cells, blood clotting, inflammation, immune responses, cellular aging, and mechanisms of programmed cell death, which include apoptosis, autophagy, and necrosis [

1].

Proteases are initially synthesized as inactive proenzymes, referred to as zymogens, which necessitate proteolytic cleavage for activation. Upon activation, these enzymes cleave specific target proteins, thereby initiating the characteristic morphological alterations associated with apoptosis, including cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, and DNA fragmentation [

2,

3]. Proteases are classified based on their mechanism of hydrolysis of the peptide bond into two primary categories: exopeptidases and endopeptidases. These enzymes constitute a substantial group of hydrolytic agents that facilitate the degradation of proteins into smaller peptides or individual amino acids by cleaving the peptide bonds present in the polypeptide chain. According to degradome databases, a total of 588 human proteases have been identified, which are categorized into five classes based on the nature of their key catalytic subunit within the active site: 192 metallo proteases, 84 serine proteases, 64 cysteine proteases, 27 threonine proteases, and 21 aspartyl proteases. Among the 588 identified proteases, 21 are classified as specific proteases that are exclusive to humans [

4].

Exopeptidases execute their enzymatic activity by hydrolyzing exclusively the nitrogen or carbon terminal ends of the polypeptide chain of their substrate. Aminopeptidases function at the free N-terminal of proteins, facilitating the release of mono-amino acid residues, dipeptides, or tripeptides as byproducts. In contrast, carboxypeptidases operate at the C-terminal of protein chains. Carboxypeptidases can be classified into serine carboxypeptidases, cysteine carboxypeptidases, and metallocarboxypeptidases, according to the type of residual amino acid found in the protein moities [

5].

Endopeptidases predominantly facilitate the cleavage of non-terminal amino acids and are categorized according to the chemical group involved in the catalytic activity of the amino acids. Endopeptidases are classified into six distinct categories: (i) cysteine proteases, (ii) threonine proteases,(iii) serine proteases,(iv) glutamic acid proteases, (v) aspartic acid proteases, and (vi) metalloproteases [

5].

Classification of proteases are also based on several other criteria, including their substrate specificity, and structure as follows:

Substrate Specificity: Proteases can be categorized according to the specific types of peptide bonds they hydrolyze, as well as the size and sequence of the peptide substrates they preferentially target. For instance, trypsin, a serine protease, is known to cleave peptide bonds following basic amino acid residues, whereas chymotrypsin, another serine protease, cleaves peptide bonds subsequent to aromatic amino acid residues.

Structural Classification: Proteases may also be classified according to their structural characteristics, including the presence of specific domains or motifs. For instance, papain is categorized as a cysteine protease, distinguished by its characteristic papain-like fold, whereas matrix metalloproteinases represent a family of metalloproteases that share a common zinc-binding motif.

2. Proteases in Regulating Homeostasis & Cell Death

Proteases are integral to balance cellular homeostasis

via numerous biological activities including protein localization, protein-protein interactions, processing, and activation of various enzymes to regulate cellular response and cell death. Generally, it has been considered that proteases contribute to cellular homeostasis by regulating protein turnover and facilitating the degradation and removal of damaged, misfolded, or excess proteins, which can accumulate and disrupt normal cellular function. Proteases govern various signaling pathways that are essential for cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. For instance, caspases, a family of cysteine proteases, exist in the cytoplasm of cells as inactive precursors. The activation of caspases during apoptosis occurs through proteolytic cleavage, initiating a cascade of events that culminate in cell death. Additionally, caspases interact with other proteins to process and activate them. Many signaling molecules are initially synthesized as inactive precursor proteins, known as ‘zymogens,’ which must be cleaved by proteases to achieve activation. The zymogens of pancreatic serine proteases serve as model systems for in-depth investigations into the molecular changes that occur as a result of restricted proteolysis [

6].

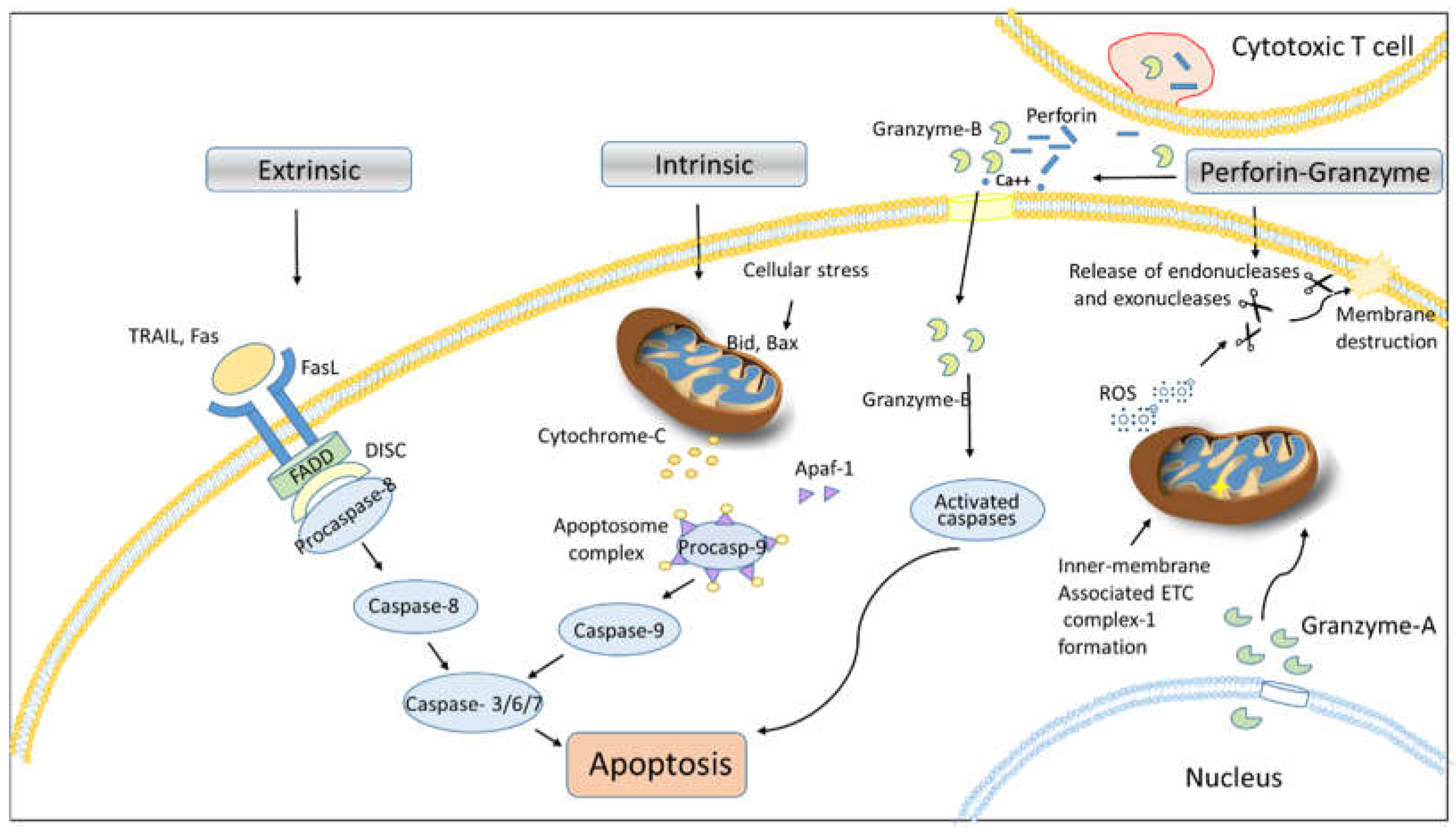

2.1. Proteases in Apoptosis

Damaged cells utilize two distinct mechanisms to arrest their progression in order to maintain homeostasis; either injured cells may emit inflammatory signals through the release of chemical mediators for initiating necrosis, or the activation of cascade of programmed cell death to selectively eliminate dysregulated cells without adversely affecting neighboring cells [

7]. Although there are various mechanisms of cell death have been identified including apoptosis, necrosis, autophagy, pyroptosis, necroptosis, and mitophagy etc. The role of proteases in the process of cell death is increasingly recognized, particularly as cell death is implicated in numerous diseases and pathological conditions. Therefore, it is essential to investigate the protease signaling pathways involved in the different modes of cell death.

Apoptosis (programmed cell death) represents a physiological mechanism employed by cells to undergo a self-destructive process triggered by various stimuli [

8,

9]. It is well established that proteases and their subsequent activation play a critical role in mediating apoptosis in response to specific death ligand signals such as, Fas ligand (FasL) and TNF family ligands. Apoptotic cells exhibit distinct morphological and biochemical characteristics. During the process of apoptosis, a cell loses microvilli and severs connections with neighboring cells. Concurrently, the cytoplasm undergoes condensation, and the endoplasmic reticulum experiences dilation, resulting in a net loss of water from the cytoplasm. These processes culminate in the formation of vesicles that display a characteristic bubbling appearance (

Figure 1). Additionally, the nuclear membrane is associated with rapidly formed, dense, crescent-shaped aggregates of chromatin [

10]. The apoptotic pathway is initiated by aspartate-specific cysteine proteases, also known as ‘caspases’ (

cysteinyl-directed

aspartate-specific prote

ase). These caspases are majorly grouped as initiator (caspase-8, 9, and 10), effector caspases (caspase-3, 6, and 7), and non-apoptotic caspases (caspase-1, 4, 5, and 11) [

11].

The extrinsic pathway is the external stimuli depndent pathway of apoptosis that initiated with the binding of the corresponding ligand with the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily (TNFRSF) members of proteins to transduceing cell death signaling. Mostly, these receptors are expressed on the surface of cells such as cytotoxic T lymphocytes, epithelial cells and other immune cells. TNFRSF oligomerizes in response to TNFSF binding, however some TNFRSF members already exist in oligomeric form in the absence of ligand binding. Apoptosis is induced by TNFRSF has a death domain (DD) of length approximately 80 amino acid. This death domain serve as an docking site for the pro-apoptotic proteins such as FADD and caspase8/10, which forms a death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) to activate of caspase cascade [

8,

12,

13].

Caspases exist in an inactive form known as zymogens. Upon death receptor (DR) activation, initiator caspases, procaspase-8 and/or procaspase-10 oligomerize with Fas-associated death domain (FADD) and cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein (cFLIP) to constitute the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC), leading to the processing and activation of caspase-8/10 and initiation of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway [

12,

14]. We have previously demonstrated that the cFLIP protein competitively inhibits the binding of caspase-8 to FADD, thereby preventing apoptosis induced by DR mediated apoptosis [

8,

9,

13,

15]. Caspase-8/10 further cleaves executioner caspases, caspase-3 and caspase-7 [

15,

16]. These executioner caspases facilitate DNA degradation by cleaving nuclear proteins, including lamins, actin, and the inhibitor of deoxyribonuclease (DNase). The cleavage of lamins augment disruption of nuclear function, whereas the cleavage of actin has inferences for cell division. The response elicited by this canonical apoptotic pathway may vary according to the specific receptors and ligands those are associated with process [

17,

18].

Intrinsic pathway is controlled by Bcl-2 family proteins through intracellular stimuli such as severe DNA damage results in activation of pro-apoptotic factors such as bax and bid that induces the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria. Mechanistically, cytochrome c associated with Apaf-1 and the initiator pro-caspase-9 to forms a complex known as “apoptosome”. The apoptosome complex facilitates the processing and activation caspase-9, which subsequently activates effector procaspase-3, thereby initiating intrinsic apoptosis signaling [

9,

19]. In conjunction with the apoptosome complex fromation, the simultaneous release of the protein Smac (second mitochondrial-derived activator of caspases) from mitochondria regulates the activities of processed executioner caspases and regulates intrinsic apoptosis signaling [

11,

17,

19].

2.1.1. Calpains in Cell Death

Calpains belong to a family of cysteine proteases that are activated by the release of Ca²⁺ ions, which are found in the mitochondria and cytoplasm of cells. These proteases play a crucial role in regulating apoptosis and necrosis. In the cytoplasm of a healthy cell, calpains exist in an inactive state as proenzymes. During stress, an increase in the concentration of intracellular free Ca²⁺ ions stimulates the activation of calpains. Under pathological conditions, short-term localized increases in cytosolic Ca²⁺ ion concentration can activate calpains, which are tightly regulated by the endogenous inhibitory protein calpastatin. As calpains are Ca²⁺-dependent proteases, disturbances in Ca²⁺ homeostasis can lead to dysregulation of their secretion, resulting in tissue damage [

20].

When endothelial cells are overloaded with Ca

2+, this condition induces the activation of mitochondrial calpain-1, resulting in Ca

2+ accumulation within the mitochondria. Activated calpain-1 subsequently activates a Bcl-2 family protein known as BH3-interacting domain (Bid). Bid then promotes the release of cytochrome c, leading to instigation of intrinsic apoptosis signaling [

21]. An earlier study using rat model system shown that, calpains regulate neuronal apoptosis during spinal cord injury [

22].

2.1.2. Cathepsin in Cell Death

Cathepsins, known as lysosomal proteolytic enzymes, are classified into three groups according to the amino acid located at their active site. These groups include cysteine proteases (cathepsins B, C, H, K, L, S, and T), serine proteases (cathepsins A and G), and aspartate proteases (cathepsins D and E). Among the aforementioned types, Cathepsin B and Cathepsin D play significant roles in apoptosis; these cathepsins are often referred to as "suicidal bags" due to their high concentrations of hydrolases. It is documented that Cathepsins B and D largely contribute terminal protein degradation, which take place the lysosomal compartment [

23,

24,

25]. Nonetheless, these two proteases are also implicated in cell migration and the malignant invasion of cancerous cells beyond the lysosomal compartment and possess the capability to degrade extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, including collagen, laminin, fibronectin, and proteoglycans [

26]. Notbly, cathepsins target the X-chromosome-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP), providing further evidence of cathepsin-mediated apoptosis occurring downstream of mitochondrial dependent intrinsic apoptotic pathway [

27].

2.1.3. Perforin-Granzyme Pathway in Cell Death

Granzyme A (GzmA) initiates a caspase-independent cell death pathway that exhibits morphological characteristics

akin to apoptosis, albeit with distinct substrate involvement. Gzm A, a tryptase, along with Granzyme B, a homologous serine protease, induces independent activation of apoptotic processes when delivered into target cells in conjunction with perforin (PFN), a pore-forming protein also referred to as a cytoplasmic granule toxin [

28]. Upon entering the cytosol of target cells, Gzm A is selectively transported from the nucleus to the mitochondria through the Tim/Tom/Pam protein complex pathway. Once inside the mitochondria, Gzm A degrades the inner membrane-associated electron transport chain (ETC) complex I by cleaving the NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 3 (NDUFS3), which is situated in the neck of the stalk of complex I that extends into the matrix. Disruption of complex I manifest the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which interferes with electron transport chain, mitochondrial transmembrane potential, and ATP generation. Consequently, this activation leads to the action of endonucleases and exonucleases, ultimately resulting in the destruction of the nuclear membrane and DNA leads to cell death [

29].

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) induce apoptosis in target cells through the release of perforin and granzyme B. Granzyme B is a serine esterase that has the capability to activate various members of the caspase family [

30]. In the presence of Ca

2+, perforin creates pores in the cellular membranes of target cells, allowing granzyme B to enter inside the cells. Upon entering the cell, granzyme B activates these proteases, leading to cell death via the stimulation of a “caspase cascade,” which is analogous to apoptosis induced by death receptors, as well as mitochondrial or endoplasmic reticulum (ER) disruption. In addition to caspases, other proteases, including calpains and cathepsins, also play a role in the apoptotic machinery [

11,

30].

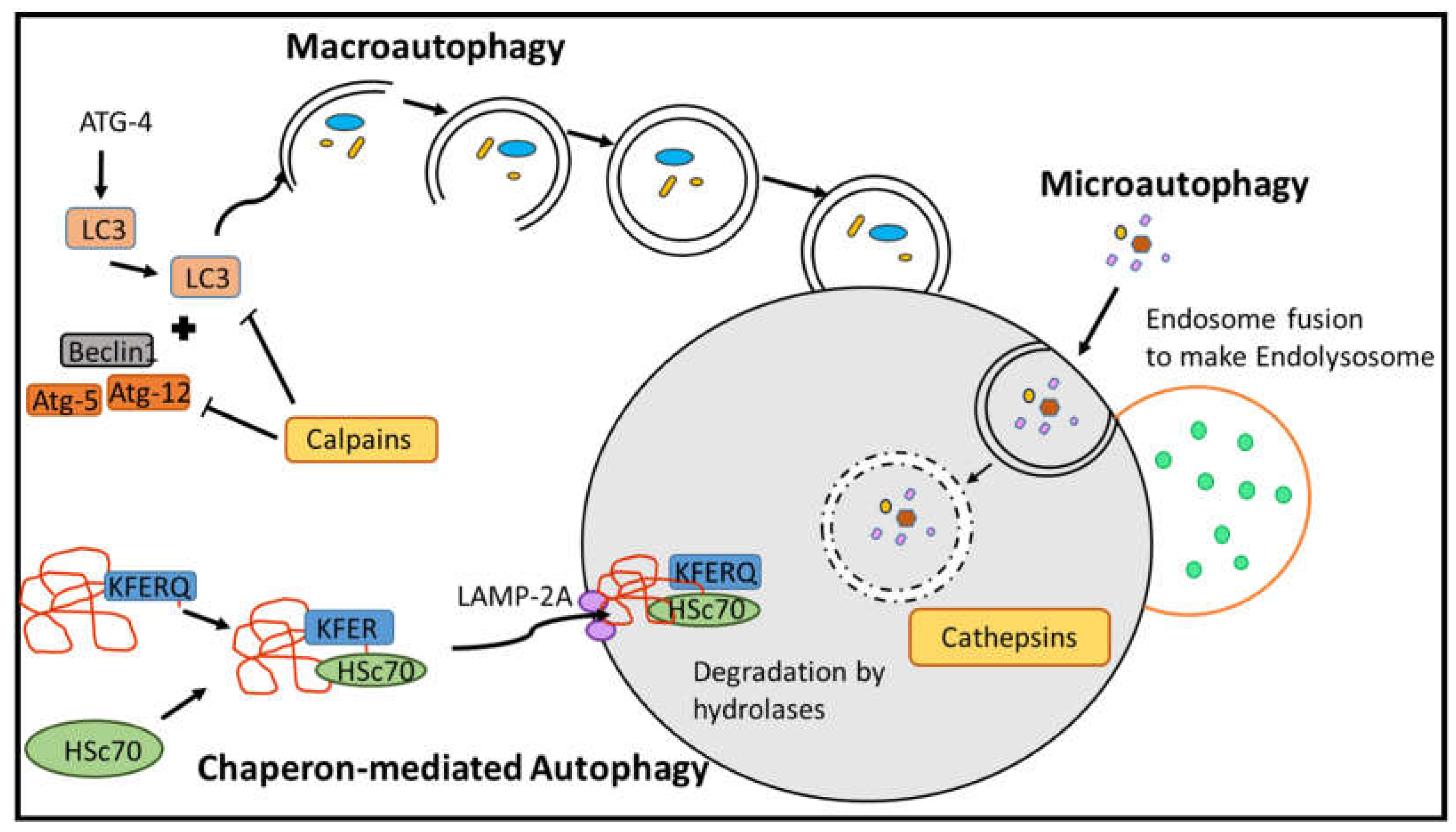

2.2. Proteases in Autophagy Pathways

Autophagy, often referred to as type II cell death, serves as the principal mechanism for the degradation of entire organelles and large macromolecules within lysosomes. This process is regulated by proteases and functions as an adaptive system in the maintenance of cellular homeostasis. It constitutes a well-organized mechanism of cell death that responds to both internal and external stimuli (

Figure 2). In mammalian cells, autophagy can be induced under certain conditions of nutrient deprivation; however, cells often preferentially undergo apoptosis more rapidly than transitioning to autophagy. Proteases present in the lysosome, including cysteine, aspartyl, and serine cathepsins, primarily play a crucial role in the autophagic pathway. Cathepsins B, L, and D are the predominant proteases in the lysosome that directly facilitate autophagy within the cell [

31].

2.2.1. Macroautophagy

Macroautophagy (also referred to as autophagy) is a multistage cellular process that degrades and recycles its own components. Macro-autophagy involves the assembly of double-membrane vesicular structures known as autophagosomes, which are initiated by Atg4, a type of protease enzyme that facilitates the cleavage and activation of LC3 (microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3), a key protein involved in autophagosome formation (

Figure 2). Autophagosomes are subsequently transported to lysosomes for fusion, resulting in the formation of the autophagolysosome complex, facilitated by calpain proteins [

32]. The contents of the autophagolysosome are degraded and utilized by the cell as nutrients. LC3-dependent autophagy significantly contributes to the regulation of infections in eukaryotic cells and helps to the proteolytic degradation of pathogens. Moreover, this form of autophagy may contribute to the downregulation of phagocytosis and is associated with the activation of host defense response and production of interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and the activation of the inflammasome complex [

33]. During chronic infections, such as those caused by parasitic

Leishmania species [

34,

35] and instances of gut dysbiosis [

36], macroautophagy is regulated by autophagy-specific genes that play a critical role in the degradation of various dysfunctional organelles. These organelles include mitochondria (mitophagy), the endoplasmic reticulum (reticulophagy), peroxisomes (pexophagy), and ribosomes (ribophagy). Additionally, macroautophagy plays a role in metabolic regulation through the selective degradation of macromolecules, including proteins, lipids, ribosomal RNA, and carbohydrates [

31].

2.2.2. Chaperon-Mediated Autophagy (CMA)

Chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) represents a distinct autophagic pathway that is regulated by proteases. This mechanism facilitates the degradation of specific cytosolic proteins within lysosomes, particularly during prolonged periods of nutrient deprivation. Unlike macroautophagy, which involves the formation of autophagosomes to degrade macromolecules or entire organelles characterized by large cytoplasmic volumes, CMA specifically targets the degradation of individual cytosolic proteins. Proteins containing a specific amino acid motif (KFERQ) are recognized by Hsc70, which binds to this motif and forms a complex with the target protein. The HSC70-target protein complex is subsequently unfolded and transported to the lysosomal membrane by the lysosomal-associated membrane protein type 2A (LAMP-2A) receptor. Once at the lysosomal membrane, the complex is degraded by lysosomal hydrolases [

31,

37]. Moreover, LAMP-2A exists within multimeric protein complexes in the lysosome. The cytosolic protein Hsc70 plays a crucial role in the disassembly of LAMP-2A complexes, a process required to maintain the CMA activity. In contrast, Hsp90 contributes to the stabilization of LAMP-2A at the lysosomal membrane [

37,

38].

2.2.3. Microautophagy

Microautophagy was first investigated in rat liver and subsequently evaluated in the yeast, where this mechanism is utilized for the collection and degradation of peroxisomes when the organism has transitions to utilize glucose as an energy source [

39].

In vitro microautophagy reconstitution with isolated vacuoles has facilitated to further evaluate the molecular mechanism of autophagic pathway. Microautophagy is a mechanism for the degradation of intracellular proteins and organelles, facilitated by lysosomal or vacuolar engulfment of cargo vesicles in yeast. Various terms have emerged to describe the specific types of cargo being engulfed, such as micro-pexophagy for peroxisomes, micro-mitophagy for mitochondria, and micro-lipophagy for lipid droplets [

40]. The specificity of micro-autophagy has been further supported by the discovery of Nvj1p, a cargo receptor that is specific for piecemeal micro-autophagy, which involves the digestion of nuclear material. Activation of microautophagy has been observed in Drosophila following a period of starvation exceeding 24 hours, in contrast to mammals, where no microautophagy is detected under similar conditions. Atg1 and Atg13 are downstream components of the TOR (target of rapamycin) signaling pathway, a key nutrient sensor that may become activated in response to nutrient starvation in Drosophila, whereas TOR and EGO have been identified as regulators of yeast micro-autophagy and lipophagy [

41]. Moreover, 5' AMP-activated protein kinase and Atg14 contribute to the activation of macrolipophagy [

42].

The detection of micro-autophagy in mammals has been a protracted process, primarily due to the challenges associated with observing lysosomal invagination, as well as the potential lack of conserved functions of genes implicated in yeast micro-autophagy within mammalian cells [

39]. However, recent studies have demonstrated that a comparable degradative process occurs in the late endosomes and multivesicular bodies of mammals. Endosomal micro-autophagy relies on the assembly of ESCRT (endosomal sorting complexes required for transport), which is involved in delivering endocytosed proteins to the intraluminal vesicles of late endosomes. Furthermore, it has been found that cytosolic hsc70 does not play a significant role in the regulation of autophagy [

31].

2.3. Proteases in Necrosis/Necroptosis

Necroptosis is a distinct form of cell death characterized by cellular rounding, an increase in cell volume, rupture of the plasma membrane, leading to the release of intracellular constituents. This process can be initiated by a variety of stimuli, including members of the death receptor family, Toll-like receptors, Fn14, calcium ions (Ca

2+), T cell receptors (TCRs), TNF receptor 2 (TNF-R2), proteasome inhibitors, intracellular RNA and DNA sensors, interferons (IFNs), reactive oxygen species (ROS), as well as by various cellular stresses such as ionizing radiation. All of these stimuli activate key molecules involved in necroptosis: receptor-interacting serine-threonine protein kinase 3 (RIPK3), receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1), and the pseudokinase mixed-lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL). In response to necroptotic stimuli, RIPK1 recruits RIPK3 to initiate necrosome formation and subsequently activates RIPK3 through phosphorylation. Activated RIPK3 then recruits phosphorylated MLKL. Consequently, phosphorylated MLKL oligomerizes and translocates to the plasma membrane. The translocation of MLKL to the plasma membrane facilitates an increase in its permeability. According to certain theories, MLKL may influence plasma membrane permeability by either opening ion channels or forming pores within the plasma membrane [

43]. Despite MLKL's classification as an execution effector in the necroptosis pathway, the precise mechanisms underlying necroptosis, as well as its implications for inflammation and other cellular responses, remain largely unclear. Inhibitors of necroptosis include Necrostatin-1s (Nec-1s), RIPK3 inhibitors (such as GSK′840, GSK′843, GSK′872, GW′39B, and dabrafenib), MLKL inhibitors (including necrosulfonamide and NSA, which inhibits humanMLKL), and various viral and bacterial proteins, including M45, IE1, ICP6, ICP10, and NleB1. Low or negligible protease activity appears to favor the necroptosis pathway, whereas high protease activity typically promotes the apoptotic cell death pathway. Consequently, proteases play a limited role in the regulation of necroptosis [

17,

44].

3. Proteases in Pyroptosis and Inflammation

Pyroptosis, a term derived from the Greek words "pyro," meaning "fire," and "ptosis," meaning "falling," refers to a form of programmed cell death that is comparable to apoptosis [

45]. It is triggered by pro-inflammatory signals, specifically. Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs) and Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs), and implicated in cellular inflammation through the formation of a heterologous protein complex referred to as “inflammasomes” [

46,

47,

48,

49]. Inflammasomes activation aids in the recruitment of inflammatory caspases. Some of the inflammatory caspases include caspase-1, -4, -5, and -12, which are encoded by the human genome, while caspase-11 is encoded along with caspase-4 and caspase-5 in the mouse genome, in addition to caspase-1. Inflammasomes serve as a platform for the recruitment of caspase-1 and promote the surrounding environment to induce pyroptosis. However, caspases -4, -5, and -11 do not require such molecular complexes for their activation [

14].

Pyroptosis follows either the canonical pathway, which involves the activation of caspase 1, or the non-canonical pathway, which involves the activation of caspase 4/5 or 11 [

50]. The canonical pathway encompasses the activation of caspase-1 through a supramolecular complex composed of NLR (NOD-like receptor) proteins, Pyrin proteins, and Pyrin and hematopoietic interferon-inducible nuclear (HIN) domain (PYHIN) proteins. These NLR proteins activate the inflammasome adaptor protein ASC, which facilitates the conversion of procaspase-1 into its active form, caspase-1. Activated caspase-1 plays a critical role in the activation and maturation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and gasdermins (GSDMs), as well as in the release of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-18 (IL-18) from the cell, a process that occurs through the formation of pores in the plasma membrane [

50,

51]. A recent report highlighted that distinct isoforms of the GSDMB protein and proteolytic cleavage by various caspases differentially regulate pyroptotic cell death and mitochondrial damage in cancer cells [

52]. Gasdermins (GSDMs) represent a diverse structural family of proteins implicated in pyroptosis and are commonly referred to as execution proteins of this form of programmed cell death. In addition to their role in pyroptosis, GSDMs are involved in the regulation of various cellular processes, including coagulation, inflammation, necrosis, tumorigenesis, and differentiation [

53]. The majority of proteolytic enzymes targeting GSDMB are caspases, which are primarily associated with the transduction of inflammatory and apoptotic signals. The cleavage of GSDMD by caspases-1, 4, 5, and 11 is a critical event that initiates pyroptosis and has been the subject of extensive research within the gasdermin family [

54]. Furthermore, GSDMD can be activated not only

via caspase cleavage but also by serine proteases derived from neutrophils. These proteases are significant due to their ability to cleave microbial toxins and structural proteins, in addition to host cytokines and chemokines, thereby impacting inflammatory responses during infections [

55]. Recent studies have indicated that pyroptosis can exacerbate the toxicity of chemotherapeutic agents, contributing to cell death through gasdermin-mediated programmed necroptosis [

56]. The involvement of GSDMs in cell death and inflammatory processes is gaining recognition as a potential avenue for therapeutic intervention.

The non-canonical pyroptosis pathway is directly activated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) derived from extracellular Gram-negative bacteria, which facilitates the activation of caspases -4, -5, and -11, ultimately leading to cell death [

57].

3.1. Eryptosis

Erythrocytes, or red blood cells, are produced in substantial quantities within the human body to fulfill the requisite demand for oxygen. The body must maintain a delicate balance between the proliferation of erythrocytes and the removal of aged and damaged cells through established cellular death mechanisms. The elimination of senescent and compromised erythrocytes occurs via the processes of eryptosis or hemolysis. Given that erythrocytes are enucleated and devoid of organelles, they are unable to undergo traditional apoptotic pathways. Instead, they emulate apoptosis through a programmed cell death mechanism known as eryptosis, which can be induced by factors such as oxidative stress, osmotic shock, or energy depletion [

58]. Processes such as cell shrinkage, microvesiculation of the plasma membrane (blebbing), and the externalization of phosphatidylserine occur in a manner analogous to apoptosis; however, these processes do not initiate the activation of the caspase protease cascade. Rather, they result in the activation of cysteine proteases known as calpains [

59,

60,

61].

Calpains are activated by an increase in intracellular Ca

2+ levels or by the release of prostaglandins. Activated calpains mediate the cleavage of fodrin or the degradation of ankyrin-R. Calpain-mediated eryptosis has been reported by various research groups [

62,

63]. It has also been reported that in erythroid progenitor cells, interferon-γ induces the activation of caspase-1, caspase-3, and caspase-8, facilitating apoptosis during early differentiation [

64]. However, these procaspases cannot be activated even by prolonged exposure to various caspase activators, including ionomycin or hyperosmotic shock [

61]. Erythrocytes also undergo the typical process of cellular senescence; however, this process differs from programmed cell death in that the latter occurs over a timescale of minutes, whereas erythrocyte clearance from the circulatory system requires several days.

Ferroptosis is a form of regulated necrotic cell death that occurs in response to the inactivation of the glutathione system and the accumulation of excess iron, accompanied by lipid peroxidation. It was first described by Dixon et al. in 2012 as an iron-dependent, non-apoptotic mechanism of cell death driven by lipid reactive oxygen species [

65]. Nagakannan et al. (2020) demonstrated the involvement of Cathepsin B protease, which is located in the lysosome, in promoting the cleavage of histone protein H3 and eliciting certain mitochondrial changes that induce ferroptosis. The findings were further validated by the knockout of the

cathepsin B gene in primary fibroblast cells, which exhibited an unaltered response to various inducers of ferroptosis [

66]. Cathepsin B appears to induce ferroptosis through its translocation from the lysosome to the nucleus, which is mediated by lysosomal-nuclear DNA damage [

67].

3.2. Entosis

Entosis is a non-apoptotic cell death process observed in human tumors, which is provoked when a cell loses its attachment to the extracellular matrix. This process commences when one cell engulfs another, resulting in the degradation and processing of the internalized cell by lysosomal enzymes. Entosis exhibits cytological features characteristic of 'cannibalism' or 'cell-in-cell' phenomena, which are frequently observed in human tumor cells that are in the process of metastasis during carcinogenesis [

68,

69]. The engulfed cell undergoes degradation through lysosomal processes, which are initiated by the lipidation of LC3 (Light Chain 3). This process further recruit lysosome-associated membrane glycoproteins (LAMPs), leading to the acidification of the degradation compartment and the deposition of lysosomal proteases, primarily Cathepsin B, which facilitate the complete degradation of the internalized cell within the hostile environment. Additionally, under certain conditions, the internalized cell may experience starvation within the vacuole, potentially leading to its own apoptosis. In both scenarios, whether through apoptotic or non-apoptotic pathways, the host cell is subject to invasion [

70].

3.3. Oncosis

Oncosis is a form of accidental cell death exemplified specifically by ischemic cell death, which is accompanied by cellular swelling resulting from the failure of ionic channels and pumps in the plasma membrane. This process differs from necrosis in that cell swelling is a prominent feature of oncosis, whereas it is not a characteristic of necrosis [

71]. Calpains, a family of Ca2+-dependent cysteine proteases, are known to be involved in oncotic cell death [

72]. There is limited literature regarding the role of calpains in oncotic cell death, and the involvement of other proteases in oncosis remains to be further explored.

4. Proteases in ER- Stress Mediated Cell Death

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress-mediated cell death represents an emerging mechanism that is currently under investigation by numerous researchers. ER serves as the primary site for the assembly of polypeptide chains within the cell, facilitating their proper folding and subsequent localization to various cellular compartments. Exposure to stressors, such as tunicamycin, brefeldin A, or thapsigargin, can lead to the misfolding or unfolding of these polypeptide chains [

36,

73,

74,

75]. In response to such stress, the cell increases the transcription of genes encoding molecular chaperones of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), including GRP78, a chaperone that facilitates protein folding within the lumen of the ER; any perturbations may lead to pathological consequences [

76,

77]. This cellular response to unfolded proteins is mediated by IRE1α (Inositol-requiring transmembrane kinase/endoribonuclease 1α), PERK (Protein kinase R-like ER kinase) and ATF6 (Activating transcription factor 6), the stress sensor proteins located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [

73,

76]. The ER serves as a primary hub for the regulation of protein folding; consequently, a significant accumulation of misfolded proteins is translocated from the ER to the cytoplasmic environment for degradation

via the ubiquitin-proteasome system, which is referred to as the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) system [

74,

78]. However, if the amount of malfolded proteins increases due to prolong stress it leads to the activation of various apoptotic cell death pathways. One of the important pathways is c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway that triggers release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria for further activation of apoptosis [

74,

79]. In addition to cytochrome c, chronic ER stress induces the activation of caspase-12

via inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (Ire1) in rodent models. Furthermore, elevated release of Ca

2+ ions triggers the activation of calpains, which subsequently activates caspase-12 [

80]. However, caspase-12 is absent in most humans; therefore, the relevance of caspase-12-mediated apoptosis during ER stress remains questionable. In this regard, human caspase-4 may be assumed to participate in ER-mediated cell death, as it is a close paralog of caspase-12. However, this assumption is still under investigation and requires further exploration in future research on ER-mediated cell death [

81].

5. Proteases and Cancer

Over the past three decades, researchers have studied protease activity in the final stages of tumor development, invasion, and metastasis. In the past 20 years, research advancements have shown that proteases play a role in the early progression of the disease. Numerous proteases have been recognized extracellularly for their involvement in breaking down the extracellular matrix and facilitating tumor cells in their invasion through different proteolytic cascade mechanisms. (

Table 1).

5.1. Proteases in Tumor Progression

Proteases play an important role in tumor progression and metastasis. As previously discussed, proteases in normal cells perform various essential homeostatic biological functions; however, in the context of transformed tumor cells, they can cause significant dysregulation [

82]. The prognostication of tumors becomes challenging in the presence of specific proteases, which are not exclusively expressed by tumor cells. In many cases, tumor cells affect the expression of these proteases in non-neoplastic cells, effectively commandeering their growth mechanisms to promote tumor expansion [

83]. The development of tumors is an intricate process that involves numerous alterations in normal cellular functions. Tumor progression encompasses a series of sequential steps characterized by mutations and natural selection. A specific group of peptidases (proteases) is actively involved in the progression of mutations that are collectively referred to as the cancer "degradome." Traditionally, invasion and metastasis have been considered the terminal stages of cancer development, with proteases playing a crucial role in these processes. However, recent studies indicate that invasion and metastasis may also occur during the early stages of tumor development. The following proteases shape tumor progression through complex signaling mechanisms.

5.1.1. Serine Proteases

Among proteases, approximately one-third of human proteases are classified as serine proteases. These enzymes are typically anchored to the plasma membrane and are thus referred to as type II transmembrane serine proteases (TTSPs). Dysregulation of these proteases has been associated with tumor progression, as altered expression levels of TTSPs serve as indicators for various forms of tumors. In vertebrates, these proteases include matriptase, hepsin, TMPRSS-2/4 (transmembrane protease/serine), fibroblast-activating protein α (FAP α or seprase), urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA)/urokinase, and kallikrein-related peptidases (KLKs), among others [

84].

Matriptase, a protease expressed by epithelial cells across various tissues, has been identified as being overexpressed in numerous epithelial tumors (carcinomas), including those of the skin, breast, cervix, prostate, ovary, and uterus. Conversely, some studies indicate a downregulation of matriptase in colorectal cancer. A critical finding related to matriptase in several cancers is its increased ratio relative to its endogenous inhibitors, hepatocyte growth factor activator inhibitors (HAI-1 and HAI-2), which leads to an alteration in the balance of protease activity. This shift results in heightened matriptase activity, contributing to a pro-carcinogenic environment. Matriptase has been shown to play a role in the initiation of the c-Met signaling pathway through the proteolytic cleavage of pro-HGF into active HGF, a paracrine growth factor. Active HGF subsequently initiates downstream signaling cascades, including the PI3K/AKT pathway and the c-Met docking protein Gab1 [

84,

85].

Hepsin, a serine protease, is significantly overexpressed in breast cancer tissues. Studies indicate that the induced expression of hepsin in mammary epithelial organoids is correlated with a downregulation of HAI-1 and an enhancement of HGF/c-Met signaling pathways. Furthermore, Hepsin plays a critical role in the invasion of breast cancer cells by cleaving extracellular laminin-332, a crucial component of hemidesmosomes located at cell-cell junctions. Additionally, urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA), extracellular serine protease, is synthesized and secreted as an inactive zymogen pro-uPA [

86]. Other proteases such as cathepsin B and L, Kallikrein, trypsin, and tryptase activate pro-uPA into uPA [

86]. Active uPA, upon binding to the cell surface receptor (uPAR), actively converts plasminogen into plasmin. uPAR is highly expressed in a wide variety of solid tumors, including those of the breast, brain, prostate, and head and neck. Plasmin, a non-specific protease, plays a role in the degradation of laminin, fibronectin, collagen IV, vitronectin, and various blood clotting factors through interactions with other proteases, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [

85].

5.1.2. Cysteine Proteases

Caspases, calpains, and cathepsins represent three distinct categories of cysteine proteases that are acknowledged for their contributions to either tumor suppression or tumor promotion in oncogenesis. Caspases, which play a pivotal role in the execution of apoptosis, exhibit functions that may seem paradoxical to the advancement of malignant tumors. While genetic mutations are predominantly implicated in the etiology of various types of cancer, these mutations are not typically associated with the caspase family [

87]. The expression of caspases and cancer prognosis often present contradictory findings. For instance, in patients undergoing curative surgery for gastric cancer, expression of caspase-3 is associated with a lower recurrence rate compared to those who exhibit a deficiency in caspase-3 [

88,

89]. In contrast, patients with advanced gastric cancer (stage IV) demonstrate that the expression of caspase-3 is associated with poorer overall survival [

90]. In addition to their role in apoptosis, caspases also mediate a range of non-apoptotic functions, including cellular proliferation, immune response, cellular migration, and plasticity [

91].

Calpains, a class of calcium-dependent proteases typically present in an inactive form within the cytosol, have been demonstrated to be overexpressed in various malignancies. Specifically, the overexpression of calpain-1 has been documented in meningiomas, schwannomas, and oral squamous cell carcinoma, whereas the overexpression of calpain-2 has been observed in colorectal cancer (CRC) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [

92,

93,

94]. Tumor migration and invasion are facilitated by calpains, which are implicated in the cleavage of various cytoskeletal and focal adhesion proteins. Although the role of calpains in tumor development and metastasis are well established; however, their contribution in the process of apoptosis is not yet fully elucidated [

95].

The mechanisms through which cysteine cathepsins contribute to cancer pathogenesis remain a subject of ongoing investigation. Elevated expression and activity of cysteine cathepsins, particularly cathepsin B, have been documented in a variety of human tumors, including those of the lung, breast, brain, prostate, and gastrointestinal tract, suggesting a correlation with the presence of aggressive cancer cell phenotypes [

96,

97]. Numerous studies have shown that cysteine cathepsins are crucial for remodeling the extracellular matrix (ECM) in the tumor microenvironment, which in turn promotes invasion and metastasis [

89,

90]. Pericellular cysteine cathepsins are essential; (i) to initiate the proteolytic cascade by activating other proteases, including pro-uPA (urokinase plasminogen activator); (ii) to direct proteolyze extracellular matrix (ECM) components like laminin, fibronectin, and type IV collagen; and (iii) to deactivate cell adhesion proteins such as E-cadherin [

98].

A substantial body of evidence supports the role of cysteine cathepsins in the execution of programmed cell death in various tumor cell lines, elicited by death ligands such as TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor α) [

99] or TRAIL (TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand) [

100]. For instance, it has been shown that cysteine cathepsins participate in TNF-α-induced programmed cell death in murine fibrosarcoma WEHI-S and human cervical carcinoma ME180 [

99], ovarian cancer OV-90, hepatoma SMMC-7721, and prostatic cancer PC-3 [

96]. In recent years, the apoptosis-inducing properties of TRAIL, which selectively targets cancer cells while preserving normal cells and tissues, have garnered significant attention from researchers in the field of cancer therapy.

5.1.3. Aspartyl Proteases

Cathepsin D, a dimer composed of heavy and light chains interconnected by disulfide bridges, is classified as a lysosomal aspartyl protease. Mutations in the gene encoding cathepsin D have been linked to the development of several types of cancer. Notably, the overexpression of this gene is associated with adverse prognostic outcomes in both prostate and breast cancer [

101,

102]. The initial evidence demonstrating the direct involvement of cathepsin D in cancer metastasis was derived from studies utilizing rat tumor cells, which exhibited an increased in vivo metastatic potential following the overexpression induced by transfection of cathepsin D [

24]. Cathepsin D has been implicated in the activation of growth factors like basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), which are known to promote the growth and angiogenesis of cancer cells [

102]. Beyond its proteolytic function, cathepsin D also promotes cell proliferation and tumor angiogenesis. For example, Liaudet-Coopman and colleagues demonstrated in their study that human cathepsin D, when overexpressed by cancer cells, significantly augmented tumor angiogenesis in tumor xenografts utilizing an athymic mouse model [

23].

Procathepsin, a zymogen secreted by neoplastic cells, has been demonstrated to function as a mitogen in both malignant and stromal cell populations, intriguingly, even following mutations that lead to the loss of catalytic activity. A substantial body of research indicates that procathepsin D can affect various stages of tumorigenesis. Additionally, the inhibition of this protease has been demonstrated to obstruct cancer cell proliferation in both in vitro and in vivo models, thereby suggesting the potential clinical applicability of procathepsin D suppression in oncological practice [

25].

5.1.4. Metalloproteases (MMPs) in Cancer

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are constituents of a family of zinc-dependent endopeptidases that have been associated with various physiological processes, such as wound healing, uterine involution, and organogenesis (

Table 1). Additionally, they are implicated in several pathological conditions, including inflammatory, vascular, autoimmune, and neoplastic disorders [

103,

104,

105]. The role of MMPs in tumorigenesis as a promoter of tumor growth is well established in the literature. MMPs primarily contribute to signaling pathways that facilitate tumor growth through the release of activated growth factors. More specifically, MMPs possess the capacity to modify the bioavailability of growth factors and influence the activity of cell-surface receptors implicated in tumor cell proliferation. This process involves the a-disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM) family members of MMPs, which is categorized into two subgroups: the membrane-bound ADAMs and those characterized by the presence of thrombospondin motifs, referred to as ADAMs with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS) [

3,

106]. Rocks et al., reported that the expression levels of ADAM and ADAMTS proteins are altered across various tumor types, indicating their potential involvement in multiple stages of cancer progression, including carcinogenesis. Conversely, ADAMTS proteins exhibit some contradictory effects; for instance, ADAMTS-1 and ADAMTS-12 display antimetastatic and antiangiogenic properties. One potential explanation for these divergent outcomes is that molecules such as ADAMTS-1 may undergo autoproteolytic cleavage or proteolytic modification of their catalytic sites, which could elucidate these effects [

107].

Studies indicate that the roles of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) family proteases differ at various stages of cancer progression, influenced by the specific type of cancer. Their effects may either promote or inhibit cancer development, depending on various factors including, tumor site, stage, MMP localization, and substrate availability. For instance, MMP-8 has been shown to confer protection against metastasis in breast cancer and to enhance survival in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the tongue. Conversely, MMP-9 may facilitate tumor progression during the process of carcinogenesis, while in certain contexts, it may exhibit anticancer properties during the later stages of cancer progression [

108,

109]. This dual role of MMP-9 is substantiated by findings from various animal model studies, which demonstrated that in mouse models with MMP-9 knockdown genes, there was a diminished incidence of carcinogenesis. However, tumors that developed in MMP-9 deficient mice exhibited significantly greater malignancy. In addition to their function as proteolytic enzymes, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) also fulfill additional roles in cancer [

110,

111]. One of the functions of MMP-12 is its involvement in antimicrobial activity. Similarly, MMP-14 has been characterized as exhibiting DNA-binding effects, which result in significant reprogramming of macrophage function [

110].

6. Conclusions

Proteases play a pivotal role in maintaining homeostasis by regulating various cellular functions and physiological processes, including diverse modalities of cell death. Notably, protease dysfunction leads to altered signal transduction pathways and cellular responses, which are associated with a wide range of diseases and pathological conditions, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, coagulation abnormalities, inflammatory diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, allergies, immune responses, and infections. Proteases initiate signaling cascades that determine whether a cell undergoes programmed cell death, such as apoptosis (caspases), necroptosis (MLKL), autophagy (ATG4), or pyroptosis (gasdermins), or whether it mounts an inflammatory response based on contextual stimuli. Consequently, proteases are crucial components in the regulation of various cellular processes and mechanisms of cell death. Future research should focus on enhancing our understanding of protease biology, and the development of protease-specific inhibitors or biomarkers may facilitate the diagnosis and prognosis of a variety of diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P., A.A. and K.R..; software, C.P. and A.A.; validation, C.P., A.A. and K.R.; resources, C.P. and K.R.; data curation, A.A and A.K..; writing—original draft preparation, C.P. and A.A.; writing—review and editing, C.P., A.K., K.R.; visualization, C.P. and K.R.; supervision, C.P.; project administration, C.P. and K.R..; funding acquisition, C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

N/A.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lopez-Otin, C.; Bond, J.S. Proteases: multifunctional enzymes in life and disease. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 30433-30437. [CrossRef]

- Bialas, A.; Kafarski, P. Proteases as Anti-Cancer Targets - Molecular and Biological Basis for Development of Inhibitor-Like Drugs Against Cancer. Anti-Cancer Agent Me 2009, 9, 728-762. [CrossRef]

- Noël, A.; Jost, M.; Maquoi, E. Matrix metalloproteinases at cancer tumor-host interface. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2008, 19, 52-60. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Silva, J.G.; Español, Y.; Velasco, G.; Quesada, V. The Degradome database: expanding roles of mammalian proteases in life and disease. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, D351-D355. [CrossRef]

- Gurumallesh, P.; Alagu, K.; Ramakrishnan, B.; Muthusamy, S. A systematic reconsideration on proteases. Int J Biol Macromol 2019, 128, 254-267. [CrossRef]

- Neurath, H.; Walsh, K.A. Role of proteolytic enzymes in biological regulation (a review). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1976, 73, 3825-3832. [CrossRef]

- Vicencio, J.M.; Galluzzi, L.; Tajeddine, N.; Ortiz, C.; Criollo, A.; Tasdemir, E.; Morselli, E.; Ben Younes, A.; Maiuri, M.C.; Lavandero, S.; et al. Senescence, apoptosis or autophagy? When a damaged cell must decide its path--a mini-review. Gerontology 2008, 54, 92-99. [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, K.; Pathak, C. Cellular Dynamics of Fas-Associated Death Domain in the Regulation of Cancer and Inflammation. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, K.; Surolia, A.; Pathak, C. Apoptotic potential of Fas-associated death domain on regulation of cell death regulatory protein cFLIP and death receptor mediated apoptosis in HEK 293T cells. J Cell Commun Signal 2012, 6, 155-168. [CrossRef]

- Sukharev, S.A.; Pleshakova, O.V.; Sadovnikov, V.B. Role of proteases in activation of apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 1997, 4, 457-462, doi:DOI 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400263.

- Kidd, V.J.; Lathi, J.M.; Teitz, T. Proteolytic regulation of apoptosis. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2000, 11, 191-201, doi:DOI 10.1006/scdb.2000.0165.

- Yanumula, A.; Cusick, J.K. Biochemistry, Extrinsic Pathway of Apoptosis. In StatPearls; Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: John Cusick declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies., 2024.

- Ranjan, K.; Waghela, B.N.; Vaidya, F.U.; Pathak, C. Cell-Penetrable Peptide-Conjugated FADD Induces Apoptosis and Regulates Inflammatory Signaling in Cancer Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Kesavardhana, S.; Malireddi, R.K.S.; Kanneganti, T.D. Caspases in Cell Death, Inflammation, and Pyroptosis. Annu Rev Immunol 2020, 38, 567-595. [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, K.; Pathak, C. FADD regulates NF-kappaB activation and promotes ubiquitination of cFLIPL to induce apoptosis. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 22787. [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, K.; Pathak, C. Expression of FADD and cFLIP(L) balances mitochondrial integrity and redox signaling to substantiate apoptotic cell death. Mol Cell Biochem 2016, 422, 135-150. [CrossRef]

- Chico, J.F.; Saggau, C.; Adam, D. Proteolytic control of regulated necrosis. Bba-Mol Cell Res 2017, 1864, 2147-2161. [CrossRef]

- McIlwain, D.R.; Berger, T.; Mak, T.W. Caspase Functions in Cell Death and Disease (vol 5, a008656, 2013). Csh Perspect Biol 2015, 7.

- Ranjan, K.; Sharma, A.; Surolia, A.; Pathak, C. Regulation of HA14-1 mediated oxidative stress, toxic response, and autophagy by curcumin to enhance apoptotic activity in human embryonic kidney cells. Biofactors 2014, 40, 157-169. [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.A.; Schnellmann, R.G. Calpains, mitochondria, and apoptosis. Cardiovasc Res 2012, 96, 32-37. [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.X.; Li, X.P.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.F.; Mehta, S.; Feng, Q.P.; Chen, R.Z.; Peng, T.Q. Calpain-1 induces apoptosis in pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells under septic conditions. Microvasc Res 2009, 78, 33-39. [CrossRef]

- Wingrave, J.M.; Schaecher, K.E.; Sribnick, E.A.; Wilford, G.G.; Ray, S.K.; Hazen-Martin, D.J.; Hogan, E.L.; Banik, N.L. Early induction of secondary injury factors causing activation of calpain and mitochondria-mediated neuronal apoptosis following spinal cord injury in rats. J Neurosci Res 2003, 73, 95-104. [CrossRef]

- Berchem, G.; Glondu, M.; Gleizes, M.; Brouillet, J.P.; Vignon, F.; Garcia, M.; Liaudet-Coopman, E. Cathepsin-D affects multiple tumor progression steps: proliferation, angiogenesis and apoptosis. Oncogene 2002, 21, 5951-5955. [CrossRef]

- Liaudet-Coopman, E.; Beaujouin, M.; Derocq, D.; Garcia, M.; Glondu-Lassis, M.; Laurent-Matha, V.; Prébois, C.; Rochefort, H.; Vignon, F. Cathepsin D:: newly discovered functions of a long-standing aspartic protease in cancer and apoptosis. Cancer Lett 2006, 237, 167-179. [CrossRef]

- Vetvicka, V.; Fusek, M. Procathepsin D as a tumor marker, anti-cancer drug or screening agent. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2012, 12, 172-175. [CrossRef]

- Chwieralski, C.E.; Welte, T.; Bühling, F. Cathepsin-regulated apoptosis. Apoptosis 2006, 11, 143-149. [CrossRef]

- Droga-Mazovec, G.; Bojic, L.; Petelin, A.; Ivanova, S.; Romih, R.; Repnik, U.; Salvesen, G.S.; Stoka, V.; Turk, V.; Turk, B. Cysteine cathepsins trigger caspase-dependent cell death through cleavage of Bid and antiapoptotic Bcl-2 homologues. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 19140-19150. [CrossRef]

- Trapani, J.A.; Smyth, M.J. Functional significance of the perforin/granzyme cell death pathway. Nat Rev Immunol 2002, 2, 735-747. [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, J. Granzyme A activates another way to die. Immunol Rev 2010, 235, 93-104.

- Rousalova, I.; Krepela, E. Granzyme B-induced apoptosis in cancer cells and its regulation (Review). Int J Oncol 2010, 37, 1361-1378. [CrossRef]

- Kaminskyy, V.; Zhivotovsky, B. Proteases in autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012, 1824, 44-50. [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, K.; Pathak, C. Expression of cFLIPL Determines the Basal Interaction of Bcl-2 With Beclin-1 and Regulates p53 Dependent Ubiquitination of Beclin-1 During Autophagic Stress. J Cell Biochem 2016, 117, 1757-1768. [CrossRef]

- Shibutani, S.T.; Saitoh, T.; Nowag, H.; Munz, C.; Yoshimori, T. Autophagy and autophagy-related proteins in the immune system. Nat Immunol 2015, 16, 1014-1024. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Ranjan, K.; Singh, V.; Pathak, C.; Pappachan, A.; Singh, D.D. Hydrophilic Acylated Surface Protein A (HASPA) of Leishmania donovani: Expression, Purification and Biophysico-Chemical Characterization. Protein J 2017, 36, 343-351. [CrossRef]

- Duque, T.L.A.; Serrao, T.; Goncalves, A.; Pinto, E.F.; Oliveira-Neto, M.P.; Pirmez, C.; Pereira, L.O.R.; Menna-Barreto, R.F.S. Leishmania (V.) braziliensis infection promotes macrophage autophagy by a LC3B-dependent and BECLIN1-independent mechanism. Acta Trop 2021, 218, 105890. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.W.; Yan, J.; Ranjan, K.; Zhang, X.; Turner, J.R.; Abraham, C. Myeloid Cell Expression of LACC1 Is Required for Bacterial Clearance and Control of Intestinal Inflammation. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 1051-1067. [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, U.; Kaushik, S.; Varticovski, L.; Cuervo, A.M. The chaperone-mediated autophagy receptor organizes in dynamic protein complexes at the lysosomal membrane. Mol Cell Biol 2008, 28, 5747-5763. [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S.; Bandyopadhyay, U.; Sridhar, S.; Kiffin, R.; Martinez-Vicente, M.; Kon, M.; Orenstein, S.J.; Wong, E.; Cuervo, A.M. Chaperone-mediated autophagy at a glance. J Cell Sci 2011, 124, 495-499. [CrossRef]

- Mortimore, G.E.; Lardeux, B.R.; Adams, C.E. Regulation of Microautophagy and Basal Protein-Turnover in Rat-Liver - Effects of Short-Term Starvation. J Biol Chem 1988, 263, 2506-2512.

- Pathak, C.; Vaidya, F.U.; Waghela, B.N.; Jaiswara, P.K.; Gupta, V.K.; Kumar, A.; Rajendran, B.K.; Ranjan, K. Insights of Endocytosis Signaling in Health and Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Numrich, J.; Péli-Gulli, M.P.; Arlt, H.; Sardu, A.; Griffith, J.; Levine, T.; Engelbrecht-Vandré, S.; Reggiori, F.; De Virgilio, C.; Ungermann, C. The I-BAR protein Ivy1 is an effector of the Rab7 GTPase Ypt7 involved in vacuole membrane homeostasis. J Cell Sci 2015, 128, 2278-2292. [CrossRef]

- Tekirdag, K.; Cuervo, A.M. Chaperone-mediated autophagy and endosomal microautophagy: Jointed by a chaperone. J Biol Chem 2018, 293, 5414-5424. [CrossRef]

- Sendler, M.; Mayerle, J.; Lerch, M.M. Necrosis, Apoptosis, Necroptosis, Pyroptosis: It Matters How Acinar Cells Die During Pancreatitis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016, 2, 407-408. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.Y.; Zhang, A.L.; Choksi, S.; Li, W.H.; Li, T.; Zhang, X.M.; Liu, Z.G. Activation of cell-surface proteases promotes necroptosis, inflammation and cell migration. Cell Res 2016, 26, 886-900. [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, S.O.; Behl, B.; Rathinam, V.A. Pyroptosis-induced inflammation and tissue damage. Semin Immunol 2023, 69, 101781. [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Karch, J. Regulation of cell death in the cardiovascular system. Int Rev Cel Mol Bio 2020, 353, 153-209. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, C.; Vaidya, F.U.; Waghela, B.N.; Chhipa, A.S.; Tiwari, B.S.; Ranjan, K. Advanced Glycation End Products Mediated Oxidative Stress and Regulated Cell Death Signaling in Cancer. In Handbook of Oxidative Stress in Cancer: Mechanistic Aspects, Chakraborti, S., Ray, B.K., Roychowdhury, S., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1-16.

- Waghela, B.N.; Vaidya, F.U.; Ranjan, K.; Chhipa, A.S.; Tiwari, B.S.; Pathak, C. AGE-RAGE synergy influences programmed cell death signaling to promote cancer. Mol Cell Biochem 2021, 476, 585-598. [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, S.A.; Palaniyandi, T.; Parthasarathy, U.; Surendran, H.; Viswanathan, S.; Wahab, M.R.A.; Baskar, G.; Natarajan, S.; Ranjan, K. Implications of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and their signaling mechanisms in human cancers. Pathol Res Pract 2023, 248, 154673. [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Chen, H.W.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, K.L.; Zhuge, Y.Z.; Niu, C.; Qiu, J.X.; Rong, X.; Shi, Z.W.; Xiao, J.; et al. Role of pyroptosis in cardiovascular diseases. Int Immunopharmacol 2019, 67, 311-318. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.T.; Xiong, S.Q.; Ye, Z.M.; Hong, Z.G.; Di, A.K.; Tsang, K.M.; Gao, X.P.; An, S.J.; Mittal, M.; Vogel, S.M.; et al. Caspase-11-mediated endothelial pyroptosis underlies endotoxemia-induced lung injury. J Clin Invest 2017, 127, 4124-4135. [CrossRef]

- Oltra, S.S.; Colomo, S.; Sin, L.; Perez-Lopez, M.; Lazaro, S.; Molina-Crespo, A.; Choi, K.H.; Ros-Pardo, D.; Martinez, L.; Morales, S.; et al. Distinct GSDMB protein isoforms and protease cleavage processes differentially control pyroptotic cell death and mitochondrial damage in cancer cells. Cell Death Differ 2023, 30, 1366-1381. [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Tang, D.; Kang, R.; Chen, R. The Versatile Gasdermin Family: Their Function and Roles in Diseases. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 751533. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Sun, Q.; Zhong, X.; Zeng, M.; Zeng, H.; Shi, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Shao, F.; et al. Structural Mechanism for GSDMD Targeting by Autoprocessed Caspases in Pyroptosis. Cell 2020, 180, 941-955 e920. [CrossRef]

- Clancy, D.M.; Sullivan, G.P.; Moran, H.B.T.; Henry, C.M.; Reeves, E.P.; McElvaney, N.G.; Lavelle, E.C.; Martin, S.J. Extracellular Neutrophil Proteases Are Efficient Regulators of IL-1, IL-33, and IL-36 Cytokine Activity but Poor Effectors of Microbial Killing. Cell Rep 2018, 22, 2937-2950. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Gao, W.; Shao, F. Pyroptosis: Gasdermin-Mediated Programmed Necrotic Cell Death. Trends Biochem Sci 2017, 42, 245-254. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Xie, F.; Zhou, X.X.; Wu, Y.C.; Yan, H.Y.; Liu, T.; Huang, J.; Wang, F.W.; Zhou, F.F.; Zhang, L. Role of pyroptosis in inflammation and cancer. Cell Mol Immunol 2022, 19, 971-992. [CrossRef]

- Qadri, S.M.; Bissinger, R.; Solh, Z.; Oldenborg, P.A. Eryptosis in health and disease: A paradigm shift towards understanding the (patho)physiological implications of programmed cell death of erythrocytes. Blood Rev 2017, 31, 349-361. [CrossRef]

- Föller, M.; Huber, S.M.; Lang, F. Erythrocyte programmed cell death. Iubmb Life 2008, 60, 661-668. [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.; Gulbins, E.; Lerche, H.; Huber, S.M.; Kempe, D.S.; Föller, M. Eryptosis, a Window to Systemic Disease. Cell Physiol Biochem 2008, 22, 373-380. [CrossRef]

- Dreischer, P.; Duszenko, M.; Stein, J.; Wieder, T. Eryptosis: Programmed Death of Nucleus-Free, Iron-Filled Blood Cells. Cells-Basel 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Matarrese, P.; Straface, E.; Pietraforte, D.; Gambardella, L.; Vona, R.; Maccaglia, A.; Minetti, M.; Malorni, W. Peroxynitrite induces senescence and apoptosis of red blood cells through the activation of aspartyl and cysteinyl proteases. Faseb J 2005, 19, 416-+. [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, F.C.; Maté, S.; Bakás, L.; Herlax, V. Induction of eryptosis by low concentrations of alpha-hemolysin. Bba-Biomembranes 2015, 1848, 2779-2788. [CrossRef]

- Berg, C.P.; Engels, I.H.; Rothbart, A.; Lauber, K.; Renz, A.; Schlosser, S.F.; Schulze-Osthoff, K.; Wesselborg, S. Human mature red blood cells express caspase-3 and caspase-8, but are devoid of mitochondrial regulators of apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 2001, 8, 1197-1206, doi:DOI 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400905.

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An Iron-Dependent Form of Nonapoptotic Cell Death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060-1072. [CrossRef]

- Nagakannan, P.; Islam, M.I.; Conrad, M.; Eftekharpour, E. Cathepsin B is an executioner of ferroptosis. Bba-Mol Cell Res 2021, 1868. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yu, C.H.; Kang, R.; Kroemer, G.; Tang, D.L. Cellular degradation systems in ferroptosis. Cell Death Differ 2021, 28, 1135-1148. [CrossRef]

- Overholtzer, M.; Mailleux, A.A.; Mouneimne, G.; Normand, G.; Schnitt, S.J.; King, R.W.; Cibas, E.S.; Brugge, J.S. A nonapoptotic cell death process, entosis, that occurs by cell-in-cell invasion. Cell 2007, 131, 966-979. [CrossRef]

- Krishna, S.; Overholtzer, M. Mechanisms and consequences of entosis. Cell Mol Life Sci 2016, 73, 2379-2386. [CrossRef]

- Durgan, J.; Florey, O. Cancer cell cannibalism: Multiple triggers emerge for entosis. Bba-Mol Cell Res 2018, 1865, 831-841. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yang, W.T.; Mai, F.Y.; Liang, J.R.; Luo, J.; Zhou, M.C.; Yu, D.D.; Wang, Y.L.; Li, C.G. Unravelling oncosis: morphological and molecular insights into a unique cell death pathway. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1450998. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.L.; Van Vleet, T.; Schnellmann, R.G. The role of calpain in oncotic cell death. Annu Rev Pharmacol 2004, 44, 349-370, doi:DOI 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121804.

- Ranjan, K.; Hedl, M.; Abraham, C. The E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF186 and RNF186 risk variants regulate innate receptor-induced outcomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118. [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, K.; Hedl, M.; Sinha, S.; Zhang, X.; Abraham, C. Ubiquitination of ATF6 by disease-associated RNF186 promotes the innate receptor-induced unfolded protein response. J Clin Invest 2021, 131. [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Xu, W.J.; Reed, J.C. Cell death and endoplasmic reticulum stress: disease relevance and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2008, 7, 1013-1030. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Hedl, M.; Ranjan, K.; Abraham, C. LACC1 Required for NOD2-Induced, ER Stress-Mediated Innate Immune Outcomes in Human Macrophages and LACC1 Risk Variants Modulate These Outcomes. Cell Rep 2019, 29, 4525-4539 e4524. [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, K. Intestinal Immune Homeostasis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Perspective on Intracellular Response Mechanisms. Gastrointest Disord 2020, 2, 246-266. [CrossRef]

- Ferri, K.F.; Kroemer, G. Organelle-specific initiation of cell death pathways. Nat Cell Biol 2001, 3, E255-E263, doi:DOI 10.1038/ncb1101-e255.

- Momoi, T. Caspases involved in ER stress-mediated cell death. J Chem Neuroanat 2004, 28, 101-105. [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, T.; Yuan, J.Y. Cross-talk between two cysteine protease families: Activation of caspase-12 by calpain in apoptosis. J Cell Biol 2000, 150, 887-894, doi:DOI 10.1083/jcb.150.4.887.

- Saleh, M.; Vaillancourt, J.P.; Graham, R.K.; Huyck, M.; Srinivasula, S.M.; Alnemri, E.S.; Steinberg, M.H.; Nolan, V.; Baldwin, C.T.; Hotchkiss, R.S.; et al. Differential modulation of endotoxin responsiveness by human caspase-12 polymorphisms. Nature 2004, 429, 75-79, doi:DOI 10.1038/nature02451.

- Koblinski, J.E.; Ahram, M.; Sloane, B.F. Unraveling the role of proteases in cancer. Clin Chim Acta 2000, 291, 113-135. [CrossRef]

- Kos, J. Proteases: Role and Function in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Tagirasa, R.; Yoo, E. Role of Serine Proteases at the Tumor-Stroma Interface. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.E.; List, K. Cell surface-anchored serine proteases in cancer progression and metastasis. Cancer Metast Rev 2019, 38, 357-387. [CrossRef]

- Goretzki, L.; Schmitt, M.; Mann, K.; Calvete, J.; Chucholowski, N.; Kramer, M.; Gunzler, W.A.; Janicke, F.; Graeff, H. Effective Activation of the Proenzyme Form of the Urokinase-Type Plasminogen-Activator (Pro-Upa) by the Cysteine Protease Cathepsin-L. Febs Lett 1992, 297, 112-118, doi:Doi 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80339-I.

- Hua, T.; Robitaille, M.; Roberts-Thomson, S.J.; Monteith, G.R. The intersection between cysteine proteases, Ca2+signalling and cancer cell apoptosis*. Bba-Mol Cell Res 2023, 1870. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Liu, X.J.; Li, Z.H.; Huang, Q.; Li, F.; Li, C.Y. Caspase-3 regulates the migration, invasion and metastasis of colon cancer cells. Int J Cancer 2018, 143, 921-930. [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.H.; Fang, W.L.; Li, A.F.Y.; Liang, P.H.; Wu, C.W.; Shy, Y.M.; Yang, M.H. Caspase-3, a key apoptotic protein, as a prognostic marker in gastric cancer after curative surgery. Int J Surg 2018, 52, 266-271. [CrossRef]

- Amptoulach, S.; Lazaris, A.C.; Giannopoulou, I.; Kavantzas, N.; Patsouris, E.; Tsavaris, N. Expression of caspase-3 predicts prognosis in advanced noncardia gastric cancer. Med Oncol 2015, 32. [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, Y.I.; Kuranaga, E. Caspase-dependent non-apoptotic processes in development. Cell Death Differ 2017, 24, 1422-1430. [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Y.; Koga, H.; Araki, N.; Mugita, N.; Fujita, N.; Takeshima, H.; Nishi, T.; Yamashima, T.; Saido, T.C.; Yamasaki, T.; et al. The involvement of calpain-dependent proteolysis of the tumor suppressor NF2 (merlin) in schwannomas and meningiomas. Nat Med 1998, 4, 915-922. [CrossRef]

- Lakshmikuttyamma, A.; Selvakumar, P.; Kanthan, R.; Kanthan, S.C.; Sharma, R.K. Overexpression of -calpain in human colorectal adenocarcinomas. Cancer Epidem Biomar 2004, 13, 1604-1609.

- Xu, F.K.; Gu, J.; Lu, C.L.; Mao, W.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Q.L.; Liu, Z.H.; Chu, Y.W.; Liu, R.H.; Ge, D. Calpain-2 Enhances Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Progression and Chemoresistance to Paclitaxel via EGFR-pAKT Pathway. Int J Biol Sci 2019, 15, 127-137. [CrossRef]

- Storr, S.J.; Carragher, N.O.; Frame, M.C.; Parr, T.; Martin, S.G. The calpain system and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2011, 11, 364-374. [CrossRef]

- Vasiljeva, O.; Turk, B. Dual contrasting roles of cysteine cathepsins in cancer progression: Apoptosis versus tumour invasion. Biochimie 2008, 90, 380-386. [CrossRef]

- Soond, S.M.; Kozhevnikova, M.V.; Townsend, P.A.; Zamyatnin, A.A. Cysteine Cathepsin Protease Inhibition: An update on its Diagnostic, Prognostic and Therapeutic Potential in Cancer. Pharmaceuticals-Base 2019, 12. [CrossRef]

- Vizovisek, M.; Fonovic, M.; Turk, B. Cysteine cathepsins in extracellular matrix remodeling: Extracellular matrix degradation and beyond. Matrix Biol 2019, 75-76, 141-159. [CrossRef]

- Foghsgaard, L.; Wissing, D.; Mauch, D.; Lademann, U.; Bastholm, L.; Boes, M.; Elling, F.; Leist, M.; Jäättelä, M. Cathepsin B acts as a dominant execution protease in tumor cell apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor. J Cell Biol 2001, 153, 999-1009, doi:DOI 10.1083/jcb.153.5.999.

- Nagaraj, N.S.; Vigneswaran, N.; Zacharias, W. Cathepsin B mediates TRAIL-induced apoptosis in oral cancer cells. J Cancer Res Clin 2006, 132, 171-183. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.; Vázquez, J.; Corte, M.D.; Lamelas, M.; Bongera, M.; Corte, M.G.; Alvarez, A.; Allende, M.; Gonzalez, L.; Sánchez, M.; et al. Clinical significance of cathepsin D concentration in tumor cytosol of primary breast cancer. Int J Biol Marker 2005, 20, 103-111, doi:Doi 10.1177/172460080502000204.

- Zhu, S.; Li, Z. Proteases and Cancer Development. In Role of Proteases in Cellular Dysfunction, Dhalla, N.S., Chakraborti, S., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2014; pp. 129-145.

- Egeblad, M.; Werb, Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer 2002, 2, 161-174. [CrossRef]

- Parks, W.C.; Wilson, C.L.; López-Boado, Y.S. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2004, 4, 617-629. [CrossRef]

- Page-McCaw, A.; Ewald, A.J.; Werb, Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 2007, 8, 221-233. [CrossRef]

- Cal, S.; López-Otín, C. ADAMTS proteases and cancer. Matrix Biol 2015, 44-46, 77-85. [CrossRef]

- Rocks, N.; Paulissen, G.; El Hour, M.; Quesada, F.; Crahay, C.; Gueders, M.; Foidart, J.M.; Noel, A.; Cataldo, D. Emerging roles of ADAM and ADAMTS metalloproteinases in cancer. Biochimie 2008, 90, 369-379. [CrossRef]

- Decock, J.; Hendrickx, W.; Thirkettle, S.; Gutiérrez-Fernández, A.; Robinson, S.D.; Edwards, D.R. Pleiotropic functions of the tumor- and metastasis-suppressing matrix metalloproteinase-8 in mammary cancer in MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice. Breast Cancer Res 2015, 17. [CrossRef]

- Deryugina, E.I.; Quigley, J.P. Pleiotropic roles of matrix metalloproteinases in tumor angiogenesis: Contrasting, overlapping and compensatory functions. Bba-Mol Cell Res 2010, 1803, 103-120. [CrossRef]

- Shay, G.; Lynch, C.C.; Fingleton, B. Moving targets: Emerging roles for MMPs in cancer progression and metastasis. Matrix Biol 2015, 44-46, 200-206. [CrossRef]

- Gialeli, C.; Theocharis, A.D.; Karamanos, N.K. Roles of matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression and their pharmacological targeting. Febs J 2011, 278, 16-27. [CrossRef]

- Willbold, R.; Wirth, K.; Martini, T.; Sultmann, H.; Bolenz, C.; Wittig, R. Excess hepsin proteolytic activity limits oncogenic signaling and induces ER stress and autophagy in prostate cancer cells. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 601. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Imai, Y.; Nakayama, H.; Takahashi, K.; Takio, K.; Takahashi, R. A serine protease, HtrA2, is released from the mitochondria and interacts with XIAP, inducing cell death. Mol Cell 2001, 8, 613-621. [CrossRef]

- Kummari, R.; Dutta, S.; Chaganti, L.K.; Bose, K. Discerning the mechanism of action of HtrA4: a serine protease implicated in the cell death pathway. Biochem J 2019, 476, 1445-1463. [CrossRef]

- Kajiwara, Y.; Schiff, T.; Voloudakis, G.; Gama Sosa, M.A.; Elder, G.; Bozdagi, O.; Buxbaum, J.D. A critical role for human caspase-4 in endotoxin sensitivity. J Immunol 2014, 193, 335-343. [CrossRef]

- Shalini, S.; Dorstyn, L.; Dawar, S.; Kumar, S. Old, new and emerging functions of caspases. Cell Death Differ 2015, 22, 526-539. [CrossRef]

- Page-McCaw, A.; Ewald, A.J.; Werb, Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007, 8, 221-233. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).