Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

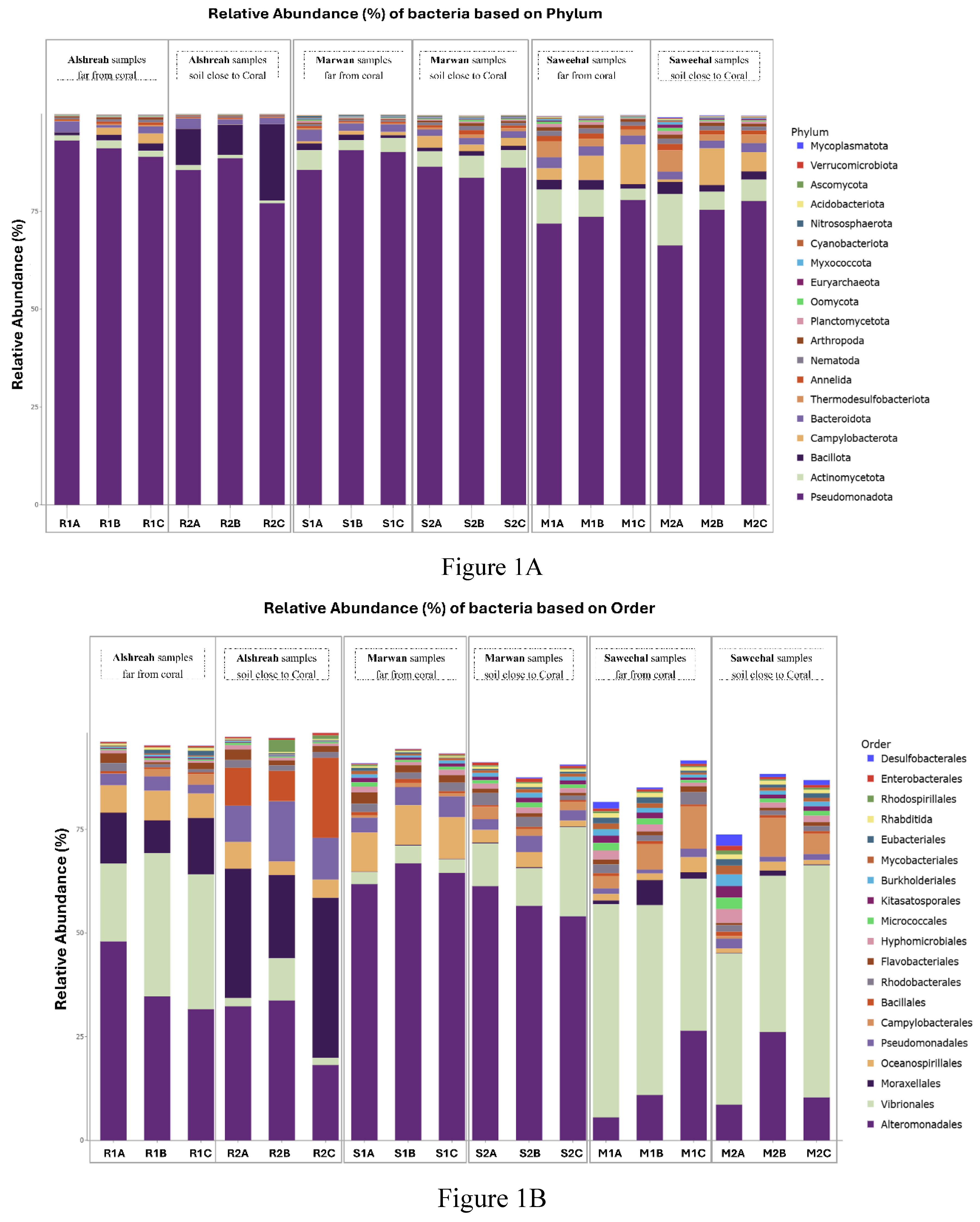

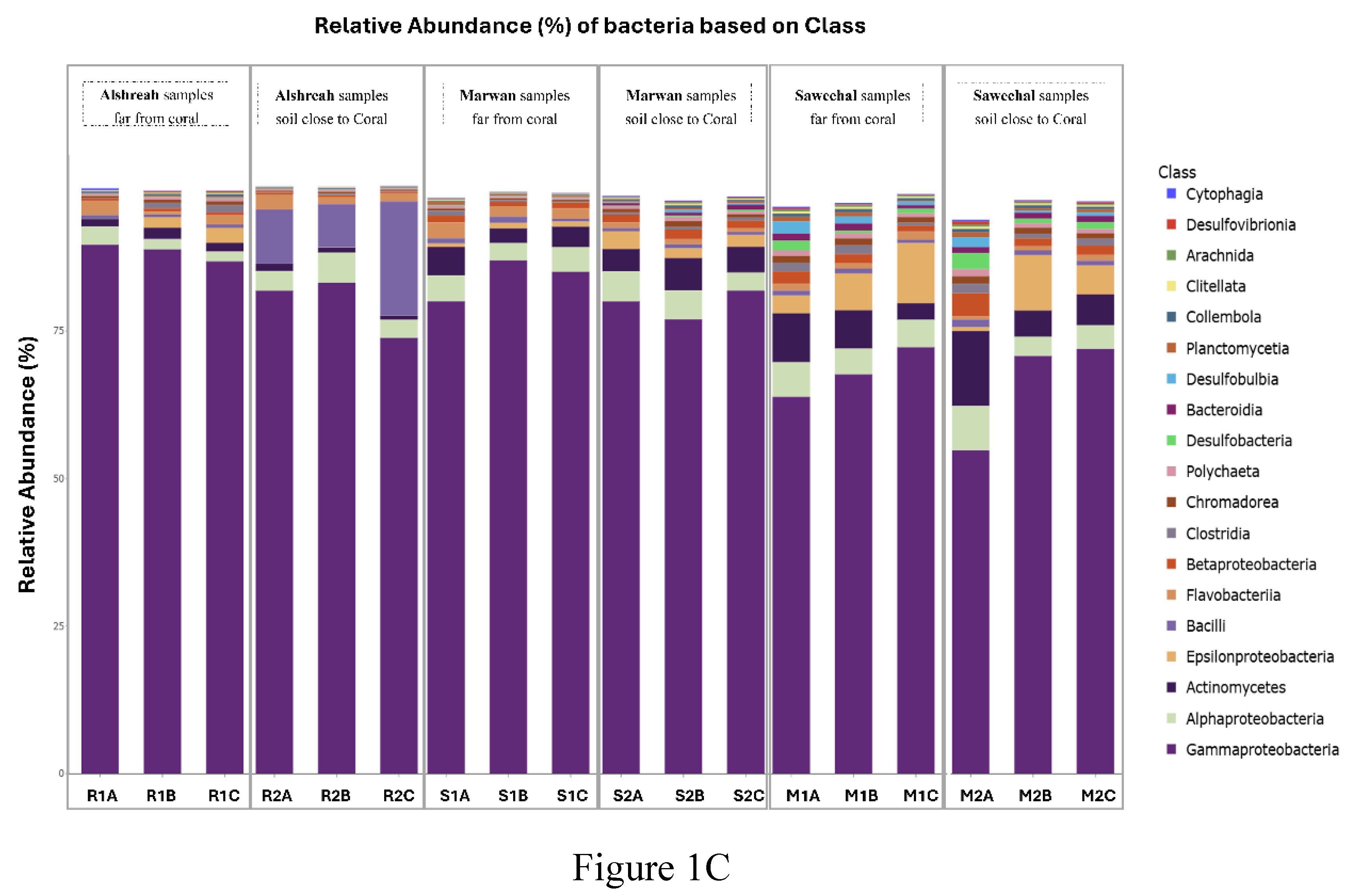

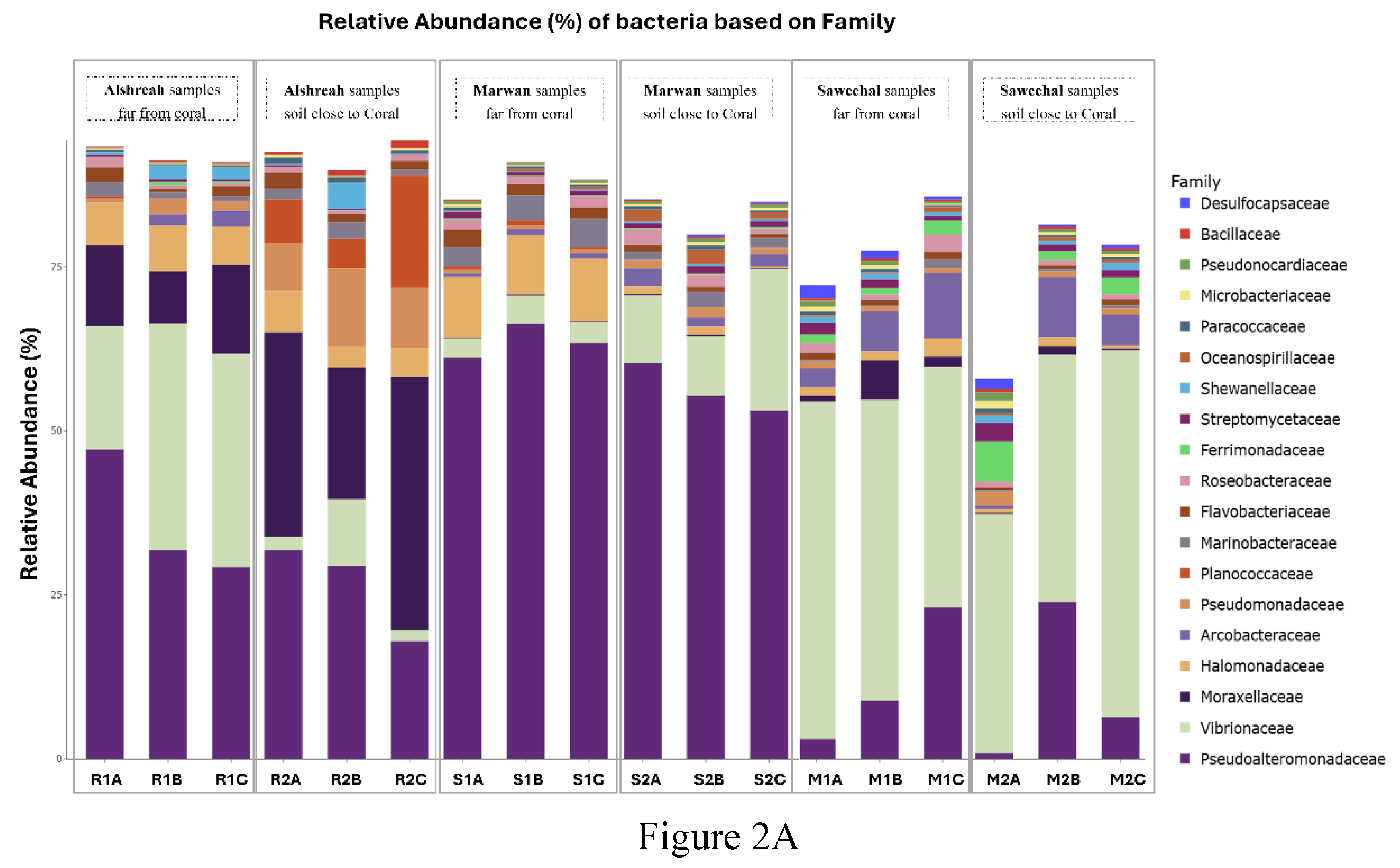

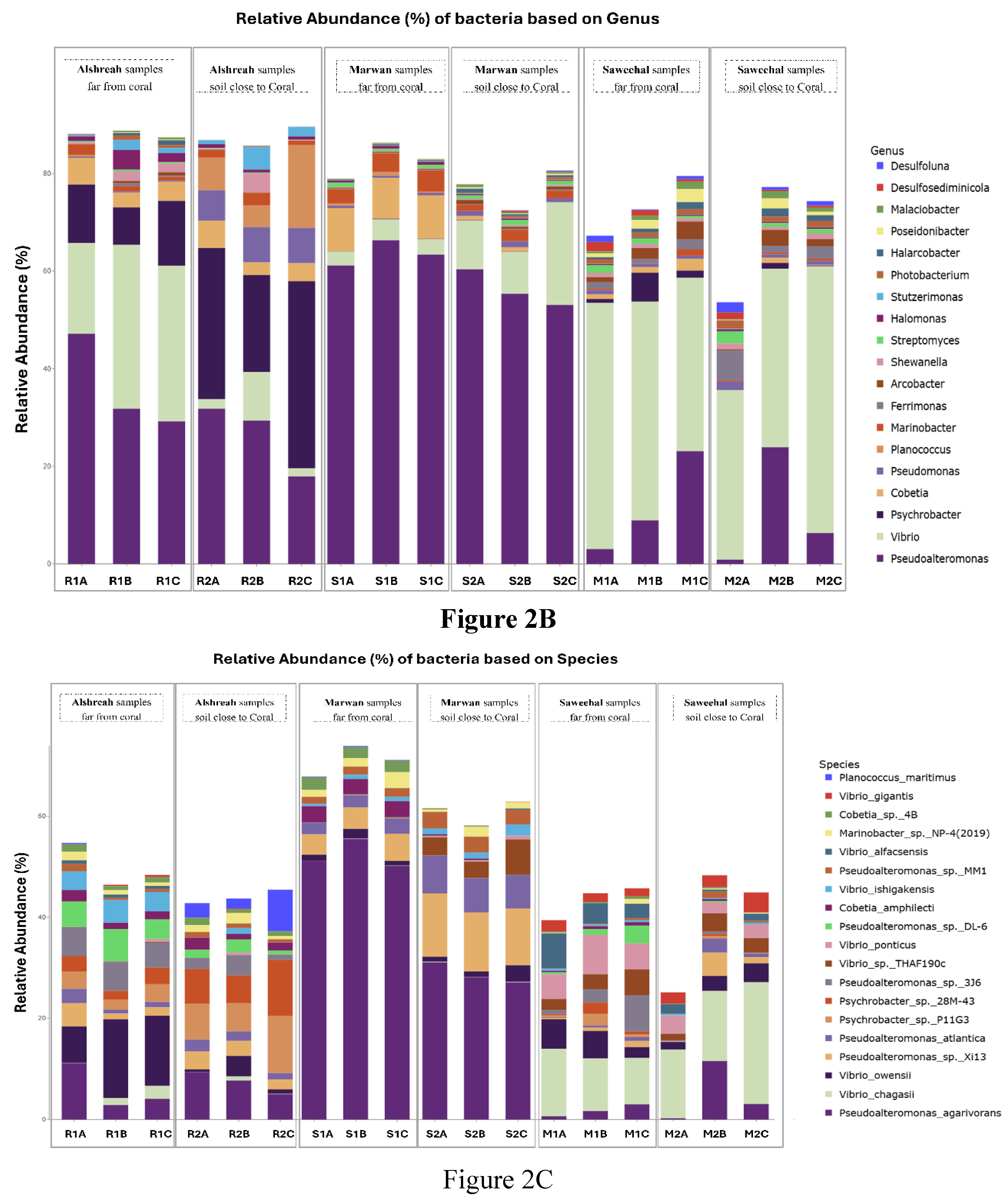

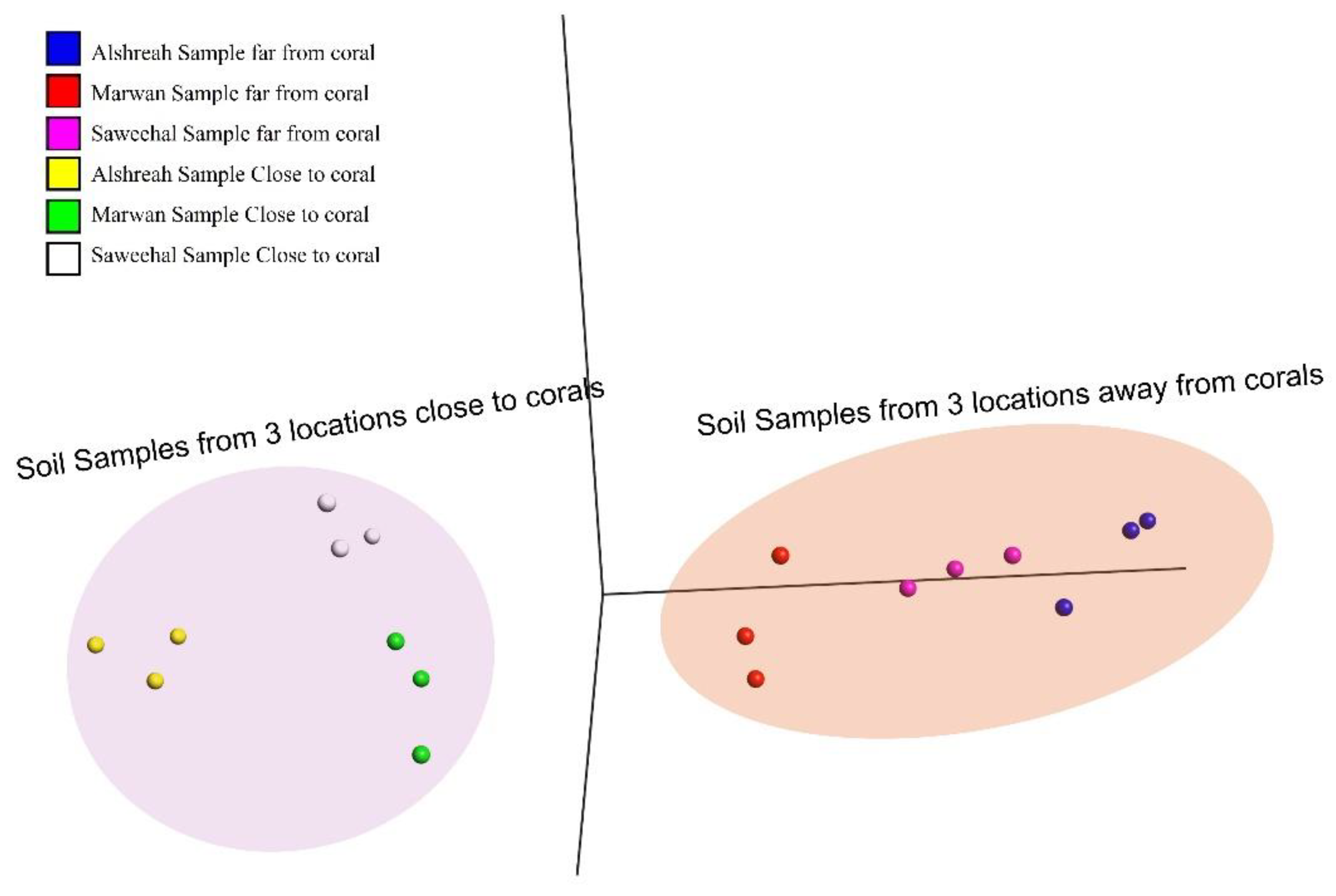

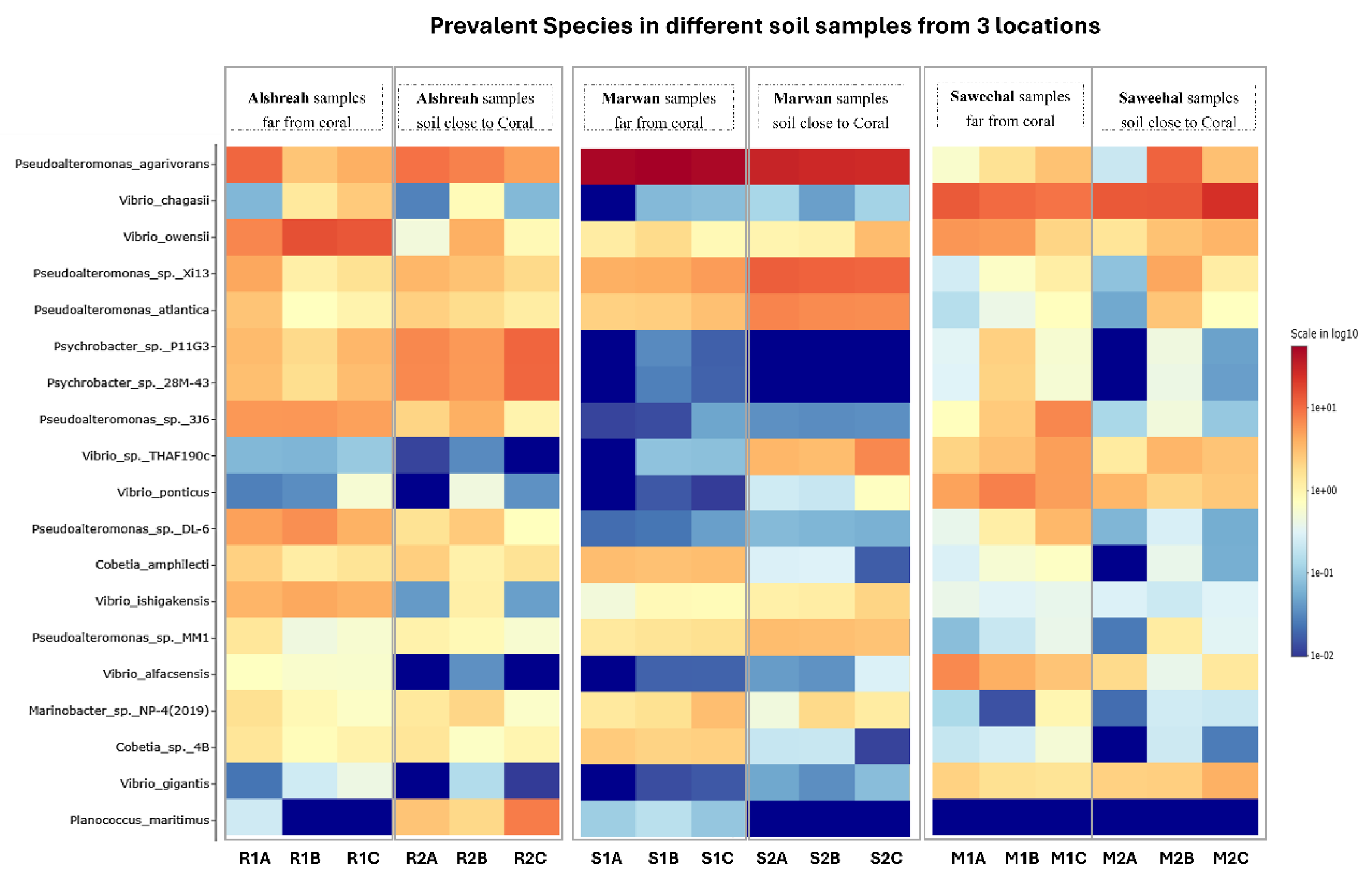

The coral microbiome is highly related to the overall health and the survival and proliferation of coral reefs. As the Red Sea's unique physiochemical characteristics, such a significant north-south temperature and salinity gradient, make it a very intriguing research system. However, the Red Sea is rather isolated, with a very diversified ecosystem rich in coral communities, its makeup of the coral-associated microbiome remains little understood. Therefore, comprehending the makeup and dispersion of the endogenous microbiome associated with coral is crucial for understanding how the coral microbiome coexists and interacts, as well as its contribution to temperature tolerance and resistance against possible pathogens. Here we investigate, metgenomic sequencing targeting the 16S rRNA was performed using DNAs from the sediment samples to identify the coral microbi-ome and to understand the dynamics of microbial taxa and genes in the surface mucous layer (SML) microbiome of the coral communities in three distinct areas close to and far from coral communi-ties in the Red Sea. These findings highlighted the genomic array of the microbiome in three areas around and beneath the coral communities, an revealed distinct bacterial communities in each group, where Pseudoalteromonas agarivorans (30%), Vibrio owensii (11%), and Pseudoalteromonas sp. Xi13 (10%) were the most predominant species in samples closer to coral (a coral-associated mi-crobiome), with the domination of Pseudoalteromonas_agarivorans and Vibrio_owensii in Alshreah samples distant from coral, while Pseudoalteromonas_sp._Xi13 was more abundant in closer sam-ples.Moreover, Proteobacteria such as Pseudoalteromonas, Pseudomonas and Cyanobacteria were the most prevalent phyla of coral microbiome. Further in Saweehal showed highest diversity far from corals 52.8% and in Alshreah close (7.35%), than at Marwan ( 1.75%). The microbial community was less diversified in the samples from Alshreah Far (5.99%) and Marwan Far (1.75%), which had comparatively lower values for all indices. Also, Vibrio species were the most prevalent microor-ganisms in the coral mucus, and the prevalence of these bacteria is significantly higher than those found in the surrounding saltwater. These findings reveal that there is a notable difference in mi-crobial diversity across the various settings and locales, revealing that geographic variables and coral closeness affect the diversity of microbial communities. There were significant differences in microbial community composition regarding the proximity to coral. Besides, there were strong pos-itive correlations between genera Pseudoalteromonas and Vibrio in close-to-coral environments, suggesting that these bacteria may play a synergistic role in immuring coral, rising its tolerance to-wards environmental stress and overall coral health.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

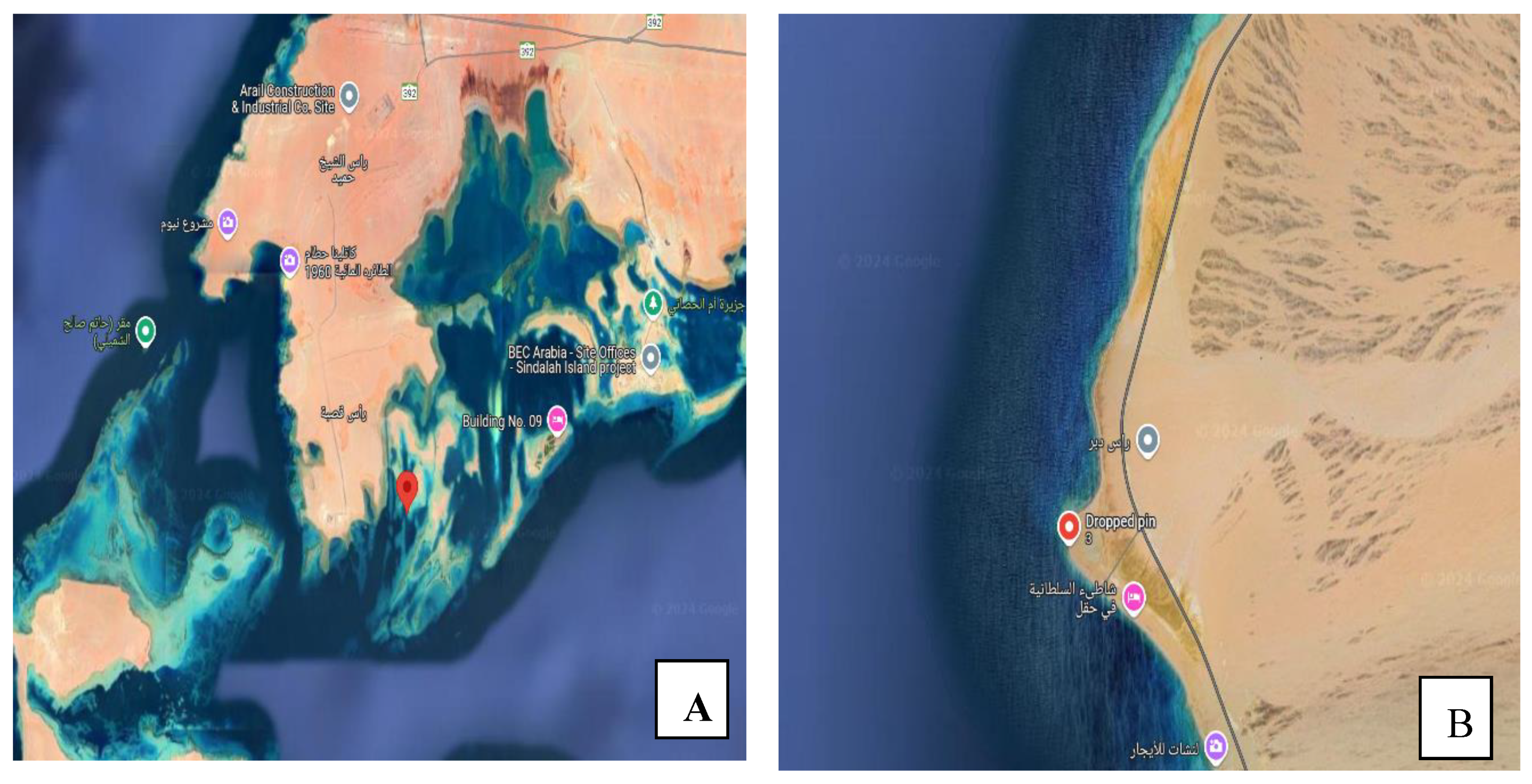

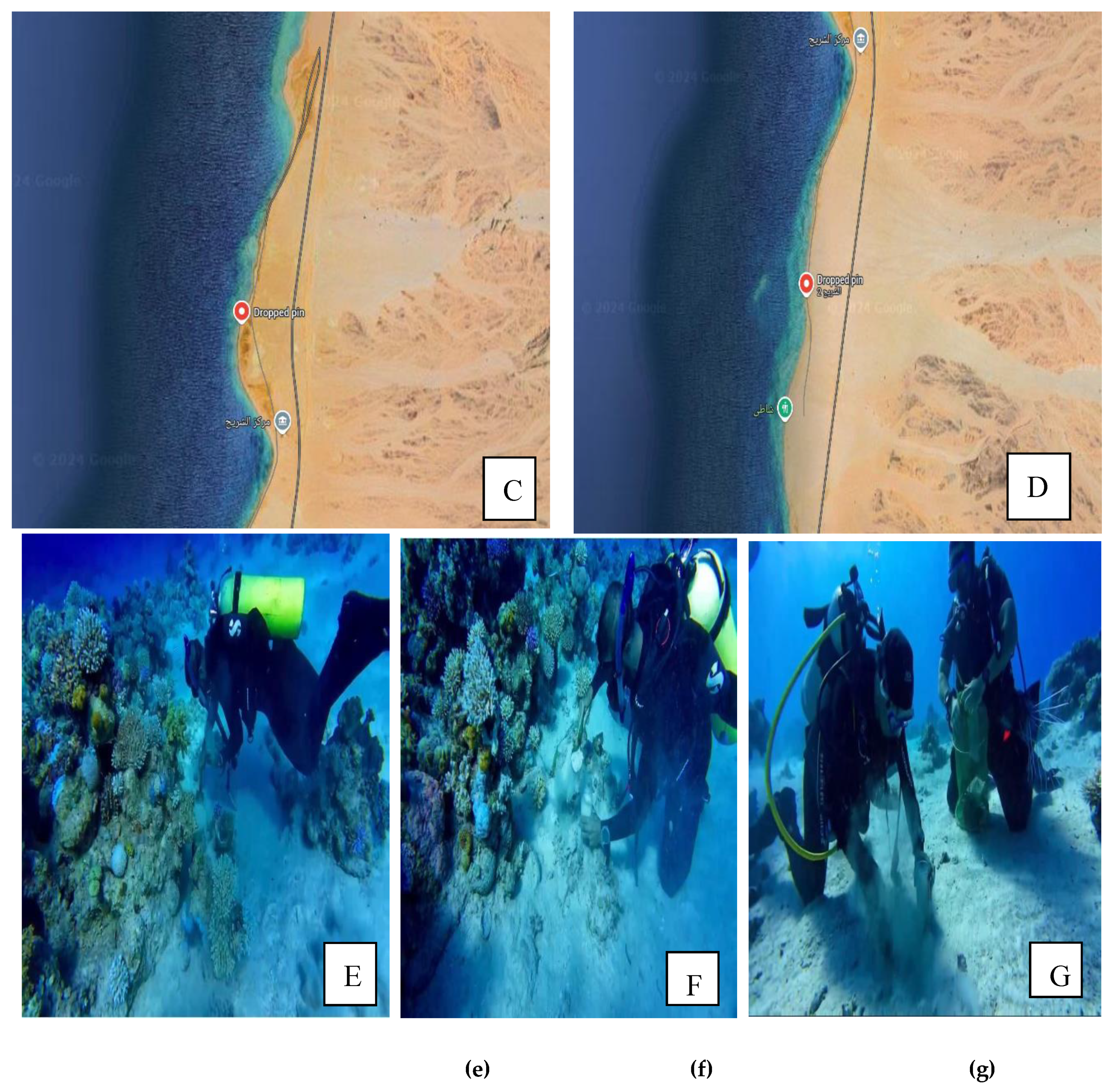

2.1. Study Location and Sampling

2.2. Isolation and Quantitative Analysis of DNA

2.3. Setting up the Library

2.4. Cluster Generation and Sequencing

2.5. Data Generation

2.6. Gene Prediction

3. Results

Study Site Characteristics

| Genus | Alshreah | Saweehal | Marwan | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1A-R1C (%) Far from Corals |

R2A-R2C (%) Close to Corals |

S1A-S1C (%) Far from Corals |

S2A-S2C (%) Close to Corals |

M1A-M1C (%) Far from Corals |

M2A-M2C (%) Close to Corals |

|

| Pseudoalteromonas | 36 | 26 | 63 | 57 | 13 | 10 |

| Vibrio | 28 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 44 | 42 |

| Psychrobacter | 11 | 29 | ~1 | ~1 | 2 | 2 |

| Cobetia | 4 | 4 | 9 | 7 | 3 | 2 |

| Pseudomonas | ~1 | 7 | ~1 | ~1 | 3 | 4 |

- COG0841-Cation/multidrug efflux pump: The category of COG0841, like far-from-coral samples, dominated close-to-coral samples with TPM ranging from 4,165 to 7,543. These efflux pumps could be contributing toward cellular integrity and environmental responses possibly in association with defense mechanisms mediated by coral-associated microbes.

- COG0840: Methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein: Proteins in this category were also highly represented (average TPM = 4,338–6,524), which reflects their participation in microbial responses to chemical gradients and signaling in the coral-associated environment.

- COG0642-Signal transduction histidine kinase: This category showed a high level of abundance (average TPM = 4,220–5,166) in coral-associated samples, indicating active regulation of the microbial signaling pathways in the presence of the coral ecosystem.

- COG1012-NAD-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenases: These metabolism and detoxification enzymes were significantly enriched in the near-coral samples (average TPM = 4,347–4,649), reflecting the metabolic shifts microbes might undergo in response to coral-driven nutrient environments.

- COG0243-Anaerobic dehydrogenases, usually selenocysteine-containing: This functional category has TPM values of about 4,124, and this would reflect the microbial adaptation to oxygen-limited environments that could be a reflection of anaerobic or microaerophilic conditions near the coral.

4. Discussion REFERENCE 61-92 ADDED

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mohamed, A.R.; Ochsenkühn, M.A.; Kazlak, A.M.; Moustafa, A.; Amin, S.A. The coral microbiome: towards an understanding of the molecular mechanisms of coral–microbiota interactions. FEMS Microbiology 2023, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspers, C.; Fraune, S.; Arnold, A.E.; et al. Resolving structure and function of metaorganisms through a holistic framework combining reductionist and integrative approaches. Zoology 2019, 133, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, S.J.; Singleton, C.M.; Chan, C.X.; et al. A genomic view of the reef building coral Porites lutea and its microbial symbionts. Nat Microbiol 2019, 4, 2090–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, R.S.; Sweet, M.; Villela, H.D.M.; et al. Coral probiotics: premise, promise, prospects. Annu Rev Anim Biosci 2021, 9, 265–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohwer, F.; Seguritan, V.; Azam, F.; et al. Diversity and distribution of coral-associated bacteria. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 2002, 243, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, E.; Koren, O.; Reshef, L.; et al. The role of microorganisms in coral health, disease and evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol 2007, 5, 355–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, E.; Zilber-Rosenberg, I. The hologenome concept of evolution after 10 years. Microbiome 2018, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilber-Rosenberg, I.; Rosenberg, E. Microbial-driven genetic variation in holobionts. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2021, 45, fuab022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscatine, L. The role of symbiotic algae in carbon and energy flux in reef corals. In: Dubinsky Z (ed.), Ecosystems of the World. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1990,75–87.

- Morris, L.A.; Voolstra, C.R.; Quigley, K.M.; et al. Nutrient availability and metabolism affect the stability of coral–Symbiodiniaceae symbioses. Trends Microbiol 2019, 27, 678–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, D.G.; Morrow, K.M.; Webster, N.S. Insights into the coral microbiome: underpinning the health and resilience of reef ecosystems. Annu Rev Microbiol 2016, 70, 317–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Oppen, M.J.H.; Blackall, L.L. Coral microbiome dynamics, functions and design in a changing world. Nat Rev Microbiol 2019, 17, 557–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackall, L.L.; Wilson, B.; van Oppen, M.J. Coral—the world’smost diverse symbiotic ecosystem. Mol Ecol 2015, 24, 5330–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huggett, M.J.; Apprill, A. Coral microbiome database: integration of sequences reveals high diversity and relatedness of coral associated microbes. Environ Microbiol Rep 2019, 11, 372–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Guo, Y.; Jia, Y.; et al. Diversity, function and evolution of marine microbe genomes. bioRxiv 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, M.; Grupstra, C.G.B.; Barreto, MM.; et al. Coral bacterial community structure responds to environmental change in a host-specific manner. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voolstra, C.R.; Ziegler, M. Adapting with microbial help: microbiome flexibility facilitates rapid responses to environmental change. BioEssays 2020, 42, 2000004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meunier, V.; Geissler, L.; Bonnet, S.; et al. Microbes support enhanced nitrogen requirements of coral holobionts in a high CO2 environment. Mol Ecol 2021, 30, 5888–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, M.; Villela, H.; Keller-Costa, T.; et al. Insights into the cultured bacterial fraction of corals. m Systems 2021, 6, e0124920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, A.; Fairoz, M.; Kelly, L.; et al. Global microbialization of coral reefs. Nat Microbiol 2016, 1, 16042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, F.J.; McMinds, R.; Smith, S.; et al. Coral-associated bacteria demonstrate phylosymbiosis and cophylogeny. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanwonterghem, I.; Webster, N.S. Coral reef microorganisms in a changing climate. iScience 2020, 23, 100972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wangpraseurt, D.; Jacques, S.L.; Petrie, T.; et al. Monte Carlo modeling of photon propagation reveals highly scattering coral tissue. Front Plant Sci 2016, 7, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pernice, M.; Raina, J.B.; Radecker, N.; et al. Down to the bone: the role of overlooked endolithic microbiomes in reef coral health. ISME J 2020, 14, 325–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, M.J.; Croquer, A.; Bythell, J.C. Bacterial assemblages differ between compartments within the coral holobiont. Coral Reefs 2010, 30, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, D.C.A.; Salles, J.F.; Calderon, E.N.; et al. Coral bacterial-core abundance and network complexity as proxies for anthropogenic pollution. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neave, M.J.; Michell, C.T.; Apprill, A.; et al. Endozoicomonas genomes reveal functional adaptation and plasticity in bacterial strains symbiotically associated with diverse marine hosts. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 40579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthew J. Neave, Amy Apprill, Greta Aeby, Sou Miyake, and Christian R. Voolstra. Microbial Communities of Red Sea Coral Reefs, Coral reef of the World 11, Christian R. Voolstra Michael L. Berumen. Springer, Nature Switzerland AG 2019, Vol 11; 53-68.

- Pogoreutz, C.; Voolstra, C.R.; Rädecker, N.; et al. The coral holobiont highlights the dependence of cnidarian animal hosts on their associated microbes. In: Bosch TCG, Hadfield, M.G.; (eds). Cellular Dialogues in the Holobiont. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2020.

- Falkowski, P.G.; Dubinsky, Z.; Muscatine, L.; et al. Population control in symbiotic corals. Bioscience 1993, 43, 606–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunning, R.; Muller, E.B.; Gates, R.D.; et al. A dynamic bioenergetic model for coral–Symbiodinium symbioses and coral bleaching as an alternate stable state. J Theor Biol 2017, 431, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscatine, L.; Porter, J.W. Reef corals: mutualistic symbioses adapted to nutrient-poor environments. Bioscience 1977, 27, 454–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lema, K.A.; Willis, B.L.; Bourne, D.G. Corals form characteristic associations with symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 2012, 78, 3136–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Douglas, A. Essential amino acid synthesis and nitrogen recycling in an alga–invertebrate symbiosis. Mar Biol 1999, 135, 219–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yellowlees, D.; Rees, T.A.V.; Leggat, W. Metabolic interactions between algal symbionts and invertebrate hosts. Plant Cell Environ 2008, 31, 679–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynaud, S.; Martinez, P.; Houlbrèque, F.; et al. Effect of light and feeding on the nitrogen isotopic composition of a zooxanthellate coral: role of nitrogen recycling. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 2009, 392, 103–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, N.D.; Lesser, M.P. Diazotrophic diversity in the Caribbean coral, Montastraea cavernosa. Arch Microbiol 2013, 195, 853–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lema, K.A.; Bourne, D.G.; Willis, B.L. Onset and establishment of diazotrophs and other bacterial associates in the early life history stages of the coral Acropora millepora. Mol Ecol 2014, 23, 4682–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimes, N.E.; Van Nostrand, J.D.; Weil, E.; et al. Microbial functional structure of Montastraea faveolata, an important Caribbean reef building coral, differs between healthy and yellow-band diseased colonies. Environ Microbiol 2010, 12, 541–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rädecker, N.; Pogoreutz, C.; Gegner, H.M.; et al. Heat stress reduces the contribution of diazotrophs to coral holobiont nitrogen cycling. ISME J 2022, 16, 1110–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, J.R.; Amin, S.A.; Raina, J.B.; et al. Zooming in on the phycosphere: the ecological interface for phytoplankton–bacteria relationships. Nat Microbiol 2017, 2, 17065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirri, E.; Pohnert, G. Algae–bacteria interactions that balance the planktonic microbiome. New Phytol 2019, 223, 100–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgadillo-Ordoñez, N.; Raimundo, I.; Barno, A.R.; Osman, E.O.; Villela, H.; Bennett-Smith, M.; Voolstra, C.R.; Benzoni, F.; Peixoto, R.S. Red Sea Atlas of Coral-Associated Bacteria Highlights Common Microbiome Members and Their Distribution across Environmental Gradients. Micro 2022, 10, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, E.O.; Suggett, D.J.; Voolstra, C.R.; Pettay, D.T.; Clark, D.R.; Pogoreutz, C.; Sampayo, E.M.; Warner, M.E.; Smith, D.J. Coral Microbiome composition along the northern Red Sea suggests high plasticity of bacterial and specificity of endosymbiotic dinoflagellate communities. Microbiome 2020, 8, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, M.; Roik, A.; Porter, A.; Zubier, K.; Mudarris, M.S.; Ormond, R.; Voolstra, C.R. Coral microbial community dynamics in response to anthropogenic impacts near a major city in the Central Red Sea. Mar Pollut Bull 2016, 105, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antony, C.P.; Peixoto, R.S. Unlocking the genomic potential of Red Sea coral probiotics Inês Raimundo, Phillipe M. Rosado, Adam R. Barno. Scientifc Reports 2024, 14, 14514. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, R.; Antonius, A.; Abigail Renegar, D. The skeleton eroding band disease on coral reefs of Aqaba, Red Sea. Mar Ecol 2004, 25, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roik, A.; Röthig, T.; Roder, C.; Ziegler, M.; Kremb, S.G.; Voolstra, C.R. Year-long monitoring of Physico-chemical and biological variables provide a comparative baseline of coral reef functioning in the Central Red Sea. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0163939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röthig, T.; Ochsenkühn, M.A.; Roik, A.; van der Merwe, R.; Voolstra, C.R. Long-term salinity tolerance is accompanied by major restructuring of the coral bacterial microbiome. Mol Ecol 2016, 25, 1308–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röthig, T.; Roik, A.; Yum, L.K.; Voolstra, C.R. Distinct bacterial microbiomes associate with the Deep-Sea coral Eguchipsammia fistula from the Red Sea and from aquaria settings. Front Mar Sci 2017, 4, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaza, D.F.G.; Cramp, R.L.; Franklin, C.E. Living in polluted waters: A meta-analysis of the effects of nitrate and interactions with other environmental stressors on freshwater taxa. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 261, 114091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Liu, C.M.; Luo, R.; Sadakane, K.; Lam, T.W. MEGAHIT: An ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1674–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, R.J.; Jones, S.E.; Eiler, A.; McMahon, K.D.; Bertilsson, S. A guide to the natural history of freshwater lake bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011, 75, 14–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, D.; Chen, G.L.; Locascio, P.F.; Land, M.L.; Larimer, F.W.; Hauser, L.J. Prodigal: Prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinform. 2010, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-W.; Simmons, B.A.; Singer, S.W. MaxBin 2.0: an automated binning algorithm to recover genomes from multiple metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics, 2016, 32, 605–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzel, P.; et al. Fast and sensitive taxonomic classification for metagenomics with Kaiju. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, W.H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software, 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. (2016) ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag, New York. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Eils, R.; Schlesner, M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 2847–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, M.; Villela, H.; Keller-Costa, T.; Costa, R.; Romano, S.; Bourne, D.G.; Cárdenas, A.; Huggett, M.J.; Kerwin, A.H.; Kuek, F.; et al. Insights into the cultured bacterial fraction of corals. mSystems. 2021, 6, e01249-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, F.J.; McMinds, R.; Smith, S.; et al. Coral-associated bacteria demonstrate phylosymbiosis and cophylogeny. Nat Commun. 2018, 9, 4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, Y.; Civiello, M.; Bell, S.C.; et al. Integrated approach to understanding the onset and pathogenesis of black band disease in corals. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 752–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriarty, T.; Leggat, W.; Huggett, M. J.; Ainsworth, T. Coral disease causes, consequences, and risk within coral restoration. Trends in Microbiology, 2020, 28, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, M.; Huang, J.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Wu, R.; He, H.; Wang, J. Diversity of the microbial community and cultivable protease-producing bacteria in the sediments of the Bohai Sea, Yellow Sea and South China Sea. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J. Bacterial diversity in the surface sediments of the hypoxic zone near the Changjiang Estuary and in the East China Sea. MicrobiologyOpen 2016, 5, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.W.; Liu, C.C.; Chiu, Y.S.; Liu, J.T. Spatiotemporal variation of Gaoping River plume observed by Formosat-2 high resolution imagery. J. Mar. Syst. 2014, 132, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, A.; Haldar, A.; Bhattacharyya, M.; Ghosh, A. Anthropogenic influence shapes the distribution of antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB) in the sediment of Sundarban estuary in India. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 647, 1626–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qian, P.Y. Conservative fragments in bacterial 16S rRNA genes and primer design for 16S ribosomal DNA amplicons in metagenomic studies. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.-Y.; Wang, G.-L.; Li, D.; Zhao, D.-L.; Qin, Q.-L.; Chen, X.-L.; Chen, B.; Zhou, B.-C.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-Z. Diversity of both the cultivable protease-producing bacteria and bacterial extracellular proteases in the coastal sediments of King George Island, Antarctica. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Han, X.X.; Chen, X.L.; Dang, H.Y.; Xie, B.B.; Qin, Q.L.; Shi, M.; Zhou, B.C.; Zhang, Y.Z. Diversity of cultivable protease-producing bacteria in sediments of Jiaozhou Bay, China. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röthig, T.; Yum, L.K.; Kremb, S.G.; Roik, A.; Voolstra, C.R. Microbial community composition of deep-sea corals from the Red Sea provides insight into functional adaption to a unique environment. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neave, M.J.; Michell, C.T.; Apprill, A.; Voolstra, C.R. Endozoicomonas genomes reveal functional adaptation and plasticity in bacterial strains symbiotically associated with diverse marine hosts. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosado, P.M.; Leite, D.C.A.; Duarte, G.A.S.; Chaloub, R.M.; Jospin, G.; da Rocha, U.N.; Saraiva, J.P.; Dini-Andreote, F.; Eisen, J.A.; Bourne, D.G.; et al. Marine probiotics: Increasing coral resistance to bleaching through microbiome manipulation. ISME J. 2019, 13, 921–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, K.; Lu, C.-Y.; Chiang, P.-W.; Wada, N.; Yang, S.-H.; Chan, Y.-F.; Chen, P.-Y.; Chang, H.-Y.; Chiou, Y.-J.; Chou, M.-S.; et al. Comparative genomics: Dominant coral-bacterium Endozoicomonas acroporae metabolizes dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP). ISME J. 2020, 14, 1290–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, F.E.; Bell, T.G.; Yang, M.; Suggett, D.J.; Steinke, M. Air exposure of coral is a significant source of dimethylsulfide (DMS) to the atmosphere. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 36031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, R.S.; Rosado, P.M.; de Assis Leite, D.C.; Rosado, A.S.; Bourne, D.G. Beneficial Microorganisms for Corals (BMC): Proposed mechanisms for coral health and resilience. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Shinde, P.B.; Lee, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. Bile acid derivatives from a sponge-associated bacterium Psychrobacter sp. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2009, 32, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, S.G.; Nielsen, D.A.; Laczka, O.; Shimmon, R.; Beltran, V.H.; Ralph, P.J.; et al. Dimethylsulfoniopropionate, superoxide dismutase and glutathione as stress response indicators in three corals under short-term hyposalinity stress. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2016, 283, 20152418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shore-Maggio, A.; Aeby, G.S.; Callahan, S.M. Influence of salinity and sedimentation on Vibrio infection of the Hawaiian Coral Montipora capitata. Dis Aquat Organ. 2018, 128, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceh, J.; Kilburn, M.R.; Cliff, J.B.; Raina, J-B.B.; Van Keulen, M.; Bourne, D.G. Nutrient cycling in early coral life stages: Pocillopora damicornis larvae provide their algal symbiont (Symbiodinium) with nitrogen acquired from bacterial associates. Ecol Evol. 2013, 3, 2393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oppen, M.J.H.; Blackall, L.L. Coral microbiome dynamics, functions and design in a changing world. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimundo, I.; Silva, R.; Meunier, L.; Valente, S.M.; Lago-Lestón, A.; Keller-Costa, T.; Costa, R. Functional metagenomics reveals differential chitin degradation and utilization features across free-living and host-associated marine microbiomes. Microbiome 2021, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, E.P.; Borges, R.M.; Espinoza, J.L.; Freire, M.; Messias, C.S.M.A.; Villela, H.D.M.; Pereira, L.M.; Vilela, C.L.S.; Rosado, J.G.; Cardoso, P.M.; et al. Coral microbiome manipulation elicits metabolic and genetic restructuring to mitigate heat stress and evade mortality. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabg3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zeng, B.; Liu, D.; Wu, R.; Zhang, J.; Liao, B.; He, H.; Bian, F. Classification and Structural Insight into Vibriolysin-Like Proteases of Vibrio Pathogenicity. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 117, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabbara, S.; Hérivaux, A.; Dugé de Bernonville, T.; Courdavault, V, .; Clastre, M, .; Gastebois., A.; et al. Diversity and evolution of sensor histidine kinases in eukaryotes. Genome Biology Evolut. 2019, 11, 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ip, J.C.; Xie, J.Y.; Yeung, Y.H.; Sun, Y.; Qiu, J.W. Host-symbiont transcriptomic changes during natural bleaching and recovery in the leaf coral Pavona decussata. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 806, 150656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wild, C.; Holger, W.; Huettel, M. Influence of coral mucus on nutrient fluxes in carbonate sands. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2005, 287, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, P.G.; Seymour, J.; Kumbun, K.; Tyson, G.W. Diverse populations of lake water bacteria exhibit chemotaxis towards inorganic nutrients. ISME J. 2013, 7, 1661–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, G.A.; Abd-Elgawad, A.; Abdel-Haleem, A.M.; Siam, R. Egypt's Red Sea coast: phylogenetic analysis of cultured microbial consortia in industrialized sites. Frontiers in Microbiology 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannoni, S.J.; Vergin, K.L. Seasonality in Ocean Microbial Communities. Science 2012, 335, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, K.; Lahti, L.; Gonze, D.; de Vos, W.M.; Raes, J. Metagenomics meets time series analysis: unraveling microbial community dynamics. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2015, 25, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Water parameters | Average in site 1 | Average in site 2 | Average in site 3 | Average in site 4 | Average in site 4 | Average in site 5 | Average in site 6 | Average in site 7 | Average in site 8 | Average in site 9 |

| pH | 8.1 | 8.3 | 8.0 | 7.3 | 8.3 | 8.4 | 7.2 | 8.1 | 8.4 | 8.3 |

| Temperature˚C | 28.7 | 28,4 | 29.7 | 29.3 | 28.0 | 29.8 | 29.4 | 29.5 | 28.8 | 29.6 |

| Turbidity (NTU) | 13 | 14 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 14 | 15 | 14 | 16 |

| DO (mg/l) | 3,36 | 3.54 | 3.31 | 3.44 | 3.72 | 3.46 | 3.33 | 3.34 | 3.52 | 3.50 |

| Salinity ppt | 44.5 | 43.3 | 43,6 | 44.4 | 43.0 | 44.0 | 44.3 | 44.2 | 43.47 | 44.2 |

| Species | Alshreah Far (%) | Alshreah Close (%) | Saweehal Far (%) | Saweehal Close (%) | Marwan Far (%) | Marwan Close (%) | Far-from-Coral (%) | Close-to-Coral (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudoalteromonas agarivorans | 5.99 | 7.35 | 52.28 | 28.77 | 1.75 | 4.94 | 20.00 | 13.6 |

| Vibrio chagasii | 1.35 | 0.31 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 10.98 | 17.2 | 4.12 | 5.87 |

| Vibrio owensii | 12.24 | 1.8 | 1.34 | 1.79 | 4.49 | 2.73 | 6.02 | 2.10 |

| Pseudoalteromonas sp. Xi13 | 2.47 | 2.84 | 4.55 | 11.84 | 0.71 | 1.97 | 2.57 | 5.55 |

| Pseudoalteromonas atlantica | 1.55 | 1.82 | 2.58 | 6.93 | 0.45 | 1.2 | 1.52 | 3.31 |

| Psychrobacter sp. P11G3 | 2.96 | 7.98 | 0.02 | 0 | 1.07 | 0.17 | 1.35 | 2.71 |

| Psychrobacter sp. 28M-43 | 2.72 | 7.86 | 0.02 | 0 | 1.03 | 0.16 | 1.25 | 2.67 |

| Pseudoalteromonas sp. 3J6 | 5.46 | 2.4 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 3.5 | 0.24 | 2.99 | 0.89 |

| Vibrio sp. THAF190c | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 4.63 | 3.45 | 2.59 | 1.19 | 2.41 |

| Vibrio ponticus | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.39 | 5.93 | 2.81 | 2.05 | 1.12 |

| Sample ID | Observed | Chao1 | ACE | Shannon | Simpson | Fisher |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alshreah Far (R1A, R1B, R1C) | 5.99 | 7.35 | 52.28 | 28.77 | 1.75 | 4.94 |

| Alshreah Close (R2A, R2B, R2C) | 5.46 | 2.4 | 2.57 | 5.55 | 2.99 | 0.89 |

| Saweehal Far (S1A, S1B, S1C) | 52.28 | 1.75 | 0.31 | 2.12 | 5.87 | 0.89 |

| Saweehal Close (S2A, S2B, S2C) | 4.94 | 3.31 | 1.52 | 5.55 | 2.77 | 0.88 |

| Marwan Far (M1A, M1B, M1C) | 1.75 | 4.12 | 1.75 | 4.94 | 2.94 | 2 |

| Marwan Close (M2A, M2B, M2C) | 4.94 | 1.75 | 4.94 | 2.1 | 0.95 | 1.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).