Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Wintersweet (Chimonanthus praecox) is known for its flowering in winter and rich floral aroma, and it’s the whole flower is yellow or the inner petals are red. In this study, we choose the wintersweet genotypes HLT040 and HLT015 (belonging to the C. praecox 'Luteus' group and C. praecox 'Grandiflorus' group, respectively) as the re-search materials, and studied the co-regulatory mechanism of color and fragrance of wintersweet through metabolomics and transcriptomics. This study found that there were more flavonoids in HLT015, and anthocyanins (Cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside and Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside) were only present in HLT015, but HLT040 contained more monoterpenes and FVBPs (phenylpropanoid volatile compounds) than HLT015. We constructed putative benzenoids and phenylpropanoid metabolism pathway as well as terpene metabolism pathways. We found some linkages between the different struc-tural genes and metabolites in flower color and fragrance of wintersweet, and screened out 34 TFs that may be related to one or more structural genes in benzenoids and phenylpropanoid or terpene metabolism pathways. This study provided a theo-retical basis for understanding the co-regulatory mechanism of color and fragrance in wintersweet.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

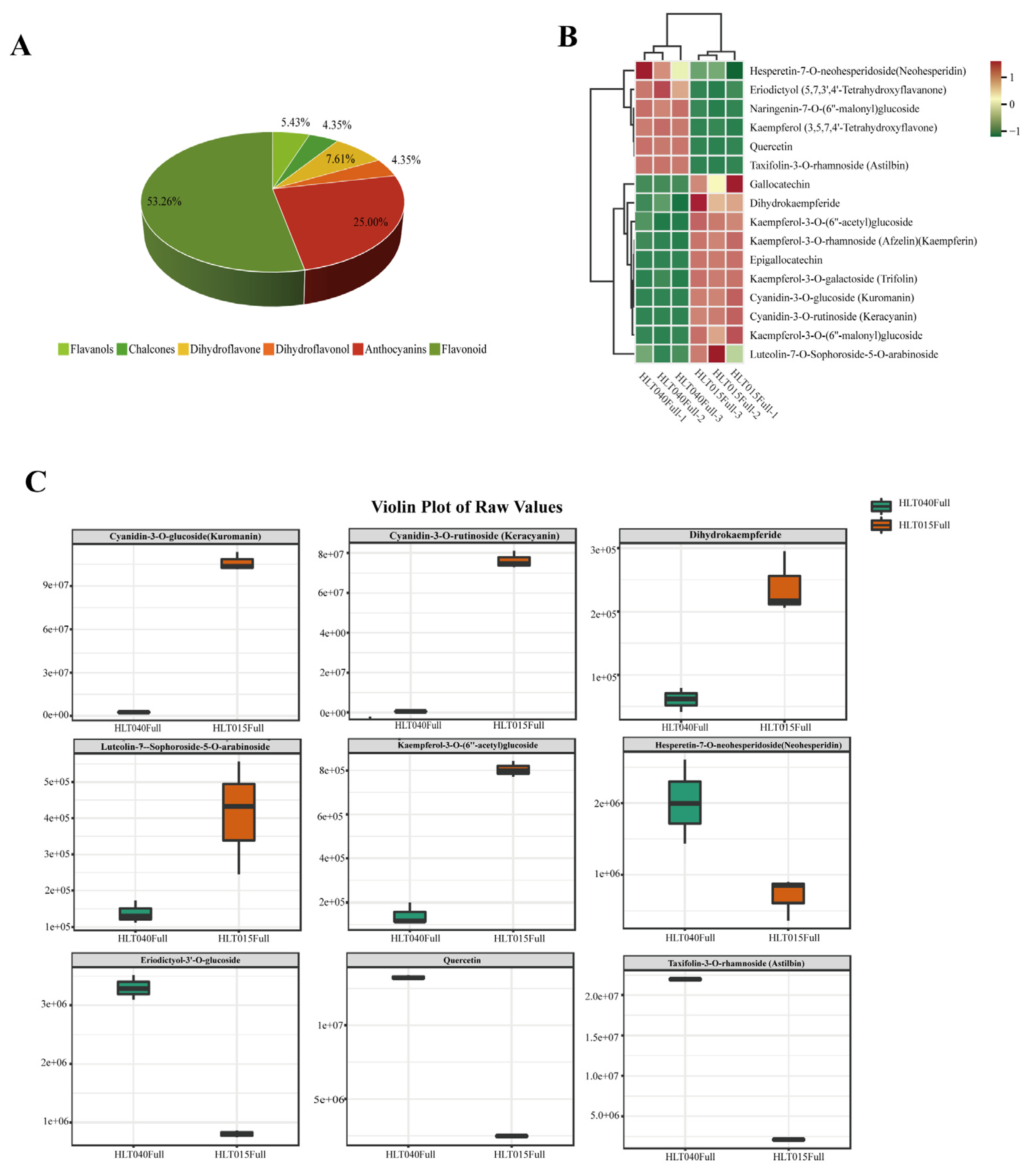

2.1. Identification of Differentially Abundant Flavonoids Between HLT040 and HLT015

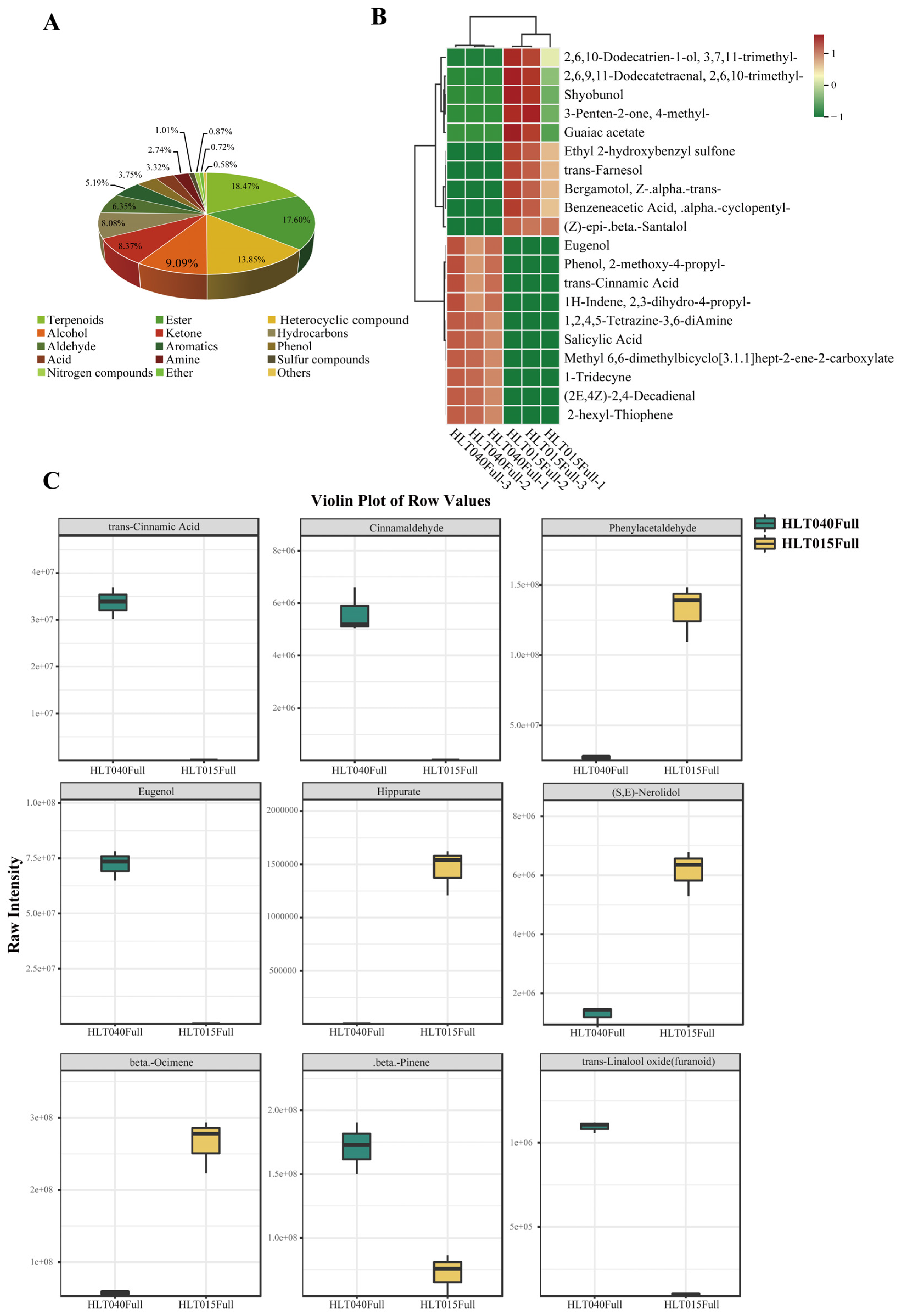

2.2. Identification of Differentially Abundant Volatiles Between HLT040 and HLT015

2.3. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) in HLT040 and HLT015 Flowers

2.4. Correlation Between Pigment and Scent Compounds in Wintersweet

- 1)

- The hypothetical benzenoid and phenylpropanoid metabolism pathway

- 2)

- The hypothetical terpenoid biosynthetic pathway

2.5. Screening of Transcription Factors That Regulate Key Genes Involved in Floral Color and Fragrance

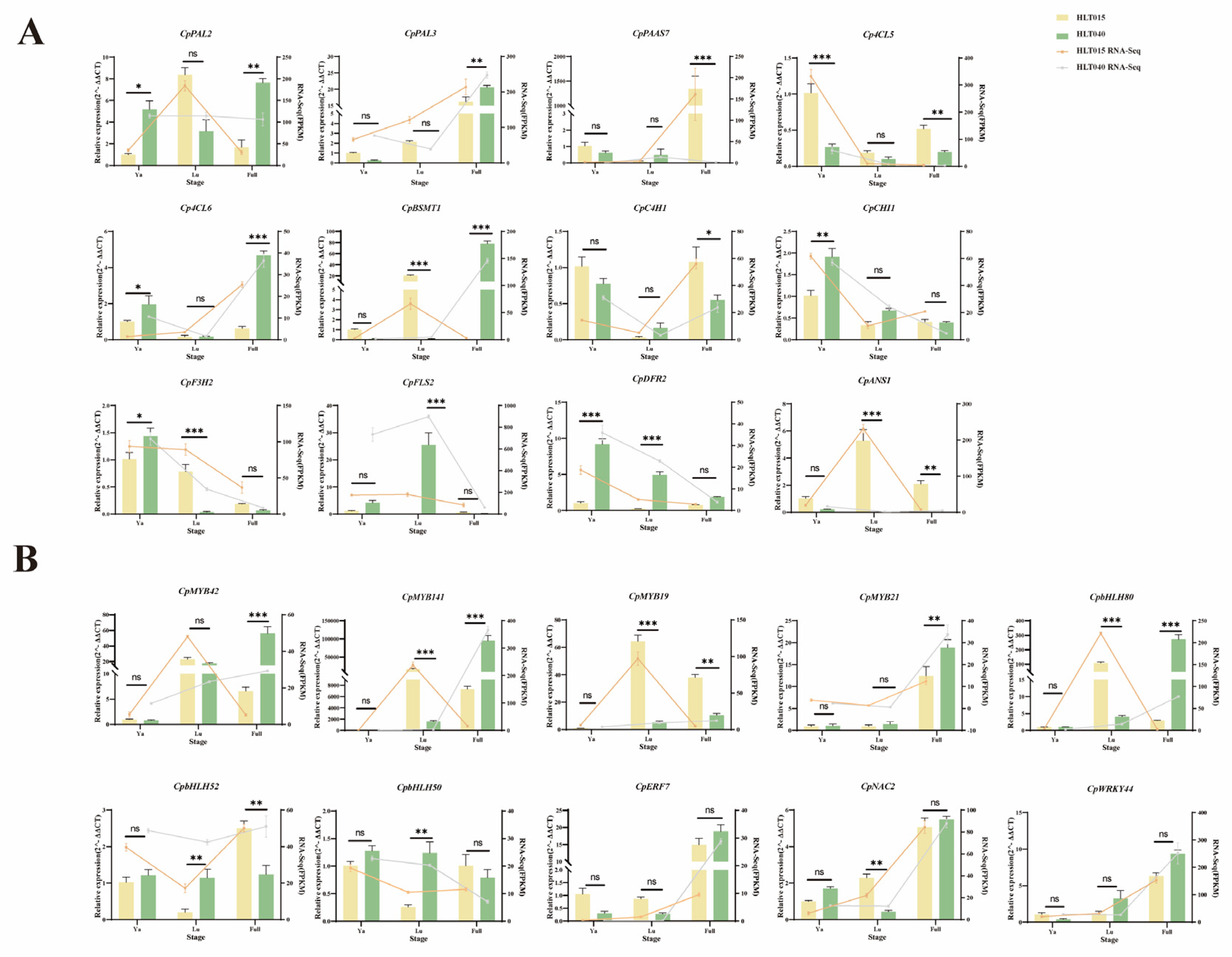

2.6. RT-qPCR Analysis of Key Structural Genes and Candidate TFs

2.7. Verification of TFs Interactions with Flower Scent and Color Promoters

3. Discussion

3.1. Color and Fragrance Metabolites of Wintersweet Flowers

3.2. Hypothetical Color and Fragrance Metabolic Pathways of Wintersweet Flowers

3.3. Co-Regulation of Structural Genes Related to Color and Fragrance Synthesis Based on Transcription Factors in Wintersweet Flowers

4. Materials and Methods

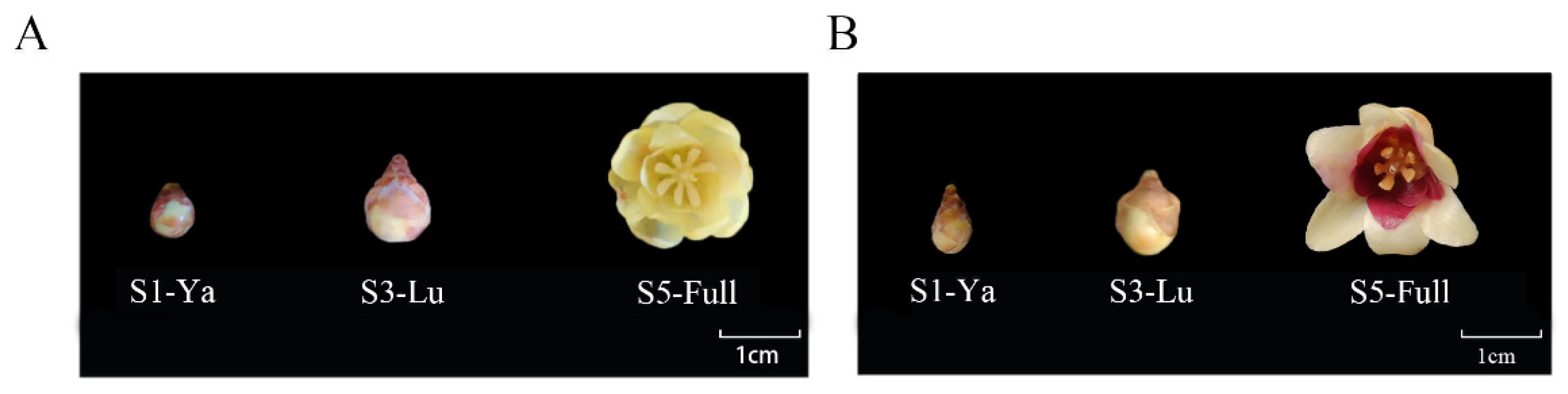

4.1. Plant Materials

4.2. UPLC-MS/MS Analysis

4.3. GC-MS Analysis

4.4. Transcriptome Sequencing and Data Analysis

4.5. Co-Expression Network Analysis of Candidate Transcription Factors with Key Structural Genes

4.6. RT-qPCR Analysis

4.7. Yeast Y1H

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu W., Feng Y., Yu S., Fan Z., Li X., Li J., Yin H. The flavonoid biosynthesis network in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2021, 22(23):12824.

- Zhao X., Ge W., Miao Z. Integrative metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses reveals the accumulation patterns of key metabolites associated with flavonoids and terpenoids of Gynostemma pentaphyllum (Thunb.) Makino. Sci. Rep., 2024, 14(1):8644.

- Li Y., Bao T., Zhang J., Li H., Shan X., Yan H., Kimani S., Zhang L., Gao X. The coordinated interaction or regulation between floral pigments and volatile organic compounds. Horticultural Plant Journal, 2024.

- Pichersky E. Biochemistry and genetics of floral scent: a historical perspective. Plant J., 2023, 115(1):18-36. [CrossRef]

- Yang N., Zhao K., Li X., Zhao R., Z Aslam M., Yu L., Chen L. Comprehensive analysis of wintersweet flower reveals key structural genes involved in flavonoid biosynthetic pathway. Gene, 2018, 676:279-289.

- Zhou M., Xiang L., Chen L. Preliminary studies on the components of volatile floral flavor and flower pigments of Chimonanthus praecox L. Journal of Beijing Forestry University, 2007(S1):22-25.

- Li Z., Jiang Y., Liu D., Ma J., Li J., Li M., Sui S. Floral scent emission from nectaries in the adaxial side of the innermost and middle petals in Chimonanthus praecox. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2018, 19(10):3278.

- Feng N. Determination of Floral Volatile Components And Prelimin ary Study On Function of Two Terpene Synthases In Wintersweet. Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China. 2017.

- Zhou J.-R., Ni D.-J. Changes in flower aroma compounds of cultivars of Chimonanthus praecox (L.) Link and at different stages relative to chimonanthus tea quality. Acta Horticulturae Sinica, 2010, 37(10):1621.

- Yu L. The Study of Violate Compounds and Flower Pigment in Chimonanthus praecox L. Huazhong Agricultural University Wuhan, China, 2013.

- Tian J. Analysis of Floral Volatile Biosynthetic Pathways and Functional Characterization of Mono-TPSs Genes from Chimonanthus praecox. 2019.

- Shen Z., Li W., Li Y., Liu M., Cao H., Provart N., Ding X., Sun M., Tang Z., Yue C. The red flower wintersweet genome provides insights into the evolution of magnoliids and the molecular mechanism for tepal color development. The Plant Journal, 2021, 108(6):1662-1678.

- Jiang Y., Chen F., Song A., Zhao Y., Chen X., Gao Y., Wei G., Zhang W., Guan Y., Fu J. The genome assembly of Chimonanthus praecox var. concolor and comparative genomic analysis highlight the genetic basis underlying conserved and variable floral traits of wintersweet. Industrial Crops Products, 2023, 206:117603.

- Shang J., Tian J., Cheng H., Yan Q., Li L., Jamal A., Xu Z., Xiang L., Saski C. A., Jin S., Zhao K., Liu X., Chen L. The chromosome-level wintersweet (Chimonanthus praecox) genome provides insights into floral scent biosynthesis and flowering in winter. Genome biology, 2020, 21(1):1-28.

- Yang N. Functional Characterization of Anthocyanin Synthase CpANS1 and Transcription Factor CpMYB2 in Chimonanthus praecox Tepals. Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China. 2019.

- Zhao R., Song X., Yang N., Chen L., Xiang L., Liu X.-Q., Zhao K. Expression of the subgroup IIIf bHLH transcription factor CpbHLH1 from Chimonanthus praecox (L.) in transgenic model plants inhibits anthocyanin accumulation. Plant cell reports, 2020, 39:891-907.

- Xiang L., Zhao K., Chen L. Molecular cloning and expression of Chimonanthus praecox farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase gene and its possible involvement in the biosynthesis of floral volatile sesquiterpenoids. Plant Physiology Biochemistry, 2010, 48(10-11):845-850.

- Kamran H. M., Hussain S. B., Junzhong S., Xiang L., Chen L.-Q. Identification and molecular characterization of geranyl diphosphate synthase (GPPS) genes in wintersweet flower. Plants, 2020, 9(5):666. [CrossRef]

- Pang H., Xiang L., Zhao K., Li X., Yang N., Cheng L. Genetic transformation and functional characterization of Chimonanthus praecox SAMT gene in tobacco. Journal of Beijing Forestry University, 2014, 36:117-122.

- Tian J., Ma Z., Zhao K., Zhang J., Xiang L., Chen L. Transcriptomic and proteomic approaches to explore the differences in monoterpene and benzenoid biosynthesis between scented and unscented genotypes of wintersweet. Physiologia plantarum, 2019, 166(2):478-493.

- Yeon J. Y., Kim W. S. Biosynthetic linkage between the color and scent of flowers: A review. Horticultural Science Technology, 2021, 39(6):697-713.

- Shen Y., Rao Y., Ma M., Li Y., He Y., Wang Z., Liang M., Ning G. Coordination among flower pigments, scents and pollinators in ornamental plants. Horticulture Advances, 2024, 2(1):6.

- Kiani H. S., Noudehi M. S., Shokrpour M., Zargar M., Naghavi M. R. Investigation of genes involved in scent and color production in Rosa damascena Mill. Scientific Reports, 2024, 14(1):20576. [CrossRef]

- Cna'ani A., Spitzer-Rimon B., Ravid J., Farhi M., Masci T., Aravena-Calvo J., Ovadis M., Vainstein A. Two showy traits, scent emission and pigmentation, are finely coregulated by the MYB transcription factor PH4 in petunia flowers. New Phytologist, 2015, 208(3):708-714.

- Aslam M. Z., Lin X., Li X., Yang N., Chen L. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of CpMYC2 and CpBHLH13 transcription factors from wintersweet (Chimonanthus praecox L.). Plants, 2020, 9(6):785.

- Ninkuu V., Zhang L., Yan J., Fu Z., Yang T., Zeng H. Biochemistry of terpenes and recent advances in plant protection. Int J Mol Sci., 2021, 22(11):5710.

- Rosenkranz M., Chen Y., Zhu P., Vlot A. C. Volatile terpenes–mediators of plant-to-plant communication. plant J., 2021, 108(3):617-631.

- Delle-Vedove R., Juillet N., Bessière J.-M., Grison C., Barthes N., Pailler T., Dormont L., Schatz B. Colour-scent associations in a tropical orchid: Three colours but two odours. Phytochemistry, 2011, 72(8):735-742. [CrossRef]

- Dormont L., Delle-Vedove R., Bessière J.-M., Schatz B. Floral scent emitted by white and coloured morphs in orchids. Phytochemistry, 2014, 100:51-59. [CrossRef]

- Yeon J. Y., Kim W. S. Floral pigment-scent associations in eight cut rose cultivars with various petal colors. Horticulture, Environment, Biotechnology, 2020, 61:633-641.

- Shaipulah N. F. M., Muhlemann J. K., Woodworth B. D., Van Moerkercke A., Verdonk J. C., Ramirez A. A., Haring M. A., Dudareva N., Schuurink R. C. CCoAOMT down-regulation activates anthocyanin biosynthesis in petunia. Plant physiology, 2016, 170(2):717-731. [CrossRef]

- Sheehan H., Hermann K., Kuhlemeier C. Color and scent: how single genes influence pollinator attraction. Cold Spring Harbor symposia on quantitative biology. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 2012, 77:117-133. [CrossRef]

- Yu-Xuan G., Liang-Sheng W., Yan-Jun X., Zheng-An L., Chong-Hui L., Ni A. J. Flower Color, Pigment Composition and Their Changes During Flowering in Chimonanthus praecox Link. Acta Horticulturae Sinica, 2008, 35(9):1331-1338.

- Iwashina T., Konta F., Kitajima J. Anthocyanins and flavonols of Chimonanthus praecox (Calycanthaceae) as flower pigments. Journal of Japanese Botany, 2001, 76(3):166-172.

- Zhao H., Masood H. A., Muhammad S. Unveiling the aesthetic secrets: exploring connections between genetic makeup, chemical, and environmental factors for enhancing/improving the color and fragrance/aroma of Chimonanthus praecox. PeerJ, 2024, 12:e17238.

- Pichersky E., Raguso R. A. Why do plants produce so many terpenoid compounds? New Phytologist, 2018, 220(3):692-702.

- Meng L., Shi R., Wang Q., Wang S. Analysis of floral fragrance compounds of Chimonanthus praecox with different floral colors in Yunnan, China. Separations, 2021, 8(8):122.

- Qian X., Chen L., Li B., Shi R. Analysis of Aromatic Components from Different Genotypes of Chimonanthus praecox in Yunnan Province. Southwest China Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 2021, 34(4).

- Kreis P., Dietrich A., Mosandl A. Elution order of the furanoid linalool oxides on common gas chromatographic phases and modified cyclodextrin phases. Journal of Essential Oil Research, 1996, 8(4):339-341. [CrossRef]

- Winterhalter P., Katzenberger D., Schreier P. 6, 7-Epoxy-linalool and related oxygenated terpenoids from Carica papaya fruit. Phytochemistry, 1986, 25(6):1347-1350. [CrossRef]

- Luan F., Mosandl A., Gubesch M., Wüst M. Enantioselective analysis of monoterpenes in different grape varieties during berry ripening using stir bar sorptive extraction-and solid phase extraction-enantioselective-multidimensional gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A, 2006, 1112(1-2):369-374.

- Luan F., Mosandl A., Degenhardt A., Gubesch M., Wüst M. Metabolism of linalool and substrate analogs in grape berry mesocarp of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Morio Muscat: demonstration of stereoselective oxygenation and glycosylation. Anal. Chim. Acta, 2006, 563(1-2):353-364. [CrossRef]

- Zvi M. M. B., Negre-Zakharov F., Masci T., Ovadis M., Shklarman E., Ben-Meir H., Tzfira T., Dudareva N., Vainstein A. Interlinking showy traits: co-engineering of scent and colour biosynthesis in flowers. Plant biotechnology journal, 2008, 6(4):403-415. [CrossRef]

- Sinopoli A., Calogero G., Bartolotta A. Computational aspects of anthocyanidins and anthocyanins: A review. Food chemistry, 2019, 297:124898. [CrossRef]

- Dudareva N., Pichersky E. Biochemical and molecular genetic aspects of floral scents. Plant physiology, 2000, 122(3):627-634. [CrossRef]

- Vranová E., Coman D., Gruissem W. Network analysis of the MVA and MEP pathways for isoprenoid synthesis. Annual review of plant biology, 2013, 64:665-700. [CrossRef]

- Karunanithi P. S., Zerbe P. Terpene synthases as metabolic gatekeepers in the evolution of plant terpenoid chemical diversity. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2019, 10:1166. [CrossRef]

- Tian F., Yang D.-C., Meng Y.-Q., Jin J., Gao G. PlantRegMap: charting functional regulatory maps in plants. Nucleic acids research, 2020, 48(D1):D1104-D1113.

- Fang X., Zhang L., Wang L. The transcription factor MdERF78 is involved in ALA-induced anthocyanin accumulation in apples. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2022, 13:915197.

- Wu T., Liu H.-T., Zhao G.-P., Song J.-X., Wang X.-L., Yang C.-Q., Zhai R., Wang Z.-G., Ma F.-W., Xu L.-F. Jasmonate and ethylene-regulated ethylene response factor 22 promotes lanolin-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in ‘Zaosu’pear (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd.) fruit. Biomolecules, 2020, 10(2):278.

- Yang Z., Jin W., Luo Q., Li X., Wei Y., Lin Y. FhMYB108 Regulates the Expression of Linalool Synthase Gene in Freesia hybrida and Arabidopsis. Biology (Basel), 2024.

- Shen S., Yin M., Zhou Y., Huan C., Zheng X., Chen K. The role of CitMYC3 in regulation of valencene synthesis-related CsTPS1 and CitAP2. 10 in Newhall Sweet Orange. Scientia Horticulturae, 2024, 334:113338.

- Guo Y., Guo Z., Zhong J., Liang Y., Feng Y., Zhang P., Zhang Q., Sun M. Positive regulatory role of R2R3 MYBs in terpene biosynthesis in Lilium ‘Siberia’. Horticultural Plant Journal, 2023, 9(5):1024-1038.

- Kamran H. M., Fu X., Wang H., Yang N., Chen L. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the bHLH transcription factor family in wintersweet (Chimonanthus praecox). International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023, 24(17):13462.

- Verdonk J. C., Haring M. A., Van Tunen A. J., Schuurink R. C. ODORANT1 regulates fragrance biosynthesis in petunia flowers. The Plant Cell, 2005, 17(5):1612-1624. [CrossRef]

- Stracke R., Ishihara H., Huep G., Barsch A., Mehrtens F., Niehaus K., Weisshaar B. Differential regulation of closely related R2R3-MYB transcription factors controls flavonol accumulation in different parts of the Arabidopsis thaliana seedling. The Plant Journal, 2007, 50(4):660-677. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez A., Zhao M., Leavitt J. M., Lloyd A. M. Regulation of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway by the TTG1/bHLH/Myb transcriptional complex in Arabidopsis seedlings. The Plant Journal, 2008, 53(5):814-827.

- Colquhoun T. A., Kim J. Y., Wedde A. E., Levin L. A., Schmitt K. C., Schuurink R. C., Clark D. G. PhMYB4 fine-tunes the floral volatile signature of Petunia× hybrida through PhC4H. Journal of experimental botany, 2011, 62(3):1133-1143. [CrossRef]

- Spitzer-Rimon B., Farhi M., Albo B., Cna’ani A., Ben Zvi M. M., Masci T., Edelbaum O., Yu Y., Shklarman E., Ovadis M. The R2R3-MYB–like regulatory factor EOBI, acting downstream of EOBII, regulates scent production by activating ODO1 and structural scent-related genes in petunia. The Plant Cell, 2012, 24(12):5089-5105.

- Yang Z., Li Y., Gao F., Jin W., Li S., Kimani S., Yang S., Bao T., Gao X., Wang L. MYB21 interacts with MYC2 to control the expression of terpene synthase genes in flowers of Freesia hybrida and Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2020, 71(14):4140-4158.

- Wei Y., Meng N., Wang Y., Cheng J., Duan C., Pan Q. Transcription factor VvWRKY70 inhibits both norisoprenoid and flavonol biosynthesis in grape. Plant Physiology, 2023, 193(3):2055-2070.

- Wang L., Wang Q., Fu N., Song M., Han X., Yang Q., Zhang Y., Tong Z., Zhang J. Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside contributes to leaf color change by regulating two bHLH transcription factors in Phoebe bournei. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023, 24(4):3829.

- Zeng H., Chen M., Zheng T., Tang Q., Xu H. Metabolomics Analysis Reveals the Accumulation Patterns of Flavonoids and Volatile Compounds in Camellia oleifera Petals with Different Color. Molecules, 2023, 28(21):7248.

- Ye S., Feng L., Zhang S., Lu Y., Xiang G., Nian B., Wang Q., Zhang S., Song W., Yang L. Integrated metabolomic and transcriptomic analysis and identification of dammarenediol-II synthase involved in saponin biosynthesis in Gynostemma longipes. Front. Plant. Sci., 2022, 13:852377.

- Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N. S., Wang J. T., Ramage D., Amin N., Schwikowski B., Ideker T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome research, 2003, 13(11):2498-2504. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, Zhao W, Fu X. Guo C, Huang S, Chen L, Yang N. Screening and Verification of Reference Genes of Winter Sweet (Chimonanthus praecox L.) in Real-time Quantitative PCR Analysis. Molecular Plant Breeding, 2022, 1-14.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).