Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

02 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Prenatal stress has been reported to harm the physiological and biochemical functions of the brain of the offspring, potentially resulting in anxiety- and depression-like behaviors later in life. Trans- Resveratrol (RESV) is known for its anti-inflammatory, anxiolytic, and antidepressant properties. However, whether administering RESV during pregnancy can counteract the anxiety- and de-pression like behaviors induced by maternal stress is unknown. This study aimed to assess the protective potential of RESV against molecular and behavioral changes induced by prenatal stress. During pregnancy, the dams received 50 mg/kg BW/day of RESV orally. They underwent a movement restriction for forty-five minutes, three times a day, in addition to being exposed to artificial light 24 hours before delivery. The male offspring were left undisturbed until early adulthood, at which point they underwent behavioral assessments, including the open field test, elevated plus maze, and forced swim test. Subsequently, they were euthanized, and the hippo-campus and prefrontal cortex were extracted for RT-qPCR analysis to measure Bdnf mRNA ex-pression. By weaning, results showed that prenatal stress led to reduced weight gain and, in adulthood, increased anxiety- and depression-like behaviors and changes in Bdnf mRNA expres-sion. However, these effects were attenuated by maternal RESV supplementation. The findings suggest that RESV can prevent anxiety- and depression-like behaviors induced by prenatal stress by modulating Bdnf mRNA expression.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

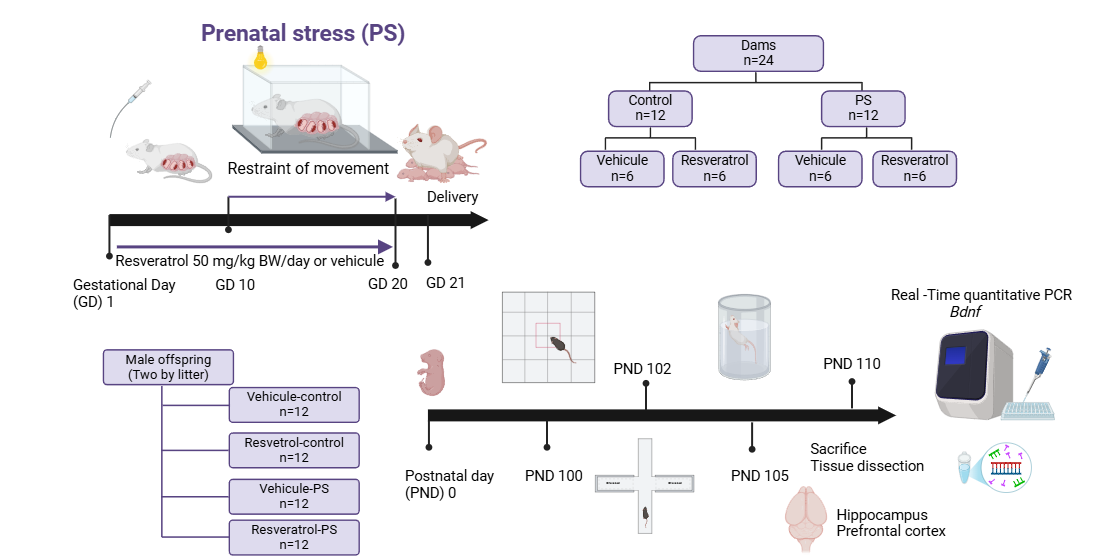

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Drugs

2.2. Animals

2.3. Experimental Groups

2.4. Model of Restraint of Movement

2.5. Open Field Test

2.6. Elevate Plus Maze

2.7. Forced Swimming Test

2.8. Tissue Preparation

2.9. RNA Isolation

2.10. Real Time Quantitative PCR

2.11. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Litter Size and Body Weight of Pups

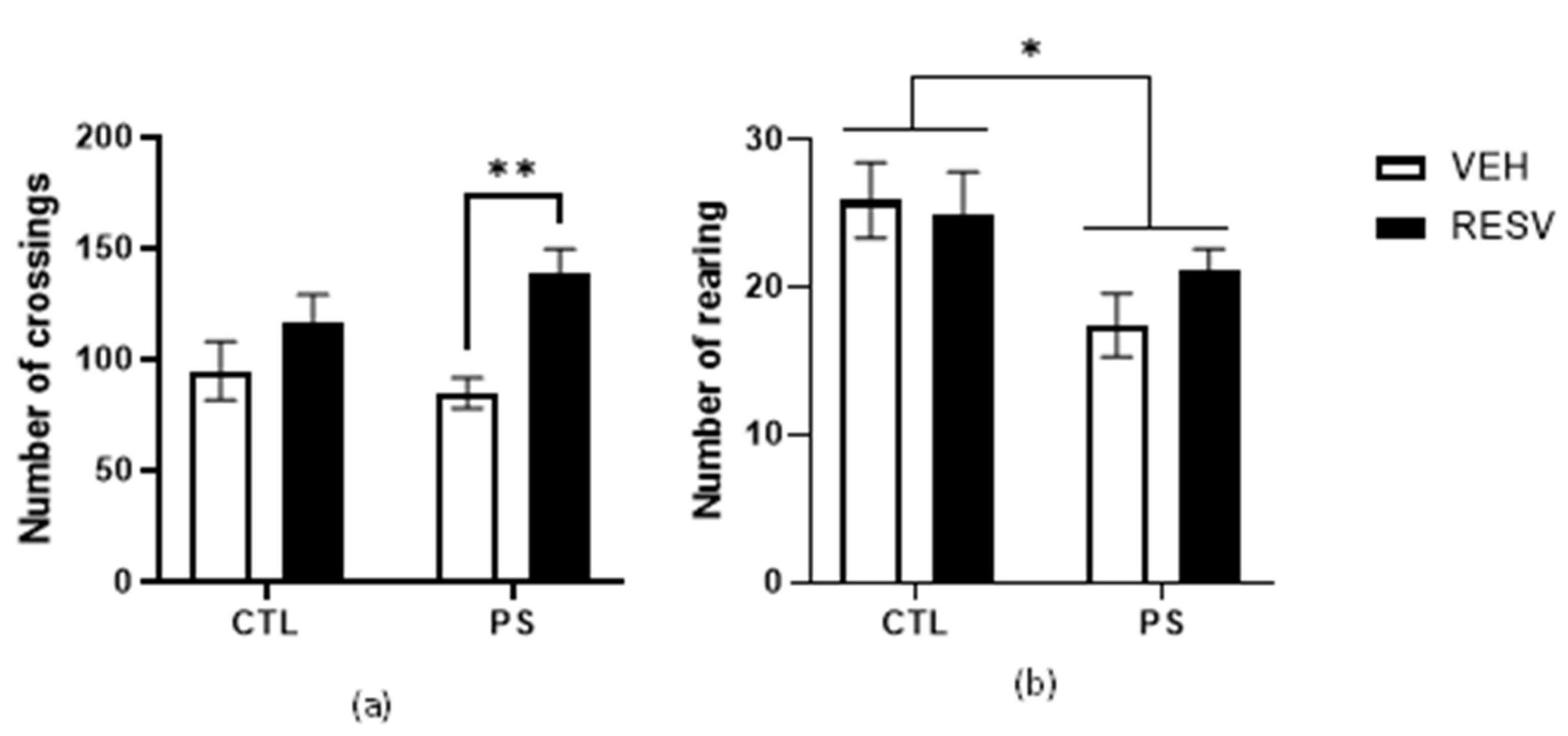

3.2. Open Field Activity

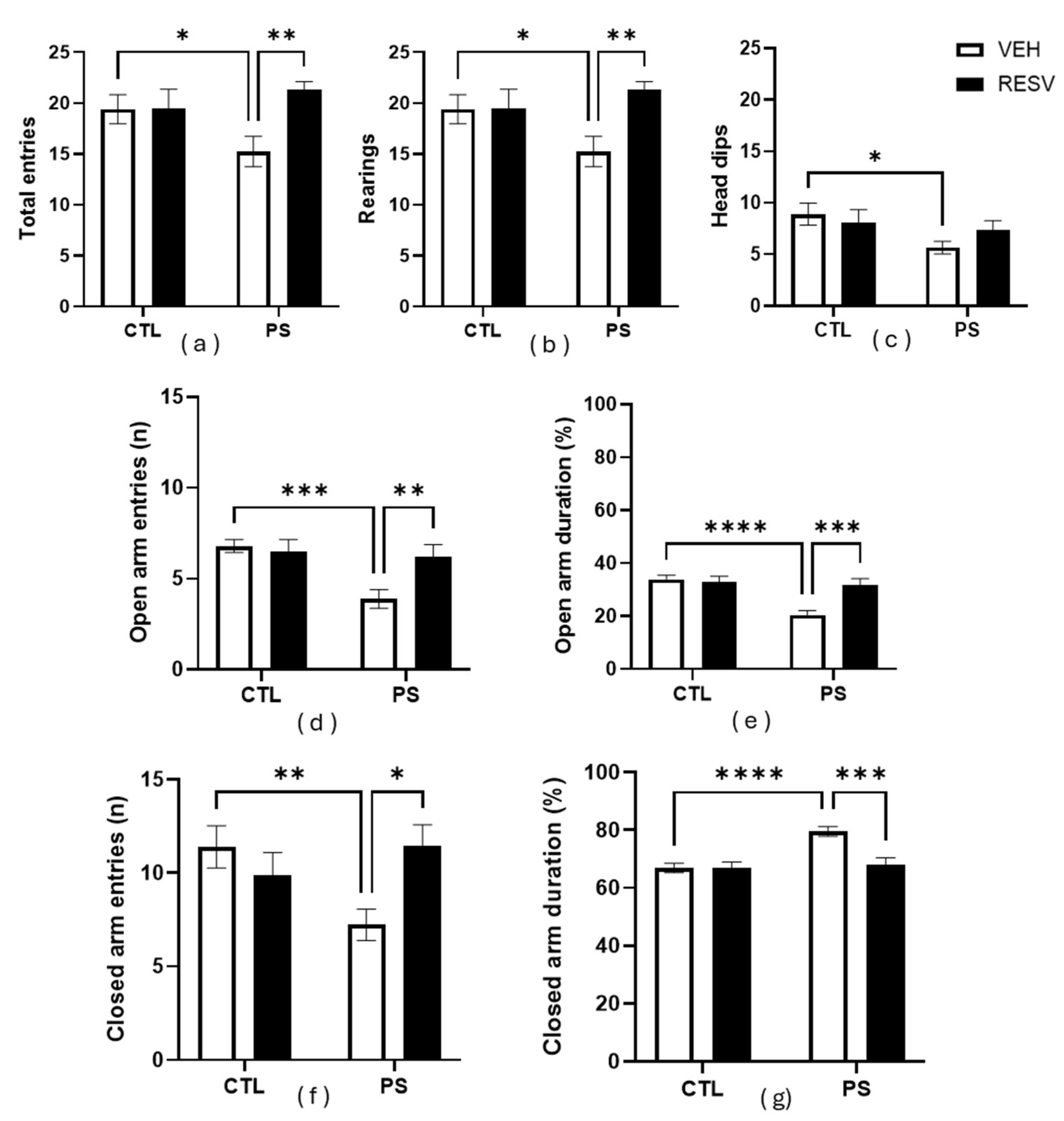

3.3. Elevated plus maze

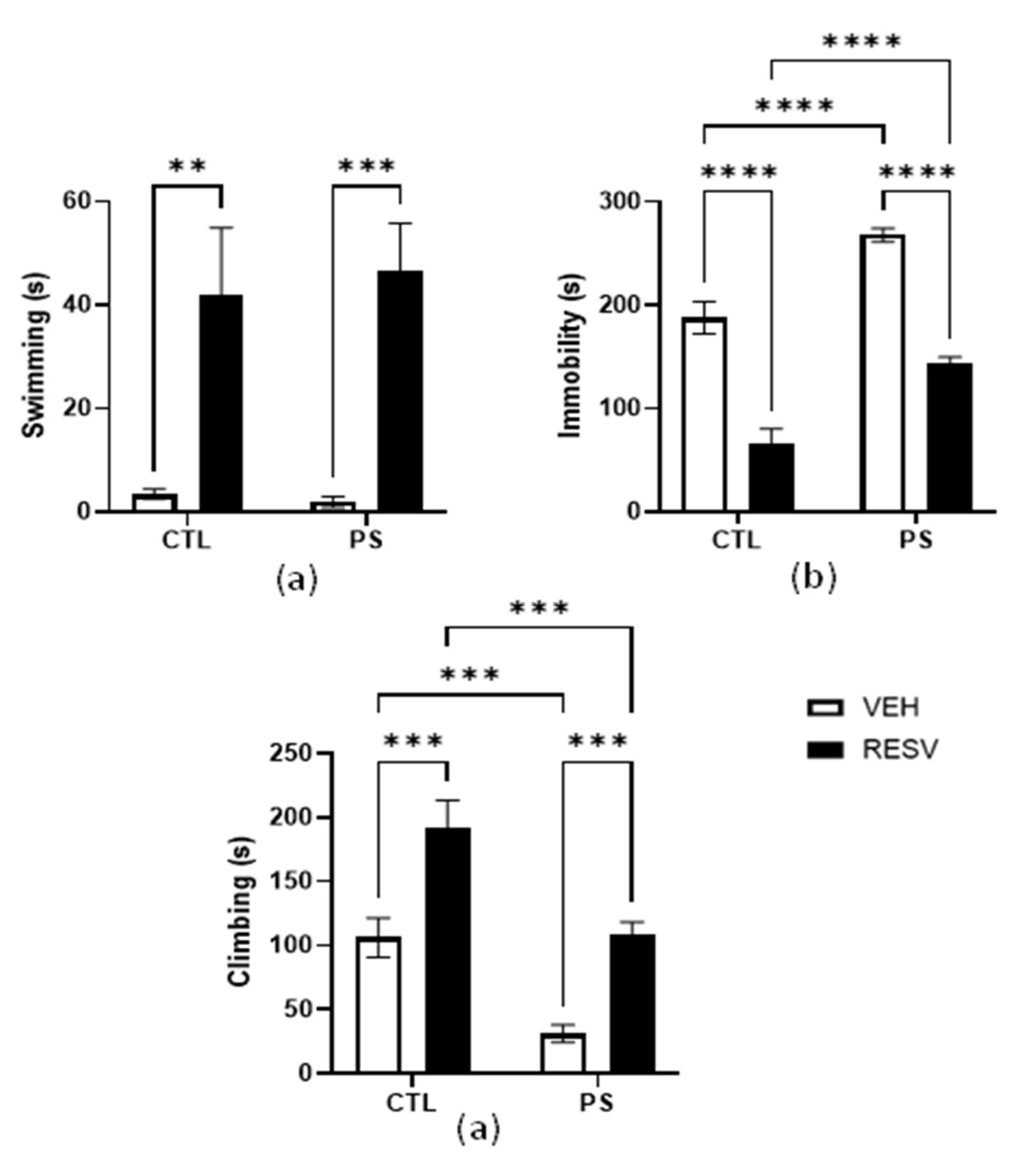

3.4. Forced Swimming Test

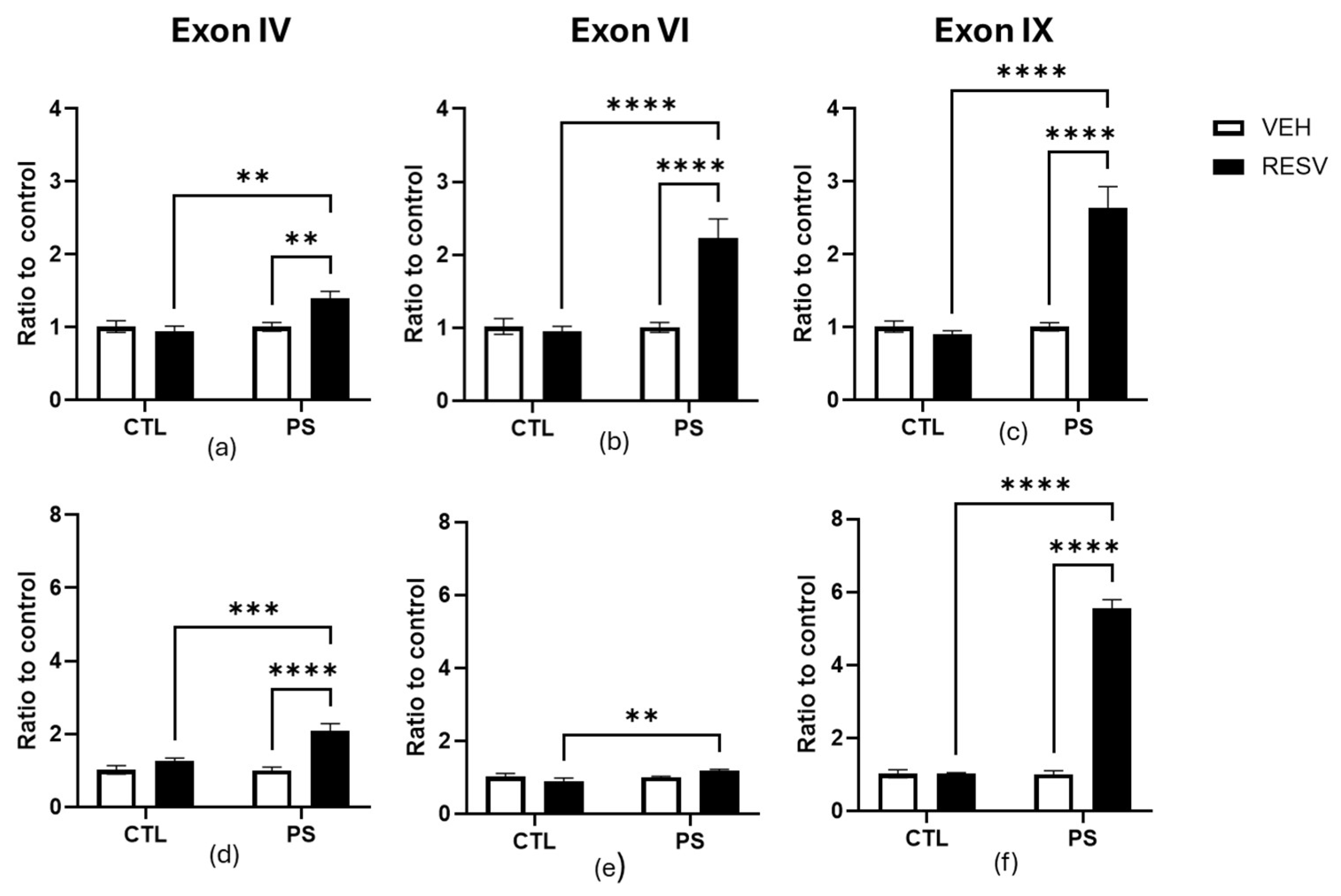

3.5. Gene Expression of Bdnf

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barker, D.J. A new model for the origins of chronic disease. Med. Health Care Philos. 2001, 4, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.L.; Mileva, G.; Huta, V.; Bielajew, C. In utero programming alters adult response to chronic mild stress: part 3 of a longitudinal study. Brain Res. 2014, 1588, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bergh, B.R.H.; van den Heuvel, M.I.; Lahti, M.; Braeken, M.; de Rooij, S.R.; Entringer, S.; Hoyer, D.; Roseboom, T.; Räikkönen, K.; King, S.; et al. Prenatal developmental origins of behavior and mental health: The influence of maternal stress in pregnancy. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 117, 26–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krontira, A.C.; Cruceanu, C.; Binder, E.B. Glucocorticoids as Mediators of Adverse Outcomes of Prenatal Stress. Trends Neurosci. 2020, 43, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, S.U.; Bhat, U.A.; Kumar, A. Prenatal stress effects on offspring brain and behavior: Mediators, alterations and dysregulated epigenetic mechanisms. J. Biosci. 2021, 46, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, V.X.; Patel, S.; Jones, H.F.; Dale, R.C. Maternal immune activation and neuroinflammation in human neurodevelopmental disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 564–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazzari, S.; Frigerio, A. The programming role of maternal antenatal inflammation on infants' early neurodevelopment: A review of human studies: Special Section on "Translational and Neuroscience Studies in Affective Disorders" Section Editor, Maria Nobile MD, PhD. J. Affect Disord. 2020, 263, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.R.; Bale, T.L.; Epperson, C.N. Prenatal programming of mental illness: current understanding of relationship and mechanisms. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2015, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badihian, N.; Daniali, S.S.; Kelishadi, R. Transcriptional and epigenetic changes of brain derived neurotrophic factor following prenatal stress: A systematic review of animal studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 117, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowiański, P.; Lietzau, G.; Czuba, E.; Waśkow, M.; Steliga, A.; Moryś, J. BDNF: A Key Factor with Multipotent Impact on Brain Signaling and Synaptic Plasticity. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 38, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Z. The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaratnasingam, S.; Janca, A. Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor: a novel neurotrophin involved in psychiatric and neurological disorders. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 134, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, M.; Morici, J.F.; Zanoni, M.B.; Bekinschtein, P. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor: A Key Molecule for Memory in the Healthy and the Pathological Brain. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2019, 13, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhan, M.; Rizvi, A. The Pharmacological Properties of Red Grape Polyphenol Resveratrol: Clinical Trials and Obstacles in Drug Development. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, Z.; Mazhar, A.; Batool, S.A.; Akram, N.; Hassan, M.; Khan, M.U.; Afzaal, M.; Hassan, U.U.; Shah, Y.A.; Desta, D.T. Exploring the multimodal health-promoting properties of resveratrol: A comprehensive review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 2240–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, A.; Beidler, J.; Hong, M.Y. Resveratrol and Depression in Animal Models: A Systematic Review of the Biological Mechanisms. Molecules 2018, 23, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayganfard, M. Molecular and biological functions of resveratrol in psychiatric disorders: a review of recent evidence. Cell Biosci. 2020, 10, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.M.; Zhang, Y.M.; Feng, Y.Z.; Zhang, K.X.; Zhang, J.Y.; Chen, J.; Luo, B.L.; Li, X.Y.; Chen, G.H. Resveratrol ameliorates maternal separation-induced anxiety- and depression-like behaviors and reduces Sirt1-NF-kB signaling-mediated neuroinflammation. Front Behav. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1172091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, P.; Andero, R.; Armario, A. Restraint or immobilization: A comparison of methodologies for restricting free movement in rodents and their potential impact on physiology and behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 151, 105224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstock, M. Alterations induced by gestational stress in brain morphology and behaviour of the offspring. Prog. Neurobiol. 2001, 65, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibenhener, M.L.; Wooten, M.C. Use of the Open Field Maze to measure locomotor and anxiety-like behavior in mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2015, 96, e52434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraeuter, A.K.; Guest, P.C.; Sarnyai, Z. The Open Field Test for Measuring Locomotor Activity and Anxiety-Like Behavior. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1916, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellow, S.; Chopin, P.; File, S.E.; Briley, M. Validation of open: closed arm entries in an elevated plus-maze as a measure of anxiety in the rat. J. Neurosci. Methods. 1985, 14, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsolt, R.D.; Le Pichon, M.; Jalfre, M. Depression: a new animal model sensitive to antidepressant treatments. Nature 1977, 266, 730–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, D.J. The developmental origins of chronic adult disease. Acta Paediatr. Suppl. 2004, 93, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, D.J.; Osmond, C.; Rodin, I.; Fall, C.H.; Winter, P.D. Low weight gain in infancy and suicide in adult life. B.M.J. 1995, 311, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccari, S.; Morley-Fletcher, S. Effects of prenatal restraint stress on the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis and related behavioural and neurobiological alterations. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2007, 32 (Suppl 1), S10–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.; Chebli, M.; Rees, S.; Lemarec, N.; Godbout, R.; Bielajew, C. Effects of gestational stress: 1. Evaluation of maternal and juvenile offspring behavior. Brain Res. 2008, 1213, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.; Rees, S.; Chebli, M.; Lemarec, N.; Godbout, R.; Huta, V.; Bielajew, C. Effects of gestational stress: 2. Evaluation of male and female adult offspring. Brain Res. 2009, 1302, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaides, N.C.; Kanaka-Gantenbein, C.; Pervanidou, P. Developmental Neuroendocrinology of Early-Life Stress: Impact on Child Development and Behavior. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2024, 22, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anifantaki, F.; Pervanidou, P.; Lambrinoudaki, I.; Panoulis, K.; Vlahos, N.; Eleftheriades, M. Maternal Prenatal Stress, Thyroid Function and Neurodevelopment of the Offspring: A Mini Review of the Literature. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 692446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baier, C.J.; Katunar, M.R.; Adrover, E.; Pallarés, M.E.; Antonelli, M.C. Gestational restraint stress and the developing dopaminergic system: an overview. Neurotox. Res. 2012, 22, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Guan, L.; Zhu, Z.; Li, H. Reduced levels of NR1 and NR2A with depression-like behavior in different brain regions in prenatally stressed juvenile offspring. PLoS One 2013, 8, e81775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstock, M. Prenatal stressors in rodents: Effects on behavior. Neurobiol. Stress. 2016, 6, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Ma, Y.; Chen, J.; Yao, D.; Feng, C.; Dong, Y.; Ren, Y.; Ma, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, G.; et al. Effects of RhoA on depression-like behavior in prenatally stressed offspring rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2022, 432, 113973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zohar, I.; Shoham, S.; Weinstock, M. Perinatal citalopram does not prevent the effect of prenatal stress on anxiety, depressive-like behaviour and serotonergic transmission in adult rat offspring. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2016, 43, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oosterhof, C.A.; El Mansari, M.; Merali, Z.; Blier, P. Altered monoamine system activities after prenatal and adult stress: A role for stress resilience? Brain Res. 2016, 1642, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshan-Milani, S.; Seyyedabadi, B.; Saboory, E.; Parsamanesh, N.; Mehranfard, N. Prenatal stress and increased susceptibility to anxiety-like behaviors: role of neuroinflammation and balance between GABAergic and glutamatergic transmission. Stress 2021, 24, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci-D'Amato, L.; Speranza, L.; Volpicelli, F. Neurotrophic Factor BDNF, Physiological Functions and Therapeutic Potential in Depression, Neurodegeneration and Brain Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naert, G.; Ixart, G.; Maurice, T.; Tapia-Arancibia, L.; Givalois, L. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis adaptation processes in a depressive-like state induced by chronic restraint stress. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2011, 46, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Lu, B. Diverse Functions of Multiple Bdnf Transcripts Driven by Distinct Bdnf Promoters. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, G.J.; Lee, R.S.; Cordner, Z.A.; Ewald, E.R.; Purcell, R.H.; Moghadam, A.A.; Tamashiro, K.L. Prenatal stress decreases Bdnf expression and increases methylation of Bdnf exon IV in rats. Epigenetics 2014, 9, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakata, K.; Jin, L.; Jha, S. Lack of promoter IV-driven BDNF transcription results in depression-like behavior. Genes Brain Behav. 2010, 9, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, K.; Mastin, J.R.; Duke, S.M.; Vail, M.G.; Overacre, A.E.; Dong, B.E.; Jha, S. Effects of antidepressant treatment on mice lacking brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression through promoter IV. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2013, 37, 1863–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, A.; Beidler, J.; Hong, M.Y. Resveratrol and Depression in Animal Models: A Systematic Review of the Biological Mechanisms. Molecules 2018, 23, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhong, H.; Wang, L.; Zhao, J.; Yang, L.; Fan, X. Resveratrol ameliorates estrogen deficiency-induced depression- and anxiety-like behaviors and hippocampal inflammation in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2019, 236, 1385–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.; Chu, L.; Han, Y. Therapeutic effect of resveratrol on mice with depression. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 17, 3061–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahvar, M.; Nikseresht, M.; Shafiee, S.M.; Naghibalhossaini, F.; Rasti, M.; Panjehshahin, M.R.; Owji, A.A. Effect of oral resveratrol on the BDNF gene expression in the hippocampus of the rat brain. Neurochem. Res. 2011, 36, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shojaei, S.; Panjehshahin, M.R.; Shafiee, S.M.; Khoshdel, Z.; Borji, M.; Ghasempour, G.; Owji, A.A. Differential Effects of Resveratrol on the Expression of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Transcripts and Protein in the Hippocampus of Rat Brain. Iran J. Med. Sci. 2017, 42, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

| Gene name | Primer forward (5’ to 3’) | Primer reverse (5’ to 3’) |

|---|---|---|

| Bdnf exon IV | TGGTGGCCGATATGTACTCC | ACTGAAGGCGTGCGAGTATT |

| Bdnf exon VI | TTGTTGTCACGCTCCTGGTC | GATGAGACCGGGTTCCCTCA |

| Bdnf exon IX | TTCCTCCAGCAGAAAGAGCA | TCCCTGGCTGACACTTTTGA |

| Gapdh | GGATGCAGGGATGATGTTC | TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAG |

| Groups of dams | Litter size (mean ± SEM) | No. of pups born | No. of males and females | Body weight of pups (g) | Changes in body weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTL-VEH | 12.00 ± 0.16 | 11 to 13 | M = 4.66 ± 0.40 F = 7.33± 0.12 |

PD1=7.00 ± 0.09 PD21= 48.50 ± 1.17 |

41.00 ± 1.20 |

| PS-VEH | 10.66 ± 0.10 | 10 to 11 | M = 5.33 ± 0.14 F = 5.33 ± 0.14 |

PD1=6.60 ± 0.09 PD21=34.00 ± 0.57 |

27.50 ± 0.58* |

| CTL-RESV | 10.33 ± 18.85 | 9 to 12 | M = 4.66 ± 0.40 F= 5.66 ± 0.74 |

PD1=6.70 ± 0.11 PD21=47.40 ± 0.66 |

40.60 ± 0.67 |

| PS-RESV | 12.66 ± 2.05 | 12 to 13 | M = 4.33 ± 0.43 F= 8.33 ± 0.41 |

PD1=7.08 ± 0.13 PD21=51.20 ± 0.94 |

44.30 ± 0.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).