Submitted:

29 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This article examines the cinephilia of film downloaders between the end of the Napster era (the first P2P network shut down by US authorities in 2001) and that of MegaUpload, shut down in 2012 by New Zealand authorities. This decade has been characterized by the gradual disappearance of the technological barriers that have long hampered the downloading of large files, in tandem with the spread of ADSL and the rise of streaming[1] . Few studies, however, have looked at downloading and streaming from the perspective of the sociology of consumption, considering these content appropriation practices as a means of determining a trend in cinephiles' taste for the cinema object. On the basis of a qualitative survey, we look at the motivations behind downloading and streaming, relating them to the emergence of new cinephilic behaviours ("niche" and "rarity" cinephilias). Today, these indicators converge to suggest that downloading films is a way of appropriating images that has become commonplace, with few differences from other uses of cinephilia consumed on the big screen.

Keywords:

1. Film Awareness and Distribution Channels: From Experience to the Viewer's Expertise

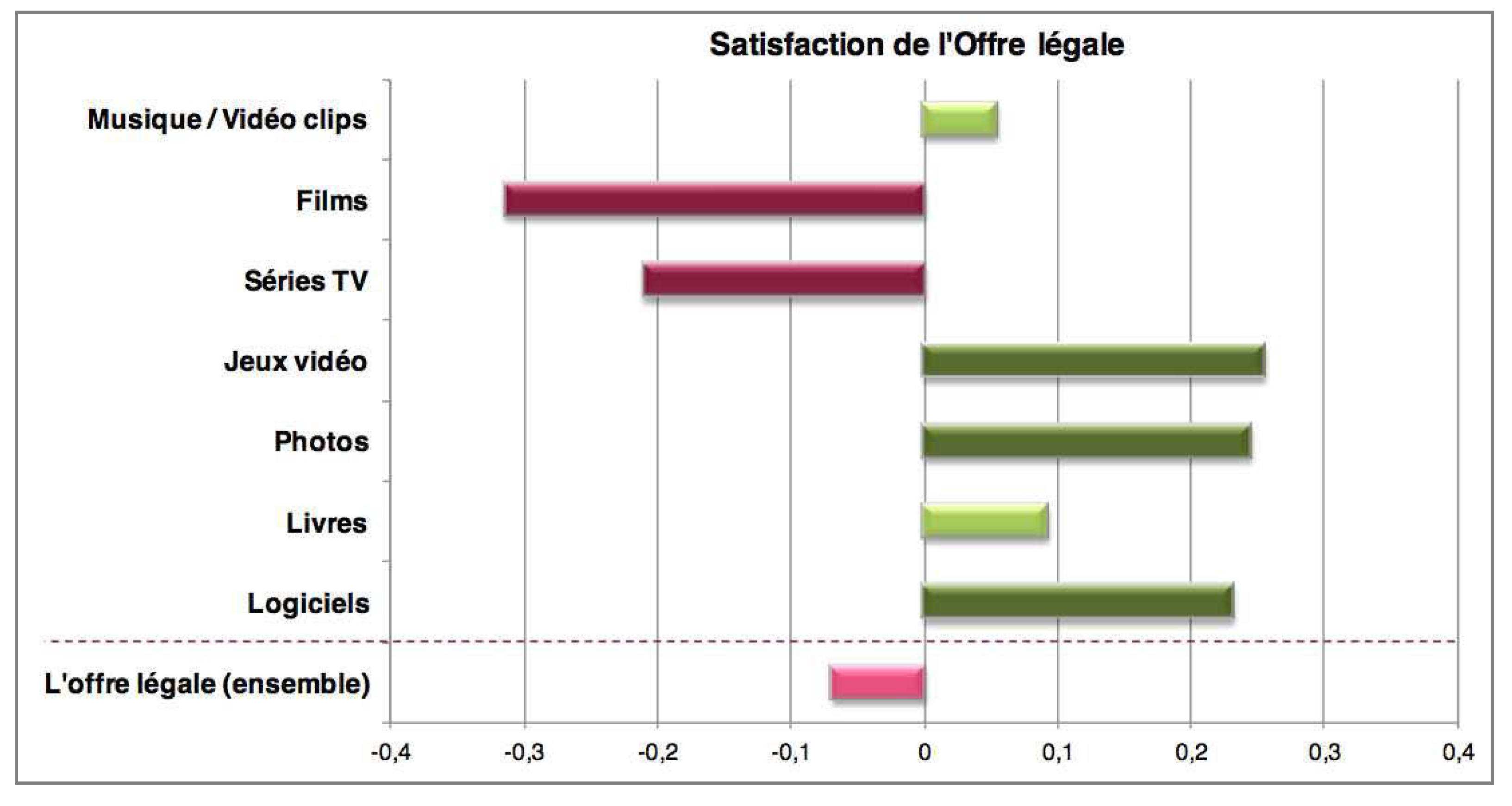

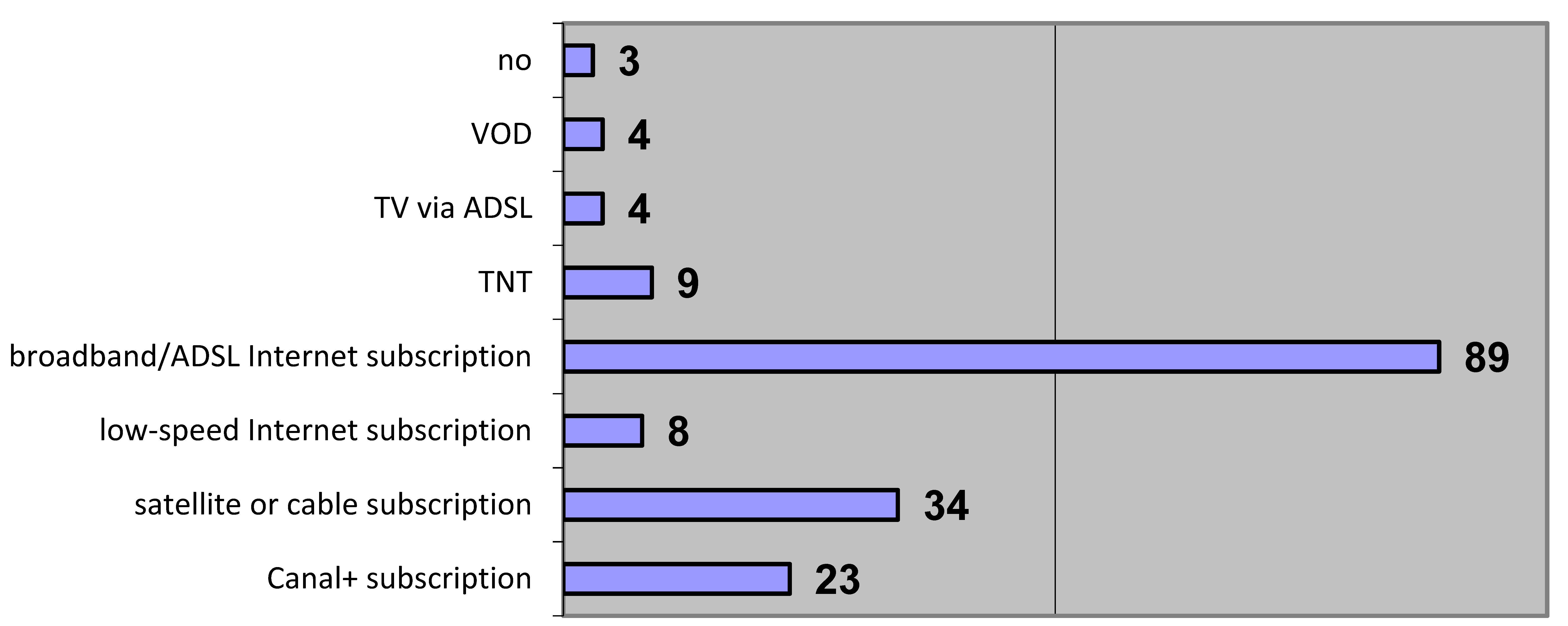

2. Dissatisfaction with the Legal Film Offer

3. Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Downloading as a Means of Contesting the Legal Offer

4. The Survey “Downloading Movies: A New Way of Consuming Images?”

4.1. Survey Protocol and General Data

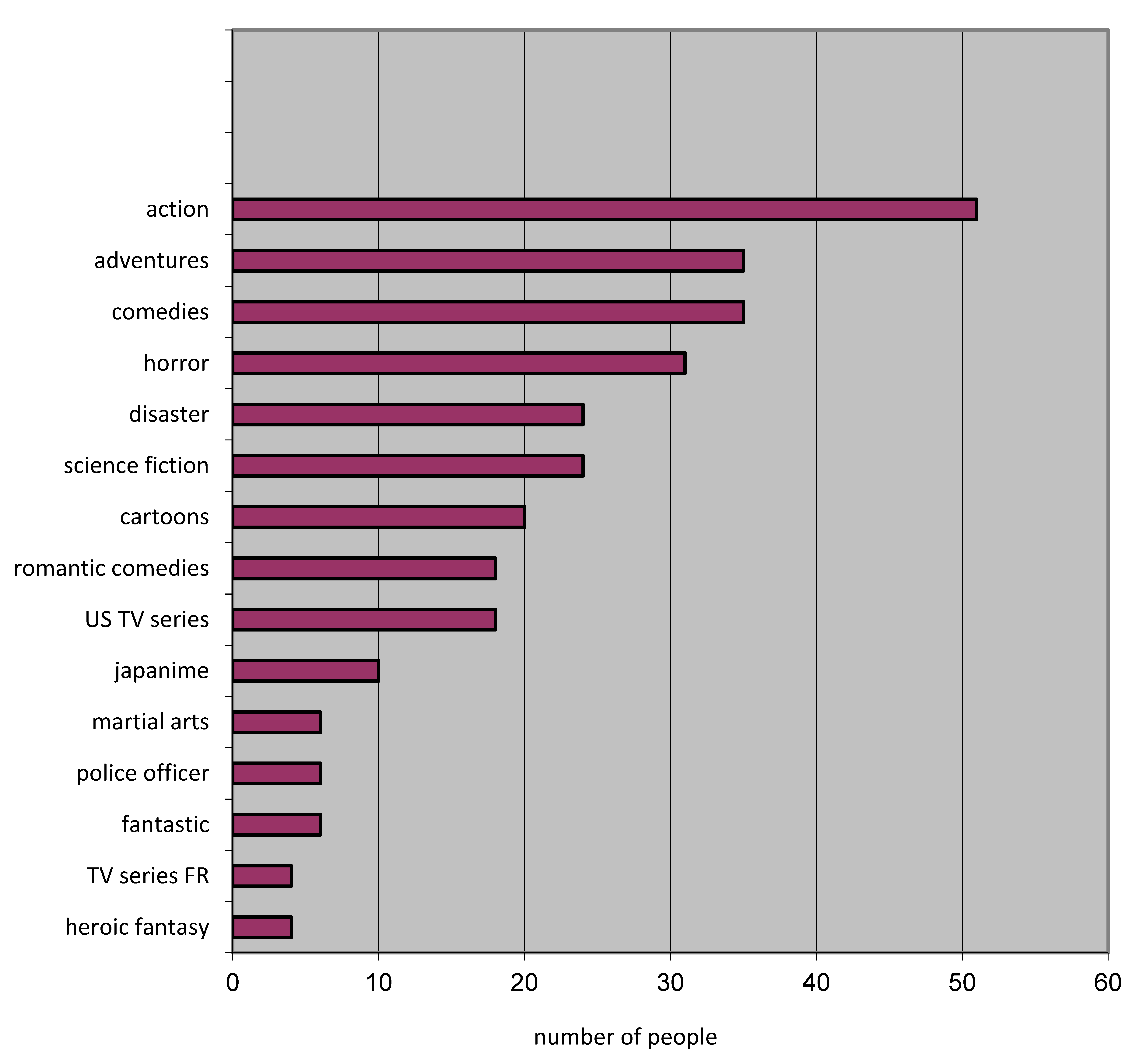

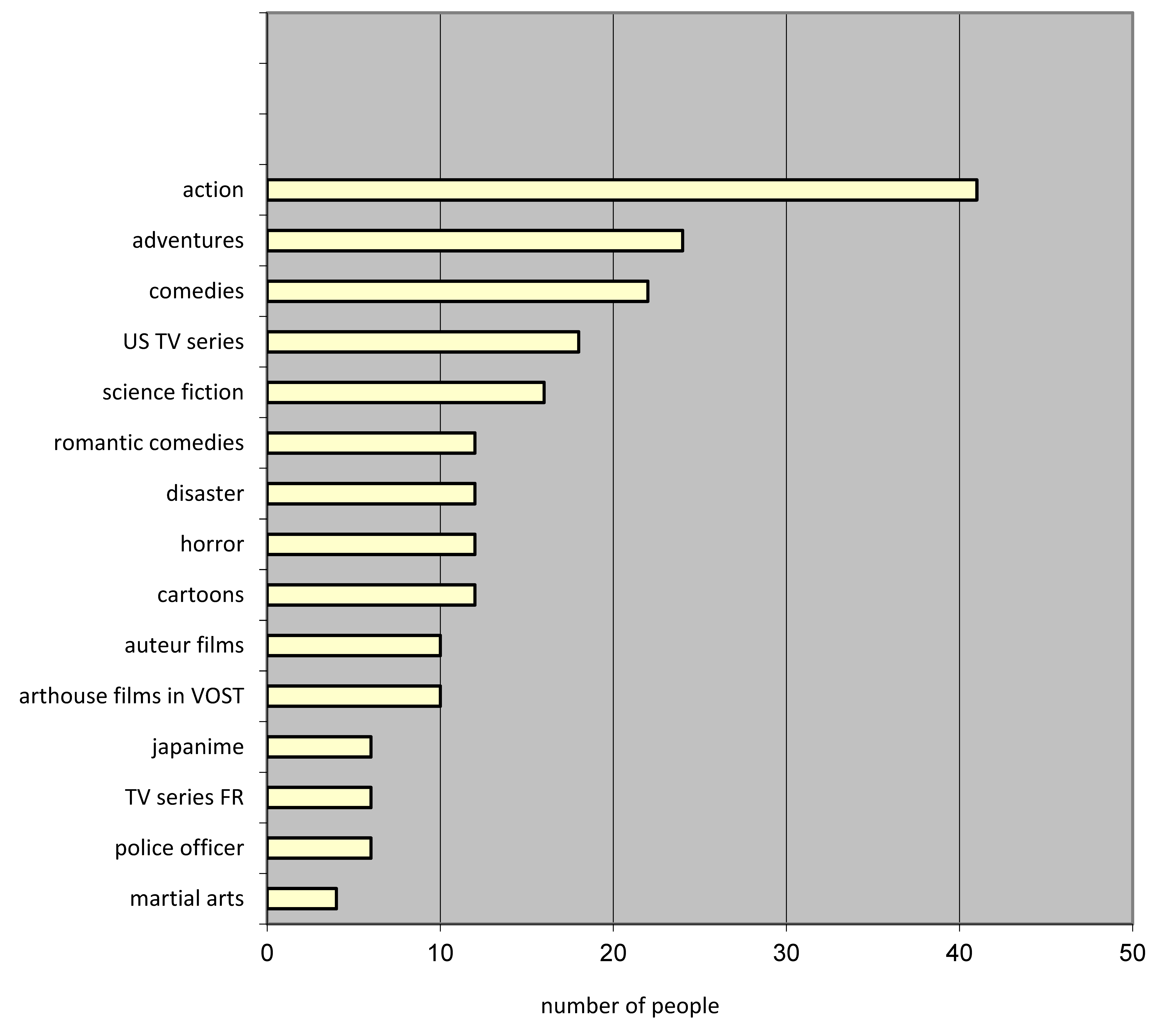

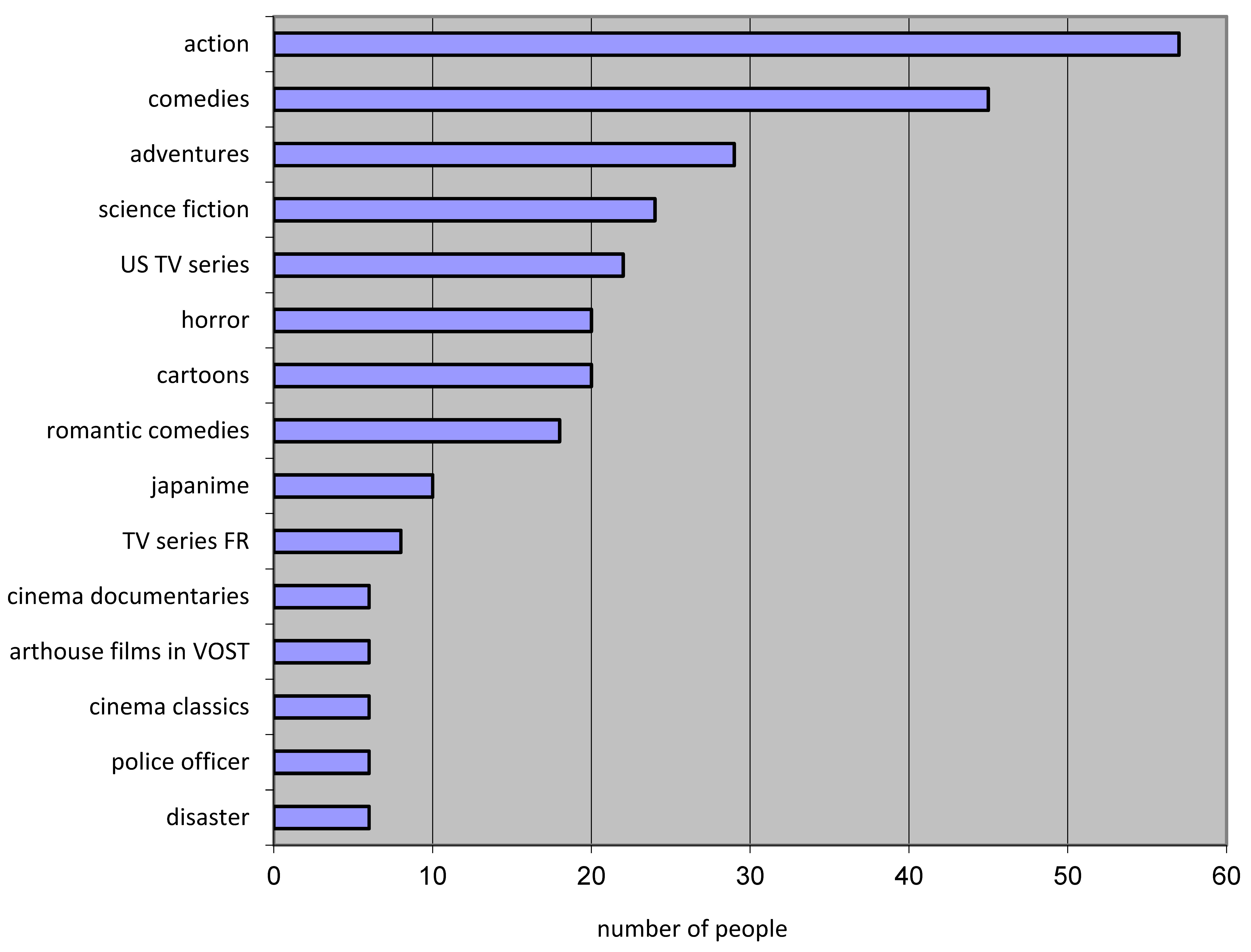

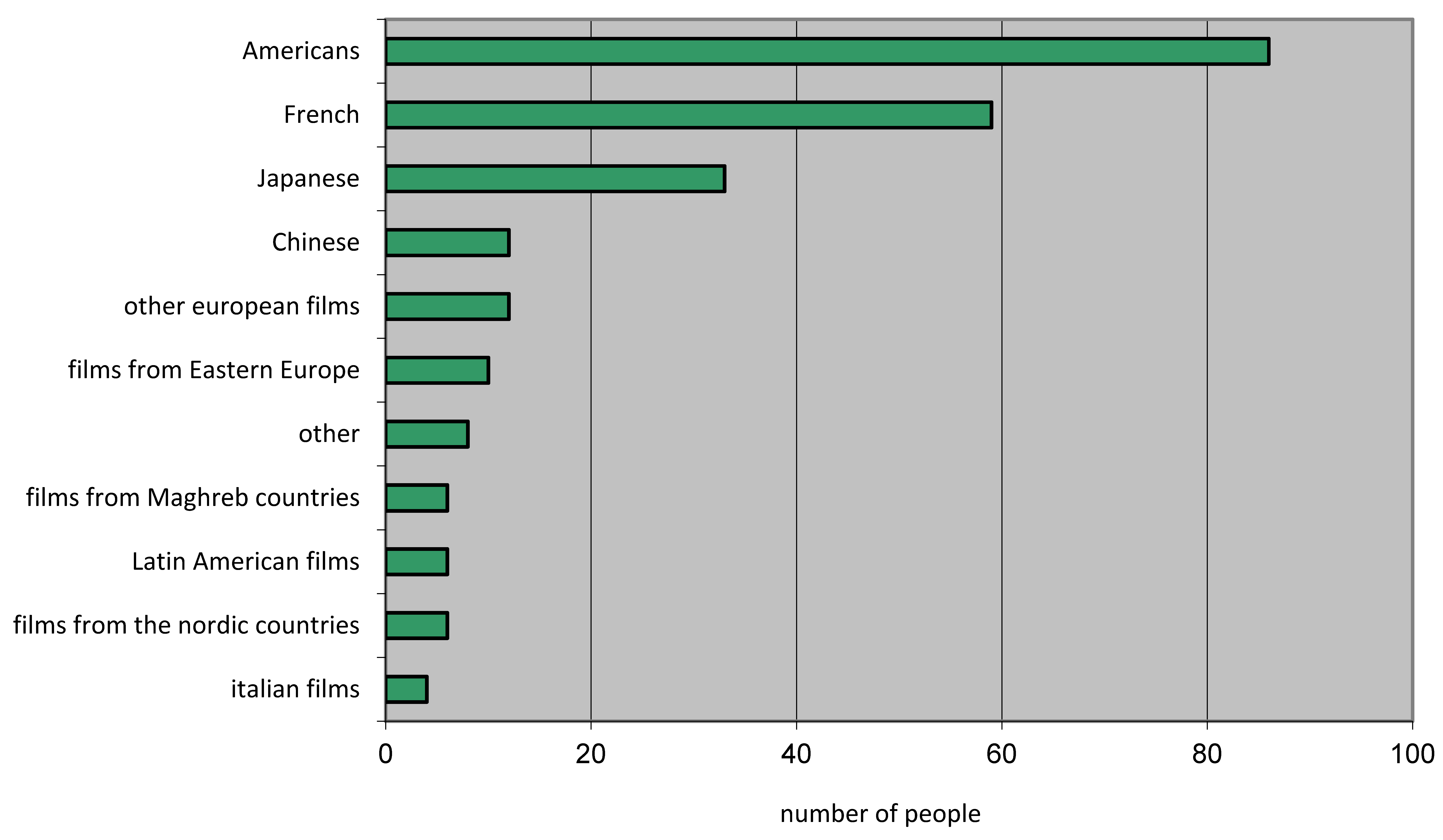

4.2. Favourite Film Genres

4.3. DVD Purchase and Rental

4.4. Downloading and Consumption of the Downloaded Film.

4.5. Various Opinions and Views

5. Conclusions

Appendix A. Survey Results "Downloading Films: A New Way Of Consuming Images”

|

|

|

|

|

| Downloaders declare that: | ||

| Rank 1 | It's word of mouth that makes them want to buy a DVD | 35% |

| Rank 2 | They mostly buy films they've seen before | 33% |

| Rank 3 | They read reviews before buying | 22% |

| Rank 4 | They choose according to the publicity surrounding the film | 16% |

| Rank 5 | They only buy DVDs on sale | 16% |

| Rank 6 | It's the extras that make the difference between buying a DVD or not. | 8% |

| Downloaders declare that: | ||

| Rank 1 | They know exactly which films they want to download before they log on. | 76% |

| Rank 2 | They don't know what movies they're going to download before they log on | 22% |

| Rank 3 | Using P2P networks makes it easier for them to find film-related products in traditional distribution channels. | 18% |

| Rank 4 | Using P2P networks has enabled them to meet people who share the same taste in cinema. | 4% |

| Downloaders sometimes find films on P2P networks that are impossible to find elsewhere: | ||

| Rank 1 | Sometimes | 26% |

| Rank 2 | Don't look for "rare pearls | 12% |

| Rank 3 | Often | 8% |

| Rank 4 | Rarely | 6% |

| The majority of Internet users say: | |

| Be interested in Internet access to audiovisual content | 61% |

| P2P networks have changed their cultural practices | 44% |

| That their film culture has grown thanks to P2P networks | 65% |

| That going to the movies is still worthwhile today | 94% |

| That unpaid downloading is not a fad | 77% |

| Internet downloading is revolutionizing the way we consume images | 81% |

| That the term "piracy" is appropriate to the practice of downloading and streaming | 55% |

References

- AKERLOF, George A. 1970. "The Market for 'Lemons': Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism". Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 84, n°3, pp. 488-500.

- BENSON-ALLOTT, Caetlin. Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens: Video Spectatorship From VHS to File Sharing; University of California Press: Berkeley, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ANDERSON, Chris. The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More; Hyperion: New York, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- BECKER, Jan; CLEMENT, Michel. 2006. Dynamics of Illegal Participation in Peer-to-Peer Networks-Why Do People Illegally Share Media Files? Journal of Media Economics, Vol. 19, Issue 1, pp.7-32.

- BENHAMOU, Françoise. Economics of the star system; Odile Jacob: Paris, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- BERGÉ, Armelle; GRANJON, Fabien. 2005. "Relational networks and cultural eclecticism," Revue LISA/LISA e-journal [Online], Media, culture, history, Culture and society. Online January 1,2005. URL: http://lisa.revues.org/909.

- CALLON, Michel; LASCOUMES, Pierre; BARTHE, Yannick. 2001. Agir dans un monde incertain. Essay on technical democracy. Paris: Le Seuil (collection "La couleur des idées").

- CARDOSO, Gustavo. P2P in the Networked Future of European Cinema. International Journal of Communication 2012, 6, 795–821. [Google Scholar]

- CHAO, Chiang-Nan; ZHAO, Saibei. "Emergence of Movie Stream Challenges Traditional DVD Movie Rental-An Empirical Study with a User Focus". International Journal of Business Administration 2010, 4(3), 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- CHAO, Chiang-Nan; Tiger, LI. "Movie Download Challenges Traditional Movie Rental". International Journal of Business, Marketing, and Decision Sciences, 2010; 3, 2, 78–87. [Google Scholar]

- CHARTOIRE, Renaud. Distinction, omnivority and dissonance: The example of 'bis' cinema. Idées 2007, 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- CMPDA. 2011. "Economic Consequences of Film Piracy in CANADA", February.

- DE VANY, Arthur; WALLS, David. 1999. "Uncertainty in the Movie Industry: Does Star Power Reduce the Terror of the Box Office?", Journal of Cultural Economics, n° 23, pp. 285-318.

- DE VANY, Arthur; WALLS, David. 2002. "Movie Stars, Big Budgets, and Wide Releases: Empirical Analysis of the Blockbuster Strategy". working paper, University of California at Irvine.

- ENGLISH, James. The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Cultural Value; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- FLICHY, Patrice. 2010. Le sacre de l'amateur. Sociologie des passions ordinaires à l'ère numérique. Paris: Seuil.

- FOREST, Claude, 2010. Which film to see? Pour une socioéconomie de la demande de cinéma. Villeneuve-D'Ascq: Septentrion.

- FREY, Bruno; NECKERMANN, Susanne. 2008. Who is Who? - The Economics of Awards. Working paper. pp. 1-35.

- -. 2009. "Awards: A Disregarded Source of Motivation". Rationality, Markets and Morals, Vol. 0, n°1, pp. 177-182.

- GIMELLO-MESPLOMB, Frédéric. 2005. "Peut-on responsabiliser les nouveaux modes de consommation de l'audiovisuel?", in La libération audiovisuelle - Enjeux technologiques, économiques et réglementaires (edited by Thomas Paris), Paris: Éditions Dalloz, pp. 165-192.

- GIMELLO MESPLOMB, Frédéric. 2012. "Three new 'grey areas' in the light of sociotechnical developments in cinema: the economics of notoriety, uncertainty and drag phenomena," Mise au point [Online], 4 2012, Online since 21 August 2012: http://journals.openedition.org/map/762. [CrossRef]

- GIMELLO-MESPLOMB, Frédéric. 2024. "Hundred Years of French Film Policy (1925-2025). Power, Policy, and Aesthetic Values Within State Intervention for Film Production in France." SocArXiv. December 6. [CrossRef]

- GIMELLO-MESPLOMB, Frédéric. 2024. "The Invention of the Spectator: How Has Early Film Spectatorship Shaped Audience and Reception Theory. Selected Writings (1900s-1910s)". New York - London: Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- GIMELLO-MESPLOMB. Frédéric. 2024. "THE 1910s: PIONEERING INSIGHTS INTO AUDIENCES STUDIES". The Invention of the Spectator: How has Early film Spectatorship shaped Audience and Reception Theory. Selected Writings (1900s-1910s), Zenodo, 2024, Media and Cultural Studies, 9791043111785. ⟨10.5281/zenodo.14315753⟩. ⟨halshs-04830093⟩.

- GIMELLO-MESPLOMB. Frédéric. 2000. « Enjeux et stratégies de la politique de soutien au cinéma français: un exemple: la nouvelle vague: économie politique et symboles ». Université Toulouse II.

- GRANJON, Fabien. 2005. "De quelques considérations sur la notion d'éclectisme culturel", Working paper. Published online March 29, 2006. URL: http://w3.u-grenoble3.fr/les_enjeux/2005/Granjon-Berge/home.html.

- HADOPI. 2008. "Impact économique de la copie illégale des biens numérisés en France: Quand le chaos économique s'immisce dans la révolution technologique". Research report. Paris: Hadopi.

- -. 2013. "Access to works on the Internet: inventory and analysis of uses". Research report. Paris: Hadopi, Département Recherche, Etudes et Veille (DREV).

- -. 2013. "Strategies for accessing dematerialized works - Qualitative & quantitative synthesis". Research report. Paris: Hadopi, Département Recherche, Etudes et Veille (DREV).

- HIRSCHMAN, Alfred. 1970. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge (US): Harvard University Press. Translated into French in 1972, Face au déclin des entreprises et des institutions. Paris: Ed. Ouvrières (Economie et humanisme), 1970.

- HUTTER, Michael; THROSBY, David. 2008. Beyond Price: Value in Culture, Economics, and the Arts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Chapter 1: "Value and Valuation in Art and Culture: Introduction and Overview".

- IDATE. 2012. "Study of the economic model of sites or services for streaming and direct downloading of illicit content". Final report. Paris, Idate/Hadopi. URL: http://www.hadopi.fr/sites/default/files/page/pdf/Rapport_IDATE.pdf.

- IFOP - digital media. 2010. "The French and Illegal Downloading. Study report. July 2010". Paris: IFOP.

- KARPIK, Lucien. 2010. Valuing The Unique: The Economics Of Singularities. Priceton: Princeton University Press.

- LAHIRE, Bernard. La Culture des individus. Dissonances culturelles et distinction de soi; La Découverte: Paris, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- LESCURE, Pierre. 2013. Rapport de Mission " Acte II de l'exception culturelle ", " Contribution aux politiques culturelles à l'ère numérique ". Paris : Ministère de la Culture. 2 volumes.

- LEVERATTO, Jean-Marc; JULLIER, Laurent. Cinéphiles et cinéphilie, une histoire de la qualité cinématographique; Colin: Paris, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- LIEBOWITZ, Stan J. 2006. "Economists Examine File-Sharing and Music Sales", in Illing G. and M. Peitz (eds), Industrial Organization and the Digital Economy, MIT press, Cambridge.

- NECKERMANN, Susanne; FREY Bruno S. 2007. "Awards as Incentives". SSRN Electronic Journal, pp. 1-41.

- NICOLAS, Yann. 2005. "Le téléchargement sur les réseaux de pair à pair", Développement Culturel, n° 148, June 2005; published online [http://www.culture.gouv.fr/dep] ; October 15, 2005.

- SAROIU, Stefan; and ali. 2002. "Measurement study of peer-to-peer file sharing systems", Proc. SPIE 4673, Multimedia Computing and Networking 2002, 156 (December 10, 2001).

- THROSBY, David. 2010. "Economic analysis of artists' behaviour: some current issues", Revue d'économie politique, Dalloz, 0 (1), pp. 47-56.

- WALLS David W. "Superstars and heavy tails in recorded entertainment: empirical analysis of the market for DVDs". Journal of Cultural Economics, Vol. 34, n°4, 2010, pp. 261-279.

- WENGER, Etienne. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- WERBACH, Kevin. "The implications of video peer-to-peer on network usage". In Peer-to-peer video: The economics, policy, and culture of today's new mass medium; E. M., Noam, L. M., Pupillo, Eds.; Springer: New York, 2008; pp. 95–128. [Google Scholar]

- WOJNAS, Olivia. 2005. " L'échange de films en Peer-to-peer: une sociologie des usages ". Master's thesis in cinema (ed. F. Gimello-Mesplomb). Université de Metz, Service Commun de Documentation.

- ZAFIRAU, Stephen. "Reputation Work in Selling Film and Television: Life in the Hollywood Talent Industry". Qualitative Sociology 2007, 31(2), 99–127. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | This practice has grown considerably since 2010, particularly for the consumption of music (63%) and TV series (42%), according to a report by Hadopi's Research, Studies and Monitoring Department (DREV) "Stratégies d'accès aux œuvres dématérialisées - Synthèse qualitative & quantitative - Novembre 2013", pp. 57-58. |

| 2 | This practice has grown considerably since 2010, particularly for the consumption of music (63%) and TV series (42%), according to a report by Hadopi's Research, Studies and Monitoring Department (DREV) "Stratégies d'accès aux œuvres dématérialisées - Synthèse qualitative & quantitative - Novembre 2013", pp. 57-58. |

| 3 | Frédéric Gimello-Mesplomb, "Peut-on responsabiliser les nouveaux modes de consommation de l'audiovisuel?", in La libération audiovisuelle - Enjeux technologiques, économiques et réglementaires (ed. Thomas Paris), Paris: Éditions Dalloz, 2005, pp. 165-192; Olivia Wojnas, "L'échange de films en Peer-to-peer: une sociologie des usages". Master's thesis in cinema (ed. F. Gimello-Mesplomb). Université de Metz, 2005. |

| 4 | Chris Anderson, The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More, New York, Hyperion, 2006. |

| 5 | Laurent Jullier and Jean-Marc Leveratto, Cinéphiles et cinéphilie: histoire et devenir de la culture cinématographique, Armand Colin, 2010; Patrice Flichy, Le sacre de l'amateur. Sociologie des passions ordinaires à l'ère numérique, Seuil, 2010. |

| 6 | Fabien Granjon. "De quelques considérations sur la notion d'éclectisme culturel", Working paper. Published online March 29, 2006. URL: http://w3.u-grenoble3.fr/les_enjeux/2005/Granjon-Berge/home.html; Armelle Bergé and Fabien Granjon, "Réseaux relationnels et éclectisme culturel", Revue LISA/LISA e-journal [Online], Media, culture, history, Culture and society, January 2005, URL: http://lisa.revues.org/909. |

| 7 | CNC, "Le téléchargement de films sur Internet. Analyse quantitative: Profil sociodémographique du téléchargeur", pp. 15-18. See also http://www.hadopi-data.fr, statistics on 518 Internet subscribers who received a warning from the Haute Autorité pour la Diffusion des Oeuvres et la Protection des Droits sur Internet (Hadopi). |

| 8 | IDATE report "Etude du modèle économique de sites ou services de streaming et de téléchargement direct de contenus illicites" Final report - March 21, 2012. Haute Autorité pour la diffusion des œuvres et protection des droits sur Internet, 2012. |

| 9 | Stephen Zafirau, "Reputation Work in Selling Film and Television: Life in the Hollywood Talent Industry". Qualitative Sociology Vol. 31, n°2, 2007, pp. 99-127; Bruno S. Frey; Susanne Neckermann, "Awards: A Disregarded Source of Motivation". Rationality, Markets and Morals, Vol. 0, n°1, 2009, pp. 177-182; James English, The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Cultural Value. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008. |

| 10 | Bernard Lahire, La Culture des individus. Dissonances culturelles et distinction de soi, Paris, La Découverte, 2006. |

| 11 | Laurent Jullier, Star Wars. Anatomie d'une saga, Paris, Armand Colin Cinéma, 2005. |

| 12 | Allard Laurence. "Cinéphiles, à vos claviers ! Réception, public et cinéma". In: Réseaux, 2000, volume 18 n°99. pp. 131-168. |

| 13 | See James English's work on awards: The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Cultural Value, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2008. |

| 14 | Pierre-Jean Benghozi and Françoise Benhamou: "Longue traîne: levier numérique de la diversité culturelle?" Culture prospective - production, diffusion and markets, DEPS, Ministère de la Culture, n° 1, 2008. |

| 15 | Arthur De Vany and David Walls, "Movie Stars, Big Budgets, and Wide Releases: Empirical Analysis of the Blockbuster Strategy", working paper, University of California at Irvine, 2002; "Superstars and Heavy Tails in Pre-Recorded Entertainment: Empirical Analysis of the Market for DVDs," Working Papers 2009-20, Department of Economics, University of Calgary, revised 26 Oct 2009. |

| 16 | Hadopi, "Première vague du baromètre de l'offre légale", April 2013 [online]: http://www.hadopi.fr/actualites/actualites/premiere-vague-du-barometre-de-loffre-legale [page consulted July 27, 2013]. |

| 17 |

Ibid. |

| 18 | As of 1/08/2013. |

| 19 |

http://my.dvdlib.be/viewtopic.php?t=8 [page consulted on July 27, 2013]. |

| 20 |

http://films-inedits.leforum.tv [page consulted on July 27, 2013]. |

| 21 | Qualiquanti, "La Piraterie de films: motivations et pratiques des Internautes. Analyse qualitative", May 2004, study commissioned by the CNC, [http://www.qualiquanti.com/pdfs/pirateriefilms.pdf]; [page consulted July 27, 2013]. |

| 22 | ALPA, "L'offre "pirate" de films sur Internet". Study commissioned by the CNC, October 2004, [http://www.cnc.fr/b_actual/fr_b2.htm] ; [page consulted July 27, 2013]. |

| 23 | Cf. Hadopi Barometer, "Usages de biens culturels sur Internet: pratiques et perception des internautes français", Hadopi, July 2013. |

| 24 | Hadopi barometer, "Usages de biens culturels sur Internet: pratiques et perception des internautes français", Hadopi, July 2013. |

| 25 | Aram Sinnreich, "Digital Music Subscriptions: Post-Napster Product Formats," Jupiter Research, 2000. |

| 26 | Yann Nicolas, "Le téléchargement sur les réseaux de pair à pair", in Développement Culturel issue 148 (June 2005); published online [http://www.culture.gouv.fr/dep]; October 15, 2005. |

| 27 | We're not talking here about the artistic quality of the film, but about an objective quality: that of the files viewed, the viewing and reception conditions. |

| 28 | CSA. "National pay-TV channels in France": http://www.csa.fr/Television/Les-chaines-de-television/Les-chaines-hertziennes-terrestres/Les-chaines-nationales-payantes [page consulted on 18/08/2013] |

| 29 | Hadopi barometer, "Usages de biens culturels sur Internet: pratiques et perception des internautes français", Hadopi, July 2013. |

| 30 | Jupiter-Research (2009). "Analysis Of The European Online Music Market Development And Assessment of Future Opportunities. Study on online music piracy and purchasing habits". New York: IFPI. |

| 31 | Lahiri, Atanu and Dey, Debabrata, "Effects of Piracy on Quality of Information Goods". Management Science, Vol. 59, No. 1, January 2013, pp. 245-264. |

| 32 |

Cf. Laurent Jullier and Jean-Marc Leveratto, Cinéphiles et cinéphilie: histoire et devenir de la culture cinématographique, Armand Colin, 2010. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).