Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- -

- -

- mobility of pleural line, in particular, the presence of sliding sing;

- -

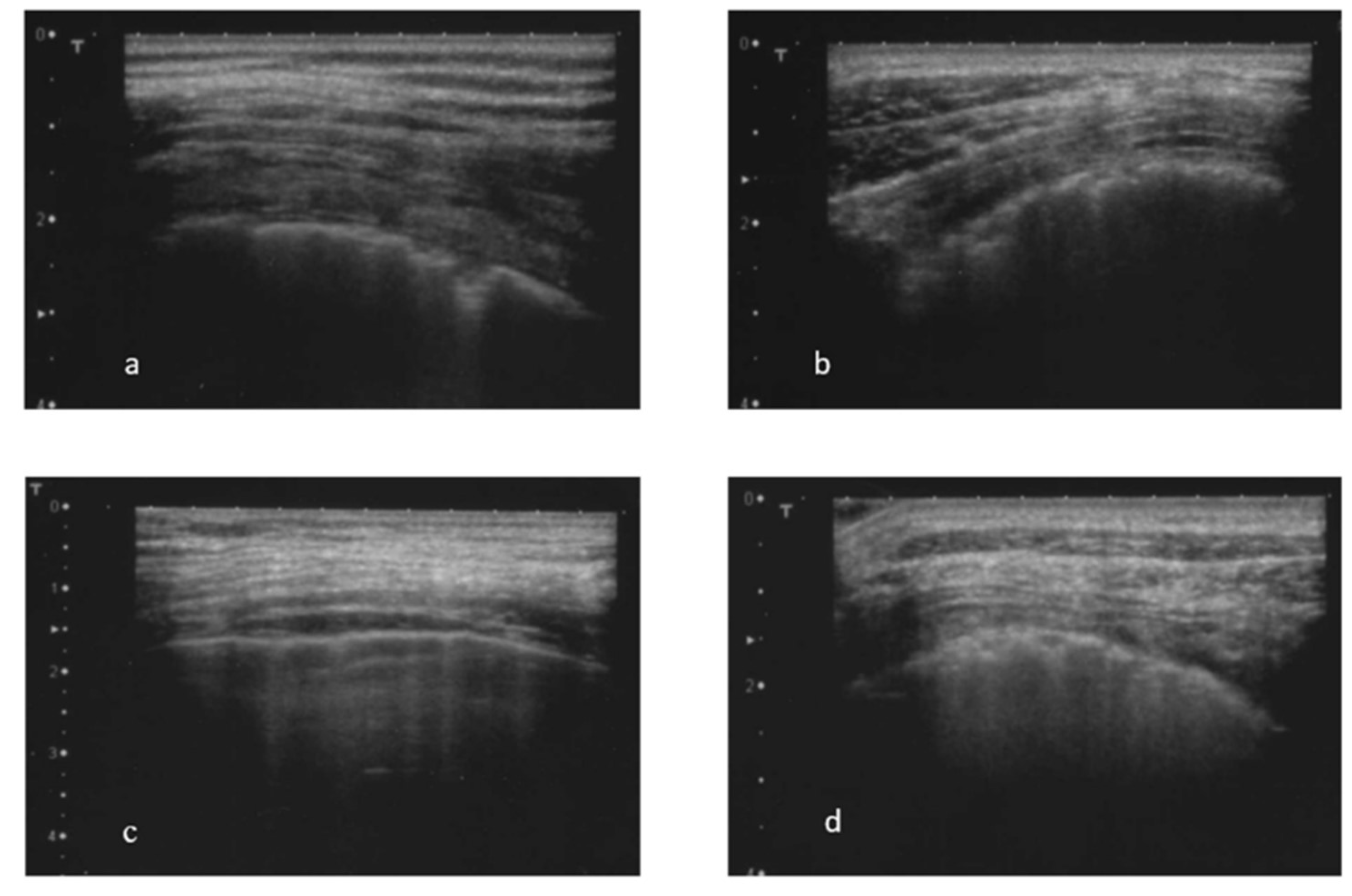

- the presence and the total number of B-lines (abnormal in the presence of 3 or more B-lines in at least two consecutive scans or the presence of at least 5 B-lines in the entire intercostal space examined) (Figure 1 c) [30; 32]. The total number of B-lines was given by the sum of all the B-lines found in the different fields examined;

- -

- the presence of almost one subpleural cyst (Figure 1 d), defined as hypo-echoic lesions that interrupt the pleural line;

- -

- the presence of the pleural effusion.

Statistical Analysis.

Ethics Approval.

3. Results

3.2. Figures, and Tables

| No-ILD | UIP | NSIP with GGO | NSIP with GGO and reticulations | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 57 (36,5%) | 25 (16%) | 46 (29,5%) | 28 (18%) | |

| F/M | 55 (96%) / 2 (3%) | 23 (92%) / 2 (8%) | 43 (93%) / 3 (6%) | 27 (96%) / 1 (4%) | 0.788 |

| Age (years) | 57.5 ± 14.4 | 60.4 ± 11.0 | 58.2 ± 11.5 | 62.2 ± 10.1 | 0.370 |

| Disease duration (years) | 9.7 ± 6.9 | 10.9 ± 5.9 | 7.4 ± 5.9 | 7.8 ± 7.7 | 0.479 |

| BMI | 25.9 ± 4.1 | 25.2 ± 6.1 | 25.2 ± 4.3 | 26.1 ± 4.5 | 0.170 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 19.3 ± 14.8 | 17.6 ± 14 | 17.7 ± 13.1 | 24.5 ± 14.4 | 0.242 |

| CRP (mg/l) | 4.8 ± 4.8 | 5.0 ± 1.1 | 7.5 ± 1.3 | 9.6 ± 1.8 | 0.238 |

| ENA | |||||

| Anti CENP-B | 42 (74%) | 3 (12%) | 6 (13%) | 6 (23%) | 0.0001^ |

| Anti Scl-70 | 10 (17,5%) | 19 (76%) | 36 (78%) | 17 (65%) | 0.0001” |

| Nailfold Videocapillaroscopy | |||||

| Early scleroderma pattern | 16 (32%) | 4 (20%) | 16 (40%) | 4 (17%) | 0.440 |

| Active scleroderma pattern | 24 (45%) | 8 (40%) | 15 (37%) | 12 (52%) | 0.786 |

| Late scleroderma pattern | 13 (24%) | 8 (40%) | 9 (22,5%) | 7 (30%) | 0.443 |

| Cutaneous subsets | |||||

| Limited | 49 (86%) | 20 (80%) | 34 (74%) | 25 (89%) | 0.292 |

| Diffuse | 8 (14%) | 5 (20%) | 12 (26%) | 3 (11%) | 0.296 |

| Presence of LUS abnormalities | |||||

| Sliding sign | 0 (0%) | 5 (20%) | 2 (4%) | 5 (18,5%) | 0.002 § |

| Pleural line irregularity | 15 (26%) | 24 (96%) | 35 (76%) | 27 (96%) | 0.0001^ |

| Pleural thickness | 2 (3,5%) | 18 (72%) | 16 (36%) | 18 (64%) | 0.0001° |

| B-lines | 10 (17,5%) | 14 (56%) | 43 (93,5%) | 27 (96%) | 0.0001# |

| B-lines number | 3.5 ± 16.1 | 29.0 ± 10.2 | 69.5 ± 10.7 | 56.6 ± 11.8 | 0.0001# |

| Subpleural cystis | 5 (9%) | 14 (58%) | 10 (24%) | 13 (48%) | 0.0001@ |

| Pleural effusion | 2 (3,5%) | 4 (16%) | 2 (4%) | 4 (14%) | 0.103 |

| PFT | |||||

| FVC% baseline | 108.1 ± 14.4 | 84.8 ± 18.3 | 99.5 ± 15.4 | 84 ± 19.4 | 0.0001& |

| DLCO% baseline | 77.1 ± 16.9 | 77.2 ± 17 | 77.7 ± 18 | 69.1 ± 18.5 | 0.627 |

| TLC% baseline | 101.6 ± 12.9 | 75.2 ± 11 | 92.9 ± 16.2 | 91.8 ± 33 | 0.059 |

| Other lung CT abnormalities | |||||

| Micro nodules | 6 (13%) | 8 (32%) | 26 (56.5%) | 9 (32%) | 0.0001* |

| Warrick Score | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 10.2 ± 4.0 | 8 ± 3.4 | 10.8 ± 1.7 | 0.0001$ |

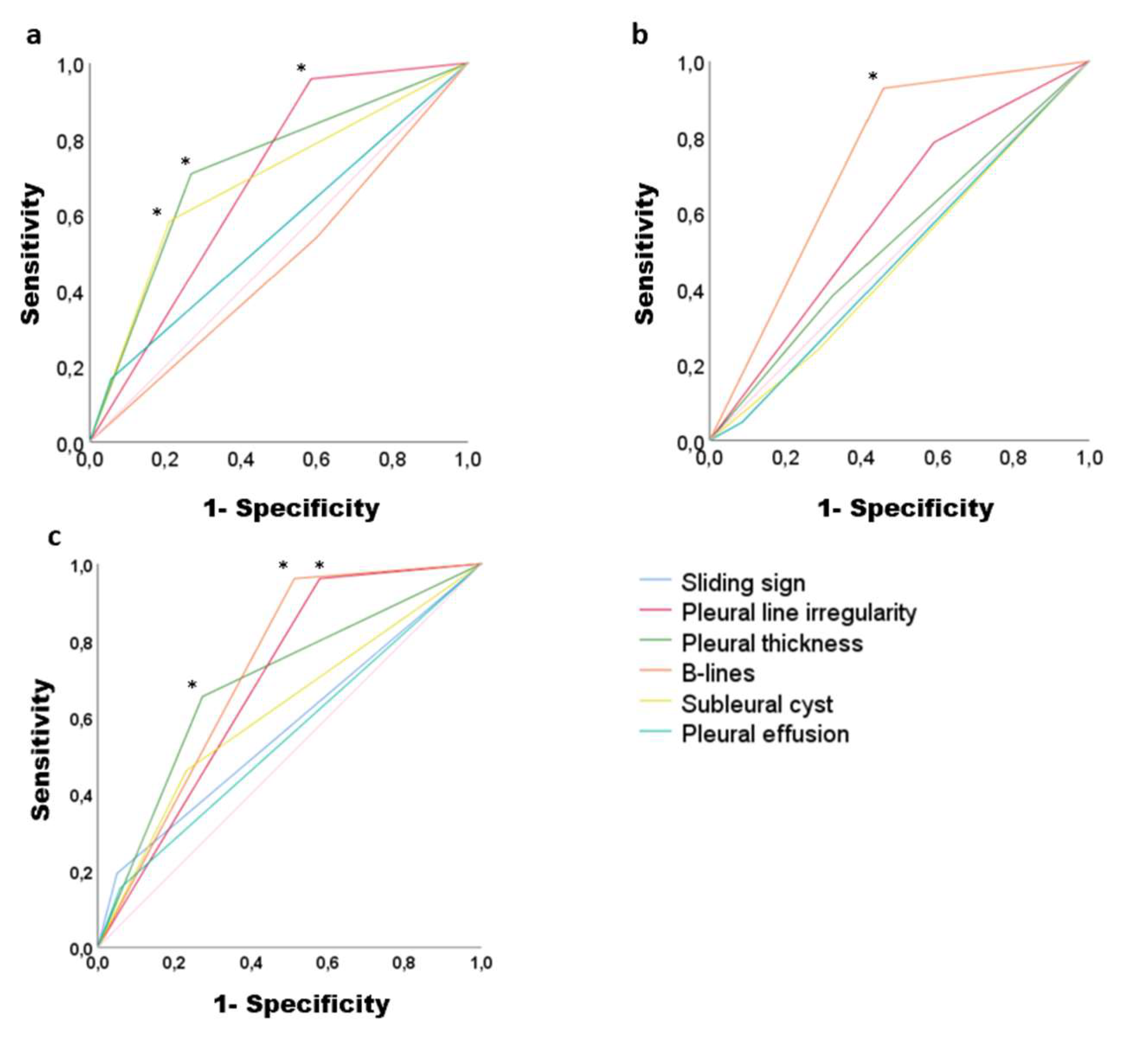

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UIP CT lungs pattern | ||||

| Sliding sign | 16.7% | 95% | 0.55 (0.42-0.68) | 0.396 |

| Pleural line irregularity | 95.8% | 41.5% | 0.68 (0.58-0.78) | 0.004 |

| Pleural thickness | 70.8% | 73.2% | 0.72 (0.60-0.83) | 0.001 |

| B-lines | 54.2% | 39.8% | 0.47 (0.34-0.59) | 0.643 |

| Subpleural cyst | 58.3% | 78.9% | 0.68 (0.56-0.81) | 0.004 |

| Pleural effusion | 16,7% | 95% | 0.55 (0.42-0.68) | 0.396 |

| NSIP with GGO CT lungs pattern | ||||

| Sliding sign | 48% | 91.4% | 0.48 (0.37-0.58) | 0.719 |

| Pleural line irregularity | 78.6% | 41% | 0.59 (0.49-0.69) | 0.065 |

| Pleural thickness | 38.1% | 67.6% | 0.52 (0.42-0.63) | 0.589 |

| B-lines | 92.9% | 54.3% | 0.73 (0.65-0.81) | 0.0001 |

| Subpleural cysts | 23.8% | 71.4% | 0.47 (0.37-0.57) | 0.653 |

| Pleural effusion | 4.8% | 91.4% | 0.48 (0.37-0.58) | 0.719 |

| NSIP with GGO and reticulation CT lungs pattern | ||||

| Sliding sign | 19% | 95% | 0.57 (0.44-0.70) | 0.254 |

| Pleural line irregularity | 96.2% | 42.1% | 0.69 (0.59-0.78) | 0.002 |

| Pleural thickness | 65.4% | 72.7% | 0.69 (0.57-0.80) | 0.002 |

| B-lines | 96.2% | 48.8% | 0.72 (0.63-0.81) | 0.0001 |

| Subpleural cyst | 47.2% | 76.9% | 0.61 (0.49-0.74) | 0.066 |

| Pleural effusion | 15.4% | 42% | 0.54 (0.42-0.67) | 0.443 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | body mass index |

| CRP | C-reactive proteins |

| ESR | erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| GGO | Ground glass opacities |

| LUS | Lung ultrasound |

| ILD | Interstitial lung disease |

| Lung HR-CT | chest high-resolution computed tomography |

| NSIP | Non-specific interstitial pneumonia |

| PFT | pulmonary function tests |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| SSc | Systemic sclerosis |

| UIP | Usual interstitial pneumonia |

References

- Walker UA, Tyndall A, Czirjak L, Denton C, Farge-Bancel D, Kowal-Bielecka O, et al. Clinical risk assessment of organ manifestations in systemic sclerosis: a report from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials And Research group database. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007, 66, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steen VD, Medsger TA. Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972–2002. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007, 66, 940–944.

- Distler, O.; Assassi, S.; Cottin, V.; Cutolo, M.; Danoff, S.K.; Denton, C.P.; Distler, J.H.; Hoffmann-Vold, A.-M.; Johnson, S.R.; Ladner, U.M.; et al. Predictors of progression in systemic sclerosis patients with interstitial lung disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 1902026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhai, M.; Meune, C.; Avouac, J.; Kahan, A.; Allanore, Y. Trends in mortality in patients with systemic sclerosis over 40 years: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Rheumatology 2012, 51, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyndall, A.J.; Bannert, B.; Vonk, M.; Airò, P.; Cozzi, F.; Carreira, P.E.; Bancel, D.F.; Allanore, Y.; Müller-Ladner, U.; Distler, O.; et al. Causes and risk factors for death in systemic sclerosis: A study from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research (EUSTAR) database. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 1809–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkmann, E.R.; Tashkin, D.P.; Sim, M.; Li, N.; Goldmuntz, E.; Keyes-Elstein, L.; Pinckney, A.; Furst, D.E.; Clements, P.J.; Khanna, D.; et al. Short-term progression of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis predicts long-term survival in two independent clinical trial cohorts. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2018, 78, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diot E, Boissinot E, Asquier E, Guilmot JL, Lemarie E, Valat C, et al. Relationship between abnormalities on high-resolution CT and pulmonary function in systemic sclerosis. Chest. 1998, 114, 1623–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells A, Hansell D, Rubens M, King A, Cramer D, Black C, et al. Fibrosing alveolitis in systemic sclerosis. Indices of lung function in relation to extent of disease on computed tomography. Arthritis Rheum. 1997, 40, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar]

- Orlandi, M.; Landini, N.; Sambataro, G.; Nardi, C.; Tofani, L.; Bruni, C.; Randone, S.B.; Blagojevic, J.; Melchiorre, D.; Hughes, M.; et al. The role of chest CT in deciphering interstitial lung involvement: Systemic sclerosis versus COVID-19. Rheumatology 2021, 28, 615. [Google Scholar]

- Clukers, J.; Lukers, J.; Lanclus, M.; Belmans, D.; van Holsbeke, C.; de Backer, W.; Vummidi, D.; Cronin, P.; Lavon, B.R.; de Backer, J.; et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis quantification of disease classification and progression with high-resolution computed tomography: An observational study. J. Scleroderma Relat. Disord. 2021, 6, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, S.R.; Veeraraghavan, S.; Hansell, D.M.; Nikolakopolou, A.; Goh, N.S.; Nicholson, A.G.; Colby, T.V.; Denton, C.P.; Black, C.M.; Du Bois, R.M.; et al. CT features of lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis: Comparison with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and non-specific interstitial pneumonia. Radiology 2004, 232, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Launay, D.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Michon-Pasturel, U.; Mastora, I.; Hachulla, E.; Lambert, M.; Delannoy, V.; Queyrel, V.; Duhamel, A.; Matran, R.; et al. High resolution computed tomography in fibrosing alveolitis associated with systemic sclerosis. J. Rheumatol. 2006, 33, 1789–1801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ruaro, B.; Baratella, E.; Confalonieri, P.; Wade, B.; Marrocchio, C.; Geri, P.; Busca, A.; Pozzan, R.; Andrisano, A.G.; Cova, M.A.; et al. High-Resolution Computed Tomography: Lights and Shadows in Improving Care for SSc-ILD Patients. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldano, S.; Trombetta, A.C.; Contini, P.; Tomatis, V.; Ruaro, B.; Brizzolara, R.; Montagna, P.; Sulli, A.; Paolino, S.; Pizzorni, C.; et al. Increase in circulating cells coexpressing M1 and M2 macrophage surface markers in patients with systemic sclerosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2018, 77, 1842–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu TYT, Hill CL, Pontifex EK, Roberts-Thomson PJ. Breast cancer and systemic sclerosis: a clinical description of 21 patients in a population-based cohort study. Rheumatol Int. 2008, 28, 895–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demizio, D.J.; Bernstein, E. Detection and classification of systemic sclerosis-related interstitial lung disease: A review. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2019, 31, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delle Sedie, A.; Doveri, M.; Frassi, F.; Gargani, L.; D’Errico, G.; Pepe, P.; Bazzichi, L.; Riente, L.; Caramella, D.; Bombardieri, S. Ultrasound Lung Comets in Systemic Sclerosis: A Useful Tool to Detect Lung Interstitial Fibrosis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2010, 28, S54. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Gargani, L.; Barskova, T.; Furst, D.E.; Cerinic, M.M. Usefulness of lung ultrasound B-lines in connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease: A literature review. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2017, 19, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargani, L.; Doveri, M.; D’Errico, L.; Frassi, F.; Bazzichi, M.L.; Delle Sedie, A.; Scali, M.C.; Monti, S.; Mondillo, S.; Bombardieri, S.; et al. Ultrasound Lung Comets in Systemic Sclerosis: A Chest Sonography Hallmark of Pulmonary Interstitial Fibrosis. Rheumatology 2009, 48, 1382–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente-Rabaneda, E.F.; Bong, D.A.; Castañeda, S.; Möller, I. Use of ultrasound to diagnose and monitor interstitial lung disease in rheumatic diseases. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 40, 3547–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairchild, R.; Chung, M.; Yang, D.; Sharpless, L.; Li, S.; Chung, L. Development and Assessment of Novel Lung Ultrasound Interpretation Criteria for the Detection of Interstitial Lung Disease in Systemic Sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res. 2021, 73, 1338–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann-Vold, A.M.; Molberg, Ø. Detection, screening, and classification of interstitial lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2020, 32, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trombetta, A.C.; Smith, V.; Gotelli, E.; Ghio, M.; Paolino, S.; Pizzorni, C.; Vanhaecke, A.; Ruaro, B.; Sulli, A.; Cutolo, M. Vitamin D deficiency and clinical correlations in systemic sclerosis patients: A retrospective analysis for possible future developments. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpicelli, G. Lung Ultrasound B-Lines in Interstitial Lung Disease. Chest 2020, 158, 1323–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013, 72, 1747–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh NS, Desai SR, Veeraraghavan S, Hansell DM, Copley SJ, Maher TM, et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: a simple staging system. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008, 177, 1248–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, Thomson CC, Inoue Y, Johkoh T, et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022, 205, e18–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpicelli G, Elbarbary M, Blaivas M et al. International evidence-based recommendations for point-of-care lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med 2012, 38, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperandeo M, Varriale A, Sperandeo G, Filabozzi P, Piattelli ML, Carnevale V, et al. Transthoracic ultrasound in the evaluation of pulmonary fibrosis: our experience. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2009, 35, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazedi-Fuerst F, Zechner P, Tripolt N, Kielhauser S, Brickmann K, Scheidl S, et al. Pulmonary echography in systemic sclerosis. Clin Rheumatol. 2012, 31, 1621–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barskova T, Gargani L, Guiducci S, Randone SB, Bruni C, Carnesecchi G, et al. Lung ultrasound for the screening of interstitial lung disease in very early systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013, 72, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee J, Im J, Ahn J, Kim Y, Han M. Fibrosing alveolitis: prognostic implication of ground-glass attenuation at high-resolution CT. Radiology. 1992, 184, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller N, Staples CA, Miller RR, Vedal S, Thurlbeck WM, Ostrow DN. Disease activity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: CT and pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1987, 165, 731–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahin AA, Sabri YY, Mostafa HA, Sabry EY, Hamid MA, Gamal H, et al. Pulmonary function tests, high-resolution computerized tomography, α1-antitrypsin measurement, and early detection of pulmonary involvement in patients with systemic sclerosis. Rheumatol Int. 2001, 20, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terriff BA, Kwan SY, Chan-Yeung M, Müller N. Fibrosing alveolitis: chest radiography and CT as predictors of clinical and functional impairment at follow-up in 26 patients. Radiology. 1992, 184, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein D, Meziere G, Biderman P, Gepner A, Barre O. The comet-tail artifact: an ultrasound sign of alveolar-interstitial syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997, 156, 1640–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Targhetta R, Chavagneux R, Balmes P, Lemerre C, Mauboussin JM, Bourgeois JM, et al. Sonographic lung surface evaluation in pulmonary sarcoidosis: preliminary results. J Ultrasound Med. 1994, 13, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reissig A, Kroegel C. Transthoracic Sonography of Diffuse Parenchymal Lung Disease The Role of Comet Tail Artifacts. J Ultrasound Med. 2003, 22, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avouac J, Fransen J, Walker U, Riccieri V, Smith V, Muller C, et al. Preliminary criteria for the very early diagnosis of systemic sclerosis: results of a Delphi Consensus Study from EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research Group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011, 70, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrick JH, Bhalla M, Schabel SI, Silver RM. High resolution computed tomography in early scleroderma lung disease. J Rheumatol. 1991, 18, 1520–1528. [Google Scholar]

- Jambrik Z, Monti S, Coppola V, Agricola E, Mottola G, Miniati M, et al. Usefulness of ultrasound lung comets as a nonradiologic sign of extravascular lung water. Am J Cardiol. 2004, 93, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doveri M, Frassi F, Consensi A, Vesprini E, Gargani L, Tafuri M, et al. Ultrasound lung comets: new echographic sign of lung interstitial fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. Reumatismo. 2008, 60, 180–184. [Google Scholar]

- Picano E, Frassi F, Agricola E, Gligorova S, Gargani L, Mottola G. Ultrasound lung comets: a clinically useful sign of extravascular lung water. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2006, 19, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargani L, Romei C, Bruni C, Lepri G, El-Aoufy, Orlandi M, et al. Lung ultrasound B-lines in systemic sclerosis: cut-off values and methodological indications for interstitial lung disease screening. Rheumatology 2022, 61, SI56–SI64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tardella M, Di Carlo M, Carotti M et al. Ultrasound B-lines in the evaluation of interstitial lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis: cut-off point definition for the presence of significant pulmonary fibrosis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018, 97, e0566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacedonia D, Scioscia G, Giardinelli A, Quarato CMI, Sassani EV, Foschino Barbaro MP, et al. The Role of Transthoracic Ultrasound in the Study of Interstitial Lung Diseases: High-Resolution Computed Tomography Versus Ultrasound Patterns: Our Preliminary Experience. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021, 11, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Muller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging 1. Radiology. 2008, 246, 697–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussone G, Mouthon L. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis. Autoimmun Rev. 2011, 10, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greidinger EL, Flaherty KT, White B, Rosen A, Wigley FM, Wise RA. African-American race and antibodies to topoisomerase I are associated with increased severity of scleroderma lung disease. Chest. 1998, 114, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assasi S, Sharif R, Lasky RE, McNearney TA, Estrada-Y-Martin RM, Draeger H, et al. Predictors of interstitial lung disease in early systemic sclerosis: a prospective longitudinal study of the GENISOS cohort. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010, 12, R166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu W, Jordan S, Becker MO, Dobrota R, Maurer B, Fretheim H, et al. Prediction of progression of interstitial lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis: the SPAR model. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018, 77, 1326–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Goullec N, Duhamel A, Perez T, Hachulla AL, Sobanski V, Faivre JB, et al Predictors of lung function test severity and outcome in systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease . PLoS One.

- Landini N, Orlandi M, Bruni C, Carlesi E, Nardi C, et al. Computed tomography predictors of mortality or disease progression in systemic sclerosis – interstitial lung disease: a systemic review. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022, 8, 807982. [Google Scholar]

- Rotondo C, Urso L, Praino E, Cacciapaglia F, Corrado A, Cantatore FP, Iannone F. Thoracic lymphoadenopathy as possible predictor of the onset of interstitial lung disease associated to systemic sclerosis. J Scleroderma Relat Disord. 2020, 5, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann-Vold A, Maher TM, Philpot EE, Ashrafzadeh A, Barake R, Barsotti S, et al. The identification and management of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: evidence-based European consensus statements. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020, 2, e71–e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan AA, Makhlouf HA, et al. B-lines: Transthoracic chest ultrasound signs useful in assessment of interstitial lung diseases. Ann Thorac Med. 2014, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tardella M, Gutierrez M, Salaffi F, Carotti M, Ariani A, Bertolazzi C, et al. Ultrasound in the assessment of pulmonary fibrosis in connective tissue disorders: correlation with high-resolution computed tomography. J Rheumatol. 2012, 39, 1641–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).