Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: Electromagnetic and Electronic Metamaterials: A Brief Comparison

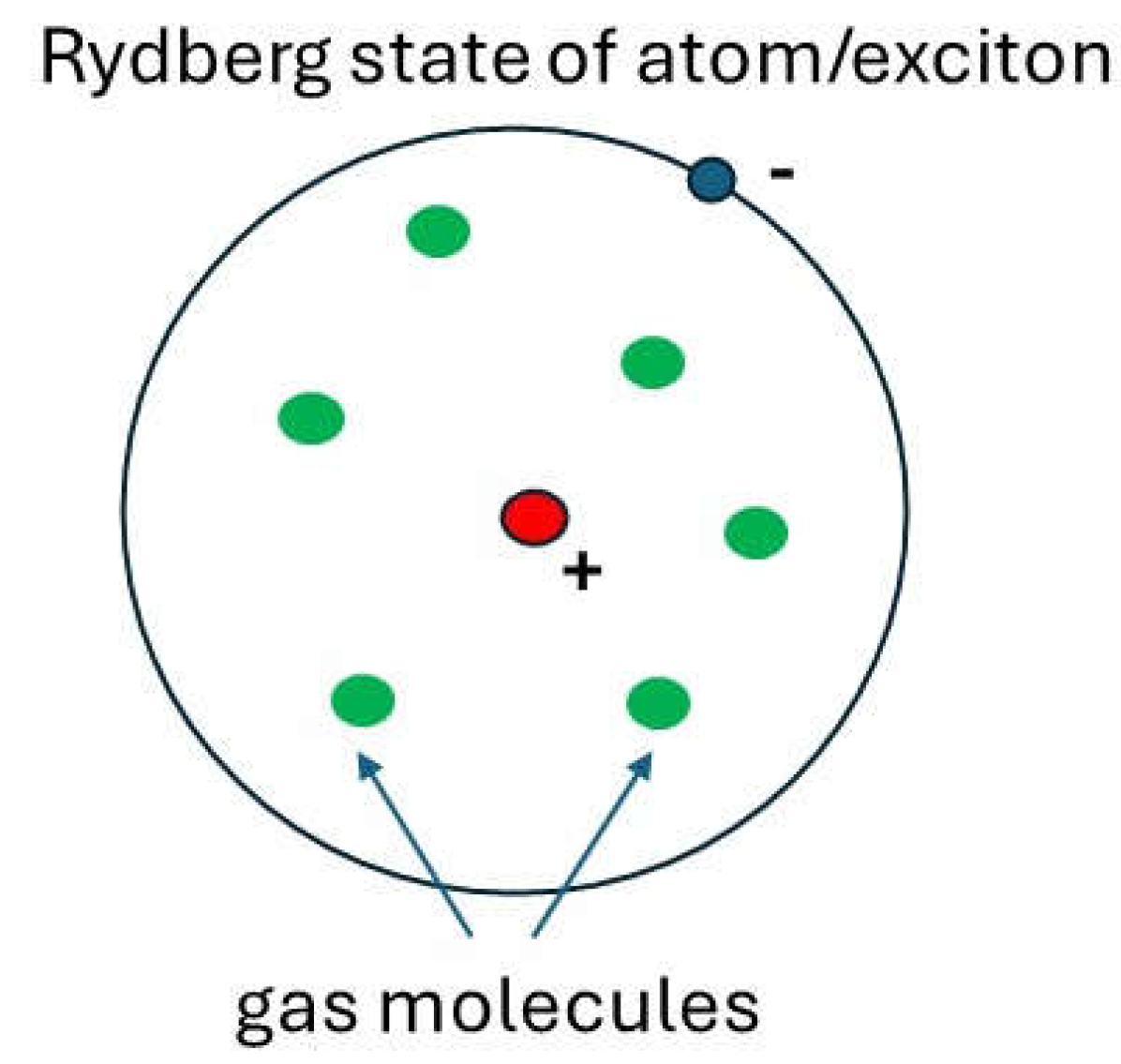

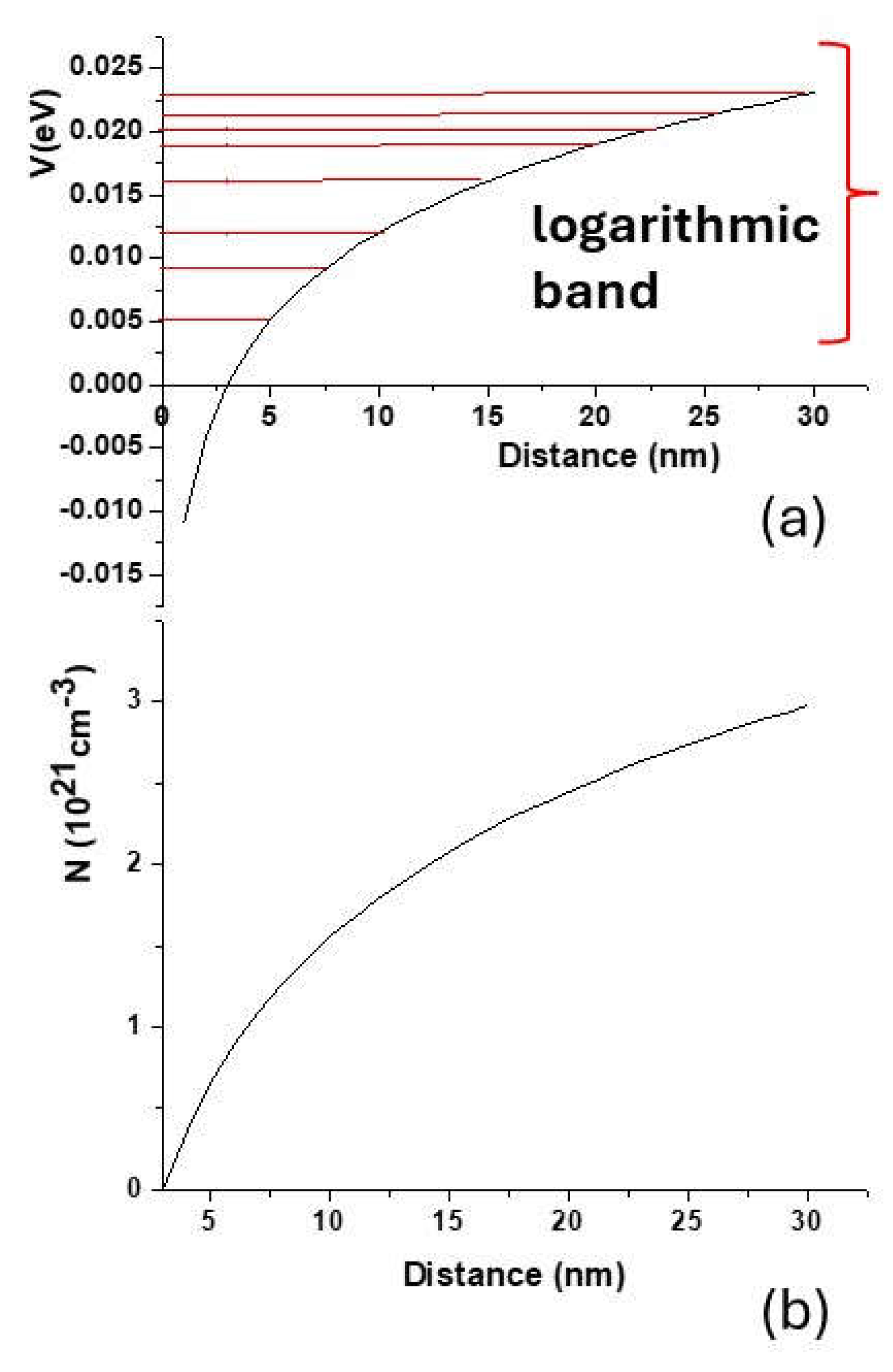

2. Materials and Methods: Fermi’s Quantum Refraction as an Efficient Tool of Nanometre-Scale Electronic Metamaterial Engineering

3. Results

3.1. Engineering a Universal Quantum Dot Using Fermi’s Quantum Refraction

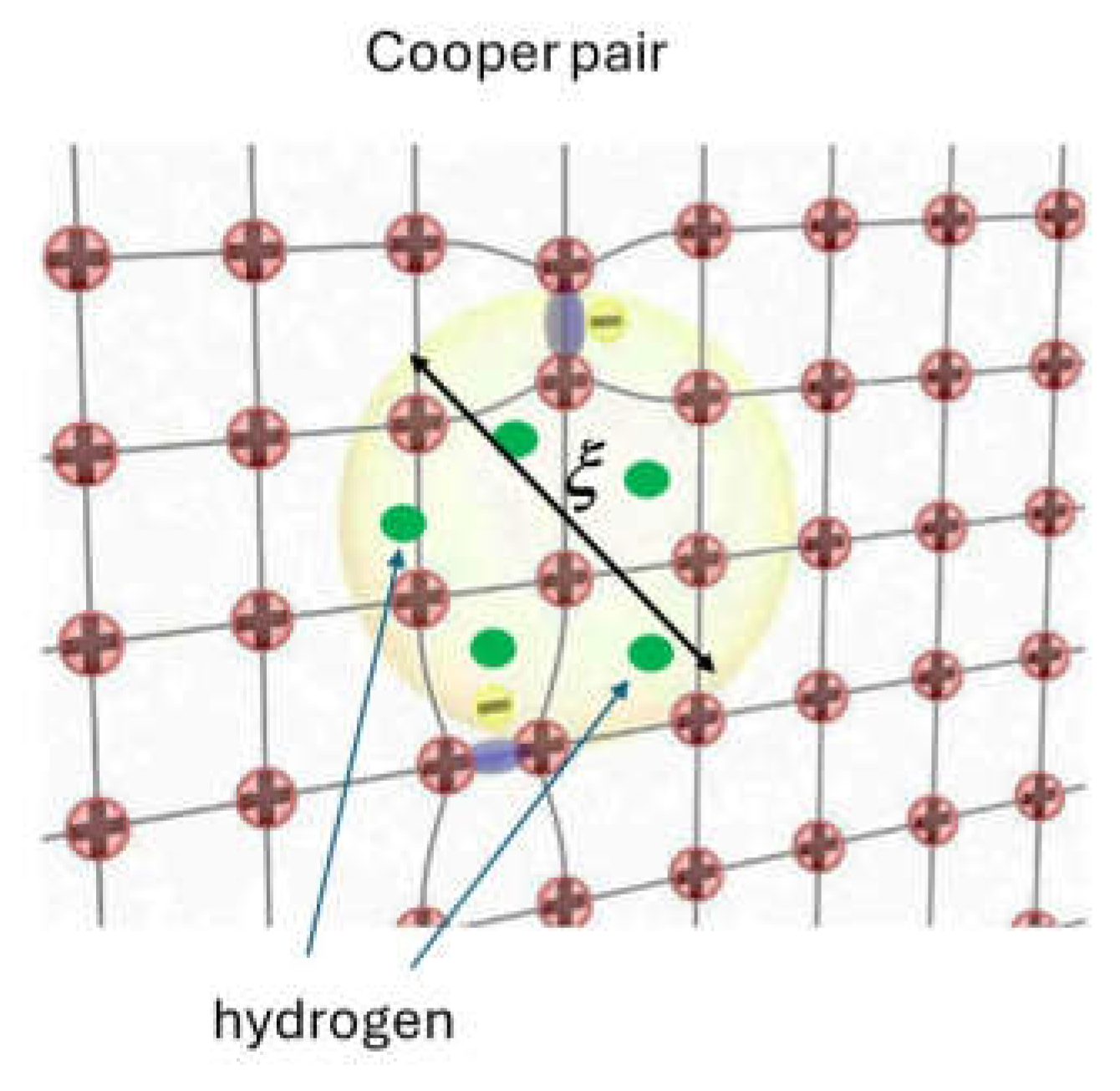

3.2. Application of Quantum Refraction to Metamaterial Superconductors

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ENZ | Epsilon near zero |

| MOND | Modified Newtonian dynamics |

| Tc | Critical temperature (of a superconductor) |

References

- Pendry, J.B.; Schurig, D.; Smith, D.R. Controlling electromagnetic fields. Science 2006, 312, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummer, S.A.; Christensen, J.; Alù, A. Controlling sound with acoustic metamaterials. Nature Reviews Materials 2016, 1, 16001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, W.; Han, T.; Zheng, X.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Fan, S.; Qiu, C.-W. Transforming heat transfer with thermal metamaterials and devices. Nature Reviews Materials 2021, 6, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragoman, D.; Dragoman, M. Metamaterials for ballistic electrons. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 101, 104316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolyaninov, I.I.; Smolyaninova, V.N. Metamaterial superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 094501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolyaninov, I.I.; Hung, Y.J.; Davis, C.C. Magnifying superlens in the visible frequency range. Science 2007, 315, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.C.W.; Gabor, N.M. Electron quantum metamaterials in van der Waals heterostructures. Nature Nanotechnology 2018, 13, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolyaninova, V.N.; Zander, K.; Gresock, T.; Jensen, C.; Prestigiacomo, J.C.; Osofsky, M.S.; Smolyaninov, I.I. Enhanced superconductivity in aluminum-based hyperbolic metamaterials. Scientific Reports 2015, 5, 15777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fermi, E. On the theory of collisions between atoms and electrically charged particles. Nuovo Cim. 1925, 2, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashkin, E.P. The energy spectrum and other properties of localized electron states in condensed media. Sov. Phys. JETP 1982, 55, 1076. [Google Scholar]

- Zavyalov, V.V.; Smolyaninov, I.I. Quantum refraction in gaseous H2, D2, Ne, and He for electrons levitating above the surface of crystalline hydrogen, deuterium, and neon. Sov. Phys. JETP 1988, 67, 171. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, R.W.; Morrison, M.A. Comment of the possibility of Ramsauer-Townsend minima in e-H2 and e-N2 scattering. Phys. Rev. A 1982, 26, 3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syty, P.; Pilat, M.P.; Sienkiewicz, J.E. Calculation of electron scattering lengths on Ar, Kr, Xe, Rn and Og atoms. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2024, 57, 175202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Cai, J.; Zheng, H.; Seewald, E.; Taniguchi, T.; Watanabe, K.; Yan, J.; Yankowitz, M.; Pasupathy, A.; Yao, W.; Xu, X. Dynamically tunable moiré exciton Rydberg states in a monolayer semiconductor on twisted bilayer graphene. Nature Materials 2024, 23, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofue, Y.; Rubin, V. Rotation curves of spiral galaxies. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 2001, 39, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M. A modification of Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis. The Astophysical Journal 1983, 270, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, N.; Matli, J.; Pham, T. Old quantization, angular momentum, and nonanalytic problems. 2020, arXiv:2009.01014. [quant-ph]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Zhu, A.; Lou, X.; Song, D.; Yang, R.; Shi, H.; Long, F. Universal quantum dot-based sandwich-like immunoassay strategy for rapid and ultrasensitive detection of small molecules using portable and reusable optofluidic nano-biosensing platform. Analytica Chimica Acta 2016, 905, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.C.; Kamionkowski, M. Dynamical and gravitational instability of oscillating-field dark energy and dark matter. Phys. Rev. D 2008, 78, 063010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolyaninov, I.I. Oscillating cosmological force modifies Newtonian dynamics. Galaxies 2020, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolyaninov, I.I. Metamaterial multiverse. Journal of Optics 2011, 13, 024004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirzhnits, D.A.; Maksimov, E.G.; Khomskii, D.I. The description of superconductivity in terms of dielectric response function. J. Low Temp. Phys. 1973, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engheta, N. Pursuing near-zero response. Science 2013, 340, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolyaninov, I.I.; Smolyaninova, V.N. Hyperbolic metamaterials. Solid State Electronics 2017, 136, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolyaninova, V.N.; Jensen, C.; Zimmerman, W.; Prestigiacomo, J.C.; Osofsky, M.S.; Kim, H.; Bassim, N.; Xing, Z.; Qazilbash, M.M.; Smolyaninov, I.I. Enhanced superconductivity in aluminum-based hyperbolic metamaterials. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 34140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, D.; Kuo, C.N.; Yang, T.W.; Chen, I.N.; Lue, C.S.; Wang, L.M. Two-dimensional superconductivity and magnetotransport from topological surface states in AuSn4 semimetal. Communications Materials 2020, 1, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Deng, Z.Y.; Chen, I.N.; Lin, C. W.; Wu, C.H.; Liu, E.P.; Chen, W.T.; Wang, L.M. Two-dimensional superconductivity with exotic magnetotransports in conventional superconductor BiIn2. Materials Today Physics 2024, 46, 101505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).