Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is the most prevalent sexually transmitted infection (STI) globally and contributor to a significant proportion of infection-related cancers, including oral squamous cell carcinomas (OSCCs). Persistent infection with oncogenic HPV strains is increasingly recognized as a critical cause of oral cancers, particularly in India. While HPV infections are often asymptomatic and transient, those that persist for year or more can lead to malignancies following integration into host cell genome and disrupting tumor-suppressor genes. HPV vaccination, including vaccines such as Cervarix, Gardasil or Gardasil-9, and the more recently introduced CERVAVAC in India, has significantly reduced the incidence of cervical and other HPV-related anogenital cancers. However, the potential of these vaccines in preventing HPV-linked OSCCs remains underexplored, especially in the Indian context, where the incidence of these cancers, particularly among younger populations, is on the rise. This review critically examines the role of HPV vaccination in preventing HPV-associated OSCCs. It explores the biological mechanisms by which HPV contributes to oral carcinogenesis, focusing on the most common HPV strains linked to these cancers. The review also assesses the effectiveness of existing HPV vaccines in preventing oral-HPV infections, drawing on the latest epidemiological and clinical studies. Despite promising evidence supporting the efficacy of HPV vaccines, challenges such as low vaccine uptake, limited public awareness, and socio-economic barriers hinder their widespread adoption in low-income countries including India. This review also discusses the early outcomes of vaccination programs on OSCC incidence and discusses strategies to enhance vaccine coverage, including targeted public health initiatives and policy interventions. By addressing these gaps, this review aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the potential impact of HPV vaccination in reducing the burden of HPV-associated oral cancers in India and offering insights for future research and public health strategies.

Keywords:

- Significance:

- HPV vaccine; the world’s first cancer vaccine developed by the University of Queensland in Australia by Professors Ian Frazer and Jian Zhou.

- HPV vaccination provides the greatest protection against HPV-derived cervical and oral cancer.

- HPV prophylactic vaccines are highly immunogenic, safe, and produce specific antibodies against the virus subtypes.

- ProphylacticHPV vaccination provide effective protection against most common oncogenic HPV infection and associated diseases in both men and women.

- Challenges in scaling-up HPV immunisation along-with screening and early detection particularly in developing countries may make the world cervical cancer-free in next one decade or two.

- Availability of therapeutic vaccine for treatment of already HPV infected diseases is essential.

1. Background

2. Epidemiology of Oral Cancer Prevalence in India

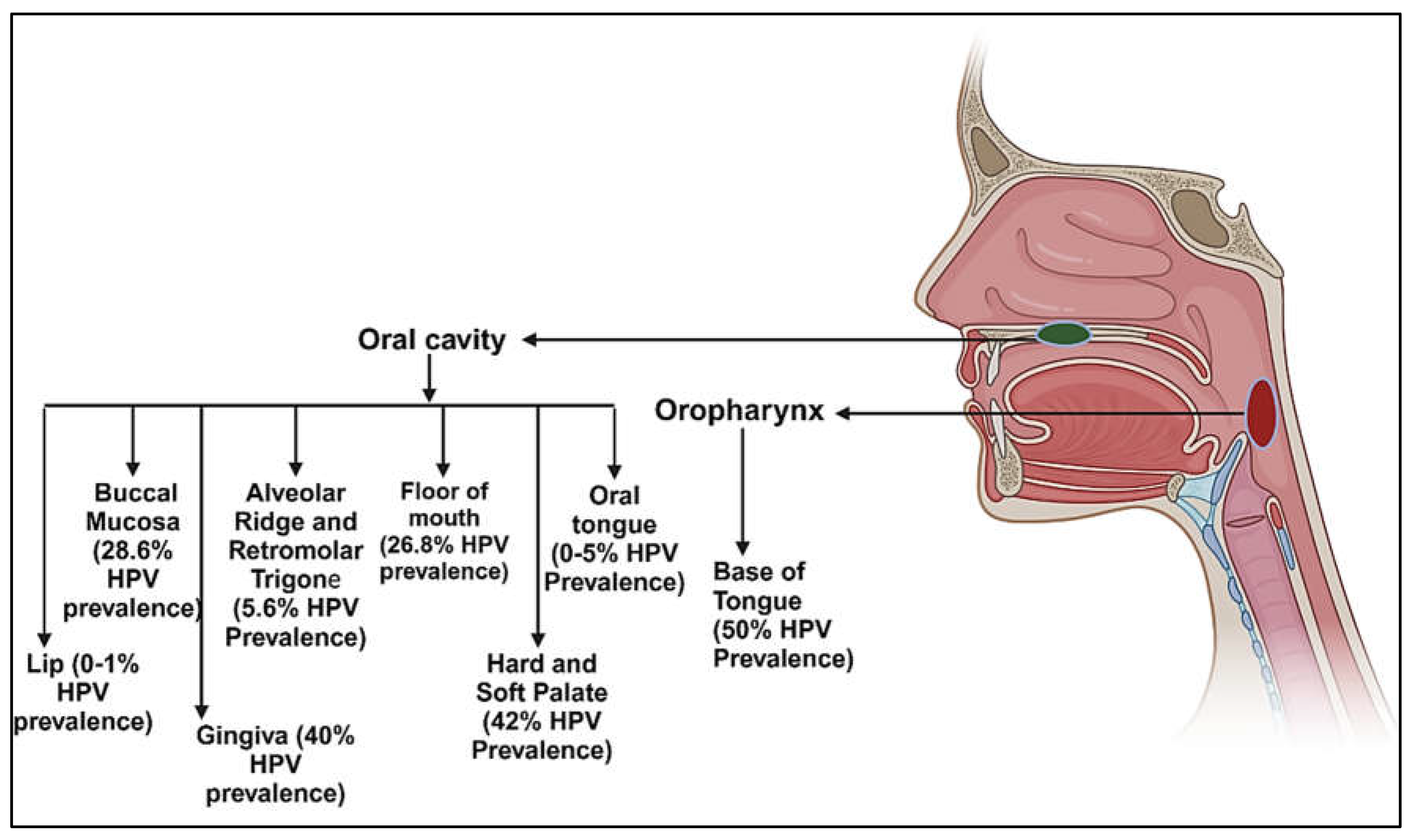

3. Prevalence of HPV in Various Anatomical Subsites of Oral Cavity

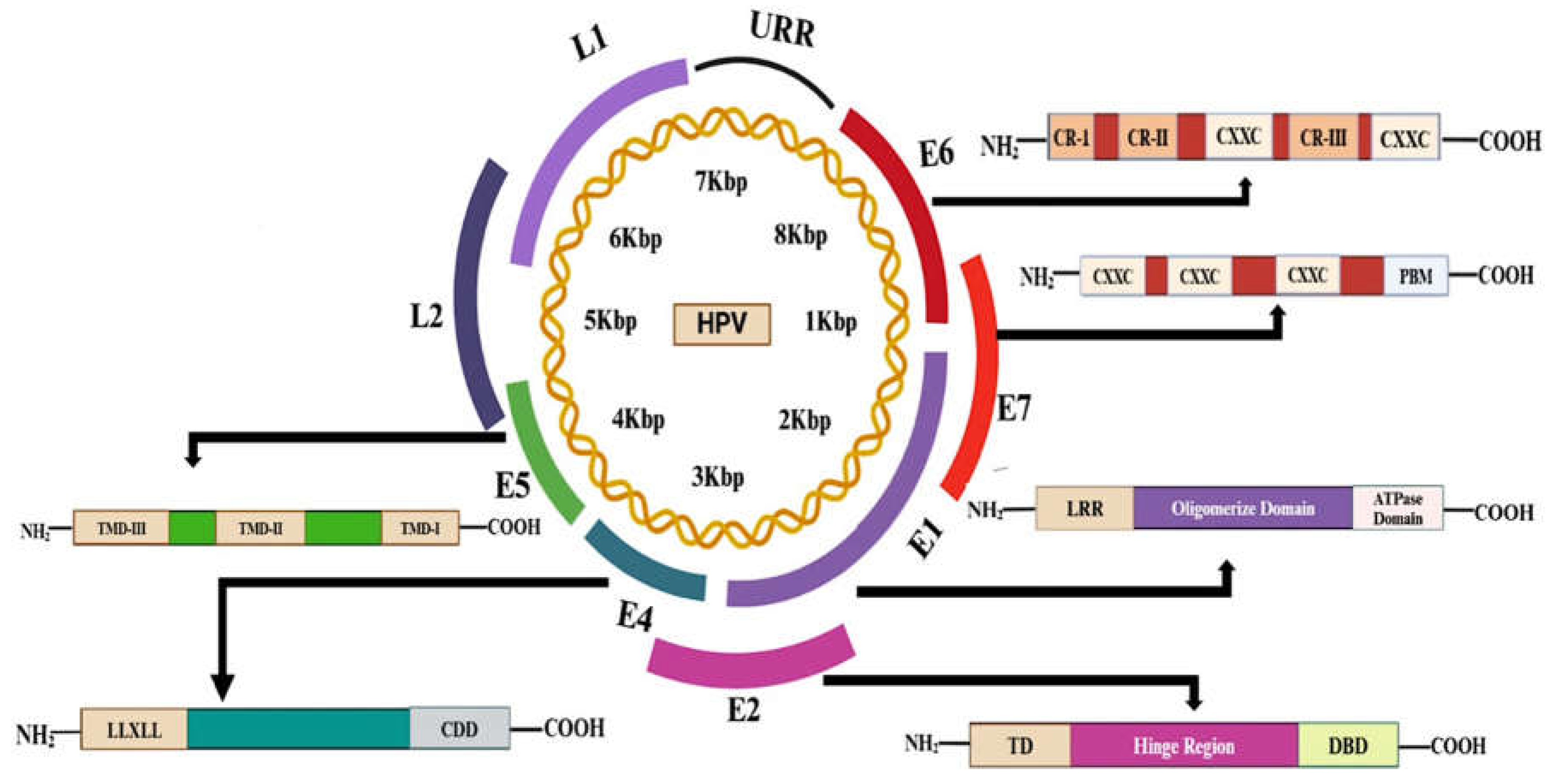

4. HPV Genomics: Structure and Function

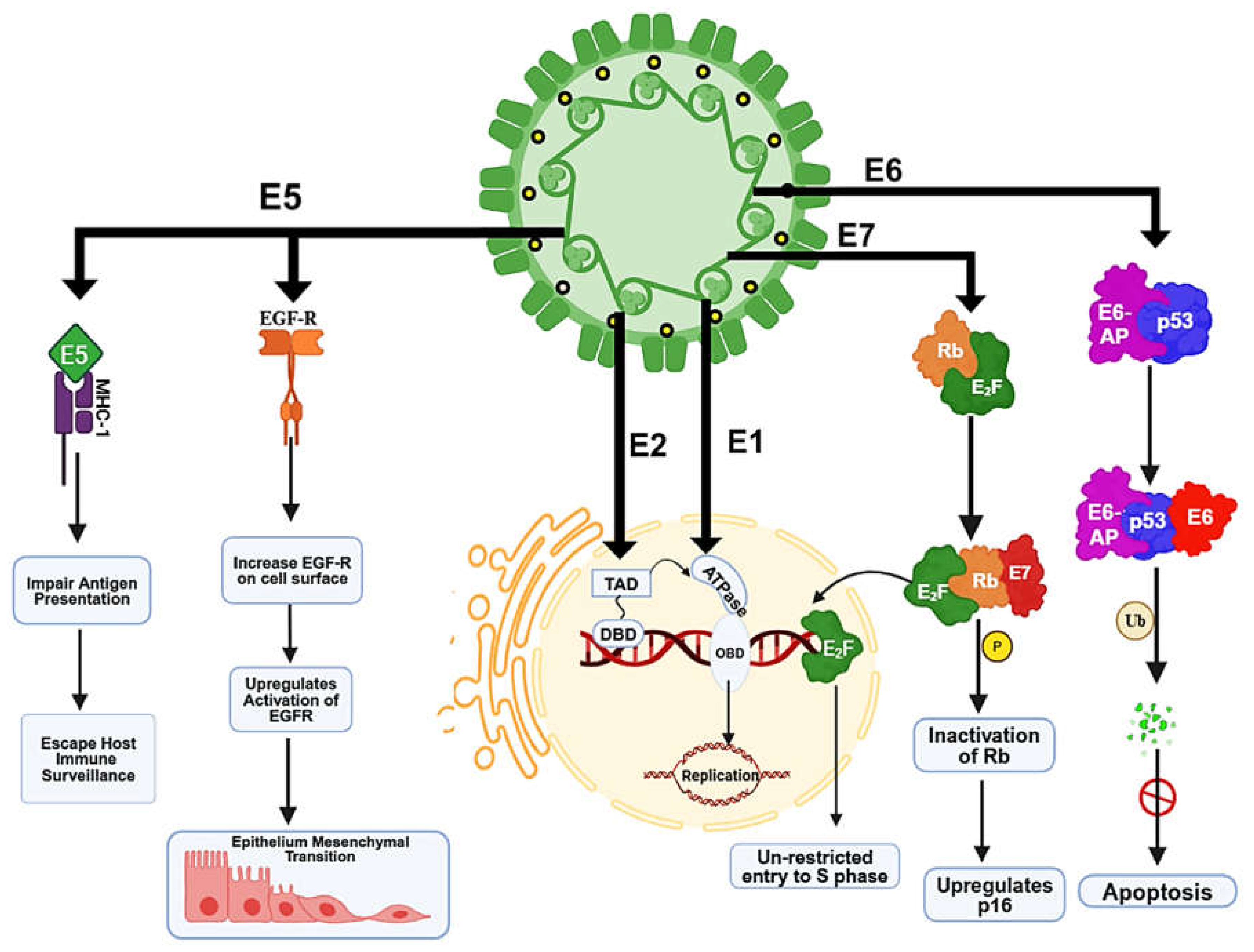

5. HPV-Induced Genomic Instability and Mechanism of Carcinogenesis

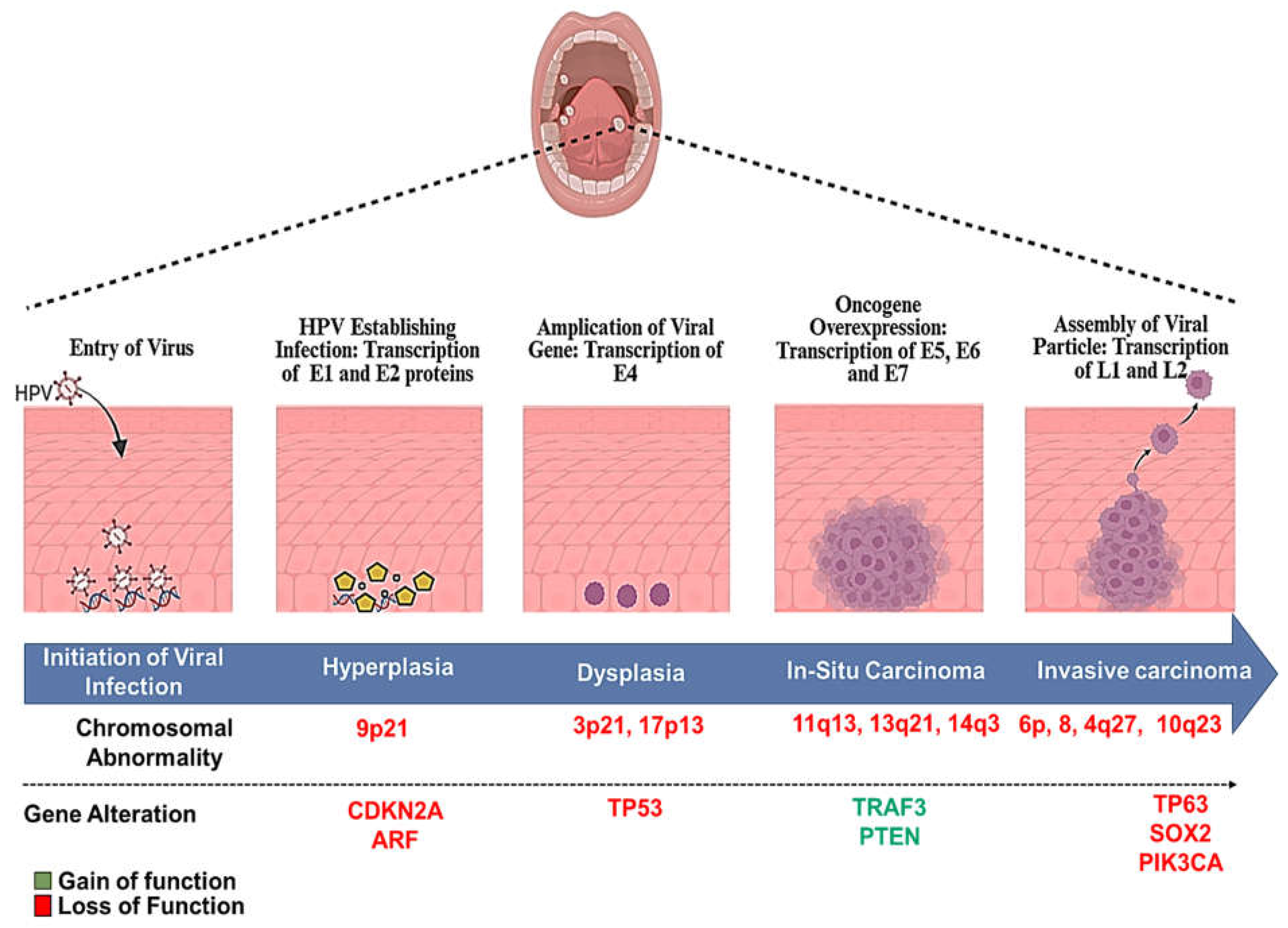

6. HPV-Induced Carcinogenesis in the Oral and Oropharyngeal Lesions

7. The Basis of Prophylactic HPV Vaccines

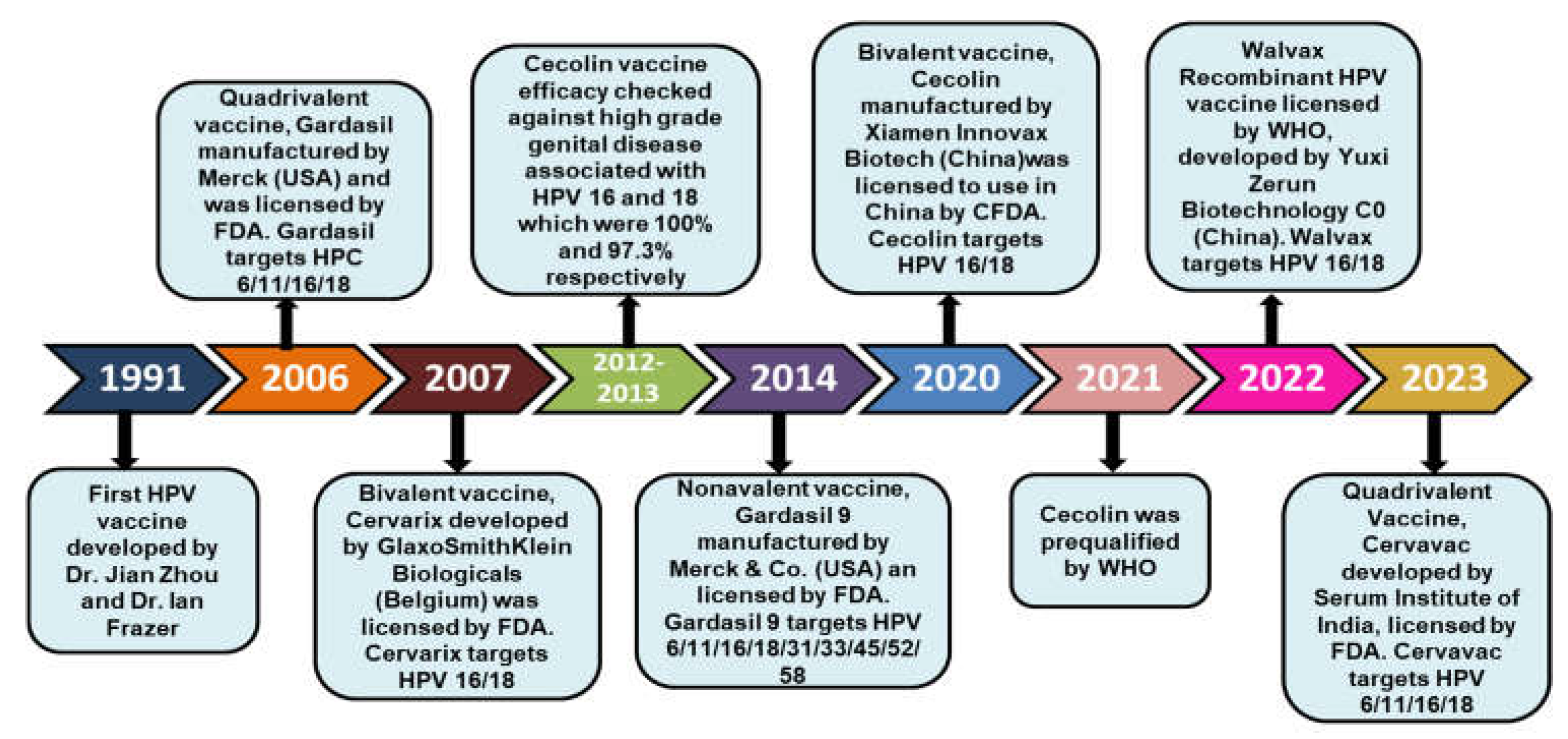

8. Historical Milestones of HPV Vaccination

| Vaccine name | Type of vaccine | Approval | Manufacturer | Type of target strain | Shelf Life | Formulation | Route of administration & Dose | Adjuvant | HPV targets | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervarix | Prophylactic | FDA | GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals (Belgium) 2007 |

Bivalent | 60 months | Liquid | Intramuscular; 2 or 3 doses, depending on age at initiation |

Aluminium hydroxide (500 μg); 3-O-desacyl-4’ monophosphoryl lipid A (AS04) (50 μg) |

HPV 16/18 |

[150] |

| Gardasil | Prophylactic | FDA | Merck (USA); 2006 |

Quadrivalent | 36 months | Liquid | Intramuscular; 2 or 3 doses, depending on age at initiation |

Amorphous aluminium hydroxyphosphate sulfate (225 μg) |

HPV 6/11/16/18 | [151] |

| Garadasil-9 | Prophylactic | FDA | Merck & Co (USA); 2014 |

Nonvalent | 36 months | Liquid | Intramuscular; 2 or 3 doses, depending on age at initiation |

Amorphous aluminium hydroxyphosphate sulfate (500 μg) |

HPV 6/11/16/18/31/33/45/52/58 | [152] |

| Cervavac | Prophylactic | FDA | Serum Institute of India (SII); 2022 | Quadrivalent | 36 months | Liquid | Intramuscular; 2 or 3 doses, depending on age at initiation |

Al+++ (1.25 mg) | HPV 6/11/16/18 |

[153] |

| Cecolin | Prophylactic | CFDA | Xiamen Innovax Biotech (China); 2020 |

Bivalent |

36 months | Liquid | Intramuscular; 2 or 3 doses, depending on age at initiation |

Aluminium hydroxide (208 μg) | HPV 16/18 |

[154] |

| WalrinVax | Prophylactic | CFDA | Yuxi Zerun Biotechnology Co (China); |

Bivalent | 24 months | Liquid |

Intramuscular; 2 or 3 doses, depending on age at initiation | Aluminium phosphate (225 μg) | HPV 16/18 |

[155] |

9. Global Impact of HPV Vaccination on the Prevention of Oral Cancers

10. Challenges in Implementing HPV Vaccination in India

11. Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harper DM, DeMars LR. HPV vaccines–a review of the first decade. Gynecologic oncology. 2017;146(1):196-204.

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [CrossRef]

- Tranby, E.P.; Heaton, L.J.; Tomar, S.L.; Kelly, A.L.; Fager, G.L.; Backley, M.; Frantsve-Hawley, J. Oral Cancer Prevalence, Mortality, and Costs in Medicaid and Commercial Insurance Claims Data. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prev. 2022, 31, 1849–1857. [CrossRef]

- Ray CS, Gupta PC. Oral cancer in India. Oral Diseases. 2024.

- Kumar, P.; Gupta, S.; Das, B.C. Saliva as a potential non-invasive liquid biopsy for early and easy diagnosis/prognosis of head and neck cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2023, 40, 101827. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.; Kumar, N. Worldwide incidence, mortality and time trends for cancer of the oesophagus. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2017, 26, 107–118. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Bharti, A.C.; Varghese, P.; Saluja, D.; Das, B.C. Differential expression and activation of NF-κB family proteins during oral carcinogenesis: Role of high risk human papillomavirus infection. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 119, 2840–2850. [CrossRef]

- Gupta S, Kumar P, kour H, Sharma N, Saluja D, Bharti A, et al. Selective participation of c-Jun with Fra-2/c-Fos promotes aggressive tumor phenotypes and poor prognosis in tongue cancer. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:16811. .

- Gupta, S.; Kumar, P.; Das, B.C. HPV: Molecular pathways and targets. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2018, 42, 161–174. [CrossRef]

- Gupta S, Kumar P, Das BC. Challenges and opportunities to making Indian women cervical cancer free. Indian Journal of Medical Research 2023;158(5&6):470-5.

- Das, B.C.; Hussain, S.; Nasare, V.; Bharadwaj, M. Prospects and prejudices of human papillomavirus vaccines in India. Vaccine 2008, 26, 2669–2679. [CrossRef]

- Anderer, S. WHO Approves Another HPV Vaccine for Single-Dose Use. JAMA 2024, 332, 1780. [CrossRef]

- Garland, S.M.; Hernandez-Avila, M.; Wheeler, C.M.; Perez, G.; Harper, D.M.; Leodolter, S.; Tang, G.W.; Ferris, D.G.; Steben, M.; Bryan, J.; et al. Quadrivalent Vaccine against Human Papillomavirus to Prevent Anogenital Diseases. New Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1928–1943. [CrossRef]

- Hildesheim A, Wacholder S, Catteau G, Struyf F, Dubin G, Herrero R, et al. Efficacy of the HPV-16/18 vaccine: final according to protocol results from the blinded phase of the randomized Costa Rica HPV-16/18 vaccine trial. Vaccine. 2014;32(39):5087-97.

- Williamson, A.-L. Recent Developments in Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccinology. Viruses 2023, 15, 1440. [CrossRef]

- Gultekin, M.; Ramirez, P.T.; Broutet, N.; Hutubessy, R. World Health Organization call for action to eliminate cervical cancer globally. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 426–427. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Gupta, S.; Das, A.M.; Das, B.C. Towards global elimination of cervical cancer in all groups of women. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, e237–E237. [CrossRef]

- Parkin, D.M.; Hämmerl, L.; Ferlay, J.; Kantelhardt, E.J. Cancer in Africa 2018: The role of infections. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 146, 2089–2103. [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.N.; Misra, J.S.; Srivastava, S.; Das, B.C.; Gupta, S. Cervical cancer screening in rural India: Status & current concepts. Indian J. Med Res. 2018, 148, 687–696. [CrossRef]

- Gupta S, Kumar P, Tyagi A, Sharma K, Kaur H, Das BC. Modern Approaches to Prevention and Control of Cancer of the Uterine Cervix in Women. Journal of the Indian Institute of Science. 2012;92(3):353-564.

- Bagan, J.; Sarrion, G.; Jimenez, Y. Oral cancer: Clinical features. Oral Oncol. 2010, 46, 414–417. [CrossRef]

- Warin, K.; Suebnukarn, S. Deep learning in oral cancer- a systematic review. BMC Oral Heal. 2024, 24, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Asthana, S.; Patil, R.S.; Labani, S. Tobacco-related cancers in India: A review of incidence reported from population-based cancer registries. Indian J. Med Paediatr. Oncol. 2016, 37, 152–157. [CrossRef]

- Borse, V.; Konwar, A.N.; Buragohain, P. Oral cancer diagnosis and perspectives in India. Sensors International 2020, 1, 100046–100046. [CrossRef]

- Gangane, N.; Chawla, S.; Anshu; Subodh, A.; Gupta, S.S.; Sharma, S.M. Reassessment of risk factors for oral cancer. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 2007, 8, 243–8.

- Madani, A.H.; Dikshit, M.; Bhaduri, D. Risk for oral cancer associated to smoking, smokeless and oral dip products. Indian J. Public Health 2012, 56, 57–60. [CrossRef]

- Hashibe, M.; Sankaranarayanan, R.; Thomas, G.; Kuruvilla, B.; Mathew, B.; Somanathan, T.; Parkin, D.M.; Zhang, Z. Body mass index, tobacco chewing, alcohol drinking and the risk of oral submucous fibrosis in Kerala, India. Cancer Causes Control. 2002, 13, 55–64. [CrossRef]

- Sturgis, E.M.; Wei, Q.; Spitz, M.R. Descriptive epidemiology and risk factors for head and neck cancer. Semin. Oncol. 2004, 31, 726–733. [CrossRef]

- Jalouli, J.; Ibrahim, S.O.; Mehrotra, R.; Jalouli, M.M.; Sapkota, D.; Larsson, P.-A.; Hirsch, J.-M. Prevalence of viral (HPV, EBV, HSV) infections in oral submucous fibrosis and oral cancer from India. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 2010, 130, 1306–1311. [CrossRef]

- Wong T, Wiesenfeld D. Oral cancer. Australian dental journal. 2018;63:S91-S9.

- Katirachi, S.K.; Grønlund, M.P.; Jakobsen, K.K.; Grønhøj, C.; von Buchwald, C. The Prevalence of HPV in Oral Cavity Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Viruses 2023, 15, 451. [CrossRef]

- Näsman A, Du J, Dalianis T. A global epidemic increase of an HPV-induced tonsil and tongue base cancer–potential benefit from a pan-gender use of HPV vaccine. Journal of internal medicine. 2020;287(2):134-52.

- Yete, S.; D’Souza, W.; Saranath, D. High-Risk Human Papillomavirus in Oral Cancer: Clinical Implications. Oncology 2018, 94, 133–141. [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, E.-M.; Fauquet, C.; Broker, T.R.; Bernard, H.-U.; zur Hausen, H. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology 2004, 324, 17–27. [CrossRef]

- Münger, K.; Baldwin, A.; Edwards, K.M.; Hayakawa, H.; Nguyen, C.L.; Owens, M.; Grace, M.; Huh, K. Mechanisms of Human Papillomavirus-Induced Oncogenesis. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 11451–11460. [CrossRef]

- Egawa, N.; Egawa, K.; Griffin, H.; Doorbar, J. Human Papillomaviruses; Epithelial Tropisms, and the Development of Neoplasia. Viruses 2015, 7, 3863–3890. [CrossRef]

- Pisani, T.; Cenci, M. Prevalence of Multiple High Risk Human Papilloma Virus (HR-HPV) Infections in Cervical Cancer Screening in Lazio Region, Italy. Cancer Diagn. Progn. 2024, 4, 42–45. [CrossRef]

- Galati, L.; Chiocca, S.; Duca, D.; Tagliabue, M.; Simoens, C.; Gheit, T.; Arbyn, M.; Tommasino, M. HPV and head and neck cancers: Towards early diagnosis and prevention. Tumour Virus Res. 2022, 14, 200245. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, S.; Wang, R. Therapeutic strategies of different HPV status in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 1104–1118. [CrossRef]

- Bzhalava, D.; Eklund, C.; Dillner, J. International standardization and classification of human papillomavirus types. Virology 2015, 476, 341–344. [CrossRef]

- de Villiers E-M. Cross-roads in the classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2013;445(1-2):2-10.

- Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. The Journal of pathology. 1999;189(1):12-9.

- Moscicki, A.-B.; Shi, B.; Huang, H.; Barnard, E.; Li, H. Cervical-Vaginal Microbiome and Associated Cytokine Profiles in a Prospective Study of HPV 16 Acquisition, Persistence, and Clearance. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Georges, D.; Man, I.; Baussano, I.; Clifford, G.M. Causal attribution of human papillomavirus genotypes to invasive cervical cancer worldwide: a systematic analysis of the global literature. Lancet 2024, 404, 435–444. [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, S. The IARC commitment to cancer prevention: the example of papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Tumor Prev. Genet. III 2005, 277–297. [CrossRef]

- Castro-Muñoz, L.J.; Manzo-Merino, J.; Muñoz-Bello, J.O.; Olmedo-Nieva, L.; Cedro-Tanda, A.; Alfaro-Ruiz, L.A.; Hidalgo-Miranda, A.; Madrid-Marina, V.; Lizano, M. The Human Papillomavirus (HPV) E1 protein regulates the expression of cellular genes involved in immune response. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Enemark, E.J.; Joshua-Tor, L. Mechanism of DNA translocation in a replicative hexameric helicase. Nature 2006, 442, 270–275. [CrossRef]

- Baedyananda F, Sasivimolrattana T, Chaiwongkot A, Varadarajan S, Bhattarakosol P. Role of HPV16 E1 in cervical carcinogenesis. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2022;12:955847.

- Sakakibara, N.; Chen, D.; McBride, A.A. Papillomaviruses Use Recombination-Dependent Replication to Vegetatively Amplify Their Genomes in Differentiated Cells. PLOS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003321. [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.V. The human papillomavirus replication cycle, and its links to cancer progression: a comprehensive review. Clin. Sci. 2017, 131, 2201–2221. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, G.; Biswas-Fiss, E.E.; Biswas, S.B. Sequence-Dependent Interaction of the Human Papillomavirus E2 Protein with the DNA Elements on Its DNA Replication Origin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6555. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, R.; Das, S.S.; Biswal, S.S.; Nath, A.; Das, D.; Basu, A.; Malik, S.; Kumar, L.; Kar, S.; Singh, S.K.; et al. Mechanistic role of HPV-associated early proteins in cervical cancer: Molecular pathways and targeted therapeutic strategies. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2022, 174, 103675. [CrossRef]

- Kajitani, N.; Satsuka, A.; Yoshida, S.; Sakai, H. HPV18 E1^E4 is assembled into aggresome-like compartment and involved in sequestration of viral oncoproteins. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 62921. [CrossRef]

- Basukala, O.; Banks, L. The Not-So-Good, the Bad and the Ugly: HPV E5, E6 and E7 Oncoproteins in the Orchestration of Carcinogenesis. Viruses 2021, 13, 1892. [CrossRef]

- Venuti, A.; Paolini, F. HPV Detection Methods in Head and Neck Cancer. Head Neck Pathol. 2012, 6, 63–74. [CrossRef]

- Araujo-Arcos, L.E.; Montaño, S.; Bello-Rios, C.; Garibay-Cerdenares, O.L.; Leyva-Vázquez, M.A.; Illades-Aguiar, B. Molecular insights into the interaction of HPV-16 E6 variants against MAGI-1 PDZ1 domain. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Elrefaey, S.; Massaro, M.; Chiocca, S.; Chiesa, F.; Ansarin, M. HPV in oropharyngeal cancer: the basics to know in clinical practice. Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica. 2014, 34, 299–309.

- Roman A, Munger K. The papillomavirus E7 proteins. Virology. 2013;445(1-2):138-68.

- Bello-Rios, C.; Montaño, S.; Garibay-Cerdenares, O.L.; Araujo-Arcos, L.E.; Leyva-Vázquez, M.A.; Illades-Aguiar, B. Modeling and Molecular Dynamics of the 3D Structure of the HPV16 E7 Protein and Its Variants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1400. [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.V. Human Papillomavirus: Gene Expression, Regulation and Prospects For Novel Diagnostic Methods and Antiviral Therapies. Futur. Microbiol. 2010, 5, 1493–1506. [CrossRef]

- Bharti, A.C.; Shukla, S.; Mahata, S.; Hedau, S.; Das, B.C. Human papillomavirus and control of cervical cancer in India. Expert Rev. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 5, 329–346. [CrossRef]

- Buck, C.B.; Day, P.M.; Trus, B.L. The papillomavirus major capsid protein L1. Virology 2013, 445, 169–174. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C.W.; Mirabello, L. Human papillomavirus genomics: Understanding carcinogenicity. Tumour Virus Res. 2023, 15, 200258. [CrossRef]

- Raff, A.B.; Woodham, A.W.; Raff, L.M.; Skeate, J.G.; Yan, L.; Da Silva, D.M.; Schelhaas, M.; Kast, W.M. The Evolving Field of Human Papillomavirus Receptor Research: a Review of Binding and Entry. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 6062–6072. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Roden, R.B. Virus-like particles for the prevention of human papillomavirus-associated malignancies. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2013, 12, 129–141. [CrossRef]

- de Sanjose, S.; Quint, W.G.V.; Alemany, L.; Geraets, D.T.; Klaustermeier, J.E.; Lloveras, B.; Tous, S.; Felix, A.; Bravo, L.E.; Shin, H.-R.; et al. Human papillomavirus genotype attribution in invasive cervical cancer: a retrospective cross-sectional worldwide study. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 1048–1056. [CrossRef]

- Pett M, Coleman N. Integration of high-risk human papillomavirus: a key event in cervical carcinogenesis? The Journal of Pathology: A Journal of the Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 2007;212(4):356-67.

- Zhang, L.; Yang, B.; Zhang, A.; Zhou, A.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, L.; Cao, H.; Wang, J.; Zheng, W. Association between human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 variants with subsequent persistent infection and recurrence of cervical high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion after conization. J. Med Virol. 2016, 88, 1982–1988. [CrossRef]

- Warburton, A.; Redmond, C.J.; Dooley, K.E.; Fu, H.; Gillison, M.L.; Akagi, K.; Symer, D.E.; Aladjem, M.I.; McBride, A.A. HPV integration hijacks and multimerizes a cellular enhancer to generate a viral-cellular super-enhancer that drives high viral oncogene expression. PLOS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007179. [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Gaykalova, D.A.; Guo, T.; Favorov, A.V.; Fertig, E.J.; Tamayo, P.; Callejas-Valera, J.L.; Allevato, M.; Gilardi, M.; Santos, J.; et al. HPV E2, E4, E5 drive alternative carcinogenic pathways in HPV positive cancers. Oncogene 2020, 39, 6327–6339. [CrossRef]

- Schinke, H.; Shi, E.; Lin, Z.; Quadt, T.; Kranz, G.; Zhou, J.; Wang, H.; Hess, J.; Heuer, S.; Belka, C.; et al. A transcriptomic map of EGFR-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition identifies prognostic and therapeutic targets for head and neck cancer. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Rampias, T.; Sasaki, C.; Psyrri, A. Molecular mechanisms of HPV induced carcinogenesis in head and neck. Oral Oncol. 2014, 50, 356–363. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Hisamatsu, K.; Suzui, N.; Hara, A.; Tomita, H.; Miyazaki, T. A Review of HPV-Related Head and Neck Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 241. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Dickie, J.; Sutavani, R.V.; Pointer, C.; Thomas, G.J.; Savelyeva, N. Targeting Head and Neck Cancer by Vaccination. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 830. [CrossRef]

- Longworth, M.S.; Laimins, L.A. Pathogenesis of Human Papillomaviruses in Differentiating Epithelia. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2004, 68, 362–372. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Banks, L. Human papillomavirus (HPV) E6 interactions with Bak are conserved amongst E6 proteins from high and low risk HPV types. J. Gen. Virol. 1999, 80, 1513–1517. [CrossRef]

- A Thompson, D.; Belinsky, G.; Chang, T.H.-T.; Jones, D.L.; Schlegel, R.; Münger, K. The human papillomavirus-16 E6 oncoprotein decreases the vigilance of mitotic checkpoints. Oncogene 1997, 15, 3025–3035. [CrossRef]

- Duensing, S.; Münger, K. The human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins independently induce numerical and structural chromosome instability. Cancer research 2002, 62, 7075–82.

- Incassati, A.; Patel, D.; McCance, D.J. Induction of tetraploidy through loss of p53 and upregulation of Plk1 by human papillomavirus type-16 E6. Oncogene 2005, 25, 2444–2451. [CrossRef]

- D’souza, G.; Clemens, G.; Strickler, H.D.; Wiley, D.J.; Troy, T.; Struijk, L.; Gillison, M.; Fakhry, C. Long-term Persistence of Oral HPV Over 7 Years of Follow-up. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2020, 4, pkaa047. [CrossRef]

- Tokuzen, N.; Nakashiro, K.-I.; Tojo, S.; Goda, H.; Kuribayashi, N.; Uchida, D. Human papillomavirus-16 infection and p16 expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 22, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Lechner, M.; Liu, J.; Masterson, L.; Fenton, T.R. HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer: epidemiology, molecular biology and clinical management. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 306–327. [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhang, H.; Shen, J.; Chen, J.; Hong, J.; Xu, Y.; Qian, C. Prophylactic and Therapeutic HPV Vaccines: Current Scenario and Perspectives. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 909223. [CrossRef]

- Stanley M, Wheeler C. HPV VLP vaccines–alternative dosage schedules and immunization in immunosuppressed subjects. Primary End-points for Prophylactic HPV Vaccine Trials: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2014.

- Ashique, S.; Hussain, A.; Fatima, N.; Altamimi, M.A. HPV pathogenesis, various types of vaccines, safety concern, prophylactic and therapeutic applications to control cervical cancer, and future perspective. VirusDisease 2023, 34, 172–190. [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, Z.; Aria, H.; Ghaedrahmati, F.; Bakhtiari, T.; Azizi, M.; Bastan, R.; Hosseini, R.; Eskandari, N. An Update on Human Papilloma Virus Vaccines: History, Types, Protection, and Efficacy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 805695. [CrossRef]

- Schiller, J.T.; Müller, M. Next generation prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccines. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, e217–e225. [CrossRef]

- Yadav R, Zhai L, Tumban E. Virus-like particle-based L2 vaccines against HPVs: where are we today? Viruses. 2019;12(1):18.

- Garbuglia, A.R.; Lapa, D.; Sias, C.; Capobianchi, M.R.; Del Porto, P. The Use of Both Therapeutic and Prophylactic Vaccines in the Therapy of Papillomavirus Disease. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 188. [CrossRef]

- Sankaranarayanan, R.; Prabhu, P.R.; Pawlita, M.; Gheit, T.; Bhatla, N.; Muwonge, R.; Nene, B.M.; Esmy, P.O.; Joshi, S.; Poli, U.R.R.; et al. Immunogenicity and HPV infection after one, two, and three doses of quadrivalent HPV vaccine in girls in India: a multicentre prospective cohort study. The lancet oncology 2015, 17, 67–77. [CrossRef]

- McNeil C. Who invented the VLP cervical cancer vaccines? Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2006;98(7):433-.

- Akhatova, A.; Chan, C.K.; Azizan, A.; Aimagambetova, G. The Efficacy of Therapeutic DNA Vaccines Expressing the Human Papillomavirus E6 and E7 Oncoproteins for Treatment of Cervical Cancer: Systematic Review. Vaccines 2021, 10, 53. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Gong, Y.; Kang, W.; Liu, X.; Liang, X. The Role and Development of Peptide Vaccines in Cervical Cancer Treatment. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2024, 30, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Huang, H.; Yu, C.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Xie, L. Current status and future directions for the development of human papillomavirus vaccines. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1362770. [CrossRef]

- Ault, K.A. Human papillomavirus vaccines and the potential for cross-protection between related HPV types. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 107, S31–S33. [CrossRef]

- Paavonen J, Naud P, Salmerón J, Wheeler CM, Chow S-N, Apter D, et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by oncogenic HPV types (PATRICIA): final analysis of a double-blind, randomised study in young women. The Lancet. 2009;374(9686):301-14.

- Drolet, M.; Bénard, .; Boily, M.-C.; Ali, H.; Baandrup, L.; Bauer, H.; Beddows, S.; Brisson, J.; Brotherton, J.M.L.; Cummings, T.; et al. Population-level impact and herd effects following human papillomavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet infectious diseases 2015, 15, 565–580. [CrossRef]

- Drolet, M.; Bénard, É.; Pérez, N.; Brisson, M.; HPV Vaccination Impact Study Group. Population-level impact and herd effects following the introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination programmes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2019, 394, 497–509. [CrossRef]

- Ndon, S.; Singh, A.; Ha, P.K.; Aswani, J.; Chan, J.Y.-K.; Xu, M.J. Human Papillomavirus-Associated Oropharyngeal Cancer: Global Epidemiology and Public Policy Implications. Cancers 2023, 15, 4080. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y. Involvement of Human Papillomaviruses in Cervical Cancer. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2896. [CrossRef]

- Didierlaurent, A.M.; Morel, S.; Lockman, L.; Giannini, S.L.; Bisteau, M.; Carlsen, H.; Kielland, A.; Vosters, O.; Vanderheyde, N.; Schiavetti, F.; et al. AS04, an Aluminum Salt- and TLR4 Agonist-Based Adjuvant System, Induces a Transient Localized Innate Immune Response Leading to Enhanced Adaptive Immunity. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 6186–6197. [CrossRef]

- McKeage K, Romanowski B. AS04-adjuvanted human papillomavirus (HPV) types 16 and 18 vaccine (cervarix®) a review of its use in the prevention of premalignant cervical lesions and cervical cancer causally related to certain oncogenic HPV types. Drugs. 2011;71:465-88.

- Monie A, Hung C-F, Roden R, Wu TC. Cervarix™: a vaccine for the prevention of HPV 16, 18-associated cervical cancer. Biologics: Targets and Therapy. 2008;2(1):107-13.

- Herrero R, Wacholder S, Rodríguez AC, Solomon D, González P, Kreimer AR, et al. Prevention of persistent human papillomavirus infection by an HPV16/18 vaccine: a community-based randomized clinical trial in Guanacaste, Costa Rica. Cancer discovery. 2011;1(5):408-19.

- Mehanna, H.; Bryant, T.S.; Babrah, J.; Louie, K.; Bryant, J.L.; Spruce, R.J.; Batis, N.; Olaleye, O.; Jones, J.; Struijk, L.; et al. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Effectiveness and Potential Herd Immunity for Reducing Oncogenic Oropharyngeal HPV-16 Prevalence in the United Kingdom: A Cross-sectional Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 69, 1296–1302. [CrossRef]

- Harper, D.M.; Franco, E.L.; Wheeler, C.M.; Moscicki, A.-B.; Romanowski, B.; Roteli-Martins, C.M.; Jenkins, D.; Schuind, A.; Clemens, S.A.C.; Dubin, G. Sustained efficacy up to 4·5 years of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine against human papillomavirus types 16 and 18: follow-up from a randomised control trial. Lancet 2006, 367, 1247–1255. [CrossRef]

- Kreimer AR, González P, Katki HA, Porras C, Schiffman M, Rodriguez AC, et al. Efficacy of a bivalent HPV 16/18 vaccine against anal HPV 16/18 infection among young women: a nested analysis within the Costa Rica Vaccine Trial. The lancet oncology. 2011;12(9):862-70.

- Porras C, Tsang SH, Herrero R, Guillén D, Darragh TM, Stoler MH, et al. Efficacy of the bivalent HPV vaccine against HPV 16/18-associated precancer: long-term follow-up results from the Costa Rica Vaccine Trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2020;21(12):1643-52.

- Lang Kuhs KA, Gonzalez P, Rodriguez AC, van Doorn L-J, Schiffman M, Struijk L, et al. Reduced prevalence of vulvar HPV16/18 infection among women who received the HPV16/18 bivalent vaccine: a nested analysis within the Costa Rica Vaccine Trial. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2014;210(12):1890-9.

- Cuschieri, K.; Palmer, T.; Graham, C.; Cameron, R.; Roy, K. The changing nature of HPV associated with high grade cervical lesions in vaccinated populations, a retrospective study of over 1700 cases in Scotland. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 129, 1134–1141. [CrossRef]

- Markowitz LE. HPv vaccines—prophylactic, not therapeutic. Jama. 2007;298(7):805-6.

- McCormack PL. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, 18) recombinant vaccine (Gardasil®): a review of its use in the prevention of premalignant anogenital lesions, cervical and anal cancers, and genital warts. Drugs. 2014;74(11):1253-83.

- Pinto, L.A.; Kemp, T.J.; Torres, B.N.; Isaacs-Soriano, K.; Ingles, D.; Abrahamsen, M.; Pan, Y.; Lazcano-Ponce, E.; Salmeron, J.; Giuliano, A.R. Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Induces HPV-Specific Antibodies in the Oral Cavity: Results From the Mid-Adult Male Vaccine Trial. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 214, 1276–1283. [CrossRef]

- Hirth, J.M.; Chang, M.; Resto, V.A.; Guo, F.; Berenson, A.B. Prevalence of oral human papillomavirus by vaccination status among young adults (18–30 years old). Vaccine 2017, 35, 3446–3451. [CrossRef]

- Joura, E.A.; Giuliano, A.R.; Iversen, O.-E.; Bouchard, C.; Mao, C.; Mehlsen, J.; Moreira, E.D.; Ngan, Y.; Petersen, L.K.; Lazcano-Ponce, E.; et al. A 9-Valent HPV Vaccine against Infection and Intraepithelial Neoplasia in Women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 711–723. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Du, J. Human Papillomavirus Vaccines: An Updated Review. Vaccines 2020, 8, 391. [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, A.R.; Joura, E.A.; Garland, S.M.; Huh, W.K.; Iversen, O.-E.; Kjaer, S.K.; Ferenczy, A.; Kurman, R.J.; Ronnett, B.M.; Stoler, M.H.; et al. Nine-valent HPV vaccine efficacy against related diseases and definitive therapy: comparison with historic placebo population. Gynecologic oncology 2019, 154, 110–117. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Tumban, E. Gardasil-9: A global survey of projected efficacy. Antivir. Res. 2016, 130, 101–109. [CrossRef]

- Huh WK, Joura EA, Giuliano AR, Iversen O-E, de Andrade RP, Ault KA, et al. Final efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety analyses of a nine-valent human papillomavirus vaccine in women aged 16–26 years: a randomised, double-blind trial. The Lancet. 2017;390(10108):2143-59.

- Song, D.; Liu, P.; Wu, D.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Knowledge and Attitudes towards Human Papillomavirus Vaccination (HPV) among Healthcare Providers Involved in the Governmental Free HPV Vaccination Program in Shenzhen, Southern China. Vaccines 2023, 11, 997. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.-H.; Wu, T.; Hu, Y.-M.; Wei, L.-H.; Li, M.-Q.; Huang, W.-J.; Chen, W.; Huang, S.-J.; Pan, Q.-J.; Zhang, X.; et al. Efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of an Escherichia coli-produced Human Papillomavirus (16 and 18) L1 virus-like-particle vaccine: end-of-study analysis of a phase 3, double-blind, randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2022, 22, 1756–1768. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.-H.; Liu, Z.-Z.; Cui, S.-T.; Chu, Z.-X.; Jiang, Y.-J.; Xu, J.-J.; Hu, Q.-H.; Shang, H. High Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Acceptability and Cost-Effectiveness of the Chinese 2-Valent Vaccine Among Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Cross-Sectional Study in Shenyang, China. Front. Med. 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Sun, L.; Yao, X.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Y. Progress in Vaccination of Prophylactic Human Papillomavirus Vaccine. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1434. [CrossRef]

- Hu Y-M, Bi Z-F, Zheng Y, Zhang L, Zheng F-Z, Chu K, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of an Escherichia coli-produced human papillomavirus (types 6/11/16/18/31/33/45/52/58) L1 virus-like-particle vaccine: a phase 2 double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Science Bulletin. 2023;68(20):2448-55.

- Qiao, Y.-L.; Wu, T.; Li, R.-C.; Hu, Y.-M.; Wei, L.-H.; Li, C.-G.; Chen, W.; Huang, S.-J.; Zhao, F.-H.; Li, M.-Q.; et al. Efficacy, Safety, and Immunogenicity of an Escherichia coli-Produced Bivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: An Interim Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 112, 145–153. [CrossRef]

- Zaman, K.; E Schuind, A.; Adjei, S.; Antony, K.; Aponte, J.J.; Buabeng, P.B.; Qadri, F.; Kemp, T.J.; Hossain, L.; A Pinto, L.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of Innovax bivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in girls 9–14 years of age: Interim analysis from a phase 3 clinical trial. Vaccine 2024, 42, 2290–2298. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, G.-H.; Huang, W.-J.; Chu, K.; Zhang, L.; Bi, Z.-F.; Zhu, K.-X.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, T.-Q.; Zhang, M.-L.; Liu, S.; et al. Head-to-head immunogenicity comparison of an Escherichia coli-produced 9-valent human papillomavirus vaccine and Gardasil 9 in women aged 18–26 years in China: a randomised blinded clinical trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 1313–1322. [CrossRef]

- Chu K, Bi Z-F, Huang W-J, Li Y-F, Zhang L, Yang C-L, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an Escherichia coli-produced 9-valent human papillomavirus L1 virus-like particle vaccine (types 6/11/16/18/31/33/45/52/58) in healthy adults: an open-label, dose-escalation phase 1 clinical trial. The Lancet Regional Health–Western Pacific. 2023;34.

- Sharma H, Parekh S, Pujari P, Shewale S, Desai S, Bhatla N, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a new quadrivalent HPV vaccine in girls and boys aged 9–14 years versus an established quadrivalent HPV vaccine in women aged 15–26 years in India: a randomised, active-controlled, multicentre, phase 2/3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2023;24(12):1321-33.

- Basu P, Malvi SG, Joshi S, Bhatla N, Muwonge R, Lucas E, et al. Vaccine efficacy against persistent human papillomavirus (HPV) 16/18 infection at 10 years after one, two, and three doses of quadrivalent HPV vaccine in girls in India: a multicentre, prospective, cohort study. The Lancet Oncology. 2021;22(11):1518-29.

- Joshi, S.; Anantharaman, D.; Muwonge, R.; Bhatla, N.; Panicker, G.; Butt, J.; Poli, U.R.R.; Malvi, S.G.; Esmy, P.O.; Lucas, E.; et al. Evaluation of immune response to single dose of quadrivalent HPV vaccine at 10-year post-vaccination. Vaccine 2022, 41, 236–245. [CrossRef]

- Barnabas, R.V.; Brown, E.R.; Onono, M.A.; Bukusi, E.A.; Njoroge, B.; Winer, R.L.; Galloway, D.A.; Pinder, L.F.; Donnell, D.; Wakhungu, I.; et al. Efficacy of Single-Dose Human Papillomavirus Vaccination among Young African Women. NEJM Évid. 2022, 1. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Shi L-W, Li K, Huang L-R, Li J-B, Dong Y-L, et al. Comparison of the safety and persistence of immunogenicity of bivalent HPV16/18 vaccine in healthy 9–14-year-old and 18–26-year-old Chinese females: A randomized, double-blind, non-inferiority clinical trial. Vaccine. 2023;41(48):7212-9.

- Morand GB, Cardona I, Cruz SBSC, Mlynarek AM, Hier MP, Alaoui-Jamali MA, et al. Therapeutic vaccines for HPV-associated oropharyngeal and cervical cancer: the next de-intensification strategy? International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23(15):8395.

- Gheit, T. Mucosal and Cutaneous Human Papillomavirus Infections and Cancer Biology. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 355. [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, A.K.; Graubard, B.I.; Broutian, T.; Pickard, R.K.L.; Tong, Z.-Y.; Xiao, W.; Kahle, L.; Gillison, M.L. Effect of Prophylactic Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination on Oral HPV Infections Among Young Adults in the United States. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 262–267. [CrossRef]

- Katz, J. The impact of HPV vaccination on the prevalence of oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) in a hospital-based population: A cross-sectional study of patient’s registry. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2020, 50, 47–51. [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.; Osorio, J.C.; Fernández, A.; Méndez, F.; Alarcón, L.; Arturo, G.; Herrero, R.; Bravo, L.E. Effect of vaccination against oral HPV-16 infection in high school students in the city of Cali, Colombia. Papillomavirus Res. 2019, 7, 112–117. [CrossRef]

- Herrero, R.; Quint, W.; Hildesheim, A.; Gonzalez, P.; Struijk, L.; Katki, H.A.; Porras, C.; Schiffman, M.; Rodriguez, A.C.; Solomon, D.; et al. Reduced Prevalence of Oral Human Papillomavirus (HPV) 4 Years after Bivalent HPV Vaccination in a Randomized Clinical Trial in Costa Rica. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e68329. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.J.; Jakobsen, K.K.; Jensen, J.S.; Grønhøj, C.; Von Buchwald, C. The Effect of Prophylactic HPV Vaccines on Oral and Oropharyngeal HPV Infection—A Systematic Review. Viruses 2021, 13, 1339. [CrossRef]

- Bhatla, N.; Muwonge, R.; Malvi, S.G.; Joshi, S.; Poli, U.R.R.; Lucas, E.; Esmy, P.O.; Verma, Y.; Shah, A.; Zomawia, E.; et al. Impact of age at vaccination and cervical HPV infection status on binding and neutralizing antibody titers at 10 years after receiving single or higher doses of quadrivalent HPV vaccine. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2023, 19, 2289242. [CrossRef]

- Krokidi, E.; Rao, A.P.; Ambrosino, E.; Thomas, P.P.M. The impact of health education interventions on HPV vaccination uptake, awareness, and acceptance among people under 30 years old in India: a literature review with systematic search. Front. Reprod. Heal. 2023, 5, 1151179. [CrossRef]

- Sankaranarayanan R, Basu P, Kaur P, Bhaskar R, Singh GB, Denzongpa P, et al. Current status of human papillomavirus vaccination in India's cervical cancer prevention efforts. The Lancet Oncology. 2019;20(11):e637-e44.

- Mehrotra, R.; Yadav, K. Cervical Cancer: Formulation and Implementation of Govt of India Guidelines for Screening and Management. Indian J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 20, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- E Graham, J.; Mishra, A. Global challenges of implementing human papillomavirus vaccines. Int. J. Equity Heal. 2011, 10, 27–27. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Agarwal, P.; Gupta, N. A comprehensive narrative review of challenges and facilitators in the implementation of various HPV vaccination program worldwide. Cancer Med. 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.N.; Niazi, F.; Nandi, D.; Taneja, N. Gender-Neutral HPV Vaccine in India; Requisite for a Healthy Community: A Review. Cancer Control. 2024, 31. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, R.-Y.; Goyal, H.; Xu, H.-G. Gender-neutral HPV vaccination in Africa. Lancet Glob. Heal. 2019, 7, e563–E563. [CrossRef]

- https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/cervarix.

- https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/gardasil.

- https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/gardasil-9.

- https://cervavac.com/.

- https://extranet.who.int/prequal/vaccines/p/cecolinr.

- https://extranet.who.int/prequal/vaccines/p/walrinvaxr.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).