Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. SP and NK-1R in Glioma

3. SP Is Involved in Many Types of Signaling in Glioma

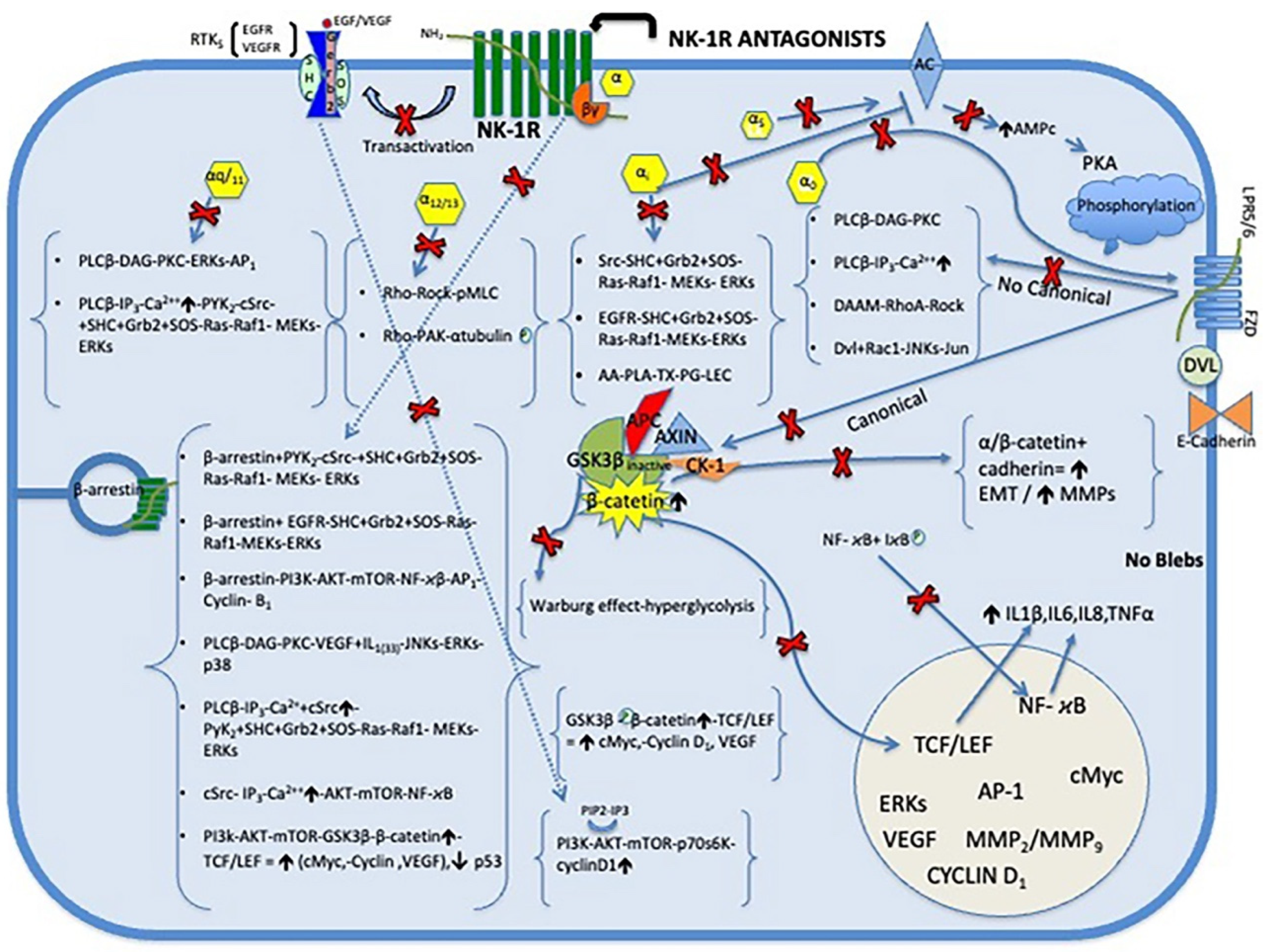

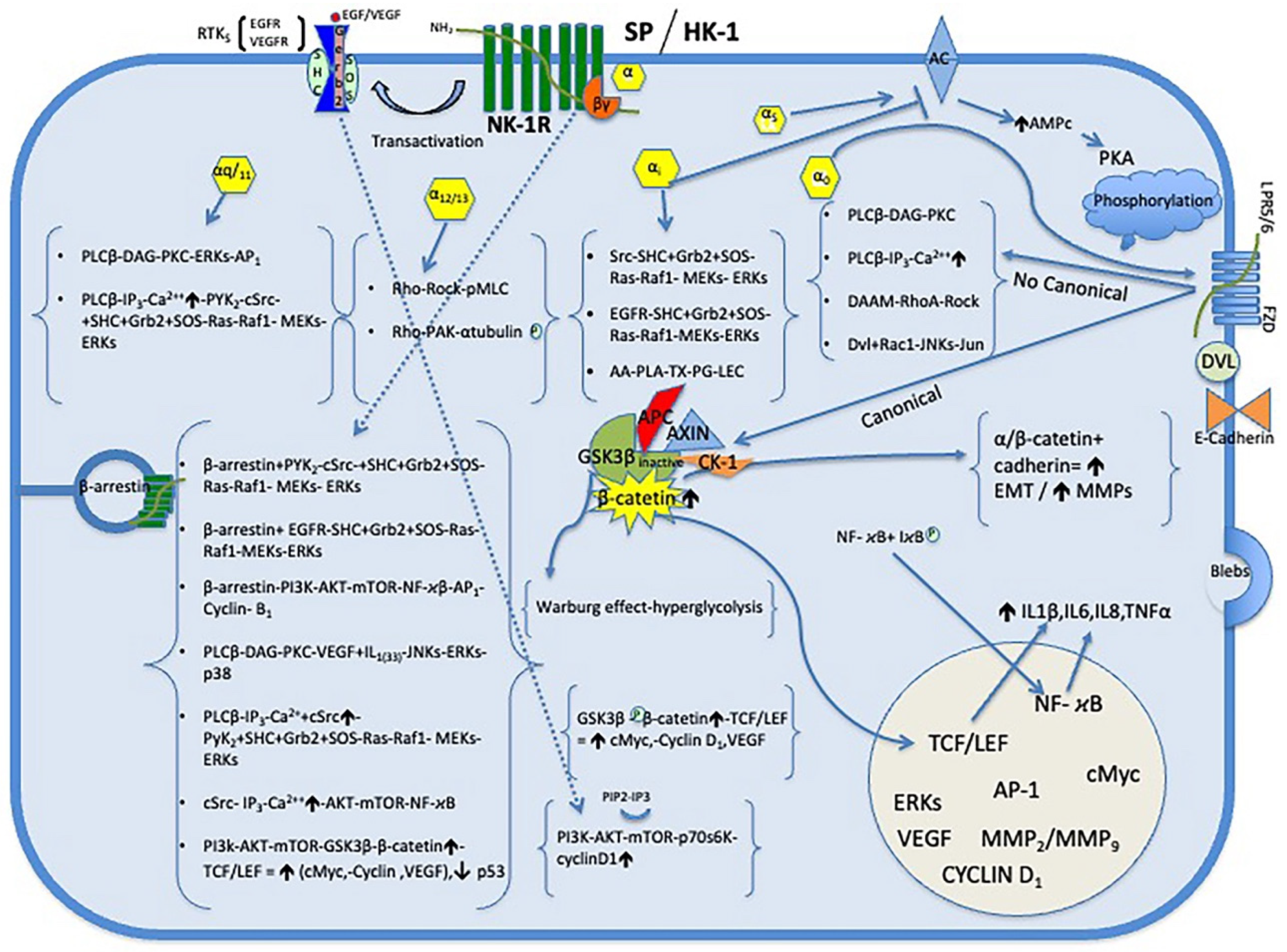

4. Role of SP and NK-1R in Mitogenesis and Antiapoptotic Effect in Glioma Cells (Figure 1)

5. Warburg Effect

6. SP/HK-1 and NK-1R in Glioma Angiogenesis

7. SP and NK-1R in Inflammation and Microenvironment of Glioma (Figure 1)

8. SP/HK-1 and NK-1R in Migration and Invasion of Glioma Cells (Figure 1)

8.1. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT)

8.2. Blebbing on Glioma Cell Membranes

8.3. The Extracelular Matrix (ECM)

9. NK-1R Antagonists

10. NK-1R Antagonists in Glioma Therapy (Figure 2)

10.1. Brain Penetrant

10.2. Antitumor Action of NK-1R Antagonist in Glioma

10.3. NK-1R Antagonists Inhibit Mitogenesis and Induce Apoptosis in Glioma Cells

10.4. NK-1R Antagonists Antiangiogenic Effects

10.5. NK-1R Antagonists Antimetastatic Effects in Glioma

10.6. NK-1R Antagonists Anti-Inflammatory

10.7. Combination of RT Plus NK-1R Antagonist

10.10. Clinical Experience with the Drug Aprepitant, an NK-1R Antagonist

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, SM.; Reifenberger, G.; Soffietti, R.; von Deimling, A.; Ellison, D.W. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 2021, 23, 1231-12. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab106. [CrossRef]

- Johung, T.B.; Monje, M. Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: new pathophysiological insights and emerging therapeutic targets. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 15, 88-97.doi: 10.2174/1570159x14666160509123229. [CrossRef]

- Damodharan, S.; Lara-Velazquez, M.; Williamsen, B.C.; Helgager, J.; Dey, M. Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: molecular landscape, evolving treatment strategies and emerging clinical trials. J. Pers. Med. 2022,12,840. doi: 10.3390/jpm12050840. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C.; Woodford, S.; Valle, D. Diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas in pediatric patients: management updates. Egypt J Neurosurg. 2023, 38, 64. doi: 10.3390/jpm12050840. [CrossRef]

- Hennig, IM.; Laissue, JA.; Horisberger, U.; Reubi, JC. Substance-P receptors in human primary neoplasms: tumoral and vascular localization. Int. J. Cancer. 1995, 61, 786-92.doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910610608. [CrossRef]

- Cordier, D.; Forrer, F.; Kneifel, S.; Sailer, M.; Mariani, L.; Mäcke, H.; Müller-Brand, J.; Merlo, A. Neoadjuvant targeting of glioblastoma multiforme with radiolabeled DOTAGA-substance P results from a phase I study. J. Neurooncol. 2010, 100, 129-36. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0153-5. [CrossRef]

- Mehboob, R.; Kurdi, M.; Baeesa, S.; Fawzy Halawa, T.; Tanvir, I.; Maghrabi, Y.; Hakamy, S.; Saeedi, R.; Moshref, R.; Nasief, H.; Hassan, A.; Waseem, H.; Rasool, S.; Bahakeem, B.; Faizo, E.; Katib, Y.; Bamaga, A.; Aldardeir, N. Immunolocalization of neurokinin 1 receptor in WHO grade 4 astrocytomas, oral squamous cell and urothelial carcinoma. Folia Neuropathol. 2022, 60, 165-176. doi: 10.5114/fn.2022.116469. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Coveñas, R. Glioma and Neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists: a new approach in glioma therapy. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2019a, 19, 92-100. doi: 10.2174/1871520618666180420165401. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Coveñas, R. The neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist aprepitant: an intelligent bullet against cancer?. Cancers. 2020, 12, 2682. doi: 10.3390/cancers12092682. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.F.; Argüelles, S.; Rosso, M.; Medina, R.; Coveñas, R.; Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M. The Neurokinin-1 Receptor Is Essential for the Viability of Human Glioma Cells: A Possible Target for Treating Glioblastoma. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 6291504.doi: 10.1155/2022/6291504. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Rosso M.; Coveñas, R. A new frontier in the treatment of cancer: NK-1 receptor antagonists. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 504-516.doi: 10.2174/092986710790416308. [CrossRef]

- Pennefather, J.N.; Lecci, A.; Candenas, M.L.; Patak, E.; Pinto, F.M.; Maggi, C.A. Tachykinins and tachykinin receptors: a growing family. Life Sci. 2004, 74, 1445-63. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.039. [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.M.; Leeman, S.E.; Niall, H.D. Amino-acid sequence of substance P. Nat. New. Biol. 1971, 232, 86-7.doi: 10.1038/newbio232086a0. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Coveñas, R.; Kramer, M. The involvement of the substance P/neurokinin 1 receptor system in viral infection: focus on the gp120 fusion protein and homologous dipeptide domains. Acta Virol. 2019b, 63, 253-260. doi: 10.1038/newbio232086a0. [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.; Paige, C.J. Hemokinin-1 has Substance P-like function in U-251 MG astrocytoma cells: a pharmacological and functional study. J. Neuroimmunol. 2005, 164, 48-56. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.03.016. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Coveñas, R. Involvement of substance P and NK-1 receptor in human pathology. Amino Acids. 2014; 46, 1727–50. doi: 10.1007/s00726-014-1736-9. [CrossRef]

- Castro, T.A.; Cohen, M.C.; Rameshwar, P. The expression of neurokinin-1 and preprotachykinin-1 in breast cancer cells depends on the relative degree of invasive and metastatic potential. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 2005, 22, 621-8. doi: 10.1007/s10585-006-9001-6. [CrossRef]

- Davoodian, M.; Boroumand, N.; Mehrabi, Bahar, M.; Jafarian, A.H.; Asadi, M.; Hashemy S.I. Evaluation of serum level of substance P and tissue distribution of NK-1 receptor in breast cancer. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 1285-1293. doi: 10.1007/s11033-019-04599-9. [CrossRef]

- Quartara, L.; Maggi, C.A.; The tachykinin receptor. Part II: distribution and pathophysiological roles. Neuropeptides. 1998, 32, 1-49. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4179(98)90015-4. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Rosso, M.; Coveñas, R. Neurokinin-1 Receptor. In Encyclopedia of Signaling Molecules, 2nd ed.; Sangdun Choi Eds.; Publisher: Springer Nature Suwon, Korea, 2018; pp 3437-3445. doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-67199-4. [CrossRef]

- DeFea, K.A.; Vaughn, Z.D.; O'Bryan, E.M. Nishijima, D.; Déry, O.; Bunnett, N.W. The proliferative and antiapoptotic effects of substance P are facilitated by formation of a beta-arrestin-dependent scaffolding complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000, 97, 11086-91doi: 10.1073/pnas.190276697. [CrossRef]

- Fong, T.M.; Anderson, S.A.; Yu, H.; Huang, R.R.; Strader, C.D. Differential activation of intracellular effector by two isoforms of human neurokinin-1 receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1992, 41, 24–30.

- Douglas, S.D.; Leeman, S.E. Neurokinin-1 receptor: functional significance in the immune system in reference to selected infections and inflammation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1217, 83–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05826.x. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Leeman, S.E.; Slack, B.E.; Hauser, G.; Saltsman, W.S.; Krause, J.E.; Blusztajn, J.K.; Boyd, N.D. A substance P (neurokinin-1) receptor mutant carboxyl-terminally truncated to resemble a naturally occurring receptor isoform displays enhanced responsiveness and resistance to desensitization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S. A. 1997, 94, 9475-80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9475. [CrossRef]

- Cordier, D.; Gerber, A.; Kluba, C.; Bauman, A.; Hutter, G.; Mindt, T.L.; Mariani, L. Expression of different neurokinin-1 receptor (NK1R) isoforms in glioblastoma multiforme: potential implications for targeted therapy. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2014, 29, 221-6. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2013.1588. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X.; Li, X.F.; Yuan, G.Q.; Hu, H. Song, X.Y.; Li, J.Y.; Miao, X.K.; Zhou, T.X.; Yang, W.L.; Zhang, X.W.; Mou, L.Y.; Wang, R. β-Arrestin 1 has an essential role in neurokinin-1 receptor-mediated glioblastoma cell proliferation and G2/M phase transition. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 8933-8947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.770420. [CrossRef]

- Ogo, H.; Kuroyanagi, N.; Inoue, A.; Nishio, H.; Hirai, Y.; Akiyama, M.; DiMaggio, D.A.; Krause, J.E.; Nakata, Y. Human astrocytoma cells (U-87 MG) exhibit a specific substance P-binding site with the characteristics of an NK-1 receptor. J. Neurochem. 1996, 67, 1813-1820. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67051813. x. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Rosso, M.; Perez, A.; Coveñas, R.; Rosso, R.; Zamarriego, C.; Piruat, J.I. The NK1 receptor is involved in the antitumoral action of L-733,060 and the mitogenic action of substance P on neuroblastoma and glioma cell lines. Neuropeptides. 2005, 39, 427-32. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2005.03.004. [CrossRef]

- Akazawa, T.; Kwatra, S.G.; Goldsmith, L.E.; Richardson, M.D.; Cox, E.A.; Sampson, J.H.; Kwatra, M.M. A constitutively active form of neurokinin 1 receptor and neurokinin 1 receptor-mediated apoptosis in glioblastomas. J. Neurochem. 2009, 109, 1079-86.doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06032.x. [CrossRef]

- Mou, L.; Kang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Song, H.; Wang, R. Neurokinin-1 receptor directly mediates glioma cell migration by up-regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) and membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP). J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 306-18. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.389783. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Rosso, M. The NK-1 receptor antagonist aprepitant as a broad-spectrum antitumor drug. Invest. New. Drugs. 2010, 28, 187-193. doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9218-8. [CrossRef]

- Palma, C.; Manzini, S. Substance P induces secretion of immunomodulatory cytokines by human astrocytoma cells. J. Neuroimmunol. 1998, 81, 127-37. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00167-7. [CrossRef]

- Palma, C.; Nardelli, F.; Manzini, S.; Maggi, C.A. Substance P activates responses correlated with tumour growth in human glioma cell lines bearing tachykinin NK1 receptors. Br. J. Cancer. 1999, 79, 236-43. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690039. [CrossRef]

- Gitter, B.D.; Bruns, R.F.; Howbert, J.J.; Waters, D.C.; Threlkeld, P.G.; Cox, L.M.; Nixon, J.A.; Lobb, K.L.; Mason, N.R.; Stengel, P.W. Pharmacological characterization of LY303870: a novel, potent and selective nonpeptide substance P (neurokinin-1) receptor antagonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995, 275, 737-44.

- Johnson, C.L.; Johnson, C.G. Characterization of receptors for substance P in human astrocytoma cells: radioligand binding and inositol phosphate formation. J. Neurochem. 1992, 58, 471-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09745.x. [CrossRef]

- Fowler, C.J.; Brännström, G. Substance P enhances forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP production in human UC11MG astrocytoma cells. Methods Find. Exp. Clin. Pharmacol. 1994, 16, 21-8.

- Friess, H.; Zhu, Z.; Liard, V.; Shi, X.; Shrikhande, S.V.; Wang, L.; Lieb, K.; Korc, M.; Palma, C.; Zimmermann, A.; Reubi, J.C.; Büchler, M.W. Neurokinin-1 receptor expression and its potential effects on tumor growth in human pancreatic cancer. Lab. Invest. 2003, 83, 731-42.doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000067499. 57309.f6. [CrossRef]

- Isorna, I.; González-Moles, M.A.; Muñoz, M.; Esteban, F. Substance P and Neurokinin-1 Receptor System in Thyroid Cancer: Potential Targets for New Molecular Therapies. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6409. doi: 10.3390/jcm12196409. [CrossRef]

- Lotz, M.; Vaughan, J.H.; Carson, D.A. Effect of neuropeptides on production of inflammatory cytokines by human monocytes. Science. 1988, 241, 1218-21. doi: 10.1126/science.2457950. [CrossRef]

- O'Connor, T.M.; O'Connell, J.; O'Brien, D.I.; Goode, T.; Bredin, C.P.; Shanahan, F. The role of substance P in inflammatory disease. J. Cell. Physiol. 2004, 201, 167. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20061. PMID: 15334652. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Bhattacharyya, D. Contribution of phenylalanine side chain intercalation to the TATA-box binding protein-DNA interaction: molecular dynamics and dispersion-corrected density functional theory studies. J. Mol. Model. 2014, 20, 2499. doi: 10.1007/s00894-014-2499-7. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Coveñas, R. Involvement of substance P and the NK-1 receptor in cancer progression. Peptides. 2013, 48, 1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.07.024. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Coveñas, R.; Esteban, F.; Redondo, M. The substance P/NK-1 receptor system: NK-1 receptor antagonists as anti-cancer drugs. J. Biosciences. 2015 ,40, 441-463. doi: 10.1007/s12038-015-9530-8. [CrossRef]

- Eistetter, H.R.; Mills, A.; Brewster, R.; Alouani, S.; Rambosson, C.; Kawashima, E. Functional characterization of neurokinin-1 receptors on human U373MG astrocytoma cells. Glia. 1992, 6, 89-95. doi: 10.1002/glia.440060203. [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Sharif, T.R.; Sharif, M. Substance P-induced mitogenesis in human astrocytoma cells correlates with activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 1996, 56, 4983-91.

- Castagliuolo, I.; Valenick, L.; Liu, J.; Pothoulakis, C. Epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation mediates substance P-induced mitogenic responses in U-373 MG cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 26545-50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003990200. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Kugimiya, T.; Miyazaki, T. Substance P receptor in U373 MG human astrocytoma cells activates mitogen-activated protein kinases ERK1/2 through Src. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2005 a, 22, 1-8.doi: 10.1007/s10014-005-0178-1. [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M.; Sharif, T.; Dilling, M.; Hosoi, H.; Lawrence, J.; Houghton, P. Rapamycin inhibits substance P-induced protein synthesis and phosphorylation of PHAS-I (4E-BP1) and p70 S6 kinase (p70(S6K)) in human astrocytoma cells. Int. J. Oncol. 1997, 11, 797-805. doi: 10.3892/ijo.11.4.797. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.F.; Gartenhaus, R.B. Phospho-p70S6K and cdc2/cdk1 as therapeutic targets for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets. 2009, 13, 1085-93. doi: 10.1517/14728220903103833. [CrossRef]

- Barzegar Behrooz, A.; Talaie, Z.; Jusheghani, F.; Łos, M.J.; Klonisch, T.; Ghavami, S. Wnt and PI3K/Akt/mTOR Survival Pathways as Therapeutic Targets in Glioblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1353. doi: 10.3390/ijms23031353. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Richardson, M.D.; Bigner, D.D.; Kwatra, M.M. Signal transduction through substance P receptor in human glioblastoma cells: roles for Src and PKCdelta. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2005b, 56, 585-93. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-1030-3. [CrossRef]

- Sherr, C.J.; Weber, J.D. The ARF/p53 pathway. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2000,10,94-9.

- Majewska, E.; Szeliga, M. AKT/GSK3β Signaling in Glioblastoma. Neurochem. Res. 2017; 42, 918-924. doi: 10.1007/s11064-016-2044-4. [CrossRef]

- Ballester, L.Y.; Wang, Z.; Shandilya, S.; Miettinen, M.; Burger, P.C.; Eberhart, C.G.; Rodriguez, F.J.; Raabe, E.; Nazarian, J.; Warren, K.; Quezado, M.M. Morphologic characteristics and immunohistochemical profile of diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2013, 37, 1357-64. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318294e817. [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O. On the Origin of Cancer Cells. Science. 1956, 123, 309-314.doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [CrossRef]

- Medrano, S.; Gruenstein, E.; Dimlich, R.V. Substance P receptors on human astrocytoma cells are linked to glycogen breakdown. Neurosci. Lett. 1994, 167, 14-8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)91017-0. [CrossRef]

- Lochhead, P.A.; Coghlan, M.; Rice, S.Q.; Sutherland, C. Inhibition of GSK-3 selectively reduces glucose-6-phosphatase and phosphatase and phosphoenolypyruvate carboxykinase gene expression. Diabetes. 2001, 50, 937-46. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.5.937. [CrossRef]

- Harford-Wright, E.; Lewis, K.M.; Vink, R.; Ghabriel, M.N. Evaluating the role of substance P in the growth of brain tumors. Neurosci. 2014a, 261, 85-94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience. [CrossRef]

- Ziche, M.; Morbidelli, L.; Pacini, M.; Geppetti, P.; Alessandri, G.; Maggi, CA. Substance P stimulates neovascularization in vivo and proliferation of cultured endothelial cells. Microvasc Res. 1990, 40, 264-78. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(90)90024-l. [CrossRef]

- Gallicchio, M.; Rosa, A.C.; Benetti, E.; Collino, M.; Dianzani, C.; Fantozzi, R. Substance P-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 147, 681-9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706660. [CrossRef]

- Melincovici CS, Boşca AB, Şuşman S, Mărginean M, Mihu C, Istrate M, Moldovan IM, Roman AL, Mihu CM. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) - key factor in normal and pathological angiogenesis. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2018, 59, 455-467.

- Takahashi, Y.; Kitadai, Y.; Bucana, C.D.; Cleary, K.R.; Ellis, L.M. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor, KDR, correlates with vascularity, metastasis, and proliferation of human colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1995, 55, 3964-396.

- Song, H.; Yin, W.; Zeng, Q.; Jia, H.; Lin, L.; Liu, X.; Mu, L.; Wang, R. Hemokinins modulate endothelium function and promote angiogenesis through neurokinin-1 receptor. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2012, 44, 1410-142. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.04.014. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; He, D.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Pan, D.; Chen, G. Overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor indicates poor outcomes of glioma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 8709-19.

- Balkwill, F.; Mantovani, A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001, 357, 539-45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [CrossRef]

- Burmeister, A.R.; Johnson, M.B.; Chauhan, V.S.; Moerdyk-Schauwecker, M.J.; Young, A.D.; Cooley, I.D.; Martinez, AN.; Ramesh. G.; Philipp, M.T.; Marriott, I.: Human microglia and astrocytes constitutively express the neurokinin-1 receptor and functionally respond to substance P. J. Neuroinflammation. 2017, 14, 245. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-1012-5. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Xu, X.; Ge, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, G.Q.; Miao, L.; Deng, X.;Aprepitant Inhibits JNK and p38/MAPK to Attenuate Inflammation and Suppresses Inflammatory Pain. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 12,811584. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.811584. [CrossRef]

- Lieb, K.; Fiebich, B.L.; Berger, M.; Bauer, J.; Schulze-Osthoff, K. The neuropeptide substance P activates transcription factor NF-kappa B and kappa B-dependent gene expression in human astrocytoma cells. J. Immunol. 1997, 159, 4952-8.

- Lieb, K.; Schaller, H.; Bauer, J.; Berger, M.; Schulze-Osthoff, K.; Fiebich, B.L. Substance P and histamine induce interleukin-6 expression in human astrocytoma cells by a mechanism involving protein kinase C and nuclear factor-IL-6. J. Neurochem. 1998, 70, 1577-1583. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70041577. x. [CrossRef]

- Fiebich, B.L.; Schleicher, S.; Butcher, R.D.; Craig, A.; Lieb, K. The neuropeptide substance P activates p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase resulting in IL-6 expression independently from NF-kappa B. J. Immunol. 2000, 165, 5606-11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5606. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Kumakura, S.; Murakami, T.; Someya, A.; Inada, E.; Nagaoka, I. Ketamine suppresses the substance P-induced production of IL-6 and IL-8 by human U373MG glioblastoma/astrocytoma cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 39, 687–692. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.2875. [CrossRef]

- Douglas, S.D.; Ho, W.Z.; Gettes, D.R.; Cnaan, A.; Zhao, H.; Leserman, J.; Petitto, J.M.; Golden, R.N.; Evans, D.L. Elevated substance P levels in HIV-infected men. A.I.D.S. 2001, 15, 2043-5. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200110190-00019. [CrossRef]

- Monaco-Shawver, L.; Schwartz, L.; Tuluc, F.; Guo, C.J.; Lai, J.P.; Gunnam, S.M.; Kilpatrick, L.E.; Banerjee, P.P.; Douglas, S.D.; Orange, J.S. Substance P inhibits natural killer cell cytotoxicity through the neurokinin-1 receptor. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2011, 89, 113-25. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0410200. [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, N.A.P.; DeGolier, K.; Kovar, H.M.; Davis, A.; Hoglund, V.; Stevens, J.; Winter, C.; Deutsch, G.; Furlan, S.N.; Vitanza, N.A.; Leary, S.E.S.; Crane, C.A. Characterization of the immune microenvironment of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: implications for development of immunotherapy. Neuro. Oncol. 2019, 21, 83-94.doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy145.

- Lim, J.E.; Chung, E.; Son, Y. A neuropeptide, Substance-P, directly induces tissue-repairing M2 like macrophages by activating the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway even in the presence of IFNγ. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9417. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09639-7. [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Zhang, B.; Kempuraj, D.; Tagen, M.; Vasiadi, M.; Angelidou, A.; Alysandratos, K.D.; Kalogeromitros, D.; Asadi, S.; Stavrianeas, N.; Peterson, E.; Leeman, S.; Conti, P. IL-33 augments substance P-induced VEGF secretion from human mast cells and is increased in psoriatic skin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 4448-53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000803107. [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Hu, H.; Xie, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, D.; Mo, W.; Zhang, R.; Yu, M. An involvement of neurokinin-1 receptor in FcεRΙ-mediated RBL-2H3 mast cell activation. Inflamm. Res. 2012, 61,1257-63. doi: 10.1007/s00011-012-0523-x. [CrossRef]

- Seegers, H.C.; Hood, V.C.; Kidd, B.L.; Cruwys, S.C.; Walsh, D.A. Enhancement of angiogenesis by endogenous substance P release and neurokinin-1 receptors during neurogenic inflammation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 306, 8-12. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.050013. [CrossRef]

- Lang, K.; Drell, T.L. 4th; Lindecke, A.; Niggemann, B.; Kaltschmidt, C.; Zaenker, K.S.; Entschladen, F. Induction of a metastatogenic tumor cell type by neurotransmitters and its pharmacological inhibition by established drugs. Int. J. Cancer. 2004, 112, 231-8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20410. [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; Neilson, E.G. Epithelial- mesenchymal transition and its implications for fibrosis. J. Clin. Invest. 2003, 112, 1776–1784. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.050013. [CrossRef]

- Meel, M.H.; Schaper, S.A.; Kaspers, G.J.L.; Hulleman, E. Signaling pathways and mesenchymal transition in pediatric high-grade glioma. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 871-887. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2714-7. [CrossRef]

- Wheelock, M.J.; Shintani, Y.; Maeda, M.; Fukumoto, Y.; Johnson, K.R. Cadherin switching. J. Cell Sci. 2008, 121, 727-35. doi: 10.1242/jcs.000455. [CrossRef]

- Agiostratidou, G.; Hulit, J.; Phillips, G.R.; Hazan, R.B. Differential cadherin expression: potential markers for epithelial to mesenchymal transformation during tumor progression. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia. 2007, 12, 127-33. doi: 10.1007/s10911-007-9044-6. [CrossRef]

- Péglion, F.; Etienne-Manneville, S. N-cadherin expression level as a critical indicator of invasion in non-epithelial tumors. Cell Adh. Migr. 2012, 6, 327-32. doi: 10.4161/cam.20855. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kumaravel, S.; Dhole, S.; Roy, S.; Pavan, V.; Chakraborty, S. Neuropeptide Substance P Enhances Inflammation-Mediated Tumor Signaling Pathways and Migration and Proliferation of Head and Neck Cancers. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 12, 93-102. doi: 10.1007/s13193-020-01210-7. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yan, D.; Guo, S.W. Sensory nerve-derived neuropeptides accelerate the development and fibrogenesis of endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2019, 34, 452-468. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey392. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Tu, Y.; Sun, X.; Jiang, J.; Jin, X.; Bo, X.; Li, Z.; Bian, A.; Wang, X.; Liu, D.; Wang, Z.; Ding, L. Wnt/beta-Catenin pathway in human glioma: Expression pattern and clinical/prognostic correlations. Clin. Exp. Med. 2010, 11, 105–112. doi: 10.1007/s10238-010-0110-9. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, B.T.; Tamai, K.; He, X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev. Cell. 2009, 17, 9-26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. [CrossRef]

- Veeman, M.T.; Axelrod, J.D.; Moon, R.T. A second canon. Functions and mechanisms of beta-catenin-independent Wnt signaling. Dev. Cell. 2003, 5, 367-77. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00266-1. [CrossRef]

- Mei, G.; Xia, L.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tuo, Y.; Fu, S.; Zou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Jin, D. Neuropeptide SP activates the WNT signal transduction pathway and enhances the proliferation of bone marrow stromal stem cells. Cell Biol. Int. 2013, 37, 1225-32. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10158. [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Jin, D.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Mei, G.; Zou, Z.L.; Wu, J.Q.; Xu, Z.Y. Protective effect of neuropeptide substance P on bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells against apoptosis induced by serum deprivation. Stem Cells Int. 2015, 270328. doi: 10.1155/2015/270328. [CrossRef]

- Ji H, Wang J, Nika H, Hawke D, Keezer S, Ge Q, Fang B, Fang X, Fang D, Litchfield DW, Aldape K, Lu Z. EGF-induced ERK activation promotes CK2-mediated disassociation of alpha-Catenin from beta-Catenin and transactivation of beta-Catenin. Mol. Cell. 2009, 36, 547-59. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.034. [CrossRef]

- Fackler, O.T.; Grosse, R. Cell motility through plasma membrane blebbing. J. Cell. Biol. 2008, 181, 879-84. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200802081. [CrossRef]

- Meshki, J.; Douglas, S.D.; Lai, J.P.; Schwartz, L.; Kilpatrick, L.E.; Tuluc, F. Neurokinin 1 receptor mediates membrane blebbing in HEK293 cells through a Rho/Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 9280-9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808825200. [CrossRef]

- Meshki, J.; Douglas, S.D.; Hu, M.; Leeman, S.E.; Tuluc, F. Substance P induces rapid and transient membrane blebbing in U373MG cells in a p21-activated kinase-dependent manner. PLoS One. 2011, 6, e25332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025332. [CrossRef]

- Rolfe, K.J.; Grobbelaar, A.O. A review of fetal scarless healing. I.S.R.N. Dermatol. 2012, 698034. doi: 10.5402/2012/698034. [CrossRef]

- Roomi, M.W.; Monterrey, J.C.; Kalinovsky, T.; Rath, M.; Niedzwiecki, A. Patterns of MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression in human cancer cell lines. Oncol. Rep. 2009, 5, 1323-33. doi: 10.3892/or_00000358. [CrossRef]

- VanMeter, T.E.; Rooprai, H.K.; Kibble, M.M.; Fillmore, H.L.; Broaddus, W.C.; Pilkington, G.J. The role of matrix metalloproteinase genes in glioma invasion: co-dependent and interactive proteolysis. J. Neurooncol. 2000, 53, 213-35. doi: 10.1023/a:1012280925031. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, F.D.; Coveñas, R. Substance P receptor antagonists. In Molecular Mediators in Health and Disease: How Cells Communicate, Substance P; Vink, R. Eds.; Academic Press, Elsevier Inc, 2025; pp. 95-117. doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-22194-1.00010-0. [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, R.W.; Ruefli, A.A.; Lowe, S.W. Apoptosis: a link between cancer genetics and chemotherapy. Cell 2002, 108, 153–164. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00625-6. [CrossRef]

- Palma, C.; Bigioni, M.; Irrissuto, C.; Nardelli, F.; Maggi, C.A.; Manzini, S. Anti-tumour activity of tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonists on human glioma U373 MG xenograft. Br. J. Cancer 2000, 82, 480-7. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0946. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Rosso, M.; González, A.; Saenz, J.; Coveñas, R. The broad-spectrum antitumor action of cyclosporin A is due to its tachykinin receptor antagonist pharmacological profile. Peptides. 2010, 31, 1643-1648. 0.1016/j.peptides.2010.06.002. [CrossRef]

- Kotliarova, S.; Pastorino, S.; Kovell, L.C.; Kotliarov, Y.; Song, H.; Zhang, W.; Bailey, R.; Maric, D.; Zenklusen, J.C.; Lee, J.; Fine, H.A. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibition induces glioma cell death through c-MYC, nuclear factor-kappaB, and glucose regulation. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 6643-51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0850. [CrossRef]

- Guha, S.; Eibl, G.; Kisfalvi, K., Fan, R. S.; Burdick, M.; Reber, H., ... & Rozengurt, E. Broad-spectrum G protein–coupled receptor antagonist, [D-Arg1, D-Trp5, 7, 9, Leu11] SP: a dual inhibitor of growth and angiogenesis in pancreatic cancer. Cancer research. 2005, 65, 2738-2745.

- Berger, M.; Neth, O.; Ilmer, M.; Garnier, A.; Salinas-Martín, M.V.; de Agustín Asencio, J.C.; von Schweinitz, D., Kappler, R.; Muñoz, M. Hepatoblastoma cells express truncated neurokinin-1 receptor and can be growth inhibited by aprepitant in vitro and in vivo. J. Hepatol. 2014, 60, 985-94. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.12.024. [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.L.; Hou, J.F.; Li, J.X. The NK1 receptor antagonist NKP608 inhibits proliferation of human colorectal cancer cells via Wnt signaling pathway. Biol. Res. 2018, 51, 14. doi: 10.1186/s40659-018-0163-x. [CrossRef]

- Momen Razmgah, M.; Ghahremanloo, A.; Javid, H.; AlAlikhan, A.; Afshari, A.R.; Hashemy, S.I. The effect of substance P and its specific antagonist (aprepitant) on the expression of MMP-2, MMP-9, VEGF, and VEGFR in ovarian cancer cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 9307-9314. doi: 10.1007/s11033-022-07771-w. [CrossRef]

- Alsaeed, M.A.; Ebrahimi, S.; Alalikhan, A.; Hashemi, S.F.; Hashemy, S.I. The Potential In Vitro Inhibitory Effects of Neurokinin-1 Receptor (NK-1R) Antagonist, Aprepitant, in Osteosarcoma Cell Migration and Metastasis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 8082608. doi: 10.1155/2022/8082608. [CrossRef]

- Sporn, M.B. The war on cancer. Lancet. 1996, 347, 1377-81. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91015-6. [CrossRef]

- Myung, J.K.; Ah Choi, S.; Kim, S.K.; Ik Kim S, Park JW, Park SH. The role of ZEB2 expression in pediatric and adult glioblastomas. Anticancer Res. 2021, 41,175-185. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.14763. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Sang, M.; Liu, F.; Gu, L.; Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Shan, B. Aprepitant inhibits the progression of esophageal squamous cancer by blocking the truncated neurokinin-1 receptor. Oncol. Rep. 2023, 50, 131. doi: 10.3892/or.2023.8568. [CrossRef]

- Harford-Wright E, Lewis KM, Ghabriel MN, Vink R. Treatment with the NK1 antagonist emend reduces blood brain barrier dysfunction and edema formation in an experimental model of brain tumors. PLoS One. 2014b,9, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097002. [CrossRef]

- Hargrave, D.; Bartels, U.; Bouffet, E. Diffuse brainstem glioma in children: critical review of clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2006, 3, 241-8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70615-5. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Suh, C.O. Radiotherapy for Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma: Insufficient but Indispensable. Brain Tumor Res. Treat. 2023, 11, 79-85. doi: 10.14791/btrt.2022.0041. [CrossRef]

- Limon, D.; McSherry, F.; Herndon, J.; Sampson, J.; Fecci, P.; Adamson, J.; Wang, Z.; Yin, F.F.; Floyd, S.; Kirkpatrick, J.; Kim, G.J. Single fraction stereotactic radiosurgery for multiple brain metastases. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2017, 2, 555-563. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2017.09.002. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Crespo, J.C.; Crespo, J.P.; Coveñas, R. Neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist aprepitant and radiotherapy, a successful combination therapy in a patient with lung cancer: A case report. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 11, 50-54. doi: 10.3892/mco.2019.1857. [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, A.B.; Cubeddu, LX. Efectos de los antagonistas de los receptores NK1 y de la dexametasona sobre la inflamación neurogénica inducida por ciclofosfamida y por radiación X, en la rata. A.V.F.T. 2004, 23, 61-66.

- Bergström, M.; Fasth, K.J.; Kilpatrick, G.; Ward, P.; Cable, K.M.; Wipperman, M.D.; Sutherland, D.R.; Långström, B. Brain uptake and receptor binding of two [11C]labelled selective high affinity NK1-antagonists, GR203040 and GR205171--PET studies in rhesus monkey. Neuropharmacology. 2000, 39, 664-70. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00182-3. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kumari, P.; Pandey, S.; Singh, S.K.; Kumar, R. Amelioration of Radiation-Induced Cell Death in Neuro2a Cells by Neutralizing Oxidative Stress and Reducing Mitochondrial Dysfunction Using N-Acetyl-L-Tryptophan. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 9124365. doi: 10.1155/2022/9124365. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P.; Coveñas, R.; Muñoz. M. Combination Therapy of Chemotherapy or Radiotherapy and the Neurokinin-1 Receptor Antagonist Aprepitant: A New Antitumor Strategy?. Curr. Med. Chem. 2023, 30,1798-1812. doi: 10.2174/0929867329666220811152602. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Coveñas, R. Safety of neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists. Expert. Opin. Drug Saf. 2013b, 12, 673-85. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2013.804059. [CrossRef]

- Okumura, L.M.; da Silva Ries, S.A.; Meneses, C.F.; Michalowski, M.B.; Ferreira, M.A.P.; Moreira, L.B. Adverse events associated with aprepitant pediatric bone cancer patients. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 25, 735-738. doi: 10.1177/1078155218755547. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Guo, Q.L.; Zhang, T.T.; Fu, M.; Bi, H.T.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zou, K.L. Efficacy and safety of Aprepitant-containing triple therapy for the prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023, 102, e35952. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000035952. [CrossRef]

- Molinos-Quintana, A.; Trujillo-Hacha, P.; Piruat, J.I.; Bejarano-García, J.A.; García-Guerrero, E.; Pérez-Simón, J.A.; Muñoz, M. Human acute myeloid leukemia cells express neurokinin-1 receptor, which is involved in the antileukemic effect of neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists. Invest. New Drugs. 2019, 37, 17–26. doi: 10.1007/s10637-018-0607-8. [CrossRef]

- Kramer MS, Cutler N, Feighner J, Shrivastava R, Carman J, Sramek JJ, Reines SA, Liu G, Snavely D, Wyatt-Knowles E, Hale JJ, Mills SG, MacCoss M, Swain CJ, Harrison T, Hill RG, Hefti F, Scolnick EM, Cascieri MA, Chicchi GG, Sadowski S, Williams AR, Hewson L, Smith D, Carlson EJ, Hargreaves RJ, Rupniak NM. Distinct mechanism for antidepressant activity by blockade of central substance P receptors. Science. 1998, 281, 1640-5. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1640. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; McCloskey, M.; Staples, S. Prolonged use of aprepitant in metastatic breast cancer and a reduction in CA153 tumour marker levels. Int. J. Cancer Clin. Res. 2016, 3, 071. doi: 10.23937/2378-3419/3/6/1071. [CrossRef]

- Tebas, P.; Spitsin, S.; Barrett, J.S.; Tuluc, F.; Elci, O.; Korelitz, J.J.; Wagner, W.; Winters, A.; Kim, D.; Catalano, R.; Evans, D.L.; Douglas, S.D. Reduction of soluble CD163, substance P, programmed death 1 and inflammatory markers: phase 1B trial of aprepitant in HIV-1-infected adults. A.I.D.S. 2015, 29, 931-9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000638. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Chen, J.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, B.; Sun, X.; Ke, Y. CD163, a novel therapeutic target, regulates the proliferation and stemness of glioma cells via casein kinase 2. Oncogene. 2019, 38, 1183-1199. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0515-6. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).