Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Generation of Liver Micro-Organoids

2.3. MASLD Induction in Liver Micro-Organoids

2.4. Mitochondrial Activity

2.5. DNA Isolation and Quantification

2.6. Lactate Dehydrogenase

2.7. Live-Dead Staining

2.8. Fatty Acid Quantification and Fluorescence Microscopy

2.9. RNA Isolation, cDNA Synthesis, and PCR Analysis

2.10. Dot Blot Analysis

2.11. Vitamin D Metabolism Activity Using Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays

2.12. Bioinformatics RNA-Sequencing Analysis

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. RNA-Sequencing Data Shows Impaired Expression of Genes Involved in Vitamin D Metabolism and Signaling

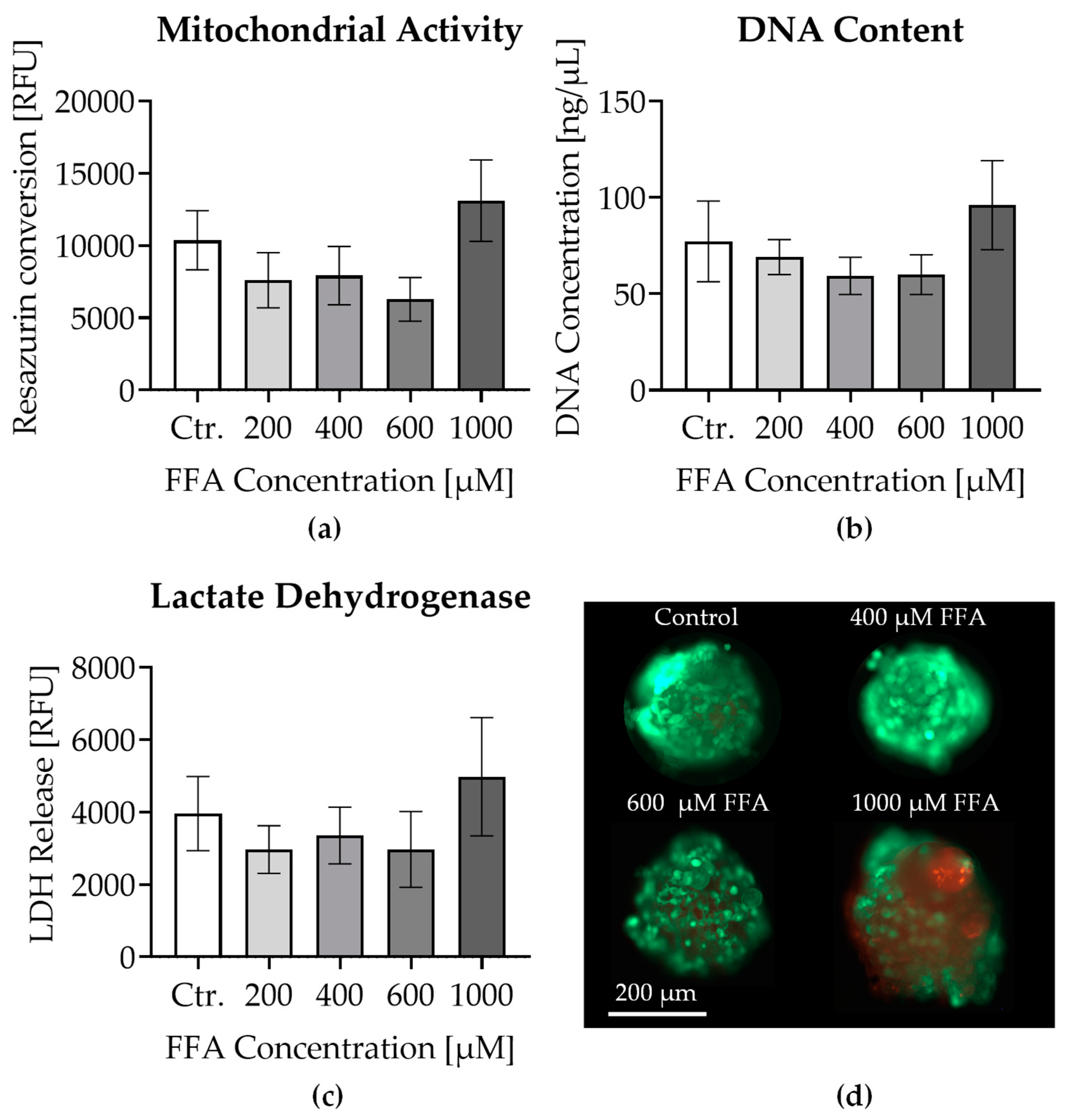

3.2. Effects of Oleic and Palmitic Acid Treatment on Liver Micro-Organoid Viability

3.3. Visualization and Quantification of Lipid Accumulation in Liver Micro-Organoids Treated with Oleic and Palmitic Acids

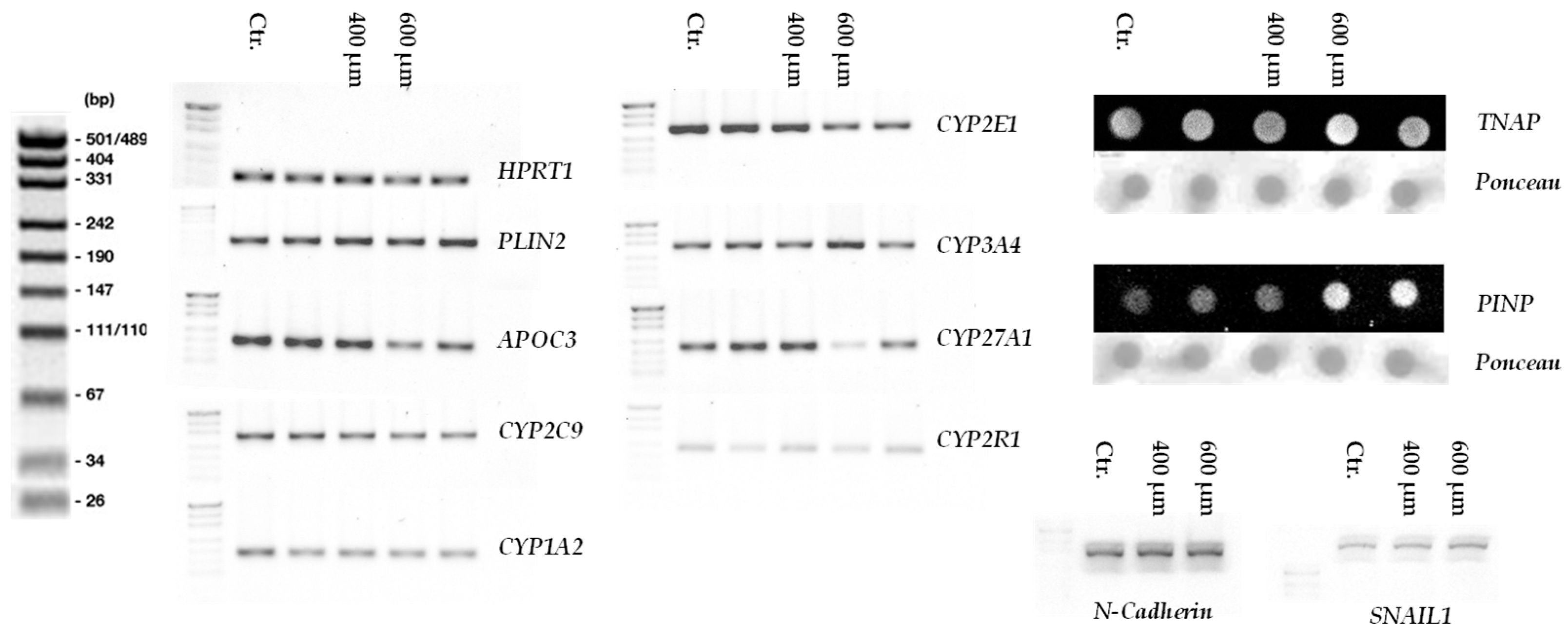

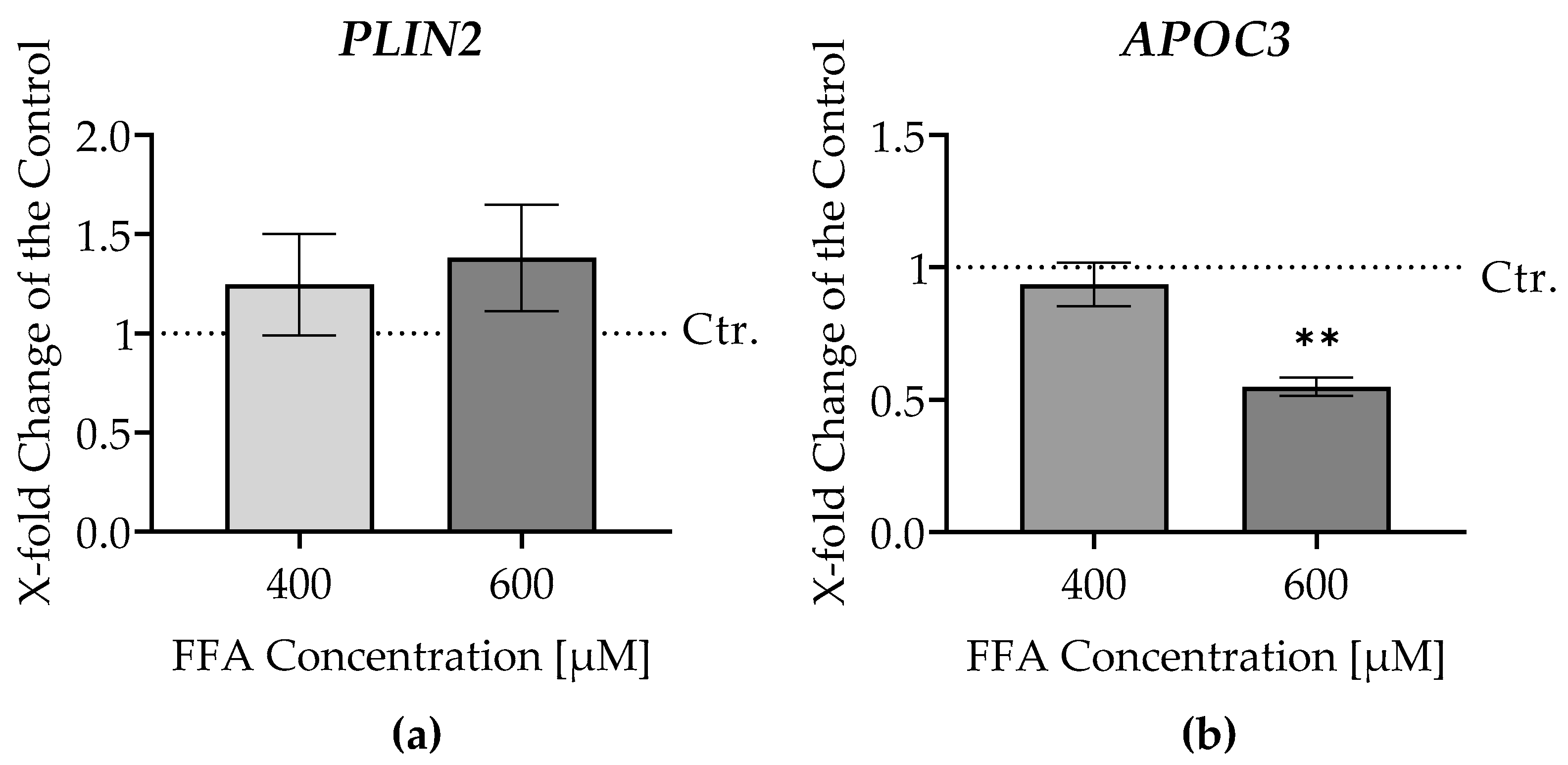

3.4. Gene Expression Analysis of Fatty Acid Metabolism in Liver Micro-Organoids Treated with Oleic and Palmitic Acids

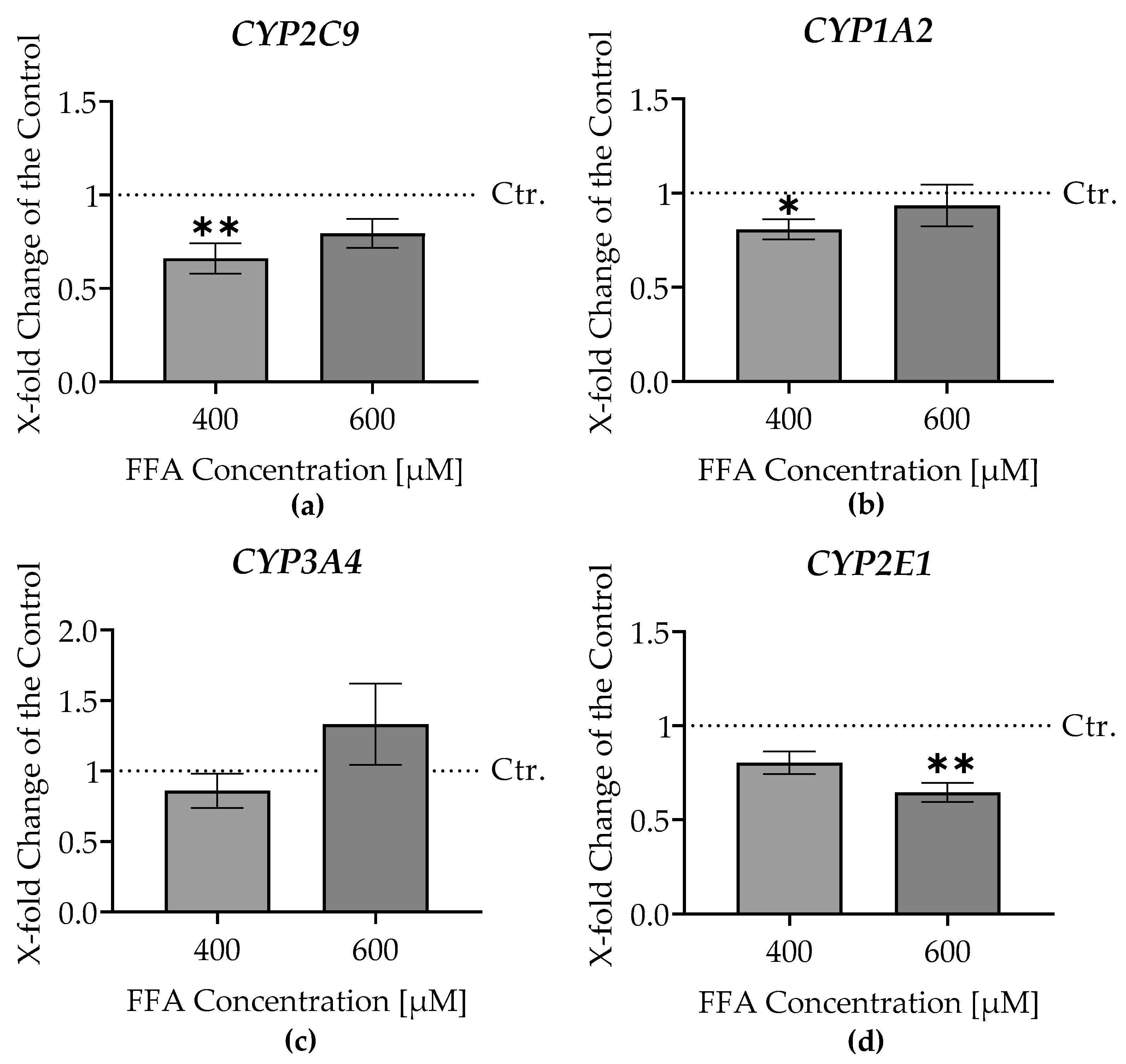

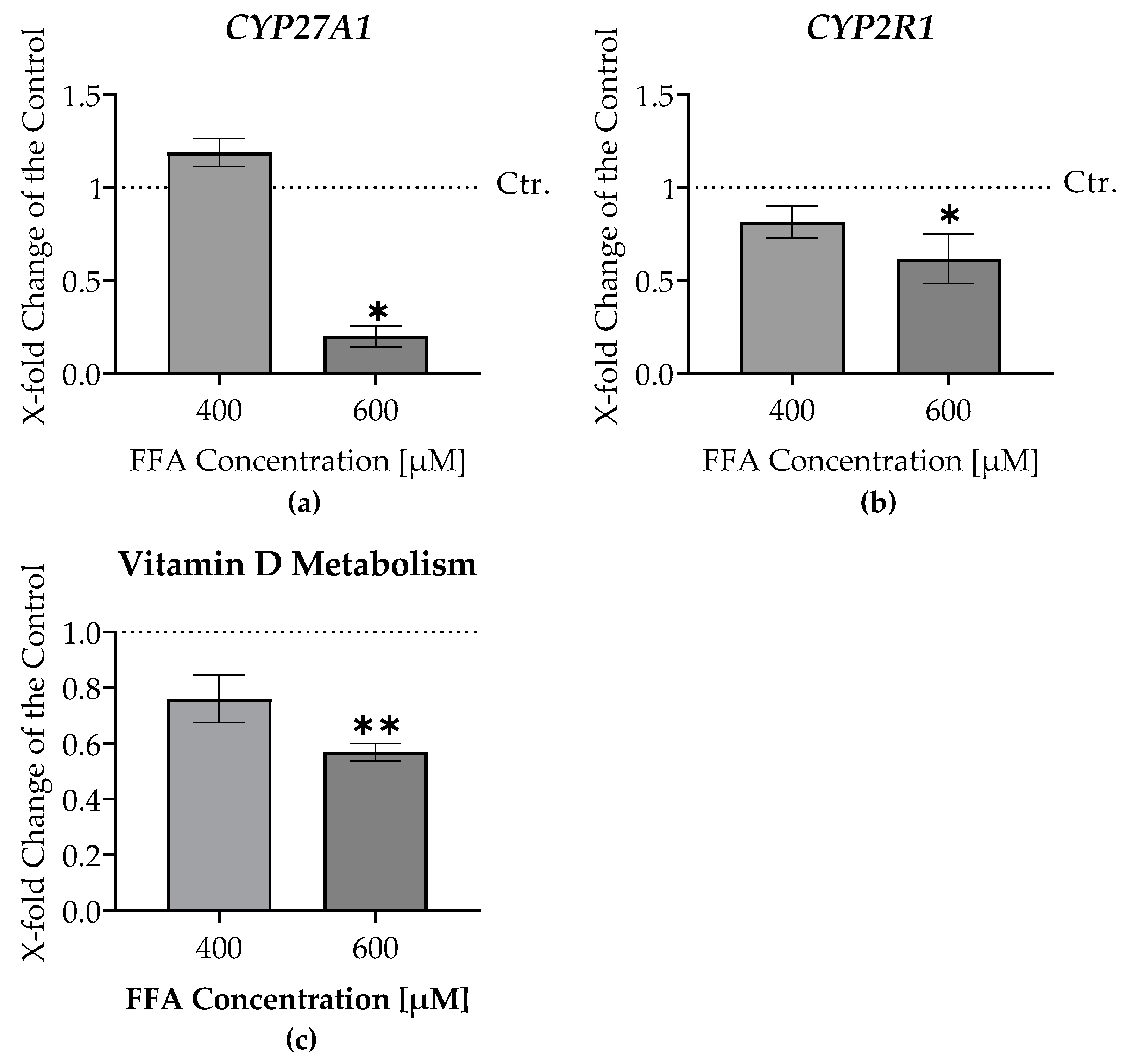

3.5. RT-PCR Analysis of CYP Enzyme Gene Expression in Liver Micro-Organoids Exposed to Oleic and Palmitic Acids

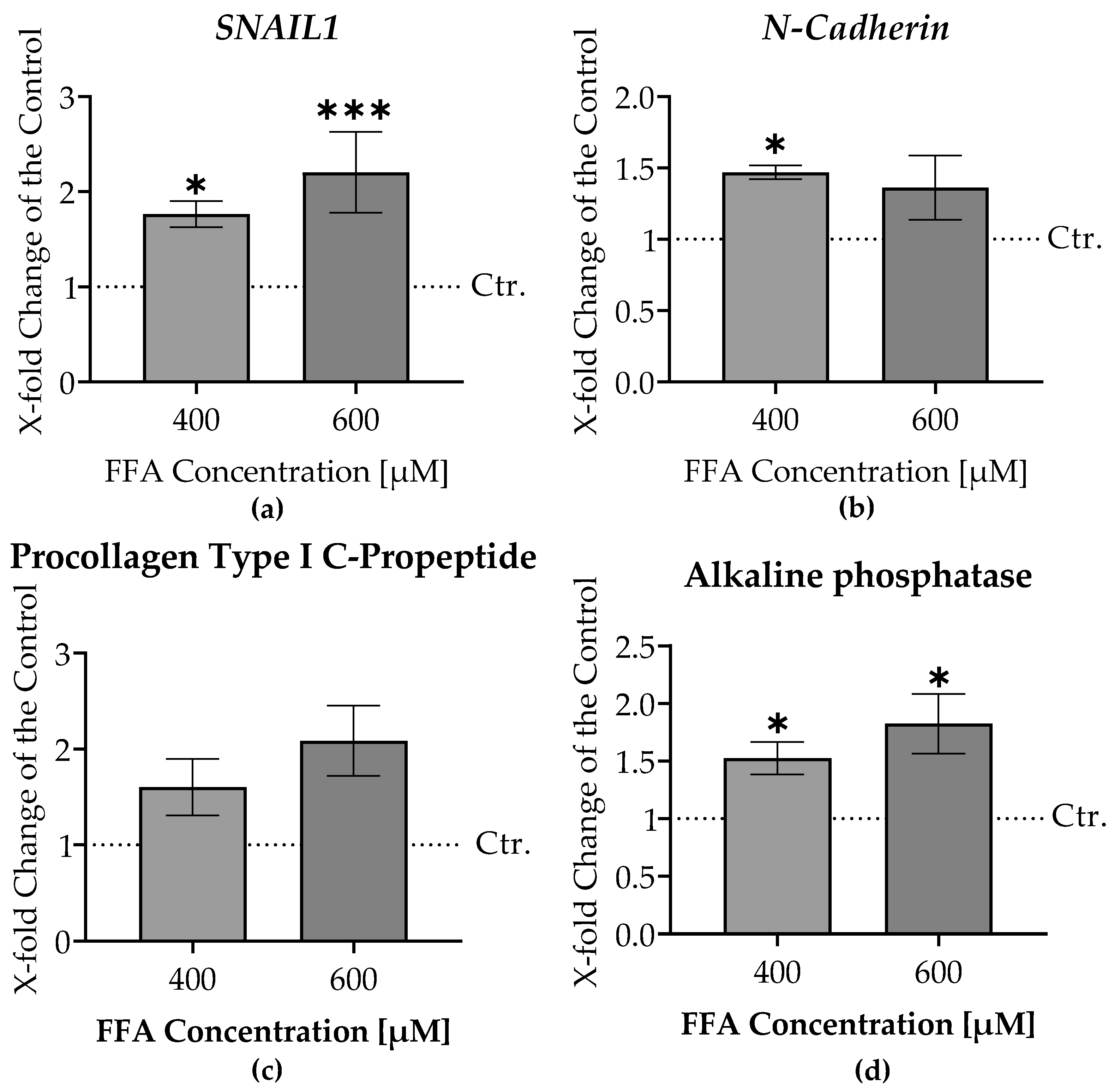

3.7. Increased Liver Damage and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Markers in Liver Micro-Organoids Treated with Oleic and Palmitic Acids

3.6. Impaired Vitamin D Metabolism in Liver Micro-Organoids Treated with Oleic and Palmitic Acids

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

References

- Pipitone, R.M.; Ciccioli, C.; Infantino, G.; La Mantia, C.; Parisi, S.; Tulone, A.; Pennisi, G.; Grimaudo, S.; Petta, S. MAFLD: a multisystem disease. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 2023, 14, 20420188221145549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zou, B.; Yeo, Y.H.; Feng, Y.; Xie, X.; Lee, D.H.; Fujii, H.; Wu, Y.; Kam, L.Y.; Ji, F.; et al. Prevalence, incidence, and outcome of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Asia, 1999–2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2019, 4, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, Y. Global incidence of NAFLD: Sets alarm bells ringing about NAFLD in China again. Journal of Hepatology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geier, A.; Rau, M.; Pathil-Warth, A.; von der Ohe, M.; Schattenberg, J.; Dikopoulos, N.; Stein, K.; Serfert, Y.; Berg, T.; Buggisch, P. Clinical characteristics of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in Germany–First data from the German NAFLD-Registry. Zeitschrift für Gastroenterologie 2023, 61, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobbina, E.; Akhlaghi, F. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)—pathogenesis, classification, and effect on drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters. Drug Metab Rev 2017, 49, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wree, A.; Broderick, L.; Canbay, A.; Hoffman, H.M.; Feldstein, A.E. From NAFLD to NASH to cirrhosis—new insights into disease mechanisms. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology 2013, 10, 627–636. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.-b.; Jin, M.H.; Yoon, J.-H. The contribution of vitamin D insufficiency to the onset of steatotic liver disease among individuals with metabolic dysfunction. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 6714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, B.; Gao, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, R. Association between serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D level and metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD)—a population-based study. Endocrine Journal 2021, 68, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintermeyer, E.; Ihle, C.; Ehnert, S.; Stöckle, U.; Ochs, G.; de Zwart, P.; Flesch, I.; Bahrs, C.; Nussler, A.K. Crucial Role of Vitamin D in the Musculoskeletal System. Nutrients 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, S.; Giusti, A.; Minisola, S.; Napoli, N.; Passeri, G.; Rossini, M.; Sinigaglia, L. The Immunologic Profile of Vitamin D and Its Role in Different Immune-Mediated Diseases: An Expert Opinion. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, J.T.; Elangovan, H.; Stokes, R.A.; Gunton, J.E. Vitamin D and the Liver-Correlation or Cause? Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argano, C.; Mirarchi, L.; Amodeo, S.; Orlando, V.; Torres, A.; Corrao, S. The Role of Vitamin D and Its Molecular Bases in Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome, and Cardiovascular Disease: State of the Art. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 15485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehnert, S.; Aspera-Werz, R.H.; Ruoß, M.; Dooley, S.; Hengstler, J.G.; Nadalin, S.; Relja, B.; Badke, A.; Nussler, A.K. Hepatic Osteodystrophy—Molecular Mechanisms Proposed to Favor Its Development. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.; Dar, H.A.; Baba, M.A.; Shah, A.H.; Singh, B.; Shiekh, N.A. Impact of Vitamin D Status in Chronic Liver Disease. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2019, 9, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchetta, I.; Cimini, F.A.; Cavallo, M.G. Vitamin D and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD): An Update. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissen, T.; Wynn, R. The clinical case report: a review of its merits and limitations. BMC Research Notes 2014, 7, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson-Hughes, B.; Staten, M.A.; Knowler, W.C.; Nelson, J.; Vickery, E.M.; LeBlanc, E.S.; Neff, L.M.; Park, J.; Pittas, A.G. Intratrial Exposure to Vitamin D and New-Onset Diabetes Among Adults With Prediabetes: A Secondary Analysis From the Vitamin D and Type 2 Diabetes (D2d) Study. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 2916–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Y. The Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R.; Manousaki, D.; Rosen, C.; Trajanoska, K.; Rivadeneira, F.; Richards, J.B. The health effects of vitamin D supplementation: evidence from human studies. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2022, 18, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimnes, G.; Figenschau, Y.; Almås, B.; Jorde, R. Vitamin D, insulin secretion, sensitivity, and lipids: results from a case-control study and a randomized controlled trial using hyperglycemic clamp technique. Diabetes 2011, 60, 2748–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.M.; Leder, B.Z.; Cagliero, E.; Mendoza, N.; Henao, M.P.; Hayden, D.L.; Finkelstein, J.S.; Burnett-Bowie, S.A. Insulin secretion and sensitivity in healthy adults with low vitamin D are not affected by high-dose ergocalciferol administration: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2015, 102, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamka, M.; Woźniewicz, M.; Jeszka, J.; Mardas, M.; Bogdański, P.; Stelmach-Mardas, M. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on insulin and glucose metabolism in overweight and obese individuals: systematic review with meta-analysis. Scientific Reports 2015, 5, 16142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, S.; Inal, J.M. Animal Models of Human Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 15821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loewa, A.; Feng, J.J.; Hedtrich, S. Human disease models in drug development. Nature Reviews Bioengineering 2023, 1, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.H.; Jeong, H.-J.; Lee, Y.J.; Park, H.Y.; Koo, S.K.; Lim, J.H. Vitamin D ameliorates age-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by increasing the mitochondrial contact site and cristae organizing system (MICOS) 60 level. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2024, 56, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shen, Z.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, P.; Zeng, H.; Yu, M.; Chen, X.; Ning, L.; et al. Vitamin D receptor targets hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α and mediates protective effects of vitamin D in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Biol Chem 2020, 295, 3891–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punt, A.; Peijnenburg, A.A.; Hoogenboom, R.L.; Bouwmeester, H. Non-animal approaches for toxicokinetics in risk evaluations of food chemicals. ALTEX-Alternatives to animal experimentation 2017, 34, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Dial, S.; Shi, L.; Branham, W.; Liu, J.; Fang, J.L.; Green, B.; Deng, H.; Kaput, J.; Ning, B. Similarities and differences in the expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes between human hepatic cell lines and primary human hepatocytes. Drug Metab Dispos 2011, 39, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, P.; Hewitt, N.J.; Albrecht, U.; Andersen, M.E.; Ansari, N.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bode, J.G.; Bolleyn, J.; Borner, C.; Böttger, J.; et al. Recent advances in 2D and 3D in vitro systems using primary hepatocytes, alternative hepatocyte sources and non-parenchymal liver cells and their use in investigating mechanisms of hepatotoxicity, cell signaling and ADME. Arch Toxicol 2013, 87, 1315–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruoß, M.; Vosough, M.; Königsrainer, A.; Nadalin, S.; Wagner, S.; Sajadian, S.; Huber, D.; Heydari, Z.; Ehnert, S.; Hengstler, J.G.; et al. Towards improved hepatocyte cultures: Progress and limitations. Food Chem Toxicol 2020, 138, 111188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lübberstedt, M.; Müller-Vieira, U.; Mayer, M.; Biemel, K.M.; Knöspel, F.; Knobeloch, D.; Nüssler, A.K.; Gerlach, J.C.; Zeilinger, K. HepaRG human hepatic cell line utility as a surrogate for primary human hepatocytes in drug metabolism assessment in vitro. Journal of pharmacological and toxicological methods 2011, 63, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammour, M.M.; Othman, A.; Aspera-Werz, R.; Braun, B.; Weis-Klemm, M.; Wagner, S.; Nadalin, S.; Histing, T.; Ruoß, M.; Nüssler, A.K. Optimisation of the HepaRG cell line model for drug toxicity studies using two different cultivation conditions: advantages and limitations. Archives of Toxicology 2022, 96, 2511–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Xin, Y.; Hammour, M.M.; Braun, B.; Ehnert, S.; Springer, F.; Vosough, M.; Menger, M.M.; Kumar, A.; Nüssler, A.K.; et al. Establishment of a human 3D in vitro liver-bone model as a potential system for drug toxicity screening. Arch Toxicol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gripon, P.; Rumin, S.; Urban, S.; Le Seyec, J.; Glaise, D.; Cannie, I.; Guyomard, C.; Lucas, J.; Trepo, C.; Guguen-Guillouzo, C. Infection of a human hepatoma cell line by hepatitis B virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99, 15655–15660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanuri, G.; Bergheim, I. In Vitro and in Vivo Models of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2013, 14, 11963–11980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Koo, B.K.; Knoblich, J.A. Human organoids: model systems for human biology and medicine. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020, 21, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahmatkesh, E.; Othman, A.; Braun, B.; Aspera, R.; Ruoß, M.; Piryaei, A.; Vosough, M.; Nüssler, A. In vitro modeling of liver fibrosis in 3D microtissues using scalable micropatterning system. Arch Toxicol 2022, 96, 1799–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Hui, A.Y.; Albanis, E.; Arthur, M.J.; O’Byrne, S.M.; Blaner, W.S.; Mukherjee, P.; Friedman, S.L.; Eng, F.J. Human hepatic stellate cell lines, LX-1 and LX-2: new tools for analysis of hepatic fibrosis. Gut 2005, 54, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Leyte, D.J.; Domínguez-Pérez, M.; Mercado, I.; Villarreal-Molina, M.T.; Jacobo-Albavera, L. Use of Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVEC) as a Model to Study Cardiovascular Disease: A Review. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennert, C.; Heil, T.; Schicht, G.; Stilkerich, A.; Seidemann, L.; Kegel-Hübner, V.; Seehofer, D.; Damm, G. Prolonged Lipid Accumulation in Cultured Primary Human Hepatocytes Rather Leads to ER Stress than Oxidative Stress. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeker, N.D.; Hutchinson, S.A.; Ho, L.; Trede, N.S. Method for isolation of PCR-ready genomic DNA from zebrafish tissues. Biotechniques 2007, 43, 610–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekumar, V.; Aspera-Werz, R.; Ehnert, S.; Strobel, J.; Tendulkar, G.; Heid, D.; Schreiner, A.; Arnscheidt, C.; Nussler, A.K. Resveratrol protects primary cilia integrity of human mesenchymal stem cells from cigarette smoke to improve osteogenic differentiation in vitro. Archives of Toxicology 2018, 92, 1525–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Dey, S.; Patra, S.; Bera, A.; Ghosh, T.; Prasad, B.; Sayala, K.D.; Maji, K.; Bedi, A.; Debnath, S. BODIPY-Based Molecules for Biomedical Applications. Biomolecules 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Ezpeleta, N.; Teijeiro, S.; Forget, L.; Burger, G.; Lang, B.F. Construction of cDNA Libraries: Focus on Protists and Fungi. In Expressed Sequence Tags (ESTs): Generation and Analysis, Parkinson, J., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2009; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- European Bioinformatics, I. RNA-seq of human with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease against untreated controls. 2023.

- Küçükazman, M.; Ata, N.; Dal, K.; Yeniova, A.Ö.; Kefeli, A.; Basyigit, S.; Aktas, B.; Akin, K.O.; Ağladioğlu, K.; Üre, Ö.S.; et al. The association of vitamin D deficiency with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clinics 2014, 69, 542–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.; Kwon, H.; Oh, S.W.; Joh, H.K.; Hwang, S.S.; Park, J.H.; Yun, J.M.; Lee, H.; Chung, G.E.; Ze, S.; et al. Is Vitamin D an Independent Risk Factor of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease?: a Cross-Sectional Study of the Healthy Population. J Korean Med Sci 2017, 32, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrikx, T.; Jeurissen, M.L.J.; Bieghs, V.; Walenbergh, S.M.A.; van Gorp, P.J.; Verheyen, F.; Houben, T.; Guichot, Y.D.; Gijbels, M.J.J.; Leitersdorf, E.; et al. Hematopoietic overexpression of Cyp27a1 reduces hepatic inflammation independently of 27-hydroxycholesterol levels in Ldlr−/− mice. Journal of Hepatology 2015, 62, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, D. Next-generation sequencing and its clinical application. Cancer Biol Med 2019, 16, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, Y.; Dong, Y.; Li, X.; Zhong, W.; Lei, X.; Tang, J.; Mao, Y. Current Progress and Challenges in the Development of Pharmacotherapy for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2024, 40, e3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostis, J.B.; Dobrzynski, J.M. Limitations of Randomized Clinical Trials. The American Journal of Cardiology 2020, 129, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, D.; Song, D.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, X. Clinical and translational values of spatial transcriptomics. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2022, 7, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopfleisch, R.; Gruber, A.D. Transcriptome and proteome research in veterinary science: what is possible and what questions can be asked? ScientificWorldJournal 2012, 2012, 254962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokes, T.; Cen, H.H.; Kapranov, P.; Gallagher, I.J.; Pitsillides, A.A.; Volmar, C.-H.; Kraus, W.E.; Johnson, J.D.; Phillips, S.M.; Wahlestedt, C.; et al. Transcriptomics for Clinical and Experimental Biology Research: Hang on a Seq. Advanced Genetics 2023, 4, 2200024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, W.M.S.; Burch, R.L.; Hume, C.W. The principles of humane experimental technique; Methuen London: 1959; Volume 238.

- Bell, C.C.; Hendriks, D.F.G.; Moro, S.M.L.; Ellis, E.; Walsh, J.; Renblom, A.; Fredriksson Puigvert, L.; Dankers, A.C.A.; Jacobs, F.; Snoeys, J.; et al. Characterization of primary human hepatocyte spheroids as a model system for drug-induced liver injury, liver function and disease. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 25187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ströbel, S.; Kostadinova, R.; Fiaschetti-Egli, K.; Rupp, J.; Bieri, M.; Pawlowska, A.; Busler, D.; Hofstetter, T.; Sanchez, K.; Grepper, S.; et al. A 3D primary human cell-based in vitro model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis for efficacy testing of clinical drug candidates. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 22765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrell, T.; Kastrinou-Lampou, V.; Fardellas, A.; Hendriks, D.F.G.; Nordling, Å.; Johansson, I.; Baze, A.; Parmentier, C.; Richert, L.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M. Human Liver Spheroids as a Model to Study Aetiology and Treatment of Hepatic Fibrosis. Cells 2020, 9, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, B.; Donzelli, M.; Maseneni, S.; Boess, F.; Roth, A.; Krähenbühl, S.; Haschke, M. Comparison of Liver Cell Models Using the Basel Phenotyping Cocktail. Front Pharmacol 2016, 7, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, L.J.; Morgan, K.; Treskes, P.; Samuel, K.; Henderson, C.J.; LeBled, C.; Homer, N.; Grant, M.H.; Hayes, P.C.; Plevris, J.N. Human Hepatic HepaRG Cells Maintain an Organotypic Phenotype with High Intrinsic CYP450 Activity/Metabolism and Significantly Outperform Standard HepG2/C3A Cells for Pharmaceutical and Therapeutic Applications. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2017, 120, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Römer, A.; Rawat, D.; Linn, T.; Petry, S.F. Preparation of fatty acid solutions exerts significant impact on experimental outcomes in cell culture models of lipotoxicity. Biol Methods Protoc 2022, 7, bpab023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidemann, L.; Krüger, A.; Kegel-Hübner, V.; Seehofer, D.; Damm, G. Influence of Genistein on Hepatic Lipid Metabolism in an In Vitro Model of Hepatic Steatosis. Molecules 2021, 26, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingitore, P.; Sasidharan, K.; Ekstrand, M.; Prill, S.; Lindén, D.; Romeo, S. Human Multilineage 3D Spheroids as a Model of Liver Steatosis and Fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redenšek Trampuž, S.; van Riet, S.; Nordling, Å.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M. Mechanisms of 5-HT receptor antagonists in the regulation of fibrosis in a 3D human liver spheroid model. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badmus, O.O.; Hillhouse, S.A.; Anderson, C.D.; Hinds, T.D.; Stec, D.E. Molecular mechanisms of metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD): functional analysis of lipid metabolism pathways. Clin Sci (Lond) 2022, 136, 1347–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangro, P.; de la Torre Aláez, M.; Sangro, B.; D’Avola, D. Metabolic dysfunction–associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD): an update of the recent advances in pharmacological treatment. Journal of Physiology and Biochemistry 2023, 79, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najt, C.P.; Senthivinayagam, S.; Aljazi, M.B.; Fader, K.A.; Olenic, S.D.; Brock, J.R.; Lydic, T.A.; Jones, A.D.; Atshaves, B.P. Liver-specific loss of Perilipin 2 alleviates diet-induced hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2016, 310, G726–G738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doncheva, A.I.; Li, Y.; Khanal, P.; Hjorth, M.; Kolset, S.O.; Norheim, F.A.; Kimmel, A.R.; Dalen, K.T. Altered hepatic lipid droplet morphology and lipid metabolism in fasted Plin2-null mice. Journal of Lipid Research 2023, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiva, A.A.; Raposo, H.F.; Wanschel, A.C.; Nardelli, T.R.; Oliveira, H.C. Apolipoprotein CIII Overexpression-Induced Hypertriglyceridemia Increases Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Association with Inflammation and Cell Death. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 2017, 1838679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeren, J.; Scheja, L. Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease and lipoprotein metabolism. Mol Metab 2021, 50, 101238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, S.K.; Tarzemani, S.; Aghajanzadeh, T.; Kasravi, M.; Hatami, B.; Zali, M.R.; Baghaei, K. Exploring the role of genetic variations in NAFLD: implications for disease pathogenesis and precision medicine approaches. Eur J Med Res 2024, 29, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, E.M.; Rowland, A. A Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model to Predict the Impact of Metabolic Changes Associated with Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease on Drug Exposure. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalasani, N.; Gorski, J.C.; Asghar, M.S.; Asghar, A.; Foresman, B.; Hall, S.D.; Crabb, D.W. Hepatic cytochrome P450 2E1 activity in nondiabetic patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2003, 37, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmegeed, M.A.; Banerjee, A.; Yoo, S.-H.; Jang, S.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Song, B.-J. Critical role of cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) in the development of high fat-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Journal of Hepatology 2012, 57, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljomah, G.; Baker, S.S.; Liu, W.; Kozielski, R.; Oluwole, J.; Lupu, B.; Baker, R.D.; Zhu, L. Induction of CYP2E1 in non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases. Experimental and Molecular Pathology 2015, 99, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruoß, M.; Rebholz, S.; Weimer, M.; Grom-Baumgarten, C.; Athanasopulu, K.; Kemkemer, R.; Käß, H.; Ehnert, S.; Nussler, A.K. Development of Scaffolds with Adjusted Stiffness for Mimicking Disease-Related Alterations of Liver Rigidity. J Funct Biomater 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.S.; Diehl, A.M. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions in the liver. Hepatology 2009, 50, 2007–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.L.; Zhu, R.T.; Sun, Y.L. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in liver fibrosis. Biomed Rep 2016, 4, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, T.; Ueland, T.; Aukrust, P.; Nilsen, D.W.T.; Grundt, H.; Staines, H.; Pönitz, V.; Kontny, F. Procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide is associated with adverse outcome in acute chest pain of suspected coronary origin. Front Cardiovasc Med 2023, 10, 1191055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehlen, N.; Crouchet, E.; Baumert, T.F. Liver Fibrosis: Mechanistic Concepts and Therapeutic Perspectives. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Tian, M.; Pei, Q.; Tan, F.; Pei, H. Extracellular Matrix Stiffness: New Areas Affecting Cell Metabolism. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 631991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gen | Forward/ Reverse sequences |

GenBank accession | Tm[a] (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPRT1 | CCTGGCGTCGTGATTAGTGA CGAGCAAGACGTTCAGTCCT |

NM_000194.2 | 58 |

| PLIN2 | TGAGATGGCAGAGAACGGTG TTTGGCATTGGCAACAATCTGA |

NM_001122.4 | 60 |

| APOC3 | CTCCTTGTTGTTGCCCTCCT GGAACTGAAGCCATCGGTCA |

NM_000040.3 | 56 |

| CYP2C9 | CTGGATGAAGGTGGCAATTT AGATGGATAATGCCCCAGAG |

NM_000771.3 | 59 |

| CYP1A2 | CTCTACAGTTGGTACAGATGGCA AGGTGTTGAGGGCATTCTGG |

NM_000761.3 | 60 |

| CYP2E1 | GACTGTGGCCGACCTGTT ACTACGACTGTGCCCTTGG |

NM_000773.3 | 59 |

| CYP3A4 | ATTCAGCAAGAAGAACAAGGACA TGGTGTTCTCAGGCACAGAT |

NM_017460.5 | 64 |

| CYP27A1 | GTGGACACGACATCCAACAC ATGATCCGGGAGTTTGTGG |

NM_000784.4 | 63 |

| CYP2R1 | TGGAAGCTTTGGAGAGCTGA ATCTCTCCGTACACCTGGCT |

NM_024514.5 3 | 64 |

| SNAIL1 | ACCACTATGCCGCGCTCTT GGTCGTAGGGCTGCTGGAA |

NM_005985.3 | 62 |

| N-Cadherin | TGGAGAACCCCATTGACATT GGATTGCCTTCCATGTCTGT |

NM_001792.3 | 56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).