Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

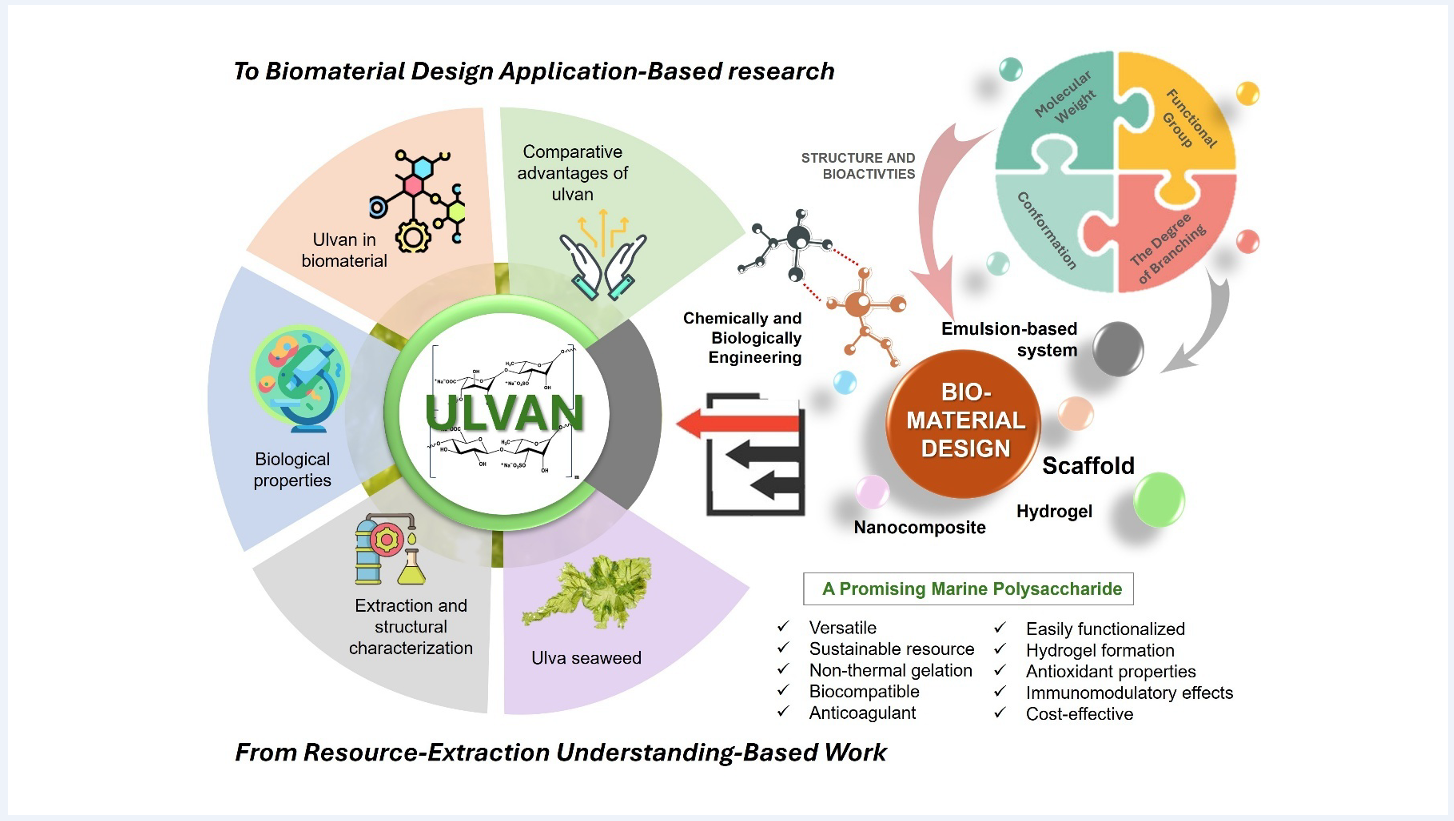

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Ulva, Structural Characteristics, and Extraction of Ulvan

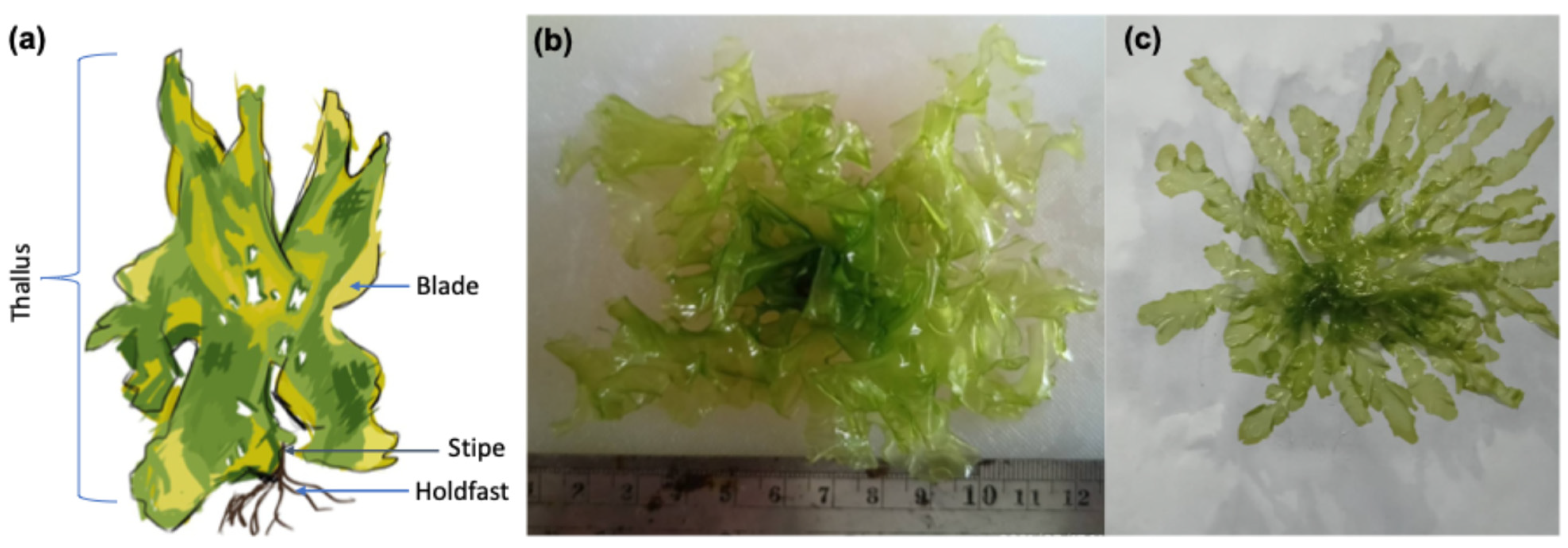

2.1. Ulva

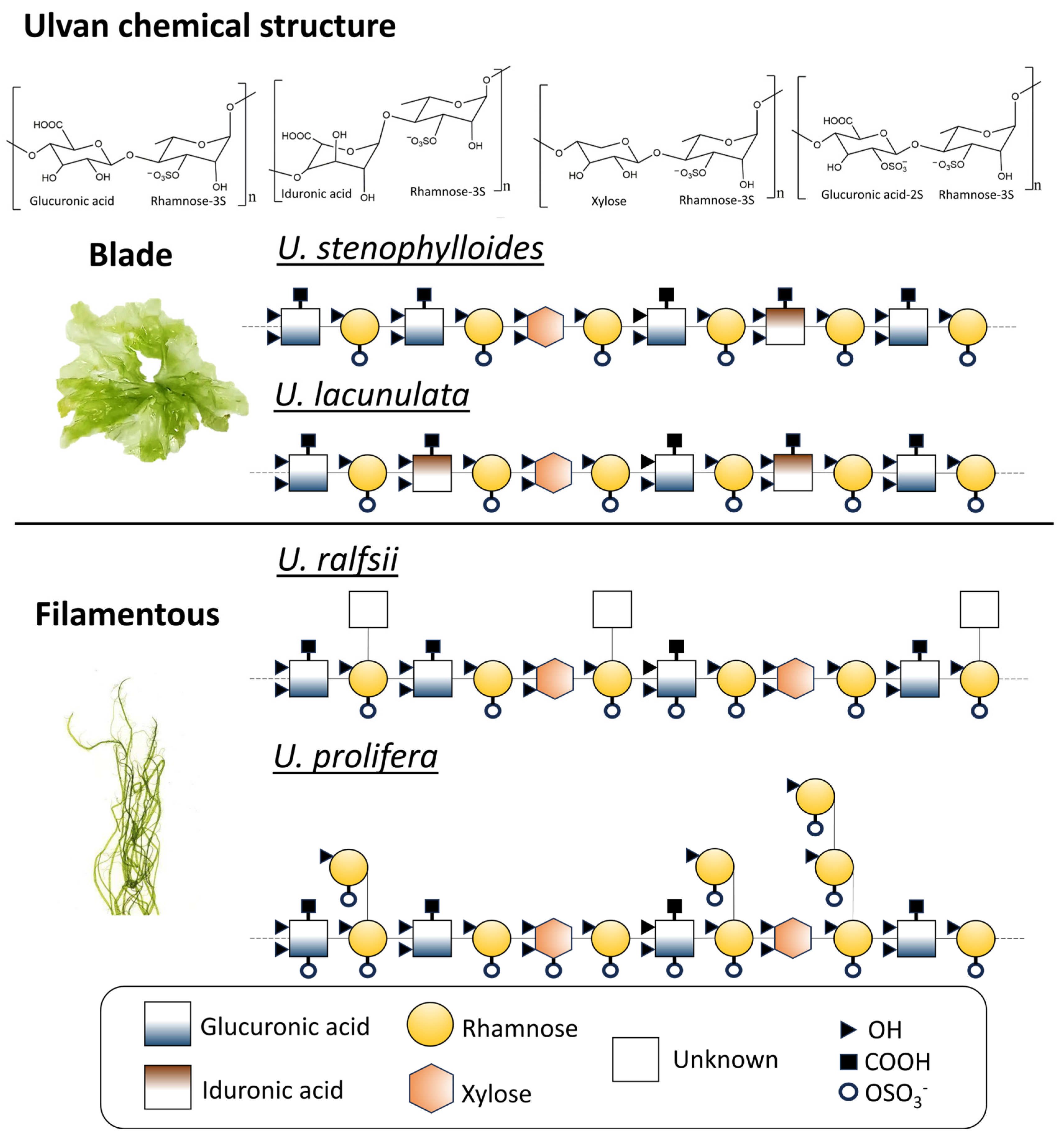

2.2. Ulvan Chemical Structure characteristic

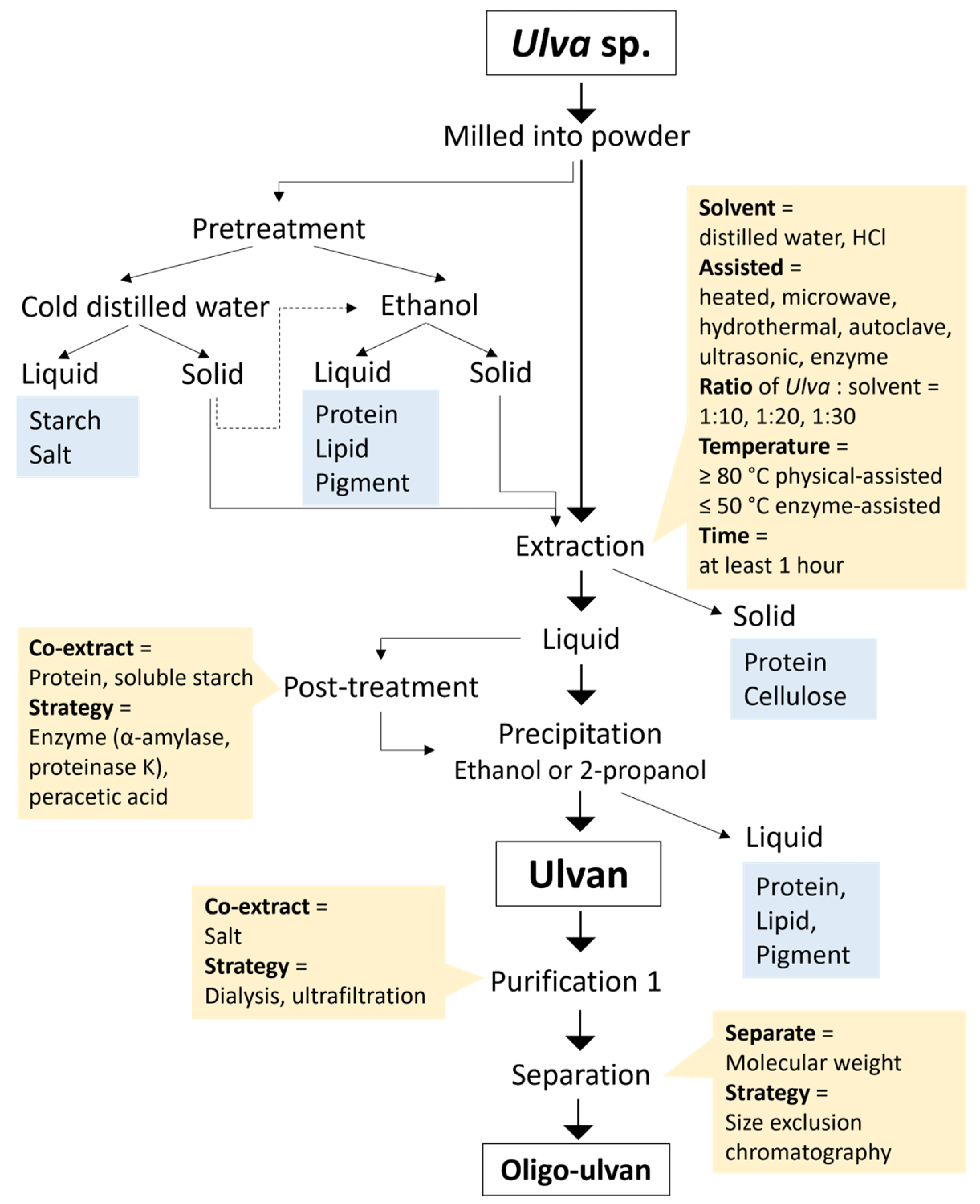

2.3. Ulvan Extraction Strategy

3. Biological Properties of Ulvan

3.1. Biocompatibility Profile

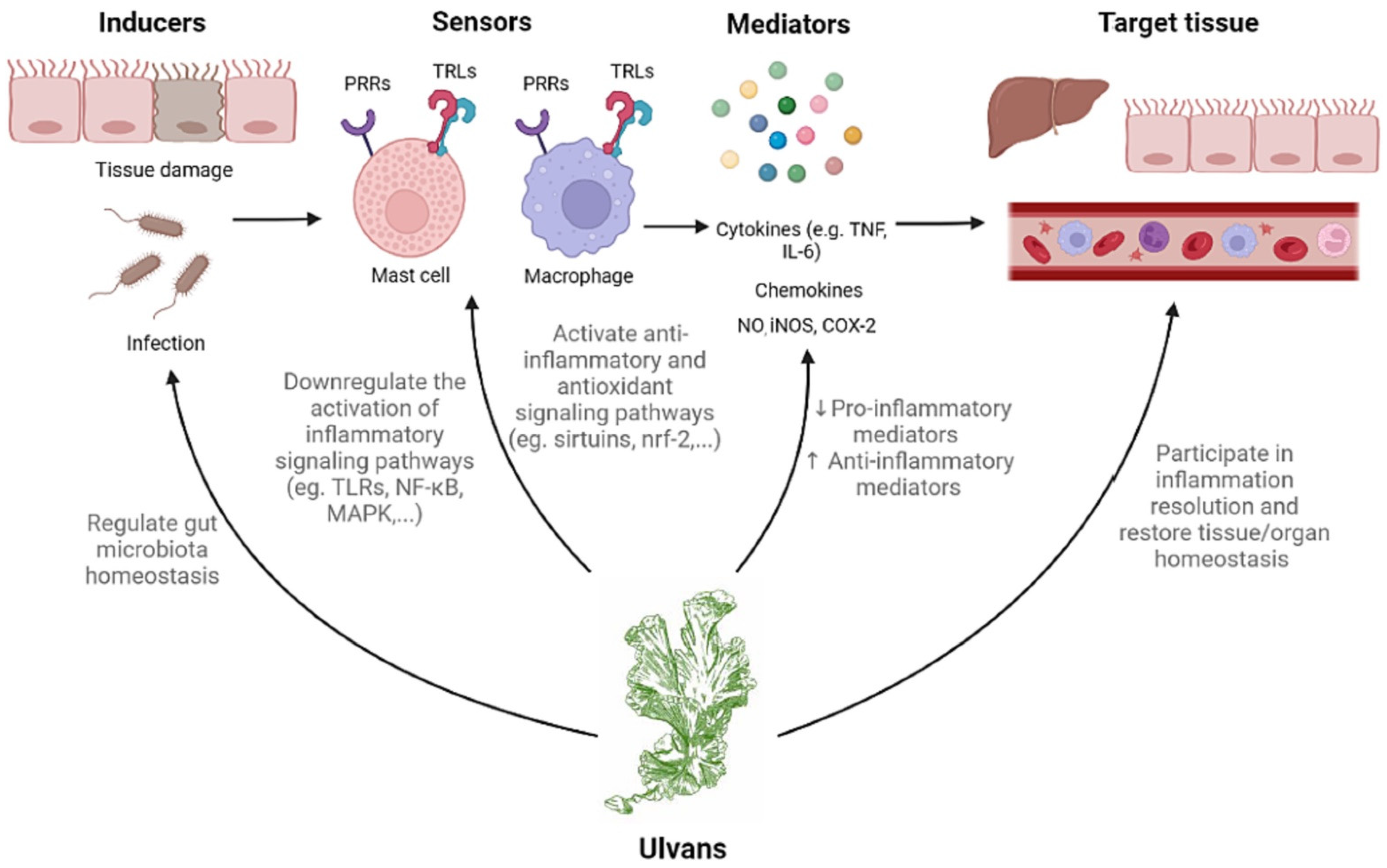

3.2. Immunomodulatory effect

3.3. Anticoagulation Activity

3.4. Antimicrobial Activity

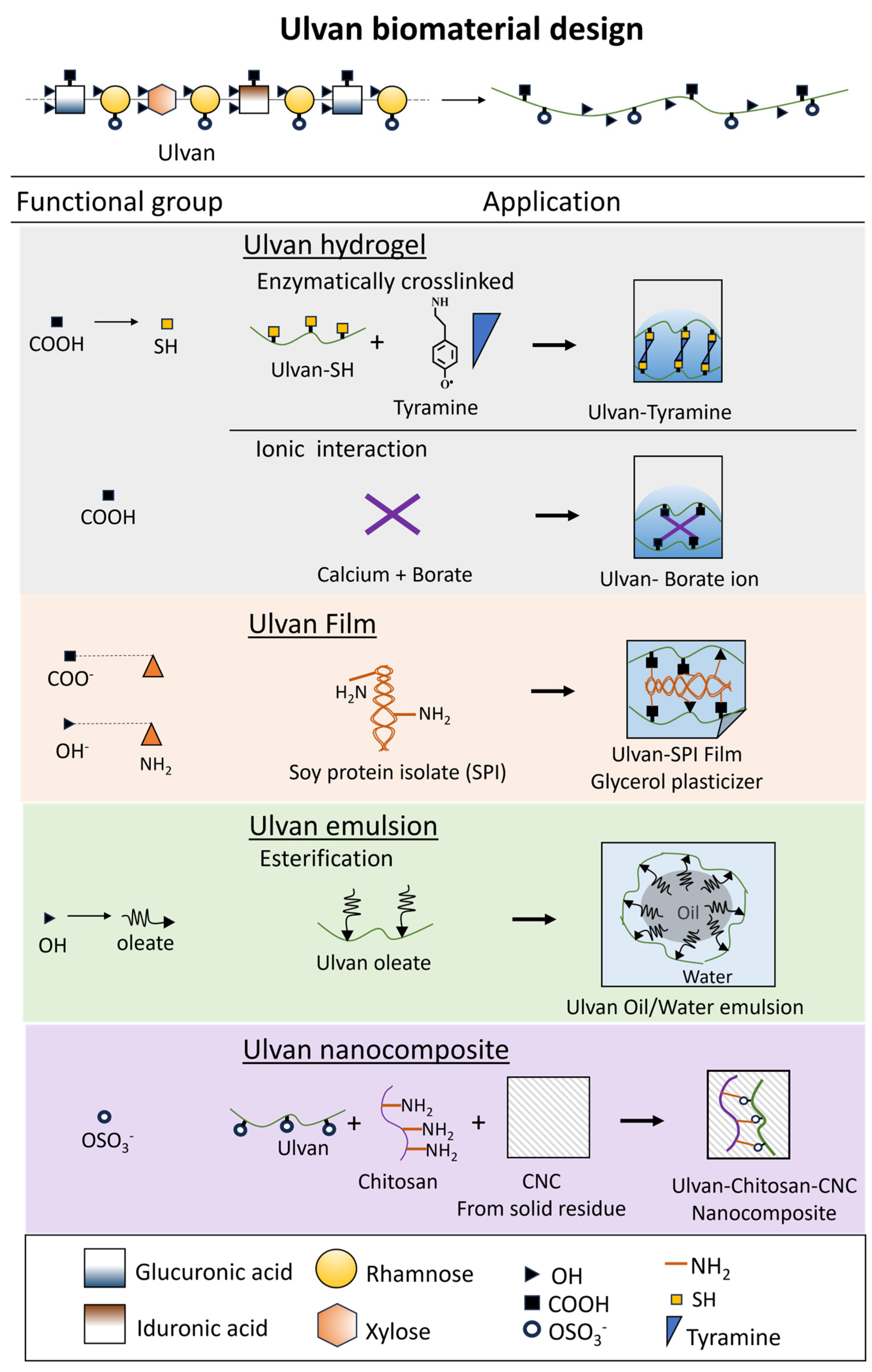

4. Ulvan in Biomaterial Design

4.1. Ulvan-Based Hydrogel

4.2. Ulvan-Based Film

4.3. Ulvan-Based Nanocomposite

4.4. Ulvan-Based Emulsion

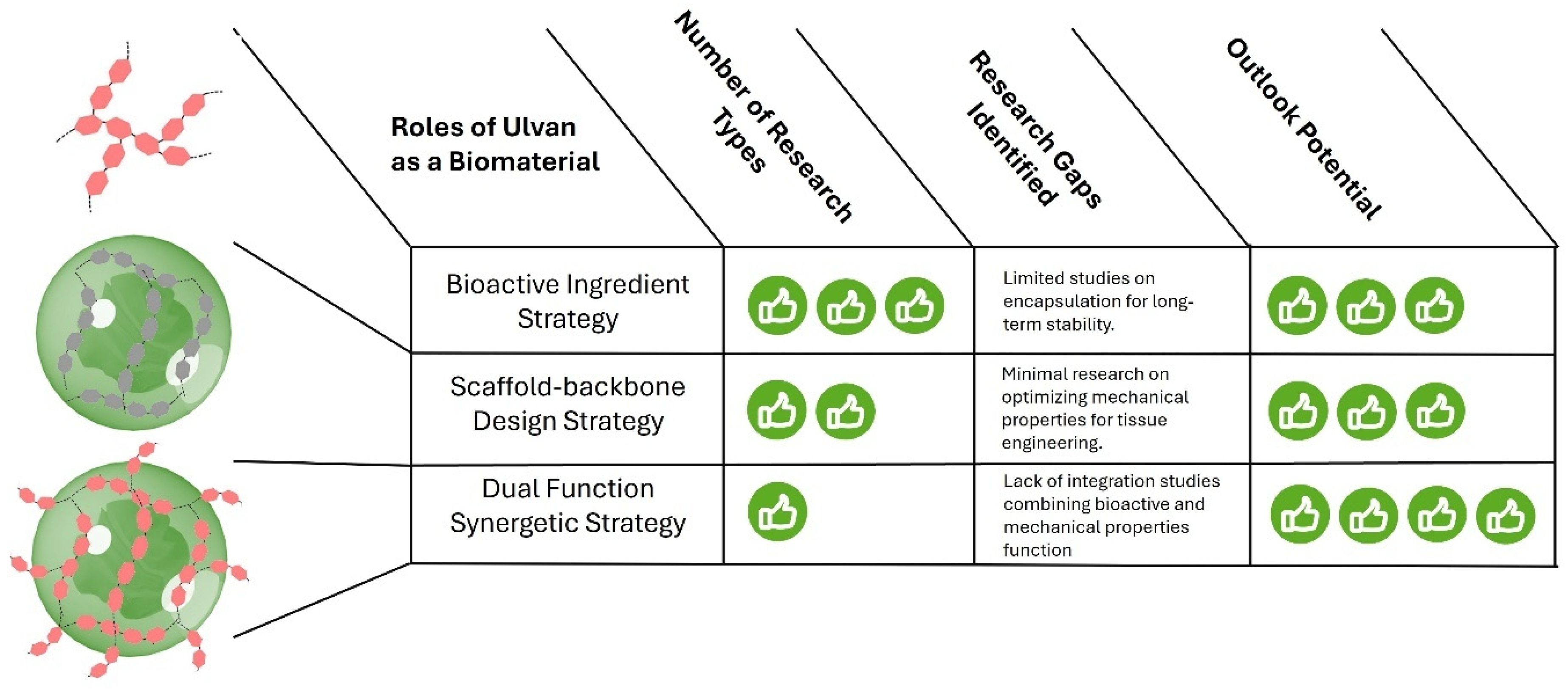

5. Comparative Advantages of Ulvan

- Enhanced Extraction Techniques: Developing cost-effective, standardized methods for high-purity ulvan production.

- Cross-Linking Strategies: Enhancing mechanical properties of ulvan-based materials through innovative cross-linking and composite formation.

- Sustainability Metrics: Incorporating life cycle assessments to establish ulvan as a green alternative to synthetic and traditional polysaccharides.

- Controlled Cultivation: Advancing aquaculture techniques for Ulva species to ensure stable and high-quality ulvan yields independent of seasonal and environmental variations.

- Establishing high-quality ulvan standards depends on its intended use, whether as feed, a food source, or a bioactive compound in the biomedical field.

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DGR | Daily growth rate |

| MWCO | Molecular weight cut-off |

| SEC | Size Exclusion Chromatography |

| IPEC-1 | porcine intestinal epithelial cells |

| TNF- α | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| IL | Interleukin |

| CXCL | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand |

| IgM | Immunoglobulin M |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| iNOS-2 | inducible nitric oxide synthase-2 |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa-B |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| TLR | Toll-like receptors |

| HRP | Horseradish peroxidase |

| Na-CMC | Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose |

| CNC | Cellulose nanocrystals |

| PVA | Polyvinyl alcohol |

References

- Torres, M.D.; Kraan, S.; Domínguez, H. Seaweed Biorefinery. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 2019, 18, 335–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghel, R.S.; Reddy, C.R.K.; Singh, R.P. Seaweed-Based Cellulose: Applications, and Future Perspectives. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 267, 118241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, J.; Aila, M.; Bangwal, D.P.; Kaul, S.; Garg, M.O. Algae Based Biorefinery—How to Make Sense? Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 47, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudke, A.R.; De Andrade, C.J.; Ferreira, S.R.S. Kappaphycus Alvarezii Macroalgae: An Unexplored and Valuable Biomass for Green Biorefinery Conversion. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2020, 103, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, D.J. A Guide to the Seaweed Industry; FAO fisheries technical paper; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, 2003; ISBN 978-92-5-104958-7.

- Cesário, M.T.; Da Fonseca, M.M.R.; Marques, M.M.; De Almeida, M.C.M.D. Marine Algal Carbohydrates as Carbon Sources for the Production of Biochemicals and Biomaterials. Biotechnology Advances 2018, 36, 798–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhou, D.; Luo, G.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J. Macroalgae for Biofuels Production: Progress and Perspectives. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 47, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.M.; Wu, J.; Xiao, X.; Bruhn, A.; Krause-Jensen, D. Can Seaweed Farming Play a Role in Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation? Front. Mar. Sci. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandra, T.V.; Hebbale, D. Bioethanol from Macroalgae: Prospects and Challenges. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 117, 109479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, F.; Tarbuck, P.; Macreadie, P.I. Seaweed Afforestation at Large-Scales Exclusively for Carbon Sequestration: Critical Assessment of Risks, Viability and the State of Knowledge. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1015612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uju; Wijayanta, A.T.; Goto, M.; Kamiya, N. Great Potency of Seaweed Waste Biomass from the Carrageenan Industry for Bioethanol Production by Peracetic Acid–Ionic Liquid Pretreatment. Biomass and Bioenergy 2015, 81, 63–69. [CrossRef]

- Uju; Wijayanta, A.T.; Goto, M.; Kamiya, N. High Yield Hydrolysis of Seaweed-Waste Biomass Using Peracetic Acid and Ionic Liquid Treatments.; Jatinangor, Indonesia, 2018; p. 020004.

- Uju; Goto, M.; Kamiya, N. Powerful Peracetic Acid–Ionic Liquid Pretreatment Process for the Efficient Chemical Hydrolysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Bioresource Technology 2016, 214, 487–495. [CrossRef]

- Sultana, F.; Wahab, M.A.; Nahiduzzaman, M.; Mohiuddin, M.; Iqbal, M.Z.; Shakil, A.; Mamun, A.-A.; Khan, M.S.R.; Wong, L.; Asaduzzaman, M. Seaweed Farming for Food and Nutritional Security, Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation, and Women Empowerment: A Review. Aquaculture and Fisheries 2023, 8, 463–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.A.; Lim, S.-R.; Kim, Y.; Park, J.M. Potentials of Macroalgae as Feedstocks for Biorefinery. Bioresource Technology 2013, 135, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Viñas, M.; Flórez-Fernández, N.; Torres, M.D.; Domínguez, H. Successful Approaches for a Red Seaweed Biorefinery. Marine Drugs 2019, 17, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiraoka, M. Massive Ulva Green Tides Caused by Inhibition of Biomass Allocation to Sporulation. Plants 2021, 10, 2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantri, V.A.; Kazi, M.A.; Balar, N.B.; Gupta, V.; Gajaria, T. Concise Review of Green Algal Genus Ulva Linnaeus. J Appl Phycol 2020, 32, 2725–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankiewicz, R.; Łęska, B.; Messyasz, B.; Fabrowska, J.; Sołoducha, M.; Pikosz, M. First Isolation of Polysaccharidic Ulvans from the Cell Walls of Freshwater Algae. Algal Research 2016, 19, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, H.; De Saeger, J.; Depuydt, S.; Asselman, J.; Janssen, C.; Heynderickx, P.M.; Wu, D.; Ronsse, F.; Tack, F.M.G.; et al. Harnessing Green Tide Ulva Biomass for Carbon Dioxide Sequestration. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 2024, 23, 1041–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, P.; Li, H.; Li, G.; Liu, J.; Jiao, F.; Zhang, J.; Huo, Y.; Shi, X.; Su, R.; et al. Ulva Prolifera Green-Tide Outbreaks and Their Environmental Impact in the Yellow Sea, China. Natl Sci Rev 2019, 6, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, D.; Fu, M.; Yuan, C.; Yan, T. Harmful Macroalgal Blooms (HMBs) in China’s Coastal Water: Green and Golden Tides. Harmful Algae 2021, 107, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, N.; Gupta, V.; Reddy, C.R.K.; Jha, B. Enzymatic Hydrolysis and Production of Bioethanol from Common Macrophytic Green Alga Ulva Fasciata Delile. Bioresource Technology 2013, 150, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortes, M.D.; Lüning, K. Growth Rates of North Sea Macroalgae in Relation to Temperature, Irradiance and Photoperiod. Helgolander Meeresunters 1980, 34, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemodanov, A.; Robin, A.; Jinjikhashvily, G.; Yitzhak, D.; Liberzon, A.; Israel, A.; Golberg, A. Feasibility Study of Ulva Sp. (Chlorophyta) Intensive Cultivation in a Coastal Area of the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. Biofuels Bioprod Bioref 2019, 13, 864–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaweeds and Microalgae: An Overview for Unlocking Their Potential in Global Aquaculture Development; FAO, 2021; ISBN 978-92-5-134710-2.

- Pari, R.F.; Uju; Wijayanta, A.T.; Ramadhan, W.; Hardiningtyas, S.D.; Kurnia, K.A.; Firmansyah, M.L.; Hana, A.; Abrar, M.N.; Wakabayashi, R.; et al. Prospecting Ulva Lactuca Seaweed in Java Island, Indonesia, as a Candidate Resource for Industrial Applications. Fish Sci 2024, 90, 795–808. [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, N.; Baghel, R.S.; Bothwell, J.; Gupta, V.; Reddy, C.R.K.; Lali, A.M.; Jha, B. An Integrated Process for the Extraction of Fuel and Chemicals from Marine Macroalgal Biomass. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 30728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Gendy, N.Sh.; Nassar, H.N.; Ismail, A.R.; Ali, H.R.; Ali, B.A.; Abdelsalam, K.M.; Mubarak, M. A Fully Integrated Biorefinery Process for the Valorization of Ulva Fasciata into Different Green and Sustainable Value-Added Products. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, M.; Chemodanov, A.; Gottlieb, R.; Kazir, M.; Nahor, O.; Gozin, M.; Israel, A.; Livney, Y.D.; Golberg, A. Starch from the Sea: The Green Macroalga Ulva Ohnoi as a Potential Source for Sustainable Starch Production in the Marine Biorefinery. Algal Research 2019, 37, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cindana Mo’o, F.R.; Wilar, G.; Devkota, H.P.; Wathoni, N. Ulvan, a Polysaccharide from Macroalga Ulva Sp.: A Review of Chemistry, Biological Activities and Potential for Food and Biomedical Applications. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, A.; Fernando, D.; Ståhl, K.; Daniel, G.; Mensah, M.; Meyer, A.S. Cell Wall Configuration and Ultrastructure of Cellulose Crystals in Green Seaweeds. Cellulose 2021, 28, 2763–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilavtepe, M.; Sargin, S.; Celiktas, M.S.; Yesil-Celiktas, O. An Integrated Process for Conversion of Zostera Marina Residues to Bioethanol. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2012, 68, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajaria, T.K.; Suthar, P.; Baghel, R.S.; Balar, N.B.; Sharnagat, P.; Mantri, V.A.; Reddy, C.R.K. Integration of Protein Extraction with a Stream of Byproducts from Marine Macroalgae: A Model Forms the Basis for Marine Bioeconomy. Bioresource Technology 2017, 243, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikker, P.; Van Krimpen, M.M.; Van Wikselaar, P.; Houweling-Tan, B.; Scaccia, N.; Van Hal, J.W.; Huijgen, W.J.J.; Cone, J.W.; López-Contreras, A.M. Biorefinery of the Green Seaweed Ulva Lactuca to Produce Animal Feed, Chemicals and Biofuels. J Appl Phycol 2016, 28, 3511–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidgell, J.T.; Magnusson, M.; de Nys, R.; Glasson, C.R.K. Ulvan: A Systematic Review of Extraction, Composition and Function. Algal Research 2019, 39, 101422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Wu, X.; Lu, F.; Liu, F. Sustainable Production of Ulva Oligosaccharides via Enzymatic Hydrolysis: A Review on Ulvan Lyase. Foods 2024, 13, 2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidgell, J.T.; Glasson, C.R.K.; Magnusson, M.; Sims, I.M.; Hinkley, S.F.R.; de Nys, R.; Carnachan, S.M. Ulvans Are Not Equal - Linkage and Substitution Patterns in Ulvan Polysaccharides Differ with Ulva Morphology. Carbohydrate Polymers 2024, 333, 121962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Ai, C.; Yao, H.; Zhao, C.; Xiang, C.; Hong, T.; Xiao, J. Guideline for the Extraction, Isolation, Purification, and Structural Characterization of Polysaccharides from Natural Resources. eFood 2022, 3, e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.F. Biorefinery Concept. In Biorefineries: Targeting Energy, High Value Products and Waste Valorisation; Rabaçal, M., Ferreira, A.F., Silva, C.A.M., Costa, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 1–20 ISBN 978-3-319-48288-0.

- Magnusson, M.; Carl, C.; Mata, L.; de Nys, R.; Paul, N.A. Seaweed Salt from Ulva: A Novel First Step in a Cascading Biorefinery Model. Algal Research 2016, 16, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.; Fernandes, A.P.M.; Torres-Acosta, M.A.; Collén, P.N.; Abreu, M.H.; Ventura, S.P.M. Extraction of Chlorophyll from Wild and Farmed Ulva Spp. Using Aqueous Solutions of Ionic Liquids. Separation and Purification Technology 2021, 254, 117589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.; Oliveira, R.; Coutinho, J.A.P.; Faustino, M.A.F.; Neves, M.G.P.M.S.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Ventura, S.P.M. Recovery of Pigments from Ulva Rigida. Separation and Purification Technology 2021, 255, 117723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasson, C.R.K.; Sims, I.M.; Carnachan, S.M.; de Nys, R.; Magnusson, M. A Cascading Biorefinery Process Targeting Sulfated Polysaccharides (Ulvan) from Ulva Ohnoi. Algal Research 2017, 27, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, M.; Fathi, M.; Jahanbin, K.; Taghdir, M.; Abbaszadeh, S. Optimization of Ultrasonic-Assisted Hot Acidic Solvent Extraction of Ulvan from Ulva Intestinalis of the Persian Gulf: Evaluation of Structural, Techno-Functional, and Bioactivity Properties. Food Hydrocolloids 2023, 142, 108837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappou, S.; Dardavila, M.M.; Savvidou, M.G.; Louli, V.; Magoulas, K.; Voutsas, E. Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Ulva Lactuca. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidara, M.; Yaich, H.; Amor, I.B.; Fakhfakh, J.; Gargouri, J.; Lassoued, S.; Blecker, C.; Richel, A.; Attia, H.; Garna, H. Effect of Extraction Procedures on the Chemical Structure, Antitumor and Anticoagulant Properties of Ulvan from Ulva Lactuca of Tunisia Coast. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 253, 117283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan, W.; Uju, U.; Hardiningtyas, S.D.; Pari, R.F.; Nurhayati, N.; Sevica, D. Ekstraksi Polisakarida Ulvan Dari Rumput Laut Ulva Lactuca Berbantu Gelombang Ultrasonik Pada Suhu Rendah: Ultrasonic Wave Assisted Extraction of Ulvan Polysaccharide from Ulva Seaweed at Low Temperature. JPHPI 2022, 25, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlström, N.; Nylander, F.; Malmhäll-Bah, E.; Sjövold, K.; Edlund, U.; Westman, G.; Albers, E. Composition and Structure of Cell Wall Ulvans Recovered from Ulva Spp. along the Swedish West Coast. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 233, 115852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, C.; Martins, P.L.; Duarte, L.C.; Oliveira, A.C.; Carvalheiro, F. Development of an Innovative Macroalgae Biorefinery: Oligosaccharides as Pivotal Compounds. Fuel 2022, 320, 123780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Iglesias, P.; Baltrusch, K.L.; Díaz-Reinoso, B.; López-Álvarez, M.; Novoa-Carballal, R.; González, P.; González-Novoa, A.; Rodríguez-Montes, A.; Kennes, C.; Veiga, M.C.; et al. Hydrothermal Extraction of Ulvans from Ulva Spp. in a Biorefinery Approach. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 951, 175654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, M.; Badr, H.A. Optimization of Oxalic Acid Treatment for Ulvan Extraction from Ulva Linza Biomass and Its Potential Application as Fe(III) Chelator. Algal Research 2024, 80, 103536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moawad, M.N.; El-Sayed, A.A.M.; Abd El Latif, H.H.; El-Naggar, N.A.; Shams El-Din, N.G.; Tadros, H.R.Z. Chemical Characterization and Biochemical Activity of Polysaccharides Isolated from Egyptian Ulva Fasciata Delile. Oceanologia 2022, 64, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikandan, N.A.; Lens, P.N.L. Green Extraction and Esterification of Marine Polysaccharide (Ulvan) from Green Macroalgae Ulva Sp. Using Citric Acid for Hydrogel Preparation. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 366, 132952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlström, N.; Steinhagen, S.; Toth, G.; Pavia, H.; Edlund, U. Ulvan Dialdehyde-Gelatin Hydrogels for Removal of Heavy Metals and Methylene Blue from Aqueous Solution. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 249, 116841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan, W.; Alamsyah, A.; Uju; Hardiningtyas, S.D.; Pari, R.F.; Wakabayashi, R.; Kamiya, N.; Goto, M. Facilitating Ulvan Extraction from Ulva Lactuca via Deep Eutectic Solvent and Peracetic Acid Treatment. ASEAN Journal of Chemical Engineering 2024, 24, 90–101ng Ulvan Extraction from Ulva Lactuca via Deep Eutectic Solvent and Peracetic Acid Treatment. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zeng, W.; Gan, J.; Li, Y.; Pan, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, H. Physicochemical Properties and Anti-Oxidation Activities of Ulvan from Ulva Pertusa Kjellm. Algal Research 2021, 55, 102269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, J.; Flórez-Fernández, N.; Domínguez, H.; Torres, M.D. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Ulva Spp. Including a Stage of Selective Coagulation of Ulvan Stimulated by a Bio-Ionic Liquid. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 225, 952–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaich, H.; Garna, H.; Besbes, S.; Paquot, M.; Blecker, C.; Attia, H. Effect of Extraction Conditions on the Yield and Purity of Ulvan Extracted from Ulva Lactuca. Food Hydrocolloids 2013, 31, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournière, M.; Latire, T.; Lang, M.; Terme, N.; Bourgougnon, N.; Bedoux, G. Production of Active Poly- and Oligosaccharidic Fractions from Ulva Sp. by Combining Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE) and Depolymerization. Metabolites 2019, 9, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pengzhan, Y.; Quanbin, Z.; Hong, Z.; Xizhen, N.; Zhien, L. Preparation of Polysaccharides in Different Molecular Weights fromUlva Pertusa Kjellm (Chorophyta). Chin. J. Ocean. Limnol. 2004, 22, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaulneau, V.; Lafitte, C.; Corio-Costet, M.-F.; Stadnik, M.J.; Salamagne, S.; Briand, X.; Esquerré-Tugayé, M.-T.; Dumas, B. An Ulva Armoricana Extract Protects Plants against Three Powdery Mildew Pathogens. Eur J Plant Pathol 2011, 131, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.; Sousa, R.A.; Reis, R.L. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assessment of Ulvan, a Polysaccharide Extracted from Green Algae. Phytotherapy Research 2013, 27, 1143–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, A.A.A.; Alves, A.; Nunes, C.; Coimbra, M.A.; Pires, R.A.; Reis, R.L. Carboxymethylation of Ulvan and Chitosan and Their Use as Polymeric Components of Bone Cements. Acta Biomaterialia 2013, 9, 9086–9097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabarsa, M.; You, S.; Dabaghian, E.H.; Surayot, U. Water-Soluble Polysaccharides from Ulva Intestinalis : Molecular Properties, Structural Elucidation and Immunomodulatory Activities. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis 2018, 26, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabarsa, M.; Han, J.H.; Kim, C.Y.; You, S.G. Molecular Characteristics and Immunomodulatory Activities of Water-Soluble Sulfated Polysaccharides from Ulva Pertusa. Journal of Medicinal Food 2012, 15, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Yang, C.; Kim, S.M.; You, S. Molecular Characterization and Biological Activities of Watersoluble Sulfated Polysaccharides from Enteromorpha Prolifera. Food Sci Biotechnol 2010, 19, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peasura, N.; Laohakunjit, N.; Kerdchoechuen, O.; Vongsawasdi, P.; Chao, L.K. Assessment of Biochemical and Immunomodulatory Activity of Sulphated Polysaccharides from Ulva Intestinalis. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2016, 91, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berri, M.; Slugocki, C.; Olivier, M.; Helloin, E.; Jacques, I.; Salmon, H.; Demais, H.; Le Goff, M.; Collen, P.N. Marine-Sulfated Polysaccharides Extract of Ulva Armoricana Green Algae Exhibits an Antimicrobial Activity and Stimulates Cytokine Expression by Intestinal Epithelial Cells. J Appl Phycol 2016, 28, 2999–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berri, M.; Olivier, M.; Holbert, S.; Dupont, J.; Demais, H.; Le Goff, M.; Collen, P.N. Ulvan from Ulva Armoricana (Chlorophyta) Activates the PI3K/Akt Signalling Pathway via TLR4 to Induce Intestinal Cytokine Production. Algal Research 2017, 28, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimse, S.B.; Pal, D. Free Radicals, Natural Antioxidants, and Their Reaction Mechanisms. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 27986–28006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maray, S.O.; Abdel-Kareem, M.S.M.; Mabrouk, M.E.M.; El-Halmouch, Y.; Makhlof, M.E.M. In Vitro Assessment of Antiviral, Antimicrobial, Antioxidant and Anticancer Activities of Ulvan Extracted from the Green Seaweed Ulva Lactuca. Thalassas 2023, 39, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonthron-Sénécheau, C.; Kaiser, M.; Devambez, I.; Vastel, A.; Mussio, I.; Rusig, A.-M. Antiprotozoal Activities of Organic Extracts from French Marine Seaweeds. Marine Drugs 2011, 9, 922–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spavieri, J.; Allmendinger, A.; Kaiser, M.; Itoe, M.; Blunden, G.; Mota, M.; Tasdemir, D. Assessment of Dual Life Stage Antiplasmodial Activity of British Seaweeds. Marine Drugs 2013, 11, 4019–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botta, A.; Martínez, V.; Mitjans, M.; Balboa, E.; Conde, E.; Vinardell, M.P. Erythrocytes and Cell Line-Based Assays to Evaluate the Cytoprotective Activity of Antioxidant Components Obtained from Natural Sources. Toxicology in Vitro 2014, 28, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán-Santibañez, K.; Cruz-Suárez, L.E.; Ricque-Marie, D.; Robledo, D.; Freile-Pelegrín, Y.; Peña-Hernández, M.A.; Rodríguez-Padilla, C.; Trejo-Avila, L.M. Synergistic Effects of Sulfated Polysaccharides from Mexican Seaweeds against Measles Virus. BioMed Research International 2016, 2016, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Araújo, I.W.F.; Rodrigues, J.A.G.; Quinderé, A.L.G.; Silva, J.D.F.T.; Maciel, G.D.F.; Ribeiro, N.A.; De Sousa Oliveira Vanderlei, E.; Ribeiro, K.A.; Chaves, H.V.; Pereira, K.M.A.; et al. Analgesic and Anti-Inflammatory Actions on Bradykinin Route of a Polysulfated Fraction from Alga Ulva Lactuca. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2016, 92, 820–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Li, X.; Li, T.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, L.; Wu, M.; Zhang, L. Characterization and Anti-Tumor Activity of Alkali-Extracted Polysaccharide from Enteromorpha Intestinalis. International Immunopharmacology 2009, 9, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das Chagas Faustino Alves, M.G.; Dore, C.M.P.G.; Castro, A.J.G.; Do Nascimento, M.S.; Cruz, A.K.M.; Soriano, E.M.; Benevides, N.M.B.; Leite, E.L. Antioxidant, Cytotoxic and Hemolytic Effects of Sulfated Galactans from Edible Red Alga Hypnea Musciformis. J Appl Phycol 2012, 24, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Briseño, J.; Cruz-Suarez, L.; Sassi, J.-F.; Ricque-Marie, D.; Zapata-Benavides, P.; Mendoza-Gamboa, E.; Rodríguez-Padilla, C.; Trejo-Avila, L. Sulphated Polysaccharides from Ulva Clathrata and Cladosiphon Okamuranus Seaweeds Both Inhibit Viral Attachment/Entry and Cell-Cell Fusion, in NDV Infection. Marine Drugs 2015, 13, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, N.; Ray, S.; Espada, S.F.; Bomfim, W.A.; Ray, B.; Faccin-Galhardi, L.C.; Linhares, R.E.C.; Nozawa, C. Green Seaweed Enteromorpha Compressa ( Chlorophyta, Ulvaceae ) Derived Sulphated Polysaccharides Inhibit Herpes Simplex Virus. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2017, 102, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-K.; Cho, M.L.; Karnjanapratum, S.; Shin, I.-S.; You, S.G. In Vitro and in Vivo Immunomodulatory Activity of Sulfated Polysaccharides from Enteromorpha Prolifera. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2011, 49, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husemann, E. Chemistry and Enzymology of Marine Algal Polysaccharides. Von E. Percival Und R. H. McDowell. Academic Press, London-New York 1967. 1. Aufl., XII, 219 S., Mehrere Abb. u. Tab., Geb. 60s. Angewandte Chemie 1968, 80, 856–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Márquez, J.; Moreira, B.R.; Valverde-Guillén, P.; Latorre-Redoli, S.; Caneda-Santiago, C.T.; Acién, G.; Martínez-Manzanares, E.; Marí-Beffa, M.; Abdala-Díaz, R.T. In Vitro and In Vivo Effects of Ulvan Polysaccharides from Ulva Rigida. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefpour, P.; Ni, K.; Irvine, D.J. Targeted Modulation of Immune Cells and Tissues Using Engineered Biomaterials. Nat Rev Bioeng 2023, 1, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou El Azm, N.; Fleita, D.; Rifaat, D.; Mpingirika, E.Z.; Amleh, A.; El-Sayed, M.M.H. Production of Bioactive Compounds from the Sulfated Polysaccharides Extracts of Ulva Lactuca: Post-Extraction Enzymatic Hydrolysis Followed by Ion-Exchange Chromatographic Fractionation. Molecules 2019, 24, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishwarya, R.; Vaseeharan, B.; Kalyani, S.; Banumathi, B.; Govindarajan, M.; Alharbi, N.S.; Kadaikunnan, S.; Al-anbr, M.N.; Khaled, J.M.; Benelli, G. Facile Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Using Ulva Lactuca Seaweed Extract and Evaluation of Their Photocatalytic, Antibiofilm and Insecticidal Activity. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 2018, 178, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby M, S.; Amin H, H. Potential Using of Ulvan Polysaccharide from Ulva Lactuca as a Prebiotic in Synbiotic Yogurt Production. J Prob Health 2019, 07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Mano, J.F.; Sousa, R.A.; Reis, R.L. PDLLA Enriched with Ulvan Particles as a Novel 3D Porous Scaffold Targeted for Bone Engineering. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2012, 65, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vane, J.; Botting, R. Inflammation and the Mechanism of Action of Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. FASEB J 1987, 1, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estevinho, B.N.; Rocha, F.; Santos, L.; Alves, A. Microencapsulation with Chitosan by Spray Drying for Industry Applications – A Review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2013, 31, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, J.; Lowe, B.; Anil, S.; Manivasagan, P.; Kheraif, A.A.A.; Kang, K.; Kim, S. Seaweed Polysaccharides and Their Potential Biomedical Applications. Starch Stärke 2015, 67, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, R.; Piazzon, M.C.; Zarra, I.; Leiro, J.; Noya, M.; Lamas, J. Stimulation of Turbot Phagocytes by Ulva Rigida C. Agardh Polysaccharides. Aquaculture 2006, 254, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Díaz, C.; Coste, O.; Malta, E. Polymer Chitosan Nanoparticles Functionalized with Ulva Ohnoi Extracts Boost in Vitro Ulvan Immunostimulant Effect in Solea Senegalensis Macrophages. Algal Research 2017, 26, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, G.; Pei, D.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Di, D. Polysaccharides from Enteromorpha Prolifera Enhance the Immunity of Normal Mice. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2014, 64, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zhang, S.; Song, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ling, Q.; Hoffmann, P.R.; Li, J.; Chen, T.; Zheng, W.; Huang, Z. Selenium Nanoparticles Decorated with Ulva Lactuca Polysaccharide Potentially Attenuate Colitis by Inhibiting NF-κB Mediated Hyper Inflammation. J Nanobiotechnol 2017, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.-K.; Bong, M.-H.; Park, J.-C.; Moon, H.-K.; Kim, D.-W.; Lee, S.-C.; Lee, J.-H. Antioxidant and Immunomodulatory Effects of Ulva Pertusa Kjellman on Broiler Chickens. Journal of Animal Science and Technology 2011, 53, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiro, J.M.; Castro, R.; Arranz, J.A.; Lamas, J. Immunomodulating Activities of Acidic Sulphated Polysaccharides Obtained from the Seaweed Ulva Rigida C. Agardh. International Immunopharmacology 2007, 7, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez-Fernández, N.; Rodríguez-Coello, A.; Latire, T.; Bourgougnon, N.; Torres, M.D.; Buján, M.; Muíños, A.; Muiños, A.; Meijide-Faílde, R.; Blanco, F.J.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Ulvan. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 253, 126936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanmarco, L.M.; Chao, C.-C.; Wang, Y.-C.; Kenison, J.E.; Li, Z.; Rone, J.M.; Rejano-Gordillo, C.M.; Polonio, C.M.; Gutierrez-Vazquez, C.; Piester, G.; et al. Identification of Environmental Factors That Promote Intestinal Inflammation. Nature 2022, 611, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, I.; Manzoor, Z.; Koo, J.-E.; Kim, J.-E.; Byeon, S.-H.; Yoo, E.-S.; Kang, H.-K.; Hyun, J.-W.; Lee, N.-H.; Koh, Y.-S. 3-Hydroxy-4,7-Megastigmadien-9-One, Isolated from Ulva Pertusa, Attenuates TLR9-Mediated Inflammatory Response by down-Regulating Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase and NF-κB Pathways. Pharmaceutical Biology 2017, 55, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cian, R.E.; Hernández-Chirlaque, C.; Gámez-Belmonte, R.; Drago, S.R.; Sánchez De Medina, F.; Martínez-Augustin, O. Green Alga Ulva Spp. Hydrolysates and Their Peptide Fractions Regulate Cytokine Production in Splenic Macrophages and Lymphocytes Involving the TLR4-NFκB/MAPK Pathways. Marine Drugs 2018, 16, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Duan, X.; Wassie, T.; Wang, H.; Li, T.; Xie, C.; Wu, X. Enteromorpha Prolifera Polysaccharide–Zinc Complex Modulates the Immune Response and Alleviates LPS-Induced Intestinal Inflammation via Inhibiting the TLR4/NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ouyang, Y.; Chen, R.; Wang, M.; Ai, C.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Sarker, Md.M.R.; Chen, X.; Zhao, C. Nutraceutical Potentials of Algal Ulvan for Healthy Aging. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 194, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Famta, P.; Shahrukh, S.; Jain, N.; Vambhurkar, G.; Srinivasarao, D.A.; Raghuvanshi, R.S.; Singh, S.B.; Srivastava, S. Multifaceted Applications of Ulvan Polysaccharides: Insights on Biopharmaceutical Avenues. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 234, 123669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Zhang, Y.; Niu, K.; Liang, X.; Wang, H.; Shan, J.; Wu, X. Enteromorpha Polysaccharide-Zinc Replacing Prophylactic Antibiotics Contributes to Improving Gut Health of Weaned Piglets. Animal Nutrition 2021, 7, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlodarska, M.; Kostic, A.D.; Xavier, R.J. An Integrative View of Microbiome-Host Interactions in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Cell Host & Microbe 2015, 17, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, G.A.; Hennet, T. Mechanisms and Consequences of Intestinal Dysbiosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 2959–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbet, M.B.; Sefton, M.V. Biomaterial-Associated Thrombosis: Roles of Coagulation Factors, Complement, Platelets and Leukocytes. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 5681–5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, H.; Huang, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, S. Antihyperlipidemic Activity of High Sulfate Content Derivative of Polysaccharide Extracted from Ulva Pertusa (Chlorophyta). Carbohydrate Polymers 2012, 87, 1637–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrien, A.; Dufour, D.; Baudouin, S.; Maugard, T.; Bridiau, N. Evaluation of the Anticoagulant Potential of Polysaccharide-Rich Fractions Extracted from Macroalgae. Natural Product Research 2017, 31, 2126–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmugam, M.; Ramavat, B.K.; Mody, K.; Oza, R.; Tewari, A. Distribution of Heparinoid-Active Sulphated Polysaccharides in Some Indian Marine Green Algae. Indian Journal of Marine Sciences 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Chi, Y.; Hwang, H.; Wang, P. Directional Preparation of Anticoagulant-Active Sulfated Polysaccharides from Enteromorpha Prolifera Using Artificial Neural Networks. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggio, C.; Pagano, M.; Dottore, A.; Genovese, G.; Morabito, M. Evaluation of Anticoagulant Activity of Two Algal Polysaccharides. Natural Product Research 2016, 30, 1934–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Rivas, G.; Gómez-Gutiérrez, C.M.; Alarcón-Arteaga, G.; Soria-Mercado, I.E.; Ayala-Sánchez, N.E. Screening for Anticoagulant Activity in Marine Algae from the Northwest Mexican Pacific Coast. J Appl Phycol 2011, 23, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.; Zang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H. Sulfated Polysaccharides from Marine Green Algae Ulva Conglobata and Their Anticoagulant Activity. J Appl Phycol 2006, 18, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Mao, W.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, C.; Li, N.; Wang, C. Chemical Characteristics and Anticoagulant Activities of Two Sulfated Polysaccharides from Enteromorpha Linza (Chlorophyta). J. Ocean Univ. China 2013, 12, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, Z.; Zhao, M.; Qi, H. Sulfation, Anticoagulant and Antioxidant Activities of Polysaccharide from Green Algae Enteromorpha Linza. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2013, 58, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synytsya, A.; Choi, D.J.; Pohl, R.; Na, Y.S.; Capek, P.; Lattová, E.; Taubner, T.; Choi, J.W.; Lee, C.W.; Park, J.K.; et al. Structural Features and Anti-Coagulant Activity of the Sulphated Polysaccharide SPS-CF from a Green Alga Capsosiphon Fulvescens. Mar Biotechnol 2015, 17, 718–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahlevanzadeh, F.; Setayeshmehr, M.; Bakhsheshi-Rad, H.R.; Emadi, R.; Kharaziha, M.; Poursamar, S.A.; Ismail, A.F.; Sharif, S.; Chen, X.; Berto, F. A Review on Antibacterial Biomaterials in Biomedical Applications: From Materials Perspective to Bioinks Design. Polymers 2022, 14, 2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T.T.V.; Truong, H.B.; Tran, N.H.V.; Quach, T.M.T.; Nguyen, T.N.; Bui, M.L.; Yuguchi, Y.; Thanh, T.T.T. Structure, Conformation in Aqueous Solution and Antimicrobial Activity of Ulvan Extracted from Green Seaweed Ulva Reticulata. Natural Product Research 2018, 32, 2291–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournière, M.; Bedoux, G.; Souak, D.; Bourgougnon, N.; Feuilloley, M.G.J.; Latire, T. Effects of Ulva Sp. Extracts on the Growth, Biofilm Production, and Virulence of Skin Bacteria Microbiota: Staphylococcus Aureus, Staphylococcus Epidermidis, and Cutibacterium Acnes Strains. Molecules 2021, 26, 4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.I.A.; Amer, M.S.; Ibrahim, H.A.H.; Zaghloul, E.H. Considerable Production of Ulvan from Ulva Lactuca with Special Emphasis on Its Antimicrobial and Anti-Fouling Properties. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2022, 194, 3097–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraithong, S.; Bunyameen, N.; Theppawong, A.; Ke, X.; Lee, S.; Zhang, X.; Huang, R. Potentials of Ulva Spp.-Derived Sulfated Polysaccharides as Gelling Agents with Promising Therapeutic Effects. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 273, 132882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madany, M.A.; Abdel-Kareem, M.S.; Al-Oufy, A.K.; Haroun, M.; Sheweita, S.A. The Biopolymer Ulvan from Ulva Fasciata: Extraction towards Nanofibers Fabrication. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 177, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yan, S.; Zhu, Y.; Ning, Y.; Chen, T.; Yang, Y.; Qi, B.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y. Crosslinking of Gelatin Schiff Base Hydrogels with Different Structural Dialdehyde Polysaccharides as Novel Crosslinkers: Characterization and Performance Comparison. Food Chemistry 2024, 456, 140090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, D.; James, R.; Shelke, N.B.; Harmon, M.D.; Brown, J.L.; Hussain, F.; Kumbar, S.G. Gelatin Nanofiber Matrices Derived from Schiff Base Derivative for Tissue Engineering Applications. Journal of Biomedical Nanotechnology 2015, 11, 2067–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiryaghoubi, N.; Fathi, M.; Safary, A.; Javadzadeh, Y.; Omidi, Y. In Situ Forming Alginate/Gelatin Hydrogel Scaffold through Schiff Base Reaction Embedded with Curcumin-Loaded Chitosan Microspheres for Bone Tissue Regeneration. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 256, 128335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Lopes, G.; A. Pinto, D.C.G.; S. Silva, A.M. Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) as a Tool in Green Chemistry. RSC Advances 2014, 4, 37244–37265. [CrossRef]

- WINTERBOURN, C.C.; PARSONS-MAIR, H.N.; GEBICKI, S.; GEBICKI, J.M.; DAVIES, M.J. Requirements for Superoxide-Dependent Tyrosine Hydroperoxide Formation in Peptides. Biochemical Journal 2004, 381, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelli, A.; Betti, M.; Puppi, D.; Bartoli, C.; Gazzarri, M.; Chiellini, F. Enzymatically Crosslinked Ulvan Hydrogels as Injectable Systems for Cell Delivery. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics 2016, 217, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Huang, X.; Zoetebier, B.; Dijkstra, P.J.; Karperien, M. Enzymatic Co-Crosslinking of Star-Shaped Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Tyramine and Hyaluronic Acid Tyramine Conjugates Provides Elastic Biocompatible and Biodegradable Hydrogels. Bioactive Materials 2023, 20, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saqib, Md.N.; Khaled, B.M.; Liu, F.; Zhong, F. Hydrogel Beads for Designing Future Foods: Structures, Mechanisms, Applications, and Challenges. Food Hydrocolloids for Health 2022, 2, 100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansandee, W.; Moonmangmee, S.; Vangpikul, S.; Kosawatpat, P.; Tamtin, M. Physicochemical Properties and in Vitro Prebiotic Activity of Ulva Rigida Polysaccharides. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2024, 59, 103252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan, W.; Ramadhani, F.A.; Sevica, D.; Hardiningtyas, S.D. ; Desniar Synthesis and Characterization of Ulvan-Alginate Hydrogel Beads as a Scaffold for Probiotic Immobilization. BIO Web Conf. 2024, 92, 02020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariia, K.; Arif, M.; Shi, J.; Song, F.; Chi, Z.; Liu, C. Novel Chitosan-Ulvan Hydrogel Reinforcement by Cellulose Nanocrystals with Epidermal Growth Factor for Enhanced Wound Healing: In Vitro and in Vivo Analysis. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 183, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colodi, F.G.; Ducatti, D.R.B.; Noseda, M.D.; de Carvalho, M.M.; Winnischofer, S.M.B.; Duarte, M.E.R. Semi-Synthesis of Hybrid Ulvan-Kappa-Carrabiose Polysaccharides and Evaluation of Their Cytotoxic and Anticoagulant Effects. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 267, 118161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Xu, X.; Jing, C.; Zou, P.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y. Microwave Assisted Hydrothermal Extraction of Polysaccharides from Ulva Prolifera: Functional Properties and Bioactivities. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 181, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzaoui, A.; Ghariani, M.; Sellem, I.; Hamdi, M.; Feki, A.; Jaballi, I.; Nasri, M.; Amara, I.B. Extraction, Characterization and Biological Properties of Polysaccharide Derived from Green Seaweed “Chaetomorpha Linum” and Its Potential Application in Tunisian Beef Sausages. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 148, 1156–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayar, N.; Bouallegue, T.; Achour, M.; Kriaa, M.; Bougatef, A.; Kammoun, R. Ultrasonic Extraction of Pectin from Opuntia Ficus Indica Cladodes after Mucilage Removal: Optimization of Experimental Conditions and Evaluation of Chemical and Functional Properties. Food Chemistry 2017, 235, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez, H.; Loret, E.P. Ulva Lactuca, A Source of Troubles and Potential Riches. Marine Drugs 2019, 17, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltrusch, K.L.; Torres, M.D.; Domínguez, H. Characterization, Ultrafiltration, Depolymerization and Gel Formulation of Ulvans Extracted via a Novel Ultrasound-Enzyme Assisted Method. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2024, 111, 107072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahaye, M.; Robic, A. Structure and Functional Properties of Ulvan, a Polysaccharide from Green Seaweeds. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 1765–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, K.; Jesumani, V.; Khan, B.M.; Liu, Y.; Du, H. Algal Polysaccharides and Their Biological Properties. In Recent Advances in Micro and Macroalgal Processing; Rajauria, G., Yuan, Y.V., Eds.; Wiley, 2021; pp. 231–277 ISBN 978-1-119-54258-2.

- Michael, O.S.; Adetunji, C.O.; Ayeni, A.E.; Akram, M.; Inamuddin; Adetunji, J.B.; Olaniyan, M.; Muhibi, M.A. Marine Polysaccharides: Properties and Applications. In Polysaccharides; Inamuddin, Ahamed, M.I., Boddula, R., Altalhi, T., Eds.; Wiley, 2021; pp. 423–439 ISBN 978-1-119-71138-4.

- López-Hortas, L.; Flórez-Fernández, N.; Torres, M.D.; Ferreira-Anta, T.; Casas, M.P.; Balboa, E.M.; Falqué, E.; Domínguez, H. Applying Seaweed Compounds in Cosmetics, Cosmeceuticals and Nutricosmetics. Marine Drugs 2021, 19, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Yield (% dw) | MW (kDa) | Sulfate (% dw) | Extraction Solvent | T (°C) | Assisted |

Solvent for Co-product |

Ref | |

| U. ohnoi | 3.50 | 105 | 17.60 | HCl (pH2) | 37 | - | - | [52] | |

| U. tepida | 3.90 | 313 | 21.60 | HCl (pH2) | - | - | |||

| U. prolifera | 6.70 | 246 | 16.60 | HCl (pH2) | - | - | |||

| U. lactuca | 17.95 | - | 17.22 | Distilled water | 50 | Cellulase | - | [47] | |

| U. lactuca | 16.90 | 265 | 53 | NaOH | 70 | Ultrasonic | [48] | ||

| 14.50 | 280 | 58 | HCl | 70 | |||||

| 12.50 | 304 | 39 | Distilled water | 70 | |||||

| U. linza | 17.00 | - | - | Citric acid | 60 | - | - | [52] | |

| U. fasciata | 6.02 | - | 14.92 | Distilled water | - - - |

Ethanol-protein and pigment | [53] | ||

| 7.34 | - | 12.73 | HCl | ||||||

| 6.74 | - | 7.760 | Na2EDTA | ||||||

| U. lactuca | 14.22 | - | 16.82 | HCl (pH2) | 80 | - | - | [47] | |

| U. linza | 29.33 | 16 | 13.78 | Oxalic acid | - | Distilled water - Starch | [52] | ||

| U. intestinalis | 17.76 | 300 | - | Distillled water | - | - | [45] | ||

| 23.21 | 88 | - | Acidic water (pH3) | - | Ethanol-lipid and pigment | ||||

| 16.11 | 110 | - | Alkaline water (pH10) | - | |||||

| 20.41 | - | - | Distillled water | Microwave | |||||

| 17.89 | - | - | Distillled water | Autoclave 121 °C | |||||

| 23.73 | - | - | Distillled water | Ultrasonic | |||||

| U. ohnoi | 8.20 | 10.5 | 12,5 | HCl | 85 | - | Distilled water – salt | [44] | |

| 7.00 | 16.3 | 12.4 | HCl | - | Ethanol – pigments | ||||

| 8.10 | 10.8 | 12.5 | HCl | - | Distilled water – saltEthanol – pigments | ||||

| Ulva sp. | 0.04 | - | 18.00 | Citric acid | 90 | - | - | [54] | |

| U. fenestrata, U. lactuca, | 18.00 | - | 17.80 | HCl | - | - | [49,55] | ||

| U. compressa | 18.00 | - | 17.80 | HCl | - | - | [55] | ||

| U. lactuca, | 11.00 | - | 14.30 | Distilled water | Post-treatment α-amylase & proteinase K | Ethanol-protein and pigment | |||

| U. compressa | 11.00 | - | 9.30 | Distilled water | |||||

| U. lactuca | 41.96 | - | 23.20 | ChCl-glycerol | Peracetic acid | - | [56] | ||

| U. lactuca | 3.40 | - | 15.65 | HCl (pH1.5) | - | - | [47] | ||

| U. pertusa | 17.80 | 283 | 13.20 | Distilled water | - | - | [57] | ||

| 20.60 | 352 | 9.20 | Distilled water | Ultrasonic | - | ||||

| 25.30 | 404 | 6.80 | HCl (pH4.5) | Pretreatment cellulase at 50 °C | - | ||||

| 26.70 | 300 | 3.90 | HCl (pH4.5) | - | |||||

| Ulva sp. | 30.36 | - | - | HCl (pH2) | 90 | - | - | [58] | |

| 30.48 | - | 31 | Distilled water | 120 | Microwave hydrothermal | - | |||

| 30.46 | - | 40 | Distilled water | 140 | - | ||||

| 30.66 | - | 50 | Distilled water | 160 | - | ||||

| 30.70 | - | 20 | Distilled water | 180 | - | ||||

| 30.66 | - | 21 | Distilled water | 200 | - | ||||

| Ulva sp. | 11.00 | - | 11.02 | Distilled water | 120 | Hydrothermal | Pretreatment supercritical CO2 & ethanol - polyunsaturated rich lipids & phenolic content | [51] | |

| 19.00 | - | 7.14 | Distilled water | 140 | |||||

| 22.00 | - | 10.09 | Distilled water | 160 | |||||

| 5.00 | - | 7.58 | Distilled water | 180 | |||||

| 5.00 | - | 7.36 | Distilled water | 200 | |||||

| Polysac-charide | Source Algae | Yield Range (%) | Gelling Mechanism | Existing Function in Current Market | Commercial Availability | Mechanical Properties | Cytocom-patibility | Thermal Stability | Cross-Linking Potential | Functionalization Potential | Common Modifications | Applications of Modifications | Challenges in Modifications |

| Ulvan | Ulva spp. | 15-41 | Ionic cross-linking with divalent cations (e.g., Ca2+; CaCl2, H3BO3) | Emerging in tissue engineering, drug delivery, and bioadhesive development | Moderate, requires specialized extraction processes | Moderate elasticity, suitable for hydrogels | Excellent, supports cell adhesion and proliferation | Moderate, stable up to ~80°C under physiological conditions | High, forms strong ionic cross-links | High, easily modified with bioactive groups | Thiolated ulvan, sulfation, carboxymethylation, phosphorylation, hydrogel formation | Drug delivery, tissue engineering, bioadhesive development, antioxidant systems | Complexity in achieving uniform thiolation, scalability issues |

| Agar | Gelidium spp. | 10-15 | Thermal gelation via hydrogen bonding | Widely used in food industry (gels, thickeners), limited biomedical applications | High, widely available and established supply chain | Strong, brittle gels, limited elasticity | Good, limited applications in biomedical fields | High, retains gel pro-perties up to ~100°C | Moderate, limited chemical reactivity | Moderate, limited functionalization pathways | Thiolated agar, esterification, hydrogel formation, nanoparticle stabilization | Encapsulation, tissue scaffolding, bioadhesives, wound dressings | Low reactivity under mild conditions, batch variability |

| Carra-geenan | Kappa-phycus spp. | 20-30 | Thermal gelation via sulfate groups. Helical structures formed via 3,6-anhydro-galactose units and ion interactions | Predominantly in food as stabilizers and thickeners, some drug delivery systems | High, commercially available for various industries | Flexible gels, moderate strength | Moderate, may require modifications for biocompa- tibility |

High, stable up to ~120°C | High, versatile cross-linking potential | High, supports diverse chemical modifications | Sulfation, hydrogel formation, derivatization for drug delivery | Drug release matrices, bioadhesive, biocompatible scaffolds | Control over sulfation levels, stability in physiological conditions |

| Alginate | Macrocystis spp. | 15-35 | Ionic cross-linking with Ca2+ or other divalent ions | Extensively in food, pharmaceuticals, and wound care products | High, extensively used and widely produced | High elasticity, robust structural integrity | Excellent, widely used in tissue engineering | High, stable across wide temperature ranges (~150°C) | High, readily cross-links with divalent ions | High, extensively modified for various uses | Calcium cross-linking, thiolation, carboxylation, hydrogel formation, esterification | Controlled release systems, wound care, tissue scaffolding | High dependency on cross-linking agents, cost of modification processes |

| Fucoidan | Fucus spp. | 5-10 | Not a primary gelling agent, interacts through sulfated domains | Limited use in niche biomedical applications (anticoagulants, drug carriers) | Low, niche market with limited availability | Weak mechanical properties, limited application | Variable, dependent on sulfation level | Moderate, sensitive to heat above ~70°C | Low, limited cross-linking capability | Moderate, functionalization depends on sulfate groups | Sulfation, desulfation, acetylation, hydrogel formation, anti-coagulant enhancement | Anti-inflammatory agents, drug carriers, heparin substitutes | Variability in biological activity, cost-intensive extraction and modification |

| Laminaran | Laminaria spp. | 10-20 | Weak hydrogen bonding and limited gel formation | Occasionally in nutraceuticals and research-grade biomaterials | Low, specialized production with limited supply | Low mechanical strength, not primary gelling agent | Moderate, limited data on cytocompatibility | Low, weak stability under heat, <60°C | Low, rarely used for cross-linking | Low, not typically functionalized extensively | Oxidation, acetylation, hydrogel formation, nanoparticle delivery systems | Nanoparticle stabilizers, immune enhancement, tissue scaffolds | Low stability under physiological conditions, complex modification processes |

| Porphyran | Porphyra spp. | 10-15 | Thermal gelation and hydrogen bonding | Emerging in antioxidant-rich supplements and basic drug delivery systems | Moderate, emerging commercial interest | Moderate strength, suitable for soft applications | Good, supports basic biomedical applications | Moderate, stable under mild thermal conditions (~80°C) | Moderate, potential for chemical derivatization | Moderate, supports basic functionalization | Sulfation, esterification, hydrogel formation, antioxidant enhancement | Antioxidant applications, drug delivery, immune modulation | Limited structural studies, stability in industrial applications |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).