Submitted:

27 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Medicinal Plants in Traditional Systems of Medicines

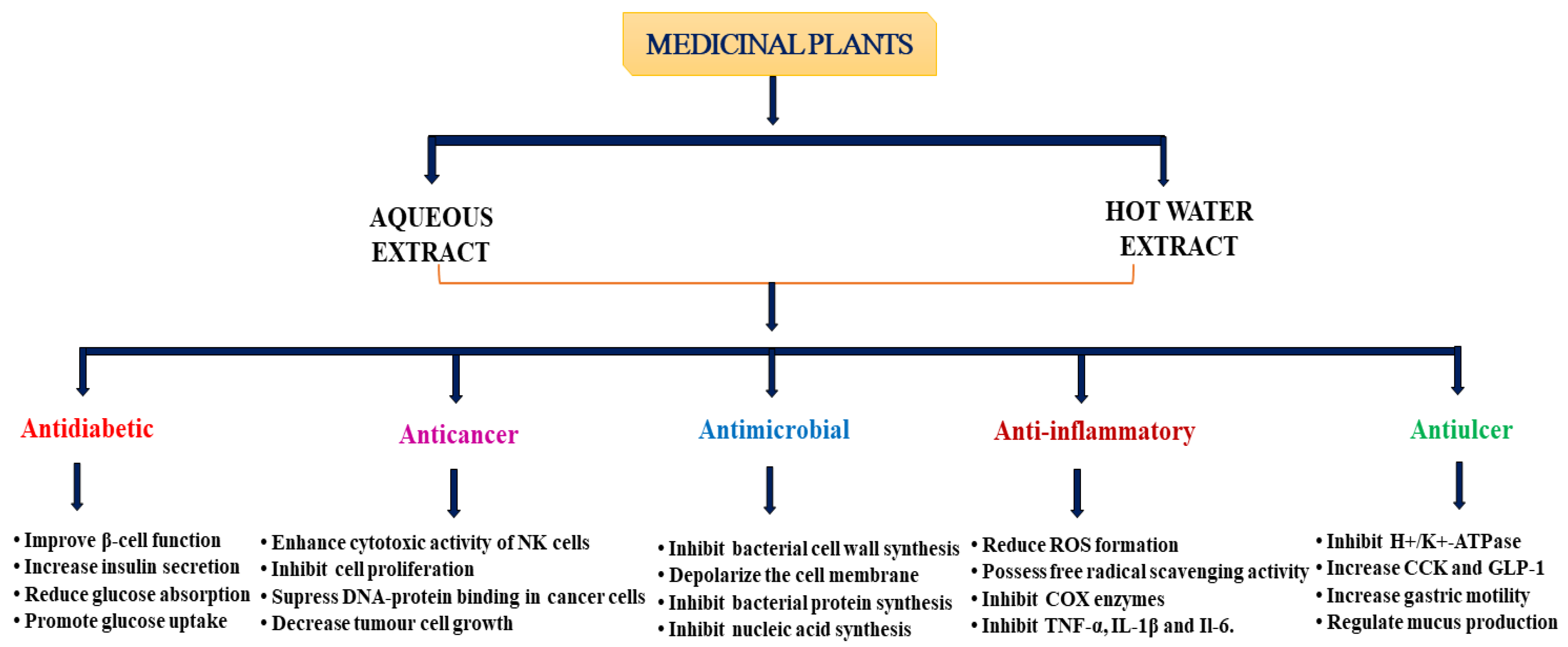

4. Pharmacological Properties of Medicinal Plants

4.1. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM)

4.2. Cancer

4.3. Infectious Diseases

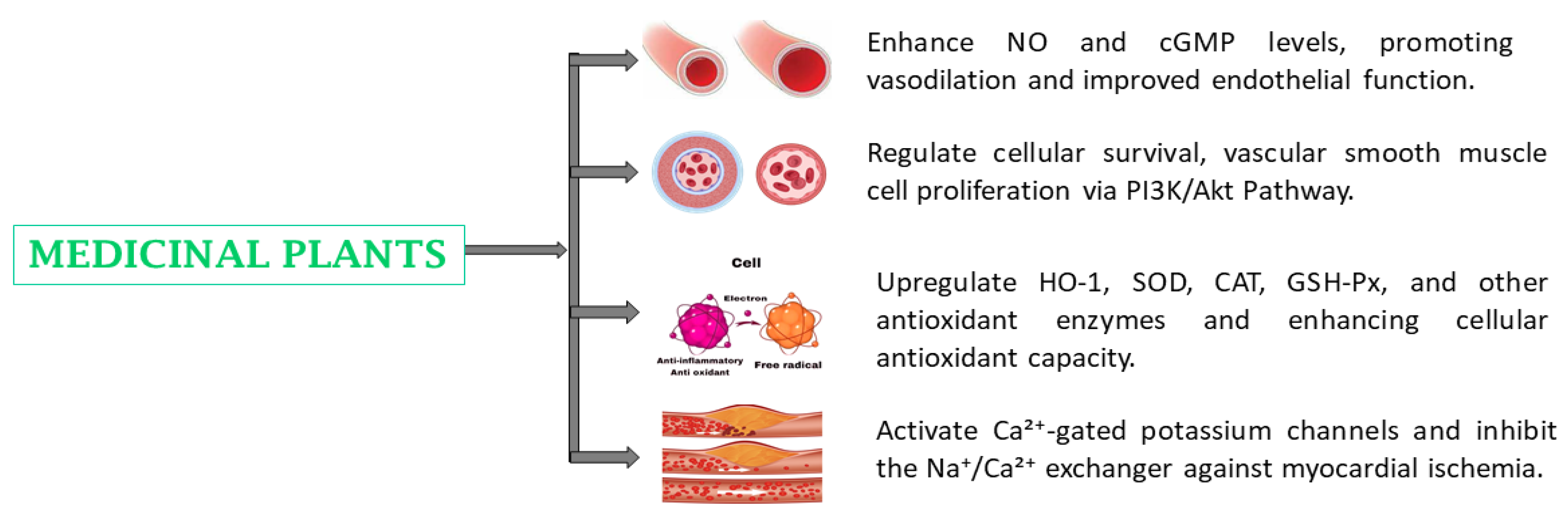

4.4. Cardiovascular Diseases

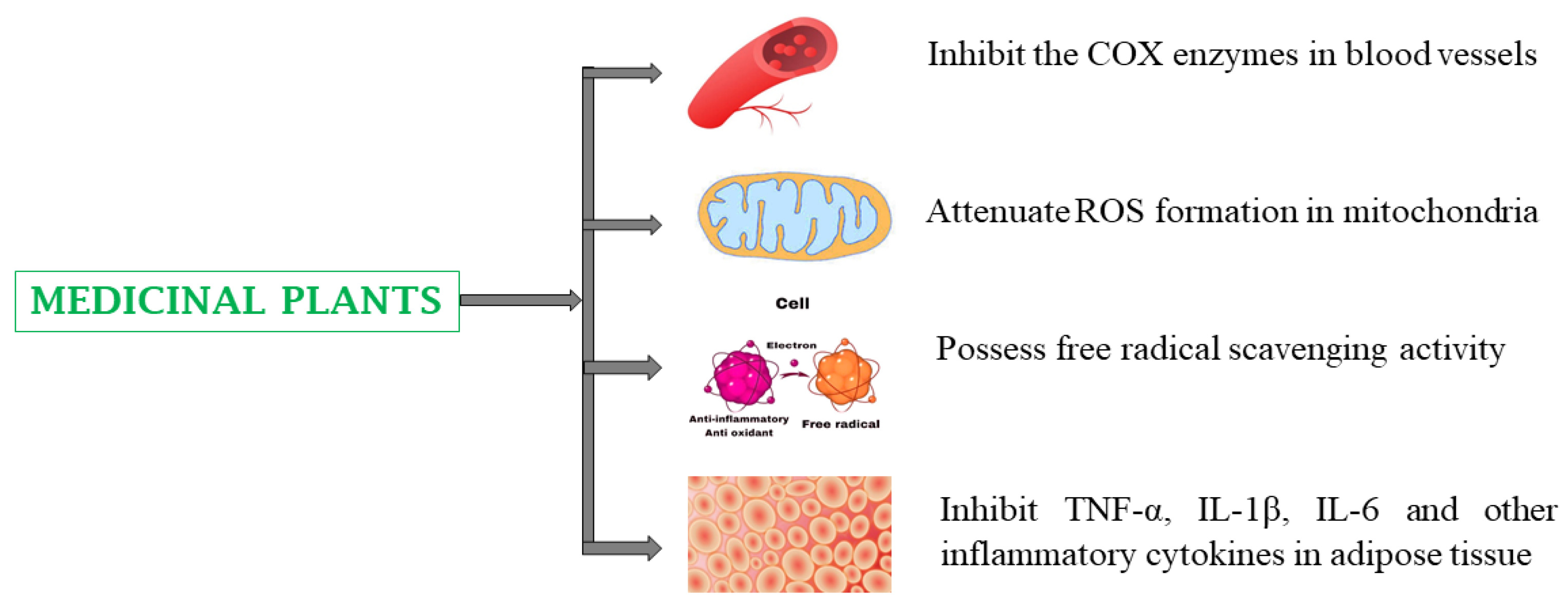

4.5. Inflammatory Diseases

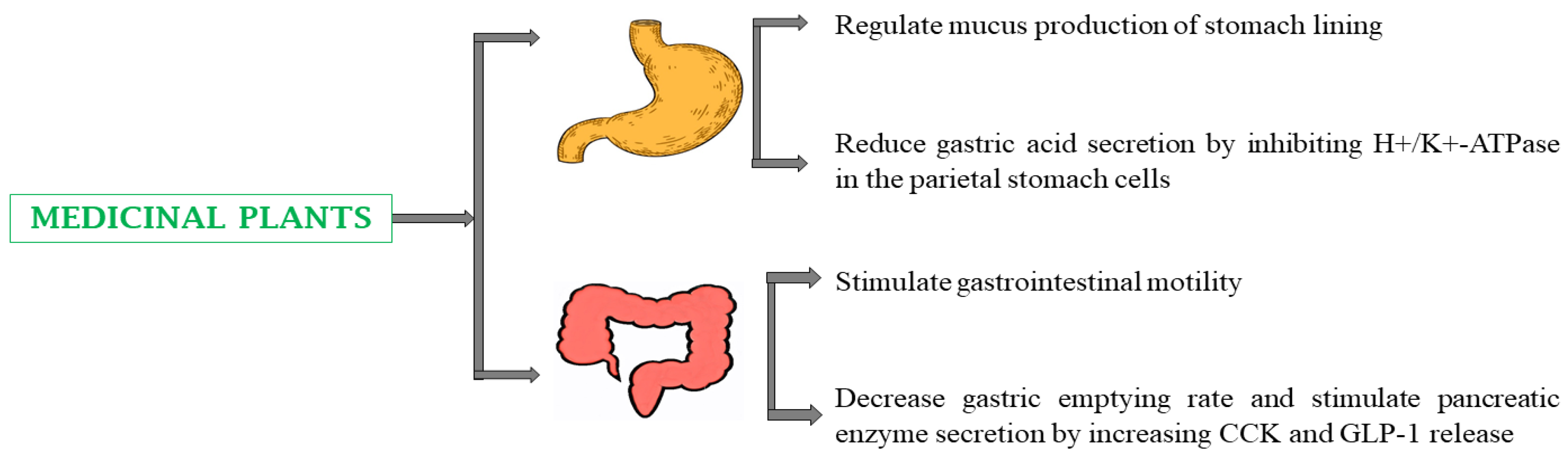

4.6. Gastrointestinal Disorders

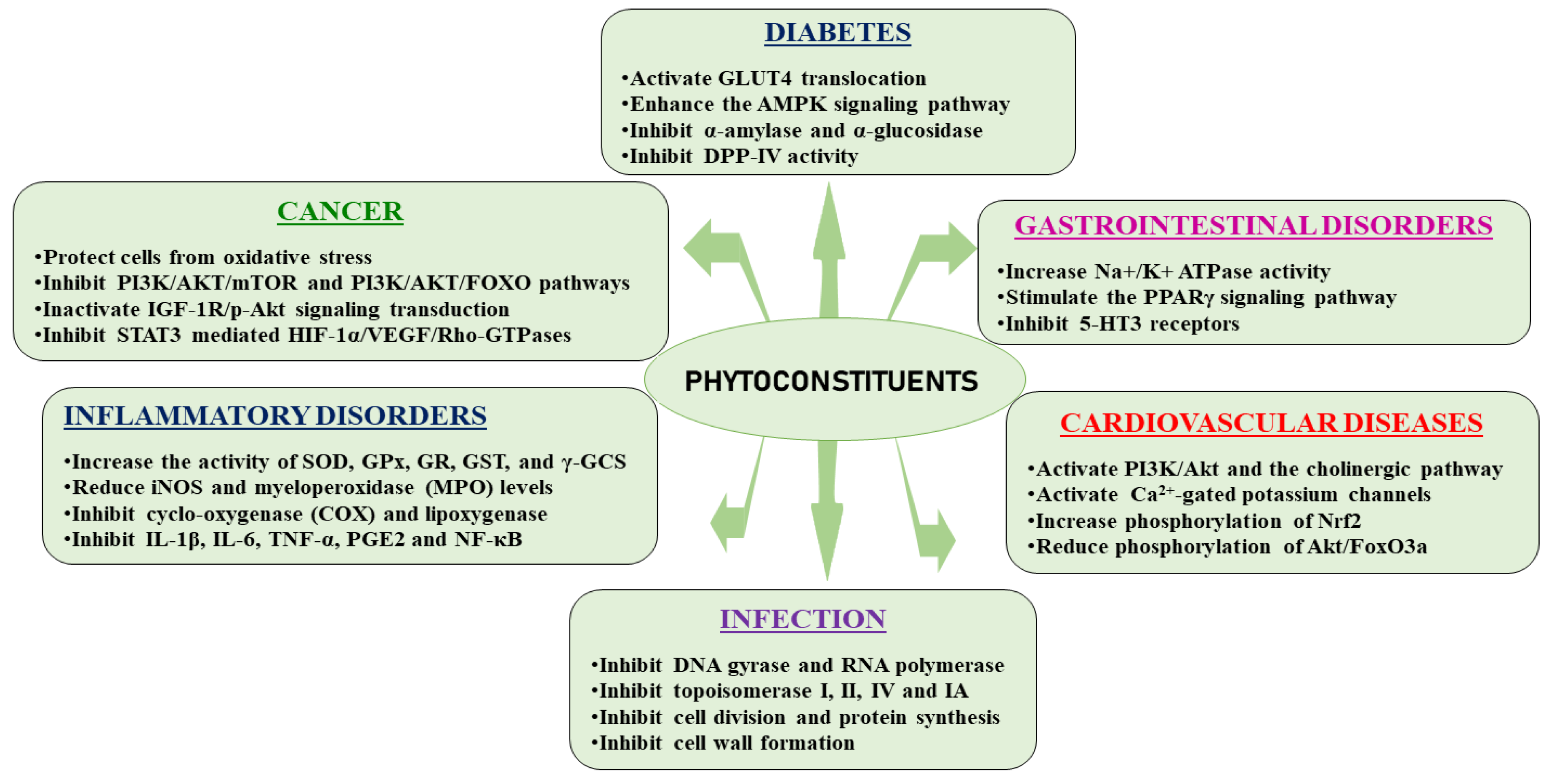

5. Phytoconstituents from Medicinal Plants and Their Therapeutic Mechanisms of Action

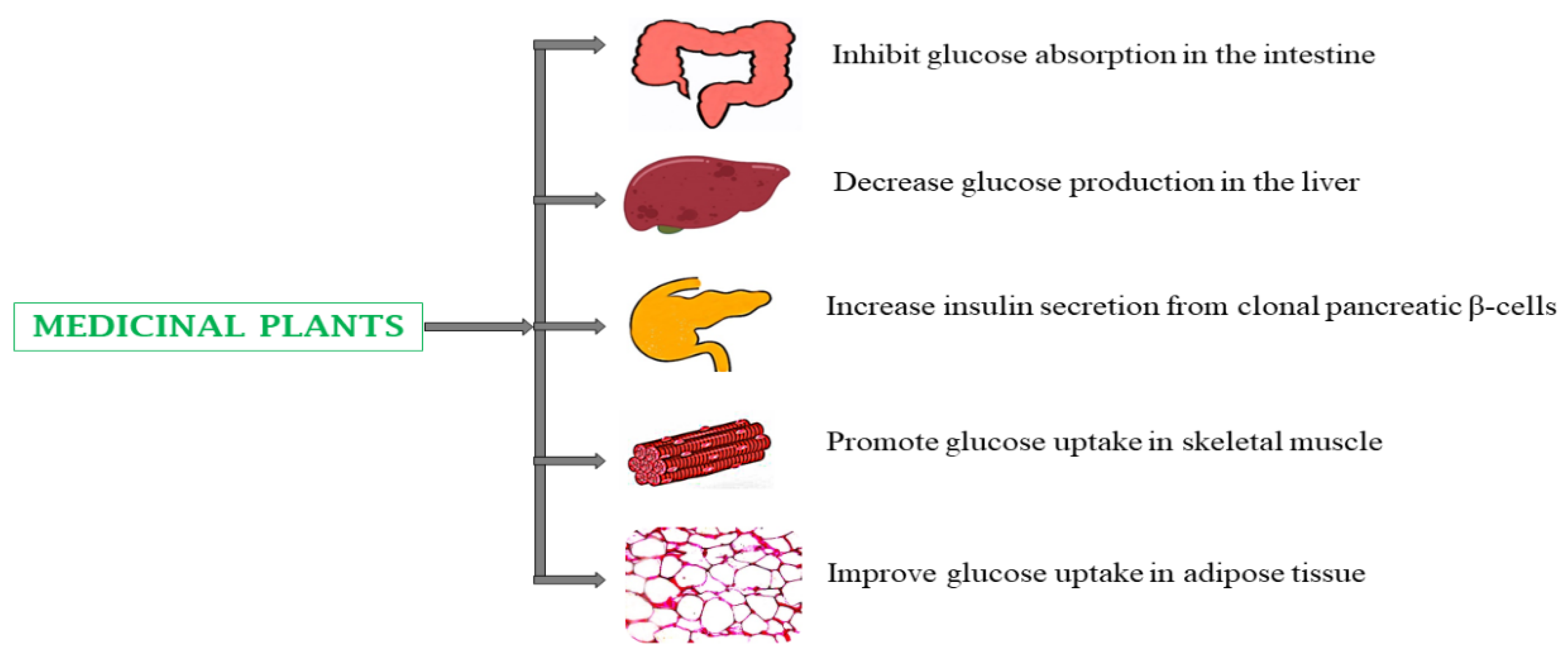

5.1. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

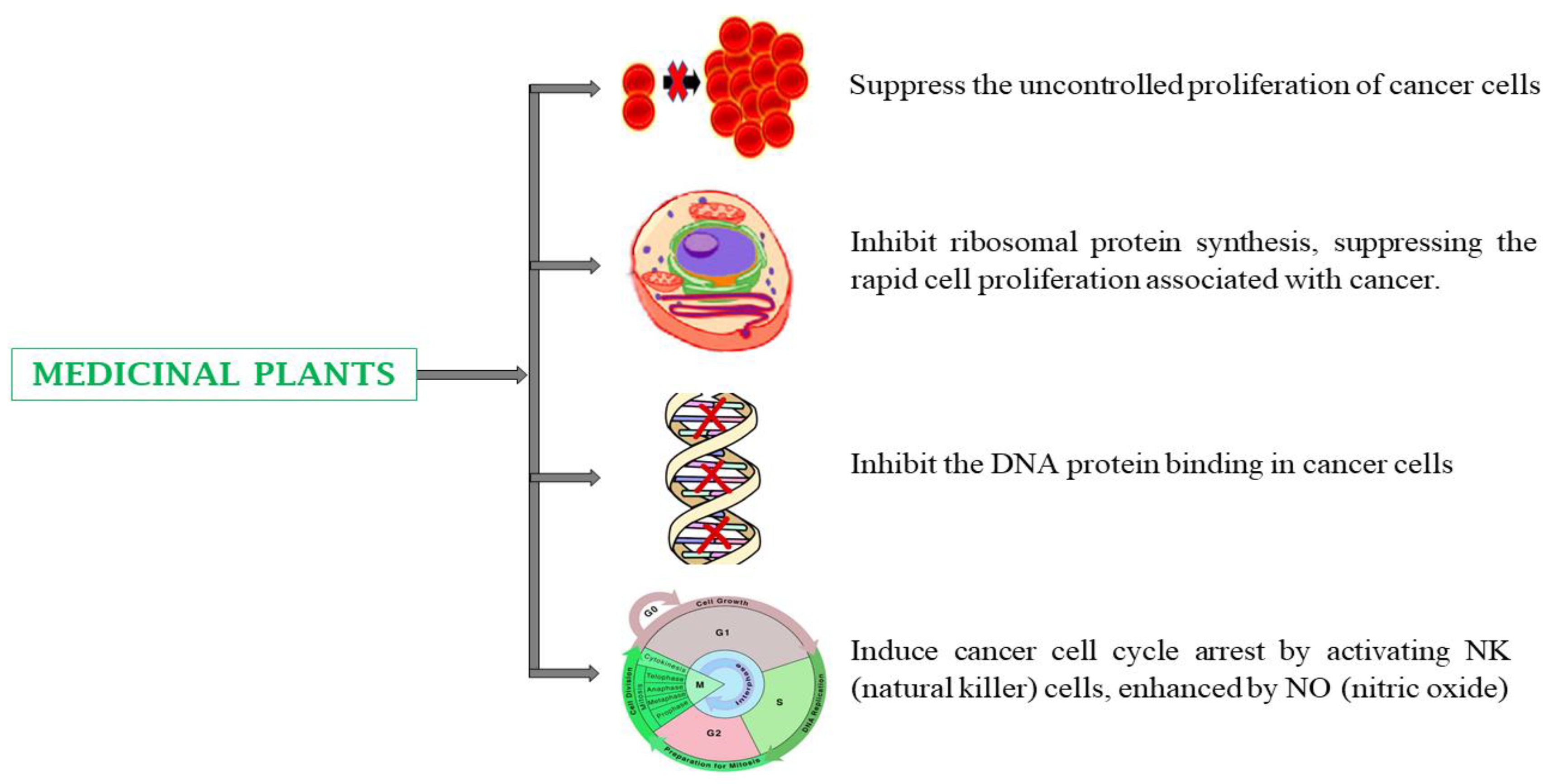

5.2. Cancer

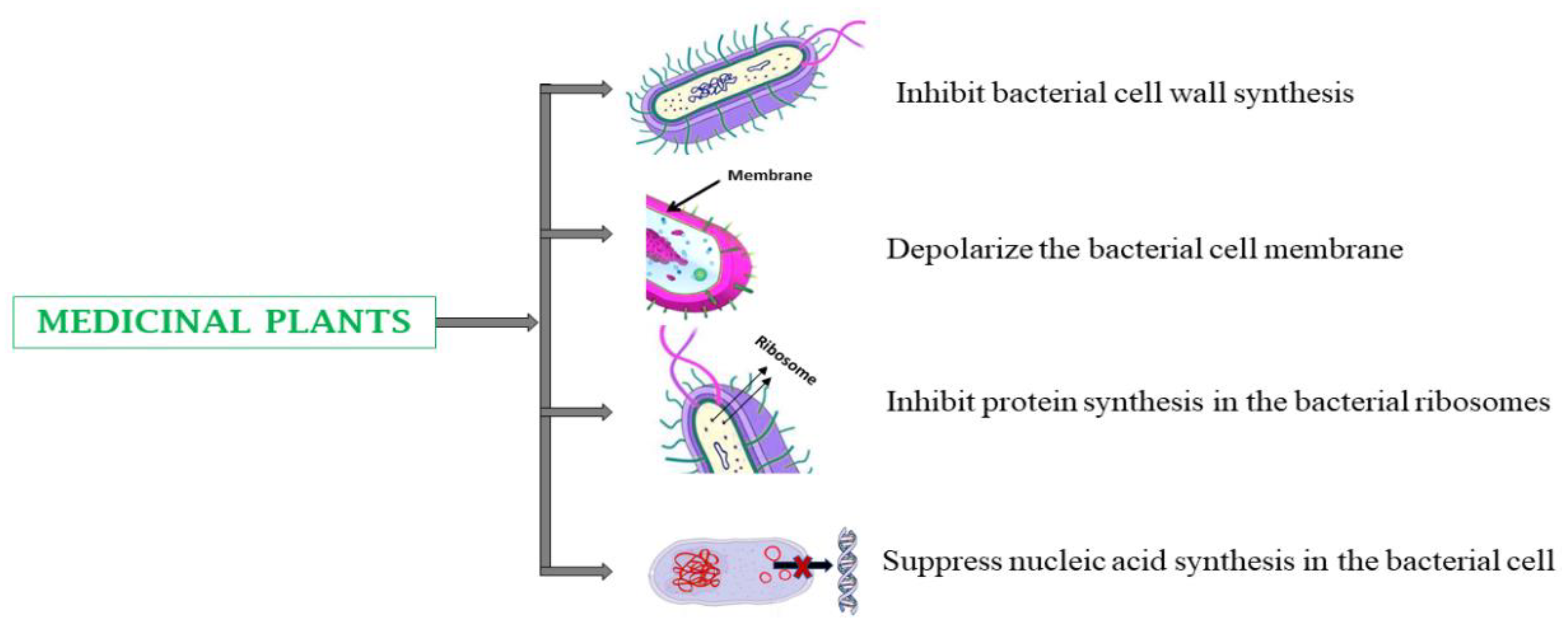

5.3. Infectious Diseases

5.4. Inflammatory Diseases

5.5. Cardiovascular Diseases

5.6. Gastrointestinal Disorders

6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| DM | Diabetes Mellitus |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| GI disorder | Gastrointestinal disorder |

| NSAID | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| TCM | Traditional Chinese Medicine |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor |

| GHR | Ghrelin |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon like peptide-1 |

| STZ | Streptozotocin |

| DPP-IV | Dipeptidyl peptidase IV |

| AP-1 | Activator protein-1 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| PKC | Protein kinase C |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| ACE | Acetylcholinesterase |

| VSMC | Vascular smooth muscle cell |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| Akt/FoxO3a | Akt, protein kinase B; FoxO3a, forkhead box O |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 |

| HO-1 | Hemeoxygenase-1 |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| GSH-Px | Glutathione peroxidase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| GR | Glutathione reductase |

| GST | Glutathione S-transferase |

| Γ-GCS | γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase |

| NQO1 | NADPH: quinone oxidoreductase-1 |

| HSP70 | Heat shock proteins 70 |

| iNOS | Inducible NOS |

| MPO | Myeloperoxidase |

| TC | Total cholesterol |

| LDL | Low density lipoprotein |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| HDL | High density lipoprotein |

| VLDL | Very low density lipoprotein |

| SD rats | Sprague-Dawley rats |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| DCMM | Dichloromethane: methanol extract |

| TNBS | Trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid |

| ISO | Isoproterenol |

| CMC | Carboxy methyl cellulose |

| HDL-C | HDL-cholesterol |

| LDL-C | LDL-cholesterol |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| AST | Aspartate transferase |

| ALT | Alanine amino transferase |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| GGT | Gamma glutamyl transpeptidase |

| FI | Food intake |

| FER | Food efficiency ratio |

| FBG | Fasting blood glucose |

| GLUT4 | Glucose transporter 4 |

| DGAT-1 | Diacylglycerol o-acyltransferase 1 |

| ApoB100 | Apolipoprotein |

| ApoA-1 | Apolipoprotein A-1 |

| HbA1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| iNOS | Inducible NO synthase |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| CAT | Catalase |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| SGOT | Serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase |

| SGPT | Serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase |

| SALP | Serum alkaline phosphatase |

| LPO | Lipid peroxidation |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| HOMA-IS | Homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistance |

| NEFA | Non-esterified fatty acids |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances |

| TAA | Total ascorbic acid |

| HMG-CoA | Hydroxy methylglutaryl-coenzyme A |

| ApoB | Apolipoprotein B |

| HMGR | HMG-CoA reductase |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| LCAT | Lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase |

| LPL | Lipoprotein lipase |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

| NK cells | Natural killer cells |

| GLUT4 | Glucose transporter 4 |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin 1β |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species 1. |

References

- Veiga, M.; Costa, E. M.; Silva, S.; Pintado, M. Impact of plant extracts upon human health: A review. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2020, 60, 873–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proestos, C. The benefits of plant extracts for human health. Foods 2020, 9, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathan, D. M. Long-term complications of diabetes mellitus. The New England journal of medicine 1993, 328, 1676–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, P.; Akther, S.; Hannan, J. M. A.; Seidel, V.; Nujat, N. J.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. Pharmacologically active phytomolecules isolated from traditional antidiabetic plants and their therapeutic role for the management of diabetes mellitus. Molecules 2022, 27, 4278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, M. L.; Asero, R.; Bavbek, S.; Blanca, M.; Blanca-Lopez, N.; Bochenek, G.; Brockow, K.; Campo, P.; Celik, G.; Cernadas, J.; Cortellini, G.; Gomes, E.; Niżankowska-Mogilnicka, E.; Romano, A.; Szczeklik, A.; Testi, S.; Torres, M. J.; Wöhrl, S.; Makowska, J. Classification and practical approach to the diagnosis and management of hypersensitivity to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Allergy 2013, 68, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainsford, K. Anti-inflammatory drugs in the 21st century. Sub-cellular biochemistry 2007, 42, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, S.; Dickinson, J. A.; Somayaji, R. Update on the adverse effects of antimicrobial therapies in community practice. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien 2020, 66, 651–659. [Google Scholar]

- Basak, D.; Arrighi, S.; Darwiche, Y.; Deb, S. Comparison of anticancer drug toxicities: paradigm shift in adverse effect profile. Life (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 12, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurgali, K.; Jagoe, R. T.; Abalo, R. Adverse effects of cancer chemotherapy: Anything new to improve tolerance and reduce sequelae? Frontiers in pharmacology 2018, 9, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadiani, S.; Nikfar, S. Challenges of access to medicine and the responsibility of pharmaceutical companies: a legal perspective. Daru : journal of Faculty of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences 2016, 24, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, P.; Okigbo, R. N. Effects of plants and medicinal plant combinations as anti-infectives. Afr J Pharm Pharmacol 2008, 2, 130–5. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, S. An overview of plant extracts as potential therapeutics. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents 2003, 13, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Gupta, N.; Chatterjee, S.; Nimesh, S. Natural plant extracts as potential therapeutic agents for the treatment of cancer. Current topics in medicinal chemistry 2017, 17, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pushpangadan, P.; George, V.; Ijinu, T.; Chithra, M. A. Ethnomedicine, health food and nutraceuticals-traditional wisdom of maternal and child health in India. Edelweiss Applied Science and Technology 2018, 2, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Gui, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, T.; Yang, Y.; Niu, Y.; Fu, D.; Wang, J.; Cui, T. Innovative development path of ethnomedicines: a case study. Frontiers of Medicine 2017, 11, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Singh, S. P. Current and future status of herbal medicines. Veterinary world 2008, 1, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A. S.; Yadav, S. S.; Singh, P.; Nandal, A.; Singh, N.; Ganaie, S. A.; Yadav, N.; Kumar, R.; Bhandoria, M. S.; Bansal, P. A comprehensive review on ethnomedicine, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and toxicity of Tephrosia purpurea (L.) Pers. Phytotherapy research: PTR 2020, 34, 1902–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. S. A.; Ahmad, I. (2019). Herbal medicine: current trends and future prospects. In New look to phytomedicine. Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Gogtay, N. J.; Bhatt, H. A.; Dalvi, S. S.; Kshirsagar, N. A. The use and safety of non-allopathic Indian medicines. Drug safety 2002, 25, 1005–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M. M.; Rastogi, S.; Rawat, A. K. S. Indian traditional ayurvedic system of medicine and nutritional supplementation. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine: eCAM 2013, 2013, 376327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazil, M.; Nikhat, S. Exploring new horizons in health care: A mechanistic review on the potential of Unani medicines in combating epidemics of infectious diseases. Phytotherapy Research: PTR 2021, 35, 2317–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazil, M.; Nikhat, S. Topical medicines for wound healing: A systematic review of Unani literature with recent advances. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2020, 257, 112878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parveen, A.; Parveen, R.; Akhatar, A.; Parveen, B.; Siddiqui, K. M.; Iqbal, M. Concepts and quality considerations in Unani system of medicine. Journal of AOAC International 2020, 103, 609–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R. S.; Singh, A.; Kaur, H.; Batra, G.; Sarma, P.; Kaur, H.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Sharma, A. R.; Kumar, S.; Upadhyay, S.; Tiwari, V.; Avti, P.; Prakash, A.; Medhi, B. Promising traditional Indian medicinal plants for the management of novel Coronavirus disease: A systematic review. Phytotherapy Research: PTR 2021, 35, 4456–4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupani, R.; Chavez, A. Medicinal plants with traditional use: Ethnobotany in the Indian subcontinent. Clinics in dermatology 2018, 36, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suroowan, S.; Pynee, K. B.; Mahomoodally, M. F. A comprehensive review of ethnopharmacologically important medicinal plant species from Mauritius. South African Journal of Botany 2019, 122, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živković, J.; Ilić, M.; Šavikin, K.; Zdunić, G.; Ilić, A.; Stojković, D. Traditional use of medicinal plants in South-Eastern Serbia (Pčinja District): Ethnopharmacological investigation on the current status and comparison with half a century old data. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2020, 11, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. P.; Woerdenbag, H. J. Traditional Chinese herbal medicine. Pharmacy World and Science: PWS 1995, 17, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suroowan, S.; Pynee, K. B.; Mahomoodally, M. F. A comprehensive review of ethnopharmacologically important medicinal plant species from Mauritius. South African Journal of Botany 2019, 122, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedjou, C. G.; Grigsby, J.; Mbemi, A.; Nelson, D.; Mildort, B.; Latinwo, L.; Tchounwou, P. B. The management of diabetes mellitus using medicinal plants and vitamins. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 9085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firenzuoli, F.; Gori, L. European traditional medicine–international congress–introductory statement. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine: eCAM 2007, 4 (Suppl. S1), 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurib-Fakim, A. Medicinal plants: traditions of yesterday and drugs of tomorrow. Molecular aspects of Medicine 2006, 27, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazil, M.; Nikhat, S. Topical medicines for wound healing: A systematic review of Unani literature with recent advances. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2020, 257, 112878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zari, S. T.; Zari, T. A. A review of four common medicinal plants used to treat eczema. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research 2015, 9, 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeri, A.; Sahebkar, A.; Javadi, B. Melissa officinalis L.–A review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2016, 188, 204–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. S.; Weng, J. K. Demystifying traditional herbal medicine with modern approach. Nature plants 2017, 3, 17109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohi-Ud-Din, R.; Mir, R. H.; Mir, P. A.; Farooq, S.; Raza, S. N.; Raja, W. Y.; Masoodi, M. H.; Singh, I. P.; Bhat, Z. A. Ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry and pharmacological aspects of the genus berberis linn: A comprehensive review. Combinatorial Chemistry & High Throughput Screening 2021, 24, 624–644. [Google Scholar]

- Dianita, R.; Jantan, I. Ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry and pharmacological aspects of the genus Premna: a review. Pharmaceutical biology 2017, 55, 1715–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durant-Archibold, A. A.; Santana, A. I.; Gupta, M. P. Ethnomedical uses and pharmacological activities of most prevalent species of genus Piper in Panama: A review. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2018, 217, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D. K.; Kumar, R.; Laloo, D.; Hemalatha, S. Diabetes mellitus: an overview on its pharmacological aspects and reported medicinal plants having antidiabetic activity. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine 2012, 2, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, A. G.; Qazi, G. N.; Ganju, R. K.; El-Tamer, M.; Singh, J.; Saxena, A. K.; Bedi, Y. S.; Taneja, S. C.; Bhat, H. K. Medicinal plants and cancer chemoprevention. Current drug metabolism 2008, 9, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A. , Sadia, S., Pan, K., Ullah, I., Mussarat, S., Sun, F.,... & Adnan, M. (2017). A systematic review on ethnomedicines of anti-cancer plants. Phytotherapy Research, 31(2), 202-264. [CrossRef]

- Bharti, S. K.; Krishnan, S.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, A. Antidiabetic phytoconstituents and their mode of action on metabolic pathways. Therapeutic Advances in Endocrinology and metabolism 2018, 9, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, A. D.; Bhowmik, P.; Banerjee, A.; Das, A.; Ojha, D.; Chattopadhyay, D. Ethnomedicinal wisdom: an approach for antiviral drug development. New look to phytomedicine 2019, 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaou, N.; Stavropoulou, E.; Voidarou, C.; Tsigalou, C.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Towards advances in medicinal plant antimicrobial activity: A review study on challenges and future perspectives. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabur, R.; Gupta, A.; Mandal, T. K.; Singh, D. D.; Bajpai, V.; Gurav, A. M.; Lavekar, G. S. Antimicrobial activity of some Indian medicinal plants. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines: AJTCAM 2007, 4, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngezahayo, J.; Ribeiro, S. O.; Fontaine, V.; Hari, L.; Stévigny, C.; Duez, P. In vitro study of five herbs used against microbial infections in Burundi. Phytotherapy Research: PTR, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, C.; Lu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, R.; Wang, W. A review of Chinese herbal medicine for the treatment of chronic heart failure. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2017, 23, 5115–5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czigle, S.; Bittner Fialova, S.; Tóth, J.; Mučaji, P.; Nagy, M.; Oemonom. Treatment of gastrointestinal disorders—Plants and potential mechanisms of action of their constituents. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 27, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamyab, R.; Namdar, H.; Torbati, M.; Ghojazadeh, M.; Araj-Khodaei, M.; Fazljou, S. M. B. Medicinal plants in the treatment of hypertension: A review. Advanced Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2021, 11, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S. A.; Joo, B. J.; Lee, J. S.; Ryu, G.; Han, M.; Kim, W. Y.; Park, H.H.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, C. S. Phytochemicals as anti-inflammatory agents in animal models of prevalent inflammatory diseases. Molecules 2020, 25, 5932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, P.; Flatt, P. R.; Harriott, P.; Hannan, J. M. A.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. Identification of multiple pancreatic and extra-pancreatic pathways underlying the glucose-lowering actions of Acacia arabica Bark in type-2 diabetes and isolation of active phytoconstituents. Plants 2021, 10, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajvaidhya, S.; Nagori, B. P.; Singh, G. K.; Dubey, B. K.; Desai, P.; Jain, S. A review on Acacia arabica-an Indian medicinal plant. International Journal of pharmaceutical sciences and research 2012, 3, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, G. A.; Alnoury, A. M.; Gad, H. G. The role of Acacia Arabica extract as an antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic, and antioxidant in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Saudi medical journal 2013, 34, 727–733. [Google Scholar]

- Ebhohimen, I. E.; Ebhomielen, J. O.; Edemhanria, L.; Osagie, A. O.; Omoruyi, J. I. Effect of ethanol extract of Aframomum angustifolium seeds on potassium bromate induced liver and kidney damage in Wistar rats. Global Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences 2020, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet-Duquennoy, M.; Dumas, M.; Debacker, A.; Lazou, K.; Talbourdet, S.; Franchi, J.; Heusèle, C.; André, P.; Schnebert, S.; Bonté, F.; Kurfürst, R. Transcriptional effect of an Aframomum angustifolium seed extract on human cutaneous cells using low-density DNA chips. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology 2007, 6, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim S., H.; Jo, S. H.; Kwon, Y. I.; Hwang, J. K. Effects of onion (Allium cepa L.) extract administration on intestinal α-glucosidases activities and spikes in postprandial blood glucose levels in SD rats model. International journal of molecular sciences 2011, 12, 3757–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheka, D. M.; Alkizim, F. O. Complementary and alternative medicine for type 2 diabetes mellitus: Role of medicinal herbs. J. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2012, 3, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanston-Flatt, S. K.; Flatt, P. R. Traditional dietary adjuncts for the treatment of diabetes mellitus. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 1991, 50, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojieh, A. E.; Adegor, E. C.; Okolo, A. C.; Lawrence, E. O.; Njoku, I. P.; Onyekpe, C. U. Hypoglycemic and hypolipidaemic effect of allium cepa in streptozotocin-induced diabetes. International Journal of Science and Engineering 2015, 6, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, M.; Al-Amin, Z. M.; Al-Qattan, K. K.; Shaban, L. H.; Ali, M. Anti-diabetic and hypolipidaemic properties of garlic (Allium sativum) in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. International Journal of Diabetes and Metabolism 2007, 15, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyo, J. E.; Ozougwu, J. C.; Echi, P. C. Hypoglycaemic effects of Allium cepa, Allium sativum and Zingiber officinale aqueous extracts on alloxan-induced diabetic Rattus novergicus. Medical Journal of Islamic World Academy of Sciences 2011, 19, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Swanston-Flatt, S. K.; Day, C.; Bailey C., J.; Flatt, P. R. Traditional plant treatments for diabetes. Studies in normal and streptozotocin diabetic mice. Diabetologia 1990, 1990 33, 462–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluko, O. J. Evaluation of various uses of Aloe barban-densis Miller (L) Burm (Aloe vera plant) by rural dwellers in Ile-Ogbo, Ayedire Local Government, Osun State. Scientific Research Journal 2019, 6, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, E. A. K.; Ali, E. Antidiabetic, antihypercholestermic and antioxidative effect of Aloe vera gel extract in alloxan induced diabetic rats. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2011, 5, 1321–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Naini, M. A.; Zargari-Samadnejad, A.; Mehrvarz, S.; Tanideh, R.; Ghorbani, M.; Dehghanian, A.; Hasanzarrini, M.; Banaee, F.; Koohi-Hosseinabadi, O.; Tanideh, N.; Iraji, A. Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and healing-promoting effects of Aloe vera extract in the experimental colitis in rats. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine: eCAM 2021, 2021, 9945244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florence, N. T.; Benoit, M. Z.; Jonas, K.; Alexandra, T.; Désiré, D. D. P.; Pierre, K.; Théophile, D. Antidiabetic and antioxidant effects of Annona muricata (Annonaceae), aqueous extract on streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2014, 151, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chackrewarthy, S.; Thabrew, M. I.; Weerasuriya, M. K.; Jayasekera, S. Evaluation of the hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects of an ethylacetate fraction of Artocarpus heterophyllus (jak) leaves in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Pharmacognosy Magazine 2010, 6, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moke, L. E.; Koto-te-Nyiwa, N. G. N.; Bongo, L. M.; Noté, O. P.; Mbing, J. N.; Mpiana, P. T. Artocarpus heterophyllus lam.(moraceae): phytochemistry, Pharmacology and future directions, a mini-review. Journal of Advanced Botany and Zoology 2017, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, J. N.; Flatt, P. R.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. Asparagus adscendens (Shweta musali) stimulates insulin secretion, insulin action and inhibits starch digestion. The British Journal of Nutrition 2006, 95, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K. S. P.; Gupta, R. K.; Raut, G.; Patel, B. P. Traditional uses, Phytochemistry and Pharmacology of Asparagus adscendens Roxb. : A Review. Journal of Ayurveda Campus 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostofa, M.; Choudhury, M. E.; Hossain, M. A.; Islam, M. Z.; Islam, M. S.; Sumon, M. H. Antidiabetic effects of Catharanthus roseus, Azadirachta indica, Allium sativum and glimepride in experimentally diabetic induced rat. Bangladesh Journal of Veterinary Medicine 2007, 5, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayana, K.; Sravanthi, K.; Shaker, I. A.; Ponnulakshmi, R. Molecular approach to identify antidiabetic potential of Azadirachta indica. Journal of Ayurveda and integrative medicine 2015, 6, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, R. R.; Bandyopadhyay, M. Effect of Azadirachta indica leaf extract on serum lipid profile changes in normal and streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. African Journal of Biomedical Research 2005, 8, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, O. E.; Ese, A. C.; Lawrence, E. O. Regulated effects of Capsicum frutescens supplemented diet (CFSD) on fasting blood glucose level, biochemical parameters and body weight in alloxan induced diabetic Wistar rats. British Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 2013, 3, 496–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koffi-Nevry, R.; Kouassi, K. C.; Nanga, Z. Y.; Koussémon, M.; Loukou, G. Y. Antibacterial activity of two bell pepper extracts: Capsicum annuum L. and Capsicum frutescens. International journal of food properties 2012, 15, 961–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasineni, K.; Bellamkonda, R.; Singareddy, S. R.; Desireddy, S. Antihyperglycemic activity of Catharanthus roseus leaf powder in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Pharmacognosy research 2010, 2, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. N.; Vats, P.; Suri, S.; Shyam, R.; Kumria, M. M.; Ranganathan, S.; Sridharan, K. Effect of an antidiabetic extract of Catharanthus roseus on enzymic activities in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2001, 76, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abas, F.; Khatib, A.; Perumal, V.; Suppaiah, V.; Ismail, A.; Hamid, M.; Shaari, K.; Lajis, N. H. Metabolic alteration in obese diabetes rats upon treatment with Centella asiatica extract. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2016, 180, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagawati, M.; Hazarika, N. K.; Baishya, M. K.; Saikia, K.; Pegu, D. K.; Sarmah, R. Effect of Centella asiatica extracts on shigella dysenteriae and bacillus coagulans compared to commonly used antibiotics. Journal of Pharmaceutical, Chemical and Biological Sciences 2018, 5, 337–344. [Google Scholar]

- El-Desoky, G. E.; Aboul-Soud, M. A.; Al-Numair, K. S. Antidiabetic and hypolipidemic effects of Ceylon cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum) in alloxan-diabetic rats. J. Med. Plants Res. 2012, 6, 1685–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyshaburinezhad, N.; Rouini, M.; Lavasani, H.; Ardakani, Y. H. Evaluation of Cinnamon (Cinnamomum Verum) Effects on Liver CYP450 2D1 Activity and Hepatic Clearance in Diabetic Rats. Jundishapur J. Nat. Pharm. Prod. 2001, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, H. L.; Jung, Y.; Ahn, K. S.; Kwak, H. J.; Um, J. Y. Bitter Orange (Citrus aurantium Linné) Improves Obesity by Regulating Adipogenesis and Thermogenesis through AMPK Activation. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Fernandes, J.; Ahirwar, D.; Jain, R. Hypoglycemic and hypolipidimic activity of alcoholic extract of citrus aurantium in normal and alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Pharmacologyonline, 2008, 3, 161–171. [Google Scholar]

- Naim, M.; Amjad, F. M.; Sultana, S.; Islam, S. N.; Hossain, M. A.; Begum, R.; Rashid, M. A.; Amran, M. S. Comparative study of antidiabetic activity of hexane-extract of lemon peel (Limon citrus) and glimepiride in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Bangladesh Pharm. J. 2012, 15, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrenti, V.; Consoli, V.; Grosso, S.; Raffaele, M.; Amenta, M.; Ballistreri, G.; Fabroni, S.; Rapisarda, P.; Vanella, L. Bioactive compounds from lemon (Citrus limon) extract overcome TNF-α-induced insulin resistance in cultured adipocytes. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 26, 4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boshtam, M.; Naderi, G. A.; Moshtaghian, J.; Asgary, S.; Jafari, N. Effects of citrus limon burm. f. on some atherosclerosis risk factors in rabbits with atherogenic diet. ARYA Atherosclerosis Journal 2010, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Sakhya, S. K. Ethnopharmacological properties of Curcuma longa: a review. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research 2013, 4, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, P. S.; Srinivasan, K. Hypolipidemic action of curcumin, the active principle of turmeric (Curcuma longa) in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Molecular and cellular biochemistry 1997, 166, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kulkarni, S.K.; Chopra, K. Curcumin, the active principle of turmeric (Curcuma longa), ameliorates diabetic nephropathy in rats. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2006, 33, 940–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Nishizono, S.; Makino, N.; Tamaru, S.; Terai, O.; Ikeda, I. Hypoglycemic activity of Eriobotrya japonica seeds in type 2 diabetic rats and mice. Bioscience, biotechnology, and biochemistry 2008, 72, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. H.; Shih, Z. Z.; Kuo, Y. H.; Huang, G. J.; Tu, P. C.; Shih, C. C. Antidiabetic and antihyperlipidemic effects of the flower extract of Eriobotrya japonica in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice and the potential bioactive constituents in vitro. Journal of Functional Foods 2018, 49, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, J. T.; Badrealam, K. F.; Shibu, M. A.; Kuo, C. H.; Huang, C. Y.; Chen, B. C.; Lin, Y. M.; Viswanadha, V. P.; Kuo, W. W.; Huang, C. Y. Eriobotrya japonica ameliorates cardiac hypertrophy in H9c2 cardiomyoblast and in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Environmental toxicology 2018, 33, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, D. S.; Eun, J. S.; Jeon, H. Anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive properties of the leaves of Eriobotrya japonica. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2011, 134, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mall, G. K.; Mishra, P. K.; Prakash, V. Antidiabetic and hypolipidemic activity of Gymnema sylvestre in alloxan induced diabetic rats. Global Journal of Biotechnology & Biochemistry 2009, 4, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bishayee, A.; Chatterjee, M. Hypolipidaemic and antiatherosclerotic effects of oral Gymnema sylvestre R. Br. Leaf extract in albino rats fed on a high fat diet. Phytotherapy research 1994, 8, 118–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwan, P. V.; Margaret, I.; Ramakrishna, S. Influence of Gymnema sylvestre on inflammation. Inflammopharmacology 1995, 3, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwalewa, E. O.; Adewale, I. O.; Taiwo, B. J.; Arogundade, T.; Osinowo, A.; Daniyan, O. M.; Adetogun, G. E. Effects of Harungana madagascariensis stem bark extract on the antioxidant markers in alloxan induced diabetic and carrageenan induced inflammatory disorders in rats. Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine 2008, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tom, E. N. L.; Nankia, F. D.; Nyunaï, N.; Thernier, C. G.; Demougeot, C.; Dimo, T. Myocardial potency of aqueous extract of Harungana madagascariensis stem bark against isoproterenol-induced myocardial damage in rats. Universal Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oboh, G.; Akomolafe, T.L.; Adefegha, S.A.; Adetuyi, A.O. Antioxidant and modulatory effect of ethanolic extract of Madagascar Harungana (Harungana madagascariensis) bark on cyclophosphamide induced neurotoxicity in rats. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis 2010, 18, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatachalam, T.; Kumar, V. K.; Selvi, P. K.; Maske, A. O.; Anbarasan, V.; Kumar, P. S. Antidiabetic activity of Lantana camara Linn fruits in normal and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Pharm. Res. 2011, 4, 1550–1552. [Google Scholar]

- Kalita, S.; Kumar, G.; Karthik, L.; Rao, K. V. B. A Review on Medicinal Properties of Lantana camara Linn. Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology 2012, 5, 711–715. [Google Scholar]

- Jawonisi, I. O.; Adoga, G. I. Hypoglycaemic and hypolipidaemic effect of extract of Lantana camara Linn. leaf on alloxan diabetic rats. J. Nat. Sci. Res. 2015, 5, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, S.; Latha, R.; Anaswara, R. N.; Jincy, T. C.; Muhammed Shibli, P. C.; Suresh, A. Anti-hyperglycemic and anti-oxidant activities of ethanolic extract of Lantana camara leaves. International Journal of Frontiers in Life Science Research 2021, 1, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, L.; Sehgal, R.; Ojha, S. (2005). Evaluation of antimotility effect of Lantana camara L. var. acuelata constituents on neostigmine induced gastrointestinal transit in mice. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2005, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobson, P. G. M.; Afangideh, E. U.; Okon, O. E.; Akpan, M. O.; Tom, E. J.; Usen, R. F. Effect of Ethanol Leaf Extract of Lantana camara on Fasting Blood Glucose, Body Weight and Kidney Function Indices of Alloxan-Induced Diabetic Albino Wistar Rats. Asian Journal of Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology 2024, 16, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K. S.; Bhowmik, D. Traditional medicinal uses and therapeutic benefits of Momordica charantia Linn. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research 2010, 4, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Xu, L.; Xu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wei, L.; Li, X.; Song, W. Antidiabetic effect of Momordica charantia saponins in rats induced by high-fat diet combined with STZ. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology 2020, 43, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, P.; Khan, J. T.; Soultana, M.; Hunter, L.; Chowdhury, S.; Priyanka, S. K.; Paul, S. R.; Flatt, P. R.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. Insulin secretory actions of polyphenols of Momordica charantia regulate glucose homeostasis in alloxan-induced type 2 diabetic rats. RPS Pharmacy and Pharmacology Reports 2024, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abas, R.; Othman, F.; Thent, Z. C. Protective Effect of Momordica charantia Fruit Extract on Hyperglycaemia-Induced Cardiac Fibrosis. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2014, 2014, 429060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.; Cartwright, T.; Provost, J.; Bailey, C. J. Hypoglycaemic effect of Momordica charantia extracts. Planta medica 1990, 56, 426–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, V.; Agarwal, S. K.; Ansari, J. A.; Mahdi, A. A.; Srivastava, A. K. Antidiabetic potential of Musa paradisiaca in Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Phytopharmacol. 2014, 3, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekiya, T. A.; Shodehinde, S. A.; Aruleba, R. T. Anti-hypercholesterolemic effect of unripe Musa paradisiaca products on hypercholesterolemia-induced rats. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science 2018, 8, 090–097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulser, T. Antiulcer activity of Musa paradisiaca [banana] tepal and skin extracts in ulcer induced albino mice. Malaysian journal of analytical sciences 2016, 20, 1203–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, O. M.; Abd El-Twab, S. M.; Al-Muzafar, H. M.; Adel Amin, K.; Abdel Aziz, S. M.; Abdel-Gabbar, M. Musa paradisiaca L. leaf and fruit peel hydroethanolic extracts improved the lipid profile, glycemic index and oxidative stress in nicotinamide/streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Veterinary medicine and science 2021, 7, 500–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Mediratta, P. K.; Singh, S.; Sharma, K. K.; Shukla, R. Antidiabetic, antihypercholesterolaemic and antioxidant effect of Ocimum sanctum (Linn) seed oil. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2006, 44, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Suanarunsawat, T.; Boonnak, T.; Ayutthaya, W. N.; Thirawarapan, S. Anti-hyperlipidemic and cardioprotective effects of Ocimum sanctum L. fixed oil in rats fed a high fat diet. Journal of basic and clinical physiology and pharmacology 2010, 21, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Majumdar, D. K.; Rehan, H. M. S. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory potential of fixed oil of Ocimum sanctum (Holybasil) and its possible mechanism of action. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 1996, 54, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, J. M. A.; Ojo, O. O.; Ali, L.; Rokeya, B.; Khaleque, J.; Akhter, M.; Flatt, P. R.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A. Actions underlying antidiabetic effects of Ocimum sanctum leaf extracts in animal models of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. European Journal of Medicinal Plants 2015, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, J. M. A.; Ali, L.; Khaleque, J.; Akhter, M.; Flatt, P. R.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A. Aqueous extracts of husks of Plantago ovata reduce hyperglycaemia in type 1and type 2 diabetes by inhibition of intestinal glucose absorption. British Journal of Nutrition 2006, 96, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, D.; Sibi, G. Pterocarpus marsupium for the treatment of diabetes and other disorders. J. Comp. Med. Alt. Healthcare 2019, 9, 555754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekala, S.; Mchenga, S. S. S.; R. , S. Antidiabetic effect of Pterocarpus marsupium seed extract in gabapentin induced diabetic rats. International Journal of Basic & Clinical Pharmacology 2020, 9, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M. C.; Dorababu, M.; Prabha, T.; Kumar, M. M.; Goel, R. K. Effects of Pterocarpus marsupium on NIDDM-induced rat gastric ulceration and mucosal offensive and defensive factors. Indian journal of pharmacology 2004, 36, 296–302. [Google Scholar]

- Halagappa, K.; Girish, H. N.; Srinivasan, B. P. The study of aqueous extract of Pterocarpus marsupium Roxb. on cytokine TNF-α in type 2 diabetic rats. Indian journal of pharmacology 2010, 42, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharib, E.; Kouhsari, S. M. Study of the antidiabetic activity of Punica granatum L. fruits aqueous extract on the alloxan-diabetic wistar rats. Iranian journal of pharmaceutical research: IJPR 2019, 18, 358–368. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghipour, A.; Eidi, M.; Ilchizadeh Kavgani, A.; Ghahramani, R.; Shahabzadeh, S.; Anissian, A. Lipid lowering effect of Punica granatum L. peel in high lipid diet fed male rats. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2014, 2014, 432650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A. K.; Mandal, S. C.; Banerjee, S. K.; Sinha, S.; Das, J.; Saha, B. P.; Pal, M. Studies on antidiarrhoeal activity of Punica granatum seed extract in rats. Journal of ethnopharmacology 1999, 68, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, H. A.; Ojo, O. O.; Flatt, P. R.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A. Antidiabetic actions of aqueous bark extract of Swertia chirayita on insulin secretion, cellular glucose uptake and protein glycation. Journal of Experimental and Integrative Medicine 2014, 4, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadayat, K.; Marasini, B. P.; Gautam, H.; Ghaju, S.; Parajuli, N. Evaluation of the alpha-amylase inhibitory activity of Nepalese medicinal plants used in the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Clinical Phytoscience 2020, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, H. A. J.; Ojo, O. O.; Flatt, P. R.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A. Aqueous bark extracts of Terminalia arjuna stimulates insulin release, enhances insulin action and inhibits starch digestion and protein glycation in vitro. Austin Journal of Endocrinology and Diabetes 2014, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kanthe, P. S.; Patil, B. S.; Das, K. K. Terminalia arjuna supplementation ameliorates high fat diet-induced oxidative stress in nephrotoxic rats. Journal of Basic and Clinical Physiology and Pharmacology 2022, 33, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, P.; Hannon-Fletcher, M. P.; Flatt, P. R.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A. Effects of 22 traditional anti-diabetic medicinal plants on DPP-IV enzyme activity and glucose homeostasis in high-fat fed obese diabetic rats. Bioscience Reports 2021, 41, BSR20203824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, F.; Parveen, A.; Singh, S.; Gondal, R.; Hussain, M. E.; Fahim, M. Improvement in myocardial function by Terminalia arjuna in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats: possible mechanisms. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 18, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokar, A.; Masoomi, F.; Sadeghpour, O.; Nassiri-Toosi, M.; Hamedi, S. Potential therapeutic applications for Terminalia chebula in Iranian traditional medicine. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2016, 36, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, G. P. S.; Arulselvan, P.; Kumar, D. S.; Subramanian, S. P. Anti-diabetic activity of fruits of Terminalia chebula on streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Journal of health science 2006, 52, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M. M.; Dhas Devavaram, J.; Dhas, J.; Adeghate, E.; Starling Emerald, B. Anti-hyperlipidemic effect of methanol bark extract of Terminalia chebula in male albino Wistar rats. Pharmaceutical biology 2015, 53, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, D. P.; Ranjan, J.; Murugan, R. K.; Sivanantham, A.; Alagumuthu, M. Exploration of anti-breast cancer effects of Terminalia chebula extract on DMBA-induced mammary carcinoma in Sprague Dawley rats. Future Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2020, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renuka, C.; Ramesh, N.; Saravanan, K. Evaluation of the antidiabetic effect of Trigonella foenum-graecum seed powder on alloxaninduced diabetic albino rats. International Journal of PharmTech Research 2009, 1, 1580–1584. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, W. L.; Li, X. S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y. H.; Wang, Z. L.; Zhang, R. J. Effect of Trigonella foenum-graecum (fenugreek) extract on blood glucose, blood lipid and hemorheological properties in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 16 (Suppl. S1), 422–426. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, A.; Madar, Z. The effect of an ethanol extract derived from fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) on bile acid absorption and cholesterol levels in rats. British Journal of Nutrition 1993, 69, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadiani, A.; Javan, M.; Semnanian, S.; Barat, E.; Kamalinejad, M. Anti-inflammatory and antipyretic effects of Trigonella foenum-graecum leaves extract in the rat. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2001, 75, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amin, Z. M.; Thomson, M.; Al-Qattan, K. K.; Peltonen-Shalaby, R.; Ali, M. Anti-diabetic and hypolipidaemic properties of ginger (Zingiber officinale) in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. British journal of nutrition 2006, 96, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattanathorn, J.; Jittiwat, J.; Tongun, T.; Muchimapura, S.; Ingkaninan, K. Zingiber officinale mitigates brain damage and improves memory impairment in focal cerebral ischemic rat. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine: eCAM 2011, 2011, 429505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, S. H.; Makpol, S.; Abdul Hamid, N. A.; Das, S.; Ngah, W. Z.; Yusof, Y. A. Ginger extract (Zingiber officinale) has anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory effects on ethionine-induced hepatoma rats. Clinics (Sao Paulo, Brazil) 2008, 63, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nain, P.; Saini, V.; Sharma, S.; Nain, J. Antidiabetic and antioxidant potential of Emblica officinalis Gaertn. leaves extract in streptozotocin-induced type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 142, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshy, S. M.; Bobby, Z.; Hariharan, A. P.; Gopalakrishna, S. M. Amla (Emblica officinalis) extract is effective in preventing high fructose diet–induced insulin resistance and atherogenic dyslipidemic profile in ovariectomized female albino rats. Menopause (New York, N.Y.) 2012, 19, 1146–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, P.; Azam, S.; Hannan, J. M. A.; Flatt, P. R.; Wahab, Y. H. A. Anti-hyperglycaemic activity of H. rosa-sinensis leaves is partly mediated by inhibition of carbohydrate digestion and absorption, and enhancement of insulin secretion. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2020, 253, 112647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthaman, K. K.; Saleem, M. T.; Thanislas, P. T.; Prabhu, V. V.; Krishnamoorthy, K. K.; Devaraj, N. S.; Somasundaram, J. S. Cardioprotective effect of the Hibiscus rosa sinensis flowers in an oxidative stress model of myocardial ischemic reperfusion injury in rat. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2006, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umadevi, M.; Rajeswari, R.; Rahale, C. S.; Selvavenkadesh, S.; Pushpa, R.; Kumar, K. S.; Bhowmik, D. Traditional and medicinal uses of Withania somnifera. The pharma innovation 2012, 1, 102–110. [Google Scholar]

- Sarangi, A.; Jena, S.; Sarangi, A. K.; Swain, B. Anti-diabetic effects of Withania somnifera root and leaf extracts on streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Journal of Cell and Tissue Research 2013, 13, 3597–3601. [Google Scholar]

- Visavadiya, N. P.; Narasimhacharya, A. V. Hypocholesteremic and antioxidant effects of Withania somnifera (Dunal) in hypercholesteremic rats. Phytomedicine: international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology 2007, 14, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subash, A. K.; Augustine, A. Hypolipidemic effect of methanol fraction of Aconitum heterophyllum wall ex Royle and the mechanism of action in diet-induced obese rats. Journal of advanced pharmaceutical technology & research 2012, 3, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Ojha, S.; Raish, M. Anti-inflammatory activity of Aconitum heterophyllum on cotton pellet-induced granuloma in rats. J. Med. Plants Res. 2010, 4, 1566–1569. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J. S.; Ruchi, J.; Nilesh, J. Antiobesity potential of Aconitum heterophyllum roots. Int. J. Pharm. Bio Sci. 2019, 10, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Garg, M. A review of traditional use, phytoconstituents and biological activities of Himalayan yew, Taxus wallichiana. Journal of integrative medicine 2015, 13, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitzmann, C. Characteristics and health benefits of phytochemicals. Forschende Komplementärmedizin (2006) 2016, 23, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M. M.; Naeem, M.; Khan, M. M. A.; Uddin, M. Vincristine and vinblastine anticancer catharanthus alkaloids: Pharmacological applications and strategies for yield improvement. Catharanthus roseus: current research and future prospects 2017, 277-307. [CrossRef]

- Khameneh, B.; Eskin, N. M.; Iranshahy, M.; Fazly Bazzaz, B. S. Phytochemicals: a promising weapon in the arsenal against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 10, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, V. Initial and bulk extraction of natural products isolation. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) 2012, 864, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, A. D.; Bhowmik, P.; Banerjee, A.; Das, A.; Ojha, D.; Chattopadhyay, D. Ethnomedicinal wisdom: an approach for antiviral drug development. New look to phytomedicine 2019, 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehelean, C. A.; Marcovici, I.; Soica, C.; Mioc, M.; Coricovac, D.; Iurciuc, S.; Cretu, O. M.; Pinzaru, I. Plant-derived anticancer compounds as new perspectives in drug discovery and alternative therapy. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 26, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailes, B. K. Diabetes mellitus and its chronic complications. AORN journal 2002, 76, 266–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomic, D.; Shaw, J. E.; Magliano, D. J. The burden and risks of emerging complications of diabetes mellitus. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2022, 18, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rena, G.; Hardie, D. G.; Pearson, E. R. The mechanisms of action of metformin. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Bajwa, B. S.; Kuldeep, S.; Kalia, A. N. Anti-inflammatory activity of herbal plants: a review. Int. J. Adv. Pharm. Biol. Chem. 2013, 2, 272–281. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, M.; Dehvari, N.; Öberg, A. I.; Dallner, O. S.; Sandström, A. L.; Olsen, J. M.; Csikasz, R. I.; Summers, R. J.; Hutchinson, D. S.; Bengtsson, T. Improving type 2 diabetes through a distinct adrenergic signaling pathway involving mTORC2 that mediates glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. Diabetes 2014, 63, 4115–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmatullah, M.; Azam, N. K.; Khatun, Z.; Seraj, S.; Islam, F.; Rahman, M. A.; Jahan, S.; Aziz, S. Medicinal plants used for treatment of diabetes by the Marakh sect of the Garo tribe living in Mymensingh 44 district, Bangladesh. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines: AJTCAM 2012, 9, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazarian-Samani, Z.; Sewell, R. D.; Lorigooini, Z.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M. Medicinal plants with multiple effects on diabetes mellitus and its complications: a systematic review. Current diabetes reports 2018, 18, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R. L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, O.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, P.; Ajeet. Anticancer potential of plants and natural products. Am. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 1, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhari, A. S.; Mandave, P. C.; Deshpande, M.; Ranjekar, P.; Prakash, O. Phytochemicals in cancer treatment: From preclinical studies to clinical practice. Frontiers in pharmacology 2020, 10, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, A.; Ramachandran, S.; Gupta, N.; Kaushik, I.; Wright, S.; Srivastava, S.; Prasad, S.; Srivastava, S. K. Role of phytochemicals in cancer prevention. International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 20, 4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adico, M. D.; Bayala, B.; Zoure, A. A.; Lagarde, A.; Bazie, J. T.; Traore, L.; Buñay, J.; Yonli, A. T.; Djigma, F.; Bambara, H. A.; Baron, S.; Simporé, J.; Lobaccaro, J. M. A. In vitro activities and mechanisms of action of anti-cancer molecules from African medicinal plants: a systematic review. American Journal of Cancer Research 2024, 14, 1376–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, A. , Tommonaro, G. Curcumin and cancer. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadgostar, P. Antimicrobial resistance: implications and costs. Infection and drug resistance 2019, 12, 3903–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, H.; Bishnoi, P.; Yadav, A.; Patni, B.; Mishra, A. P.; Nautiyal, A. R. Antimicrobial resistance and the alternative resources with special emphasis on plant-based antimicrobials—a review. Plants 2017, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossiter, S. E.; Fletcher, M. H.; Wuest, W. M. Natural products as platforms to overcome antibiotic resistance. Chemical reviews 2017, 117, 12415–12474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suganya, T.; Packiavathy, I. A. S. V.; Aseervatham, G. S. B.; Carmona, A.; Rashmi, V.; Mariappan, S.; Devi, N. R.; Ananth, D. A. Tackling multiple-drug-resistant bacteria with conventional and complex phytochemicals. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2022, 12, 883839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łopusiewicz, Ł.; Drozłowska, E.; Tarnowiecka-Kuca, A.; Bartkowiak, A.; Mazurkiewicz-Zapałowicz, K.; Salachna, P. Biotransformation of flaxseed oil cake into bioactive camembert-analogue using lactic acid bacteria, Penicillium camemberti and Geotrichum candidum. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; He, N.; Wang, Z.; Fu, X.; Aung, L. H. H.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Cho, J. Y.; Yang, Y.; Yu, T. Functional roles and mechanisms of ginsenosides from Panax ginseng in atherosclerosis. Journal of ginseng research 2021, 45, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir Dar, K.; Hussain Bhat, A.; Amin, S.; Masood, A.; Afzal Zargar, M.; Ahmad Ganie, S. (2016). Inflammation: a multidimensional insight on natural anti-inflammatory therapeutic compounds. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2016, 23, 3775–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellik, Y.; Boukraâ, L.; Alzahrani, H. A.; Bakhotmah, B. A.; Abdellah, F.; Hammoudi, S. M.; Iguer-Ouada, M. Molecular mechanism underlying anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic activities of phytochemicals: an update. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2012, 18, 322–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Du, B.; Xu, B. Anti-inflammatory effects of phytochemicals from fruits, vegetables, and food legumes: A review. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2018, 58, 1260–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaito, A.; Thuan, D. T. B.; Phu, H. T.; Nguyen, T. H. D.; Hasan, H.; Halabi, S.; Abdelhady, S.; Nasrallah, G. K.; Eid, A. H.; Pintus, G. Herbal medicine for cardiovascular diseases: efficacy, mechanisms, and safety. Frontiers in pharmacology 2020, 11, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, I.; Hua, W.; Ting, L.; Mehmood, A.; Jingyi, S.; Duoxia, X.; Yanping, C.; Hongqing, W.; Zhipeng, G.; Kaiqi, Z.; Fang, Y.; Junsong, X. Phytochemicals and inflammatory bowel disease: a review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2022, 60, 1321–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czigle, S.; Bittner Fialova, S.; Tóth, J.; Mučaji, P.; Nagy, M.; on behalf of the OEMONOM. Treatment of gastrointestinal disorders—Plants and potential mechanisms of action of their constituents. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 27, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palombo, E. A. Phytochemicals from traditional medicinal plants used in the treatment of diarrhoea: modes of action and effects on intestinal function. Phytotherapy Research: PTR 2006, 20, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendran, A.; Priyadarshini, M.; Sukumar, D. Phytochemical studies and pharmacological investigations on the flowers of Acacia arabica. Afr. J. Pure Appl. Chem. 2010, 4, 240–242. [Google Scholar]

- Inkoto, C. L.; Ngbolua, K. T. N.; Bokungu, P. E.; Masengo, C. A.; Iteku, J. B.; Tshilanda, D. D.; Tshibangu, D. S. T.; Mpiana, P. T. Phytochemistry and pharmacology of Aframomum angustifolium (Sonn.) K. Schum (Zingiberaceae): a mini review. Asian Res. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 4, 218–233. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, A. J.; Uddin, T. M.; Matin Zidan, B. R.; Mitra, S.; Das, R.; Nainu, F.; Dhama, K.; Roy, A.; Hossain, M. J.; Khusro, A.; Emran, T. B. (2022). Allium cepa: a treasure of bioactive phytochemicals with prospective health benefits. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine: eCAM 2022, 2022, 4586318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Saber Batiha, G.; Magdy Beshbishy, A.; G. Wasef, L.; Elewa, Y. H.; A Al-Sagan, A.; Abd El-Hack, M. E.; Taha, A. E.; M Abd-Elhakim, Y.; Prasad Devkota, H. Chemical constituents and pharmacological activities of garlic (Allium sativum L.): A review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.; González-Burgos, E.; Iglesias, I.; Gómez-Serranillos, M. P. Pharmacological update properties of Aloe vera and its major active constituents. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2020, 25, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, D. O.; Dos Santos Sales, V.; de Souza Rodrigues, C. K.; de Oliveira, L. R.; Lemos, I. C. S.; de Araújo Delmondes, G.; onteiro, Á. B.; do Nascimento, E. P.; Sobreira Dantas Nóbrega de Figuêiredo, F. R.; Martins da Costa, J. G.; Pinto da Cruz, G. M.; de Barros Viana, G. S.; Barbosa, R.; Alencar de Menezes, I. R.; Bezerra Felipe, C. F.; Kerntopf, M. R. Phytochemical analysis and central effects of Annona muricata Linnaeus: possible involvement of the gabaergic and monoaminergic systems. Iranian journal of pharmaceutical research: IJPR 2018, 17, 1306–1317. [Google Scholar]

- Baliga, M. S.; Shivashankara, A. R.; Haniadka, R.; Dsouza, J.; Bhat, H. P. Phytochemistry, nutritional and pharmacological properties of Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam (jackfruit): A review. Food research international 2011, 44, 1800–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, J. S.; Singh, P.; Joshi, G. P.; Rawat, M. S.; Bisht, V. K. Chemical constituents of Asparagus. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2010, 4, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atawodi, S. E.; Atawodi, J. C. Azadirachta indica (neem): a plant of multiple biological and pharmacological activities. Phytochemistry reviews 2009, 8, 601–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keser, S.; Kaygili, O.; Keser, F.; Tekin, S.; Yilmaz, Ö.; Demir, E.; Kirbag, S.; Sandal, S. (2018). Phytochemical Composition, Antiradical, Antiproliferative and Antimicrobial Activities of Capsicum frutescens L. Analytical Chemistry Letters 2018, 8, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H. N. T.; Vuong, Q. V.; Bowyer, M. C.; Scarlett, C. J. Phytochemicals derived from Catharanthus roseus and their health benefits. Technologies 2020, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Dwivedi, J.; Jain, P. K.; Satpathy, S.; Patra, A. Medicinal plants for treatment of cancer: A brief review. Pharmacognosy Journal 2016, 8, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, N. E.; Alcazar Magana, A.; Lak, P.; Wright, K. M.; Quinn, J.; Stevens, J. F.; Maier, C. S.; Soumyanath, A. Centella asiatica - Phytochemistry and mechanisms of neuroprotection and cognitive enhancement. Phytochem. Rev. 2018, 17, 161–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Dey, A.; Koirala, N.; Shaheen, S.; El Omari, N.; Salehi, B.; Goloshvili, T.; Cirone Silva, N. C.; Bouyahya, A.; Vitalini, S.; Varoni, E. M.; Martorell, M.; Abdolshahi, A.; Docea, A. O.; Iriti, M.; Calina, D.; Les, F.; López, V.; Caruntu, C. Cinnamomum species: bridging phytochemistry knowledge, pharmacological properties and toxicological safety for health benefits. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12, 600139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksoud, S.; Abdel-Massih, R. M.; Rajha, H. N.; Louka, N.; Chemat, F.; Barba, F. J.; Debs, E. Citrus aurantium L. active constituents, biological effects and extraction methods. an updated review. Molecules 2021, 26, 5832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimek-Szczykutowicz, M.; Szopa, A.; Ekiert, H. (2020). Citrus limon (Lemon) phenomenon—a review of the chemistry, pharmacological properties, applications in the modern pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetics industries, and biotechnological studies. Plants (Basel, Switzerland) 2020, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuloria, S.; Mehta, J.; Chandel, A.; Sekar, M.; Rani, N. N. I. M.; Begum, M. Y.; Subramaniyan, V.; Chidambaram, K.; Thangavelu, L.; Nordin, R.; Wu, Y. S.; Sathasivam, K. V.; Lum, P. T.; Meenakshi, D. U.; Kumarasamy, V.; Azad, A. K.; Fuloria, N. K. A comprehensive review on the therapeutic potential of Curcuma longa Linn. in relation to its major active constituent curcumin. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2022, 13, 820806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xu, C.; Li, X. Biological activities of extracts from loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.): a review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, P.; Mishra, B. N.; Sangwan, N. S. Phytochemical and pharmacological properties of Gymnema sylvestre: an important medicinal plant. BioMed research international 2014, 2014, 830285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Happi, G. M.; Tiani, G. L. M.; Gbetnkom, B. Y. M.; Hussain, H.; Green, I. R.; Ngadjui, B. T.; Kouam, S. F. Phytochemistry and pharmacology of Harungana madagascariensis: mini review. Phytochemistry Letters 2020, 35, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, N. M. Lantana camara Linn. chemical constituents and medicinal properties: a review. Scholars Academic Journal of Pharmacy 2013, 2, 445–448. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, S.; Shen, M.; Zhang, F.; Xie, J. Recent advances in Momordica charantia: functional components and biological activities. International journal of molecular sciences 2017, 18, 2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajijolakewu, K. A.; Ayoola, A. S.; Agbabiaka, T. O.; Zakariyah, F. R.; Ahmed, N. R.; Oyedele, O. J.; Sani, A. A review of the ethnomedicinal, antimicrobial, and phytochemical properties of Musa paradisiaca (plantain). Bulletin of the National Research Centre 2021, 45, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliga, M. S.; Jimmy, R.; Thilakchand, K. R.; Sunitha, V.; Bhat, N. R.; Saldanha, E.; Rao, S.; Rao, P.; Arora, R.; Palatty, P. L. Ocimum sanctum L (Holy Basil or Tulsi) and its phytochemicals in the prevention and treatment of cancer. Nutrition and cancer 2013, 65, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P. R. T.; Vandana, K. V.; Prakash, S. Antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties of Plantago ovata Forssk. leaves and seeds against periodontal pathogens: An: in vitro: study. AYU (An International Quarterly Journal of Research in Ayurveda) 2018, 39, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, D.; Singh, V.; Ali, M. Phytochemical and pharmacological profile of Pterocarpus marsupium: A review. Pharma Innov. J. 2016, 5, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Moga, M. A.; Dimienescu, O. G.; Bălan, A.; Dima, L.; Toma, S. I.; Bîgiu, N. F.; Blidaru, A. Pharmacological and therapeutic properties of Punica granatum phytochemicals: possible roles in breast cancer. Molecules 2021, 26, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjha, M. M. A. N.; Shafique, B.; Wang, L.; Irfan, S.; Safdar, M. N.; Murtaza, M. A.; Nadeem, M.; Mahmood, S.; Mueen-ud-Din, G.; Nadeem, H. R. A comprehensive review on phytochemistry, bioactivity and medicinal value of bioactive compounds of pomegranate (Punica granatum). Advances in Traditional Medicine 2021, 23, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Van Staden, J. A Review of Swertia chirayita (Gentianaceae) as a Traditional Medicinal Plant. Front Pharmacol. 2016, 6, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amalraj, A.; Gopi, S. Medicinal properties of Terminalia arjuna (Roxb.) Wight & Arn.: A review. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2016, 7, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.; Yadav, P. P.; Gill, V.; Vasudeva, N.; Singla, N. arjuna a sacred medicinal plant: phytochemical and pharmacological profile. Phytochemistry Reviews 2009, 8, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, A.; Bhattacharyya, S. K.; Chattopadhyay, R. R. The development of Terminalia chebula Retz.(Combretaceae) in clinical research. Asian Pacific journal of tropical biomedicine 2013, 3, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagulapalli Venkata, K. C.; Swaroop, A.; Bagchi, D.; Bishayee, A. A small plant with big benefits: Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum Linn.) for disease prevention and health promotion. Molecular nutrition & food research 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q. Q.; Xu, X. Y.; Cao, S. Y.; Gan, R. Y.; Corke, H.; Beta, T.; Li, H. B. Bioactive compounds and bioactivities of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Foods (Basel, Switzerland) 2019, 8, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M. R.; Islam, M. N.; Islam, M. R. Phytochemistry, pharmacological activities and traditional uses of Emblica officinalis: A review. International Current Pharmaceutical Journal 2016, 5, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkurnain, E. I.; Ramli, S.; Ali, A. A.; James, R. J.; Kamarazaman, I. S.; Halim, H. The Phytochemical and Pharmacological Effects of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis: A Review. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Investigation 2023, 13, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, S.; Muhammad, G.; Hussain, M. A.; Altaf, M.; Bukhari, S. N. A. (2020). Withania somnifera L.: Insights into the phytochemical profile, therapeutic potential, clinical trials, and future prospective. Iranian journal of basic medical sciences 2020, 23, 1501–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, N. J.; Hamid, A.; Ahmad, M. Pharmacologic overview of Withania somnifera, the Indian Ginseng. Cellular and molecular life sciences 2015, 72, 4445–4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, S. K.; Jain, D.; Patel, D. K.; Sahu, A. N.; Hemalatha, S. Antisecretory and antimotility activity of Aconitum heterophyllum and its significance in treatment of diarrhea. Indian Journal of Pharmacology 2014, 46, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saravanan, S.; Hari, R.; Sekar, K. Anti-proliferative potentials of Aconitum heterophyllum Root Extract in Human Breast cancer (MDA-MB-231) cell lines-Genetic and Antioxidant enzyme approach. Avicenna Journal of Medical Biotechnology 2023, 15, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F. S.; Weng, J. K. Demystifying traditional herbal medicine with modern approach. Nature plants 2017, 3, 17109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Gairola, S.; Sharma, Y. P.; Gaur, R. D. Ethnomedicinal plants used to treat skin diseases by Tharu community of district Udham Singh Nagar, Uttarakhand, India. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2014, 158 Pt A, 140–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, P.; Azam, S.; Seidel, V.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A. In vitro and in vivo antihyperglycemic activity of the ethanol extract of Heritiera fomes bark and characterization of pharmacologically active phytomolecules. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2022, 74, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasim, N.; Sandeep, I. S.; Mohanty, S. Plant-derived natural products for drug discovery: current approaches and prospects. The Nucleus 2022, 65, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, P.; Khan, J. T.; Chowdhury, S.; Reberio, A. D.; Kumar, S. , Seidel, V.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A.; Flatt, P. R. Plant-based diets and phytochemicals in the management of diabetes mellitus and prevention of its complications: a review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L. Plant based drugs and medicines. Rain tree Nutrition Inc. 2000, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bent, S.; Ko, R. Commonly used herbal medicines in the United States: a review. The American journal of medicine 2004, 116, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vhora, N.; Naskar, U.; Hiray, A.; Kate, A. S.; Jain, A. Recent advances in in-vitro assays for type 2 diabetes mellitus: an overview. Review of Diabetic Studies 2020, 16, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Medicinal plants | Parts | Ethnomedicinal uses | Form of extract | Experimental model | Pharmacological action | Dose | Duration | References(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acacia arabica | Bark, leaves and seeds | Diabetes, leucorrhoea, diarrhea and dysentery, skin, stomach and tooth disorders | Hot water extract | High-fat-diet induced obese rats | Decreases blood glucose levels, improves glucose homeostasis and β-cell functions, increases insulin release, enhances glucose tolerance and glucose uptake | 0.25 g/kg | 9 days | [52,53] |

| Chloroform extract | Streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats | Reduces serum glucose, insulin resistance, TC, LDL-C, TG, MDA and increases plasma insulin, HDL-C | 0.1, 0.2 g/kg | 21 days | [54] | |||

| Aframomum angustifolium | Seeds | Cardiovascular disease, diabetes, inflammation, stomachache, wound healing, snakebite, diarrhea | Ethanol extract | Bromate-induced Wister rats | Improves ALP (alkaline phosphate) activity, increases liver tissue, decreases Na⁺ and increases K⁺ | 0.75 g/kg | 10 days | [55,56]y |

| Allium cepa | Onion skin and bulbs | Diabetes, bronchitis, hypertension, skin infections, swelling | Ethyl alcohol onion skin (EOS) extract | Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats | Lowers blood glucose, increases plasma insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity, improves glucose uptake, lowers cholesterol | 0.5 g/kg | 14 days | [4,57,58] |

| Aqueous extract (Raw onion bulb) | STZ -induced diabetic mice | Improves oral glucose tolerance, reduces fasting blood glucose levels and reduces TC, LDL and increases HDL Levels | 30 g/kg | - | [59,60] | |||

| Allium sativum | Leaves, flowers, cloves, and bulbs | Hypertension, diabetes, fever, dysentery, bronchitis, intestinal worms | Raw garlic extract | STZ -induced diabetic rats | Lowers serum glucose, reduces fasting blood glucose, cholesterol and triglyceride levels, reduces urinary protein levels and increases plasma insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity. | 0.5 g/kg intraperitoneally (i.p.) | 49 days | [4,61,62] |

| Decoctions | STZ -induced diabetic mice | Reduces hyperphagia, polydipsia, and body weight | 6.25% (by weight of the diet) | 40 days | [63] | |||

| Aloe barbadensis Mill. (Syn. Aloe vera) | Clear gel, green part of the leaf and yellow latex | Diabetes, dermatitis, headache, insect bites, viral infection, arthritis, gum sore, wound healing, inflammation and urine related problems | GelExtract | Alloxan-induced Wistar albino diabetic rats | Decreases serum glucose, TG, TC, MDA levels, increases serum nitric oxide and total antioxidant capacity. | 0.5 mL /day | 42 days | [64,65] |

| Ethanolic extract | TNBS-(Trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid)-induced Wister rats | Reduces hyperemia, attenuates colon inflammation, reduces the increased levels of TNF-α, IL-6, NO, MPO, and MPA. | 0.2, 0.4 g/kg | 7 days | [66] | |||

| Annona muricata | Leaves, bark, fruit, and seed | Fever, stomach pain, worms, diabetes and vomiting | Aqueous extract | STZ -induced diabetic rats | Reduces AST, ALT activity and lowers blood glucose, serum creatinine, MDA, nitrite and LDL-cholesterol levels | 0.1, 0.2 g/kg | 28 days | [67] |

| Artocarpus heterophyllus | Fruits, leaves and bark | Hypertension, diabetes, cancer, anemia, asthma, dermatosis and diarrhea | Ethyl acetate fraction | STZ -induced diabetic rats | Reduces fasting blood glucose, lowers serum glucose, cholesterol and TG levels. | 0.02 g/kg | 35 days | [68,69] |

| Asparagus adscendes | Dried rhizome | Diarrhea, gonorrhea, dysuria, weakness, lean and thinness, erectile dysfunction, diabetes, piles, cough and dysentery | Aqueous extract | 3T3-L1 adipocytes cell | Increases glucose uptake | 0.005 g/ml | --------- | [70,71] |

| BRIN-BD11 cells | Stimulates insulin secretion | |||||||

| Azadirachta indica | Leaves, flowers, seeds, fruits, roots and bark | Diabetes, malaria, skin diseases, cardiovascular diseases, intestinal worms | Aqueous extract | STZ -induced diabetic rats and high-fat-diet-induced diabetic rats | Improves body weight, decreases blood glucose, lowers TC, TG, LDL, VLDL levels, improves HDL levels, insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance, increases insulin secretion, regenerates insulin, improves pancreatic β-cell functions, enhances glucose uptake, inhibits α-amylase and α-glucosidase activity. | 0.5 g/kg (b.w.) and 0.4 g/kg (b.w.) | 14 days and 30 days | [4,58,72,73] |

| Ethanol extract | STZ -induced diabetic rats | Reduces the total cholesterol, LDL- and VLDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, and total lipids | 0.5 g/kg p.o. (per os) | 7 days | [74] | |||

| Capsicum frutescens | Fruit, seed and leaves | Diabetes, bronchitis, burning feet, arthritis, stomach ache, diarrhea and dysentery. | Dietary supplements | Alloxan-induced diabetic Wistar rats | Decreases AST, ALT, ALP , GGT, serum uric acid, creatinine, total cholesterol, fasting blood glucose levels, increases HDL cholesterol | 1g and 2g/ 99 and 98 g of animal food | 21 days | [75] |

| Aqueous and methanol extracts | Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella typhimurium, Vibrio cholera, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Shigella dysenteriae | Lowers MIC, shows antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella typhimurium, and Vibrio cholera. | 10 g/100 and 60 mL | 48h | [76] | |||

| Catharanthus roseus | Leaf, root, shoot and stem | Skin problems, (dermatitis, eczema, acne) and diabetes | Leafpowder suspension | STZ -induced diabetic Wistar rats | Improves body weight, decreases plasma glucose, TG, TC, LDL-C and VLDL-C levels, increases HDL-C | 0.1 g/kg | 60 days | [77] |

| Dichloromethane: methanol extract (DCMM) | STZ -induced diabetic rats | Improves enzymatic activities of glycogen synthase, glucose 6-phosphate-dehydrogenase, succinate dehydrogenase, malate dehydrogenase, increases metabolization of glucose and normalizes increased lipid peroxidation. | 0.5 g/kg | 7 days | [78] | |||

| Centella asiatica | Leaves and stems | Inflammation, diabetes, dysentery, hysteron-epilepsy, leprosy, rheumatism, dizziness, hemorrhoids, diarrhea, tuberculosis, skin lesions and asthma. | Ethanol extract | STZ-induced obese diabetic Sprague Dawley rats | Lowers blood glucose levels, increases serum insulin levels, decreases lipid metabolism | 0.3 g/kg | 28 days | [79] |

| Methanol, acetone andchloroform extract | Shigella dysenteriae | Inhibits Shigella dysenteriae | 0.001 g/mL | - | [80] | |||

| Cinnamomum verum | Leaves, bark, flowers, fruits and roots | Diabetes, bacterial infection, inflammation and cancer. | Lyophilized aqueous extract | Alloxan-diabeticrats | Improves body weight, food intake (FI) and food efficiency ratio (FER), lowers FBG, TC, LDL-C, TG levels and induces HDL-C levels. | 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 1.2 g/kg | 30 days | [81] |

| Cinnamon powder | STZ-induced Sprague-Dawley diabetic rats | Increases CYP2D1 enzyme activity, hepatic clearance, and decreases fasting blood glucose. | 0.3 g/kg | 14 days | [82] | |||

| Citrus aurantium | Peel, flower, leaf, fruit and fruit juice | Diabetes, insomnia, indigestion, and heartburn | Ethanol extract | High fat diet-induced obese C57BL/6 mice and Alloxan-induced diabetic rats | Decreases body weight, adipose tissue weight, and serum cholesterol levels, decreases blood glucose, TG, TCH, LDL and VLDL levels, increases HDL, and insulin secretion from β-cells. | 0.1 g/kg/day and 0.3, 0.5 g/kg b.w. | 56 days and 21 days | [4,83,84] |

| Citrus limon | Fruit, stem, leaves juice and peel | Scurvy, sore throats, phlegm, fevers, cough, rheumatism, hypertension and diabetes | Hexane extract | Alloxan-induced diabetic rats and 3T3L1-adipocytes cells | Reduces blood glucose levels, increases insulin secretion, enhances glucose utilization, inhibits α-amylase activity, increases PPARγ, (Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptors Gamma), GLUT4 (Glucose Transporter 4), DGAT-1 (diacylglycerol o-acyltransferase 1) levels, decreases IL-6, and restores triglyceride adipocytes. | 0.01 g/kg and 0.00056 g/ml | 4 days and 48 | [4,85,86] |

| Dietary supplements | Atherogenic diet-fed rabbits | Increases total cholesterol and ApoB100 (apolipoproteins), decreases LDL levels. | 5 cc (cubic centimeter) lemon juice and 1 g powder | 60 days | [87] | |||

| Curcuma longa | Rhizome (underground stem) | Biliary disorders, anorexia, cough, diabetic wounds, hepatic disorders, rheumatism and sinusitis | Dietary supplement | STZ-induced diabetic rats | Decreases blood cholesterol, triglyceride, phospholipids, renal cholesterol and triglyceride levels | 0.5% (Curcumin containing diet) | 56 days | [88,89] |

| Suspension | STZ-induced diabetic rats | Decreases plasma glucose, body weight, diabetic proteinuria, polyuria, lipid peroxidation, increases serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen and GSH, SOD, and catalase activities. | 0.015 and 0.03 g/kg, p.o. | 14 days | [90] | |||

| Eriobotrya japonica | Leaves andseeds | Headache, low back pain, phlegm, asthma, dysmenorrhoea, cough, chronic bronchitis diabetes and skin diseases | Ethanolic and methanolic extract | Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima fatty (OLETF) rats, male KK-A(y) diabetic mice and Streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice | Decreases blood glucose, improves glucose tolerance, reduces insulin resistance, lowers HbA1c, TG, TC, increases GLUT4 (glucose transporter 4), PPARα (peroxisome proliferator activated receptor α), decreases body weight, increases insulin and leptin levels, enhances ApoA-1 (apolipoprotein A-1) levels. | 8 g/kg and 0.5 or 1.0 g/kg | 28 days | [4,91,92] |

| Aqueous extract | Spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) | Reduces degree of tissue deterioration, abnormalarchitecture and interstitial spaces, decreases the size of H9c2 cells, inhibits Ang-II-induced cardiac hypertrophy, attenuates gene expression and decreases body weight. | 0.1, 0.3 g/kg | 56 days | [93] | |||

| Methanolic extract | LPS (lipopolysaccharide)-induced mice | Reduces NF-κB activation, NO and iNOS expression, inhibits COX-2 TNF-α and IL-6. | 0.25, 0.5 g/kg p.o. | 24 h | [94] | |||

| Gymnema sylvestre | Leaves | Anti-periodic, stomachic, laxative, diuretic, cough remedy, snakebite, biliousness, parageusia, and furunculosis | Aqueous extract | Alloxan-induced diabetic rats | Reduces blood glucose, TC and TG levels, increases HDL-C levels. | 0.4, 0.6, 0.8 g/kg | 30 days | [95] |

| Ethanol extract | High-fat-fed Albino rats | Decreases TG, TC, VLDL, LDL, increases HDL lipoprotein fraction. | 0.025, 0.05, 0.1 g/kg p.o. | 14 days | [96] | |||

| Aqueous extract | Carrageenan-induced Wistar rats | Increases γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, reduces lipid peroxidation and inhibits paw edema moderately. | 0.2, 0.4, 0.6 g/kg p.o. | [97] | ||||

| Harungana madagascariensis | Bark andleaves | Gastrointestinal disorders, cardiovascular disorders, malaria, leprosy, anemia, tuberculosis, fever, angina, nephrosis, dysentery, bleeding, piles syphilis, gonorrhea and parasitic skin diseases | Ethanolic extract | Alloxan-induced diabetic rats | Reduces blood glucose levels, edema formation, edema size and MDA, SOD and CAT activities, increases GSH levels. | 0.025, 0.05, 0.1 g/kg i.p. | 3 days | [98] |

| Aqueous extract | Isoproterenol (ISO)-induced Wistar rats | Reduces heart weight and the ratio of heart weight to body weight, reduces serum LDH, AST, ALT, MDA levels, myocytesdegeneration, edema and inflammation, increases myocardial GSH levels | 0.2, 0.4 g/kg p.o. | 7 days | [99] | |||

| Ethanolic extract | Cyclophosphamide-induced rats | Decreases MDA levels, AST, ALT, ALP activities and total bilirubin content | 0.5 and 1.0 % | 14 days | [100] | |||

| Lantana camara | Leaves | Cancers, chicken pox, asthma, eczema, rashes, boils, cold, sore throat, fever, headaches, toothaches and malaria | Methanolic extract | STZ-induced diabetic rats | Reduces blood glucose levels and improves body weight, HbA1c profile, glucose tolerance and regeneration of liver cells | 0.1, 0.2 g/kg | 21 days | [4,101,102] |

| Ethanolic extract (70%) and n-butanol and aqueous fraction | Alloxan-and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats | Lowers blood glucose, TC, and TG levels, SGOT (Serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase,) SGPT (Serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase), SALP (serum alkaline phosphatase), LPO levels, increases SOD, CAT, GPx levels | 0.8, 0.2, and 0.4 g/kg | 28 days and 21 days | [103,104] | |||

| Methanolic extract and ethanolic extract | Neostigmine-induced mice and Alloxan-induced diabetic Albino Wistar rats | Decreases intestinal transit and reduces defecations, decreases blood glucose, creatinine and uric acid, improves body weight | 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1 g/kg i.p. and 0.6, 0..8, 1 g/kg b.w | 10 days and 21 days | [105,106] | |||

| Momordica charantia | Fruits, vines, leaves and roots | Asthma, tumors, diabetes, skin infections, GI disorders and hypertension | Ethanolic extract | Alloxan-induced type 2 diabetic rats | Increases insulin release, inhibits glucose absorption, improves oral glucose tolerance, FBG, plasma insulin and elevates intestinal motility. | 0.5 g/kg | 15 days | [107,108,109] |

| Aqueous extract | STZ-induced male Sprague-Dawley rats/mice | Reduces blood glucose, increases antioxidant enzyme activities in cardiac tissues (SOD, GSH, CAT), and decreases hydroxyproline and size of cardiomyocytes | 1.5g/kg | 28 days | [110,111] | |||

| Musa paradisiaca | Stalk, peel, pulp, roots, stem and leaf | Diarrhoea, dysentery, intestinal lesions in ulcerative colitis, diabetes, sprue, uremia, nephritis, gout, hypertension, wound healing, inflammation, headache and cardiac diseases | Ethanolic extracts, hexane and chloroform fractions | STZ-induced diabetic rats | Lowers blood sugar levels | 0.1, 0.5 g/kg | 3 days | [112] |

| Dietary supplement | Hypercholesterolemia-induced rats | Increases HDL and reduces TG, TC, LDL levels, reduces plasma lipid peroxidation (LPO), AST, ALT and ALP, inhibits MDA production | 100, 200 g/kg | 21 days | [113] | |||

| Methanolic extract | Ulcer-induced albino mice | Reduces ulcer index and gastric juice volume, increases gastric juice pH and gastric wall mucus. | 0.1 g/kg | 7 days | [114] | |||

| Hydro-ethanolic extract | Nicotinamide (NA)/ STZ-induced diabetic rats | Decreases elevated fasting serum glucose, post-prandial serum glucose, TC, TG, LDL-C, VLDL-C levels, increases serum insulin, liver glycogen, HDL-cholesterol, homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistance (HOMA-IS), and HOMA-β cell function, improves elevated cardiovascular risk indices. | 0.1 g/kg/day | 28 days | [115] | |||

| Ocimum sanctum | Leaves, stem, flower, root, seeds and whole plant | Catarrhal bronchitis, bronchial asthma, dysentery, dyspepsia, skin diseases, chronic fever, hemorrhage, helminthiasis and ringworm | Petroleum ether extract (OSSO; Ocimum sanctum Linn. seed oil) | Cholesterol-fed male albino rabbits | Decreases serum cholesterol, triacylglycerol, LDL and VLDL-cholesterol, decreases lipid peroxidation, increases GSH levels | 0.8 g/kg bw/day | 28 days | [116] |