Submitted:

27 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

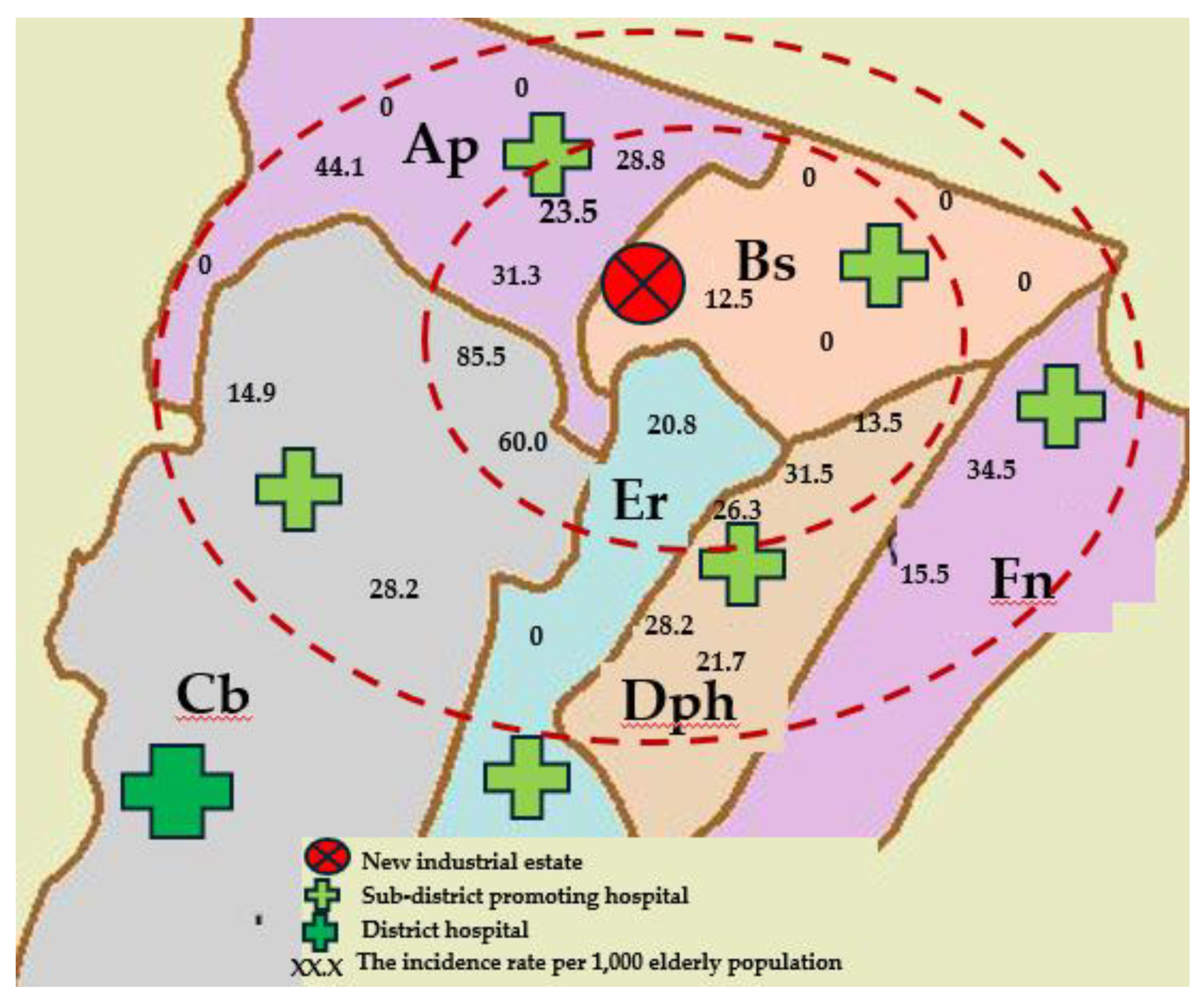

2.1. Study Area: Communities Near a New Industrial Estate

2.2. Measurements of Air Pollutants

2.3. Hospitalization Data

2.4. Statistical Data Analysis

2.5. Ethics Statement

3. Results

3.1. Study Area and Measured Air Pollutants

3.2. Descriptive Statistics of the Study Population

3.3. The Association Between the Incidence of LRTI Among Elderly and Living in Communities Near the New Industrial Estate

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, Y.; Song, P.; Lin, S.; Peng, L.; Li, Y.; Deng, Y.; Deng, X.; Lou, W.; Yang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Xiang, D.; Hu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhai, Z.; Zhang, D.; Dai, Z.; Gao, J. Global Burden of Respiratory Diseases Attributable to Ambient Particulate Matter Pollution: Findings From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Frontiers of Public Health 2021, 9, 740800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, E. A.; Dey, S.; Pal, S. Chronic respiratory disease mortality and its associated factors in selected Asian countries: evidence from panel error correction model. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Requia, W. J.; Adams, M. D.; Koutrakis, P. Association of PM2.5 with diabetes, asthma, and high blood pressure incidence in Canada: A spatiotemporal analysis of the impacts of the energy generation and fuel sales. Science of the Total Environment 2017, 584-585, 1077–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luong, L. T. M.; Dang, T. N.; Thanh Huong, N. T.; Phung, D.; Tran, L. K.; Van Dung, D.; Thai, P. K. Particulate air pollution in Ho Chi Minh city and risk of hospital admission for acute lower respiratory infection (ALRI) among young children. Environmental Pollution 2019, 257, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bano, R.; Khayyam, U. Industrial air pollution and self-reported respiratory and irritant health effects on adjacent residents: a case study of Islamabad Industrial Estate (IEI). Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health 2021, 14, 1709–1722. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W.-W.; Boonhat, H.; Lin, R.-T. Incidence of Respiratory Symptoms for Residents Living Near a Petrochemical Industrial Complex: A Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, R.; Radon, K.; von Ehrenstein, O. S.; Cifuentes, S.; Muñoz, D. M.; Berger, U. Proximity to mining industry and respiratory diseases in children in a community in Northern Chile: A crosssectional study. Herrera et al. Environmental Health 2016, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, E. A.; Dey, S.; Pal, S. The effect of industry-related air pollution on lung function and respiratory symptoms in school children. Environmental Health 2018, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Isa, K. N. M.; Som, N. A. N. M.; Jalaludin, J.; Hashim, N. H. Effects of Residential Proximity to Industrial Zone on Respiratory Symptoms among Residents in Parit Raja, Batu Pahat. Malaysian Journal of Medicine and Health Sciences 2024, 20, 168–174. [Google Scholar]

- Yamsrual, S.; Sasaki, N.; Tsusaka, T. W.; Winijkul, E. Assessment of local perception on eco-industrial estate performances after 17 years of implementation in Thailand. Environmental Development 2019, 32, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillapapiromsuk, S.; Koontoop, G.; Bootdee, S. Health Risk Assessment of Ambient Nitrogen Dioxide Concentrations in Urban and Industrial Area in Rayong Province, Thailand. TRENDS IN SCIENCES 2022, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muenmee, S.; Bootdee, S. Health risk assessment of exposure PM2.5 from industrial area in Pluak Daeng district, Rayong province. Naresuan Phayao J 2021, 14, 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Thongsaeng, P.; Karuchit, S.; Pongkiatkul, P. Concentration and chemical composition of PM2.5 in Nakhon Ratchasima city. Engineering Journal of Research and Development 2018, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Phantu, S.; Kaenbubpha, K.; Ployprom, N.; Bootdee, S. Health Risk Assessment of PM2.5 exposure in Dry season from Map Ta Phut Town Municility in Rayong Province. Journal of Science and Technology Nakhon Sawan Rajabhat University 2022, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Asa, P.; Jinsart, W. Effects of Air Pollution Related Respiratory Symptoms in Schoolchildren in Industrial Areas Rayong, Thailand. EnvironmentAsia 2016, 9, 116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Department, P. C. The state of air and noise pollution in Thailand. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Department, P. C. Thailand state of pollution report 2023. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Thailand, N. S. o. Summary of the performance of the elderly in Thailand 2023. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jawjit, S.; Pibul, P.; Muenrach, N.; Kuakul, A. Risk Assessment of PM10 Exposure of Stone Crushing Plant Nearby and Further Communities in Nakhon Si Thammarat. Journal of Science and Technology 2018, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Tantipanjaporn, T.; Srisakultiew, N.; Sukhantho, B. Health Risk Assessment of Inhalation Exposure to Respirable Dust among Workers in a Rice Mill in Kamphaeng Phet Province. Srinagarind Med J 2019, 34, 482–489. [Google Scholar]

- Qing, C.; Hehua, Z.; Yuhong, Z. Ambient air pollution and daily hospital admissions for respiratory system–related diseases in a heavy polluted city in Northeast China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2020, 27, 10055–10064. [Google Scholar]

- Eun, K. L.; Xiaobo, X. R.; Wangjian, Z.; Beth, J. F.; Haider, A. K.; Xuesong, Z.; Shao, L. Residential Proximity to Biorefinery Sources of Air Pollution and Respiratory Diseases in New York State. Environmental Science and Technology 2021, 55, 10035–10045. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, A.; Wilkinson, T. M. A. Respiratory viral infections in the elderly. Therapeutic Advances in Respiratory Disease 2021, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Muraki, I.; Liu, K.; Shirai, K.; Tamakoshi, A.; Hu, Y.; Iso, H. Diabetes and Mortality From Respiratory Diseases: The Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. Journal of Epidemiology 2020, 30, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, C.; Ducatman, A. M.; Conway, B. N. Increased risk of respiratory diseases in adults withType 1 and Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2018, 142, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, J.; Park, C.-H.; Lee, Y.-T.; Yoon, K. J. Association between underweight and pulmonary function in 282,135 healthy adults: A cross-sectional study in Korean population. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farihah Mohmad Shamsuddin, A.; Jalaludin, J.; Haslina Hashim, N. Exposure to industrial air pollution and its association with respiratory symptoms among children in Parit Raja, Batu Pahat. Earth and Environmental Science 2022, 1013, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Chen, F.; Wang, K.; Ma, X.; Wei, X.; Wang, W.; Huang, P.; Yang, D.; Xia, Z.; Zhao, Z. Acute respiratory response to individual particle exposure (PM(1.0), PM(2.5) and PM(10)) in the elderly with and without chronic respiratory diseases. Environmental pollution (Barking, Essex : 1987) 2021, 271, 116329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Fang, H. The effect of health education on knowledge and behavior toward respiratory infectious diseases among students in Gansu, China: a quasi-natural experiment. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PM2.5 | NO2 | |||||||

| Distance | Min | Median | Mean (SD) | Max | Min | Median | Mean (SD) | Max |

| Near (0-3 km) | ||||||||

| Ap | 23.1 | 34.3 | 32.5 (6.8) | 41.4 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.005 (0.0002) | 0.005 |

| Bs | 17.5 | 41.6 | 38.8 (10.1) | 49.4 | 0.012 | 0.013 | 0.013 (0.0003) | 0.013 |

| Far (>3-5 km) | ||||||||

| Cb | 29.9 | 34.6 | 38.3 (7.6) | 50.9 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 (0.0005) | 0.005 |

| Dph | 32.6 | 41.3 | 44.6 (10.7) | 58.5 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 (0.0004) | 0.003 |

| Factors | Entire region (n = 2,799) | Subregion (n = 1,347) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage (%) | Number | Percentage (%) | ||

| LRTI | |||||

| No | 2,733 | 97.64 | 1,305 | 96.88 | |

| Yes | 66 | 2.36 | 42 | 3.12 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 1,522 | 54.38 | 745 | 55.31 | |

| Male | 1,277 | 45.62 | 602 | 44.69 | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 60-69 | 1,656 | 59.16 | 776 | 57.61 | |

| 70-79 | 721 | 25.76 | 344 | 25.54 | |

| ≥ 80 | 422 | 15.08 | 227 | 16.85 | |

| Mean (±SD) | 69.48 (± 8.36) | 69.71 (± 8.43) | |||

| Median (Min:Max) | 67 (60: 113) | 68 (60:97) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||

| Normal weight (18.50-22.99 kg/m2) | 1187 | 68.66 | 660 | 49.00 | |

| Underweight (<18.50 kg/m2) | 152 | 10.66 | 124 | 9.20 | |

| Overweight (≥ 23.00 kg/m2) | 460 | 20.66 | 563 | 41.80 | |

| Mean (±SD) | 22.84 (±2.84) | 22.73 (±3.61) | |||

| Median (Min:Max) | 23.11 (10.59:41.87) | 22.35 (10.59:41.87) | |||

| Chronic disease | |||||

| N/A | 1,428 | 51.02 | 0 | 0 | |

| Any chronic disease | 1,043 | 37.26 | 1,043 | 77.43 | |

| Hypertension | 104 | 3.72 | 94 | 6.98 | |

| Diabetes | 89 | 3.18 | 82 | 6.09 | |

| Education level | |||||

| N/A | 1,428 | 51.02 | 0 | 0 | |

| Primary school | 1,305 | 46.62 | 1,284 | 95.32 | |

| Higher than Primary school | 66 | 2.07 | 63 | 4.68 | |

| Occupation | |||||

| N/A | 1,428 | 51.02 | 0 | 0 | |

| None | 1,287 | 46.38 | 1,287 | 95.55 | |

| Farmer | 36 | 1.29 | 36 | 2.67 | |

| Laborer | 26 | 0.93 | 12 | 0.89 | |

| Other | 4 | 0.14 | 10 | 0.74 | |

| Smoking cigarettes | |||||

| N/A | 1,428 | 51.02 | 0 | 0 | |

| No | 1,235 | 44.12 | 1,211 | 89.90 | |

| Yes (current or previous) | 136 | 4.86 | 136 | 10.10 | |

| Drinking alcohol | |||||

| N/A | 1,428 | 51.02 | 0 | 0 | |

| No | 1,235 | 44.12 | 1,066 | 79.14 | |

| Yes (current or previous) | 136 | 4.86 | 281 | 20.86 | |

| PM2.5 average concentration (µg/m3 ) | |||||

| Low (<37.5 µg/m3) | 698 | 24.95 | 0 | 0 | |

| High (≥ 37.5 µg/m3) | 2,101 | 75.05 | 1,347 | 100 | |

| NO2 average concentration (ppm) | |||||

| Low (< 0.17 ppm) | 2,799 | 100 | 1,347 | 100 | |

| High (≥ 0.17 ppm) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Wind direction | |||||

| Upwind | 687 | 24.54 | 285 | 21.16 | |

| Downwind | 2,112 | 75.46 | 1,062 | 78.84 | |

| Distance from home to the new estate | |||||

| Far (>3-5 km) | 1,488 | 53.16 | 760 | 56.42 | |

| Near (0-3 km) | 1,311 | 46.84 | 587 | 43.58 | |

| Factors | Number | LRTI | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | (%) | OR | 95% CI | p-value | ORadj | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Overall | 1,347 | 42 | 3.12 | ||||||

| Distance | 0.017 | 0.001 | |||||||

| Far (> 3-5 km) | 760 | 16 | 2.11 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Near (0-3 km) | 587 | 26 | 4.43 | 2.15 | 1.15-4.06 | 3.43 | 1.61- 7.36 | ||

| Gender | 0.100 | 0.173 | |||||||

| Female | 745 | 18 | 2.42 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Male | 602 | 24 | 3.99 | 1.67 | 0.90- 3.12 | 1.80 | 0.89-3.67 | ||

| Age (Years) | 0.296 | 0.021 | |||||||

| 60-69 | 776 | 21 | 2.71 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 70-79 | 344 | 10 | 2.91 | 1.08 | 0.50-2.31 | 0.850 | 1.33 | 0.57- 3.07 | |

| ≥80 | 227 | 11 | 4.85 | 1.83 | 0.87- 3.86 | 0.112 | 2.50 | 1.02- 6.10 | |

| BMI | 0.001 | 0.280 | |||||||

| Normal weight | 660 | 12 | 1.82 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Underweight | 124 | 11 | 8.87 | 5.25 | 2.26-12.20 | <0.001 | 5.39 | 2.00- 14.50 | |

| Overweight | 563 | 19 | 3.37 | 1.88 | 0.90-3.92 | 0.089 | 1.89 | 0.85- 4.15 | |

| Education | 0.055 | 0.001 | |||||||

| Primary | 1,284 | 95.32 | 2.88 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Higher than primary | 63 | 4.68 | 7.94 | 2.90 | 1.10-7.66 | 3.06 | 0 .95-9.91 | ||

| Smoking cigarettes | 0.899 | 0.648 | |||||||

| No | 1,211 | 89.90 | 3.14 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes (current or former) | 136 | 10.10 | 2.94 | 0.94 | 0 .33-2.66 | 1.41 | 0.40-5.01 | ||

| Diabetes | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| No | 1,265 | 93.91 | 1.74 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 82 | 6.09 | 24.39 | 18.22 | 9.45-5.16 | 33.89 | 15.01-76.05 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).