Submitted:

11 March 2025

Posted:

11 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background: Exposure to household air pollution (HAP) is one of the primary risk factors for acute lower respiratory infection (ARI) morbidity and mortality among children in low-income settings. This study aimed to examine the relative contribution of residing in deprived neighbourhoods and exposure to HAP on the occurrence of ARI among children using data from the 2014-15 Chad Demographic and Health Survey (DHS). Methods: We applied multilevel modelling techniques to survey data of 2,882 children from 372 communities to compute the odds ratio (OR) for the occurrence of ARI between children of respondents exposed to clean fuels (e.g., electricity, liquid petroleum gas, natural gas, and biogas) and respondents exposed to polluting fuel (e.g., kerosene, coal/lignite, charcoal, wood, straw/shrubs/grass, and animal dung). Results: The results showed that children exposed to household polluting fuels in Chad were 215% more likely to develop ARI than those not exposed to household air pollution (215%; OR = 3.15; 95% CI 2.41to 4.13); Further analysis revealed that the odds of ARI were 185% higher (OR = 2.85; 95% CI 1.73 to 4.75) among children living in rural residents and those born to teenage mothers (OR = 2.75; 95% CI 1.48 to 5.15) who were exposed to household polluting fuels compared to their counterparts who were not exposed. In summary, the results of the study show that the risk of ARI is more common among children who live in homes where household air-polluting cooking fuel is widely used, those living in rural areas, those living in socioeconomically deprived neighbourhoods and from least wealthy households, and those born to teenage mothers in Chad. Conclusions: In this study, an independent relative contribution of variables such as HAP from cooking fuel, neighbourhood deprivation, living in rural areas, being from a low-income household, having a mother who is a manual labourer worker, being given birth to by a teenage mother to the risk of ARI among children is established.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sampling Technique

2.2. Outcome Variable

2.3. Exposure Variable

2.4. Control Variables

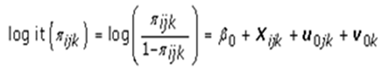

2.5. Statistical Analysis/Analytical Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

| ARI | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Yes | No | |

| N (%) | N (%) | Total N (%) | |

| Child’s age (months) | |||

| 0–10 | 284 (24.8) | 154 (19.6) | 438 (22.7) |

| 11–21 | 205 (17.9) | 176 (22.4) | 381 (19.7) |

| 22–32 | 203(17.7) | 167 (21.3) | 370 (19.2) |

| 33+ | 454 (39.6) | 288(36.7) | 742(38.4) |

| Child’s sex | |||

| Male | 866(50.8) | 597 (50.7) | 1,463 (50.8) |

| Female | 838 (49.2) | 581(49.3) | 1,419 (49.2) |

| Mother’s age (years) | |||

| 15–24 | 503 (29.5) | 384 (32.6) | 887(30.8) |

| 25–34 | 843 (49.5) | 562(47.7) | 1,704 (48.8) |

| 35+ | 358(21.0) | 232 (19.7) | 590 (20.4) |

| Mother’s education | |||

| No education | 8(0.5) | 9(0.8) | 17(0.6) |

| Primary | 1,119(65.6) | 751(63.7) | 1,870 (64.9) |

| Secondary and higher | 577(33.9) | 418 (35.5) | 995(34.5) |

| Place of delivery | |||

| Home | 1,320(77.8) | 871 (74.1) | 2,191(76.3) |

| Hospital | 377 (22.2) | 305 (25.9) | 682 (23.7) |

| Media access(radio,tele&magazine) | |||

| None | 1,232 (72.3) | 793(67.3) | 2,024 (70.2) |

| 1 | 258 (15.1) | 189(16.0) | 447(15.5) |

| 2 | 50(2.9) | 50(4.2) | 100 (3.5) |

| 3 | 164(9.6) | 147(12.5) | 311(10.8) |

| Mother’s occupation | |||

| Not working | 92 (5.5) | 77(6.7) | 169 (6.0) |

| Manual | 1,272(76.3) | 854(74.6) | 2,126(75.6) |

| Professional | 304(18.2) | 214(18.7) | 517(18.4) |

| Wealth index | |||

| Poorest | 373(21.9) | 225(19.1) | 598 (20.7) |

| Poorer | 329(19.3) | 226(19.2) | 555(19.3) |

| Middle | 375 22.0) | 239(20.2) | 614(21.3) |

| Richer | 322(18.9) | 215(18.3) | 537(18.6) |

| Richest | 305(17.9) | 273(23.2) | 578(20.1) |

| Types of cooking fuel | |||

| Polluting | 1,670(98.0) | 1,136(96.4) | 2,806(97.4) |

| Clean | 34(2.0) | 42(3.6) | 76(2.6) |

| Parity | |||

| 1-3 | 645(37.9) | 475(40.3) | 1,120(38.9) |

| 4+ | 1,059(62.1) | 703(59.7) | 1,762(61.1) |

|

Maternal breast-feeding status Never breastfed Ever breastfed Still breastfeeding |

75(4.4) 896(52.3) 742(43.3) |

53(4.5) 640(54.8) 476(40.7) |

128(4.4) 1,536(53.3) 1,218(42.3) |

|

Place of residence Rural Urban |

1,293(75.9) 411(24.1) |

853(72.4) 325(27.6) |

2,146(74.5) 736(25.5) |

|

Neighbourhoods’ economic disadvantage Least disadvantaged Most disadvantage |

770(45.2) 934(54.8) |

572(48.6) 606(51.4) |

1,342(46.6) 1,540(53.4) |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| (Individual Characteristics) | |||

| Mother’s age(years) 35+ 25-34 15-24 |

1(reference) 6.93[10.52-12.40] *** 2.75 [1.48-5.15] *** |

1(reference) 5.10[3.88- 12.42] ** 2.78[3.85- 5.20] ** |

|

|

Parity 1-3 4+ |

1(reference) 0.10 [0.17-0.66] * |

1(reference) 0.10[0.02-0.65] * |

|

| Highest level of education No education Primary Secondary and above |

1(reference) 3.02 [0.73-4.60] 0.67 [0.54-0.82] *** |

1(reference) 3.35[0.72-5.62] 0.66[0.72-5.62] *** |

|

|

Media Access None 1 2 3 |

1(reference) 0.66 [0.17-2.60] 0.91 [1.01-1.51] ** 0.18 [0.10-0.54] ** |

1(reference) 0.67 [0.17-2.60] 0.66 [0.17-2.60] ** 0.16[0.17-0.60] ** |

|

|

Household wealth index Poorest Poorer Middle Richer Richest |

1(reference) 0.78 [0.42-1.43] 0.69 [0.36-1.34] 0.42 [0.19-0.88]** 0.34 [0.14-0.83]** |

1(reference) 0.76 [0.41-1.40] 0.54 [0.52-1.11] 0.40[0.17-0.90]** 0.34 [0.14-0.89]** |

|

|

Occupation Not working Manual Professional |

1(reference) 1.14 [0.44-2.79] 0.80 [0.65-0.90]* |

1(reference) 0.80 [0.44-2.79] 0.79 [0.63-0.91]* |

|

|

Sex of child Male Female |

1(reference) 0.56 [0.36-0.89] ** |

1(reference) 0.54 [0.40-0.89] ** |

|

|

Child age in months 0 -10 11-21 22-32 33+ |

1(reference) 0.56 [0.39-0.79] *** 0.59 [0.42-0.85] ** 0.75 [0.56-1.20] |

1(reference) 0.54 [0.39-0.80] *** 0.57 [0.49-0.80] ** 0.80 [0.57-1.31] |

|

|

Types of cooking fuel Clean fuel Polluting fuel |

1(reference) 3.15 [2.41-4.13] *** |

1(reference) 3.10 [2.39- 4.10] *** |

|

|

Breastfeeding status Not currently breastfeeding Never breastfed Still breastfeeding |

1(reference) 3.50 [0.52-8.56] 0.48 [0.07-3.08] |

1(reference) 2.96[0.46-10.00] 0.68[0.46-1.00] |

|

|

Place of birth Delivery Home Hospital |

1(reference) 0.90 [0.69-1.16] |

1(reference) 0.89 [0.65-1.10] |

|

|

Community level variables Place of residence Urban Rural |

1 2.85 [1.73-4.75] *** |

||

|

Neighbourhood Economic disadvantaged index Most disadvantaged Least disadvantaged |

1 0.56 [0.44-0.70] *** |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Intercept | 0.15[0.16-0.20] *** | 1.14[0.03] *** | 1.12 [0.03] *** |

| Community-level variance (SE) | 1.30[0.04] *** | 1.14[0.03] *** | 1.12 [0.03] *** |

| VPC (%) | 25 | 23.5 | 20.0 |

|

Explained variation PCV (%) Model fit statistics |

Reference | 12.3 | 17.5 |

| DIC(-2log likelihood) | 3651.40 | 3012.20 | 2601.10 |

3.4. Results

4. Discussion

Policy Implications

Study Strengths & Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Black, R.E.; Morris, S.S.; Bryce, J. Where and why are 10 million children dying every year? Lancet 2003, 361, 2226-2234. [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Levels & Trends in Child Mortality. 2014.

- Nair, H.; Nokes, D.J.; Gessner, B.D.; Dherani, M.; Madhi, S.A.; Singleton, R.J.; O’Brien, K.L.; Roca, A.; Wright, P.F.; Bruce, N.; et al. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010, 375, 1545-1555. [CrossRef]

- Staton, D.M.; Harding, M.H. Protecting Child Health Worldwide. Implementation is the biggest challenge slowing efforts to reduce childhood morbidity and mortality in developing countries. Pediatr Ann 2004, 33, 647-655.

- Khan, M.N.; CZ, B.N.; Mofizul Islam, M.; Islam, M.R.; Rahman, M.M. Household air pollution from cooking and risk of adverse health and birth outcomes in Bangladesh: a nationwide population-based study. Environ Health 2017, 16, 57. [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.; Steketee, R.W.; Black, R.E.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Morris, S.S.; Bellagio Child Survival Study, G. How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet 2003, 362, 65-71. [CrossRef]

- Wichmann, J.; Voyi, K.V. Influence of cooking and heating fuel use on 1-59 month old mortality in South Africa. Matern Child Health J 2006, 10, 553-561. [CrossRef]

- Rinne, S.T.; Rodas, E.J.; Rinne, M.L.; Simpson, J.M.; Glickman, L.T. Use of biomass fuel is associated with infant mortality and child health in trend analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007, 76, 585-591.

- WHO. Indoor air pollution national burden of disease estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2007.

- Smith, K.R.; Samet, J.M.; Romieu, I.; Bruce, N. Indoor air pollution in developing countries and acute lower respiratory infections in children. Thorax 2000, 55, 518-532.

- Norman, R.; Cairncross, E.; Witi, J.; Bradshaw, D.; South African Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating, G. Estimating the burden of disease attributable to urban outdoor air pollution in South Africa in 2000. S Afr Med J 2007, 97, 782-790.

- Arifeen, S.; Black, R.E.; Antelman, G.; Baqui, A.; Caulfield, L.; Becker, S. Exclusive breastfeeding reduces acute respiratory infection and diarrhea deaths among infants in Dhaka slums. Pediatrics 2001, 108, E67.

- WHO. WHO. Pronczuk-Garbino, M.; Children’s health and the environment. A global perspective. 2005.; WHO: Switzerland, 2005.

- Bates, M.N.; Chandyo, R.K.; Valentiner-Branth, P.; Pokhrel, A.K.; Mathisen, M.; Basnet, S.; Shrestha, P.S.; Strand, T.A.; Smith, K.R. Acute lower respiratory infection in childhood and household fuel use in Bhaktapur, Nepal. Environ Health Perspect 2013, 121, 637-642. [CrossRef]

- Bonjour, S.; Adair-Rohani, H.; Wolf, J.; Bruce, N.G.; Mehta, S.; Pruss-Ustun, A.; Lahiff, M.; Rehfuess, E.A.; Mishra, V.; Smith, K.R. Solid fuel use for household cooking: country and regional estimates for 1980-2010. Environ Health Perspect 2013, 121, 784-790. [CrossRef]

- Kapsalyamova, Z.; Mishra, R.; Kerimray, A.; Karymshakov, K.; Azhgaliyeva, D. Why energy access is not enough for choosing clean cooking fuels? Evidence from the multinomial logit model. J Environ Manage 2021, 290, 112539. [CrossRef]

- Chafe, Z.A.; Brauer, M.; Klimont, Z.; Van Dingenen, R.; Mehta, S.; Rao, S.; Riahi, K.; Dentener, F.; Smith, K.R. Household cooking with solid fuels contributes to ambient PM2.5 air pollution and the burden of disease. Environ Health Perspect 2014, 122, 1314-1320. [CrossRef]

- Adaji, E.E.; Ekezie, W.; Clifford, M.; Phalkey, R. Understanding the effect of indoor air pollution on pneumonia in children under 5 in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of evidence. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2018. [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, K.; Chinnakali, P.; Majumdar, A.; Krishnan, I.S. Acute respiratory infections among under-5 children in India: A situational analysis. J Nat Sci Biol Med 2014, 5, 15-20. [CrossRef]

- Aithal, S.S.; Sachdeva, I.; Kurmi, O.P. Air quality and respiratory health in children. Breathe (Sheff) 2023, 19, 230040. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.J.; Brauer, M.; Burnett, R.; Anderson, H.R.; Frostad, J.; Estep, K.; Balakrishnan, K.; Brunekreef, B.; Dandona, L.; Dandona, R.; et al. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet 2017, 389, 1907-1918. [CrossRef]

- Kodgule, R.; Salvi, S. Exposure to biomass smoke as a cause for airway disease in women and children. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2012, 12, 82-90. [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Air Quality Policies in Chad; The United Nations Environment Programme(UNEP): 2021.

- Ezzati, M.; Kammen, D. Indoor air pollution from biomass combustion and acute respiratory infections in Kenya: an exposure-response study. Lancet 2001, 358, 619-624.

- ICF Macro and Institut National de la Statistique, d.É.É.e.D.I.N.D., Chad. Tchad Demographic and Health Survey (2015). Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-FR317-DHS-Final-Reports.cfm (accessed on 13 February 2018).

- Vyas, S.; Kumaranayake, L. Constructing socio-economic status indices: how to use principal components analysis. Health Policy Plan 2006, 21, 459-468. [CrossRef]

- Wight, R.G.; Cummings, J.R.; Miller-Martinez, D.; Karlamangla, A.S.; Seeman, T.E.; Aneshensel, C.S. A multilevel analysis of urban neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and health in late life. Soc Sci Med 2008, 66, 862-872. [CrossRef]

- Beard, J.R.; Cerda, M.; Blaney, S.; Ahern, J.; Vlahov, D.; Galea, S. Neighborhood characteristics and change in depressive symptoms among older residents of New York City. Am J Public Health 2009, 99, 1308-1314. [CrossRef]

- Aremu, O.; Lawoko, S.; Dalal, K. Childhood vitamin A capsule supplementation coverage in Nigeria: a multilevel analysis of geographic and socioeconomic inequities. ScientificWorldJournal 2010, 10, 1901-1914. [CrossRef]

- Merlo, J.; Chaix, B.; Ohlsson, H.; Beckman, A.; Johnell, K.; Hjerpe, P.; Rastam, L.; Larsen, K. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006, 60, 290-297. [CrossRef]

- Pickett, K.E.; Pearl, M. Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2001, 55, 111-122.

- Kabir, E.; Kim, K.H.; Sohn, J.R.; Kweon, B.Y.; Shin, J.H. Indoor air quality assessment in child care and medical facilities in Korea. Environ Monit Assess 2012, 184, 6395-6409. [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Wheeler, D.; Huq, M.; Khaliquzzaman, M. Improving indoor air quality for poor families: a controlled experiment in Bangladesh. Indoor Air 2009, 19, 22-32. [CrossRef]

- Gurley, E.S.; Homaira, N.; Salje, H.; Ram, P.K.; Haque, R.; Petri, W.; Bresee, J.; Moss, W.J.; Breysse, P.; Luby, S.P.; et al. Indoor exposure to particulate matter and the incidence of acute lower respiratory infections among children: a birth cohort study in urban Bangladesh. Indoor Air 2013, 23, 379-386. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V. Indoor air pollution from biomass combustion and acute respiratory illness in preschool age children in Zimbabwe. Int J Epidemiol 2003, 32, 847-853. [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, M.U.G.; Faria, N.R.; Reiner, R.C., Jr.; Golding, N.; Nikolay, B.; Stasse, S.; Johansson, M.A.; Salje, H.; Faye, O.; Wint, G.R.W.; et al. Spread of yellow fever virus outbreak in Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo 2015-16: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017, 17, 330-338. [CrossRef]

- Kilabuko, J.H.; Nakai, S. Effects of cooking fuels on acute respiratory infections in children in Tanzania. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2007, 4, 283-288.

- Kaplan, C. Indoor air pollution from unprocessed solid fuels in developing countries. Rev Environ Health 2010, 25, 221-242. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, F.C.; Smith, K.R.; Vichit-Vadakan, N.; Ostro, B.D.; Chestnut, L.G.; Kungskulniti, N. Indoor/outdoor PM10 and PM2.5 in Bangkok, Thailand. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol 2000, 10, 15-26. [CrossRef]

- Khalequzzaman, M.; Kamijima, M.; Sakai, K.; Ebara, T.; Hoque, B.A.; Nakajima, T. Indoor air pollution and health of children in biomass fuel-using households of Bangladesh: comparison between urban and rural areas. Environ Health Prev Med 2011, 16, 375-383. [CrossRef]

- Rumchev, K.; Spickett, J.T.; Brown, H.L.; Mkhweli, B. Indoor air pollution from biomass combustion and respiratory symptoms of women and children in a Zimbabwean village. Indoor Air 2007, 17, 468-474. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Padilla, R.; Schilmann, A.; Riojas-Rodriguez, H. Respiratory health effects of indoor air pollution. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2010, 14, 1079-1086.

- Dahal, G.P.; Johnson, F.A.; Padmadas, S.S. Maternal smoking and acute respiratory infection symptoms among young children in Nepal: multilevel analysis. J Biosoc Sci 2009, 41, 747-761. [CrossRef]

- Romieu, I.; Gouveia, N.; Cifuentes, L.A.; de Leon, A.P.; Junger, W.; Vera, J.; Strappa, V.; Hurtado-Diaz, M.; Miranda-Soberanis, V.; Rojas-Bracho, L.; et al. Multicity study of air pollution and mortality in Latin America (the ESCALA study). Res Rep Health Eff Inst 2012, 5-86.

- Ladomenou, F.; Moschandreas, J.; Kafatos, A.; Tselentis, Y.; Galanakis, E. Protective effect of exclusive breastfeeding against infections during infancy: a prospective study. Arch Dis Child 2010, 95, 1004-1008. [CrossRef]

- Oviawe, O.; Oviawe, N. Acute respiratory infection in an infant. Niger J Paediatr 1993, 20, 21-23.

- Ezeh, O.K.; Agho, K.E.; Dibley, M.J.; Hall, J.J.; Page, A.N. The effect of solid fuel use on childhood mortality in Nigeria: evidence from the 2013 cross-sectional household survey. Environ Health 2014, 13, 113. [CrossRef]

- Kandala, N.B.; Ji, C.; Stallard, N.; Stranges, S.; Cappuccio, F.P. Morbidity from diarrhoea, cough and fever among young children in Nigeria. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2008, 102, 427-445. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Sethi, G.R.; Rohtagi, A.; Chaudhary, A.; Shankar, R.; Bapna, J.S.; Joshi, V.; Sapir, D.G. Indoor air quality and acute lower respiratory infection in Indian urban slums. Environ Health Perspect 1998, 106, 291-297. [CrossRef]

- Sanbata, H.; Asfaw, A.; Kumie, A. Association of biomass fuel use with acute respiratory infections among under- five children in a slum urban of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1122. [CrossRef]

- Cobanoglu, N.; Kiper, N.; Dilber, E.; Gurcan, N.; Gocmen, A.; Ozcelik, U.; Dogru, D.; Yalcin, E.; Pekcan, S.; Kose, M. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and respiratory morbidity in children. Inhal Toxicol 2007, 19, 779-785. [CrossRef]

- Halder, A.K.; Luby, S.P.; Akhter, S.; Ghosh, P.K.; Johnston, R.B.; Unicomb, L. Incidences and Costs of Illness for Diarrhea and Acute Respiratory Infections for Children < 5 Years of Age in Rural Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017, 96, 953-960. [CrossRef]

- Jary, H.; Simpson, H.; Havens, D.; Manda, G.; Pope, D.; Bruce, N.; Mortimer, K. Household Air Pollution and Acute Lower Respiratory Infections in Adults: A Systematic Review. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0167656. [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.; Uddin, J.; Peltier, R.; Oulhote, Y. Associations between Indoor Air Pollution and Acute Respiratory Infections among Under-Five Children in Afghanistan: Do SES and Sex Matter? Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Duque, C.; Maldonado, D.; Perez-Padilla, R.; Ezzati, M.; Viegi, G.; Forum of International Respiratory Studies Task Force on Health Effects of Biomass, E. Biomass fuels and respiratory diseases: a review of the evidence. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008, 5, 577-590. [CrossRef]

- Murray, E.L.; Brondi, L.; Kleinbaum, D.; McGowan, J.E.; Van Mels, C.; Brooks, W.A.; Goswami, D.; Ryan, P.B.; Klein, M.; Bridges, C.B. Cooking fuel type, household ventilation, and the risk of acute lower respiratory illness in urban Bangladeshi children: a longitudinal study. Indoor Air 2012, 22, 132-139. [CrossRef]

- Perl, R.; Murukutla, N.; Occleston, J.; Bayly, M.; Lien, M.; Wakefield, M.; Mullin, S. Responses to antismoking radio and television advertisements among adult smokers and non-smokers across Africa: message-testing results from Senegal, Nigeria and Kenya. Tob Control 2015, 24, 601-608. [CrossRef]

- Egbe, C.O.; Petersen, I.; Meyer-Weitz, A.; Oppong Asante, K. An exploratory study of the socio-cultural risk influences for cigarette smoking among Southern Nigerian youth. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1204. [CrossRef]

- Ujunwa, F.; Ezeonu, C. Risk Factors for Acute Respiratory Tract Infections in Under-five Children in Enugu Southeast Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2014, 4, 95-99. [CrossRef]

- Bruce, N.G.; Dherani, M.K.; Das, J.K.; Balakrishnan, K.; Adair-Rohani, H.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Pope, D. Control of household air pollution for child survival: estimates for intervention impacts. BMC Public Health 2013, 13 Suppl 3, S8. [CrossRef]

- Bruce, N.; Perez-Padilla, R.; Albalak, R. Indoor air pollution in developing countries: a major environmental and public health challenge. Bull World Health Organ 2000, 78, 1078-1092.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).