Submitted:

27 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Context for Sustainability Competencies Questionnaire Development

2.1. Research on Competencies for Sustainability

2.2. GreenComp as an Inspiration for Sustainability Competencies Assessment

2.2.1. Why Use GreenComp to Assess Sustainability Competencies?

2.2.2. Reading GreenComp and Understanding Its Purpose

2.2.3. Merging Games’ Features and GreenComp: The Potentialities of Mobile Augmented Reality Games and the Assessment of Competencies for Sustainability Based on the Framework

3. Instrument Development Methodology

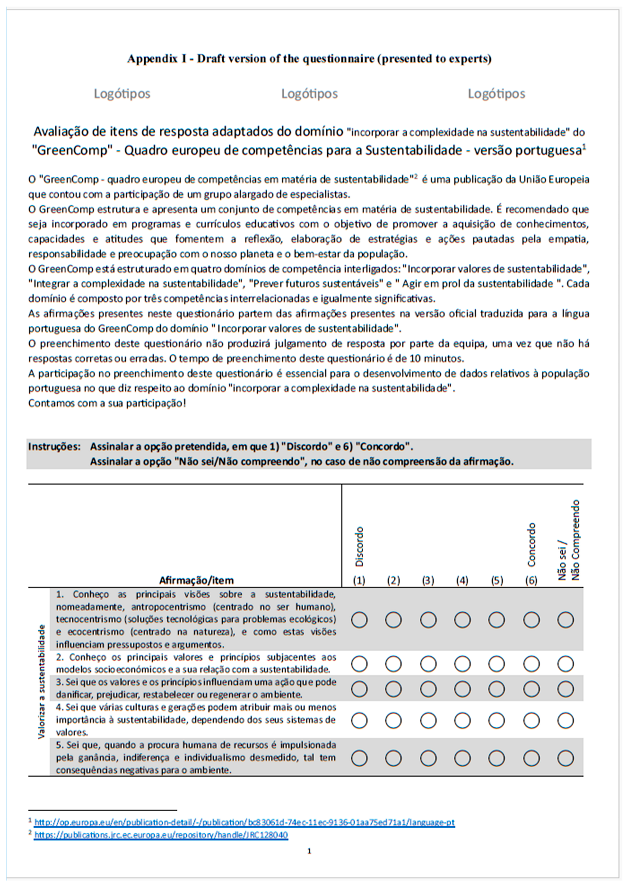

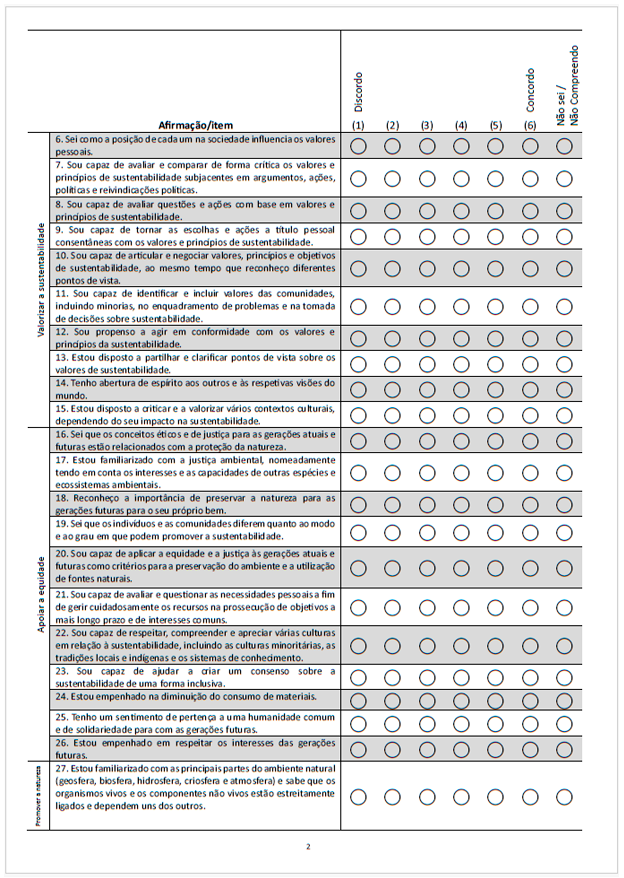

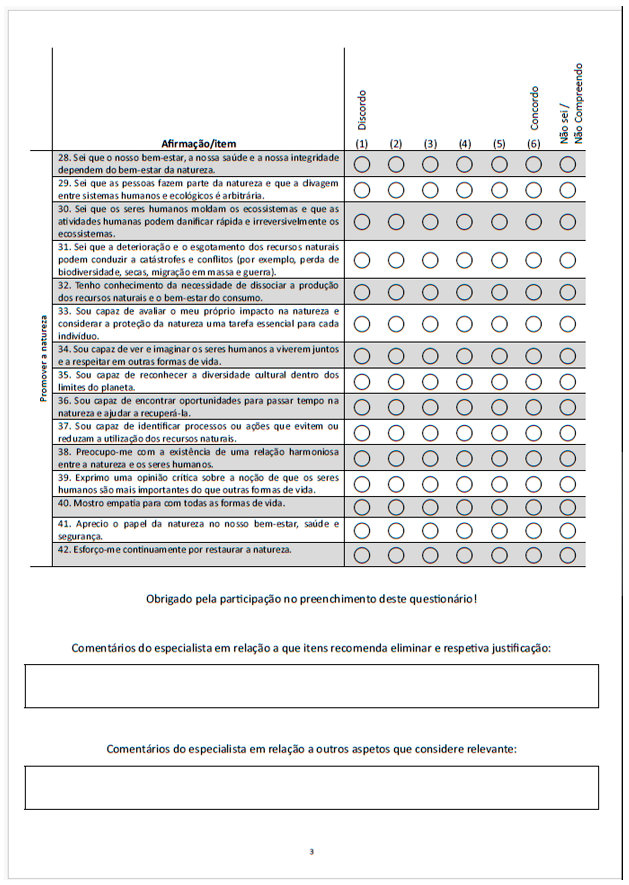

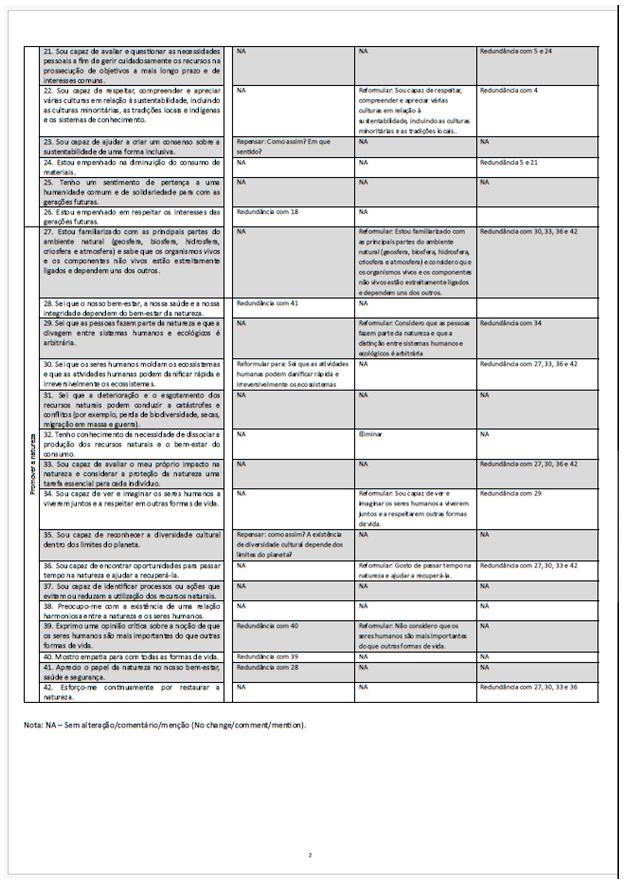

3.1. Adopting or Adapting the GreenComp Framework area “Embodying Sustainability Values”?

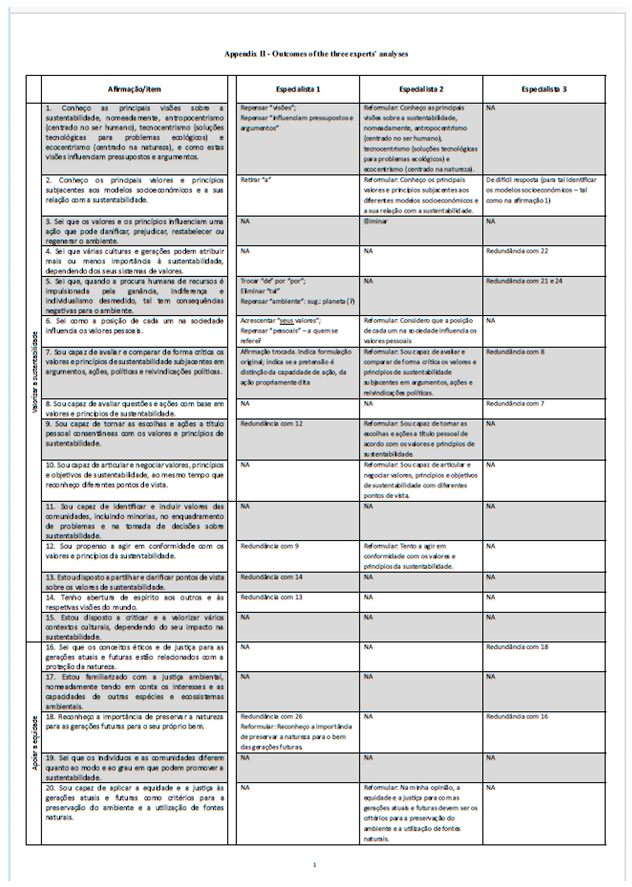

3.1.1. Cutting Items Process

3.1.1.1. Expert’s Analysis

3.1.1.2. Pilot-Testing

3.1.2. The Pilot-Tests Results’ Analysis: The Alphas and Omegas of the Questionnaire

3.2. The first Version of the Questionnaire

4. Final Considerations

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

References

- González-Márquez, I.; Toledo, V.M. Sustainability Science: A Paradigm in Crisis? Sustainability 2020, 12, 2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annelin, A.; Boström, G.O. An assessment of key sustainability competencies: a review of scales and propositions for validation. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2022, 24, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundiers, K.; et al. Key competencies in sustainability in higher education—toward an agreed-upon reference framework. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrián, G.; Junyent, M.; Mulà, I. Current practices and future pathways towards competencies in education for sustainable development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Santos, J.; Pombo, L.; Marques, M.M.; Rodrigues, R. Designing a Sustainability Competencies Questionnaire: Insights from a literature review. [unpublished Work., 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, G.; Pisiotis, U.; Cabrera, M.; Punie, Y.; Bacigalupo, M. The European sustainability competence framework. 2022.

- Ferreira-Santos, J.; Pombo, L.; Marques, M.M. Overview on the development of a data collection tool based on GreenCOMP: The middle stage of its development process. [unpublished Work., 2024. [CrossRef]

- WCED. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. 1987. [Online]. Available: http://www.un-documents.net/ocf-ov.htm.

- Redman, A.; Wiek, A. Competencies for Advancing Transformations Towards Sustainability. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, A.; Wiek, A.; Barth, M. Current practice of assessing students’ sustainability competencies: a review of tools. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, E. Advancing educational pedagogy for sustainability: Developing and implementing programs to transform behaviors. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2013, 8, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pombo, L.; Marques, M.M. EduCITY as a smart learning city environment towards education for sustainability - work in progress. In Proceedings of EdMedia + Innovate Learning; Nov. 2022. 5595–5601. [CrossRef]

- Council of the European Union. Council recommendation on key competences for lifelong learning. Off. J. Eur. Union 2018, 61, 1–13. Available online: https://cutt.ly/MKKtVUN.

- Pombo, L. Exploring the role of mobile game-based apps towards a smart learning city environment – the innovation of EduCITY. Educ. Train. 2022, 65, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strada, F.; et al. Leveraging a collaborative augmented reality serious game to promote sustainability awareness, commitment and adaptive problem-management. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2023, 172, 102984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.J.; Hsu, Y.S.; Lai, C.H.; Chen, F.H.; Yang, M.H. Applying Game-Based Experiential Learning to Comprehensive Sustainable Development-Based Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.E. Instrument Development: Getting Started. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 1996, 28, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichmann, S.; Klebel, T.; Hasani-Mavriqi, I.; Ross-Hellauer, T. Between administration and research: Understanding data management practices in an institutional context. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2021, 72, 1415–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, S.R.; Ingels, S.J.; Mohammed, A. Validity of Borrowed Questionnaire Items: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2009, 21, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commision. The European Green Deal. 2019. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Sharma, H. How short or long should be a questionnaire for any research? Researchers dilemma in deciding the appropriate questionnaire length. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2022, 16, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, J.R.; Gutiérrez-Antinopai, F. Towards a visual typology of sustainability and sustainable development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabricatore, C.; López, X. Gaming for sustainability: An overview. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Games-based Learning. 2011; 159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Boncu, Ș.; Candel, O.-S.; Popa, N.L. Gameful Green: A Systematic Review on the Use of Serious Computer Games and Gamified Mobile Apps to Foster Pro-Environmental Information, Attitudes and Behaviors. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. A Mixed Methods Model of Scale Development and Validation Analysis. Meas. Interdiscip. Res. Perspect. 2019, 17, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobern, W.; Adams, B. Establishing survey validity: A practical guide. Int. J. Assess. Tools Educ. 2020, 7, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, P. Pretesting a Questionnaire. In Wiley International Encyclopedia of Marketing; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- South, L.; Saffo, D.; Vitek, O.; Dunne, C.; Borkin, M.A. Effective Use of Likert Scales in Visualization Evaluations: A Systematic Review. Comput. Graph. Forum 2022, 41, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umanath, S.; Coane, J.H. Face Validity of Remembering and Knowing: Empirical Consensus and Disagreement Between Participants and Researchers. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 15, 1400–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidik, S.M. Validation studies. In How to do Primary Care Research; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Rattray, J.; Jones, M.C. Essential elements of questionnaire design and development. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JASP Team. JASP.” JASP, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024, [Online]. Available: https://jasp-stats.org/.

- Hayes, A.F.; Coutts, J.J. Use Omega Rather than Cronbach’s Alpha for Estimating Reliability. But…. Commun. Methods Meas. 2020, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinbarg, R.E.; Revelle, W.; Yovel, I.; Li, W. Cronbach’s α, Revelle’s β, and Mcdonald’s ωH: their relations with each other and two alternative conceptualizations of reliability. Psychometrika 2005, 70, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkbrenner, M.T. Alpha, Omega, and H Internal Consistency Reliability Estimates: Reviewing These Options and When to Use Them. Couns. Outcome Res. Eval. 2023, 14, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.B.; Yang, Y. Evaluation of Dimensionality in the Assessment of Internal Consistency Reliability: Coefficient Alpha and Omega Coefficients. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 2015, 34, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, M.S. The dilemma of combining positive and negative items in scales. Psicothema 2015, 27, 192–199. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/727/72737093010.pdf. [CrossRef]

| Analysis by framework “competencies” intervals | ||

| Question interval (Q [[]) | Cronbach’s Alpha (α) | McDonald’s Omega (ω) |

| [1-6] | 0,724 | 0,733 |

| [7-11] | 0,930 | 0,932 |

| [12-15] | 0,685 | 0,760 |

| [16-19] | 0,491 | 0,492 |

| [20-23] | 0,782 | 0,845 |

| [24-26] | 0,617 | 0,631 |

| [27-32] | 0,770 | 0,722 |

| [33-37] | 0,762 | 0,779 |

| [38-42] | 0,544 | 0,499 |

| Analysis by framework “domain” | ||

| Q [] | Cronbach’s α | McDonald’s ω |

| [1-15] | 0,900 | 0,910 |

| [16-26] | 0,798 | 0,799 |

| [27-42] | 0,873 | 0,866 |

| Global | ||

| Q [] | Cronbach’s α | McDonald’s ω |

| [1-42] | 0.942 | 0.942 |

| Analysis by framework “competencies” intervals | ||

| Question interval (Q [[]) | Cronbach’s Alpha (α) | McDonald’s Omega (ω) |

| [1-6] | 0,631 | 0,712 |

| [7-11] | 0,892 | 0,892 |

| [12-15] | 0,840 | 0,856 |

| [16-19] | 0,728 | 0,761 |

| [20-23] | 0,841 | 0,847 |

| [24-26] | 0,647 | 0,802 |

| [27-32] | 0,635 | 0,654 |

| [33-37] | 0,770 | 0,774 |

| [38-42] | 0,521 | 0,533 |

| Analysis by framework “domain” | ||

| Q [] | Cronbach’s α | McDonald’s ω |

| [1-15] | 0,899 | 0,904 |

| [16-26] | 0,890 | 0,897 |

| [27-42] | 0,862 | 0,869 |

| Global | ||

| Q [] | Cronbach’s α | McDonald’s ω |

| [1-42] | 0.961 | 0.956 |

| Interpretation | Taber | Kalkbrenner1 |

|---|---|---|

| Acceptable | ≥.70 to .84 | 0.45–0.98 |

| Strong | ≥.85 | 0.91–0.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).