Submitted:

27 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

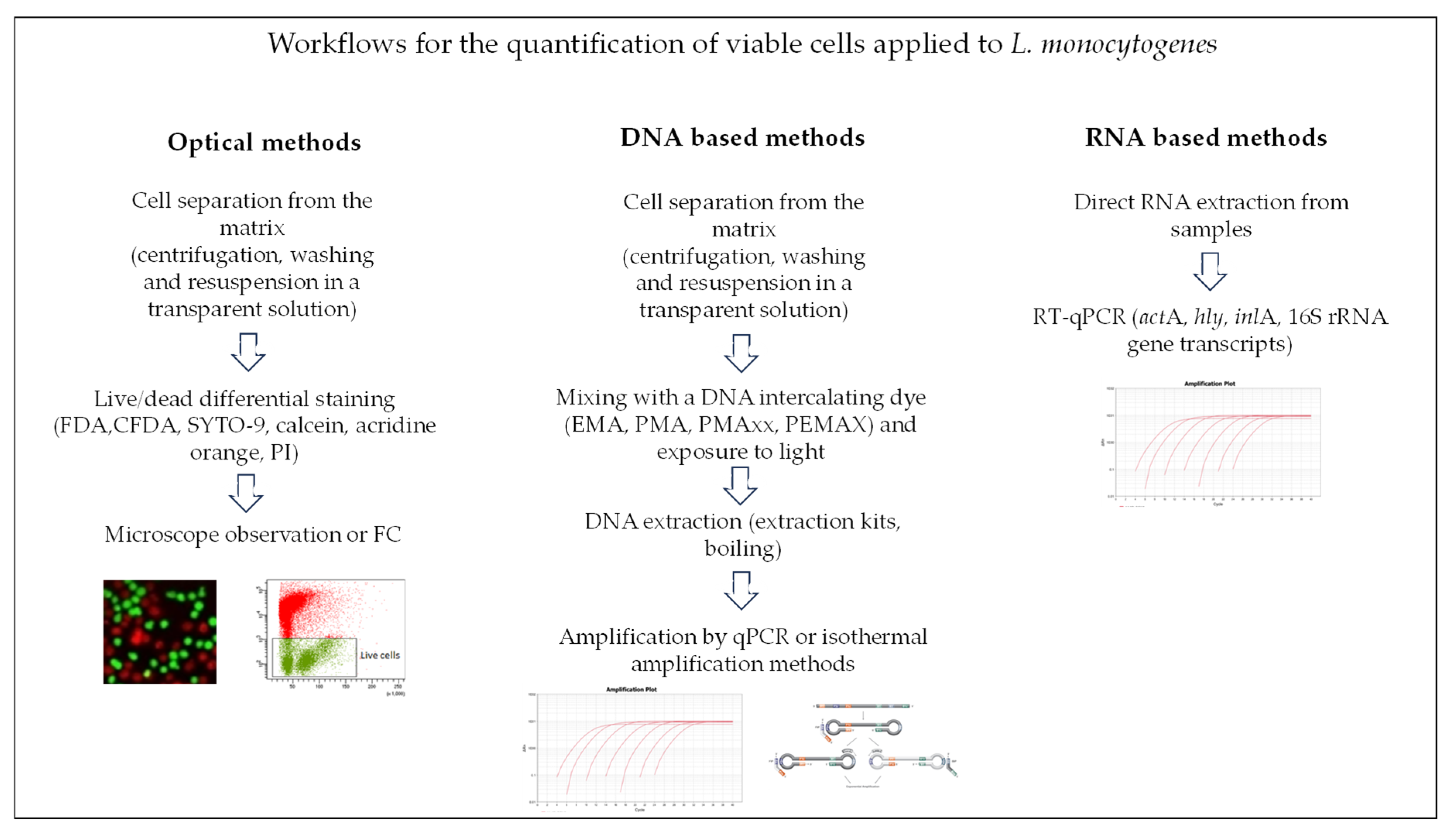

2. Detection Methods Applied to Detect VBNC L. monocytogenes

2.1. Optical Detection Methods

2.2. Molecular Detection Methods for Viable Cell Detection

3. Distribution of VBNC L. monocytogenes in Food and Food Production Plants

4. Factors Inducing the VBNC State in L. monocytogenes

4.4. Role of Disinfecting Agents in VBNC L. monocytogenes Induction

3.2. Effect of Physicochemical Stresses in Food Production on the VBNC Induction in L. monocytogenes

5. Ultrastructural, Molecular and Transcriptomic Changes in L. monocytogenes VBNC Cells

6. Conditions for VBNC L. monocytogenes Resuscitation

7. Discussion and Future Perspectives

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roberts, B. N.; Chakravarty, D.; Gardner, J. C., 3rd; Ricke, S. C.; Donaldson, J. R. Listeria Monocytogenes Response to Anaerobic Environments. Pathogens 2020, 9, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsend, A.; Strawn, L.K.; Chapman, B.J.; Dunn, L.L. A Systematic Review of Listeria Species and Listeria monocytogenes Prevalence, Persistence, and Diversity throughout the Fresh Produce Supply Chain. Foods 2021, 10, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsi, R. H.; Liao, J.; Carlin, C. R.; Wiedmann, M. Taxonomy, Ecology, and Relevance to Food Safety of the Genus Listeria with a Particular Consideration of New Listeria Species Described between 2010 and 2022. MBio 2024, 15, e0093823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Listeriosis - Annual Epidemiological Report for 2022. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/listeriosis-annual-epidemiological-report-2022. 8 Feb 2024. Accessed on 1 November 2024.

- Castaño Frías, L.; Tudela-Littleton Peralta, C.; Segura Oliva, N.; Suárez Arana, M.; Cuenca Marín, C.; Jiménez López, J.S. Case Series of Listeria monocytogenes in Pregnancy: Maternal–Foetal Complications and Clinical Management in Six Cases. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Merwe, C.; Simpson, D. J.; Qiao, N.; Otto, S. J. G.; Kovacevic, J.; Gänzle, M. G.; McMullen, L. M. Is the Persistence of Listeria Monocytogenes in Food Processing Facilities and Its Resistance to Pathogen Intervention Linked to Its Phylogeny? Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e0086124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Xu, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhu, H.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Dong, Q. Formation and Recovery of Listeria Monocytogenes in Viable but Nonculturable State under Different Temperatures Combined with Low Nutrition and High NaCl Concentration. Food Res. Int. 2024, 192, 114774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. The European Union One Health 2021 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J. 2022, 20, e07666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). The European Union One Health 2023 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e9106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ); Koutsoumanis, K. ; Allende, A.; Bolton, D.; Bover-Cid, S.; Chemaly, M.; De Cesare, A.; Herman, L.; Hilbert, F.; Lindqvist, R.; Nauta, M.; Nonno, R.; Peixe, L.; Ru, G.; Simmons, M.; Skandamis, P.; Suffredini, E.; Fox, E.; Gosling, R. B.; Gil, B. M.; Møretrø, T.; Stessl, B.; da Silva Felício, M. T.; Messens, W.; Simon, A. C.; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A. Persistence of Microbiological Hazards in Food and Feed Production and Processing Environments. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e8521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centorotola, G.; Guidi, F.; D’Aurizio, G.; Salini, R.; Di Domenico, M.; Ottaviani, D.; Petruzzelli, A.; Fisichella, S.; Duranti, A.; Tonucci, F.; Acciari, V. A.; Torresi, M.; Pomilio, F.; Blasi, G. Intensive Environmental Surveillance Plan for Listeria Monocytogenes in Food Producing Plants and Retail Stores of Central Italy: Prevalence and Genetic Diversity. Foods 2021, 10, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolten, S.; Lott, T. T.; Ralyea, R. D.; Gianforte, A.; Trmcic, A.; Orsi, R. H.; Martin, N. H.; Wiedmann, M. Intensive Environmental Sampling and Whole Genome Sequence-Based Characterization of Listeria in Small- and Medium-Sized Dairy Facilities Reveal Opportunities for Simplified and Size-Appropriate Environmental Monitoring Strategies. J. Food Prot. 2024, 87, 100254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Onofrio, F.; Butler, F.; Krasteva, I.; Schirone, M.; Iannetti, L.; Torresi, M.; Di Pancrazio, C.; Perletta, F.; Maggetti, M.; Marcacci, M.; Ancora, M.; Di Domenico, M.; Di Lollo, V.; Cammà, C.; Tittarelli, M.; Sacchini, F.; Pomilio, F.; D’Alterio, N.; Luciani, M. Integrative Analysis of Transcriptomic and Immunoproteomic Data Reveals Stress Response Mechanisms in Listeria Monocytogenes. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvaniti, M.; Orologas-Stavrou, N.; Tsitsilonis, O. E.; Skandamis, P. Induction into Viable but Non Culturable State and Outgrowth Heterogeneity of Listeria Monocytogenes Is Affected by Stress History and Type of Growth. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 421, 110786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidovic, S.; Paturi, G.; Gupta, S.; Fletcher, G. C. Lifestyle of Listeria Monocytogenes and Food Safety: Emerging Listericidal Technologies in the Food Industry. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 1817–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, L.; Kjellerup, B. V.; Xu, Z. Viable but Nonculturable (VBNC) State, an Underestimated and Controversial Microbial Survival Strategy. Trends Microbiol. 2023, 31, 1013–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, R.; Duarte, A.; Tavares, L.; Barreto, A. S.; Henriques, A. R. Listeria Monocytogenes Assessment in a Ready-to-Eat Salad Shelf-Life Study Using Conventional Culture-Based Methods, Genetic Profiling, and Propidium Monoazide Quantitative PCR. Foods 2021, 10, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kragh, M. L.; Thykier, M.; Truelstrup Hansen, L. A Long-Amplicon Quantitative PCR Assay with Propidium Monoazide to Enumerate Viable Listeria Monocytogenes after Heat and Desiccation Treatments. Food Microbiol. 2020, 86, 103310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Qi, Y.; Mo, H.; Hu, L. Direct Ferrous Sulfate Exposure Facilitates the VBNC State Formation Rather than Ferroptosis in Listeria Monocytogenes. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 269, 127304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truchado, P.; Gómez-Galindo, M.; Gil, M. I.; Allende, A. Cross-Contamination of Escherichia Coli O157:H7 and Listeria Monocytogenes in the Viable but Non-Culturable (VBNC) State during Washing of Leafy Greens and the Revival during Shelf-Life. Food Microbiol. 2023, 109, 104155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.; Carreaux, A.; Sartori-Rupp, A.; Tachon, S.; Gazi, A. D.; Courtin, P.; Nicolas, P.; Dubois-Brissonnet, F.; Barbotin, A.; Desgranges, E.; Bertrand, M.; Gloux, K.; Schouler, C.; Carballido-López, R.; Chapot-Chartier, M.-P.; Milohanic, E.; Bierne, H.; Pagliuso, A. Aquatic Environment Drives the Emergence of Cell Wall-Deficient Dormant Forms in Listeria. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvaniti, M.; Tsakanikas, P.; Papadopoulou, V.; Giannakopoulou, A.; Skandamis, P. Listeria Monocytogenes Sublethal Injury and Viable-but-Nonculturable State Induced by Acidic Conditions and Disinfectants. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e0137721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagerlund, A.; Wagner, E.; Møretrø, T.; Heir, E.; Moen, B.; Rychli, K.; Langsrud, S. Pervasive Listeria Monocytogenes Is Common in the Norwegian Food System and Is Associated with Increased Prevalence of Stress Survival and Resistance Determinants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e0086122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Community. Consolidated text: Commission Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005 of 15 November 2005 on microbiological criteria for foodstuffs. OJ 2005, L 338 22.12.2005, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02005R2073-20200308, accessed on 29 November 2024.

- European Union. Commission Regulation (EU) 2024/2895 of 20 November 2024 amending Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005 as regards Listeria monocytogenes. OJ 2024, L 21.11.2024, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/2895/oj, accessed on 29 November 2024.

- Dos Reis Lemos, L. M.; Maisonnave Arisi A., C. Viability dyes quantitative PCR (vPCR) assays targeting foodborne pathogens - scientific prospecting (2010–2022). Microchemical J. 2024, 197, 109769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truchado, P.; Gil, M. I.; Larrosa, M.; Allende, A. Detection and Quantification Methods for Viable but Non-Culturable (VBNC) Cells in Process Wash Water of Fresh-Cut Produce: Industrial Validation. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; You, C. Recent Advances in Viability Detection of Foodborne Pathogens in Milk and Dairy Products. Food Control 2024, 160, 110314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Medeiros Barbosa, I.; da Cruz Almeida, É. T.; Gomes, A. C. A.; de Souza, E. L. Evidence on the Induction of Viable but Non-Culturable State in Listeria Monocytogenes by Origanum Vulgare L. and Rosmarinus Officinalis L. Essential Oils in a Meat-Based Broth. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 62, 102351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-Y.; Gui, C.-Y.; Huang, T.-C.; Hung, Y.-C.; Chen, T.-Y. Quantitative Proteomic Analysis on the Slightly Acidic Electrolyzed Water Triggered Viable but Non-Culturable Listeria Monocytogenes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xiang, Z.; Huang, T.; Xu, Z.; Ma, Q.; Yuan, L.; Soteyome, T. Development and Verification of Crossing Priming Amplification on Rapid Detection of Virulent and Viable L. Monocytogenes: In-Depth Analysis on the Target and Further Application on Food Screening. Lebenson. Wiss. Technol. 2024, 204, 116422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotoux, A.; Milohanic, E.; Bierne, H. The Viable but Non-Culturable State of Listeria Monocytogenes in the One-Health Continuum. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 849915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Yu, L.; Lin, C.; Li, K.; Chen, J.; Qin, H. Biotin Exposure-Based Immunomagnetic Separation Coupled with Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate, Propidium Monoazide, and Multiplex Real-Time PCR for Rapid Detection of Viable Salmonella Typhimurium, Staphylococcus Aureus, and Listeria Monocytogenes in Milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 6588–6597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panera-Martínez, S.; Capita, R.; García-Fernández, C.; Alonso-Calleja, C. Viability and Virulence of Listeria Monocytogenes in Poultry. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truchado, P.; Gil, M. I.; Allende, A. Peroxyacetic Acid and Chlorine Dioxide Unlike Chlorine Induce Viable but Non-Culturable (VBNC) Stage of Listeria Monocytogenes and Escherichia Coli O157:H7 in Wash Water. Food Microbiol. 2021, 100, 103866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Pang, X.; Li, X.; Bie, X.; Sun, J.; Lu, Y. Rapid and Accurate AuNPs-Sodium Deoxycholate-Propidium Monoazide-qPCR Technique for Simultaneous Detection of Viable Listeria Monocytogenes and Salmonella. Food Control 2024, 166, 110711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumani, F.; Azinheiro, S.; Carvalho, J.; Prado, M.; Garrido-Maestu, A. Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Combined with Immunomagnetic Separation and Propidium Monoazide for the Specific Detection of Viable Listeria Monocytogenes in Milk Products, with an Internal Amplification Control. Food Control 2021, 125, 107975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Shi, H. Combining Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification and Nanozyme-Strip for Ultrasensitive and Rapid Detection of Viable Listeria Monocytogenes Cells and Biofilms. Lebenson. Wiss. Technol. 2022, 154, 112641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wideman, N. E.; Oliver, J. D.; Crandall, P. G.; Jarvis, N. A. Detection and Potential Virulence of Viable but Non-Culturable (VBNC) Listeria Monocytogenes: A Review. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stingl, K.; Heise, J.; Thieck, M.; Wulsten, I. F.; Pacholewicz, E.; Iwobi, A. N.; Govindaswamy, J.; Zeller-Péronnet, V.; Scheuring, S.; Luu, H. Q.; Fridriksdottir, V.; Gölz, G.; Priller, F.; Gruntar, I.; Jorgensen, F.; Koene, M.; Kovac, J.; Lick, S.; Répérant, E.; Rohlfing, A.; Zawilak-Pawlik, A.; Rossow, M.; Schlierf, A.; Frost, K.; Simon, K.; Uhlig, S.; Huber, I. Challenging the “Gold Standard” of Colony-Forming Units - Validation of a Multiplex Real-Time PCR for Quantification of Viable Campylobacter Spp. in Meat Rinses. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 359, 109417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azinheiro, S.; Ghimire, D.; Carvalho, J.; Prado, M.; Garrido-Maestu, A. Next-Day Detection of Viable Listeria Monocytogenes by Multiplex Reverse Transcriptase Real-Time PCR. Food Control 2022, 133, 108593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfaghari, M.; Rezaei, M.; Mohabbati Mobarez, A.; Forozandeh Moghaddam, M.; Hosseini, H.; Khezri, M. Virulence Genes Expression in Viable but Non-Culturable State of Listeria Monocytogenes in Fish Meat. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2020, 26, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panera-Martínez, S.; Rodríguez-Melcón, C.; Del Campo, C.; Alonso-Calleja, C.; Capita, R. Prevalence and Levels of Cells of Salmonella Spp. and Listeria Monocytogenes in Various Physiological States Naturally Present in Chicken Meat. Food Control 2025, 167, 110770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, G.; Bolten, S.; Mowery, J.; Luo, Y.; Gulbronson, C.; Nou, X. Susceptibility of Foodborne Pathogens to Sanitizers in Produce Rinse Water and Potential Induction of Viable but Non-Culturable State. Food Control 2020, 112, 107138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauge, T.; Faille, C.; Leleu, G.; Denis, C.; Hanin, A.; Midelet, G. Treatment with Disinfectants May Induce an Increase in Viable but Non Culturable Populations of Listeria Monocytogenes in Biofilms Formed in Smoked Salmon Processing Environments. Food Microbiol. 2020, 92, 103548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, X.; Peng, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhong, Q. The Elimination Effects of Lavender Essential Oil on Listeria Monocytogenes Biofilms Developed at Different Temperatures and the Induction of VBNC State. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 74, 1016–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trigueros, S. , 2022. Metabolism measurement by Raman microspectroscopy : Application to the detection of viable but non-culturable Listeria cells, 2: en ligne. France. Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire de l'alimentation, de l'environnement et du travail", 'STAR - Dépôt national des thèses électroniques', 'Archive ouverte en agrobiosciences. Laboratoire de Boulogne sur mer. Retrieved from https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/49kr0zh on 08 Nov 2024. COI, 1259. [Google Scholar]

- Bolten, S.; Mowery, J.; Gu, G.; Redding, M.; Kroft, B.; Luo, Y.; Nou, X. Listeria Monocytogenes Loss of Cultivability on Carrot Is Associated with the Formation of Mesosome-like Structures. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 390, 110121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroft, B.; Gu, G.; Bolten, S.; Micallef, S. A.; Luo, Y.; Millner, P.; Nou, X. Effects of Temperature Abuse on the Growth and Survival of Listeria Monocytogenes on a Wide Variety of Whole and Fresh-Cut Fruits and Vegetables during Storage. Food Control 2022, 137, 108919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Flint, S.; Yu, P.-L. Changes of Cell Permeability during Listeria Monocytogenes Persistence under Nisin Treatment. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Cousineau, A.; Liu, X.; Luo, Y.; Sun, D.; Li, S.; Gu, T.; Sun, L.; Dillow, H.; Lepine, J.; Xu, M.; Zhang, B. Direct Metatranscriptome RNA-Seq and Multiplex RT-PCR Amplicon Sequencing on Nanopore MinION - Promising Strategies for Multiplex Identification of Viable Pathogens in Food. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Liu, M.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, T. Antimicrobial Mechanism of Luteolin against Staphylococcus Aureus and Listeria Monocytogenes and Its Antibiofilm Properties. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 142, 104056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Bai, J.; Yu, H.; Yang, X.; Chang, P.-S.; Nitin, N. Synergistic Inactivation of Listeria and E. Coli Using a Combination of Erythorbyl Laurate and Mild Heating and Its Application in Decontamination of Peas as a Model Fresh Produce. Food Microbiol. 2022, 102, 103869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangi, E.W.; Shemesh, M.; Rodov, V. Investigating the Antibacterial Effect of a Novel Gallic Acid-Based Green Sanitizer Formulation. Foods 2024, 13, 3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Adhikari, A. Novel Approaches to Environmental Monitoring and Control of Listeria Monocytogenes in Food Production Facilities. Foods 2022, 11, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Flint, S.; Yu, P.-L. Changes of Cell Permeability during Listeria Monocytogenes Persistence under Nisin Treatment. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewski, P.; Chajęcka-Wierzchowska, W.; Zadernowska, A. Impact of High-Pressure Processing (HPP) on Listeria Monocytogenes-an Overview of Challenges and Responses. Foods 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Su, Y.; Hua, Z.; Chiu, T.; Wang, Y.; Mendoza, M.; Hanrahan, I.; Zhu, M.-J. Evaluating Serotype-Specific Survival of Listeria Monocytogenes and Listeria Innocua on Wax-Coated Granny Smith Apples during Storage. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, No. 110964, 110964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozma, M. A.; Fadaee, M.; Hosseini, H. M.; Ataee, M. H.; Mirhosseini, S. A. A Critical Review of Postbiotics as Promising Novel Therapeutic Agents for Clostridial Infections. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stress factor (s) | Intensity -concentration | L. monocytogenes strain | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| chlorine | 10 mg/l | cocktail of six vegetable isolates, serotype 1/2a | [27] |

| ClO2 | 3 mg/l | cocktail of six vegetable isolates, serotype 1/2a | [20,35] |

| PAA | 80 mg/l | cocktail of six vegetable isolates, serotype 1/2a | [35] |

| PAA | 100 mg/l | Two foodborne strains, serogroup 1/2a | [44] |

| PAA | 40 mg/l | Scott A, serotype 4b | [22] |

| AA | pH 2.7 | Scott A, serotype 4b | [14] |

| QA | 2% v/v | Lm1 (serogroup 1/2a-3a), seafood production plant isolate | [45] |

| HP | 2% v/v | Lm1 (serogroup 1/2a-3a), seafood production plant isolate | [45] |

| OVEO | 5 and 2.5 μL/ml in PBS and meat Broth | Mixture of ATCC 7644 and ATCC 19112 (serotype: 1/2c of human origin), and ATCC 19117 (serotype: 4d of sheep origin) | [29] |

| ROEO | 5 μL/ml in PBS and 10 μL/ml in meat broth | Mixture of ATCC 7644 and ATCC 19112 (serotype: 1/2c of human origin), and ATCC 19117 (serotype: 4d of sheep origin) | [29] |

| LEO | 4 MIC (MIC=1·6 v/v) | ATCC19115 | [46] |

| Sodium hypochlorite | 4 MIC (MIC=0·219 mg/ml) | ATCC19115 | [46] |

| SAEW | 8 and 10 mg/l of available chlorine (ACC) | BCRC14845 | [30] |

| FeSO4 | 200 μM | ATCC19114 | [19] |

| Stress factor (s) | Intensity - concentration | L. monocytogenesstrain | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| biofilm desiccation | 8 days at 15 °C and 33% RH | 568 | [18] |

| starvation | Water microcosm |

ATCC 19115 (serotype 4b) | [42] |

| NaCl | 30% | ATCC 19115 (serotype 4b) | [42] |

| NaCl | 2 – 20% | Lm1 (serogroup 1/2a-3a), EGD-e (serotype 1/2a) | [47] |

| NaCl | 20-30% at 4 and -20°C | Four strains including ATCC 19115 (serotype 4b), ATCC 19111 (serotype 1/2a) | [7] |

| fresh-cut carrots, | FS 2025 serotype 1/2b, FS 2030 serotype 1/2a, FS 2061 serotype 1/2b (cantaloupe outbreak) | [49] | |

| Raw carrots | FS2025 (serotype 1/2b cantaloupe outbreak) | [48] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).