Submitted:

26 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The most common metabolic endocrine illness in women, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), swiftly impacts not only physical health but also psychological perception related to social and cultural ties that health-related quality of life (HRQOL). The HRQOL of women with PCOS is greatly affected by the constellation of symptoms that mainly accompany menstrual disorder and androgen excess. Several illnesses and conditions are more common in women with PCOS, such as obesity, insulin resistance, cardiovascular disease, infertility, cancer, and mental health issues. Managing the cases includes patient education, healthy lifestyle implementations, and the best possible therapeutic interventions, particularly based on targeting their symptoms. Therapeutic interventions include use of metformin, combined oral contraceptive pills, clomiphene citrate, spironolactone, surgery (ovarian laparoscopic drilling), and cosmetic interventions. Moreover, various new therapeutic approaches, such as use of inositol, statins, supplementation of vitamin D, miRNA therapy, interleukin-22 therapy, and faecal microbiota transplantation, bring new opportunities as well as challenges in PCOS management. This review will look at the different aspects of PCOS, other conditions that are linked to it, and the current and future ways that people with PCOS who are having trouble getting pregnant can improve their quality of life.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

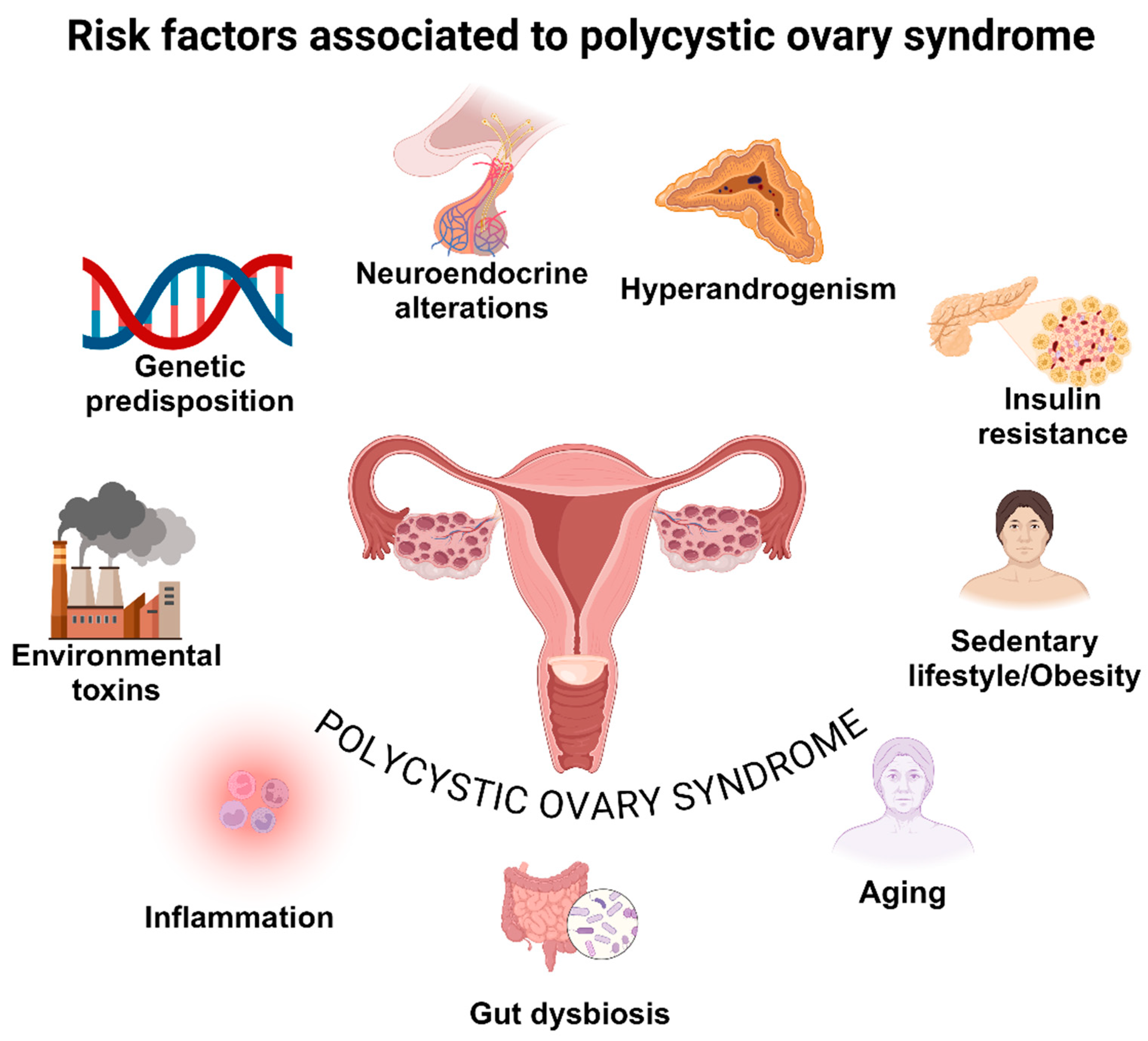

2. Pathogenesis and Clinical Manifestations in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Hyperandrogenism

Neuroendocrine Implications

GABAergic Neurons

MicroRNA

Environmental Stressors, Epigenetic Mechanisms, and Xenobiotics

Stress

Epigenetic Mechanism

Insulin Resistance

Inflammation

Oxidative Stress

Obesity

Diet

3. Clinical Features Related to Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

4. Major Co-Morbidities Related to Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Cardiovascular Disease and Dyslipidemia

Diabetes Mellitus and Gestational Diabetes

Cancer

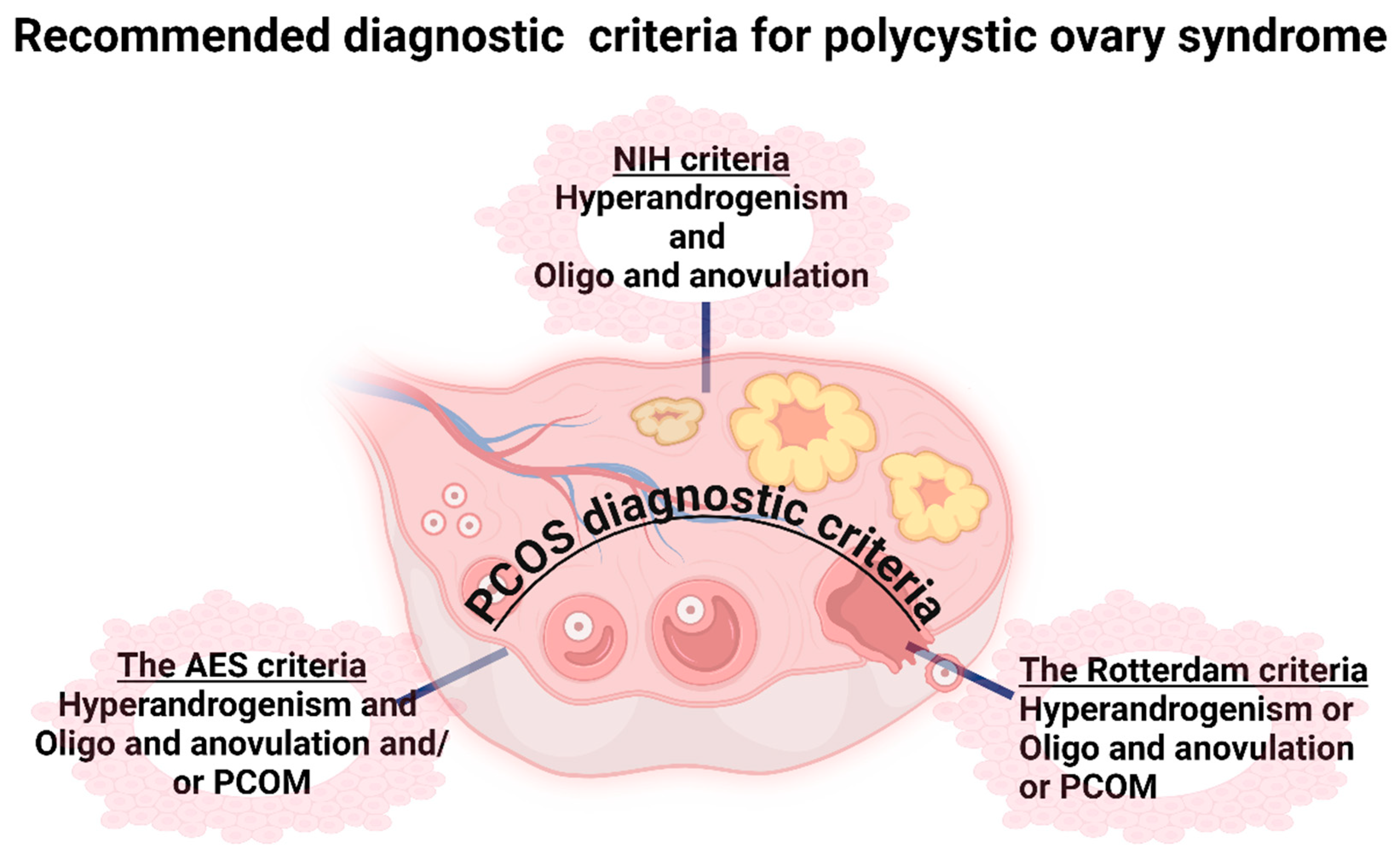

5. Criteria for Diagnosis

6. Management of PCOS

Lifestyle Modifications

Pharmacological Interventions

Antiandrogens

Antidiabetic Agents

Oral Contraceptives

Clomiphene Citrate

Gonadotropins

Aromatase Inhibitors

Laproscopic Ovarian Drilling

7. Other Pharmacological Interventions

Inositols

MicroRNA Therapy

Interleukin-22 Therapy

Restoration of the Gut Microbiome

Statins

Vitamin D and Calcium Supplements

| Category | Mechanism of action | Efficacy | Side effects | Dose/Duration | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle modifications | Lifestyle treatment (diet, exercise, behavioral or combined treatments) | Improved free androgen index, Weight reduction, Reduced body mass index, Improved OGTT | Not available | 2-3sessions of 40 to 60 minutes per week of an aerobic training programme | [111,112,159,179] | |

| OCs | ||||||

| Levonorgestrel | Binds to progesterone and androgen receptors and decreases the GnRH release from the hypothalamus | Menstrual cyclicity by inhibiting ovulation, Hirsutism, Acne |

Nausea, Breast tenderness, Bleeding, weight gain, dark pigmentation of facial skin | 30 µg/day | [161,167,175,265] | |

| Ethinyl estradiol |

Estrogen receptor (Erα or Erβ) agonist |

Inhibiting the release of gonadotropins to prevent ovulation, altering the endometrial lining to prevent implantation, and modifying cervical mucus to inhibit sperm penetration |

Headache or migraine, menstrual irregularities, nausea and vomiting, breast pain or tenderness, mood changes, fatigue, irritability, decreased libido, increased weight |

20-30 µg/day for 28 days | [161,167,175,265,266,267,268] | |

| Estradiol valerate | Headaches, irregular uterine bleeding, breast tenderness, nausea and vomiting, acne, and increased weight |

5 mg per day for 5 days | [161,167,175,269] | |||

| Cyproterone acetate | Blocking androgen receptors |

Suppresses LH Reduces testosterone level Inhibits ovulation |

Dysmenorrhea, breast tenderness, change in libido, headache, depression, nervousness, chloasma, varicosity, edema, dizziness |

2 mg per day | [161,167,175,265,267,268] | |

| Drospirenone | Aldosterone receptors antagonist | High antigonadotropic activity Blockade of ovulation Prevention of follicular growth |

PMS, headache or migraine, breast discomfort/tenderness, nausea and vomiting, abdominal discomfort, mood changes |

3 mg per day for 28 days | [161,167,175,265,268,270] | |

| Dienogest | Progesterone receptor (PR) agonist |

Progestogenic effect on the endometrium and inhibits the increase in the estradiol level through the inhibition of the growth of ovarian follicles. Inhibits ovulation |

Headaches, irregular uterine bleeding, breast tenderness, nausea and vomiting, acne, and increased weight |

2-4mg/day | [161,167,175,269,271] | |

| Chlormadinone acetate | Breast pain or tension, depressed state, loss of libido, migraine or headache | 2 mg per day | [161,167,175,269, 270,272] |

|||

| Progestins | ||||||

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | Activates the progesterone receptor | Inhibits the production of gonadotropin, preventing follicular maturation and ovulation | Amenorrhea, change in menstrual flow, hot flash, weight gain or weight loss, menstrual disease, abdominal pain, headache, nervousness | 8-10 mg per day | [161,167,175,273] | |

| Antiandrogens | ||||||

| Finasteride | Inhibitor of type II 5-alpha-reductase | Blocking androgens in the hair follicles, it lessens the PCOS-related hair loss | Risk for teratogenicity in male fetuses |

0.5 to 55 mg per day. depending on patient condition (3-4 months) | [168,170,274] | |

| Spironolactone | Competitive antagonistic activity against aldosterone receptors |

Synergism with COCs |

Nausea and menstrual irregularities Inhibition of adrenal and ovarian steroidogenesis |

50 mg bid on days 5–25 of menstrual cycle (09 months) | [275,276] | |

| Antiestrogens | ||||||

| Clomiphene citrate | Blocks ERs, Inhibiting normal estrogen negative feedback, which results in increased pulsatile GnRH secretion from the hypothalamus and pituitary gonadotropin release |

Increased pulsatile GnRH secretion from the hypothalamus. Secretion of FSH and LH. Follicle growth and maturations Ovulation induction |

Ovarian enlargement, flush, pelvic discomfort, breast discomfort, blurred vision, photophobia, diplopia, abnormal uterine bleeding intermenstrual spotting, menorrhagia |

50-100 mg per day for 5 days | [180,194,198,204] | |

| Tamoxifen | Increased bone or tumor pain, or reddening around the tumor site. Hot flashes, nausea. Excessive tiredness, dizziness, depression, headache |

60 mg/day PO 5 days |

[277,278] | |||

| Aromatase inhibitors | ||||||

| Letrozole | Competitive inhibitor of the aromatase enzyme. |

Prevents conversion of androgens to estrogens Ovulation induction |

Hot flashes, arthralgia, flushing, asthenia, edema, arthralgia, headache, dizziness, hypercholesterolemia, sweating increased, bone pain |

2.5 to 7.5 mg for 5 days | [190,203,279] | |

| Laparoscopic ovarian drilling | Surgical intervention | Ameliorating disturbances of the ovarian-pituitary feedback mechanism Promote follicular recruitment, maturation and subsequent ovulation. | Bleeding, Infection, Adhesions or scarring of ovary | None | [190,208,211,213] | |

| Gonadotrophins | ||||||

| Human menopausal gonadotropins (HMG) | Stimulate LH and FSH activity | promotes follicle maturation, stimulate ovulation and corpus luteum development. | Pain at the injection site, skin erythema, muscle pain | 75-150 U per day for 2 weeks | [280,281] | |

| Urinary FSH (uFSH) | FSH specific activity LH activity-- (<2%-5%) |

Stimulates ovary Follicle growth and maturations Ovulation induction |

Pain at injection sites Enlarged ovaries Abdominal swelling and discomfort Nausea or even vomiting |

35-40 IU per day | [282,283,284] | |

| recombinant FSH (rFSH) -99% purity |

FSH specific activity LH activity-None |

75-225 IU per day | [182,282,283] | |||

| Follitropin alpha (Human FSH rDNA preparation) |

Similar to FSH activity |

Initial dose of first cycle: 75 IU SC qDay; Dose can be increased based on response | [280,281,285] | |||

| Follitropin beta (Human FSH rDNA preparation) |

150-225 units SC/IM for at least 4 days Dose can be increased based on response |

[280,281,286] | ||||

| Antidiabetic agents | ||||||

| Metformin | Decreased glucose production (hepatic) and its intestinal absorption, Improved insulin sensitivity |

Antidiabetic agent for type II diabetes weight loss and has a lesser effect on lowering Testosterone levels. It improves ovulation and decreases androgen levels. Reduces insulin level increases insulin sensitivity. |

Diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, flatulence, asthenia, indigestion, abdominal discomfort, headache |

1500–2550 mg/day (500 1500–2550 mg/day03 months |

[138,174,175,179] | |

| Rosiglitazone | PPARγ-Agonist | Reduces BG level Increased insulin sensitivity Balances plasma lipid levels |

Allergic reactions, Headache Chest pain (angina) |

4 mg/day 06 months |

[287,288,289] | |

| Pioglitazones | PPARγ-Agonist | Reduces BG level Increased insulin sensitivity |

URTIs, Headache, Myalgia, | 15-30 mg PO with meal qDay |

[183,290] | |

| Troglitazones | PPARγ-Agonist | Reduces BG level Increased insulin sensitivity Greater effects on testosterone levels |

URTIs, Headache. UTIs. Diarrhea, Malaise Inflammation in extremities |

200-400 mg OD | [289,291] | |

|

Empagliflozin |

SGLT-2 inhibitor |

Glucose reabsorption from the PCT Lowers renal glucose threshold Reduces PCOS related comorbidities |

Urinary tract infections Female genital mycotic infections |

10 mg OD | [292,293,294] | |

|

Dapagliflozin |

Thrush, Back pain, Urinary tract infections female genital mycotic infections | 5 mg OD | [295] | |||

| Sitagliptin | DPP-4 inhibitor | Improves Incretin levels, Increases insulin synthesis |

Upper respiratory tract infection, nasopharyngitis, headache |

100 mg OD | [296,297,298] | |

|

Liraglutide |

GLP-1 receptor agonist |

Improved glucose-dependent insulin secretion and maintains glucagon secretion Reduces gastric emptying and food intake |

Tachycardia, Hypoglycemia, GI disturbances |

0.6 mg to 3 mg OD |

[299,300] | |

|

Semaglutide |

GI disturbances |

Oral dose: 7 to 14 mg orally OD. S.C. dose: 0.25 mg once a week for 4 weeks, then 0.5 mg once a week |

[301] | |||

|

Exenatide |

Hypoglycemia, GI disturbances |

5-10 mcg S.C. twice daily | [184,185] |

|||

| Statins | ||||||

| Rosuvastatin | 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase) inhibitor | Reduces HMG-CoA And cholesterol biosynthesis |

Nasopharyngitis, arthralgia Diarrhea, pain in extremity |

20 mg OD | [256,258,302] | |

| Atorvastatin | 20 mg OD | [258,303] | ||||

| Simvastatin | Upper respiratory infections headache abdominal pain constipation nausea |

20 mg OD | [81,258,260,261] | |||

| Others | ||||||

| Inositol | Second messengers of the insulin-signaling pathway synthesis. | Insulin-sensitizing and mimetic effects, lowering blood glucose and promoting hepatic glycogen | Not well-evidenced | 1000-4000 mg per day 12-24 weeks |

[214,218,219,220] | |

| miRNA therapy (small interfering RNA (siRNA), anti-miRNA oligonucleotides, miRNA mimics |

Downstream target of AR - miRNA | Downstream target of AR miR-200b, which is required for HPO axis-mediated ovulation. MiR-29c acts through the downstream pathways that affect androgen receptor localization. |

Inefficient delivery Immune mediated toxicities |

Not applicable | [36,44,229] | |

| Interleukin-22 (IL-22) therapy | Binds to IL-22 receptor complex (IL-22R) Activating the IL-22R downstream signalling pathway |

Stimulates cell proliferation, prevents apoptosis, and controls steroidogenic human granulosa-like tumor cell line (KGN) cell steroidogenesis when exposed to lipopolysaccharide | Body inflammation, osteoporosis, diabetes, and vulnerability to infection | Variable | [87,231,232,234,304,305] | |

| Gut microbiota (Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics FMTs |

Maintenance of metabolic homeostasis |

Antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory effects Modifying the immune system Regulates HA |

Not available | Variable | [237,238,248] | |

| Vitamin D | Modulation of AMH signaling, FSH sensitivity, and progesterone levels | Follicle maturation, HA, and menstrual regularity | Not reported at normal dose supplement | 50,000 IU of Vitamin D every other week for 8 weeks | [117,118,119,262] | |

9. Future Perspectives

10. Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

References

- World Health Organisation Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/polycystic-ovary-syndrome (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Louwers, Y.V.; Laven, J.S.E. Characteristics of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome throughout Life. Ther. Adv. Reprod. Health 2020, 14, 2633494120911038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, H.; Masud, J.; Islam, Y.N.; Haque, F.K.M. An Update on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Review of the Current State of Knowledge in Diagnosis, Genetic Etiology, and Emerging Treatment Options. Womens. Health 2022, 18, 17455057221117966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witchel, S.F.; Oberfield, S.E.; Peña, A.S. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Pathophysiology, Presentation, and Treatment with Emphasis on Adolescent Girls. J. Endocr. Soc. 2019, 3, 1545–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiconco, S.; Teede, H.J.; Azziz, R.; Norman, R.J.; Joham, A.E. The Need to Reassess the Diagnosis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): A Review of Diagnostic Recommendations from the International Evidence-Based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of PCOS. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2021, 39, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, C.T.; Mousa, A.; Vyas, A.; Pattuwage, L.; Tehrani, F.R.; Teede, H. 2023 International Evidence-Based Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Guideline Update: Insights from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Elevated Clinical Cardiovascular Disease in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e033572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganie, M.A.; Vasudevan, V.; Wani, I.A.; Baba, M.S.; Arif, T.; Rashid, A. Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Genetics & Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in India. Indian J. Med. Res. 2019, 150, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glueck, C.J.; Goldenberg, N. Characteristics of Obesity in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Etiology, Treatment, and Genetics. Metabolism 2019, 92, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Donnelly, R. Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) as an Early Biomarker and Therapeutic Target in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Wang, Y.; Yan, R.; Ding, B.; Ma, J. Sex Hormone Binding Globulin Is an Independent Predictor for Insulin Resistance in Male Patients with Newly Diagnosed Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Ther. 2023, 14, 1627–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, I.R.; McKinley, M.C.; Bell, P.M.; Hunter, S.J. Sex Hormone Binding Globulin and Insulin Resistance. Clin. Endocrinol. 2013, 78, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kite, C.; Lahart, I.M.; Afzal, I.; Broom, D.R.; Randeva, H.; Kyrou, I.; Brown, J.E. Exercise, or Exercise and Diet for the Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanbour, S.A.; Dobs, A.S. Hyperandrogenism in Women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: Pathophysiology and Controversies. Androg. Clin. Res. Ther. 2022, 3, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfield, R.L.; Ehrmann, D.A. The Pathogenesis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): The Hypothesis of PCOS as Functional Ovarian Hyperandrogenism Revisited. Endocr. Rev. 2016, 37, 467–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moursi, M.O.; Salem, H.; Ibrahim, A.R.; Marzouk, S.; Al-Meraghi, S.; Al-Ajmi, M.; Al-Naimi, A.; Alansari, L. The Role of Anti-Mullerian Hormone and Other Correlates in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2023, 39, 2247098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazerbourg, S.; Monget, P. Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Proteins and IGFBP Proteases: A Dynamic System Regulating the Ovarian Folliculogenesis. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruddenklau, A.; Campbell, R.E. Neuroendocrine Impairments of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Endocrinology 2019, 160, 2230–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.M.; Prescott, M.; Marshall, C.J.; Yip, S.H.; Campbell, R.E. Enhancement of a Robust Arcuate GABAergic Input to Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Neurons in a Model of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Garrido, M.A.; Tena-Sempere, M. Metabolic Dysfunction in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Pathogenic Role of Androgen Excess and Potential Therapeutic Strategies. Mol. Metab. 2020, 35, 100937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Morreale, H.F. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Definition, Aetiology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongrani, A.; Mellouk, N.; Rame, C.; Cornuau, M.; Guérif, F.; Froment, P.; Dupont, J. Ovarian Expression of Adipokines in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Role for Chemerin, Omentin, and Apelin in Follicular Growth Arrest and Ovulatory Dysfunction? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonardo, M.S.; Cacciapuoti, N.; Guida, B.; Di Lorenzo, M.; Chiurazzi, M.; Damiano, S.; Menale, C. Hypothalamic-Ovarian Axis and Adiposity Relationship in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Physiopathology and Therapeutic Options for the Management of Metabolic and Inflammatory Aspects. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2024, 13, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gołyszny, M.; Obuchowicz, E.; Zieliński, M. Neuropeptides as Regulators of the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) Axis Activity and Their Putative Roles in Stress-Induced Fertility Disorders. Neuropeptides 2022, 91, 102216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, N.; Dawalbhakta, M.; Nampoothiri, L. GnRH Dysregulation in Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) Is a Manifestation of an Altered Neurotransmitter Profile. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, B.; Qiao, J.; Pang, Y. Central Regulation of PCOS: Abnormal Neuronal-Reproductive-Metabolic Circuits in PCOS Pathophysiology. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 667422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawwass, J.F.; Sanders, K.M.; Loucks, T.L.; Rohan, L.C.; Berga, S.L. Increased Cerebrospinal Fluid Levels of GABA, Testosterone and Estradiol in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 1450–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, M.; Fukuda, A.; Nabekura, J. The Role of GABA in the Regulation of GnRH Neurons. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veldhuis, J.D. The Hypothalamic Pulse Generator: The Reproductive Core. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990, 33, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, F.R.; Ornat, L.; López-Baena, M.T.; Santabárbara, J.; Savirón-Cornudella, R.; Pérez-Roncero, G.R. Circulating Kisspeptin and Anti-Müllerian Hormone Levels, and Insulin Resistance in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 260, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Qu, T.; Li, Z.; Yu, L.; Zhang, S.; Yuan, D.; Wu, H. Serum Kisspeptin Levels in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2021, 47, 2157–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hestiantoro, A.; Noor Al Maghfira, R.; Fathmasari, R.; Rahmala Febri, R.; Ongko Joyo, E.; Muharam, R.; Pratama, G.; Bowolaksono, A. Altered Expression of Kisspeptin, Dynorphin, and Related Neuropeptides in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2024, 22, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, M.A.; Shah, N.; Deshmukh, H.; Sahebkar, A.; Östlundh, L.; Al-Rifai, R.H.; Atkin, S.L.; Sathyapalan, T. Impact of Pharmacological Interventions on Biochemical Hyperandrogenemia in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 307, 1347–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbara, A.; Clarke, S.A.; Dhillo, W.S. Clinical Potential of Kisspeptin in Reproductive Health. Trends Mol. Med. 2021, 27, 807–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.-L.; Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Cai, E.; Yang, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C.; Ju, L.; Deng, W.; Mu, L. Advances in Clinical Applications of Kisspeptin-GnRH Pathway in Female Reproduction. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2022, 20, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deswal, R.; Dang, A.S. Dissecting the Role of Micro-RNAs as a Diagnostic Marker for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 113, 661–669.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Cui, C.; Han, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, C. The Role of miRNAs in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome with Insulin Resistance. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2021, 38, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidarzadehpilehrood, R.; Pirhoushiaran, M. Biomarker Potential of Competing Endogenous RNA Networks in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). Noncoding RNA Res. 2024, 9, 624–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís-Toro, D.; Mosquera Escudero, M.; García-Perdomo, H.A. Association between Circulating microRNAs and the Metabolic Syndrome in Adult Populations: A Systematic Review. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2022, 16, 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Mohamed, I.N.; Teoh, S.L.; Thevaraj, T.; Ku Ahmad Nasir, K.N.; Zawawi, A.; Salim, H.H.; Zhou, D.K. Micro-RNA and the Features of Metabolic Syndrome: A Narrative Review. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneghan, H.M.; Miller, N.; Kerin, M.J. Role of microRNAs in Obesity and the Metabolic Syndrome. Obes. Rev. 2010, 11, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Mu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, M.; Wan, J.; Qin, X.; Li, C. MicroRNA-200 and microRNA-30 Family as Prognostic Molecular Signatures in Ovarian Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2018, 97, e11505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, M.T.; Arbitrio, M.; Caracciolo, D.; Cordua, A.; Cuomo, O.; Grillone, K.; Riillo, C.; Caridà, G.; Scionti, F.; Labanca, C.; et al. miR-221/222 as Biomarkers and Targets for Therapeutic Intervention on Cancer and Other Diseases: A Systematic Review. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2022, 27, 1191–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, S.G.; Fulghesu, A.M.; Mikuš, M.; Watrowski, R.; D’Alterio, M.N.; Lin, L.-T.; Shah, M.; Reyes-Muñoz, E.; Sathyapalan, T.; Angioni, S. The Translational Role of miRNA in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: From Bench to Bedside-A Systematic Literature Review. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteves, J.V.; Enguita, F.J.; Machado, U.F. MicroRNAs-Mediated Regulation of Skeletal Muscle GLUT4 Expression and Translocation in Insulin Resistance. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 2017, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Y.; Mao, L.; Zuo, M.-L.; Song, G.-L.; Tan, L.-M.; Yang, Z.-B. The Role of MicroRNAs in Hyperlipidemia: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutical Application. Mediators Inflamm. 2022, 2022, 3101900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedgeman, L.R.; Michell, D.L.; Vickers, K.C. Integrative Roles of microRNAs in Lipid Metabolism and Dyslipidemia. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2019, 30, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wu, G.; Zheng, L. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction of Granulosa Cells in Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1193749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeber-Lubecka, N.; Ciebiera, M.; Hennig, E.E. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Oxidative Stress-from Bench to Bedside. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippou, P.; Homburg, R. Is Foetal Hyperexposure to Androgens a Cause of PCOS? Hum. Reprod. Update 2017, 23, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puttabyatappa, M.; Cardoso, R.C.; Padmanabhan, V. Effect of Maternal PCOS and PCOS-like Phenotype on the Offspring’s Health. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2016, 435, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E.; Papalou, O.; Kandaraki, E. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and PCOS: A Novel Contributor in the Etiology of the Syndrome. In Polycystic Ovary Syndrome; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 227–244. [Google Scholar]

- Peralta, M.; Lizcano, F. Endocrine Disruptors and Metabolic Changes: Impact on Puberty Control. Endocr. Pract. 2024, 30, 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivonello, C.; Muscogiuri, G.; Nardone, A.; Garifalos, F.; Provvisiero, D.P.; Verde, N.; de Angelis, C.; Conforti, A.; Piscopo, M.; Auriemma, R.S.; et al. Bisphenol A: An Emerging Threat to Female Fertility. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2020, 18, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srnovršnik, T.; Virant-Klun, I.; Pinter, B. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Endocrine Disruptors (Bisphenols, Parabens, and Triclosan)-A Systematic Review. Life 2023, 13, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chang, H.; Wiseman, S.; He, Y.; Higley, E.; Jones, P.; Wong, C.K.C.; Al-Khedhairy, A.; Giesy, J.P.; Hecker, M. Bisphenol A Disrupts Steroidogenesis in Human H295R Cells. Toxicol. Sci. 2011, 121, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.L.; Tee, M.K. The Post-Translational Regulation of 17,20 Lyase Activity. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015, 408, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, A.E.; Ford, E.A.; Roman, S.D.; Bromfield, E.G.; Nixon, B.; Pringle, K.G.; Sutherland, J.M. Impact of Bisphenol A and Its Alternatives on Oocyte Health: A Scoping Review. Hum. Reprod. Update 2024, 30, 653–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahra, Z.; Khan, M.R.; Majid, M.; Maryam, S.; Sajid, M. Gonadoprotective Ability of Vincetoxicum Arnottianum Extract against Bisphenol A-Induced Testicular Toxicity and Hormonal Imbalance in Male Sprague Dawley Rats. Andrologia 2020, 52, e13590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, T.; Cipelli, R.; Guralnik, J.; Ferrucci, L.; Bandinelli, S.; Corsi, A.M.; Money, C.; McCormack, P.; Melzer, D. Daily Bisphenol A Excretion and Associations with Sex Hormone Concentrations: Results from the InCHIANTI Adult Population Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 1603–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, B.R.; Chowdhury, O.; Saha, S.K. Possible Link between Stress-Related Factors and Altered Body Composition in Women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2018, 11, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papalou, O.; Diamanti-Kandarakis, E. The Role of Stress in PCOS. Expert Rev. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 12, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisco, V.; Pino, J.; Gonzalez-Gay, M.A.; Mera, A.; Lago, F.; Gómez, R.; Mobasheri, A.; Gualillo, O. Adipokines and Inflammation: Is It a Question of Weight?: Obesity and Inflammatory Diseases. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 1569–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojnović Milutinović, D.; Teofilović, A.; Veličković, N.; Brkljačić, J.; Jelača, S.; Djordjevic, A.; Macut, D. Glucocorticoid Signaling and Lipid Metabolism Disturbances in the Liver of Rats Treated with 5α-Dihydrotestosterone in an Animal Model of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Endocrine 2021, 72, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, J.J.; Kuppusamy, M.; Koshy, T.; Kalburgi Narayana, M.; Ramaswamy, P. Cortisol and Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome - a Systematic Search and Meta-Analysis of Case-Control Studies. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2021, 37, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiweko, B.; Indra, I.; Susanto, C.; Natadisastra, M.; Hestiantoro, A. The Correlation between Serum AMH and HOMA-IR among PCOS Phenotypes. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md Muslim, M.Z.; Mohammed Jelani, A.; Shafii, N.; Yaacob, N.M.; Che Soh, N.A.A.; Ibrahim, H.A. Correlation between Anti-Mullerian Hormone with Insulin Resistance in Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Ovarian Res. 2024, 17, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama, G.; Wiweko, B.; Asmarinah; Widyahening, I.S.; Andraini, T.; Bayuaji, H.; Hestiantoro, A. Mechanism of Elevated LH/FSH Ratio in Lean PCOS Revisited: A Path Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Kaur, M.; Beri, A.; Kaur, A. Significance of LHCGR Polymorphisms in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: An Association Study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattori, N.; Fujiwara, H.; Maeda, M.; Fujii, S.; Ueda, M. Epoxide Hydrolase Affects Estrogen Production in the Human Ovary. Endocrinology 2000, 141, 3353–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Feng, R.; Xu, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhao, X.; Xing, Q.; et al. Quantitative Methylation Level of the EPHX1 Promoter in Peripheral Blood DNA Is Associated with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. PLoS One 2014, 9, e88013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogacka, I.; Kurzynska, A.; Bogacki, M.; Chojnowska, K. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors in the Regulation of Female Reproductive Functions. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 2015, 53, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitti, M.; Di Emidio, G.; Di Carlo, M.; Carta, G.; Antonosante, A.; Artini, P.G.; Cimini, A.; Tatone, C.; Benedetti, E. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors in Female Reproduction and Fertility. PPAR Res. 2016, 2016, 4612306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psilopatis, I.; Vrettou, K.; Nousiopoulou, E.; Palamaris, K.; Theocharis, S. The Role of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, X.; Nie, X.; He, B. Insulin Resistance in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome across Various Tissues: An Updated Review of Pathogenesis, Evaluation, and Treatment. J. Ovarian Res. 2023, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, E.; Winston, N.; Stocco, C. Molecular Crosstalk between Insulin-like Growth Factors and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone in the Regulation of Granulosa Cell Function. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2024, 23, e12575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piau, T.B.; de Queiroz Rodrigues, A.; Paulini, F. Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF) Performance in Ovarian Function and Applications in Reproductive Biotechnologies. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2023, 72–73, 101561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpentier, A.C. 100th Anniversary of the Discovery of Insulin Perspective: Insulin and Adipose Tissue Fatty Acid Metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 320, E653–E670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Morreale, H.F.; Luque-Ramírez, M.; González, F. Circulating Inflammatory Markers in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 1048–58.e1-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboeldalyl, S.; James, C.; Seyam, E.; Ibrahim, E.M.; Shawki, H.E.-D.; Amer, S. The Role of Chronic Inflammation in Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Shao, Y.; Xie, J.; Chen, L.; Zhu, G. The Efficacy and Safety of Metformin Combined with Simvastatin in the Treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Medicine 2021, 100, e26622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, S.; Khurram, E.; Moorthi, V.S.; Eissa, Y.T.H.; Kamal, M.A.; Butler, A.E. The Interplay between Androgens and the Immune Response in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham Gnanadass, S.; Divakar Prabhu, Y.; Valsala Gopalakrishnan, A. Association of Metabolic and Inflammatory Markers with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS): An Update. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 303, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, S.L.; Dasgupta, T.; Cummings, M.; Orsi, N.M. Cytokines in Ovarian Folliculogenesis, Oocyte Maturation and Luteinisation: Cytokines in Folliculogenesis. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2014, 81, 284–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Pang, Y. Systemic and Ovarian Inflammation in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2022, 151, 103628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Pando, J.M.; Alcocer-Gómez, E.; Castejón-Vega, B.; Navarro-Villarán, E.; Condés-Hervás, M.; Mundi-Roldan, M.; Muntané, J.; Pérez-Pulido, A.J.; Bullon, P.; Wang, C.; et al. Inhibition of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Prevents Ovarian Aging. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabc7409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Yu, K.; Yang, Z. Associations between TNF-α and Interleukin Gene Polymorphisms with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2015, 32, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhuriji, A.F.; Al Omar, S.Y.; Babay, Z.A.; El-Khadragy, M.F.; Mansour, L.A.; Alharbi, W.G.; Khalil, M.I. Association of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and TGFβ1 Gene Polymorphisms with Recurrent Spontaneous Abortion in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Dis. Markers 2020, 2020, 6076274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, K.; Zhang, Y. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Strategies in Human Diseases. In Oxidative Stress; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 1–26. ISBN 9789811605215. [Google Scholar]

- Zarkovic, N. Roles and Functions of ROS and RNS in Cellular Physiology and Pathology. Cells 2020, 9, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Meo, S.; Reed, T.T.; Venditti, P.; Victor, V.M. Role of ROS and RNS Sources in Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 1245049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Kong, X.; Shu, C.; Liu, Y.; Shi, Y. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Ovarian Aging: A Review. J. Ovarian Res. 2022, 15, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalonde-Bester, S.; Malik, M.; Masoumi, R.; Ng, K.; Sidhu, S.; Ghosh, M.; Vine, D. Prevalence and Etiology of Eating Disorders in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Scoping Review. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, C.A.; Pérez de la Lastra, J.M.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. The Chemistry of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Revisited: Outlining Their Role in Biological Macromolecules (DNA, Lipids and Proteins) and Induced Pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, M.J.; Liu, Z.-G. Crosstalk of Reactive Oxygen Species and NF-κB Signaling. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingappan, K. NF-κB in Oxidative Stress. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2018, 7, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murri, M.; Luque-Ramírez, M.; Insenser, M.; Ojeda-Ojeda, M.; Escobar-Morreale, H.F. Circulating Markers of Oxidative Stress and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2013, 19, 268–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, V.A.; Carvalho, D.; Freitas, P. Obesity, Adipose Tissue, and Inflammation Answered in Questions. J. Obes. 2022, 2022, 2252516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savulescu-Fiedler, I.; Mihalcea, R.; Dragosloveanu, S.; Scheau, C.; Baz, R.O.; Caruntu, A.; Scheau, A.-E.; Caruntu, C.; Benea, S.N. The Interplay between Obesity and Inflammation. Life 2024, 14, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, X.; Ibrahim, M.; Peltzer, N. Cell Death and Inflammation during Obesity: “Know My Methods, WAT(Son). ” Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.M.; Nahmgoong, H.; Yim, K.M.; Kim, J.B. How Obesity Affects Adipocyte Turnover. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Karpe, F.; Dickmann, J.R.; Frayn, K.N. Fatty Acids, Obesity, and Insulin Resistance: Time for a Reevaluation. Diabetes 2011, 60, 2441–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bril, F.; Ezeh, U.; Amiri, M.; Hatoum, S.; Pace, L.; Chen, Y.-H.; Bertrand, F.; Gower, B.; Azziz, R. Adipose Tissue Dysfunction in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 109, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocken, J.W.E.; Blaak, E.E. Catecholamine-Induced Lipolysis in Adipose Tissue and Skeletal Muscle in Obesity. Physiol. Behav. 2008, 94, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arner, P. Catecholamine-Induced Lipolysis in Obesity. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 1999, 23 (Suppl. S1), 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.F.; Deng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, R.R.; Chan, J.C.N.; Laybutt, D.R.; Luzuriaga, J.; Xu, G. Pharmacological Reduction of NEFA Restores the Efficacy of Incretin-Based Therapies through GLP-1 Receptor Signalling in the Beta Cell in Mouse Models of Diabetes. Diabetologia 2013, 56, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chueire, V.B.; Muscelli, E. Effect of Free Fatty Acids on Insulin Secretion, Insulin Sensitivity and Incretin Effect - a Narrative Review. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 65, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizneva, D.; Suturina, L.; Walker, W.; Brakta, S.; Gavrilova-Jordan, L.; Azziz, R. Criteria, Prevalence, and Phenotypes of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 106, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.J.; Ullah, A.; Basit, S. Genetic Basis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): Current Perspectives. Appl. Clin. Genet. 2019, 12, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.; Mateen, S.; Ahmad, R.; Moin, S. A Brief Insight into the Etiology, Genetics, and Immunology of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS). J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2022, 39, 2439–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domecq, J.P.; Prutsky, G.; Mullan, R.J.; Hazem, A.; Sundaresh, V.; Elamin, M.B.; Phung, O.J.; Wang, A.; Hoeger, K.; Pasquali, R.; et al. Lifestyle Modification Programs in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 4655–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, L.J.; Hutchison, S.K.; Norman, R.J.; Teede, H.J. Lifestyle Changes in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, CD007506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Hu, M.; Feng, H. Effect of Diet on Insulin Resistance in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, 3346–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, F.; Considine, R.V.; Abdelhadi, O.A.; Acton, A.J. Inflammation Triggered by Saturated Fat Ingestion Is Linked to Insulin Resistance and Hyperandrogenism in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, e2152–e2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, F.; Considine, R.V.; Abdelhadi, O.A.; Xue, J.; Acton, A.J. Saturated Fat Ingestion Stimulates Proatherogenic Inflammation in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 321, E689–E701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, H.-C.; Tsai, S.-F.; Chou, H.-W.; Tsai, M.-J.; Hsu, P.-L.; Kuo, Y.-M. Dietary Fatty Acids Differentially Affect Secretion of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in Human THP-1 Monocytes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Ni, K.; Cai, Y.; Shang, J.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, C. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2017, 26, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, A.; Haider, R.; Fakhor, H.; Hina, F.; Kumar, V.; Jawed, A.; Majumder, K.; Ayaz, A.; Lal, P.M.; Tejwaney, U.; et al. Vitamin D and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): A Review. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 85, 3506–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Cao, Q.; Qiao, X.; Huang, W. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Hormones and Menstrual Cycle Regularization in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Women: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2023, 49, 2232–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACOG committee. Screening and Management of the Hyperandrogenic Adolescent: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 789. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 134, e106–e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azziz, R.; Carmina, E.; Dewailly, D.; Diamanti-Kandarakis, E.; Escobar-Morreale, H.F.; Futterweit, W.; Janssen, O.E.; Legro, R.S.; Norman, R.J.; Taylor, A.E.; et al. The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society Criteria for the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: The Complete Task Force Report. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 91, 456–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollila, M.M.; West, S.; Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi, S.; Jokelainen, J.; Auvinen, J.; Puukka, K.; Ruokonen, A.; Järvelin, M.-R.; Tapanainen, J.S.; Franks, S.; et al. Overweight and Obese but Not Normal Weight Women with PCOS Are at Increased Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus-a Prospective, Population-Based Cohort Study. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.-J.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, H.K.; Kim, Y.J.; Yi, K.W.; Shin, J.H.; Hur, J.Y.; Kim, T.; Park, H. Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Is Increased in Nonobese Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: The National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort Study. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 115, 1569–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brutocao, C.; Zaiem, F.; Alsawas, M.; Morrow, A.S.; Murad, M.H.; Javed, A. Psychiatric Disorders in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endocrine 2018, 62, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, K.M.; Fenton, A.J.; Eggleston, K.; Porter, R.J. Rate of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Mental Health Disorders: A Systematic Review. Arch. Womens. Ment. Health 2022, 25, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabassum, F.; Jyoti, C.; Sinha, H.H.; Dhar, K.; Akhtar, M.S. Impact of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome on Quality of Life of Women in Correlation to Age, Basal Metabolic Index, Education and Marriage. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0247486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Zhao, J.; Ye, Y.; Sun, Z.; Li, K.; Chen, Y.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, J.; Sun, P.; et al. Risk and Incidence of Cardiovascular Disease Associated with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2024, 31, 1560–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osibogun, O.; Ogunmoroti, O.; Michos, E.D. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Cardiometabolic Risk: Opportunities for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 30, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wekker, V.; van Dammen, L.; Koning, A.; Heida, K.Y.; Painter, R.C.; Limpens, J.; Laven, J.S.E.; Roeters van Lennep, J.E.; Roseboom, T.J.; Hoek, A. Long-Term Cardiometabolic Disease Risk in Women with PCOS: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2020, 26, 942–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, M.L.; Malek, A.M.; Wild, R.A.; Korytkowski, M.T.; Talbott, E.O. Carotid Artery Intima-Media Thickness in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2012, 18, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osibogun, O.; Ogunmoroti, O.; Kolade, O.B.; Hays, A.G.; Okunrintemi, V.; Minhas, A.S.; Gulati, M.; Michos, E.D. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Association between Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Coronary Artery Calcification. J. Womens. Health 2022, 31, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, J.C.; Feigenbaum, S.L.; Yang, J.; Pressman, A.R.; Selby, J.V.; Go, A.S. Epidemiology and Adverse Cardiovascular Risk Profile of Diagnosed Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 1357–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.-F.; Chen, H.-S.; Rao, D.-P.; Gong, J. Association between Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and the Risk of Pregnancy Complications: A PRISMA-Compliant Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2016, 95, e4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Xian, P.; Yang, D.; Zhang, C.; Tang, H.; He, X.; Lin, H.; Wen, X.; Ma, H.; Lai, M. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Is an Independent Risk Factor for Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression. Endocrine 2021, 74, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention QuickStats: Percentage of Mothers with Gestational Diabetes,* by Maternal Age - National Vital Statistics System, United States, 2016 and 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeting, A.; Hannah, W.; Backman, H.; Catalano, P.; Feghali, M.; Herman, W.H.; Hivert, M.-F.; Immanuel, J.; Meek, C.; Oppermann, M.L.; et al. Epidemiology and Management of Gestational Diabetes. Lancet 2024, 404, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plows, J.F.; Stanley, J.L.; Baker, P.N.; Reynolds, C.M.; Vickers, M.H. The Pathophysiology of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legro, R.S.; Zaino, R.J.; Demers, L.M.; Kunselman, A.R.; Gnatuk, C.L.; Williams, N.I.; Dodson, W.C. The Effects of Metformin and Rosiglitazone, Alone and in Combination, on the Ovary and Endometrium in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 196, 402.e1-10, discussion 402.e10-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, A.A.; Rajeswari, V.D. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) Increases the Risk of Subsequent Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM): A Novel Therapeutic Perspective. Life Sci. 2022, 310, 121069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holte, J.; Gennarelli, G.; Wide, L.; Lithell, H.; Berne, C. High Prevalence of Polycystic Ovaries and Associated Clinical, Endocrine, and Metabolic Features in Women with Previous Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998, 83, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koivunen, R.M.; Juutinen, J.; Vauhkonen, I.; Morin-Papunen, L.C.; Ruokonen, A.; Tapanainen, J.S. Metabolic and Steroidogenic Alterations Related to Increased Frequency of Polycystic Ovaries in Women with a History of Gestational Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 2591–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ni, Y. Association between Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome and Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Meta-Analysis. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 2022, 87, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Yao, Y.; Wang, T.; Wu, J.; Jiang, R. The Impact of Hyperandrogenemia on Pregnancy Complications and Outcomes in Patients with PCOS: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2024, 43, 2379389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, R.; Sikonja, J.; Jensterle, M.; Janez, A.; Dolzan, V. Insulin Metabolism in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Secretion, Signaling, and Clearance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute Obesity and Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/obesity/obesity-fact-sheet (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Onstad, M.A.; Schmandt, R.E.; Lu, K.H. Addressing the Role of Obesity in Endometrial Cancer Risk, Prevention, and Treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 4225–4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, S.; Brown, K.; Miksza, J.K.; Howells, L.M.; Morrison, A.; Issa, E.; Yates, T.; Khunti, K.; Davies, M.J.; Zaccardi, F. Risk of Cancer Incidence and Mortality Associated with Diabetes: A Systematic Review with Trend Analysis of 203 Cohorts. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, A.V.; Pasupuleti, V.; Benites-Zapata, V.A.; Thota, P.; Deshpande, A.; Perez-Lopez, F.R. Insulin Resistance and Endometrial Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2015, 51, 2747–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, D.-C.; Chen, W.; Wang, J.-H.; Lin, S.-Z. Association between Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome and Endometrial, Ovarian, and Breast Cancer: A Population-Based Cohort Study in Taiwan. Medicine 2018, 97, e12608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meczekalski, B.; Pérez-Roncero, G.R.; López-Baena, M.T.; Chedraui, P.; Pérez-López, F.R. The Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Gynecological Cancer Risk. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2020, 36, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renehan, A.G.; Tyson, M.; Egger, M.; Heller, R.F.; Zwahlen, M. Body-Mass Index and Incidence of Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Observational Studies. Lancet 2008, 371, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-M. Estrogen, Progesterone and Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2003, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, H.R.; Titus, L.J.; Cramer, D.W.; Terry, K.L. Long and Irregular Menstrual Cycles, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, and Ovarian Cancer Risk in a Population-based Case-control Study. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 140, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Child Health. How Do Health Care Providers Diagnose PCOS? Available online: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/pcos/conditioninfo/diagnose (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- National Institute of Health Evidence-Based Methodology Workshop on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). Available online: https://prevention.nih.gov/research-priorities/research-needs-and-gaps/pathways-prevention/evidence-based-methodology-workshop-polycystic-ovary-syndrome-pcos (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Teede, H.J.; Tay, C.T.; Laven, J.J.E.; Dokras, A.; Moran, L.J.; Piltonen, T.T.; Costello, M.F.; Boivin, J.; Redman, L.M.; Boyle, J.A.; et al. Recommendations from the 2023 International Evidence-Based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 108, 2447–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewailly, D.; Lujan, M.E.; Carmina, E.; Cedars, M.I.; Laven, J.; Norman, R.J.; Escobar-Morreale, H.F. Definition and Significance of Polycystic Ovarian Morphology: A Task Force Report from the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society. Hum. Reprod. Update 2014, 20, 334–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsugbe, E. An Artificial Intelligence-Based Decision Support System for Early Diagnosis of Polycystic Ovaries Syndrome. Healthcare Analytics 2023, 3, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.S.; Hutchison, S.K.; Van Ryswyk, E.; Norman, R.J.; Teede, H.J.; Moran, L.J. Lifestyle Changes in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3, CD007506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, D.; Bhattacharya, S. Obesity and Fertility. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2015, 24, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Mo, T.; Li, Q.; Shen, C.; Liu, M. The Effectiveness of Metformin, Oral Contraceptives, and Lifestyle Modification in Improving the Metabolism of Overweight Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Network Meta-Analysis. Endocrine 2019, 64, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, N.; O’Connor, A.; Kyaw Tun, T.; Correia, N.; Boran, G.; Roche, H.M.; Gibney, J. Hormonal and Metabolic Effects of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Young Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Results from a Cross-Sectional Analysis and a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, E.; Samimi, M.; Ebrahimi, F.A.; Foroozanfard, F.; Ahmadi, S.; Rahimi, M.; Jamilian, M.; Aghadavod, E.; Bahmani, F.; Taghizadeh, M.; et al. The Effects of Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Vitamin E Co-Supplementation on Gene Expression of Lipoprotein(a) and Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein, Lipid Profiles and Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2017, 439, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajishafiee, M.; Askari, G.; Iranj, B.; Ghiasvand, R.; Bellissimo, N.; Totosy de Zepetnek, J.; Salehi-Abargouei, A. The Effect of N-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Supplementation on Androgen Status in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Horm. Metab. Res. 2016, 48, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, S.; Nayak, P.K.; Agrawal, S. Laparoscopic Ovarian Drilling: An Alternative but Not the Ultimate in the Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2015, 6, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadalla, M.A.; Norman, R.J.; Tay, C.T.; Hiam, D.S.; Melder, A.; Pundir, J.; Thangaratinam, S.; Teede, H.J.; Mol, B.W.J.; Moran, L.J. Medical and Surgical Treatment of Reproductive Outcomes in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 13, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forslund, M.; Melin, J.; Alesi, S.; Piltonen, T.; Romualdi, D.; Tay, C.T.; Witchel, S.; Pena, A.; Mousa, A.; Teede, H. Different Kinds of Oral Contraceptive Pills in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2023, 189, S1–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesi, S.; Forslund, M.; Melin, J.; Romualdi, D.; Peña, A.; Tay, C.T.; Witchel, S.F.; Teede, H.; Mousa, A. Efficacy and Safety of Anti-Androgens in the Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 63, 102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elenis, E.; Desroziers, E.; Persson, S.; Sundström Poromaa, I.; Campbell, R.E. Early Initiation of Anti-Androgen Treatment Is Associated with Increased Probability of Spontaneous Conception Leading to Childbirth in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Population-Based Multiregistry Cohort Study in Sweden. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 36, 1427–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrionuevo, P.; Nabhan, M.; Altayar, O.; Wang, Z.; Erwin, P.J.; Asi, N.; Martin, K.A.; Murad, M.H. Treatment Options for Hirsutism: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 1258–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.E., Jr; Shander, D.; Huber, F.; Jackson, J.; Lin, C.-S.; Mathes, B.M.; Schrode, K.; the Eflornithine HCl Study Group. Randomized, Double-blind Clinical Evaluation of the Efficacy and Safety of Topical Eflornithine HCl 13.9% Cream in the Treatment of Women with Facial Hair. Int. J. Dermatol. 2007, 46, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, J.; Caro, J.J.; Caro, G.; Garfield, F.; Huber, F.; Zhou, W.; Lin, C.-S.; Shander, D.; Schrode, K.; Eflornithine HCl Study Group. The Effect of Eflornithine 13.9% Cream on the Bother and Discomfort Due to Hirsutism. Int. J. Dermatol. 2007, 46, 976–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.R.; Piacquadio, D.J.; Beger, B.; Littler, C. Eflornithine Cream Combined with Laser Therapy in the Management of Unwanted Facial Hair Growth in Women: A Randomized Trial. Dermatol. Surg. 2006, 32, 1237–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, J.; Forslund, M.; Alesi, S.; Piltonen, T.; Romualdi, D.; Spritzer, P.M.; Tay, C.T.; Pena, A.; Witchel, S.F.; Mousa, A.; et al. The Impact of Metformin with or without Lifestyle Modification versus Placebo on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2023, 189, S37–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melin, J.; Forslund, M.; Alesi, S.; Piltonen, T.; Romualdi, D.; Spritzer, P.M.; Tay, C.T.; Pena, A.; Witchel, S.F.; Mousa, A.; et al. Metformin and Combined Oral Contraceptive Pills in the Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 109, e817–e836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, J.M.; Forslund, M.; Alesi, S.J.; Piltonen, T.; Romualdi, D.; Spritzer, P.M.; Tay, C.T.; Pena, A.S.; Witchel, S.F.; Mousa, A.; et al. Effects of Different Insulin Sensitisers in the Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Endocrinol. 2024, 100, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, M.A.; Shah, N.; Deshmukh, H.; Sahebkar, A.; Östlundh, L.; Al-Rifai, R.H.; Atkin, S.L.; Sathyapalan, T. The Effect of Thiazolidinediones in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Adv. Ther. 2024, 41, 2168–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tso, L.O.; Costello, M.F.; Albuquerque, L.E.T.; Andriolo, R.B.; Macedo, C.R. Metformin Treatment before and during IVF or ICSI in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 12, CD006105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H.; Chon, S.J.; Lee, S.H. Effects of Lifestyle Modification in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Compared to Metformin Only or Metformin Addition: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Hashim, H.; Foda, O.; Ghayaty, E. Combined Metformin-Clomiphene in Clomiphene-Resistant Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2015, 94, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, S.; Sanchita, S. Clomiphene Citrate, Metformin or a Combination of Both as the First Line Ovulation Induction Drug for Asian Indian Women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2015, 8, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begum, M.R.; Akhter, S.; Ehsan, M.; Begum, M.S.; Khan, F. Pretreatment and Co-Administration of Oral Anti-Diabetic Agent with Clomiphene Citrate or rFSH for Ovulation Induction in Clomiphene-Citrate-Resistant Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Pretreatment and Co-Administration. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2013, 39, 966–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, J.; Xing, C.; Cheng, X.; He, B. Metformin versus Metformin plus Pioglitazone on Gonadal and Metabolic Profiles in Normal-Weight Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Single-Center, Open-Labeled Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Ovarian Res. 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Song, X.; Hamiti, S.; Ma, Y.; Yusufu, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, K.; Guo, Y. Comparison of Exenatide Alone or Combined with Metformin versus Metformin in the Treatment of Polycystic Ovaries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2023, 23, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.-R.; Yan, C.-Q.; Liao, N.; Wen, S.-H. The Effectiveness and Safety of Exenatide versus Metformin in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Reprod. Sci. 2023, 30, 2349–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensterle, M.; Janez, A.; Fliers, E.; DeVries, J.H.; Vrtacnik-Bokal, E.; Siegelaar, S.E. The Role of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 in Reproduction: From Physiology to Therapeutic Perspective. Hum. Reprod. Update 2019, 25, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cena, H.; Chiovato, L.; Nappi, R.E. Obesity, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, and Infertility: A New Avenue for GLP-1 Receptor Agonists. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, e2695–e2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensterle, M.; Herman, R.; Janež, A. Therapeutic Potential of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Agonists in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: From Current Clinical Evidence to Future Perspectives. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyrides, A.A.; El Mahdi, E.; Giannakou, K. Ovulation Induction Techniques in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 982230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franik, S.; Le, Q.-K.; Kremer, J.A.; Kiesel, L.; Farquhar, C. Aromatase Inhibitors (Letrozole) for Ovulation Induction in Infertile Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 9, CD010287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, K.; Olanrewaju, R.A.; Omole, F. Infertility: Evaluation and Management. Am. Fam. Physician 2023, 107, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dai, M.; Hong, L.; Yin, T.; Liu, S. Disturbed Follicular Microenvironment in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Relationship to Oocyte Quality and Infertility. Endocrinology 2024, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Hofe, J.; Bates, G.W. Ovulation Induction. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 2015, 42, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadalla, M.A.; Huang, S.; Wang, R.; Norman, R.J.; Abdullah, S.A.; El Saman, A.M.; Ismail, A.M.; van Wely, M.; Mol, B.W.J. Effect of Clomiphene Citrate on Endometrial Thickness, Ovulation, Pregnancy and Live Birth in Anovulatory Women: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 51, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorlitsky, G.A.; Kase, N.G.; Speroff, L. Ovulation and Pregnancy Rates with Clomiphene Citrate. Obstet. Gynecol. 1978, 51, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gysler, M.; March, C.M.; Mishell, D.R., Jr.; Bailey, E.J. A Decade’s Experience with an Individualized Clomiphene Treatment Regimen Including Its Effect on the Postcoital Test. Fertil. Steril. 1982, 37, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kousta, E.; White, D.M.; Franks, S. Modern Use of Clomiphene Citrate in Induction of Ovulation. Hum. Reprod. Update 1997, 3, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huppert, L.C. Induction of Ovulation with Clomiphene Citrate. Fertil. Steril. 1979, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, G.; Yan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, J.; Tong, N.; Wang, Y. The Effects of First-Line Pharmacological Treatments for Reproductive Outcomes in Infertile Women with PCOS: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2023, 21, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, N.S.; Kostova, E.; Nahuis, M.; Mol, B.W.J.; van der Veen, F.; van Wely, M. Gonadotrophins for Ovulation Induction in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 1, CD010290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, N.; van Wely, M.; van Der Veen, F. Recombinant FSH versus Urinary Gonadotrophins or Recombinant FSH for Ovulation Induction in Subfertility Associated with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2001, CD002121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Geng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Hu, R.; Li, F.; Song, Y.; Zhang, M. Letrozole Compared with Clomiphene Citrate for Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 141, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandelbaum, R.S.; Agarwal, R.; Melville, S.; Violette, C.J.; Winer, S.; Shoupe, D.; Matsuo, K.; Paulson, R.J.; Quinn, M.M. A Comparison of Letrozole Regimens for Ovulation Induction in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. F S Rep. 2024, 5, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Zaid, A.; Gari, A.; Sabban, H.; Alshahrani, M.S.; Khadawardi, K.; Badghish, E.; AlSghan, R.; Bukhari, I.A.; Alyousef, A.; Abuzaid, M.; et al. Comparison of Letrozole and Clomiphene Citrate in Pregnancy Outcomes in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Reprod. Sci. 2024, 31, 883–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Shu, J.; Guo, J.; Chang, H.-M.; Leung, P.C.K.; Sheng, J.-Z.; Huang, H. Adjuvant Treatment Strategies in Ovarian Stimulation for Poor Responders Undergoing IVF: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2020, 26, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkar, A.; Jadoon, B.; Ali Baig, M.M.; Irfan, S.A.; El-Gayar, M.; Siddiqui, F.Z. Is Combined Letrozole and Clomiphene Superior to Either as Monotherapy: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis Based on Clinical Trials. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2024, 40, 2405114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, I.F.; Leventhal, M.L. Amenorrhea Associated with Bilateral Polycystic Ovaries. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1935, 29, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebbi, I.; Ben Temime, R.; Fadhlaoui, A.; Feki, A. Ovarian Drilling in PCOS: Is It Really Useful? Front. Surg. 2015, 2, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seow, K.-M.; Chang, Y.-W.; Chen, K.-H.; Juan, C.-C.; Huang, C.-Y.; Lin, L.-T.; Tsui, K.-H.; Chen, Y.-J.; Lee, W.-L.; Wang, P.-H. Molecular Mechanisms of Laparoscopic Ovarian Drilling and Its Therapeutic Effects in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjönnaess, H. Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome Treated by Ovarian Electrocautery through the Laparoscope. Fertil. Steril. 1984, 41, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Hashim, H. Predictors of Success of Laparoscopic Ovarian Drilling in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: An Evidence-Based Approach. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015, 291, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, P.; Agrawal, S.; Mitra, S. Laparoscopic Ovarian Drilling: An Alternative but Not the Ultimate in the Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2015, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordewijk, E.M.; Ng, K.Y.B.; Rakic, L.; Mol, B.W.J.; Brown, J.; Crawford, T.J.; van Wely, M. Laparoscopic Ovarian Drilling for Ovulation Induction in Women with Anovulatory Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2, CD001122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiNicolantonio, J.J.; H O’Keefe, J. Myo-Inositol for Insulin Resistance, Metabolic Syndrome, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Gestational Diabetes. Open Heart 2022, 9, e001989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unfer, V.; Porcaro, G. Updates on the Myo-Inositol plus D-Chiro-Inositol Combined Therapy in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 7, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genazzani, A.D. Inositol as Putative Integrative Treatment for PCOS. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2016, 33, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzarri, M.; Carlomagno, G. Inositol: History of an Effective Therapy for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 18, 1896–1903. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dinicola, S.; Chiu, T.T.Y.; Unfer, V.; Carlomagno, G.; Bizzarri, M. The Rationale of the Myo-Inositol and D-Chiro-Inositol Combined Treatment for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 54, 1079–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greff, D.; Juhász, A.E.; Váncsa, S.; Váradi, A.; Sipos, Z.; Szinte, J.; Park, S.; Hegyi, P.; Nyirády, P.; Ács, N.; et al. Inositol Is an Effective and Safe Treatment in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2023, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitz, V.; Graca, S.; Mahalingaiah, S.; Liu, J.; Lai, L.; Butt, A.; Armour, M.; Rao, V.; Naidoo, D.; Maunder, A.; et al. Inositol for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis to Inform the 2023 Update of the International Evidence-Based PCOS Guidelines. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 109, 1630–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides-Aguilar, J.A.; Torres-Copado, A.; Isidoro-Sánchez, J.; Pathak, S.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Banerjee, A.; Paul, S. The Regulatory Role of MicroRNAs in Obesity and Obesity-Derived Ailments. Genes 2023, 14, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murri, M.; Insenser, M.; Fernández-Durán, E.; San-Millán, J.L.; Luque-Ramírez, M.; Escobar-Morreale, H.F. Non-Targeted Profiling of Circulating microRNAs in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): Effects of Obesity and Sex Hormones. Metabolism 2018, 86, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Xu, P.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C. The Role of MiRNA in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). Gene 2019, 706, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insenser, M.; Quintero, A.; de Lope, S.; Álvarez-Blasco, F.; Martínez-García, M.Á.; Luque-Ramírez, M.; Escobar-Morreale, H.F. Validation of Circulating microRNAs miR-142-3p and miR-598-3p in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome as Potential Diagnostic Markers. Hum. Reprod. 2023, 38, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, S.-P.; Zhang, T.; Yu, B.; Zhang, J.; Ding, H.-G.; Ye, F.-J.; Yuan, H.; Ma, Y.-Y.; Pan, H.-T.; et al. High Throughput microRNAs Sequencing Profile of Serum Exosomes in Women with and without Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, M.; Deshmukh, H.; Atkin, S.L.; Sathyapalan, T. miRNAs as a Novel Clinical Biomarker and Therapeutic Targets in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): A Review. Life Sci. 2020, 259, 118174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, L.; Sun, X.; Tu, M.; Zhang, D. Non-Coding RNAs in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2021, 19, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Z.; Li, T.; Zhao, H.; Qin, Y.; Wang, X.; Kang, Y. Identification of Epigenetic Interactions between microRNA and DNA Methylation Associated with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 66, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, X.; Zhang, L.; Tian, C.; Wu, T.; Ye, H.; Cao, J.; Chen, F.; Liang, Y.; Yang, H.; Huang, C. Interleukin-22 and Connective Tissue Diseases: Emerging Role in Pathogenesis and Therapy. Cell Biosci. 2021, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, P.; Dubey, S. IL-22 as a Target for Therapeutic Intervention: Current Knowledge on Its Role in Various Diseases. Cytokine 2023, 169, 156293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Yun, C.; Liao, B.; Qiao, J.; Pang, Y. The Therapeutic Effect of Interleukin-22 in High Androgen-Induced Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 245, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Hu, R.; Ma, W.; Wu, X.; Dong, H.; Song, K.; Xu, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, F.; et al. Opportunities and Challenges: Interleukin-22 Comprehensively Regulates Polycystic Ovary Syndrome from Metabolic and Immune Aspects. J. Ovarian Res. 2023, 16, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksun, S.; Ersal, E.; Portakal, O.; Yildiz, B.O. Interleukin-22/Interleukin-22 Binding Protein Axis and Oral Contraceptive Use in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Endocrine 2023, 81, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Liao, B.; Yun, C.; Zhao, M.; Pang, Y. Interlukin-22 Improves Ovarian Function in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Independent of Metabolic Regulation: A Mouse-Based Experimental Study. J. Ovarian Res. 2024, 17, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.Z.; Liu, Z.; Duan, Y.; Chen, Y. Interleukin-22 Promotes Proliferation and Reverses LPS-Induced Apoptosis and Steroidogenesis Attenuation in Human Ovarian Granulosa Cells: Implications for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Pathogenesis. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal Med. 2023, 36, 2253347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, S.; Sayeed Akhtar, M.; Faiyaz Khan, M.; Aldosari, S.A.; Mukherjee, M.; Sharma, A.K. Molecular Basis of Phytochemical-Gut Microbiota Interactions. Drug Discov. Today 2023, 28, 103824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtdaş, G.; Akdevelioğlu, Y. A New Approach to Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: The Gut Microbiota. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2020, 39, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, X. Effects of Intestinal Flora on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angoorani, P.; Ejtahed, H.-S.; Ettehad Marvasti, F.; Taghavi, M.; Mohammadpour Ahranjani, B.; Hasani-Ranjbar, S.; Larijani, B. The Effects of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics on Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Front. Med. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Hu, R.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, F.; Li, F.; Liu, Z.; Geng, Y.; Dong, H.; Ma, W.; Song, K.; et al. Present and Future: Crosstalks between Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Gut Metabolites Relating to Gut Microbiota. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Wang, J. Oxidative Stress Tolerance and Antioxidant Capacity of Lactic Acid Bacteria as Probiotic: A Systematic Review. Gut Microbes 2020, 12, 1801944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.M.; Kim, J.-S.; Kim, H.-S.; Kim, Y.-Y.; Oh, J.-K.; Jung, H.-W.; Park, D.-S.; Bae, K.-H. Lactobacillus Reuteri AN417 Cell-Free Culture Supernatant as a Novel Antibacterial Agent Targeting Oral Pathogenic Bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-C.; Wu, C.-R.; Huang, T.-W. Preventive Effect of Probiotics on Oral Mucositis Induced by Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Chu, J.; Feng, S.; Guo, C.; Xue, B.; He, K.; Li, L. Immunological Mechanisms of Inflammatory Diseases Caused by Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis: A Review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 164, 114985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.-X.; Chen, X.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in Health and Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Luo, J.; Lin, H. Exploration of the Pathogenesis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Based on Gut Microbiota: A Review. Medicine 2023, 102, e36075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, R.; Ostadmohammadi, V.; Akbari, M.; Lankarani, K.B.; Vakili, S.; Peymani, P.; Karamali, M.; Kolahdooz, F.; Asemi, Z. The Effects of Probiotic Supplementation on Clinical Symptom, Weight Loss, Glycemic Control, Lipid and Hormonal Profiles, Biomarkers of Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2022, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Gao, S.; Ye, C.; Zhao, W. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Mechanisms of Progression and Clinical Applications. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Society of Microbiology Fecal Microbiota Transplants (FMT): Past, Present and Future. Available online: https://asm.org/articles/2024/february/fecal-microbiota-transplants-past-present-future (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Zecheng, L.; Donghai, L.; Runchuan, G.; Yuan, Q.; Qi, J.; Yijia, Z.; Shuaman, R.; Xiaoqi, L.; Yi, W.; Ni, M.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Obesity Metabolism: A Meta Analysis and Systematic Review. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 202, 110803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tariq, R.; Syed, T.; Yadav, D.; Prokop, L.J.; Singh, S.; Loftus, E.V.; Pardi, D.S.; Khanna, S. Outcomes of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for C. difficile Infection in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2023, 57, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Ma, N.; Zhou, Z.; Lu, W.; Wu, C. Gut Microbiota in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: An Individual Based Analysis of Publicly Available Data. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 77, 102884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moadi, L.; Turjeman, S.; Asulin, N.; Koren, O. The Effect of Testosterone on the Gut Microbiome in Mice. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Geng, H.; Ye, C.; Liu, J. Dysbiotic Alteration in the Fecal Microbiota of Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yan, J.; Li, S.; Liu, M.; Han, R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D. Efficacy of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endocrine 2023, 84, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, C.; Zhang, T.; Gong, W.; Deng, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, J.; Guo, Y. The Effects of Statins on Hyperandrogenism in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamerra, C.A.; Di Giosia, P.; Ferri, C.; Giorgini, P.; Reiner, Z.; Johnston, T.P.; Sahebkar, A. Statin Therapy and Sex Hormones. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 890, 173745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolnikaj, T.S.; Herman, R.; Janež, A.; Jensterle, M. The Current and Emerging Role of Statins in the Treatment of PCOS: The Evidence to Date. Medicina 2024, 60, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy-Vu, L.; Joe, E.; Kirk, J.K. Role of Statin Drugs for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Family Reprod. Health 2016, 10, 165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Shawish, M.I.; Bagheri, B.; Musini, V.M.; Adams, S.P.; Wright, J.M. Effect of Atorvastatin on Testosterone Levels. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 1, CD013211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Zhu, Y. Efficacy of Simvastatin plus Metformin for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 257, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Cheng, D.; Yin, T.-L.; Yang, J. Vitamin D and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Narrative Review. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 28, 2110–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Ostadmohammadi, V.; Lankarani, K.B.; Tabrizi, R.; Kolahdooz, F.; Heydari, S.T.; Kavari, S.H.; Mirhosseini, N.; Mafi, A.; Dastorani, M.; et al. The Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on Biomarkers of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress among Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Horm. Metab. Res. 2018, 50, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]