The quality of higher education (HE) plays a key role in the progress of any state. Innovative approaches to improving the quality of HE in the context of global digitalization not only open up new opportunities but also create, as the analysis of the literature has shown, additional risks that require careful analysis and management. Recognizing these risks and opportunities, we propose considering the interaction of two key players in the HE system. These players are responsible for allocating resources between the processes of education informatization and ensuring computer security in universities. Within our model, we reduce various types of resources (financial, human, intellectual, technical, organizational) to a single financial equivalent. This simplification allows for the creation of a universal resource allocation model and facilitates quantitative analysis. However, we acknowledge the limitations of such an approach and recognize that some qualitative aspects of resources may not be fully reflected in the financial assessment. Therefore, when interpreting the model results, it will be necessary to additionally consider the qualitative characteristics of resources and the specifics of their application.

4.1. Problem Statement

There are two players: The first player is the Cybersecurity Center (hereinafter referred to as the CSC). It has resources aimed at ensuring cybersecurity, for example, it can be assumed that the center has cybersecurity tools for which resources must be allocated. These tools can be called the CSC's technological strategies. The second player is the Education Financing Center (hereinafter referred to as the EFC). Its main task is to improve the quality of education, including through the introduction of IT into the learning process, such as cloud technologies and other innovative solutions. It is assumed that the second player has tools (its technological strategies) that it can use to improve the quality of education.

For example, consider a small list of player strategies, each of which will require corresponding resources that can ultimately be reduced to the dimension of financial resources (RES) with the limitations that were discussed above, see

Table 1.

Interdependence in the financing of cybersecurity and education informatization is a complex dynamic mechanism where one player's resources influence the actions and needs of the other. For example, funding the Cybersecurity Center (CSC) directly stimulates additional investments in the informatization of the educational process. This is because the more funds are directed towards introducing IT into education, the more pressing cybersecurity issues become, and consequently, the more resources are required to address them effectively.

On the other hand, a high level of cybersecurity creates attractive conditions for the introduction of new IT. Thus, increasing investments in cybersecurity not only protects existing university information systems but also serves as a powerful incentive for further innovation. This, in turn, will contribute to improving the quality of educational services in universities. This interdependence of financing processes leads to a conflict of interest between the players, as one of them often finds themselves unable to meet the financial demands of the other. A shortage of resources - especially financial ones - can block the implementation of their own technological strategies.

In this regard, in our research, we will use the term "resource" (RES) to denote all the necessary funds allocated by the players. The conflicting relationship between the CSC and the Education Financing Center (EFC) becomes the basis for applying game theory, namely an antagonistic game, in the task of finding optimal strategies for the participants. We consider this interaction as a differential quality game, which allows us to take into account changes and adaptation of player strategies depending on current conditions. The interaction between the players occurs continuously over time, emphasizing its dynamic nature. As already mentioned, the first player (CSC) allocates funding to its technological strategies aimed at protecting cybersecurity, while the second player (EFC) funds its strategies aimed at improving the quality of education through the introduction of IT. The EFC's investment in its technological initiatives, in turn, requires additional funds from the CSC to ensure their protection, creating a closed loop of mutual dependencies and financial obligations.

Let's assume that is a technological strategy of the EFC that leads to the need for the CSC to spend resources in the amount of . Then, is a technological strategy of the CSC that leads to a cost of resources for the EFC in the amount of . Let's give an example.

Suppose the EFC wants to introduce a new online learning system (this is the technological strategy of the EFC). The EFC invests in a platform for conducting online courses. The introduction of this system will require additional CS measures; accordingly, the CSC needs to allocate additional resources () to strengthen the protection of the personal data of students and teachers, as well as to protect against DDoS attacks on online learning servers.

In response, the CSC introduces a multi-factor authentication system (this is the technological strategy of the CSC). The introduction of this CS system, in turn, will allow the EFC to expand the functionality of the online platform, including conducting online exams and attracting more foreign students due to the increased level of data protection, as well as reducing the risks of financial losses from possible cyberattacks. However, this will require additional investments from the EFC () in the development and adaptation of the educational platform for new opportunities provided by the increased level of CS.

Thus, one can clearly see in this small example how the actions of one center (the introduction of a new technology) lead to the need for additional investments from the other center, and vice versa, which, in fact, illustrates the relationship and mutual influence of the strategies of both players in the proposed model.

Let us denote by the ratio , and by the ratio . If is very large for some and j, or is very large for some , then such strategies are excluded from consideration.

Let's assume that is a matrix of size , consisting of elements . The number of rows of the matrix is the number of technological strategies of the EFC. In the matrix , the number of each row is the technological strategy of the EFC. The column numbers of are the technological strategies of the CSC. Then is a matrix of size . In , the row numbers are the technological strategies of the CSC. The column numbers of are the technological strategies of the EFC. We obtain that the elements mean that they are located in the row and column.

Let us denote by the ratio, and by the ratio. If it is very large for some and j or is very large for some, then such strategies are excluded from consideration.

To make further calculations more compact, we introduce the following notations:

Elements of a diagonal matrix order : . Matrix characterizes the 'structure' of the EFC's resources.

"represents a portion of the CSC's resource set, which is transformed into a component of the same size within the EFC's resource set. What does this situation correspond to? If we have a CSC resource set of size , then the y-component of the EFC's resource set of the same magnitude is transformed into a CSC resource set equivalent to ."

The elements of the diagonal matrix are ordered by :: XX:X. Matrix describes the structure of the CSC's resource set. Each element in represents a share of the EFC's resource set, which is transformed into a corresponding component in the CSC's resource set.

This means that if there is a resource set in the EFC represented by , then in the component, the resource set magnitude of the CSC is transformed to match the resource set magnitude of the CFO, also represented by ."

We assume that there exists a set of resources, , available to the Central Design Bureau (CDB) for operation. represents a multidimensional vector, which is intended to indicate the full set of CFO resources. However, in practice, this product only allows for determining a single component of the CFO's resource vector. This is because the entirety of vector is effectively “spent” on this one component. There are no additional resources from the CSC that are “resource-equivalent” to this component within the EFC’s resources.

The complete set of CSC resources has been utilized to “equalize” its “resource equivalence” with just one component of the EFC’s resource set. Essentially, the CSC’s resources have been directed towards additional funding for one specific EFC strategy. Consequently, the CSC lacks any remaining resources to support further allocations or funding of other EFC strategies.

In other words, all available CSC resources have been expended on a single EFC strategy. As a result, the EFC is in a position to continue its financing process using its remaining resources and strategies, thereby placing the CSC in a vulnerable position, as its resource (financial) capacity has already been depleted in support of only one of the multiple EFC strategies.

Therefore, it becomes necessary to divide the set of resources into separate parts. This partitioning would enable the "equalization" of the efficiency of the EFC’s resource sets across all components, matching them with proportional shares of the CSC’s resources. To facilitate this, a set of elements within is introduced. This same approach can be applied to the set of EFC resources.

In this work, the reasoning is conducted from the perspective of the first player-ally. This implies that no assumptions are made about the level of awareness of the Education Financing Center (EFC), which is equivalent to a situation where the EFC has complete information. Thus, the EFC may have a complete understanding of the state of the Cybersecurity Center (CSC), as well as all of its actions and strategies.

The CSC, at time , converts its resources into resources of magnitude . Here, represents a resource transformation matrix for the CSC, which is of order and consists of positive elements. The CSC then makes a strategic move by choosing the quantity of resources , where is a diagonal matrix composed of elements . This magnitude of CSC resources leads to additional financing for the EFC, amounting to .

Similarly, the EFC, at time , converts its resources into resources of size . Here, is the resource transformation matrix for the EFC, also of order and consisting of positive elements. The EFC then makes its strategic move by choosing its resource amount , where is a diagonal matrix of order , containing elements . This magnitude of the EFC's resources also leads to additional financing for the EFC, amounting to .

At time

, the resources of both players, the EFC and CSC, satisfy the following system of differential equations:

At the moment of time

The following variants are possible:

where

Condition (2) indicates that the Cybersecurity Center (CSC) has sufficient resources to interact with the Education Financing Center (EFC), while the EFC lacks resources. In this case, the interaction ends.

Condition (3) indicates a situation where the EFC has sufficient resources to interact with the CSC, while the CSC lacks resources. In such a case, the interaction also ceases.

Condition (4) states that both players do not have enough resources to continue the interaction, which also leads to its completion.

If condition (5) is met, the interaction process between the players continues.

The financing process described in system (1) is considered within the framework of a positional differential game of quality with several terminal surfaces [

11,

12]. We focus on analyzing the problem from the perspective of the first allied player, given the symmetry of the conditions. The problem, considered from the position of the second allied player, is solved in a similar way.

Let's denote by – time interval

Definition. A pure strategy for the first player (ally) is defined as a set of functions such that . Specifically, a pure strategy for the first player (ally) is a predetermined set of actions or decisions made to protect cybersecurity. The second player (opponent) then chooses their strategy . Based on any information. For example, a pure strategy of the CSC (player-ally). Suppose the CSC decides to implement a comprehensive protection system that includes: a) Installing a modern firewall; b) Implementing a multi-factor authentication system; c) Implementing a SIEM. This is a specific set of actions that represents a pure strategy of the CSC. Then, the strategy of the EFC (player-opponent) is determined based on the fact that the EFC, knowing about the actions of the CSC, can choose its own strategy. For example, implement such strategies: a) increase funding for the implementation of a new online learning system; b) invest in cloud storage for educational materials; c) expand communication opportunities with students using social networks. Accordingly, the CSC seeks to determine such initial conditions (for example, the initial budget, the number of personnel, the current level of protection) under which it will be able to ensure the required level of cybersecurity, despite the actions of the EFC.

For example, the CSC might seek answers to questions such as: 1) With what minimum initial budget can we ensure protection from all major cyber threats? 2) What is the minimum number of cybersecurity specialists that the university initially needs to cope with the increased load due to new IT systems? 3) What level of basic protection should we have initially so that we can successfully resist new threats arising from the expansion of the university's digital infrastructure? In fact, the CSC seeks to find such initial conditions under which it can ensure the necessary level of cybersecurity, regardless of which strategy the EFC chooses to expand the use of IT in education. That is, the first allied player seeks to find a set of its initial states that have the following property.

Property: If the game starts from the initial states, the first allied player can choose a strategy that ensures the fulfillment of condition (2) at a specific point in time . Moreover, this chosen strategy prevents the EFC from fulfilling condition (3) at previous points in time. In other words, this property indicates that the first allied player can select a strategy guaranteeing that, at some moment in time , the EFC will lack sufficient resources to fund its technological strategies further. Thus, the first allied player's strategy should be such that it reduces the resource capabilities of the EFC to a level where additional financing of its technological strategies becomes impossible.

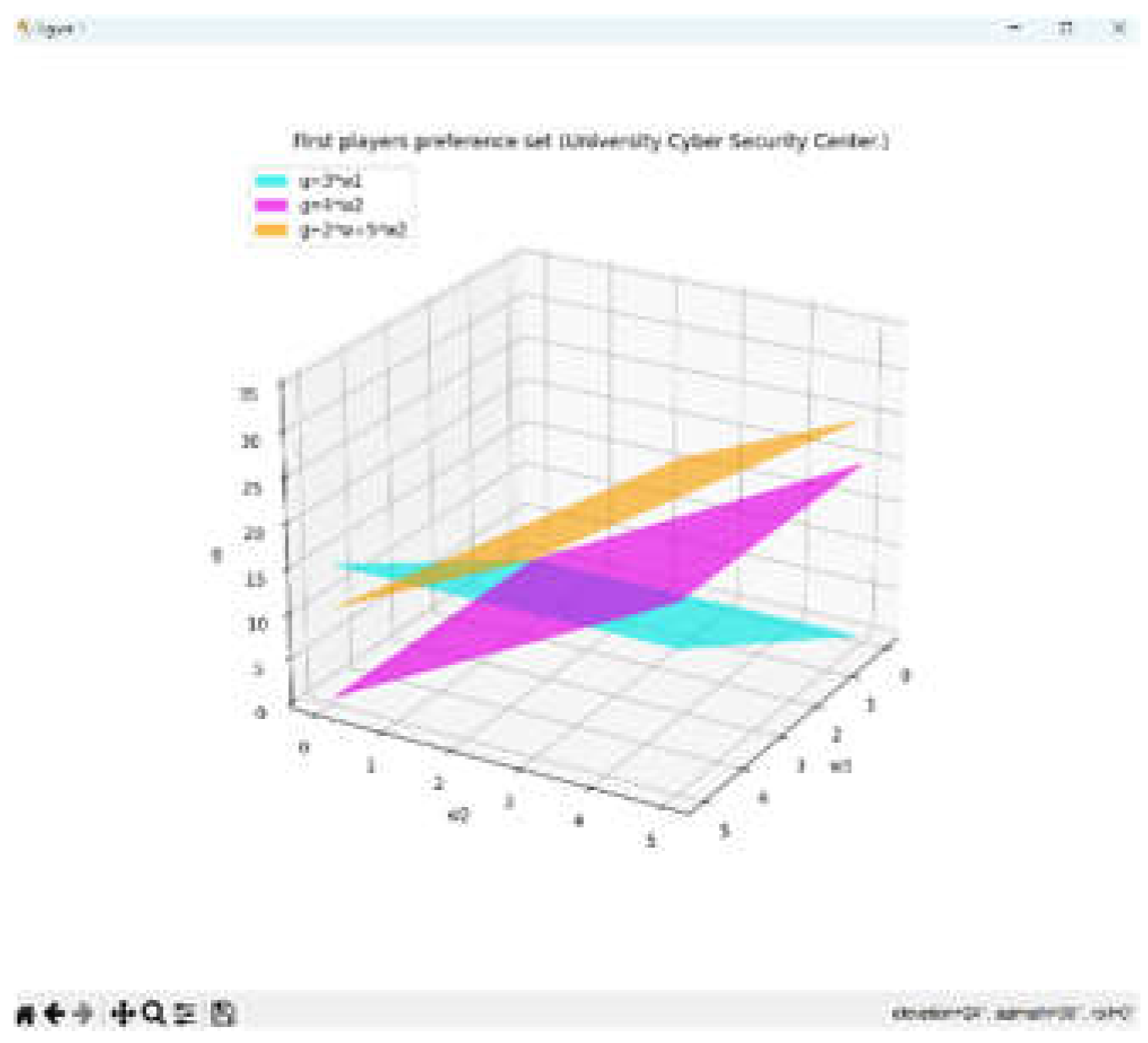

A set of such states represents the preferences of the first allied player, , whose strategies we will denote as 's strategies. The CSC, with its specified properties, represents 's optimal strategies."

The goal of the first allied player is to find preference sets. They also find strategies that, when applied, will lead to the fulfillment of condition (2).

The described model is a bilinear differential quality game with multiple terminal surfaces [

11].

The following paragraph presents the conditions that will allow us to find a solution to the game. That is, we can find 'preference' sets. and optimal strategies of the first player-ally (CSC).

4.2. Solution to Problem 1

A brief outline of the analytical solution to problem 1 is presented in this article for one of the variants of the game's parameter ratio. Solutions for other variants can be found similarly, utilizing the potential of cybernetic modeling tools.

Let us introduce the following notation:, , ,

Solution to problem 1 depends on the ratio of parameters that determine the interaction between the first player-ally and the second player-opponent.

All cases of the ratio of parameters, we will present in the form of two cases.

, , (these are matrix inequalities),

– Diagonal matrix;

,

,

.

When analyzing the interaction between the CSC and the EFC, several scenarios can be distinguished, depending on the ratio of their parameters and initial conditions.

Scenario 1: CSC Advantage. In this situation, the CSC has the opportunity to achieve its goal of ensuring the necessary level of cybersecurity if the initial conditions are favorable. For example, the CSC may start with a significant advantage in resources, such as: 1) a substantial initial budget for cybersecurity; 2) The presence of highly qualified specialists; 3) The use of advanced data protection technologies. At the same time, the EFC may face limitations that prevent it from fully realizing its goals for digitalizing education. For example, limited funding for the implementation of new IT systems or a lack of technical specialists to deploy new educational platforms.

Scenario 2: Equal Opportunities. In this scenario, both the CSC and the EFC start with comparable resources and capabilities. For example: 1) both centers have similar budgets for implementing their strategies; 2) both have access to modern technologies in their respective fields; 3) the teams of both centers have a comparable level of expertise in decision-making. In such a situation, the success of each center will depend on their ability to effectively utilize available resources and adapt to the actions of each other. The CSC can focus on developing flexible cybersecurity systems and data protection systems that can quickly respond to new threats arising from the introduction of IT innovations by the EFC. In turn, the EFC can focus on selecting educational technologies that initially have a high level of built-in security. It should be noted that these scenarios are extreme cases, and the real situation may be somewhere in between them or have a more complex structure of interaction between the CSC and the EFC.

Further, we introduce the following notations:

Here ,

– sum of elements - The strings of the matrix ,

– sum of elements - The strings of the matrix ,

.

The outcome of the players' interaction is represented in a theorem that describes the preference set of the first player (ally), which reflects the advantage of this player over the opponent. This advantage is expressed in the following ways:

The quantity of resources available.

The efficiency of resource allocation, represented in matrices and .

The implementation of the optimal strategy where is the identity matrix of order \times and is undefined otherwise.

It is important to note that the methodology for determining optimal strategies and preferred initial conditions is applicable to both the CSC and the EFC, despite their different roles in our model. For the CSC, the process of determining optimal strategies and the most favorable initial conditions is based on the analysis of various scenarios for the development of the cybersecurity situation in the educational environment. In this case, the CSC assesses which initial resources and which strategic decisions will allow it to most effectively ensure cybersecurity and protect the information infrastructure of universities, taking into account the possible actions of the EFC to digitalize education.

For the EFC, a similar approach is used, as the EFC also conducts an analysis to determine its optimal strategies and preferred initial conditions. However, the focus here shifts to assessing which initial resources and which strategic decisions will allow for the most effective implementation of innovative educational technologies, taking into account the need to ensure their cybersecurity and the possible response actions of the CSC.

Thus, although the goals of the CSC and the EFC are different, the methodological approach to determining their optimal strategies and preferred initial conditions is similar, which will allow for the analytical creation of a balanced model that takes into account the interests of both parties in the process of digital transformation of the higher education system of the Republic of Kazakhstan.