1. Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is a hematologic malignancy caused by dysregulated proliferation of immature lymphoid cells. This dysregulation primarily occurs in the bone marrow, but can extend extramedullary to the peripheral blood or various organ systems. The uncontrolled differentiation and spread of leukemia is engendered by alterations at the chromosomal and genetic level. These genetic mutations ultimately guide the classification, sub-classification, prognosis, and treatment of this complex malignancy [

1,

2].

While ALL is primarily a pediatric leukemia, it can also occur in adults, accounting for approximately 20% of leukemias that occur in the adult population. Given its predominance in the pediatric population, changes and improvements in the treatment of ALL typically are first demonstrated in children and then extended and further studied in adults subsequently. Of note, cure rates in children with ALL exceed 90% in more recent years [

3,

4].

Unfortunately, despite the use of pediatric based regimens and novel immunotherapeutics or other targeted therapies, cure rates in adults with ALL remains low, with a 5 year overall survival of only 20-40% of patients. For patients older than 70 years of age with ALL, the long term survival is even lower at less than 5% [

5].

Therefore, continued research into how to improve ALL treatment remains vital, in the effort to improve remission rates, overall survival, and treatment-related toxicities. Current guidelines for the treatment of adult ALL typically involve an algorithmic approach utilizing multi-agent chemotherapy regimens and the consideration of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) for patients with high-risk of relapsed disease. Regimens are further subdivided into specific phases of induction, consolidation, and maintenance therapy. Measurable residual disease (MRD) testing has also become an essential part in guiding the choice and intensity of these various phases [

2].Recently, genetic profiling has also become paramount with the use of targeted therapies. For example, in Philadelphia chromosome positive (Ph+) ALL, the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) has significantly improved outcomes when combined with chemotherapy [

6]. As is the case for many other malignancies, immunotherapy has also been extensively studied in ALL and shown early promise, with the incorporation of monoclonal antibodies, such as rituximab and inotuzumab ozogamicin, and the bispecific T-cell engager, blinatumomab, into treatment regimens [

7]. This paper seeks to outline current approaches and guidelines to the classification and subsequent treatment of ALL in adults, synthesizing findings from recent studies to examine the efficacy of current treatment modalities. By doing so, we hope to highlight advances and ongoing challenges, with a specific focus on emerging therapies and treatment paradigms that have shown promise in the refractory or relapsed setting and may soon be introduced as frontline therapy.

2. Fit Older Adults

In medically fit older adults with ALL, treatment plans are highly individualized, as there is no standard chemotherapy regimen. Initial management often includes leukoreduction with steroids, with possible addition of cyclophosphamide or vincristine. Anthracyclines are typically avoided in this population due to their association with increased mortality, and asparaginase is also excluded for similar reasons. In the United States, a modified regimen known as Mini HCVD (consisting of dose-reduced cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone, cytarabine and methotrexate) is commonly used for B-cell ALL. In Europe, a mini version of the pediatric Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster (BFM) -based chemotherapy is employed. Both approaches have demonstrated complete remission (CR) rates of 70-80%, but they also present significant drawbacks. The mortality rate during induction therapy ranges from 10-20%, with a higher risk for those aged over 75 years, where it can approach 40%. Even among those achieving CR, the overall mortality rate remains around 30-40% [

8].

The conclusion from these approaches is that chemotherapy serves best as a backbone to more targeted therapies. While rituximab shows benefits in younger adults, it is less effective in older adults due to increased risks of infection complications. Inotuzumab-ozogamicin, an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC), first showed efficacy against relapsed/refractory B-cell -ALL in adults in the phase III INO-VATE trial. This led to increasing interest in incorporating this medication to the front-line setting [

9].

In the first-line setting, early data from a study combining mini HCVD with inotuzumab-ozogamicin followed by three years of 6-mercaptopurine, vincristine, methotrexate and prednisone (POMP) consolidation (compared to chemotherapy alone) in adults over 60 years old suggested favorable outcomes. The relapse-free survival (RFS) at three years was 49%, and overall survival (OS) was 56%, which compared favorably to historical data. Although high mortality during CR induction (about 25%) was observed, 85% of patients achieved CR. However, there was a high incidence of veno-occlusive disease (VOD) from inotuzumab, which led to dose reductions in this drug. One study in 2022 with older adults with Ph-negative ALL receiving inotuzumab-ozogamicin, mini HCVD, and/or blinatumomab consolidation (a bi-specific CD19 and CD3 antibody) showed even higher CR rates (98% vs 88%), with fewer early deaths (0-8%), and a decrease in deaths in patients with CR (5-17%). Despite this, significant toxicity prompted protocol amendments, including reducing induction cycles from four to two and replacing POMP with blinatumomab consolidation for adults over 70 years old. The results showed superior RFS at 64% versus 34%, and OS at 63% versus 34%. However, it is important to note that this approach is still not approved for first-line use outside of clinical trials [

9,

10].

Recent updates on inotuzumab-ozogamicin in first-line therapy show promising results. A phase 2 study combining HyperCVAD with blinatumomab and POMP consolidation, with the addition of inotuzumab-ozogamicin during induction, showed excellent outcomes in patients under 60 years. At the three-year follow-up, 100% of patients achieved CR, and 91% were minimal residual disease (MRD) -negative after one cycle. The OS was 84%, with only 10% of patients relapsing. The treatment was well-tolerated, with no evidence of VOD. The safety profile was generally favorable, with only one patient discontinuing blinatumomab due to grade 2 encephalopathy [

9,

10].

The main challenge in treatment is not inducing CR but maintaining it, as chemotherapy alone has proven ineffective in sustaining long-term response. Blinatumomab has shown efficacy in relapsed/refractory B-cell ALL and MRD-positive disease in CR, although it is not yet approved for first-line use. Blinatumomab has proven effective in maintaining MRD-negative status in older adults, achieving similar results to younger adults. The primary adverse events are cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), with these being more severe in older adults [

11].

The SWOG study 1318, a phase II trial treating newly diagnosed Ph-negative B cell-ALL in adults over 65, used blinatumomab monotherapy for induction and POMP maintenance. An interim analysis at one year showed a CR rate of 66% and an EFS of 56%. Ongoing trials are exploring the combination of inotuzumab-ozogamicin and blinatumomab in newly diagnosed and relapsed/refractory B-cell ALL in older adults [

8].

Blinatumomab has also demonstrated benefits in sustaining CR in MRD-negative patients. A phase III trial involving adults with MRD levels below 0.01% after induction and intensification chemotherapy showed superior OS at 43 months (85% vs 68%) for those receiving blinatumomab consolidation along with chemotherapy. The RFS was also superior (80% vs 64%). However, neuropsychiatric symptoms were more common in the treatment group. As a result of these findings, blinatumomab was recently approved for use in adult patients with Ph-negative ALL who are in first CR with MRD-negative status, defined as MRD levels below 0.01% [

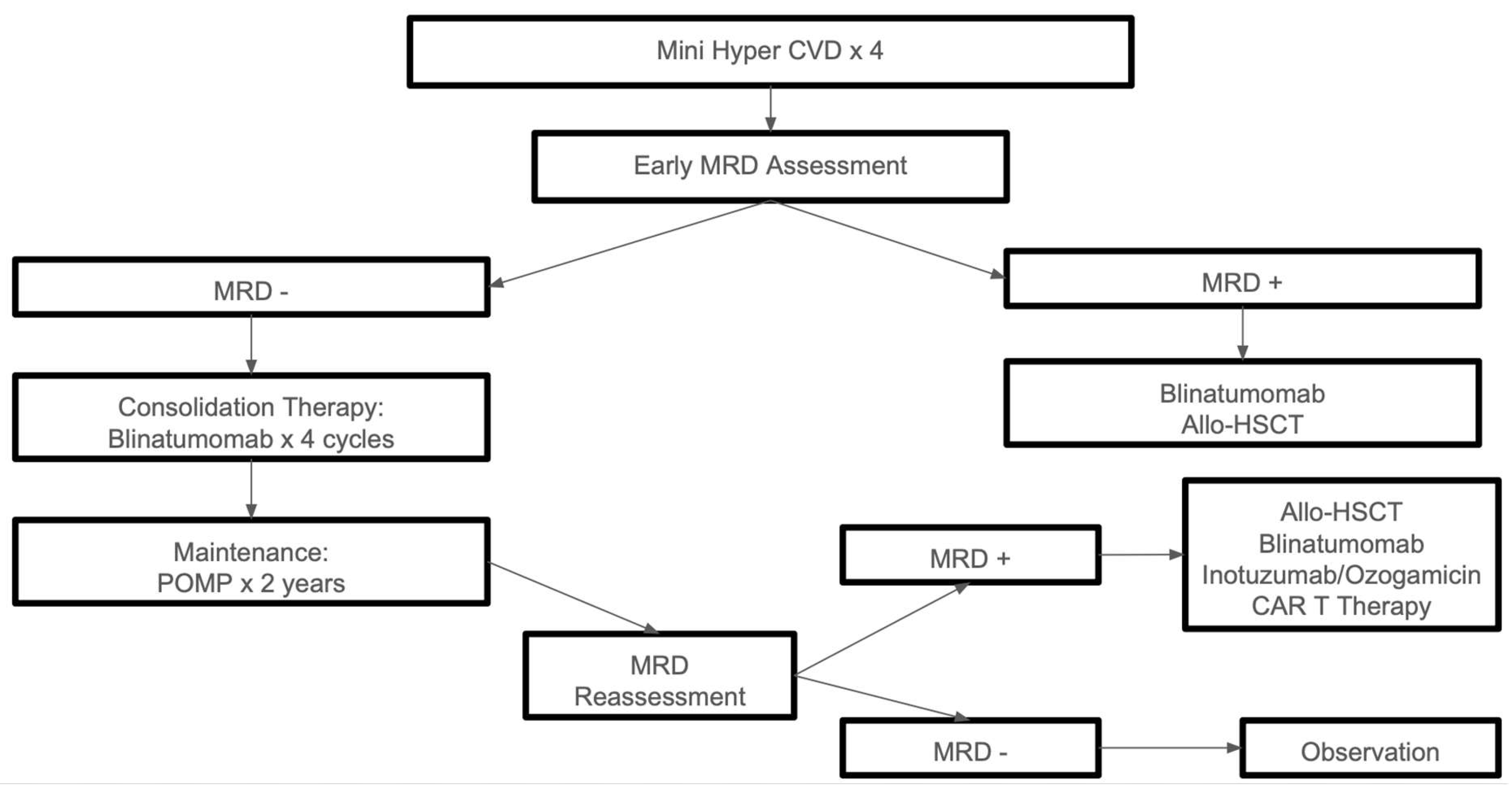

12]. An algorithmic approach to the treatment of disease in medically fit patients is summarized in

Figure 1.

3. Unfit Older Adults

For older adults who are not fit for intensive therapy, there is no standard treatment approach, particularly for those over 75 years of age or who are frail. In such cases, palliative chemotherapy is often considered, with options including the use of steroids and vincristine. Additionally, POMP chemotherapy can be considered as a treatment option, depending on the patient’s overall health and ability to tolerate therapy [

8].

There is some data from small studies that provides optimism towards non-chemotherapy alternatives to treat this patient population and achieve meaningful responses and survival benefits, with relatively acceptable toxicity profiles. One report with a small number of B-cell ALL cases in elderly patients over 70 years old evaluated the efficacy of a minimized regimen consisting only of Inotuzumab/Ozogamicin and Blinatumomab with an induction backbone of dexamethasone and vincristine. Out of the 14 patients that were enrolled, 13 achieved a complete response after one cycle, and after 2 cycles of treatment all 13 responders were MRD negative by flow cytometry; 12 responders had MRD evaluated with NGS as well, and 11 of them were MRD negative at a sensitivity of 10

-6. Moreover, at a median follow up of 15 months, the 1-year rate for RFS was 64%, for objective response (OR) it was 70%, and for OS it was 73%; median was not reached for any of these parameters at the time. 5 patients had died, 3 of them in remission from pneumonia, MI and respiratory failure (none of them from neutropenia), the other 2 died after relapse, one of them had a KMT2A mutation and the other one had hypoploidy plus TP53 mutation. There was one patient who developed grade 3 encephalopathy during treatment with Blinatumomab that resolved with steroids and blinatumomab was able to be reintroduced later on; there were no cases of VOD, but all patients were pre-treated with ursodeoxycolic acid. Despite this good adverse event profile, most patients did have grade 1-2 encephalopathy during treatment with blinatumomab [

13].

There is another small case series report of 9 elderly patients with relapsed/refractary pre-B cell ALL, including patients with Ph+ status, who received treatment with Inotuzumab-Ozogamicin monotherapy, all patients included were CD22+ at the time of beginning treatment. Out of the 9 patients only 6 could be assessed for disease response (two were selected for CAR T cell harvesting, and one patient died of sepsis complications); of the 6 patients, 5 achieved complete response, three of which achieved MRD negative status [

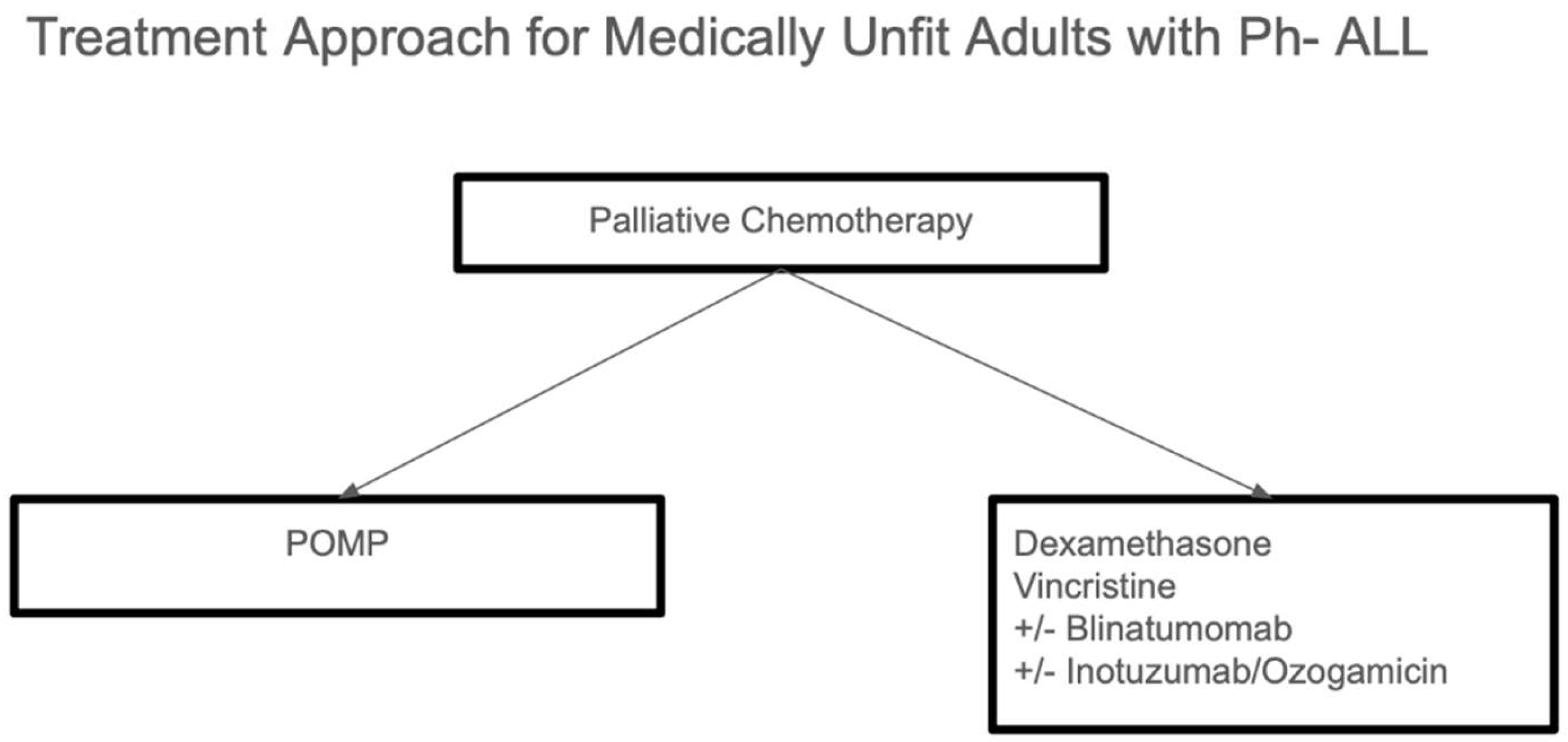

14]. Treatment of older adults who are not fit for intensive therapy is summarized in

Figure 2.

3. Central Nervous System Directed Therapy

Central nervous system (CNS)-directed therapy is crucial for managing adult ALL and preventing CNS relapse. When there are more than five white blood cells (WBCs) per microliter in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with the presence of blasts, it indicates CNS involvement. Historically, patients with traumatic lumbar puncture (LP) have been at higher risk for CNS relapse and poor event-free survival (EFS), as this procedure may theoretically

“seed

” the CNS with leukemia cells [

8,

15].

3.1. Central Nervous System Prophylaxis

For prophylaxis, intrathecal (IT) chemotherapy combined with intracranial radiation therapy (XRT) has been the standard of care for many years. This combination was proven in a phase III trial to reduce the rate of CNS relapse at two years to 19%, compared to 42% in the control group that did not receive CNS prophylaxis. However, the use of intracranial XRT has notable side effects, including seizures, cognitive deficits, and growth stunting. In adults, the combination of XRT with chemotherapy can lead to unacceptable myelotoxicity and other toxicities, making it difficult to proceed with timely consolidation therapy. As a result, the newer standard of care for most patients has shifted to a combination of IT chemotherapy and systemic chemotherapy, which includes high-dose methotrexate (MTX) and cytosine arabinoside, replacing XRT. Studies in adults show that this combination results in CNS relapse rates of approximately 5%. Although no single IT chemotherapy regimen is universally accepted, combinations of MTX, cytarabine, and glucocorticoids (Gc) have been used. While this combination may prolong CNS EFS, evidence suggests it does not significantly improve overall survival (OS). XRT may still be included in some protocols for high-risk patients, such as those with WBC counts greater than 100,000 or T-cell leukemia, although evidence from two meta-analyses does not support its use, as the risk for CNS relapse was not reduced in the XRT-treated groups [

15].

3.2. Central Nervous System Treatment

When CNS leukemia is detected, treatment should include IT triple therapy (a combination of chemotherapy agents) 2-3 times a week until no blasts are detectable in the CSF. This treatment is typically combined with systemic therapy, which includes high-dose methotrexate, high-dose asparaginase, and dexamethasone. Several risk factors contribute to the likelihood of CNS leukemia, including mature B-cell and T-cell ALL, elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels greater than 600, a high proliferative index at diagnosis (more than 14% of lymphoblasts in the S and G2/M phases), and high-risk cytogenetics such as KMT2A, NPM1, or Ph-positive ALL [

8,

15].

4. MRD-Based Treatment Modification

MRD-based prognostication is a critical component in the management of ALL and involves several key factors. The threshold for minimal residual disease (MRD) is typically set at <0.01%, as this aligns with the sensitivity of MRD detection methods. This threshold is important because it helps predict the time to hematological relapse. Patients with higher MRD levels are more likely to relapse sooner and may be candidates for MRD-based therapies. The timing of MRD testing also plays a significant role in its prognostic value. If MRD is tested during induction, a negative result is a good indicator of favorable outcomes and may even allow for treatment de-escalation. On the other hand, testing after the first consolidation is often considered the best time to assess the risk of relapse and to determine if a patient may benefit from a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) [

16].

The method of MRD measurement is another important consideration. Multiple PCR-based techniques can be used, as long as the laboratory has experience with methods like clonal immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor measurement. For MRD measurement to impact treatment decisions, it must have a minimum sensitivity of 0.01% detection. This sensitivity ensures that MRD findings are accurate enough to guide clinical choices [

17].

Current uses of MRD detection include determining eligibility for stem cell transplantation (SCT). Patients with persistent MRD are generally considered good candidates for SCT, as it has been shown to offer a survival benefit. However, higher MRD levels are associated with an increased chance of relapse after SCT and more difficulty achieving complete remission (CR1) prior to transplantation. In general, patients with MRD levels greater than 0.1% after three cycles of standard therapy should be considered for SCT or targeted therapies. This approach has demonstrated a survival benefit, as previously indicated in various studies [

18].

Early modification of treatment based on MRD findings is also crucial. Blinatumomab has proven to be effective in inducing remission and prolonging survival in adult ALL patients with MRD levels greater than 0.1%. A single-arm study conducted in 2018 demonstrated that patients in both first and later remissions could benefit from blinatumomab before proceeding to SCT. In this study, 78% of patients achieved complete molecular response (CMR) after just one cycle of blinatumomab. Achieving CMR was associated with significantly longer relapse-free survival (23.6 months vs. 5.7 months) and overall survival (OS) (38.9 months vs. 12.5 months). The median OS for all patients who had hematological response (including those with MRD -positive status) was 36.5 months, compared to only 6 months for those who did not have at least hematological response. Additionally, 67% of these patients went on to receive SCT, with a low relapse rate after the procedure. However, it is noteworthy that all patients who did not undergo SCT eventually relapsed, highlighting the importance of early treatment modification based on MRD results [

17,

18].

5. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant in Adults

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) remains the only curative option for adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) due to the high risk of eventual relapse. However, the evolving role of minimal residual disease (MRD) in predicting disease relapse is reshaping the indications for HSCT. While HSCT remains indicated in most cases with high-risk features, such as KMT2A rearrangements or t(4;11) translocations and Ph-positive disease, the criteria for transplantation have become more nuanced. Subtypes that were previously considered clear indications for HSCT, such as low hypoploidy, complex karyotypes, early T-cell precursor ALL (ETP-ALL), and Ph-like ALL, now present conflicting evidence regarding their survival benefit. The development of new treatment options, including blinatumomab and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapies, has provided alternative strategies with less treatment-related mortality (TRM), challenging the historical reliance on HSCT [

19,

20,

21].

MRD is increasingly being incorporated into decisions about HSCT. In younger adults, particularly those treated under adolescent and young adult (AYA) protocols, 5-year survival rates range from 60-70%, and these patients may be spared from HSCT if they achieve MRD negativity. On the other hand, patients considered to be at standard risk who have MRD positivity (greater than 0.01%) after three cycles of standard therapy should be considered for HSCT or targeted therapies, as this indicates a higher risk of relapse. Even patients who achieve MRD-negative status after maintenance therapy still face a 20-30% chance of hematological relapse, emphasizing the importance of frequent MRD monitoring in this patient population. However, the challenges of frequent MRD measurement include technical limitations and resource constraints, as well as the lack of a standardized MRD testing method [

8,

19].

HSCT remains a viable option for older adults, despite poor outcomes with non-transplant strategies. The primary challenge in this age group is treatment-related mortality (TRM). Reduced-intensity chemotherapy (RIC) regimens have shown similar overall survival (OS) outcomes to myeloablative regimens, offering the advantage of reduced TRM, although they may lead to higher relapse rates. A 2017 review by the Acute Leukemia Working Party (ALWP) of the European Bone Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) group evaluated the effects of HSCT at first complete remission (CR1) using RIC in older adults, regardless of Philadelphia chromosome (Ph) status. In this cohort, with a median age of 62 years, the 3-year OS was 42%, and event-free survival (EFS) was 35%. The most significant negative impact on OS was observed with cytomegalovirus (CMV) donor-recipient mismatch, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) was more common in patients with unrelated donors. These findings underscore the complexities of HSCT in older adults and the need for tailored treatment strategies to optimize outcomes [

22].

6. Treatment of Relapsed Disease

The treatment of relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) continues to be a challenging area, with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) remaining the only curative option for patients who experience relapse. Relapses can occur either in the bone marrow or as extramedullary (EM) disease. EM disease relapse is particularly concerning, as it is associated with a worse prognosis. A clue to the presence of EM disease can be a positive minimal residual disease (MRD) result in the peripheral blood, even when the bone marrow is negative for MRD. For relapses that occur more than 18 months after the first complete remission (CR) (late relapses), the treatment approach typically involves repeating the initial induction regimen. This may include high-dose cytarabine (HiDAC) combined with anthracyclines or mithoxantrone, or FLAG-Ida, a regimen involving fludarabine, high-dose cytarabine, filgrastim, and idarubicin. High-dose methotrexate and high-dose cytarabine (Ara-C) are also options for these cases. For second or subsequent relapses, where the aim is not curative, liposomal vincristine is an approved treatment. Relapsed T-cell ALL requires a different approach, and nelarabine has shown promising results in this setting. It has demonstrated a 41% complete remission (CR) rate with a median CR duration of 3 months, although the overall survival (OS) remains limited, with 1-year survival at 28% and 3-year survival at 11% [

23,

24].

Immuno-oncology agents have emerged as a promising area of treatment for relapsed disease, although there is currently no standard-of-care (SOC) for their use, particularly due to overlapping indications. The evidence available for these therapies in first-line treatment, relapsed disease, and even MRD-negative disease is encouraging. However, these therapies are currently approved only for B-cell ALL. For T-cell ALL, the use of these agents is limited due to the risk of T-cell fratricide and immunosuppression, which makes their use unsuitable for this subtype [

8,

25].

6.1. Blinatumomab

As mentioned before, blinatumomab is approved for relapsed or refractory CD19-positive B-cell ALL. The TOWER trial was the first phase III trial to compare blinatumomab with chemotherapy in previously treated Ph-negative B-cell ALL. This trial showed a CR rate of 44% for blinatumomab compared to 25% for chemotherapy alone, with OS of 7 months versus 4.4 months. Factors that predicted poor response to blinatumomab included a low number of marrow blast cells, extramedullary disease, a high amount of circulating regulatory T cells (Tregs), and PD-L1 expression in B-cell blasts [

11].

As previously stated, given the short duration of response with blinatumomab, it is recommended that patients undergo HSCT as soon as possible after achieving CR, with blinatumomab serving as bridging therapy [

10,

17].

6.2. Inotuzumab-Ozogamicin

Inotuzumab-ozogamicin (IO), which targets CD22 and delivers the chemotherapy payload calicheamicin, is approved for relapsed or refractory B-cell ALL in adults. The phase III INO-VATE trial demonstrated that IO resulted in a higher CR rate compared to chemotherapy (80.7% versus 29.4%) and a higher MRD-negative rate (78.4% versus 28.1%). In survival analyses, IO showed superior progression-free survival (PFS) (5.0 months versus 1.8 months) and marginally superior OS. Notably, more patients in the IO group underwent allo-HSCT, and this subgroup experienced significant leukemia-free survival. However, a major concern with IO is VOD, which complicates the assessment of hepatotoxicity, especially in patients who undergo HSCT. Overall, serious adverse events and hematological side effects were less frequent with IO compared to chemotherapy. A post-hoc analysis comparing younger adults (<55 years) with older adults (>55 years) in the INO-VATE study showed similar CR rates (70% versus 75%) and MRD negativity (79% versus 76%) across age groups, with no significant difference in the incidence of SOS. These findings highlight the potential for IO as a treatment option in both younger and older adult populations with relapsed B-cell ALL [

10].

6.3. Chimeric Antigen Receptor-T Cells (CAR-T)

Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy has emerged as an exciting and promising treatment for relapsed or refractory (RR) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Initial approvals for CAR-T targeting CD19 were based on the ELIANA trial, which demonstrated efficacy in children and young adults. However, the safety and toxicity profile for adults remains under further investigation. A phase II study is being prepared to evaluate the use of CAR-T therapy in adults, with revisions to the toxicity profile underway [

26].

The ZUMA-3 trial, released in 2021, focused on adults with RR B-cell ALL, including those who had relapsed after stem cell transplantation (SCT). This multicenter phase II trial involved 71 patients, with 55 patients successfully receiving the treatment. The median age of the treated patients was 40 years, with 15% of patients over the age of 65. The results from this trial showed that 56% of treated patients achieved complete remission (CR), and 71% achieved CR with incomplete hematological recovery. The median duration of response was 12.8 months, with a median relapse-free survival (RFS) of 11.2 months. Despite these promising results, 20 patients died, mostly due to disease progression, with two deaths linked to grade 5 toxicities, including brain herniation and septic shock. A significant proportion of patients (approximately 24%) experienced grade 3 cytokine release syndrome (CRS) or immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), highlighting the need for ongoing monitoring of these side effects [

22,

27].

In 2023, long-term follow-up data from the ELIANA trial indicated a decline in the likelihood of maintaining RFS over time. While 81% of patients maintained CR at the 1-year mark, only 51% maintained RFS. The main cause of relapse was CAR-T cell depletion or the persistence of CD19 expression, which is why loss of CD19 expression on B-cells remains a significant concern. To address this, new developments in multi-target CAR-T cells are underway, including constructs that co-target CD19 and CD22. One of the largest studies to date on these dual-target CAR-T cells is a phase 1 trial for CD22 CAR-T cells in RR B-cell ALL patients who have relapsed after CD19-targeted CAR-T therapy. Early results show manageable toxicity and promising outcomes, although it remains too early to draw definitive conclusions. It is worth noting that targeting CD22 with CAR-T cells carries an increased risk of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) compared to CD19 therapy, though it appears to reduce the incidence of neurotoxicity and ICANS [

26,

28,

29].

6.4. Immuno-Oncology Agents for Extramedullary and CNS Disease

When considering the use of immuno-oncology agents for extramedullary (EM) or central nervous system (CNS) disease, it is important to note that antibody-based therapies like blinatumomab or inotuzumab-ozogamicin (IO) have poor blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration, limiting their effectiveness for these disease sites. These therapies must therefore be combined with intrathecal (IT) chemotherapy to address CNS or EM disease. On the other hand, CAR-T cells exhibit good CNS penetrance, making them a potentially effective option for patients with CNS disease burden. However, patients with a high CNS disease burden are at increased risk for neurotoxicity, which may negate the survival benefits of CAR-T therapy. The experience with CAR-T cells in CNS disease is still limited, with small studies and short follow-up periods. A meta-analysis supports the findings that CAR-T cells can effectively treat CNS involvement, but further research and data are needed to confirm their long-term efficacy and safety in this setting [

11,

30].

7. Ph+ ALL

Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL) is a genetically distinct and aggressive leukemia subtype with the presence of the BCR-ABL fusion gene. In this section, we will synthesize advancements in its treatment, focusing on the transformative role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), the integration of immunotherapy, and evolving strategies for adult populations [

31].

The introduction of TKIs has revolutionized the treatment of Ph+ ALL, targeting the BCR-ABL fusion protein’s tyrosine kinase activity. TKIs, such as imatinib, dasatinib, and ponatinib, have significantly improved outcomes by achieving remissions with reduced toxicity compared to traditional chemotherapy. Imatinib, when combined with low-intensity chemotherapy, demonstrated high remission rates and is the primary treatment for younger patients. Ponatinib, noted for its efficacy against T315I mutation, remains a critical option for resistant cases or relapse. The combination of TKIs with immunotherapies, such as blinatumomab (a bispecific T-cell engager targeting CD19), is now being explored to reduce reliance on intensive chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation (SCT).[

31,

32] Recent advances suggest that integrating TKIs with immunotherapy or reduced-intensity chemotherapy achieves comparable outcomes to traditional regimens. For example, studies highlight the success of chemo-free regimens that pair TKIs with agents like blinatumomab, providing a pathway for treatment in older patients unfit for intensive therapies. Such approaches reduce treatment-related toxicities while maintaining excellent survival rates [

32,

33].

Allo-HSCT has been considered the standard for curing Ph+ ALL. However, the necessity of transplantation in the first complete remission is increasingly questioned with TKIs and immunotherapies. Currently, research undermines the minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring to guide decisions about transplant eligibility. Patients may forgo allo-HSCT, especially when treated with next-generation inhibitors like ponatinib or antibody-based therapies such as inotuzumab ozogamicin [

31,

33].

Immunotherapies, including blinatumomab and inotuzumab ozogamicin, are central to evolving Ph+ ALL management. These agents enable chemo-free regimens, particularly in patients unfit for transplantation or those with relapsed disease. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies targeting CD19 are under investigation, offering a promising option. Furthermore, next-generation precision medicine are paving the way for personalized treatment approaches by identifying resistance mutations and tailoring therapies [

34].

Ph+ ALL with p190 mutation, for example, is a distinct subtype of ALL characterized by the presence of BCR-ABL1 fusion gene and the production of tyrosine kinase p190 BCR-ABL1 oncoprotein. Other BCR-ABL1 fusion chimeric proteins include p210 and p230. The mutation is typically associated with a more aggressive disease course, and is a poor prognostic marker, however the advent of TKIs has significantly improved outcomes for this subtype. The poor prognosis historically associated with Ph+ ALL has dramatically shifted with the use of TKIs as response rates to first line therapies are now more closely resembling Ph- disease [

35].

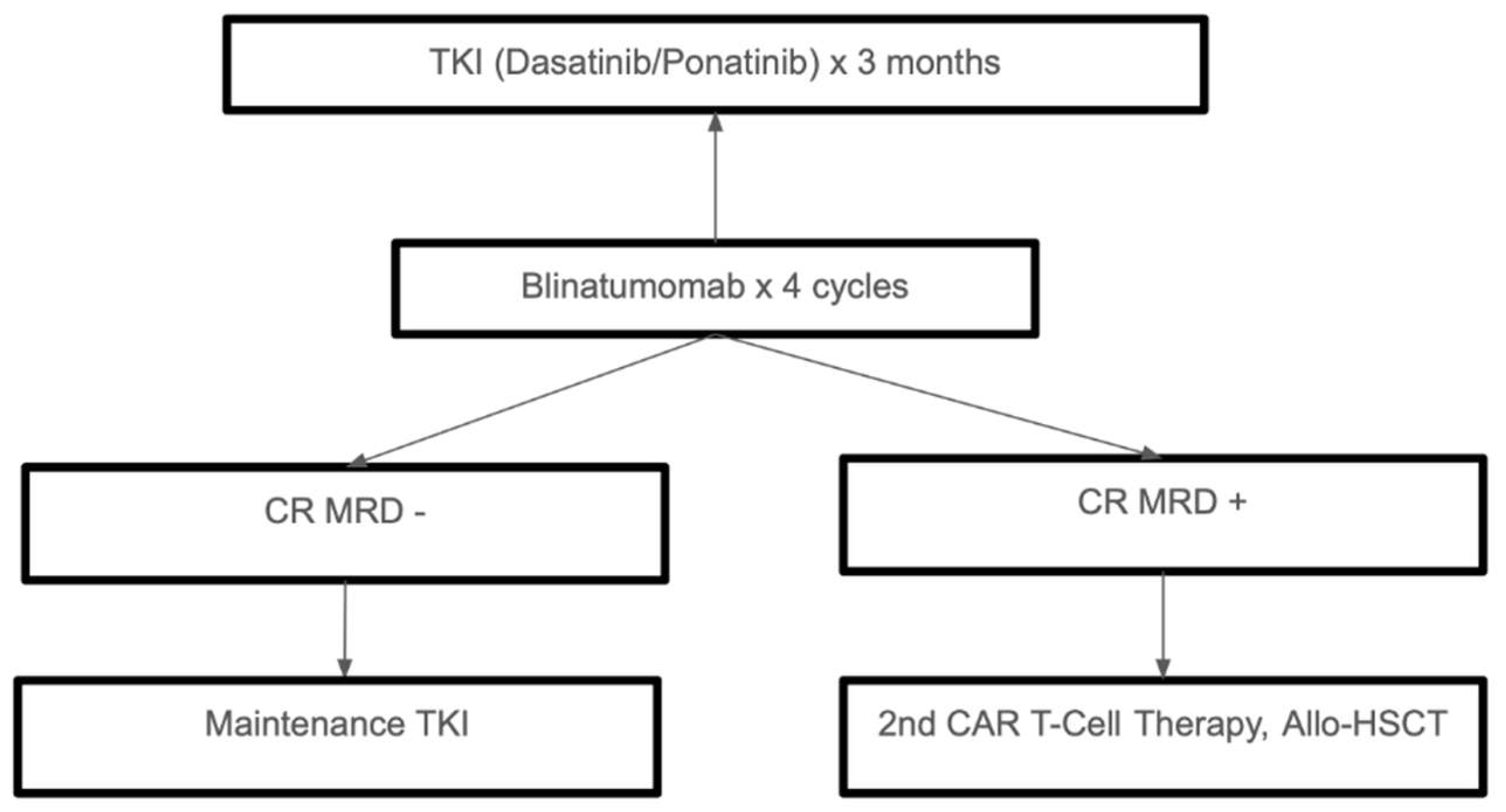

The development of TKIs, immunotherapy, and precision medicine has significantly changed the treatment landscape for Ph+ ALL. While TKI-based approaches and chemo-free regimens are changing the standards of care, allo-HSCT is still an option for high-risk or relapsed cases. Future studies should keep improving these strategies to guarantee the best results with the least amount of treatment-related side effects for all types of patients. Treatment of Ph+ ALL is summarized in

Figure 3.

7. Ph-like ALL

One subset of patients not included above is patients afflicted with Philadelphia chromosome-like (Ph-like) ALL. Patients with the disease are denoted as such given a genetic expression profile resembling Ph+ ALL, however, no BCR-ABL1 fusion gene is observed in this high risk subtype defined by genetic changes leading to aberrant kinase signaling [

36].

Instead, PH-like ALL are characterized by alternative genetic mutations. One subclass, for example, are ABL-class fusions, involving genes such as CSF1R, PDGFRB, ABL1, and ABL2. The aforementioned fusions often mimic the typical BCR-ABL1 fusion noted in Ph+ ALL. Other common mutations include alterations in CLFR2 alterations or the Jak-STAT pathway [

37].

Patients with Ph-like ALL have a significantly worse prognosis, with various studies demonstrating a 5-year overall survival of approximately 23% [

38]. The worse overall and event free survival can be attributed to persistent MRD, and higher rates of induction failure and relapse [

39].

In regards to treatment, similar to above, a key emerging area of focus is on personalized molecular targeting agents. Next generation sequencing can uncover specific driver mutations that are amenable to therapy, such as the use of TKIs in patients exhibiting ABL-class mutations. TKIs are pivotal in treating Ph-like ALL by targeting dysregulated signaling pathways. For example, dasatinib and ruxolitinib have shown efficacy in managing BCR-ABL1-like and JAK/STAT pathway abnormalities, respectively. Their integration into combination regimens with traditional chemotherapy significantly improves outcomes, as highlighted in studies focusing on pediatric and young adult populations [

40,

41].

Furthermore, data suggest that TKIs may address persistent minimal residual disease (MRD), a frequent complication associated with poor survival in this subtype [

38,

39].

Given the advent of such molecular testing is relatively new, a standard of care approach to the treatment of Ph-like ALL has yet to be delineated. JAK inhibitors have also shown promise in preclinical studies and case series for patients with CRLF2/JAK pathway mutations, and multiple clinical trials in this area are ongoing. The combination of these targeted therapies with chemotherapy is another area of ongoing research and promise [

40,

42].

Emerging immunotherapies, including monoclonal antibodies and CAR-T cell therapies, offer promising options for refractory or relapsed cases such as Blinatumomab, which is a bispecific T-cell engager targeting CD19, has demonstrated efficacy in inducing remission among relapsed Ph-like ALL cases.[

7,

36] Inotuzumab Ozogamicin, an antibody-drug conjugate that targets CD22, has been proven to be effective in cases unresponsive to conventional therapies [

7,

40]. While it is still under investigation, CAR-T Cell, CD19-directed CAR-T therapies show potential in overcoming resistance, particularly for patients with relapsed or refractory disease [

7,

36]. CAR T-cell therapy has demonstrated remission rates up to 90% in heavily pretreated patients with Ph-like disease.

Despite advances, treatment outcomes for Ph-like ALL remain inferior compared to other ALL subtypes. Persistent MRD, noted in trials such as GIMEMA LAL1913, highlights the need for intensified or novel therapies.[

39] Additionally, the genetic heterogeneity of Ph-like ALL complicates standardized treatment. Comprehensive molecular profiling is essential for tailoring therapy to specific alterations, such as CRLF2 rearrangements or ABL-class fusions [

38,

41].

Some things can be done to overcome these challenges. Enhanced molecular diagnostics would allow for broader access to advanced diagnostic tools which will enable earlier detection and personalized treatment.[

36,

38] Further development of TKIs and monoclonal antibodies is critical to expanding treatment options for diverse genetic subtypes [

40]. Researching more on CAR-T cells and bispecific antibodies may redefine outcomes for relapsed or refractory Ph-like ALL.[

7,

36] Finally, figuring out solutions to some critical global disparities can ensure the availability of cutting-edge therapies in environments that have limited resources [

38,

39].

Overall, while significant progress has been made in treating Ph-like ALL, particularly through TKIs and immunotherapies, challenges such as MRD persistence and genetic diversity remain. Continued research and innovation are essential to improve survival and quality of life for patients with this high-risk leukemia subtype.

7. Conclusions

As the prognosis for ALL in adults remains unsatisfactory when compared to pediatric populations, novel therapeutics targeting specific biomarkers are being increasingly used in the relapsed or refractory setting. Using these therapies in the frontline setting is an emerging area of much promise. In particular, frontline integration of immuno-oncology agents such as bispecific T cell engagers and antibody-drug conjugates is an exciting prospect in regards to maintaining or improving outcomes and efficacy while also minimizing toxicity; future research should be directed towards this area.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.B; resources, S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, O.S, S.P. Z.M.; writing—review and editing, J.B.; supervision, J.B.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Brown PA, Shah B, Advani A, Aoun P, Boyer MW, Burke PW, DeAngelo DJ, Dinner S, Fathi AT, Gauthier J, Jain N, Kirby S, Liedtke M, Litzow M, Logan A, Luger S, Maness LJ, Massaro S, Mattison RJ, May W, Oluwole O, Park J, Przespolewski A, Rangaraju S, Rubnitz JE, Uy GL, Vusirikala M, Wieduwilt M, Lynn B, Berardi RA, Freedman-Cass DA, Campbell M. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. JNCCN. 2021, 19, 1079–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagliaro L, Chen SJ, Herranz D, Mecucci C, Harrison CJ, Mullighan CG, Zhang M, Chen Z, Boissel N, Winter SS, Roti G. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer. 2024, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunger SP, Mullighan CG. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1541–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malard F, Mohty M. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2020, 395, 1146–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansagra A, Dahiya S, Litzow M. Continuing challenges and current issues in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2018, 59, 526–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravandi, F. How I treat Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2019, 133, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinner S, Liedtke M. Antibody-based therapies in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program. 2018, 2018, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökbuget N, Boissel N, Chiaretti S, Dombret H, Doubek M, Fielding A, Foà R, Giebel S, Hoelzer D, Hunault M, Marks DI, Martinelli G, Ottmann O, Rijneveld A, Rousselot P, Ribera J, Bassan R. Diagnosis, prognostic factors, and assessment of ALL in adults: 2024 ELN recommendations from a European expert panel. Blood. 2024, 143, 1891–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarjian HM, DeAngelo DJ, Stelljes M, Martinelli G, Liedtke M, Stock W, Gökbuget N, O’Brien S, Wang K, Wang T, Paccagnella ML, Sleight B, Vandendries E, Advani AS. Inotuzumab Ozogamicin versus Standard Therapy for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 740–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short N, Jabbour E, Ravandi F, Yilmaz M, Kadia TM, Thompson PA, Huang X, Konopleva M, Ferrajoli A, Jain N, Sasaki K, Macaron W, Alvarado Y, Borthakur G, DiNardo CD, Ohanian M, Kornblau SM, Zhao M, Kwari M, Thankachan J, Loiselle C, Delumpa R, Garris R, Kantarjian H. The Addition of Inotuzumab Ozogamicin to Hyper-CVAD Plus Blinatumomab Further Improves Outcomes in Patients with Newly Diagnosed B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Updated Results from a Phase II Study. Blood. 2022, 140, 8966–8968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarjian H, Stein A, Gökbuget N, Fielding AK, Schuh AC, Ribera JM, Wei A, Dombret H, Foà R, Bassan R, Arslan Ö, Sanz MA, Bergeron J, Demirkan F, Lech-Maranda E, Rambaldi A, Thomas X, Horst HA, Brüggemann M, Klapper W, Wood BL, Fleishman A, Nagorsen D, Holland C, Zimmerman Z, Topp MS. Blinatumomab versus Chemotherapy for Advanced Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 836–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litzow MR, Sun Z, Mattison RJ, Paietta EM, Roberts KG, Zhang Y, Racevskis J, Lazarus HM, Rowe JM, Arber DA, Wieduwilt MJ, Liedtke M, Bergeron J, Wood BL, Zhao Y, Wu G, Chang TC, Zhang W, Pratz KW, Dinner SN, Frey N, Gore SD, Bhatnagar B, Atallah EL, Uy GL, Jeyakumar D, Lin TL, Willman CL, DeAngelo DJ, Patel SB, Elliott MA, Advani AS, Tzachanis D, Vachhani P, Bhave RR, Sharon E, Little RF, Erba HP, Stone RM, Luger SM, Mullighan CG, Tallman MS. Blinatumomab for MRD-Negative Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafaeli N, Marin D, Ledesma C, Jain N, Tewari P, Khouri IF, Olson AL, Alatrash G, Short NJ, Jabbour E, Rezvani K, Alousi AM, Popat U, Champlin RE, Shpall EJ, Kebriaei P. Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Following CAR T Therapy in Relapsed/Refractory Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Blood. 2810.

- Lin Y, Liu D, Xia Y, Wu T, Tong C. The Safety and Efficacy of Inotuzumab Treatment for Elderly Unfit r/r B ALL. Blood. 5891.

- Rives, S. Central nervous system therapy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: no more, no less. Haematologica. 2023, 108, 3193–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüggemann M, Raff T, Flohr T, Gökbuget N, Nakao M, Droese J, Lüschen S, Pott C, Ritgen M, Scheuring U, Horst HA, Thiel E, Hoelzer D, Bartram CR, Kneba M, German Multicenter Study Group for Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease quantification in adult patients with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2006, 107, 1116–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökbuget N, Dombret H, Bonifacio M, Reichle A, Graux C, Faul C, Diedrich H, Topp MS, Brüggemann M, Horst HA, Havelange V, Stieglmaier J, Wessels H, Haddad V, Benjamin JE, Zugmaier G, Nagorsen D, Bargou RC. Blinatumomab for minimal residual disease in adults with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2018, 131, 1522–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökbuget N, Zugmaier G, Dombret H, Stein A, Bonifacio M, Graux C, Faul C, Brüggemann M, Taylor K, Mergen N, Reichle A, Horst HA, Havelange V, Topp MS, Bargou RC. Curative outcomes following blinatumomab in adults with minimal residual disease B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2020, 61, 2665–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribera JM, Morgades M, Ciudad J, Montesinos P, Esteve J, Genescà E, Barba P, Ribera J, García-Cadenas I, Moreno MJ, Martínez-Carballeira D, Torrent A, Martínez-Sánchez P, Monsalvo S, Gil C, Tormo M, Artola MT, Cervera M, González-Campos J, Rodríguez C, Bermúdez A, Novo A, Soria B, Coll R, Amigo ML, López-Martínez A, Fernández-Martín R, Serrano J, Mercadal S, Cladera A, Giménez-Conca A, Peñarrubia MJ, Abella E, Vall-Llovera F, Hernández-Rivas JM, Garcia-Guiñon A, Bergua JM, de Rueda B, Sánchez-Sánchez MJ, Serrano A, Calbacho M, Alonso N, Méndez-Sánchez JÁ, García-Boyero R, Olivares M, Barrena S, Zamora L, Granada I, Lhermitte L, Feliu E, Orfao A. Chemotherapy or allogeneic transplantation in high-risk Philadelphia chromosome-negative adult lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2021, 137, 1879–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura S, Mullighan CG. Molecular markers in ALL: Clinical implications. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2020, 33, 101193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökbuget N, Kneba M, Raff T, Trautmann H, Bartram CR, Arnold R, Fietkau R, Freund M, Ganser A, Ludwig WD, Maschmeyer G, Rieder H, Schwartz S, Serve H, Thiel E, Brüggemann M, Hoelzer D, German Multicenter Study Group for Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and molecular failure display a poor prognosis and are candidates for stem cell transplantation and targeted therapies. Blood. 2012, 120, 1868–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth-Guepin G, Canaani J, Ruggeri A, Labopin M, Finke J, Cornelissen JJ, Delage J, Stuhler G, Rovira M, Potter M, Stadler M, Veelken H, Cahn JY, Collin M, Beguin Y, Giebel S, Nagler A, Mohty M. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation in acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients older than 60 years: a survey from the acute leukemia working party of EBMT. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 112972–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimony S, DeAngelo DJ, Luskin MR. Nelarabine: when and how to use in the treatment of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzieri DA, Leonard J, Badar T, Chen FL, Shah BD, Li Z. Trial in Progress: A Phase 2 Single Arm, Multicenter Trial to Evaluate the Efficacy of the BiTE ® Antibody Blinatumomab (Blincyto) and Vincristine Sulfate Liposomal Injection (Marqibo) in Adult Subjects with Relapsed/Refractory Philadelphia Negative CD19+ Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Blood. 2021, 138, 4404. [Google Scholar]

- Bayón-Calderón F, Toribio ML, González-García S. Facts and Challenges in Immunotherapy for T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Buechner J, Rives S, Boyer M, Bittencourt H, Bader P, Verneris MR, Stefanski HE, Myers GD, Qayed M, De Moerloose B, Hiramatsu H, Schlis K, Davis KL, Martin PL, Nemecek ER, Yanik GA, Peters C, Baruchel A, Boissel N, Mechinaud F, Balduzzi A, Krueger J, June CH, Levine BL, Wood P, Taran T, Leung M, Mueller KT, Zhang Y, Sen K, Lebwohl D, Pulsipher MA, Grupp SA. Tisagenlecleucel in Children and Young Adults with B-Cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah BD, Ghobadi A, Oluwole OO, Logan AC, Boissel N, Cassaday RD, Leguay T, Bishop MR, Topp MS, Tzachanis D, O’Dwyer KM, Arellano ML, Lin Y, Baer MR, Schiller GJ, Park JH, Subklewe M, Abedi M, Minnema MC, Wierda WG, DeAngelo DJ, Stiff P, Jeyakumar D, Feng C, Dong J, Shen T, Milletti F, Rossi JM, Vezan R, Masouleh BK, Houot R. KTE-X19 for relapsed or refractory adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: phase 2 results of the single-arm, open-label, multicentre ZUMA-3 study. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2021, 398, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank MJ, Baird JH, Kramer AM, Srinagesh HK, Patel S, Brown AK, Oak JS, Younes SF, Natkunam Y, Hamilton MP, Su YJ, Agarwal N, Chinnasamy H, Egeler E, Mavroukakis S, Feldman SA, Sahaf B, Mackall CL, Muffly L, Miklos DB, CARdinal-22 Investigator group. CD22-directed CAR T-cell therapy for large B-cell lymphomas progressing after CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy: a dose-finding phase 1 study. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2024, 404, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel JY, Patel S, Muffly L, Hossain NM, Oak J, Baird JH, Frank MJ, Shiraz P, Sahaf B, Craig J, Iglesias M, Younes S, Natkunam Y, Ozawa MG, Yang E, Tamaresis J, Chinnasamy H, Ehlinger Z, Reynolds W, Lynn R, Rotiroti MC, Gkitsas N, Arai S, Johnston L, Lowsky R, Majzner RG, Meyer E, Negrin RS, Rezvani AR, Sidana S, Shizuru J, Weng WK, Mullins C, Jacob A, Kirsch I, Bazzano M, Zhou J, Mackay S, Bornheimer SJ, Schultz L, Ramakrishna S, Davis KL, Kong KA, Shah NN, Qin H, Fry T, Feldman S, Mackall CL, Miklos DB. CAR T cells with dual targeting of CD19 and CD22 in adult patients with recurrent or refractory B cell malignancies: a phase 1 trial. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1419–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy AB, Newman H, Li Y, Liu H, Myers R, DiNofia A, Dolan JG, Callahan C, Baniewicz D, Devine K, Wray L, Aplenc R, June CH, Grupp SA, Rheingold SR, Maude SL. CD19-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for CNS relapsed or refractory acute lymphocytic leukaemia: a post-hoc analysis of pooled data from five clinical trials. Lancet Haematol. 2021, 8, e711–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, AK. How I treat Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010, 116, 3409–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foà R, Chiaretti S. Philadelphia Chromosome-Positive Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 2399–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieduwilt, MJ. Ph+ ALL in 2022: is there an optimal approach? Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2022, 2022, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvaris R, Fedele PL. Targeted Therapy in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed AN, Patel M, Zureigat H, Nurse DP, Haddad SF, Zabor EC, Bedelu YB, Chen MJ, Nakitandwe J, Molina JC, Balderman S, Jain AG, Singh A, Mukherjee S, Gerds AT, Carraway HE, Advani AS, Mustafa Ali MK. Impact of P190 and P210 BCR::ABL1 Chimeric Protein on Outcomes of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia at a Tertiary Center. Blood. 2024, 144, 5909.

- Jain N, Roberts KG, Jabbour E, Patel K, Eterovic AK, Chen K, Zweidler-McKay P, Lu X, Fawcett G, Wang SA, Konoplev S, Harvey RC, Chen IM, Payne-Turner D, Valentine M, Thomas D, Garcia-Manero G, Ravandi F, Cortes J, Kornblau S, O’Brien S, Pierce S, Jorgensen J, Shaw KRM, Willman CL, Mullighan CG, Kantarjian H, Konopleva M. Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a high-risk subtype in adults. Blood. 2017, 129, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts KG, Reshmi SC, Harvey RC, Chen IM, Patel K, Stonerock E, Jenkins H, Dai Y, Valentine M, Gu Z, Zhao Y, Zhang J, Payne-Turner D, Devidas M, Heerema NA, Carroll AJ, Raetz EA, Borowitz MJ, Wood BL, Mattano LA, Maloney KW, Carroll WL, Loh ML, Willman CL, Gastier-Foster JM, Mullighan CG, Hunger SP. Genomic and outcome analyses of Ph-like ALL in NCI standard-risk patients: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Blood. 2018, 132, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts KG, Gu Z, Payne-Turner D, McCastlain K, Harvey RC, Chen IM, Pei D, Iacobucci I, Valentine M, Pounds SB, Shi L, Li Y, Zhang J, Cheng C, Rambaldi A, Tosi M, Spinelli O, Radich JP, Minden MD, Rowe JM, Luger S, Litzow MR, Tallman MS, Wiernik PH, Bhatia R, Aldoss I, Kohlschmidt J, Mrózek K, Marcucci G, Bloomfield CD, Stock W, Kornblau S, Kantarjian HM, Konopleva M, Paietta E, Willman CL, Mullighan CG. High Frequency and Poor Outcome of Philadelphia Chromosome-Like Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Adults. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaretti S, Messina M, Della Starza I, Piciocchi A, Cafforio L, Cavalli M, Taherinasab A, Ansuinelli M, Elia L, Albertini Petroni G, La Starza R, Canichella M, Lauretti A, Puzzolo MC, Pierini V, Santoro A, Spinelli O, Apicella V, Capria S, Di Raimondo F, De Fabritiis P, Papayannidis C, Candoni A, Cairoli R, Cerrano M, Fracchiolla N, Mattei D, Cattaneo C, Vitale A, Crea E, Fazi P, Mecucci C, Rambaldi A, Guarini A, Bassan R, Foà R. Philadelphia-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia is associated with minimal residual disease persistence and poor outcome. First report of the minimal residual disease-oriented GIMEMA LAL1913. Haematologica 2021, 106, 1559–1568. [Google Scholar]

- Tran TH, Tasian SK. How I Treat Philadelphia Chromosome-like Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults. Blood. 2023.

- Xu GF, Liu LM, Wang M, Zhang ZB, Xie JD, Qiu HY, Chen SN. Treatments of Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a real-world retrospective analysis from a single large center in China. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2022, 63, 2652–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldoss I, Advani AS. Have any strategies in Ph-like ALL been shown to be effective? Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2021, 34, 101242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).