Submitted:

26 December 2024

Posted:

27 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. What is a Antibiotic Stewardship Program (ASP) and a Diagnostic Stewardship Program (DSP)?

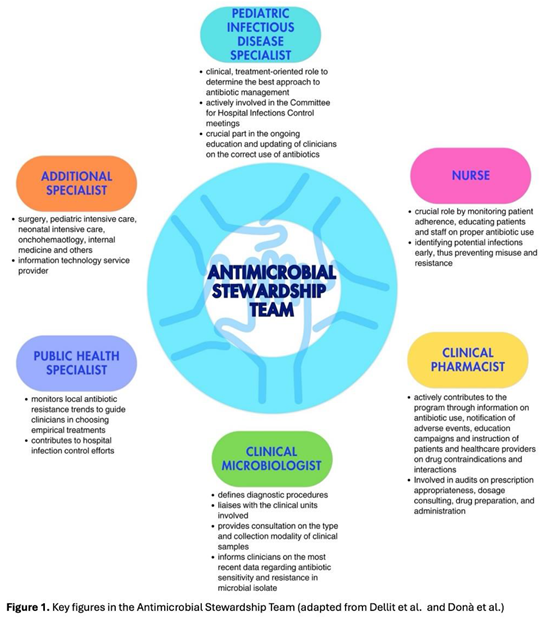

3. Which healthcare workers should be involved in an ASP? The Antimicrobial Stewardship Team

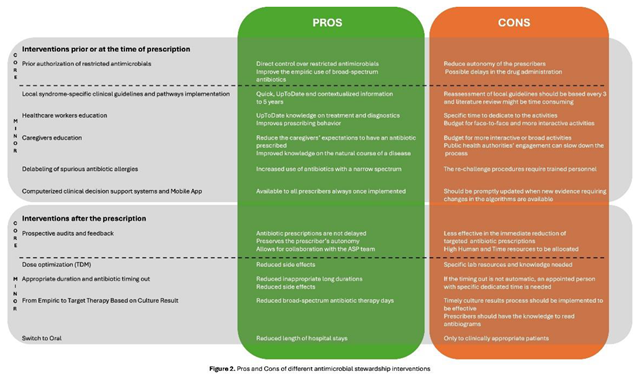

4. Different Types of ASP

4.1. What Interventions Are Effective Prior to or at the Time of Prescription?

4.1.1. Core Strategy

4.1.2. Minor Elements

4.2. What Interventions Are Effective After the Time of Prescription?

4.2.1. Core Strategy

4.2.2. Minor Elements

5. The Different Types of ASP: Does the Same Program Fit All the Settings?

5.1. Inpatient Pediatric Care

5.2. Primary Care Setting

5.3. Pediatric Emergency Departments

6. Different Types of Diagnostic Stewardship

7. The Different Types of Diagnostic Stewardship: Does the Same Program Fit All the Settings?

7.1. Inpatient Pediatric Care

7.2. Primary Care Settings

7.3. Pediatric Emergency Departments (PEDs)

8. How Should the Effectiveness of an ASP and DSP Be Evaluated? The Different Metrics in Pediatric Settings

9. What is the Cost-Effectiveness of an ASP and a DSP?

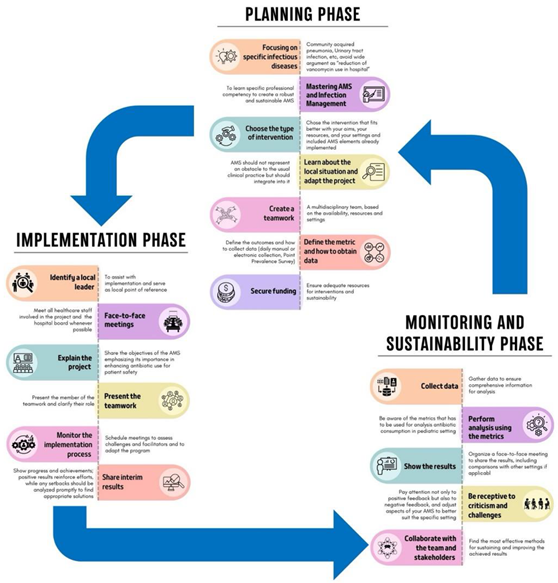

10. Which Are the Most Important Phases to Successfully Implement an ASP?

10.1. Planning Phase

10.2. Implementation Phase

10.3. Monitoring and Sustainability Phase

11. Future Perspectives

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

References

- Principi, N., and Esposito, S. (2016). Antimicrobial stewardship in paediatrics. BMC Infect Dis 16. [CrossRef]

- Tersigni, C., Montagnani, C., D’Argenio, P., Duse, M., Esposito, S., Hsia, Y., et al. (2019). Antibiotic prescriptions in Italian hospitalised children after serial point prevalence surveys (or pointless prevalence surveys): Has anything actually changed over the years? Ital J Pediatr 45. [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, U., Chiné, V., Pappalardo, M., Gismondi, P., and Esposito, S. (2020a). Improving the Quality of Hospital Antibiotic Use: Impact on Multidrug-Resistant Bacterial Infections in Children. Front Pharmacol 11. [CrossRef]

- De Luca, M., Donà, D., Montagnani, C., Vecchio, A. Lo, Romanengo, M., Tagliabue, C., et al. (2016). Antibiotic prescriptions and prophylaxis in Italian children. Is it time to change? Data from the ARPEC project. PLoS One 11. [CrossRef]

- Versporten, A., Bielicki, J., Drapier, N., Sharland, M., Goossens, H., Calle, G. M., et al. (2016). The worldwide antibiotic resistance and prescribing in european children (ARPEC) point prevalence survey: Developing hospital-quality indicators of antibiotic prescribing for children. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 71, 1106–1117. [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, E., Di Chiara, C., Costenaro, P., Cantarutti, A., Giaquinto, C., Hsia, Y., et al. (2022). Antibiotic prescribing patterns in paediatric primary care in italy: Findings from 2012–2018. Antibiotics 11. [CrossRef]

- Cook, A., Sharland, M., Yau, Y., Bielicki, J., Grimwood, K., Cross, J., et al. (2022). Improving empiric antibiotic prescribing in pediatric bloodstream infections: a potential application of weighted-incidence syndromic combination antibiograms (WISCA). Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 20, 445–456. [CrossRef]

- Frati, F., Salvatori, C., Incorvaia, C., Bellucci, A., Di Cara, G., Marcucci, F., et al. (2019). The role of the microbiome in asthma: The gut–lung axis. Int J Mol Sci 20. [CrossRef]

- Hsia, Y., Lee, B. R., Versporten, A., Yang, Y., Bielicki, J., Jackson, C., et al. (2019a). Use of the WHO Access, Watch, and Reserve classification to define patterns of hospital antibiotic use (AWaRe): an analysis of paediatric survey data from 56 countries. Lancet Glob Health 7, e861–e871. [CrossRef]

- Ballarini, S., Rossi, G. A., Principi, N., and Esposito, S. (2021). Dysbiosis in pediatrics is associated with respiratory infections: Is there a place for bacterial-derived products? Microorganisms 9, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Bossù, G., Di Sario, R., Argentiero, A., and Esposito, S. (2021). Antimicrobial prophylaxis and modifications of the gut microbiota in children with cancer. Antibiotics 10, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Newland, J. G., and Hersh, A. L. (2010). Purpose and design of antimicrobial stewardship programs in pediatrics. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 29, 862–863. [CrossRef]

- Tamma, P. D., Cosgrove, S. E., and Maragakis, L. L. (2012). Combination therapy for treatment of infections with gram-negative bacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev 25, 450–470. [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, U., Pappalardo, M., Chinè, V., Gismondi, P., Neglia, C., Argentiero, A., et al. (2020b). Role of artificial intelligence in fighting antimicrobial resistance in pediatrics. Antibiotics 9, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C., Nordby, A., Brage Hudson, D., Struwe, L., and Ruppert, R. (2023). Quality improvement: Antimicrobial stewardship in pediatric primary care. J Pediatr Nurs 70, 54–60. [CrossRef]

- Dellit, T. H., Owens, R. C., Mcgowan, J. E., Gerding, D. N., Weinstein, R. A., Burke, J. P., et al. (2007). Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America Guidelines for Developing an Institutional Program to Enhance Antimicrobial Stewardship. Clinical Infectious Diseases 44, 159–77. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/44/2/159/328413.

- Dyar, O. J., Huttner, B., Schouten, J., and Pulcini, C. (2017). What is antimicrobial stewardship? Clinical Microbiology and Infection 23, 793–798. [CrossRef]

- Dyar, O. J., Moran-Gilad, J., Greub, G., and Pulcini, C. (2019). Diagnostic stewardship: are we using the right term? Clinical Microbiology and Infection 25, 272–273. [CrossRef]

- Fabre, V., Davis, A., Diekema, D. J., Granwehr, B., Hayden, M. K., Lowe, C. F., et al. (2023). Principles of diagnostic stewardship: A practical guide from the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America Diagnostic Stewardship Task Force. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 44, 178–185. [CrossRef]

- Donà, D., Barbieri, E., Daverio, M., Lundin, R., Giaquinto, C., Zaoutis, T., et al. (2020). Implementation and impact of pediatric antimicrobial stewardship programs: a systematic scoping review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 9. [CrossRef]

- Brigadoi, G., Rossin, S., Visentin, D., Barbieri, E., Giaquinto, C., Da Dalt, L., et al. (2023). The impact of Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes in paediatric emergency department and primary care: a systematic review. Ther Adv Infect Dis 10. [CrossRef]

- Shah, P., Maheshwari, T., Patel, D., Patel, Z., Dikkatwar, M. S., and Rathod, M. M. (2024). An overview: Implementation and core elements of antimicrobial stewardship programme. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health 29. [CrossRef]

- Donà, D., Mozzo, E., Mardegan, V., Trafojer, U., Lago, P., Salvadori, S., et al. (2017). Antibiotics Prescriptions in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: How to Overcome Everyday Challenges. Am.

- WHO (2021). Antimicrobial stewardship interventions: a practical guide. Available at: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289056267 (Accessed November 6, 2024).

- Barlam, T. F., Cosgrove, S. E., Abbo, L. M., Macdougall, C., Schuetz, A. N., Septimus, E. J., et al. (2016). Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases 62, e51–e77. [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, N., Komura, M., Tsuzuki, S., Shoji, K., and Miyairi, I. (2020). The effect of preauthorization and prospective audit and feedback system on oral antimicrobial prescription for outpatients at a children’s hospital in Japan. Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy 26, 582–587. [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, E., Bottigliengo, D., Tellini, M., Minotti, C., Marchiori, M., Cavicchioli, P., et al. (2021a). Development of a Weighted-Incidence Syndromic Combination Antibiogram (WISCA) to guide the choice of the empiric antibiotic treatment for urinary tract infection in paediatric patients: a Bayesian approach. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 10. [CrossRef]

- Liberati, C., Donà, D., Maestri, L., Petris, M. G., Barbieri, E., Gallo, E., et al. (2024). Application of the Weighted-Incidence Syndromic Combination Antibiogram (WISCA) to guide the empiric antibiotic treatment of febrile neutropenia in oncological paediatric patients: experience from two paediatric hospitals in Northern Italy. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 23. [CrossRef]

- Regev-Yochay, G., Raz, M., Dagan, R., Roizin, H., Morag, B., Hetman, S., et al. (2011). Reduction in antibiotic use following a cluster randomized controlled multifaceted intervention: The Israeli judicious antibiotic prescription study. Clinical Infectious Diseases 53, 33–41. [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, E., De Luca, M., Minute, M., D’amore, C., Atti, M. L. C. D., Martelossi, S., et al. (2020). Impact and sustainability of antibiotic stewardship in pediatric emergency departments: Why persistence is the key to success. Antibiotics 9, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Gerber, J. S., Jackson, M. A., Tamma, P. D., and Zaoutis, T. E. (2021). Antibiotic stewardship in pediatrics. Pediatrics 147. [CrossRef]

- Dona, D., Baraldi, M., Brigadoi, G., Lundin, R., Perilongo, G., Hamdy, R. F., et al. (2018). The Impact of Clinical Pathways on Antibiotic Prescribing for Acute Otitis Media and Pharyngitis in the Emergency Department. Pediatr Infect Dis J 37, 901–907. [CrossRef]

- Mcgonagle, E. A., Karavite, D. J., Grundmeier, R. W., Schmidt, S. K., May, L. S., Cohen, D. M., et al. (2023). Evaluation of an Antimicrobial Stewardship Decision Support for Pediatric Infections. Appl Clin Inform 14, 108–118. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X., Zhang, Z., Hicks, J. P., Walley, J. D., King, R., Newell, J. N., et al. (2019). Long-term outcomes of an educational intervention to reduce antibiotic prescribing for childhood upper respiratory tract infections in rural China: Follow-up of a cluster-randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med 16. [CrossRef]

- Goggin, K., Hurley, E. A., Bradley-Ewing, A., Bickford, C., Lee, B. R., Pina, K., et al. (2020). Reductions in Parent Interest in Receiving Antibiotics following a 90-Second Video Intervention in Outpatient Pediatric Clinics., in Journal of Pediatrics, (Mosby Inc.), 138-145.e1. [CrossRef]

- Demoly, P., Adkinson, N. F., Brockow, K., Castells, M., Chiriac, A. M., Greenberger, P. A., et al. (2014). International Consensus on drug allergy. Allergy: European Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 69, 420–437. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, E. R., Brockow, K., Kuyucu, S., Saretta, F., Mori, F., Blanca-Lopez, N., et al. (2016). Drug hypersensitivity in children: Report from the pediatric task force of the EAACI Drug Allergy Interest Group. Allergy: European Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 71, 149–161. [CrossRef]

- Chow, T., Patel, G., Mohammed, M., Johnson, D., and Khan, D. (2023). Delabeling penicillin allergy in a pediatric primary care clinic. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 130, 667–669.

- Diane Ashiru-Oredope, Maria Richards, JaneGiles, and Louise Teare (2011). Does an antimicrobial section on a drug chart influence prescribing? pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/research/does-an-antimicrobial-section-on-a-drug-chart-influence-prescribing. Pharm J.

- Di Pentima, M. C., Chan, S., and Hossain, J. (2011). Benefits of a pediatric antimicrobial stewardship program at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics 128, 1062–1070. [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Arnaiz, E., Simó-Nebot, S., Ríos-Barnés, M., López Ramos, M. G., Monsonís, M., Urrea-Ayala, M., et al. (2020). Benefits of a Pediatric Antimicrobial Stewardship Program in Antimicrobial Use and Quality of Prescriptions in a Referral Children’s Hospital. Journal of Pediatrics 225, 222-230.e1. [CrossRef]

- Manice, C., Mularidhar, N., Campbell, J., and Nakamura, M. (2024). Implementation and perceived effectiveness of prospective audit and feedback and preauthorization by US pediatric antimicrobial stewardship programs. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 26, 117–122.

- Fratoni, A. J., Nicolau, D. P., and Kuti, J. L. (2021). A guide to therapeutic drug monitoring of β-lactam antibiotics. Pharmacotherapy 41, 220–233. [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Aziz, M. H., Brady, K., Pharm, M., Menino, †, Cotta, O., and Roberts, J. A. (2022). Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Antibiotics: Defining the Therapeutic Range. Ther Drug Monit 44. Available at: http://journals.lww.com/drug-monitoring.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021a). Core elements of hospital antibiotic stewardship programs. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/hcp/core-elements/hospital.html (Accessed November 6, 2024).

- Zembles, T. N., Nakra, N., and Parker, S. K. (2022). Extending the Reach of Antimicrobial Stewardship to Pediatric Patients. Infect Dis Ther 11, 101–110. [CrossRef]

- Knowles, R., Chandler, C., O’neill, S., Sharland, M., and Mays, N. (2024). A systematic review of national interventions and policies to optimize antibiotic use in healthcare settings in England. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 79, 1234–1247. [CrossRef]

- Newland, J. G., Stach, L. M., De Lurgio, S. A., Hedican, E., Yu, D., Herigon, J. C., et al. (2012). Impact of a prospective-audit-with-feedback antimicrobial stewardship program at a children’s hospital. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 1, 179–186. [CrossRef]

- Hersh, A. L., De Lurgio, S. A., Thurm, C., Lee, B. R., Weissman, S. J., Courter, J. D., et al. (2015). Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs in Freestanding Children’s Hospitals. Pediatric 135, 33–39. Available at: http://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article-pdf/135/1/33/902628/peds_2014-2579.pdf.

- Zaffagnini, A., Rigotti, E., Opri, F., Opri, R., Simiele, G., Tebon, M., et al. (2024). Enforcing surveillance of antimicrobial resistance and antibiotic use to drive stewardship: experience in a paediatric setting. Journal of Hospital Infection 144, 14–19. [CrossRef]

- Rossin, S., Barbieri, E., Cantarutti, A., Martinolli, F., Giaquinto, C., Da Dalt, L., et al. (2021). Multistep antimicrobial stewardship intervention on antibiotic prescriptions and treatment duration in children with pneumonia. PLoS One 16, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Opondo, C., Ayieko, P., Ntoburi, S., Wagai, J., Opiyo, N., Irimu, G., et al. (2011). Effect of a multi-faceted quality improvement intervention on inappropriate antibiotic use in children with non-bloody diarrhoea admitted to district hospitals in Kenya. BMC Pediatr 11. [CrossRef]

- Rahbarimanesh, A., Mojtahedi, S. Y., Sadeghi, P., Ghodsi, M., Kianfar, S., Khedmat, L., et al. (2019). Antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP): An effective implementing technique for the therapy efficiency of meropenem and vancomycin antibiotics in Iranian pediatric patients. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 18. [CrossRef]

- Wattier, R. L., Levy, E. R., Sabnis, A. J., Dvorak, C. C., and Auerbach, A. D. (2017). Reducing Second Gram-Negative Antibiotic Therapy on Pediatric Oncology and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Services., in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, (Cambridge University Press), 1039–1047. [CrossRef]

- Haque, A., Hussain, K., Ibrahim, R., Abbas, Q., Ahmed, S. A., Jurair, H., et al. (2018). Impact of pharmacist-led antibiotic stewardship program in a PICU of low/ middle-income country. BMJ Open Qual 7. [CrossRef]

- Taylor MG, P. DL. (2022). Antibiotic stewardship in the pediatric primary care setting. Pediatr Ann 51, 196–201.

- Frost HM, Hersh AL, and Hyun DY (2023). Next steps in ambulatory stewardship. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 37, 749–767.

- Dantuluri, K. L., Bonnet, K. R., Schlundt, D. G., Schulte, R. J., Griffith, H. G., Luu, A., et al. (2023). Antibiotic perceptions, adherence, and disposal practices among parents of pediatric patients. PLoS One 18. [CrossRef]

- Pagano, F., Amato, C., De Marco, G., Micillo, M., Cecere, G., Poeta, M., et al. (2023). Reduction in broad-spectrum antimicrobial prescriptions by primary care pediatricians following a multifaceted antimicrobial stewardship program. Front Pediatr 10. [CrossRef]

- Gerber, J. S., Prasad, P. A., Fiks, A. G., Localio, A. R., Grundmeier, R. W., Bell, L. M., et al. (2013). Effect of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention on broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing by primary care pediatricians a randomized trial. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association 309, 2345–2352. [CrossRef]

- Gerber, J. S., Prasad, P. A., Fiks, A. G., Localio, A. R., Bell, L. M., Keren, R., et al. (2014). Durability of benefits of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention after discontinuation of audit and feedback. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association 312, 2569–2570. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X., Zhang, Z., Walley, J. D., Hicks, J. P., Zeng, J., Deng, S., et al. (2017). Effect of a training and educational intervention for physicians and caregivers on antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory tract infections in children at primary care facilities in rural China: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health 5, e1258–e1267. [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, R. F., Nedved, A., Fung, M., Fleming-Dutra, K. E., Liu, C. M., Obremskey, J., et al. (2022). Pediatric Urgent Care Providers’ Approach to Antibiotic Stewardship A National Survey. Pediatr Emerg Care 38. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/threats-report/2019-.

- Meesters, K., and Buonsenso, D. (2024). Antimicrobial Stewardship in Pediatric Emergency Medicine: A Narrative Exploration of Antibiotic Overprescribing, Stewardship Interventions, and Performance Metrics. Children 11. [CrossRef]

- Mistry, R. D., May, L. S., and Pulia, M. S. (2019). Improving antimicrobial stewardship in pediatric emergency care: A pathway forward. Pediatrics 143. [CrossRef]

- Nedved, A., Lee, B. R., Hamner, M., Wirtz, A., Burns, A., and El Feghaly, R. E. (2023). Impact of an antibiotic stewardship program on antibiotic choice, dosing, and duration in pediatric urgent cares. Am J Infect Control 51, 520–526. [CrossRef]

- Lucignano, B., Cento, V., Agosta, M., Ambrogi, F., Albitar-Nehme, S., Mancinelli, L., et al. (2022). Effective Rapid Diagnosis of Bacterial and Fungal Bloodstream Infections by T2 Magnetic Resonance Technology in the Pediatric Population. J Clin Microbiol 60. [CrossRef]

- del Rosal, T., Bote-Gascón, P., Falces-Romero, I., Sainz, T., Baquero-Artigao, F., Rodríguez-Molino, P., et al. (2024). Multiplex PCR and Antibiotic Use in Children with Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Children 11. [CrossRef]

- Norman-Bruce, H., Umana, E., Mills, C., Mitchell, H., McFetridge, L., McCleary, D., et al. (2024). Diagnostic test accuracy of procalcitonin and C-reactive protein for predicting invasive and serious bacterial infections in young febrile infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 8, 358–368. [CrossRef]

- Milcent, K., Faesch, S., Guen, C. G. Le, Dubos, F., Poulalhon, C., Badier, I., et al. (2016). Use of Procalcitonin Assays to Predict Serious Bacterial Infection in Young Febrile Infants. JAMA Pediatr 170, 62–69. [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, E., Rossin, S., Giaquinto, C., Da Dalt, L., and Dona’, D. (2021b). A procalcitonin and C-reactive protein-guided clinical pathway for reducing antibiotic use in children hospitalized with bronchiolitis. Children 8. [CrossRef]

- Li, P., Liu, J. Le, and Liu, J. (2022). Procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy for pediatrics with infective disease: A updated meta-analyses and trial sequential analysis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 12. [CrossRef]

- Katz, S. E., Crook, J., Gillon, J., Stanford, J. E., Wang, L., Colby, J. M., et al. (2021). Use of a Procalcitonin-guided Antibiotic Treatment Algorithm in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 40, 333–337. [CrossRef]

- Beaumont R, Tang K, and Gwee A. (2024). The Sensitivity and Specificity of Procalcitonin in Diagnosing Bacterial Sepsis in Neonates. Hosp Pediatr 14, 199–208.

- Martínez-González, N. A., Keizer, E., Plate, A., Coenen, S., Valeri, F., Verbakel, J. Y. J., et al. (2020). Point-of-care c-reactive protein testing to reduce antibiotic prescribing for respiratory tract infections in primary care: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Antibiotics 9, 1–31. [CrossRef]

- Weragama, K., Mudgil, P., and Whitehall, J. (2021). Paediatric antimicrobial stewardship for respiratory infections in the emergency setting: A systematic review. Antibiotics 10. [CrossRef]

- Weragama, K., Mudgil, P., and Whitehall, J. (2022). Diagnostic Stewardship—The Impact of Rapid Diagnostic Testing for Paediatric Respiratory Presentations in the Emergency Setting: A Systematic Review. Children 9. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. F., Pauchard, J. Y., Hjelm, N., Cohen, R., and Chalumeau, M. (2020). Efficacy and safety of rapid tests to guide antibiotic prescriptions for sore throat. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020. [CrossRef]

- Thibeault, R., Gilca, R., Côté, S., De Serres, G., Boivin, G., and Déry, et P. (2007). Antibiotic use in children is not influenced by the result of rapid antigen detection test for the respiratory syncytial virus. Journal of Clinical Virology 39, 169–174. [CrossRef]

- Rader, T. S., Stevens, M. P., and Bearman, G. (2021). Syndromic Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction (mPCR) Testing and Antimicrobial Stewardship: Current Practice and Future Directions. Curr Infect Dis Rep 23. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B. R., Hassan, F., Jackson, M. A., and Selvarangan, R. (2019). Impact of multiplex molecular assay turn-around-time on antibiotic utilization and clinical management of hospitalized children with acute respiratory tract infections. Journal of Clinical Virology 110, 11–16. [CrossRef]

- Rao, S., Lamb, M. M., Moss, A., Mistry, R. D., Grice, K., Ahmed, W., et al. (2021). Effect of Rapid Respiratory Virus Testing on Antibiotic Prescribing among Children Presenting to the Emergency Department with Acute Respiratory Illness: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open 4, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Iran Keske, S. ¸, Zabun, B., Aksoy, K., Can, F., Palaog, E., Lu, ˘, et al. (2018). Rapid Molecular Detection of Gastrointestinal Pathogens and Its Role in Antimicrobial Stewardship. J Clin Microbiol 56. Available at: https://doi.org/10.

- McDonald, D., Gagliardo, C., Chiu, S., and Di Pentima, M. C. (2020). Impact of a rapid diagnostic meningitis/encephalitis panel on antimicrobial use and clinical outcomes in children. Antibiotics 9, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Kosmeri, C., Giapros, V., Serbis, A., and Baltogianni, M. (2024). Application of Advanced Molecular Methods to Study Early-Onset Neonatal Sepsis. Int J Mol Sci 25. [CrossRef]

- Clodi-Seitz, T., Baumgartner, S., Turner, M., Mader, T., Hind, J., Wenisch, C., et al. (2024). Point-of-Care Method T2Bacteria®Panel Enables a More Sensitive and Rapid Diagnosis of Bacterial Blood Stream Infections and a Shorter Time until Targeted Therapy than Blood Culture. Microorganisms 12. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R., Komarow, L., Virk, A., Rajapakse, N., Schuetz, A. N., Dylla, B., et al. (2021). Randomized Trial Evaluating Clinical Impact of RAPid IDentification and Susceptibility Testing for Gram-negative Bacteremia: RAPIDS-GN. Clinical Infectious Diseases 73, E39–E46. [CrossRef]

- Leber, A. L., Everhart, K., Balada-Llasat, J. M., Cullison, J., Daly, J., Holt, S., et al. (2016). Multicenter evaluation of biofire filmarray meningitis/encephalitis panel for detection of bacteria, viruses, and yeast in cerebrospinal fluid specimens. J Clin Microbiol 54, 2251–2261. [CrossRef]

- Kadambari, S., Feng, S., Liu, X., Andersson, M., Waterfield, R., Fodder, H., et al. (2024). Evaluating the Impact of the BioFire FilmArray in Childhood Meningitis: An Observational Cohort Study. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 43, 345–349. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R., and Patel, R. (2023). Molecular diagnostics for genotypic detection of antibiotic resistance: current landscape and future directions. JAC Antimicrob Resist 5. [CrossRef]

- Pai, N. P., Vadnais, C., Denkinger, C., Engel, N., and Pai, M. (2012). Point-of-Care Testing for Infectious Diseases: Diversity, Complexity, and Barriers in Low- And Middle-Income Countries. PLoS Med 9. [CrossRef]

- Brigadoi, G., Gastaldi, A., Moi, M., Barbieri, E., Rossin, S., Biffi, A., et al. (2022). Point-of-Care and Rapid Tests for the Etiological Diagnosis of Respiratory Tract Infections in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antibiotics 11. [CrossRef]

- Tan, R., Kavishe, G., Luwanda, L. B., Kulinkina, A. V., Renggli, S., Mangu, C., et al. (2024). A digital health algorithm to guide antibiotic prescription in pediatric outpatient care: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Nat Med 30, 76–84. [CrossRef]

- Kiemde, F., Valia, D., Kabore, B., Rouamba, T., Kone, A. N., Sawadogo, S., et al. (2023). A Randomized Trial to Assess the Impact of a Package of Diagnostic Tools and Diagnostic Algorithm on Antibiotic Prescriptions for the Management of Febrile Illnesses Among Children and Adolescents in Primary Health Facilities in Burkina Faso. Clinical Infectious Diseases 77, S134–S144. [CrossRef]

- Porta, A., Hsia, Y., Doerholt, K., Spyridis, N., Bielicki, J., Menson, E., et al. (2012). Comparing neonatal and paediatric antibiotic prescribing between hospitals: A new algorithm to help international benchmarking. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 67, 1278–1286. [CrossRef]

- Davey, P., Marwick, C. A., Scott, C. L., Charani, E., Mcneil, K., Brown, E., et al. (2017). Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017. [CrossRef]

- Abel, K., Agnew, E., Amos, J., Armstrong, N., Armstrong-James, D., Ashfield, T., et al. (2024). System-wide approaches to antimicrobial therapy and antimicrobial resistance in the UK: the AMR-X framework. Lancet Microbe 5, e500–e507. [CrossRef]

- Moja, L., Zanichelli, V., Mertz, D., Gandra, S., Cappello, B., Cooke, G. S., et al. (2024). WHO’s essential medicines and AWaRe: recommendations on first- and second-choice antibiotics for empiric treatment of clinical infections. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 30, S1–S51. [CrossRef]

- Hsia, Y., Sharland, M., Jackson, C., Wong, I. C. K., Magrini, N., and Bielicki, J. A. (2019b). Consumption of oral antibiotic formulations for young children according to the WHO Access, Watch, Reserve (AWaRe) antibiotic groups: an analysis of sales data from 70 middle-income and high-income countries. Lancet Infect Dis 19, 67–75. [CrossRef]

- Wattier, R. L., Thurm, C. W., Parker, S. K., Banerjee, R., Hersh, A. L., Brogan, T. V., et al. (2021). Indirect Standardization as a Case Mix Adjustment Method to Improve Comparison of Children’s Hospitals’ Antimicrobial Use. Clinical Infectious Diseases 73, 925–932. [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, E., Versporten, A., and Goossens, H. (2017). Is there any difference in quality of prescribing between antibacterials and antifungals? Results from the first global point prevalence study (Global PPS) of antimicrobial consumption and resistance from 53 countries. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 72, 2906–2909. [CrossRef]

- Hersh, A. L., Shapiro, D. J., Pavia, A. T., and Shah, S. S. (2011). Antibiotic prescribing in ambulatory pediatrics in the United States. Pediatrics 128, 1053–1061. [CrossRef]

- UKHSA (2024). AMR local indicators . https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/amr-local-indicators#3. Available at: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/amr-local-indicators#3 (Accessed November 6, 2024).

- Sarma, J. B., Marshall, B., Cleeve, V., Tate, D., Oswald, T., and Woolfrey, S. (2015). Effects of fluoroquinolone restriction (from 2007 to 2012) on resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: Interrupted time-series analysis. Journal of Hospital Infection 91, 68–73. [CrossRef]

- Lawes, T., Lopez-Lozano, J. M., Nebot, C. A., Macartney, G., Subbarao-Sharma, R., Dare, C. R. J., et al. (2015). Effects of national antibiotic stewardship and infection control strategies on hospital-associated and community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections across a region of Scotland: A non-linear time-series study. Lancet Infect Dis 15, 1438–1449. [CrossRef]

- Gagliotti, C., Nobilio, L., Milandri, M., and Moro, M. L. (2006). Macrolide Prescriptions and Erythromycin Resistance of Streptococcus pyogenes mycin-resistant. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/42/8/1153/282887.

- Schroeder, M. R., and Stephens, D. S. (2016). Macrolide resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 6. [CrossRef]

- Shaughnessy, M. K., Amundson, W. H., Kuskowski, M. A., DeCarolis, D. D., Johnson, J. R., and Drekonja, D. M. (2013). Unnecessary Antimicrobial Use in Patients with Current or Recent Clostridium difficile Infection . Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 34, 109–116. [CrossRef]

- Cooke, J., Stephens, P., Ashiru-Oredope, D., Charani, E., Dryden, M., Fry, C., et al. (2015). Longitudinal trends and cross-sectional analysis of English national hospital antibacterial use over 5 years (2008-13): Working towards hospital prescribing quality measures. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 70, 279–285. [CrossRef]

- Keshavarzi, F. (2022). Practical Concerns about the Metrics and Methods of Financial Outcome Measurement in Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs: A Narrative Review. Iran J Med Sci 47, 394–405. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Dawkins, B., Hicks, J. P., Walley, J. D., Hulme, C., Elsey, H., et al. (2018). Cost-effectiveness analysis of a multi-dimensional intervention to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for children with upper respiratory tract infections in China. Tropical Medicine and International Health 23, 1092–1100. [CrossRef]

- Lubell, Y., Do, N. T. T., Nguyen, K. V., Ta, N. T. D., Tran, N. T. H., Than, H. M., et al. (2018). C-reactive protein point of care testing in the management of acute respiratory infections in the Vietnamese primary healthcare setting - A cost benefit analysis. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 7. [CrossRef]

- Borek, A. J., Anthierens, S., Allison, R., McNulty, C. A. M., Anyanwu, P. E., Costelloe, C., et al. (2020). Social and contextual influences on antibiotic prescribing and antimicrobial stewardship: A qualitative study with clinical commissioning group and general practice professionals. Antibiotics 9, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Goycochea-Valdivia, W. A., Melendo Pérez, S., Aguilera-Alonso, D., Escosa-Garcia, L., Martínez Campos, L., and Baquero-Artigao, F. (2022). Position statement of the Spanish Society of Paediatric Infectious Diseases on the introduction, implementation and assessment of antimicrobial stewardship programmes in paediatric hospitals. Anales de Pediatría (English Edition) 97, 351.e1-351.e12. [CrossRef]

- Poudel, A. N., Zhu, S., Cooper, N., Little, P., Tarrant, C., Hickman, M., et al. (2023). The economic burden of antibiotic resistance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 18. [CrossRef]

- Morel, C. M., Alm, R. A., Årdal, C., Bandera, A., Bruno, G. M., Carrara, E., et al. (2020). A one health framework to estimate the cost of antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 9. [CrossRef]

- Turner, R. B., Valcarlos, E., Loeffler, A. M., Gilbert, M., and Chan, D. (2017). Impact of an antimicrobial stewardship program on antibiotic use at a nonfreestanding children’s hospital. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 6, e36–e40. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, A. (2017). Antibiotic stewardship: Why we must, how we can. Cleve Clin J Med 84, 673–679. [CrossRef]

- Mendelson, M., Morris, A. M., Thursky, K., and Pulcini, C. (2020). How to start an antimicrobial stewardship programme in a hospital. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 26, 447–453. [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, S. E., Hermsen, E. D., Rybak, M. J., File, T. M., Parker, S. K., and Barlam, T. F. (2014). Guidance for the Knowledge and Skills Required for Antimicrobial Stewardship Leaders. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 35, 1444–1451. [CrossRef]

- Wubishet, B. L., Merlo, G., Ghahreman-Falconer, N., Hall, L., and Comans, T. (2022). Economic evaluation of antimicrobial stewardship in primary care: a systematic review and quality assessment. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 77, 2373–2388. [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, P., Coffin, S. E., Mekasha, A., McMullan, B., Cotton, M. F., and Bryant, P. A. (2022). Comparison of Antimicrobial Stewardship and Infection Prevention and Control Activities and Resources between Low-/Middle- and High-income Countries. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 41, S3–S9. [CrossRef]

- Ecdc (2022). Antimicrobial consumption in the EU/EEA (ESAC-NET) - AER for 2022. Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/antimicrobial-consumption-eueea-esac-net-annual-.

- Kopsidas, I., Vergnano, S., Spyridis, N., Zaoutis, T., and Patel, S. (2020). A Survey on National Pediatric Antibiotic Stewardship Programs, Networks and Guidelines in 23 European Countries. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 39, E359–E362. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021b). Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship The Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship Facility Checklist. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/hcp/core-elements/outpatient-antibiotic-stewardship.html#:~:text=The%20four%20core%20elements%20of,reporting%2C%20and%20education%20and%20expertise. (Accessed November 6, 2024).

- Keller, S. C., Cosgrove, S. E., Miller, M. A., and Tamma, P. (2022). A framework for implementing antibiotic stewardship in ambulatory care: Lessons learned from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Safety Program for Improving Antibiotic Use. Antimicrobial Stewardship and Healthcare Epidemiology 2, 185–190. [CrossRef]

- Zakhour, J., Haddad, S. F., Kerbage, A., Wertheim, H., Tattevin, P., Voss, A., et al. (2023). Diagnostic stewardship in infectious diseases: a continuum of antimicrobial stewardship in the fight against antimicrobial resistance. Int J Antimicrob Agents 62. [CrossRef]

- Pansa, P., Hsia, Y., Bielicki, J., Lutsar, I., Walker, A. S., Sharland, M., et al. (2018). Evaluating Safety Reporting in Paediatric Antibiotic Trials, 2000–2016: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Drugs 78, 231–244. [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, W., Conly, J., Thirion, D. J. G., Choi, K., Pelude, L., Cayen, J., et al. (2023). Antimicrobial use among paediatric inpatients at hospital sites within the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program, 2017/2018. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 12. [CrossRef]

- Wicha, S. G., Märtson, A. G., Nielsen, E. I., Koch, B. C. P., Friberg, L. E., Alffenaar, J. W., et al. (2021). From Therapeutic Drug Monitoring to Model-Informed Precision Dosing for Antibiotics. Clin Pharmacol Ther 109, 928–941. [CrossRef]

- Cojutti, P. G., Gatti, M., Bonifazi, F., Caramelli, F., Castelli, A., Cavo, M., et al. (2023). Impact of a newly established expert clinical pharmacological advice programme based on therapeutic drug monitoring results in tailoring antimicrobial therapy hospital-wide in a tertiary university hospital: Findings after the first year of implementation. Int J Antimicrob Agents 62. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Oza, S., Hogan, D., Chu, Y., Perin, J., Zhu, J., et al. (2016). Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. The Lancet 388, 3027–3035. [CrossRef]

- Cox, J. A., Vlieghe, E., Mendelson, M., Wertheim, H., Ndegwa, L., Villegas, M. V., et al. (2017). Antibiotic stewardship in low- and middle-income countries: the same but different? Clinical Microbiology and Infection 23, 812–818. [CrossRef]

- Boracchini, R., Brigadoi, G., Barbieri, E., Liberati, C., Rossin, S., Tesser, F., et al. (2024). Validation of Administrative Data and Timing of Point Prevalence Surveys for Antibiotic Monitoring. JAMA Netw Open 7, e2435127. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A. P., Ashiru-Oredope, D., and Beech, E. (2015). Antibiotic stewardship initiatives as part of the UK 5-year antimicrobial resistance strategy. Antibiotics 4, 467–479. [CrossRef]

- Giacobbe, D. R., Marelli, C., Guastavino, S., Mora, S., Rosso, N., Signori, A., et al. (2024). Explainable and Interpretable Machine Learning for Antimicrobial Stewardship: Opportunities and Challenges. Clin Ther 46, 474–480. [CrossRef]

- Feretzakis, G., Loupelis, E., Sakagianni, A., Kalles, D., Martsoukou, M., Lada, M., et al. (2020). Using machine learning techniques to aid empirical antibiotic therapy decisions in the intensive care unit of a general hospital in Greece. Antibiotics 9. [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, M., Kabanza, F., Nault, V., and Valiquette, L. (2016). Evaluation of a machine learning capability for a clinical decision support system to enhance antimicrobial stewardship programs. Artif Intell Med 68, 29–36. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. Y., Yu, D., Fan, M. M., Zhang, X., Jin, Z. Y., Tang, C., et al. (2024). Antimicrobial resistance crisis: could artificial intelligence be the solution? Mil Med Res 11. [CrossRef]

- Driesnack, S., Rücker, F., Dietze-Jergus, N., Bondarenko, A., Pletz, M. W., and Viehweger, A. (2024). A practice-based approach to teaching antimicrobial therapy using artificial intelligence and gamified learning. JAC Antimicrob Resist 6. [CrossRef]

- Howard, A., Aston, S., Gerada, A., Reza, N., Bincalar, J., Mwandumba, H., et al. (2024). Antimicrobial learning systems: an implementation blueprint for artificial intelligence to tackle antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Digit Health 6, e79–e86. [CrossRef]

- Stenehjem, E., Hersh, A. L., Buckel, W. R., Jones, P., Sheng, X., Evans, R. S., et al. (2018). Impact of implementing antibiotic stewardship programs in 15 small hospitals: A cluster-randomized intervention. Clinical Infectious Diseases 67, 525–532. [CrossRef]

- The Joint Commission (2016). New Antimicrobial Stewardship Standard. Joint Commission Perspectives 36.

| Setting | Incremental cost | Potential saving/benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Inpatient | Clinical pathways implementation:

Implementation (operational) cost:

|

Direct costs:

Indirect costs:

|

| Outpatient | Medical consultations and revisits Nursing support and data monitoring Clinical pathways implementation:

Training for healthcare professionals:

|

Medical consultation for antimicrobial prescription Costs related to antimicrobial therapies (reimbursement by the payer) Prescription monitoring or review Ancillary tests (in Emergency Department) Medication costs |

| Direct costs: | Indirect costs: | Associated probabilities: |

|---|---|---|

Costs of any treatment or prophylaxis

Costs of long- term consequences of AMR infection

Out-of-pocket expenditure by the patient for care

Training of health care professionals and information/communication Legal and insurance costs

|

Productivity loss

Psychological impact on the patient and family (factored in as QALY) Financial burden on the government for disability benefits Hospital costs

Research and development of new antibiotics Additional costs non directly related to human health* |

Mortality (overall): deaths WITH a MDR infection Mortality (attributable): deaths FROM an MDR infection Morbidity:

Additional diagnostic procedures Screening programs Insurance to cover extra AMR costs |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).